#conchifera

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mimic octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus)

Photo by Marcel Gierth

#id'ing#mimic octopus#thaumoctopus mimicus#thaumoctopus#octopodidae#octopodoidea#incirrata#octopoda#octopodiformes#coleoidea#cephalopoda#conchifera#mollusca

173 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion Month #26: Phylum Mollusca – Tentacle Time

Cephalopods' highly distinctive body plan and incredible intelligence make them some of the most charismatic marine animals. Today they're mainly represented by the soft-bodied coleoids (octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish), with the modern giant squid and colossal squid being the largest living invertebrates. In comparison the shelled nautiluses seem like weird oddballs, but they're actually far more typical examples of the group than their squishier cousins – as part of the conchiferan lineage the ancestors of all modern cephalopods were also shell-bearing molluscs, and for much of their evolutionary history shelled forms like ammonites and orthoceridans were extremely abundant.

The exact evolutionary relationships of cephalopods within the conchiferan family tree aren't clear, but their closest relatives might be modern monoplacophorans and they probably descended from limpet-like "monoplacophoran-grade" ancestors in the early Cambrian. The current oldest potential cephalopod fossils come from about 522 million years ago, but the first definite cephalopods in the fossil record come from much later in the period.

Plectronoceras cambria was a tiny early nautiloid, known from the Late Cambrian of eastern China (~490-485 million years ago). Its shell was about 2cm long (0.8") and it had the characteristic features of cephalopod phragmocones – chambers, septa, and a siphuncle.

This suggests it had internal air spaces reducing the density of its shell and acting as a buoyancy control mechanism, but its shell shape also indicates it wasn't adapted for jet-powered swimming like later cephalopods. Instead it may have mostly crawled around on the sea floor, while also being able to float up vertically into the water column either to avoid predators or to access new food sources.

———

But there's a complication in the simple-seeming story of shelled ancestral cephalopods learning to float, and its name is Nectocaris pteryx.

Known from the Canadian Burgess Shale fossil deposits (~508 million years ago), the Australian Emu Bay Shale (~514 million years ago), and the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago), this animal had a surprisingly squid-like body with fleshy fins, two tentacles, stalked eyes, a siphon-like funnel, and no sign of a shell.

It also came in two different "size morphs", one about 3cm long (1.2") and the other about 10cm long (4"), which might represent sexual dimorphism.

For a long time it was known from only a single incomplete fossil from the Burgess Shale, with uncertain classification and strange-looking attempted reconstructions. But in 2010 many more better-preserved fossils revealed that Nectocaris seemed to be some sort of early soft-bodied cephalopod, pre-dating early nautiloids like Plectronoceras by almost 30 million years.

It's generally thought to be a member of a short-lived stem lineage that diverged early on in the groups' history, convergently losing their shells and developing a resemblance to modern coleoids – a sort of early "experiment" in coleoid-like fast active swimming, but which ultimately failed and didn't happen again until the true coleoids evolved a couple of hundred million years later.

…Except there's now yet another twist.

The recently-discovered Nectocotis rusmithi is a nectocaridid from Late Ordovician deposits in the state of New York, USA, dating to about 450 million years ago. It demonstrates that these early cephalopods survived for much longer than previously thought, and even made it through the end-Cambrian extinction event that wiped out all but one lineage of the shelled cephalopods.

And it had an internal shell – but made of a tough non-mineralized substance rather than calcium carbonate.

This brings up a couple of interesting evolutionary possibilities:

Nectocaridids might still be a weird early convergently-squid-like side branch of cephalopod evolution that internalized their shells, with Nectocaris losing the shell completely while Nectocotis retained a non-mineralized version.

Or, shells might have actually been non-mineralized (and possibly also internal) from the start in ancestral cephalopods – potentially explaining the lack of earlier Cambrian fossils. Early forms were Nectocaris-like active swimmers with a high metabolic rate, and nautiloids like Plectronoceras evolved from them during the late Cambrian when oxygen levels were dropping and such high levels of activity were less sustainable, developing mineralized external shells with energy-saving passive buoyancy and lower metabolisms.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion 2021#cephalopod#mollusc#conchifera#plectronoceras#nautiloid#nectocaris#lophotrochozoa#spiralia#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#convergent evolution

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini)

Photo by AquaDom & SEA LIFE Berlin

#sourcing#giant pacific octopus#enteroctopus dofleini#enteroctopus#enteroctopodidae#octopodoidea#incirrata#octopoda#octopodiformes#coleoidea#cephalopoda#conchifera#mollusca

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

splatoon oc,,, beloved fish uses he/him :-)

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zuhause... #schnecke, #bilateria, #urmünder, #protostomia, #lophotrochozoen, #weichtiere, #mollusca, #schalenweichtiere, #conchifera, #gastropoda, #slug, #weinrebe, #gehäuse, #tier, #animal, #steiermark, #styrua, #südsteiermark, #southernstyria, #österreich, #austria, #matom, #tierfotografie, (hier: Sankt Veit, Steiermark, Austria) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bx64Hg9pTE0/?igshid=19r2z26b8zchv

#schnecke#bilateria#urmünder#protostomia#lophotrochozoen#weichtiere#mollusca#schalenweichtiere#conchifera#gastropoda#slug#weinrebe#gehäuse#tier#animal#steiermark#styrua#südsteiermark#southernstyria#österreich#austria#matom#tierfotografie

0 notes

Photo

A cuttlefish with especially large, shiny eyes from Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s The book of shells : containing the classes Mollusca, Conchifera, Cirrhipeda, Annulata, and Crustacea (1837)

Full text available here.

456 notes

·

View notes

Photo

new guy dropped. his focus is marine malacology with specialization towards conchifera

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phragmoteuthis

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Fence squid

First Described By: Mojsisovics, 1882

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Protostomia, Spiralia, Platytrochozoa, Lophotrochozoa, Mollusca, Conchifera, Cephalopoda, Coleoidea, Belemnoidea, Phragmoteuthida, Phragmoteuthidae

Referred Species: P. bisinuata, P. huxleyi, ?P. ticinensis

Status: Extinct

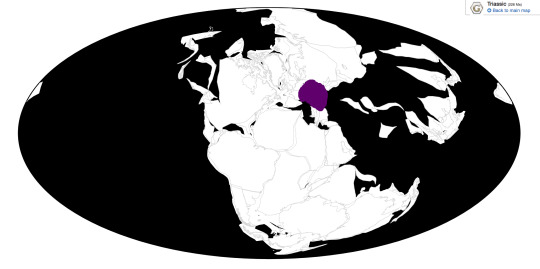

Time and Place: 247 to 190 million years ago, from the Anisian of the Middle Triassic to the Sinemurian of the Early Jurassic.

Phragmoteuthis is known from Austria, England, Germany, and Switzerland.

Physical Description: Externally, Phragmoteuthis would have resembled a modern squid. However, it is a member of the now-extinct belemnoids. It had a long mantle, an internal shell, and ten equally-sized hook-bearing arms, none of which were developed into tentacles. Unlike squids, the internal shell of belemnoids had a distinct hollow phragmocone, like earlier Paleozoic cephalopods. This shell also had a long, flat portion anteriorly called a proostracum. The proostractum in Phragmoteuthis was wide and lobed. Posteriorly the shell formed a pointed, horny guard called a rostrum. These rostra are the most commonly found belemnoid fossils. Several specimens of Phragmoteuthis preserve an ink sac, indicating that like most modern cephalopods, it produced a dark ink. Other early belemnoids preserve a pair of rhomboidal fins on the posterior mantle, allowing us to infer the presence of this in Phragmoteuthis.

Diet: It is presumed that belemnoids had similar diets to modern squids, being predators of smaller organisms such as fish.

Behavior: Little is known about belemnoid behavior. Phragmoteuthis was likely an active shallow-water predator, using the hooks on its arms to catch prey such as fish and smaller mollusks. Like all cephalopods, Phragmoteuthis would have been able to propel itself by expulsing water from its siphon. The phragmocone would have helped the animal maintain buoyancy, and the rostrum may have counterbalanced the heavier head region. Ink would have also been expelled from the siphon as a defense mechanism, to confuse potential predators and provide a chance for escape. The frequency of belemnite fossils found implies that belemnites may have been gregarious in life, which could have also applied to Phragmoteuthis.

Ecosystem: Phragmoteuthis lived in coastal areas like most other belemnoids. In fact, one formation that preserves Phragmoteuthis also fossilizes land plants like bennettitales and cycads and insects such as beetles, indicating that that specific spot in Carnian Austria was likely a shoreline. P. bisinuata lived alongside many ray-finned fish such as Sauricthys, Polzbergia, and Thoracopterus, and the other common clade of Mesozoic cephalopods: ammonites, such as Austrotrachyceras. ?P. ticinensis lived alongside ichthyosaurs such as Mikadocephalus and Mixosaurus, pachypleurosaurs such as Serpianosaurus, and more fish, including Gyrolepis, Habroichthys, and Ptycholepis. These ichthyosaurs, as well as large fish, may have fed on Phragmoteuthis, as other belemnoids are sometimes found fossilized inside ichthyosaur and pachycormid guts.

Other: The classification Phragmoteuthis has been contentious - although previously considered an abberant lineage of coleoid cephalopods, more recent authors have considered it an early belemnoid. Some well-known Jurassic species have since been reclassified as the unrelated Clarkeiteuthis. Phragmoteuthids such as Phragmoteuthis are considered transitional between earlier Paleozoic cephalopods and the later, more common belemnites.

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources under the Cut

Doguzhaeva, L., Summesberger, H., Mutvei, H., Brandstaetter, F. (2007). “The mantle, ink sac, ink, arm hooks and soft body debris associated with the shells in Late Triassic coleoid cephalopod Phragmoteuthis from the Austrian Alps”. Palaeoworld 16 (4): 272-284.

Donovan, D. T. “Phragmoteuthida (Cephalopoda: Coleoidea) from the Lower Jurassic of Dorset, England”. Palaeontology 49 (3): 673-684.

Fuchs, D., Donovan, D.T., Keupp, H. (2013). “Taxonomic revision of “Onychoteuthis” conocauda Quenstedt, 1849 (Cephalopoda: Coleoidea)”. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlugen 270 (3): 245-255.

Fuchs, D., Donovan, D.T. (2018). “Part M, Chpater 23C: Systematic Descriptions: Phragmoteuthida”. Treatise Online 111.

Griffith, J. (2008). “The Upper Triassic fishes from Polzberg bei Lunz, Austria”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 60 (1): 1-93.

Hanlon, R., Vecchione, M., Allcock, L. (2018). Octopus, Squid & Cuttlefish. University of Chicago Press.

Rieber, H. (1970). “Phragmoteuthis? ticinensis n. sp., ein Coleoidea-Rest aus der Grenzbitumenzone (Mittlere Trias) des Monte San Giorgio (Kt. Tessin, Schweiz)”. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 44: 32-40.

#Phragmoteuthis#Squid#Triassic#Mollusc#Palaeoblr#Phragmoteuthis bisinuata#Phragmoteuthis huxleyi#Phragmoteuthis ticinensis#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Triassic Madness#Triassic March Madness

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hemphill's file shell (Limaria hemphilli)

Photo by Robyn Waayers

#fave#hemphill's file shell#file shell#limaria hemphilli#limaria#limidae#limoidea#limida#pteriomorphia#bivalvia#conchifera#mollusca

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion Month #25: Phylum Mollusca – Shelling Out

The exact evolutionary relationships of the main groups of modern molluscs are rather debated, with several different proposed family trees. But one of the main possibilities is that there are two major lineages: the aculiferans and the conchiferans.

Modern conchiferans include slugs and snails, cephalopods, bivalves, tusk shells, and monoplacophorans – all groups that ancestrally have either a single-part shell or a two-part bivalved shell, with some lineages later becoming secondarily shell-less.

The ancestral conchiferans are thought to have been monoplacophoran-like molluscs, limpet-like with a cap-shaped shell, and likely diverged from a common ancestor with the aculiferans around the end of the Ediacaran. (But modern monoplacophorans probably aren't "living fossil" descendants of early Cambrian conchiferans, and may instead be close relatives of cephalopods that have convergently become similar in appearance to their ancestors.)

Some of the earliest conchiferans were the helcionelloids, a lineage of superficially snail-like molluscs with coiled cone-shaped mineralized shells. They appeared in the fossil record at the start of the Cambrian (~540-530 million years ago) and lasted until the early Ordovician (~480 million years ago), and have been found all around the world as components of the "small shelly fauna".

And while they're usually tiny, only a couple of millimeters in size, they may actually represent juveniles or larvae – there's evidence that at least some species grew up into much larger 2cm (0.8") limpet-like adult forms.

Some helcionelloids like Yochelcionella americana had an odd tubular snorkel-like structure growing from their shells. This was probably part of their breathing system, serving as an "exhaust pipe" for the water passing over their gills, and may be an evolutionary link to the siphons or siphuncles of other conchiferans.

About 2mm long (0.08"), this particular species is known from the Forteau Formation in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada (~514 million years ago) and also from similarly-aged deposits in Pennsylvania and Greenland. Other species in the same genus are found worldwide between about 530 and 505 million years ago.

———

In some parts of Yochelcionella americana's range it coexisted with another type of widespread early conchiferan – one of the first known bivalves, Pojetaia runnegari. Around 2mm long (0.08"), it would have lived either on or just under the surface of the seafloor.

It might have been related to a group of modern bivalves called protobranchs, or it may have been part of an early stem lineage with no close living relatives. It already had the basic bivalve body plan in place, with left and right valves, hinges, and shell-closing muscles, but doesn't seem to have had a siphon. Unfortunately it doesn't really give us much insight into the evolutionary origins of the group, and the appearance of the ancestral "proto-bivalves" is still unknown – but the microstructure of Pojetaia's shell may indicate a possible evolutionary link with the helcionelloids.

———

While the helcionelloids superficially resembled snails, it's unclear if they were closely related to actual gastropods.

Fossils that might be true early gastropods first turn up in the mid-to-late Cambrian, with a group called bellerophonts. These molluscs had near-symmetrically coiled shells compared to the helical coiling of most gastropods, and they had quite a long run as a group, lasting all the way until the early Triassic (~249 million years ago).

Strepsodiscus austrinus is known from the Lampazar Formation in Argentina, dating to about 490-485 million years ago at the end of the Cambrian. About 3cm long (1.2"), its shell was very slightly coiled to the left, and it seems to have been a detritivore living on soft seafloor sediments.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion 2021#mollusc#conchifera#yochelcionella#helcionelloida#pojetaia#bivalve#strepsodiscus#bellerophontoidea#gastropod#lophotrochozoa#spiralia#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thistle scallop (Lindapecten exasperatus)

Photo by Judy Townsend

#sourcing#thistle scallop#lindapecten exasperatus#lindapecten#pectinidae#pectinoidea#pectinida#pteriomorphia#bivalvia#conchifera#mollusca#lophotrochozoa

416 notes

·

View notes

Photo

finley profile is up :-) https://toyhou.se/3710062.finley

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

why its neil! she/they Thats the tech person, she designs gear!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

finley again :-)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bellerophon

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Bellerophon, for the Greek mythological hero

First Described By: Montfort, 1808

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Protostomia, Spiralia, Platytrochozoa, Lophotrochozoa, Mollusca, Conchifera, Gastropoda, Bellerophontida, Bellerophontina, Bellerophontoidea, Bellerophontidae, Bellerophontinae

Referred Species: Too many to list here

Status: Extinct

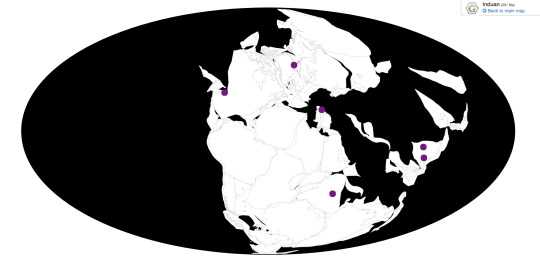

Time and Place: 453 to 251 million years ago, from the Katian of the Late Ordovician to the Induan of the Early Triassic.

In the Triassic, Bellerophon is known from Wyoming, Greenland, Italy, China, and eastern Russia.

Physical Description: What is it? It’s a snail. The only fossil remains we have of it are shells, which are wide, coiled, and may or may not have external ribbing. Unlike many modern snails, the coiling did not lean to one side. It superficially resembles the shell of a nautilus, but lacked the complex inner chambering cephalopod shells have. The interior of the shell was simply one large open space in which the snail’s body would have coiled. There would have been plenty of it outside the shell, though; the head, of course, and a large muscular foot which which it moved. With Bellerophon in particular, a good amount of the mantle and foot was exposed, and covered part of the outside of the shell. This was common among bellerophontidans.

Diet: Bellerophon’s diet is unknown. Modern marine snails can eat pretty much anything, so nothing is really out of the question for Bellerophon.

Behavior: Bellerophon probably lived like most snails today: slowly crawling across the seafloor, eating without a care in the world. As a large portion of the mantle was exposed, it may have had difficulty retreating into its shell when threatened by predators. Thus, it likely burrowed into the sandy seafloor to avoid predators, like some marine snails do today.

Ecosystem: Bellerophon lived in shallow marine habitats. It lived alongside brachiopods, bivalves, other gastropods (including other bellerophontids), and ammonites. Bellerophon-containing rocks do not contain a lot of charismatic vertebrate taxa (in part because a lot of charismatic vertebrate taxa were freshly dead).

Other: There’s quite a bit of discourse over which species actually belong to Bellerophon. A few Triassic species have been moved to Retispira. Dicellonema may or may not belong to Bellerophon. There’s even been an older hypothesis that Bellerophon wasn’t a snail at all, but a more basal mollusk (in the likely polyphyletic “Monoplacophora”). This sort of taxonomic minutiae is 60% of what mollusk paleontologists talk about. For the purposes of this article, we’re adopting a more sensu lato Bellerophon.

Why am I writing about this random snail? Because this genus was incredibly long-lived. It first evolved in the late Ordovician. The ORDOVICIAN! And amazingly enough, this genus survived the Permian-Triassic extinction. It lasted for just over 200 million years. Aaaaand then it died out, along with almost every other bellerophontidan, very shortly afterwards. This is a phenomenon known as dead clade walking - when an event isn’t bad enough by itself to completely wipe out a taxon, but it messes it up badly enough that the taxon is consigned to extinction shortly afterwards. Only a handful of bellerophontidans are found after the Induan, with the very very last possible member of the clade hailing from the Early Jurassic.

In this way, they parallel the fate of the clade’s namesake from Greek mythology: Bellerophon. From humble beginnings, Bellerophon ended up in the service of King Iobates, who wanted him dead (for you see, Bellerophon was accused of lusting after Iobates’ daughter). To get rid of him without killing him (because killing your guest would be rude), he was given the task of slaying the three-headed, fire-breathing Chimera. He captured and tamed the winged horse Pegasus, and armed only with his bravery and a block of lead on a stick, he slayed the Chimera. For this he became a famous hero. But the fame got to his head, and one day he tried to ride Pegasus up to Olympus. Zeus was pissed at this, so he sent a gadfly to sting Pegasus. Pegasus bucked Bellerophon off, and he landed on a thorny bush, which broke many of his bones and punctured both of his eyes. He spent the rest of his days morosely wandering the land until his death.

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources Under the Cut

Harper, J.A., Rollins, H.B. 1985. Infaunal or semi-infaunal bellerophont gastropods: analysis of Euphemites and functionally related taa.

Homer. 8th century BC, probably. Iliad.

Kaim, A., Nutzel, A. 2011. Dead bellerophontids walking - The short Mesozoic history of the Bellerophontoidea (Gastropoda). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 308(1-2): 190-199.

Linsley, R.M. 1978. Locomotion rates and shell form in the Gastropoda. Malacologia 17: 193-206.

Smith, W. 1849. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology.

Yochelson, E.L., Yin, H. (1985). Redesription of Bellerophon asiaticus Wirth (Early Triassic: Gastropoda) from China, and a Survey of Triassic Bellerophontacea. Journal of Paleontology 59(5): 1305-1319.

#bellerophon#bellerophontidan#bellerophontid#gastropod#mollusk#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#paleontology#prehistoric life

109 notes

·

View notes