#Typist Girl (1926)

Text

In the early 1930s, scholarly studies were done on the impact of screen stars on teenagers, because of fears that the movies were sexualizing them. These studies found that teenage girls learned sex techniques through watching Garbo’s sex scenes, especially those in Flesh and the Devil; they then practiced her techniques at home with their girlfriends. Raymond Daum described Garbo’s many young female fans as having “schoolgirl crushes on her” that “defined a national idolatry.” And knowledge of Garbo’s non-heteronormative sexuality was spread through lesbian networks “from coast to coast.” Moreover, the 1920s was an era of commercial expansion in which the ranks of saleswomen and typists, careers dominated by young women, increased. These women made enough money to see a movie more than once. They identified with female stars and liked to see them in powerful roles.

Greta Garbo in Flesh and the Devil (1926)

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

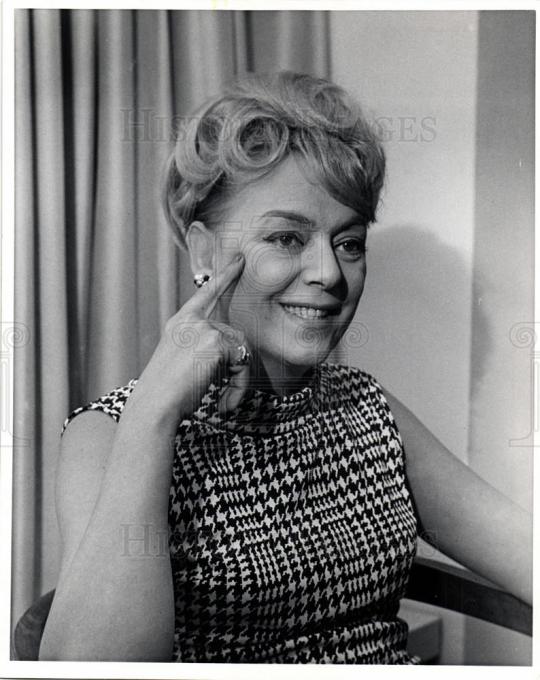

Remembering Ruby Myers (1907 – 10 October 1983), better known by her stage name Sulochana on her 113th birth anniversary.

Ruby was a silent film actress of Jewish ancestry, hailing from the community of Baghdadi Jews in India.

In her heyday, she was one of the highest paid actresses of her time, when she was paired with Dinshaw Billimoria in Imperial Studios films. In mid-1930 she opened Rubi Pics, a film production house.

She was awarded the 1973 Dada Saheb Phalke Award, India's highest award in cinema for lifetime achievement.

Ruby Myers was born in 1907 in Pune. Chubby, petite and brown-eyed, the self-named Sulochana was among the early Eurasian female stars of Indian Cinema.

She was working as a telephone operator when she was approached by Mohan Bhavnani of Kohinoor Film Company to work in films. Though excited by the offer, she turned him down as acting was regarded as quite a dubious profession for women those days. However Bhavnani persisted with his offer and she finally agreed, despite having no knowledge of acting whatsoever. She became a star under Bhavnani's direction at Kohinoor before moving on to the Imperial Film Company where she became the highest paid movie star in the country.

Among her popular films were Typist Girl (1926), Balidaan (1927) and Wildcat of Bombay (1927) where she essayed eight roles including a gardener, a policeman, a Hyderabadi gentleman, a street urchin, a banana seller and a European blonde.

Three romantic super hits in 1928 - 29 with director R.S. Chaudhari - Madhuri (1928), Anarkali (1928) and Indira B.A. (1929) saw her at her peak of fame in the silent film era. In fact so widespread was her fame that when a short film on Mahatma Gandhi inaugurating a khadi exhibition was shown, alongside it was added a hugely popular dance of Sulochana's from Madhuri, synchronized with sound effects.

With the coming of sound, Sulochana suddenly found a lull in her career, as it now required an actor to be proficient in Hindustani. Taking a year off to learn the language, she made a grand comeback with the talkie version of Madhuri (1932).

Further talkie versions of her silent hits followed and with Indira (now an) M.A. (1934), Anarkali (1935) and Bombay ki Billi (1936). Sulochana was back with a bang. She was drawing a salary of Rs 5000 per month, she had the sleekest of cars (Chevrolet 1935) and one of the biggest heroes of the silent era, D. Billimoria, as her lover with whom she worked exclusively between 1933 and 1939. They were an extremely popular pair - his John Barrymore-style opposite her Oriental 'Queen of Romance' image.

But once their love story ended so did their careers. Sulochana left Imperial to find few offers forthcoming. Newer, younger and more proficient actresses had entered the scene. She tried making a comeback with character roles but even these were few.

However, she still had the power to excite controversy. In 1947, Morarji Desai banned the Dilip Kumar - Noor Jehan starrer, Jugnu, because it showed such a morally reprehensible act as an aging fellow professor falling for Sulochana's vintage charms.

In 1953, she acted in her third Anarkali, but this time in a supporting role as Salim's mother.

She died in 1983 in her flat in Mumbai.

Her films include Cinema Queen (1926), Typist Girl (1926), Balidaan (1927), Wild Cat of Bombay, in which she played eight different characters, which was remade as Bambai Ki Billi (1936); Madhuri (1928), which was re-released with sound in 1932; Anarkali (1928), remade in 1945; Indira BA (1929); Heer Ranjah (1929), and many others, such as Baaz (1953).

Sulochana established her own film studio, Rubi Pics, in the mid-1930s. She received the Dada Saheb Phalke Award in 1973 for her lifetime contribution to Indian cinema. Ismail Merchant paid homage to her in Mahatma and the Bad Boy (1974).

#Ruby Myers#Sulochana#Dinshaw Billimoria#Cinema Queen (1926)#Typist Girl (1926)#Balidaan (1927)#Wild Cat of Bombay#Bambai Ki Billi (1936)#Madhuri (1928)#Anarkali (1928)#Indira BA (1929)#Heer Ranjah (1929)#bollywood#bollywoodirect

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christine Jorgensen (May 30, 1926 – May 3, 1989) was an American transgender woman who was the first person to become widely known in the United States for having sex reassignment surgery. Jorgensen grew up in the Bronx, New York City. Shortly after graduating from high school in 1945, she was drafted into the U.S. Army during World War II. After her military service, she attended several schools and worked; it is during this time she learned about sex reassignment surgery. Jorgensen traveled to Europe, and in Copenhagen, Denmark, obtained special permission to undergo a series of operations beginning in 1952.

She returned to the United States in the early 1950s and her transition was the subject of a New York Daily News front-page story. She became an instant celebrity, known for her directness and polished wit, and used the platform to advocate for transgender people. She also worked as an actress and nightclub entertainer and recorded several songs. Jorgensen often lectured on the experience of being transgender and published an autobiography in 1967.

Jorgensen was the second child of carpenter and contractor George William Jorgensen, Sr., and his wife Florence Davis Hansen, and given a male name at birth. She was raised in the Belmont neighborhood of the Bronx, New York City. She later described herself as having been a "frail, blond, introverted little boy who ran from fistfights and rough-and-tumble games".

Jorgensen graduated from Christopher Columbus High School in 1945 and was soon drafted into the U.S. Army at the age of 19. After being discharged from the Army, she attended Mohawk Valley Community College in Utica, New York,[5] the Progressive School of Photography in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Manhattan Medical and Dental Assistant School in New York City. She also worked briefly for Pathé News.

Returning to New York after military service, and increasingly concerned over, as one obituary later called it, a "lack of male physical development", Christine Jorgensen heard about sex reassignment surgery. She began taking estrogen in the form of ethinylestradiol and started researching the surgery with the help of Joseph Angelo, the husband of a classmate at the Manhattan Medical and Dental Assistant School. Jorgensen intended to go to Sweden, where the only doctors in the world who then performed the surgery were located. During a stopover in Copenhagen to visit relatives, she met Christian Hamburger, a Danish endocrinologist and specialist in rehabilitative hormonal therapy. Jorgensen stayed in Denmark and underwent hormone replacement therapy under Hamburger's direction. She chose the name Christine in honor of Hamburger.

She obtained special permission from the Danish Minister of Justice to undergo a series of operations in that country. On September 24, 1951, surgeons at Gentofte Hospital in Copenhagen performed an orchiectomy on Jorgensen. In a letter to friends on October 8, 1951, she referred to how the surgery affected her:

As you can see by the enclosed photos, taken just before the operation, I have changed a great deal. But it is the other changes that are so much more important. Remember the shy, miserable person who left America? Well, that person is no more and, as you can see, I'm in marvelous spirits.

In November 1952, doctors at Copenhagen University Hospital performed a penectomy. In Jorgensen's words, "My second operation, as the previous one, was not such a major work of surgery as it may imply."

She returned to the United States and eventually obtained a vaginoplasty when the procedure became available there. The vaginoplasty was performed under the direction of Angelo, with Harry Benjamin as a medical adviser. Later, in the preface of Jorgensen's autobiography, Harry Benjamin gave her credit for the advancement of his studies. He wrote, "Indeed Christine, without you, probably none of this would have happened; the grant, my publications, lectures, etc."

The New York Daily News ran a front-page story on December 1, 1952, under the headline "Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty", announcing (incorrectly) that Jorgensen had become the recipient of the first "sex change". This type of surgery had previously been performed by German doctors in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Dorchen Richter and Danish artist Lili Elbe, both patients of Magnus Hirschfeld at the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in Berlin, were known recipients of such operations in 1930–31.

After her surgeries, Jorgensen originally stated that she wanted a quiet life of her own design, but once returning to the United States, the only way she could manage to earn a living was by making public appearances. Jorgensen was an instant celebrity when she returned to New York in February 1953. A large crowd of journalists met her as she came off her flight, and despite the Danish royal family being on the same flight, they were largely ignored in favor of her. Soon after her arrival, she launched a successful nightclub act and appeared on TV, radio, and theatrical productions. The first of a five-part authorized account of her story was written by Jorgensen herself in a February 1953 issue of The American Weekly, titled "The Story of My Life" and in 1967, she published her autobiography, Christine Jorgensen: A Personal Autobiography, which sold almost 450 thousand copies.

The publicity following her transition and gender reassignment surgery became "a model for other transsexuals for decades. She was a tireless lecturer on the subject of transsexuality, pleading for understanding from a public that all too often wanted to see transsexuals as freaks or perverts ... Ms Jorgensen's poise, charm, and wit won the hearts of millions." However, over time the press was much less fascinated by her and started to scrutinize her much more harshly. She was often asked by print medias if she would pose nude in their publications.

Knox and Jorgensen after being denied a marriage license, April 1959. After her vaginoplasty, Jorgensen planned to marry labor union statistician John Traub, but the engagement was called off. In 1959 she announced her engagement to typist Howard J. Knox in Massapequa Park, New York, where her father had built her a house after her reassignment surgery. However, the couple was unable to obtain a marriage license because Jorgensen's birth certificate listed her as male. In a report about the broken engagement, The New York Times reported that Knox had lost his job in Washington, D.C., when his engagement to Jorgensen became known.

After her parents died, Jorgensen moved to California in 1967. She left behind the ranch home built by her father in Massapequa and settled at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, California, for a period of time. It was also during this same year that Jorgensen published her autobiography, Christine Jorgensen: A Personal Autobiography, which chronicled her life experiences as a transsexual and included her own personal perspectives on major events in her life.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Jorgensen toured university campuses and other venues to speak about her experiences. She was known for her directness and polished wit. She once demanded an apology from Vice President Spiro T. Agnew when he called Charles Goodell "the Christine Jorgensen of the Republican Party". (Agnew refused her request.)

Jorgensen also worked as an actress and nightclub entertainer and recorded several songs. In summer stock, she played Madame Rosepettle in the play Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma's Hung You in the Closet and I'm Feelin' So Sad. In her nightclub act, she sang several songs, including "I Enjoy Being a Girl", in which, at the end, she made a quick change into a Wonder Woman costume. She later recalled that Warner Communications, owners of the Wonder Woman character's copyright, demanded that she stop using the character; she did so, and instead used a new character of her own invention, Superwoman, who was marked by the inclusion of a large letter S on her cape. Jorgensen continued her act, performing at Freddy's Supper Club on the Upper East Side of Manhattan until at least 1982, when she performed twice in the Hollywood area: once at the Backlot Theatre, adjacent to the discothèque Studio One, and later at The Frog Pond restaurant. This performance was recorded and has been made available as an album on iTunes. In 1984, Jorgensen returned to Copenhagen to perform her show and was featured in Teit Ritzau's Danish transsexual documentary film Paradiset er ikke til salg (Paradise Is Not for Sale). Jorgensen was the first and only known trans woman to perform at Oscar's Delmonico Restaurant in downtown New York, for which owners Oscar and Mario Tucci received criticism.

She died of bladder and lung cancer in 1989, four weeks short of her 63rd birthday. Her ashes were scattered off Dana Point, California.

Jorgensen's highly publicized transition helped bring to light gender identity and shaped a new culture of more inclusive ideas about the subject. As a transgender spokesperson and public figure, Jorgensen influenced other transgender people to change their sex on birth certificates and to change their names. Jorgensen saw herself as a founding member in what became known as the "sexual revolution". Jorgensen stated in a Los Angeles Times interview, "I am very proud now, looking back, that I was on that street corner 36 years ago when a movement started. It was the sexual revolution that was going to start with or without me. We may not have started it, but we gave it a good swift kick in the pants."

In 2012 Jorgensen was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display which celebrates LGBT history and people.

In 2014, Jorgensen was one of the inaugural honorees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighborhood noting LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields".

In June 2019, Jorgensen was one of the inaugural 50 American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" included on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City's Stonewall Inn. The SNM is the first U.S. national monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and history, and the wall's unveiling was timed to take place during the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, during his earlier career as a calypso singer under the name The Charmer, recorded a song about Jorgensen, "Is She Is or Is She Ain't" (The title is a play on the 1940s Louis Jordan song, "Is You Is or Is You Ain't My Baby".)

Chuck Renslow and Dom Orejudos founded Kris Studios, a male physique photography studio that took photos for gay magazines they published, which was named in part to honor Jorgensen.

Posters for the Ed Wood film Glen or Glenda (1953), also known as I Changed My Sex and I Led Two Lives, publicize the movie as being based on Jorgensen's life. Originally producer George Weiss made her some offers to appear in the film, but these were turned down. Jorgenson is mentioned in connection with Glen in Tim Burton's biopic Ed Wood (1994), but Jorgenson is not depicted as a character.

The Christine Jorgensen Story, a fictionalized biopic based on Jorgensen's memoir, premiered in 1970. John Hansen played Jorgensen as an adult, while Trent Lehman played her at age seven.

In Christine Jorgensen Reveals, a stage performance at the 2005 Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Jorgensen was portrayed by Bradford Louryk. To critical acclaim, Louryk dressed as Jorgensen and performed to a recorded interview with her during the 1950s while video of Rob Grace as comically inept interviewer Nipsey Russell played on a nearby black-and-white television set. The show went on to win Best Aspect of Production at the 2006 Dublin Gay Theatre Festival, and it ran Off-Broadway at New World Stages in January 2006. The LP was reissued on CD by Repeat The Beat Records in 2005.

Transgender historian and critical theorist Susan Stryker directed and produced an experimental documentary film about Jorgensen, titled Christine in the Cutting Room. In 2010 she also presented a lecture at Yale University titled "Christine in the Cutting Room: Christine Jorgensen's Transsexual Celebrity and Cinematic Embodiment". Both works examine embodiment vis-à-vis cinema.

The 2016 book Andy Warhol was a Hoarder: Inside the Minds of History's Great Personalities, by journalist Claudia Kalb, devotes a chapter to Jorgensen's story, using her as an example of gender dysphoria and the process of gender transition in its earliest days.

Jorgensen, Christine (1967). Christine Jorgensen: A Personal Autobiography. New York, New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-1-57344-100-1.

#trans history#transgender woman#transgender#trans pride#postop transwomen#1950s#transisbeautiful#transwoman

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sulochana (Ruby Myers) was a silent film actress from the Baghdadi Jewish community of India. She was born in Pune in 1907. At the height of her career, she was the highest paid actress of her time. She worked as a telephone operator before entering the film industry. Some of her popular silent films were Typist Girl (1926), Wildcat of Bombay (1927), and Madhuri (1928). With the coming of sound, she had to take a year off to learn Hindustani (the language of the films) as she was not proficient. She made a comeback with the 1932 talkie version of Madhuri. Sulochana founded her own film production house, RubiPics in the mid-1930s. She received the Dada Saheb Phalke Award in 1973 for her lifetime contribution to Indian cinema. By the 1980s, she was a forgotten actress and died on October 10, 1983 in Mumbai.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbara Stanwyck (born Ruby Catherine Stevens; July 16, 1907 – January 20, 1990) was an American actress, model and dancer. A stage, film and television star, she was known during her 60-year career as a consummate and versatile professional for her strong, realistic screen presence. A favorite of directors including Cecil B. DeMille, Fritz Lang and Frank Capra, she made 85 films in 38 years before turning to television.

Stanwyck got her start on the stage in the chorus as a Ziegfeld girl in 1923 at age 16 and within a few years was acting in plays. She was then cast in her first lead role in Burlesque (1927), becoming a Broadway star. Soon after that, Stanwyck obtained film roles and got her major break when Frank Capra chose her for his romantic drama Ladies of Leisure (1930), which led to additional lead roles.

In 1937 she had the title role in Stella Dallas and received her first Academy Award nomination for best actress. In 1941 she starred in two successful screwball comedies: Ball of Fire with Gary Cooper, and The Lady Eve with Henry Fonda. She received her second Academy Award nomination for Ball of Fire, and in recent decades The Lady Eve has come to be regarded as a romantic comedy classic with Stanwyck's performance called one of the best in American comedy.

By 1944, Stanwyck had become the highest-paid woman in the United States. She starred alongside Fred MacMurray in the seminal film noir Double Indemnity (1944), playing the smoldering wife who persuades MacMurray's insurance salesman to kill her husband. Described as one of the ultimate portrayals of villainy, it is widely thought that Stanwyck should have won the Academy Award for Best Actress rather than being just nominated. She received another Oscar nomination for her lead performance as an invalid wife overhearing her own murder plot in the thriller film noir, Sorry, Wrong Number (1948). After she moved into television in the 1960s, she won three Emmy Awards – for The Barbara Stanwyck Show (1961), the western series The Big Valley (1966), and miniseries The Thorn Birds (1983).

She received an Honorary Oscar in 1982, the Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1986 and was the recipient of several other honorary lifetime awards. She was ranked as the 11th greatest female star of classic American cinema by the American Film Institute. An orphan at the age of four, and partially raised in foster homes, she always worked; one of her directors, Jacques Tourneur, said of Stanwyck, "She only lives for two things, and both of them are work."

Barbara Stanwyck was born Ruby Catherine Stevens on July 16, 1907, in Brooklyn, New York. She was the fifth – and youngest – child of Catherine Ann (née McPhee) (1870-1911) and Byron E. Stevens (1872-1919), working-class parents. Her father, of English descent, was a native of Lanesville, Massachusetts, and her mother, of Scottish descent, was an immigrant from Sydney, Nova Scotia. When Ruby was four, her mother died of complications from a miscarriage after she was knocked off a moving streetcar by a drunk. Two weeks after the funeral, her father joined a work crew digging the Panama Canal and was never seen again by his family. Ruby and her older brother, Malcolm Byron (later nicknamed "By") Stevens, were raised by their eldest sister Laura Mildred, (later Mildred Smith) (1886–1931), who died of a heart attack at age 45. When Mildred got a job as a showgirl, Ruby and Byron were placed in a series of foster homes (as many as four in a year), from which young Ruby often ran away.

"I knew that after fourteen I'd have to earn my own living, but I was willing to do that ... I've always been a little sorry for pampered people, and of course, they're 'very' sorry for me."

Ruby toured with Mildred during the summers of 1916 and 1917, and practiced her sister's routines backstage. Watching the movies of Pearl White, whom Ruby idolized, also influenced her drive to be a performer. At the age of 14, she dropped out of school, taking a package wrapping job at a Brooklyn department store. Ruby never attended high school, "although early biographical thumbnail sketches had her attending Brooklyn's famous Erasmus Hall High School."

Soon afterward, she took a filing job at the Brooklyn telephone office for $14 a week, which allowed her to become financially independent. She disliked the job; her real goal was to enter show business, even as her sister Mildred discouraged the idea. She then took a job cutting dress patterns for Vogue magazine, but customers complained about her work and she was fired. Ruby's next job was as a typist for the Jerome H. Remick Music Company; work she reportedly enjoyed, however her continuing ambition was in show business, and her sister finally gave up trying to dissuade her.

In 1923, a few months before her 16th birthday, Ruby auditioned for a place in the chorus at the Strand Roof, a nightclub over the Strand Theatre in Times Square. A few months later, she obtained a job as a dancer in the 1922 and 1923 seasons of the Ziegfeld Follies, dancing at the New Amsterdam Theater. "I just wanted to survive and eat and have a nice coat", Stanwyck said. For the next several years, she worked as a chorus girl, performing from midnight to seven a.m. at nightclubs owned by Texas Guinan. She also occasionally served as a dance instructor at a speakeasy for gays and lesbians owned by Guinan. One of her good friends during those years was pianist Oscar Levant, who described her as being "wary of sophisticates and phonies."

Billy LaHiff, who owned a popular pub frequented by showpeople, introduced Ruby in 1926 to impresario Willard Mack. Mack was casting his play The Noose, and LaHiff suggested that the part of the chorus girl be played by a real one. Mack agreed, and after a successful audition gave the part to Ruby. She co-starred with Rex Cherryman and Wilfred Lucas. As initially staged, the play was not a success. In an effort to improve it, Mack decided to expand Ruby's part to include more pathos. The Noose re-opened on October 20, 1926, and became one of the most successful plays of the season, running on Broadway for nine months and 197 performances. At the suggestion of David Belasco, Ruby changed her name to Barbara Stanwyck by combining the first name from the play Barbara Frietchie with the last name of the actress in the play, Jane Stanwyck; both were found on a 1906 theater program.

Stanwyck became a Broadway star soon afterward, when she was cast in her first leading role in Burlesque (1927). She received rave reviews, and it was a huge hit. Film actor Pat O'Brien would later say on a 1960s talk show, "The greatest Broadway show I ever saw was a play in the 1920s called 'Burlesque'." Arthur Hopkins described in his autobiography To a Lonely Boy, how he came to cast Stanwyck:

After some search for the girl, I interviewed a nightclub dancer who had just scored in a small emotional part in a play that did not run [The Noose]. She seemed to have the quality I wanted, a sort of rough poignancy. She at once displayed more sensitive, easily expressed emotion than I had encountered since Pauline Lord. She and Skelly were the perfect team, and they made the play a great success. I had great plans for her, but the Hollywood offers kept coming. There was no competing with them. She became a picture star. She is Barbara Stanwyck.

He also called Stanwyck "The greatest natural actress of our time", noting with sadness, "One of the theater's great potential actresses was embalmed in celluloid."

Around this time, Stanwyck was given a screen test by producer Bob Kane for his upcoming 1927 silent film Broadway Nights. She lost the lead role because she could not cry in the screen test, but was given a minor part as a fan dancer. This was Stanwyck's first film appearance.

While playing in Burlesque, Stanwyck was introduced to her future husband, actor Frank Fay, by Oscar Levant. Stanwyck and Fay were married on August 26, 1928, and soon moved to Hollywood.

Stanwyck's first sound film was The Locked Door (1929), followed by Mexicali Rose, released in the same year. Neither film was successful; nonetheless, Frank Capra chose Stanwyck for his film Ladies of Leisure (1930). Her work in that production established an enduring friendship with the director and led to future roles in his films. Other prominent roles followed, among them as a nurse who saves two little girls from being gradually starved to death by Clark Gable's vicious character in Night Nurse (1931). In Edna Ferber's novel brought to screen by William Wellman, she portrays small town teacher and valiant Midwest farm woman Selena in So Big! (1932). She followed with a performance as an ambitious woman "sleeping" her way to the top from "the wrong side of the tracks" in Baby Face (1933), a controversial pre-Code classic. In The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933), another controversial pre-Code film by director Capra, Stanwyck portrays an idealistic Christian caught behind the lines of Chinese civil war kidnapped by warlord Nils Asther. A flop at the time, containing "mysterious-East mumbo jumbo", the lavish film is "dark stuff, and its difficult to imagine another actress handling this ... philosophical conversion as fearlessly as Ms. Stanwyck does. She doesn't make heavy weather of it."

In Stella Dallas (1937) she plays the self-sacrificing title character who eventually allows her teenage daughter to live a better life somewhere else. She landed her first Academy Award nomination for Best Actress when she was able to portray her character as vulgar, yet sympathetic as required by the movie. Next, she played Molly Monahan in Union Pacific (1939) with Joel McCrea. Stanwyck was reportedly one of the many actresses considered for the role of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939), although she did not receive a screen test. In Meet John Doe she plays an ambitious newspaperwoman with Gary Cooper (1941).

In Preston Sturges's romantic comedy The Lady Eve (1941), she plays a slinky, sophisticated con-woman who falls for her intended victim, the guileless, wealthy snake-collector and scientist Henry Fonda, she "gives off an erotic charge that would straighten a boa constrictor." Film critic David Thomson described Stanwyck as "giving one of the best American comedy performances", and its reviewed as brilliantly versatile in "her bravura double performance" by The Guardian. The Lady Eve is among the top 100 movies of all time on Time and Entertainment Weekly's lists, and is considered to be both a great comedy and a great romantic film with its placement at #55 on the AFI's 100 Years ...100 Laughs list and #26 on its 100 Years ...100 Passions list.

Next, she was the extremely successful, independent doctor Helen Hunt in You Belong to Me (1941), also with Fonda. Stanwyck then played nightclub performer Sugerpuss O'Shea in the Howard Hawks directed, but Billy Wilder written comedy Ball of Fire (1941). In this update of the Snow White and Seven Dwarfs tale, she gives professor Gary Cooper a better understanding of "modern English" in the performance for which she received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress.

In Double Indemnity, the seminal film noir thriller directed by Billy Wilder, she plays the sizzling, scheming wife/blonde tramp/"destiny in high heels" who lures an infatuated insurance salesman (Fred MacMurray) into killing her husband. Stanwyck brings out the cruel nature of the "grim, unflinching murderess", marking her as the "most notorious femme" in the film noir genre. Her insolent, self-possessed wife is one of the screen's "definitive studies of villainy - and should (it is widely thought) have won the Oscar for Best Actress", not just been nominated. Double Indemnity is usually considered to be among the top 100 films of all time, though it did not win any of its seven Academy Award nominations. It is the #38 film of all time on the American Film Institute's list, as well as the #24 on its 100 Years ...100 Thrillers list and #84 on its 100 Years ...100 Passions list.

She plays the columnist caught up in white lies and a holiday romance in Christmas in Connecticut (1945). In 1946 she was "liquid nitrogen" as Martha, a manipulative murderess, costarring with Van Heflin and newcomer Kirk Douglas in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers. Stanwyck was also the vulnerable, invalid wife that overhears her own murder being plotted in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) and the doomed concert pianist in The Other Love (1947). In the latter film's soundtrack, the piano music is actually being performed by Ania Dorfmann, who drilled Stanwyck for three hours a day until the actress was able to synchronize the motion of her arms and hands to match the music's tempo, giving a convincing impression that it is Stanwyck playing the piano.

Pauline Kael, a longtime film critic for The New Yorker, admired the natural appearance of Stanwyck's acting style on screen, noting that she "seems to have an intuitive understanding of the fluid physical movements that work best on camera". In reference to the actress's film work during the early sound era, Kael observed that the "early talkies sentimentality...only emphasizes Stanwyck's remarkable modernism."

Many of her roles involve strong characters, yet Stanwyck was known for her accessibility and kindness to the backstage crew on any film set. She knew the names of their wives and children. Frank Capra said of Stanwyck: "She was destined to be beloved by all directors, actors, crews and extras. In a Hollywood popularity contest, she would win first prize, hands down." While working on 1954s Cattle Queen of Montana on location in Glacier National Park, she did some of her own stunts, including a swim in the icy lake.[49] A consummate professional, when aged 50, she performed a stunt in Forty Guns. Her character had to fall off her horse and, with her foot caught in the stirrup, be dragged by the galloping animal. This was so dangerous that the movie's professional stunt person refused to do it. Her professionalism on film sets led her to be named an Honorary Member of the Hollywood Stuntmen's Hall of Fame.

William Holden and Stanwyck were longtime friends and when Stanwyck and Holden were presenting the Best Sound Oscar for 1977, he paused to pay a special tribute to her for saving his career when Holden was cast in the lead for Golden Boy (1939). After a series of unsteady daily performances, he was about to be fired, but Stanwyck staunchly defended him, successfully standing up to the film producers. Shortly after Holden's death, Stanwyck recalled the moment when receiving her honorary Oscar: "A few years ago, I stood on this stage with William Holden as a presenter. I loved him very much, and I miss him. He always wished that I would get an Oscar. And so, tonight, my golden boy, you got your wish."

As Stanwyck's film career declined during the 1950s, she moved to television. In 1958 she guest-starred in "Trail to Nowhere", an episode of the Western anthology series Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre, portraying a wife who pursues, overpowers, and kills the man who murdered her husband. Later, in 1961, her drama series The Barbara Stanwyck Show was not a ratings success, but it earned her an Emmy Award. The show ran for a total of thirty-six episodes. She also guest-starred in this period on other television series, such as The Untouchables with Robert Stack and in four episodes of Wagon Train.

She stepped back into film for the 1964 Elvis Presley film Roustabout, in which she plays a carnival owner.

The western television series, The Big Valley, which was broadcast on ABC from 1965 to 1969, made her one of the most popular actresses on television, winning her another Emmy. She was billed in the series' opening credits as "Miss Barbara Stanwyck" for her role as Victoria, the widowed matriarch of the wealthy Barkley family. In 1965, the plot of her 1940 movie Remember the Night was adapted and used to develop the teleplay for The Big Valley episode "Judgement in Heaven".

In 1983, Stanwyck earned her third Emmy for The Thorn Birds. In 1985 she made three guest appearances in the primetime soap opera Dynasty prior to the launch of its short-lived spin-off series, The Colbys, in which she starred alongside Charlton Heston, Stephanie Beacham and Katharine Ross. Unhappy with the experience, Stanwyck remained with the series for only the first season, and her role as "Constance Colby Patterson" would be her last. It was rumored Earl Hamner Jr., former producer of The Waltons, had initially wanted Stanwyck for the role of Angela Channing in the 1980s soap opera Falcon Crest, and she turned it down, with the role going to her friend, Jane Wyman; when asked Hamner assured Wyman it was a rumor.

Stanwyck's retirement years were active, with charity work outside the limelight. In 1981, she was awakened in the middle of the night, inside her home in the exclusive Trousdale section of Beverly Hills, by an intruder, who first hit her on the head with his flashlight, then forced her into a closet while he robbed her of $40,000 in jewels.

The following year, in 1982, while filming The Thorn Birds, the inhalation of special-effects smoke on the set may have caused her to contract bronchitis, which was compounded by her cigarette habit; she was a smoker from the age of nine until four years before her death.

Stanwyck died on January 20, 1990, aged 82, of congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at Saint John's Health Center in Santa Monica, California. She had indicated that she wanted no funeral service. In accordance with her wishes, her remains were cremated and the ashes scattered from a helicopter over Lone Pine, California, where she had made some of her western films.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wang Hanlun

Continuing with the theme of famous actresses to emerge from China, we now turn our gaze to the everlasting Wang Hanlun. Born Peng Jianqing in what is now an epicenter of attraction and business, Suzhou, but at the time of her birth in 1903 consisted of just four small suburbs across a few islands connected only by gently flowing rivers. It is in the quiet town that the second of the four actresses we will look at was born and raised.

Much like with Xuan in the previous post, Art imitated life, though with her it was done purposefully it seemed at times. With Jianqing however, an unrelated film released thirteen years after her death, “Raise the Red Lantern” (1991), the protagonist goes through life eerily similar compared to Jianqing.

Coming from a large family (nine in all, six other siblings, then her mother and father), she was often described as her father’s favorite. So much so that Jianqing was sent to a private school “St. Mary’s School for Women in Shanghai,”

she spent her time happily there until the age of sixteen when her father passed away. With her father’s passing, there were financial restrictions on the family and they could no longer afford the expensive private school that Jianqing had grown accustomed to. Her family had always been very strict, making sure that they kept up with the traditions of their ancestors and the expectations of the times, therefore shortly after she was pulled out of school a marriage was arranged between Jianqing and wealthy coal miner by the name of Zhang.

It was at this time that Jianqing began suffering from Depression. The combination of being pulled from school, her father dying and being forced into a marriage she wanted no part of wore on her immensely. She did however continue. Living through the expectations that were placed upon her, no matter how unhappy they made her. Although Jianqing had grown content with her current situation it was about to become much worse. It was soon discovered that her husband was cheating on her since the beginning of the marriage, and moreover, had no qualms about it, stating “it’s not unusual for a man of means to have 3 or 4 wives, so don’t trouble yourself about it.”

Knowing that the well-being of her family depended on this marriage, Jianqing accepted the adultery. Though many people believe it is at this point, not later in the story, where she lost all love for her husband.

As it turns out, Zhang’s company was a Sino-Japanese enterprise (this was in between the first and second Sino-Japanese War, with tension running high). Jianqing accompanied her husband on a business trip to Shanghai when she found this bit of information out. While there she found something even more explosive. Zhang reach went far beyond the coal mines and monetary, he played an intricate role with the Japanese government in invading a Northeast portion of China. With this revelation Jianqing accused Zhang of treason. In response, he struck her, and with that she demanded a divorce, but instead Zhang gave an ominous response “if you leave me, you’ll be crying the rest of your life.”

Despite this threat she stayed behind in Shanghai, much to the disapproval of her family. They were so unhappy with her that they disowned their own daughter, causing Jianqing to scramble to find a place to live. She found a distant relative not too far from Shanghai. Shortly after moving in she began life as a school teacher, and then as a typist to make ends meet.

It was 1922, and a little production company named “The Mingxing Film Studio” was just getting off the ground and was holding auditions for its first ever feature length production, “An Orphan Rescues His Grandfather.” At the time, it is unlikely anyone knew just how much of a juggernaut “Mingxing” would become. For once the company finally found its footing, around 1925, the production company would dominate the industry until it closed their doors in 1937.

One of the founders of “Mingxing,” Ren Jinpin, met Jianqing through a mutual friend. He was highly impressed by her dignity, grace and charm. He felt the young nineteen-year-old would be perfect for one of the roles for the upcoming film, and asked her to audition.

The role which Jianqing tried out for, and eventually got, was that of the main protagonist in the form of a shao nainai or a ‘young mistress,’ she was to inherit her family’s fortune and showed great class throughout the film.

Since “Mingxing” was just starting out they did not have a studio to film at, the only place they could film was in a barn on a patch of unoccupied land. It was here that Jianqing made her screen debut, and after only a few takes she was offered a contract of 500 yuan per month.

This seemed to be the first happy moment for Jianqing in quite some time. However, as it always seems to do with people, her past kept catching up with her. Her oldest brother, now the head of her family (clan), demanded that she turn down the contract and return home, that way they could find her another man to marry. When Jianqing refused, her brother sued her on the grounds of disrespecting their ancestors, going against family morale’s and rules, and contrary to women’s discipline.

At the time, Jianqing could have been put to death for disobeying the rules of her clan. Which, occurs in the movie I mentioned at the beginning of this post, “Raise the Red Lantern.” One thing that made matters worse for her was that movies had not yet been accepted by the population at large, therefore the contract she signed did not seem to be one of much importance. Although it had been well over ten years since the first female had appeared on screen, it was still seen as a socially unacceptable thing to do. Jianqing came up with a compromise though. Rather than be sent back home, or be put to death. She offered to have her name legally changed, and swore to never let her birth name become public. Her brother accepted these terms and it is through this settlement that the name Wang Hanlun was born.

Wang believed that tigresses were fearless, much like herself, and they had the symbol for ‘king’ written on their foreheads, this is how she came up with her first name. For Hanlun, it turns out she liked the name ‘Helen,’ so she chose one that sounded similar.

It became clear early on that the right choice had been made in casting Hanlun. Her work ethic, determination and maturity gave the character added depth that moved audiences and made her a sensation overnight.

One of the other key aspects that makes Hanlun so memorable is just ho important “An Orphan Rescues His Grandfather” is to Chinese cinema. At the time, cinema in China was still in its infancy and was not being taken seriously. However, with how grand and well received this picture was, everyone began to take notice at the possibilities that film offers. Hanlun stole the show in the film that marks the turning point in Chinese cinema, even if her career had bombed after this one performance she would certainly be long remembered.

As it was though, she had many more stunning performances left in the tank.

Hanlun became the main box office draw for “Mingxing,” appearing in six other films for them (Pitiful Son, Weak Daughter, Discarded Wife, The Soul of Yu Li (1924), Star-Plucking Girl, Newlyweds’ Family, The Person in the Boudoir Room (1925)). In these she played the leading role, generally that of young capable women whose lives were ruined due to the social practices of China. After asking for a raise, and not receiving one, Hanlun accepted an offer from “the Great Wall Studio.” She made three films for them, (Child Laborer, The Movie Actress (1926), A Virtuous Buddhist Daughter-in-law (1927)) but was not paid for any of them because of the financial restrictions the company was going through.

It was in 1929, two years after her final film with “the Great Wall” did Hanlun put together her finest performance as an actress and a director.

Feeling betrayed and determined to make her own money this time, Hanlun formed her own indie film company known as “the Hanlun Film Studio.” She had not aspirations of it growing into a major company, no. Instead, all she wanted was to get her very first picture off the ground and into theaters across China. It was a film that was the culmination of twenty-six years of misfortune. It was passionate, vengeful, touching, but most of all it was genuine. The title of the film is “An Actresses Revenge” where she had her final starring role. Hanlun toured China for over a year promoting the film, and when it finally hit theaters it was a box office smash, grossing more money than any other film she had starred in.

With the profits, she had made from the film she disbanded the company and opened her own beauty parlor.

It appeared she had gone out on top. Or at the very least, she did get one over on the studios that had wronged her.

Her business did very well all throughout the 1930s. It wasn’t until the Japanese invaded did her life come crashing down again. Although she had officially retired from acting she, like many other actors who lived in Shanghai, were forced into doing propaganda movies or radio broadcasts. She refused however. In response to this the government shut her parlor down and to survive Hanlun sold off all her possessions and simply hung on until the war ended in 1945.

After the war ended Hanlun, now forty-two, tried to get back into the acting scene. However, the roles simply were not there for her. Companies either thought she was too old or that she was a relic from the previous China that the new generation wanted to move past. This last statement is perhaps the truest of the two as Hanlun herself once addressed it following her final on screen appearance in “The Life of Wu Xun” (1950):

I came to realize that my best was not good enough. The characters I had played before were of the bourgeoisie or feudal classes, but what was wanted now were new people from the new society. As much as I desired to participate in the building of this new world, their thoughts and emotions were things I just did not understand…

Her performance, though only ten seconds long, was widely panned.

Hanlun lived out the rest of her days in solitude. She never remarried and had no children, by this point in her life almost everyone related to her had become estranged. The only exception was a nephew who would stop by frequently and visit her for hours at a time.

A strong woman, far ahead of her time, and long remembered in the annals of cinema, Wang Hanlun lived a troubled life. In the end, it is said she found happiness, enjoying books and reliving the happier moments of her life.

She died at the age of seventy-five in a Shanghai hospital.

0 notes

Photo

Discovered as a typist by director Mohan Bhavnani, Sulochana (Ruby Myers) rose to fame in the silent cinema of the late 20s making her pair with actor D Billimoria a box office favorite. Films like Typist Girl (1926), Balidaan (1927), Wild Cat of Bombay (1927, where she did 8 roles), Madhuri (1928), Anarkali (1928) and Indira B A (1929) are her most famous silent films. She also did well in the early 30s talkies viz. Madhuri (1932), Indira MA (1934) and Anarkali (1935).

Follow Bollywoodirect #bollywood

#sulochana#ruby myers#mohan bhavnani#typist girl (1926)#wild cat of bombay (1927)#Madhuri (1928)#Anarkali (1928)#Indira BA (1929)#bollywood#bollywoodirect

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remembering Ruby Myers (1907 – 10 October 1983), better known by her stage name Sulochana on her 111th birth anniversary.

Ruby was a silent film actress of Jewish ancestry, hailing from the community of Baghdadi Jews in India.

In her heyday, she was one of the highest paid actresses of her time, when she was paired with Dinshaw Billimoria in Imperial Studios films. In mid-1930 she opened Rubi Pics, a film production house.

She was awarded the 1973 Dada Saheb Phalke Award, India's highest award in cinema for lifetime achievement.

Ruby Myers was born in 1907 in Pune. Chubby, petite and brown-eyed, the self-named Sulochana was among the early Eurasian female stars of Indian Cinema.

She was working as a telephone operator when she was approached by Mohan Bhavnani of Kohinoor Film Company to work in films. Though excited by the offer, she turned him down as acting was regarded as quite a dubious profession for women those days. However Bhavnani persisted with his offer and she finally agreed, despite having no knowledge of acting whatsoever. She became a star under Bhavnani's direction at Kohinoor before moving on to the Imperial Film Company where she became the highest paid movie star in the country.

Among her popular films were Typist Girl (1926), Balidaan (1927) and Wildcat of Bombay (1927) where she essayed eight roles including a gardener, a policeman, a Hyderabadi gentleman, a street urchin, a banana seller and a European blonde.

Three romantic super hits in 1928 - 29 with director R.S. Chaudhari - Madhuri (1928), Anarkali (1928) and Indira B.A. (1929) saw her at her peak of fame in the silent film era. In fact so widespread was her fame that when a short film on Mahatma Gandhi inaugurating a khadi exhibition was shown, alongside it was added a hugely popular dance of Sulochana's from Madhuri, synchronized with sound effects.

With the coming of sound, Sulochana suddenly found a lull in her career, as it now required an actor to be proficient in Hindustani. Taking a year off to learn the language, she made a grand comeback with the talkie version of Madhuri (1932).

Further talkie versions of her silent hits followed and with Indira (now an) M.A. (1934), Anarkali (1935) and Bombay ki Billi (1936). Sulochana was back with a bang. She was drawing a salary of Rs 5000 per month, she had the sleekest of cars (Chevrolet 1935) and one of the biggest heroes of the silent era, D. Billimoria, as her lover with whom she worked exclusively between 1933 and 1939. They were an extremely popular pair - his John Barrymore-style opposite her Oriental 'Queen of Romance' image.

But once their love story ended so did their careers. Sulochana left Imperial to find few offers forthcoming. Newer, younger and more proficient actresses had entered the scene. She tried making a comeback with character roles but even these were few.

However, she still had the power to excite controversy. In 1947, Morarji Desai banned the Dilip Kumar - Noor Jehan starrer, Jugnu, because it showed such a morally reprehensible act as an aging fellow professor falling for Sulochana's vintage charms.

In 1953, she acted in her third Anarkali, but this time in a supporting role as Salim's mother.

She died in 1983 in her flat in Mumbai.

Her films include Cinema Queen (1926), Typist Girl (1926), Balidaan (1927), Wild Cat of Bombay, in which she played eight different characters, which was remade as Bambai Ki Billi (1936); Madhuri (1928), which was re-released with sound in 1932; Anarkali (1928), remade in 1945; Indira BA (1929); Heer Ranjah (1929), and many others, such as Baaz (1953).

Sulochana established her own film studio, Rubi Pics, in the mid-1930s. She received the Dada Saheb Phalke Award in 1973 for her lifetime contribution to Indian cinema. Ismail Merchant paid homage to her in Mahatma and the Bad Boy (1974).

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remembering Chandulal Shah the famous director, producer, screenwriter of Indian films and the founder of Ranjit Studios, on his 120th birth anniversary.

Amarchand Shroff, a friend of Shah, who was with the Laxmi Film Company, brought him to Kohinoor Film Company where he first came into contact with Gohar, a contact that eventually developed into both a personal and professional relationship.

The first film independently directed by him at Kohinoor was Typist Girl (1926) starring Sulochana and Gohar which was made in 17 days. The film did extremely well at the box-office leading Shah to direct another five films for the studio all featuring Gohar. Of these, the most famous were Gunsundari (1927).

In 1929 Chandulal Shah founded Ranjit Studios at Bombay, Maharashtra. It produced films between 1929 and mid-1970s. The company began production of silent films in 1929 under the banner Ranjit Film Company and by 1932 had made 39 pictures, most of them social dramas. The company changed its name to Ranjit Movietone in 1932 and during the 1930s produced numerous successful talkies at the rate of about six a year. At this time, the studio employed around 300 actors, technicians and other employees. With the advent of sound, Ranjit Film Company became Ranjit Movietone.

Besides Filmmaking, Chandulal Shah also devoted a lot of time to the organisational work of the Indian Film Industry. Both the Silver Jubilee (1939) and the Golden Jubilee of the Indian film Industry (1963) were celebrated under his guidance. He was the first president of The Film Federation of India formed in 1951 and even led an Indian delegation to Hollywood the following year.

Bollywoodirect बॉलीवुड डायरेक्ट Bollywoodirect

0 notes