#Yolmo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hello Grambank! A new typological database of 2,467 language varieties

Grambank has been many years in the making, and is now publically available!

The team coded 195 features for 2,467 language varieties, and made this data publically available as part of the Cross-Linguistic Linked Data-project (CLLD). They plan to continue to release new versions with new languages and features in the future.

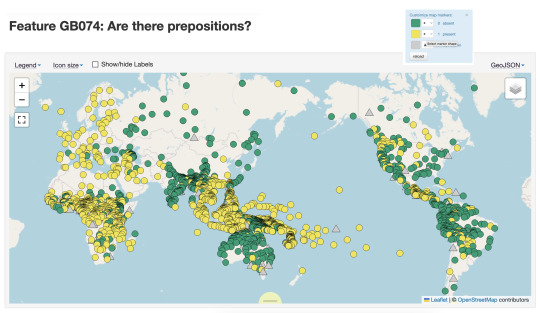

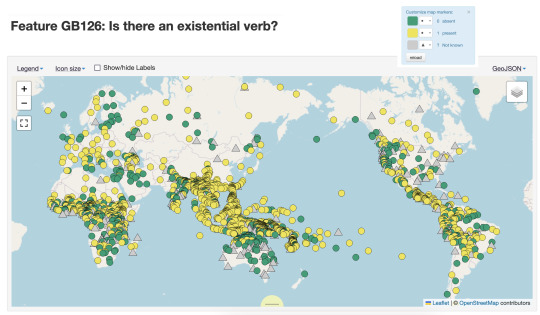

Below are maps for two features I’ve selected that show very different distribution across the world’s languages. The first map codes for whether there are prepositions (in yellow), and we can see really clear clustering of them in Europe, South East Asia and Africa. Languages without prepositions might have postpostions or use some other strategy. The second map shows languages with an existential verb (e.g. there *is* an existential verb, in yellow), we see a different distribution.

What makes Grambank particularly interesting as a user is that there is extensive public documentation of processes and terminology on a companion GitHub site. They also have been very systematic selecting values and coding for them for all the sources that they have. This is a different approach to that taken for the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures (WALS), which has been the go-to resource for the last two decades. In WALS a single author would collate information on a sample of languages for a feature they were interested in, while in Grambank a single coder would add information on all 195 features for a single grammar they were entering data for.

I’m very happy that Lamjung Yolmo is included in the set of languages in Grambank, with coding values taken from my 2016 grammar of the language. Thanks to the transparent approach to coding in this project, you can not only see the values that the coding team assigned, but the pages of the reference work that the information was sourced from.

433 notes

·

View notes

Text

Helambu Cultural Trek - 11 Days

Itinerary Detail Close All

Day 1 : Arrive in Kathmandu received by Team Himalaya staff.

On arrival meet our TH staff for a courtesy transfer to respective hotels in the heart of Kathmandu at the Thamel area, an interesting place for shopping and having meals in one of the many world-class restaurants, pubs, and bakeries. Our guide will inform you of details regarding the Helambu Cultural Trek.

Accomodation

Hotel

Day 2 : Drive to Sundarijal and trek to Chisapani 2,300 m – 04hrs.

Start this wonderful outdoor journey with a morning short drive towards the eastern Kathmandu valley rim at Sundarijal which is situated at a distance of 15 k.m. from Kathmandu city, from this small town at Sundarijal our trek begins with an uphill walk through a small farm village, a beautiful cascade of waterfalls and reaching an entrance of Shivapuri National Park, from here through a patch of forest and passing many scattered farm fields and villages then reaching the ridge top at Chisopani where the air gets cooler as this small village stands at 2,300 meters overlooking a grand panorama of snow-capped mountains from Annapurna-Manaslu-Ganesh Himal, Lang tang Himal towards Jugal Himal range, view of whole Kathmandu valley, this spot offers stunning sunrise and sunset views as well.

Food

Breakfast /lunch/dinner

Accomodation

Tea House

Elevation

2300

Day 3 : Trek to Gulbhanjyang 2,125 m – 05 hrs.

After an enjoyable morning with the sunrise over the grand mountain panorama, the walk starts with a downhill path to a nice village of Pati Bhanjyang which is a Hindu Brahman and Chhetris village, from here our walk carries on with a slow climb uphill for an hour then on the gradual winding through patch of forest and villages reaching at Gulbhanjyang for overnight stop after a good day’s walk of 4-5 hours.

Food

Breakfast /lunch/dinner

Accomodation

Tea House

Elevation

2125

Day 4 : Trek to Kutumsang 2,446 m – 04 hrs.

Today the walk is quite short, starting by following the trail with a climb uphill and sometimes downhill which leads to another popular village of Chipplin, from here walk continues through farm villages overlooking a grand panorama of surrounding green landscapes and rolling hills till the day ends at overnight stop in Kutumsang, a nice Sherpa-Yolmos and Tamang village with great views of snow capped mountains, afternoon free at leisure to explore this small pretty village surrounding.

Food

Breakfast /lunch/dinner

Accomodation

Tea House

Elevation

2446

Day 5 : Trek to Thadepati 3,597 m – 05 hrs.

From this nice village start the fresh morning walk with a climb north up to the Yurin Danda ridge through serene rhododendrons, pines, and oak forests and to a small pass at 3,510 meters and then with a short descent to the forested area.

Then this pleasant trek passes through the cool shade of rhododendron forests and comes to an open area, where there’s a Nepal army post and with few small teahouses, after this exposed place walk leads to a short climb diverting from the main path that joins to Gosainkund area, our wonderful walk completes at Tharepati for lunch and overnight stop. Tharepati with a few lodges and teahouses is the highest point of this trip offering grand panorama and awesome views of rolling landscapes and high stunning peaks of Langtang and Jugal Mountain range, afternoon free at leisure or for a short walk around this fabulous spot

Food

Breakfast /lunch/dinner

Accomodation

Tea House

Elevation

3597

Day 6 : Trek to Malemchigaon 2,560 m – 05 hrs.

After a wonderful time at the highest spot of this trek at Thadepati, our journey continues with a short climb to the top ridge, then heading downhill path through a dense forest of rhododendrons, hemlocks, firs, and pines tree lines.

The walk carries on further passing through several Sheppard’s huts and temporary settlements and then reaching Melamchi Khola ( stream), crossing the river, and then with a gentle climb reaching our overnight stop at Malemchigaon, a typical mountain and hill village of Buddhist religion inhabited with Yolmo’s and Tamang ethnic tribes, the houses windows and doors and furniture decorated with pretty intricate carvings, here after lunch free at leisure to explore this nice village.

Food

Breakfast /lunch/dinner

Accomodation

Tea House

Elevation

2560

Day 7 : Trek to Tarke Gyang 2,590 m – 04 hours.

Today another short day walk towards the main village of Helambu area at Tarke Gyang, he trails steeply descends to the Melamchi River from the village, then crosses the river by a suspension bridge, then the walk leads to a climb above the river for an hour reaching the overnight spot at Tarkeghyang village via Nakote village, Tarkegyang, renowned for its famed green apples and intricate Tibetan design wood carving on furniture and other products. Afternoon at leisure, visit this lovely village, where its windows and furniture have nice traditional carving, and visit the oldest Buddhist monastery, Ama Yangri on the top of the village.

Food

Breakfast /lunch/dinner

Accomodation

Tea House

Elevation

2590

Day 8 : Trek to Sermathang 2,610 m – 04 hours.

Slowly and gently as this wonderful journey comes to an end losing altitude day by day from here onwards on the downhill and flat land walking through beautiful forests and enjoying a visit to these villages of the Helembu area, our walk continues through many chortens and summer meadows to reach Gangyul a small village, then following the path with wonderful views of green rolling hills and natural vegetation and reaching at Shermathang for overnight stop, this is another pretty Hyalmo village of Helambu area, here with time to visit another old monastery.

Food

Breakfast /lunch/dinner

Accomodation

Tea House

Elevation

2610

Day 9 : Trek to Malemchipul Bazaar, drive to Kathmandu – 05 hrs drive

After a wonderful time in the high mountains walk ends after a few hours of trekking towards Melamchi Bazaar with a drive back to Kathmandu, the morning starts with an easy descent reaching a warmer area as the road leads to a lower area in the flat land till it reaches Dubachaur and walking further reaching a bridge over Melamchi Khola, and to busy Malemchipul Bazaar, with a short rest here after completing the walk of this memorable and impressive trek, and then an interesting drive of four hours reaches Kathmandu after a wonderful time in the high hills of Himalaya.

Food

Breakfast /lunch/dinner

Accomodation

Hotel

Day 10 : In Kathmandu full day sightseeing tour.

The morning after breakfast at a given time our city and cultural guide will guide you in and around Kathmandu at places of interest and importance, as Kathmandu Valley is full of World Heritage Sites the holy Pashupatinath temple, Bouddhanath (Little Tibet), Swayambhunath (Monkey Temple) & monasteries, ancient Kings Palaces and courtyard in Kathmandu; after an interesting sightseeing back to the hotel

Food

Breakfast

Accomodation

Hotel

Day 11 : International departure homeward bound.

Last day in Nepal with a wonderful memorable time in the Himalayas around Helambu Cultural Trek with Team Himalaya and transfer to the airport for the flight back home or to respective destination.

Food

Breakfast

Not Satisfied with this itinerary?

This represents our standard and highly recommended itinerary. Should this itinerary or date not align with your preferences, we are more than willing to tailor your vacation to meet your specific requirements. The following are our established departure dates. These dates and prices are applicable for joining a group. Allow our travel experts to assist you in personalizing this journey according to your individual interests.

Customize This Trip

What Is Included ?

Pickups and drops from hotels and airports.

3-night Tourist star hotel with Breakfast in Kathmandu.

Kathmandu To Sundari Jal, malemchipul to Kathmandu by local transport.

Kathmandu Valley sightseeing tour guide with private vehicle.

All meals during the trek. (BREAKFAST, LUNCH AND DINNERS).

All necessary paperwork, national park permits, and Tims card.

All our government taxes, VAT, and tourist service charges.

An experienced, knowledgeable, helpful, friendly, and English-speaking Trek guide and porter to carry Luggage. (2 trekkers 1 porter)

Food, drinks, accommodation, insurance, salary, equipment, transportation, and medicine all stuff.

Twins share comfortable and clean private rooms during the trek.

Down jacket and sleeping bag by team Himalaya (which need to be returned after the trek).

Trip achievement appreciation certificate.

Fresh fruit is seasonal during the trip.

Group medical supplies (first aid kit will be available)

Helambu cultural Trekmap.

Official expense.

Travel and rescue arrangement

What Is Excluded?

Lunch and dinner in Kathmandu.

Personal expenses (phone calls, laundry, bar bills, battery recharge, extra porter, bottle or boiled water, shower, etc)

International airfare to and from Kathmandu.

Kathmandu Valley Sightseeing tour entrance fees.

Travel and rescue insurance

Excess baggage charge

Extra night accommodation in Kathmandu because of early, late, and early return from the mountain (due to any reason) than scheduled.

Tips for trekking staff and drivers (tipping is expected ).

#expedition#nepalpeak#trekkinginnepal#hiking#trekking#nepalexpedition#teamhimalaya#tentpeakclimbing#climbing#tentpeakexpedtion#langtanghelmabutrek#langtangtrek#hellambutrekking#nepaltrek#nepal trekking

0 notes

Text

Helambu Circuit trek map and itinerary

The Helambu Circuit Trek explores various vividly green valleys, misty rhododendron woods, far-off vistas of snow-capped peaks, and the striking contrast of Tibetan Buddhist and Hindu civilizations.

The perfect short walk is the Helambu Circuit walk because the Helambu area is still mostly undeveloped. Here in Helembu, you may learn about Yolmo culture in high mountain villages, take in views of the deserted high mountains, and watch captivated as farmers toil in the fields with water buffalo teams and hand-made equipment.

For more details

Address- Z Street - Thamel, Kathmandu, Nepal

Phone- +977 1 4701233

Mobile, WhatsApp & Viber- +977 9849023179 (Dipak Pande)

Email- [email protected]

Website- www.mountainrocktreks.com

#HelambuTrek #HelambuCircuit #NepalTrekking #HimalayanAdventure

#MountainTrek #ExploreNepal #TrekkingInNepal #TravelNepal

#HimalayanExpedition #AdventureSeeker #OutdoorExploration

#HikingTrail #Thamel #Moonlighthotel #ramadaencore #hotelmoonlightthamel #paknajol #zstreet #mountainrocktreks #MRT2023

0 notes

Text

Romantic Lamahatta

Declared as an eco-tourism park in the year 2012, this is a stretched forest of conifers, pine and fir trees nestled in Kalimpong-Darjeeling highway, West Bengal. Lamahatta stands for ‘huts of Buddhist monks’. The Buddhist monks are called ‘Lama’ and ‘Hatta’ means hut. Hence, it is a hermitage of the Buddhist monks. This little mountain village has a history of inhabitation of the Buddhist monks for their prayer and meditation before independence. Now it’s an abode of mixed communities Sherpas, Bhutias, Tamangs, Yolmos and Dukpas. Being Buddhism as their common religion, Lamahatta is filled with monasteries and vibrant prayer flags fluttering with the cool breeze all around giving it an aesthetic look. Cattle rearing and farming are the main livelihood of these residents. Off late tourism has been included as the mainstream of earning.READ MORE...

0 notes

Text

TOC, Studies in Language Vol. 47, No. 1 (2023)

ICYMI: 2023. iii, 241 pp. Table of Contents Articles Concessive conditionals beyond Europe: A typological survey Tom Bossuyt pp. 1–31 Manner of motion in Estonian: A descriptive account of speed Piia Taremaa and Anetta Kopecka pp. 32–78 On the status of information structure markers: Evidence from North-Western Siberian languages Chris Lasse Däbritz pp. 79–119 The ‘general fact’ copula in Yolmo and the influence of Tamang Lauren Gawne and Thomas Owen-Smith pp. 120–134 Nominal reduplication in cr http://dlvr.it/SqMGsR

0 notes

Text

Gyalpo Lhosar: New Year Festival of Sherpa

The Tibetan New Year is celebrated during Gyalpo Lhosar. Losar starts on the first day of the first lunar month of the Tibetan calendar, which consists of twelve lunar months. On the 29th day of the calendar's 12th month, Lhosar festivities get underway. The terms Lo, which means year, and Sar, which means new, are the roots of the word Losar. The majority of the Sherpa, Tibetan, Tamang, Bhutia, and Yolmo people in Nepal celebrate Losar. The Tibetan New Year is celebrated exclusively on Gyalpo Losar. The following account is typical of Sherpa celebrations, although many villages in Nepal have their own interpretations.

The festival of Gyalpo Lhosar lasts for about two weeks. The first three days are when the biggest festivities occur. Chhaang is used to make the beverage changkol on the first day (a Tibetan cousin of beer). Day two is referred to as Gyalpo Lhosar. The major New Year's Day is today. They gather on the third day and feast. In the monasteries, a variety of ancient ceremonial dances that depict the conflict between god and the demon are performed. Fire torches are carried around the crowd while mantras are recited. A traditional dance portraying a conflict between a king and a deer is performed. There are prepared dishes. The soup is one of the most crucial dishes. Meat, wheat, rice, sweet potato, cheese, peas, green pepper, vermicelli noodles, and radish are the main ingredients in this soup.

On this day, Buddhist monasteries all over the world hold special prayers that channel the compassion and love of Buddha into the world. Monks also pray on this day for the universal brotherhood and equality that go hand in hand with world peace. When Buddhists visit monasteries, "Rinpoche" and senior family members bestow blessings upon them. The stories, myths, and legends are narrated through dance and song in the community's traditional dance ceremonies. Among these dances, a famous traditional dance tells the tale of a deer being saved by a king. The Tibetan year calendar is based on a 12-animal system, with the rat as the first animal and the boar as the last. The strength is displayed in this year because it is the year of the tiger.

Gyalpo Lhosar: Mythology & History

Legend has it that an elderly woman by the name of Belma established the concept of moon-based time measurement, which led to the first Losar celebration. The Nagas (the serpent deity), or water spirits, who energized the water element in the region, were offered gifts at the nearby spring as part of rites of thanksgiving. Smoke offerings were also provided to the local spirits connected to the natural world.

When PudeGungyal, the ninth monarch of Tibet, reigned, Gyalpo Losar has been observed as a spring celebration.

Gyalpo Lhosar: Activities & Celebration

Families come together to clean and decorate their homes the day before Losar. The customary greeting "TashiDelek" is exchanged that same night at midnight, and friends and family remain up late to wish each other a happy new year. Many Sherpa change their Dhoja, or prayer flags, in their homes the following morning to signify a new year. The day finishes with a special alcoholic beverage created from Chaang called Changkol (a Tibetan version of beer). People enjoy traditional Sherpa music while eating, drinking, and singing or dancing.

For two weeks, people celebrate Gyalpo Losar. The first three days are when the biggest festivities occur. A traditional beverage called Changkol, which is comparable to Chhaang, is consumed on the first day. Gyalpo Losar is observed on the second day, which marks the start of the New Year. People congregate for a feast on the third day. In the monasteries, a variety of ancient dances that depict the conflict between demon and god are performed. Holy candles are shared among everyone in the crowd as mantras are shouted. Also, a traditional dance that portrays a conflict between a deer and the King is performed. Fireworks are set off to drive away evil spirits. There are performances of traditional dances like Syabru.

What makes Gyalpo Lhosar unique?

Those that participate in this festival have a great time doing various things. They execute spiritual performances while wearing traditional clothing, singing and dancing in unison, playing musical instruments, eating and drinking a variety of homemade foods, and gathering. People go to the monasteries, chhortens, and stupas in the area. Certain ceremonial dances, which are based on the Tibetan lunar calendar, depict the struggle between Gods and Demons.

The Boudhanath Stupa in Kathmandu is illuminated and decorated for Gyalpo Lhosar, Nepal's New Year event. People start getting ready for Losar, a holiday that marks the start of the New Year, in February in Nepal, Tibet, and many neighboring Asian countries. The government of Nepal should place special focus on the celebration of its festivals, such as Lhosar, and protect and encourage their practice.

What does Ox Year celebrate?

Since it is the year of the ox, ox represents laborious effort. The ox is a representation of money, prosperity, hard work, and perseverance. A person born in the year of the ox is reputed to be strong, fair, dependable, patient, and deserving of trust. Up until this point, the ox years have been: 1901, 1913, 1925, 1937, 1949, 1961, 1973, 1985, 1997, 2009, and 2021.

UNESCO Cultural Heritage Sightseeing in Kathmandu

0 notes

Text

Langtang Valley Trek – 10 Days

Langtang Valley trek is one of those striking teahouses outdoors in the wild, with richly green flowing meadows. We view Himalayan peaks reaching the clouds and misty valleys hiding from discovery. This is Langtang as the curtains rise. Langtang valley trek has so much cultural wealth. We see this as we hike into the hearts of Sherpa and Yolmo villages

0 notes

Text

GOSAIKUNDA TREKKING IN NEPAL

The trial for Langtang- Gosainkunda trekking is found simply south to the Tibetan border. On the trekking you & get pleasure from crossing a high pass and trek for many days through dense forest and remote villages. Langtang, the mid-elevation region to the Park's south, could be a study centre of Tibetan Buddhism. Yolmo and Tamang folks maintain an expensive cultural heritage, evident in ornately carved wood windows, spirited dance festivals, and skilled weaving traditions makes Goshainkunda a lot of wonderful and exciting place to go to. Moderate to Rigorous trekking and lodging between 2000m (6,500ft) and 4,380m (14,366ft) with one pass crossing of 4,610m (15,120ft) and optional hiking to 5,100m

0 notes

Link

Field Notes is a new podcast about doing linguistic fieldwork, and the latest episode is an interview with @superlinguo. Description:

This week’s episode is with Lauren Gawne who does fieldwork in Nepal working with speakers of Yolmo and Syuba. Lauren has experience as both a successful grant applicant and as a grant committee assessor. In this episode, she shares her advice for navigating applying for funding in an overly-competitive and under-resourced environment. One of the essential points Lauren makes is that struggling to find funding doesn’t necessarily reflect on the quality of your work or your project, or your commitment to the community you’re working with. In this episode, Lauren shares how she has funded her work and her advice to researchers looking to apply for fieldwork funding. Also, read the instructions.

Read the full shownotes page and listen to the episode here.

#linguistics#podcasts#field notes#field notes podcast#interviews#linguistic fieldwork#linguistics podcasts#podcast#lauren gawne#funding#grants#grantwriting#superlinguo#fieldwork#nepal#yolmo#syuba

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Inside Milarepa's Cave

#pxpx500travel#cave#Milarepa#Nepal#Yolmo#shrine#butter#lamps#candles#meditation#retreat#rock#burning

0 notes

Text

Transcript Episode 76: Where language names come from and why they change

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘Where language names come from and why they change’. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Gretchen: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Gretchen McCulloch.

Gretchen: I’m Lauren Gawne. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about language names. But first, we’re doing another Lingthusiasm liveshow for 2023. The liveshow will once again be on the Lingthusiasm Patreon Discord, and it will be on the 18th or 19th of February, depending on your time zone.

Gretchen: We’re really excited to be returning to one of fan favourite topics and answering your questions about language and gender with a returning special guest, Dr. Kirby Conrod, who you may remember from the very popular episode about the grammar of “singular they.” We’re bringing them back for more informal discussion, which you can participate in. If you’re a Lingthusiasm patron, you can ask questions or share your examples and anecdotes about gender in various languages via Patreon or in the AMA questions channel on Discord. We might mention some of them in the episode. Or bring your questions and comments along to the liveshow itself.

Lauren: The Lingthusiasm Discord is available for all patrons at the Lingthusiast tier and above. You can join the Lingthusiasm Patreon by visiting lingthusiasm.com/patreon. That tier also allows you access to our monthly bonus episodes.

Gretchen: The Lingthusiasm liveshow is part of LingFest, which is a fringe festival-like program of independently organised online linguistics events running in February 2023.

Lauren: If you’re listening in the future and want to find out about these events as they’re happening, you can follow us on various social media @lingthusiasm. Our most recent bonus episode for patrons was outtakes and deleted scenes from some of the interviews we’ve done recently. If you wanna hear more from our guests – Kat Gupta, Lucy Maddox, and Randall Munroe – you can go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm to get access to that, a whole bunch of other bonus episodes, and our upcoming liveshow.

[Music]

Gretchen: There’s this really fun group activity that you sometimes see in linguistics classes or when linguists are hanging out which is collaboratively brainstorming all of the languages that people in the group can think of.

Lauren: Ooo, yeah.

Gretchen: Especially if you don’t allow Google or Wikipedia, it’s just which languages have you heard of or do you know at least a word or phrase in and can you put them on a whiteboard or in a notebook.

Lauren: Hmm, I’m already finding this a little bit complicated because I never know what name to give some of the languages that I know or know of or work with.

Gretchen: What’s an example of that?

Lauren: Okay. I wrote my PhD thesis about some parts of the grammar of a language called “Yolmo.” I worked with a variety that’s spoken in an area of Nepal called Lamjung, so that’s known as “Lamjung Yolmo.” The other variety is just called “Yolmo” because that’s where the Lamjung people migrated from. But it’s also known thanks to some savvy branding in the ’70s as “Helambu Sherpa.” It’s not related to the Sherpa near Everest at all, directly, but they wanted to get associated with the trekking tourism, so they took that name as an outside name for a while. That’s already, like, three names for what is really one language.

Gretchen: And you’ve also worked on a language called “Syuba.”

Lauren: Well, that’s true. But Syuba is actually closely related to these varieties of Yolmo. It’s spoken in an area called “Ramechhap,” but it’s not called “Ramechhap Yolmo.” They’ve only just returned to asking people to call them “Syuba.” Before, they were called “Kagate,” which is seen as a little bit of an unpleasant name. They don’t like it anymore. It’s like the Nepali word/name for them. Again, there’s two or three different possible names for this group of people who speak this particular language.

Gretchen: These are all names that’re used for them in English. Do they call themselves these names in the language itself?

Lauren: Syuba speakers call themselves “Syuba.” They’ve asked other people to. But actually, when you talk to people, and you’re talking about language, they just refer to it as “tam,” which is the word for “language.” In fact, it’s the word for “language” in a lot of different Tibetan varieties. A lot of people will just refer to what they speak as “tam” or “language.” Just another name to potentially throw in there.

Gretchen: I remember when I was first reading about the different language work that you were doing on your blog being like, “Wait, how many languages does this person speak?” because I think the language names were in the process of changing, and so it looked like you had written something about Kagate and also something about Syuba, but those were actually the same language.

Lauren: It’s a constantly evolving situation. I will always, always defer to the communities I work with as to what they wish to be called but also keeping track of this history is really interesting as you see the relationship between different groups of people evolve and change. We’re kind of at one or two languages, and I’ve already got six or eight names going on here. Our whiteboard is gonna get very complicated very quickly.

Gretchen: Well, that’s the interesting level of complexity because, like how humans sometimes have multiple names on different types of pieces of identification or at different periods of their lives, languages can also go through several different names. It’s even more complicated because there are generally multiple members of the community; sometimes they’ll have different opinions.

Lauren: Sometimes, those opinions are tied up with really interesting or really complicated or really difficult histories. We can’t just pin a single label to a group of people that speak a particular language.

Gretchen: Another thing that can make language-naming complicated is, depending on how one tries to draw the boundaries between, okay, these two communities are speaking the same language, they’re speaking varieties of one language, or they’re speaking languages that we’re gonna call “different,” which also factors into a lot of political- and community-level and linguistic decision making.

Lauren: We have a very Western perspective on what we think a group of people or a collection of language-speakers should be. There’s this really great paper that was recently published about language-naming practices in Indigenous Australia from Jill Vaughan, Ruth Singer, and Murray Garde. They looked at how the social attitudes towards language and ownership of language and relationships between peoples creates this really different approach to how to think about names of languages. In Australia, what is really important is the connection between language and a particular land and the geographic relationship that exists there, and therefore, who has the right to speak a language, who has the right to speak a language in a particular place or at a particular time, is a very different attitude to what we might have as, say, “I’m an English speaker. You can be an English speaker, too. We all speak English wherever we go.”

Gretchen: Both of us live in countries that have this history of colonisation where English isn’t originally tied to either of the lands that we’re occupying.

Lauren: The authors in this paper spend a lot of time talking through the example of “Bininj Kunwok,” which is a language from the northern part of Australia, which exists as a language name. It’s a language name people recognise. There’s a grammar and a dictionary. The name itself is, in these languages, the word for “person,” “bininj,” and “kunwok,” “speech,” so a bit like Yolmo with “tam” – similar elements coming into the language name there.

Gretchen: This is like, “the people’s language,” or something like that?

Lauren: Yeah. “The people who speak this language” kind of thing. People are very happy to use this term and come together as a group to work, say, on a dictionary project or some language materials, but actually, there’re many, many groups within that cluster of Bininj Kunwok that have their own name for their own variety of the language, who have names for all the other varieties, who don’t see themselves as necessarily speaking the same language because they’re not necessarily from the same part of the country. This creates this different relationship to where the language boundary is in the name compared to, say, English, where we see ourselves as all speaking just English.

Gretchen: So, this is sort of language name as a political alliance or federation of languages. I mean, actually, now that I’m saying this, I don’t know how dissimilar this is to using English to refer to all of the different varieties of English around the world in the sense that they have certain alliances when it comes to, especially, written material but also a lot of local differences on the ground that sometimes get erased by thinking of them all as having a common, standardised written form.

Lauren: Absolutely. I think the situation when we zoom in on any particular context is always more nuanced. This paper really goes into a lot of the context and the nuance of how we’ve come to have these language groups and these language names in Australia that can sometimes simplify a really complex social dynamic or a social history.

Gretchen: One of the other things I enjoyed about this paper was from the references portion at the beginning talking about how a language often gains wider public acknowledgement through “artefactualisation,” such as the creation of a dictionary or grammar, that makes for sort of a birth certificate of a language, as distinct from the language itself. Like, here it’s got its driver’s license. We’re using this driver’s license as a form of quote-unquote “neutral” ID to prove that a person exists when, actually, not all humans have equal access to documentation like driver’s licenses and birth certificates. There’re other things that a driver’s license, especially, signify in addition to being an ID marker. Not everyone can drive or is gonna be able to learn to drive or is physically able to drive. The idea that dictionaries and grammars get treated as evidence that a language exists, even when they have these very different relationships to different groups of language speakers or language signers, that’s a metaphor that carries through.

Lauren: Again, we’re trying to use language names as a way to pin things down, but when we actually zoom in, the situation is always a lot more nuanced. Just like we can get distracted sometimes by the fact that people share a name, not all languages that appear to have very similar names are necessarily part of the same family of languages. One that always tricked me up when I started working in Nepal is that we have “Nepali Bhasa” and “Nepal Bhasa.”

Gretchen: As someone who doesn’t know anything about Nepal, this really sounds very similar, yes. “Nepali Bhasa” and “Nepal Bhasa.”

Lauren: “Nepali Bhasa” is the Indo-Aryan language that’s the national language of Nepal. It’s very closely related to Hindi. “Nepal Bhasa” is the Newar languages that are the original languages of the Kathmandu Valley, so that’s the capital of Nepal.

Gretchen: So, they’re not part of this broader Indo-European language family that Hindi and Nepal belong to?

Lauren: No, they’re actually part of the Tibeto-Burman family. They’re part of a completely different family. They were in the Kathmandu Valley before the Indo-Aryan speakers came in to make it the capital of an even bigger country, which is what we now know as the country of Nepal today.

Gretchen: “Bhasa” sort of sounds like another language term, which is “Bhasa Indonesia,” the Indonesian language, or “Bahasa Malaya,” the Malay language.

Lauren: Yeah, that /basa/ or /bhasa/ is an old Sanskrit word for “language,” and so it pops up all over the place even for languages that aren’t related to each other.

Gretchen: This is great. I just learned a word that means “language” in a whole bunch of languages that’ve been influenced by Sanskrit.

Lauren: Yeah, we’re definitely collecting words for “language” in this episode as much as we’re collecting language names. It comes part and parcel with the territory.

Gretchen: This does tell us something about the relationships of these languages to each other which is, I guess, they were all influenced by Sanskrit at some level even if they have many other differences between them.

Lauren: Indeed.

Gretchen: Another group of languages with very similar names that have a shared history even if not necessarily a shared linguistic trajectory is the group of creole languages.

Lauren: Oh, yeah.

Gretchen: When I say, “creole,” what’s the first creole language that you think of?

Lauren: Um, “Kriol,” spelt K-R-I-O-L, which is a language of Australia, especially up across the Northern Territory in Western Australia, heading towards Bininj Kunwok country. It’s a creole of the English that came in but also from across the local languages around there, around the Roper River area, but it’s also spread to other parts of Australia as well. That’s the first creole that comes to mind for me. What about for you?

Gretchen: I think the first creole language that I think of is Haitian Creole, which is also often referred to just as “Kreyòl,” but in this case spelled K-R-E-Y-O-L with an accent on the O. This is the language of Haiti which is descended from French. It’s also spoken in the context of displacement and colonisation and having a bunch of people losing some connections with their linguistic roots, but they don’t have a common ancestor except insofar as English and French have a common ancestor. They just have this common history of being this contact language in terms of what “creole” refers to.

Lauren: I find it so fascinating that this word “creole” has this long history and in certain places has become attached to particular languages that arise in these situations. And in other places it refers to maybe the people or the food from the area. “Creole” pops up in a lot of places where you’ve seen French or English colonisation.

Gretchen: There’re also creoles that are extended to other languages that aren’t linked to colonisation. There’s Portuguese-based creoles, Dutch-based creoles, German-based creoles, Spanish-based creoles, Arabic-, Malay-based creoles. There’s a variety of places you could have a creole. Many of them, but not all of them, are linked to the Transatlantic slave trade and forced displacement of people from a location. You had a variety of people from different linguistic backgrounds mixing – not with their consent – and making this combination language with a language they had in common was the colonial language but also bringing in influences from their various mother tongues.

Lauren: Obviously, the Transatlantic slave trade wasn’t relevant to Australia, which is not near the Atlantic Ocean, but similar factors around displacement and the bringing in of English as a dominant language of trade and commerce in people’s lives. We also have Yumplatok in Australia, which is a creole language of the part of Northern Queensland that heads up into Papua New Guinea.

Gretchen: And Tok Pisin is another creole language – and English-derived creole – of Papua New Guinea, which isn’t referred to by the name of “Creole,” like many of them are.

Lauren: But the “tok” in both of those is from English “talk.” Once again, another-language-vibe name as part of the name of a language there.

Gretchen: Another language that came about because of contact and colonialisation with a bit of a different history is Michif or Metis in Canada, which arose from French fur traders marrying local Cree women. Their kids spoke this language that has a combination of French and Cree using Cree verbs, which are a really interesting and complex system that have lots of prefixes and suffixes. Cree is an Algonquian language, and this is characteristic of Algonquian languages. And then French nouns, which are also sort of the more complex bit of French grammar where French nouns have all of this grammatical gender going on. These kids decided to learn the most featurally rich bits of both of their parents’ languages.

Lauren: Amazing that these children made this language out of the complicated verbs and the complicated nouns. But it also has two names, you said, Metis or Michif.

Gretchen: Yeah. The name of this people and this language is Metis or Michif, which comes from a local pronunciation variant of the word “métis,” which is from a French word that means “mixed,” but it doesn’t refer to any type of linguistic mixing where you could have two parents from different language backgrounds. It refers to this particular mixing that happened in this particular historical context.

Lauren: That makes sense that the language name takes on this specific meaning and refers to this specific linguistic context.

Gretchen: I think with language names, sometimes something that comes up with a language name is its etymology, you know, “This comes from a particular language,” or “This comes from a particular meaning,” but also etymology isn’t destiny when it comes to language names.

Lauren: Yeah. I always find it really fun to say, “Ooo, this part of the language name comes from the word for ‘language’” or the word for “talk” or the word for “people.” But a language is so much more than the literal parts of its name.

Gretchen: I guess the other point is etymology is an interesting thing to learn about, but what’s important is respecting the wishes of the community that has that particular language. One of the things that I’ve been following is names of Bantu languages because a lot of them seem to come in pairs. Sometimes you see “Swahili” in a list. Sometimes you see “Kiswahili.” Sometimes you see “Zulu.” Sometimes you see “Isizulu.” Sometimes you see “Sotho” and “Sesotho” or “Tswana” and “Setswana.,” “Congo” and “Kikongo.” A lot of these language names seem to come in pairs like that where one of them has this prefix that’s something like /ki-/ or /si-/ or /t͡ʃi-/.

Lauren: I know that Setswana is spoken in Botswana, and Sesotho is spoken in Lesotho. They’re all connected somehow. This marking of something is a language by the use of a prefix is something that happens across these languages. They’re all part of the Bantu language family.

Gretchen: Right. And Bantu languages are known for having prefixes that mark lots of things. I dunno if it’s settled whether in English people are more likely to use the language prefix to refer to the language or not. It seems to sometimes vary per language. I mostly see people talking about “Kinyarwanda,” the language of Rwanda, which includes the prefix, but I also often hear people talking about “Zulu” rather than “Isizulu” without the prefix. I don’t know if there’s a consensus across different groups here, or if it’s something that varies more locally.

Lauren: I guess that just kind of works how an “-ish” or and “-ese” suffix works in English. We have “-ish” suffixes like “English” and “Danish” and “Irish.”

Gretchen: Yeah, or “-ese” suffixes like “Japanese,” “Cantonese,” “Portuguese.” These can also get applied to novel contexts to refer to the concept of a language in general – something like “Simlish,” the language of the Sims.

Lauren: Oh, yeah. Or “Legalese.”

Gretchen: Or “Journalese.”

Lauren: I guess there is an older tendency to refer to “Nepali” as “Nepalese” as a language. Now, you are more likely to see it written as “Nepali,” so taking their preference for the name as it’s pronounced closer to their own use of the name rather than this English suffixised form.

Gretchen: Sometimes the move closer towards how a community identifies themself happens at the morphological level where the suffix or the prefix changes as well.

Lauren: This distinction between what a group of people refer to their own language as and how a language is referred to by people outside of the group is often quite different as we’ve discussed with a few examples so far.

Gretchen: I think the first example that I learned of names for languages being really different in the language versus from other people who speak the language was in German, which in French, which I was learning very early, is “Allemand.” and then in German itself, is “Deutsch.” All three of these were really different from each other.

Lauren: In Italian it’s “Tedesco,” and in Polish it’s “Niemiecki.” These are all very different.

Gretchen: These are all very different. Something like “English” to “Anglais” in French, I was like, yeah, I sort of see how that happens. You hold it loosely and see how it’s similar. But “German” to “Deutsch” to Allemand” to –

Lauren: “Niemiecki” to “Tedesco.”

Gretchen: These all sound really different to each other.

Lauren: Part of this is that Germany as a country and German as a unified language is a relatively recent construction in Western and European history, so each of these groups were using names for whatever the German closest to them was and have kept those names as Germany unified.

Gretchen: Right. There’s different Germanic tribes or Germanic peoples that were referred to by different names in different areas. The broader name for this phenomenon of the name of a language inside its own group and outside of its own group is a contrast between the “endonym,” the name inside, and the “exonym,” the name from outside.

Lauren: The “-nym” part there being “name” and “endo-” and “exo-” being a contrasting pair.

Gretchen: Right. That’s “-nym” as in “pseudonym” or “synonym.”

Lauren: “Antonym.”

Gretchen: “Endonym” and “exonym” being themselves antonyms.

Lauren: Indeed. “Endo-” and “exo-” pop up in a whole variety of other places as well. We have “exoplanets” which are planets outside of our solar system.

Gretchen: Does this mean that planets inside our solar system are technically “endoplanets”?

Lauren: Hmm, maybe technically, yeah, just like we have “exoskeletons” like lobsters or Super Mecha Warriors.

Gretchen: Wait, so we could also have “endoskeletons,” which is what humans have which is a skeleton inside our body?

Lauren: Yeah, I’m gonna start referring to it as my “endoskeleton” now.

Gretchen: I think it’s funny because “endo-” and “exo-” are so clearly opposites. But “endo-” is familiar to me less from “endoplanets” and more from words like “endocrine system,” which is your hormones.

Lauren: Ah, I guess that is that “endo-”.

Gretchen: I looked up whether there is also an “exocrine system.”

Lauren: Is there?

Gretchen: Yeah. The endocrine system are the stuff that gets secreted inside your body and the exocrine system is all the stuff that you secrete outside your body, like sweat and saliva and mucus.

Lauren: I guess also in medicine we have “endoscopes,” which is when you use a camera in an orifice of your body to look at some internal part of your body.

Gretchen: This is like when you’d put a camera down your throat to look at your vocal cords.

Lauren: Yeah. I guess an “exoscope” is just any normal camera you take a selfie with because it’s looking at the outside of your body.

Gretchen: Great. I’m gonna refer to my normal camera as an “exoscope” now.

Lauren: An “endonym” is the name that we have in our own language for our language, and an “exonym” is the name that we have for a language of some other group of people.

Gretchen: To go back to the German example, “Deutsch” is the endonym, and then “Tedesco” and “Allemand” and “German” and “Niemiecki” are all exonyms for “German” coming from the perspective of various other languages.

Lauren: We’ve seen some recurring motifs already in terms of endonyms, people using words like “talk” or “language” or “people” for reference to their own language, but there’re also lots of different types of exonyms as well.

Gretchen: Sometimes, when a community wants to change the name of their language, that sometimes means replacing certain exonyms that other communities are using for their language with something that’s closer to the endonym of how they’re referring to themselves, which is especially important if this particular community hasn’t had a lot of self-determination in the first place. I don’t think I know any Germans who are like, “Yeah, no, English speakers need to refer to us as ‘Deutsch’,” but that’s a reflection of German social status, which is not the same if you’re from a language where there’s been this long history of colonisation.

Lauren: One type of exonym that can sometimes be easy to spot in the wild is when the name for the language as an exonym is very similar to their own endonym. For example, we call Italian, “Italian,” and in Italian it is “Italiano.”

Gretchen: Right, which is really similar. Sometimes, it’s just the languages don’t have quite the same sounds. The vowels in Italian are gonna be different from the vowels in English, and so “Italian” versus “Italiano” is produced with slightly different vowels even though the spelling is quite similar.

Lauren: These are cognate because it’s the same word just pronounced in each of the respective languages. Sometimes, these cognates can be a little bit more hidden.

Gretchen: Yeah. Like, “Tedesco” in Italian is actually from the same origin as the German word “Deutsch.” It also gives us the English “Teutonic.”

Lauren: Ah, right.

Gretchen: It’s just that those words ended up with diverging trajectories in those languages. One place where you have a lot of adaptation for pronunciation differences is if the languages have different modalities. If you have a sign language, and you wanna refer to it in a spoken language, you need a spoken name to refer to it and vice versa, you need a signed name to refer to a spoken language.

Lauren: I think this is why a lot of signed languages end up having acronym-type names, so “American Sign Language,” “ASL,” “British Sign Language,” “BSL,” because there isn’t a direct way to take the cognate from the signed language into the spoken language.

Gretchen: Actually, that raises a question for me which is “Auslan” which has, I think, a relatively straightforward etymology, “Australia” and “language,” but it doesn’t have that acronymic thing. I guess it would just be “ASL” for “Australian Sign Language” which would be confusing. Do you know how that came about?

Lauren: In the 1970s and ’80s when Trevor Johnston started working on Auslan, it already had a name in Auslan. It has its own sign. But Trevor Johnston needed a way to refer to it in English as well. He actually took inspiration from what was happening in America at the time, which is that what we now know as ASL was also being quite commonly referred to as “Ameslan” – so a blend instead of an acronym.

Gretchen: Of like, “American Sign Language” – oh, the S there is for “sign.” “Ameslan.” Okay.

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: So, the S in “Auslan” is also for “sign” rather than “Aus” as in “Australia.

Lauren: It’s a bit of both. And I think that’s why it’s really stood the test of time because it really has a very word feel. As you said, it also would have to compete with “ASL” for recognition in that three-letter acronym approach. “Auslan” has stood the test of time in a way that “Ameslan” hasn’t.

Gretchen: That’s interesting. I think that when I think of other linguistic varieties that have acronymic names, I think of accents and dialects and varieties that’ve been named in the last, maybe, century or so.

Lauren: Acronym-ing is a very 20th Century approach, for sure.

Gretchen: 20th and 21st, I guess. Things like “MLE,” “Multicultural London English,” or “RP,” “Received Pronunciation,” or “AAVE,” “AAE,” “AAL,” which is “African American Vernacular English,” “African American English,” “African American Language,” depending on how you wanna name it – these are all very acronymic names for things that have been named comparatively recently, whereas some of the older English varieties, I’m thinking things like “Cockney,” which is associated with the working class in London’s East End, or like “Scouse” in Liverpool, these have names that aren’t acronymic. These are varieties that have been named for a longer period of time.

Lauren: It’s interesting how the way that we talk about different languages and different varieties reflects larger trends in approaches to naming things.

Gretchen: Another way that language names can come about is by doing a more direct or a partial translation of the name for the language in the language. An example of this is “Light Walpiri,” which is a mixed language of Australia that has Indigenous Walpiri language, Kriol, and Standard Australian English as its parent languages. The name “Light Walpiri,” which I’d encountered in a few contexts because it made some news when the linguist named Carmel O’Shannessy was documenting it initially, I was interested to read in one of the papers that the name comes from “Walpiri rampaku,” which literally means in Walpiri “light Walpiri.” She as a linguist decided to translate part of the name into English while keeping the connection with how people were referring to it in the language – or possibly speakers were doing that, but it has this connection to how people were talking about it without being a direct reflection of it.

Lauren: So, that exonym that is the way that I know the language is a direct translation of their endonym for it within Walpiri. Interesting. I never knew the history of “Light Walpiri.”

Gretchen: I was wondering why “light,” and that seems to be why.

Lauren: Sometimes, the exonym that we use in one language was borrowed as the exonym from another language. So, we didn’t borrow someone’s endonym or own way of talking about their language, we borrowed it from, maybe, their neighbours.

Gretchen: This is really common in the North American Indigenous context. There are loads and loads of examples. One of them is the name “Navajo,” which comes from a Tewa word, which is another Indigenous language spoken nearby, “navahu,” which combines the word “nava,” meaning field, and “hu,” meaning “valley,” to mean “large field.” It was borrowed from Tewa into Spanish to refer to a particular place, and then later into English for the people and their language. But the name that the people themselves use is Diné, which also means “people,” with the language known as “Diné bizaad” or “people’s language,” or sometimes “Naabeehó bizaad,” but “Naabeehó” is this adaptation of the word “Navajo” because there’s not actually any V in Diné.

Lauren: Always a bit of giveaway when the exonym has sounds in it that don’t exist in the language it’s referring to.

Gretchen: Really big one. In this case, “field” and “valley,” that’s got a relatively neutral valence. It’s not the name in their own language, but it’s not a particularly bad thing to be people in a field or a valley. But a lot of these names from neighbours are sometimes pretty pejorative.

Lauren: That is definitely a large theme in exonyms, especially when it’s not the group itself that got to determine how they were referred to by outsiders. It’s part of why Kagate speakers moved to calling themselves “Syuba” even though both of those names refer to their previous occupation as paper-makers, which was seen as not a very aspirational career in the social hierarchy of Nepal. They’ve taken a lot more pride in their own word for that name rather than for the Nepali word which has more immediate negative connotations for Nepali speakers. It took me a long time to make the connection between the Slavic language family and the word that we have from originally Greek and then Latin into modern languages as “slave.” These two words are actually cognate with each other.

Gretchen: Oh boy. Okay. Is there a sense of which one arouse first?

Lauren: I felt like I got conflicting and slightly-confusing-and-lost-to-history stories depending on the etymological dictionary I looked up but definitely seemed to be pretty cognate, and it says something about the social status of speakers of those languages within, definitely, the Roman Empire.

Gretchen: That’s for sure a thing. This is also really common when it comes to Indigenous languages that a lot of their names are pejoratives. I’m not necessarily sure that I wanna repeat a whole bunch of pejoratives of what the names are. People are trying to bury them. I think my go-to example that’s comparatively a relatively mild pejorative is the name “Maliseet,” which is a language spoken around Eastern Canada and North-Eastern United States, also sometimes called “Passamaquoddy.” I grew up with that just being the name for the language, but then I learned later that this actually comes from a name by the Mi’kmaq people, who are another Indigenous group that’s slightly further east in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island and around there, who were encountered by Europeans slightly earlier. They were asked, “Who lives over there?”, and gave the name “Maliseet,” which means, “They speak slowly.”

Lauren: Charming.

Gretchen: Sort of makes some sense when you think of, they speak related languages, maybe if they’re talking to each other, they’re trying to come to some understanding and speak slowly to each other. But it’s not super flattering, and it’s a word that people have understandably been moving away from in more recent years.

Lauren: I mean, I only know it as “Passamaquoddy,” so it’s an indication that the exonym that’s now in use is the one that the Passamaquoddy actually prefer.

Gretchen: There’s another exonym which I, unfortunately, haven’t been able to find a good pronunciation guide of online that begins with a W and translates as meaning, “people of the bright river” or “of the shining river.” There’s still several different endonyms that this is under discussion for, but this is one case of very, very many, some of which are much more insulting.

Lauren: It gives you a sense of the history of power dynamics in general.

Gretchen: There’s an interesting case of miscommunication when it comes to the Mi’kmaq language itself because this was a case where a First Nations people and European people were encountering each other mutually for the first time in what’s now Eastern Canada. The name “Mi’kmaq” is an exonym which literally means in Mi’kmaq “my friends and family” or “my kin friends,” so it implicitly in the answer to “Who lives around here?”, well, it’s like, “My friends and family live around here.”

Lauren: Wonderfully literal.

Gretchen: Yeah. I mean, which, fair enough, really. The endonym is “Lnu,” “Lnu’i’sit,” “the people’s language.” But since the exonym isn’t insulting and the endonym sounds a lot like a related Indigenous language that’s spoken a little further north, “Inu,” at the moment, the exonym is still in use in English because it’s still a word in the language and has this history. Conversely, the name in Mi’kmaq for “French,” the French people and the French language, is “Wenju” or “Wenjuwi’sit,” which is “He or she speaks French,” which literally translates to something like, “Who are they?”

Lauren: That is amazing. So, these French people turned up, and they’re like, “Who are they?”

Gretchen: Basically, yeah. It’s got this sort of interestingly mutual miscommunication, whereas the Mi’kmaq word for “English” is “Agase’wit,” “He or she speaks English,” which is clearly borrowed from French, so you can see the contact via French. But when it comes to the paired miscommunication, I find it an interesting story of contact.

Lauren: I always find power dynamics are really interesting for who is centred as the default speaker or what is centred as the default language.

Gretchen: When it comes to the colonial context those languages are often named after the country they were originally spoken in. But I was at a conference a while back, and I met a linguist from Brazil and said, “Oh, you speak Portuguese,” and he said, “Well, you know, I like to call it ‘European Brazilian’.”

Lauren: That’s amazing. Especially considering there are far more Brazilian speakers of Portuguese than there are those in Europe who speak Portuguese.

Gretchen: Yeah. And it sort of raises the question of could you generalise this in other contexts.

Lauren: Do you think that maybe I should start telling people that in the UK they speak “protipodean” Australian?

Gretchen: Oh god, it’s like “antipodean” but “protipodean” Australian. You know what? I’ll buy it.

Lauren: I’m gonna start trying to get grants to document protipodean Australian so we can go back and hang out with people in the UK.

Gretchen: I look forward to seeing the Reviewer 2 comments on that application, thank you.

Lauren: Maybe at some point in the future, languages like Brazilian Portuguese will find new ways of talking about themselves or asking to be referred to. Jokes aside, language names are in flux, and they tell us a lot about history, but they’re not set in stone. We can change the way we refer to languages.

Gretchen: Right. Linguists have this responsibility, if someone’s in charge of making the types of documentation that make a language visible to bureaucratic infrastructure to be very thoughtful in talking with multiple people about how that language name is decided.

Lauren: I think we all have a responsibility to keep in mind that language names can change and can have complicated histories. The thing we can do is always respect the choices of the people who speak those languages when it comes to the names they’re given.

[Music]

Lauren: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, SoundCloud, YouTube, or wherever else you get your podcasts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr. You can get IPA scarves, “Not Judging Your Grammar” stickers, and aesthetic IPA posters, and other Lingthusiasm merch at lingthusiasm.com/merch. I tweet and blog as Superlinguo.

Lauren: I can be found as @GretchenAMcC on Twitter, my blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com, and my book about internet language is called Because Internet. Have you listened to all the Lingthusiasm episodes, and you wish there were more? You can get access to an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month plus our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now at patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Have you gotten really into linguistics, and you wish you had more people to talk with about it? Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk with other linguistics fans. Plus, all patrons help keep the show ad-free. Recent bonus topics include outtakes from our interviews with Randall Munroe, Kat Gupta, and Lucy Maddox, an episode about stylised ye-olde-time-y English, and children learning languages. Plus, on February 18th or 19th, 2023, depending on your time zone, you can join us for a patron-exclusive liveshow featuring special guest, Dr. Kirby Conrod, to talk about language and gender. Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Gretchen: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, and our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Lauren: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#linguistics#language#lingthusiasm#episode 76#language names#transcripts#names#Arnhem Land#Yolmo#Creole#Kriol#Métis#Michif#Bantu#Swahili#endonym#exonym#Maliseet#Walpiri#Light Walpiri#Din��#Navajo#Slavic#German

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 years of a PhD

August 2023 marks ten years since I was awarded a PhD in Linguistics. I submitted the thesis for examination in February 2013, it was examined by around May, and the final version with corrections done by some time in the middle of the year. August is when I dressed up and the degree was conferred, so that's the date on the testamur that now hangs in my office. The weirdest thing about this decade is that it means I've spent longer having a PhD than doing something that was such an important time in my life. My work has continued to grow from, but still draw on, my thesis research. I have been working with speakers of Syuba as well as Lamjung Yolmo, to continue to document this language family. I've moved from a focus on evidentiality to look at reported speech, discourse and gesture. These all still require an approach that looks at both grammatical structures and how people use them, directly continuing the kind of approach I took in my PhD. I'm particularly proud of the gesture work, as this is a return to an older interest. I didn't publish my PhD as a single monograph, but turned it into a number of revised and refined papers. I publishing the descriptive grammar as a book, which was an expanded version of a slightly absurd 30k word appendix to the thesis. Below is a list of those publications, as you can see it took me quite a few years to find homes for all of this work. I've also been lucky to take my research in other directions too; my gesture work has expanded into emoji and emblems, and I've also been writing about the data management and lingcomm work I've been doing. This work has increasingly been happening with collaborators, I love how much better work becomes when people talk each other into do their best thinking. I know I'm very fortunate to still be researching and teaching a decade after graduating, and that I have an ongoing job that lets me plan for the next decade. The thesis work informed a lot of my research, but these are the publications taken directly from the thesis:

Gawne, L. 2016. A sketch grammar of Lamjung Yolmo. Asia-Pacific Linguistics. [PDF] [blog summary]

Gawne, L. Looks like a duck, quacks like a hand: Tools for eliciting evidential and epistemic distinctions, with examples from Lamjung Yolmo (Tibetic, Nepal). 2020. Folia Linguistica, 54(2): 343-369. [Open access version][published version][blog summary]

Gawne, L. Questions and answers in Lamjung Yolmo Questions and answers in Lamjung Yolmo. 2016. Journal of Pragmatics 101: 31-53. [abstract] [blog summary]

Gawne, L. 2015. The reported speech evidential particle in Lamjung Yolmo. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 38(2): 292-318. [abstract][pre-publication PDF]

Evidentiality in Lamjung Yolmo. 2014. Journal of the South East Asian Linguistics Society, 7: 76-96. [Open Access PDF]

A list of all publications is available on my website: https://laurengawne.com/publications/

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sarangi Lyrics – Yankee Yolmo

Sarangi Lyrics – Yankee Yolmo

Presenting the Lyrics of the Nepali song “ Sarangi ” sung by Yankee Yolmo, Music Given by Mall Road Studios. And song written by Pranay Lama Yolmo. Bookmark our website for more daily latest released songs lyrics updates https://getbestlyrics.com/nepali/ Song Details Song: SarangiSinger: Yankee YolmoLyrics: Pranay Lama YolmoMusic: Mall Road Studios Song Lyrics Sarangi Ko Dhunai…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In order to access other realities, people in different cultures and religions across the world use very similar methods, and they are used by spiritual specialists, spiritual seekers, whether or not they have any particular religious belief, and even by the merely curious. One or all of the senses might be involved: visual signs and symbols might be employed, as well as voice and musical instruments, dance or body postures with accompanying body decoration of some sort, physical pain, and olfactory and tactile stimuli. Sometimes hallucinogenic substances are used.

As part of his fieldwork in Nepal among the Tibetan Buddhist Yolmo Sherpa people, anthropologist Robert Desjarlais became an apprentice to a healer, Meme, and with Meme’s help, began his own forays into trance experiences:

Taking the role of shamanic initiate, I would sit in a semi lotus position to the right of my “guru” and attempt to follow the curing chants. In time, Meme would begin to feel the presence of the divine, his body oscillating in fits and tremors, and my body, following the rhythm of his actions, would similarly “shake.” Tracked by the driving, insistent beat of the shaman’s drum, my body would fill with energy. Music resonated within me, building to a crescendo, charging my body and the room with impacted meaning. Waves of tremors coursed through my limbs. Sparks flew, colors expanded, the room came alive with voices, fire, laughter, darkness.

After several months of learning how to use his body in a similar way to the people he was studying, taking note of their ways of approaching sounds and smells, ways of talking, walking, and sensing, over time his trance experiences slowly began to be more comparable to those that his teacher experienced. The more experience he gained of trance, the more controlled, centered, and steady were the visions he was having, and he realized that it is possible to expand one’s “field of awareness” to a much greater extent.

[...]

An Oglala Sioux man cited by Thomas Lewis commented on his experience while participating in the Sun Dance, a ceremony calling on the power and healing properties of the sun, which is performed among many indigenous people of the Plains in North America:

The experience of the Sun Dance I can’t describe. It’s like being hypnotized. As I go up and down it’s as if the sun were dancing. It is a good feeling. It is all preparation, planning, fasting, being ready. It is not easy. My throat is dry and I am tired. I don’t sleep before; I cannot sleep. I am thinking and planning how it will be. There is sacrifice, pain, death and dying, and coming back again to the real world.

Fasting and purification before an actual dance might last from 48 hours to four days, and extreme forms of the dance might include self-torturous inflictions of pain on the physical body of the dancer: piercing, the insertion of skewers into the flesh before being tied to a rope that is hanging from a central pole. The dancer might continue the dance until the skewers are torn free. The ultimate goal of a Sun Dance is the religious experience of a vision. It is also an empowering experience for the dancer, who gains some understanding of the complementarity of life and death, and that suffering is a part of life; it also helps the dancer to cope with the realities of everyday life.

If the dancer receives a vision during the several days of the Sun Dance activities, his spirit might leave his body, and converse with one or more other spirits, receive power, and be instructed by them about how to use that power. A dancer might channel his power during prayer and dance in order to help sick relatives or friends. For both participants and spectators, the Sun Dance, especially in its extreme forms, is “a powerful emotional and spiritual experience,” replete with electrifying energy within a highly charged setting.

-- Lynne L. Hume & Nevill Drury, The Varieties of Magical Experience

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Kagyu Golden Rosary - Palchen Chokyi Dhondrup Chökyi Dhöndrup was born to a Nepalese family in Yolmo (Helambu), in the Kingdom of Nepal. The Eleventh Karmapa Yeshe Dorje sent an envoy with precise instructions on how to find this boy. With the permission of his parents, he was taken to Tibet at the age of seven, and enthroned by the Karmapa as the eighth Shamar incarnation. He received the full transmission of the lineage from the Karmapa and he also studied with the third Treho Tendzin Dhargye, Goshir Dhönyö Nyingpo and other masters. He traveled to China and Nepal and benefited many beings through his teachings. He passed away at the age of thirty eight, in the Water Mouse year. He passed on the full Kagyu lineage to the Twelfth Karmapa, Changchup Dorje. source: https://ift.tt/2vwH2Zj

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOC, Studies in Language Vol. 47, No. 1 (2023)

2023. iii, 241 pp. Table of Contents Articles Concessive conditionals beyond Europe: A typological survey Tom Bossuyt pp. 1–31 Manner of motion in Estonian: A descriptive account of speed Piia Taremaa and Anetta Kopecka pp. 32–78 On the status of information structure markers: Evidence from North-Western Siberian languages Chris Lasse Däbritz pp. 79–119 The ‘general fact’ copula in Yolmo and the influence of Tamang Lauren Gawne and Thomas Owen-Smith pp. 120–134 Nominal reduplication in cr http://dlvr.it/SqJC7j

0 notes