#Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#OTD in 1803 – Birth of William Smith O’Brien in Dromoland, Newmarket on Fergus, Co Clare.

William Smith O’Brien was a Protestant Irish nationalist Member of Parliament (MP) and leader of the Young Ireland movement. He also encouraged the use of the Irish language. He was convicted of sedition for his part in the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848, but his sentence of death was commuted to deportation to Van Diemen’s Land. In 1854, he was released on the condition of exile from Ireland,…

View On WordPress

#Co. Clare#Dromoland#England#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish History#Newmarket-on-Fergus#Sedition#The Irish Times#Van Diemen&039;s Land#William Smith O&039;Brien#Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Easter Rising

Easter Rising is one of the most well-known Irish rebellions. It caught the British by surprise (despite the Castle knowing all there was to know about the planned uprising) and lasted for five days before being defeated by the British Army. The Rising was concentrated in Dublin, with only a few countryside engagements. While the rebellion itself was a failure, the execution of its leaders and the determination of its survivors, turned it into a spiritual and political victory that set the stage for the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War.

And it nearly didn’t happen.

Daniel O’Connell and the Young Irelanders

To understand why the Rising occurred, one most first familiarize themselves with Ireland’s long struggle against British colonialism.

In 1798, the United Irishmen coordinated a massive rebellion in Ireland that would clear the path for a Napoleonic French invasion. They would help the French overthrow the British Empire and earn their freedom. The rebellion was brutally suppressed by the British forces and served, in the British and Protestant Irish minds as a nightmarish example of what the Catholic Irish were “capable” of.

This rebellion was followed by another rebellion in 1803, led by Robert Emmet. He also coordinated with the French, but was forced to move the date of his rebellion up, jeopardizing any support he has previously organized. He issued a proclamation of the Provisional Government and expected the people to rise. It only lasted for a day before it was defeated by the British. Emmet was executed by the British.

After the failed rebellions, a modicum of progress was achieved in the 1820s/1830s when one of Ireland’s greatest statesmen, Daniel O’Connell campaigned for Catholic Emancipation i.e. the right for Catholics to sit in Parliament. This was granted in 1829.

Daniel O'Connell

O’Connell tried to repeal the Act of Union and asked that Ireland be allowed to govern itself independently while acknowledging the Queen as the Queen of Ireland as well as of England. However, O’Connell’s failing health and his refusal to do anything that would lead to bloodshed weakened his support and the repeal fell apart after he died.

Out of the ashes of O’Connell’s attempt to repeal the Union, rose the Young Ireland Movement. This group led the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848, which was defeated by the British. Many of the organizers were shipped off to prisons all over the British Empire, including Australia. One Young Irelander, Thomas Meagher migrated to America in time to volunteer for the Union Army’s Irish Brigade when the American Civil War broke out,

Another Young Irelander, James Stephens created the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a secret organization that would be responsible for Easter Rising and fill the ranks of the IRA.

Charles Parnell and Home Rule

Although O’Connell failed to repeal the Union, he paved the way for greater independence in Ireland. He proved that the British could be engaged through their own parliamentary government and that more could be achieved through negotiations than through violence. Charles Parnell took these lessons to heart and used his own position within England’s parliament to push for Home Rule.

Parnell was a politically astute Irishmen, associating with well-known nationalist organizations such as the IRB, while also using parliamentary procedures such as obstructionism to drew England’s attention to Irish issues. Parnell was able to capitalize on Irish resentment over land ownership and landlords to increase his party’s power within parliament, leading to his arrest.

While in prison he made a deal with Gladstone’s government, promising to quell violent agitation if Gladstone allowed renters to appeal for fair rent before a court. This, combined with the backlash following the Phoenix Park killings, broke the IRB’s power until the early 1900s. Parnell used his power to reintroduce Home Rule which combined a request for independent rule with agrarian reform. He also won the support of the Catholic Church. He reshaped his party, renamed it the Irish Parliamentary Party, and introduced a new sense of professionalism into its members. Other British parties would base their organization on Parnell’s tightly run party. He also helped passed several Land Acts that abolished the large Anglo-Irish tenant owned estates.

Just when Parnell was at his highest point of power and Home Rule seemed destined to become reality, a personal scandal ruined his political career. It turns out that Parnell was involved in an affair with a currently married woman. The Catholic Church, who had grown to distrust Parnell, used this to break his political power and even Gladstone turned his back on him. Parnell was defiant, splitting his party into the Parnellites and anti-Parnellites. John Redmond, another important Irish statesman, was a Parnellite. Parnell died shortly after, taking Home Rule with him.

John Redmond

After adjusting to the social change demanded by Daniel O’Connell in the 1820s/1830s and the trauma of Parnell’s scandalous fall from grace, Ireland’s future seemed bright. The mystical and ever elusive Home Rule seemed to be within the grasp of John Redmond, Parnell’s political and spiritual successor.

John Redmond

This bill promised a bicameral Irish Parliament to be set up in Dublin, the abolition of Dublin Castle (the center and reviled symbol of hated British colonialism and authority within Ireland), and a distinctive Irish representation in the Parliament of the U.K. This bill passed the House of Commons three times and was defeated in the House of Lords three times and was postponed indefinitely when WWI broke out.

While Home Rule’s fate was up in the air, Ireland itself was undergoing a social transformation. R. F. Foster’s book Vivid Faces does a fantastic job capturing the social experiences of the members of Irish Volunteers and IRA that I cannot recapture in this short post. However, it is sufficient to say that the members that crowded the language revival leagues and sports leagues wanted more than Home Rule. They wanted a revitalized and progressive Gaelic culture and identity.

The Irish, mostly Protestant, in, what is now, Northern Ireland were alarmed by the very idea of Home Rule and this renewed interest in Gaelic culture. They responded by creating the militaristic organization called the Ulster Volunteers in 1912. Their goal was to pressure the British government to nix Home Rule and to defend themselves from the Catholic “onslaught” should Home Rule pass into law.

The Irish nationalists in the rest of the Ireland responded by creating their own military organization: the Irish Volunteers in 1913. It was created by Eoin MacNeill and included members from the Gaelic League, Sinn Fein, and the Irish Republic Brotherhood.

Eoin MacNeill

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) was a secret organization dedicated to Irish independence. Bulmer Hobson (who co-founded the Fianna Eireann with Constance Markievicz) combined the two organizations into the Irish Volunteers.

Redmond knew about the Irish people’s frustration. He promised the English that he would rally the Irish about the British cause and enlist in its armies if England promised to pass Home Rule. During a speech, Redmond-eager to prove that he was a man of his word-passionately encouraged Irish to enlist in the army and fight in France. This was the final straw for many nationalists and Redmond lost what little power he had over events. Redmond would try to regain control by co-opting the Irish Volunteers with assistance from Bulmer Hobson, but this only angered the nationalists. Tom Clarke, who was great friends with Hobson, considered it an act of treason and never spoke to his friend again.

Irish Volunteers and the IRB

The Irish Volunteers were never completely united and the battle for Home Rule drove a split within the organization between those who trusted Redmond and those who decided that Home Rule wasn’t enough anymore and that a bloody uprising was needed. Of the men who wanted to wait, Eoin MacNeill and Bulmer Hobson are the most famous. They believed that it was better to wait for British provocation before leading the people to the slaughter. They were also doubtful of their chances of success and did not believe in the glorious sacrifices that Patrick Pearse exalted in his speeches and writing.

The more militant group kept the name Irish Volunteers, even though many of them were also IRB members, and consisted of men such as Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke, Seán Mac Diarmada, Joseph Plunkett, and Eamonn Ceannt. They believed that England’s difficulties meant Irish opportunity and they wanted to enlist German help in pulling off an uprising. These men were idealistic and, perhaps a bit naïve, but they were dedicated to their cause and to their country.

This committee knew they would not be able to win without arms and support, so, keeping their plans to themselves, they sent Roger Casement and Plunkett to Germany to present their plans for a German invasion that would coincide with an Irish rising. The Germans rejected this plan (maybe remembering what happened in 1798, when the French made a similar landing, weeks after a massive Irish uprising), but promised to send arms. Plunkett returned to Ireland while Casement remained in Germany to recruit Irish prisoners of war to the Volunteer’s cause.

The situation in Ireland, specifically Dublin, became even more complicated when James Connelly, head of the Irish Citizen Army-a group of socialist trade unionists-threatened to start his own uprising.

Bulmer Hobson

A meeting between Connelly and Pearse occurred and Connelly joined the military committee. Thomas MacDonagh joined shortly after, becoming the seventh and last member of the committee.

The Irish Volunteers were often seen drilling and practicing for some vague rebellion, so it wasn’t suspicious to the authorities or to MacNeil and Hobson to see units marching around. When Pearse issued orders for parade practice on Easter Sunday, MacNeil and Hobson took it at face value while those in the know, knew what it really meant. This surreal arrangement would not last for long and the committee’s secrecy nearly destroyed the very rising it was trying to inspire.

Seven Members of the Military Committee

Not only were the members of the committee the men most responsible for the rising, they were also the signatories to the Irish Republic Proclamation. This important document was the foundation for the IRA’s fight for freedom and was the death warrant for all who signed it. Below are short biographies on the seven members.

Patrick Pearse

Patrick Pearse was a school teacher and poet. He was a firm believer in reviving the Gaelic language and founded St. Enda’s College as a bilingual institution, focusing on Irish tradition and culture. Pearse is the man who represents the Rising best as he truly believed that the blood of martyrs would liberate Ireland. He was the spiritual leader of the rising and one of its most powerful martyrs.

Tom Clarke

Tom Clarke was an old hat at rebellions. He was a firm believer in violent uprisings and spent fifteen years in an English prison before joining the committee. He had joined the IRB in 1878 and was arrested for attempting to blow up London Bridge as part of the Fenian dynamite campaign in 1883. He was only released because of public pressure in Ireland and an endorsement from John Redmond, himself. Following his feud with Hobson over Redmond’s acceptance into the Irish Volunteers, Clarke became firm friends with Seán Mac Diarmada. Together they ran the IRB and helped plan Easter Rising.

Seán Mac Diarmada

Seán Mac Diarmada (also known as Sean MacDermott) was born in Corranmore, where he was surrounded by Irish history and reminders of British oppression. By the time he moved to Dublin in 1908, he was already a member of the IRB, Sinn Fein, the Gaelic League, and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. He was also manager of the newspaper Irish Freedom which he founded with Hobson and Denis McCullough. He became close to Clarke and helped run the IRB. He was arrested briefly in 1914 for a speech against joining the British army but was released in 1915. Like Pearse, Mac Diarmada believed in the power of a bloody sacrifice and, besides Clarke, was the man most responsible for planning the rising.

Thomas MacDonagh

Thomas MacDonagh was assistant headmaster at St. Enda’s School and lecturer at University College Dublin. He was also a playwright and poet. He met Pearse and MacNeill through the Gaelic League and joined the IRB in 1915. He married Muriel Gifford whose sister, Grace, would marry Joseph Plunkett. He was also responsible in planning the funeral of Irish Fenian leader Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa where Pearse would give one of his greatest speeches.

Joseph Plunkett

Joseph Plunkett came from a wealthy Dublin family. He contracted tuberculosis when he was young and spent considerable time in the Mediterranean and North Africa. When he returned, he joined the Gaelic League where he befriended MacDonagh. He joined the IRB in 1915 and was sent to German with Casement to negotiate for arms and military support.

Eamonn Ceannt

Eamonn Ceannt was a very religious and committed member of the Irish Volunteers. Like most Volunteers, he joined the Gaelic League when he moved to Dublin and became involved in nationalistic affairs after meeting Pearse and MacNeill. In 1907 he joined Sinn Fein and in 1915 he became a member of the IRB.

James Connolly

James Connolly was born in the Irish slums of Edinburgh and joined the British Army when he was fourteen. While serving in the army, he was involved in the Land Wars, sparking an interest in land issues and a deep hatred of the British. He deserted and became involved in the socialist movement in Scotland. He moved to Dublin when he heard that the Dublin Socialist Club was looking for a secretary and quickly transformed it into the Irish Socialist Republican Party. He, along with Arthur Griffith, protested the Boer War and he wrote a book about labor in Irish history that was very critical of Daniel O’Connell. In 1913, he co-founded the Irish Citizen Army with Jim Larkin, whose aim was to defend workers and strikers from the police. Connolly was initially disgusted with the Irish Volunteers, believing that they were too bourgeoise and didn’t have the guts to rebel against the British. It was only after meeting with Pearse and Clarke did he change his mind and support the Volunteers and the Rising.

Easter Rising Sunday

Easter Rising was a surprise for the British and for the leaders of the Irish Volunteers-Eoin MacNeill and Bulmer Hobson. Historian, Charles Townshend argues that Hobson and MacNeil were subsequently written out of Irish history because of their resistance to any violent rebellion in 1916 and it is only recently that they’ve returned to their proper place in history. While it is true that they were hesitant to lead a general uprising, it was for good reasons. The Irish Volunteers weren’t soldiers, despite all their training, and they didn’t have the weapons needed to fight a protracted rebellion. Additionally, it was doubtful that the general population would support their efforts. These concerns combined, made the Rising’s chances for success minimal.

This didn’t dissuade men like Pearse and Clarke, who planned the Rising right under MacNeill’s noses. To ensure full support of their efforts, the seven leaders of the Rising had the ‘Castle Document’ read during a meeting. This document was a plan to arrest the leaders of the Irish Volunteers should the English implement conscription. While it was a real document, it seems that the leaders may have played fast and loose with when it was going to be implemented. Either way, this was the type of repressive efforts that MacNeil believed were needed to ensure the people would support a rising of any kind. MacNeil gave orders to the men to resist and the seven leaders decided amongst themselves that the Rising would take place on 23rd April 1916. They didn’t tell anyone else though and wouldn’t until the last minute.

Then things began to unravel.

First, Roger Casement was arrested. Roger Casement had gone to Germany to recruit arms and assistance from the German government and to recruit Irishmen from the captured British soldiers. The Germans were less than supportive, and it seems Casement boarded the ship Aud to return to Ireland to either stop or postpone the rising. However, when he arrived in Ireland on either April 21st or 22nd, he was pick up by British police and placed in jail.

Then MacNeil and Hobson had their worst suspicions confirmed-Pearse and his comrades were secretly planning a rebellion without their support. There was a confrontation between MacNeil and Pearse on the 21st and MacNeil vowed to do everything possible-save warning the authorities-to stop the rebellion. However, the next day MacNeil was informed that the Germans had sent a boat full of supplies to Ireland. This seemed to convince him that things were firmly out of his control and he remained mostly mute about his feelings regarding the Rising. His opinions changed again when found out that Casement had been arrested and the arms had been picked up by the British. Feeling that this ruined what little chance the rebellion had to succeed, he spoke to Pearse once more. One can only imagine his disorientation when he found out that Hobson had been arrested by the IRB Leinster Executive out of fear that he would try to stop the rebellion. Why Pearse and his comrades never arrested MacNeil is unknown, but it speaks volumes about which man they were more threatened by.

Failing to convince Pearse that it was necessary to cancel the rebellion to avoid disaster, MacNeil wrote a counter-order, canceling the drills scheduled for Sunday. This counter-order took an already confused situation and turned it into a bewildering disaster. Units formed as ordered by Pearse and dispersed with great puzzlement and some anger and frustration. Pearse and his comrades met to discuss their next steps and decided the die had been cast. There was no other choice except to try again tomorrow, Monday, 24th, April 1916.

As can be imagined, the counter-orders have been a source of much anguish and gnashing of teeth. From the rebellion’s perceptive, it did more to ruin the Rising then the British. There is some belief that if the rebellion had occurred on Sunday as planned, with all the Irish Volunteers mobilizing, then it may have been successful. Some of this is definitely wishful thinking, as the plan for the rebellion was far from perfect to begin with. Have a larger showing of Irish Volunteers may have only meant more Irish dead at the end of the five days.

The more important question how did the decision by Pearse and his comrades to form a shadow chain of command within the Irish Volunteers affect operations? MacNeil would not have needed to issue the counter-orders if he had been in on the planning to begin with and there would have been no confusion on part of the Volunteers if commands were issued as they should have been. While it is true that Hobson and MacNeil did not want to rebel until conditions were more favorable for the Volunteers, the Rising leader’s decision to split their command in half was far more detrimental to their rebellion than anything else.

Easter Rising Monday

When the Rising began that Monday, only about half of the Irish Volunteers showed up in several key locations in Dublin and even fewer gathered in the countryside. Pearse and the others lead about 150 men down Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) where they picked up stranglers and marched on the General Post Office (GPO). It was here they would establish their headquarters.

The General Post Office

The GPO was a formidable building and important location in Dublin, but there is some question as to whether it offered Pearse and Connolly the ability to effectively communicate with the other garrisons, especially when it was cut off from the southern half by the Castle and Trinity College.

Whatever its military significance, it became a politically powerful building. After they took the GPO, two Irish flags were hung-one was yellow, green, and orange/yellow and the other was green with a golden harp. Then Pearse read outloud the Irish Proclamation of the Republic to the newly ‘liberated’ people. This proclamation was signed by all seven leaders of the Rising-Pearse, Clarke, Ceannt, Mac Diarmada, MacDonagh, Connolly, and Plunkett-and it would later serve as their death warrant.

Whether because he read the proclamation or simply during the stress of the times, Pearse became the unofficial president and general of the Volunteers-although there were claims following the Rising that Clarke was the actual president. Additionally, the name Irish Republican Army (IRA) came out of this makeshift government. They wanted an official name for their army. It originally started as the Army of the Republic, which was changed to the IRA and became official and everlasting in the 1920s.

There was a sense of futility combined with military spirit in the GPO. While men like Pearse had always spoke of the need to wash Ireland in martyr’s blood, even practical men like Connolly seemed to believe that they were going to be slaughter. Yet, Pearse and the other leaders still struggled to develop a military command structure and government while also taking the city. As Pearse became the center of the Rising, Connolly took command of the military forces, sending out orders that his secretary, Winifred Carney, wrote on her typewriter.

While this was happening, the battalions that showed up, quickly dispersed to vital positions throughout the city.

To the east of the GPO, was the Four Courts-the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the High Court, and the Dublin District Court. This was taken by the 1st battalion commanded by Edward Daly.

Edward Daly

Daly was the youngest man to serve as commandant and was Tom Clarke’s brother-in-law. Daly sent a small company under the command of Sean Heuston to take the Mendicity Institution (one of Ireland’s oldest charities). Heuston’s original orders (when GPO expected an immediate response from the British Army) were to hold the position for a few hours to give GPO time to get organized. Heuston would hold on for three days.

Southeast of the Four Courts was the South Dublin Union. This was taken by the Fourth battalion led by Eamon Ceannt, one of the seven signers of the proclamation and planners of the rising.

West of the South Dublin Union was Jacob’s biscuit factory. This was taken by the second battalion commanded by Thomas MacDonaugh, another signer of the proclamation.

West of the biscuit factory was St. Stephen’s Green, a large park. This was taken by Connolly’s Citizen Army commanded by Michael Mallin.

Michael Mallin

Mallin was Connolly’s second in command co-founder of the Socialist Party of Ireland. Constance Markievicz, a fascinating and colorful member of the Volunteers, Citizen Army, and, later, IRA, was his third in command. They tried to take Shelbourne Hotel on the north-east side of the park, but didn’t have the sufficient manpower. The British would position troops in the hotel by Monday night.

Northeast of St. Stephen’s Green was Boland’s Mill. This was taken by the Third battalion, commanded by Eamon de Valera. De Valera was a mathematics professor and had joined the Irish Volunteers out of a sense of nationalism, but only reluctantly became an IRB member. He would later distance himself from the IRB, professing a disdain for secret societies.

While the rebels certainly took a large part of the city, Dublin was surrounded by five police barracks. To the northeast there were the Royal and Marlborough barracks, to the southwest there was the Richard Barracks, to the very south was the Portobello barracks, and to the southeast was the Beggars Bush Barracks.

Additionally, the Castle, the center of British colonialism in Ireland was in the very center of Dublin, and the Volunteers didn’t take it. There was a futile attempt early Monday afternoon, but for reasons that are still unclear, it wasn’t successfully. The Volunteers also failed to take Trinity College and the telephone exchange in Crown alley, allowing the government to control communication and repair the lines that had been cut. Additionally, they failed to take Dublin’s two railways or Dublin Port and Kingstown. This would, later, enable the British to bring in army reinforcements.

There has been a lot of puzzlement over these failures, but it may have simply between due to the lack of manpower and the confusion caused by the counter-orders. There were mild gunfights throughout the day and the Volunteers waited nervously for Britain’s response. They expected it to be hard and fast, but this was furthest from the truth.

That Monday morning there were a total of 400 British soldiers on hand to respond to the rebellion. Historian Charles Townshend claims that there were 100 for each of the four barracks (Richmond, Marlborough, Royal, and Portobello). Despite knowing about the preparation for the Rising and the arms the Germans had sent, the British officials didn’t expect anything to happen that day.

The small force that engaged the rebels during Monday afternoon, were unable to displace the Volunteers. This was a short-lived victory for the rebels however, as by Monday night General Lowe had taken command along with an additional 150 troops from Belfast, and a colonel brought up the artillery from Athlone. He could expect more reinforcements from England the next day. Lowe’s plan was to establish communication along the Kingsbridge-North Wall-Trinity College line, cutting the city in half, and isolating the rebel forces from each other.

Martial law was declared, leaving Dublin’s fate in the military’s hands.

Tuesday, 25 April

By Tuesday morning, historian Charles Townshend estimates that the British military strength was up to 3000 men and Lowe estimated the rebels to be about 2000 strong, but he knew little else. He feared that the rebellion could spread to the countryside and so he requested additional reinforcements.

Despite not knowing the exact situation, Lowe’s men were able to achieve a few victories. By the end of Tuesday, they had dislodged Mallin’s men from St. Stephen’s Green and into the Royal College of Surgeons. A unit attempted to repair a section of the damaged railroad at Amiens Street but were attacked by the rebels positioned along Annesley Bridge. They fought for two hours before the British were forced to retreat.

That night, the British were able to position the four 18 pounder field guns and the guns on the HMS Helga. The British would use the artillery to great effect on Wednesday, focusing their fire on Liberty Hall, O’Connell Street, and Boland’s Mill. Connolly had once said that Britain would never fire artillery at Dublin because it was a modernized capitalistic city. One wonders what Connolly’s thoughts were during the intense bombardment.

Francis Sheehy-Skeffington

Tuesday was a day of small engagements while General Lowe assessed the situation, but that didn’t mean it wasn’t a day of tragedy. The shock of the rebellion shattered the complacency that had taken over the Irish government. With a crisis on their hands, the military responded swiftly and harshly. An example of the kind of repression the military would use during the rest of was week was the arrest of a pacifist, feminist (he had adopted his wife’s name) and prominent Irish social figure-Francis Sheehy-Skeffington.

Francis Sheehy-Skeffington

Sheehy-Skeffington was vehemently against the militarism that had taken over the Irish Volunteers and was out Tuesday trying to discourage looters. He was arrested by British Lieutenant Morris and taken to Portobello Barracks. Later that night Captain J.C. Bowen Colthurst wanted to go lead a raiding party up to Harcourt Rd. (south of St. Stephen’s Green) and he took Sheehy-Skeffington as a ‘hostage’. On the way there, he killed a young man named Coade before ransacking a house owned by the alderman Tom Kelly. He arrested two men, Thomas Dickson and Patrick McIntyre, and took them back to the barracks. He reviewed the papers he found at the alderman’s house and the papers on Sheehy-Skeffington. Wednesday morning, he took the three men out to the yard and shot them, claiming they were dangerous men and he shot them to prevent the men from escaping.

The commander of Portobello Barracks, Francis Vane, was not there during the shooting. When he found out, he demanded Colthurst’s arrest. Instead, the bodies were buried in the yard, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington was not told about her husband’s death, and Colthurst broke into her house to find evidence that Francis Sheehy-Skeffington had helped planned the revolution. Hanna eventually found out what happened to her husband. Vane pressed to prosecute Colthurst and Vane lost his command while Colthurst kept his rank.

Colthurst was finally arrested May 9th and would later be court-martialed and convicted of insanity. He was sentenced to Broadmoor Hospital, but was released in 1918 and resettled in Canada. Vane was dishonorably discharged from the army and went on to become involved with the Boy Scouts.

Wednesday, 26 April

During Wednesday, the British tightened their grip on the city. Using their artillery to bombard positions such as O’Connell Street and Boland’s Mill, Lowe sent his new reinforcements from England into the city to further cut the rebels off from each other.

One unit was sent to attack Heuston’s position at Mendicity Institute. With only 26 Volunteers against hundreds of British soldiers, Heuston held until the British were so close, they could throw grenades into the building. His troops were the first rebels to surrender.

The Sherwood Foresters, a unit that had arrived from Britain, were sent down Grand Canal Street, near Beggar’s Bush Barracks. They were held up where Grand Canal meets Mount Street by heavy rebel fire. The Volunteers had fortified various positions along the street, meaning that the Foresters were caught in their cross-fire as they repeatedly tried to take this position. After five hours of fighting and losing 240 men wounded and killed, they defeated the rebels and took the position, but many historians have wondered why they didn’t try another path into Dublin.

Thursday 27th, and Friday 28th April

Thursday and Friday were some of the bloodiest days during the Rising. One of the greatest battles in the countryside, the Battle of Ashbourne, in which the Fingal Battalion defeated a RIC detachment took place on Friday. Within Dublin, the famous battle for the South Dublin Union occurred on Thursday and the battle for the Four Courts waged during Thursday and Friday. Friday also saw the arrival of Commander-in-chief General Sir John Maxwell, who, perhaps, did more to ensure the spiritual and political success of the Rising than anyone else.

South Dublin Union

Cathal Brugha

Eamon Ceannt and his Vice-Commandant Cathal Brugha led the men at South Dublin Union. After a furious fight on Monday, their front had been mysteriously silent. On Thursday morning, reinforcements from Kingstown port arrived and attacked. The fighting here was vicious and Brugha, who insisted on fighting in the front line, was wounded twenty-five times and had to be sent to the medical staff on Friday. Still, they held throughout the week and even thought they had destroyed the entire British force that had attacked them.

Four Courts

The most famous fight of the Rising occurred in the Four Courts. This position was vital for the rebels as it protected headquarters and was near the center of town. The Volunteers were commanded by Edward Daly. On Wednesday, he sent troops out to take Linenhall Barracks, but didn’t have the men, so they set it on fire. The fire raged for most of the night. Meanwhile the British had taken Capel street, which meant Daly was now cut off from the GPO.

The British attacked Thursday morning. Men in armed trucks rolled down Bolton street and attempted to throw a cordon on King Street. However, the rebels had heavily fortified King street, and every inch was fiercely fought over. Eventually, the British had to drill through the inside walls and travel from house to house, wounding and killing many civilians. Daly had to pull his men back to the Four Court proper on Friday night. They were exhausted, but had fought long and hard.

General John Maxwell

General John Maxwell arrive in Ireland from London on Friday. His arrival signaled that London was no longer going to be nice and understanding with their “difficult Irish citizens”. He was a traditional army man, had served in Sudan, the Boer War, and the First World War. He was to be the formal commander-in-chief for Ireland, eclipsing the civil government that had been put in place, and he, more than anyway, helped create the rebel’s legacies. His first major contribution was to refuse any negotiations short of unconditional surrender. This was to have an important effect on the now tired, starving, and rattled rebels.

The artillery barrage had kept up since Wednesday and, despite their leader’s optimism, many commanders were beginning to doubt if they could last much longer. Then the fires started. It seemed that a shell had started a fire on Sackville Street, setting it ablaze. It spread around the GPO until the men inside could feel the heat through the walls. Then an oil works on Abbey Street caught fire. Friday morning, the women were sent out of the GPO. The building was hit by shells and it caught fire around 3 pm. Things were growing desperate. Connolly, who had spent all week checking posts and men, had been wounded in his left arm and leg on Thursday and had to be carried out on a stretcher. Fire had reached the GPO roof and many of the Volunteers had been cut off from HQ, left to defend themselves in their ever-shrinking fortified positions. An Irish Volunteer, O’Rahilly, who had passed out MacNeill’s counter-order, led a bayonet charge against the British troops and was mortally wounded.

Pearse decided to surrender.

Easter Rising Executions

The order was sent to all the units in Dublin and the few who had risen in the countryside, like the Fingal, Wexford, and Galway Battalions. Most of the troops did as they were told, and they were put in temporary holding cells until the British government could figure out what to do with them.

The British government’s goal was to squash all rebellion within Ireland, thus Maxwell ordered that all Sinn Feiners be arrested. Given the number of people arrested and the severity of the crisis, it was decided that the rebels would be tried by military court. It was decided that the men would be executed, but they could not handle the disgrace of executing the women.

The first three leaders to be executed were Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke, and Thomas MacDonaugh. They were taken out of Richmond Barracks to Kilmainham gaol and shot on May 3rd.

Edward Daly, Willie Pearse (Patricks’ younger brother), Joseph Plunkett (who was allowed to marry his fiancée the night before), and Michael O’Hanrahan were executed on the 4th.

John MacBride was executed on the 5th.

Eamon Ceannt, Sean Heuston, Con Colbert, and Michael Mallin were executed on the 8th and Thomas Kent on the 9th.

Sean MacDermott and James Connolly were executed on the 13th. Connolly, still recovering from his wounds, was tied to a chair so the soldiers could shoot him.

The government in London had become alarmed with the executions by the 4th, but allowed them to carry on until it became clear that public opinion was decidedly against them. John Redmond pleaded for clemency and the Irish public, who had been detached from the rebels at best, were beginning to praise them. It seems that the fact the Rising lasted for so long combined with the civilians who had been murdered (like Sheehy-Skeffington) and swiftness of the executions turned the public against the British forces and towards the rebels.

Given this startling development, the British government decided to intern the remaining rebbels at various prisons and internment camps in England and Wales such as Frongoch, the “University of Revolution’.

The last Irish Volunteer to be executed was Roger Casement. He was tried for treason and was hanged on August 3rd.

Legacy

“That the authorities allowed a body of lawless and riotous men to be drilled and armed and to provide themselves with an arsenal of weapons and explosives was one of the most amazing things that could happen in any civilized country outside of Mexico.”-William Martin Murphy, statement to Royal Commission 1916

It is true that the Irish Volunteers lasted longer than anyone expected (maybe even longer then their own leaders expected), yet that alone cannot count as a victory. Despite their best efforts, the plans for the Rising were muddled and the secret nature of their work only hurt their cause. It tore their movement in two, creating a political vacuum that allowed the IRB to take control, but also created a legacy of distrust. There would always be those members who suspected the IRB and this suspicion that would continue into the Irish War of Independence and contribute to the Irish Civil War and the aftermath of the 1924 Army Mutiny.

Once the Rising started, the battalions quickly became isolated commands of their own, their connection to the GPO and the leadership fragile. There were several brave stands during the Rising, such as Heuston’s stand at the Medicity Institute, Ceannt’s stand at the Four Courts, and the Battle of Ashbourne in the countryside and no one can deny the courage or dedication of the men who rebelled.

However, it is also hard to deny the tragedy of the entire affair. It has been estimated that a total of 485 people had been killed and 2,600 had been wounded during the rebellion. Ireland lost many important men and women such as Francis Sheehy-keffington, Michael Joseph O’Rahilly (the O’Rahilly) and promising leaders such as Sean Heuston and Edward Daly. Dublin city had been bombarded, burnt, and filled with lead and the Rising pushed the English to establish a military governor, John Maxwell.

So, it was a disaster?

It may have been nothing more than another failed uprising had it not been for the brutal murder of men like Sheehy-Skeffington and the executions. One cannot completely fault John Maxwell. Governments and military men often fall into the trap of believing that a rebellion cannot survive without its leadership. The British never expected the survivors to pick up the torch light by the signers of the Irish Proclamation.

De Valera was scheduled to be executed, but was spared because of the change in public opinion. Michael Collins had originally been marked for harsher punishment (such as execution) but was saved because he thought he heard someone call his name and moved to the group marked for lighter punishment in an attempt to identify the voice. Once he joined that group, he just stayed there. These two men would be instrumental in shaping the Irish War of Independence and modern Ireland.

Additionally, men and women like Cathal Brugha, Richard Mulcahy, W. T. Cosgrave, Arthur Griffith, Constance Markievicz, Harry Boland, and many more all participated in Easter Rising, many were interned in prisons like Frongloch internment camp, and would later become vital to the IRA in one capacity or another.

Easter Rising provided these future leaders of Ireland a glimpse into what worked and what didn’t. Michael Collins, himself, was disgusted with the loss of life and Richard Mulcahy, the IRA’s future chief of staff, experienced guerrilla warfare for the first time during the Battle of Ashbourne. De Valera’s experience in Dartmoor prison gave him the reputation and confidence he needed to become President of the Dail. It also created a moment of everlasting brotherhood that created the esprit de corps needed to survive the Irish War of Independence War and the very same brotherhood that would tear Ireland apart during the civil war.

The legacy of Easter Rising will always be tangled with the legacy of the Irish War of Independence and the Civil War. Was it any different from other Irish rebellions? In some ways, yes, in some ways, no. Was Pearse right? Did Ireland need a bloody sacrifice to be free? It is hard to agree with Pearse when Ireland had made many such bloody sacrifices during its long history and would make many more from 1919 up to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. Can the full impact of Easter Rising be understood outside the context of the First World War and the technological advance that had been made in everyday life and in military affairs? Probably not.

The hardest part about assessing the Rising’s legacy is because of its larger than life narrative. The Rising was immortalized shortly after it was over by poets such as Yeats and, since many members of the IRA fought in the Rising, they added to this immortalization as they won independence and struggled to create a state. There was some reassessment in the 60s and 70s, but, as the 100 year anniversary revealed, Ireland still struggles to properly categorize and understand the Rising.

Despite the changing narrative surrounding the Rising, there is one thing that cannot be denied. The sacrifice of the men and women who fought will continue to challenge and inspire us as we worked to undo the damage caused by colonialism and small nations continue to fight to be free.

If you like this post, join my Patreon

References:

Foster, R. F. Modern Ireland 1600–1972

Townshend, Charles. Easter Rising: the Irish Rebellion

Townshend, Charles. the Republic

Foster R.F. Vivid Faces

Coogan, Tim Pat. Michael Collins: the Man Who Made Ireland

Coogan, Tim Pat. Eamon de Valera: the Man Who was Ireland

Fanning, Ronan. Eamon de Valera: a Will to Power

Valiulis, Maryann Gialanella. Portrait of a Revolutionary: General Richard Mulcahy and the Irish Free State

Images-Wikicommons

Bulmer Hobson-https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bulmer_Hobson.jpg

Eoin MacNeill: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eoin_MacNeill.jpg

GPO Easter Rising 1916-By RossGannon1995 [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, from Wikimedia Commons

Edward Daly-Public Domain

Michael Mallin-By National Library of Ireland on The Commons [No restrictions, Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Francis Shehy Skeffington: By photographer not identified [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Cathal Brugha: See page for author [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The O’Rahilly: By National Library of Ireland on The Commons (The O’Rahilly) [No restrictions, Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

#easter rising#irish history#patrick pearse#tom clarke#sean mac diarmada#thomas macdonagh#eamonn ceannt#cathal brugha#eamon devalera#daniel o'connell#charles parnell#world war I#john redmond

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in Wikipedia: Thursday, 3rd August

Welcome, नमस्ते, שלום, こんにちは 🤗 What does @Wikipedia say about 3rd August through the years 🏛️📜🗓️?

3rd August 2022 🗓️ : Death - Jackie Walorski Jackie Walorski, American politician (b. 1963) "Jacqueline Renae Walorski (, August 17, 1963 – August 3, 2022) was an American politician who served as the U.S. representative for Indiana's 2nd congressional district from 2013 until her death in 2022. She was a member of the Republican Party. Walorski served in the Indiana House of..."

Image by Franmarie Metzler, House Creative Services

3rd August 2018 🗓️ : Event - August 3 Two burka-clad men kill 29 people and injure more than 80 in a suicide attack on a Shia mosque in eastern Afghanistan. "August 3 is the 215th day of the year (216th in leap years) in the Gregorian calendar; 150 days remain until the end of the year. ..."

3rd August 2013 🗓️ : Death - Jack Hightower Jack English Hightower, American lawyer and politician (b. 1926) "Jack English Hightower (September 6, 1926 – August 3, 2013) was a former Democratic U.S. representative from Texas's 13th congressional district...."

Image by US Government Printing Office

3rd August 1973 🗓️ : Birth - Michael Ealy Michael Ealy, American actor "Michael Brown (born August 3, 1973), professionally known as Michael Ealy, is an American actor. He is known for his roles in Barbershop (2002), 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003), Takers (2010), Think Like a Man (2012), About Last Night (2014), Think Like a Man Too (2014), The Perfect Guy (2015), and The..."

Image licensed under CC BY 3.0? by Adweek

3rd August 1923 🗓️ : Birth - Pope Shenouda III of Alexandria Pope Shenouda III of Alexandria (d. 2012) "Pope Shenouda III (Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [ʃeˈnuːdæ]; Coptic: Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ Ⲁⲃⲃⲁ Ϣⲉⲛⲟⲩϯ ⲅ̅ Papa Abba Šenoude pimah šoumt; Arabic: بابا الإسكندرية شنودة الثالث Bābā al-Iskandarīyah Shinūdah al-Thālith; 3 August 1923 – 17 March 2012) was the 117th Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the See of St...."

Image by Chuck Kennedy

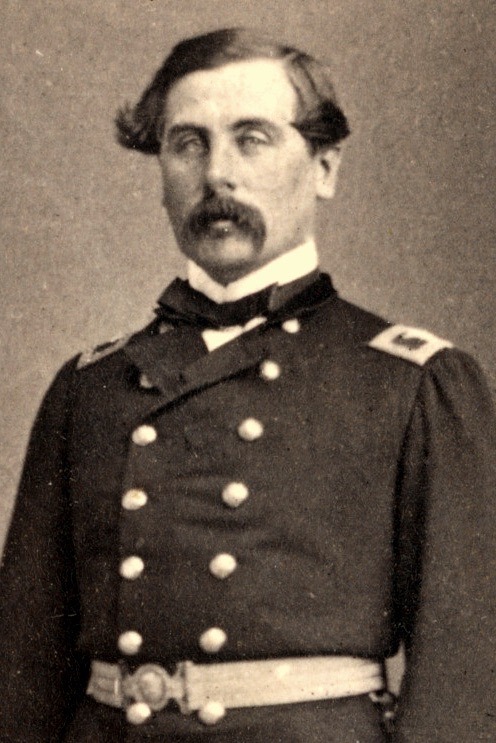

3rd August 1823 🗓️ : Birth - Thomas Francis Meagher Thomas Francis Meagher, Irish-American revolutionary and military leader, territorial governor of Montana (d. 1867) "Thomas Francis Meagher ( MARR; 3 August 1823 – 1 July 1867) was an Irish nationalist and leader of the Young Irelanders in the Rebellion of 1848. After being convicted of sedition, he was first sentenced to death, but received transportation for life to Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) in..."

Image by Mathew B. Brady, circa 1823- 15 Jan 1896

3rd August 🗓️ : Holiday - Christian feast day: Stephen (Discovery of the relic) "Stephen (Greek: Στέφανος Stéphanos, meaning "wreath or crown" and by extension "reward, honor, renown, fame", often given as a title rather than as a name; c. 5 – c. 34 CE) is traditionally venerated as the protomartyr or first martyr of Christianity. According to the Acts of the Apostles, he was a..."

Image by Carlo Crivelli

0 notes

Text

“Marryat and the Age in Which He Lived”

Tonight finds me reading Louis J. Parascandola’s Marryat book, Puzzled Which to Choose. The first chapter is called “Marryat and the Age in Which He Lived” and is a kind of primer to the disruption and hardship of 1830s-1840s England, Marryat’s heyday. I’ve been thinking about that a lot, since as much as Frederick Marryat built his brand with Napoleonic wars books (and directly experienced that world under Captain Lord Cochrane and others), he was selling a nostalgic vision of an earlier, more heroic time.

Here’s a long quote from Parascandola:

All ages are, in a sense, ages of transition. However, perhaps no people ever felt they were in a transitional period more than those in the nineteenth century. And never did the transition seem to be so radical, threatening to change the established order of Christian orthodoxy, rule by nobility, and the fixed hierarchical social structure. These changes could no longer be ignored by the time William IV became King in 1830. “A boy born in 1810... [says G.M. Young] entered manhood with the ground rocking under his feet as it had rocked in 1789... At home, forty years of Tory domination were ending in panic and dismay; Ireland, unappeased by Catholic Emancipation, was smouldering with rebellion; from Kent to Dorset the skies were alight with burning ricks.” One indication of the political instability of the years shortly preceding Victoria’s reign is the frequent change in government; between April 1827 and April 1835 there were six different Prime Ministers, one of them, Viscount Melbourne, twice. On the Continent, there were many disturbances, chiefly the July Revolution in Paris deposing Charles X in 1830, which triggered riots in British cities like Bristol. For these reasons, the years from about 1830 to 1848 have sometimes been labeled the Time of Troubles.

However, it has also been called the Age of Reform because of a plethora of major political reforms, including the Factory Act, the Emancipation Act, the New Poor Laws, the Municipal Corporations Act, the Municipal Reform Act, the repeal of the Corn Laws, and, most significantly, the Reform Bill of 1832. Perhaps the two terms, a Time of Troubles and an Age of Reform, considered together, sum up the period. There were political liberals such as John Stuart Mill and Evangelicals like William Wilberforce who were genuinely interested in reforms, and the age saw the development of the Chartist Movement and the growth of socialism. Nevertheless, the majority of people felt that they were in a position of trying desperately to cling to past values while accepting, often reluctantly, inevitable change [...] Perhaps the Reform Bill of 1832, prompted largely by the fear of insurrection in England, may serve here as an example of the ambivalence towards reform characteristic of the age and of Marryat.

— Louis J. Parascandola, Puzzled Which to Choose: Conflicting Socio-Political Views in the Works of Captain Frederick Marryat

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#1830s#1840s#history#louis j. parascandola#reading marryat#the quote about the boy born 1810!#the neglected post-napoleonic generation of early victorians

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

@rollerz

Ok so everyone knows about the potato famine and how it led a bunch of Irish folks to immigrate to the U.S. and Canada (& Australia but they’re irrelevant to this story) and a lot of them and their descendants fought in the Civil War (on both sides), but not everyone knows that they got a little silly after the war. Picture this: a bunch of dudes angry that their ancestral homeland is occupied by English people, and these dudes are fresh out of a war that provided them with 1) military experience and 2) guns! (and other equipment. but mostly the weapons).

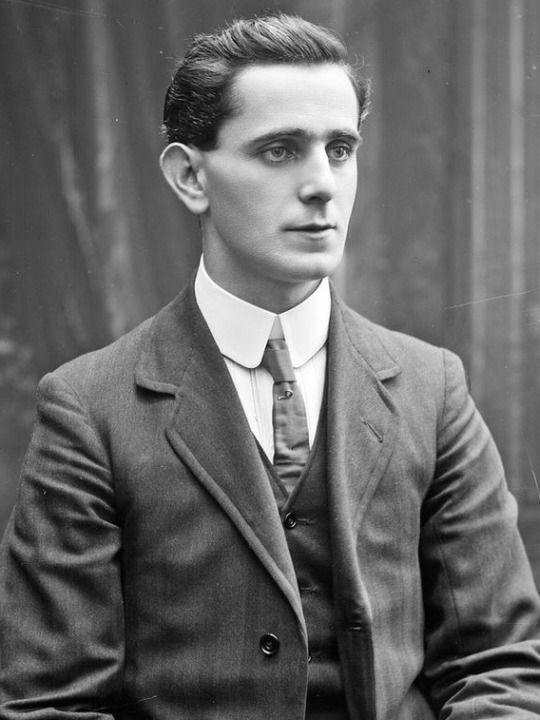

In 1858, the Fenian Brotherhood had been organized by one John Francis O’Mahony, who, besides bearing the distinction of Most Irish Name Ever, would go on to achieve the rank of colonel in the 69th Regiment (nice) of New York State Militia. Also, he looked like this:

The name Fenian traces back to the Fianna, which is pretty badass.

O’Mahony had taken part in the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848, which was when a bunch of 19th-century Irish Gen Zers decided to attack the cops, but failed because the cops, by virtue of being aligned with Britain, had more manpower, more weaponry, and also probably weren’t Literally Starving due to crop failures. Due to the aforementioned starvation and also having been kicked out of Britain for being too Irish, O’Mahony moved to the United States in 1854.

Up to this point, every statement has probably made you think, “Cheers, I’ll drink to that.” I mean, who among us doesn’t want to free Ireland from the grip of tyranny? But brace yourself.

It’s April 1866. The United States has been re-unified for a year.

The Fenian Brotherhood is invading Canada.

Why? you may ask. How? is also a valid question, and easier to answer: with all that military experience acquired during the Civil War, and also the guns. I don’t know exactly which guns, but probably something cool like Spencer repeating rifles or Springfield rifles. Whatever they were, they gave the Fenians the confidence they needed to look at our great big, cold neighbor to the North and think: “Yeah, I could fuck with that.”

If you aren’t aware, you don’t fuck with Canada. You can’t fuck with Canada. Americans have tried. In 1775, General Richard Montgomery -- who was also, coincidentally, Irish -- died in Québec and all he got for it is a cool painting where he looks like Jesus. In 1812, Brig. Gen. William Hull and his severely under-equipped army tried to convince Canadians to leave Britain; RIP to William Hull but the Canadians said no thank you, and chased him out of their country. There’ve been a few other skirmishes here and there, but suffice it to say that Canada is truly the Russia of North America.

The Fenians were different, though, in that they had no government backing and therefore were even more poorly equipped to invade Canada than those other guys.

As for why: they wanted to hold Canada hostage and then hold a sort of prisoner transfer, except for political entities instead of human beings -- Canada for Ireland.

Their first target: Campobello Island. Why choose this target? I suspect it’s because they wanted to start with something small to boost confidence. If you try to bite off more than you can chew right off the bat and fail immediately, it really kills the groove, y’know? Campobello Island’s biggest claim to fame, besides that it was once invaded by Irish-Americans, is that future president Franklin Delano Roosevelt may have gotten polio there in 1921. Which means that in 1866, before the raid, it had absolutely no claim to fame.

So, anyway, about 700 Fenians set off for Campobello Island and failed immediately. They never even landed on the island because British warships showed up and they dispersed.

A couple months later, in June 1866, they tried again, but bigger this time. Led by Colonel John O’Neill (played by Richard Dean Anderson in the television adaptation), about 1000 Fenians crossed the Niagara River into Canada West (now Ontario). The USS Michigan was deployed and cut off O’Neill and his men from supplies and reinforcements. From now on, they were on their own.

And they actually did kind of a good job, for a relatively small force of men with no legitimate backing invading a foreign nation. O’Neill’s army occupied Fort Erie and then managed to ambush some (admittedly inexperienced) Canadian volunteers of the militia and the Queen’s Own Rifles of Toronto. Both forces were about the same size, but as the Torontonians (is that right? Chrome wants to change it to Estonians) were total noobs and the Fenians were veterans of the bloodiest war in United States history, the Fenians...actually won. The Battle of Ridgeway has its own Wikipedia article, and according to it it’s “the only armed victory for the cause of Irish independence between the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and the Irish War of Independence in 1919,” which kind of sucks, considering it was fought by a rag-tag bunch of idiots.

The Fenians went back to Fort Erie and some more fighting occurred, but none of that’s as interesting as the fact that a Canadian officer, Lt. Col. John Dennis -- yes, all three people I’ve introduced so far have been named John -- apparently deserted his men, fled to a house, stripped off his uniform, and shaved his “luxurious sideburn whiskers,” which is just the sort of bonkers shit you love to see in an account of a military action. Also, 2nd Lieutenant Angus MacDonald, boy detective, was there.

It’s fitting that Fort Erie was then known as Waterloo, because that’s where it all fell apart for our heroes. The British were coming, and Colonel O’Neill was, I’m sure, no quitter, but he was one to bravely run away to fight another day. The Fenians retreated back to New York State and surrendered to the U.S. Navy.

The U.S. government began to crack down on wayward Irish rebels, and President Johnson went so far as to issue a proclamation, for all the good it would do. Because of these crackdowns and the ensuing arrests of many Fenian leaders, the planned raids into Canada East (now Québec) were thwarted.

In 1870 and ‘71, the Fenians returned to their old mischief and began raiding Québec and Manitoba, but they just didn’t have the same magic as the first raids. This time ‘round, the Fenian Brotherhood had been infiltrated by British and Canadian spies, which made it near-impossible to execute any plans. Our old friend John O’Neill was arrested by a U.S. Marshal in 1870 after the Battle of Trout River (which involved the 69th [nice] Regiment of Foot [not so nice]), but he and other Fenians were pardoned by President Grant.

And so ends this tale, lost to time. Oh, but also, Kate Beaton did a comic on it.

#mine#us history#canadian history too........but i don't have a tag for that#apparently they /do/ learn about this in canada but for SOME REASON they don't teach it in the states#long post#can u tell i got tired in the middle of it aksksddf

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 8.14

29 BC – Octavian holds the second of three consecutive triumphs in Rome to celebrate the victory over the Dalmatian tribes. 1040 – King Duncan I is killed in battle against his first cousin and rival Macbeth. The latter succeeds him as King of Scotland. 1183 – Taira no Munemori and the Taira clan take the young Emperor Antoku and the three sacred treasures and flee to western Japan to escape pursuit by the Minamoto clan. 1264 – After tricking the Venetian galley fleet into sailing east to the Levant, the Genoese capture an entire Venetian trade convoy at the Battle of Saseno. 1352 – War of the Breton Succession: Anglo-Bretons defeat the French in the Battle of Mauron. 1370 – Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, grants city privileges to Karlovy Vary. 1385 – Portuguese Crisis of 1383–85: Battle of Aljubarrota: Portuguese forces commanded by John I of Portugal defeat the Castilian army of John I of Castile. 1592 – The first sighting of the Falkland Islands by John Davis. 1598 – Nine Years' War: Battle of the Yellow Ford: Irish forces under Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, defeat an English expeditionary force under Henry Bagenal. 1720 – The Spanish military Villasur expedition is defeated by Pawnee and Otoe warriors near present-day Columbus, Nebraska. 1790 – The Treaty of Wereloe ended the 1788–1790 Russo-Swedish War. 1791 – Slaves from plantations in Saint-Domingue hold a Vodou ceremony led by houngan Dutty Boukman at Bois Caïman, marking the start of the Haitian Revolution. 1814 – A cease fire agreement, called the Convention of Moss, ended the Swedish–Norwegian War. 1816 – The United Kingdom formally annexes the Tristan da Cunha archipelago, administering the islands from the Cape Colony in South Africa. 1842 – American Indian Wars: Second Seminole War ends, with the Seminoles forced from Florida. 1848 – Oregon Territory is organized by act of Congress. 1880 – Construction of Cologne Cathedral, the most famous landmark in Cologne, Germany, is completed. 1885 – Japan's first patent is issued to the inventor of a rust-proof paint. 1893 – France becomes the first country to introduce motor vehicle registration. 1900 – The Eight-Nation Alliance occupies Beijing, China, in a campaign to end the bloody Boxer Rebellion in China. 1901 – The first claimed powered flight, by Gustave Whitehead in his Number 21. 1914 – World War I: Start of the Battle of Lorraine, an unsuccessful French offensive. 1921 – Tannu Uriankhai, later Tuvan People's Republic is established as a completely independent country (which is supported by Soviet Russia). 1933 – Loggers cause a forest fire in the Coast Range of Oregon, later known as the first forest fire of the Tillamook Burn; destroying 240,000 acres (970 km2) of land. 1935 – Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act, creating a government pension system for the retired. 1936 – Rainey Bethea is hanged in Owensboro, Kentucky in the last known public execution in the United States. 1941 – World War II: Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt sign the Atlantic Charter of war stating postwar aims. 1947 – Pakistan gains Independence from the British Empire. 1959 – Founding and first official meeting of the American Football League. 1967 – UK Marine Broadcasting Offences Act declares participation in offshore pirate radio illegal. 1969 – The Troubles: British troops are deployed in Northern Ireland as political and sectarian violence breaks out, marking the start of the 37-year Operation Banner. 1971 – Bahrain declares independence from Britain. 1972 – An Ilyushin Il-62 airliner crashes near Königs Wusterhausen, East Germany killing 156 people. 1980 – Lech Wałęsa leads strikes at the Gdańsk, Poland shipyards. 1994 – Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, also known as "Carlos the Jackal", is captured. 1996 – Greek Cypriot refugee Solomos Solomou is shot and killed by a Turkish security officer while trying to climb a flagpole in order to remove a Turkish flag from its mast in the United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus. 2003 – A widescale power blackout affects the northeast United States and Canada. 2005 – Helios Airways Flight 522, en route from Larnaca, Cyprus to Prague, Czech Republic via Athens, crashes in the hills near Grammatiko, Greece, killing 121 passengers and crew. 2006 – Sri Lankan Civil War: Sixty-one schoolgirls killed in Chencholai bombing by Sri Lankan Air Force air strike. 2007 – The Kahtaniya bombings kills at least 500 people. 2013 – Egypt declares a state of emergency as security forces kill hundreds of demonstrators supporting former president Mohamed Morsi. 2013 – UPS Airlines Flight 1354 crashes short of the runway at Birmingham–Shuttlesworth International Airport, killing both crew members on board. 2015 – The US Embassy in Havana, Cuba re-opens after 54 years of being closed when Cuba–United States relations were broken off.

0 notes

Text

@focsle

OKAY, well, I was looking over the I&A timeline I made a while back to figure out when exactly Gil and his brother left Ireland. Based on my current plan for the story's timing, they would've left in 1849, roughly a year after their father died. And all of a sudden I was like--

"Huh. So their dad died in 1848. Wait...wasn't that the year of the failed Young Irelander uprising?"

COINCIDENCE? I THINK NOT.

So instead of dying of paternal incompetence liver failure and/or typhus, Virgil Abernathy was shot and killed by Irish Constabulary police during the Young Ireland rebellion in July 1848.

I could write a whole essay about WHY everything works better with this change, but uhh, here's the "short" version:

I think Gil's father being a martyr for Irish nationalism would've given him a more overtly political understanding of the hardship and hunger and tragedy of his childhood in Ireland.

That political understanding is what will give him a stronger and more ideologically driven motivation for being a devoted Tammany Hall Democrat. Otherwise, his main motivation would be his own personal self-interest, and for most people that's motivation enough, but it didn't feel convincing enough as a motivation for Gil.

I also have some ideas about how to tie this new backstory detail into his overall character arc, as part of the "ghost" feeding his "lie."

Aaand, finally, I'm changing his home county in Ireland from County Londonderry to County Tipperary (where the 1848 rebellion took place) which I think is more fitting in many ways. Tipperary is known for its ties to traditional Irish folk music, it was hit harder by the Famine than Londonderry was, and there are some neat lil tidbits of Irish folklore from that region that I can have some fun with if I want to play with Gil's memories of home.

In other news, I made a couple of decisions about I&A today including some changes to Gil’s pre-immigration backstory, and I think it’ll fix some issues I was having re: character motivation and conflict, so, YAY.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering the world

Ireland 🇮🇪

Basic facts

Official name: Ireland/Éire (English/Irish)

Capital city: Dublin

Population: 5 million (2023)

Demonym: Irish

Type of government: unitary parliamentary republic

Head of state: Michael D. Higgins (President)

Head of government: Simon Harris (Taoiseach)

Gross domestic product (purchasing power parity): $712.05 billion (2024)

Gini coefficient of wealth inequality: 27.9% (low) (2022)

Human Development Index: 0.950 (very high) (2022)

Currency: euro (EUR)

Fun fact: It is home to the oldest maternity hospital.

Etymology

The country’s name comes from Ériu, a goddess in Irish mythology.

Geography

Ireland is located in Northern Europe and borders Northern Ireland to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the east, south, and west.

The island has a subtropical highland climate. Temperatures range from 2 °C (35.6 °F) in winter to 20 °C (68 °F) in summer. The average annual temperature is 9.4 °C (48.9 °F).

The country is divided into twenty-six counties (contaetha). The largest cities in Ireland are Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Galway, and Waterford.

History

2800-1800 BCE: Bell Beaker culture

1200-800 BCE: Hallstatt culture

853-1170: Kingdom of Dublin

1169-1177: Anglo-Norman invasion

1177-1542: Lordship of Ireland

1536-1603: Tudor conquest

1542-1800: Kingdom of Ireland

1593-1603: Nine Years’ War

1641-1653: Irish Confederate Wars

1798: Irish Rebellion

1801-1922: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

1845-1852: Great Famine

1848: Young Irelander Rebellion

1867: Fenian Rising

1919-1921: Irish War of Independence

1922-1923: Irish Civil War

1922-1937: Irish Free State

1932-1938: Anglo-Irish Trade War

1937-present: Ireland

1968-1998: The Troubles

Economy

Ireland mainly imports from the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States and exports to the European Union, the United States, and Germany. Its top exports are blood, meat, and medicines.

Foreign multinationals are the main driver. Services represent 60.2% of the GDP, followed by industry (38.6%) and agriculture (1.2%).

Ireland is a member of the Council of Europe, the European Union, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

Demographics

White Irish people represent 76.6% of the population, followed by other white people (10.8%), Asians (3.3%), and Black people (1.5%). The main religion is Christianity, practiced by 75.7% of the population, 69.1% of which is Catholic.

It has a positive net migration rate and a fertility rate of 1.7 children per woman. 62% of the population lives in urban areas. Life expectancy is 80.1 years and the median age is 37.1 years. The literacy rate is 99%.

Languages

The official languages of the country are English and Irish. The former is spoken by 84% of the population, and the latter by 11%.

Culture

Ireland is a Celtic nation known for its music and dance. Irish people are known for their sense of humor and warmth.

Men traditionally wear a white shirt, a jacket (inar), a tweed skirt, and long, wool socks. Women wear a white blouse and a long skirt or a dress.

Architecture

Traditional houses in Ireland are made of stone and have thatched roofs and many windows.

Cuisine

The Irish diet is based on bread, meat, potatoes, and vegetables. Typical dishes include boxty/bacstaí (a potato pancake served with vegetables), coddle/cadal (a stew made of bacon, carrots, potatoes, and sausages), colcannon/cál ceannann (mashed potatoes with cabbage), goody (bread boiled in milk), and Irish stew/stobhach (a meat and vegetable stew).

Holidays and festivals

Like other Christian countries, Ireland celebrates Easter Monday, Christmas Day, and Saint Stephen’s Day. It also commemorates New Year’s Day.

Specific Irish holidays include Saint Brigid’s Day on the first Monday in February or February 1, Saint Patrick’s Day on March 17, May Day on the first Monday in May, June Holiday on the first Monday in June, August Holiday on the first Monday in August, and October Holiday on the last Monday in October.

Saint Patrick’s Day

Other celebrations include Fleadh Cheoil na hEireann, a music festival with parades; Fleadh Nua, which features dance workshops and concerts, and the Killorglin Puck Fair, where a wild goat is crowned king of the town.

Fleadh Cheoil na hEireann

Landmarks

There are two UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Brú na Bóinne – Archaeological Ensemble of the Bend of the Boyne and Sceilg Mhichíl.

Brú na Bóinne

Other landmarks include the Burren, the Cliffs of Moher, the Glendalough Round Tower, the Kylemore Abbey, and the Rock of Cashel.

Kylemore Abbey

Famous people

Becky Lynch - wrestler

Bono - singer

Conor McGregor - mixed martial artist

Enya - singer

James Joyce - writer

Maeve Binchy - writer

Packie Bonner - soccer player

Pierce Brosnan - actor

Saoirse Ronan - actress

Sonia O’Sullivan - athlete

Maeve Binchy

You can find out more about life in Ireland in this article and this video.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thomas Francis Meagher Quotes

Thomas Francis Meagher Quotes

Are you interested in famous Thomas Francis Meagher quotes? Here is a collection of some of the best quotes by Thomas Francis Meagher on the internet.

About Thomas Francis Meagher

Thomas Francis Meagher (3 August 1823 – 1 July 1867) was an Irish nationalist and leader of the Young Irelanders in the Rebellion of 1848.

Famous Thomas Francis Meagher quotes

The desired quotes are awaiting you…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#OTD in 1848 – A gunfight takes place between Young Ireland Rebels and police at Widow McCormack’s house in Ballingarry, Co Tipperary.

The Young Irelander Rebellion was a failed Irish nationalist uprising led by the Young Ireland movement, part of the wider Revolutions of 1848 that affected most of Europe. It took place on 29 July 1848 in the village of Ballingarry, South Tipperary. After being chased by a force of Young Irelanders and their supporters, an Irish Constabulary unit raided a house and took those inside as hostages.…

View On WordPress

#American Civil War#Battle of Ballingarry#Daniel O&039;Connell#Famine Rebellion#Famine Warhouse 1848#Irish Brigade#James Stephens#John Blake Dillon#John O’Mahony#Kilkenny#Michael Doheny#Mrs. Margaret McCormack#Richard O&039;Gorman#The Young Irelander Rebellion#Thomas Francis Meagher#Tipperary#William Smith O&039;Brien

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tweeted

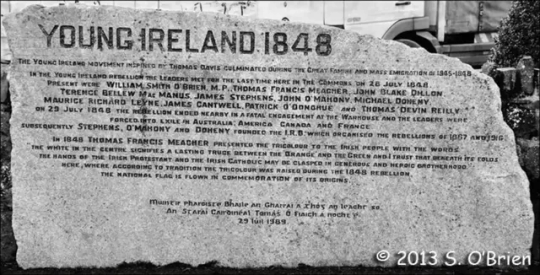

The Young Irelander rebellion took place on this day in 1848. At a time the Brits were attempting to wipe out the Irish through starvation. pic.twitter.com/1NujxhVG9A

— Crimes of Britain (@crimesofbrits) July 29, 2018

1 note

·

View note

Photo

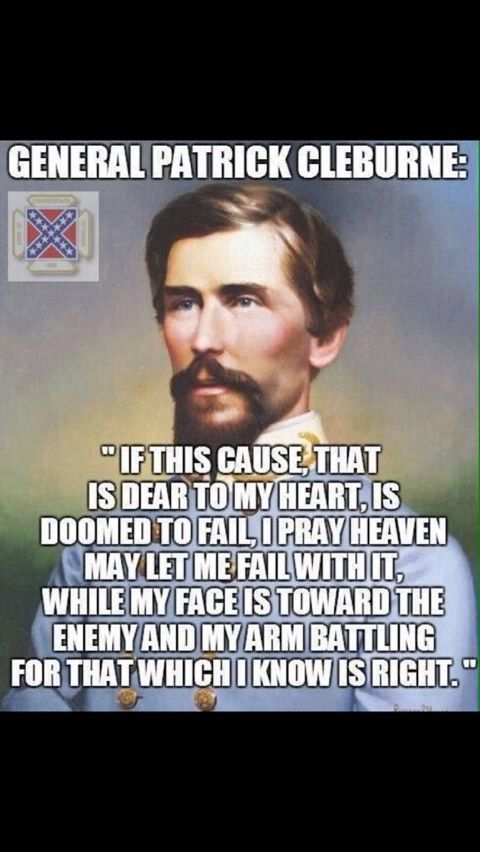

IF THE WORD DUTY WAS EVER PERSONIFIED, Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne was the carrying vessel. Do you admire individuals who carry deep convictions? How about one who exemplified his convictions in action, while also accepting the repercussions both good and bad? Patrick Cleburne's is an intriguing story of an Irish Immigrant who struggled in sheer determination to make his way in life. Cleburne rises through the military ranks as a non West Point Graduate to become a gallant Major General whose men adored him. This is a true story of what hard work and determination can accomplish. Patrick Cleburne was born in Ovens, County Cork, Ireland, on March 16, 1828, at Bride Park Cottage to Joseph Cleburne, a doctor, and Mary Anne Ronayne Cleburne. He was the third child and second son of a Protestant, middle-class family that included 2 brothers and a sister. His mother died when he was eighteen months old His father remarried Isabella Stewart and there were three half-siblings born to this union: Isabella, Robert, and Christopher. At age eight, the family moved to Grange Farm, near Ballincollig. While residing their Cleburne attended Church of Ireland Reverend William Spedding’s boarding school. His father would pass away unexpectedly of typhus in November 1843, having contracted it from a patient. “Ronayne,” as the family called him, was expected to carry on in the family profession of medicine. Cleburne's formative years while a child in Ireland were critical in the formation of a very grim and determined man. 19th century Ireland was a land ruled by feudal landlords who would drive their non rent paying tenants away with the bayonet. He attempted to become a physician and apprenticed for two years in an apothecary. When he failed the entrance exam at Trinity College, Dublin, he could not dare to face his family. Thus he enlisted in the 41st Foot in the British army. He found army life in Dublin to be extremely mundane. For three and a half years, Cleburne was posted at a barracks in famine-stricken Ireland. He served during the turbulent months of the 1848 Young Ireland Rebellion and was promoted to corporal on July 1, 1849. The 1840s were years of extreme political and social unrest in Ireland. The crisis deepened after the Irish potato crop failed in 1846. Relations between landlords and tenant laborers deteriorated quickly. Laborers, who usually paid in potatoes, could not pay their rents. Landlords then demanded cash for rent, but with no crop to sell landlords had no cash. It was a vicious cycle that erupted in widespread violence. Hungry, desperate laborers revolted and some landlords were murdered. Cleburne’s regiment was assigned to assist local police in evicting tenants that could not pay. He found himself in the position of guarding food from his fellow countrymen to protect his own social class and the oppressive English government. The famine continued and thousands died in poverty in their homes, by the roadside and in the streets. It is estimated that up to 500 people died in Cork City per week, Food riots and looting increased. Cleburne returned home to find his own family farm in arrears for six months rent. On September 22, 1849, he paid £20 for his discharge from the army and received his papers. In the space left on the discharge for a statement of character was written, “A good soldier.” Cleburne kept the paper for the rest of his life. Cleburne and his family decided to journey to a new life in America in the decade before The American Civil War. Cleburne loved his new country. His family would split up as job opportunity presented soon after arrival in America. Patrick would eventually land in frontier Helena Arkansas poulation 600. Just months later he learned that two physicians in Helena, Arkansas Hector Grant and Charles Nash needed a druggist to manage their store. Nash told Cleburne they needed a competent prescriptionist who could manage the entire shop. In a month, Cleburne had brought complete order to and become the manager of the Grant and Nash Drugstore. As compensation he received $50 a month, a room in the back of the shop, and meals he took with Dr. Grant. He would eventually through grit and diligence earn his way to become a full partnered small businessman. He then dedicated himself to the study of becoming a lawyer. He would soon after be selected a delegate to the Democratic Convention in 1858. Cleburne never owned slaves and often voiced his opposition to the institution. Yet he strongly valued the right and desire of a section of the country to govern itself. Once the American Civil War begins, Cleburne joins the Confederacy purely out of an adoration and loyalty for a society that accepted him and simply gave him a chance. Much of his philosophy was based on witnessing the Irish fight for independence in his homeland. After enlisting He quoted; "If this [Confederacy] that is so dear to my heart is doomed to fail, I pray heaven may let me fall with it, while my face is toward the enemy and my arm battling for that which I know to be right.” Sadly, that wish would tragically be fulfilled. The Yell Rifles were formed in the state to become part of the First Arkansas Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Cleburne was elected it's colonel. The First Arkansas was attached to the Army of Tennessee, the main Confederate force in the western theater. Cleburne was promoted to brigadier general in March 1862, and participated in the Battle of Shiloh in April and in the 1862 Kentucky Campaign. At the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky, on August 30, Cleburne was struck in the face by shrapnel and forced to leave the field. He remained away from the army until his recovery six weeks later, He returned to duty for the Battle of Perryville in October. On December 14, 1862, he was promoted to major general. He then commanded at Stones River. During 1863, Cleburne participated in major battles at Chickamauga and Missionary Ridge. On November 27, 1863, his division made a critical stand at Ringgold Gap, Georgia, while as the rearguard protecting the retreating Confederate army. His scant division of 4,000 men managed to fiercely hold back 15,000 of General Joseph Hooker’s Union troops. Cleburne received a Congressional citation from the Confederate Government for his brilliant performance. On January 2, 1864, Cleburne made his most controversial decision ever. He gathered the corps and division commanders in the Army of Tennessee to present a very radical yet extreemely logical proposal. The Confederacy was unable to fill its ranks due to a lack of manpower. Cleburne's correct yet politically charged "Memorial" was designed with the idea to arm the southern slaves for Confederate military service in exchange for their freedom. It was most thoughtfully and brilliantly crafted. However the proposal was not well received at all. Most knew that it was a political time bomb that would stir great controversy. In fact, Jefferson Davis directed that the proposal be suppressed. It was met with so much controversy that it virtually scuttled any chance of Cleburne's further promotion in the ranks. Here is a copy of the full text: Commanding General, The Corps, Division, Brigade, and Regimental Commanders of the Army of Tennessee General: