#XCVIII [98]

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

vergil is my sclorbo and i am caring for they

#vergil#xcviii#project soulburst#chara#98 robot#robot 98#undertale au#underlust#au of au#my art#artists on tumblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Listen to this new track by XCVIII [98] - Funny (Official Video)

0 notes

Photo

Wow. Same energy; huh? (and almost 4 years apart from each other’s airdate!)

Tweet version here.

#final space#spoiler#spoilers#major spoiler#major spoilers#samurai jack#samurai jack season 5#samurai jack season five#final space season 3#final space season three#ash graven#change is gonna come#samurai jack episode xcviii#samurai jack episode 98#shave and a haircut#a shave and a haircut#shave#haircut#cartoon network#[adult swim]#cartoon network studios#hanna-barbera cartoons#shadowmachine#olan rogers#genndy tartakovsky#same energy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

amnesia part 98

“I hope you don’t mind home cooking,” Stéphane asked him; Étienne had pulled up a chair to the bar counter so that he could chat with Stéphane, while giving his leg a rest, “I haven’t gotten a chance to use my grandmother’s old recipe book in a while and figured tonight was as good as any a time to use it,” Étienne reflected for a moment and found it strange that under any other circumstance, if Edward would have introduced him to Stéphane while they were still together, he probably would have gotten along with him to a point, “No worries, Edward used to cook a lot from his grandmother’s cookbook as well,” He remembered countless weekend afternoons watching Edward cook, trying to decipher his grandmother’s notes, regaling Étienne with tales of childhood memories and Étienne had felt privileged that his friend and then boyfriend had shared these treasured moments with him, “Do you cook?” It was an honest question, but Étienne actually laughed, “Please, you don’t want to see me in a kitchen – I’m a mess, never got the oven to cooperate the way I wanted it to, no matter how many times my mom, or even Edward tried,” He smiled, recalling the number of times he had tried to make anything and how it always ended in some charred, smoking, blob, “I found alternate ways of cooking – I got really good at tartars, salads of any and every kind, sushi... you should have seen our kitchen – every other appliance that could cook you could have imagined – rice cooker, toaster oven... you name it, we probably had it and it was fine!” Étienne laughed; Edward would joke that whatever new gadget wouldn’t work – that Étienne’s so called oven curse was a ruse, but sure enough, Étienne would be able to use the indoor grill, or whatever it was Edward had found at the store and Edward would shake his head in dismay, “And for some absurd reason, using a barbeque was never a problem – go figure!”

Stéphane laughed and pulled out the roast from the oven – it looked perfect and Étienne’s stomach rumbled, “Here’s a thought, if you don’t hate dinner, how about we do this again and we can cook together? You can make your specialties and I can use the oven,” Étienne thought about it for a moment and then agreed, “Alright, why not, but only if I don’t die from food poisoning,” Stéphane had the decency to look affronted, “Excuse you, this is my grandmother’s renowned pork roast; you’ll be begging for leftovers to bring home!” Stéphane declared and Étienne rolled his eyes teasingly, “Sure, sure, mighty big words those are,” Stéphane said nothing, but the look on his face was enough to let Étienne know that he would probably regret his words – Étienne let Stéphane make a plate for him and waited for his host to be seated before taking a bite; the meat was nice and juicy, warm and tender and the blend of spices was superb on his palette; “Jesus, this is good,” He admitted, covering his mouth – Stéphane beamed from across the table, looking smug, “Shush, don’t look so pleased,” Étienne added cutting up another piece from his dish and stuffing it in his face.

“Jokes put aside though, this is nice,” Étienne quirked an eyebrow at Stéphane, who then clarified, “I mean, I used to cook for my partner all the time – it was a thing we both enjoyed, but then after my breakup I stopped...” Étienne put his fork down and paused, listening to Stéphane’s tale, feeling as though there was more to it and that maybe he hadn’t opened up to someone in a while and had been bottling his feelings up, “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to get personal and I know you’re not interested, that’s not what I was implying – but it’s nice to be able to do this and... not feel so sad, you know?” Stéphane smiled softly at Étienne and took a sip from his glass, maybe to buy himself some time and mull over what he wanted to say, “My relationship may have not ended as tragically as yours, but it still hurts...,” Étienne didn’t like the way Stéphane’s eyes clouded over or how sad he suddenly seemed and so he did the only logical thing he could think of and reached out for Stéphane’s hand, letting him know, through this small gesture, that he understood.

------------

PREVIOUS: XCVII

CURRENT: XCVIII

NEXT: XCIX

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

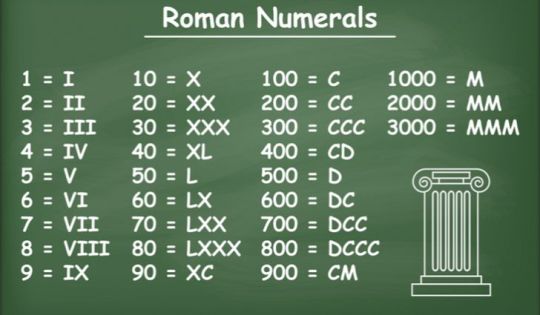

How to type Roman Numerals ?

Overview Roman numerals were developed so that the Romans could easily price different goods and services. Roman numbers were widely used throughout the Roman Empire in everyday life. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, numerals continued to be used throughout Europe up until the 1600's. Roman Numerals Chart 1 I 26 XXVI 51 LI 76 LXXVI 2 II 27 XXVII 52 LII 77 LXXVII 3 III 28 XXVIII 53 LIII 78 LXXVIII 4 IV 29 XXIX 54 LIV 79 LXXIX 5 V 30 XXX 55 LV 80 LXXX 6 VI 31 XXXI 56 LVI 81 LXXXI 7 VII 32 XXXII 57 LVII 82 LXXXII 8 VIII 33 XXXIII 58 LVIII 83 LXXXIII 9 IX 34 XXXIV 59 LIX 84 LXXXIV 10 X 35 XXXV 60 LX 85 LXXXV 11 XI 36 XXXVI 61 LXI 86 LXXXVI 12 XII 37 XXXVII 62 LXII 87 LXXXVII 13 XIII 38 XXXVIII 63 LXIII 88 LXXXVIII 14 XIV 39 XXXIX 64 LXIV 89 LXXXIX 15 XV 40 XL 65 LXV 90 XC 16 XVI 41 XLI 66 LXVI 91 XCI 17 XVII 42 XLII 67 LXVII 92 XCII 18 XVIII 43 XLIII 68 LXVIII 93 XCIII 19 XIX 44 XLIV 69 LXIX 94 XCIV 20 XX 45 XLV 70 LXX 95 XCV 21 XXI 46 XLVI 71 LXXI 96 XCVI 22 XXII 47 XLVII 72 LXXII 97 XCVII 23 XXIII 48 XLVIII 73 LXXIII 98 XCVIII 24 XXIV 49 XLIX 74 LXXIV 99 XCIX 25 XXV 50 L 75 LXXV 100 C Origin of Roman Numerals There were a number of counting systems in the ancient world prior to the creation of Roman numbers. For example, the Etruscans, who lived in central Italy before the Romans, developed their own numeral system with different symbols. Theory 1 A common suggested theory for the origin of the Roman numbers system is that the numerals represent hand signals. The numbers; one, two, three and four are signalled by the equivalent amount of fingers. The number five is represented by the thumb and fingers separated, making a 'V' shape. The numbers; six, seven, eight and nine are represented by one hand signalling a five and the other representing the number 1 through to 4. The number ten is represented by either crossing the thumbs or hands, signalling an 'X' shape. Theory 2 The second theory suggests that Roman numerals originate from notches which would be etched onto tally sticks. Tally sticks had been used for hundreds of years previous to the Romans and were still used up until the 19th century by shepherds across Europe. The numbers one, two, three and four were represented by the equivalent amount of vertical lines. The number five represented by an upside down 'V'. The number was represented by an 'X'. In order to make larger numbers they would use the same rules as numerals did. For example; seven on a tally stick would look like: IIIIVII, when shortened it would look like VII, identical to Roman numbers. Just like the above example the number seventeen, in long form, would look like IIIIVIIIIXIIIIVII, however, this in short form would look like XVII, which is also identical to numerals. Certain Roman numerals; for example, four when written on a tally stick would like this: IIIIV. When the tally was re-written at a later date four could be written as either IIII or IV. As the Roman number system was developed further it adapted the number 50 to be represented by the letter 'L'. Similarly, the number 100 was illustrated by a wide array of symbols, most commonly, represented by the numeral 'I' on top of an 'X'. The numbers 500 and 1000 were represented by a 'V' and 'X' in a circle respectively. As the Roman Empire grew these symbols were replaced with a 'D' (500) and 'M' (1000). The Latin letter M was short for 'mile', which is translated as one-thousand. Introduction Roman numerals are represented by seven different letters: I, V, X, L, C, D and M. Which represent the numbers 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000. These seven letters are used to make thousands of numbers. For example, the Roman numeral for two is written as 'II', just two one's added together. The numeral twelve is written as, XII, which is simply X+ II. If we take this a step further; the number twenty-seven is written as XXVII, which when broken down looks like XX + V + II. Roman numerals are usually written largest to smallest from left to right. However, this is not always the case. The Romans didn’t like four of the same numerals written in a row, so they developed a system of subtraction. The Roman numeral for three is written as ‘III’, however, the numeral for four is not ‘IIII’. Instead we use the subtractive principle. The number four is written as ‘IV’, the numerals for one and five. Because the one is before the five we subtract it making four. The same principle applies to the number nine, which is written as ‘IX’. There are six instances where subtraction is used: ⋅ I can be placed before V (5) and X (10) to make 4 and 9.�� ⋅ X can be placed before L (50) and C (100) to make 40 and 90. ⋅ C can be placed before D (500) and M (1000) to make 400 and 900. The number 1994 is a great example of these rules. It is represented by the Roman numerals MCMXCIV. If we break it down then; M = 1,000, CM = 900, XC = 90 and IV = 4. Examples 1). In order to make the number 16 we must take the numerals for 10 (X), 5 (V) and 1 (I), thus making XVI. 2). In order to make the number 27 we must take the numerals for 20 (XX), 5 (V) and 2 (II), thus making XXVII. 3). In order to make the number 32 we must take the numerals for 30 (XXX) and 2 (II), thus making XXXII. 4). In order to make the number 58 we must take the numerals for 50 (L), 5 (V) and 3 (III), thus making LVIII. 5). In order to make the number 183 we must take the numerals for 100 (C), 50 (L), 30 (XXX) and 3 (III), thus making CLXXXIII. 6). In order to make the number 555 we must take the numerals for 500 (D), 50 (L) and 5 (V), thus making DLV. 7). In order to make the number 1582 we must take the numerals for 1000 (M), 500 (D), 50 (L), 30 (XXX) and 2 (II), thus making MDLXXXII. Years and Dates To write the year in Roman numerals we need to make larger numbers. Let’s look at a few examples. Years in the 21st century are quite simple. First, we start off with MM(1000 + 1000) and then we add on the appropriate amount. So, if we want 2020 in numerals we start with MM (2000) and add XX (20) to make MMXX. Years from the 20th century are simple as well. We start off with the Roman numerals for 1900 (MCM) and add on the appropriate amount from here. So, for example, 1985 would be written as MCM (1900) + LXXX (80) + V (5) = MCMLXXXV. Large Roman Numerals Because the largest letter used is M and we can only stack three of the same numeral together the largest number you can make in Roman numerals is 3999 (MMMCMXCIX). However, it is possible to write numbers higher that 3999 in Roman numerals. In this system, you draw a line across the top of the numeral to multiply it by 1000. For example, the Roman numeral for 5000 (5 x 1000) is written as: . Similarly, 1,000,000 (1000 x 1000) is written as . If we want to write 1,550,000 in Roman numerals it would look like this: . If we break it down the numeral for 1,000,000 is , the numeral for 500,000 is and the numeral for 50,000 is . Zero and Fractions Fractions were often used in currency. The most common fractions used were twelfths and halves. A twelfth is represented by a single dot '•', which is known as an 'uncia'. A half is represented by the Latin letter 'S', which is short for semis. This isn't really a rule, but interestingly, there is no numeral to represent zero. This is because the system of Roman numbers was developed as a means of trading and there was no need for a numeral to represent zero. Instead they would have used the Latin word 'nulla' which means zero. Adding and Subtracting As there is no Roman numeral for zero it makes advanced mathematics quite difficult. It is possible to easily use numerals for addition and subtraction. However, multiplication and division are far too impractical. Addition When we are adding with numerals it is important that we ignore the subtractive principle. For example, the number four is written as IIIIrather than IV. Let’s use a simple example: to add IX and XI we must first change the IX in to VIIII. Next, we arrange the numerals in order from biggest to smallest, which gives us XVIIIII. The next step is to simplify the IIIII to V which gives us XVV, which can be further simplified to XX or 20. Simple! Subtraction When we subtract numerals we also ignore the subtractive principle. Here’s the sum: CCLXXXVIII - CCLXXII. The first step is to write it out, as seen in the image below. Secondly, we scratch out all the pairs of numerals. This leaves us with a very simple sum to calculate: XVIII – Iwhich is equal to XVII or 17. Modern Uses of Roman Numerals Roman numerals can still be seen in the modern day, in fact they are all over the place! I. Roman numerals are used to refer to kings, queens, emperors and popes. For example; Henry VIII of England and Louis XVI of France. II. Many competitions such as the Olympic Games and the Super Bowl use numerals to represent how many times the event has been held. For example, the Olympic games in Tokyo (2020) will be the thirty-second time the event will be held and will be represented by the numerals XXXII. III. Numerals can often be found on buildings and monuments to signify the year of construction. For example, a building built in 2004 may have the numerals MMIVengraved on it. IV. Many movies use numerals to illustrate the year the film was made. For example, 'Gladiator' was copyrighted in the year 2000 so it has the numerals MMat the end of its credits. Another example is the film 'Spartacus' which was copyrighted in 1960 and has MCMLX at the end of its credits. V. Many clocks also use numerals to represent the hours. Roman numerals can be found in many other places; the list goes on and on. It is used at the start of books to number pages, to label sections and sub-sections in legislation and contracts, to reference wars (WWI & WWII). Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

Self-portrait XCVIII Image info: "Self-portrait 98" Italy, Feb. 2016 © Massimo S. Volonté

#Autoritratto#Fotografia#fotografo milano#massimovolontefotografo#Photography#postaday#Self-portrait

0 notes

Video

youtube

Check out this new song and film by XCVIII [98] - Sophia (Official Video)

0 notes

Text

Project Soulburst's version of 98 Robot. We'll see if he sticks.

Current info on XCVIII:

Male; he/him

He's convinced that the 4 main lab workers are part of a Five-Man Band, with him as The Lancer. However, he can't decide on a definitive rival, typically swapping between Fizz and Vergil.

Somehow, Glycerin was able to program him some magic powers. He typically uses these powers to form a magic lance - he is a lancer, after all!

1 note

·

View note