#african grey in Television shows

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#african grey in Film#african grey in Films#african grey in Literature#african grey in Television#african grey in Television shows#african grey life#African Grey Life Span#African grey lifespan#african grey names#african grey parrot buy#african grey parrot for sale#african grey parrot lifespan in captivity#african grey parrots in books#African Grey Parrots in Children's Books#african grey parrots in Film#african grey parrots in Films#african grey parrots in Literature#African Grey Parrots in Pop Culture#african grey parrots in Television#african greys for sale#Alex & Me#amazing parrot#Animal Planet Extraordinary Animals#axolotl squishmallow#Baretta#Baretta drama#BBC The Life of Birds#buy a parrot#buy african grey parrot online#buying an african grey parrot

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ann Way Season: Within These Walls - Get the Glory Down

As I commented before, doing a series of posts about an actor encourages me to see shows that I have never seen before, and this is one that you won't have seen on this blog before. The reason is that I don't tend to enjoy prison dramas because I see the subject matter as unremittingly dreary and in my cynical way I see prison dramas as a cheap option for TV companies because in their nature you just need one set and a lot of grey paint.

Within these Walls was broadcast from 1974 to 1978 and is unusual for two things. The first is that despite being broadcast at the height of wiping, there is only one episode missing. The other is that it gives much more attention to the staff of the women's prison it features than to the lives of the prisoners. It has been commercially released in its entirety if you're interested but luckily this episode has found its was on to YouTube. It's also famous for starring legendary actress Googie Withers, who unfortunately won't ever have one of these seasons dedicated to her because of the relative paucity of her television work.

The subject of Get the Glory Down is a very interesting one to me. The first part is about how one prisoner puts a curse on another prisoner who subsequently dies. The second half recounts how the prisoner who did the curse is so remorseful that she has a religious conversion, and given that she was very much top dog in the prison, the prisoners who always did do what she told them, then follow her in her religious beliefs and practices.

You would be correct if you jumped to the conclusion that the first part about the curse, sounds very much like the plot of one of those old horror films that take place in some far-flung part of the Empire where the primitives are dead primitive and there are endless zombies. This is an incredibly difficult thing to transplant to 1970s Britain, and an integral part of the plot is that the victim of the curse has not long come from Africa and the prisoner who cursed her is of African-Caribbean/Black British descent. The racial overtones of this make this a difficult episode because Black people are clearly depicted as naive, credulous, and so on. There's a lot of '"You people" have a different way of looking at things'.

As it happens Ann Way plays one of the characters who are obviously intended to stop the show being only a depiction of Black people as credulous, because she plays a white person who's credulous. It's a bit different from the other roles I've seen her in because it's not so dotty. She has the misfortune to being the cellmate to Luella who laid the curse, and obviously does all the work, but asks to be moved to another cell after it comes out about the curse. Ann's character is frightened of the curse and runs away.

It may be because of the show's focus on the staff (although they also seem to take everything the prisoners say at face value) but I have a criticism of this episode. This is that I'm surprised that an entire prison full of women take the word of a convicted conwoman at face value. Even the screws are more cynical about Luella than the prisoners are, and you'd really think they'd be more suspicious. But as I say this may be for narrative reasons. As it happens this episode was written by Peter Wildeblood, a journalist who was in a position to know about (admittedly men's) prisons because his imprisonment in 1954 for 'conspiracy to incite certain male persons to commit serious offences with male persons' was one of the cases which ultimately led to the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain. The idea of punishing a man for being sexually attracted to other men, by locking him up in a building full of other men who couldn't escape and hadn't even seen another woman in months or even years, muct have meant sense to somebody, but I expect that strange experience would affect subsequent writings about prison.

In fact I do really like the way the staff entirely hold the discussion of what is happening. There is quite a lot of discussion about the subject of the curse, the responsibility of the prison to the prisoners, ethical questions about the religious revival suddenly happening in their midst, what they can or should do about it given that it's being run by a convicted conwoman, and so on. In fact there is a lot in this episode to interest me, it's just that it is in a setting which I really don't like.

It also gives a slightly different role to our friend Ann Way, and honestly I really just wish we were told what she was in prison for, because it would make the character perfect!

This blog is mirrored at

culttvblog.tumblr.com/archive (from September 2023) and culttvblog.substack.com (from January 2023 and where you can subscribe by email)

Archives from 2013 to September 2023 may be found at culttvblog.blogspot.com and there is an index to the tags used on the Tumblr version at https://www.tumblr.com/culttvblog/729194158177370112/this-blog

0 notes

Text

Multimedia Journal: Black-ish

Black-ish is a popular American sitcom that started in 2014, created by Kenya Barris. It follows the Johnson family: parents Dre (Anthony Anderson) and Rainbow (Tracee Ellis Ross), along with their four children, as they live in a mostly white, upper-middle-class neighborhood. The show uses humor to explore serious issues about race, culture, and identity, making it a great way to discuss the African American experience in today’s America (Barris, 2014).

Black-ish fits well with our course on multicultural America. It looks at the challenges African Americans face in balancing their own cultural identity with fitting into a mostly white society. The show talks about big topics like racism, cultural appropriation, and the pressure to blend in while keeping one’s heritage (Barris, 2014).

From our course readings, we see that Black-ish does a great job showing the many sides of African American life. It breaks down stereotypes and gives a real look at what it’s like to live in a diverse society. For example, in the episode "Juneteenth" (Season 4, Episode 1), the show explains the importance of Juneteenth, a holiday celebrating the end of slavery in the U.S. It also points out how this important day isn’t widely recognized, using humor to discuss serious messages about race and identity (Barris, 2017).

Black-ish" sparks important conversations about race, ethnicity, and cultural diversity through addressing sensitive issues, which the show tackles topics like racism, police brutality, and the complexities of being black in America. For example, the episode "Hope" directly addresses police brutality against African Americans, referencing real-life cases like Freddie Grey and Sandra Bland (Long, 2017). The show examines the tension between maintaining cultural roots and assimilating into mainstream society, a theme that resonates with the exploration of identity in projects like The Grace Lee Project and The Hapa Project (Long, 2017). By presenting a successful, upper-middle-class African American family, "Black-ish" challenges stereotypical portrayals of black families on television (Long, 2017). The show often incorporates historical information about the African American experience, educating viewers about aspects of black history that are often overlooked in mainstream education (Long, 2017). Black-ish" contributes to broader societal discussions about race and identity. Like Ligon's artwork, which challenges viewers to question their assumptions about racial features, "Black-ish" encourages its audience to confront their own biases and preconceptions about race (McNamara, 2014).

Black-ish" provides a detailed look at African American identity in today's America. The show explores the difficulties of keeping one's cultural identity while living in a mainly white society, similar to themes in Glenn Ligon's artwork "Self-Portrait Exaggerating my Black Features/Self-Portrait Exaggerating my White Features" (1998). The series addresses how race mixes with class, generational differences, and job status. For instance, Andre's promotion to "Senior Vice President of the Urban Division" highlights how race affects workplace dynamics. This well-rounded depiction gives viewers a better understanding of the challenges and successes experienced by African Americans today.

Additionally, Black-ish doesn’t shy away from controversial topics. Episodes have addressed police brutality ("Hope," Season 2, Episode 16), the N-word ("The Word," Season 2, Episode 1), and the 2016 presidential election ("Lemons," Season 3, Episode 12). These episodes provide a platform for viewers to engage with difficult conversations about race and politics, using the Johnson family’s experiences to reflect broader societal issues (Barris, 2016a, 2016b, 2017).

youtube

References

Barris, K. (2014). Black-ish. ABC.

Barris, K. (2016a). The Word. In Black-ish (Season 2, Episode 1). ABC.

Barris, K. (2016b). Hope. In Black-ish (Season 2, Episode 16). ABC.

Barris, K. (2017). Lemons. In Black-ish (Season 3, Episode 12). ABC.

Barris, K. (2017). Juneteenth. In Black-ish (Season 4, Episode 1). ABC.

Barris, K. (2019). Black Like Us. In Black-ish (Season 5, Episode 10). ABC.

Long, K. (2017). Black-ish and the black experience: Diversifying and affirming accurately and authentically. In Culture and the Sitcom: Student Essays (Chap. 5). Library Partners Press. https://librarypartnerspress.pressbooks.pub/studentessaysculturesitcomv1/chapter/black-ish-and-the-black-experience-diversifying-and-affirming-accurately-and-authentically/

Media links:

Photo 1: "Black-Ish" Ended, But Its Lesson Lives On (buzzfeed.com)

Photo 2: https://telltaletv.com/2017/10/blackish-review-juneteenth-season-4-episode-1/

Video 1: About "Juneteenth" https://telltaletv.com/2017/10/blackish-review-juneteenth-season-4-episode-1/

Video 2: Jimmy Kimmel interviews with the Black-ish cast. https://youtu.be/7OfOG4GgJSQ?si=AtnJLWBuqY77QjdG

0 notes

Text

Paris K. C. Barclay (June 30, 1956) is a television director and producer, writer, LGBT activist. He is a two-time Emmy Award winner and is among the busiest single-camera television directors, having directed over 160 episodes of television, for series such as NYPD Blue, ER, The West Wing, CSI, Lost, The Shield, House, Law & Order, Monk, Numb3rs, City of Angels, Cold Case, and more recently Sons of Anarchy, The Bastard Executioner, The Mentalist, Weeds, NCIS: Los Angeles, In Treatment, Glee, Smash and The Good Wife, Extant, and Manhattan, Empire, and Scandal. He worked as an executive producer and principal director for Pitch. He was tapped as the executive producer and director of the Shondaland show, Station 19, which follows a group of Seattle firefighters that exist in the Grey’s Anatomy universe and stars Jaina Lee Ortiz, Jason George, Grey Damon, Miguel Sandoval, Jay Hayden, Danielle Savre, Barrett Doss, Okierette Onadowan, and Boris Kodjoe. The show is executive-produced by Shonda Rhimes, Betsy Beers, and Krista Vernoff.

He served two terms as the President of the Directors Guild of America, breaking historical grounds as the first African American and first Gay man to lead the organization. He has been listed by Variety as “one of the 500 most influential business leaders in Hollywood.”

He was born in Chicago Heights. Raised Catholic, he attended La Lumiere School, a private college preparatory boarding school in La Porte, Indiana. On scholarship, he was one of the first African-Americans to attend the school.

He went on to Harvard College, where he was extremely active in student musical theatre productions and the a cappella singing group The Harvard Krokodiloes. During his four years there, he wrote 16 musicals, including the music for two of the annual Hasty Pudding shows. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Debbie Allen

Debbie Allen è l’attrice, ballerina, coreografa, regista e produttrice televisiva, conosciuta in tutto il mondo per la sua interpretazione dell’insegnante di danza Lydia Grant nella serie culto degli anni Ottanta Saranno famosi.

Ha lavorato a più di 50 film e produzioni televisive collezionando una bella sfilza di premi tra cui un Golden Globe, cinque Emmy Awards su venti nomination, due Tony Awards e dieci Image Award. Nel 1991 le è stata dedicata una stella sulla Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Come coreografa detiene il record per il maggior numero di vittorie e nomination agli Emmy.

Ha fatto parte della Commissione Presidenziale della Casa Bianca per le Arti e gli Studi Umanistici.

Un altro suo personaggio passato alla storia delle serie tv è stato la dottoressa Catherine Avery in Grey’s Anatomy.

Il suo nome completo è Deborah Kaye Allen ed è nata a Houston, il 16 gennaio 1950, sua madre è Vivian Ayers Allen, poeta e attivista culturale autrice di Spice of Dawns raccolta poetica nominata al Pulitzer e sua sorella è l’attrice e regista Phylicia Rashad, che è stata la famosa Clair Robinson nella sitcom The Cosby Show (in italiano I Robinson).

Debbie Allen, che danza da quando era una bambina, è laureata in letteratura greca alla Howard University e ha studiato recitazione alla HB Studio di New York.

Dopo anni, la sua università l’ha insignita col dottorato honoris causa così come la University of North Carolina School of the Arts.

Ha debuttato a Broadway nel 1970 e, dopo diversi musical e serie tv, è stata nel cast in un altro film televisivo che ha fatto epoca: Radici.

Nel 1980 ha ottenuto la prima candidatura ai Tony Awards come protagonista di West Side Story vincendo il Drama Desk Award. La sua prima volta al cinema è stata nel 1979, ma il ruolo che l’ha resa famosa è stato sicuramente quello di Miss Grant in Saranno famosi. Oltre a recitare era anche la coreografa. È stata l’unica protagonista a lavorare nel film del 1980, diretto da Alan Parker, nella serie tv, girata tra il 1982 e il 1987, che le è valso due Emmy Awards e un Golden Globe (prima donna nera a vincere come miglior attrice per una serie tv) e anche nel remake del 2009 in cui era la preside della scuola d’arte.

Dopo diversi film e spettacoli a Broadway, ha diretto e prodotto 83 episodi della fortunata A different World serie spin-off del Cosby Show.

Ha anche inciso due dischi da solista Sweet Charity (1986) e Special Look (1989) e continuato a recitare, dirigere e creare coreografie per film, musical e numerose serie tv. Ha anche prestato la sua voce per diversi film d’animazione.

Come coreografa ha ricevuto 10 nomination agli Oscar, delle quali consecutivamente dal 1991 al 1994 e per Motown 30: What’s Goin’ on! dedicato ai 30 anni della Motown che le è valso un altro Emmy per il segmento African American Odyssey.

Nel 1997 ha co-prodotto il film di Steven Spielberg Amistad, che le è valso il premio Producers Guild of America.

Nel 2001, a Los Angeles, ha fondato la Debbie Allen Dance Academy organizzazione no profit per incoraggiare giovani talenti.

Non ha mai smesso di dirigere musical e serie di successo come Scandal, Le regole del delitto perfetto, Empire e altre ancora, quasi tutte hanno come protagonista una donna nera.

Nel 2020 ha diretto, prodotto e curato le coreografie di Natale in città con Dolly Parton, che le è valso la quinta statuetta per le coreografie oltre al Governors Award 2021. Premio per meriti artistici accumulati o straordinari al di là delle candidature degli Emmy. Tre mesi prima era stata festeggiata ai Kennedy Center Honors.

Debbie Allen non ha mai mancato di dare il suo contributo in cause contro razzismo e violenza sulle donne, ha composto la coreografia del famoso flash mob mondiale One Billion Rising e marciato contro le politiche misogine di Trump.

Una carriera lunga cinquant’anni la sua, accompagnata dalla partecipazione sociale come artista e come singola cittadina per rivendicare diritti non ancora raggiunti o in continuo pericolo. Una vera forza della natura.

0 notes

Link

#johnnydepp2020#johnnydeppaccent#johnnydeppage#johnnydeppaimovie#johnnydeppalpacino#johnnydeppamber#johnnydeppamberheard#johnnydeppangelinajolie#johnnydeppasjoker#johnnydeppdaughter#johnnydeppjoker#johnnydeppkids#johnnydeppmovies#johnnydeppwife#johnnydeppwillywonka#johnnydeppyoung

0 notes

Text

Wild Africa Fund unveils Nigeria’s first wildlife show for kids

Wild Africa Fund has launched a new wildlife-focused television series, Dr Mark Animal TV Show, for kids between ages seven and 14. This is contained in a statement by Wild Africa Fund Nigeria’s Representative, Mr Festus Iyorah, on Saturday in Lagos. “The kiddies show premieres this Saturday and every other Saturday at 8.45 a.m. on Silverbird TV DSTV channel 252, StarTimes Channel 109, and GOTV channel 92/192. “The show will educate children between ages seven and 14 on Nigeria’s amazing wildlife and the need to protect them,” the statement said. It said that Nigeria had become a transit hub for the illegal wildlife trade of pangolin scales and ivory in the last few years. The statement noted that the Nigeria Customs Service had made four major seizures of pangolin scales, ivory, and other wildlife parts in the last 13 months. It added that there was a growing appetite for bushmeat consumption, especially among urban dwellers in Nigeria. “Conservationists say illegal wildlife trade and a demand for bushmeat have sharply declined Nigeria’s wildlife and biodiversity. “They estimate that Nigeria has fewer than 50 lions, 100 gorillas, 500 elephants, and 2,300 chimpanzees left in the wild. “Generally, ignorance and low awareness about Nigeria’s amazing biodiversity and the importance wild animals play in the environment have contributed to the continuous destruction of Nigeria’s wildlife. “These existential challenges have inspired the need for public awareness and educational materials that educate the general public, especially young people who are best equipped to save our environment for future generations,” it said. The statement quoted Mr Peter Knights, Founder of Wild Africa Fund and the Executive producer of the new TV show as saying that kids would enjoy the show. “We hope that kids will be excited to learn about these animals and how we must protect them for their futures,” Knights said. The statement added that Mark’s Animal TV show would enlighten children on the human and ecological importance of wild animals such as pangolins, lions and African grey parrots, among others. It said that the children would also learn fun facts about these animals including domestic animals like dogs. The statement said that a quiz competition had veen scheduled to inspire retentive knowledge in kids at the end of the show. It said that the animal show comes at a time local content for children, especially on the environment, is nonexistent. The statement also quoted Iyorah as saying that Wild African Fund would continue to invest in educational wildlife content. “We plan to invest in educational wildlife content that will empower children as the next generation of wildlife ambassadors. “We expect children to impact their cycle of influence with what they learnt from watching the show,” he said. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Everything You've Ever Wanted to Know About producent skarpetek

Africa is undergoing an incredible Artistic renaissance, it truly is mindblowing to witness. I a short while ago moved from your United kingdom to Ghana to experience Africa and its Imaginative elevation mainly producent skarpetek because it unfolds. On this page, I'm planning to showcase a number of the most fascinating Innovative makes to come out in the continent.™

Chale Socks

Chale Socks are an ground breaking, Ghanaian clothing brand name. Their bold, distinct styles concentrate on utilising common Adinkra symbols and African styles and motifs to generate beautiful, artistic socks.

OhYesLord

OhYesLord is usually a Johannesburg-primarily based streetwear model. Their Most important intention is to market African youth culture. Their models are straightforward still eye-catching, capturing the absolutely free spirited character of African youth.

Waffles N Cream

Wafflesncream is actually a skateboard collective located in Lagos Nigeria. In combination with the collective, In addition they operate a quirky streetwear clothes store. A really impressive model, advertising and marketing creative self expression among the Nigerian youth.

Tongoro

youtube

Tongoro is owned and managed by productive media mogul Sarah Diouf. The Dakar-based mostly trend model called Tongoro studio provides Daring, nonetheless basic models.

Selly Raby Kane

Selly Raby Kane can be a Senegalese vogue designer who makes remarkably creative pieces. Her brand was born out of a passion for urban African motivated model. Her items show an uninhibited design and style and grace. The brand name is often referred to as superior trend satisfies edgy, urban Afro chic.

My Working experience Dealing with African Inventive Models

I have worked with numerous African Inventive manufacturers. I observed the passion, dedication to their craft and also the perseverance to succeed in a continent where by chances are very easy to location but difficult to capitalise on. The talent in Africa is unbelievable, inspiring, motivating. When I touch down on African soil, my initially thought is to produce, discover, produce. Africa pushes you in a way that I might have not believed doable.

African brands embody a uniqueness that is difficult to find any place else on the earth. You will find a raw grit and fervour amongst African creatives. The fire burns sturdy, it is truly survival of the fittest on the market. The lucky couple who ensure it is to the very best can only but reminisce on battle, times passed by where almost nothing seemed hopeful, every thing appeared hopeless but nonetheless they pushed on through concern, obstacles and uncertainty. There is a thing definitely special happening in Africa right this moment, I'm blessed being listed here to witness everything unfold right before my really eyes.

Some time back I wrote and posting on this subject. However, Letterman suggests his socks aren't white. Very well, they look white on my television set. They must glimpse white to others as well or why would he make the comment. I suppose These are grey or light-weight blue or these kinds of. Who cares? Will not They appear foolish on a man in the darkish Brooks Brothers go well with?

I dress in white socks each day. Once i set them on Sunday to head to Church my spouse goes ballistic. I explain to her not to fret. I'll just pull on my cowboy boots.

Here's the very first best 10 factors I gave for Letterman's white socks:

1. He has jungle rot from WW II.

two. He hates to look for matching socks in the dead of night.

3. He isn't going to wish to ignore his "Region Pumpkin" roots.

four. His brother is a male nurse with a large garments allowance.

five. It can help him conceal from the cotton discipline in the revenuers, Aside from he's a Chicago White Sox supporter.

six. He is surely an avid Whitetail Deer hunter.

seven. He is effective an evening work inside of a bakery.

eight. He thinks he is Frosty the Snowman.

9. His fantastic grandmother wore white socks and that's how he remembers her.

And also the tenth cause that David Letterman wears white sox is:

ten. He hopes to try out for the following Mickey-Mouse-kind Disney Character.

Allow me to share 10 additional prime causes David Letterman wears white socks but this time we will use Letterman's reverse get:

Quantity ten. He is recognizing the demise with the Polar Bear.

Number 9. He is going to Engage in inside the snow along with his boy and he doesn't want the neighbors to determine him.

Range eight. It ruins the photos with the paparazzi.

Quantity seven. He can discover matching socks at nighttime with out waking his son.

Selection six. The hospital recommends white socks for repeated emergency bypass operation.

Selection five. He read that Napoleon favored white socks.

Range four. He does not want to be chosen as the most beneficial Dressed Man from the Year by Persons Magazine.

Variety 3. He's going to Bermuda appropriate following the demonstrate and will be shifting into his white go well with.

Range two. Paul explained he seems terrific dressed similar to a geek--

as well as the Number One motive that Dave Letterman wears white sox is:

No 1. It is a component of his Clown Match!

Fly Aged Glory!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

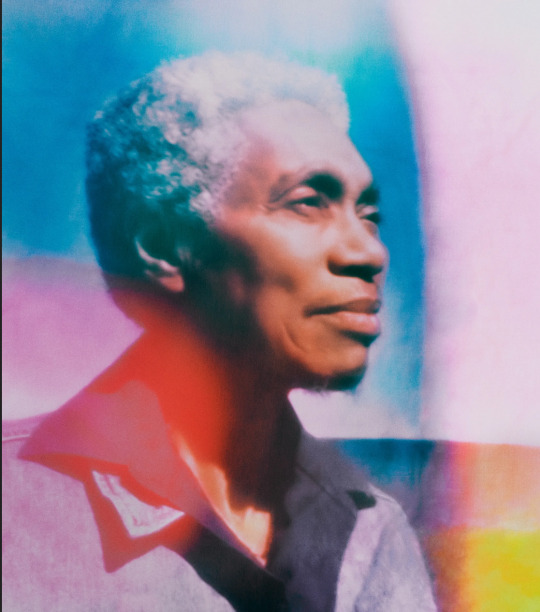

IDs: two photos of Beverly Glenn-Copeland, an elderly black transgender man. The first photo shows him looking to the right and smiling serenly. He is wearing an open collar grey shirt and has close cropped grey hair, with a small fuzzy beard on his chin. The colours of the photo have been edited to look abstract and vibrant. The second photograph is of him sat in a yellow swivel chair with his legs crossed, resting his hands on his knee and smiling widely at the camera. He is wearing a dark blue suit with a light blue tie. ED.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/09/21/beverly-glenn-copelands-music-for-a-future-that-never-came

“In the early nineteen-eighties, Beverly Glenn-Copeland was living in a quiet part of Ontario famous for its scenic hills and lakes. He heard about the advent of the personal computer and, owing to a fascination with “Star Trek” and science-fiction futurism, became instantly intrigued. He bought one, even though he had no idea how to use it. Initially, he just walked around with his computer cradled in his arms, hoping that its secrets would reveal themselves.

For the next few years, Glenn-Copeland’s free time was spent shovelling snow, feeding his family, and teaching himself how to use his computer to make music. He later recalled that his creative community consisted of trees, bears, and rabbits—“the natural world, that was my companion.” He slept only a few hours a night, kept awake by the conviction that his computer could help him produce sounds that had never been heard before.

Glenn-Copeland, who is a transgender man, was born Beverly in Philadelphia in 1944. (He goes by Glenn, but he retained his birth name after his transition.) His family was middle class and Quaker, and many of the struggles faced by African-Americans seemed abstract to him as a child. His father would sit at the piano for hours a day playing Bach, Chopin, and Mozart, and Glenn-Copeland began learning the German lieder style of singing. He briefly studied with the opera singer Eleanor Steber. Occasionally, his mother would sing him Negro spirituals.

Glenn-Copeland enrolled at McGill University, in Montreal, in 1961, becoming one of its first Black students. At the time, he identified as female. After he was ostracized for being in an openly lesbian relationship, he dropped out and became a folk musician. In the late sixties and early seventies, he recorded a couple of bluesy folk albums that call to mind Joni Mitchell or Odetta, full of the kind of searching, heartbroken songs that one learns to write by listening to other people’s searching, heartbroken songs. Often, they sound as if Glenn-Copeland were trying to fit his operatic range into a narrow band of sentimentality. “So you run to the mirror in search of a reason / But the ice upon your eyelids only reminds you of the season / I don’t despair / Tomorrow may bring roses,” he sings. At first, his vocals are restrained and quivering. But then he lets loose, soaring above the strummed guitars and forlorn pianos.

By the time Glenn-Copeland began teaching himself how to use a computer, he was working in children’s television, writing songs for “Sesame Street” and performing on a Canadian program called “Mr. Dressup.” He had become immersed in Buddhism and its traditions. The music he was making was spacious and unpredictable, nothing like his work from the seventies. Some songs resembled techno anthems slowed to a crawl; others seemed like furtive experiments in rendering the sound of a trickling stream with a synthesizer. Instead of paeans to a lover, there were odes to higher powers and changing seasons, lyrics about spiritual rebirth and the great outdoors. “Ever New” slowly builds, a series of synth lines layering on one another, until Glenn-Copeland finally begins singing: “Welcome the child / Whose hand I hold / Welcome to you both young and old / We are ever new.” He made two hundred cassette copies of an album called “Keyboard Fantasies.” And then, befitting his life philosophy, Glenn-Copeland moved on to the next thing. More snow.”

#beverly glenn-copeland#transgender men#trans masc art#trans masc positivity#trans man artist#trans man musician#trans music#black trans men#will post a link to the documentary about him now that I've found it!

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

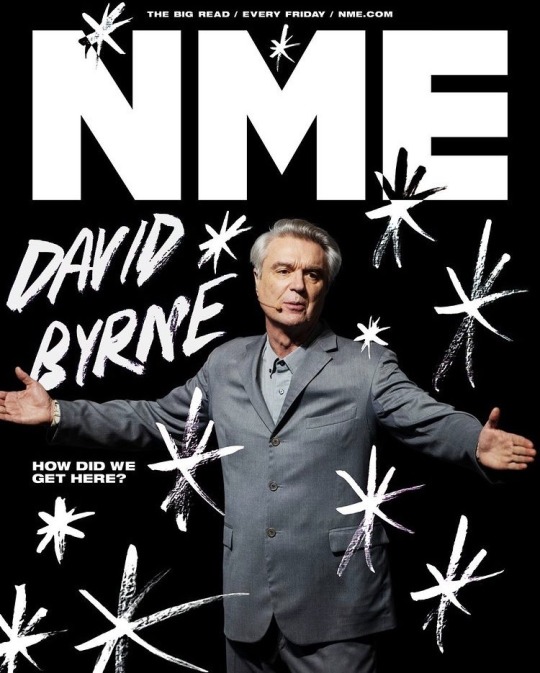

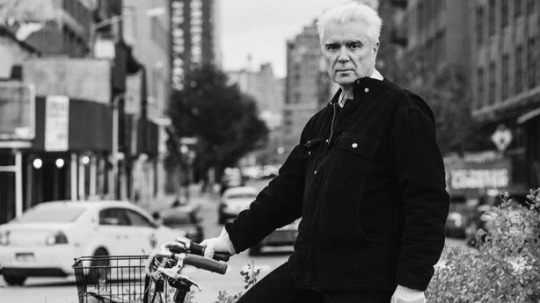

David Byrne’s interview in NME magazine

In 1979, David Byrne predicted Netflix. “It’ll be as easy to hook your computer up to a central television bank as it is to get the week’s groceries,” he told NME’s Max Bell, sitting in a Paris hotel considering the implications of Talking Heads’ dystopian single ‘Life During Wartime’.

He predicted the Apple Watch in that interview too: “[People will] be surrounded by computers the size of wrist watches.” And he foresaw surveillance culture and data harvesting: “Government surveillance becomes inevitable because there’s this dilemma when you have an increase in information storage. A lot of it is for your convenience, but as more information gets on file, it’s bound to be misused.”

In fact, over 40 years ago, he predicted the entire modern-day experience, as if he instinctively knew what was coming. “We’ll be cushioned by amazing technological development,” he said, “but sitting on Salvation Army furniture.”

The 68-year-old Byrne says today, “You can’t say that you know,” chuckling down a Zoom link from his home in New York and belying his reputation for awkwardness by seeming giddily relieved to be talking to someone. “It’s crazy to set yourself up as some sort of prophet. But there’s plenty of people who have done well with books where they claim to predict what’s going on. I suppose sometimes it’s possible to let yourself imagine, ‘Okay – what if?’ This can evolve into something that exists, can evolve into something more substantial, cheaper – these kinds of things.”

It’s been a lifelong gift. Byrne turned up at CBGBs in 1975 with his art school band Talking Heads touting ‘Psycho Killer’, as if predicting the punk scene’s angular melodic evolution, new wave, before punk was even called punk. In 1980, Talking Heads assimilated African beats and textures into their seminal ‘Remain In Light’ album, foreshadowing ‘world music’ and modern music’s globalist melting pot, then used it to warn America of the dangers of consumerism, selfishness and the collapse of civilisation. Pioneering or propheteering, Byrne has been on the front-line of musical evolution for 45 years, collaborating with fellow visionaries from Brian Eno to St Vincent’s Annie Clark, constantly imagining, ‘What if?’

The live music lockdown has been a frustrating freeze frame, but Byrne was already leading the way into music’s new normal. Launched in 2018, the tour to support his 10th solo album, ‘American Utopia’, has now turned into a cinematic marvel courtesy of Spike Lee – the concert film was released in the UK this week. The original tour was acclaimed as a live music revolution. Using remote technology, Byrne was able to remove all of the traditional equipment clutter from the stage and allow his musicians and dancers, in uniform grey suits and barefoot, to roam around a stage lined with curtains of metal chains with their instruments strapped to them. A Marshally distanced gig, if you will.

“As the show was conceptually coming together, I realised that once we had a completely empty stage the rulebook has now been thrown out,” Byrne says. “Now we can go anywhere and do anything. This is completely liberating. It means that people like drummers, for example, who are usually relegated to the back shadows, can now come to the front – all those kinds of things – which changes the whole dynamic.”

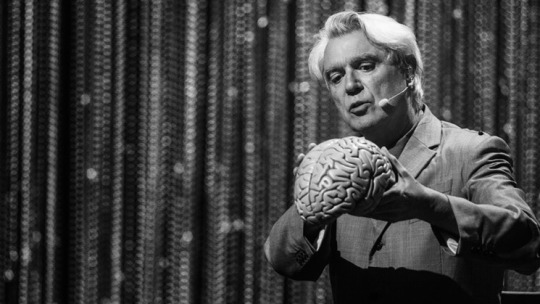

With six performers making up an entire drum kit and Byrne meandering through the choreography trying to navigate a nonsensical world, the show was his most striking and original since he jerked and jived around a constructed-mid-gig band set-up in Jonathan Demme’s legendary 1984 Talking Heads live film Stop Making Sense.

The American Utopia show embarked on a Broadway run last year, where Byrne super-fan Spike Lee saw it twice and leapt at the chance of turning the spectacle into Byrne’s second revolutionary live film, dotted with his musings on the human condition to illuminate the crux of the songs: institutional racism, our lack of modern connection, the erosion of democracy and, on opener ‘Here’, a lecture-like tour of the human brain, Byrne holding aloft a scale model, trying to fathom, ‘How do I work this?’

“I didn’t know how much of a fan Spike was!” Byrne laughs today. “He’d even go, ‘Why don’t you do this song? Why don’t you add this song in’. We knew one another casually so I could text him and say, ‘I want you to come and see our show; I think that you might be interested in making a film of it’.”

Are the days of the traditional stage set-up numbered? “Yes, I think so,” he replies. “At least in theatres and concert halls the size that I would normally play, yes. The fact that we can get the music digitally [means] a performance has to be really of value. It has to be really something special, because that’s where the performers are getting their money and that’s what the audience is paying for. They’re not paying very much for streaming music, but they are paying quite a bit to go and see a performance, so the performance has to give them value for money… It has to be really something to see.”

How does David Byrne envisage the future possibilities of live performance?

“I’ve seen a lot of things that hip-hop artists have done – like the Kanye West show where he emerges on a platform that floats above the stage,” he says. “I’d seen one with Kendrick Lamar where it was pretty much just him on stage, an empty stage with just him on stage and a DJ, somebody with a laptop – that was it. I thought, ‘Wow’. Then he started doing things with huge projections behind. There are lots of ways to do this. I love the idea of working with a band, with live musicians. ‘How can I innovate in this kind of way?’ It’s maybe easier for a hip-hop musician who doesn’t have a band to figure out. The pressure is on to come up with new ways of doing this.”

In liberating his musicians from fixed, immovable positions, American Utopia also acts as a metaphor for freeing our minds from our own ingrained ways of thinking. As Byrne intersperses Talking Heads classics such as ‘Once In A Lifetime’, ‘I Zimbra’ and ‘Road To Nowhere’ with choice solo cuts and tracks from ‘American Utopia’, he also dots the show with musings on an array of post-millennial questions: the health of democracy; the rise of xenophobia and fascism; our increasing reliance on materialism and online communication; the climate change threat; the existential nightmare of the dating app; and, crucially, the distances all of these things put between us.

“The ‘likes’ and friends and connections and everything that the internet enables,” he argues, “even Zoom calls like this, they’re no substitute for really being with other people. Calling social networks ‘social’ is a bit of an exaggeration.”

Byrne closes the show with the suggestion that, rather than isolate behind our LCD barriers, we should try to reconnect with each other. In an age when social media has descended into all-out thought war and anyone can find concocted ‘facts’ to support anything they want to believe, is that realistic?

“I have a little bit of hope,” he says. “Not every day, but some days. I have hope that people will abandon a lot of social media, that they’ll realise how intentionally addictive it is, and they’re actually being used, and that they might enjoy actually being with other people rather than just constantly scrolling through their phone. So, I’m a little bit optimistic that people will, in some ways, use this technology a little bit less than they have.”

A key moment in American Utopia comes with Byrne’s cover of Janelle Monae’s ‘Hell You Talmbout’, a confrontational track shouting the names of African-Americans who have been killed by police or in racially motivated attacks – Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, George Floyd and far, far too many more. Does Byrne think the civil unrest in the wake of Floyd’s death and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement make a serious impact?

“We’ll see how long this continues,” he says, “but in projects that I’m working on – there’s a theatre project I’m working on in Denver, there’s the idea of bringing this show back to Broadway, there’s other projects – those issues came to the fore. Issues of diversity and inclusion and things like that, which were always there. Now they’re being taken more seriously. The producers and theatre owners realise that they can’t push those things aside, that they have to be included in the whole structure of how a show gets put together.”

“At least for now, that seems to be a big change. I see it in TV shows and other areas too. There’s a lot of tokenism, but there’s a lot of real opportunity and changed thinking as well.”

Elsewhere, he encourages his audience to register to vote, and had registration booths at the shows. He must have been pleased about the record turnout in the recent US election? “Yeah, the turnout was great. Now you just got to keep doing that. Gotta keep doing it at all the local elections, too. It was important for me not to endorse a political party or anything in the show but to say, ‘Listen, we can’t have a democracy if you don’t vote. You have to get out there and let your voice be heard and there’s lots of people trying to block it.’ We have to at least try.”

Will Trump’s loss help bring people together after four years with such a divisive influence in charge?

“Yes. I think for me Trump was not so much a shock; we knew who he is. He was around New York before that, in the reality show [The Apprentice], we knew what kind of character he was. What shocked me was how quickly the Republican party all fell into line behind him, behind this guy who’s obviously a racist, misogynist liar and everything else. But it’s kind of encouraging – although it’s taken four years and with some it’s only with the prospect of him being gone – that quite a few have been breaking ranks. There are some possibilities of bridge building being held out.”

But, he says, “It’s too early to celebrate,” concerned that Senate Majority Leader and fairweather Trump loyalist Mitch McConnell will use any Republican control of the Senate to block many of Biden’s policies from coming into effect. “[This] is what happened with Obama… I want to see real change happen. [Climate change] absolutely needs to be a priority. The clock had turned back over the last four years, so there’s a lot to be done. Whether there’s the willpower to do everything that needs to be done, it remains to be seen, but at least now it’s pointing in the right direction.”

How will he look back on the last four years? Byrne ponders. “I’m hoping that I look back at it as a near-miss.”

American Utopia is as much a personal journey as a dissection of modern ills. Ahead of ‘Everybody’s Coming To My House’, Byrne admits to being a rather socially awkward type. He claims that a choir of Detroit teenagers, when singing the song for the accompanying video, had imbued the song with a far more welcoming message than his own rendition, which found him wracked with the fear that his visitors might never leave. How does someone like that deal with celebrity?

“In a certain way it’s a blessing,” Byrne grins, “because I don’t have to go up to people to talk to them – they sometimes come up to me. In other ways it’s a little bit awkward. Celebrity itself seems very superficial and I have to constantly remind myself that your character, your behaviour and the work that you do is what’s important – not how well known you are, not this thing of celebrity. I learned early on it’s pretty easy to get carried away. But it does have its advantages. I had Spike Lee’s phone number, so I could text him.”

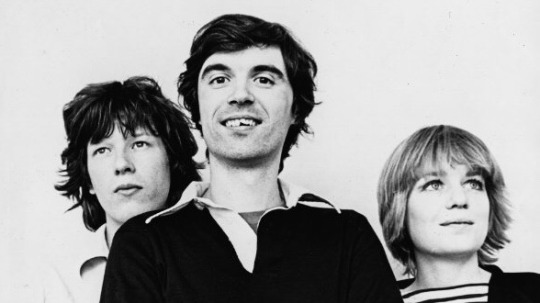

Talking Heads drummer Chris Frantz’s recent book Remain In Love suggests that the more successful Byrne got early on, the more distant he became.

Byrne nods. “I haven’t read the book, but I know that as we became more successful I definitely used some of that to be able to work on other projects. I worked on a dance score with [American choreographer] Twyla Tharp and I worked on a theatre piece with [director] Robert Wilson – other kinds of things – [and] I started working on directing some of the band’s music videos. So I guess I spent less time just hanging out. As often happens with bands, you start off being all best friends and doing everything together and after a while that gets to be a bit much. Everybody develops their own friends and it’s like, ‘I have my own friends too’. Everybody starts to have their own lives.”

The future is far too enticing for David Byrne to consider revisiting the past. “I do live alone so sometimes it would get lonely”, he says of lockdown, but he’s been using his Covid downtime to cycle around undiscovered areas of New York and remain philosophical about the aftermath.

“We’ll see how long before the vaccine is in, before we return to being able to socialise,” he says, “but I’m also wondering, ‘How am I going to look at this year? Am I going to look at it as, “Oh yes, that’s the year that was to some extent taken away from our lives; our lives were put on pause?”’ We kept growing; we kept ageing; we keep eating, but it was almost like this barrier had been put up. It has been a period where, in a good way, it’s led us to question a lot of what we do. You get up in the morning and go, ‘Why am I doing this? What am I doing this for? What’s this about?’ Everything is questioned.”

Post-vaccine, he hopes to “travel a little bit” before looking into plans to bring the ‘American Utopia’ show back to Broadway, and possibly even to London if the financial aspects can be worked out. “Often when a show like that travels, the lead actors might travel,” Byrne explains, “but in this case it’s the entire cast that has to travel. So you’ve got a lot of hotel bills and all that kind of stuff. We wanted to do it. There might be a way, if we can figure that out.”

Once we all get our jab, will everyone come to recognise that, as Byrne sings on ‘American Utopia’s most inspiring track, ‘Every Day Is A Miracle’? “Optimistically, maybe,” he says. “There will be a lot of people who will just go, ‘Let’s get back to normal – get out to the bars, the clubs and discos’. That’s already been happening in New York; there’s been these underground parties where people just can’t help themselves. But after all this it’d be nice to think that people might reassess things a little bit.”

And with the algorithm as the new gatekeeper and technology beginning to subsume the sounds and consumption of music, what does the new wave Nostradamus foresee for rock in the coming decades? Will AIs soon be writing songs for other AIs to consume to inflate the numbers, cutting humanity out of the equation altogether?

“It seems like there’ll be a kind of factory,” Byrne predicts, “an AI factory of things like that, and of newspaper articles and all of this kind of stuff, and it will just exaggerate and duplicate human biases and weaknesses and stupidity. On the other hand, I was part of a panel a while back, and a guy told a story about how his listening habits were Afrofuturism and ambient music – those were his two favourite ways to go. The algorithm tried to find commonalities between the two so it could recommend things to him and he said it was hopeless. Everything it recommended was just horrible because it tried to find commonalities between these two very separate things. This just shows that we’re a little more eclectic than these machines would like to think.”

And in the distant future? Best prepare to welcome your new gloop overlords. Byrne isn’t concerned about The Singularity – the point at which machine intelligence supersedes ours and AI becomes God – but instead believes that future technologies will emulate microbial forms.

“I watched a documentary on slime moulds [a simple slimy organism] the other day,” he says, warming to his sticky theme. “Slime moulds are actually extremely intelligent for being a single-celled organism. They can build networks and bunches of them can communicate. They can learn, they have memories, they can do all these kinds of things that you wouldn’t expect a single-celled organism to be able to do.”

“I started thinking, ‘Well, is there a lesson there for AI and machine learning, of how all these emerging properties could be done with something as simple as a single cell?’ It’s all in there… when things interact, they become greater than the sum of their parts. I thought, okay, maybe the future of AI is not in imitating human brains, but imitating these other kinds of networks, these other kinds of intelligences. Forget about imitating human intelligence – there’s other kinds of intelligence out there, and that might be more fruitful. But I don’t know where that leads.”

His grin says he does know, that he has a vision of our icky soup-world future, but maybe the rest of the species isn’t yet advanced enough to handle it. But if we’re evolving towards disaster rather than utopia, we can trust David Byrne to give us plenty of warning.

December 18, 2020

#david byrne#talking heads#music#new wave#post-punk#art pop#avant funk#worldbeat#interview#nme magazine#2020

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toonami Weekly Recap 8/28/2021

Fena: Pirate Princess EP#04 - The Mystery of the Stone: As the Bonito II sails to the German village of Libar-Oberstein, Fena tries to get her protectors to teach her how to fight, but with little success. Upon arriving in the village, they meet a woman named Arya, who takes them to see her grandfather the Burgomaster. In exchange for Yukimaru sharpening his knife, the Burgomaster offers to help them find the origin of the stone. He tells them that the stone actually came to the village from somewhere in France, but the buyer was listed as La Pucelle d'Orléans, the nickname given to Joan of Arc. However, the listed date of purchase was in 1436, five years after she was burned at the stake, adding to the mystery of the stone. As Fena's crew leave the village, Fena recalls someone mentioning the name "La Pucelle" to her as young child. Meanwhile, Abel grimaces over a painting he calls "La Pucelle" as he continues pursuing Fena.

Yashahime: Princess Half-Demon EP#09 - Meifuku, the Meioju: Konton, one of the Four Perils, destroys a fortress atop a mountain to establish his lair. Jūbei announces that there is a huge bounty on him and Moroha accepts the mission, but Towa and Setsuna refuse, until Jūbei suggests that they should use the money as a reward for info about the Dream Butterfly. The three girls fight Konton, but his armor is too strong for their attacks and they are overpowered until Meifuku, a Meiōjū child appears to rescue them. Meifuku reveals that Konton killed his father and used part of his shell to make his armor. Since then he has searched for Konton in order to retrieve it and give his father a proper funeral. Konton attacks the group and Towa realizes that Konton created his armor by draining the demonic energy from Meifuku's father's shell, returning it to normal by infusing it with her own energy. Without his armor, Konton is forced to flee. Meifuku returns his father's shell so that he can finally pass away, and the girls regret that they could not get the bounty on the enemy's head, while a humiliated Konton swears vengeance on them from inside his new cavern lair.

My Hero Academia Season 5 (Endeavor Agency Arc) EP#105 (17): The Hellish Todoroki Family: A week into the work studies, Endeavor gets a call from Fuyumi who suggests bringing the trio home for dinner. The dinner soon gets uncomfortable as the conversation switches from being about Fuyumi's cooking to how Endeavor prevented Todoroki from eating Natsuo's cooking. Natsuo soon gets up and leaves. After dinner, Midoriya and Bakugo overhear Todoroki and Fuyumi talking about everything. Todoroki says he can't forgive Endeavor so easily for what he did to their mother and is unsure of how to feel. Midoriya tells Todoroki he believes he's getting ready to forgive Endeavor, that it’s fine to not be able to forgive him if he wants. Endeavor thinks about what he can do for his family after all this time and wishes that Toya could’ve been there too. A few days earlier, a hooded man is released from prison and walks around a Christmas-decorated bazaar, gleefully smiling when he comes across a television playing Endeavor's victory over High-End.

Food Wars: The Fourth Plate (Promotion Exams Arc) EP#63 (02) - The Strobe Flashes: As the second round continues, Mimasaka provides Kuga with a bottle of specially prepared smoked soy sauce, reminding everybody that under the rules of a Team Shokugeki, chefs on the same team can help each other. Kuga then starts smoking fried pork with green tea leaves. Meanwhile, Mimasaka faces off against Saitou, a sushi chef, making tuna a perfect ingredient for him. Mimasaka uses an improved version of his Perfect Trace technique, Perfect Trace Flash, to instantly copy Saitou's moves. Mimasaka and Saitou complete their nearly identical sushi dishes, while Rindou completes her Laziji Caiman dish and Megishima finishes his African Ramen. However, Mimasaka and Megishima lose to Rindou and Saitou. Kuga then presents his dish to the judges.

Black Clover: The Spade Kingdom and the Dark Triad Arc EP#163 - Dante vs. the Captain of the Black Bulls: Grey recalls how her stepmother doted on her beautiful stepsisters while she was abused. After receiving her Grimoire she made herself beautiful, causing her stepsisters to attack her. She ran away only to be saved from bandits by Gauche who told her to find some resolve. Grey began assuming her giant scary form to survive, joining the Bulls to be close to Gauche. Desperate not to let Gauche die, Grey uses her transformation magic to turn Gauche’s wound into healed flesh. Dante knocks Asta unconscious and decides he wants both Vanessa and Grey as mistresses, but they are saved when Finral arrives with Yami. Yami shows he can use his Black Hole spell to generate gravitational fields and resist Dante’s gravity. Dante confirms Yami is the arcane mage he needs to cut through dimensions and reach the underworld. Yami responds by slashing Dante’s chest. The Disciples defeat the spirit guardians and begin destroying the Heart Kingdom. Luck challenges the Disciple Svenkin, who can manipulate his body to make it perfectly resistant to any magic, including Luck’s lightning. Disgusted by Svenkin’s selfish personality Luck uses a spell he learned from Gaja and turns himself into a spear of naturally generated lightning, which Svenkin cannot defend against, and shoots himself straight through Svenkin’s chest, defeating him.

youtube

youtube

#Toonami#Toonami Weekly Recap#Toonami Lineup Promo#Toonami Game Review#Fena: Pirate Princess#Yashahime: Princess Half Demon#InuYasha#My Hero Academia#My Hero Academia 5#Endeavor Agency Arc#Food Wars: Shokugeki no Soma#Food Wars: The Fourth Plate#Black Clover#The Spade Kingdom and the Dark Triad Arc

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr 1: Post/Television

The television show that I chose to analyze for this assignment is “How to get away with Murder”. The subject of this show is a lawyer, Annalise Keating, who is a teaching a law class, which she has decided to call “How to get away with Murder”. A group of students are selected to help her on a case, and then eventually used what they learned in class to get away with murder. I do not watch a ton of television, and I honestly chose this show because the title caught my attention. Although I am glad that I chose the title, because it was very interesting.

In my short time of watching the show the first thing I noticed was a prominent black woman played the main character of Annalise Keating, who can be seen in figure 2. One of the previous discussion assignments in this class was based on a documentary, “Through the Lens Darkly”.

Figure 1, Through A Lens Darkly

Through lens darkly was about how when cameras used to be an item not everyone had in their homes, and only white people had them. This meant that only white people photographed black people, and the perspective of the photos was from a white persons point of view. Many of the photos were dark and appeared more grim than photos of white people. In this documentary African American photographers present photos that they took of African American life. These photos tell an entirely different story than the photos of black people that have been viewed earlier in history, a happier and more wholesome picture. Anyways, “How to make a Murderer” is produced by an african american woman, Shonda Rhimes, who is very successful in her career. Rhimes has produced countless other popular television series such as: Grey’s Anatomy, Scandal, and Station 19, among many others. As a successful african american woman Shonda Rhimes is the best candidate to produce a show about a highly successful black female lawyer. Rhimes seems to incorporate small sections which show hardships that Keating may face because of her race. By doing so Rhimes is bringing attention to a problem which is still prevalent in the United States, and hopefully doing something to help correct the problem too.

Figure 2, Annalise Keating

References:

Harris, T. A. (2014). Through A Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People (2014). Uploaded by Family Pictures USA on 2020, June 19 to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THZWSexAjgk.

“How to Get Away with Murder (Season 5).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 18 Aug. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/How_to_Get_Away_with_Murder_(season_5).

“Shonda Rhimes.” IMDb, IMDb.com, www.imdb.com/name/nm0722274/.

“Through a Lens Darkly.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 15 July 2021, www.pbs.org/independentlens/documentaries/through-a-lens-darkly/.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Ellen Holly (born January 16, 1931) is an actress. Beginning her career on stage in the late 1950s, she is known for her role as Carla Gray–Hall on the soap opera One Life to Live (1968–1986). She is noted as the first African American to appear on daytime television. She was born in New York to William Garnet Holly and Grace Holly. She is a life member of The Actors Studio. She began her career on stage appearing in the Broadway productions of Tiger, Tiger Burning Bright, and A Hand Is on the Gate, then embarked on a television and film career. She guest-starred on Sam Benedict and The Nurses. When she began on One Life to Live in October, her African-American heritage was not publicized as part of the storyline; her character, named Carla Benari, was a touring actress of apparently Italian-American heritage. Carla and white physician Dr. Jim Craig fell in love and became engaged, but she was falling for an African-American doctor. When the two kissed onscreen, it was reported that the switchboards were busy fans thought that the show had shown an African-American and white person kissing. The fact that Carla was the African-American Clara Grey posing as white was revealed when Sadie Grey, played by Lillian Hayman, was identified as her mother. Sadie convinced her daughter to embrace her heritage and tell the truth. According to her autobiography One Life: The Autobiography of an African American Actress, she was fired from the show by new executive producer Paul Rauch. She returned to daytime in the long-term recurring role of a judge on Guiding Light. She made a return to the small screen in 2002 when she appeared as Selena Frey in 10,000 Black Men Named George. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence #deltasigmatheta https://www.instagram.com/p/CnefCABrJOE/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

“You need to take serious time for yourself, do self-care, or something,” my best friend Mark said to me, uncomfortably earnestly.

“I’m serious. You haven’t been letting anything in, and you just have to sit and stop running. Go process, or feel, or just let it sink in that you did things and you surprisingly don’t suck.”

Fuck, he’s right.

And so that’s what I’m doing. Last week I booked an Airbnb in La Jolla, a tony coastal enclave of San Diego near where I went to undergrad. I pretended I was on vacation, but in a pandemic. I booked a small studio near the water, and planned to spend these next few days reading, reflecting, walking along the ocean, and staying otherwise indoors and trying to wrestle with this whole semester. I pulled up to the studio last night, unpacked my bags, and cried. Like cried a lot. I felt lonely and scared, but also so numb. I felt a sea of blankness all around me, and a sense of trepidation.

Honestly, I don’t know what to do about all of my stupid feelings.

Where to start?

I feel like I’ve been anxious nearly my whole life. It’s absolutely something that developed as a kid with a violent, drunken father. You learn to live in between heartbeats like that, always testing what’s about to happen, trying to think of the next thing to plan in order to stay safe. Sure, your brain says tauntingly. Things are OK right now, but what if they’re not in a few minutes? Or even worse: Things ARE terrible—what are you going to do if they stay that way forever? These are the gifts Tyrone Tallie Sr left me, along with an unoriginal legal name and a stubborn widows peak visible whenever I grow my hair out for a few weeks.

Couple that with a natural tendency to think quickly, and you have the birth of a personality that masked my calculating self-security by turning those constant permutations into clever moments for interaction or comment. Like many people, my wit is born of trauma; the ability to process things in quick time is born out of needing to feel safe, and frequently gets deployed to put others at ease. That’s one of the weirder contradictory things about being me. I am simultaneously witty and clever and in control, and I am also always quietly freaking out, or at the very least, waiting for the other shoe to drop.

Which is why this has been….a damn semester. Teaching two classes fully remotely with panicked, overwhelmed students in the shadow of an ever-worsening pandemic that stretches on and on without end and feeling daily gaslighted by the endless selfishness of your fellow citizens—what a gift for the anxious. Ironically, anxiety helped to a certain extent because I didn’t have the shock of falling into a new world of uncertainty or fear that so many non-anxious folk did this year. But that’s hardly a gift, is it? Congratulations! You’re already living as if a bomb can go off at any moment, so you’re not struggling to adjust to the new horror show of life!

Teaching this semester has been…just without any context. I’ve taught online, but not in this same planned way and with everyone panicking, and the looming threat of pandemic and election. And yet we did it. We pulled ourselves together, and my students were honest about their needs and their breakdowns and I tried to model humility and grace and confusion and rage as well as they did. We didn’t fuck it up. Or, we all fucked up, and it was okay. We learned things. Students surprised me, and it was glorious. I got to be broken and I didn’t die.

It was an intense semester of overworking as well. I was on a bunch of committees, formal and informal, and we managed to get a new minor—African Studies—passed. I’ll be heading a new program on campus next year, and that’s exciting and terrifying. And on top of all of that, I couldn’t stop volunteering for stuff, or talking about things I cared about. In addition to teaching, I gave fourteen different presentations or talks this semester, an increase in expectations or agreements on my part thanks to the ubiquity of zoom. It grinds on you: the whole, get up, trudge to the back room, power up a personality for the zoom camera, and pour yourself digitally into a screen, only to feel yourself broken into little packets of light and data and scattered across the universe.

The talks went well. The student evaluations went well. Honestly, both were fucking great. And I haven’t let myself feel a goddamn thing. I let it slide off me like rain on a waxed deck, the droplets beading on the slick wood before slipping away into the darkness. I cant let it sink in, because then something good might be happening, and the very skills that have made me capable—the whip-fast reflexes, the self-deprecating humour, the rapid analysis—are also tied to the very deep-seeded anxiety. Everything has to be calculated and understood and prepared for, because at some moment a dark curtain is going to fall over the face of a man with my same name. He will smack me so hard I will go flying out of a chair and hit the wall with a soft, sickly whump, a particularly unpleasant of me at seven that I carry sewn into every cell of my skin and fiber of my being.

I can’t stop and let it sink in because I have internalized the worst calculus of overachiever life—push harder, don’t stop for the good, that’s normal. Stop only for the bad to learn from it, take in its horror, and let it never happen to you again. And so I found myself at the end of the semester holding a bag of relative joy like a party favour, looking around anxiously for bullies to come snatch it out of my hands.

And then Jeopardy fucking happened.

I got to be on television. I got to talk to Alex Trebek, the same man who held my grandmother’s hand on Classic Concentration and saw that her for the beautiful, formidable queen that she was. I got to turn silly trivia knowledge into cash—and I got to do it while being me. And to my confusion—people liked me. It went well, they felt I resonated with something inside of them, and they liked it.

I do not, in my own skill set, have the tools to deal with that. I am supposed to be clever and fast, and witty, and engaging and lovable—but I do not know how to actually think of receiving goodness. I know how to process being witty and clever and delightful—I did what I was supposed to do, good job, next—but I don’t know how to actually take that positivity in.

I keep waiting for all of this to fall apart, for everyone to hate me in the reassuring ways that I distrust or marginalize or disbelieve myself. And yet, I know that’s not helpful. Hence, overachiever’s therapy: forcing oneself to prematurely trade on prize money and spend a three day love/relaxation retreat, less than fifteen miles from my own apartment.

I woke up and cried a little. I then tried to mediate or at least focus on the positives of late. Nope. Nothing came. I decided it was time for coffee. I drank some that I made in the Airbnb, but realized I needed to get outside for a walk. I changed into a bright yellow caftan and an extra-dramatic face mask, and went for a walk on the streets of La Jolla, the bougie and strange bubble by the sea.

La Jolla can double in weird ways like other parts of the world I frequent. It feels sometimes like I’m in Durban (if you’re more partial to Umhlanga Rocks or Durban North) or Wellington (if you love Mount Vic or Oriental Bay), or even Vancouver (if you feel like West Point Grey or the haughtiest parts of Kitsilano are your thing). It’s a rich place, one that I don’t belong in, but one that I can feign a few hours of enjoyment and sun.

Today I walked down palm tree lined streets in the perfect weather, the breeze pushing through my still-short hair with a strange urgency. I picked up a cold brew coffee and a freshly caught and grilled halibut sandwich that my therapist recommended (we decided to briefly be pescatarian for a day and chalked it up to the ‘medical advice.’), then I turned toward the coast. I sat for a long time looking at the waves—unsurprisingly—with a bit of anxiety.

What if I relaxed WRONG? What if I couldn’t let myself feel joy? What if I just wasted the day by…eating this sandwich and not fully appreciating the beautiful ocean waves, golden sun, or nature all around me. After a while I realized that sounded ridiculous, and just forced myself to sit.

And as the old Zulu language dance song “Unamanga” by the late Patricia Majalisa started to filter to my headphones, as I stared out at the sea and the sun, something shifted. I felt something like, I don’t know, a failure in the sealnt around myself, and some drops dripped in, slowly. Maybe, just maybe, I didn’t have to do this in a grand gesture. I could enjoy myself and the small joys I’d found in life so far.

I could be grateful and quietly glad for the little things that happened. It wasn’t about deserving it, or about it being worthy of me. I could imagine for right now, that this was a thing that I could have. I could sit and marvel that some great shit happened to me, and it was OK. Let’s not get it twisted—I didn’t have an epiphany, there were no turnbacks on the road to Emmaus. But I did find a little quietude in my soul for a second and stopped frantically Teflon-ing my heart from joy for a second.

I survived a hell semester, and did well. I got a wonderful opportunity and it went well. I could just let hat happen and also not ignore that it happened, to focus on negatives in an outsized way. I could, in this single afternoon moment, be delighted that things had gone okay. And not worry or strategize about the next disaster, which would happen on its own anyway. And…that’s all I can do right now.

Also, I’m going to work on this more, this whole letting people love me and letting it sink in. I usually avoid it because I feel like it keeps me off my game from the inevitable disaster to follow. But that’s not how I want to live. I’m going to try to think about what it means that some of you all tell me you love me, and then to show it. I need to reconcile the nonstop whirligig of my mind also turns menacingly in on itself so often, and that acknowledging the gift of calculated wit and mirth also means I have to cultivate love and joy.

So tomorrow, I’m going to go for a brief run, I’m going to drink some lovely coffee, and I’m going to walk along the ocean again. (And then I’m going to keep staying in this Airbnb so I don’t catch or spread this plague.)

What a fucking semester, y’all.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think Shonda Rhimes' shows are progressive in terms of race representation and feminism? I was just reading an article that argued that she only seems progressive on the surface but that she acc isnt doing much. Personally I think that she's quite progressive and has kind of paved the way. What about you?

Shonda had this speech about the glass ceiling and how when she got to the ceiling there were these cracks left behind by the Black women before her that allowed her to smash through so I wouldn’t say Shonda paved the way --- we can’t dismiss the successes of women like Yvette Lee Bowser who was the first African American woman to develop her own show (Living Single) or Mara Brock Akil (Girlfriends, The Game) because they paved the way for Shonda. What I will say is that Shonda contributed to that tradition and revitalized the Black Leading Lady --- where, I think Aja Naomi King said that when an actress reads for a show and the person’s race isn’t mentioned you automatically assume she’s white but with the success of Scandal, that assumption isn’t as automatic anymore --- and Shonda produced shows in which Black women onscreen were treated the way white men were treated onscreen and she tapped into fandom culture, she tapped into viewership --- and Kerry Washington was actually the architect of that in the beginning --- and she created a Black female anti-hero with Olivia Pope, which was virtually unheard of, and her umbrella company employs Black female actresses like Viola Davis and Aja Naomi King and Chandra Wilson and Audra McDonald so it’s absolutely not like Shonda didn’t/doesn’t do anything. That’s not accurate. Although every time I’ve seen anything about the writers’ room for Scandal, the writers have been white.

In terms of the content, I can appreciate the even with the success of Scandal, compromises and finagling were still things that had to be done. Grey’s had to be a huge success for Scandal to exist and Scandal had to be a huge success for more Black characters to appear on the show --- with Living Single, for instance, the studio wanted to axe Maxine’s character because she was too unapologetically Black and Yvette had to fight for Max to stay on and then the studio ended up firing TC Carson (Kyle) because he was too outspoken --- so I get that Shonda did at first what, and this is going to sound like a terrible comparison, but what Hertz did with OJ Simpson, which was when they were talking about shooting his commercial, they said they made sure that everyone OJ interacted with in the commercial was white so even though the viewer would obviously know that OJ was Black, because he was interacting with all of these white people, it was like he was “palatable” Black and that’s what Scandal did for a while, sure seeing Kerry Washington looking chic and walking through Washington in commercials was a statement and sure, there was Harrison there in the first few seasons but 99% of the people Olivia interacted with were white and then Papa Pope came in and Shonda is quoted as saying when Papa Pope came in, Blackness came with him.

I’m not really sure how much I agree with that. I think when he has that ‘twice as hard’ speech, it resonated because it’s something Black children hear a lot (as a Black girl I got “three times as hard”) and it fit the scene and it fit the character and it was just so real and you know Maya had a few great lines like when she calls Olivia the help and she thought she was a part of the family and she’s not but it never really goes anywhere, nothing ever comes from any of these self-aware inserts (that in later seasons just become random speeches and to me, anyway, came across as writers trying to appease their viewership) so I don’t think Shonda did anything other than address and there were holes in the show’s own choices.

Like so much of that show is about love and romance and I mean none of it, really, is healthy but all of the what’s supposed to be epic love stories on the show are interracial or white couples --- you know, even when what’s his face, Marcus comes onto the show as the Black activist, he seems to exclusively date white women with the exception of that ridiculous Michaela one night stand --- of course there’s Fitz and Olivia and then Jake and Olivia and then Harrison was supposed to be in love with Adnan or at least had a weird connection to her and then even Olivia’s mother, she never loved Eli but she was meant to have this love affair with Dominic just like how Olivia never loved Edison. Papa Pope calls her out on her fascination with white men but it’s just one line and nothing comes from that, it doesn’t make Olivia take pause, it doesn’t make the writers take pause, it felt like when Mindy Kaling had the episode “Mindy Lahiri is a racist” to kind of poke fun at the idea although less about poking fun in Scandal and more about yeah, we hear you, we’re aware, and then nothing.

There are also no other Black women in this world, not really, for one minute we think she’s going to find someone she can relate to in one of the later seasons and she turns into sexual competition for Fitz? Then there’s the one episode crossover with HTGAWM and that’s kind of it. Even with the clients the gladiators fix, I just remember when the reverend with a whole other family died and the mistress and the wife were duking it out. There was a rotation of Black men but never really of Black women. So I mean, I think Shonda deserves credit for everything she’s done in contemporary television but that doesn’t keep me from being critical of her content.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

* ╰ 𝐡𝐢 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐥𝐮𝐯𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐟𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐛𝐚𝐠 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐬 , i’m your resident crackhead steven forced out of early writing retirement by miss rona but i ain’t complainin ! 🤡 i’m here to bring you a decidedly non - crackheaded muse utilizing the absolute goddess that is zendaya . like got DAMN 𝐥𝐨𝐨𝐤 at her ! i’m swimming with muse for lex so i am hoping my control freak ice queen offers some sort of justice — i cant wait to meet you all and love you down endlessly ! if you could spare a 𝐡𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐭 for my validation , i’ll offer you all my best plots in return ! 💖

𝒂𝒃𝒐𝒖𝒕

❛ ✶ ( ZENDAYA , CIS - FEMALE , SHE / HER ) spotted ! ALEXANDRIA ‘ LEX ’ GOLDMAN was spotted singing along to BOSS BITCH by DOJA CAT in hilton grove. you’ve heard of them right ? they are a TWENTY - TWO year old ACTRESS & ENTREPRENEUR who has already amassed a net worth of $31M. you should really follow them on insta @GOLDEN , they’re about to hit 39.1M followers. the tabloids have been calling them the EXECUTIVE because they are known for being + PURPOSEFUL but also a bit - AUSTERE. — ooc info ( steven . 21 . pst . she / her / they / them . )

𝒔𝒕𝒂𝒕𝒔

full name : alexandria ( defender of man ) rochelle ( little rock ) goldman ( little golden one ) nicknames : primarily goes by lex . lexie , xan on occasion , and gold / goldie . birthday & age : september 3rd / 22 years old zodiac : virgo gender & pronouns : cis - female , she / her / hers orientation : openly bisexual nationality : american ethnicity : mixed race — african - american , german , irish , english , scottish occupation : former beauty pageant competitor and 2016’s miss teen usa , current film and television actress , model , business entrepreneur , and activist . recognized for : starring in hbo’s television series euphoria , being the first openly queer representative for the usa in the pageant circuit , her advocacy for feminism and criminal justice reform , a bustling social media page , being one of forbes 2019′s top 30 under 30 . char . inspos : meredith grey from grey’s anatomy , spencer hastings from pretty little liars , hermione granger from harry potter , meghan markle , angela martin from the office , alex cabot from law and order svu , and more than anything , claire from fleabag . 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐢𝐟 𝐮 𝐬𝐤𝐢𝐦 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐞𝐥𝐬𝐞 , 𝐢 𝐛𝐞𝐠 𝐨𝐟 𝐮 𝐭𝐨 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐜𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐨 𝐣𝐮𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐠𝐞𝐭 𝐥𝐞𝐱’𝐬 𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝟑 𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐬 . tropes : control freak , defrosting the ice queen , perpetual frowner , did you think i can’t feel ? , hidden depths , stepford smiler . aesthetics : an intellect that remembers everything ; wild caramel curls with just enough composure to seem effortless ; a fear of failure more crippling than life itself ; the smell of fresh linen and lavender ; a color - coded itinerary ; a perfectly choreographed interaction , each time ; lilac power - suits and an immaculate composure ; unspoken mommy issues ; tenebrous , intent gazes swimming with the resonance of unspoken thoughts ; ‘ don’t touch me please ‘ syndrome ; kicking out hookups before you both fall asleep ; ordering the same thing at a restaurant , every time ; flinching at ‘ i love you’s ’ ; drafting business emails at the club ; an admiration of atlas , with the world’s weight upon your shoulders .

𝒃𝒂𝒄𝒌𝒔𝒕𝒐𝒓𝒚

born the sole continuance of the goldman name to a mother whose pregnancy was all but a career death - sentence , lex bore the weight of the world’s expectations on graceful shoulders from the moment she came into the light . lieutenant olivia goldman , head of the manhattan police department , can deny the salacious accused affair with the district attorney until she’s blue in the face but can’t deny the consequence of their tryst , alexandria being a painful reminder of losing nearly all her mother’s years of hard work while her father simply denied her existence and lived none the more guilted . from the start , the odds were stacked against the goldman progeny , pushing perfection as her only claim to some semblance of attention from liutenant goldman .

as a mixed race child to a white unwed mother in law enforcement , working 80 hours weeks and having spent years building her career , there was little lex saw of her mother that wasn’t something resembling exhaustion or utter disinterest . this forces her to grow independent at an astounding pace , keeping to herself as to not bother her mother with her own whims or desires . at 12 , her mother is courted by an award - winning director who requests her guidance on a police film he’s submitting — she refuses to advise on the film , but goes to dinner with him as a courtesy , and they’re married a year later in a lavish hamptons wedding in the summer . rudy delano is a world -renowned director along the likes of steven spielberg , and takes to lex like she were his own daughter . as if to balance out olivia’s coldness and detachment , he showers lex in adoration and support , encouraging her to pursue her interests of pageantry when she voices them following her 7th grade year .