#Vodou quote

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Words To Live By

#conjuring#spiritual#like and/or reblog!#rootwork#voodoo#louisiana voodoo#Vodou quote#Quote of the day#Spiritual quote#follow my blog#southern magic#Magic quote

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lol, I was thinking of a pairing for a voodoo or vodou!reader, and all of a sudden Bartholomew Henry Allen II popped into my mind, and I can't get over it. It's like Bart falling in love with the reader because under all that weird, creepy, and mysterious aloof personality, there's a dork ready to emerge. He sees how your face lights up when he mentions one of your interests; he knows how socially awkward you are, but you still make an effort to hold a conversation. When I think about their relationship, it reminds me of Asa and Denji from Chainsaw Man. They're that weird couple that just works so well together. They'll go on a date to the aquarium while being high as hell, holding hands and watching the jellyfish glow and swim by. Bart will gladly be your sacrifice for whatever magical nonsense you're up to. He's your dream blunt rotation. I also feel like their relationship will give off Jessica Rabbit and Roger Rabbit vibes, with the voodoo reader being all fashionable and put together, and there's your boyfriend who can't tie his own tie. You can't help but laugh. "Their so mysterious!" "He's so fucking dumb; I just want to kiss him!" Everyone is like, "What do you see in him?" and you'll sigh with dreamy eyes at the world.

Bart: Flowers for you, babe!

*Bart holding out a thing of lettuce for you*

Vodou!reader: Oh, it's lovely!~

*The Batfam is now confused about why you have a bouquet of lettuce in a floral vase in your room.*

#x black reader#black!reader#weird!reader#x neglected reader#batfamily x neglected reader#yandere batboys#yandere batfam#yandere batfamily#black fem reader#black male reader#black nonbinary#magical!reader#vodou!reader#haitian vodou#voodoo!reader#vodou#voodoo#bart allen x reader#bart allen#impulse 1995#dc impulse#dc headcanon#reader headcanons#inncorrect quotes#dc incorrect quotes

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The god who created the sun which gives us light, who rouses the waves and rules the storm, though hidden in the clouds, he watches us. He sees all that the white man does. The god of the white man inspires him with crime, but our god calls upon us to do good works. Our god who is good to us orders us to revenge our wrongs. He will direct our arms and aid us. Throw away the symbol of the god of the whites who has so often caused us to weep, and listen to the voice of liberty, which speaks in the hearts of us all."

- Oungan (Vodou priest) Dutty Boukman, his Bois Caiman speech. These are the words that incited the Haitian Revolution on the night of 22 August 1791.

#history#haitian vodou#oungan#haiti#haitian revolution#revolution#anti colonialism#quote#black jacobins#vodou#pagan#caribbean#war#afro caribbean#bois caiman#haitian creole

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#photography#cotonou#romao#jeuneesthete#africa#quotes#benin#life#beninrepublic#iamromao#vodoun#vodou#culture#history#art history#tradition#traditional art#performance#spirituality#religious art#beautiful#photographer#memories

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

⋆。‧˚ʚ🍓MASTERLIST🍓ɞ˚‧。⋆

@l0s3rd0wnt0wn

[Platonic Yandere!Batfam x Weird black neglected!reader]

[Weird black neglected!reader head canons!!]

[platonic yandere batfam x Weird black!Reader]

[Yandere Conner Kent x Weird black!reader]

[Weird black neglected!reader]

[Weird black neglected!reader is the type of mf]

[Weird black neglected!reader and the things the hate about the batboys do that disgust reader]

[Yum, good soup!]

[Reader going with Catwoman to steal shit because she can't afford the Gojo and Suguru Nendoroid]

[the black reader likes physical contact...except with the batfam (alfred doesn't count)]

[adult black!a reader]

[WEIRD BLACK!READERS MUSIC]

[reader is a total fan of another hero]

[Black Weirdo MC becomes the DC equivalent of either a twitch streamer or Youtuber]

[IT'S NOT JUST HAIR!]

[reader loves and trusts completely can touch his hair]

[reader doesn't really care when the Batfam gets hurt]

[MY BIG SISTER GLOWS!!!]

[connor/black!reader. how would the batfam react]

[Weird neglected black!reader loves dating sims of all kinds]

["ONE STEP TWO STEP THREE STEP OW!"]

["WHEN FINE SHYT IS LOW-KEY A WERIDO"]

[batfam react if every time they pushed the limits of black bizarre reader they reacted in very stupid ways]

[Wb!Reader on their 14th hour of forcing Connor to listen to BTS]

[reader's mother's relationship with bruce and does the rest of the batfam know about her?]

[black!raeader listening and singing to peggy by ceechynaa]

["BABY YOU SMELL LIKE HAIR SPRAY!!~"]

["WHY SEE THE WORLD WHEN GOT THE BEACH"]

[One step, two step, three step, ow! Part 2]

[that one scene in Turning Red.]

[reader getting a pericing like multiple ear piercings or a nose pericing without the batfam knowing]

["BABY HE'S A BITTER"]

[reader took a baking for a brief moment because a dessert they saw in an anime looks too good]

["YOUR TO SLOW!!"]

[black reader will totally tchip the batfamily at every opportunity]

[Yummy, good soup! 🍲]

[batfam being complete Yandere for our mother but not searing an ounce of attention to use unless told to by our mother]

[Imma steal thar quote thank you very much!]

[Black Weirdo MC with Vtuber]

[Reader wearing batfamily merchandise]

["HE'S BLEEDING ON MY LIPS"]

[Black reader and corners relationship]

[which lyon kid is reader most like]

[look like our mom wix with Martha Wayne]

[weird reader was emo or coquette]

[reaction of the batfamily if the reader took his mother's last name]

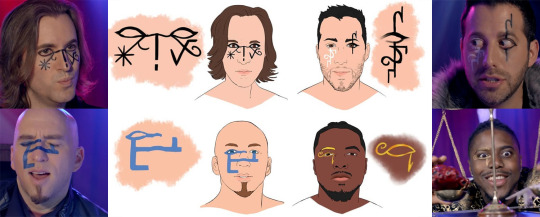

[two people with those face art singing like 🎭🎭]

[What sport would weird black!reader play]

[weird reader has any secret tattoos?]

[wbreader would be one of those ppl that walk the mile]

[wb!reader uses the "is it because I'm black?" card to the batfamily]

[Batman!reader antics]

[Wb!reader fell down the snow bunny hole bruh]

[walking around the manor in ICP make up]

[weird black reader relationship with martian manhunter]

[readers mom and bruce had to co parent]

[WB! Reader have a chunnibyuo phase?]

["TASTE SWEET AND LAST SO LONG~"]

[if magic did run in the family]

[neglected reader goes with slade]

[Black Reader does microlocks]

[black reader and Duke having a small truce just to fuck with the bat family]

["WHY WON'T YOU ANSWER ME!"]

[reader started collecting father figures]

[WEIRD NEGLECTED BLACK!READER HEAD CANONS]

[talia x mother reader]

[wb!reader dating danny phantom]

[Loving Danny is hard]

[Sonic!Reader or Flash!Reader sees after being chased by an alternate version of Mark]

[pairing for a voodoo or vodou!reader, and all of a sudden Bartholomew Henry Allen II]

[reader's mother was dating someone and the reader sees him as a father]

[Danny x wb!reader x Conner]

[youtuber wb! Readers]

[hinking about how maddie, jack and jazz ( danny family ) will accept wb!reader]

[reader and her mom]

[wbReader but is there any chance that they would get permanent fangs]

[being kidnapped by some low-life thug in Gotham]

[Readers mom casually being a yandere for us while she's trying to make the batfam yanderes]

["NO FUN TO FEEL LIKE A FOOL"]

["SHE SO MEAN BUT SO PRETTY!!!"]

[john constantine doctor fate raven and zatanna will be the new reader family that uses voodoo]

["AIM TO SHOOT AIM TO KILL"]

["THE RED MEANS I LOVE YOU"]

[weird!reader ever had a gacha phase]

[get into WB readers' interest]

["DANCE OF THE FATHER"]

[Robin!reader]

[voodoo!reader and girl run]

[voodoo!reader not being herself ever again if she cannot practice her true self]

[love sick]

[Male WB!reader and conner]

["BOI OUTSIDE THINKING HE GROWN"]

["TOP OF MY SCHOOL"]

[Robin Reader with the same style as Moon Girl]

[reader stops caring about the batfam one day they will have their own life]

[MASTERLIST P2]

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Narc

"I am available to provide information or quotes to media, law enforcement, governmental, or non-governmental organizations"

Really? Good to know you'll narc on anyone and their spiritual practices if there's a buck or exposure in it for you. Mate, law enforcement could conceivably come knocking at your door in a resurgent Satanic panic, but you, a white guy in the US, are publically admitting you'll give quotes to cops because you think Vodou is uniquely responsible for human trafficking in some way, and not that folks would, and do use any particular religious, spiritual or social belief or orthopraxy as a method of social control. Again: you, an American white guy, are publicly saying you'll talk to cops about an Afrodiasporic Religion's 'role' in modern slavery, a religion practiced by millions - the majority of whom are people of colour (but not all).

Look, it's obvious you had an intense magical and spiritual experience 20 years ago. You were loud enough then about how you were thrust into a world of what you described as hostile and dangerous spirits. You were loud enough about how you believed the problems of Haiti were down to the lwa as apparently insectile-iike beings that were larva - masks of dead and ancestral people being worn by Horrible Things. You were loud enough about how you believed they sucked the souls out of people: fed on fear, pain, and suffering. You were called out for your racism then. You are being so now, by others. You won't see this, but by all the gods that ever were, mate, of course modern slavery is a problem. But its not just Vodou. There's Christian-trafficking operations, Falun Gong trafficking, etc etc. You've had a massive magical experience that's inflated some ego biases and made either personal or cultural biases come roaring out and distorted your perceptions. That shit happens. One deals with it. One processes. Or one goes full on David Icke. I believe that you believe this. I know you won't see this as anti-blackness influencing you, that you are repeating colonial propaganda. That if anything got into you, it's cultural fear of a non-western spiritual ontology has been riding you for decades. And I also know you'll see this argument as being an apologia for enslavement - that I'm in denial. I'm not. As I have said, this stuff happens. But solely focusing on Vodou, your fervour inspired by a bad magical experience 20 years ago? That's fucked up. It truly is. And then, to set yourself up as an authority. To say you'll give quotes? To media. To governments. To NGOs. To cops.

You, who set yourself up as a teacher? Who has a website that has as its banner: Unleash Your True Self.

Master Magick, Master Your Reality.

A website with "thousands of video lessons on the core teachings of the world's sacred traditions. " We know you've appeared on media, worldwide. On podcasts. On sodding Netflix. Sure. Its your business. I wonder what'd happen if the police took all the data you have on your students? This isn't sour grapes - this is pure practicality here. What would happen if folks who were quietly practing magick were outed in a hostile environment But it's OK to give statements on Vodou and slavery to the powers that be. Isn't it? Because you're saving people. People can make their own judgments. Me? I view that as fundamentally untrustworthy. I wouldn't be happy placing my undoing of standard western materialism in such hands. Like I said, there's a word for that.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

PORT-AU-PRINCE

Although I’d originally planned to style this character after Guede Nibo, I’ve since realized this was a misguided decision. He’s no longer based on Guede Nibo and is supposed to be a member of the Gede who does not exist in the real world.

A full discussion can be found in the middle of this description:

“Port-au-Prince” needs an updated description; I plan to do this at a later time.

Original, outdated description below cut:

RANTING ABOUT THE REAL-LIFE GEDE NIBO (GUEDE NIBO)

Andre Pierre featured Gede Nibo alongside Baron Samedi and Maman Brigitte in several paintings, such as “Les Trois Esprits du Cimetiere.”

Previously, I described Gede Nibo as (quote) “unapologetically queer”. Where did I get the audacity to make such a claim?

Well, there are a number of English language books and other sources that describe Gede Nibo himself as queer. As you may have gathered, I’m a big fan of Eziaku Atuama Nwokocha’s works, and have relied on her research. In Vodou en Vogue, Nwokocha describes him as an “effeminate dandy” who is “honored by queer people”. In Queering Black Atlantic Religions, Roberto Strongman also names Gede Nibo and Erzulie Freda as deities who "have strong associations with queer Vodou practitioners." Strongman’s statement is certainly true with respect to the Erzulies; the question is whether it is also true with respect to Gede Nibo.

Afraid of making the same mistake I did with Baron Samedi, I searched for a Haitian source, as there is a great amount of misinformation spread by English speaking, non-Haitians. Since the Haitian author Milo Marcelin also described Gede Nibo as queer, I stopped there and thought, “so Gede Nibo really is queer…!”

…But it seems I may have made the exact same mistake I did with Baron Samedi afterall.

OOPS!

As far as I can tell, the description of Gede Nibo as “queer” among English-speaking, non-Haitians originates in three major sources:

Gay, German author Hubert Fichte

Gay, American author Randy P. Conner

Haitian author Milo Marcelin

Hubert Fichte conducted his ethnographic work in Haiti during the 1970s. Apparently, Fichte heard Haitian farmers singing a song called “Masisi”, in which the lyrics went “Guede Nibo Masisi!”

He mentions the title of this song in Xango:

“Es gibt einen schwulen Totengott, Guede Nibo, und Anfang November singt das ganze Land, jeder haitianische Bauer die Hymnen auf die Schwulen - »Massissi« - und die ruralen Familienväter vollführen ambivalente Gesten vorne und hinten an ihrer Hose.”

Source: Fichte, Hubert, and Leonore Mau. 1984. Xango. Frankfurt: Fischer. p. 143 https://archive.org/details/xangodafroamerik0000fich/page/142/mode/2up?

An English translation is provided by Strongman:

“There is a gay god of death, Guédé Nibo, and in early November the whole country, every Haitian peasant, sings hymns to the gays— “masisi”—and rural family fathers perform ambivalent gestures at the front and back of their pants.”

Source: Strongman, Roberto. Queering Black Atlantic Religions: Transcorporeality in Candomblé (2019). p. 75

The lyrics of the song are described in Homosexualität und Literatur (Vol. 1):

“Als eine der wenigen Religionen verfuegt der Vaudou ueber eine homosexuelle Gottheit, den Totengott Guédé Nibo, und am Totensonntag singen die Vaudouglaeubigen in der Stadt und auf dem Land: Guédé Nibo Massissi, Guédé Nibo Massissi! – schwuler Guédé Nibo, schwuler Guédé Nibo!”

Source: Fichte, Hubert. Homosexualität und Literatur: Polemiken. Germany, S. Fischer, 1987. Vol. 1. p. 146

An English translation is provided in The Gay Critic:

“Voodoo is one of the few religions to espouse a homosexual divinity, the god of the dead Guédé Nibo, and on Dead Sunday the believers chant, throughout the city and in the countryside: Guédé Nibo Massissi! Guédé Nibo Massissi! – gay Guédé Nibo! gay Guédé Nibo!”

Source: Fichte, Hubert. 1996. The Gay Critic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 118

Interestingly, Katherine Smith observed something similar in 2007, but the chant went “Gede Masisi!” not “Gede Nibo Masisi!”:

“Gede mounts individuals as well as small marauding bands of vagabon who may pound on tombs and yell obscenities at the dead. In 2007, one such group of young men dressed in drag, fellated bones, and danced flamboyantly as the crowed cheered “Gede Masisi!” (Gay Gede!).”

Source: Smith, Katherine. "Dialoging with the urban dead in Haiti." Southern Quarterly 47.4 (2010): p. 83

Hubert Fichte translated the word masisi as a schwul, meaning “gay”, but this is not accurate. Masisi is a slur that has been reclaimed by some within the Haitian LGBTQ community; really, la Communauté M / The M Community.

I have been using words that originate in the Western bourgeoisie, but these are not terms Haitians use to describe themselves - especially those oppressed by race and class. There are similarities between the word masisi and terms used in other non-Western cultures, such as hijra, bakla, okama, and fa'afafine.

As defined by Charlot Jeudy - the former president of KOURAJ who was killed in 2019:

“…the societal definition of masisi is ‘acting as the female partner in a homosexual relationship.’ You can have muscular, manly M persons, but for Haitians, they cannot be called masisi. The word masisi has always been an insult. It makes people uncomfortable for us to use it, but in Haitian Creole, there is no other way for me to describe what I am.”

Source: https://cornbreadandcremasse.wordpress.com/2013/06/16/the-m-community-lgbt-courage-in-haiti/

It’s from 2002, but the documentary Des hommes et dieux contains interviews of several self-identified masisi. Some who identify as masisi would probably identify as “gay” if they were born in America; others would probably identify as “trans” - either, as binary trans women, or nonbinary transfems. Either way, masisi is not synonymous with “gay” or “transfeminine”, and it is important to remember that it’s been used as hate speech.

Fichte was surely incorrect in using words like masisi, schwul, and gay to describe Gede Nibo. There is no doubt in his attraction to women. The question is whether he could be described as “bisexual”, miks, or if he is purely heterosexual - not queer in any respect.

Although he repeatedly describes Gede Nibo as “gay”, one of Fichte’s interviewees flatly denies this:

Ich frage:

—Ist Guédé Nibo Massissi? Schwul?

André antwortet:

—Das ist falsch. Die Götter, die aus zwei Teilen bestehen, sind keine starken Götter. Es sind gekaufte Götter. Man kauft die Götter, um Sachen zu machen, die nicht gut sind.

Source: Fichte, Hubert, and Leonore Mau. 1984. Xango. Frankfurt: Fischer. p. 182 https://archive.org/details/xangodafroamerik0000fich/page/182/mode/2up

Machine Translation:

I ask:

—Is Guédé Nibo masisi? Gay?

André answers:

—That is wrong. The gods that are made up of two parts are not strong gods. They are bought gods. People buy the gods to do things that are not good.

Because I do not speak German, I referred to Herbert Uerlings’ Poetiken der Interkulturalität for context:

Zu den gewichtigsten Ergebnissen seiner Feldforschung gehört, daß Guédé Nibo, einer der Totengötter, die alle traditionell mit Sexualität verbunden werden, ein Gott der Homo- und Bisexuellen ist. Sollte das zutreffen, so wäre es vermutlich eine neue ethnographische Erkenntnis über den Vaudou.47 Die weitergehende Frage an den Priester André, ob »Guédé Nibo Massissi« (X 182) sei, also schwul, wird verneint, aber auf eine Weise, bei der vor lauter offensichtlicher Abwehr Fichtes Vermutung praktisch bestätigt wird: »Das ist falsch. Die Götter, die aus zwei Teilen bestehen [bisexuell oder schwul sind — H.U.], sind keine starken Götter. Es sind gekaufte [schwache — H. U] Götter. Man kauft die Götter, um Sachen zu machen, die nicht gut sind« (X 182). Ein anderer, schwuler Priester dagegen sagt: »Es gibt Götter, die die Homosexuellen verachten, und andre, die sie lieben« (X 194).

Source: Uerlings, Herbert. Poetiken der Interkulturalität: Haiti bei Kleist, Seghers, Müller, Buch und Fichte. Vol. 92. Walter de Gruyter, 2013., p. 282

Machine Translation:

One of the most important findings of his field research is that Guédé Nibo, one of the gods of the dead, all of whom are traditionally associated with sexuality, is a god of homosexuals and bisexuals. If this is true, it would probably be a new ethnographic discovery about voodoo.47 The further question to the priest André as to whether "Guédé Nibo is Massissi" (X 182), i.e. gay, is answered in the negative, but in a way that practically confirms Fichte's assumption through sheer obvious defensiveness: "That is wrong. The gods who consist of two parts [bisexual or gay - H.U.] are not strong gods. They are bought [weak - H. U] gods. Gods are bought to do things that are not good" (X 182). Another, gay priest, on the other hand, says: "There are gods who despise homosexuals and others who love them" (X 194).

I do not know if Uerlings is correct in dismissing the interviewee as “defensive”, but I am grateful for his clarification of the phrase “aus zwei Teilen bestehen”.

Notably, the footnote on the same page states:

47 Ich habe in der Literatur keinen Beleg dafür gefunden. Allerdings notiert Deren zu Guédé: »Er vertauscht die Geschlechter und zieht Frauen Männerkleider und Männern Frauenkleider an« (Der Tanz des Himmels mit der Erde, 1992, S. 128f.), und vermerkt in einer Fußnote: »Es wird zwar selten eindeutig ausgesprochen, aber häufig finden sich Hinweise darauf. daß es sich bei Guedé [sic!] um eine hermaphroditische Gottheit handelt, genau wie Legba« (a.a.O.).

Source: Uerlings, Herbert. Poetiken der Interkulturalität: Haiti bei Kleist, Seghers, Müller, Buch und Fichte. Vol. 92. Walter de Gruyter, 2013., p. 282

Machine Translation:

47 I have found no evidence of this in the literature. However, Deren notes about Guédé: »He swaps the sexes and dresses women in men's clothes and men in women's clothes« (The Dance of Heaven and Earth, 1992, p. 128f.), and notes in a footnote: »Although it is rarely stated clearly, there are frequent indications that Guedé [sic!] is a hermaphroditic deity, just like Legba« (loc. cit.).

It is possible that the German Fichte was mistaken in describing Gede Nibo as queer, and that he mistook his lasciviousness for queer sexuality.

Notably, the Haitian author Milo Marcelin described Gede Nibo as queer in Mythologie Vodou (vol. 2): “Guédé Nibo, mystère mâle et femelle (hermaphrodite), est le protecteur des vivants et des morts.” Similar to the song “Masisi”, Marcelin describes another song that suggests Gede Nibo is himself queer. Naturally the song is sexually explicit, but you can find it in the source provided below, with one of the lyrics being “...Regarde la démarche de Guédé!”.

Source: Marcelin, Milo. Mythologie Vodou: Rite Arada. 2 vols. Port-au-Prince: Les Editions Haitiennes, 1950. Vol. 2, p. 181 & p. 187 https://www.google.com/books/edition/Mythologie_vodou_rite_arada/cjvXAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=%22Regarde+la+d%C3%A9marche+de+Gu%C3%A9d%C3%A9%22

An English translation of this song can be found in: Conner, Randy P. Lundschien, and David Sparks. Queering Creole spiritual traditions: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender participation in African-inspired traditions in the Americas. Routledge, 2014, p. 63 https://books.google.com/books?id=5SINiF0fkqwC&pg=PA63&lpg=PA63

A large section of Conner’s Queering Creole Spiritual Traditions describes “homoerotic, pansexual, and transgender aspects” of Gede Nibo. (p. 94). However, one interviewee denies an association between Gede Nibo and queer sexuality - that being, the Caucasian Houngan Mark Alexander "Aboudja" Moellendorf (p. 64)

Source: Conner, Randy P. Lundschien, and David Sparks. Queering Creole spiritual traditions: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender participation in African-inspired traditions in the Americas. Routledge, 2014

Outside of the sources mentioned above, I have found little evidence that Gede Nibo is himself queer. Rather than Gede Nibo, I’ve found more evidence that the Erzulies are important to members of the aforementioned Haitian “M Community” (see bottom of this post). I have also seen claims that Gede Nibo sometimes cross dresses, but I’ve yet to find a reliable source for this. There are artistic renditions of him proudly displaying his sexuality, but I have yet to see any that show him in women’s clothing, or displaying queer sexuality.

It is possible that the authors listed above are correct in their assessment (except for Fichte, who was definitely wrong). However, there’s a lot of misinformation spread about the lwa outside of Haiti and New Orleans, which arises from foreigners misunderstanding the culture and traditions of Vodou. Since I have already made mistakes with Baron Samedi and Maman Brigitte, I could be wrong about Gede Nibo too. If this is the case, I apologize for spreading misinformation about him being queer.

It is also possible that the above was true at some point in the past, but not in the present. Afterall, Fichte and Marcelin wrote during the mid 20th century, and traditions evolve over time.

…Well, might as well start ranting about my Deviantart OC!

RANTING ABOUT MY DEVIANTART OC

This character’s name is “Port-au-Prince” - named after the capital of Haiti.

Unlike the real-life Gede Nibo, “Port-au-Prince” is just gay, and a drag queen. His personality and interests are similar to Angel Dust, where he is openly gay and flamboyant in his mannerisms. As it is a slur, I have been avoiding the word masisi, but it is likely he would identify as part of the “M community”. Where Alastor is (presumably) the son and/or grandson of New Orleans Voodoo Queen(s), “Port-au-Prince” is a houngan - an extremely powerful one at that. His appearance and personality were inspired by the individuals featured in the documentaries Des hommes et dieux and Paris is Burning.

I made this decision for these reasons:

To integrate him into the pre-existing world of Hazbin Hotel, as a counterpart Angel Dust

To represent the Haitian “M community”, who experience intense prejudice and violence, but find sanctuary in Vodou

To differentiate him from the real-life Gede Nibo

As a tribute to the association between the Gede and gender/sexual queerness

Here’s a list of sources to back this third point:

Nwokocha, Eziaku Atuama. Vodou en vogue: fashioning Black divinities in Haiti and the United States. UNC Press Books, 2023.

Conner, Randy P. Lundschien, and David Sparks. Queering Creole spiritual traditions: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender participation in African-inspired traditions in the Americas. Routledge, 2014

McAlister, Elizabeth A. "Love, sex, and gender embodied: The spirits of Haitian Vodou." Love, sex and gender in the world religions (2000): 129-146. https://africultures.com/love-sex-and-gender-embodied-the-spirits-of-haitian-vodou-5719

Smith, Katherine. "Dialoging with the urban dead in Haiti." Southern Quarterly 47.4 (2010): p. 83

Hence, the decision to make “Port-au-Prince” a queer drag queen.

As a counterpart to Angel Dust, he has a dual gangster-ballroom/voguing theme to him, where he runs his own ballroom house. Although his roots are from Haiti, I think it would be interesting if he was part of the diaspora, where spent much of his human life in New York. This too helps integrate him into the pre-established world, where many characters are former humans who lived during different time periods of American history. It also establishes another parallel between him and Angel Dust, who is also from New York. I was picturing his house as being a mix of Black transfems (more broadly, feminine of center AMABs) and Black transmascs (more broadly, masculine of center AFABs), who are all former humans. They also double as a battle force that could be recruited in a similar manner to the Cannibals in Cannibal Town, where they have strong healing and fighting abilities.

Port-au-Prince’s drag queen persona is inspired by Aaliyah as Queen of the Damned. In addition to Angel Dust, it would also be possible to establish a connection between him and Sally Mae, if she has any interest in drag. He is the adoptive son of the “Baron of the Dead” and “Gran Maman”, my other DeviantArt OCs who I drew here: https://www.deviantart.com/thegirlwhodidntsmile/art/Lavi-and-Lanmo-1073560801

This was inspired by the description provided by Roberto Strongman, where he writes:

“In Vodou lore, Gédé Nibo is a young man who was killed violently. Therefore, he has a particular association with those who die young. Once in the spirit realm, Bawon Samedi and Gran Brigit adopt him. In demeanor he is comical, lascivious, witty, and effeminate. In appearance, he is a dandy.”

Source: Strongman, Roberto. Queering Black Atlantic Religions: Transcorporeality in Candomblé (2019). p. 74

It would be imperative to run a concept like this by an expert on Haitian Vodou, to determine whether his portrayal is respectful or not. If it’s inoffensive, I think it would be cool if the three characters inspired by “Les Trois Esprits du Cimetiere” formed a “sexually complete” trinity: one male, one female, and one androgynous. But this may be problematic, as it could mislead audiences into thinking the real-life Gede Nibo is gay. Another approach would be to remove his drag queen persona, and make him a straight guy who has gay friends. Instead of Gede Nibo, the Erzulies could serve as inspiration for a character that embodies LGBTQ acceptance in Vodou.

RANTING ABOUT THE ERZULIES (EZILI DANTOR AND EZILI FREDA)

The Erzulies are important to the Haitian M Community - especially when accounting for race and class. Intense homophobia persists among the oppressed - who are denied access to higher education, and often understand sexuality/gender through religion. Those despised as masisi and madivin are tolerated in Vodou, where many houngans are themselves part of the M Community.

There is a fascinating documentary called Des hommes et dieux, which examines this very community. Several interviewees assert that Ezili Dantor has the power to make a person - male or female* - homosexual. It is for this reason that interviewees insist they were “born this way”, and that their parents - who might have otherwise rejected them - accept them as they are. I was particularly moved by statements from the interviewee Blondine, where the English captions read: “[My father] realized it came from voodoo. So he had to accept me. I’m like this because of the spirits that he’s serving. The loas decided I would be a girl. I was born this way.”

Granted, one interviewee (the houngan named Fritzner who self identifies as masisi) rejects this belief, considering it blasphemous. Either way, it is unanimous that the Erzulies protect the M community. Those hated as masisi are loved by the lwa, become their houngans, and are called les enfants d’Erzulie - “Ezili’s children”.

*I specify the category of sex, as the invisibility of “female masculinity” (including, masculine female homosexuality and the transmasculine spectrum) rears its ugly head. The “M Community” has language for transfems and feminine gay men; there are no equivalent terms for transmascs and masculine of center lesbians. As such, I have struggled to find information/research about the inverse phenomenon of “inverted” or “radically masculine” identifying members of “the feminine sex”; certainly not within the Black proletariat. Haiti is by no means unique in this regard. This disparity is found in many cultures all over the world - especially among the oppressed classes.

In any case, Erzulies are not just important to those of “the masculine sex”, but those of “the feminine sex” as well. Eziaku Nwokocha documents her personal experience as a Black queer femme with Ezili Dantor in The ‘Queerness’ of Ceremony. Zora Neale Hurston also briefly mentioned the importance of Ezili Freda to women who “tend toward the hermaphrodite” (i.e., with queer tendencies) in Tell My Horse. Unfortunately, I have struggled to find information about the Haitian equivalent of studs, aggressives, trans men, etc… due to the aforementioned issue of invisibility. Notably, none of the women at the temple Nwokocha visited were masculine-presenting, except for one visitor who dressed in red to honor the masculine lwa Ogou.

Previously I had been under the impression that Erzulie Dantor was associated with lesbians while Erzulie Freda was associated with the transfeminine spectrum. Just, a completely false dichotomy! WOW is there a lot of misinformation spread about Vodou! The Erzulies are associated with the transfeminine spectrum, as they protect femininity in all its manifestations. In addition to Black lesbians/bisexual/queer women, Erzulie Dantor is important to Black transfems, as she is depicted as a dark-skinned Black woman. That’s why people in the Haitian M Community love her, as a goddess of love, luck, and protection. For these reasons, I think it would be really cool to try to work Erzulie-inspired character(s) into this fictional world; granted, it presents more of a challenge to fit them into this setting, since they are not spirits of the dead. The easiest way to do so would be to have one of the Erzulies replace Mother Mary, if Mother Mary does not exist in the fictional mythology of Hazbin Hotel.

If you want to learn more about this, I highly recommend watching Anne Lescot & Laurence Magloire's documentary Of Men and Gods / Des hommes et dieux (2002). It’s available on Kanopy for free, and for rent Vimeo. Additionally, Eziaku Nwokocha, Roberto Strongman, and Omise'eke Natasha Tinsley have written several books and papers on this topic. Here are a few sources that can be accessed online:

Tinsley, Omise’eke Natasha. “Songs for Ezili: Vodou Epistemologies of (Trans) Gender.” Feminist Studies, vol. 37, no. 2, 2011, pp. 417–36. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23069911. Accessed 4 Aug. 2024.

Strongman, Roberto. "Cross-Gender Identifications in Vodou." In Defying Binarism: Gender Dynamics in Caribbean Literature and Culture. Virginia University Press. Ed. Maria Cristina Fumagalli. https://www.blackstudies.ucsb.edu/sites/secure.lsit.ucsb.edu.blks.d7/files/sitefiles/people/strongman/NewCrossGenderIdentificationsVodou.pdf

Nwokocha, Eziaku. “The ‘Queerness’ of Ceremony: Possession and Sacred Space in Haitian Religion.” Journal of Haitian Studies, vol. 25, no. 2, 2019, pp. 71–90. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26926664. Accessed 6 Aug. 2024. https://eziakunwokocha.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/The-Queerness-of-Ceremony.pdf

SIDE NOTE:

Rereading this, I fear I may come across as judgemental of writers like Fichte and Conner. That is not my intent! I do not think it is fair to judge these authors harshly. It is easy to take the internet for granted. I think these authors did the best they could with the technology that was available to them, but mistakes could have still been made. The fault does not lie on them, but myself for having been careless in my research.

#i actually tried to fit this character into the art style of the show... it's just a rough concept sketch but you get the idea#hazbin hotel oc#port au prince (hazbin hotel)#I wrote this sort of as a follow up to an earlier post where I didn’t have time to research LGBT rights in Haiti#the oppression and hatred of the M community is as intense as I thought it was. but it is remarkable how Vodou offers a space of tolerance#also for some reason I forgot to control for class and compared the bourgeoisie of Haiti against the underclasses of my#that was fucking stupid of me! why did I do that???

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palo Mayombe: Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality — Lawrence Talks!

“This complexity described in the Bantu-Kongo word for person, muntu is a ‘set of concrete social relationships ... a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being.’ The person is contextualized as a system participating in other systems, a pattern, a ripple that is sourced and from a source.”

— Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, African Cosmology 42

Dr. Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, a Congolese native and scholar of African religion, captures the essence of Kongo cosmology with this quote, and from this cosmological structure lies the roots of the African diasporic religion Palo Mayombe. Just as a person is “a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being,” ancestral reverence and inclusion positions humans through a multitude of bodies that have come before them. Ancestral veneration is at the core of many African Diasporic spiritualities. Many individuals who grew up in traditional Christian churches are leaving beliefs of Christendom in search for traditional religions that help them connect with their ancestors. Religious and spiritual systems like Ifa, Santeria, Vodou and Conjure have been popularized, sometimes in negative ways by the media, but for the most part these are the spiritualities that people turn to first in their exploration of African traditional religions (ATR). And what is known of Palo Mayombe by the general public is not a large amount of information by any chance. A Google search locates some articles which picture Palo as the “dark side” of Santeria, which is far from the truth. However, to understand Palo as a distinct spiritual system outside of other African diasporic religion, one must understand its BaKongo cosmological foundations.

History of ancient Kongo cosmology

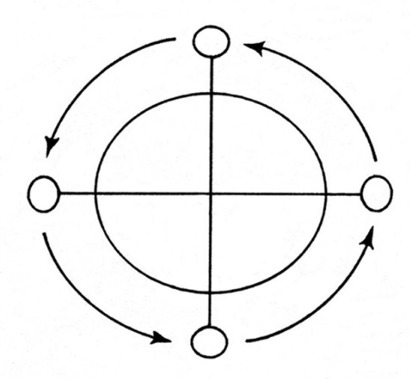

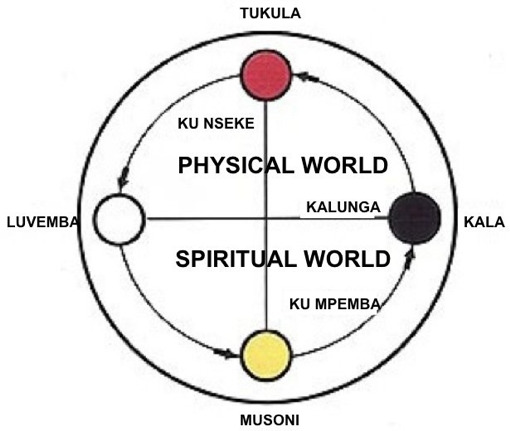

Figure 1: Kongo cosmogram (dikenga)

Fortunately, there is a symbol that captures the essence of Kongo cosmology. The Kongo cosmogram is a cosmological symbol that represents the very patterning of the life process. This symbol is a pre-colonial representation of the cosmogram, as it was conceptualized before European colonization in 1482[1]. It is called the dikenga in the KiKongo language, literally meaning “the turning;” it stands for the cycling of the sun around four cardinal points: dawn, noon, sunset, and midnight when the sun is shining in the world of the dead. Composed of a cross, a circle, and usually arrows, this symbol was found in Kongo material culture well before the contact of colonial Christianity and its cross motif. Anthropologist Robert Farris Thompson, a scholar of Kongo art and religion, says that the “dikenga represents the ultimate graphic design, containing key concepts of Bakongo religious belief, oral history, cosmogony, and philosophy, and depicting in miniature the Bakongo conceptual world and universe” (Thompson 110). The key principle of the dikenga is that nothing ever survives “intact” because nothing ever survives in a fixed form. It is this spiral that is the basic element of Kongo spirituality.

Figure 2: Dikenga

In his seminal piece on Kongo cosmology entitled African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Principles of Life & Living, Dr. Fu-Kiau explains the motion of the dikenga as the process of ancestralization, of dying and being reborn as an ancestor, through the heating and cooling of existence. This explanation of death and ancestralization is at the core of Palo Mayombe.

Origins of Palo Mayombe

Palo Mayombe is a Kongo derived religion from the Bakongo Diaspora. This religion was transported to the Caribbean during the Spanish slave trade and sprouted in Cuba mostly and in some places in Puerto Rico in the 1500. As the enslaved were forced out of their homelands, their beliefs went with them. Spanish colonialists in Cuba initiated a strategy in the sixteenth century to create mutual aid societies, called cabildos or cofradías, which served to cluster Afro-Cubans into different ethnic categories. This was a strategy of “divide and rule” designed to foster social differences across groups within the enslaved population so that they would not find a unifying focus through which to rebel against the colonial government. In contrast to the extensive blending of diverse African cultures that would be seen in Haiti and Brazil, Cuban cabildos contributed to rich continuations of Yoruba culture in the development of Santería and to largely separate developments of BaKongo beliefs in Palo Mayombe (Fennel). Elements of Catholic beliefs were incorporated into both Santería and Palo Mayombe due to the imposition of the Spanish colonial regime and the cabildo system.

Figure 3 Palo Mayombe Ceremony

Palo Mayombe is very nature-based. Although most African Diasporic religions base rituals and practices in nature, palo (meaning “stick” or “segment of wood” in Spanish) solely depends on the material elements of nature to access the spiritual realm. In Cuba, the Kongo ancestor spirits are considered fierce, rebellious, and independent; they are on the “hot” scale of natural forces. Just as the importance of ancestralization mentioned above, the ancestors are present and inclusive in the practitioner’s life. Nzambi Mpungo is the greatest force in which paleros or paleras (Palo practitioners) call God. Nzambi Mpungo is literally the first ancestor, the initial iteration which all human life flows. Nzambi was viewed as having created the universe, people, spirits, transformative death, and the power of minkisi (ritualized, material objects). The Godhead was thus viewed as being removed from mortal concerns, and supplications were made instead to the ancestor spirits or the intermediary spirits created by Nzambi. Below Nzambi are the mpungus (elemental forces), the ancestors, and the spirits of natural forces (Bettelheim). Each mpungu is similar to an orisha from Yoruba culture due to shared African derived origins, but the two are not the same entity by any means. The mpungu are Afro-Cuban spirits, specific to their diasporic groundings and to the lands of the Diaspora. However, due to their origin

The material tools of Palo Mayombe

Cigars are used to enter into a trance-like state in order to more easily connect with spirits. Special machetes and chains are also used in spirit pots. Candles and rum are essential elements for any Palo ritual. The nganga is used to describe an iron cauldron filled with dirt and specialized sticks; this aids the palero/a in communication with the spirit. In Central America, Cuba and the Caribbean, this cauldron is called a Nganga-Prenda because the culture of modern day and the influence of Latin American's spiritualism in Palo Mayombe.

Figure 4: Prenda de Lucero

The Muertos are important entities in the Palo religion. The house of the dead is where the Palo spirits and the ancestors reside. As illustrated through the Kongo cosmogram above, Palo cosmology does not believe in death, but a continual cycle through various forms. It is the process of ancestralization that makes communication with the spirits of the dead accessible. In the Kongo tradition, ancestors, who have access to invisible forces, have the duty to protect the living. In exchange, the ancestor’s descendants have the obligation to take care of the ancestor’s memory and to venerate their earthly representation. This is why bones are another central tool in Palo. After a person has passed, the bones remain, and the bones carries the essence of a soul long after a person is gone. Bones are thus a sacred item in Palo Mayombe and are usually incorporated in Palo rituals. Usually an ancestor altar is an essential piece in the house of a palero/a, along with offerings of food, drink, and special itemize to venerate their ancestors.

Like many ATR’s and magical system, initiation of some kind is needed in order to practice. Guidance from the elders of the religion is highly encouraged, especially since the ways of the spiritual system is nothing like physical realms.

Palo Mayombe and Other Religious Connections

The influence of Palo Mayombe can be found in Central America, Brazil, and Mexico and in the United States. There are different sects of Palo (Palo Monte, Christian-based Palo, Jewish-based Palo) that come from different lineages and distinct engagements with the cultural environment around the practice. There is another Kongo-derived religion in Brazil is Quimbanda, which is a mixture of traditional Kongo, indigenous in India and Latin American spiritualism. Palo Mayombe is the engagement of Kongo influence in the Caribbean and the wider Diaspora. It has its own priesthood and set of rules and regulations. Rules and regulations will vary according to the Palo Mayombe house to which an individual has been initiated into.

Some people who practice Palo might mix other African-derived systems, like Ifa, Vodou, or Santeria, but Palo is a religion in its own right. For example, Yemoja, the orisha of the ocean and motherhood, may be seen as the same energy as Madre de Agua, the mpungo of the ocean and of motherhood. Although these spirits may have similar functions within the religions, they are two separate entites from particular cultural origins and with specific needs. It is quite common for spiritual seekers to be initiated in multiple religions, so it is of great importance to make sure each path is approached. Although there are other religious elements in Palo, it is all included in the practice and not separated within the religion. When Portuguese missionaries brought the message of Christianity to the Kongo/Bantu, the natives embraced it…while continuing their own native practices (Jason R. Young, Rituals of Resistance). So, this pattern of centripetal inclusion is also present in Palo Mayombe. As Iya TeeDee Oshún, a priestess of African diasporic religions, commented in a recent Facebook post:

“Palo is a beautiful road for those of us that it is for. It's also not just some shit you get done real quick before you ‘elevate’ because that's what Iya's spirit guide said to her in the shower. (Not making that up at all.) It's definitely not Iya nor Baba's "witchcraft pot" in the closet or behind the washing machine or above the grease stain in the garage. It's rarely what I hear when people talk to me in Yorabalese” (2019).

Iya’s mention of “Yorbalese” speaks to a common trend of people in the Diaspora making all of African-derived religions about orisha Ifa/Nigeria, but Palo is of the BaKongo Diaspora. The only system close in origin and practice to Palo is African American Hoodoo, which uses similar elements of the heating and cooling of herbs in spiritual work.

Conclusion

When one decides to take a step into the spirituality of Palo Mayombe, the journey really is a deep engagement with their ancestors and with the raw elemental forces of nature. It is a spiritual awareness that provides protection for the community and the self. The ancestors are the root of one’s existence; the root is the culminating point from which all life springs. This Afrocentric view of cosmology in which Palo Mayombe is grounded, deals with the consciousnesses of nature and of ancestry. Anyone who claims Palo Mayombe as a “dark” or unorthodox religion does not understand the Kongo origins of which Palo operates.

[1] The Kongo cosmogram is a pre-Christian symbol, but due to the iconography of the Christian cross, many people overlap their meanings

#Palo Mayombe Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality#Palo#ATR#Congo#African Cosmology#Ancestry#African Religions#IFA#Palo Monte#Kongo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

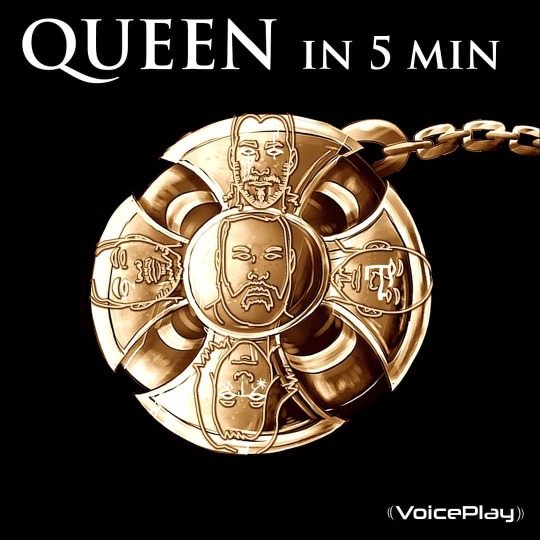

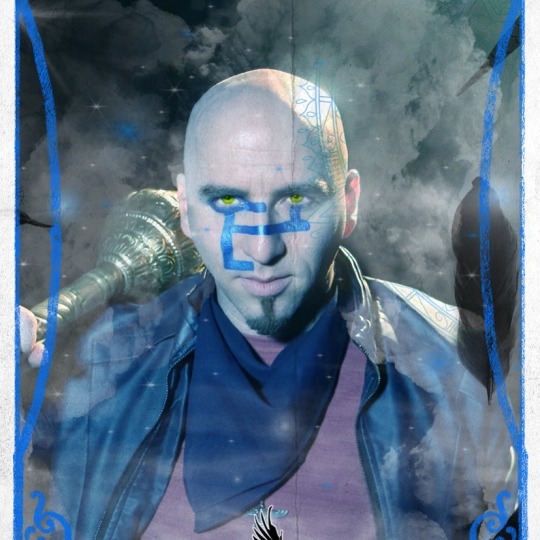

Queen in 5 Minutes — VoicePlay music video

youtube

The late, great Freddie Mercury is often quoted as having said, "Do anything you want with my music, but never make me boring." VoicePlay certainly took that sentiment to heart for this medley of memorable Queen songs, as well as the dramatic visual tale they made to go along with it. A battle for Earl's (after)life plays out in a suitably theatrical setting. Who will win?

Details:

title: Queen in 5 Minutes

original songs / performers: all songs by Queen — "Bohemian Rhapsody"; [0:32] "Play The Game"; [0:54] "Somebody To Love"; [1:20] "We Are The Champions"; [2:20] "Another One Bites The Dust"; [2:37] "We Will Rock You"; [2:45] "Under Pressure" with David Bowie; [2:52] "I Want to Break Free"; [3:14] "Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy"; [3:32] "Play the Game" reprise; [3:48] "Bohemian Rhapsody" reprise; [4:16] "Radio Ga Ga"; [4:21] "The Show Must Go On"; [4:45] "Don't Stop Me Now"

written by: "Bohemian Rhapsody", "Play The Game", "Somebody To Love", & "We Are The Champions" by Freddie Mercury; "Another One Bites The Dust" by John Deacon; "We Will Rock You" by Brian May; "Under Pressure" by Queen & David Bowie; "I Want to Break Free" by John Deacon; "Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy" by Freddie Mercury; "Radio Ga Ga" by Roger Taylor; "The Show Must Go On" by Brian May; "Don't Stop Me Now" by Freddie Mercury

arranged by: Layne Stein & Eli Jacobson

release date: 23 November 2018

My favorite bits:

recreating that iconic Bohemian Rhapsody intro

J.None's fantastic control, flipping between chest and head voice as he extracts Earl's heart 🫀 ⚖️

that smooth scoop from Earl on ⇗ ♫ "take a loooOOOK" ♫ ⇗

Geoff going full Chris Cornell at the start of "We Are the Champions" before dropping back into the underworld

J.None shoving the sword into Layne's hands to get him more involved as he sings about ♫ "fighting til the end" ♫

Eli's busting out that rock grit for "We Will Rock You"

Layne beatboxing the iconic stomp-stomp-clap rhythm rather than breaking viewers' immersion in the scene

Earl repelling everyone through the power of belting

the dismissive face Geoff makes at Eli as he continues the "Under Pressure" bass line into "I Want to Break Free" (a more serious take on the "Ice Ice Baby" bit from their "Old School Rap" medley)

Earl's plaintive vulnerability during "Lover Boy" solidifying into defiance for the return to "Bohemian Rhapsody"

the backing vocals pleading with Earl to ♫ "play the game" ♫ so they can guide him onward

ramping up into full concert mode as they form a line at the front of their "stage"

high tenor air guitar! 🎸

Eli and J's subtle counterpoint line from "Radio Ga Ga"

using "The Show Must Go On" to signal Earl's decision to return to the world of the living

Trivia:

○ The man in the hospital framing scenes is Earl's husband, Nick. He has appeared on screen in a few VoicePlay videos, as well as doing production work on many more.

○ The four avatars of death come from various religious traditions:

Guardian (Layne) is an anthropomorphized version of Cerberus from Greek mythology, the multi-headed hound (hence the fur coat) who protects the gates of Hades.

Anubis (J.None) is the guardian of the dead and assessor of souls in the Egyptian pantheon, often depicted as a jackal.

Yama Nirvana (Eli) represents the Hindu god Yama, responsible for death, justice, and punishment of sinners in the afterlife.

Baron (Geoff) is an interpretation of the spirit Baron Samedi, master of the dead and resurrection in Haitian Vodou.

○ The guys' distinctive makeup and wardrobe were designed by artist Leon King. Of the four, J.None's costume changed the most from concept to execution, but each of them was tweaked a bit.

○ Leon also drew the central pendant element for the cover art.

○ The YouTube description includes the inscription, "We humbly dedicate this video to the music and memory of Freddie Mercury. The show must go on."

○ Some fans have embraced a headcanon that this video is a sequel to "Panic! in 4 Minutes". They theorize that Earl is in the hopital because he was injured by the explosion, and the avatars of death are manifesting as his bandmates within his unconscious mind. This hasn't been confirmed or denied by any members of VoicePlay, but it's a fun idea.

○ This video reached a million views on YouTube the following August.

○ The streaming audio version is split into two parts, "The Arrival" and "The Return", with the divide falling between "I Want To Break Free" and "Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy".

○ The complete track was later included on VoicePlay's "Citrus" album, which compiled most of the songs they recorded from 2017-19. Because the individual songs had already been made available digitally, that album is exclusively a physical item that can only be purchased at live shows or through their website.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I Wanna Talk Vodou in Castlevania: Nocturne But First...

We gotta talk about Magic in Castlevania as a whole. The problem though is that there's not much new to say that one can't grasp from watching the show and being exposed to other media which includes magic (which is like what? 99% of all fantasy fiction?). The show doesn't go out of its way to explain anything about how magic works but then again what is there that needs explaining? Pretty brown lady does some finger stuff and something goes boom or sparky, a couple of guys can raise the dead, something something levitating sword, something something magic portals, something something something something magic exists, just deal with it. What seems to be of interest to the show is how magic is used by each character and what that says about them, their roles in the story, and their arcs.

Sypha, for example, is the powerhouse of the main trio boasting the most diverse and deadliest set of abilities since her magic consists of control over fire, water/ice, and lighting. This has led her to be key to some of the team's wins over various vampires, creatures, or even humans. While Trevor may struggle with one enemy, she could be handling several at once. This dynamic is most evident during the fight with Dracula as Daddy Drac could handle his son and a Belmont but Sypha was a wildcard that he knew he would have trouble. Even if you can argue that by herself she could never beat Dracula, her presence was the edge that the trio needed. But what does that say about her? She's adventure- loving, brave, and her knowledge as a speaker gives her insight where Trevor's experience and Alucard's vampiric and scientific knowledge might fail them. However, none of this is more important, I think, than her role as the "heart" of the team. Trevor and Alucard are cynics held back by their respective familial traumas to see the world for what it is, she provides optimism and love for life and humanity that both lacked and this aspect of her character enabled them to think in ways they weren't able to before. Like her magic, she's able to take the elements of those she loves and make them into something more powerful than what they seem capable of. Get it?

You can basically extend this analysis to most of the cast. Nothing entirely too deep either for people whose hobbies involve over-thinking about the stuff they watch. You see, my thing is magic in most fiction isn't really... magic and that has some bad implications for Annette's Vodou in Nocturne. Why? Because it's basically just science when physics is weird and wonky. That's not even off brand for it either, we all know that one quote about advanced enough science being indistinguishable from magic but even before this quote some Italian guy name Giovanni Pico della Mirandola said that magic was the practical application of natural science. The video I reblogged of the guy moving a crowd of bugs from the light in his yard to the streetlight is absolutely magical... but pretty easy to explain using bug psychology. Hell some scientists go out of their way to find miracles from various faiths (mainly Christian though) and try to explain them just for funsies (or apologetics) to stretch the limits of what science can explain and what it can't. This is all well and good for a view of magic that is centered around the idea of it being manipulation of phenomena but it kind of runs against other perspectives that see magic and adjacent activities as more than just phenomena. Take, for example, the existence of deities. If there is a fire god, what is fire magic? Does the magic come from the god? Do you need to have a special connection with the god to do the magic? Is it possible to become a fire god if you're powerful enough or is there something more to the title? What separates what the god does from the magic a human performs? If not a god, what about a fire spirit? Is there a difference between a spirit and a god? Do spirits take on the form of the element itself or are they separate from it? Notice how me adding in the element of a conscious thinking entity now muddies the waters a bit. Now what would be a simple "application of science" is now a question of relationships between two persons.

Let's apply this back to Sypha. Sypha's magic is manipulation of fire, lighting, and water. Assuming that elemental spirits/deities exist, how did she acquire such skills? Does she pray to them, bargain with them, worship them? Is there a ritual involved that she has to perform? It's a bit of a headscratcher if we think on it but I don't believe that she's dealing with any external entities with her magic and I'm certain the writers intended for her magic to be as straight-forward as it appears. And notice how the other magic in the show fit a similar simplistic "mold"? Alchemy and Forgemastery are basically in the same "do a thing then a thing happens" territory that Sypha's elemental kinesis fits in. But just like how adding in a "second party" into the mix of the magic throws a kink in how we're supposed to perceive Sypha's magic, doing so for Alchemy and Forgemastery does the same. In fact, Alchemy stops being Alchemy the moment you start adding in cosmic beings because it practically ruins the point of alchemical work. So in a world where all the magic is connected together by a common "science-y" theme to it all that's supposed to enable us to shut off our brains and just accept said magic without explanation because we trust that there is one, how do you fit magic where entities are a part of how everything works? And when the magic you're introducing is from a faith that's been demonized to hell and back, how do you make it fit into your world with good representation? Well, for Nocturne, the answer is not terribly but not all that good either...

#castlevania netflix#castlevania nocturne#castlevania anime#sypha belnades#magic#annette castlevania

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: New World Witchery

New World Witchery : a Trove of North American Folk Magic - Cory Thomas Hutcheson. Llewellyn Publications, 2021. English.

★★★★ (4/5) This book has as many flaws as reasons to adore it, and so this may prove to be a very lengthy review. TL;DR: at the bottom.

Picking this up in the bookstore I was very excited. Hailing originally from Europe, now living in Alaska, and practicing primarily European folk magic, this seemed like a fantastic book to bury myself in and learn about folk magic of my new home continent. Delving into it I was immediately captivated. The structure of the book is very very creative, and the way the author writes really takes you away. I appreciate the inclusion of not just theoretical material, which may fall flat to the reader due to a number of factors, but also biographies of magical practitioners and the sections that encourage you to apply what you read in real life. That said, as an experienced practitioner holding the 'worksheets' up to my own work, it felt a tad empty. The author, though very good at relaying folkmagical tradition, doesn't impart a lot of folk magic's cosmology or quasi-scientific historical approach into the recommended rituals. This has benefits and drawbacks. I think that for an experienced practitioner that sticks to folkmagical principles and a set cosmology, the recommended magical practice is next to useless. However, a beginner practitioner, or somebody looking for direction and inspiration, may find a wealth of new ideas in these sections.

Of course there are the necessary socio-political issues to consider in a book review. I would not discount this book on this account, but I have a few notes. The author undeniably covers his bases. He explicitly warns against the drawbacks of such an extensive piece of literature, of it also including hoodoo, vodou, root working, jewish, native, etc practices. He makes a strong statement against appropriation. But I am a nitpicker, was born one, unfortunately. Some things I noticed: The author does recommend using both 'sage' and palo santo during the worksheet sections a few times. While he takes a stance against appropriatively using materials and rituals, I think it could use a bit more stressing that these plants (salvia officinalis and sandalwood) are endangered or close to it and shouldn't be used by people unable to obtain and use sustainably. The author recommends offering tobacco to ancestors, tobacco being a topic of hot debate presently as to whether or not the use of it in ritual should be reserved for Native American peoples. The author refers to his own magic as 'mojo' once and seems to use Hoodoo tradition fairly freely. Take that as you will. The author started the book off very very careful not to call Native Americans the I-word unless directly quoting something, but appeared to get more casual about that toward the end. Author refers to both mythical witch gatherings and real life festivals a 'witch's sabbat(s)', something I consider to be antisemitic. Author recommends taking a volunteering job cleaning graves to collect graveyard dirt without breaking any laws. Dubious? All that said - I can't knock the book for any of this. The information is good, and the book is well written. Ultimately we can never expect to agree on socio-political progression all the way with one another, and the author seems conscious about liberation for all and respectfully applying his knowledge of various traditions.

The bibliography is good, with only a few eyesores. For this section I ought to explicitly mention I have something that could rightly be referred to as a personal vendetta with Western Esotericism and its derivatives, which is why I react to certain types of modern magic as though I were allergic. All of the 'negatives' I'm about to outline are purely subjective and based on my irrelevant ass opinion. The author occasionally references and appears to hold in high regard such authors as Judika Illes and Scott Cunningham, who are undeniably primarily Wiccan authors, or at the least authors geared toward contemporary practitioners, not folk practitoners. The likes that spell it 'magick'. I should also mention that while the author takes a very neutral stance on Traditional Witchcraft (this in reference to Wicca and the like), he does include such things as the Rede and the Wheel of the Year, which he dubs "deeply agricultural." I just had to bite my tongue and keep reading.

Finally I would like to note that the book, though it refers to itself as about all of North America, pretty much only covers the Atlantic half of North America. In fact, I believe the West Coast only gets mentioned in passing twice, both times when offhandedly mentioning Bigfoot/Sasquatch. This makes sense, on the one hand: the richest folk-magical traditions are there. But on the other: the West Coast, though lacking in such big communities of traditional practitioners, has a rich history of spirituality and magic as well, mostly from the Native peoples here and, in Alaska, from Russian colonists. If the book didn't also discuss Native traditions of the East Coast and Midwest, I wouldn't be salty. But it does, and I would've liked to see a bit more discussion of the West and the Arctic. It would've fit in!

All of that said, I thoroughly enjoyed this book. It certainly isn't the type of work you're supposed to read front to back over the course of a few days, but that is exactly what I did and I still liked it! I think the information presented is overall very good, and should be held up to light only as much as any other source should be. Cross-reference, kids! Something I noticed as I worked my way through is that this book would lend itself exceedingly well to being used as a textbook, due to its structure. I wouldn't recommend this book to an ultimate, bare-bones beginner who has no idea how to research and what to look out for yet, and I wouldn't recommend this book to an already very experienced practitioner looking to truly severely deepen their knowledge. But I would recommend this book to a team of them - an advanced mentor able to use this book as a textbook for a student, capable of helping them discern between appropriate and inappropriate conduct, and giving them direction in their early stages. TL;DR: This is a great book. Cross-reference as you would with any other resource, and be sure to contemplate your own ethics and what heritage you are and are not entitled to. I would recommend this book to: - Mentors teaching beginners; - Novice practitioners with some pre-existing knowledge, that are confident in their abilities to cross-reference; - Practitioners in need of some direction or inspiration; - Practitioners that have a hard time finding magic in their native surroundings. Maybe pass on this book if you are... ... from the West Coast and only interested in the West Coast; ... not confident in your ability to cross-reference; ... a true beginner with little to no pre-existing knowledge and cosmology; ... a well-established North American folk practitioner looking for a deep inquiry into the nitty gritty of New World folk magic; ... unaware of appropriate conduct and social issues in the magical community.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Respect.

#new orleans voodoo#haitian vodou#Voodoo priest#original art#digital art#Voodoo sign#spiritual quote#like and/or reblog!#follow my blog#ask me anything#traditional rootwork#google search#vodou quote#voodoo quote#daily qoute

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

How a Voodoo Magic Specialist Can Help You Accomplish Your Goals?

When achieving our goals, we often seek assistance from various sources. From motivational quotes to guides to motivate us, we discover diverse paths to attain success and remove our stumbling blocks. However, visiting a renowned specialist in voodoo magic in Melbourne can also help you when you need the most. Voodoo, rooted in ancient African traditions, is a spiritual practice that helps people manifest their desires. In this blog, we will explore how a voodoo magic specialist can be instrumental in helping you reach your objectives in life.

What is Voodoo Magic?

Voodoo, also known as Vodou or Vodun, is a religious and spiritual practice rooted in Africa. It encompasses diverse beliefs and rituals connecting with deities, spirits, and ancestors. Voodoo practitioners believe that the spiritual realm can impact the world around us, and by channelizing this power, they can bring positivity to their lives.

Harnessing the Power of Intention

One of the fundamental aspects of voodoo magic is setting clear intentions. An expert practicing it can guide you in articulating your goals with utmost clarity. Helping you identify your desires and understand the underlying motivations enables you to establish a strong foundation for your journey towards success. Setting intentions is crucial as it aligns your conscious and subconscious mind, paving the way for focused and determined action.

Rituals and Spellcasting

Voodoo magic practitioners employ rituals and spellcasting to manifest desires. They establish a connection with the spiritual realm through specific ceremonies and offerings.

A specialist in it such as African Psychic Mr Abraham possesses the knowledge and experience to design and perform rituals tailored to your goals. Whether attracting love, improving financial prospects, or enhancing personal growth, they have the expertise to create and execute practices that align with your aspirations.

Harnessing the Power of Energy

The ritual recognizes the importance of energy in achieving goals. A voodoo magic specialist understands the intricate workings of power and can help you harness it to your advantage.

They can provide you with techniques and rituals to clear negative energy, enhance positive energy, and create an environment conducive to realizing your goals. By working with you to balance and channel your energy, they empower you to achieve optimal results.

Overcoming Obstacles and Challenges

The path to success is often filled with obstacles and challenges. A voodoo magic specialist can assist you in navigating these roadblocks by offering spiritual guidance and protection.

They can identify potential hurdles and provide remedies to overcome them through their expertise. They may perform rituals or prescribe specific talismans to give you the strength and resilience to surmount obstacles on your journey.

Enhancing Personal Growth and Confidence

In addition to aiding you progress towards your goals, a voodoo magic specialist can contribute to your overall personal growth. Their spiritual guidance and support can help you develop self-awareness, self-confidence, and self-belief.

They may offer practices that align with your goals, such as meditation or affirmations, to promote a positive frame of mind and enhance your chances of becoming successful in all spheres of life.

Voodoo offers a unique perspective rooted in ancient spiritual traditions in a world filled with diverse approaches to achieving goals. A specialist can be a valuable ally on your journey to success, assisting you in setting clear intentions, performing rituals, harnessing energy, overcoming obstacles, and fostering personal growth. However, it's important to approach voodoo magic with respect and understanding, recognizing that it is a deeply rooted practice with cultural significance.Remember that voodoo is not rocket science that instantly brings success, so you must be patient. The practice can enhance your efforts and strengthen your resolve when used wisely and ethically. If you want to transform your life for the better, contact African Psychic Mr Abraham, the leading voodoo magic specialist in Melbourne.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm sorry to hear the things you and your family had to go through - light and blessings that your child may grow up strong, proud, and healthy. One question - was there a reason why SN didn't have folks go through becoming sou pwen first before becoming manbo/ougan? And how are things going in Jacmel rn with the different lakous and sosyetes as a result of these recent incidents?

Hi,

Thank you for your kindness.

I think there are many reasons why Sosyete Nago chooses to no longer give the blessing of a sou pwen initiation before a (potential) asogwe initiation. There were folks who were living in the US who had been made sou pwen before asogwe, but that was probably close to twenty years ago at this point.

I think the biggest reason is because Sosyete Nago does not see the value of sou pwen as a means of spiritual development and growing with a community. The focus on initiations for Sosyete Nago for folks coming from the US is to get folks in quickly and deliver what folks believe is a full, complete initiation with everything you need to go out in the world and be a houngan/manbo asogwe.

When I was preparing for my own initiation and was concerned that I would not be able to afford the asogwe initiation, I asked about sou pwen as an option and the price was quoted to me, but I was additionally told that going in for a sou pwen initiation would make my journey more complicated, as I would have to come back to Haiti again for another initiation, as if that in and of itself is a burden. It is not, and framing spiritual development as a burden is a red flag.

It was additionally communicated that sou pwen is not necessary and having folks do multiple steps initiation is a money grab, which, at this time, seems exceptionally strange to me. What is not necessary about giving people the time and space to learn and develop before placing significant ritual expectations on them? What is a money grab about staggered pricing? Spiritual work requires financial backing, but if we are casting aspersions on a traditional framework in order to get a higher ritual fee paid upfront (for asogwe), what does that mean?

In retrospect, I think a lot of what gets communicated is assuming a level of knowledge and experience seekers interested in Sosyete Nago just do not have. That's not a slam and I'm not being shady; it's just the truth. By and large, the majority of folks who come to the djevo in Sosyete Nago do not have other connections to Haitian Vodou community. Many have never spent time in other lakou or going to ceremonies with others, many/most have never been to Haiti, and most do not speak or understand Haitian Kreyòl. I'm included in that; before I went into the djevo, I had never been to ceremonies outside of Sosyete Nago, had never experienced Haiti or Haitian culture outside of the lakou, and had no grasp of Kreyòl.

So, when I was told that sou pwen would be a hinderance to me and things like me going to other ceremonies could be detrimental because I was an outsider and people would try and take advantage of me, I believed them. In truth, sou pwen would have been a huge benefit to me and to the community I was a part of.

The part that is not well-communicated is that asogwe is considered the crowning achievement for a vodouizan in an asson lineage, and a good sou pwen makes an admirable asogwe. The sou pwen is what makes a priest great; that is when houngans and manbos spend lots of time learning--literally years--all the things that make ceremonies go and what spirits wants of them. Traditionally, by the time someone goes in for an asogwe initiation--if that is deemed necessary--they know just about everything there is to know, save for specific pieces that are only revealed after the les lieux for an asogwe.

So, the idea of (essentially) a beginner going in to be lifted as if they are the ritual and religious specialists that an asogwe is supposed to be is kind of wild. Like what is the point when the responsibilities cannot be fulfilled?

The 'if that is necessary' is the really important part; not everyone needs to be an asogwe because not everyone needs to or should have the power and knowledge to give the asson. Additionally, having that power without the knowledge to balance it is an unnecessary weight to hold, like a child with an automatic weapon.

It is often presented on the internet as if a sou pwen is an incomplete priest, and that's not true. There are limitations, but they are the same limitations that thousands of Haitians have without being considered lesser or broken. Sou pwen work with the spirits closest to them and can work for clients just like asogwe can. Sou pwen can't mount a kanzo because they can't give the asson, but can do almost everything else, and especially if they have a community with asogwe who are willing to help.

Additionally, some of the most important positions in the lakou, like the laplas/protector of the lakou or the hountogi/master drummer, are a sou pwen initiation.

The time in sou pwen can also discern what should and needs to happen next for a vodouizan. Things like people not mixing well within a community or not understanding the principles of the religion can be explored in-depth before a level of ritual finality is given, without them being unable to continue their journey as a trip to Loko (part of the asogwe initiation) is something that can never be redone. These are issues that Sosyete Nago has faced, but the issue has always been projected onto individuals instead of considering a systemic issue that may require change. This change was suggested more than a few times, but never undertaken.

So...yeah. Sou pwen would be so beneficial for so many people instead of cycling folks into a position that they may be unprepared to hold in community, with that being visible to community. I understand now what that means and I understand what some criticism really means when a community is watching folks come out who have no grasp of what makes being a houngan or manbo sacred. I was in that spot, and it was a weird spot.

As far as what folks think locally in Jacmel, I wish more folks were plugged in to Haitian media. After Dana's passing, I spent a lot of time listening to what priests were saying because what unfolded seemed so horribly wrong to me. The diaspora and folks in Haiti are well connected through social media, and there were a LOT of Facebook and TikTok lives with folks from Jacmel and beyond that discussed things in ways that were publicly accessible.

The discussions were incredibly graceful, with a large focus being on 'how could this possibly have happened' with a lot of sharing on how different lakou engage before kanzo begins to make sure each person is supposed to be there at that time, that their ancestors and lwa are in agreement, that all will go well, and that the outcomes will be satisfactory. There were outlines of specific ceremonies and work shared, and there were folks who showed up asking questions, like they were never taught XYZ and what should they do to assure good outcomes, and the granmoun/elders shared and gave advice.

One of the things talked about a lot was the danger in particular that comes with a blan/outsider dying, and that is something that continues to be talked about because it's something that can cause harm to locals. Dana was from the US and she died in Haiti in a way that some folks feel is suspect, based on what was done in the immediate time after her passing. While Vodou is widely practiced in Haiti, it still has numerous detractors in Haiti and things that happen can affect folks who live there.

Other sosyete don't necessarily need to have an opinion, because Sosyete Nago has operated it's own for a long time and kind of eschewed community connections because of believing in the jealousy of local folks and ultimately an orientation towards believing there is betrayal everywhere. I think it further isolates Sosyete Nago, but that is a choice Sosyete Nago has made.

I hope this answers your questions!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mama Lola