#Vassar College Observatory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Maria Mitchell In Her Own Words

Thursday, Mch. 4 {1869}

My dear Sally,

Father seems better again today and the Doctor thinks it merely a “flurry.” But he is so feeble that any “flurry” is a serious thing. He has been up an hour today, has eaten a little dinner in bed. I slept in his room last night and shall whenever it is necessary.

MM.

William Mitchell died a little over a month later on April 19, 1869. He had lived with Maria at Vassar College from the day she began her tenure – he was the one who encouraged her to take the job – the one who told her they really wanted to hire her and that they were not just looking for her opinion of a new women’s college. He had in fact lived with her in Lynn, Massachusetts as well. The two of them left Nantucket after Lydia Coleman Mitchell’s death in 1861. Maria gave the only bedroom in the Observatory to her father for his use – feeling it was more appropriate that way and in deference to her father, her elder. This did cause some issues – Maria was forced to make-do with by using a settee in one of the sitting areas off the dome making for a cold and non-private space. She also found that if her father needed her, she could not hear him since he was on the ground floor – on the other side of the Observatory.

JNLF

#Nantucket#Maria Mitchell#Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association#Sally Mitchell Barney#William Mitchell#Vassar College#Vassar College Observatory#Lydia Coleman Mitchell#Lynn MA

0 notes

Photo

Sometimes you write a story and only afterwards get to see where you actually placed it. I’m so grateful ❤️

#ao3#eclipse#carol#vassar college#observatory#poughkeepsie#scotchplains#crossroads#train station#roadtrip

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Extraordinary Women: Books to Read

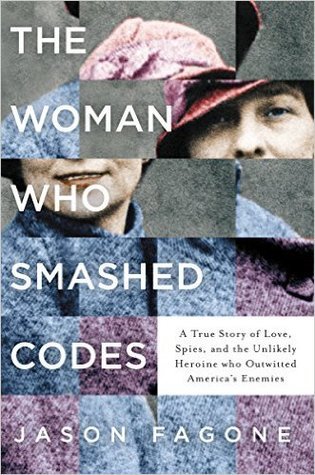

The Woman Who Smashed Codes: A True Story of Love, Spies, and the Unlikely Heroine who Outwitted America's Enemies by Jason Fagone

In 1916, at the height of World War I, brilliant Shakespeare expert Elizebeth Smith went to work for an eccentric tycoon on his estate outside Chicago. The tycoon had close ties to the U.S. government, and he soon asked Elizebeth to apply her language skills to an exciting new venture: code-breaking. There she met the man who would become her husband, groundbreaking cryptologist William Friedman. In The Woman Who Smashed Codes, Jason Fagone chronicles the life of Elizebeth Smith who played an integral role in our nation's history for forty years. After World War I, Smith used her talents to catch gangsters and smugglers during Prohibition, then accepted a covert mission to discover and expose Nazi spy rings that were spreading like wildfire across South America, advancing ever closer to the United States. As World War II raged, Elizebeth fought a highly classified battle of wits against Hitler's Reich, cracking multiple versions of the Enigma machine used by German spies. Meanwhile, inside an Army vault in Washington, William worked furiously to break Purple, the Japanese version of Enigma--and eventually succeeded, at a terrible cost to his personal life.Fagone unveils America's code-breaking history through the prism of Smith's life, bringing into focus the unforgettable events and colorful personalities that would help shape modern intelligence.

My Own Words by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Mary Hartnett (With), Wendy W. Williams (With)

The first book from Ruth Bader Ginsburg since becoming a Supreme Court Justice in 1993—a witty, engaging, serious, and playful collection of writings and speeches from the woman who has had a powerful and enduring influence on law, women’s rights, and popular culture. My Own Words offers Justice Ginsburg on wide-ranging topics, including gender equality, the workways of the Supreme Court, being Jewish, law and lawyers in opera, and the value of looking beyond US shores when interpreting the US Constitution. Throughout her life Justice Ginsburg has been (and continues to be) a prolific writer and public speaker. This book’s sampling is selected by Justice Ginsburg and her authorized biographers Mary Hartnett and Wendy W. Williams. Justice Ginsburg has written an introduction to the book, and Hartnett and Williams introduce each chapter, giving biographical context and quotes gleaned from hundreds of interviews they have conducted. This is a fascinating glimpse into the life of one of America’s most influential women.

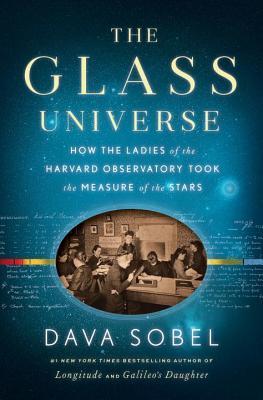

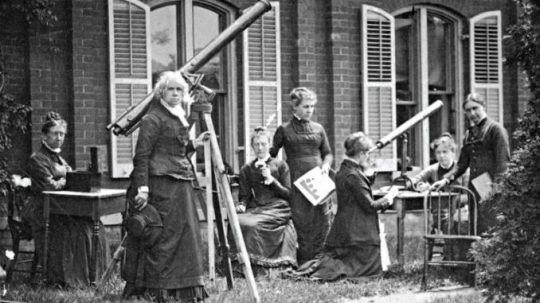

The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars by Dava Sobel

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Harvard College Observatory began employing women as calculators, or "human computers," to interpret the observations their male counterparts made via telescope each night. At the outset this group included the wives, sisters, and daughters of the resident astronomers, but soon the female corps included graduates of the new women's colleges--Vassar, Wellesley, and Smith. As photography transformed the practice of astronomy, the ladies turned from computation to studying the stars captured nightly on glass photographic plates. The "glass universe" of half a million plates that Harvard amassed over the ensuing decades--through the generous support of Mrs. Anna Palmer Draper, the widow of a pioneer in stellar photography--enabled the women to make extraordinary discoveries that attracted worldwide acclaim. They helped discern what stars were made of, divided the stars into meaningful categories for further research, and found a way to measure distances across space by starlight. Their ranks included Williamina Fleming, a Scottish woman originally hired as a maid who went on to identify ten novae and more than three hundred variable stars; Annie Jump Cannon, who designed a stellar classification system that was adopted by astronomers the world over and is still in use; and Dr. Cecilia Helena Payne, who in 1956 became the first ever woman professor of astronomy at Harvard--and Harvard's first female department chair.

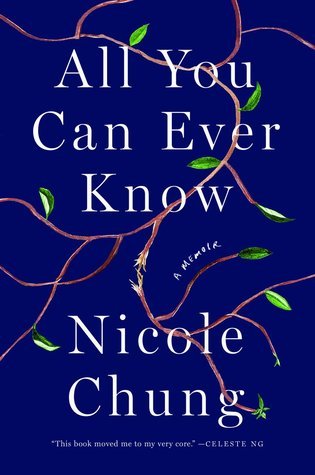

All You Can Ever Know by Nicole Chung

What does it mean to lose your roots—within your culture, within your family—and what happens when you find them? Nicole Chung was born severely premature, placed for adoption by her Korean parents, and raised by a white family in a sheltered Oregon town. From early childhood, she heard the story of her adoption as a comforting, prepackaged myth. She believed that her biological parents had made the ultimate sacrifice in the hopes of giving her a better life; that forever feeling slightly out of place was simply her fate as a transracial adoptee. But as she grew up—facing prejudice her adoptive family couldn’t see, finding her identity as an Asian American and a writer, becoming ever more curious about where she came from—she wondered if the story she’d been told was the whole truth. With warmth, candor, and startling insight, Chung tells of her search for the people who gave her up, which coincided with the birth of her own child. All You Can Ever Know is a profound, moving chronicle of surprising connections and the repercussions of unearthing painful family secrets—vital reading for anyone who has ever struggled to figure out where they belong.

#nonfiction#non-fiction#biography#autobiography#biographies#to read#womens history#tbr#booklr#history#nonfiction books#nonfiction reads#library#public library#summer reading#Resources

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Mitchell (1818-1889)

The first female astronomer in the United States, Maria Mitchell was also the first American scientist to discover a comet, which brought her international acclaim. Additionally, she was an early advocate for science and math education for girls and the first female astronomy professor.

Born on August 1, 1818 in Nantucket, Massachusetts, Maria was the third of William and Lydia Mitchell’s ten children. As Quakers, her parents advocated equal education for girls, and her father—an astronomer and teacher—contributed much to her education. Maria attended Cyrus Peirce’s School for Young Ladies, and after completing her education at age 16, opened a school training girls in math and science.

[...]

On October 1, 1847, at age 29, Maria Mitchell discovered the comet that would be named "Miss Mitchell's Comet," using a two-inch telescope. She was awarded a gold medal from King Frederick VI of Denmark and became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1848.

Later elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the American Philosophical Society, Mitchell was likely one of the first professional women employed by the US government, hired to make calculations for a project conducted by the US Coastal Survey.

After leaving the Atheneum in 1856, Mitchell traveled throughout Europe, meeting with astronomers. Over the years, she became involved in the anti-slavery movement and suffrage movements. After the Civil War, Vassar College founder Matthew Vassar recruited Mitchell to join the faculty, where she had access to a twelve-inch telescope, the third largest in the United States, and began to specialize in the surfaces of Jupiter and Saturn. She defied social conventions by having her female students come out at night for class work and celestial observations, and she brought noted feminists to her observatory to speak on political issues, among them Julia Ward Howe. Mitchell's research and that of her students was frequently published in academic journals that traditionally only featured men. Three of her female protégés were later included in the first list of Academic Men of Science in 1906.

Source: https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/maria-mitchell

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

During WWII, when Richard Feynman was recruited as one of the country’s most promising physicists to work on the Manhattan Project in a secret laboratory in Los Alamos, his young wife Arline was writing him love letters in code from her deathbed. While Arline was merely having fun with the challenge of bypassing the censors at the laboratory’s Intelligence Office, all across the country thousands of women were working as cryptographers for the government — women who would come to constitute more than half of America’s codebreaking force during the war. While Alan Turing was decrypting Nazi communication across the Atlantic, some eleven thousand women were breaking enemy code in America.

Their story, as heroic as that of the women who dressed and fought as men in the Civil War, as fascinating and untold as those of the “Harvard Computers” who revolutionized astronomy in the nineteenth century and the black women mathematicians who powered space exploration in the twentieth, is what Liza Mundy tells in Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II (public library).

A splendid writer and an impressive scholar, Mundy tracked down and interviewed more than twenty surviving “code girls,” trawled hundreds of boxes containing archival documents, and successfully petitioned for the declassification of more than a dozen oral histories. Out of these puzzle pieces she constructs a masterly portrait of the brilliant, unheralded women — women with names like Blanche and Edith and Dot — who were recruited into lives they never could have imagined, lives believed to have saved incalculable other lives by bringing the war to a sooner end.

Driven partly by patriotism, but mostly by pure love of that singular intersection of mathematics and language where cryptography lives, these “high grade” young women, as the military recruiters called them, came from all over the country and had only one essential thing in common — their answers to two seemingly strange questions. Mundy traces the inception of this female codebreaking force:

A handful of letters materialized in college mailboxes as early as November 1941. Ann White, a senior at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, received hers on a fall afternoon not long after leaving an exiled poet’s lecture on Spanish romanticism.

The letter was waiting when she returned to her dormitory for lunch. Opening it, she was astonished to see that it had been sent by Helen Dodson, a professor in Wellesley’s Astronomy Department. Miss Dodson was inviting her to a private interview in the observatory. Ann, a German major, had the sinking feeling she might be required to take an astronomy course in order to graduate. But a few days later, when Ann made her way along Wellesley’s Meadow Path and entered the observatory, a low domed building secluded on a hill far from the center of campus, she found that Helen Dodson had only two questions to ask her.

Did Ann White like crossword puzzles, and was she engaged to be married?

Elizabeth Colby, a Wellesley math major, received the same unexpected summons. So did Nan Westcott, a botany major; Edith Uhe (psychology); Gloria Bosetti (Italian); Blanche DePuy (Spanish); Bea Norton (history); and Ann White’s good friend Louise Wilde, an English major. In all, more than twenty Wellesley seniors received a secret invitation and gave the same replies. Yes, they liked crossword puzzles, and no, they were not on the brink of marriage.

Letters and clandestine questioning sessions spread across other campuses, particularly those known for strong scientific curricula — from Vassar, where astronomer Maria Mitchell paved the way for American women in science, to Mount Holyoke, the “castle of science” where Emily Dickinson composed her botanical herbarium. The young women who answered the odd questions correctly were summoned to secret meetings, where they learned they were being invited to work for the U.S. Navy as “cryptanalysts.” They were to take a training in codebreaking and, if they completed it successfully, would take jobs with the Navy after graduation, as civilians. They could tell no one about the appointment — not their parents, not their girlfriends, not their fiancés.

First, they had to solve a series of problem sets, which would be graded in Washington to determine if they made the cut to the next stage. Mundy writes:

And so the young women did their strange new homework. They learned which letters of the English language occur with the greatest frequency; which letters often travel together in pairs, like s and t; which travel in triplets, like est and ing and ive, or in packs of four, like tion. They studied terms like “route transposition” and “cipher alphabets” and “polyalphabetic substitution cipher.” They mastered the Vigenère square, a method of disguising letters using a tabular method dating back to the Renaissance. They learned about things called the Playfair and Wheatstone ciphers. They pulled strips of paper through holes cut in cardboard. They strung quilts across their rooms so that roommates who had not been invited to take the secret course could not see what they were up to. They hid homework under desk blotters. They did not use the term “code breaking” outside the confines of the weekly meetings, not even to friends taking the same course.

These young women’s acumen, and their willingness to accept the cryptic invitations, would become America’s secret weapon in assembling a formidable wartime codebreaking operation in record time. They would also furnish a different model of genius — one more akin to the relational genius that makes a forest successful. Mundy writes:

Code breaking is far from a solitary endeavor, and in many ways it’s the opposite of genius. Or, rather: Genius itself is often a collective phenomenon. Success in code breaking depends on flashes of inspiration, yes, but it also depends on the careful maintaining of files, so that a coded message that has just arrived can be compared to a similar message that came in six months ago. Code breaking during World War II was a gigantic team effort. The war’s cryptanalytic achievements were what Frank Raven, a renowned naval code breaker from Yale who supervised a team of women, called “crew jobs.” These units were like giant brains; the people working in them were a living, breathing, shared memory. Codes are broken not by solitary individuals but by groups of people trading pieces of things they have learned and noticed and collected, little glittering bits of numbers and other useful items they have stored up in their heads like magpies, things they remember while looking over one another’s shoulders, pointing out patterns that turn out to be the key that unlocks the code.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Reposted from @quotabelle “The more we see, the more we are capable of seeing.” ~ Maria Mitchell . . This once amateur stargazer would study the skies from the island of Nantucket, off the coast of Massachusetts. Her love for astronomy took her - and us, far. Maria went on to discover a comet, become an admired expert, and Vassar College’s first professor, where she would host dome parties in the campus observatory to introduce young women to the wonders of space. This quote is a favorite, as is her remarkable story. . #BeautifullySaid by #mariamitchell #astronomer #womeninstem #stargazer #wcw #bravely #gritandgrace #quotabelle - #regrann https://www.instagram.com/p/B9EvojXlibT/?igshid=do9xgx1db9j9

#beautifullysaid#mariamitchell#astronomer#womeninstem#stargazer#wcw#bravely#gritandgrace#quotabelle#regrann

1 note

·

View note

Text

Meet Wilhelmina Fleming: The Trailblazing Astronomer Who Changed the Game!

Have you heard of Wilhelmina Fleming?

This pioneering astronomer made significant contributions to the field of astronomy, and her work paved the way for future generations of female scientists.

Here's a closer look at her remarkable career and achievements.

Wilhelmina Fleming was born in Dundee, Scotland in 1857 and grew up with a strong interest in science and mathematics. She went on to study astronomy at Vassar College, where she excelled in her coursework and quickly caught the attention of prominent astronomers.

After graduation, Fleming worked as a "computer" at the Harvard College Observatory, where she was responsible for calculating and analyzing astronomical observations made by others. Despite her impressive skills and contributions, she was not paid a salary and was not recognized as a professional astronomer.

Despite these challenges, Fleming continued to work in astronomy and eventually became an assistant astronomer at the Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C. In this role, she made significant contributions to the field, including She helped develop a common designation system for stars and cataloged more than ten thousand stars, 59 gaseous nebulae, more than 310 variable stars and 10 nova as well as many other astronomical phenomena.

Fleming is noted for her discovery of the Horsehead Nebula 1888.

Fleming's work was widely recognized and respected, and she became the first female member of the American Astronomical Society. She also became the first woman to be elected to the Royal Astronomical Society in Britain.

Wilhelmina Fleming's achievements broke down barriers for women in astronomy and paved the way for future generations of female scientists. Her work demonstrated that women could excel in this field and make important contributions to our understanding of the universe.

Today, Fleming is remembered as a trailblazer and a role model for women in science. Her legacy continues to inspire and encourage women to pursue careers in astronomy and other STEM fields.

In conclusion, Wilhelmina Fleming was a remarkable astronomer who made significant contributions to the field and broke down barriers for women in science. The next time you look up at the night sky, remember her legacy and the ongoing efforts to promote diversity and equality in STEM fields.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Maria Mitchell

*Herminia Borchard Dassel

Maria Mitchell (/məˈraɪə/; August 1, 1818 – June 28, 1889) was an American astronomer, librarian, naturalist, and educator. In 1847, she discovered a comet named 1847 VI (modern designation C/1847 T1) that was later known as "Miss Mitchell's Comet" in her honor. She won a gold medal prize for her discovery, which was presented to her by King Christian VIII of Denmark in 1848. Mitchell was the first internationally known woman to work as both a professional astronomer and a professor of astronomy after accepting a position at Vassar College in 1865. She was also the first woman elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

At 10:50 pm on the night of October 1, 1847, Mitchell discovered Comet 1847 VI (modern designation C/1847 T1) using a Dollond refracting telescope with three inches of aperture and forty-six inch focal length. She had noticed the unknown object flying through the sky in an area where she previously had not noticed any other activity and believed it to be a comet. The comet later became known as "Miss Mitchell's Comet". She published a notice of her discovery in Silliman's Journal in January 1848 under her father's name. The following month, she submitted her calculation of the comet's orbit, ensuring her claim as the original discoverer. Mitchell was celebrated at the Seneca Falls Convention for the discovery and calculation later that year.

On October 6, 1848, Mitchell was awarded a gold medal prize for her discovery by King Christian VIII of Denmark. This award had been previously established by King Frederick VI of Denmark to honor the "first discoverer" of each new telescopic comet, a comet too faint to be seen with the naked eye. A question of credit temporarily arose because Francesco de Vico had independently discovered the same comet two days after Mitchell but reported it to European authorities first. The question was resolved in Mitchell's favor and she was awarded the prize. Her medal was inscribed with line 257 of Book I of Virgil's Georgics: "Non Frustra Signorum Obitus Speculamur et Ortus" (English: Not in vain do we watch the setting and the rising [of the stars]). The only previous women to discover a comet were the astronomers Caroline Herschel and Maria Margarethe Kirch. Though the award was sent via letter in 1848, Mitchell did not physically receive the award in Nantucket until March 1849. She became the first American to receive this medal and the first woman to receive an award in astronomy.

Though Mitchell herself did not have a college education, she was appointed professor of astronomy at Vassar College by its founder, Matthew Vassar, in 1865 and became the first female professor of astronomy. Mitchell was the first person appointed to the faculty and was also named director of the Vassar College Observatory, a position she held for more than two decades. Mitchell also edited the astronomical column of Scientific American during her professorship. Thanks in part to Mitchell's guidance, Vassar College enrolled more students in mathematics and astronomy than Harvard University from 1865 to 1888. In 1869, Mitchell joined Mary Somerville and Elizabeth Cabot Agassiz in becoming some of the first women elected to the American Philosophical Society. Hanover College, Columbia University, and Rutgers Female College granted Mitchell honorary degrees.

Mitchell maintained many of her unconventional teaching methods in her classes: she reported neither grades nor absences; she advocated for small classes and individualized attention; and she incorporated technology and mathematics in her lessons. Though her students' career options were limited, she never doubted the importance of their study of astronomy. "I cannot expect to make astronomers," she said to her students, "but I do expect that you will invigorate your minds by the effort at healthy modes of thinking. When we are chafed and fretted by small cares, a look at the stars will show us the littleness of our own interests".

Mitchell's own research interests were quite varied. She took pictures of planets, such as Jupiter and Saturn, as well as their moons, and she studied nebulae, double stars, and solar eclipses. Mitchell then developed theories around her observations, such as the revolution of one star around another in double star formations and the influence of distance and chemical composition in star color variation. Mitchell often involved her students with her astronomical observations in both the field and the Vassar College Observatory. Though she began recording sunspots by eye in 1868, she and her students began photographing them daily in 1873. These were the first regular photographs of the sun, and they allowed her to explore the hypothesis that sunspots were cavities rather than clouds on the surface of the sun. For the total solar eclipse of July 29, 1878Mitchell and five assistants traveled with a 4-inch telescope to Denver for observations. Her efforts contributed to the success of Vassar's science and astronomy graduates, as twenty-five of her students would go on to be featured in Who's Who in America.

In 1841, she attended the anti-slavery convention in Nantucket where Frederick Douglass made his first speech, and she also became involved in the anti-slavery movement by refusing to wear clothes made of Southern cotton. She later became involved in a number of social issues as a professor, particularly those pertaining to women's suffrage and education. She befriended various suffragists including Elizabeth Cady Stanton. After returning from a trip to Europe in 1873, Mitchell joined the national women's movement and helped found the Association for the Advancement of Women (AAW), a group dedicated to educational reform and the promotion of women in higher education. Mitchell addressed the Association's First Women's Congress in a speech titled The Higher Education of Women in which she described the work of English women working for access to higher education at Girton College, Cambridge. Mitchell advocated for women working part-time while acquiring their education to not only ease the wages off of men paying for their education, but also to empower more women to be in the workforce. She also called attention to the place for women in science and mathematics and encouraged others to support women's colleges and women's campaigns to serve on local school boards. Mitchell served as the second president of the AAW in 1875 and 1876 before stepping down to form and head a special Committee on Science to analyze and promote women's progress in the field.

0 notes

Photo

Antonia Maury (1866-1952) was an American astronomer. She is best known for publishing an early catalog of stellar spectra.

She graduated from Vassar College in 1887 with honors in physics, astronomy, and philosophy. She then went on to work for the Harvard College Observatory as a human computer. She was awarded the Annie Jump Cannon Award in Astronomy in 1943.

#born on this day#amazing women#antonia maury#Astronomy#women in astronomy#science#women in science#women in stem#feminist#feminism

153 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy 200th Birthday, Maria Mitchell!

Maria Mitchell, the first professional American woman astronomer, was born on this day in 1818 in Nantucket, Massachusetts. Mitchell was also the first woman member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, two years after its formation, in 1850.

Mitchell was born to Quaker parents who believed in the education of all of their ten children, regardless of gender. Mitchell received a formal education, as well as learning from her father, who was a schoolteacher, banker, and astronomer. He also helped to maintain chronometers, a timepiece sailors used to measure longitude based on time and celestial navigation, for the local whaling fleet. His daughter would assist him in doing astronomical observations and later was trusted to complete them on her own.

In 1835, at the age of 17, Mitchell founded her own elementary school, which was open to girls regardless of race. The following year, Mitchell left the school to take a job at the Nantucket Athaneum, then a private, but affordable, library. She remained at the Athaneum until 1856.

On Oct. 1, 1847, Mitchell was using a two-inch telescope on a Nantucket rooftop when she noticed a blurry object that did not appear on her star charts. This turned out to be a comet, which became known as "Miss Mitchell's Comet" and later C/1847 T1. She became the third woman, after two 18th-century German astronomers—Caroline Herschel and Maria Margarethe Kirch—to discover a comet. King Frederick VI of Denmark, who had offered a prize for the discovery of new comets, awarded Mitchell a medal. She also became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences because of her discovery.

In 1865, Mitchell was the first person invited to join the faculty of the newly established Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. She accepted the founder's invitation, in part because it came with the promise of an observatory outfitted with a 12-inch telescope, then the second largest in the country. She went on to become a beloved professor, teaching more than 20 years and nurturing her students' abilities as researchers in their own right. Her students did independent, original research and even engaged in field work with Mitchell's professional peers during the solar eclipses of 1869 and 1878. Mitchell, who was involved in suffrage organizations and who served as the second president of the American Association of Women, also organized discussions and lectures for her students about women's rights and politics.

Learn more.

#maria mitchell#Astronomy#comet#aaas#women in stem#vassar college#american academy of arts and sciences#science history#women in science

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Mitchell In Her Own Words

Observatory – Dec. 5, 1873

President Raymond,

A plaster cast of the head of Mary Somerville by the sculptor Moe Donald, has been received as a donation to the Observatory. It is not only a beautiful ornament in itself, but it has the additional value of being the gift of another remarkable woman Frances Power Cobbe of London. I have supposed that some other notice should be taken of it, beside the unofficial letter which I shall write to Miss Cobbe.

Maria Mitchell

Mary Somerville, as I have mentioned before, was one of Maria Mitchell’s heroes. On her first trip to Europe in the 1850s, Maria met Somerville. While she made comments regarding this in her journal, I can only image how she truly felt in her presence – something words on paper might not convey. This plaster cast remained in a position of prominence in the observatory during the remainder of Maria’s time at Vassar.

She met Frances Power Cobbe, the donor of this bust, on her second trip to Europe in the summer of 1873. Maria had a letter to deliver from Julia Ward Howe and also wished to leave Power Cobbe with a pamphlet regarding Vassar College – fundraising I am sure! She was worried she would not be at home but she was and Power Cobbe knew who Maria was straight away – she had been told Maria was in London! After some initial misinformation, Maria came to know that Power Cobbe was indeed a powerful force among the Suffragettes.

JNLF

#Nantucket#Maria Mitchell#Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association#Mary Somerville#Frances Power Cobbe#Julia Ward Howe#Vassar College#Vassar College Observatory#Moe Donald#suffragettes#President John Raymond Vassar College

0 notes

Photo

Inspirierende Frauen der Geschichte

Maria Mitchell

US-amerikanische Astronomin und Vorkämpferin für die Frauenrechte.

Kometensuchen ist unter Wissenschaftlern des 19. Jahrhunderts eine Art Sport. Für die Entdeckung teleskopischer Kometen, also solcher, die mit bloßem Auge nicht zu erkennen sind, werden im 19. Jahrhundert Preise vergeben, weltweit. Dass eine junge Frau aus Nantucket einen Kometen findet, ist eine Sensation: nämlich Maria Mitchell (geboren am 1.August 1818) Der dänische König verleiht Maria daraufhin eine Goldmedaille im Wert von 20 Dukaten. Die American Academy of Arts and Sciences nimmt sie als Mitglied auf – als erste Frau. Touristen reisen an, um Maria Mitchell, der berühmten Astronomin, die Hand zu schütteln.

Mitchell ist damals 29 Jahre alt. Sie ist gebildet, war aber nie an einer Universität. Frauen dürfen damals nicht studieren. Zu den Observatorien der berühmten Universitäten und Gesellschaften, dort, wo die modernsten Teleskope stehen, haben Frauen keinen Zutritt. Doch Maria Mitchell lernt schon als Kind von ihrem Vater, wie Sextanten funktionieren, wie man mithilfe der Sterne die Uhrzeit und die Position berechnet.

Als 1865 das Vassar College eröffnet, eine der ersten amerikanischen Frauen-Unis, erhält die Astronomin aus Nantucket eine Anstellung. Sie, die nie in einem Hörsaal saß, wird mit 47 Jahren die erste Astronomieprofessorin Amerikas. Sie bekommt ein eigenes Observatorium, das ihr Arbeitszimmer, Klassenraum und Schlafgemach wird.

Zurückkehrt nach Nordamerika, wird sie zur Ikone der amerikanischen Frauenbewegung. 1873 gründet sie die American Association for the Advancement of Women, zwei Jahre später wird sie deren Präsidentin. "Ich glaube an die Frauen, mehr noch als an die Astronomie", schreibt sie später in ihr Tagebuch. Mitchell hält Vorträge, in denen sie die Gleichberechtigung von Frauen fordert. Aber auf die eine Frage, die sie ihr ganzes Leben quält, findet sie keine Antwort: Wie kann man Frau sein und erfolgreiche Wissenschaftlerin? Sie wird berühmt, und bleibt doch bis ins hohe Alter schüchtern. Sie wird zur Stimme der Frauenbewegung, aber die meiste Zeit verbringt sie stumm unter der Kuppel der Sternwarte am Vassar College. Sie wohnt in einem Haus mit ihrem Vater, bis er stirbt. Sie heiratet nie.

Auf Nantucket steht heute eine Sternwarte, das Maria Mitchell Observatory. Ein Stipendium für junge Forscherinnen trägt ihren Namen, ein Mondkrater, ein Kriegsschiff der U. S. Navy und der Zug, mit dem Studenten des Vassar College nach New York fahren.

0 notes

Photo

Women in Science: Mary Watson Whitney and Irène Joliot-Curie

From Clevermanka’s This Week in Feminist History:

On September 11 in 1847…

… Mary Watson Whitney, an American astronomer, was born in Waltham, Massachusetts. Due to her father’s business success, she was able to attend school in Waltham, then was privately tutored for one year until entering Vassar College in 1865. She earned her degree three years later, despite facing several family tragedies during that time, including her father’s death and the loss of her brother at sea. In 1872, she earned her master’s degree from Vassar as well, after attending several courses at Harvard. (At the time, Harvard didn’t admit women, though they could attend courses as guests. So very gracious of them.) Mary worked as a teacher for a few years, after which she took a job at Vassar as an assistant to astronomer Maria Mitchell. When Maria retired in 1888, Mary became a professor of astronomy and the director of the observatory. In her time supervising at Vassar Observatory, she and others under her published over 102 articles. Mary herself focused on researching comets, variable stars, double stars, and asteroids. She was a charter member of the Astronomical and Astrophysical Society, and also a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Mary lived until January of 1921 when she died of pneumonia at the age of 73.

On September 12th in 1897…

… French scientist and Nobel Prize winner Irène Joliot-Curie was born in Paris, France. Irène, the daughter of Marie and Pierre Curie, began her education where she was ten years old. After her mother became aware of her talent in math, she decided to ensure her daughter had a more challenging education. Marie joined with a number of other French scholars, including Paul Langevin (French physicist) to form a collective of academics who participated in educating each other’s children. The Cooperative taught their children science and mathematics and also subjects such a sculpture and the Chinese language. After two years, Irène attended the Collège Sévigné in Paris, before moving to Sorbonne Faculty of Science. World War I interrupted her education, at least in the university sense. She assisted her mother in running field hospitals instead, and assisted with the early X-ray technology her parents’ research helped develop. (The radiation they were both exposed to here and later on led not only to Marie’s eventual death but Irène’s as well.) After the war, Irène finished her education at her parents Radium Institute. By 1925, she had a Doctorate of Science. Around that same time, she met Frédéric Joliot, whom she later married. The pair decided to work together, much like Irène’s parents. Together they identified the positron and the neutron. Unfortunately, they didn’t properly understand the results, and the discoveries were later claimed by other scientists. Their most well-known discovery was in 1934 when Irène and her husband figured out how to transform elements. They turned boron into radioactive nitrogen, magnesium into silicon, and aluminum into phosphorus. Their discovery led to the quick creation of radioactive materials, and they received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935. Unfortunately, Irène developed leukemia a short while later. Doctors relieved her condition for some time, during which she continued to work. She survived until 1956 when she died of leukemia at the age of 58. Her daughter Hélène Langevin-Joliot is a nuclear physicist, and her son Pierre Joliot is a biochemist.

More on the original post: X. She posts a new "This Week in Feminist History” piece every Monday!

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Antonia Maury was an American astronomer known for publishing an important early catalog of stellar spectra. She was born in March 21, 1866 in a family of portuguese descendants. In 1887 she graduated with honors in Vassar College, where she studied physics, and attended lectures by Maria Mitchell, also a famous astronomer.

She started working in the Harvard Observatory College, where she had to process astronomic data and was part of the famous Harvard Computers. It was then when she started calculating stellar spectra and compiling them in a new catalogue, that was published in 1897. She left Harvard college because the director Edward Charles Pickering didn’t approve her catalogue, in spite of its good scientific reviews, but returned in 1908. After her retirement, her interests were focused on nature and conservation.

26 notes

·

View notes

Link

by odeon

After an excruciatingly long day of emotional turmoil, Carol Aird revisits her old alma mater, the Vassar College in Poughkeepsie. The impulsive decision to do so leads to an unexpected meeting with a young female student, Therese Belivet, who shares an apartment with a group of friends off campus.

An emotional night sparks an unlikely relationship neither one of them saw coming.

Words: 2783, Chapters: 1/?, Language: English

Fandoms: Carol (2015), The Price of Salt - Patricia Highsmith

Rating: Not Rated

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings

Categories: F/F

Characters: Carol Aird, Therese Belivet, Abby Gerhard, Genevieve Cantrell, Harge Aird, Dannie McElroy, Phil McElroy, Richard Semco

Relationships: Carol Aird/Therese Belivet

Additional Tags: Alternate Universe - Modern Setting, Romance, Angst, Fluff, Lesbian Sex, New York, Observatory, Celestial Objects, Friendship, OTP Feels, Loss, Hope, Love, Happy Ending

February 06, 2017 at 08:47AM via AO3 works tagged 'Carol (2015)'

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Last fall, when John DiGravio arrived as a freshman at Williams College — a private, liberal arts institution in the Berkshires — the conservative from Central Texas expected to be in the political minority.

He did not expect to be ridiculed. But in the winter, when he returned from an anti-abortion rally with the school’s Catholic student group in Washington, the college’s usually harmonious Instagram account, which featured a photo of the trip, received numerous enraged comments.

Some posters booed the group. One called it “embarrassing.” Another suggested the students should “start a better club.”

At first DiGravio was taken aback. Then he took his outsider status as a calling. A few months earlier he had started a small, conservative club. He decided to make it bigger. He invited a speaker to give an evening talk on “What It Means to Be a Conservative.” Dozens of students showed up.

“I think I really hit a chord,” he said.

These days, elite students like DiGravio, who can financially and/or academically choose from an array of colleges, are often obsessed with “finding the right fit.” Surveys like ones conducted by EAB, an education consulting firm in Washington, routinely indicate that for this group, “fitting in” is one of the top factors when deciding where to go to school.

But some students, like DiGravio, 19, are discovering the pros and cons of being an outsider.

Today, top public universities are accepting out-of-state students in record numbers. Lesser-known schools sometimes referred to as “hidden gems” have made big efforts to lure high-performing students from far away. Some college counselors say they are encouraging students to explore universities in Canada, England and even Abu Dhabi.

But many say they don’t recommend that for every high school senior.

Nikki Bruno, a New Jersey-based admissions coach, says students have to have an “adventurous spirit,” and seem particularly confident before she suggests a college environment that may feel a bit out of their comfort zone.

Yodit Gebretsadik, 20, is that kind of student. At first, being at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, which has one of the most moneyed student bodies in the country, was isolating for Gebretsadik, a mechanical engineering major from Jacksonville, Florida, who got there by way of a competitive scholarship program.

Gebretsadik, whose father manages a convenience store, said many students arrived with coveted internships their parents had helped them get and had high school engineering experiences inside and out of the classroom that she didn’t know existed.

She was cloaked in doubt during her first semester. But she said an active campus program designed to support first-generation college students helped her connect with professors and other students like her.

Soon she began to excel in her science and math classes, in many cases outperforming the peers who had arrived with more initial exposure. “It was a huge confidence booster,” she said.

Sociologists who study outsiders say it’s no surprise. They say people who can find even a small support group can become more fully engaged with who they are, and what their core values are, by being in a place that feels foreign.

Pietro Geraci, 22, a libertarian who graduated in May from Vassar College, a small liberals arts school in Poughkeepsie, New York, with a degree in astronomy, says being a political outsider requires some courage.

During Geraci’s freshman year, he joined a small campus chapter of the Young Americans for Liberty, a Washington-based libertarian youth group, and reconnected it with the national headquarters.

Making friends became challenging. “People here don’t like it when you go around saying taxation is theft,” he said. Most of his friends are liberal, he said, and some came to the group’s meetings and were eager to engage in “fruitful conversation.” And Geraci, who speaks with gusto about his ideology, did not let the political tension deter him from touring Cuba with the school’s choir and spending time in the school’s observatory.

Tiago Rachelson, 19, is white, and he attends Morehouse College, a historically black school in Atlanta. Rachelson, a sociology major, said he enrolled because the mission of the school “called to him.” His decision, though, caused waves among some students who were interviewed for a documentary released this summer by VICE.

One young man, commenting in the documentary about the central role historically black colleges and universities have played for black Americans, said the idea that a lot of white students would inundate his school made him feel disrespected.

Rachelson acknowledged those feelings, but he said that navigating the experience had been “transformational.”

And he is not alone in feeling that the outsider role can have a profound impact on one’s sense of self.

Amir Goldberg, an associate professor of organizational behavior at Stanford University Graduate School of Business, who studies outsiders inside the workplace, says being an outsider can cause culture shock. But that doesn’t have to be a bad thing.

“If you have support, that shock can be translated into an advantage,” he said.

That was the case for Jonah Shainberg, a fencer from Rye, New York, who is Jewish. When he was accepted to Notre Dame, a football-heavy Catholic university in Indiana, his mother balked at the idea.

“I’m not sending my Jewish son to Notre Dame,” Shainberg recalled her saying. He was also skeptical.

But once he was there, Shainberg, who graduated this year with a bachelor’s degree in business administration, discovered something about himself he had not totally understood before: His faith was central to his identity.

“I think Notre Dame made me more Jewish,” he said.

For Elyse Hutcheson, 21, the opposite was true. Her time at Hillsdale College, a Christian college in Hillsdale, Michigan, helped her get in touch with her views on reproductive rights, immigration and social welfare programs.

When she arrived, she said, “I knew I wasn’t a conservative, but I didn’t know I was a liberal.” By her junior year, she had re-energized a defunct club for campus Democrats and realized she was agnostic.

She graduated this year with a degree in psychology and art and took a job as a research assistant at Brown University, a liberal-leaning college in Providence, Rhode Island.

While Hutcheson admits it’s a relief to now be around like-minded thinkers, she says fitting in comes with its own pitfalls.

“I don’t want to become complacent because the ideas I have aren’t being questioned anymore,” she said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Kyle Spencer © 2018 The New York Times

via NewsSplashy - Latest Nigerian News,Ghana News ,News,Entertainment,Hot Posts,sports In a Splash.

0 notes