#Xiaowen of Northern Wei

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It is tempting to compare Charlemagne to Xiaowen, who, three centuries before, had moved the Northern Wei kingdom on China's rough frontier toward the high end, jump-starting the process that led to the reunification of the Eastern core.

"Why the West Rules – For Now: The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future" - Ian Morris

#book quote#why the west rules – for now#ian morris#nonfiction#tempting#charlemagne#xiaowen#parallels#comparison#northern wei#chinese history#china#jumpstart#reunification#the east

1 note

·

View note

Text

Longmen Grottoes; Luoyang in Henan Province, China. Earliest history of Longmen Grottoes is traced to reign of Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei dynasty; period from 493-1127 AD.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

WS29.2.1, Biography of Shusun Jun

(His clan name was actually Yizhan. The Yizhan clan changed their clan name to Shusun during the Sinicisation reforms of Emperor Xiaowen. Also, providing some context and explanation for the Northern Wei practice of encouraging the suicides of officials' widows which started with him)

Biography

[Yizhan Jian]'s eldest son was Jun, courtesy name Chougui, [he was] intelligent at a young age. At the age of fifteen, attended the imperial palace as a retainer. Had a cautious and calm character, and did not exceed his capabilities. In order to be a horse mount archer, was transferred as a hunting official [1].

長子俊,字醜歸,少聰敏。年十五,內侍左右。性謹密,初無過行。以便弓馬,轉為獵郎.

Emperor Taizu [posthumous name Emperor Daowu, personal name Tuoba Gui] died, the Prince of Qinghe, Shao, shut the palace gates [2], and Taizong [posthumous name Emperor Mingyuan, personal name Tuoba Si] was outside [3]. Shao forced Jun to act to assist him. Although Jun on the outside submitted to Shao, on the inside he had true loyalty, therefore with Yuan [4] Mohan and others criticised Shao, pledging allegiance to Taizong. This affair is in the biography of Mohan.

太祖崩,清河王紹���宮門,太宗在外。紹逼俊以為己援。俊��雖從紹,內實忠款,仍與元磨渾等說紹,得歸太宗。事在磨渾傳。

At this time of Taizong's retainers, only Che [5] Lutou, Wang Luo'er and others, were able to reach Jun and others' [assistance], [Taizong] was very pleased [with him], [Jun] acted as an attendant.

是時太宗左右,唯車路頭、王洛兒等,及得俊等,大悅,以為爪牙。

When Taizong succeeded to the throne, ordered that Jun, Mohan and others correct the errors of the retainers. Was transferred as a guard general and bestowed as Duke of Ancheng.

太宗即位,命俊與磨渾等拾遺左右。遷衞將軍,賜爵安城公。

The Prince of Zhuti, Yue, carried a knife in his bosom and entered within the imperial residence, to goad a major rebellion. Jun realised Yue's actions were unusual, and easily held his hand and pulled it back, thus within Yue's bosom there were two daggers, [Yue] was thereupon executed.

太宗即位,命俊與磨渾等拾遺左右。遷衞將軍,賜爵安城公。朱提王悅懷刃入禁中,將為大逆。俊覺悅舉動有異,便引手掣之,乃於悅懷中得兩刃匕首,遂殺之。

Taizong grasped Jun's significant merits from beginning to end, the policies of military affairs and civil administration were all according to his appointment, many officials starting their posts were earlier by Jun selected and inspected, and after that were presented and confirmed.

太宗以俊前後功重,軍國大計一以委之,群官上事,先由俊銓校,然後奏聞。

[Jun] had a just, fair and gentle character, and his form was not likely to be easily angered. [He was] loyal, devoted and genuine, and did not flatter his superiors or repress his subordinates. Every time he received an imperial edict and announced it to the outside, he would certainly announce [it] politely, the receivers would all be fulfilled and retreat, and those with confidential matters would turn away and arrive at the torch [6] again. Therefore his superiors and subordinates admired and praised him.

性平正柔和,未嘗有喜怒之色。忠篤愛厚,不諂上抑下。每奉詔宣外,必告示殷勤,受事者皆飽之而退,事密者倍至蒸仍。是以上下嘉歎。

Died in the first year of Taichang [416 CE], was twenty-eight [7] at the time, Taizong was excessively anguished and mournful, went in person and was deeply aggrieved. In all levels of society, there was no lacking in their pursuit of pity. Bestowed as Palace Attendant, Minister of Land and Water and Prince of Ancheng [8], with the posthumous name of Filial and Fundamental [xiaoyuan].

泰常元年卒,時年二十八,太宗甚痛悼之,親臨哀慟。朝野無不追惜。贈侍中、司空、安城王,諡孝元。

Was bestowed warm and bright rare utensils, carried using a sleeping carriage, guarded by soldiers leading their followers, and was buried [with other important people, including the imperial family] in the Jin Mausoleum. His son Pu inherited his rank. After [this], when esteemed ministers with great merit and special favour died, the rites with which they were paid their last respects were all according to the tradition of Jun's [9], but did not surpass that.

子蒲,襲爵。後有大功及寵幸貴臣薨,賻送終禮,皆依俊故事,無得踰之者.

[As a part of this], when Jun died, Taizong advised his wife Lady Huan [10] and said:

"When people in life share glory, in death it is appropriate to share a tomb. The capacity for [you] to be buried with the dead may be an undertaking of [your] desire." [11]

Lady Huan thus hanged herself and died, and was thereupon jointly interred there.

初,俊既卒,太宗命其妻桓氏曰:「夫生既共榮,沒宜同穴,能殉葬者可任意。」桓氏乃縊而死,遂合葬焉。

Northern Wei emperors and princes would often go on hunts with their attendants. I presume that Yizhan Jun would attend the emperor or a prince's hunting trip.

2. Tuoba Shao had assassinated Tuoba Gui.

3. Tuoba Si had earlier fled the capital of Pingcheng to avoid his father's wrath.

4. Should be Tuoba Mohan, as the imperial clan name of Tuoba was changed to Yuan by Emperor Xiaowen.

5. Should be Chekun Lutou, as the Chekun clan shortened their clan name under the reforms of Emperor Xiaowen.

6. I presume that 蒸 refers to a type of torch in this context. Torches would be lit as a signal during this time.

7. By East Asian age reckoning, in which a person is considered 1 year old at birth and becomes a year older at New Year, regardless of individual birthday. By Western age reckoning, he would be 26 or 27 years old.

8. He received the title of Duke of Ancheng in his lifetime; he was posthumously promoted to the rank of prince.

9. This likely refers to the death of the wives of these officials, which is outlined in the section below this statement.

10. Should be Lady Wuwan, as the Wuwan clan changed their clan name to Huan under the reforms of Emperor Xiaowen.

11. The Zizhi Tongjian phrases this differently, stating: "In life you shared honour with him [Yizhan Jun], will you share his sadness in death?" The History of the Northern Dynasties records an identical phrase to the Book of Wei, so Sima Guang likely paraphrased the earlier phrase in his record. The outcome was the same.

The Northern Wei practice

The death of Yizhan Jun started a practice in which the wives of powerful and favoured officials would be encouraged into committing suicide upon the official's death. This was first hinted using the euphemism "buried according to the rites of Shusun Jun".

(Technically, Tuoba Si had earlier poisoned Wang Luo'er's wife, but this was an irregular case. All other women to die to this practice were encouraged to commit suicide, yet she was poisoned, and the Weishu dates this practice to Shusun Jun, not Wang Luo'er. Wang Luo'er's wife may have been poisoned for a different reason)

This practice started with Tuoba Si and Yizhan Jun, but it continued into his son Tuoba Tao's reign. Tuoba Tao later buried his official Lu (Tufulu) Luyuan with the rites of Yizhan Jun, indicating this practice. Tufulu Luyuan's rites were even greater, so from then on, this practice was euphemised as "buried according to the rites of Lu Luyuan", which should indicate this practice, as Lu Luyuan was buried with this practice.

I think that although Tuoba Si claimed burial etiquette as his reasoning, the actual reasoning was probably to prevent other powerful tribes from coming to power the same way the Tuobas themselves did - using their maternal connections.

Tuoba Gui used his connections to the Helan and Murong tribes to claim power for himself. Later, Tuoba Shao's attempted seizure of power likely relied on his maternal tribe, the Helan tribe, making two incidents where this method of gaining power was attempted. Tuoba Gui created 子贵母死, and Tuoba Si this policy, to prevent others from using this method of gaining power.

Though the Tuoba clan did not restrict the greater freedom of common women, they restricted the women in elite classes, who they saw as being a threat to their power. Due to their knowledge that they only came to power with the help of maternal connections, they became fearful of these connections being exploited.

It is for this reason that the practice continued after the death of Tuoba Si, and continued to as far as Empress Dowager Feng's regency over Emperor Xiaowen. The practice was likely abolished during the sinicisation reforms of Emperor Xiaowen.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Relocation of Barbarians[1]

Jiang Tong (? – 310)

The Yi, Man, Rong, and Di, collectively known as the Four Barbarians, were traditionally confined to the outermost regions of the Nine Provinces. The Spring and Autumn Annals decree that the Chinese should be embraced within, while the barbarians are to be kept without. This distinction arises from their unintelligible speech, disparate forms of tribute, alien customs, and divergent lineages. Some dwell beyond the farthest reaches of civilization, across mountains and rivers, in treacherous valleys and perilous terrain, separated from the Middle Kingdom by natural barriers. They neither encroach upon our lands nor fall under our jurisdiction. Neither taxes nor the imperial calendar extend to their domains. Thus, it is said, "When the Son of Heaven governs in accordance with the Way, the Four Barbarians guard the frontiers."

When Yu brought order to the Nine Regions, even the Western Rong paid homage. Yet the nature of these barbarians is avaricious and ruthless, with the Rong and Di being the most savage among them. When weak, they cower in submission; when strong, they rebel and invade. Even in ages blessed with sage rulers and sovereigns of great virtue, none have succeeded in fully civilizing or guiding them through benevolence and moral suasion.

In times of their ascendancy, even Gaozong of Yin[2] was vexed by the Guifang,[3] King Wen of Zhou was troubled by the Kunyi and Xianyun,[4] Gaozu was besieged at Baideng,[5] and Xiaowen[6] was forced to take up arms at Bashang. Conversely, during their decline, the Duke of Zhou received tribute from the farthest lands,[7] Zhongzong[8] welcomed the Chanyu to court, and even under the feeble reigns of emperors Yuan[9] and Cheng,[10] the Four Barbarians still came to pay homage. Such are the lessons of history.

Hence, when the Xiongnu sought to guard the frontier, Hou Ying advised against it; when the Chanyu knelt at Weiyang Palace, Wangzhi[11] counseled against accepting his subservience. Thus, enlightened rulers manage barbarian affairs by maintaining vigilance and exercising consistent control. Even when these tribes prostrate themselves and offer tribute, the border defenses must not be relaxed. When they turn to banditry and violence, there is no need for far-reaching military campaigns. The goal is simply to ensure peace within our borders and prevent their encroachment upon our frontiers.

As the Zhou dynasty lost its authority, the feudal lords waged wars at will, the strong consuming the weak in a cycle of mutual destruction. Borders became unstable, and interests diverged. The barbarians seized this opportunity to infiltrate China. Some were enticed and pacified, becoming tools for various factions. For example, the calamity of Shen and Zeng toppled the Zhou royal house,[12] and Duke Xiang's alliance with the Jiang Rong against Qin suddenly empowered them.[13]

During the Spring and Autumn period, the Yiqu[14] and Dali[15] tribes occupied the lands of Qin and Jin, while the Luhun[16] and Yin Rong dwelt between the Yi and Luo rivers. The Souman[17] tribes ravaged the east of Ji, encroaching upon Qi and Song, and oppressing Xing and Wei. Southern Yi and Northern Di alternately invaded China, their incursions as unceasing as a thread. Duke Huan of Qi repelled them, preserving the endangered states and reviving defunct ones. He campaigned north against the Mountain Rong, opening the road to Yan. Thus, Confucius praised Guan Zhong's strength and commended his achievement in civilizing the barbarians.

By the end of the Spring and Autumn period, as the Warring States era flourished, Chu absorbed the Man tribes, Jin annihilated the Luhun, Wu of Zhao adopted Hu attire and opened up the Yuzhong region, while Qin, dominant in Xianyang, exterminated the Yiqu and their ilk. When the First Emperor unified All Under Heaven, he incorporated the Hundred Yue in the south and drove away the Xiongnu in the north. The Great Wall stretched across five mountain ranges, with millions of troops stationed. Though military service was burdensome and bandits ran rampant, the accomplishments of a single generation saw the barbarians fleeing in retreat. At that time, the Four Barbarians no longer existed within China proper.

The rise of Han saw its capital established in Chang'an, with the commanderies within the passes known as the Three Adjuncts - the ancient Yu Gong's Yongzhou,[18] the old territory of the Zhou's Feng and Hao. After Wang Mang's defeat and the subsequent Red Eyebrows Rebellion, the western capital lay in ruins, its people scattered. During the Jianwu era (25 - 56), Ma Yuan[19] was appointed Administrator of Longxi to suppress the rebellious Qiang. Their remnants were relocated to the empty lands of Pingyi and Hedong within the passes, intermingling with the Han people. After several years, their population flourished. Emboldened by their strength and resenting Han encroachment, they rebelled.

In the first year of Yongchu (107), Cavalry Commander Wang Hong[20] was dispatched to the Western Regions, conscripting Qiang and Di troops as escorts. This sparked panic among the Qiang tribes, inciting each other to revolt. The barbarians of two provinces rose simultaneously, overwhelming officials and massacring cities. Deng Zhi's campaign ended in the abandonment of armor and weapons, with corpses piled high and armies destroyed.[21] As successive expeditions failed, the barbarians grew ever bolder, penetrating south into Shu and Han, plundering east into Zhao and Wei, breaching the Zhi Pass, and invading Henei.

When Northern Army Commander Zhu Chong was sent with five battalions to confront the Qiang at Mengjin, a decade of conflict ensued, with both Chinese and barbarians suffering heavy losses. Ren Shang[22] and Ma Xian[23] barely managed to subdue them. The reason for this prolonged and severe devastation, while partly due to incompetent governance and inadequate military leadership, was it not also because the enemy struck at our very heart, the harm arising from within? Like a grave illness difficult to cure, or a great wound slow to heal!

From that time on, the embers of conflict were never fully extinguished. At the slightest opportunity, the barbarians would renew their invasions and rebellions. Ma Xian's efforts ended in disaster, while Duan Jiong's campaigns swept from west to east.[24] The barbarians of Yongzhou remained a constant threat to the state, becoming the greatest menace of the middle period. As the Han dynasty crumbled, Guanzhong was devastated.

In the early days of Wei's ascendancy, with Shu now separated, the frontier barbarians were divided between the two states. Emperor Wu of Wei ordered General Xiahou Miaocai[25] to suppress the rebellious Di tribes led by Agui and Qianwan. Later, after abandoning Hanzhong, he relocated the tribes of Wudu to the Qin plains, hoping to weaken the enemy and strengthen the state, while defending against the Shu forces. This was merely an expedient measure, a temporary strategy, not a policy beneficial for ten thousand generations. Now, as we face the consequences, we already suffer from its ill effects.

Guanzhong boasts rich soil and abundant resources, with fields of the highest quality. The Jing and Wei rivers irrigate its alkaline lands, while the Zhengguo and Bai canals[26] form an interconnected irrigation network. The bounty of millet and sorghum yields a full zhong (vessel) per mu, with commoners singing praises of its prosperity. Emperors and kings have always chosen to make their capital here. Never was it meant to be a land for barbarians. Those not of our kind must surely harbor different intentions. The ambitions of the barbarians do not align with those of the Chinese.

Yet, taking advantage of their weakness, we relocated them to the imperial domain. Our gentry and common folk grew complacent, scorning their perceived frailty, unknowingly nurturing a poison of resentment in their very marrow. As their numbers grew and strength increased, so did their ambitions. With their greedy and fierce nature, coupled with pent-up anger, they watch for any opening to commit treachery. Dwelling within our borders without the barrier of frontier defenses, they can easily overwhelm the unprepared and gather resources from the countryside. Thus, they are able to wreak havoc and inflict immeasurable harm. This is an inevitable outcome, a lesson already learned through bitter experience.

The appropriate course of action now, while our military might is at its peak and before other matters arise, is to relocate the Qiang tribes from within the borders of Pingyi, Beidi, Xinping, and Anding to the lands of Xianling, Hankai, and Xizhi. We should also move the Di people from Fufeng, Shiping, and Jingzhao back to the right side of Long Mountain, settling them in the regions of Yinping and Wudu. We must provide rations for their journey, ensuring they have enough to sustain themselves. Each tribe should be returned to their original lands and ancestral territories, with the tributary states and pacified barbarians assisting in their resettlement.

By separating the Rong and Jin peoples, each will find their proper place. This aligns with the ancient principle and establishes a lasting policy for our prosperous age. Even if they harbor intentions to deceive China or raise alarms of conflict, they will be far removed from the Middle Kingdom, separated by mountains and rivers. Though they may still raid and plunder, the extent of their harm will be limited.

This is why Chongguo[27] and Ziming[28] were able to control the fate of numerous Qiang tribes with just tens of thousands of troops, achieving victory without battle and succeeding with their armies intact. Although they had deep strategies and far-reaching plans for victory, was it not because the Chinese and barbarians were kept separate, distinctions maintained between civilized and uncivilized, and strategic passes were easy to defend, that they were able to achieve such success?

The Critic's Challenge:

“At present, Guanzhong has endured two years of violent upheaval. The burden of military campaigns has exhausted our forces of a hundred thousand. Floods and droughts have brought successive famines, while plagues have caused widespread death and suffering. The rebels have been executed, and those who regret their misdeeds are beginning to submit. They approach cautiously, filled with fear and trepidation. The common people are weary and distressed, united in their concerns. They long for peace as parched earth yearns for rain. Surely, we should pacify them with tranquility. Yet you propose to mobilize labor, embark on grand projects, and relocate these suspicious barbarians with our exhausted populace? To move hungry people and starving prisoners? I fear our strength will be depleted, our efforts unfinished. The Qiang and Rong will scatter, their loyalties divided. Before the current threat is quelled, new perils will arise.”

The Response:

“The Qiang and Rong are cunning, self-appointed in their titles. They have besieged cities, fought in open fields, harmed our officials, and amassed armies through winters and summers. Now their disparate groups have crumbled, their unified front collapsed. The old and young are captive, while able-bodied men have surrendered or dispersed. They are as scattered as birds and beasts, incapable of reuniting.

Do you believe they still have resources, or that they regret their evils and wish to submit to our benevolence? Or have they reached the end of their strength and wisdom, fearing our military might? Clearly, they are utterly spent. Thus, we can dictate their fate, controlling their every move.

Those content with their lot do not easily change; those satisfied with their dwellings harbor no desire to relocate. While they doubt themselves and fear us, we can use our military prowess to ensure their compliance. As they are scattered and disorganized, each household an enemy to the people of Guanzhong, we can relocate them to distant lands, severing their attachment to this soil.

The plans of sages and wise men address issues before they arise and bring order before chaos ensues. Their methods achieve peace without notoriety, their virtue succeeds without fanfare. The next best approach is to turn calamity into fortune, failure into success, to overcome difficulties and find passage through obstruction. You now face the end of a flawed policy yet fail to envision a new beginning. You cling to the toil of a misguided path, inviting further disaster. Why is this?

Guanzhong houses over a million souls, half of whom are barbarians. Whether they stay or leave, provisions are necessary. If there are those who lack food, we must use the granaries of Guanzhong to sustain them, preventing both starvation and the temptation to plunder. By relocating them with provisions for the journey, allowing them to reunite with their tribes and support each other, the people of Qin will retain half their grain. This strategy feeds those who depart, leaves stores for those who remain, eases the pressure in Guanzhong, removes the root of banditry, eliminates immediate losses, and establishes long-term benefits.

To shirk from temporary exertion and forsake a strategy of lasting peace, to begrudge present hardships and ignore the threat of generational enemies – this is not the way of those who can innovate and accomplish great deeds, who establish legacies and lay foundations for posterity.

The barbarians of Bingzhou were originally the most vicious bandits among the Xiongnu. During the reign of Emperor Xuan of Han, they were decimated by cold and hunger, their nation split into five factions, later consolidating into two. Huhanye,[29] weakened and isolated, unable to sustain himself, sought refuge at the frontier, submitting to Han rule. During the Jianwu era, the Southern Chanyu again came to surrender, and was allowed to settle within the frontier, south of the desert. After several generations, they repeatedly rebelled, leading to numerous military campaigns by He Xi[30] and Liang Qin.[31]

In the Zhongping era, when the Yellow Turban Rebellion erupted, their troops were conscripted, but their people refused to comply and killed their Qiangqu. Consequently, Yumifuluo sought Han assistance to suppress the rebels. Amidst the ensuing chaos, they seized the opportunity to pillage Zhao and Wei, with their raids reaching Henan. During the Jian'an period, the Right Wise Prince Qubei was sent to entice Huchuquan to surrender, allowing his tribes to disperse and settle in six commanderies. By the Xianxi era, as one tribe had grown too powerful, it was divided into three groups. At the beginning of the Taishi era, this was further increased to four. Subsequently, Liu Meng rebelled internally, colluding with external barbarians. Recently, Hao San's rebellion erupted in Guyuan.[32] Today, the population of the five tribes numbers tens of thousands of households, surpassing that of the Western Rong. Their innate bravery and skill with bow and horse exceed even that of the Di and Qiang. Should there be any unforeseen turmoil, the Bingzhou region would be cause for great concern.

The Gouli people of Xingyang originally dwelt beyond the frontier of Liaodong. During the Zhengshi era (240 – 249), when Youzhou Inspector Guanqiu Jian[33] suppressed their rebellion, he relocated their remaining tribes. Initially numbering only a hundred households, their descendants have now multiplied to thousands. After several generations, they will surely become numerous and prosperous. Today, even when common people neglect their duties, they may flee or rebel; when dogs and horses are well-fed, they may bite. How much more so might barbarians cause upheaval! We are only spared because their power is still weak and their influence limited.

In governing a state, the worry is not poverty but inequality, not scarcity but instability. With the vastness of the Four Seas and the wealth of our people, why should we need barbarians within our borders to suffice? These groups should all be instructed and dispatched back to their original domains, soothing their homesickness as sojourners and alleviating our Huaxia people's concerns. To bestow kindness upon the Middle Kingdom and thereby pacify the four quarters, to extend virtue for generations to come - this is the wisest course of action.”

[1] On the Relocation of Barbarians is a political treatise written by Jiang Tong in 299 after the rebellion of Qi Wannian. Jiang Tong proposed that the Hu peoples should be relocated, but the Western Jin court, then under the regency of Jia Nanfeng, did not adopt his recommendations. Five years later, the Sixteen Kingdoms period began.

[2] Wu Ding (? – 1192 BCE) was a king of the Shang dynasty. In classical Chinese historiography, he is often depicted as a meritorious king who appears with worthy officials. He conquered and annexed Guifang, turning its people into his supporters in expeditions against other enemies.

[3] Guifang (鬼方) was an ancient ethnonym for a people that fought against the Shang dynasty. This Chinese exonym combines gui (lit. ghost, spirit, devil) and fang (lit. side, border, country, region), referring to "non-Shang or enemy countries that existed in and beyond the borders of the Shang polity."

[4] The Kunyi (昆夷), also known as Quanrong (犬戎), were an ethnic group active in the northwestern part of Shaanxi during and after the Zhou dynasty. They were classified as the Western Yi and a member of the Guifang during the Shang dynasty and as Western Rong during the Zhou dynasty. They were regarded as one of the ancestors of the Xiongnu people. Scholars believe Quanrong was a later name for the Xianyun (猃狁).

[5] The Battle of Baideng was a military conflict between Han China and the Xiongnu in 200 BC. The vanguard of Han troops was trapped in the fort with Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang.

[6] Emperor Wen of Han (203 – 157 BCE), personal name Liu Heng, was the fifth emperor of the Han dynasty from 180 until his death. He continued the heqin policy by giving the Xiongnu Chanyu a prince's daughter in marriage, while placing Liu Li in Bashang against potential Xiongnu attack.

[7] The original term is "九译之贡". "九译" (jiǔ yì) literally means "nine interpreters" or "nine translations." This term was often used hyperbolically to represent multiple layers of translation needed for communication with distant peoples or tribes.

[8] Emperor Xuan of Han (91 – 48 BCE), temple name Zhongzong, was the tenth emperor of the Han dynasty, reigning from 74 to 48 BCE. During his reign, the Han dynasty prospered economically and militarily became a regional superpower, and was considered by many to be the peak period of the entire Han history.

[9] Emperor Yuan of Han (75 – 33 BCE) was the eldest son and successor of Emperor Xuan of the Han dynasty. He reigned from 48 to 33 BCE. Emperor Yuan promoted Confucianism as the official creed of the Chinese government. He appointed adherents of Confucius to important government posts. In 33 BCE, he sent Wang Zhaojun to marry Chanyu Huhanye of the Xiongnu Empire in order to establish friendly relations through marriage. (heqin)

[10] Emperor Cheng of Han (51 – 7 BCE) was the son and successor of Emperor Yuan. He reigned from 33 to 7 BCE. Under his rule, the Han dynasty continued its growing disintegration as the emperor's maternal relatives from the Wang clan increased their grip on power. Emperor Cheng died childless. Both of his sons and their mothers were killed by the order of his favorite consort Zhao Hede. He was succeeded by his nephew, Emperor Ai, whose death was followed by Wang Mang's rise to power.

[11] Hou Ying and Xiao Wangzhi (? – 46 BCE) were both officials of the Han dynasty.

[12] The Marquess of Shen (d. 771 BCE) was a Qiang ruler of the ancient state of Shen during the Zhou dynasty. It was an important vassal state responsible for guarding the Guanzhong region against Western Rong incursions. One of the Marquess's daughters was married to King You as his queen, and gave birth to Crown Prince Yijiu, but another consort named Bao Si gained the favor of the king, who wanted to depose the queen and the crown prince in favor of her son Bofu. Furious, the Marquess allied with the Zeng state and Quanrong to attack the Zhou capital Haojing in 771 BCE. King You was defeated and killed, and Haojing was sacked by Quanrong.

[13] Duke Xiang of Jin was from 627 to 621 BCE the ruler of the State of Jin, a major power during the Spring and Autumn period. In 627 BCE, he allied with the Jiang Rong and launched a surprise attack against Qin at the Battle of Yao. They annihilated the Qin army and captured three Qin generals. After the battle, the power of Qin had been checked for a long period.

[14] Yiqu (義渠) was an ancient state which existed in the Hetao region (now Ningxia, eastern Gansu and northern Shannxi). It was a rival of the state of Qin. It was inhabited by a semi-sinicized people called the Rong of Yiqu, who were regarded as a branch of western Rong people.

[15] Dali (大荔) was an ancient state founded by a branch of the Western Rong people which existed in what is now Dali County, Shaanxi. In 461 BCE, Qin annexed Dali.

[16] Luhun (陆浑) was a tribal state founded by a branch of the Rong of Yun surname. They inhabited the northwestern regions of the states Qin and Jin and later became a vassal of Jin. In 525 BCE, Jin annexed Luhun. Scholars believe Yin Rong (阴戎) was an alternative name for Luhun.

[17] Souman (鄋瞒) was a branch of the Di people. Its capital is in present-day Gaoqing County in Zibo, Shandong. In 594 BCE, Jin conquered Souman.

[18] The Yu Gong or Tribute of Yu (禹贡) is a chapter of the Book of Xia, section of the Book of Documents, one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. This chapter describes Yu the Great and the provinces of his time. Yong Province or Yongzhou was the name of various regions and provinces in ancient China, usually around the Wei River or the imperial capital. It was one of the legendary Nine Provinces of China's prehistoric antiquity.

[19] Ma Yuan (馬援, 14 BCE – 49) was a general and politician of the Eastern Han dynasty. He played a prominent role in defeating the Trung sisters' rebellion. He also subjugated the Qiang and made possible a restoration of Chinese positions on the old frontiers.

[20] Wang Hong (王弘, ? – ?) was an official and uncle to Emperor Cheng of the Western Han dynasty.

[21] Deng Zhi (邓骘, ? – 121) was a general during the Eastern Han dynasty. His forces was routed by the Western Qiang in 107.

[22] Ren Shang (任尚, ? – 118) was a general during the Eastern Han dynasty. He defeated multiple Northern Xiongnu and Qiang forces during his tenure. In 118, he was executed due to his rivalry with Deng Zun over military achievements, falsely reporting the number of Qiang people killed, and accepting bribes.

[23] Ma Xian (马贤, ? – 141) was a general and official during the Eastern Han dynasty. During his tenure as Protector General of the Qiang (护羌校尉), his multiple victories against various Qiang tribes were crucial in maintaining order in Longyou and Liangzhou regions. In 141, he and his sons were killed in battle against the Qiedong tribe of the Qiang.

[24] Duan Jiong (段颎, ? – 179) was a general during the Eastern Han dynasty. He was a member of the powerful Duan family of Wuwei Commandery. He defeated multiple Qiang rebel forces during his tenure.

[25] Xiahou Yuan (夏侯渊, ? – 219), courtesy name Miaocai, was a general and politician serving under the warlord Cao Cao in the late Eastern Han dynasty. He is known for his exploits in western China in the 210s, during which he defeated Cao Cao's rivals Ma Chao and Han Sui in Liang Province and forced several Di and Qiang tribal peoples into submission.

[26] The Zhengguo Canal, named after its designer, Zheng Guo, is one of the biggest water conservation projects in ancient China. The canal irrigates the Guanzhong plain and connects the Jing River and Luo River, northern tributaries of the Wei River. The Bai Canal was designed by Bai Gong in 95 BCE and was often mentioned together with Zhenguo Canal as “Zhengbai Canal.”

[27] Zhao Chongguo (赵充国, 137 – 52 BCE) was a general of the Western Han dynasty. He was known for his adoption of the tuntian policy during his pacification of the Western Qiang people.

[28] Lü Meng (吕蒙, 178 – 220), courtesy name Ziming, was a military general and politician who served under the warlord Sun Quan during the late Eastern Han dynasty.

[29] Huhanye (呼韓邪) was a Chanyu of the Xiongnu Empire. He rebelled in 59 BCE, leaving the Xiongnu torn apart by factional strife. After his defeat, he fled south and submitted to the Han dynasty. He travelled to Chang'an to visit Emperor Xuan, who allowed his tribe to settle in the Yinshan area.

[30] He Xi (何熙, ? – 110) was a general of the Eastern Han dynasty. In 109, he defeated the Southern Xiongnu Aojian Rizhu Prince at Meiji. Shortly after his death in 110, the Southern Xiongnu surrendered.

[31] Liang Qin (梁慬, ? – 112) was a famous general of the Eastern Han dynasty. In 110, forces of Xiongnu, Wuhuan and Xianbei invaded Wuyuan. Liang Qin was sent with He Xi to fight them.

[32] Hao San (郝散, ? – 294) was a Xiongnu rebel leader who was killed in 294. In 296, his brother Hao Duyuan joined Qi Wannian’s rebellion.

[33] Guanqiu Jian (毌丘儉, ? – 255) was a general and politician of the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period. In 244, Guanqiu Jian led a punitive expedition to Goguryeo (Gouli). He defeated the Goguryeo army and captured the its capital Hwando. During the follow-up campaign in the next year, he conquered Hwando again and forced its King to flee.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Birthdays for today, October 13th:

Xiaowen of Northern Wei, Emperor of China, 467

Eleanor of England, Queen of Castile, 1162

Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, 1453

Claude of France, Queen of France, 1499

Luisa de Guzmán, Queen of Portugal, 1613

Aimone of Savoy-Aosta, Duke of Apulia, 1967

Margarita of Bourbon-Parma, Countess of Colorno, 1972

Jaime of Bourbon-Parma, Count of Bardi, 1972

#Xiaowen of Northern Wei#eleanor of england#edward of westminster#claude of france#luisa de guzman#aimone of savoy aosta#margarita of bourbon parma#jaime of bourbon parma#long live the queue#royal birthdays

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: a search result list for han dynasty emperors. the results listed are “Han Wudi,” “Emperor of China,” “Qin Shi Huang,” “Emperor Jing of Han,” and “Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei.” /end ID]

woag…..each day i learn some more 👍

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

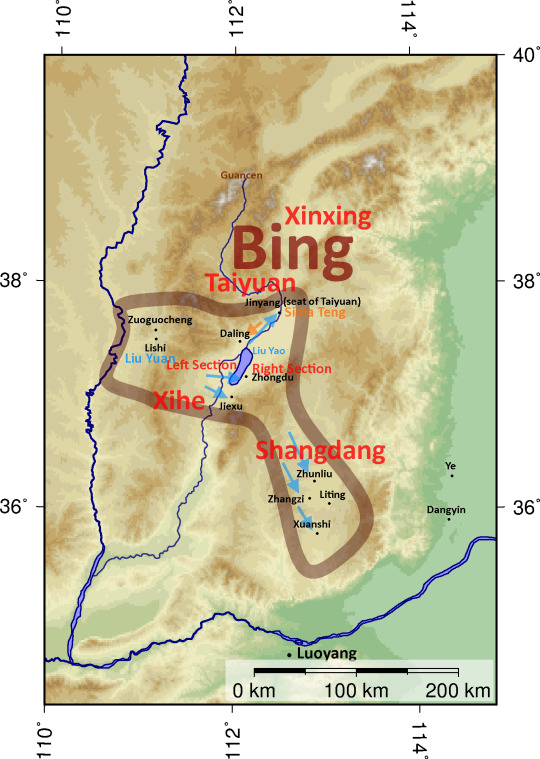

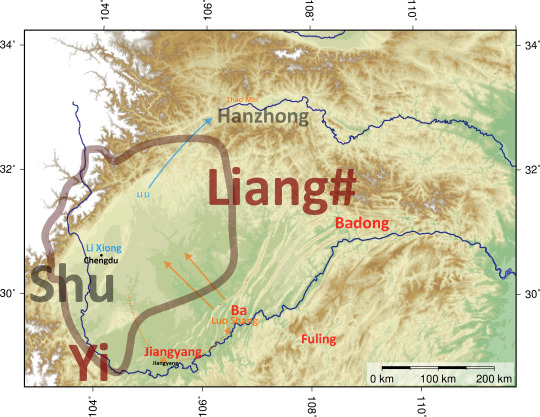

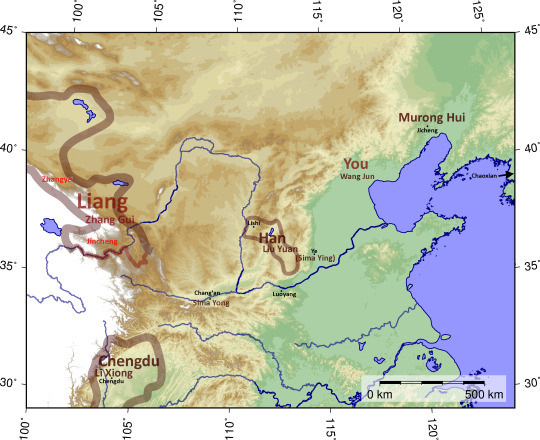

Rise of Sixteen States: 304

This year there were many affairs.

Liu Yuan declares himself King of Han.

Li Xiong declares himself King of Chengdu

22 February 304 – 10 February 305

(Jin's 1st Year of Yongxing)

(Han's 1st Year of Yuanxi)

(Chengdu's 1st Year of Jianxing)

3rd Month, wushen [1 May], used the King of Chengdu, Ying as August Brother-Heir and Commander-in-Chief of All Army Affairs in the Centre and Outside, and Assisting Chancellor.

7th Month, bingshen, New Moon [17 August], the General of the Guards of the Right, Chen Zhen, used a decree summoning the hundred companions to enter within the hall, and following that directed troops to punish the King of Chengdu, Ying.

On jihai [20 August], the Minister over the Masses, Wang Rong, the King of Donghai, Yue, and others served the Emperor on a northern campaign. They arrived at Anyang with a multitude of 100 000. Ying dispatched his general Shi Chao to resist them in battle.

On jiwei [9 September], the Six Armies were defeated at Dangyin. Arrows reached the Driving Carriage, the hundred officials divided and scattered. The Emperor that evening favoured Ying's chariot, the next day he favoured Ye.

8th Month [16 September – 15 October], the General who Calms the North, Wang Jun, dispatched Wuwan cavalry to attack the King of Chengdu at Ye, greatly routing him. Ying drove with the Emperor in a single chariot to flee to Luoyang.

11th Month, yiwei [14 December], Zhang Fang coerced the Emperor to favour Chang'an.

The King of Hejian, Yong, led public officials and 30 000 infantry and cavalry to welcome [the Emperor] at Bashang.

(Liu Yuan)

The King of Chendu, Ying, became August Brother-Heir. He used Yuan as Colonel of Garrison Cavalry to the Brother-Heir. Emperor Hui attacked Ying, and stayed at Dangyin. Ying made use of Yuan as General who Assists the State and Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Affairs of the Northern City. When Emperor Hui had been defeated, he used Yuan as General of the Best of the Army, ennobled as Earl of Lunu. Soon after, the Inspector of Bing province, the Duke of Dongying, Teng, and the General who Calms the North and Inspector of You province, Wang Jun, raised troops to attack Ying. Ying's host fought and was defeated. Yuan spoke to Ying, saying:

Now the two garrisons trample on restraint, with a multitude exceeding 100 000. [I] fear we will not be able to manage them with the personal guards and the nearby commanderies' gentlemen and people. Yuan will, Your Highness, return to explain to the Five Sections, assemble and gather a righteous multitude, and thereby hasten to the state's difficulties.

Ying said:

The multitudes of the Five Sections, can they protect and set out already or not? Allowing for you being able to send them out, the Xianbei and Wuhuan are strong and quick like the wind and clouds. How easily can it be done? I wish to serve the Driving Carriage and return to Luoyang, and avoid their spear points, calmly summon Under Heaven to arms, and govern them according to their opposition or loyalty. Lord, what are your thoughts?

Yuan said:

Your Highness is the son of the Martial August Emperor, and has special merits in the royal house. Your power and kindness shine in harmony, the Four Sea's reverent wind. Who would not consider to lose their lives and throw down their bodies for Your Highness? What is the difficulty in sending them out! Wang Jun is an upstart son and Dongying a distant cousin, how could they contend equally with Your Highness?

If Your Highness goes out alone from the Ye palace, and shows weakness to people, is it possible then to arrive in Luoyang? Suppose you reach Luoyang, power and authority will not be restored to Your Highness. A paper calling to arms is a foot-long letter, who will the person be who receives it!

Moreover the Eastern Hu's courage does not exceed the Five Sections. [I] wish Your Highness would encourage and console the multitude soldiers, calming them down and thereby quell them. [I] will, Your Highness, use two sections to destroy Dongying and three sections to put on display Wang Jun. You can point to the day when the heads of the two upstarts will be hanging up.

Ying was pleased and designated Yuan as Northern Chanyu, Assisting the Army Affairs of the Imperial Chancellor. Yuan arrived at Zuoguocheng. Liu Xuan and others elevated him to the title of Great Chanyu. Within twenty days the multitude was soon 50 000. He set his capital at Lishi. He dispatched the Yulu King of the Left, Hong, to lead 5 000 elite cavalry and meet up with Ying's general Wang Cui and resist the Duke of Dongying, Teng. But Cui had already been defeated by Teng, so Hong returned back with nothing done.

Wang Jun sent General Qi Hong to lead Xianbei and attack Ye. Ying was defeated, and held onto the Son of Heaven to run south to Luoyang. Yuan heard Ying had left Ye, he sighed and said:

Ying did not employ my words, on the contrary he is himself running from disaster. He truly has menial talents. However as I and him had words, I cannot but aid him.

Hence he instructed the Yulu King of the Right, Liu Jing, and the Dulu King of the Left, Liu Yannian, and others to lead 20 000 infantry and cavalry, and commanded them to punish the Xianbei. Liu Xuan and others firmly remonstrated, saying:

Jin is without the Way, slaves and lackeys govern us. Therefore the Worthy King of the Right's fierceness does not surpass his anger. Just now Jin's guide ropes are not spread. [If] the great affair is not followed through, the Worthy of the Right will smear [himself] with earth, to the Chanyu's shame.

Now in the Sima clan, father and son, elder and younger brother, are themselves [chopping] each other [like] fish meat, this is Heaven casting aside Jin's virtue and conferring it on us. [If] the Chanyu stores up virtue in his body, and is submitted to by the people of Jin, [he] soon will raise up our nation and tribe and restore the patrimony of Huhanxie. The Xianbei and Wuhuan are of our manners and type, and could be used as helpers, why would [we] resist them and aid [our] foes!

Now Heaven is acting through us and cannot be disobeyed. To disobey Heaven is not auspicious, to go against the multitudes is not helpful. [He who when] Heaven gives does not take, will in turn receive his calamity. [I] wish the Chanyu would not doubt.

Yuan said:

Good. [I] will be raising up the hill to the pinnacle mound, why would I make a hillock! As for Emperors and Kings, when where they regular? Yu the Great was born among the Western Rong, King Wen was born among the eastern Yu. Looking back, they were conferred for virtue, that was all. Now [I] see a multitude of more than 100 000, and anyone of us is a match for ten of the Jin. To strike the march and destroy chaotic Jin is like snapping deadwood, that is all. At best I can complete the legacy of Gao of Han, at worst I will be no less than the Wei clan. How is Huhanxie a sufficient course of action!

However, the people of Jin are not necessarily similar to us. Han had Under Heaven for many generations, kindness and virtue connection to the population's hearts. Thus though Zhaolie [lived] rough and rugged in the lands of a single province, he was yet able contend at an equal level Under Heaven. I am also a sister's child of the Han clan, sworn to be elder and younger brothers. When the older brother perishes, the younger carries on. Can we not do likewise? Now moreover, I can raise up Han, posthumously honour the Later Ruler, and thereby comfort the populace's expectations.

Xuan and others touched head to ground, saying:

[They] are not reaching up [to you].

1st Year of Yuanxi [304 AD], he moved to Zuoguocheng. The Jin people who [came from] the east to adhere were several ten thousand. Xuan and others sent up [to assume] the venerated title. Yuan said:

Now the Jin clan still exist, the Four Regions are not yet settled. [We] can look up to and honour the Exalted August's first regulations, and moreover designate [me] King of Han [while] for the moment delaying the tile of August Emperor. [When I] hear the cosmos is mixed into one [I] will once more discuss it.

10th Month [14 November – 10 December], he had an altar in the southern suburbs, and falsely ranked as King of Han. He sent down an order, saying:

Formerly our Grand Founder [taizu], the Exalted [gao] August Emperor used his divine martial ability to follow expectations, and broadly began the great patrimony. The Grand Ancestor [taizong], the Filial and Civil [xiaowen] August Emperor gave weight to using enlightened kindness, peace and prosperity was the Way of Han. The Generational Ancestor [shizong], the Filial and Martiaizul [xiaowu] August Emperor expanded the territory and repelled the yi, the territory exceeding the days of Tang. The Middle Ancestor [zhongzong], the Filial and Propagating [xiaoxuan] August Emperor, sought and lifted up the capable and outstanding, many scholars filled the court.

Hence the Way of our founder and ancestors strode pass the Three Kings, their achievements exalted as the Five Emperors. For that reason the foretold years were many times the Xia and Shang's, the foretold generations exceeded the Ji clan. But Yuan and Cheng had many crimes, Ai and Ping were briefly blessed. The traitorous subject Wang Mang overflowed Heaven and usurped disobediently.

Our Generational Founder [shizu], the Brilliant and Martial [guangwu] August Emperor was expansively endowed with sagely martial ability. He immensely restored the vast foundation, worshipped Han matched with Heaven, and did not neglect old matters, so that the Three Luminaries' obscurity were yet restored to clarity, the Three Receptacles' darkness were yet restored to visibility. The Manifesting Ancestor [xianzong], the Filial and Enlightened [xiaoming] August Emperor, and the Solemn Ancestor [suzong], the Filial and Articulating [xiaozhang] August Emperor, amassed eras, the blazing light twice revealed.

From He and An and afterwards, the august guide-ropes gradually decayed, Heaven's pace was hard and difficult, the state's government again and again cut off. The Yellow Turban seas boiled in the Nine Provinces, the crowd of eunuchs' poison flowed in the Four Seas. Dong Zhuo following that indulged his careless heedlessness, Cao Cao, father and son, fell rebels, were soon after.

For that reason Xiaomin let go and put aside the ten thousand states. Zhaolie strayed beyond Min and Shu, hoping the stoppage in the end would have exaltation, returning the carriage box to the old capital. How to assess Heaven not regretting the calamity, the Later Emperor was embarrassed and humiliated.

Since the altars of soil and grain were lost and ceased, the ancestral temple have not had blood to eat for forty years until this point. Now Heaven is coaxing its inner self, regretting the calamity to August Han, and making the Sima clan, father and son, elder and younger brother, repeatedly break and wipe out each other. The numerous multitudes are in the mud and soot, scattering to denounce and accuse.

This Orphan is now all at once pushed forward by the crowd of excellencies, to carry on offering to the Three Founders' legacy. Looking at [my] current crippled ignorance, [I] shiver in fear for collapsing in a shallow grave. However, as the great shame is not yet wiped away, the altars of soil and grain are without a host, with gall in the mouth and the roost cold, [I] will strive to follow the crowd's opinion.

He changed Jin's 1st Year of Yongxing to be the 1st Year of Yuanxi [“Inaugural Radiance”], there was a great amnesty Under Heaven. He posthumously venerated Liu Shan as the Filial and Cherished [xiaohuai] August Emperor. He established Gaozu of Han and below, three Founders and five Ancestors, as divine rules and worshipped them. He established his wife, Ms. Huyan as Queen, set up the hundred officials, and used the Worthy King of the Right, Xuan, as Imperial Chancellor, Cui You as Imperial Clerk Grandee, the Yulu King of the Left, Hong, as Grand Commandant, Fan Long as Great Herald, Zhu Ji as Grand Master of Ceremonies, Cui Yizhi of Shangdang and Chen Yuanda of the Rear Section both as Gentlemen of the Yellow Gates, his clan-child Yao as General who Establishes the Martial, the remainder were designated and conferred each proportionally. You firmly declined and did not go.

12th Month [12 January 305 – 3 February], the Duke of Dongying, Teng, sent General Nie Xuan to chastise him, they fought at Daling. Xuan's host achieved defeat. Teng was afraid, he led more than 20 000 households of Bing province to go down East of the Mountain. Thereupon [the people who] lived there were robbed. Yuan dispatched his General who Establishes the Martial, Liu Yao, to rob Taiyuan, Xuanshi, Zhunliu, Zhangzi and Zhongdu, all were lost to him.

He also dispatched the General of the Best of the Army, Qiao Xi, to rob Xihe. The Prefect of Jiexu, Jia Hun resisted steadfastly and did not surrender, saying:

I am a defender of Jin, [if I am] not able to maintain it, why cautiously seek to live therefore serving thieves and miscreants? How could I face accordingly to watch and breath in the world!

Xi was angry, apprehended and wanted to kill him. Xi's general Yin Song said:

[If] the General saves him, [he can] thereby convince [him] to serve you, Lord.

Xi did not listen and thereupon murdered him. Jia Hun's wife, Ms. Zong, had a beautiful figure and Xi desired to take her. Ms. Zong reviled him, saying:

Slave of the Tuge, how can you murder a person's husband then desire to assign [her] without decorum, how is this to you? Why do you not hurry and kill me!

Then she raised her head to Heaven and greatly wept. Xi thereupon murdered her. At the time she was (more than) 20 years old. Yuan heard about it, and greatly angered said:

If it is the Way of Heaven to be perceptive, the view of Qiao Xi has sown seeds!

When the pursuers returned, he demoted his salary four grades, collected Hun's corpse and buried it.

(Cui You)

Cui You, courtesy name Zixiang, was a native Shangdang. As young he was fond of studying, he was discerning and enlightened in the Ruist methods, tranquil, peaceful, humble and withdrawn. From young to old his mouth not once spoke about wealth and profit. At the end of Wei, he was examined as Filial and Upright, and appointed Retainer of the Chancellor's Office. He set out to be Chief of Dichi, he was very kind in government affairs. He retired due to illness, and thereupon was disabled and sick.

At the beginning of Taishi [265 – 274], Emperor Wu favoured the succession from Emperor Wen's old office companions and staff, and attended on the family to designate a Palace Gentleman. Aged more than 70, he still esteemed studying and did not tire. He compiled a Chart of Mouring Clothes, which has come down through the ages. He passed on at home, at the time he was 93 years old.

(Liu Cong)

Liu Cong, courtesy name Xuanming, also named Zai, was Yuan's 4thson. His motherwas named Lady Zhang.Earlier, when she was pregnant with Cong, Lady Zhang dreamt the sun enter her breast. She woke up and told Yuan. Yuan said:

This is a good omen, take care not to talk of it.

Fifteen months from that then she gave birth to Cong, at night there was an exceptional white light. The shape of his body was not usual. In his left ear there was a single white hair, more than two chi long with considerable shine and lustre. As a young child he was yet intelligent and aware and fond of studying, the Broad Scholar Zhu Ji greatly marvelled at him. At the age of fourteen, he delved thoroughly into the the classics and histories, and even more so the assembled words of the hundred schools. In Sun and Wu's Principles of War there was nothing he did not completely understand.

He was skilled with the draft and clerical scripts, and good with composing texts. He displayed and expressed his deepest feelings in more than a hundred chapters of poetry, and more than fifty chapters of rhapsodies and hymns. At fifteen he practised striking and stabbing. He had ape arms and was good at shooting, he could bend a bow 300 jin strong, was strong in body, valiant and agile, ahead and beyond the times. Wang Hun of Taiyuan saw and was pleased with him. He spoke to Yuan, saying:

This boy cannot be measured by me.

As a youth he drifted to the Imperial City, there were nobody of the famous scholars he did not communicate and connect with. Yue Guang and Zhang Hua particularly marvelled at him.

Jin's Grand Warden of Xinxing, Guo Yi, nominated him has Master of Accounts, he served accordingly in the commandery's affairs. He was recommended good and supportive, and entered to became Marshal of Detached Section of Valiant Cavalry. The King of Qi, Jiong, used him as Palace Commandant of State. He set out to be Marshal of the Left Section, and soon after amassed to move to Chief Commandant of the Right Section. He was good at consoling and connected, there were none of the Five Section's prominent and honoured who did not revert to him. The Grand Steward, the King of Hejian, Yong, petitioned him to be Commander of the Palace Gentlemen of the Red Sand.

Cong, since Yuan was at Ye, and he feared he would be murdered by the King of Chengdu, Ying, he absconded and ran to Ying. Ying was extremely pleased, and designated him General who Amasses Crossbows of the Right, Assisting the Battle Affairs of the Vanguards. When Yuan became Chanyu of the North, he was established as Worthy King of the Right, and accompanied to turn back to the Right Section. When he was enthroned as Great Chanyu, he changed his designation to Lulu King.

(Liu Yao)

Liu Yao, courtesy name Yongming, was Yuan's clan-child. He was orphaned young, and was nurtured by Yuan. As a youth, he was yet perceptive and intelligent, and had unusual measures. Aged eight sui, he accompanied Yuan to hunt in the Western Mountains, when they came across rain, and stopped beneath a tree. Suddenly, thunder shook near the tree. None of the people did not fall over and lie down, Yao in spirit and colour was like himself. Yuan was amazed by him, and said:

This is my family's thousand li colt, older cousin is not gone!

He was nine chi, three cun tall, his hands hang down past the knees. When he was born, his eyebrows were white and his eyes had a red glow. His beard and whiskers did not exceed a hundred roots, but all were five chi long. He by nature lifted up and let drop the high and brilliant, and was not among the crowd of the multitudes.

He read books with a mind towards a broad overlook, and did not concentrate on pondering chapters and verses. He was good at composing text and was skilled with the draft and clerical scripts. His gallantry and martial ability was beyond other people. Iron one cun thick he shot and pierced, at the time it was declared to be a godly shot. He particularly fond of military books and could recite roughly all from memory. He often made light of and ridiculed Wu and Deng, but compared himself with Yue Yi, Xiao, and Cao. At the time people did not acknowledge him, only Cong said:

Yongming is in the class of Shizu and Wu of Wei, how are some Excellencies worth mention!

As a youth he drifted to Luoyang, was implicated in an affair and was to be executed. Therefore he absconded with Cao Xun to run to Liu Sui. Sui hid him in a book cabinet, carried, and sent him off to Wang Zhong. Zhong sent him off to Chaoxian. For the remainder of the year, he was starving and hard-pressed. Thereupon he altered his family and personal name, and as a retainer became a county soldier. The Prefect of Chaoxian, Cui Yue, saw and was amazed with him. He gave him clothes and food, his charity and regard was very substantial. Cao Xun, though he was in the midst of a difficult situation, served Yao with the rites of lord and subject. Yao was very gracious to him. Later there happened to be an amnesty, and he was free to return home.

He himself, since his appearance and substance was different from the multitudes, and feared he would not be tolerated during the era, once lived in hiding in the mountains of Guancen, using a qin zither and books to amuse himself. In the middle of the night, suddenly there were two servant boys who entered, knelt, and said:

The King of Guancen sends his young subjects to offer his respects to the August Emperor of Zhao.

They presented a single edged sword, put it in front of him, bowed twice, and departed. He used a torch to look at it. The sword was two chi long, the shine and polish was not ordinary, red jade made up the sheath, on the back side there was an inscription which said:

The godly sword holds sway, removes the multitudes' poison.

Yao thereupon wore it. The sword followed the four seasons and altered to have the five colours.

(Shi Le)

1st Year of Yongxing [304 AD], the King of Chengdu, Ying, defeated the Driving Carriage at Dangyin, and pressured the Emperor to go to the Ye Palace. Wang Jun, since Ying had secluded and humiliated the Son of Heaven, sent Xianbei to strike him. Ying was afraid, clasped Emperor Hui and ran south to Luoyang. The Emperor then was pressured by Zhang Fang, and moved to Chang'an. East of the Passes troops were rising up, all using executing Ying as their name. The King of Hejian, Yong, feared the abundance of the eastern host, and wished to bring together and placate the Eastern Xia. He therefore memorialised to debate deposing Ying.

This Year, Liu Yuan declared himself King of Han at Liting.

(Li Xiong)

1st Year of Jianxing, Spring, 1st Month [22 February – 22 March), Luo Shang arrived at Jiangyang. The Minister of the Army, Xin Bao, went to Luo to show the circumstances. A written decree gave authority to control Badong, Ba commandery, and Fuling commanderies, to supply his army taxes.

(JS066: At the time the Inspector of Yi province, Luo Shang, was defeated by Li Te. He dispatched envoys to announce the urgency and request provisions. Hong circulated a letter to supply and provide. But the provincial office's mainstays and guidelines, as the transport roads were isolated and remote, and the civil and military officials wanting and weary, desired to use Lingling to alone transport 5 000 hu of rice to give to Shang. Hong said:

You Lords have not yet thought about it, that is all. Under Heaven is a single family, this and that are not different. If I today provide for him, then there is no anxiety in looking west.

Thereupon he used 30 000 hu of rice from Lingling to provide for him. Shang relied on it to strengthen himself.)

Winter, 10thMonth [14 November – 13 December], the various generals firmly requested Xiong accede to the venerated rank. (HYGZ: Yang Bao and Yang Bao together urged Xiong to declare himself King.) Hence he presumptuously declared himself King of Chengdu, with an amnesty within his territories, and changed the inaugural to Jianxing [“Establishing the Rise”]. He removed the Jin laws, and condensed the law into seven chapters.

He used his junior uncle Xiang# as Grand Tutor, his commoner-born older brother Shi as Grand Guardian, the Smashing Charges Li Li as Grand Commandant, his junior cousin, the Establishing Domination Li Yun as Minister over the Masses, the Supports the Army Li Huang as Minister of Works, the Talented Officials Li Guo as Grand Steward, Yan Shi as Prefect of the Masters of Writing, Yang Bao as Supervisor, Yang Fa as Palace Attendant, Yang Gui as Master of Writing, Yang Hong as Inspector of Yi province, Xu Yu as Garrisons the South, Wang Da as Army Teacher. For the remaining civil and military officials, he designated and conferred each proportionally.

He retroactively venerated his great grandson Hu as the Mighty [huan] Duke of Ba commandery, his grandfather Mu as the Accomplished [xiang] King of Longxi, his father Te as the Luminous [jing] King, his mother Ms. Luo as Queen Dowager. His senior uncle Fu as the Ardent [lie] King of Qi, his middle uncle Xiang as the Martial [wu] King of Liang#, his middle uncle Liu as the Civil [wen] King of Qin, his older brother Dang as the Strong and Civil [zhuangwen] Duke of Guanghan.

Winter, Shang relocated to station at Ba commandery. He dispatched an army to plunder within Shu. He beheaded Xiong's granduncle Ran, and captured Xiang#'s wife Zan, his son Shou, and his brothers.

12th Month [12 January – 10 February], Xiong's Grand Commandant Li Li invaded Hanzhong, and killed the Battle Leader Zhao Min.

(Zhang Gui)

Reaching the difficulties of the two Kings of Hejian and Chengdu, he dispatched 3 000 troops to proceed east to the Imperial City.

Earlier, at the end of Han, a man of Jincheng, Yang Chengyuan, killed the Grand Warden in rebellion. A man of the commandery, Feng Zhong, attended to the corpse, shouting and weeping. He vomited blood and died.

A man of Zhangye, Wu Yong, was appointed by the Colonel who Protects the Qiang, Ma Xian. Later he was on the staff of the Grand Commandant, Pang Can. Can and Xian defamed each other with crimes that merited death. Each pulled on Yong as evidence. Yong planned and reasoned without the two accepting responsibility, and thereupon he cut his own throat and died. Can and Xian were ashamed and remorseful, and themselves made peace and cleared out with each other.

Gui in both cases sacrificed at the their tombs and honoured their sons and grandsons.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Changing one’s genealogy and ethnicity in the Tang dynasty

Genealogy played a role not only in defining status but also ethnicity, including that of the imperial lineage itself. Just as Han Chinese sought status by claiming membership in a prestigious lineage, so non-Han individuals and families could advance socially by asserting a genealogy that would make them Han, and preferably Han with some notable ancestor or family line. The simplest genealogical path was to change one’s surname and those of one’s ancestors, of which the most blatant example was the imperial Li family itself. At least on its female side, and perhaps on the male side as well, the family descended from non-Han people, but it went to great lengths to construct a prestigious Han genealogy and even descent from Laozi.

The practice of changing surnames to reassign ethnic identity for political purposes had figured prominently at least since the Han, when non-Han hostages and surrendered Xiongnu might be given Han surnames. The Tuoba rulers of the Northern Wei adopted the Chinese surname Yuan and granted this as an award to many of their followers. When Emperor Xiaowen of the Wei launched a policy of sinicizing his court, he ordered the Tuoba nobility to take Chinese surnames. The Tang imperial house also granted its surname to nomads who submitted. In Tang times, many leading lineages of non-Han origins sought to efface their tribal roots. [...] One Tang genealogy stated that the Dugu clan — a non-Han family that had helped establish the Northern Zhou and whose women had married into imperial families in the Northern Zhou, Sui, and Tang — once had the surname Liu.

Less dishonest, and more frequent, was the strategy of claiming descent from a highly prestigious alien lineage, such as the ruling house of the Northern Wei. Most of the Guanzhong and Daibei elites followed this practice. An example was the assertion that the early Tang official Zhangsun Wuji descended from the imperial Tuoba house, when his actual ancestors were the lower-ranked Baba clan. [...] In status-conscious Tang society, being a tribal noble was more prestigious than having an ethnic Han pedigree. [...] Those who held office in semi-autonomous foreign communities also frequently claimed noble non-Han origins. Given the roles of these men as intermediaries between the Tang state and tribal allies, their non-Han genealogies could have been positively beneficial.

Yet another genealogical strategy was to claim that one’s founding ancestor was an ethnic Han who had been captured by alien tribes or for some other reason carried off to the west. The great Tang poet Li Bo, almost certainly of non-Han origins, invented such a genealogy. The ancestor most often chosen for this purpose was the Han dynasty general Li Ling, who was captured by the Xiongnu in 99 b.c. Descent from Li Ling was usually claimed by relatively unassimilated peoples such as the Uighurs and Kirghiz, who asserted this kin tie to assist them in making political alliances with the Chinese. Thus, both the Tang Emperor Wuzong and an allied Uighur leader claimed shared descent from Li Ling as a foundation for their collaboration. Tang writers explained the occasional appearance of black hair among the Kirghiz, who generally had blond or reddish hair, as being the result of intermarriage between Li Ling’s soldiers and the ancestors of the Kirghiz.

A final genealogical strategy for dealing across ethnic lines was the occasional practice among non-Han leaders of tracing descent from the legendary Yellow Emperor himself — the founding ancestor of the Han Chinese people — or from the ancient Zhou ruling house. Such claims flattered both those who made them and their Tang recipients, who could thus assert a larger realm for their putative ancestor. The Chinese had linked themselves to more distant peoples through a common origin in the ancient sage-kings at least since the late Warring States and early Han mythic geography, the Canon of Mountains and Seas (Shan hai jing).

From China’s Cosmopolitan Empire. The Tang Dynasty by Mark Edward Lewis

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Emperor Xiaowen and his entourage worshipping the Buddha, ca.522-23

Northern Wei dynasty, China

From the Central Binyang Cave, Longmen, Henan province

Limestone with traces of pigment

H. 82 in. (208.3 cm); W. 12 ft. 11 in. (393.7 cm)

Together with a companion piece showing an empress and her attendants (now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), this depiction of an emperor and his entourage once adorned the Central Binyang Cave (also known as Cave 3) in the Longmen complex, near Luoyang, in Henan province. It was positioned centrally on the northeast wall between a group of protective semidivinities above and a narrative debate scene below. Xuanwu commissioned the construction of the Central Binyang Cave in honor of his father, the emperor Xiaowen (r. 471–99), and his mother, the dowager Wenzhou (d. 494); the emperor and empress in the reliefs are therefore believed to refer to his parents. A figure wearing court garments and holding a tasseled baton leads the procession. He is followed by a smaller figure wearing armor and another who stands before the emperor, holding an incense burner. The trees originally indicated the point at which the procession moved around a corner, from the north to the east wall. Several of the attendants hold lotuses or other flowers and offerings, and the entire procession can be understood as making offerings to the Buddhas in the cave, an act of merit making that would continue in perpetuity and improve the future lives of the participants.

Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

#The Met#Metropolitan Museum of Art#Northern Wei dynasty#Northern and Southern dynasties#6th century#relief#religion#art#art history#Chinese#Binyang Caves#Longmen Grottoes#Henan#Xuanwu era#period dress#stone#limestone#portrait

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jiaxing Civic Center Design by MAD Architects

Jiaxing Civic Center Building by MAD Architects, Chinese Architecture Images, News, Architect

Jiaxing Civic Center Building

11 May 2021

Jiaxing Civic Center by MAD Architects

Design: MAD Architects

Location: Jiaxing, northern Zhejiang province, China

An Embrace of the City – MAD Architects Releases the Design of the Jiaxing Civic Center

MAD Architects, led by Ma Yansong, has released their design for the Jiaxing Civic Center. The scheme marks the latest important public project in Jiaxing City designed by MAD, after their design for the Jiaxing Train Station was unveiled earlier this year.

Holding elegant river views and lush vegetation, the Jiaxing Civic Center is situated along the city’s central axis. The project holds a prominent position; adjacent to the South Lake, a historic lake in the South of Jiaxing, and the Central Park, the largest park in the city. The site also lies next to the Haiyan river channel that connects the two cities of Jiaxing and Haiyan. Spanning approximately 130,000 square meters, the site contains three venues: the Science and Technology Museum, the Women and Children Activity Center, and the Youth Activity Center, forming a total construction area of 180,000 square meters and a site footprint of 72,000 square meters.

“A civic center, first and foremost, must be a place that attracts people; a place where children, youth, seniors, and families are willing to come together on a daily and weekly basis. We have created an undulating ring to serve as a garden-like living room for the city: an embrace.” — Ma Yansong

For the Jiaxing Civic Center, MAD has designed an artistic entity on an urban scale; where architectural forms and landscapes fuse together. With a large circular lawn as the centerpiece, the project is one where both people and buildings can interact and share; forming a more open, intimate, dynamic new urban space.

The center’s three venues are linked together “hand in hand,” enclosed by a circular roof to form a single entity. The organic flow of the lines throughout the project echoes the softness and grace of the ancient canal towns lining the southern banks of the Yangtze River in Eastern China. The central circular lawn that anchors the buildings allows for the large architectural volumes to dissipate and dissolve into the landscape.

Adjacent to the South Lake, the waterfront building sits within the central park, covered with locally produced white ceramic panels. The panels respond to the traditional barrel tile roofs of the local village, while also enhancing the scheme’s economic and energy efficiency. Meanwhile, the project’s floating roof forms a continuous skyline, like a tarp blown by the wind, bringing a soft sense of wrapping to the form. Whether you are on the central lawn, outside the park, or on the building’s links and pathways, the scenery seems to change with your movement.

To maintain the cohesiveness of a single entity, the three venues serving exhibition, education, and amenity functions are all coherently arranged under the curvaceous roof, naturally forming an interdependent group with a flowing line of movement. The spaces for exhibition, theater, education, activity, entertainment, and other uses are organically weaved together to complement one another. By avoiding the wasteful duplication of service spaces, the design offers more space for people and nature, and enhances the building’s energy-saving attributes.

The 6,000-square-meter lawn becomes a new type of urban public space, where every citizen can gather, rest and play, in addition to participating in a variety of activities or visiting exhibitions.

The first floor of the center has connections to the surrounding environment on all sides, through bordering the municipal traffic and wider landscape, or connecting the central lawn with the parklands on the periphery of the building. This semi-open, semi-private space can be used in a variety of ways, whether for daily activities, or as an open-air plaza for large urban cultural events. In addition to the central green space, the scheme contains additional open and intimate spaces connecting people to the outdoors, and to nature.

Among these, the terrace on the second floor of the site creates a 350-meter-long landscape corridor and running path. The public can climb towards the track from the central green space to walk or exercise, or visit the amphitheater and sunken plaza on the east side, before wandering into the parkland forest beyond the center to enjoy the wilderness.

The original trees on the site that have grown to an impressive age are preserved as much as possible, informing the design of the landscape to form a new natural park. In the middle of the green forest are winding paths and passages through the enclosed buildings, where one can walk through the trees and enjoy the riverfront view.

A cascading terrace, facing the central lawn in the interior of the building, acts in a dialogue with the white curved roof. The elements interlock and overlap into multiple semi-outdoor spaces, separated by minimalist floor-to-ceiling glass, blurring the interior and exterior. This is an urban public space for citizens to gather; a fresh, pure land for people to wash away the city’s complex clutter.

Jiaxing has a unique historical status in China. The vision for MAD’s scheme, embracing innovation, coherence, environmental friendliness, openness, and co-sharing, resonates with the historical heritage of this city, making this municipal public building a place that enhances the citizens’ sense of belonging and happiness.

By exploring the relationship between the city, nature, and humanities, MAD aims to create an urban space that is accessible to all, offering natural, equal, and friendly open spaces to everyone in the city. Here, architecture allows citizens to envision a spiritual blueprint of their ideal life in the fast-paced world, and to gain a sense of the promising future to be created through the positive development of the city.

Jiaxing Civic Center has completed its bidding for engineering procurement construction, and is expected to be completed by the end of 2023.

Jiaxing Civic Center China – Building Information

Jiaxing Civic Center Jiaxing, China 2019 – 2023

Typology: Civic, Musuem Site area: 126,740 sqm Building area: approximately 180,000 sqm Above ground: 72,351 sqm Underground: 107,950 sqm Height: 39 m

Principal Partners: Ma Yansong, Dang Qun, Yosuke Hayano Associate Partners: Kin Li, Fu Changrui, Liu Huiying Design Team: Yin Jianfeng, Alessandro Fisalli, Fu Xiaoyi, Chen-Hsiang Chao, He Yiming, Thoufeeq Ahmed, Chen Hao, He Xiaowen, Zhang Yaohui, Guo Xuan, Edgar Navarrete, Claudia Hertrich, Deng Wei, Zhang Xiaomei, Chen Nianhai, Li Cunhao, Sun Feifei, Punnin Sukkasem, Manchi Yeung, Li Yingzhou

Client: Jiaxing Highway Investment Co., Ltd. Executive Architects: East China Architectural Design & Research Institute, Shanghai Municipal Engineering Design Institute (Group) Co., Ltd. Façade consultant: RFR Shanghai Landscape Consultant: Earthasia Design Group, Yong-High Landscape Design Consulting Co.Ltd Interior Design consultant: Shanghai Xian Dai Architectural Decoration & Landscape Design Research Institute CO., Ltd Signage Consultant: Nippon Design Center, Inc. Lighting Consultant: Beijing Sign Lighting Industry Group Traffic Consultant: Shanghai Municipal Engineering Design Institute (Group) Co., Ltd.

Jiaxing Civic Center Design by MAD Architects images / information from MAD

MAD Architects

Location: Nanjing Zendai Himalayas Center, People’s Republic of China

Chinese Building Designs by MAD

Nanjing Zendai Thumb Plaza, Shenzhen image from architects Nanjing Zendai Himalayas Center

Wormhole Library, Haikou, Hainan Province, China image courtesy of architects Wormhole Library

Shenzhen Bay Culture Park, Shenzhen, China image courtesy of architecture office Shenzhen Bay Culture Park

Quzhou Sports Campus, Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China image courtesy of architecture office Quzhou Sports Campus Stadium, Zhejiang Province

Chinese Building Designs

Chinese Architecture

Chinese Architecture News

Nanjing International Youth Cultural Centre, Jiangsu Design: Zaha Hadid Architects photo © Hufton+Crow 2nd Nanjing Youth Olympic Games International Convention Center

Wuhan·SUNAC·1890, Qintai Avenue, Wuhan City Design: Lacime Architects photo : Inter_mountain images Sunac · Wuhan 1890 Building

THE FIELD, Huli District, Xiamen, Fujian, South East China Design: TEAM BLDG, Architects, Shanghai photo : Jonathan Leijonhufvud THE FIELD, Huli District, Xiamen City

Chinese Architecture

Contemporary Architecture in China – architectural selection below:

Hong Kong Architecture Designs – chronological list

Hong Kong Walking Tours – bespoke HK city walks by e-architect

Chinese Buildings

Comments / photos for the Jiaxing Civic Center Design by MAD Architects in China page welcome

The post Jiaxing Civic Center Design by MAD Architects appeared first on e-architect.

0 notes

Video

The Shaolin Temple

The Shaolin Temple is world renowned for its Buddhist, Martial Arts and Traditional Medicine studies and practices. Shaolin Temple was established in 495A.D. at the western foot of Songshan Mountain, 13 kilometers northwest to Dengfeng City, Henan Province. The then-Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-557) had the temple built to accommodate the Indian master Batuo (Buddhabhadra). Shaolin Temple literally means “temple in the thick forests of Shaoshi Mountain”.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Found this question on AskHistorian. I want to hear your take on it.

"To what extent is the Tang Dynasty's greater 'liberalization' for women a product of Eurasian/northern steppe culture?"

The full question is on AskHistorian as I am asking anonymously, I can't send a link, but I hope you can find the full question.

First of all, the Tang dynasty was not some utopia for women. Wu Zetian faced significant misogyny in becoming emperor herself, though classism and not being from the Li clan also played roles. From the words of Empress Zhangsun, we can tell women were still generally expected to be subordinate to men, even if they had greater freedom. But it is true there were influential female figures in early Tang such as Empress Zhangsun, Wu Zetian, Princess Taiping, Empress Wei and Shangguan Wan'er, and that women in general enjoyed greater freedom.

The Tang dynasty borrowed elements from the Sui dynasty which was mostly using the same systems as the Northern Zhou dynasty, although there was some southern influence. The Northern Zhou had reversed many of the cultural reforms of Emperor Xiaowen, and even started giving Han people Xianbei family names. I think the Northern Zhou would likely have had a similar attitude towards women as the Northern Wei, and the attitude of Northern Wei is easier to determine due to more records. And Northern Wei's attitude towards women is complex.