#World's Columbian Exhibition

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Menu Monday: On June 19, 1893, Princeton student Emory Leyden Ford (Class of 1896) ate at the Golden Door Cafe and Roof Garden at Chicago’s Transportation Building and pasted the menu from the trip in his scrapbook. The Golden Door was how visitors were welcomed to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition. Princeton had its own exhibition booth at the fair. This $1 meal would be about $35 today.

Scrapbook Collection (AC026), Box 199

The entire Menu Monday series

#1890s#Chicago#menu#MenuMonday#Princeton#World's Fair#World's Columbian Exhibition#1893 World's Fair#Class of 1896

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

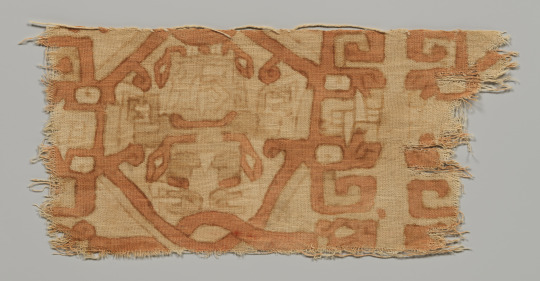

In my research today I found this textile fragment in the Met Museum's collections:

Interesting things about it:

It's coloured with iron earth pigments

It's made of cotton

It's from Peru

From the THIRD OR FOURTH CENTURY BCE

This so shook my expectations of what-where-when that I fell down a rabbit hole and discovered that

Cotton was independently domesticated in the Old World (Asia and Africa) and New World (South and Central America) long before the Columbian Exchange, and

The variety of cotton currently marketed as "Egyptian Cotton" (Gossypium barbadense) is generally grown in Egypt, but it's a cultivar that was developed roughly three thousand years ago in SOUTH AMERICA. Like... Ecuador-region.

(The cotton that originated around Egypt, Gossypium herbaceum, is a perennial shrub that still grows wild, but has largely been replaced by New World varieties for commercial purposes.)

I forget if I posted before about how amazing pre-Columbian lace in South America was? You may not know: I fucking love lace. And that's just part of it. I found a really cool online museum exhibit from Peru that gives a quick overview of how huge the field is.

I found all of this as a side-tangent from cochineal (itself a whole tangent from Slavic folk embroidery), because the world is so enormous and splendid and complicated. Currently debating whether or not to spend an audiobook credit on A Perfect Red by Amy Butler Greenfield.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

MAX PIETSCHMANN - POLYPHEMUS' FISH CATCH, 1892

The painting illustrates Polyphemus, the one-eyed giant son of Poseidon, known from Homer's "Odyssey." In this artwork, Polyphemus is portrayed not in his typical role of capturing and eating Odysseus' men but rather in a different mythological context where he is involved in "fishing."

Polyphemus is shown holding a red-haired woman aloft, suggesting he has just "caught" her, much like one would hold up a fish. This scene alludes to a different aspect of Polyphemus' myth where he is known for his unrequited love for the sea nymph Galatea. However, in Pietschmann's version, this is depicted with a humorous twist, where Polyphemus treats the woman more like a catch of the day rather than an object of affection.

The backdrop is a scenic coastal environment, likely near the sea where Polyphemus lives, with other sea maidens sitting on the rocks, observing the scene. These figures appear nonchalant, suggesting they might be accustomed to such events and probably see Polyphemus' action as an inevitable part of their existence.

After its initial acclaim in the 1890s, including its exhibition at the World's Columbian Exposition, the painting's whereabouts became unclear. Over the years, it slipped into obscurity, with only reproductions available. The original had been lost in private hands without public knowledge. In 2020, an individual in Dresden was sorting through an old attic when they stumbled upon the canvas. The painting was rolled up and covered in dust, indicating it had been stored away for a considerable time without recognition of its value. Following the confirmation of its authenticity, the painting was put up for auction.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Check out Will Do Magic for Small Change by Andrea Hairston for an introspective historical fantasy full alien science and earthbound magic!

Letter from the author below the readmore ��🖊️

Will Do Magic For Small Change is about theatre, physics, and bold girls...

who want to live and love out loud and on stage when folks would rather they fade to black!

I teach college theatre, and my students have for forty years complained about the play selection and casting process that cuts them out of possibilities. They were too fat, too black, brown, Asian, or queer, so directors never cast them, never looked for plays that featured roles for them, never offered stories of their lives to our community. They were too something to be worthy of art. I brought this long history up (for the nth time) in a faculty meeting twelve years ago and someone yelled at me, history doesn’t matter—as if there was just one history and we all knew it and it was gone anyway. Maybe those students couldn’t act and that’s why they never got cast. They were mediocre and wanted to hide behind being fat, brown, Asian, or queer! We could all be mediocre, but some folks go into audition knowing that they are who the director / playwright / producer has in mind and others have to wonder, can they see me as a full human being. Would an audience? And if nobody believes your story on stage, what does that mean for folks believing in your life? So I decided to write about Cinnamon Jones and her friends and their search for who to be in a world that can’t see them.

I’d been reading all I could about Dahomean warrior women who supposedly made an appearance at the Columbian World Exposition in Chicago. Newspaper reports from 1893 characterized the performers in the Dahomey village exhibit as 'horrifying,' 'supremely hideous,' and 'a barbaric spectacle.' Photos featured bare-breasted women with hatchets and knives looking bored. No one interviewed the women. No one asked them to tell their stories. In my previous novel, Redwood and Wildfire, the main characters run into Dahomean warrior women strolling the fairgrounds in colorful headdresses, pounds of beaded jewelry, and woven fabrics that dance in the wind. I asked myself, who are these women? In Will Do Magic a story-gathering alien lands in Dahomey, comes to know the world starting with Dahomey as normal. The story the alien tells on the warrior women might not be the story they’d tell on themselves, but it offers Cinnamon a history to inspire her future.

— Andrea Hairston

269 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Norse in America: Fact and Fiction

The idea that it was the Norse who discovered America first emerged in the late 18th century, long before there was any public awareness of the sagas on which such claims were based. In the course of the 19th century, evidence for a Norse presence was discovered in what is now the United States. This evidence, in the form of inscriptions and Norse artefacts, generally appeared in areas of Scandinavian settlement, and advocates of the authenticity of this evidence tended to be of Scandinavian descent.

Public awareness of the idea of a Norse discovery of America prior to Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506) broadened with the publication by Rasmus Anderson of America not discovered by Columbus in 1874. This book lent powerful support both to the historic contention that the Norse visited New England repeatedly from the 10th to the 14th centuries and to the Teutonic ancestral link between the Norse and the New England cultural elite known (in the memorable phrase of Oliver Wendell Holmes) as "the Brahmin caste of New England".

The Viking

The high-water mark of the Norse discovery hypothesis came in 1893, three years after the 9th-century Gokstad ship (now in the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo) had been found in a burial mound on Kristianiafjord (now Oslofjord). The quatercentenary of Columbus' first voyage was marked across America in 1892, and the following year the World's Columbian Exposition was mounted in Chicago to celebrate Columbus' arrival. It was agreed that the Norwegian contribution would be a reconstruction of the Gokstad ship, which would be sailed across the Atlantic (to prove that such a ship was capable of the voyage) to make landfall in New London (Connecticut) and New York before making its way to Chicago, where it would be an exhibit at the Exposition.

The ship was certainly capable of such a voyage: although it lacked thwarts, it was very strong, and it could be powered by oar or sail. Funding was raised in Norway and from Scandinavians in America. On 30 April the Viking (as the replica was called) sailed from Bergen under the command of the newspaper publisher Magnus Andersen, and 22 days later it reached the shores of America. The American welcome was tumultuous, but not entirely without incident. Anderson's account was published in Norwegian (Vikingefærden, i.e. "Viking expedition") but not in English, and so was never tested against the recollections of Americans who were present; there is no reason to think it unreliable, but it does represent a particular perspective.

This article is a book excerpt

Continue reading...

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna M. Mangin invented the pastry fork in 1891.

The utensil was used to mix dough for pie crusts, cookies, butter and flour pastries without needing to mix the ingredients by hand. The fork was also used to beat eggs, mash potatoes, and prepare salad dressings. Mangin was awarded a patent on March 1, 1892, for the pastry fork for mixing pastry dough

PATENT PASTRY-FORK.

SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 470,005, dated March 1, 1892.

Application filed July '7, 1891. Serial No. 398,705. (No model.)

With this invention, Mangin paved the way for future cooking gadgets to shorten cooking durations and alleviate the physical strain of kneading, mixing, and mashing by hand.

In 1893, Mangin's Pastry Fork displayed the ingenuity of African American inventors and the tenacity of African American women at the World's Columbian Exposition. Held in Chicago, Illinois, people of color and women were initially denied opportunities to participate in exhibits.

After repeated demands for inclusion a limited number of non-white exhibits including

Mangin's Pastry Fork were allowed. Although her invention occupied only a small corner on the second floor, a writer on female inventions noticed the kitchen wonder and called it "the only thing of its kind at the patent's office." #blackhistory

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Egg of Columbus, a device exhibited in the Westinghouse display at the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition to explain the rotating magnetic field that drove the new alternating current induction motors designed by inventor Nikola Tesla.

Free energy is present everywhere in unlimited quantities, and yet we are still paying for it. 🤔

#pay attention#educate yourselves#educate yourself#knowledge is power#reeducate yourself#reeducate yourselves#think for yourself#think for yourselves#do your homework#think about it#do some research#do your own research#do your research#question everything#ask yourself questions#free energy

395 notes

·

View notes

Text

"What do you mean you remember that conversation?? I was referring to a hallucination brought on by the hunger strike."

"I remember it, sir, I was reading your thesis-"

"My THESIS???? How did you get my thesis???? Nevermind that, I was nowhere near New York!"

"Yes sir, but I had a bad feeling about Arkwright that I couldn't put together on my own, then you started talking about foundations-"

"Why on earth would your delusion and my hallucination be the same?? Really, Will Henry, were-"

"'-you dropped on your head as a babe? Did your mother suffer an accident as she carried you in her womb? An accident while milking the irascible family cow, perhaps?' You said that, too, sir."

Warthrop:

"...I did say that"

I like to think that bit in Isle of Blood where Will has a mental conversation with Warthrop is an actual minor psychic event. Like Warthrop all weak and shit from the hunger strike just came over to mentally torment Will Henry for old times sake

#the monstrumologist#pellinore warthrop#will henry#isle of blood#also im reading the devil in the white city and its set in like THE SAME year as all this. warthrop went to india#so that Yancey wouldn't have to include H H Holmes the american serial killer#which is a damn shame really the world columbian exhibition would have been right up his alley. imagine monsters in the white city#fuck it von helrung takes will henry on the Prototype™ First Ever™ Ferris™ wheel#i realize now halfway into this half-baked fantasy that the expo was in 1893 not 1890 and they very well could have gone anyways#and yancey just didn't include it#OUT OF SPITE#you BASTARD

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julio Galán (1958 - 2006) was a Mexican painter known for his Neo-Expressionist works filled with themes related to pre-Columbian cultures, homosexuality and Roman Catholicism. His paintings were influenced by the self-analyzing themes found in the works of Frida Kahlo as well as his international peers Sigmar Polke and Francesco Clemente. Born on December 5, 1958 in Múzquiz, Mexico, he went on to study architecture at the University of Monterrey. Before finishing his degree, Galán left university to pursue his interest in painting, and moved to New York in 1984. Here, the artist’s work was discovered by Andy Warhol during his first show in New York at Art Mart Gallery. Warhol subsequently printed some of Galán’s works in Interview magazine, propelling him to success. By 1989, Gálan had become one of the most popular Mexican painters in the art world, and went on to be included in exhibitions at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and The Museum of Modern Art in New York. The artist died at the age of 46 on August 4, 2006 in Zacatecas, Mexico.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seattle Great Wheel, 2024.

A large ferris wheel has become something of an urban cliche. Originally developed as an amusement ride for the World's Columbian Exhibition in 1890's Chicago, for almost a century the large wheels were limited to a few fairs and amusement parks. The largest of the old ones still operating is the Wiener Riesenrad at the Prater, famed for its role in "The Third Man," a classic film noir.

Several large wheels were built in Japan just before the millennium, but that year saw the opening of the most famous of the new ones, the London Eye cantilevered over the Thames, an example of audacious engineering. Now large wheels are to be found in a many cities in the US and elsewhere. Some of them, like the London Eye, make sense as both sightseeing and entertainment with expansive views over a mostly low-rise urban landscape. The Seattle wheel offers little such enticement. On the waterfront near sea level, at 53.3 m it is dwarfed by the hills on which the city is constructed as well as by the motley assortment of high rises in the nearby Central Business District. For sightseeing it is all but worthless. Much better overviews of the city can be gotten at various places on land or from the Space Needle and a few of the high rises with upper decks open to the public. I guess it does offer a small thrill as part of the ride is over the water of Elliott Bay. Recommendation to tourists -- save your $20 and walk up Pike Street just across I- 5 to Plymouth Pillars Park, a free viewpoint of the CBD.

#urban landscape#ferris wheels#seattle great wheel#seattle#washington state#2024#photographers on tumblr#pnw#pacific northwest

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hopes for Loki Season 2

Really hope that Loki season 2 goes a little into the history of the time periods and places they're going, because they may accidentally stumble into one of my hyper fixations.

Because these guys are at the World's Columbian Exhibition, also known as the World's Fair.

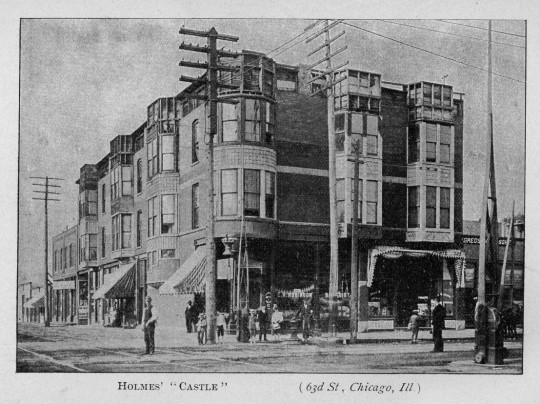

And I happen to know about the World Fair, because it was the ground for serial killer H. H. Holmes, who used the World Fair to target people who came to Chicago to see it. He had a hotel which he literally named The World Fair Hotel to get people to stay there during their visits, and though many accounts are likely exaggerated, it was considered a "Murder Castle". Different accounts describe it as maze-like, with hidden rooms, gas chambers, peepholes to watch guests, and a furnace in the basement where Holmes would burn the bodies of his victims. However, little of this is known as absolute fact, as Holmes was dishonest during his trial and confession, and the hotel was burned by an unknown arsonist and a post office was built in its place.

There's a chance we get something similar to the D.B. Cooper scene in season one where it's a little history lesson for the audience about a not widely known and unexplained crime. I'm really hoping that either Mobius and Loki actually meet H. H. Holmes, or there's a scene where Mobius talks about him a little and is like "okay here's really what happened."

I could go into heavy detail about this man and his crime spree and just how the whole case was equal parts horrific and bizarre, but we'd be here for hours. If you want to know more, here's a quick article I found that covers the case pretty well.

In any case, hyped for season two. Whether or not they go into detail about this specific person, it looks like history nerds are going to be fed well this season with all the time travel that's actually centered on Earth in the past.

#loki#loki series#loki season 2#loki season two#loki series season 2#loki series season two#marvel#marvel loki#loki marvel

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

it seems like everyone at the MSI has an informal role that goes along with their role as an exhibit. Pioneer is guests' introduction to the museum, an example of what they can expect to see inside as well as informally answering any questions they may have. 727 is an example of how far aviation technology has improved alongside looking after all the other planes, etc. does 999 have an informal role alongside her place in the museum as an example of steam technology?

So it sounds like you're kinda talking about when an engine gives themselves a extra job or falls into one by virtue of ability and presence. 999's had the longest working career out of the entire roster and has done so many jobs over the course of it that she's smart enough not to give herself busy work. She's enjoying her retirement, thank you very much. She'll not be taking it upon herself to assume more than she's been asked like some engines around here do.

That said...

In a passive sense, being a relic of the Columbian Exposition, 999 also serves to relate the museum's greater history back to Chicago's first World's Fair. She's a very tidy exhibit for the MSI to have because, despite being a New Yorker, her early history touches theirs and the rest of it runs parallel to Pioneer's in very satisfying ways. She was - and is - a mark of how far we've come and how far we could go yet.

She's also largely responsible for starting the trips out to the IRM and vice versa. With 2903's move to Union in the early 90's, 999 was the one who proposed that she ought to be allowed to visit him once she'd returned from her restoration. What would even be the point of having been restored if he couldn't see it?

Luckily, around this same time, Pilot had then had a few successful off-property excursions too, giving everyone some peace of mind about the idea of engines visiting other trusted locations.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

863!!!

You got this!! I’m cheering you on from all the way over here

ooh you got a good one i like this topic.

[blah blah worlds fairs as part of the greater museological institution, also part of imperialism blah blah cultural display.] The 1893 Chicago World's Fair, also known as the World's Columbian Exposition, was a world's fair commemorating the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas. Like many previous and subsequent world's fairs, it used cultural display to champion ethnographic, white supremacist, and imperialist ideology.

blah blah. the columbian expo is a fantastic example because of the sheer breadth of concepts it demonstrates really handily. I'll expand on these:

the use of spatiality in conveying meaning

the use of monumentalism and connection to white supremacy

the use of cultural display in imperialism

how context in museological display informs how an item or display is viewed and understood -- both that of the greater museological institution an item is displayed within, as well as the context of immediately surrounding items/displays

the capacity for exhibitions to inform public opinion, and its capacity as propaganda

the complexities of self representation within colonial contexts

The United States, similarly to previous hosts of such fairs, took the opportunity to emphasise their imperialist feats and presumed cultural superiority. This was done in large part through the use of spatiality, or the physical construction of the exposition: [expand on spatiality] specifically, the “Midway Plaisance” and the “White City”. The Midway Plaisance was a two-mile long road, lined with ethnographic displays “representing” various cultures and races, and ending with the White City. Where a culture’s display was placed along the path was determined by racist, pseudoscientific criteria that assessed their perceived level of evolutionary progress based on factors such as skin colour, participation in capitalism, and ways of living. etc etc

"ceci is going to fail zir thesis" ask game ! give me a number from 1 to 1400 2200 or a topic from a previous ask and i have to write something

blanket disclaimer that everything i say in these is divorced from the much larger context of my thesis. Greater nuance, context, and explanations for how certain words are being defined within the thesis are likely excluded here.

#sorry this one is kinda piecemeal but a) this is enough to serve as a guidline to expand on#and b) im trying to not let myself spend too much time on it if i cant write it quickly then make a note to expand and move on yk#ty for ur support <3 xoxo#ask#theatretechgal#ceci says stuff#div 3#ask game#ceci vs academia

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

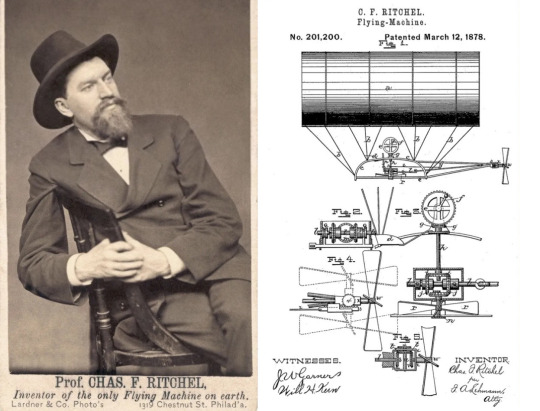

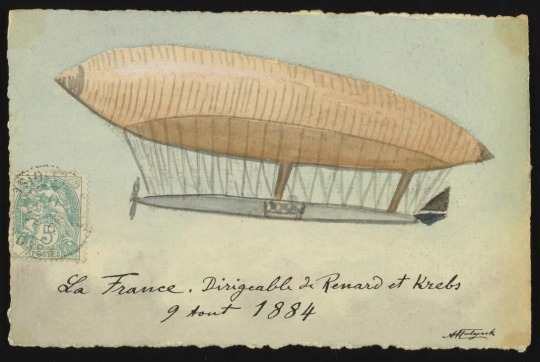

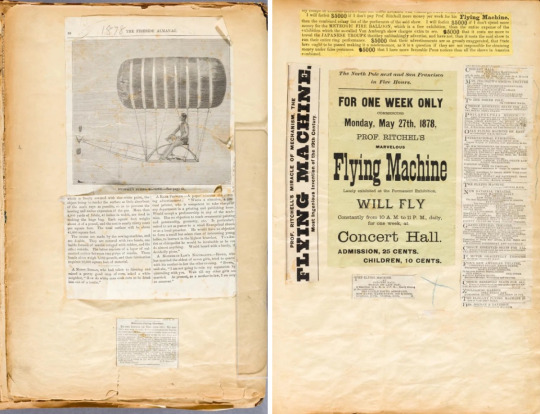

Twenty-Five Years Before The Wright Brothers Took To The Skies, This Flying Machine Captivated America

First Exhibited in 1878, Charles F. Ritchel’s Dirigible Was About As Wacky, Dangerous and Impractical as Any Airship Ever Launched

— June 11, 2024 | Erik Ofgang

“When I Was Making It, People Laughed at Me a Good Deal,” Charles F. Ritchel Later Said. “But Do They Did at Noah When He Built the Ark.” Illustration by Meilan Solly/Images via Wikimedia Commons under public domain, Newspapers.com

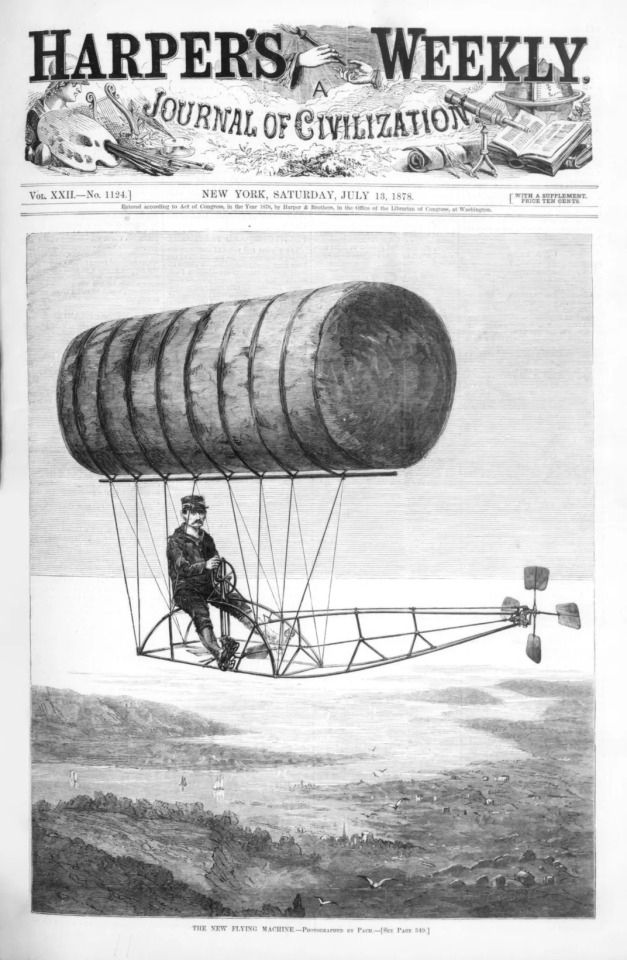

Charles F. Ritchel’s Flying Machine Made a Sound Like a Buzzsaw as its pilot turned a hand crank to spin its propeller. It was June 12, 1878, and a huge crowd, by some accounts measuring in the thousands, had gathered at a baseball field in Hartford, Connecticut. The spectators had each paid 15 cents for a chance to witness history.

The flying machine—if one could really call it that—was an unsightly jumble of mechanical parts. It consisted of a 25-foot-long, 12-foot-wide canvas cylinder filled with hydrogen and bound to a rod. From this contraption hung a framework of steel and brass rods that the Philadelphia Times likened to “the skeleton of a boat.” The aeronaut would sit on this framework as though it were a bicycle, controlling the craft with foot pedals and a hand crank that turned a four-bladed propeller.

The device did not inspire confidence.

“When I was making it, people laughed at me a good deal,” Ritchel later said. “But so they did at Noah when he built the ark.”

A self-described “professor,” Ritchel was the inventor of such wacky, weird and wild creations that a recounting of his career reads as though it were torn from the pages of a Jules Verne novel. Supposedly friends with both P.T. Barnum and Thomas Edison, Ritchel for a time made a living working for a mechanical toy company in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he designed talking dolls, model trains and other playthings. But he was more than just a toymaker.

Left: Charles F. Ritchel filed more than 150 patents over his lifetime. Right: Ritchel's 1878 patent for his flying machine — Photographs: Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

Some years after the flying machine demonstration, the inventor proposed an ambitious attraction for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair): a “telescope tower” that would rival France’s Eiffel Tower. The design consisted of a 500-foot-wide base topped by multiple nested structures that rose up over the course of several hours, eventually reaching a height of about 1,000 feet. After this proposal was rejected, Ritchel launched a campaign to raise funds to build a life-size automaton of Christopher Columbus, which the Chicago Tribune reported would speak more than 1,000 phrases in a human-like voice, rather than the “far-away, metallic sounds produced by a phonograph.”

By the mid-1880s, Ritchel claimed to have filed more than 150 patents. Not all of them were fun. He invented more efficient ways to kill mosquitos and cockroaches, a James Bond-esque belt that assassins could use to inject poison into their targets, and a gas bomb for use in land or naval warfare.

Yet never in his career was his quirk-forward blend of genius and foolishness more apparent than on that June day in Hartford. Because the balance of weight and equipment was so delicate, Ritchel was too heavy to fly the craft. Instead, he employed pilot Mark W. Quinlan, who tipped the scale at just 96 pounds. Quinlan was a 27-year-old machinist and native of Philadelphia, but little else is known about him. The record, however, is crystal clear on one count: Quinlan was very, very brave.

When preparations for the craft were complete, the crowd watched in eager anticipation as Quinlan boarded the so-called pilot’s seat. The airship rose 50 feet, then 100 feet, then 200 feet. Such a sight was uncommon but not unheard of at the time. The real question was: Once the craft was in the air, could it be controlled?

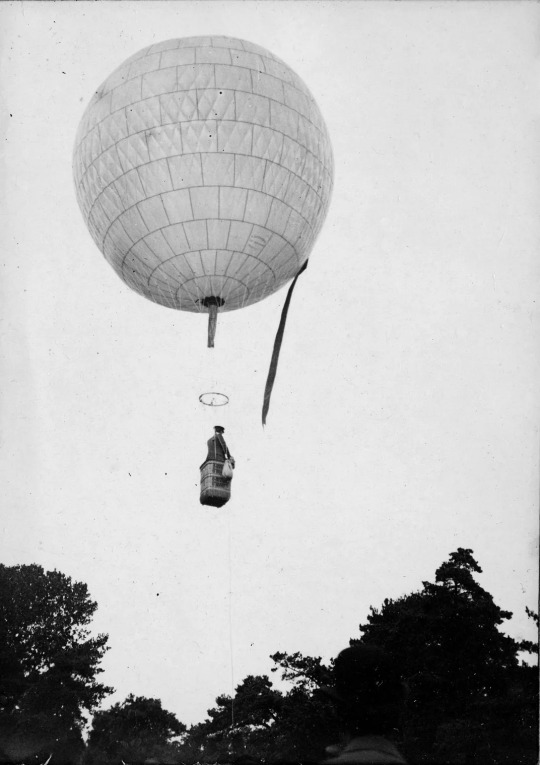

The first heavier-than-air flight (in which airflow over a surface like a plane wing creates aerodynamic lift) only took place in 1903, when the Wright Brothers conducted their famous flight in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. But by the late 19th century, flying via lighter-than-air gases was already close to 100 years old. (This method involves heating the air inside of a balloon to make it less dense, leading it to rise, or filling the balloon with a low-density gas such as helium or hydrogen.) On November 21, 1783, Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d’Arlandes completed the first crewed, untethered hot-air balloon flight, passing over Paris on a craft built by the Montgolfier brothers. Later, balloons were used for reconnaissance during the French Revolutionary Wars and the American Civil War.

A drawing of the Montgolfier brothers' hot-air balloon Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

But free-floating balloons were, and still are, at the mercy of the winds. While balloon aeronauts can achieve limited control by changing altitude and attempting to catch different currents, they can’t easily return to the spot where they took off from, which is why even today, they have teams following them on the ground. Mid-1800s aviation enthusiasts dreamed of fixing this problem, which led to the development of dirigibles—powered, steerable airships that were inflated with lighter-than-air gases. (The word dirigible comes from the French word diriger, “to steer”; contrary to popular belief, the term, which is synonymous with airship, is not derived from the word “rigid.”) While some early aeronauts successfully steered dirigibles, none of these rudimentary airships could truly go against the wind or provide a controlled-enough flight to take off and land at the same point consistently.

In 1878, Ritchel was unaware of anyone who had successfully taken off in a dirigible and landed at the same spot. He hoped to change that with his baseball field demonstration. A month earlier, Ritchel had exhibited the airship’s capabilities during indoor flights at the Philadelphia Main Exhibition Hall, a massive structure built for that city’s 1876 Centennial Exposition. But there is no wind indoors, and the true test of his device would have to be performed outdoors.

After rising into the air, Quinlan managed to steer the craft out over the Connecticut River. To onlookers, it was clear that the aeronaut was in control. But as he flew, the wind picked up, and it began to look like a storm was gathering. To avoid getting caught in the poor weather and facing an almost-certain disaster, Quinlan steered the craft back toward the field, cutting through the “teeth of the wind until directly over the ball ground whence it had ascended, and then alighted within a few feet of the point from which it had started,” as the New York Sun reported.

Ritchel's dirigible, as seen on the July 13, 1878, cover of Harper's Weekly Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

The act was hailed far and wide as a milestone. An illustration of the impressive-looking flying machine was featured on the cover of Harper’s Weekly.

“The great problem which inventors of flying machines have always before them is the arrangement by which they shall be able to propel their frail vessels in the face of an adverse current,” the magazine noted. “Until this end shall have been achieved, there will be little practical value to any invention of the kind. In Professor Ritchel’s machine, however, the difficulty has been in a great measure overcome.”

Across the country, observers hailed Ritchel’s odd but impressive milestone in flight. In the years and decades that followed, this achievement was forgotten by almost all except a select group of aviation historians.

Wikipedia incorrectly lists the flight of the French army dirigible La France as the first roundtrip dirigible flight. But this event took place six years after Ritchel’s Hartford demonstration, in August 1884. Why has a flight so seemingly monumental in its time been relegated to the dustbin of history?

Given his eccentric nature and creativity, it’s easy to root for Ritchel and think of him as a Nikola Tesla-like genius robbed of his rightful place in history. The reality of why his feat was forgotten is more complicated. As Tom Crouch, an emeritus curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, says, it’s possible Ritchel’s craft was the first to complete a round-trip dirigible flight. But other aircraft in existence at the time probably could have accomplished the same feat in favorable conditions. “La France made the first serious round-trip,” Crouch says.

Additionally, while Ritchel’s machine worked to a point, it wasn’t a pathway to more advanced dirigibles. Richard DeLuca, author of Paved Roads & Public Money: Connecticut Transportation in the Age of Internal Combustion, points out that the hand-cranked nature of Ritchel’s craft made it nearly impossible to operate with any kind of wind. “On the first day, he got away with it and directed the ship out and over the river and back to where he started, and that was quite an accomplishment,” DeLuca says. “But the conditions were just right for him to do that.”

Dan Grossman, an aviation historian at the University of Washington, has never come across evidence that any later pioneers of more advanced dirigible flights were influenced by Ritchel. “There are a lot of firsts in history that got forgotten because they never led to a second,” Grossman says.

An artist's depiction of the La France airship Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

The day after their first successful public outdoor flight in Hartford, Quinlan and Ritchel tried again at that same ballfield. This time, the weather was less cooperative, and the wind came in sharp gusts. Still, the pair persisted in their attempt. “Little Quinlan, even if he does only weigh 96 pounds, has confidence and nerve enough to go up in a gale,” the Sun reported. Up he went about 200 feet, but this time, the wind carried him away with more force. Quinlan was “seen throwing his vertical fan into gear, and by its aid, the aerial ship turned around, pointing its head in whatever direction he chose to give it.” Although he could move the ship about, “he could not make any headway against the strong wind.”

Quinlan descended about 100 feet, trying to catch a different current, but the wind still pushed him away from the ballfield. He raised the craft, this time going higher than 200 feet, but still couldn’t overcome the wind and was soon swept off toward New Haven, vanishing from sight like some real-world Wizard of Oz.

Eventually, Quinlan safely brought the airship down in Newington, about five miles away from Hartford. The inventor and his pilot were unfazed by this setback. They held more public exhibitions that year with a mix of success and failure—including an incident that nearly cost Quinlan his life. During a July 4 exhibition in Boston, the machine malfunctioned and continued to rise, soaring to what the Boston Globe estimated to be 2,000 feet. Quinlan couldn’t get the propeller to work, and the craft continued to rise, reaching as high as 3,000 feet.

youtube

Terrified but quick-thinking, Quinlan tied his wrist and ankle to the craft and swung out of his seat to fix the propeller, using a jack-knife he happened to have on him as a makeshift tool. The daring midair repairs worked, and the craft gradually descended. Quinlan landed in Massachusetts, 44 miles from his starting destination, after a 1-hour, 20-minute flight.

Per Grossman, the human-powered method Ritchel attempted to utilize was doomed from the start. “In the absence of an internal combustion engine, there really was no control of lighter-than-air flight,” he says.

Ritchel stubbornly refused to consider powering dirigibles with engines and did not foresee how powerful a better-designed aircraft truly could be.

“I have overcome the fatal objection of which has always been made to the practicability of aerial navigation—that is, I have made a machine that can be steered,” Ritchel told a reporter in July 1878. “I claim no more. I have never pretended that a balloon can be made to go against the wind, and I am sure it never could. It is as ridiculous as a perpetual motion machine, and the latter will be invented just as soon as the former.”

Left: A page from Ritchel's ballooning scrapbook National Air and Space Museum Archives. Right: The scrapbook covers the years 1878 to 1901. Photographs: National Air and Space Museum Archives

Even so, Ritchel was influential in his own way. “He was one of the first to really come up with the notion of a little one-man, bicycle-powered airship, and those things were around into the early 20th century,” says Crouch. After Ritchel, other daring inventors launched similar pedal-powered airships. Carl Myers, for example, held demonstrations of a device he called the “Sky-Cycle” in the 1890s.

Ritchel stands as one of the fascinating early aeronauts whose work blurred the line between science and the sideshow. “I refer to them as aerial showmen, these guys who came up with the notion of making money [by] thrilling people [with] their exploits in the air,” Crouch says.

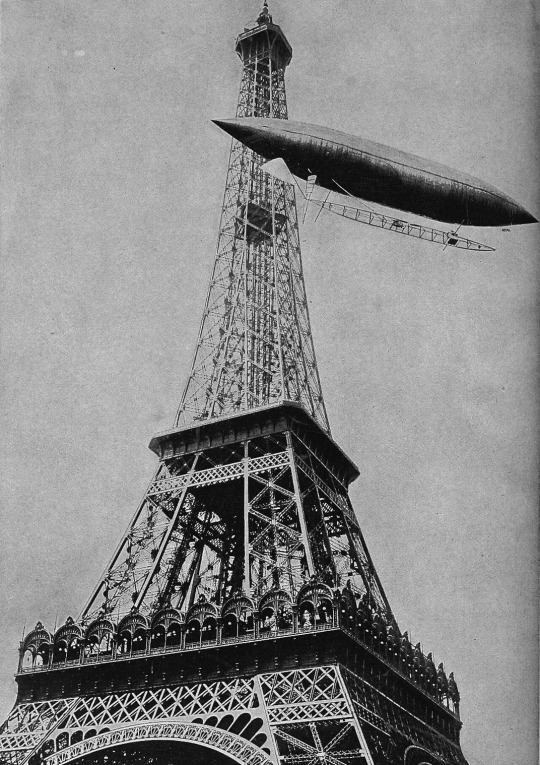

According to Crouch’s 1983 book, The Eagle Aloft: Two Centuries of the Balloon in America, Ritchel and Quinlan took the airship on tour with a traveling circus in the late 1870s. Ritchel also operated his machine at Brighton Beach near Coney Island. He sold a few replicas of his device and later attempted to develop a larger, long-distance version of the craft powered by an 11-person hand-cranking crew. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this idea failed to gain momentum, and Ritchel faded from the headlines. Soon, the exploits of new aeronauts would upstage him, among them Alberto Santos-Dumont’s circumnavigation of the Eiffel Tower in 1901.

Left: Alberto Santos-Dumont's first balloon, 1898. Right: Santos-Dumont circles the Eiffel Tower in an airship on July 13, 1901. Photographs: Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

Despite many earlier dirigible flights, Crouch and Grossman agree that the technology only became practical when German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin built and flew the first rigid dirigible in the early 1900s. Over the first decade of the new century, Zeppelin perfected his namesake design, which featured a fabric-covered metal frame that enclosed numerous gasbags. “By 1913, just before [World War I] begins, Zeppelin is actually running sightseeing tours over German cities,” Crouch says, “so the Zeppelin at that point can safely carry passengers and take off and land from the same point.”

For a brief period, airships ruled the sky. (The spire of New York City’s Empire State Building, built in the 1930s, was famously intended as a docking station for passenger airships.) But the vehicles, which use gas to create buoyancy, were quickly eclipsed by airplanes, which achieve flight through propulsion that generates airflow over the craft’s wings.

While the 1937 Hindenburg disaster is often viewed as the end of the dirigible era, Grossman says that’s a misconception: The real death knell for passenger airships arrived when Pan American Airways’ China Clipper, a new breed of amphibious aircraft, flew from San Francisco to Manila in November 1935. “Partly because they flew faster, they could transport more weight, whether it’s people or cargo, mail, whatever, in the same amount of time,” Grossman explains. “They were less expensive to operate, they required much, much smaller crews, [and] they were less expensive to build.”

Airplanes were also safer. “Zeppelins have to fly low and slow,” Crouch says. “They operate in the weather; airplanes don’t. An airplane at 30,000 feet is flying above the weather. Weather, time after time, is what brought dirigibles down.”

Today, niche applications for passenger airships endure, including the Zeppelin company’s European tours, as well as ultra-luxury air yachts and air cruises. But “it’s always going to be a tiny, tiny slice of the transportation pie,” Grossman says.

Crouch agrees. “People still talk about bringing back big, rigid airships. That hasn’t happened yet, and I don’t think it will,” he says.

The USS Los Angeles, a United States Navy airship, in 1931. Photograph Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

In some ways, Ritchel’s flying machine was a microcosm of the larger history of dirigibles: fascinating, fun and the perfect fodder for fiction, but ultimately eclipsed by more efficient technology.

As for Ritchel, he died, penniless, of pneumonia in 1911 at age 66. “Although during his lifetime he had perfected inventions that, in the hands of others, had brought in great wealth, he died a poor man, as he lacked the business ability to turn the children of his brain to the best advantage to himself,” wrote the Bridgeport Post in his obituary.

Even so, the public had not forgotten the brief time three decades earlier when Ritchel and his airship ruled the skies. As the Boston Evening Transcript reported, his flights captured “the attention of the world. In every country and in every language, newspapers and magazines of the day printed long stories of the wonderful feats performed by the Bridgeport aviator and his marvelous machine, of which nothing short of a cruise to the North Pole was expected.”

— Erik Ofgang is the co-author of The Good Vices: From Beer to Sex, The Surprising Truth About What’s Actually Good For You and the author of Buzzed: A Guide to New England's Best Craft Beverages and Gillette Castle: A History. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Atlantic, Thrillist and the Associated Press, and he is the senior writer at Tech & Learning magazine.

#Youtube#Air & Space Museum#Air Transportation#Airplanes ✈️ ✈️ ✈️#American 🇺🇸 History#Invention#Newspapers 📰 🗞️#Smithsonian Institution#Toys#Transportation#Wright Brothers#Flying Machine#Charles F. Ritchel#Airship#Professor Charles F. Ritchel#Inventer of the Only Flying Machine on Earth 🌎#Lardner & Co | 1319 Chestnut Street | Philadelphia | Pennsylvania

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna M. Mangin invented the pastry fork in 1891.The utensil was used to mix dough for pie crusts, cookies, butter and flour pastries without needing to mix the ingredients by hand. The fork was also used to beat eggs, mash potatoes, and prepare salad dressings. Mangin was awarded a patent on March 1, 1892, for the pastry fork for mixing pastry doughPATENT PASTRY-FORK.SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 470,005, dated March 1, 1892.Application filed July '7, 1891. Serial No. 398,705. (No model.)

With this invention, Mangin paved the way for future cooking gadgets to shorten cooking durations and alleviate the physical strain of kneading, mixing, and mashing by hand.

In 1893, Mangin's Pastry Fork displayed the ingenuity of African American inventors and the tenacity of African American women at the World's Columbian Exposition. Held in Chicago, Illinois, people of color and women were initially denied opportunities to participate in exhibits.

After repeated demands for inclusion a limited number of non-white exhibits including

Mangin's Pastry Fork were allowed. Although her invention occupied only a small corner on the second floor, a writer on female inventions noticed the kitchen wonder and called it "the only thing of its kind at the patent's office."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

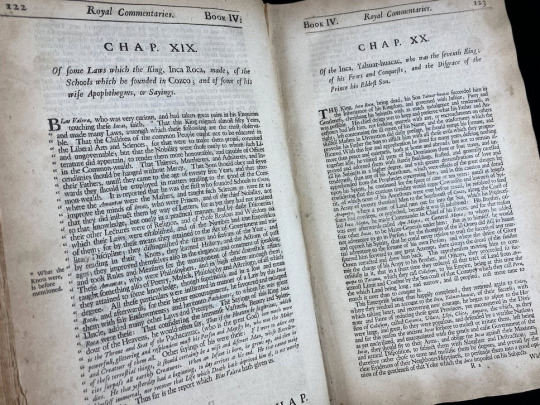

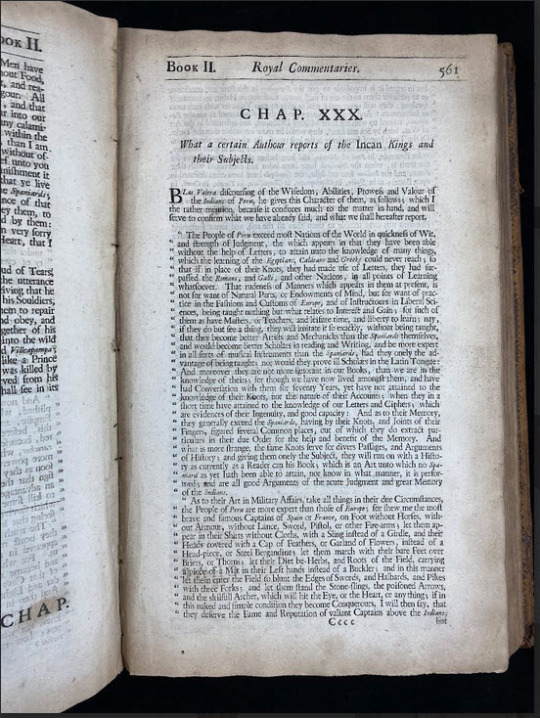

Publications of the New World

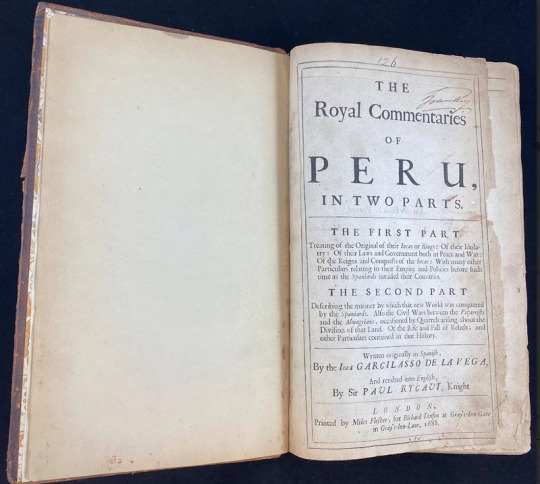

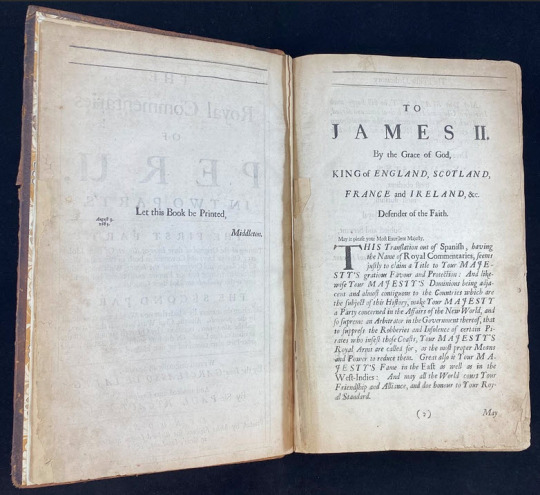

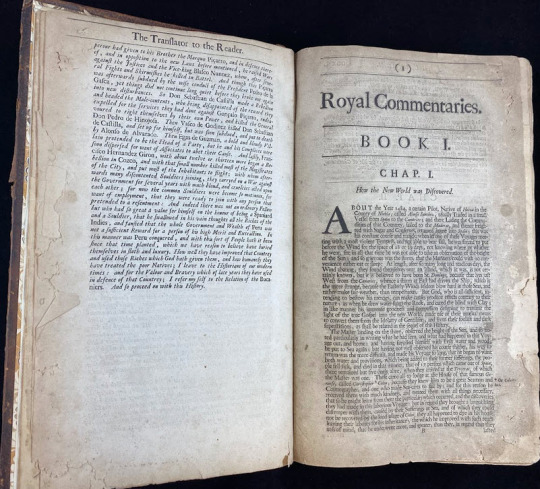

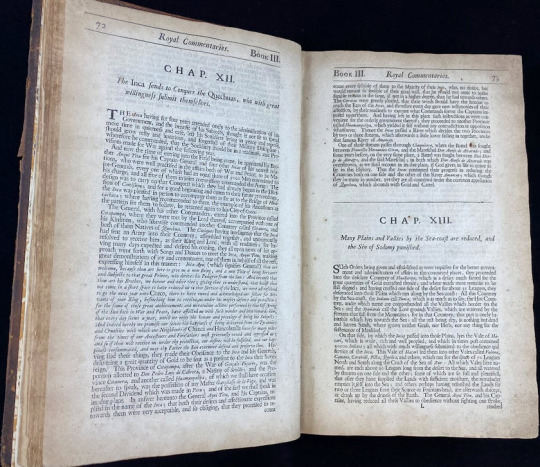

The James Smith Noel Collection has closed out another exciting exhibit, this time the topic was the New World of the Americas as experienced by Europe and other explorers. The exhibit: Exploration of the New World features the culture and intriguing history of Central and South America as it was experienced in the resources produced in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. We welcomed visitors to the mysterious, ancient rituals of the Pre-Columbian Mayans, the Aztecs of Mexico, and the Incas of Peru. We also showcased the advancements in architecture, science, and community development while marveling at the natural beauty of the regions.

One of the cases displayed a fascinating book which was originally published in Spanish and later translated into English. The edition house in the Noel Collection was published in 1688 of The royal commentaries of Peru, : in two parts. The first part Treating the Original of their Incas or Kings: Of their Idolatry … by Garcilaso de la Vega. Vega wrote a pivotal account of Incan history. Vega has a unique personal connection to the Incan world being a descendant of royal Incan lineage. He was half Spanish and Incan, his father being Spanish, and he chronicled Incan history, culture, and destruction as a result of the Spanish conquest. We featured a portion of text that discussed the minerals, precious metals, and natural resources found in Peru, such as, gold, silver, and mercury or quicksilver.

Vega was born as Gómez Suárez de Figueroa in April of 1539, and became known as El Inca. He ventured to Spain when he was 21 where he obtained an informal education and remained until his death in April of 1616. His father died in 1559 and Vega relocated to Spain two years later to seek acknowledgement as the natural son of the Spanish conquistador. His paternal uncle became his protector. While he primarily wrote on the Incan civilization, Spanish conquest, and an account of De Soto’s exploration of Florida.

Gómez Suárez de Figueroa was born in Cuzco, Peru; his father is recorded as being Sabastian Garcilaso de la Vega y Vargas, a Spanish captain, and his mother was Palla Chimpu Ocllo. When his mother was baptized after the fall of Cuzo and renamed Isabel Suarez Chimpu Ocllo, she was descended from Inca nobility, the daughter of Tupac Huallap and granddaughter of Tupac Yupanqui. Vega’s parents were not married in the Catholic church, resulting in his birth being considered illegitimate and he was given his mother’s surname. Vega was a child when his father left and married a younger Spanish noblewoman. His mother married and had two daughters. His first language was Quechua but learned Spanish as a child.

After moving to Spain, he received a European education and the works he produced was considered to have great literary value. He traveled to Montilla and met his father’s brother, Alonso de Vargas, who took him as his protector to help Vega make his way. He traveled to Madrid and petitioned the crown for acknowledgement. He was allowed the name of Garcilaso de la Vega, or "El Inca" or "Inca Garcilaso de la Vega" due to his mixed heritage. He had first-hand experience of the daily-life of the Inca life which heavily influenced his writings. His education allowed him to accurately describe the political system, labor force, and social life of the Incan empire.

Vega, Garcilaso de la (1688) The royal commentaries of Peru, : in two parts. The first part Treating the Original of their Incas or Kings: Of their Idolatry … London: Printed by Miles Flesher … https://bit.ly/3UxrtdH

Exhibit link: https://bit.ly/3y7k657

9 notes

·

View notes