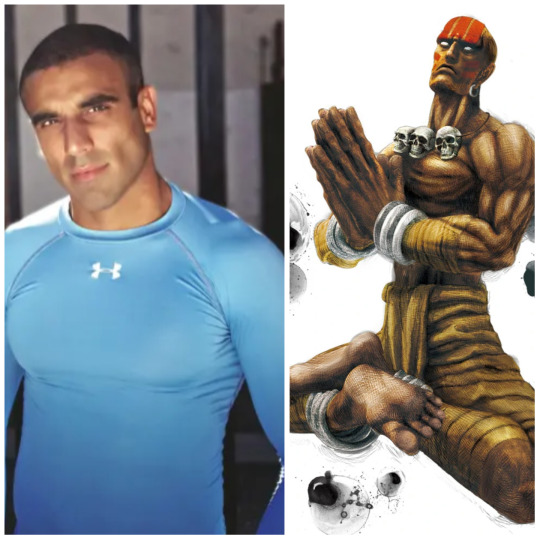

#Umar Khan

Text

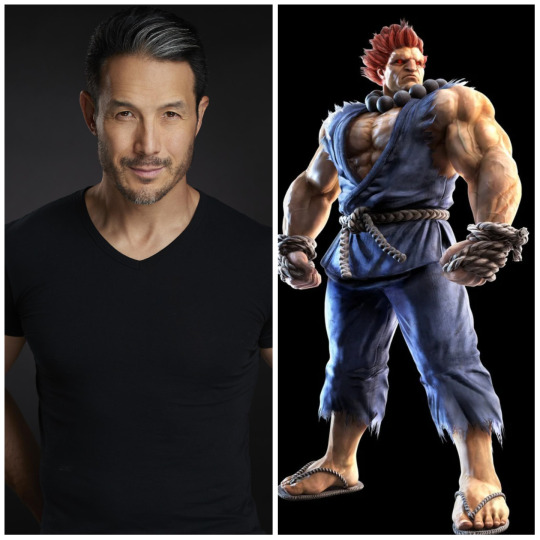

For the the Street Fighter Reboot movie or TV series, I nominated Umar Khan as Dhalsim, Yamamotoyama Ryūta or Takato Yonemoto as Edmond Honda (E. Honda), Martin Sensmeier as Thunderhawk (T. Hawk), Israel Adesanya as Donald Jackson (Dee Jay), Fabrício Werdum, Tanoai Reed, Lateef Crowder or Lyoto Machida as Blanka, Abbas Alizadeh, Andy Le or Aarif Rahman as Fei-Long, Momona Tamada or Ella Jay Basco as Sakura Kasugano and Darren E. Scott as Akuma.

#Street Fighter#Umar Khan#Dhalsim#Yamamotoyama Ryūta#Takato Yonemoto#E. Honda#Martin Sensmeier#T. Hawk#Israel Adesanya#Dee Jay#Fabrício Werdum#Tanoai Reed#Lateef Crowder#Lyoto Machida#Blanka#Abbas Alizadeh#Andy Le#Aarif Rahman#Fei-Long#Darren E. Scott#Akuma#Street Fighter Reboot Movie#Street Fighter TV Series#fancast#Sakura Kasugano#Momona Tamada#Ella Jay Basco

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

اَللّٰھُمَّ صَلِّ عَلٰی مُحَمَّدٍ وَعَلٰی آلِ مُحَمَّدٍ کَماصَلَّيتَ عَلٰی اِبْراھِيمَ وَعَلٰی آلِ اِبْراھِيمَ اِنَّكَ حَمِيدُ مَّجِيدُُ اَللَّھُمَّ بَارِك عَلٰی مُحَمَّدٍوَّعَلٰی آلِ مُحَمَّدٍ کَمَا بَارکتَ عَلٰی اِبراھِيمَ وَعَلٰی آلِ اِبراھيمَ اِنَّكَ حَمِيدُ مَّجِيدُ

www.facebook.com/share/r/K1sV39ZtvjadMGUk/

﴿ 1﴾ اِنَّاۤ اَعۡطَيۡنٰكَ الۡكَوۡثَرَؕ ترجمہ : (اے محمدﷺ) ہم نے تم کو کوثر عطا فرمائی ہے Lo! We have given thee Abundance; ﴿2﴾ فَصَلِّ لِرَبِّكَ وَانۡحَرۡؕ ترجمہ : تو اپنے پروردگار کے لیے نماز پڑھا کرو اور قربانی دیا کرو So pray unto thy Lord, and sacrifice ﴿3﴾ اِنَّ شَانِئَكَ هُوَ الۡاَبۡتَرُ ترجمہ : کچھ شک نہیں کہ تمہارا دشمن ہی بےاولاد رہے…

#AAFU#Afroz#ALLAH BAKHSHAY MY NOBLE DR.AMANULLAH KHAN AND MY NOBLE BEGUM SAHIBA ALLAH UMAR DARAZ KARAY BEGUM DR.AMANULLAH KHAN GRANDDAUGHTER OF NAWAB SI#Allah Nawaz Castle of Nawab of Dera Ismail Khan#https://pin.it/xmlw2XO#https://wowmaryamgull-blog.tumblr.com/post/143684486096/when-creating-a-new-character#nawab ikramullah khan inventor#Nawabdera#Novels by Nawabdera Aafiya Mariyum Moosa KALEEMULLAH khan#The Nawab of Dera

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

﷽

This post has been removed from my Facebook feed which demands explanation from meta.com and its owner flip.it/tElSLz

﷽

Because some of the deadliest crimes of Netanyahu were exposed to the world which is not only blind but deaf and dumb too

Dua of Prophet Moses (A.S) رَبِّ اشْرَحْ لِي صَدْرِي وَيَسِّرْ لِي أَمْرِي وَاحْلُلْ عُقْدَةً مِّن لِّسَانِي يَفْقَهُوا قَوْلِي O my Lord! Open for me my…

View On WordPress

#nawabdera= نو ا ب ا کرام اللہ خان#ALLAH BAKHSHAY MY NOBLE DR.AMANULLAH KHAN AND MY NOBLE BEGUM SAHIBA ALLAH UMAR DARAZ KARAY BEGUM DR.AMANULLAH KHAN GRANDDAUGHTER OF NAWAB SI# ﷺ#HISTORY#HONESTY#moosakaleemullahkham#NAWAB IKRAMULLAH KHAN#nawabdera.wordpress.com#SAFETY by نو ا ب ا کرام اللہ خان

1 note

·

View note

Text

کاش چیف جسٹس ایسا نہ کرتے

کاش چیف جسٹس عمر عطا بندیال فل کورٹ بنا دیتے۔ کاش چیف جسٹس اُسی تین رُکنی بنچ کی سربراہی کرتے ہوئے پنجاب میں الیکشن کروانے جیسا اہم سیاسی فیصلہ نہ کرتے جس کے بارے میں سب کو پہلے سے معلوم تھا کہ یہ بنچ کیا فیصلہ کرسکتا ہے۔ کاش چیف جسٹس تمام سیاسی جماعتوں کا مؤقف سن کر اپنا فیصلہ سناتے اور بنچ پر اعتراض کرنے والوں کی بات سن لیتے۔ کاش چیف جسٹس اپنے ساتھی ججز کے اعتراضات اور اُن کے فیصلوں کو بھی اہمیت دیتے۔ کاش چیف جسٹس یہ فیصلہ نہ کرتے، ایک ایسا فیصلہ نہ کرتے جسے ناصرف تاریخ کے متنازعہ فیصلوں میں شامل کیا جائے گا بلکہ اس کے سبب موجودہ سیاسی انتشار اور تقسیم مزید بڑھنے کا اندیشہ ہے۔ مجھے ذاتی طور پر بنچ پر بھی اعتراض تھا اور فیصلہ بھی میری نظر میں انصاف کے تقاضے پورے نہیں کرتا لیکن اس کے باوجود جب فیصلہ آ گیا تو اس کو حکومت کیسے مسترد کر سکتی ہے؟ یہ میری سمجھ سے بالاتر ہے۔ حکومت کے پاس اگر کوئی قانونی اور آئینی راستہ موجودہ ہے تو وہ ضرور اسے اپنے حق میں استعمال کرے لیکن یہ کہنا کہ سپریم کورٹ کا فیصلہ ہی نہیں مانتے اور اس پر عمل بھی نہیں کریں گے تو یہ بھی انتشار کی ایک نئی شکل ہو گی۔

نہ کابینہ سپریم کورٹ کے فیصلے کو مسترد کر سکتی ہے نہ ہی حکمراں اتحاد کے رہنمائوں کے لئے یہ مناسب ہے کہ وہ یہ کہیں کہ اس فیصلے پر عمل نہیں کیا جائے گا چاہے اس کے جو مرضی نتائج ہوں۔ حکومت کے پاس اس فیصلے کے خلاف نظرثانی کی درخواست کرنے کا حق موجود ہے۔ یہ نظرثانی کی اپیل ایک ماہ کے اندر سپریم کورٹ میں پیش کی جا سکتی ہے اور اس کے لئے حکومت حال ہی میں پارلیمنٹ کے ذریعے پاس ہونے والے چیف جسٹس کے اختیارات کے متعلق بل کے قانون بننے کا انتظار بھی کر سکتی ہے۔ کہا جارہا ہے کہ شاید صدر پاکستان اس بل پر دستخط نہیں کریں گے جس کے باعث حکومت کو اس بل کو قانون کی شکل دینے میں پندرہ دن بھی لگ سکتے ہیں۔ جب یہ بل قانون بن جائے گا تو اس فیصلے کے خلاف سپریم کورٹ میں اپیل کی جا سکتی ہے اور نئے بننے والے قانون کے مطابق چیف جسٹس اور دو سینئیر ترین ججوں کی کمیٹی یہ فیصلہ کرے گی کہ اس اپیل کو سننے کے لئے کن کن ججز پر مشتمل بنچ بنایا جائے۔

تحریک انصاف کے سینیٹر اور سپریم کورٹ کے وکیل علی ظفر نے اس قانون کی تجویز پر سینیٹ میں بحث کے دوران حکومت کو یہ وارننگ دی تھی کہ عدلیہ اس قانون کو بننے کے 10/20 دن کے اندر ہی کالعدم قرار دے دے گی۔ اگر ایسا ہوا تو معاملہ مزید گمبھیر ہو جائے گا اور سپریم کورٹ اور پارلیمنٹ آمنے سامنے ہوں گے۔ حکومت کی طرف سے فیصلہ دینے والے تین رُکنی بنچ میں شامل ججوں کے خلاف سپریم جوڈیشل کونسل میں ریفرنس دائر کرنے کی باتیں بھی کی جا رہی ہیں۔ میری دانست میں فیصلوں کی بنیاد پر ججوں کے خلاف ریفرنس دائر کرنے کی کوئی حیثیت نہیں ہوتی۔ صرف اُسی صورت میں ایسا ریفرنس قابلِ سماعت ہو سکتا ہے جب شکایت کنندہ کے پاس کوئی ٹھوس ثبوت موجود ہو کہ اس فیصلے کے پیچھے کوئی سازش تھی یا کوئی غیر قانونی اقدام اس کی وجہ تھا۔ صرف یہ کہنا کہ یہ تین ججز تو عمران خان کے حق میں اور ن لیگ اور پی ڈی ایم کے خلاف فیصلے دیتے ہیں، کوئی حیثیت نہیں رکھتا۔

چیف جسٹس اگر انصاف ہوتا ہوا نظر آنے کے اصول کی پاسداری کے لئے فل کورٹ بنا دیتے تو ہمیں اس موجودہ صورت حال کا سامنا نہ کرنا پڑتا جس میں اس بات کو یقینی طور پر کہا ہی نہیں جا سکتا تھا کہ پنجاب میں الیکشن 14 مئی کو ہی ہوں گے اس طرح حکومت اور پی ڈی ایم کو چاہئے کہ جذباتی انداز میں سپریم کورٹ کے فیصلے کو مسترد کرنے کی بجائے قانونی اور آئینی راستہ اختیار کرے۔ حکومت اور حکمراں جم��عتیں ہی اگر سپریم کورٹ کے فیصلے کو نہیں مانیں گی تو پھر عام لوگ عدالتوں کے فیصلوں کو کیوں تسلیم کریں گے۔ یہاں اب بھی سیاسی حل کی بات کی جا سکتی ہے۔ عمران خان نے اپنے تازہ بیان میں کہا ہے کہ وہ اکتوبر میں الیکشن کے لئے انتظار کر سکتے ہیں اگر حکومت کے پاس کوئی ٹھوس تجویز ہو۔ کتنا اچھا ہو کہ حکمراں جماعتیں اور تحریک انصاف پورے پاکستان میں اکتوبر میں ایک ساتھ الیکشن کروانے کے نکتے پر اتفاق کر لیں تو اس سے ہم بہت سی خرابیوں سے بچ جائیں گے۔

انصار عباسی

بشکریہ روزنامہ جنگ

0 notes

Text

The new army chief should first investigate what happened in the last 8 months

The new army chief should first investigate what happened in the last 8 months

The real problem was not the no-confidence motion, but giving the impression that Imran Khan failed, and the nation is still suffering from the consequences of the action taken. Secretary General PTI Asad Umar’s speech.

Secretary General of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf Asad Umar has said that the new army chief should first investigate what happened in the last 8 months. The nation is also…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Tu Mera Banja Lyrics - Vivek Hariharan | Madhubanti Bagchi

Tu Mera Banja Lyrics – Vivek Hariharan | Madhubanti Bagchi

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#wasim akram#wahab riaz#umar gul#Pakistan cricketers#pakistan#mushtaq ahmed#Imran Khan#cricket ireland

0 notes

Text

Some of the names that had previously been mentioned here in this channel. The least we can do is to atleast mention the ones we know..

Our scholars from Bangladesh who are behind bars, among whom are:

Sheikh Jashim Uddin Rahmani

Sheikh Hārūn Izhar

Sheikh Ali Hassan Osama

Sheikh Mahmud Hasan Gunvi

Sheikh Abu Taha with his two assistants Amir Uddin Foyez and Abdul Muhit

Our Scholars, students of knowledge and preachers who have been imprisoned and tortured by Tawagheet Regimes, among whom are:

Shaykh Nāṣir alFahd

Shaykh Sulaymān Nasir al-Alwan

Shaykh Waleed As-Sinani

Shaykh Khalid Rashid

Shaykh Ali al-Khudayr

Shaykh al-Khalidi

Shaykh Saud al-Obaid al-Qahtani

Shaykh Ahmad al-Asir

Shaykh Faisal

Shaykh Benbrika

Shaykh Abu Baraa- As-Sayf

Shaykh Abu Umar

Abu Hamza al-Misri

Abu Hamza (ATP)

Abu Imran (Belgium)

Abu Ilyas (Holland)

Abu Abdurrahman (Denmark)

Our scholars who had been k***d in the way of Allah after imprisonment:

Shaykh Musa al-Qarni

Shaykh Faris az-Zahrani

Shaykh Hamad al-Humeidi

Shaykh Abdul Aziz al-Tiwayli

Others:

Afiya

Hayla al-Qusayr

Umm A

Umm Abdul Qayoom

Ukht M and her daughters S and R (UK)

Sabir Miah (UK)

Ali Hussain (UK)

Safiyya (UK)

Safiya Yassin (USA)

Our young Deutsch

sis & student of Shaykh AMJ

Muhammad Abu Bakr (Minshawary)

Ali Bhola

Abul wali AbuKhadir Muse (The Smiling Somali)

Iqbal Khan (India)

Abu Syahla

Muhammad

Abu Yousuf

Brother R

Abu I and Abu N

Ukht S & Ukht H from India

Umm Hud

Sister A

Sister B & siblings & their mother

Umm Mariyah

Brothers Jahanzaib, Nabeel, Abdullah Basit

Sister S (Bangladesh)

Our dear brother Muhammad Azharuddin

Brother 'Talib Exposed'

Brother Abu Luqman (Anjem)

Brother Khaled

Abu Fazul

Abu Umar (Pakistan)

Iqbal

Ibn Tsar (Chechen)

Hadi Nabi

Abu Ibrahim

Ari and Alan

Last edited on 25 Sep 23

Shared

اللهم فك قيد اسرانا و اسرى المسلمين

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Parveen Shakir say:-

"Hum toh samjhe the ki ek zakam hai bhar jaega ..

Kya kabar thi ki rag-e- jaan mein utar jaega.."

When Shafin khan also said >>

"Hame to yakeen the tu loat kar aayega ek Deen..

Kya kabar thi ki sari Umar ka intezar bekaar jaega.."

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s the difference between Shi’a and Sunni? I’ve tried to ask around but most people I know are Sunni so they are a bit biased. Also I hope you have a nice day op :)

The Shi'as hold that Ali (a), the cousin of Prophet Muhammed (pbuh&hf) was the successor to the caliphate, and the first Imam among the Shi'as. Sunnis believe that Abu Bakr, followed by Umar and Uthman and then Ali (a), were the caliphs. Shi'as believe that Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman were usurpers, and caused widespread corruption of the Muslim nation following the Prophet's death.

Shi'as were initially a political party, but developed into a theological school. For Twelvers and Ismailiyyas, the believe in a concept called Ismah, which is the concept of infallibility extended to the Imams, the Prophets, including the Biblical ones, the Holy ladies and the angels. Twelvers believe in the Fourteen infallibles, while the Ismailiyyas believe extend it to the long chain of Imams. Due to their infallibility, the have esoteric and exoteric knowledge of the Qur'an, thus their opinions are considered absolute, thus our corpus of Hadiths are different from that of Sunnis. The Twelvers have twelve Imams with the final being Imam is in occultation, while the current Imam of the Ismailiyyas is the Aga Khan IV. Sunnis do not believe in the concept of Ismah or Imamate, however, many Sunnis believe that it was only extended to the Prophet Muhammed (pbuh&hf). Due to their partisanship and revolt against the various caliphates and sultanates, Shi'as have been persecuted and marginalized.

Shi'as pray differently, combine their prayers as a form of convenience, perform ablution differently, can't eat shellfish, have a concept called temporary marriage. Shi'as are well-known to perform the act of self-flagellation to lament the martyrdom of the various Imams, especially Imam Hussain (a) and his mother Fatimah (sa). This can range from hitting your chest with your hands, hitting your back with chains, hitting your head with a dull sword or cutting your back with knives (don't google). Shi'as emphasise the concept of intercession, shrine visitations to seek blessings from God by the intercession of the Imams. Shi'as emphasise the concept of tabarrah, which means dissociating from the enemies of the Prophet Muhammed and his household (pbuh&hf), whether they be Muslim or non-Muslim. Shi'as hold that various companions of the Prophet were indeed corrupt and wicked, such as Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, Ayesha, Hafsa, Khalid ibn Walid, Muawiyah, and etc.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Narrated Ibn Umar [رضي الله عنه]: The Prophet [ﷺ] said:

❝One of the sayings of An-Nubuwwa [the Prophethood]

which the people have got is,

'If you do not feel ashamed, then do whatever you like.'❞

[Sahīh Al-Bukhārī, (4/3484) | Translated By Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan]

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Were the Mongols really that stinky?

Me trying to summarise/simplify notes I've found on the Internet. But also this is me trying to defend Mongolia ‼️😔✋🐴

(Editing this to re-work the Yassa and Mamluk part as the source I have used to explain it was most likely biased. )

The hygiene practices of the Mongols have been documented by the Mongols and foreigners alike. Apparently, according to some historical resources, the Mongols smelled so bad that you could actually smell them incoming, and that during battle, their stench actually helped them. This seems like a ridiculous exaggeration to be honest, and probably was written by people who were subjected by the Mongols and therefore were very butthurt. All soldiers on a campaign, no matter where they're from, can smell pretty bad.

It is said that the Mongols would not bathe, in fear of angering the water dragons which controlled the waters. This was recorded by the 15th century Mamluk Historian al-Maqrizi. It is true that the Mongols were a shamanistic people, however the mention of dragons is peculiar. The appearance of dragons in original Turco-mongol mythology is almost absent, and dragons are more used in Chinese and tibetan mythology.

In addition, do we really know if the whole "not bathing in running water" thing was truly what was happening with the Mongols, or was it another mistranslation after centuries and centuries of copying things and translating things? François Pétis de la Croix, a French historian of the 18th century, had access to Al-Maqrizi's original work. François came to a different conclusion to his findings - that bathing in running water was banned only during thunderstorms. Both because it was dangerous and also to show respect to Tengri.

Then, in the 20th century, George Vernadsky, who was a Russian-American historian, came to agree with François Pétis de la Croix's conclusion. He agreed that this law was not as restrictive as we may have originally believed. Further, let's remember that they were "banned" from using "running water". Surely that means they could have collected water in jugs and used that or something?

There is also issues with Al-Maqrizi's original source - he is not really regarded as a reliable one. His information on the Yassa was apparently given to him by a man called Abu-Hashim, who claimed that he saw the whole of the Yassa in the libraries of Baghdad during his political exile.

Abu-Hashim is an obscure historical figure and little is known about him and his works, if he even had any.

What Al-Maqrizi thought to be the Yassa was actually just a small list of punishment for offences from the Mongol Criminal law.

Al-Maqrizi also fails to admit that he borrowed pretty heavily from the scholar Ibn Fadl Allah al-Umar in his works on the Mongols. Ibn Fadl Allah al-Umar based his works off of Ata-Malik Juvayni, who was a respected official in the Ilkhanate. Further, Ata-Malik Juvayni wrote the book "History of the world conquerer". This was probably the most unbiased account of the Mongol conquests of Chinggis Khan at the time.

Considering this, you may think. Oh! So it was kind of based off of a reputable source. Must be legit then. But no, Al-Maqrizi, as we can further see in this post, omitted many things from the works he was influenced by, because he had a pretty sour bias against the Mongols.

Juvayni, in his work, records how bathing was banned during certain times of the day during spring and summer months, during which thunderstorms were common. Al-Maqrizi makes no mention of this.

It could be argued that Juvayni himself was biased in trying to make the Mongols look good. Some argue that this "bathing in midday was banned" fiasco was written in by Juvayni to demonstrate the mercy of Chagatai Khan when he pardoned a poor Muslim who was caught bathing in midday. But honestly that seems like a weird thing for Juvayni to lie about, even if it was to make Chagatai look good, so I agree with the original conclusion.

Let's also not forget that Al-Maqrizi lived during the time of the Egyptian Mamluks in 1364-1442. He definitely had a sour opinion of the Mongols, especially the Golden Horde and Ilkhanate, who were the products of the brutal conquest of Muslim-majority states.

It is rumoured that the some of the Yassa codes may have been used to administer affairs in with the Mamluks, however accounts of this are greatly exaggerated. However the Muslim Mamluks certainly knew of the Yassa and were very cautious and critical of it.

Al-Maqrizi, during this time, was very adamant and vocal about the Yassa being satanic, hmm I wonder why (hint: he had a sour opinion of the Mongols).

Considering all of this, can we truly believe what Al-Maqrizi said about the Mongols hygiene practices? Even other historians at the time had this strong bias against the Mongols, and we should really be taking what they say with a pinch of salt (probably like. 100kg of salt tbh)

In addition, I've seen a Mongolian answer this question online, and they said that in those times, Mongolias used ointments of animal origin to rub dirt off of the skin - similar to the inuits. Let's also remember that "running" water was not allowed to be used, and not allowed during thunderstorms. Running water was more often seen in nature settings for the Mongols in those times, and the fact that you weren't allowed to use running water during thunderstorms? Yeah honestly to me that just seems like respecting nature/Tengri and avoiding danger if anything.

So basically. They probably didn't smell that much worse than anyone else during the time!

DEFENDING MONGOLIA‼️ LEAVE HIM ALONE

#hetalia#aph mongolia#hws mongolia#Hetalia mongolia#Historical hetalia#hetalia world twinkle#hetalia world stars#hetalia world series#History#mongol empire#Mongolian empire#mongolian history#East Asian history#Central Asian history#Asia#Central Asia#East Asia#Asian history#Mongolia

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

PALESTINE 🇵🇸 TO BE FREED FROM THTHE WRONGDOERS By the Leave of Allah

flipboard.com/@nawabdera1/palestine-🇵🇸-to-be-freed-from-ththe-wrongdoers-l36lfb7kz

View On WordPress

#Afroz#ALLAH BAKHSHAY MY NOBLE DR.AMANULLAH KHAN AND MY NOBLE BEGUM SAHIBA ALLAH UMAR DARAZ KARAY BEGUM DR.AMANULLAH KHAN GRANDDAUGHTER OF NAWAB SI#ALLAH NAWAZ CASTLE#Allah Nawaz Castle of Nawab of Dera Ismail Khan#ALLAH NAWAZ CASTLE OF THE NAWAB OF DERA ISMAIL KHAN#https://pin.it/xmlw2XO#nawab ikramullah khan inventor#Nawabdera#Novels by Nawabdera Aafiya Mariyum Moosa KALEEMULLAH khan#The Nawab of Dera#ا للّٰہ نو از کیسل آف نواب آف ڈیرہ اسماعیل خان Allah Nawaz Castle of the Nawab of Dera Ismail Khan

1 note

·

View note

Text

INSHA ALLAH Safety for the Linemen in WAPDA And globally

What are you passionate about?

INSHA ALLAH focusing upon inventions on Safety in Electrical Engineering

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم السلام علیکم IN SHA ALLAH I am pleased to thank you by the MERCY OF ALLAH Regards

Nawab Ikramullah Khan

لا اله الا الله محمد رسول الله

View On WordPress

#nawabdera= نو ا ب ا کرام اللہ خان#AAFU#ALLAH BAKHSHAY MY NOBLE DR.AMANULLAH KHAN AND MY NOBLE BEGUM SAHIBA ALLAH UMAR DARAZ KARAY BEGUM DR.AMANULLAH KHAN GRANDDAUGHTER OF NAWAB SI#Allah Nawaz Castle of Nawab of Dera Ismail Khan#dailyprompt#dailyprompt-1967#DR.AMNULLAHKHAN#Gomal university#HISTORY#Nawab Allah Nawaz Khan#NAWAB IKRAMULLAH KHAN#Novels by Nawabdera Aafiya Mariyum Moosa KALEEMULLAH khan#patents#WAPDA

1 note

·

View note

Text

Narrated 'Abdullāh bin 'Umar رضي الله عنهما :

Allaah's Messenger ﷺ said, "The Salāt (prayer) in congregation is twenty-seven times superior in degrees to the Salāt offered by a person alone."

{Sahīh al-Bukhāri. Hadeeth No.645. Trans by: Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan rahimahullah}

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

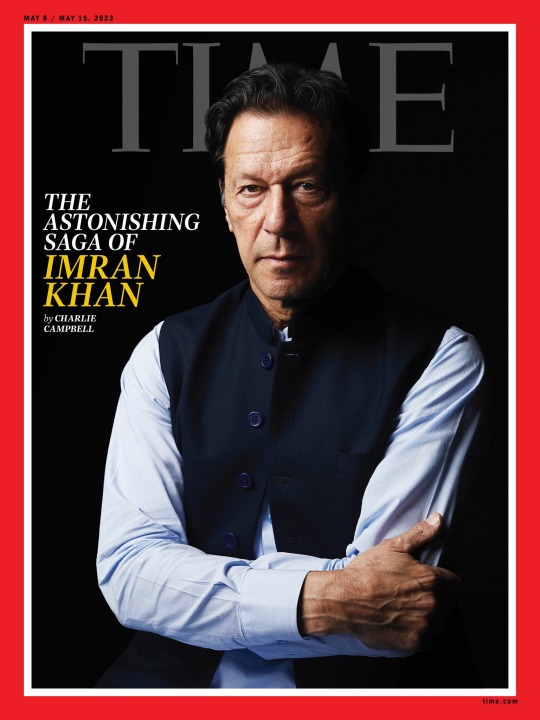

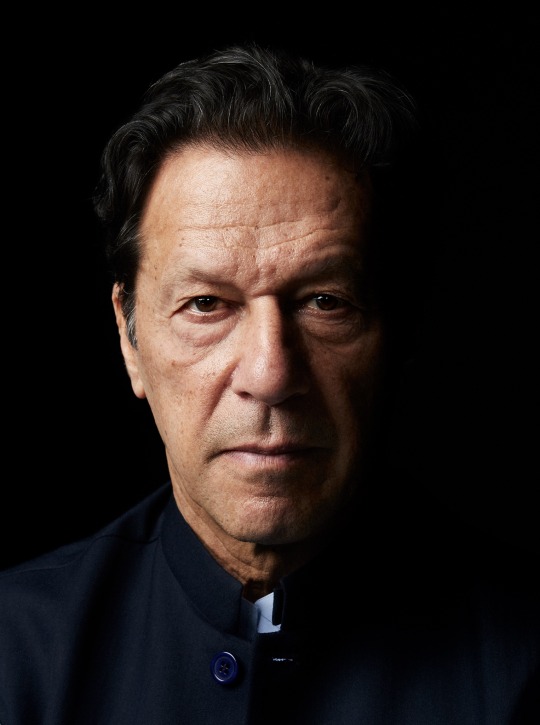

Exclusive: Imran Khan on His Plan to Return to Power

— By Charlie Campbell | April 3, 2023 | Time Magazine

Former Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan sits for a portrait in his Lahore residence on March 28. Next to Khan are tear gas canisters he says were thrown at his house. Umar Nadeem for Time Magazine

Political leaders often boast of inner steel. Imran Khan can point to three bullets dug out of his right leg. It was in November that a lone gunman opened fire on Khan during a rally, wounding the 70-year-old as well as several supporters, one fatally. “One bullet damaged a nerve so my foot is still recovering,” says the former Pakistani Prime Minister and onetime cricket icon. “I have a problem walking for too long.”

If the wound has slowed Khan, he doesn’t show it in a late-March Zoom interview. There is the same bushy mane, the easy laugh, prayer beads wrapped nonchalantly around his left wrist. But in the five years since our last conversation, something has changed. Power—or perhaps its forfeiture—has left its imprint. Following his ouster in a parliamentary no-confidence vote in April 2022, Khan has mobilized his diehard support base in a “jihad,” as he puts it, to demand snap elections, claiming he was unfairly toppled by a U.S.-sponsored plot. (The State Department has denied the allegations.)

The actual intrigue is purely Pakistani. Khan lost the backing of the country’s all-powerful military after he refused to endorse its choice to lead Pakistan’s intelligence services, known as ISI, because of his close relationship with the incumbent. When Khan belatedly greenlighted the new chief, the opposition sensed weakness and pounced with the no-confidence vote. Khan then took his outrage to the streets, with rallies crisscrossing the nation for months.

Photograph by Umar Nadeem for Time Magazine

“Imran Khan can communicate with all strata of society on their level,” says Shaheena Bhatti, 63, a professor of literature in Rawalpindi. “The other politicians are … not going to do anything for the country because they’re only in it for themselves.”

The November attack on Khan’s life only intensified the burning sense of injustice in members of his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party, or PTI, who have since clashed with police in escalating street battles involving slingshots and tear gas. Although an avowed religious fanatic was arrested for the shooting, Khan continues to accuse an assortment of rival politicians of pulling the strings: incumbent Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif—brother of Khan’s longtime nemesis, former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif—as well as Interior Minister Rana Sanaullah and Major General Faisal Naseer. (All have denied the accusation.)

In addition to bullets, Khan has also been hit by charges—143 over the past 11 months, by his count, including corruption, sedition, blasphemy, and terrorism—which he claims have been concocted in an attempt to disqualify him from politics. After Sharif’s cabinet declared on March 20 that the PTI was “a gang of militants” whose “enmity against the state” could not be tolerated, police arrested hundreds of Khan supporters in raids.

“Either Imran Khan exists or we do,” Interior Minister Sanaullah said on March 26.

Pakistan sometimes seems to reside on a precipice. Its current political instability comes amid devastating floods, runaway inflation, and resurgent cross-border terrorist attacks from neighboring Afghanistan that together threaten the fabric of the nation of 230 million. It’s a country where rape and corruption are rife, and the economy hinges on unlocking a stalled IMF bailout, Pakistan’s 22nd since independence in 1947. Inflation soared in March to 47% year-over-year; the prices of staples such as onions rose by 228%, wheat by 120%, and cooking gas by 108%. Over the same period, the rupee has plummeted by 54%.

“Ten years ago, I earned 10,000 rupees a month [$100] and I wasn’t distressed,” says Muhammad Ghazanfer, a groundsman and gardener in Rawalpindi. “With this present wave of inflation, even though I now earn 25,000 [$90 today] I can’t make ends meet.” The world’s fifth most populous country has only $4.6 billion in foreign reserves—$20 per citizen. “If they default, and they can’t get oil, companies go bust, and people don’t have jobs, you would say this is a country ripe for a Bolshevik revolution,” says Cameron Munter, a former U.S. ambassador to Pakistan.

Police fired teargas to disperse the supporters of the former Prime Minister as they tried to arrest Khan in Lahore, Pakistan, on March 14. Hundreds of Tehrik-e-Insaf supporters clashed with riot police as they reached Khan's residence. Rahat Dar—EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

“Our economy has gone into a tailspin,” says Khan. “We now have the worst economic indicators in our history.” The situation threatens to send the nuclear-armed country deeper into China’s orbit. Yet sympathy is slim in a West put off by Khan’s years of anti-American bluster and cozying up to autocrats and extremists, including the Taliban. He calls autocratic Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan “my brother” and visited Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow on the eve of the Ukraine invasion, remarking on “so much excitement.” Khan can both repeatedly declare Osama bin Laden a “martyr” and praise Beijing’s confinement of China’s Uighur Muslim minority. He has obsessed on Joe Biden’s failure to call him after entering the White House. “He’s someone that is imbued with this incredibly strong sense of grievance,” says Michael Kugelman, the deputy director of the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Yet Khan can legitimately claim to have democracy on his side, with poll numbers suggesting he is a shoo-in to return to power if the elections he demands happen. “His popularity has skyrocketed,” says Samina Yasmeen, director of the Centre for Muslim States and Societies at the University of Western Australia. “No matter what he says, even if it’s irrational, the reality is that people are angry and taken by his message.”

“Imran Khan is the best bet we have right now,” says Osama Rehman, 50, a telecommunications engineer in Islamabad. “If [he] is arrested or disqualified, people will come out onto the street.”

The state appears to flirt with the idea. Police raids on Khan’s home in the Punjab province capital of Lahore in early March left him choking on tear gas, he says, as supporters brandishing sticks battled police in riot gear before makeshift barricades of sandbags and iron rods. “This sort of crackdown has never taken place in Pakistan,” says Khan. “I don’t know even if it was as bad under martial law.”

After Khan left his compound to appear in court on March 18, traveling in an armored SUV strewn with flower petals and flanked by bodyguards, the police swooped in while his wife was home, he says, beating up servants and hauling the family cook off to jail. He claims another assassination attempt awaited inside the Islamabad Judicial Complex, which was “taken over by the intelligence agencies and paramilitary.”

Police arrested 61 supporters of former Prime Minister Imran Khan during a search operation near Khan’s residence, in Lahore, Pakistan, on March 18, 2023. K.M. Chaudary—AP

The confrontation could remain in the streets indefinitely. Prime Minister Sharif has rejected Khan’s demand for a snap election, saying polls would be held as scheduled in the fall. But “every narrative is being built up [for the government] to justify postponing the elections,” says Yasmeen. On March 22, Pakistan’s Election Commission delayed local balloting in Punjab, the country’s most populous province, from April 30 until Oct. 8.

“Political stability in Pakistan comes through elections,” Khan points out. “That is the starting point for economic recovery.” From the U.S. perspective, he may be far from the ideal choice to helm an impoverished, insurgency-racked Islamic state. But is he the only person that can hold the country together?

“Never has one man scared the establishment … as much as right now,” says Khan. “They worry about how to keep me out; the people how to get me back in.”

It’s indicative of Pakistan’s malaise that its most popular politician in decades sits barricaded at home. But the nation has always been beyond comparison—a wedge of South Asia that begins in the shimmering Arabian Gulf and ascends to its Himalayan heights. It’s the world’s largest Islamic state, though governed for half its history by men in olive-green uniforms, who continue to act as ultimate arbiters of power.

The only boy of five children, Khan was born Oct. 5, 1952 to an affluent Pashtun family in Lahore. He studied politics, philosophy, and economics at Oxford University, and it was in the U.K. that he first played cricket for Pakistan, at age 18. Britain’s sodden terrain also provided the backdrop to his political awakening.

“When I arrived in England our country had been ruled by a military dictator for 10 years; the powerful had one law, the others were basically not free human beings,” he says. “Rule of law actually liberates human beings, liberates potential. This was what I discovered.”

Khan in his Lahore residence on March 28. Umar Nadeem for Time Magazine

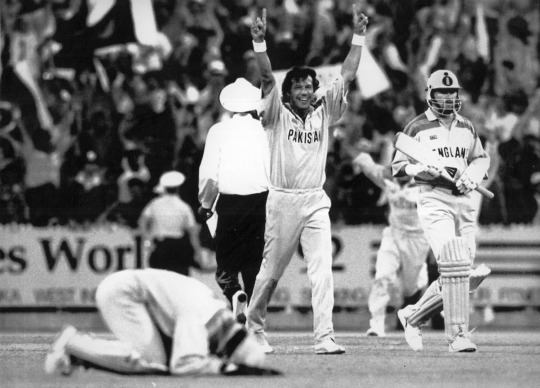

On the cricket pitch, Khan was a talisman who knitted together mercurial talents and journeymen into a cohesive whole, a team that overcame extraordinary odds to famously lift the Cricket World Cup in 1992. There were glimpses of these qualities when Khan rose to become Prime Minister: running on an anti-graft ticket, he fused a disparate band of students and workers, Islamic hard-liners, and the nation’s powerful military to derail the Sharif political juggernaut. His crowning achievement remains the Shaukat Khanum Cancer Hospital in Lahore, which he opened in 1994 in memory of his mother, who succumbed to the disease. It is the largest cancer hospital serving Pakistan’s impoverished, boosting Khan’s administrative credentials.

Khan spent 22 years in the political wilderness before his 2018 election triumph. But once in power, the self-styled bold reformer turned unnervingly divisive. Opposition is easier than government, and Khan found himself bereft of ideas and besieged by unsavory partners, even kowtowing to the now-banned far-right party Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan despite its support for the extrajudicial killing of alleged blasphemers. There were some successes: Pakistan received praise for its handling of the pandemic, with deaths per capita just a third that of neighboring India. His “Ten Billion Tree Tsunami” reforestation drive was popular, as was the 2019 return of international test cricket, the most prestigious form of the game, following a terrorist attack on the Sri Lankan team and a decade-long hiatus.

Khan’s private life has rarely been out of the headlines. His first wife was British journalist and society heiress Jemima Khan, née Goldsmith, a close friend of Diana, Princess of Wales. She converted to Islam for their wedding, though the pair divorced in 2004 after nine years of marriage, and her family’s Jewish heritage was political dynamite. (The couple’s two sons live in London.) Khan’s second marriage to British-Pakistani journalist Reham Khan lasted nine months. According to a 1997 California court ruling, Khan also has one child, a daughter, born out of wedlock, and he’s struggled to quash gossip of several more. In 2018, six months before he took office, he married his current wife, Bushra Bibi Khan, a religious conservative who is believed to be the only Pakistan First Lady to wear the full-face niqab shawl in public.

Khan, left, lifts elder son Suleman while his ex-wife Jemima carries younger son Qasim during a march towards the U.N. offices in Islamabad in 1999. The Khans led some 100 demonstrators in an anti-Russian rally protesting against attacks in Chechnya. Reuters

It all fed Khan’s legend: the debonair playboy who grew devout; the privileged son who rails against the corrupt; the humanist who stands with the bloodthirsty. His youth was spent carousing with supermodels in London’s trendiest nightspots. But his politics has hardened as his handsome features have lined and leathered. He provoked outrage when in August 2021 he said the Taliban had “broken the shackles of slavery” by taking back power (he insists to TIME he was “taken out of context”) and has made various comments criticized as misogynistic. When asked about the drivers of sexual violence in Pakistan, he said, “If a woman is wearing very few clothes, it will have an impact on the men, unless they’re robots.” Khan has refused to condemn Putin’s invasion, insisting, like China, on remaining “neutral” and deflecting uncomfortable questions onto supposed double standards regarding India’s inroads into disputed Kashmir. “Morality in foreign policy is reserved for powerful countries,” he says with a shrug.

Khan in the 1992 Cricket World Cup. Pakistan won under Khan's captaincy this year. Fairfax Media

At the same time, Khan’s ideological flexibility has not stretched to compromises with opponents. He claims it was the military’s unwillingness to go after Pakistan’s influential “two families”—those of Sharif and the Bhutto clan of former Prime Ministers Zulfikar and Benazir—for alleged corruption that caused his relationship with the generals to fray. “If the ruling elite plunders your country and siphons off money, and you cannot hold them accountable, then that means there is no rule of law,” he says.

Yet analysts say that it was Khan’s relentless taunting of the U.S. that torpedoed his relationship with the military, which remains much more interested in retaining good relations with Washington. To journalists and supporters, he has accused the U.S. of imposing a “master-slave” relationship on Pakistan and of using it like “tissue paper.” To TIME, he insists that “criticizing U.S. foreign policy does not make you anti-American.” Still, by 2022, the generals no longer had his back. The common perception among Pakistan watchers is that Khan’s fleeting political success was owed to a Faustian pact with the nation’s military and extremist groups that shepherded his election victory and he is now reaping the whirlwind.

Cricket captain turned politician Imran Khan shakes hands with supporters during a rally in October 2002 in Shadi Khal, Pakistan. Paula Bronstein—Getty Images

He appears to relish in the perceived injustice, the walls closing in. On March 25, Khan addressed thousands of supporters in central Lahore from a bulletproof box above a green-and-red flag with the initials of his PTI emblazoned on a cricket bat—once Khan’s weapon of choice, though now he wields words with similar potency.

“I know you have decided you wouldn’t allow Imran Khan back in power,” he said. “That’s fine with me. But do you have a plan or know how to get the country out of the current crisis?”

If Pakistan’s economic woes are reaching a new nadir, the trajectory was established during Khan’s term. A revolving door of Finance Ministers was compounded by bowing to hardliners. (After appointing renowned Princeton economist Atif Mian as an adviser, Khan fired him just days later owing to a backlash from Islamists because Mian is an Ahmadi, a sect of Islam they consider heretics.) In 2018, Khan pledged not to follow previous administrations’ “begging bowl” tactics of foreign borrowing, in order to end Pakistan’s cycle of debt. But less than a year later, he struck a deal with the IMF to cut social and development spending while raising taxes in exchange for a $6 billion loan. Mismanagement exacerbated global headwinds from the pandemic and soaring oil prices.

Meanwhile, little was done to address Pakistan’s fundamental structural issues: few people pay tax, least of all the feudal landowners who control traditional low-added-value industries like sugar farms, textile mills, and agricultural interests while wielding huge political-patronage networks stemming from their workers’ votes. In 2021, only 2.5 million Pakistanis filed tax returns—less than 1% of the adult population. “People don’t pay tax, especially the rich elite,” says Khan. “They just siphon out money and launder it abroad.”

Instead, Pakistan has relied on foreign money to balance a budget and provide government services. The U.S. funneled nearly $78.3 billion to Pakistan from 1948 to 2016. But in 2018, President Trump ended the $300 million security assistance that the U.S. provided annually. Now Pakistan must shop around for new benefactors—chiefly Saudi Arabia, Russia, and China. When Khan visited Putin last February, it was to arrange cheap oil and wheat imports and discuss the $2.5 billion Pakistan Stream gas pipeline, which Moscow wants to build between Karachi and Kasur. More recently, China has stepped in. In early March, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China approved a $1.3 billion loan rollover—a fiscal bandaid for a gaping wound.

Khan in his Lahore residence on March 28. Umar Nadeem for Time Magazine

But if Khan recognized the problem, he did little to solve it. After his election in 2018, he was in an uncommonly strong position with the backing of the military and progressives, as well as the tolerance of the Islamists. Now, with all the bad blood and open warfare among these factions, even if he claws his way back, “he’ll be in a weaker position to actually effect any reforms,” says Munter, the former U.S. ambassador, “if he had any reforms to begin with.”

When asked for his step-by-step plan to get Pakistan back on track, Khan is light on details. After elections, he says that a “completely new social contract” is required to enshrine power in political institutions, rather than the military. If the army chief “didn’t think corruption was that big a deal, then nothing happened,” Khan complains. “I was helpless.” But the path to this utopia remains murky. Asked how he plans to turn his much trumpeted Islamic Welfare State ideal into a reality, Khan talks about Medina under the Prophet and the social conscience of Northern Europeans. “Scandinavia is probably far closer to the Islamic ideal than any of the Muslim countries.”

But the military looms large in Pakistan partly because national security is a perennial issue. Many assumed that the newly returned Taliban would stamp out all cross-border attacks from Afghanistan. But Pakistan recorded the second largest increase in terrorism-related deaths worldwide in 2022, up 120% year-over-year. “It was Khan who was pushing for talks with [the Taliban] at all costs,” says Kugelman, of the Woodrow Wilson Center. “That embrace is now experiencing significant levels of blowback.”

That Pakistan is moving away from the U.S. and closer to Russia and China is a moot point; the bigger question is who actually wins from embracing Pakistan. The $65 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor was supposed to be the crown jewel in President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative, linking China via roads, rail and pipeline to the Arabian Sea. But Gwadar Port is rusting and suicide bombers are taking aim at buses filled with Chinese workers. Loans are more regularly defaulted than paid. Today, even Iran looks like a more stable partner.

Ultimately, competition with Beijing defines American foreign policy today, meaning Washington prioritizes relations with Pakistan’s archnemesis India, which is a key partner in the Biden Administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy to contain China. Toward that imperative, the White House turns a blind eye even to New Delhi’s continued close relationship with Putin. The U.S. kinship with India may mean Pakistan was always destined to move closer to China. But after the U.S. pulled out of Afghanistan, Pakistan is not the strategic lynchpin it once claimed to be—and memories are hardly fond; Pakistan secretly invested heavily in the Taliban. “Lots of Americans in Washington say we lost the war in Afghanistan because the Pakistanis stabbed us in the back,” says Munter.

What happens next? Many in Khan’s PTI suspect the current government may declare their party a terrorist organization or otherwise ban it from politics. Others believe that Pakistan’s escalating economic, political, and security turmoil may be used as grounds to postpone October’s general election. Ultimately, all sides are using the tools at their disposal to prevent their own demise: Khan wields popular protest and the banner of democracy; the government has the courts and security apparatus. Caught between the two, the people flounder. “There are no heroes here,” says Kugelman. “The entire political class and the military are to blame for the very troubled state the country finds itself in now.”

It’s a crisis that Khan still claims can be solved by elections, despite his broken relationship with the military. “The same people who tried to kill me are still sitting in power,” he says. “And they are petrified that if I got back [in] they would be held accountable. So they’re more dangerous.”

—With reporting by Hasan Ali/Islamabad

2 notes

·

View notes