#Yser WW1

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

WW1 battlefield tour ephemera - 1929 by Frederick Via Flickr: This is an original map, excursions leaflet, and tickets for a WW1 Yser battlefield tour that took place on 18 Aug 1929. The tour organisers are 'The British Touring Cars (Excursions by Luxurious Motor Cars)'. Being just 11 years after the end of WW1 many people went on a sort of pilgrimage to the battlefields where their loved ones had died to try in some small way to come to terms with the loss. Itinerary - Ostende, Middelkerke, Niuupoirt, Ramscapelle, Pervyse, Dixmude, canal de l'Yser, Woumen, Chateau Blankaert, Steenstraete, Boesinghe, Ypres (lunch), return by Hill (Hell?) Fire Corner, Hill 60, St-Jean, St-Julien, Poelcapelle, Foret d'Houthulst, Houthulst, Dixmude, Beerst, Couckelaere, Moere, big gun, Leffinghe, Ostend. ---------------------------------------------------- If there are any errors in the above please let me know. Thanks. Any photograph, ephemera, etc I post on Flickr is in my possession, nothing is copied from another location. The original photographer may have taken copies from their original negative and passed them out (sold them?) so there may be other copies out there of your (and my) 'original' transport photo, although occasionally there may be 'holiday snaps' type photos where there are not any other photos exactly the same in existence. If you wish to use this image (bearing in mind it may not be my copyright) or obtain a full size version (most of my uploads are small size) please contact me.

#British Touring Cars#transport ephemera#WW1 battlefield tour#battlefields visit#WW1 map#Yser battlefields#Yser WW1#battlefields tour map#WW1 battlefields#WW1 ephemera

1 note

·

View note

Text

Prologue Part 7: Counter attack, digging in, and the settlement of the Western Front

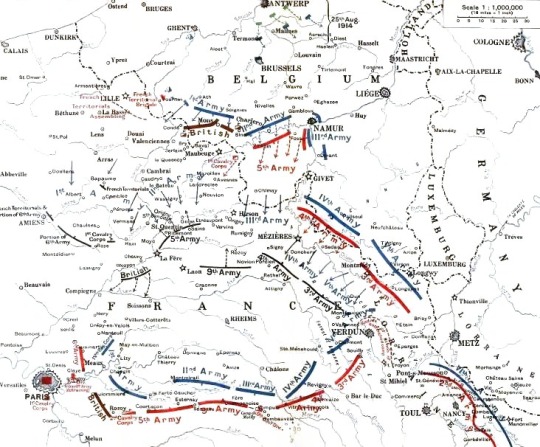

German, BEF and French army positions Aug 23-Sept 5 1914, Wikipedia (click text to enlarge)

The Battle of the Frontiers had been a catastrophe. British and French forces across the line were rapidly being pushed south. The Great Retreat was fully underway. Starting on August 24, the German 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th Armies would advance nearly 250 miles into France.

The commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), Sir John French, having lost faith in the ability of France to defend herself, began to make plans to retreat to the coast and evacuate his army from the continent. In the final days of August soldiers of the German 1st Army, just ten miles outside of Paris, could see the Eiffel Tower in the distance. To say that the situation was dire for France would be an understatement. However, at this moment, a window of opportunity was presented that would change the entire course of the war. The window opened slightly on September 1 when British Secretary of War Lord Herbert Kitchener ordered the BEF commander to keep his army in France.

At the start of the war retired French General Joseph Gallieni had been called back into service and named Military Governor of Paris. On September 2, Gallieni told his Commander in Chief, Joseph Joffre, that he needed more resources to protect the capitol. Despite his dislike of Gallieni, and the desire to use these forced elsewhere in battle, Joffre placed the newly created French 6th Army under Gallieni’s control. Augmented by additional troops, including a brigade from Morocco and a division from Algeria, the 6th Army was led by General Michel-Joseph Maunoury. The window opened a bit more with this addition of this new force to the French line.

German 1st Army General Alexander von Kluck, photo Wikipedia

Commander of the German 1st Army, General Alexander von Kluck, had been aggressively pursuing the retreating French forces since August 24. The German Schlieffen Plan for war against France stated that the German 1st Army was to advance on the west side of Paris while the 2nd Army, under General Karl von Bulow, was to advance on the east. The two armies would then surround and capture Paris from both directions. But von Bulow was much more cautious than von Kluck. While the 1st Army was ten miles north of Paris, von Bulow directed his 2nd Army to stop 30 miles from Paris in anticipation of a French counter attack. With von Kluck far in advance of von Bulow, too much distance existed between the German 1st and 2nd Armies. Von Kluck was ordered to move 1st Army to support the 2nd Army. On August 31, in total disregard for the Schlieffen Plan, von Kluck swung the entire 1st Army to the southeast, away from Paris, and towards von Bulow and 2nd Army. This is the now infamous “Von Kluck’s Turn”. The German soldiers of the 1st Army, thrilled at the vision of Paris growing larger in front of them, were confused to see the city moving off to their right side as they marched forward. In addition to skipping the capture of Paris, von Kluck’s maneuver had created a 30-mile gap in the German line. Unknown to von Kluck, he was also exposing his entire right flank to a force he did not know existed: Maunoury, and the new French 6th Army. In three days the French would realize what was happening and the window of opportunity would be opened wider. Winston Churchill, in his book The World Crisis 1911-1918 wrote:

It was upon these indications, confirmed again by British aviators on the 3rd, the Gallieni acted. Assuredly no human brain had conceived the design, nor had human hand set the pieces on the board. Several separate and discrepant series of events had flowed together. First, the man Gallieni is on the spot. Fixed in his fortress, he could not move towards the battle; so the mighty battle has been made to come to him. Second-the weapon had been placed in his hands-the army of Maunoury. It was given him for one purpose, the defense of Paris; he will use it for another-a decisive maneuver in the field. It was given him against the wish of Joffre. It will prove the means of Joffre’s salvation. Third, the Opportunity: Kluck, swinging forward in hot pursuit of, as he believed, the routed British and demoralized French, will present his whole right flank and rear as he passes Paris to Gallieni with Maunoury in his hand. Observe, not one of these factors would have counted without the other two. All are interdependent; all are here, and all are here now.

Gallieni realized the position in a flash. “I dare not believe it,” he exclaimed; “it is too good to be true.” But it is true. Confirmation arrives hour by hour. He vibrates with enthusiasm.

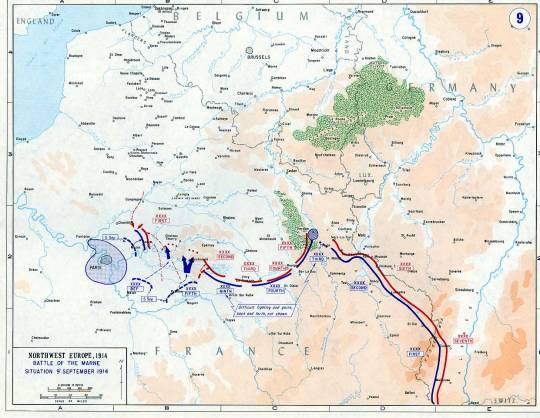

Position of forces before the Battle of the Marne, Wikipedia (click text to enlarge)

Joffre sees the opportunity as well, and intends to take full advantage of it. The time for timidity is over. The Great Retreat is halted and French forces are turned around to attack. By this point numerous French generals have been sacked by Joffre. They have been replaced with more aggressive commanders, including Ferdinand Foch and Philippe Petain. But there is one general that Joffre can’t replace and who does not report to him, BEF commander General French. The French commander desperately needed the BEF to join the counter attack. Joffre traveled to meet with the BEF commander and during their discussion Joffre slams his hand down on a table exclaiming “Monsieur le Maréchal, c’est la France qui vous supplie!” (Marshal, France is begging you!). Sir John French attempted a reply in French, stumbles, and finally tells an aide “Damn it, I can’t explain. Tell him that all our men can do our fellows will do”. The BEF will join the Battle of the Marne. Joffre directs his forces to attack on September 4 and the French 6th Army made contact with the Germans near the River Marne on the next day.

Taxi de la Marne at Les Invalides Paris April 2018

Fully engaged in battle, von Kluck wheeled the 1st Army west to face the French 6th Army on September 5. In doing so he opens another gap between his forces and von Bulow’s 2nd Army. Confusion between the German commanders caused the gap to open wider and on September 6 the BEF and French 5th Army took the advantage. Two days of ferocious battle followed and this time it was the Germans that were pushed back. On September 7 the French 6th Army was reinforced with 10,000 reserve troops, 3000 of which were delivered to the front via a 30-mile taxi cab ride from Paris. General Gallieni arranged for 600 taxis to transport the soldiers and the taxi companies were reimbursed the 70,000 francs for the expense. The Taxis de la Marne was the first large scale use of motorized infantry in battle and the taxis would become iconic in French history.

French soldiers charge at the Battle of the Marne, photo Wikipedia

The tide had turned and by September 8 it looked like the German 2nd Army was in danger of being surrounded. Von Bulow was forced to retreat and, much to the objection of the still aggressive von Kluck, the German 1st Army was forced to fall back as well. Chief of the German General Staff Helmuth von Moltke, who had been suffering from the immense stress of command since the war began a month ago, collapsed upon hearing the news that German forces were in retreat. The Schlieffen Plan had failed and the fate of Germany was in question. Upon recovery, von Moltke is reported to have told the Kaiser “Your Majesty, we have lost the war.” France would not be defeated before Russian mobilization was complete. The nightmare of a two front war was now a reality for the German Empire. Von Moltke was replaced as German military commander on September 14 and would die from stroke in June 1916.

The German retreat continued for almost a week. Upon crossing the River Aisne in northern France, German soldiers stopped on the higher ground, began to dig in, and prepared to defend themselves against the advancing French forces. For two weeks the First Battle of the Aisne would rage until a front line stabilized. Similar fronts would establish themselves to the east all the way to the Swiss border. Trenches, first dug by the Germans, were also built by the French.

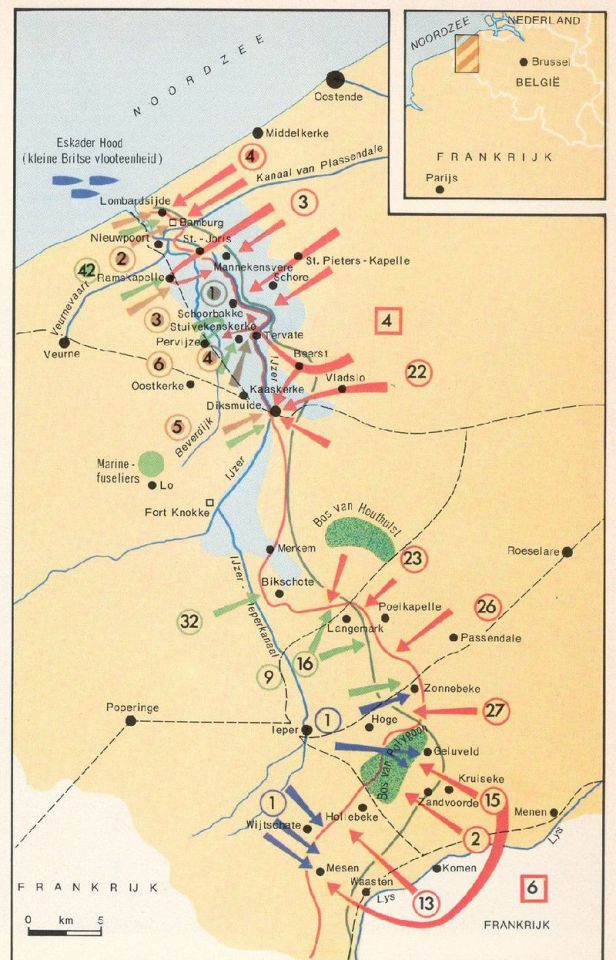

The “Race to the Sea” and the flooding of Belgium October 1914, Wikipedia (click text to enlarge)

To the west, the month long “Race to the Sea” began. Reaching the sea was not the goal however. Instead, the BEF/French and German forces attempted to turn each other’s flank and find a weakness. Neither force could outflank the other and eventually the armies ran out of land in which to try and make the turn, they had reached the English Channel.

Driven out of Antwerp by German forces, Belgian King Albert I and his army, along with French forces, made a stand along the Yser River in western Belgium. On October 25 the German offensive was so fierce that Belgians made a decision to open the floodgates in Nieuwpoort and let in sea water from the channel. Ten square miles of Belgian farmland was flooded by salt water and the Germans were held back. The Belgian Army would remain behind the safety of this artificial lake for the next four years.

Langemarck Belgium November 1914, photo Wikipedia

The First Battle of Ypres took place from October 22 to November 22 and achieved no definitive results other than the additional loss of life. The war, which had been expected to last six weeks, was by this point four months old. Armies were short on supplies and ammunition. Morale was low and soldiers were exhausted. German reservists, thrown into battle without adequate training, attacked at Langemarck and suffered horrible casualties. The professional ranks of the BEF, 80,000 solders strong at the start of the war, had been all but wiped out. The British would need to rebuild their army and they would require help from their colonial territories in order to do it. By the end of 1914 German and French casualties had reached 1.5 million men, almost equally split between the two combatants. That’s ten thousand casualties per day, on average, for the first five months of war alone. How could any of this be sustainable?

German General Erich von Falkenhayn, who had replaced von Moltke in September, decided upon a strategy of attrition. The Germans would hold on to the territory they had gained and force the French and their allies to try to root them out. Falkenhayn believed the cost would be so great in casualties and material that the French would eventually be forced negotiate for peace. Trenches were dug and reinforced. Machine gun and artillery positions were cleared and improved. The entire Western Front was defined and stabilized from the English Channel to Switzerland. By and large, the front would not move in any significant way until 1918. It would take another force, a fresh belligerent with a nearly limitless supply of man and materials, to enter the war before the balance of power would start to tip.

What was to come? Neuve Chapelle, Second Ypres, Loos, Verdun, The Somme, the Nivelle Offensive, the Battle of Messines and Third Ypres, the Battle of Cambrai, the Kaiserschlacht, Belleau Wood, the Battle of Amines and the Black Day of the German Army, Meuse-Argonne, villages pounded into dust, pointless attacks with nothing to show for it, poison gas, ground turned to soup by artillery shells, innovations in warfare like tanks and airplanes, reinforced bunkers and underground mines, and conditions that would drive men past the edge of their sanity; all would take place along the Western Front of the Great War over the next four years.

Next Up - Prologue Part 8, The Belligerents: United States

December 23, 2018

#ww1#worldwar1#westernfront#greatwar#schlieffen#vonmoltke#vonkluck#vonbulow#french#german#british#bef#joffre#falkenhayn#ypres#marne#yser#belgium#france

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

© IWM (Q 10637) Soldiers fishing in the Yser Canal near Boesinghe, 28 January 1918. One is using a rifle as a fishing rod, the other a barbed-wire 'corkscrew' support.

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Crossing the Yser Canal during the Battle of Flanders

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Operation Beach Party”

A German trench mortar unit on the coastal dunes.

July 10 1917, Nieuport [Nieuwpoort]--In recent weeks, the Germans had noticed a buildup along the Belgian coast, the extreme northern end of the Western Front. British troops had replaced French ones, and Allied artillery fire had picked up. In fact, the British were preparing for amphibious landings along the Belgian coast just behind the front line, in an attempt use their naval advantage to outflank the Germans and potentially capture the German U-boat ports in Belgium. The Germans began to make preparations to counter such a move, which included an attack on the British lines near the coast, hoping to forestall any British advance on land. This attack was called Operation Strandfest; literally “Operation Beach Party.”

The Germans opened with an artillery barrage early in the morning of July 10. The British positions on the coast were particularly vulnerable. Located on the east bank of the Yser river, they were quickly cut off when the German artillery destroyed the bridges over the Yser. The sandy terrain also meant that their fortifications were rudimentary and were quickly destroyed. Some units took 80% casualties from the bombardment alone. When the German infantry attacked in the evening, the remaining defenders fought valiantly (two platoons resisting to the last man), but they were quickly overwhelmed; the Germans reached the Yser and captured over 1000 prisoners of war. From the two battalions closest to the sea, only 68 men escaped, all by swimming the Yser at night.

Today in 1916: Cesare Battisti Captured and Executed by Austrians Today in 1915: Reaction to the German Lusitania Note in the German-American Press Today in 1914: Russian Ambassador To Serbia Dies in the Austrian Embassy

#wwi#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#world war 1#belgium#Western Front#the great war#yser#the first world war#world war i#world war one#july 1917

100 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yser Tower, built in remembrance to WW1, dynamited and rebuilt taller after WW2 and now a popular monument for the extreme right movement in Flanders

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday, Joe English (1882-1918)

Called up to military service at the outbreak of WW1, Joe was sent to the front. He became the official war artist of the Belgian Army and designed the headstones that commemorated the lives of Flemish soldiers killed during the war. He also painted many pictures, designed posters and drew sketches and cartoons. Joe died of an untreated appendicitis in the military hospital on 31st August 1918. He was buried in the military cemetery at Steenkerke in Belgium. In 1930, his body was re-buried in the crypt of the Yser Tower, which was constructed in 1925.

Every year there is a Flemish national gathering called The IJzerbedevaart (Pilgrimage of the Yser) which has been held annually since 1920, the first one being held at the grave of Joe English.

Self Portrait.

0 notes

Photo

The First Battle of Ypres ,19th October – 22 November 1914) was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. The battle was part of the First Battle of Flanders, in which German, French, Belgian armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) fought from Arras in France to Nieuport on the Belgian coast, from 10 October to mid-November. The battles at Ypres began at the end of the Race to the Sea, reciprocal attempts by the German and Franco-British armies to advance past the northern flank of their opponents. North of Ypres, the fighting continued in the Battle of the Yser (16–31 October), between the German 4th Army, the Belgian army and French marines. #ypres #battleofypres #ww1 #firstworldwar #war #england #france #germany #belgium #britishempire #germanempire https://www.instagram.com/p/B4chU7zA_K0/?igshid=jvsucytvkc0i

#ypres#battleofypres#ww1#firstworldwar#war#england#france#germany#belgium#britishempire#germanempire

0 notes

Photo

2 WW1 Medals Belgium Yser Combat & Commemorative Best Ever ! $82.00 https://ebay.to/2ZEtLJs

0 notes

Photo

A German observation post on the Yser Front, Belgium, 1917. #war #history #vintage #retro #guns #gun #ww1 #tank #tanks #1910s #military #battle #warrior #warriors #combat #campaign #battles #wwi #worldwarone #thegreatwar

#thegreatwar#gun#war#battle#wwi#1910s#tank#guns#vintage#ww1#tanks#warrior#combat#military#battles#warriors#worldwarone#history#campaign#retro

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

World War I (Part 23): Flanders Fields

The Germans had withdrawn from the Marne, moving back northwards. The British and French were astonished and pleased at this, but they themselves were struggling. They were exhausted, running low on essential equipment, and had taken many casualties. One English soldier wrote, “After five days and nights of fighting, decimated, spent and hungry, we are lying on the bare earth, with only one desire in our hearts – to get ourselves killed.”

Also, they were short on artillery shells. The intensity of this war was more than they'd expected – only 10,000 rounds were being produced per day for the 75mm cannon (their most effective field artillery), and this was only a fifth of what they needed.

The British & French could have exploited the gap (between Kluck & Bülow) that had forced the withdrawal, or closed on the Germans as they retreated. But they didn't do this. Meanwhile, the German First, Second and Third Armies had taken fortified positions on high ground, north of the Aisne River (this was the next east-west river north of the Marne). By the time the Entente forces attacked them, it was too late to take advantage of their retreat. And the Germans had some of France's richest mining & industrial areas.

A German officer wrote to his parents, “Three days ago our division took possession of these heights and dug itself in. Two days ago, early in the morning, we were attacked by an immensely superior English force, one brigade and two battalions, and were turned out of our positions. The fellows took five guns from us. It was a tremendous hand-to-hand fight. How I escaped myself I am not clear. I then had to bring up supports on foot...and with the help of the artillery we drove the fellows out of the position again. Our machine guns did excellent work; the English fell in heaps.”

He continued, “During the first two days of the battle I had only one piece of bread and no water. I spent the night in the rain without my overcoat. The rest of my kit was on the horses which had been left behind with the baggage and which cannot come up into the battle because as soon as you put your nose up from behind cover the bullets whistle. War is terrible. We are all hoping that a decisive battle will end the war.”

The Germans made a final attempt to capture the fort of Verdun, on the eastern part of the Western Front. If they succeeded, the fort would be an anchoring strongpoint for their line, and enable them to keep their armies on the Marne. But they failed to capture it, and so were forced to pull pack. They had to abandon important territory – including the railway junctions of Amiens, Arras and Reims.

The Entente leadership was enthusiastic and optimistic. JF predicted that his troops would be in Berlin within 6 weeks.

Helmuth von Moltke had been reassigned (illness was given as the reason), and replaced by the (now former) Minister of War General Erich von Falkenhayn. He saw that the war would be a long one, and he tried to get Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to achieve a negotiated settlement, on either of their fronts. They could perhaps get a negotiated peace with Russia, which would persuade France to also come to terms. The USA had already offered to be a mediator, and Denmark would soon do the same. But it was too late for a negotiated peace – none of the countries involved in the war wanted to accept a settlement in which they hadn't won anything, because they thought that otherwise the thousands of deaths wouldn't be justified. So, they thought, they had to keep on fighting, to make it worthwhile.

Within days of taking command, Falkenhayn began developing plans for a new offensive. He began putting these plans in motion before the end of September. There were two goals: 1) to solve the problem of their exposed right flank, which was currently north of Paris; 2) to capture Antwerp. Antwerp was the last great stronghold of the Belgian army, and the greatest port on the north coast. So long as it remained in Belgian hands, it was a place from which the British & Belgians could strike at Germany's lines of supply.

Falkenhayn could have solved the first problem by withdrawing even further north – to a line running from the Aisne to Brussels, or even east of Antwerp. But this would be terrible for morale, as it would give up nearly all of what Moltke's offensive had gained, and the public would have been furious.

So instead, he took an offensive approach. He decided to extend the line westward along the River Somme, all the way to the Atlantic. (The Somme was north-west-ish of the Aisne, and flowed into the Atlantic Ocean on the west coast of France.) This would be possible if the French failed to defend the area north-west of Paris. If they succeeded, they'd control all of northern France, including all the ports on the English Channel. And then they would be in an excellent position to resume the advance on Paris from east and west.

Map showing the Somme.

But, like Kluck and Moltke, Falkenhayn was trying to do too much, with not enough troops. He moved the Sixth and Seventh Armies from Alsace & Lorraine to his right, to strengthen it. (They would be replaced by two of the new armies which were being formed.) This was quite difficult to do, because there was only one railway line directly connecting the German right & left, and it took 140 trains to move a single army.

The German offensive westward along the Somme wasn't as strong as it could have been. (Part of the reason for this was the delays caused by the railway issue.) They ran into a new French Tenth Army and were stopped.

Antwerp, the second goal, was even more strongly-fortified than Liège. It was surrounded by 19 huge, powerful, modern forts, and also some smaller ones. Nearly 100,000 troops defended it. But it seemed more achievable than Falkenhayn's first goal.

Before Germany began moving their siege guns to Antwerp, Henry Wilson (JF's deputy chief of staff) suggested that the BEF be moved to its original position, past the end of the French left. Because of how the French line had shifted, it would mean they had to move to the Flanders region, in western Belgium. Wilson said that they'd be closer to the ports, and therefore closer to their supplies, reinforcements & communications.

JF was reluctant at first – probably because having the BEF between two of the French armies meant their flanks were protected. But Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty) told him that this new position mean that the Royal Navy could protect them from the English Channel, and JF changed his mind. He was a career cavalryman, and he was beginning to see that Flanders' flat terrain would be an excellent place for his cavalry to prove their worth at last. From there, they could begin an advance into central Belgium, and from there to Germany.

Ieper = Ypres.

But Joffre was not so sure about the move. He was afraid that this new position would make it easy for the British to withdraw back home if JF wanted to. However, JF announced that he was moving north anyway, whether Joffre liked it or not. Joffre urged him to move slowly and cautiously, but the British moved quickly.

Soon, Joffre was blaming their speed for the success of the Germans' attacks along the River Aisne. He also blamed the Germans' capture of Lille (a French industrial city near the Belgian border) on the fact that JF had commandeered railcars, which were scarce.

By now, Joffre had realized that Falkenhayn's movement of troops and guns towards Antwerp meant his left was again in danger. So he moved the Second Army (now commanded by Foch) north into Flanders with the British. The BEF's planned position was west of Ypres – a lace-manufacturing Belgian town. Ypres was the centre of a road network which led east into central Belgium, and west towards France & the Channel ports.

When Germany began attacking Antwerp with their artillery, the British were alarmed (more so than the French were). Antwerp was a major port, and very close to England. Churchill had only a small force of marines available, and he quickly sent them to help defend it. He came with them, and met with Belgium's king and queen, and then with the Belgian commanders.

He then telegraphed the British government, suggesting that they replace him as First Lord of the Admiralty, and appoint him as the British military commander in Antwerp. Some of the cabinet members apparently laughed at this – it was typical Winston, they thought, eager for adventure and full of wild ideas. But Kitchener knew him fairly well, and was impressed by him. He knew that Churchill had been one of the few to recognize the Channel ports' importance) even before the Germans began retreating from the Marne), and to urge that something be done to secure them (nothing had been done, though). Kitchener proposed that Churchill be made a Lieutenant General, but Asquith disagreed.

The Germans were shelling Antwerp around the clock. On October 6th, the Belgians decided that Antwerp couldn't be saved, and they'd have to give it up in order to save their army. Churchill went back to Britain. The next day, 60,000 demoralized Belgian troops left Antwerp, under the command of the king, and hurried west until they were almost in France.

They were then organized into a defensive line north of Ypres, and north of the River Yser, which flowed into the Atlantic & formed a natural barrier. Then they waited, while the French Second Army began to extend their line to the south, and British troops marched into Ypres from the west.

Meanwhile, the Germans were taking possession of Antwerp. Four corps (almost a whole army) were now freed up. Whole corps of new, barely-trained reserves were arriving in Belgium from Germany. Many of them were student volunteers.

Over in the east, the fighting was stretched over 800km of front. Hindenburg & Ludendorff had to deal not only with the Russian threat to East Prussia, but also the threat to Silesia, to their south. And even further south, the Austrians were struggling.

The Germans had to achieve two things. 1) They had to move south to connect with Austria's left before they were overrun by the Russians. And 2) since they didn't have enough troops to defend every threatened area, they would have to go on the offensive – to deal a huge blow to Russia before it was too late.

Max Hoffmann was chief of operations, and he, Hindenburg & Ludendorff decided that they could achieve both these things by taking the new Ninth Army south (by railway) to around Warsaw, in Russian Poland. (Warsaw was an important base of operations for Russia.) There, they could link up with the Austrian left [in a north-south line?], and together they could fight the four Russian armies that were advancing on Silesia. These armies were sent by the Russian Commander-in-Chief, the Grand Duke Nicholas Romanov (who was the tsar's cousin).

Map showing Silesia.

The Eighth Army, which had won the Battle of Tannenberg, would stay behind to guard East Prussia. Ludendorff wanted to send part of it south with the Ninth, but Falkenhayn deemed it too risky.

The battle ahead would be the Battle of the Vistula River (September 29th – October 31st). It is sometimes called the Battle of Warsaw.

Map showing the region of the Battle of the Vistula River. Ignore the blue & red lines.

18 German & Austrian divisions ended up facing 60 Russian divisions, who were advancing on a 400km-wide front. The Austrians, in the southern part of the line, were meant to break the Russian line there by advancing west across the River San in Galicia. However, they failed to do this.

In the north, the German right & centre moved quickly at first, but then days of torrential rain slowed them down. An officer in charge of munitional transports wrote: “From Częstochowa [modern-day southern Poland] we advanced in forced marches. During the first two days roads were passable, but after that they became terrible, as it rained every day. In some places there were no roads left, nothing but mud and swamps. Once it took us a full hour to move one wagon, loaded with munitions and drawn by fifteen horses, a distance of only 15 metres...Horses sank into the mud up to their bodies and wagons up to their axles...One night we reached a spot which was absolutely impassable. The only way to get around it was through a dense forest, but before we could get through there it was necessary to cut an opening through the trees. For the next few hours we felled trees for a distance of over 500 metres.”

Because of their slowness, the Russians had time to organize their forces and counterattack. The German left was slowly bent back, and ended up facing north instead of east, in shambles.

By October 17th, the Germans realized it was hopeless and they had to withdraw. The Ninth Army retreated nearly 100km in the space of 6 days. By the time it escaped the Russians, it had lost 40,000 men.

The Germans took 100,000 casualties in total, including 36,000 dead. The Austrians took 40-50,000 casualties. The Grand Duke Nicholas began reassembling his forces to resume their advance (after pulling their guns out of the slime).

While the Germans were beginning to retreat from Warsaw, JF was beginning to move some of his forces eastwards in Flanders. And at the same time, Falkenhayn was moving some of his forces westwards over neighbouring ground. Neither side expected to encounter a large enemy force – until just hours before their armies crashed into each other.

The British wanted to reach Brussels via Ghent. The Germans wanted the region directly west of Belgium (which had port towns). Both JF and Falkenhayn knew that if they could advance far enough, they might be able to turn away from the sea & encircle the enemy.

Almost immediately, both sides ran into the enemy. A French/British advance towards Ghent ran into Falkenhayn's main forcve, and was thrown back. The Germans tried to break through the Belgian line north of the Yser, but they were stopped as well. This began the First Battle of Ypres (October 19th – November 30th).

The fighting was worst between the Germans and Belgians. For the Belgians, the waterlogged ground of the Flemish lowlands made it impossible to dig in. The Germans had to try to cross the Yser while the British navy shelled them from the nearby English Channel. Winter was approaching, and the troops were constantly wet and half-frozen.

King Albert led the Belgian troops. He was a courageous, capable soldier. Foch had warned him that if he didn't manage to hold this last section of Belgium, he couldn't expect to still keep his throne after the war finished. Albert stationed non-commissioned officers behind the line, to shoot anyone who tried to retreat.

But after days of German shells (killing or wounding 1/3 of the Belgians), it was almost impossible to hold on. So Albert ordered the sluice gates in the dikes that held back the sea. In some places, this required using dynamite. The Germans were getting more & more men across the Yser, and the flooding confused them. At first, in the morning, the water was ankle-deep, but they just assumed it was from the rain. By midnight, though, the water was knee-deep and still rising. They had to give up the offensive, and spent the rest of the night getting the men back to dry land. Pretty soon, an 8km-wide, shoulder-deep lake was separating the two sides, finishing that part of the fight.

The Germans who had been fighting there were now sent south to Ypres. Here, they were trying to capture the villages on a low ridge that circled Ypres north-east-south. The fighting was often hand-to-hand. Their goal was to break through the French/British line on that ridge, and thus close in on Ypres itself.

One of these villages was Wytschaete. A day after the dikes were opened, a Bavarian unit tried to take that village, but failed. After the attack finished, a captain named Hoffman lay wounded between the Germans and French. Hitler had been fighting under him, and he carried him to safety under enemy fire. Hoffman died later of his wounds, and Hitler gained the Iron Cross Second Class for his actions.

The Germans found that fighting the French & British was as difficult as fighting the Belgians had been. But when the French & British attacked, they were thrown back, too. The battle swung back and forth, neither side gaining a real advantage. As the casualties grew, whole companies were reduced to platoon size, and the remainders of units were mixed together. So many officers were killed that young lieutenants found themselves in charge of what was left of battalions and regiments.

The rain was continuous. Any hole dug was immediately filled with water, so the men had to lie down on the ground. The landscape was flat, but broken up by villages, patches of woodland, rivers & canals, hedgerows and fences. This sort of landscape was far better for defense than offense, and almost impossible for cavalry (who would be useless against artillery anyway).

The British were often outnumbered, but managed to hold off attacks or come back to recapture lost ground. During the Second Boer War, their cavalry had learned to dismount and fight as infantrymen, and this was one of the factors that saved them. But what really saved them was the British skill at musketry.

Many of the German reserve troops were inexperienced. There were thousands of schoolboy recruits, many of them only 16yrs old. They advanced as heavily-massed formations, led by equally inexperienced reserve sergeants and officers. They would advance arm in arm, singing, wearing their fraternity caps and carrying flowers. It was almost impossible for the British riflemen to miss them, and they killed row after row. Sometimes, they managed to drive the British back – but often they didn't know what to do afterwards. So they'd muddle around aimlessly until the enemy counterattacked them.

One evening, the Germans managed to drive the British out of a village called Bixshoote, at terrible cost. Later, they were told that they were to be relieved overnight. Because of their inexperience, they marched away before they were relieved, and of course the British came straight back and retook the village. Over the next fortnight, the Germans would try again and again to retake what they'd given away, but failing and suffering terrible casualties.

British casualties were also terrible. Scotland's 2nd Highland Light Infantry Battalion had started the war with over 1,000 men, but when they were withdrawn, there were only 30 of them left. The BEF was getting close to being annihilated. In some places, their line was stretched so thin that the Germans believed it must only be a decoy, with a huge force behind it, and so left it alone.

On October 30th, both sides launched an attack on the other, running straight into each other, and suffering enormous losses.

On October 31st, the Germans attacked the British, and broke through their defensive ring into the village of Gheluvelt. Now the way was open to Ypres – but these were more inexperienced troops, and they didn't know what to do, so they waited for instructions. In the meantime, a British brigadier general gathered together the only troops in the vicinity (7 officers, and the 357 men remaining of the 2nd Worcester Regiment) and sent them to Gheluvelt. They had to cross about a km of open ground, and 100 of them were cut down as they did so.

When they reached the edge of the village, they hid in a grove of trees, fixed their bayonets, and then attacked. There were 1,200 Germans there, but they thought the small British force was just the advance guard, and they fled.

The BEF had no reserves left, were nearly out of ammo, and were absolutely exhausted. They had nearly completely fallen apart – but Falkenhayn didn't know this. That night, he called for a halt. He still believed they could achieve a breakthrough, but he wanted to get more experienced troops for it.

In early November, things were quiet on both fronts for a while. The first Canadian troops had arrived in England, and were getting ready to cross the English Channel & join the British. An Indian corps (including some Gurkha units) was with the BEF in Flanders. Troops from France's Africa colonies were arriving.

Hindenburg was named Commander-in-Chief of all German forces on the Eastern Front. Ludendorff stayed on as his Chief of Staff, and Hoffmann stayed on as well. The Ottoman Empire decided to join the war on Germany's side.

Less than a week into November, Grand Duke Nicholas sent two armies through Poland into Silesia. Other Russian armies were moving south-westwards, towards the Carpathian Mountains. Falkenhayn was nearly ready to make another attempt at Flanders. The kaiser was still at headquarters, and being a complete nuisance. He was constantly demanding a victory so that he could parade through a conquered city in uniform.

Around this time, Ludendorff made a quick visit to Falkenhayn. With Hoffman's help, he'd worked out a new plan to deal with the Russians. He would allow them to advance westwards, beyond the railheads that were their main source of support, until they ran out of momentum. Then the Germans would attack from the north, taking them in the flank and rear, and cut them off from Warsaw. But they needed reinforcements for this, and he was asking for them.

But Falkenhayn had been gathering as many divisions as possible for Flanders, and he said he couldn't spare any. Ludendorff was furious and left Tensions between Falkenhayn and Ludendorff/Hindenburg were growing: they disagreed on whether their best hope of victory was in the west or the east.

Ludendorff and Hindenburg carried out their plan anyway. They moved the Ninth Army back into East Prussia by train, and combined it with the Eighth. The troops of these two armies stretched over 110km. Then they waited while the Russians advanced westwards.

As they'd expected, the Russians soon ran out of momentum, overextending themselves further than their supply lines could manage. The Germans attacked (they had superior numbers at this point), and after 4 days of fighting, the Russians began to retreat, with the Germans chasing and still attacking them.

In Flanders, Falkenhayn ordered another offensive, this time with more experienced troops and on a narrower front. But it was just another series of inconclusive battles along the ridge. Ypres was being destroyed. The British were using old towers as observation posts, and the Germans shelled them. The fighting was chaotic, with artillery fire raining down from both sides.

The British used and defended everything they could – houses, walls, woods – and the Germans had to attack every such strongpoint. When they broke through the first line of fortifications, they faced a second one immediately behind it. East & south-east of Ypres were many thick hedges, wire fences, and dikes; woods with dense undergrowth made the terrain incredibly difficult. The Germans were often only able to use the roads, which were constantly fired upon by the British using machine-guns. The villages were turned to ruins. The official German account, written by the general staff, later stated, “the enemy fought desperately for every heap of stones and every pile of bricks before abandoning them...the fighting generally developed into isolated individual combats.”

The village of Lombartzyde had been captured by the Germans on October 23rd. It was retaken by the French on the 24th; then by the Germans on the 28th; the British & French on November 4th, the Germans on the 7th. It changed hands twice more before ending up permanently under German control.

Village by village, the Germans gradually moved forward, tightening their grip on the Ypres Salient (the French/British semicircle east of the town). But they constantly failed to break through it. Several times, French or British generals suggested that they should retreat, but Foch refused – he still believed in the cult of the offensive, and before the war he'd written that an army is never defeated until it believes it is.

On November 11th, the Germans launched their most important offensive. The First Guards Regiment (the most elite unit in the German army, and led by Prince Eitel Friedrich) drove the British out of Nonnebosschen – but like at Ghulevelt, they failed to take advantage of the fact that the way to Ypres was open. A motley group of the only soldiers in the area (anyone who could pick up a rifle, including cooks and drivers) counterattacked in what was surely a hopeless move, but the Germans thought they were the advance guard, with the Entente reserves behind it, and fled. This was the last time they came close to breaking through at Ypres.

The Ypres fighting continued on until November 22nd, but it was obvious that it was going nowhere. Even Kitchener was horrified, declaring, “This is not war!” When the snow came, and the mud froze, the whole thing became impossible. The Entente claimed victory because they'd stopped the Germans from breaking through & reaching the Channel ports. The Germans said the same, because they'd captured so many strongpoints around Ypres that the Entente forces no longer hand any adequate bases to launch new offensives from.

The British had suffered 50,000 casualties in Flanders, and over half of the 160,000 men who had come to France were dead or wounded. France lost over 50,000, and Germany at least 100,000.

The Russians continued to retreat eastwards across Poland. They tried to withdraw behind an expanse of lowland marshes, but they were driven out. Then they tried to make a stand at Łódź, but were forced to keep retreating on December 6th. At Łódź, they lost 90,000 men, and the Germans lost 35,000.

About 55km east of Łódź, the onset of winter halted the pursuit and retreat. The Germans had 136,000 Russians prisoners with them. The Germans whom the Russians had taken prisoner were not prepared for the Russian winter. Their overcoats were made of a thin material that was pretty much useless, and many of them didn't even have that. And the Russian POW camps were in Siberia.

The Russians and Germans dug makeshift defences out of the frozen earth. As winter arrived, the Russians had 120 divisions on the eastern front, with 12 battalions in each division. The Germans & Austrians had only 60 divisions, with 8 battalions in each.

Austria had had a rare victory. The Russian Eighth Army (commanded by General Alexei Brusilov) captured a mountain pass in the Carpathian Mountains, one that led into Hungary. But Franz Conrad learned that there was a gap between the Russian Eighth and the army on its right, so on December 3rd, he sent an attack force into it. The Russians were driven back 65km in only 4 days. Reinforcements arrived, and the Austrians were forced to stop on the 10th, but it was an important victory. First, it had stopped the Russians' hopes of crossing the Carpathian Mountains. Second, it had prevented them from sending a force from Krakow towards Germany, which was a new plan. The Russians were stuck from the winter, and they hadn't managed to get far into enemy territory.

Then Austria invaded Serbia for the third time since the war had started. Like the other invasions, it began well – they captured Belgrade and a lot of Serbian territory. The day after Belgrade was taken, King Peter Serbia addressed his troops, rifle in hand. He told them he was releasing them from their pledge to fight for him and their country, but he was going to the front, even if it was alone. This boosted their morale greatly.

General Radomir Putnik organized a counterattack of 200,000 troops. The Austrians were overextended, had gone days without food, and were still wearing their summer uniforms. They fled back over the border. 28,000 Austrians had been killed, 120,000 wounded, and 76,000 taken prisoner. 22,000 Serbians had been killed, 92,000 wounded, and 9,000 taken prisoner or missing; their survivors were wracked with dysentery and cholera.

For the rest of the war, Austria would never again mount a major offensive as anything more than a minor force, a support to Germany but not a partner. Nor would they win a major victory of their own. Nearly 200,000 of their troops in total were dead; nearly 500,000 wounded; about 180,000 taken prisoner.

On the Western Front, fighting continued even after Ypres was given up on, but nothing major. Joffre ordered assaults wherever he thought the Germans might be weak, calling it “nibbling”. France would suffer another 100,000 casualties by March.

The term “world war” was being used. There had been naval battles all around the world since August (although none of them were very important). Various colonial police & small military forces fought each other in Africa, and the indigenous populations became involved. Japan took possession of Germany's territories in the Pacific.

Turkey was the newest member of the Central Powers. They wanted to recoup some of their losses as their empire had fallen apart, and they sent troops from Syria into Persia.

The British in particular were worried about this. Russia suggested that a show of force near Constantinople might frighten the Turks into pulling back from Persia. So a battleship was sent to the mouth of the Dardanelles, and shelled one of the outermost forts guarding it. Within 30min it was totally wrecked. The battleship sailed away, having never been threatened. Churchill was encouraged by the ease of this operation that he began to wonder they might be able to capture the whole passage leading up to Consantinople.

On Christmas morning in Flanders, the German troops began singing carols in their trenches, and displaying pieces of evergreen they'd decorated. The British began to sing as well. Slowly, some of the troops began to leave their trenches. They eventually gathered in no-man's-land, exchanging food and cigarettes, and even playing soccer. In some places, the Christmas Truce lasted for more than one day. The generals were indignant when they learned of it, and they made sure nothing like that happened again.

#book: a world undone#history#military history#ww1#first battle of ypres#siege of antwerp#battle of the vistula river#battle of the yser#battle of łódź (1914)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

BElgium WW1 Military SILVER Medal Battle Yser 1914 1918 Decoration Belgian NAME BUY IT NOW – BElgium WW1 Military SILVER Medal Battle Yser 1914 1918 Decoration Belgian NAME

0 notes

Photo

2 WW1 Medals Belgium Yser Combat & Commemorative Check it out $82.00 https://ebay.to/2ZEtLJs

0 notes

Photo

2 WW1 Medals Belgium Yser Combat & Commemorative Click quickl $90.00 https://ebay.to/2ZEtLJs

0 notes

Photo

2 WW1 Medals Belgium Yser Combat & Commemorative Hurry $90.00 https://ebay.to/2ZEtLJs

0 notes