#U.S. Airmen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

#youtube#militarytraining#Aeromedical Evacuation#Global Patient Movement Exercise#Patient Transport#Travis AFB#Airmen Training#Emergency Response#Air Mobility Command#Combat Readiness#War Games#Medical Evacuation#Air Force#Military Training#Military Personnel#Air Force Base#Medical Training#United States Air Force#Military Operations#Military Exercise#Military Exercises.#U.S. Airmen

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.S. Airmen during a small unit training at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska.

The U.S. Air Force photo by Alejandro Peña (2020).

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peace is our profession.

#vintage illustration#u.s. military#u.s. army#army#united states armed forces#united states army#air force#u.s. air force#united states air force#peace-keeping forces#soldiers#airmen#peace keeping

0 notes

Text

Paul Adams 1920-2013, joined the Tuskegee Airmen shortly after graduating from South Carolina State University. He flew with the 332nd Fighter Squadron (the famed "Red Tails") throughout WWII. He would retire from the military in 1962. He then would become a teaching in the Lincoln (NE) public school system. They named Adams Elementary school for him in 2008.

Paul Adams and his fellow Tuskegee Airmen were the first African-American aviators in the U.S. military, whose distinguished record many historians credit with helping pave the way for the civil rights movement.

The group set an unprecedented record, flying more than 1,500 missions in Europe and North Africa. Adam served in nine major campaigns and received the Commendation Medal with three Oak Leaf clusters, each of which signifies subsequent bestowals of the same honor.

Doane College recognized him with the President's Honor of Distinction Award the same year. In 2007, he received the Congressional Gold Medal along with other Tuskegee Airmen, who were known as "guardian angels" by white airmen who were escorted by the African-American pilots during the war. Adams received a bronze replica at a ceremony in Lincoln. Doane College recognized him with the President's Honor of Distinction Award the same year.

And two years later, Adams, at President Barack Obama's invitation, attended the inauguration of the first black president along with other Tuskegee Airmen. Adams went on to become one of the first black teachers in LPS, and in 2008, his accomplishments were honored when the district named a new school after him.

He became a frequent visitor at Adams Elementary, where books about Tuskegee Airmen fill the library and teachers make a point to read them to students. The history became an integral part of Adams Elementary school

#black tumblr#black history#black literature#black excellence#black community#civil rights#black history is american history#blackexcellence365#tuskegee airmen#american history

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

The U.S. Air Force Temporarily Moves 17 B-1B Bombers to Grand Forks AFB in North Dakota

David Cenciotti

B-1 to Grand Forks AFB

Seventeen aircraft and 800 people will relocate to Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota, while Ellsworth Air Force Base, in South Dakota, is readied for the arrival of the B-21 Raider.

Beginning this month, the U.S. Air Force will temporarily transfer 17 B-1B Lancer bombers and 800 Airmen from Ellsworth Air Force Base, South Dakota, to Grand Forks AFB in North Dakota. The relocation is expected to last about 10 months, during which Ellsworth will undertake all the works required to welcome the Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider.

While at Grand Forks, the BONEs (the unofficially nickname of the bomber, from B-One) of the 28th Bomb Wing, will still carry out their usual assignments.

According to Col. Derek Oakley, the wing’s commander, the runway work is a big step toward getting ready for the Raider. He also noted how it reflects the Air Force’s dedication to the long-range bomber program and its impact on the local community.

“The runway construction at Ellsworth is a key milestone in ensuring we’re ready to receive the B-21 Raider. This project illustrates the U.S. Air Force’s commitment to our nation’s newest long-range strike bomber and to the surrounding community.”

In a press release, the U.S. Air Force said that Ellsworth residents might see more construction-related activity, while people living near Grand Forks should expect heavier military traffic and aircraft noise as operations ramp up.

B-1B relocation Grand Forks

A U.S. Air Force B-1B Lancer assigned to the 28th Bomb Wing, Ellsworth Air Force Base, South Dakota, takes off at Luleå-Kallax Air Base, Sweden, Feb. 26, 2024, during Bomber Task Force 24-2. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Jake Jacobsen)

The first two Ellsworth’s bombers are expected to arrive at their “new” base this week, ahead of the full fleet’s arrival in early 2025. Routine inspections and repairs will take place at Grand Forks, but larger maintenance tasks will be handled by the 7th Bomb Wing at Dyess AFB, Texas. From there, Ellsworth bombers were launched in Global Strike missions in Iraq and Syria: in the night between Feb. 2 and 3, 2024, they took part in the air strikes on seven facilities, which included more than 85 targets in Iraq and Syria, that Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and affiliated militias used to attack U.S. and Coalition Forces in northeastern Jordan which had killed three U.S. soldiers on Jan. 28.

The 319th RW at Grand Forks AFB, is the headquarters operating the RQ-4B Global Hawk high-altitude, long-endurance Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance unmanned aircraft launched and flown remotely all over the world. Supporting a critical Air Force mission, sensor operators of the 319th RW analyze pattern-of-life data to help protect NATO’s eastern flank and oversee several strategically important operational areas.

Col. Tim Monroe of the 319th Reconnaissance Wing highlighted the benefits of integrating B-1 operations into Grand Forks’ existing drone-focused setup, which uses RQ-4B Global Hawks for surveillance worldwide:

“There’s no doubt integrating the B-1 community into our Grand Forks Unmanned Aerial System ecosystem will pay dividends for everyone involved. This temporary relocation is the vanguard of Air Force integration, readiness, and agile combat employment, and epitomizes the mantra of One Team, One Fight.”

Once Ellsworth’s runway upgrades are completed, the bombers and Airmen will head back home, paving the way for the B-21 Raider’s arrival in the mid-2020s.

Ellsworth was selected as the first B-21 Raider base after it cleared an EIA (Environmental Impact Assessment) report in 2021. Whiteman and Dyess AFBs in Missouri and Texas, respectively, were later designated the second and third bases for the bomber by Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall in mid-September.

Grand Forks was previously a B-1B base, until the bombers were relocated in 1994. In anticipation of the possible relocation, a hot-pit refueling, the first in 30 years at the base in North Dakota, was carried out by the 28th BW with support by the 319th Reconnaissance Squadron, on Oct. 1, 2024, to assess the possibility of relocating the bombers. In fact, while the majority of the physical infrastructures, including the required runway length, ordnance storage capacity, and aircraft refueling equipment, are still present, the 29th BW and the 319th RS still had to demonstrate the ability to operate the B-1B from non-home base locations.

@TheAviationist.com

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

History They Didn't Teach You In School

Scholars have left him out of the history books and Hollywood couldn’t be bothered to acknowledge his existence either. He was Howard Hughes’ top engineer and lifelong best friend. This is about Frank Mann, the hidden genius behind much of Howard Hughes’ success in the world of aviation and mechanics. Frank Calvin Mann (November 22, 1908 – November 30, 1992) was an African American engineer who was known for his participation in many Howard Hughes's projects including the Spruce Goose. He also starred in the Amos 'n' Andy radio show. Apparently, his lifelong friendship with Hughes was instrumental in opening doors for Mann's exceptional talents.

A native of Houston, Texas, Frank Calvin Mann's parents wanted him to become a schoolteacher, but from childhood, he had a natural ability to fix things. At age 11, he had his own mechanic shop. As a teenager, he worked alongside airplane mechanics, repairing engines. By the ago of 20, he had designed and built several of his own Model-T cars. It was unheard of in the 1920s for a Black man to have anything to do with cars, trains, or airplanes. His life-long friend Howard Hughes was instrumental in opening doors for Mann's exceptional talents.

Mann attended the University of Minnesota and UCLA where he earned a mechanical engineering degree. World War II equipment that revolutionized military weaponry would not exist if not for his involvement. Incredibly, few Americans are aware of Frank Mann. He was the first Black commercial pilot for American Airways. He was also a distinguished military officer. In 1935, following Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia, Frank Mann flew reconnaissance missions for the Ethiopian army.

He served in the World War II Army Air Corps and was the primary civilian instructor of the famous Tuskegee Airmen in 1941. He left Tuskegee after a rift with the U.S. government, which didn't want the Squadron, an all-Black unit, flying the same high caliber of airplanes as their White counterparts. An angry Mann had refused to have his men fly old "World War I biplane crates," because his airmen had proven themselves as equals.

Though they were being given inferior equipment and materials, their squadron never lost a plane, bomber, or pilot, and they were nicknamed the "Red Tails.” After the war, Mann was instrumental in designing the first Buick LeSabre automobile and the first communications satellite launched for commercial use.

His pride and joy was a miniature locomotive enshrined in the Smithsonian Institute, Mann also played a principal role in the Amos ‘N’ Andy radio show. He moved back to his hometown in the 1970s.

Frank Mann died November 30, 1992 in Houston.

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

U.S. Air Force special tactics Airmen with the 320th Special Tactics Squadron pull an MC-130J Commando II across the flightline during Monster Mash, an operational readiness and resilience training exercise May 5, 2023, at Kadena Air Base, Japan

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

F-15C Eagles from the 44th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron - PICRYL - Public Domain Media Search Engine Public Domain Search

Download Image of F-15C Eagles from the 44th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron. Free for commercial use, no attribution required. F-15C Eagles from the 44th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron takeoff at Prince Sultan Air Base, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Aug. 25, 2020. The 44th EFS conduct flying sorties daily to deliver air dominance in the U.S. Central Command's area of responsibility. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Cary Smith). Dated: 24.08.2020. Topics: deployed, centcom, uscentcom, saudi arabia, deterrence, afcent, f 15 eagle, usafcent, air force, united states air force, usaf, air dominance, deployed airmen, kingdom of saudi arabia, ksa, cary smith, staff sgt cary smith, prince sultan air base, psab, 378 aew, 378th air expeditionary wing, 378th aew, wintoday, prevailtomorrow, 44 efs provides deterrence support to region, dvids, ultra high resolution, high resolution, jet aircraft, military aircraft, us air force

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#6643 – World Armies, U.S. Air Force Special Warfare Airmen, link here: flickr

17 notes

·

View notes

Video

SC National Guard welcomes the community to the 2017 Air and Ground Expo A South Carolina Army National Guard M1A2 Abrams Main Battle Tank and AH-64 Apache helicopter provide fire power while paticipating in a Combined Arms Demonstration during the South Carolina National Guard Air and Ground Expo at McEntire Joint National Guard Base, South Carolina, May 5, 2017. This expo is a combined arms demonstration showcasing the abilities of South Carolina National Guard Airmen and Soldiers while saying thank you for the support of fellow South Carolinians and the surrounding community.(U.S. Army National Guard photo by Sgt. Tashera Pravato)

(via SC National Guard welcomes the community to the 2017 Air a… | Flickr)

#flickr#american armor#american tanks#army aviation#tank#tankers#us army#national guard#south carolina#abrams#apache#helicopter#char#tahk#tanque#kampfpanzer

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#youtube#militarytraining#usmilitary#Combat Readiness#Airmen#Tactical Operations#Combat Preparation#Air Force News#Air Force#Joint Exercises#Bamboo Eagle 24-3#Military Training#Military Life#Air Force Combat#Military Exercise#Air Force Operations#Defense Training#Tactical Training#Combat Exercise#Military Aviation#U.S. Military#Training Exercise#U.S. Airmen

1 note

·

View note

Text

Major General Claire L Chennault, Commander of the 14th Air force, drops in for a chat with U.S. airmen in China.

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

The collapse of the Afghan state amid the United States’ withdrawal in 2021 gifted the new Taliban government with more than $7 billion worth of U.S. military equipment. Afghanistan’s new overlords suddenly found themselves with fleets of Humvees, mountains of machine guns, and forests of radars and satellite dishes. The vast hardware hoard also included dozens of aircraft: a motley mix of Hind and Blackhawk helicopters, cargo planes, and close air support props.

Before the Taliban even had time to inventory their new arsenal, Egyptian filmmaker Ibrahim Nash’at arrived in Kabul. From his home in Berlin, he had seen the scenes of civilians storming Kabul’s international airport in a desperate attempt to flee, and he had managed to obtain permission to come to Afghanistan and film. But his plan—to record the suffering of ordinary Afghans—was swiftly dashed. Accompanied by a Taliban minder at all times and forbidden to film anyone other than a Taliban commander and his men, Nash’at was forced to switch tack. That commander happened to be Mawlawi Mansour, the Taliban fighter in charge of creating a new Taliban air force from the equipment and pilots who were left behind.

Under orders from Mansour, Nash’at became the unexpected chronicler of a high-profile facet of Afghanistan’s regime change. The result is Hollywoodgate, a 90-minute documentary named after the sprawling U.S. base in Kabul, where the Taliban created their new air force after U.S. forces fled. In a total of seven months in the new Afghanistan and assisted only by a lone translator, Nash’at shot 220 hours of footage, later culled down with a team of five producers and nine Afghan translators. Overcoming his subjects’ extreme suspicion, Nash’at managed eventually to blend into Taliban meetings, inspections, and military missions, becoming so invisible that his subjects forgot about his camera and relaxed.

Mansour takes command of the former U.S. air base and immediately sets to work. He inspects his new force and is impressed by the scale of U.S. resources. But he is appalled by their Spartan aesthetics; “plant some trees here” is a constant command to scurrying subordinates as Mansour strides across the base. Taliban conversations show a sudden inversion: Off-screen holdouts against the new regime are “the insurgents” opposed by “our special forces.”

For Mansour’s men, the order of the day is repairing aircraft, many of which were purposely disabled by departing U.S. forces. After a perfunctory grilling, a handful of pilots from the old Afghan air force are welcomed into the new force. (Many others had fled with their aircraft to neighboring countries.) Training new Taliban pilots will take time, but Mansour gets a course up and running, his lecturers aided by a cardboard mock-up of a cockpit.

Women are immediately pushed to the margins of the new Afghanistan. With a whiff of amusement at their past effrontery, Mansour dictates that women in his ministry may return to work, but only if they are veiled. His own wife, he brags to his staff, is a doctor, but he restricted her to the home upon marriage.

The mood among Mansour’s future Taliban airmen is upbeat. We see low-ranking fighters exulting in their victory over the Americans and “the Jews.” An ambitious lieutenant is showered in confetti to celebrate his acceptance into the new air force academy. A gleeful door guard flags every comrade passing him in the hall with his U.S.-made M-4 rifle—the cocktail of frivolity and danger that characterizes many an insurgency or militia in the poorest parts of the world.

At times, the new overlords can verge on endearing. Mansour and his men visit the base’s well-appointed gym, where one Talib struggles to press a pair of dumbbells above his head. The boss steps on a treadmill and happily plods along, ordering one sent to his home “to make my belly smaller.”

I witnessed a very similar scene when I was deployed to Afghanistan as a U.S. Marine more than a decade ago. When we handed over a coalition patrol base to one of the Afghan government’s paramilitary forces, the incoming commander breezed by the fortifications, operations center, and mess hall. But a derelict elliptical trainer in our sandy outdoor gym fascinated him. He hopped aboard with a big grin and churned away, to the bemusement of the handful of watching Marines.

Outside the tight circle in which he was permitted to film, Nash’at was far less welcome, he told me in an interview this summer. In his wordless brushes with Afghan civilians, he felt indicted by their stares. He was convinced that they saw him as an Arab propagandist—a voyeur who had come to Afghanistan to see and celebrate the Taliban’s triumph.

Despite the restrictions placed on him as an outsider, Nash’at managed to get glimpses of ordinary Afghan life. Children occasionally appear onscreen, and we get a sense of the extent to which they have been formed and traumatized by a lifetime of war. Hanging on a tow ring of a hulking mine-resistant vehicle, one boy in a camouflage shalwar kameez mumbles that he will “take a weapon and kill you all.”

After months of maintenance, training, and reorganization, Mansour gets his triumph. Toward the end of Nash’at’s filming, the Taliban stage a military parade for their own men and a handful of Russian, Chinese, and Iranian dignitaries. After a show of marching infantry, armored vehicles, and a battalion intended for suicide bombing on motorcycles, Hinds and Blackhawks fly past the grandstand. It’s a successful first operation for the Taliban’s new air force, even if the fly-by is bit too fast for Mansour’s liking.

In the film’s final scene, Mansour is seen on his cell phone berating an official at the Tajikistan Defense Ministry for harboring the Taliban’s enemies. Nash’at told me he believes that many Taliban have aims beyond Afghanistan’s borders. One high-ranking leader told him, “I can’t wait until we conquer Egypt.” The Taliban believe they and their forebears have turned Afghanistan into the graveyard of empires, defeating the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and now the United States. One fighter exults that “with American weapons we will rule the world!”

Whatever their intentions, the film also leaves viewers skeptical of the Taliban’s ability to wield meaningful military power. Like many journalists since then, Nash’at immediately picked up on the boredom among the Taliban fighters that followed on the heels of military victory. While negotiating Kabul’s traffic in a sedan just weeks after the city’s fall, one of Mansour’s lieutenants tells the filmmaker that he already longs for war: the return of the Americans, 500 bullets, and martyrdom. Late in the film, an enthusiastic crowd of Taliban tries to pile into an aircraft for a VIP test flight and are beaten off with curses by Mansour’s men. Afghanistan’s new rulers are likely to have their hands full just keeping discipline among their own former fighters.

Nash’at likened the realities of governing after fighting to coming down from a narcotic high. Building a bureaucracy seems much harder work than winning a war. Staff meetings and wrangling over budgets are a poor substitute for ambushes and assaults. Early in the film, one Talib waxes nostalgic for the life of an insurgent, showing Nash’at the cave he and a few other men took refuge in.

Despite his fear and disgust of the Taliban, Nash’at believes that the West should engage them. He said that if they are ignored, they will act out for the world’s attention, to the detriment of their own people and the region. But he harbors no illusions that such engagement will yield swift changes in the character of the Taliban.

With Hollywoodgate, now streaming after a limited theatrical release, Nash’at may not have made the film he originally set out to make. The suffering of the Afghan people was walled off from him. The Taliban’s strictures confined him to a narrow lane and, as he notes in an introductory voice-over, to the story they wanted to tell the world. But if the Taliban thought that they had put Nash’at on a short enough leash to force him to produce a piece of propaganda for the new regime, they were mistaken, too.

After Mansour’s air show, Taliban secret police demanded that Nash’at come to their office and show them all of his footage. As he told IndieWire in an interview, he knew then that his work was done: “I was filming the transformation of a militia into a military regime, and I realized at that moment the transformation was complete.” Through empathy, patience, and not a little audacity, Nash’at succeeded in capturing a story of Afghan nation-building—but a far different one than almost any Westerner could have imagined 20 years before.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lee "Buddy" Archer was a decorated Tuskegee Airman and World War II fighter pilot, known for his skill and bravery. Born on September 6, 1919, in Yonkers, New York, Archer broke barriers by joining the U.S. Army Air Corps and becoming one of the first Black aviators trained at Tuskegee Army Airfield. Serving with the 332nd Fighter Group, the legendary "Red Tails," Archer flew 169 combat missions in Europe.

On October 12, 1944, he secured three confirmed aerial victories in a single mission, making him one of the Tuskegee Airmen’s top aces. Archer received the Distinguished Flying Cross and later a Congressional Gold Medal for his contributions. After retiring from the military, he succeeded in business, becoming a General Foods vice president. Archer passed away in 2010, leaving a legacy of courage and excellence.

#blackexcellence#blackunity#redtails#buddyleearcher#tuskegee airmen#blackpower#blackhistory#TuskegeeAirmen#BlackHistory#WWIIFighterPilot#RedTails#BlackAviators#HeroicLegacy

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in 1941, the U.S. Army establishes the 99th Pursuit Squadron, America's first all-Black flying unit. They'll go down in history as the "Tuskegee Airmen" — a reference to the group's Alabama training field.

@Milhistorynow via X

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

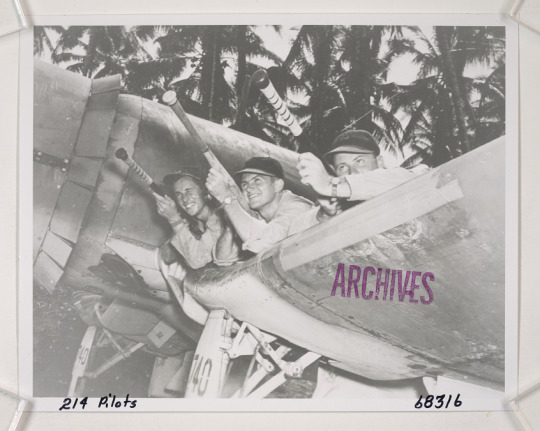

Black Sheep Squadron (VMF-214) – WWII Boyington

Record Group 127: Records of the U.S. Marine CorpsSeries: Photographic Reference FileFile Unit: General – Black Sheep Squadron (VMF-214) – WWII Boyington

This black and white photograph shows three Marine pilots posing with baseball bats over the wing of a military plane. They are holding the bats as though they were guns. All three wear St. Louis Cardinals’ caps. Palm trees are in the background.

Transcription of text from the reverse of the photo:

WEARING CARDINAL CAPS: These Leather- neck fighter pilots in the South Pacific hope to catch more Japanese airmen off base. The baseball motif was inspired by 20 caps sent Major Gregory Boyington's Squadron by the St. Louis Cardinals. The ball caps were worn traditionally by Marine pilots when not actually flying. Left to right: On a Corsair fighter Wing, 1st Lieutenant Robert W. McClurg, 3 Zeros; 1st Lieutenant Paul A. Mullen, 3 Zeros; 1st Lieutenant Edwin L. Olander, 3 Zeros.

39 notes

·

View notes