#Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE )

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

【Reference Artifacts】

・China Han Dynasty Female Sitting & Dancer Figurines

・Plain yarn garment (straight) Mawangdui No. 1 Han Tomb (Xinzhui),China

material: silk,size: dress length 132 cm, sleeve length 181.5 cm

・ Floss silk padded robe,Mawangdui No. 1 Han Tomb (Xinzhui) ,China

length: 140 cm, overall length of the sleeves: 245 cm, width at waist: 52 cm

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE ) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Photoshoots【 西汉舞俑 】

________________

💃🏻Model:@尔七七七七

💄Stylist��� @仰望的花鼻子

📸Photo: @realyn

👗 Hanfu: @山涧服饰

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/5541803701/MwDiCs1G9

________________

#Chinese Hanfu#Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE )#chinese traditional clothing#Chinese historical fashion#hanfu history#chinese#Chinese Culture#Chinese Costume#chinese art#Chinese Aesthetics#China History#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu artifacts#漢服#汉服

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cocoon Flask, 206 BCE–9 CE / China, Western Han dynasty

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

#TwoForTuesday :

Pair of Owl-Shaped Jars

China, Henan province, Western Han dynasty, 206 BCE-9 CE

Amber brown-glazed low-fired pottery

19 x 13.8 x 11.8 cm (7 1/2 x 5 7/16 x 4 5/8 in.)

Cleveland Museum of Art

2020.178.1-2

“Pottery vessels in the shape of owls were made since Neolithic times and throughout the Bronze Age. These jars in the form of vigilant owls may have provided a tomb occupant with grain in the afterlife. However, the meaning of these mysterious birds and the association of the owl motif with burial sites in China is not fully understood.”

#animals in art#birds in art#birds#bird#owl#owls#pair#pottery#ceramics#funerary art#tomb art#Teo for Tuesday#ancient art#Chinese art#East Asian art#Asian art#museum visit#Cleveland Museum of Art#jar#animal effigy

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Silly Game Time: Halloween is a day for appreciating masks. As cultural artifacts, as objects of disguise, as pieces of art in their own right, as fun or frightening costumes, as sources of their own kinds of magic, and so on.

What are some masks (real or fictional, physical or psychological, mundane or magical, ugly or beautiful) you particularly appreciate?

this was part of a jade burial suit from the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE-9 CE), first half of second century BCE. I always found it beautiful, especially considering how old it is, and the care that went into its construct is just mindblowing

[link]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wine Jar, 206 BCE - 9 CE. Painted pottery 7 in. (17.78 cm) / Chinese, Western Han Dynasty .

Wine Jar, 206 BCE - 9 CE. Chinese, Western Han Dynasty .

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

*Xin Dynasty* Weiyang Palace Site

The majestic ruins of Weiyang Palace, once the political and cultural heart of the Western Han Dynasty. The ancient aura that permeates the air is nothing short of magical. Nestled on the northern outskirts of Xi'an, the Weiyang Palace Site boasts a history dating back more than two millennia. This archaeological treasure trove served as the imperial palace during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE). Commissioned by Emperor Wu, it stood as a symbol of political power and cultural innovation.

Dating back to the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE), the Weiyang Palace was a sprawling complex that once stood as the imperial residence of Liu Bang, the founding emperor of the Han Dynasty. The palace was a symbol of power, opulence, and the political prowess of the ruling dynasty. Over the centuries, the Weiyang Palace underwent numerous renovations and expansions, transforming into a grand architectural masterpiece. During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), the Weiyang Palace experienced yet another period of glory. Emperor Taizong, the second emperor of the Tang Dynasty, expanded the palace, adding more structures and enhancing its magnificence. It became a center of political, cultural, and social activities during this golden age of Chinese civilization.

Tragically, the Weiyang Palace fell victim to the ravages of time and war. Despite its historical significance, much of the palace was destroyed during the transition from the Tang to the Song Dynasty. The remnants of this once-imposing complex were buried beneath layers of earth and forgotten by the sands of time. Rediscovered during archaeological excavations in the 20th century, the Weiyang Palace Site has since become a window into the past. Visitors can explore the unearthed foundations and marvel at the remnants of ancient structures.

Today, the Weiyang Palace Site stands as a poignant reminder of China's rich history and the cyclical nature of empires. Its rediscovery and preservation serve as a testament to the importance of safeguarding our cultural heritage, allowing future generations to connect with the roots of their civilization and appreciate the enduring legacy of the Weiyang Palace.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

China, Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE)

Cocoon-Shaped Vessel. 2nd–early 1st century BCE. Credit line: Gift of Mrs. Richard E. Linburn, 1981 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/49901

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE) was the second dynasty of Imperial China (the era of centralized, dynastic government, 221 BCE - 1912 CE) which established the paradigm for all succeeding dynasties up through 1912 CE. It succeeded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) and was followed by the Period of the Three Kingdoms (220-280 CE).

It was founded by the commoner Liu Bang (l. c. 256-195 BCE; throne name: Gaozu r. 202-195 BCE) who worked toward repairing the damage caused by the repressive regime of the Qin through more benevolent laws and care for the people. The dynasty is divided into two periods:

Western Han (also Former Han): 202 BCE - 9 CE

Eastern Han (also Later Han): 25-220 CE

Read More Here

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon Sculptures Evidence of Ancient Cultural Exchange Between China and Mongolia

Two gilded silver dragon figurines featuring detailed horns, eyes, teeth, and feathers have been discovered in a Xiongnu elite tomb in north-central Mongolia. The dragons bear obvious characteristics of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE to 9 CE). They are evidence of the cultural exchange and interaction between the prairie in the north and central China, as well as the high status of the Xiongu buried in the tomb.

Of course, the silver dragons were not the only rich items they were buried with: a trove of gold, silver, bronze, jade and wood artifacts have also been found.

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering the world

China 🇨🇳

Basic facts

Official name: 中华人民共和国 (Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó) (People’s Republic of China)

Capital city: Beijing

Population: 1.4 billion (2023)

Demonym: Chinese

Type of government: unitary socialist republic

Head of state: Xi Jinping (CCP General Secretary and President)

Head of government: Li Qiang (Premier)

Gross domestic product (purchasing power parity): $35.29 trillion (2024)

Gini coefficient of wealth inequality: 37.1% (medium) (2020)

Human Development Index: 0.788 (high) (2022)

Currency: renminbi (CNY)

Fun fact: It is home to half of the world’s pig population.

Etymology

The country’s name comes from the Sanskrit Cīna, which could refer to the Qin dynasty, the state of Jing, or Zina, the endonym for the inhabitants of Yelang.

Geography

China is located in East Asia and borders Mongolia and Russia to the north, North Korea to the northeast, the Pacific Ocean to the east, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Bhutan, Nepal, and India to the south, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan to the west, and Kazakhstan to the northwest.

There are ten main climates: monsoon-influenced extremely cold subarctic in the northernmost part, monsoon-influenced warm-summer humid continental and monsoon-influenced hot-summer humid continental in the northeast, humid subtropical and monsoon-influenced humid subtropical in the southeast, dry-winter tropical savanna and tropical monsoon in the south, tundra in the southwest, and cold steppe and cold desert in the west and northwest. Temperatures range from −10 °C (14 °F) in winter to 40 °C (104 °F) in summer. The average annual temperature is 10.7 °C (51.2 °F).

The country is divided into twenty-two provinces (shěng), five autonomous regions (zìzhìqū), four direct-administered municipalities (zhíxiáshì), and two special administrative regions (tèbié xíngzhèngqū). The largest cities in China are Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Tianjin.

History

10600-7500 BCE: Nanzhuangtou culture

7000-6500 BCE: Xiaohei culture

7000-6100 BCE: Pengtoushan culture

7000-5000 BCE: Peiligang culture

6500-5000 BCE: Cishan culture

6200-5400 BCE: Xinglongwa culture

6000-5000 BCE: Beixin culture; Dadiwan culture

5500-4800 BCE: Xinle culture

5500-3300 BCE: Hemudu culture

5400-4500 BCE: Zhaobaogou culture

5200-5000 BCE: Fuhe culture

5000-3300 BCE: Majiabang culture

5000-3000 BCE: Daxi culture; Yangshao culture

4700-2900 BCE: Hongshan culture

4300-2400 BCE: Dawenkou culture

3800-3300 BCE: Songze culture

3500-2000 BCE: Xiaoheyan culture

3400-2600 BCE: Qujialing culture

3300-2300 BCE: Liangzhu culture

3000-1900 BCE: Longshan culture

2500-2000 BCE: Shijiahe culture

2200-1600 BCE: Lower Xiajiadian culture

2070-1600 BCE: Xia dynasty

2000-1600 BCE: Erlitou culture

1600-1400 BCE: Erligang culture

1600-1046 BCE: Shang dynasty

1046-256 BCE: Zhou dynasty

1000-600 BCE: Upper Xiajiadian culture

221-206 BCE: Qin dynasty

202 BCE-9 CE, 25-220: Han dynasty

9-23: Xin dynasty

220-266: Cao Wei

221-263: Shu Han

222-280: Eastern Wu

266-420: Jin dynasty

304-439: Sixteen Kingdoms

386-535: Northern Wei

420-479: Liu Song

479-502: Southern Qi

502-557: Liang

534-550: Eastern Wei

535-557: Western Wei

550-577: Northern Qi

555-587: Western Liang

557-581: Northern Zhou

557-589: Chen

581-618: Sui dynasty

618-690, 705-907: Tang dynasty

690-705: Wu Zhou

907-979: Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms

916-1125: Liao dynasty

960-1279: Song dynasty

1271-1368: Yuan dynasty

1368-1644: Ming dynasty

1644-1912: Qing dynasty

1839-1842: First Opium War

1850-1864: Taiping Rebellion

1851-1868: Nian Rebellion

1855-1868: Punti-Hakka Clan Wars

1856-1860: Second Opium War

1856-1873: Panthay Rebellion

1862-1877: Dungan Revolt

1894-1895: First Sino-Japanese War

1899-1901: Boxer Rebellion

1911: Wuchang Uprising; Xinhai Revolution

1912-1949: Republic of China

1919: May Fourth Movement

1927-1936, 1945-1949: Chinese Civil War

1931-1937: Chinese Soviet Republic

1937-1945: Second Sino-Japanese War

1949-present: People’s Republic of China

1950: annexation of Tibet

1989: Tiananmen Square protests

1997: return of Hong Kong

1999: return of Macau

Economy

China mainly imports from the European Union, Taiwan, and South Korea and exports to the United States, the European Union, and Japan. Its top exports are data-processing machines, radio transmission tools, and electronic integrated circuits.

It has transitioned from an economy focused on manufacturing consumer products to one centered on high-tech industries. Services represent 54.6% of the GDP, followed by industry (38.3%) and agriculture (7.1%).

China is a member of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the BRICS, the G20, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Demographics

The Han constitute 91.5% of the population, followed by the Zhuang (1.2%), Manchu (0.8%), Uyghur (0.7%), Hui (0.7%), and Miao (0.7%). The main religion is Buddhism, practiced by 33.4% of the population.

It has a negative net migration rate and a fertility rate of 1 child per woman. 64.6% of the population lives in urban areas. Life expectancy is 76.3 years and the median age is 38.4 years. The literacy rate is 99.8%.

Languages

The official language of the country is Mandarin, spoken by 64% of the population as their first language. Other languages are official in their respective provinces or prefectures: Cantonese, English, Kazakh, Korean, Mongolian, Portuguese, Tibetan, Uyghur, Yi, and Zhuang.

Culture

Chinese culture has been heavily influenced by Confucianism. Elders are highly esteemed, and there is a great pressure to have children.

Men traditionally wear an open cross-collar shirt (yī), a long, wrap-around skirt (cháng) or pants (kù), and cloth shoes (lü). Women wear an open cross-collar shirt (rù) and a long, wrap-around skirt (qún) or a tight-fitting dress with two side slits (qípáo) and cloth shoes (lü).

Architecture

Traditional houses in China are symmetric and made of wood and stone, have an open courtyard and upturned eaves.

Cuisine

The Chinese diet is based on meat, noodles, rice, and vegetables. Typical dishes include chow mein (a dish of stir-fried noodles with vegetables and meat or tofu), mapo tofu (tofu in a hot and spicy sauce), Peking duck (roasted duck served with cucumber, spring onions, and sweet bean sauce), tangyuan (glutinous rice balls filled with black sesame paste and served in a hot broth or syrup), and wonton soup (a chicken broth with dumplings stuffed with meat and prawns).

Holidays and festivals

China celebrates New Year’s Day, Spring Festival in late January or early February, Tomb-Sweeping Day on April 5, Labor Day, Dragon Boat Festival on the fifth day of the fifth month of the traditional Chinese calendar, Mid-Autumn Festival on the 15th day of the eighth month, and National Day on October 1.

Mid-Autumn Festival

Other celebrations include the Double Ninth Festival, when it is customary to climb a mountain, drink chrysanthemum liquor, and wear the zhuyu plant; the Hungry Ghost Festival, when the family’s ancestral tablets are placed on a table and incense is burned to avoid the wrath of the ghosts, and the Snow and Ice Festival, which features ice sculptures.

Snow and Ice Festival

Landmarks

There are 57 UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Ancient Building Complex in the Wudang Mountains, Ancient City of Pingyao, Ancient Villages in Southern Anhui – Xidi and Hongcun, Archeological Ruins of Liangzhu City, Capital Cities and Tombs of the Ancient Koguryo Kingdom, Chengde Mountain Resort and its Outlying Temples in Chengde, Chengjiang Fossil Site, China Danxia, Classical Gardens of Suzhou, Cultural Landscape of Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, Cultural Landscape of Old Tea Forests of the Jingmai Mountain in Pu’er, Dazu Rock Carvings, Fujian Tulou, Grand Canal, Great Wall, Historic Center of Macau, Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace, Historic Monuments of Dengfeng in “The Center of Heaven and Earth”, Huanglong Scenic and Historic Interest Area, Hubei Shennongjia, Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic and Historic Interest Area, Kaiping Diaolou and Villages, Kulangsu: a Historic International Settlement, Longmen Grottoes, Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor, Migratory Bird Sanctuaries along the Coast of Yellow Sea-Bohai Gulf, Mogao Caves, Mount Emei Scenic Area, Mount Fanjing, Mount Huangshan, Mount Qingcheng and the Dujiang Irrigation System, Mount Sanqing, Mount Tai, Mount Wutai, Mount Wuyi, Mountain Lu National Park, Old Town of Lijiang, Peking Man Site at Zoukoudian, Qinghai Hoh Xil, Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries, Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor, Site of Xanadu, South China Karts, Summer Palace, Temple and Cemetery of Confucius and the Kong Family Mansion in Qufu, Temple of Heaven, Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, Tusi Sites, West Lake Cultural Landscape of Hangzhou, Wulingyuan Scenic and Historic Interest Area, Xinjiang Tianshan, Yinxu, Yungang Grottoes, and Zuojiang Huashan Rock Art Cultural Landscape.

Zhangjiajie National Forest Park

Other landmarks include the Huangguoshu Waterfall, the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, the Reed Flute Cave, the Saint Sophia Cathedral, and the Three Gorges Dam.

Saint Sophia Cathedral

Famous people

Gong Li - actress

Jackie Chan - actor

Lang Lang - pianist

Li Po - poet

Liu Yifei - actress and singer

Mo Yan - writer

Peng Shuai - tennis player

Yan Geling - writer

Yang Liping - dancer

Yao Ming - basketball player

Lang Lang

You can find out more about life in China in this article and this video.

#discoveringtheworld#langblr#cantonese#english#kazakh#korean#mandarin#mongolian#portuguese#tibetan#uyghur#yi#zhuang

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jade Disk - China, Western Han dynasty (206 BCE - 9 CE)

Freer / Sackler Galleries - The Dr. Paul Singer Collection

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

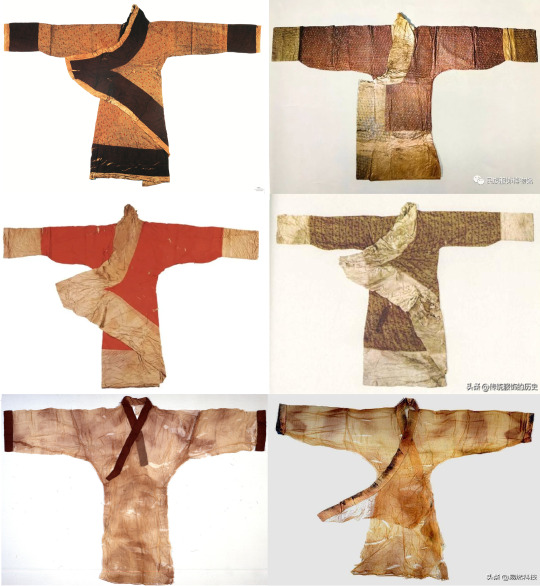

【Historical Artifacts Reference】

China Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE)Female Figurines

Robes (”Quju/曲裾” & Zhiju/直裾”) of silk, cotton and Plain yarn garment(素纱襌衣)from the Mawangdui Tombs belonging to Xin Zhui(辛追), Marquess of Dai - c. 217 BC-168 BC, Western Han Dynasty, China

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE ) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Western Han Dynasty Relics

————————

📸Recreation Work: @吃货娃娃

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1868003212/MEFf77xsW

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Western Han Dynasty(206 BCE–9 CE )#chinese traditional clothing#chinese historical fashion#hanfu history#chinese#chinese culture#Chinese Costume#chinese art#Chinese Aesthetics#China History#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu artifacts#historical hairstyles#漢服#汉服#Mawangdui Tombs#Xin Zhui(辛追)#Quju/曲裾#Zhiju/直裾#Plain yarn garment(素纱襌衣)#吃货娃娃

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Underwater City: Unveiling The Secrets At The Bottom Of Fuxian Lake

A mystery lies scattered on the unexplored bottom of Fuxian Lake, stretching out through Chengjiang County, Jiangchuan County and Huaning County in Yunnan Province, about 60 kilometers to Kunming City, China. The lake is rising 1,720 meters above sea level and encompassing 212 square kilometers of land.

The deepest part of the lake descends 157 meters; the Fuxian Lake is the second deepest freshwater lake in China.

One day, Geng Wei, a specialized diver, accidentally found a strange phenomenon under the lake, in form of stone materials including flagstones and stone strips with thick moss above them, could be seen.

According to an ancient local legend, a city-like silhouette under the lake from the nearby mountains can be clearly seen on a fine, calm day. To find out if there is something hidden in the calm waters of the lake, a Chinese submarine archaeology team stationed in Fuxian Lake carried on surveys and with advanced use of detectors, discovered lots of blocks scattered on the lake bottom, stones that formed a wall seen on a sonar display along with various flagstones.

High stairs appeared in front of them and flagstones covered with moss seemed to reveal an ancient sunken city. The team members found the scope of the site under Fuxian Lake was extremely big, and the traces of construction were everywhere along with earthenware.

Could the underwater site be the ancient city of Yuyuan, which disappeared mysteriously many hundreds of years ago?

Was the site under the lake the city recorded in The Book of Han (Hanshu), a classic Chinese historical writing covering the history of the Western Han Dynasty, 206 BCE-9 CE, that once recorded that Yuyuan City was north of Fuxian Lake?

After several days of observation, sonar scans and analyses, experts estimated the scope of the area is between 2.4 square kilometers to 2.7 square kilometers, and the site was possibly from the Warring States (475-221 BC) to the Eastern Han Dynasty. However, in order to find a more exact time, they had to find a subject that could be used for carbon 14 testing.

Additionally as reported, eight main buildings were found all under the water, including a round, colosseum-like building with a 37 meter wide base and a gap to the northeast and two large high buildings with floors, similar to the Mayan pyramids. One of the large, high buildings has three floors, a 60 meter wide base and lots of small steps linking the floors. Another is even larger, with a 63 meter wide base standing five floors (totally 21 meters high). A 300 meter long and 5 to 7 meter wide rock road connects the two buildings.

Carbon-14 dating of some shells attached to blocks they were 1750 years old, which means the site sunk during the Han period. However in the Tang Dynasty, there were still records about Yuyuan City remaining on land.

Therefore, the lost city was not Yuyuan, but rather the ancient unidentified structure of the under-lake construction, could represent the remains of the ancient Dian Country – a country with a high level of civilization that after 86 BC – mysteriously disappeared.

Fuxian Lake is a very large body of water – is still unexplored, so various legends have prevailed for more than 1,000 years and unfortunately their credibility cannot be confirmed.

According to one story mentioned in “Cheng Jang Fu Zhi”, a book in the region of Emperor Daoguang, a horse-like animal lived in the lake. Its body was pure white with red spots on its back. Sometimes it rapidly flew out of the water. Was this strange animal perhaps a vehicle which modern ufologists today call – uso (unidentified submerged object)?

....

We are a race with amnesia. There is so much out there forgotten, unfortunately. There were amazing civilizations here from every single cultural groupings. Humanity has a history untold as of yet.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: From a Jade Burial Suit to Terracotta Warriors, a Blockbuster Display of China’s Ancient Treasures

Jade (nephrite) burial suit of Dou Wan from the Western Han dynasty (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

When the Han Dynasty princess Dou Wan died some 2,000 years ago, her corpse was encased within 2,160 small plates of solid jade. Carefully strung together with 700 grams’ worth of gold thread, the green stones formed a glistening cocoon that conformed to the contours of her body, intended to preserve it for eternity. That jade burial suit, recovered with her husband’s in 1968 from their tombs in the northern Chinese province of Hebei, is currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s one unmissable, standout artifact in a blockbuster exhibition showcasing the rich artworks that emerged during two of China’s most pivotal dynasties.

Fluted column with dragons and Chinese inscriptions (2nd century CE)

Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties is impressive in logistics alone. The over 160 objects arrive on loan from 32 museums and archaeological institutions in China — just think of the bureaucratic hurdles, never mind the shipping — and most have never before been displayed in the West. The exhibition is intended as a kind of visual summary of archaeological findings, mostly from shrines and underground tombs of royals, from the last half-century. The result showcases the remnants of 400 years of innovation and craftsmanship, developed to suit the visions of an increasingly unified state.

The long histories of the Qin and the Han dynasties, which witnessed the centralization of government and the standardization of everything from laws to the economy to written language, are glossed over in a handful of wall texts. The exhibition relies largely on visual splendor, with the objects, most of which are accompanied by short descriptions, serving as traces of a clearly astounding past. That this didn’t bother me is a testament to the allure and evocative power of almost every piece on view, from tiny jade pigs intended to serve as hand warmers for the dead to a life-size, terracotta statue depicting a rotund strongman — a performer in an acrobatic troupe who likely entertained the imperial court of China’s first emperor, Qin Shihuangdi. (Detailed historical context, for those who seek it, can be found elsewhere, in the show’s dense catalogue.)

As the museum’s curator of Chinese art, Zhixin Jason Sun, writes in a catalogue essay, “These remarkable objects attest to the unprecedented role of art as spectacle, and more importantly, reflect changes in political, social, economic, and religious aspects of public life.”

Strongman from Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE)

Installation view of Age of Empires at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Organized chronologically, Age of Empires begins with what are probably the most recognized jewels of ancient Chinese art outside of that country: five examples of the terracotta warriors from Qin Shihuangdi’s mausoleum complex, along with eight nearly life-size earthenware horses pulling two chariots (modern replicas of Qin originals). It’s a crowd-pleasing introduction, but also one that exemplifies the naturalism that characterized Qin works: the curved forms of the frozen archers, originally painted, are particularly elegant, and you’ll notice that each warrior bears an individual visage. It’s easy to forget that the results of this painstaking labor were never intended for our world of the living, produced to reside underground for eternity and endure as markers of an emperor’s eternal power.

The majority of what follows dates to the Han Dynasty, which the peasant rebel leader Liu Bang founded in 206 BCE. Although most objects were created for funerary use, they aren’t generally somber in appearance, a reminder that the Han viewed the afterlife as a realm where pleasure should flourish. A tomb of a prince of the Chu state, for instance, yielded a group of small, earthenware models of dancers and musicians. Although their faces are blank, their active poses convey a palpable energy, as if a snap of the fingers could magically awaken them to continue performing. One statue of a curved female dancer is particularly mesmerizing, with her wide sleeves billowing to form tall parabolas. She looks like she’s doing the wave with her entire body.

“Female Dancer” figure from the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE)

“Female Musician Playing a Flute or Panpipe” figure from the Western Han Dynasty

Mausoleums were built as extensive replicas of real-world residences, so most of the objects in Age of Empires are more quotidian in nature. Their occupants spared no expense, however, ordering artisans to create lacquered tableware, skillfully woven silk textiles, furnishings that boast intricate metalwork. Smaller versions of buildings stood in funerary complexes, too, as models of grand homes that conveyed an owner’s status and power. One luxury, multistory structure is so realistic, it even has a tiny guard dog sitting by its entrance. Animals themselves were popular subjects for standalone works. Some species were considered auspicious symbols, while others represent the exotic creatures that populated imperial zoos. An entire gallery at the Met is filled with animals, from elephants to cows, sculpted in a variety of materials.

While the Han developed and honed the imperial policies established by the Qin at home, it was busy engaging beyond China’s borders as well. Some of the most intriguing artifacts on view speak to the growing trade networks that resulted from the Han’s military and diplomatic campaigns. Beautiful objects integrate precious materials from places such as Persia, India, and Sumatra, while other artifacts reveal foreign influences more explicitly: for instance, the unique mix of culture in a Hellenistic fluted stone column that bears a Chinese inscription. Then there’s a comical lamp with a fuel chamber shaped like a Southeast Asian man, who hovers in the air, attached to chains — a design borrowed from the ancient Mediterranean.

“Hanging Lamp in the Shape of a Foreigner” from the Eastern Han dynasty

Although many of these objects were made for individuals, their specific identities and stories aren’t highlighted here. Most of the works are placed in glass cases or set on protective pedestals, presented as priceless artifacts displaced from their original, funerary contexts. Its unique construction aside, the jade suit of Dou Wan stuns because it represents a real body. To turn a corner and suddenly behold the otherworldly armor lying still in its own room is jarring. But it’s also stirring, with that mass of protective stone reminding us of the very human uncertainties and fears behind every material affirmation of power.

Lamp in the Shape of a Mythical Bird from the Western Han dynasty

“Brick with Ax-Chariot” from the Eastern Han dynasty

Terracota armed warriors from the Western Han dynasty

Tomb Gate from the Eastern Han dynasty

Dog from the Eastern Han dynasty

Lidded box and jade bear from the Western Han Dynasty

Elephant and Groom from the Western Han dynasty (2nd century BCE)

Detail of jade (nephrite) burial suit of Dou Wan from the Western Han dynasty

Hardstone jade pigs that served as “hand warmers” from the Western Han dynasty

Model of a multistory house from the Eastern Han dynasty

Cowry Container with Scene of Sacrifice from the Western Han dynasty

Bronze horse and groom from the Eastern Han Dynasty

“Standing Archer” figure from the Qin dynasty

Groups of chariot drivers, chariot riders, and infantrymen from the Western Han dynasty

Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C.��A.D. 220) continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through July 16.

The post From a Jade Burial Suit to Terracotta Warriors, a Blockbuster Display of China’s Ancient Treasures appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2rRMhAE via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

Until 1530, sculptural images of Confucius and varying numbers of disciples and later followers received semiannual sacrifices in state-supported temples all over China. The icons' visual features were greatly influenced by the posthumous titles and ranks that emperors conferred on Confucius and his followers, the same as for deities in the Daoist and Buddhist pantheons. This convergence led to visual conflation and aroused objections from Neo-Confucian ritualists, culminating in the ritual reform of 1530, which replaced images with inscribed tablets and Confucius s kingly title with the designation Ultimate Sage and First Teacher. However, the ban on icons did not apply to the primordial temple of Confucius in Qufu, Shandong. Post-1530 gazetteers publicized the distinction by reproducing a line drawing of this temples sculptural icon, and persistent replications of this image helped to popularize his cult. The same period saw a proliferation of non-godlike representations of Confucius, including his portrayal as a teacher, whose iconographic origins can be traced to a painted portrait handed down through generations of his descendants. In recent years, variations of this teacher image have become the basis for new sculptural representations, first in Taiwan, then in Hong Kong and the Chinese diaspora, and finally on the mainland. Now installed at sites around the world, statues of Confucius have become a contested symbol of Chinese civilization.

Julia K. Murray, "Idols" in the Temple: Icons and the Cult of Confucius, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 68, No. 2 (May, 2009), pp. 371-411.

Various efforts in recent centuries to foreground the moral dimension of Confucius’s legacy have obscured practices and beliefs involving icons, along with other religious aspects of Confucianism. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Jesuit missionaries tried to convince papal authorities in Rome that Confucianism was an ethical philosophy (Jensen 1997, 63-70, 129), so that efforts to spread Christianity in China would not be stymied by requiring converts to give up rituals for worshiping Confucius Similarly, in the nineteenth century, the Protestant missionary-translator James Legge argued that the ancient Confucian classics merely needed to be supplemented with Christianity, just as the Bibles Old Testament was completed by the New Testament (Mungello 2003, 590). Moreover, from the sixteenth century onward, Confucian temples were austere buildings where inscribed tablets were displayed, unlike Buddhist temples and popular-cult shrines with sculptural icons in sensuous pro fusion.2 Although Kang Youwei (1858-1927) sought to establish Confucianism as Chinas official religion (zongjiao) at the end of the nineteenth century, on the model of Christianity in Western nations, he made little headway before falling from power in the coup that reversed his 1898 reforms (Chen 1999; Goossaert 2005, 2006). Because regular worship of Confucius was on the official Register of Sacrifices (Sidian), and thus was closely identified with the imperial system, the collapse of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) undercut subsequent efforts to create a religion based on Confucianism. In the early decades of the twentieth century, some nationalist modernizers wanted to discard Confucius altogether, while others found it expedient to present him as Chinas counterpart to the Wests great rational philosophers. Suppressing what they considered to be idolatry and superstition, they emphasized a Confucius who did not concern himself with "ghosts and spirits." And in recent years, global advocates of "New Confucianism" have focused on his ideas about self-cultivation and morality.3 To some, Confucian concepts of reciprocal responsibility in a hierarchical society suggest an Asian alternative to Western-style democracy. These different efforts have created a widespread conception of Confucianism that is defined by a set of ancient texts, the civil service examination system based on their mastery, and the promotion of social virtues such as benevolence (ren), filial piety (xiao), propriety (li), and righteousness (yi).

[...]

Other conceptions of Confucius emphasized his roles as a teacher and as an expert on ancient ritual, instead of as a preternaturally insightful and prescient leader who communed with heaven. In some parts of the Analects (Lun yu), Confucius is portrayed as a human being who endured much travail and disappointment, especially while traveling the ancient states in search of a ruler who would take his advice (Csikszentmihalyi 2002).7 By the late Eastern Han period, this more mundane Confucius had largely overshadowed the superhuman figure. Nonetheless, the messianic sage was featured in the so-called apocryphal texts (weishu It H) of the late Han and post-Han periods (e.g., Wang Jia 1966,3:4?5). In addition, the "modern text" traditions retained their vitality in South China well into the Period of Disunion (Wilson 1995, 32). Furthermore, the Kong lineage perpetuated and embellished the legends in oral traditions and written genealogies, even down to the present day.8 Claiming descent from Confucius, lineage members had a vital interest in preserving a heroic conception of their ancestor and in maintaining their own cohesion (Wilson 1996). Emperors from the Han through the Qing dynasties awarded noble titles, tax exemptions, official positions, and lands to the descendants who maintained sacrifices to Confucius in Qufu.

Although the earliest forms of veneration and sacrifice to Confucius occurred in funerary and memorial contexts, the observances themselves increasingly displayed the features of a deity cult. Confucius continued to receive sacrifices at his grave long past the normal period for commemorative worship (Jensen 2002, 180-86; Sima 1982, 47:1945). Moreover, persons with no blood relation to him made these offerings, contrary to the customs of familial worship, which prescribed that a son should lead funerary rites?but Confucius s son had predeceased him. After Confucius died in 479 BCE, his disciples carried out the rites of mourning, and the especially devoted Zi Gong M kept a six-year vigil in a hut beside the burial mound (Sima 1982, 47:1945). Local authorities maintained offerings at this site for generations afterward. The place where Confucius had gathered with his disciples became a memorial hall, and his personal effects were displayed there. The Grand Historian Sima Qian (145-86 BCE) reported seeing the masters clothes, cap, zither (qin), books, sacrificial vessels, and carriage in the memorial hall when he visited Qufu. In 195 BCE, the Han founding emperor Gaozu (r. 206-195 BCE) performed a grand sacrifice (tailao X ?) to Confucius in Qufu, offering an ox, sheep, and pig, along with wine and other foodstuffs (Sima 1982, 47:1945-46). In 136 BCE, Han Wudi (r. 141-87 BCE) canonized the textual tradition of Confucius and his followers by abolishing the posts of Erudite (boshi) held by court scholars who were experts in texts belonging to other traditions (Wilson 1995, 29). Other Han emperors awarded posthumous titles of nobility to Confucius and gave material support to his descendants and cult, providing for semiannual sacrifices in Qufu after 169 CE (Wilson 2002c, 261).

By the third century, sacrifices to Confucius were also being performed elsewhere, typically in academic settings. The first sacrifice documented outside Qufu took place in 241 CE at the imperial university (Biyong) in Luoyang, the capital of the kingdom of Wei (220-65), and several more were per formed there under the Western Jin dynasty (265-316) (Wilson 2002b, 74).9 During the centuries of disunion, various northern and southern regimes established state-sponsored temples in their capitals for conducting sacrifices to Confucius and his legacy.10 The Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties continued this practice in a reunified empire. The Tang founding emperor Gaozu (r. 618-26) established a temple at the National University (Guozi xue) in Chang'an (modern Xi'an, Shaanxi) and personally sacrificed there in 624 (Ouyang 1975, 1:9, 17). The Tang eastern capital at Luoyang also had an imperially sponsored temple. Initially, it was the Duke of Zhou JH the wise regent to the young heir of the Zhou dynasty founder, who was honored as First Sage (Xian sheng), and Confucius received sacrifice as Correlate (Fei) and First Teacher (Xian shi). In 628, a memorial submitted by Fang Xuanling (579-648) convinced the Tang emperor Taizong (r. 626-49) that sacrifices offered in a school should be directed to a teacher. Accordingly, Taizong ended sacrifices to the Duke of Zhou and designated Con fucius as First Sage, with the disciple Yan Hui II d? as Correlate and First Teacher (Ouyang 1975, 15:373, 375).11 Taizong extended the cult to lower levels of administration in 630 by requiring every prefectural and county school to build a temple to Confucius, thus creating a systematic network of state-sponsored temples (Ouyang 1975, 15:373). Located inside or adjacent to the government schools, these temples carried out regular sacrifices to Confucius twice a year, in spring and autumn.

Tang ritual codes ranked the sacrifice to Confucius as one of several mid-level rites (zhong), prescribing specific implements, offerings, music, and participants.12 The liturgy imitated that of another mid-level state cult, the worship of the Gods of Soils and Grains (Sheji), which had existed in classical antiquity and whose rituals were prescribed in the Record of Rites (Liji). Because the ceremony for sacrifice to Confucius had no fixed classical form of its own, it was susceptible to innovations, and procedural details often changed. Most significantly, portrait icons were introduced into the ceremony, probably inspired by the images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas in Buddhist temples. Starting in the Tang period, the Chan Buddhist practice of using portrait effigies in memorial rituals for deceased abbots and monks (Foulk and Sharf 1993-94) provided an additional model that encouraged the use of icons in Confucian temples.

0 notes

Text

Tomb treasures : new discoveries from China's Han dynasty

"This exhibition catalogue features archaeological discoveries found in kings' and other royalty's mausoleums and tombs from the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE-9 CE) in Jiangsu province, China. These royals lived extravagantly and, after death, were buried in grand style to ensure a prosperous afterlife. Royal mausoleums were furnished with enormous quantities of treasures comprising not only luxurious goods used in real life, but also artifacts made specifically for burial. About 100 objects (made of gold, silver, jade, bronze, pottery, lacquer, and other refined materials) will be featured, and most of these will be exhibited for the first time outside of China. Masterworks include a full-length jade suit sewn with gold threads, a huge coffin shrouded in jade, and a complete set of functional bronze bell chimes for court music"-- Provided by publisher.

0 notes