#Triassic Tusk Records

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

youtube

WATCH: CHECK MASSES - DRIPN ANGEL (Triassic Tusk Records)

There i was traulling the inbox for something fresh and stand-out, Edinburgh’s Check Masses expertly combine their influences and tastes to create a sound that stands out in a monsoon and makes you pay attention and grab a brolli.

Three Scottish music innovators have emerged from the nocturnal shadows as CHECK MASSES with their debut single “DRIPN ANGEL” — an evocative trawl through psychedelic soul, widescreen hip-hop and blues mythology.

Separately, Vic Galloway, Saleem Andrew McGroarty and ‘Philly’ Angelo Collins have helped shape the sound of Edinburgh through underground gigs, club culture and broadcasting. They pull on their different influences in CHECK MASSES, reflecting facets of the ever-evolving city - both the birthplace of Scottish punk, and the home of Young Fathers.

Their first single “DRIPN ANGEL” is threaded with dusk-to-dawn tension, channeling the dark heart and desperation of the blues through a modern lens. The trio’s influences weave through the song, from Philly’s cracked soul melodies and spectral chanting to Andy’s oil drum beats and tinkering electronics, with Galloway’s echoey guitar twangs channelling Morricone and late night Lynchian paranoia.

While he’s a punk at heart, Galloway is a true authority on the diversity of Scottish music, through his 20 years as a BBC presenter and his 2018 book “Rip It Up - The Story of Scottish Pop”, the definitive history since the 1950s. Closer to home, “Songs in the Key of Fife” is his first-hand account of the East coast’s rich musical legacy, informed by playing in various bands with James Yorkston and King Creosote as a key member of the Fence Collective. Philly moved to Scotland from the Seychelles as a kid and has been in bands since the mid-90s. After EMI signed him for an album he resisted the label’s attempts to nudge him into an R&B corner. But with the help of McGroarty as executive producer, he later explored an acoustic path with psychedelic post-rock shades on his self-released debut “Kings and Queens”, cut from the shelved EMI tracks. Andy has been an integral figure in Edinburgh’s nightlife for years, starting the capital’s first hip-hop club The Big Payback with Neil Spence in 1990, and playing at some of the city’s seminal clubs, including Lizard Lounge and Chocolate City. He also featured on Sugar Bullet’s, “Demonstrate In Mass (One Nation Under A Dope Mix)”, the first ever recorded Scottish hip-hop track. He currently produces under the name Sound Signals. "DRIPN ANGEL” is the first song CHECK MASSES wrote, working off Andy’s initial beat and a sample that Philly “connected to straight away”. The lyrics explore the mystical femme-fatale blues archetype. Philly says the words came “very fast, an outpouring… experimenting with unconnected words.'' "The woman in the song is the Devil,” Philly adds. “I’d recently rewatched Angel Heart and was trying to get the atmosphere/desperation and the futility of making a deal with the Devil come alive in song. The blues come from the darkest part of a man's heart, and trust me it’s all heart.” "DRIPN ANGEL” is an inspired, improvised opening shot from the trio, as they trawl through dark themes and make it through the night. "DRIPN ANGEL" is out on 10th January 2020 via Triassic Tusk Records.

The accompanying video nods to lurid Bond title silhouettes and the credits of the cult 70s TV show “Tales of the Unexpected”, reeled out on degrading 8mm film effects, with flashes of surrealism by Edinburgh artist Bernie Reid. Galloway says the trio were inspired by Young Fathers’ early homemade videos, as well as rewatching Edwyn Collins’ “A Girl Like You” and Queens of the Stone Age’s “Go With the Flow”.

"We wanted a lo-fi, psychedelic feel, to capture the claustrophobia and tension in the song,”he says. “We think this is captured with the dancing silhouettes, churchyard gargoyles, album artwork and Philly's yearning vocals all colliding on-screen.”

UPCOMING DATES: 31st January - Voodoo Rooms, Edinburgh

CONNECT: Twitter Facebook Instagram

0 notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion Month #25: Phylum Mollusca – Shelling Out

The exact evolutionary relationships of the main groups of modern molluscs are rather debated, with several different proposed family trees. But one of the main possibilities is that there are two major lineages: the aculiferans and the conchiferans.

Modern conchiferans include slugs and snails, cephalopods, bivalves, tusk shells, and monoplacophorans – all groups that ancestrally have either a single-part shell or a two-part bivalved shell, with some lineages later becoming secondarily shell-less.

The ancestral conchiferans are thought to have been monoplacophoran-like molluscs, limpet-like with a cap-shaped shell, and likely diverged from a common ancestor with the aculiferans around the end of the Ediacaran. (But modern monoplacophorans probably aren't "living fossil" descendants of early Cambrian conchiferans, and may instead be close relatives of cephalopods that have convergently become similar in appearance to their ancestors.)

Some of the earliest conchiferans were the helcionelloids, a lineage of superficially snail-like molluscs with coiled cone-shaped mineralized shells. They appeared in the fossil record at the start of the Cambrian (~540-530 million years ago) and lasted until the early Ordovician (~480 million years ago), and have been found all around the world as components of the "small shelly fauna".

And while they're usually tiny, only a couple of millimeters in size, they may actually represent juveniles or larvae – there's evidence that at least some species grew up into much larger 2cm (0.8") limpet-like adult forms.

Some helcionelloids like Yochelcionella americana had an odd tubular snorkel-like structure growing from their shells. This was probably part of their breathing system, serving as an "exhaust pipe" for the water passing over their gills, and may be an evolutionary link to the siphons or siphuncles of other conchiferans.

About 2mm long (0.08"), this particular species is known from the Forteau Formation in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada (~514 million years ago) and also from similarly-aged deposits in Pennsylvania and Greenland. Other species in the same genus are found worldwide between about 530 and 505 million years ago.

———

In some parts of Yochelcionella americana's range it coexisted with another type of widespread early conchiferan – one of the first known bivalves, Pojetaia runnegari. Around 2mm long (0.08"), it would have lived either on or just under the surface of the seafloor.

It might have been related to a group of modern bivalves called protobranchs, or it may have been part of an early stem lineage with no close living relatives. It already had the basic bivalve body plan in place, with left and right valves, hinges, and shell-closing muscles, but doesn't seem to have had a siphon. Unfortunately it doesn't really give us much insight into the evolutionary origins of the group, and the appearance of the ancestral "proto-bivalves" is still unknown – but the microstructure of Pojetaia's shell may indicate a possible evolutionary link with the helcionelloids.

———

While the helcionelloids superficially resembled snails, it's unclear if they were closely related to actual gastropods.

Fossils that might be true early gastropods first turn up in the mid-to-late Cambrian, with a group called bellerophonts. These molluscs had near-symmetrically coiled shells compared to the helical coiling of most gastropods, and they had quite a long run as a group, lasting all the way until the early Triassic (~249 million years ago).

Strepsodiscus austrinus is known from the Lampazar Formation in Argentina, dating to about 490-485 million years ago at the end of the Cambrian. About 3cm long (1.2"), its shell was very slightly coiled to the left, and it seems to have been a detritivore living on soft seafloor sediments.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion 2021#mollusc#conchifera#yochelcionella#helcionelloida#pojetaia#bivalve#strepsodiscus#bellerophontoidea#gastropod#lophotrochozoa#spiralia#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

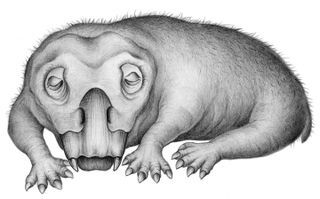

Lystrosaurus

By Jack Wood / Darwin’s Door

Etymology: Shovel reptile

First Described By: Cope, 1870

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Synapsida, Eupelycosauria, Sphenacodontia, Sphenacodontoidea, Therapsida, Eutherapsida, Neotherapsida, Anomodontia, Chainosauria, Dicynodontia, Therochelonia, Bidentalia, Dicynodontoidea, Lystrosauridae

Referred Species: L. curvatus, L. declivis, L. georgi, L. hedini, L. maccaigi, L. murrayi (and several other probably invalid species)

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 253 and 247 million years ago, from the Changhsingian of the Late Permian to the Olenekian of the Early Triassic

Lystrosaurus is mostly known from the Karoo Basin in South Africa, along with the Fremouw Formation in Antarctica, the Panchet Formation in India, and probably Australia in Gondwana, while at least two or more species from Laurasia are known in Russia, China, and Mongolia, giving Lystrosaurus a very broad distribution across much of Pangaea.

Physical Description: Lystrosaurus is pretty much the quintessential dicynodont, but when you get down to it, it’s actually a pretty weird one. The skull is unusually tall and squashed looking, even by dicynodont standards, with an incredibly short snout that drops down very steeply almost right in front of the eyes to the squared-off beak and pointy tusks at the bottom, hence the resemblance to a shovel (although the face of Lystrosaurus is actually surprisingly narrow from the front). In some specimens, the snout drops down almost vertically. The eyes are placed so far forward and up on the skull that they almost look like they’re bugging out of its head, and the nostrils are sat directly below them on the front of the snout. The back region of the skull behind the eyes takes up at least half of the length of the skull and houses massive jaw muscles, giving Lystrosaurus a very strong, snapping bite. Curiously, at least some Lystrosaurus may have had a thickened cornified pad between the eyes, possibly similar to the keratin of the beak, as well as rough bosses over the eyes. These were probably used for display, and may have been surprisingly colourful for what you’d expect from a stem-mammal.

The body of Lystrosaurus is more standard, with a long, tubular trunk, stubby tail and short, squat legs. Overall it was pretty dumpy looking (this is an actual description used in a scientific paper, no joke). This shape has been compared to that of hippos, often to suggest a similar lifestyle, but the strong, semi-upright limbs suggest a more terrestrial lifestyle. The forelimbs of Lystrosaurus are very well developed, and its hands and feet are broad with spread toes and large, flat claws, well suited for digging. It was somewhere around the size of the pig, give or take how big you think a pig is, but since Lystrosaurus sizes vary between small to over a metre you’re probably in the ballpark. The integument of Lystrosaurus, and indeed almost all stem-mammals, is poorly understood, and they have been speculated to be scaley, hairy, or just covered in naked skin. However, as-yet unpublished Lystrosaurus mummies from South Africa suggest that Lystrosaurus had hairless, scaleless skin studded with bumpy tubercles. But until we know more about these specimens, we can’t be certain how this would look. Lystrosaurus may also have been sexually dimorphic, with presumed males having more prominent bosses and robuster skulls. Lystrosaurus grew fast for dicynodonts, with rapid continuous growth as juveniles, slowing down as sub-adults with periods of little to no growth, and slowing considerably as they reached adulthood.

Diet: Lystrosaurus was a herbivore, grazing mostly on tough, low-lying drought-resistant plants like horsetails and seed ferns. However, it is also possible that it ate fungi and even bits of animal matter too while rooting around in the earth. Like other dicynodonts, Lystrosaurus chewed its food with a backwards motion of the jaw using its massive jaw muscles, making it an efficient grazer, and its short skull and jaws made it extra effective at snapping through tough stems.

Behavior: Lystrosaurus has often been described as amphibious, living like a hippopotamus, based on its supposedly high set eyes and downward facing jaws. However, there is actually little evidence to support this mode of life, and in reality the evidence is more in favour of a mostly terrestrial lifestyle, no more aquatic than any other dicynodont. Bonebeds of Lystrosaurus tells us that they were social animals that at least sometimes congregated together in similar age groups, at least as juveniles and subadults, possibly for protection during extreme temperature swings. For a long time Lystrosaurus was speculated to have been a burrower, and this was confirmed later by the discovery of not only Lystrosaurus burrows, but even burrows with the skeleton of its owner still inside. Burrowing was evidently a successful strategy for surviving the Great Dying, as many other Early Triassic survivors, like Thrinaxodon and Procolophon, were also burrowers. In fact, it’s even possible that Lystrosaurus acted as a sort of ecosystem engineer, modifying the environment and providing other species with refugiums in hard times that allowed them to pull through alongside it!

Ecosystem: In the earliest Triassic, Lystrosaurus was famously one of the most abundant vertebrates on the planet. It is regarded as a disaster taxon, a species that survives and proliferates in the ecological vacuum left after a mass extinction. Because the continents were joined together in Pangaea, much of the world’s fauna and flora was broadly similar. This is especially so in Gondwana, where much of the therapsid, reptile and amphibian fauna was shared. Here Lystrosaurus co-existed with various other therapsids, including two other surviving dicynodonts Myosaurus and Kombuisia, as well as the small cynodonts Thrinaxodon and Galesaurus, and various therocephalians such as Ericiolacerta, Tetracyndon, Ictidosuchus and the 1.5 metre long predatory Moschorhinus, one of the few predators that could prey upon Lystrosaurus in the Early Triassic. Archosauromorphs had also survived here, most notably the predatory proterosuchids, as well as the small Prolacerta and the larger, exclusively Antarctic Antarctax. Other reptiles includes the parareptile Procolophon, and the enigmatic diapsid Palacrodon, while the closely related (and relatively terrestrial as it turns out) temnospondyls Lydekkerina and Cryobatrachus cruised the waterways of South Africa and Antarctica, respectively. Similar fossils are known from India as well.

Prior to the P-Tr Extinction, in the time of L. maccaigi, South Africa was still relatively wet and lush with vegetated floodplains of trees and shrubs, including the famous Glossopterus seed ferns that L. maccaigi may have specialised in feeding on. However, this environment was already changing as the P-Tr Extinction took course, and was already low in biodiversity. L. maccaigi would have coexisted with other dicynodonts, including the lystrosaurid Kwazulusaurus, larger Daptocephalus, Oudenodon, Pelanomodon, and Dinanomodon, and little Thliptosaurus. Predatory therocephalians were around too, namely Promoschorhinus and Moschorhinus itself, which was another P-Tr survivor like Lystrosaurus. Most others however would be lost to the Great Dying, as the Karoo gradually dried out until it was transformed into a hot, arid plain with sprawling braided rivers, little vegetation and seasonally extreme temperatures that was prone to flash floods and cold snaps. To give a clear picture of how arid it was, it’s speculated that so many Lystrosaurus skeletons are found partially articulated and not broken apart like so many other Karoo fossils is because their carcasses were dessicated into mummies that held them together before they were eventually buried whenever it actually rained.

Lystrosaurus may have been pre-adapted to such conditions, however, as its downturned jaws would have been well-suited to grazing on low-growing drought-resistant plants, such as horsetails, as well as for Dicroidium seed ferns that would soon become the dominant Triassic flora. The Fremouw Formation in Antarctica records a more diverse range of seed ferns, cycads, horsetails and even fungi, all of which may have sustained Lystrosaurus. The climate at these high latitudes was milder, but also would mean they would have experienced months of darkness during the polar winters, even if it wasn’t cold.

Other: Lystrosaurus fossils were pivotal in proving Alfred Wegner’s theory of plate tectonics, as they had been found on various continents around the globe, along with other similarly aged fossils, indicating that the continents had once been much closer together and connected as one landmass. Their fossils are famously ludicrously abundant in the Karoo basin, making one it one of the best represented dicynodonts known, and probably of any stem-mammal. In fact, their abundance is so characteristic of the Early Triassic beds of the Karoo that they lend it its name, the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone. Lystrosaurus is sometimes regarded as one of the most successful tetrapods of all time, due to how widespread and populous it was. Case in point, 73% of known vertebrate fossils from the Early Triassic of South Africa are of Lystrosaurus. It’s a prime example of how a disaster taxon with the right pre-adaptations can flourish in the immediate aftermath of a mass extinction, and help to re-establish biotic communities during the recovery of global ecosystems. Not bad for a pudgy, dumpy little herbivore with a squashed up face.

Species Differences: To be frank, and I’m sure most synapsid workers won’t mind me saying this, the majority of stem-mammal taxonomy, including Lystrosaurus, is heavily biased towards their skulls. So much so that the majority of Lystrosaurus species were named based solely on slight variations between their skulls and so consequently were massively oversplit. Thankfully this is being rectified with more thorough, dedicated examinations of Lystrosaurus specimens, and so far the Gondwanan species of Lystrosaurus in the Karoo are the best studied. Four species from there are now recognised, and by and by they’re all still pretty samey looking, superficially. These four species have been recognised as sequentially spanning across the Late Permian and into the Early Triassic, and so can also be distinguished by when they each lived.

L. maccaigi is both the largest and the oldest species, and is the only one known exclusively from the Permian (although a single skull from Antarctica may or may not bring it into the earliest Triassic, assuming the rocks weren’t really Permian all along). It’s recognised for having remarkably well-developed bosses both in front and behind the eyes, giving it very distinctive looking “brows”, and the eyes themselves are characteristically large and placed high on the skull, facing somewhat more forwards and upwards than other species. The snout also drops down especially sharply (almost vertically in some), with a straight edge and ridge down the centre. As well as being the largest species, L. maccaigi was also the rarest, and both of these factors may have contributed to its extinction in the P-Tr.

The smaller L. curvatus is also known from the Permian, but unlike L. maccaigi it is known to have actually crossed the boundary into the earliest Triassic, however it died out shortly afterwards. L. curvatus is one of the least ornamented species of Lystrosaurus, with very reduced or no ridges and bosses on the face and over the eyes, although the largest individuals may have them, including small nasal bosses. L. curvatus also has some of the proportionally largest eyes of all Lystrosaurus, as well as a more gently curved snout than the others. Probably the cutest looking.

L. declivis and L. murrayi are exclusively found in the Triassic, and interestingly they are both consistently smaller than either Permian species. This is believed to be a response to the harsh conditions of the Permian Extinction and Early Triassic, as Lystrosaurus were growing faster and reaching reproductive maturity at smaller sizes and younger ages to combat shorter life expectancies. They are both fairly similar in appearance, each with short, slightly curved, somewhat angular snouts, although L. murrayi has a shorter snout only as long as the roof of the skull, whereas L. declivis has a snout that extends further down. L. declivis also has a pair of bosses in front of the eyes and a distinct ridge running between them, as well as a ridge running down the beak, all features missing from L. murrayi. Both species have a patch of grooves between the eyes on the roof of the skull, possibly supporting a sheet of keratin not seen in L. maccaigi or L. curvatus.

However, this apparent timeline does not mean there was a linear progression between these species. In fact, L. maccaigi and L. curvatus are the most derived species of Lystrosaurus, while L. declivis and L. murrayi are each more primitive than the last! Perhaps the more primitive species were able to survive by being less specialised and growing smaller. Also, this means that their ancestors had already split off during the Permian before L. maccaigi even evolved, so Gondwanan Lystrosaurus did not survive the P-Tr Extinction in just one species, but at least three! L. curvatus and L. murrayi are also both known from Triassic Antarctica, and L. murrayi is further known from India, implying quite a broad Gondwanan distribution—although given the three continents’ close proximity in Pangaea this may not be surprising.

The differences between the Laurasian species are less clear, and while various species have been named from China, it is possible that they belong to only a single species, L. hedini. L. hedini is another species known from the Permian to have crossed into the Early Triassic, and has also been found in Mongolia.

L. georgi from the Triassic of Russia is a bit of an enigma, unlike virtually every other Lystrosaurus species its skeleton is better known than its skull. This is great for understanding how the body of Lystrosaurus functioned but less so for its taxonomy. In any case, L. georgi is still pretty biogeographically distinct from other Lystrosaurus species, so it has merit. L. georgi was initially regarded as similar to the Gondwanan L. curvatus, but preliminary analyses of other Laurasian Lystrosaurus suggest they are a taxonomically distinct grouping of Lystrosaurus species, which presumably includes L. georgi.

~ By Scott Reid

Sources under the cut

Benoit, J., Angielczyk, K.D., Miyamae, J.A., Manger, P., Fernandez, V. and Rubidge, B., 2018. Evolution of facial innervation in anomodont therapsids (Synapsida): Insights from X‐ray computerized microtomography. Journal of morphology, 279(5), pp.673-701

Botha-Brink, J. (2017). Burrowing in Lystrosaurus: Preadaptation to a postextinction environment? Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 37(5), e1365080

Botha-Brink, J., Codron, D., Huttenlocker, A.K., Angielczyk, K.D. and Ruta, M., 2016. Breeding young as a survival strategy during Earth’s greatest mass extinction. Scientific Reports, 6, p.24053

Botha, J. & Smith, R.M.H. (2005). "Lystrosaurus species composition across the Permo–Triassic boundary in the Karoo Basin of South Africa". Lethaia. 40 (2): 125–137

Brink, A. S. (1951). On the genus Lystrosaurus Cope. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa, 33(1), 107–120

Broom, R. (1903b). On the structure of the shoulder girdle in Lystrosaurus. Annals of the South African Museum, 4, 139–141

Camp, J. A. 2010. Morphological variation and disparity in Lystrosaurus (Therapsida: Dicynodontia). M.S. thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, 141 pp

Cluver, M. A. (1971). The cranial morphology of the dicynodont genus Lystrosaurus. Annals of the South African Museum, 56, 155–274

Colbert, E. H. 1974. Lystrosaurus from Antarctica. American Museum Novitates 2535:1-4

Cosgriff, J.W., Hammer, W.R. and Ryan, W.J., 1982. The Pangaean reptile, Lystrosaurus maccaigi, in the Lower Triassic of Antarctica. Journal of Paleontology, pp.371-385

Das, D.P. and Gupta, A., 2012. New cynodont record from the lower Triassic Panchet Formation, Damodar valley. Journal of the Geological Society of India, 79(2), pp.175-180

Grine, F. E., Forster, C. A., Cluver, M. A., & Georgi, J. A. (2006). Cranial variability, ontogeny, and taxonomy of Lystrosaurus from the Karoo Basin of South Africa. In M. T. Carrano, T. J. Gaudin, R. W. Blob & J. R. Wible (Eds.), Amniote paleobiology: Perspectives on the evolution of mammals, birds, and reptiles. (pp. 432–503). Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Groenewald, G. H. (1991). Burrow casts from the Lystrosaurus-Procolophon Assemblage Zone, Karoo Sequence, South Africa. Koedoe, 34(1), 13–22

Gow, C.E. 1999. The Triassic reptile Palacrodon browni Broom, synonymy and a new specimen. Palaeontologia Africana 35: 21–23.

Gubin, Y.M. and Sinitza, S.M., 1993. Triassic terrestrial tetrapods of Mongolia and the geological structure of the Sain-Sar-Bulak locality. The Nonmarine Triassic, 3, pp.169-170

Jasinoski, S.C., Rayfield, E.J. and Chinsamy, A., 2009. Comparative feeding biomechanics of Lystrosaurus and the generalized dicynodont Oudenodon. The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology, 292(6), pp.862-874

Jun, L.I.U., JinLing, L.I. and CHENG, Z., 2002. THE LYSTROSAURUS FOSSILS FROM XINJIANG AND THEIR BEARING ON THE TERRESTRIAL PERMIAN TRIASSIC BOUNDARY. Vertebrata Pal Asiatica, 40(4), pp.267-275

King, G. M., & Cluver, M. A. (1991). The aquatic Lystrosaurus: An alternative lifestyle. Historical Biology, 4, 323–341

Li, J. (1988). Lystrosaurs of Xinjiang, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 26 (4): 241–249

Modesto, S. P., & Botha-Brink, J. (2010). A burrow cast with Lystrosaurus skeletal remains from the Lower Triassic of South Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 25, 274–281

Ray, S. 2005. Lystrosaurus (Therapsida, Dicynodontia) from India: taxonomy, relative growth and cranial dimorphism. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 3:203–221

Ray, S., Chinsamy, A., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2005). Lystrosaurus murrayi (Therapsida, Dicynodontia): Bone histology, growth, and lifestyle adaptations. Palaeontology, 48, 1169–1185

Retallack, G.J., 1996. Early Triassic therapsid footprints from the Sydney basin, Australia. Alcheringa, 20(4), pp.301-314

Rozefelds, A.C., Warren, A., Whitfield, A. and Bull, S., 2011. New evidence of large Permo-Triassic dicynodonts (Synapsida) from Australia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 31(5), pp.1158-1162

Smith RMH, Rubidge BS, van der Walt M. 2011. Therapsid biodiversity patterns and palaeoenvironments of the Karoo Basin, South Africa. In Forerunners of mammals (ed. A ChinsamyTuran), pp. 31 – 64. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press

Surkov, M.V., Kalandadze, N.N., and Benton, M.J. (June 2005). "Lystrosaurus georgi, a dicynodont from the Lower Triassic of Russia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 402–413

Taylor, E.L.; Taylor, T.N. (1993). "Fossil tree rings and paleoclimate from the Triassic of Antarctica". In Lucas, S.G. and Morales, M. (eds.) (eds.). The Nonmarine Triassic. Albuquerque: The New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. pp. 453–455

Viglietti, P.A., Smith, R.M. and Compton, J.S., 2013. Origin and palaeoenvironmental significance of Lystrosaurus bonebeds in the earliest Triassic Karoo Basin, South Africa. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 392, pp.9-21

Viglietti, P.A.; Smith, R.M.H.; Rubidge, B.S. (2018). "Changing palaeoenvironments and tetrapod populations in the Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone (Karoo Basin, South Africa) indicate early onset of the Permo-Triassic mass extinction". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 138: 102–111

Watson, D. M. S. (1912). The skeleton of Lystrosaurus. Records of the Albany Museum, 2, 287–299

Watson, D. M. S. (1913). The limbs of Lystrosaurus. Geological Magazine, 10(06), 256–258

#lystrosaurus#dicynodont#synapsid#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

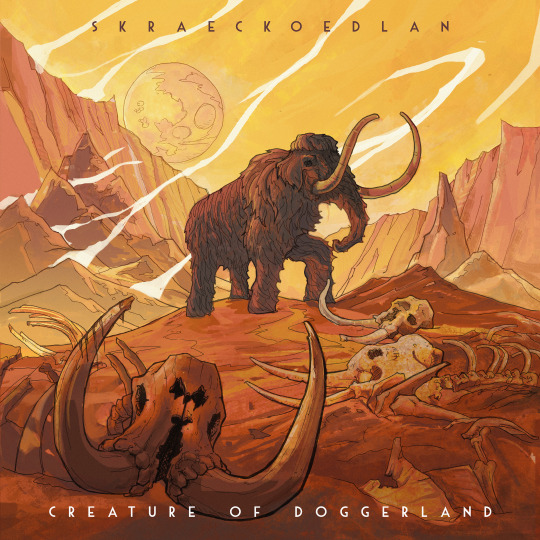

Swedish Sci-Fi Fuzz Freaks Skraeckoedlan Drop Third Single Ahead of ‘Earth’

~Doomed & Stoned Debuts~

Hot damn! This put me in a really good mood today. It's so good to hear new tunes from SKRAECKOEDLAN, the fuzz-drenched progressive stoner-doom outfit from Norrköping -- a city nestled in northeastern Sweden, about an hour-and-a-half's drive from Stockholm. Heavily rooted in the distinctives of their native soil, this three-piece sings entirely in Swedish, presenting a bit of a challenge to English-speakers, but no less an adventure in uncovering the backstory and interpretation of their songs...for nothing is at it seems.

A longtime favorite of Doomed & Stoned readers, the band has been wowing us with some of the most exciting songwriting on God's green earth since 2009. Now, a decade of dedication to anything is an accomplishment, but for a band with talents so laser-focused on their craft as Robert Lamu (guitar, vocals), Henrik Grüttner (guitars, vocals), and Martin Larsson (drums), it's a god damned milestone. The band, aptly named after an enormous prehistoric monster, has treated us to a pair of hefty long-plays already and now they brace for their third, 'Eorþe' (2019) on the esteemed Fuzzorama Records label.

The new record is a dense Lovecraftian tale by science fiction author Nils Håkansson, which he in fact wrote with the intention of having Skraeckoedlan bring to life over the course of these eight songs. It's a remarkable collaboration that is not only literary and musical, but visual, as well. The band worked once again with longtime artist Johan Leion to aid us in unlocking these mysteries of the faded past.

Today, Doomed & Stoned gives you a first listen to "Tentakler & Betar," which catches the narrative of Eorþe as it is nearing its end. The song is characterized by urgent beats, soaring vocal harmonies, weird effects, arpeggios that crawl like agitated spiders, and spirited riffs that fly and sing like the fowls of the air. Let me not fail to mention, too, that the sound is absolutely brilliant. The band tells us this about the number:

"This, the penultimate track of the album, takes us down into the darkness of the earth, as well as the mind. It explores what is left at journey's end and what to do when ambitions have been reached. Standing face to face with your obsessions, where do you go? As the cosmic clock relentlessly ticks, nothing will remain but tentacles and tusks."

February 15th is the date to watch for Skraeckoedlan's triumphant new album. It can be pre-ordered on some delicious looking vinyl variants here.

Give ear...

Some Buzz

Heavy riff power trio Skraeckoedlan are telling tales draped in metaphor. Fuzzy stories buried in melody are cloned into a one of a kind copy of an otherwise eradicated species. Previously found only in Sweden, this cold blooded lizard have once again started to walk the planet that we know as earth. The extinct is no longer a part of the past. Skraeckoedlan is the best living biological attraction, made so astounding that they capture the imagination of the entire planet.

The dinosaurs are believed to have made their first footprints on our earthen floor some 240 million years ago, during what is now known as the Triassic period. Indisputable behemoths and apex predators amongst them, they wandered freely and soared sovereign, ever evolving as the impending Jurassic and Cretaceous eras unfolded. Then, 65 million years ago, it stopped. Be it by asteroid or volcano, the dinosaurs’ fate became one shared with most species ever to inhabit our pale blue dot, extinction.

While Skraeckoedlan translates into something like dinosaur, an analogy better drawn is perhaps one to the great lizards’ descendants, the birds. In their flight there is a, quite literal, escapism to be found. A vital ingredient, encapsulating the bands very being. Although escape, it should be said, not necessarily in the sense of shying away but rather as a recipe for observation and introspection. A kind of fleeing of everyday worries in benefit of larger and hopefully more profound queries A bird’s-eye view, if you will.

"A prelude to the end. The moments of bliss before the imminent doom. We have journeyed to the place where it all unfolds, where the unseen rests and the secrets of the past lay buried. Here we too will become shrouded in mystery, riddles to be solved by those not yet granted a time and place in existence. Whatever the answers, one naked truth stands absolute. None shall leave the Ivory Halls."

Quite a few million years later than their reptilian namesakes, Skraeckoedlan is leaving their own footprints in earth’s soil, albeit not as physically grand. Their self-proclaimed fuzz-science fiction rock is an homage to the riff, vehemently echoing throughout the ages like that of a gargantuan Brachiosaurus striding freely. Equal in weight to the deafening heaviness of a Skraeckoedlan melody, these long-necked colossals further possess in their very defining feature the weapon needed for a complete experience of such melodies. Although strong neck or not, once in concert heads will, regardless of intent, be moving along.

Through their natively sung lyrics Skraeckoedlan invites us to partake in a world of cosmic awe inhabited by mythological beings and prehistoric beasts, like the immense havoc wreaking reptilian awakening from its slumber in the polar ice caps, featured on the debut full-length Äppelträdet (The Apple Tree), or the reclusive great ape Gigantos, solemnly wandering his mountain as one of several entities on the follow-up, Sagor (Tales). Against backdrops like these, underlying themes of the aforementioned big picture-nature are being explored, much in the spirit of, and hugely inspired by, great minds such as Alan Watts and Carl Sagan, fantastic creatures in their own respective rights.

"This song is, more than a part of the concept that is Eorþe, a story about life and the feelings of utter hopelessness our seeming oddity of an existence can often give rise to. It is a song about letting go and leaving behind. It’s about shattering the societal mirror and its reflection of illusionary demands and expectations, leaving your unhindered gaze looking ahead, to where your true calling lies. In short, it is a song about becoming truly free."

Formed in the city of Norrköping in 2009, Skraeckoedlan -- a reference to ‘Godzilla’ in Swedish -- are one of the most ambitious, original and multidimensional bands to emerge from Scandinavia in recent years.

Live shows with the likes of Orange Goblin, Kylesa, Greenleaf and other giants of the genre followed in the wake of Äppelträdet’s success and in 2015, with production underway on their follow-up album Sagor (Translated; ‘Tales’) Skraeckoedlan worked with a number of acclaimed producers including Niklas Berglöf (Ghost, Den Svenska Björnstammen) and Daniel Bergstrand (Meshuggah, In Flames, El Caco).

It wasn’t however until they met producer and technician Erik Berglund that they really found what was missing. Lifting the band to entirely new levels of musicianship, under his tutelage the creative process for Sagor not only left the band with an album they were immensely proud of, but one that sat deservedly at number two in the national Swedish vinyl sales chart in August of 2015.

"This song depicts the now submerged Doggerland as seen from the perspective of one of the mammoths who the continent used to house. In fact, we see through the eyes of Doggerland’s very last mammoth as its time amongst the living draws to a close. We occupy its head as thoughts of death and liberation mixes in a flurry of emotion and contemplation. Its destiny shared with the land upon which it walks, our traveler of tusk and wool journeys towards its final resting place while the North Sea rises ever higher, soon to swallow it all."

Like Galactus-in-reverse, their talent for constructing new worlds from the building blocks of heavy psychedelia and progressive rock is simply awe inspiring, and this February will see the release of their most accomplished vision yet: Eorþe (translated, "Earth").

In collaboration with sci-fi author Nils Håkansson who wrote the story behind the album specifically for Skraeckoedlan, Eorþe is set in the 1920s amid a mystery heavy with Lovecraftian influence and philosophical nuances. As the band explains, “This is by far our most ambitious work of art yet. It’s been a real challenge to do someone else’s story justice whilst making the songs cohesive as well as standing strong on their own. It took a lot of effort, but we’ve done just that.”

Having loyally served as heralds to Nordic folklore and science fiction since their inception, following the release of their early EPs in 2010 the band gained the kind of attention that could only lead on to the creation of a much-admired debut album in Äppelträdet (2011, translated; ‘The Apple Tree’) produced by Oskar Cedermalm from the legendary fuzz band Truckfighters.

Earth by Skraekoedlan

Heading into 2019 with the help of Fuzzorama Records, Skraeckoedlan steer a course to Eorþe, their first album in over three years and undoubtedly their most progressive. With the big metal riffs of ‘Kung Mammut’ riding shotgun alongside the more introspective and explorative moments of songs like ‘Mammutkungens Barn’ and ‘Angra Mainyu’, the trio have cut a definitive and spellbinding record of light and dark.

In addition to the CD and standard vinyl editions, Eorþe will also come in a limited-edition box set which sees the album split across two gatefold vinyl records: Earth: Above and Earth: Below. The set will come packed with pieces of merchandise that revolve around the story and feature alternative artwork.

Follow The Band

Get Their Music

#D&S Debuts#Skraeckoedlan#Norrköping#Sweden#Doom#Metal#Progressive Rock#Stoner Rock#Fuzz#Fuzzorama Records#HeavyBest19#Doomed & Stoned

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today India News Seussian beast survived the Triassic by taking lots of naps - Live Science

Today India News Seussian beast survived the Triassic by taking lots of naps – Live Science

Today India News

Home

News

An illustration of a Lystrosaurus in a torpor state.

(Image: © Crystal Shin)

Some 250 million years ago, a Seussian-looking beast with clawed digits, a turtle-like beak and two tusks may have survived Antarctica’s chilly winters not by fruitlessly foraging for food, but by curling up into a sleep-like state, meaning it may be the oldest animal on record to hibernate

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

This weird creature is the first we know of that hibernated - 250 million years ago

https://sciencespies.com/nature/this-weird-creature-is-the-first-we-know-of-that-hibernated-250-million-years-ago/

This weird creature is the first we know of that hibernated - 250 million years ago

Animals have been hibernating for a long, long time, a new study shows. Researchers have analysed 250 million-year-old fossils and found evidence that the pig-sized mammal relation, a genus called Lystrosaurus, hibernated much like bears and bats do today.

Finding signs of shifts in metabolism rates in fossils is just about impossible under normal conditions – but the stout, four-legged Lystrosaurus had a pair of tusks that grew continuously during its life, leaving behind a record of activity not dissimilar to tree rings in a trunk.

By comparing cross-sections of tusks from six Antarctic Lystrosaurus to cross-sections of tusks from four Lystrosaurus from South Africa, the researchers were able to find periods of less growth and greater stress that were exclusive to the Antarctica samples.

How Lystrosaurus may have looked while hibernating. (Crystal Shin)

The marks match up with similar depositions in the teeth of modern day animals that hibernate at certain points during the year. It’s not definitive proof that Lystrosaurus hibernated, but it’s the oldest evidence of it we’ve found to date.

“Animals that live at or near the poles have always had to cope with the more extreme environments present there,” says vertebrate palaeontologist Megan Whitney, from Harvard University. “These preliminary findings indicate that entering into a hibernation-like state is not a relatively new type of adaptation. It is an ancient one.”

The hibernation state, or torpor, may well have been essential for animals living near the South Pole at the time. Though the region was much warmer in the Triassic period, there would still have been big seasonal variations in the number of daylight hours.

It’s very possible that Lystrosaurus wasn’t the only hibernating animal of the time, and some of the dinosaurs that came afterwards may well have hibernated too. The problem is that most species of the time didn’t have continuously growing tusks or even teeth.

“To see the specific signs of stress and strain brought on by hibernation, you need to look at something that can fossilise and was growing continuously during the animal’s life,” says biologist Christian Sidor, from the University of Washington. “Many animals don’t have that, but luckily Lystrosaurus did.”

There’s plenty that this could teach us about the evolutionary history of species, lending support to the idea that a flexible physiology – being able to adapt bodily functions to suit the seasons – may be vital to surviving periods of mass extinction.

Scientists continue to discover more about how hibernation works and how it can be triggered in animals. If we can figure out how to get the same biological trick working in humans, it might give us new ways of fighting disease.

Further studies will be able to look in more detail at the question of whether or not the Lystrosaurus was able to enter a deep state of torpor, but this new analysis is already drawing some interesting parallels that span hundreds of millions of years.

“Cold-blooded animals often shut down their metabolism entirely during a tough season, but many endothermic or warm-blooded animals that hibernate frequently reactivate their metabolism during the hibernation period,” says Whitney.

“What we observed in the Antarctic Lystrosaurus tusks fits a pattern of small metabolic reactivation events during a period of stress, which is most similar to what we see in warm-blooded hibernators today.”

The research has been published in Communications Biology.

#Nature

0 notes

Photo

Episode 31 of 46-30, featuring music by Callum Easter, Josephine Foster, Alemayno Eshintay, Myriam Gendron, Desiree Cannon, Black Allan Barker and plenty more. Hosted by James Yorkston and Stephen Marshall of Triassic Tusk Records.  https://anchor.fm/46-30/episodes/46-30-31-e45r17 … (at Cellardyke) https://www.instagram.com/p/ByANUfLnUqf/?igshid=qxs5qxtpvb5

0 notes

Text

Seussian beast survived the Triassic by taking lots of naps

Seussian beast survived the Triassic by taking lots of naps

[ad_1]

Some 250 million years ago, a Seussian-looking beast with clawed digits, a turtle-like beak and two tusks may have survived Antarctica’s chilly winters not by fruitlessly foraging for food, but by curling up into a sleep-like state, meaning it may be the oldest animal on record to hibernate, a new study finds.

Analysis of this Triassic vertebrate’s ever-growing tusks revealed that it may…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

60-year-old paleontological mystery of a 'phantom' dicynodont -- ScienceDaily

Visit Now - https://zeroviral.com/60-year-old-paleontological-mystery-of-a-phantom-dicynodont-sciencedaily/

60-year-old paleontological mystery of a 'phantom' dicynodont -- ScienceDaily

A new study has re-discovered fossil collections from a 19th century hermit that validate ‘phantom’ fossil footprints collected in the 1950s showing dicynodonts coexisting with dinosaurs.

Before the dinosaurs, around 260 million years ago, a group of early mammal relatives called dicynodonts were the most abundant vertebrate land animals. These bizarre plant-eaters with tusks and turtle-like beaks were thought to have gone extinct by the Late Triassic Period, 210 million years ago, when dinosaurs first started to proliferate. However, in the 1950s, suspiciously dicynodont-like footprints were found alongside dinosaur prints in southern Africa, suggesting the presence of a late-surviving phantom dicynodont unknown in the skeletal record. These “phantom” prints were so out-of-place that they were disregarded as evidence for dicynodont survival by paleontologists. A new study has re-discovered fossil collections from a 19th century hermit that validate these “phantom” prints and show that dicynodonts coexisted with early plant-eating dinosaurs. While this research enhances our knowledge of ancient ecosystems, it also emphasizes the often-overlooked importance of trace fossils, like footprints, and the work of amateur scientists.

“Although we tend to think of paleontological discoveries coming from new field work, many of our most important conclusions come from specimens already in museums,” says Dr. Christian Kammerer, Research Curator of Paleontology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and author of the new study.

The re-discovered fossils that solved this mystery were originally collected in South Africa in the 1870s by Alfred “Gogga” Brown. Brown was an amateur paleontologist and hermit who spent years trying, with little success, to interest European researchers in his discoveries. Brown had shipped these specimens to the Natural History Museum in Vienna in 1876, where they were deposited in the museum’s collection but never described.

“I knew the Brown collections in Vienna were largely unstudied, but there was general agreement that his Late Triassic collections were made up only of dinosaur fossils. To my great surprise, I immediately noticed clear dicynodont jaw and arm bones among these supposed ‘dinosaur’ fossils,” says Kammerer. “As I went through this collection I found more and more bones matching a dicynodont instead of a dinosaur, representing parts of the skull, limbs, and spinal column.” This was exciting — despite over a century of extensive collection, no skeletal evidence of a dicynodont had ever been recognized in the Late Triassic of South Africa.

Before this point, the only evidence of dicynodonts in the southern African Late Triassic was from questionable footprints: a short-toed, five-fingered track named Pentasauropus incredibilis (meaning the “incredible five-toed lizard foot”). In recognition of the importance of these tracks for suggesting the existence of Late Triassic dicynodonts and the contributions of “Gogga” Brown in collecting the actual fossil bones, the re-discovered and newly described dicynodont has been named Pentasaurus goggai (“Gogga’s five-[toed] lizard”).

“The case of Pentasaurus illustrates the importance of various underappreciated sources of data in understanding prehistory,” says Kammerer. “You have the contributions of amateur researchers like ‘Gogga’ Brown, who was largely ignored in his 19th century heyday, the evidence from footprints, which some paleontologists disbelieved because they conflicted with the skeletal evidence, and of course the importance of well-curated museum collections that provide scientists today an opportunity to study specimens collected 140 years ago.”

A video about this new research can be found here: https://youtu.be/BrdwIQKPCHY

Story Source:

Materials provided by North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

0 notes

Photo

Morning all - 46-30: The Route to the Harmonium special. Stephen Marshall of Triassic Tusk Records and Phill Jupitus talk to James Yorkston about his new album 'The Route to the Harmonium'. 46-30: The Route to the Harmonium special https://anchor.fm/46-30/episodes/46-30-The-Route-to-the-Harmonium-special-e39q27 https://www.instagram.com/p/BuQlRYNgcNB/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=5d9wca239tuq

0 notes

Video

instagram

46☆30☆50 - With rare and exclusive tracks from Seamus Fogarty, FourTet, Yorkston Thorne Khan, Triassic Tusk Records, Withered Hand and more https://anchor.fm/46-30/episodes/463050---With-rare-and-exclusive-tracks-from-Seamus-Fogarty--FourTet--Yorkston-Thorne-Khan--Triassic-Tusk-Records-and-more-edte0o (at Cellardyke) https://www.instagram.com/p/CADdkqzHGWs/?igshid=1qtjhozznmesv

0 notes