#Yoshito Matsushige

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A handful of people in Pompeii that were killed by the devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 are not who experts thought they were, according to a team of researchers that recently collected DNA from the individuals’ remains. The team’s findings—published today in Current Biology—spotlight previous incorrect conclusions about relationships between the residents of Pompeii and reveals new insights about the demographics of the Ancient Roman port city. “We show that the large genetic diversity with significant influences from the Eastern Mediterranean was not only a phenomenon in the metropolis of Rome during Imperial times but extends to the much smaller city of Pompeii, which underscores the cosmopolitan and multi-ethnic nature of Roman society,” said Alissa Mittnik, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Harvard University, and co-author of the study [...] Demographically, the team found that five individuals in Pompeii weren’t so genetically associated with modern-day Italians and Imperial-period Etruscans as they were to groups from the eastern Mediterranean, the Levant, and North Africa—specifically North African Jewish populations. Pompeii was an important port in first-century Rome, so it’s not a huge surprise that it had representation from across the Mediterranean—but the genetic stories of the studied individuals verifies it. [...] “This study illustrates how unreliable narratives based on limited evidence can be, often reflecting the worldview of the researchers at the time.” One particularly famous set of remains revisited by the team is that of an adult with a golden bracelet and a child—the child being on the adult’s lap. Long interpreted as a mother and child, the remains actually belong to an unrelated male and a child.

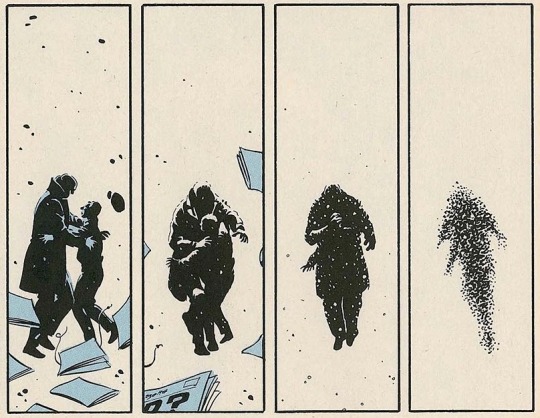

"Unrelated." This gutted me, for some reason. Reminded me of Watchmen and what I think are some of the most memorable panels in the history of comics.

There's a catastrophe, a colossal explosion, a disaster that we know claims the lives of millions. We know it's happening, we know there's a "psychic shockwave" involved. And there's two people we've been casually following from the start of the story, ordinary people in the street, unlike all those costumed heroes running around. They're not very good and they're not very bad. They're just people. One is an old man running a news-stand, the other is a young kid who reads pirate comics. They don't like each other. They're rude to each other, generation gap and all. Two minutes ago they learned they share a name, and managed to share an almost kind word, and they're about to start fighting again. They're just people, right? And then the disaster happens. We don't see it yet. The blood and gore will be witnessed in the next issue. For now, the background fades to white, and we only see them.

They drop what they're holding, they hug, the old man puts his arms protectively around the young kid, and they fade. They fade into the shape of the Watchmen logo, ubiquitous throughout the comic, and then they fade out. White panel. There's nothing left. And off-panel, the Ozymandias quote.

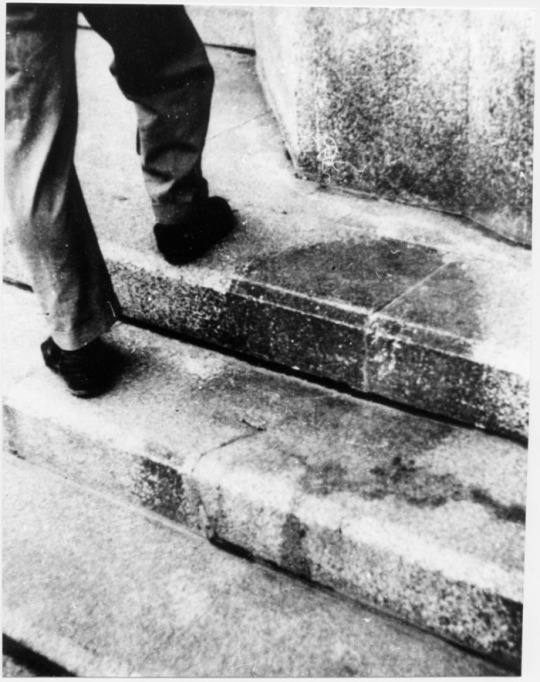

Watchmen primarily aimed to evoke nuclear war, and the "psychic shockwave" clearly stands for the blast of a thermonuclear explosion. What makes the sequence gut-wrenching is the hug (so tender and so futile), the fade-to-white (a negative space so understated and so enormous), and the penultimate panel: an after-image frozen in time, declaring forever "once there were people here". Just like the plaster casts of Pompeii, just like the stones of Hiroshima.

Hiroshima, August 6th, 1945: the shadow of a person who was disintegrated at the moment of the blast. The steps and the wall were burned white, except the portion that was shielded by the person's body. (These steps were cut out and are now inside the Hiroshima Peace Park museum.) Photo by Yoshito Matsushige, whose films were confiscated and didn't get printed until the U.S. occupation ended in Japan in April 1952.

#theory#the city speaks#pompeii#rome#analysis#trs#Watchmen#Alan Moore#Dave Gibbons#comics#photography#Yoshito Matsushige

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Today, August 6, marks the 78th anniversary of the destruction of Hiroshima by an atomic bomb dropped on the city by the United States during the Second World War.

Tokyo: America’s pathologies are, in my experience, more apparent (though no less troubling) from afar. The simultaneous release of the films Barbie and Oppenheimer resulting in the distasteful but hardly surprising “Barbenheimer” meme is a case in point: America’s twin obsessions of how it looks in the mirror and how it’s remembered in the history books have collided head on, leaving a twisted mess of wreckage – however harmless at this point – revealing more about our culture and ourselves than we care to admit.

As someone who has yet to see either film, I’ll withhold judgment on the filmmakers’ vision and their success or failure in realising it on the big screen. Like last year, I’m happy to report that I’m spending much of this summer in Japan visiting family, meaning my 11-year-old son’s grandparents and a whole host of welcoming uncles, aunts, cousins, nephews, nieces, and neighbours.

These, it should be said, are exactly the kind of ordinary Japanese folks that director Christopher Nolan chose to leave out of his film about the “mastermind” of the atomic bomb, and precisely the people who suffered and died in the hundreds of thousands when the US dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I respect Nolan as a filmmaker and, once again, will withhold judgment until I see the film. Being in Japan – which has yet to set a release date for Oppenheimer, but is expected to later this year after the August 6 and August 9 anniversaries of the 1945 atomic bombings – I haven’t had the opportunity to see his film, which I certainly will see. I have, however, had the opportunity to visit Hiroshima on a number of occasions, first as a young journalist nearly 30 years ago, and last summer with my wife and son.

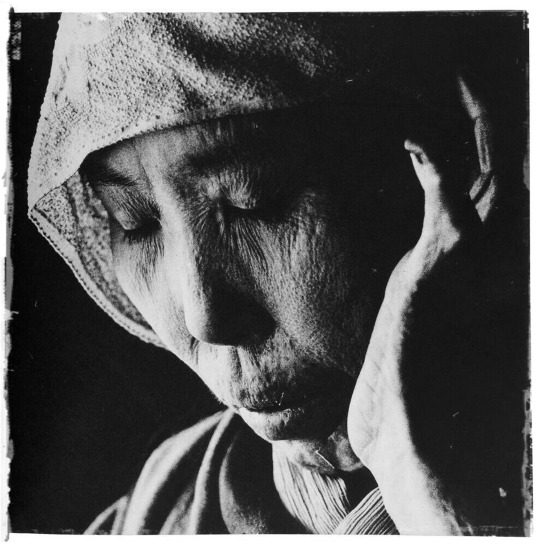

On that first visit in 1995, not long before the 50th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, I had the great honour of interviewing Yoshito Matsushige – a photographer for the local newspaper who was just 2.7 kilometres from the hypocentre when the blast occurred at 8:15 that August morning.

As I wrote last August in Hiroshima’s Message, “His immediate reaction was to grab his camera and head toward the fire. But when he saw ‘the hellish state of things’ he couldn’t bring himself to take pictures. ‘It was great weather that morning,’ he said, ‘without a single cloud. But under that blue sky, people were exposed directly to heat rays. They were burned all over, on the face, back, arms, legs—their skin burst, hanging. There were people lying on the asphalt, their burnt bodies sticking to it, people squatting down, their faces burnt and blackened. I struggled to push the shutter button.’”

After what seemed like an eternity, Matsushige said, he finally brought himself to take two pictures of people, suffering horribly, who had gathered on Miyuki Bridge, about 2.3 kilometres from the hypocenter. Many were middle-school children, their bodies terribly burned. Someone was applying cooking oil to their wounds. He remembered asking them for forgiveness, wiping away his tears, and saying “I just took a picture of you as you are suffering, but this is my duty.”

In all, Matsushige snapped his shutter just seven times – the only photos taken in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, that survive to this day. He died in 2005, at the age of 92, a dedicated peace activist who shared his story with people around the globe, including before the UN General Assembly.

Christopher Nolan has said his film – which was inspired by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Oppenheimer, American Prometheus – is focused more on the moral dilemmas facing the scientist tasked with making a bomb that could end World War II than on making a war “documentary.”

“He [Oppenheimer] learned about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the radio—the same as the rest of the world,” Nolan told MSNBC’s Chuck Todd. “That, to me, was a shock… Everything is his experience, or my interpretation of his experience. Because as I keep reminding everyone, it’s not a documentary. It is an interpretation. That’s my job.”

Fair enough. But I can’t help thinking of the photographer Matsushige and what he told me over a quarter-century ago, while taking pictures of children whose clothes and skin were charred and hanging from their bodies when only a few moments prior they were walking to school on a clear August morning: “I just took a picture of you as you are suffering, but this is my duty.”

Below is an interview, also from 1995, with the then-mayor of Hiroshima, Takashi Hiraoka, who, coincidentally, was a journalist before entering politics and worked for the same newspaper as Matsushige, the Chugoku Shimbun. I remember him as a true gentleman in his mid-60s, at ease with his role in local politics and passionate about sharing Hiroshima’s “Never Again” message with the world.

Now 95, Hiraoka served eight years as mayor of Hiroshima before retiring in 1998. Since our interview, two more countries – Pakistan and North Korea – have joined the nine-member “nuclear club.” According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the US, the UK, Russia, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea have among them nearly 16,000 nuclear weapons, all of which are many times more powerful than the two bombs dropped on Japan in August 1945.

Excerpts from the 1995 interview of the then-mayor of Hiroshima, Takashi Hiraoka, as published by The Japan Times Weekly, August 5, 1995. Used with the author’s permission

MJ: As mayor of Hiroshima, what is your message to the world on the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing?

TH: The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki marked not only the end of World War II but the beginning of the nuclear age. In this respect, the bombings were a tragedy for all of humanity. The people of Hiroshima have chosen to see their experience as a lesson for humanity. The 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima is an excellent opportunity for us to look back on our past and think about our future.

Our message has always been that the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki should never be repeated. Now that we have reached the half-century landmark, this message should be re-emphasized, together with the call for nuclear disarmament. I see the 50th anniversary as an opportunity to come together with the people of the world so that we can work toward the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Japan does not consider the use of nuclear weapons to be against international law. What is Hiroshima’s official stance on the deployment of nuclear weapons ?

As the first city to have experienced a nuclear attack, we firmly believe that the use of nuclear weapons violates international law. We believe this for two main reasons. The first is the indiscriminate nature of nuclear weapons. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to restrict the destructive power of nuclear weapons. The second reason is the extraordinary cruelty of nuclear weapons. What I mean by this is that there are still many hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) suffering the effects of radiation exposure.

International law prohibits the deployment of weapons that inflict unnecessary suffering on human beings such as “dumdum” bullets and chemical weapons. The United Nations General Assembly has passed a number of resolutions prohibiting the use of nuclear weapons for the very same reason.

The Japanese government has three non-nuclear principles: not to produce, possess, or harbour nuclear weapons. We must continue to push the government to uphold these three principles. Unfortunately, the Japanese government does not have a strong stance toward U.S. foreign policy because it wants to maintain good U.S.-Japan relations. But I think the Japanese government should have a stronger stance toward the United States, particularly in regard to its nuclear-weapons policy.

In what ways does the city of Hiroshima influence the governments of other nations? How do you get your message across to the world?

Whenever a foreign country conducts a nuclear-weapons test, we immediately send a telegram protesting the test and calling for an end to further nuclear-weapons testing. We also have a program called the International Conference of Mayors for Peace Through Inter-city Solidarity. Currently, 404 cities in 97 countries are a part of the program and support our call for the total abolition of nuclear weapons. The purpose of the program is to contribute to lasting world peace by strengthening the ties between the cities of the world…

Hiroshima and Nagasaki have long been calling for the total abolition of nuclear weapons. How can this goal be attained when many countries—Iran and North Korea, for example—see having a nuclear-weapons program as the key to gaining respect on the world stage?

This is a very difficult problem, and one the whole world will have to work on together to solve. We must continue to tell the citizens and leaders of the world that possessing nuclear weapons will never be a positive thing. Governments justify their nuclear arsenals with language like “national security.” But what about global security?

Not only does nuclear war mean the annihilation of humans, but every time a nuclear weapon is tested, the environment is irreparably damaged. What we have to do is raise public awareness of the dangers. We can push for the ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty as soon as the negotiations are completed next year…

[Apart from the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty] … we must also enact a law or treaty that ensures nations which possess nuclear weapons will never use them against nations that do not. Such a treaty will ease the concern of nations that do not have nuclear weapons and, hopefully, lessen the incentive to initiate a nuclear-weapons program.

We must also have strict control over the materials required to produce nuclear weapons. Those countries currently trying to develop nuclear weapons feel they are not given equal consideration in international politics. So, on the one hand, we need strict control over nuclear materials, and on the other we have to address the needs and concerns of all the nations of the world in equal measure.

In the United States and Japan, there was a great deal of controversy over a commemorative stamp that was to be issued by the U.S. Postal Service. The stamp, which was never issued, featured a painting of an atomic mushroom cloud accompanied by the caption “Atomic bombs hasten war’s end, August 1945.” What kind of message do you think it sends the people around the world?

I have many reasons to believe that the statement “Atomic bombs hasten war’s end” is simply not true. By August 1945, Japan had neither the ability nor the will to continue waging war. The Japanese government was trying to find a path to peace as early as the spring of 1945. I believe the U.S. government was aware of this when it decided to drop the atomic bomb.

If the United States had wanted only to end the war, it did not have to use nuclear weapons. The United States possessed more than enough conventional weapons to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki and to end the war. There are many different opinions as to why the U.S. government decided to drop atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I would like to leave the answer to the scholars, but I do have a question. In 1945, President Harry Truman said that dropping the atomic bombs saved 250,000 to 500,000 lives. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan said dropping the atomic bombs saved one million American soldiers’ lives. In 1991, President George Bush said that several million lives were saved as a result of the atomic bombings. I wonder what this change means? I understand that the U.S. government uses these figures to justify the bombings, and that once a government has committed itself to a certain policy or decision, it does not want to change its stand.

But why do the numbers keep rising? Before the atomic bombs were dropped, many U.S. officials, including military personnel, argued that the bombings were not needed to end the war.

What is your reaction to the Smithsonian Institution’s decision to scale back its controversial Enola Gay exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C.?

A couple of years ago the Smithsonian Institution had an extensive exhibition on World War II that included an exhibit on the plight of the Japanese Americans who were interned during the war. Due in part to this exhibit, the U.S. government admitted that its policy was a mistake and compensated the surviving Japanese Americans who had been interned. This led me to believe that the people at the Smithsonian Institution were committed to historical accuracy.

Now, the Smithsonian has yielded to political pressure and has missed an opportunity to thoroughly examine the history surrounding the bombings. I am disappointed with the Smithsonian’s decision, as are many people of conscience in this world. We could spend hours talking about whether the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were justifiable or not, but such discussion is futile—it happened 50 years ago. What we have to do now is learn from the experience and make sure it never happens again. We are not asking for an apology.

Some Americans say that we are trying to make ourselves look like innocent victims, that we are indulging in our grief in an attempt to diminish the atrocities committed by the Japanese military during the war.

Nothing could be further from the truth. As the mayor of Hiroshima I acknowledge that the Japanese military carried out a war of aggression and committed many atrocities. I have personally done a lot of soul-searching on this subject and have publicly apologized to those who suffered at the hands of the Japanese military. I would also like to add that if nuclear weapons are not abolished, the horrors that Hiroshima and Nagasaki experienced will be experienced by others. The question is not if but when it will happen. The nuclear weapons that exist today are tens of thousands of times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Obviously, a tragedy brought about by a nuclear war today would be far greater than the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Why do you think the Smithsonian Institution decided against displaying photographs of and items belonging to the victims of the bombings?

It seems many Americans are not willing to face the reality of what happened after the bomb was released, but for humanity that is where the lesson begins. Hiroshima’s mission is to let the people of the world know what happened on the ground—what happened to the people of our city. I first came to Hiroshima in September 1945, so I remember very well the devastation and the initial rebuilding of the city. What moved me most was the strength of the survivors. That strength has evolved into a determination to prevent others from experiencing the horrors of nuclear war.

They feel it is their duty to make a constant appeal for world peace and nuclear disarmament. This is their mission, and with this mission they have overcome their tragedy. They do not harbor any hatred toward the American people. Instead, they have chosen to work for peace. The people of Hiroshima have come to understand what peace means for the world. And as the mayor of Hiroshima, I am very proud of them.'

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yoshito Matsushige (1913-2005)

Hiroshima, august 6, 1945

from X-Ray Japan 1945, Daniel Blau

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yoshito Matsushige

Dazed survivors huddle together in the street ten minutes after the atomic bomb was dropped on their city, Hiroshima

August 6, 1945

#yoshito matsushige#black and white#vintage#photography#black and white photography#vintage photography#1940s

177 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hablar de Yoshito Matsushige, que sobrevivió en 1945 al bombardeo nuclear de Hiroshima no es difícil, lo verdaderamente difícil es ponerse en su lugar e intentar entender lo que debió sentir y pasar por su cabeza en aquel momento. Gracias él hoy, mediante sus fotografías y "palabras" podemos atisbar, aunque sea vagamente, lo que fue el verdadero horror de vivir aquella terrible experiencia: su experiencia

0 notes

Photo

From the book:

HIROSHIMA-NAGASAKI Document (1961)

* Shomei Tomatsu; Ken Domon; Juichi Nagano; Orahiko Ogawa; Yoshito Matsushige; Iri Maruki; Toshiko Maruki etc.

Publisher: The Japan Council Against A & H Bombs (Tokyo) Publication Date: 1961 Edition: First Edition

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Ground Zero to Provoke: Trauma and Memory in Postwar Japanese Photography

Neil Matheson’s lecture - 01.02.2019

Think to know before getting into it (at least for me): Nuclear weapons have been used to end the war by the Americans against Japan, trying to avoid a ground invasion (which would apparently had made much more death). Also, Japanese soldiers were very dedicated to their cause and were willing to die for it.

It was the first time nuclear weapons ever used on civilians, dropped first on Hiroshima on the 6th August 1945 and a second time, three days later on Nagasaki. There are still wonders if using the nuclear weapons was really justified.

The Americans took occupation in Japan after it for approximatively 7 years and try to get rid of most of the images made on the days of both attacks. By doing so, not only they took the evidences away but also stopped victims from dealing with their trauma.

Toshio Fukada, Hiroshima, 6 August, 1945

Trauma: Traumatisme (psych.) Hibakusha: term use to talk about people affected by the explosions.

Cathy Caruth: writes about trauma. Unclaimed experience: Trauma, narrative and history, 1996

Collective Trauma: ‘Collective trauma occurs when members of a collectivity feel they have been subjected to a horrendous event that leaves indelible marks upon their group consciousness, marking their memories forever and changing their future identity in fundamental and irrevocable ways’. Jeffrey C. Alexander, Trauma: A Social Theory, 2013

Victims were “bullied”, feared as many people didn’t know how or what happened due to the lack of informations transmitted about the attacks in the rest of the world and in Japan. Society’s attitude towards people suffering from the attack wasn’t really nice.

How the informations started to come out:

New Yorker, 31 August 1946

John Hersley, Hiroshima (book, only available in Japan in 1949)

Hiroshima, Scene of a-Bomb explosion, 1953 Made it possible to deal with the trauma created by the attack. Was free and widely distributed.

The Media Aftermath

Yoshito Matsushige, a Japanese photojournalist, took 7 exposures on the day of the attack, but only 5 survived. Not used to this kind of difficult environment, he had to force himself. Everything that was shot on that day had to be hidden underground due to the Americans. Some of the negs from that day got damaged due to those conditions.

Both photos above on the left: Yoshito Matsushige, Hiroshima, 6 August 1945 Right photo: Yösuke Yamahata, Nagasaki, August 10 1945

Yösuke Yamahala, war photographer, was sent to Nagasaki after the attack to record it. Used to work in difficult conditions, his work was more organised, showing the immediate aftermath. His record of the event is seen as more humanist (a bit like Cartier-Bresson). Questions were raised about producing such well-composed images in such terrible conditions.

Japanese also made movies to get over their trauma such as for example Gozilla.

Other artists who created art based on the attacks:

Ken Domon, Hiroshima, 1958 (photographs)

Kikuji Kawada, Chizu - The Man, 1965 (a bit abstract / physical damaged / photo commemorating children lost in the war)

Adam Renais, Hiroshima mon Amour, 1959 (film) (what is the role of forgetting? - denial, repression)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The real photos of the Hiroshima bombing tell the story - no need for fictionalised ones.

The real photos of the Hiroshima bombing tell the story – no need for fictionalised ones.

Bad Idea: The New Yorker’s Nuclear Option, Peta Pixel AUG 12, 2021 ALLEN MURABAYASHI, On August 6, 1945, the U.S. detonated the world’s first wartime nuclear bomb over Hiroshima. An estimated 70,000 people died that day with another 70,000 perishing within four months from injury and radiation poisoning. On the ground, photojournalist Yoshito Matsushige miraculously survived unharmed despite…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Hiroshima

The Peace Memorial Museum is the perfect-sized building, that is, not too large. It’s a Shinto temple filtered through Corbusier. When I visited earlier this year, part of the museum was under renovation, the exhibit took about an hour.

The exhibit opens with two small antechambers of photographs. The first is a grid of photographs of the mushroom cloud from various angles. There's a New Topographics feel to this grid. These photos show different perspectives on the cloud, but none of the photographers were far enough way to capture the shape we all recognize. The grid turns the views into a cubist rendering and I was left with the curiosity the photographers must have experienced: What just happened? What am I looking at?

The second space has one large square photograph by Yoshito Matsushige. This is one of the remarkable stories of 20th century photography that I wasn't aware of before visiting. There are five known frames taken inside Hiroshima that day, taken by Matsushige with a 6x6 camera. He developed them in a river. In an interview, Matsushige said he would have taken more photographs of people, but he felt they were so ravaged that they might attack him. Despite his own exposure, he lived until 2005 (aged 92).

I stood in front of this photograph for several minutes. Unlike the grid of mushroom clouds, you are no longer at a safe distance. The enlargement shows damage to the negative. Everyone has their back turned to the camera and, based on Matsushige's story, that makes sense. It's a powerful photograph because it doesn't feel composed. It doesn’t feel like he was chasing the most shocking scene he saw that day. You feel his caution. It feels like a random moment. The chaos of the composition builds on the mushroom cloud grid, it's very ominous, you know that you have not seen the worst.

The rest of the exhibit is a mix of artifacts, information graphics and smaller photographs. There are many photographs of victims suffering with burns. Around the perimeter of several galleries are outfits of damaged clothing. These are stories of children in school uniforms that made it home, dying of burns and radiation. Hiroshima is a large story to tell, with global implications that are relevant to this moment, but at times it feels like a museum about burning children alive.

The exhibit lighting is very dim, I'm guessing to protect the artifacts and maintain atmosphere. I haven't been to the concentration camps, but I imagine it's like this: You find yourself quietly weeping with people from all around the world.

As a child, first grasping to understand the effects of a nuclear bomb, the thing that fascinated me was that you can be incinerated in an instant. "Vaporized" is not the most accurate word, but it's a word often used. A human life turned to dust, something out of science fiction. The fire bombing of Tokyo also killed a staggering number of people, but what makes nuclear war different is speed and intensity. A city and it's population turned to dust, not over days, but in seconds. There's a corner of concrete from a bank where supposedly you can see the shadow of a person incinerated. It's a very faint fixed shadow, perhaps not the most accurate word, but a photographic representation of a human life vanished.

They also have figures, people with sheets of skin peeling off, with a painted scene of the city burning in the background. The models and the concrete shadow feel like exhibits from a previous era and hopefully will be updated. It’s difficult to imagine what would be a 'successful' exhibit at Hiroshima. The challenge is to not allow the museum to feel entirely historical, to calmly present the threat we live with, with the evidence of that day.

Hiroshima altered my perspective. There are other large, civilization-threatening problems that we read and think about more frequently, because they are all easier to consider than nuclear war. We rationally know how small probabilities work over time. The stakes are always Hiroshima. And it’s insane that each generation has passed this shrieking, awful horror down to the next.

Related:

Yoshito Matsushige at the Atomic Photographers Guild

John Hersey's book-length history of the atomic bombing, published a year after the bombing

Shōmei Tōmatsu’s photographs Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document 1961

Michael Lewis writing about the Department of Energy

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hiroshima Mon Amour

Un romance en medio del olvido y la crueldad de la guerra, llevan al desborde de sentimientos y pasiones entre dos circunstancias, dos países, dos razas, dos soledades, dos profesiones, dos experiencias, y un solo amor bajo la lente de una nueva ola cinematográfica.

Hiroshima. La ciudad, la bomba, la tragedia. Ciudad donde tras años del fatal acontecimiento grabado a lo largo y ancho de una ciudad que decidió seguir adelante y que ahora abre su espacio a una historia de amor algo tórrida y a la vez llena de poesía, pasión y dolor.

Ella una actriz francesa. Él, un arquitecto japonés. Dos mundos que dan rienda suelta a un sentir, conflictivo, en especial por parte de la protagonista; quien desde mi punto de vista personal, torna la relación en algo gris y llena de altibajos tras recordar su antiguo amor y su posterior muerte. Creo que los protagonistas tenían en común algo: buscaban olvidar sus propias marcas, su propio dolor, para tener un nuevo presente.

Desde el punto de vista técnico, el director se vale de una narración que nos permite ver el uso de la voz en off de la actriz por largos periodos, gran cantidad de flashbacks sobre los momentos siguientes al estallido de la bomba y las secuelas de la misma, instrumentos visuales que llevan al espectador a situarse y recordar la crudeza de la tragedia, evidenciando lo terrible del ataque. Ésta película desde su inicio, (toma de los dos cuerpos desnudos), nos lleva a un recorrido fotográfico donde la iluminación hace su presencia con delicadeza y mucho impacto, dejando entrever sombras, figuras y un entorno inquietante y a su vez locuaz. Es decir, las imágenes hablan por sí solas y llevan a quien las ve de forma inmediata a conocer o por lo menos a imaginar de qué se trata lo que está viendo sin ser explícito.

El manejo de diferentes planos, tomas cortas y rápidas que dan un efecto como de un collage; todo hecho a una sola cámara, el travelling del inicio que lleva al público en un corto recorrido por la nueva ciudad dan gran versatilidad y hablan del conocimiento del director en lo que a movimientos y planos de cámara se refiere. La limpieza de las tomas y la simplicidad de los planos permiten que la película nos regale una perspectiva de emociones (p.ej. terror, miedo, tranquilidad, agrado, expectativa) al ver escenas fuertes como al inicio de la cinta; y a la vez poder disfrutar de paisajes hermosos y únicos como los observados en el rio en Nerves.

Aprovecho para recordar a Yoshito Matsushige, fotógrafo que captó los momentos después de la bomba de Hiroshima. En sus fotos vemos su perspectiva y el por qué las mismas cautivaron al mundo al mostrar el verdadero horror que causó la bomba atómica.

Vale la pena recalcar que en la película se alcanza a evidenciar la reconstrucción de edificios que hoy en día hacen parte de la historia de la ciudad de Hiroshima como “El museo de Hiroshima”, donde reposan muestras del sufrimiento y la angustia vividos en el ataque y después de éste, imágenes donde la mayoría de fragmentos del horror se evidencian de manera más real.

Si fuese un crítico de cine, resaltaría de manera muy personal el uso de la iluminación y creatividad del montaje fotográfico al recrear la grabación tanto en interiores como en exteriores. Podría afirmar que el director hace uso de sus herramientas cinematográficas (el lente, el guion, los encuadres, las locaciones y hasta los mismos actores), para llevar de manera exitosa su puesta en escena. Aunque quizás los diálogos puedan parecer para algunos confusos o sin sentido; estoy convencido que un filme de este tipo, corto, realista, crudo por momentos pero por sobre todo sencillo y puntual; reflejan el objetivo del guionista y produce en el espectador sensaciones y sentimientos nuevos –por lo menos para la época en que fue llevada a los cines-.

1 note

·

View note

Link

“Those of us who encountered every one of these hardships, we trust that such enduring will never be experienced again by our kids and our grandkids.

Our kids and grandkids, yet all future ages ought not need to experience this disaster. That is the reason I need youngsters to tune in to our declarations and to pick the correct way, the way which prompts harmony.

” ~ Yoshito Matsushige (picture taker)

0 notes

Photo

74 years ago today the atomic bomb was dropped on Hirohima, August 6th, 1945, the The very first pictures taken in Hiroshima was by Yoshito Matsushige who was just outside the blastzone; he looked out of his window into a large mushroom cloud, and took the only photographs taken of Hiroshima on that calamitous day. Of his 24 possible exposures, only seven came out right. The Red lights are flashing. India & Pakistan, one of the most dangerous nuclear situations in the world, just got more dangerous. Iran had a nuclear program. We had it under control. Removing the JCPOA has made it more dangerous. North Korea has had a nuclear program. We entered into talks with them. During the time that we’ve been in the talks with them. During the time we’ve been in talks with them, they’ve built more nuclear warheads, they’ve tested more missiles. North Korea is materially more dangerous today than it was at the beginning of these talks, even if the talks themselves were a good idea. Russia has more nuclear warheads than anybody and we are taking apart our nuclear treaties with Russia. One could argue that this is as dangerous a moment as has existed on the nuclear front in many, many years. It’s a rough time in the United States. It’s a rough time in the world. With luck, we are a year and half away from having people who study & immerse themselves in issues like this, re-empowered because the country & the planet cannot afford another four years of evil & stupid & ignorant & incompetent in the role they currently play in our domestic and foreign policy. Source: David Rothkopf https://www.instagram.com/p/B00jHKKHhbl/?igshid=mj37m8fbseva

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Dazed survivors huddle together in the street ten minutes after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945 (Yoshito Matsushige) [1000x1024] Check this blog!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

As Hiroshima Observes 73rd Anniversary of Atomic Bombing, 'Tensions between Nuclear-Armed States Are Rising and Nuclear Arsenals Are Being Modernized'

As Hiroshima Observes 73rd Anniversary of Atomic Bombing, ‘Tensions between Nuclear-Armed States Are Rising and Nuclear Arsenals Are Being Modernized’

Human Wrongs Watch

The world needs the continued moral leadership of the people of Hiroshima, the top United Nations disarmament official on 6 August 2018 said, commemorating the 73rd anniversary of the atomic bombing that devastated the city while lamenting that after decades of momentum towards a nuclear-free world, “progress has stalled.”

UN Photo/Yoshito Matsushige | Injured…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

From Ground Zero to Provoke: Trauma and Memory in postwar Japanese photography

The nuclear attack on Hiroshima, August 6th 1945

Atomic bomb attack on Nagasaki, August 9th 1945

How did photographers get across the situation that victims of these traumas found themselves in?

The concept of ‘collective trauma’ - Occurs when members of a collectivity feel they have been subjected to a horrendous event that leaves indelible marks upon their group consciousness, marking their memories forever and changing their future identity.

John Hersey, Hiroshima

Hiroshima, scene of A-Bomb Explosion, 1953

Authored rather than anonymous images – how specific photographers dealt with these events.

Yoshito Matsushige, Hiroshima, 6th august, 1945. Injured policeman issuing certificates to civilians.

Hiroshima, the shadow of someone obliterated by the blast. – Imprint of a person who was sat there when the bomb went off.

The images are metaphors for the events that occurred.

Amateur images that capture the immediacy of the aftermath of the bombings themselves.

Yosuke Yamahata, Nagasaki, August 10th 1945.

Gojira (Godzilla), Dir. Isihiro Honda, 1954 – Shannon Stevens – ‘The film performed a vital theraputic function for a society traumatized both by atomic bombings and by an oppressive regime that forbade all discussion of the trauma’

Retribution because of the nuclear bombings.

Ken Domon and Shomei Tomatsu, Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document, 1961

Shomei Tomatsu, Melted Bottle, from the series Nagasaki 11.02, 1961 – Embodiment Theory - how do we experience a photograph? Do we just experience it visually or are other senses stimulated by it?

Kikuji Kawada, Chizu – The Map, 1965

Alain Resnais, Hiroshima Mon Amour, 1989 (film) - Male character saying its unrepresentable unless you were there to witness the event. Superficial notion in comparison to someone who lived there and experienced it.

Miyako Isiuchi, Hiroshima, 2008.

Shomei Tomatsu:

Iwakuni, 1960

Yokosuka, 1959

Tokyo, 1960

Chewing Gum and Chocolate (2014) – culture, riding a mushroom cloud, came in from across the sea. People called it “occupation”. – Soul of Japan being lost through this wave of American culture.

Provoke (1968-69):

Takuma Nakahira

Yutaka Takanashi

Koji Taki

Daido Moriyama

Daido Moriyama, Japan – A Photo Theatre

Eikoh Hosoe, Kamaitachi, 1969

0 notes

Text

From Ground Zero to Provoke: Trauma and Memory in postwar Japanese photography

The nuclear attack on Hiroshima, August 6th 1945

Atomic bomb attack on Nagasaki, August 9th 1945

How did photographers get across the situation that victims of these traumas found themselves in?

The concept of ‘collective trauma’ - Occurs when members of a collectivity feel they have been subjected to a horrendous event that leaves indelible marks upon their group consciousness, marking their memories forever and changing their future identity.

John Hersey, Hiroshima

Hiroshima, scene of A-Bomb Explosion, 1953

Authored rather than anonymous images – how specific photographers dealt with these events.

Yoshito Matsushige, Hiroshima, 6th august, 1945. Injured policeman issuing certificates to civilians.

Hiroshima, the shadow of someone obliterated by the blast. – Imprint of a person who was sat there when the bomb went off.

The images are metaphors for the events that occurred.

Amateur images that capture the immediacy of the aftermath of the bombings themselves.

Yosuke Yamahata, Nagasaki, August 10th 1945.

Gojira (Godzilla), Dir. Isihiro Honda, 1954 – Shannon Stevens – ‘The film performed a vital theraputic function for a society traumatized both by atomic bombings and by an oppressive regime that forbade all discussion of the trauma’

Retribution because of the nuclear bombings.

Ken Domon and Shomei Tomatsu, Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document, 1961

Shomei Tomatsu, Melted Bottle, from the series Nagasaki 11.02, 1961 – Embodiment Theory - how do we experience a photograph? Do we just experience it visually or are other senses stimulated by it?

Kikuji Kawada, Chizu – The Map, 1965

Alain Resnais, Hiroshima Mon Amour, 1989 (film) - Male character saying its unrepresentable unless you were there to witness the event. Superficial notion in comparison to someone who lived there and experienced it.

Miyako Isiuchi, Hiroshima, 2008.

Shomei Tomatsu:

Iwakuni, 1960

Yokosuka, 1959

Tokyo, 1960

Chewing Gum and Chocolate (2014) – culture, riding a mushroom cloud, came in from across the sea. People called it “occupation”. – Soul of Japan being lost through this wave of American culture.

Provoke (1968-69):

Takuma Nakahira

Yutaka Takanashi

Koji Taki

Daido Moriyama

Daido Moriyama, Japan – A Photo Theatre

Eikoh Hosoe, Kamaitachi, 1969

0 notes