#Traditional ecological knowledge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#TextileTuesday:

“Border fragment of wool with a continuous band of #hummingbirds and fringelike appendages representing beans. Early Nasca [Nazca, Peru, c.1-450 CE]. Pollination of bean plants by birds may be suggested here. Border was formed using a needle-knit stemstitch.”

On display at American Museum of Natural History [41.2/6321]

#animals in art#birds in art#bird#birds#museum visit#AMNH#hummingbird#hummingbirds#Peruvian art#Andean art#Nazca art#Textile Tuesday#textile#wool#ancient art#pollination#Indigenous art#ethnobotany#erhnozoology#ethnobiology#TEK#traditional ecological knowledge#South American art

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Legislation passed last year allows federally recognized tribes to practice cultural burning freely once they reach an agreement with the California Natural Resources Agency and local air quality officials.

Northern California’s Karuk Tribe, the second largest in California, becomes the first tribe to reach such an agreement.

(Feb. 27, 2025, Noah Haggerty)

Northern California’s Karuk Tribe has for more than a century faced significant restrictions on cultural burning — the setting of intentional fires for both ceremonial and practical purposes, such as reducing brush to limit the risk of wildfires.

That changed this week, thanks to legislation championed by the tribe and passed by the state last year that allows federally recognized tribes in California to burn freely once they reach agreements with the California Natural Resources Agency and local air quality officials.

The tribe announced Thursday that it was the first to reach such an agreement with the agency.

“Karuk has been a national thought leader on cultural fire,” said Geneva E.B. Thompson, Natural Resources’ deputy secretary for tribal affairs. “So, it makes sense that they would be a natural first partner in this space because they have a really clear mission and core commitment to get this work done.”

In the past, cultural burn practitioners first needed to get a burn permit from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, a department within the Natural Resources Agency, and a smoke permit from the local air district.

The law passed in September 2024, SB 310, allows the state government to, respectfully, “get out of the way” of tribes practicing cultural burns, said Thompson.

For the Karuk Tribe, Cal Fire will no longer hold regulatory or oversight authority over the burns and will instead act as a partner and consultant. The previous arrangement, tribal leaders say, essentially amounted to one nation telling another nation what to do on its land — a violation of sovereignty. Now, collaboration can happen through a proper government-to-government relationship.

The Karuk Tribe estimates that, conservatively, its more than 120 villages would complete at least 7,000 burns each year before contact with European settlers. Some may have been as small as an individual pine tree or patch of tanoak trees. Other burns may have spanned dozens of acres.

“When it comes to that ability to get out there and do frequent burning to basically survive as an indigenous community,” said Bill Tripp, director for the Karuk Tribe Natural Resource Department, “one: you don’t have major wildfire threats because everything around you is burned regularly. Two: Most of the plants and animals that we depend on in the ecosystem are actually fire-dependent species.”

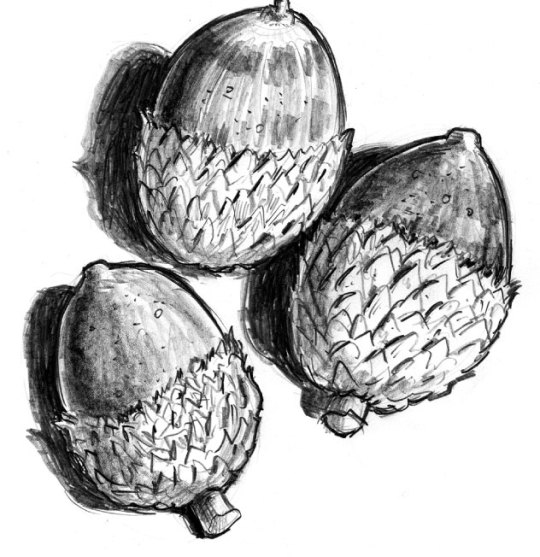

The Karuk Tribe’s ancestral territory extends along much of the Klamath River in what is now the Klamath National Forest, where its members have fished for salmon, hunted for deer and collected tanoak acorns for food for thousands of years. The tribe, whose language is distinct from that of all other California tribes, is currently the second largest in the state, having more than 3,600 members.

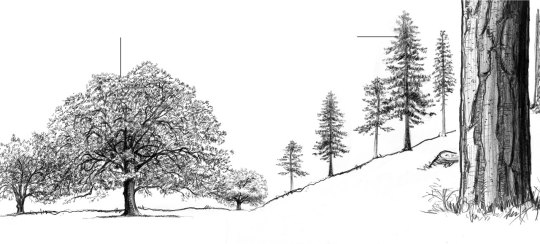

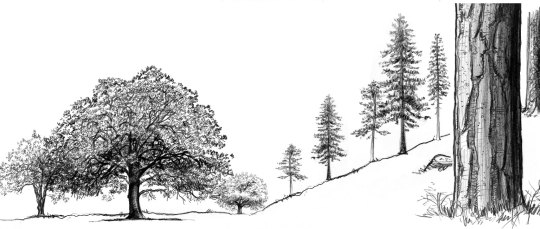

Trees of life

Early European explorers of California consistently described open, park-like woods dominated by oaks in areas where the forest transitions to a zone mainly of conifers such as pines, fir and cedar.

The park-like woodlands were no accident. For thousands of years, Indigenous people have tended these woods. Oaks are regarded as a “tree of life” because of their many uses. Their acorns provide a nutritious food for people and animals.

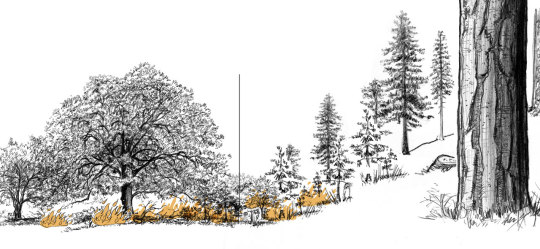

Indigenous people have used low-intensity fires to clear litter and underbrush and to nurture the oaks as productive orchards. Burning controls insects and promotes growth of culturally important plants and fungi among the oaks.

Debris, brush and small trees consumed by low-intensity fire.

The history of the government’s suppression of cultural burning is long and violent. In 1850, California passed a law that inflicted any fines or punishments a court found “proper” on cultural burn practitioners.

In a 1918 letter to a forest supervisor, a district ranger in the Klamath National Forest — in the Karuk Tribe’s homeland — suggested that to stifle cultural burns, “the only sure way is to kill them off, every time you catch one sneaking around in the brush like a coyote, take a shot at him.”

For Thompson, the new law is a step toward righting those wrongs.

“I think SB 310 is part of that broader effort to correct those older laws that have caused harm, and really think through: How do we respect and support tribal sovereignty, respect and support traditional ecological knowledge, but also meet the climate and wildfire resiliency goals that we have as a state?” she said.

The devastating 2020 fire year triggered a flurry of fire-related laws that aimed to increase the use of intentional fire on the landscape, including — for the first time — cultural burns.

The laws granted cultural burns exemptions from the state’s environmental impact review process and created liability protections and funds for use in the rare event that an intentional burn grows out of control.

“The generous interpretation of it is recognizing cultural burn practitioner knowledge,” said Becca Lucas Thomas, an ethnic studies lecturer at Cal Poly and cultural burn practitioner with the yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash Tribe of San Luis Obispo County and Region. “In trying to get more fire on the ground for wildfire prevention, it’s important that we make sure that we have practitioners who are actually able to practice.”

The new law, aimed at forming government-to-government relationships with Native tribes, can only allow federally recognized tribes to enter these new agreements. However, Thompson said it will not stop the agency from forming strong relationships with unrecognized tribes and respecting their sovereignty.

“Cal Fire has provided a lot of technical assistance and resources and support for those non-federally recognized tribes to implement these burns,” said Thompson, “and we are all in and fully committed to continuing that work in partnership with the non-federally-recognized tribes.”

Cal Fire has helped Lucas Thomas navigate the state’s imposed burn permit process to the point that she can now comfortably navigate the system on her own, and she said Cal Fire handles the tribe’s smoke permits. Last year, the tribe completed its first four cultural burns in over 150 years.

“Cal Fire, their unit here, has been truly invested in the relationship and has really dedicated their resources to supporting us,” said Lucas Thomas, ”with their stated intention of, ‘we want you guys to be able to burn whenever you want, and you just give us a call and let us know what’s going on.’”

#good news#environmentalism#traditional ecological knowledge#cultural burns#prescribed burns#california#fire#science#environment#nature#animals#usa#indigenous people#Karuk Tribe#indigenous conservation#conservation#indigenous peoples#indigenous history#colonialism#decolonisation#decolonization#long post#intentional burns#climate change#climate crisis

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Portal on Indigenous Approaches to Freshwater Management in North America

Three case studies, one each from Canada, Mexico and the United States, examine the diverse freshwater contexts, issues and approaches of Indigenous Peoples across North America. From the glaciers of Alaska to the jaltunes of Campeche and the Red River and lakes of Manitoba, the videos produced capture the perspectives of Indigenous communities on freshwater, emphasizing their deep connections to the land and water.

An Online Knowledge Dialogue on Applying Indigenous Knowledge in Water Management: Models of Best Practice. This event served as a space for Indigenous Peoples across North America to share their priorities, experiences and relationships with freshwater. Selected cases highlighted the use, application, and significance of Indigenous Knowledge Systems (tools, approaches and methods) within the context of freshwater management.

An Indigenous-led Trinational Forum on Indigenous Approaches to Freshwater Management in North America, which took place in Oaxaca, Mexico. The event focused on Indigenous perspectives and stewardship practices in freshwater management, the vital role of TEK and the intersection of Indigenous rights in freshwater management across Canada, Mexico and the United States. Key issues included the growing North American consensus that TEK and Indigenous Knowledge Systems are passed down through generations and expressed knowledge values and skills that Indigenous Peoples have relied upon since time immemorial.

#solarpunk#solar punk#community#indigenous knowledge#jua kali solarpunk#north america#indigenous peoples#traditional ecological knowledge#environment#climate change#water#canada#mexico#united states

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fire suppression p.1 & p.2: “Flame Retardant” & “Building Potential” Inspired by the PEM's ‘Our Time on Earth’ exhibit

I was gladly surprised to see the exhibit’s various optimistic installations, especially the building materials of the future. As a forestry student I am beginning to understand our relationship to our forests differently. In the US, forest policy which aimed to suppress wildfires has contributed to a century-long build up of fuel that would otherwise have been cleared by controlled burns or small spontaneous ground fires. Indigenous peoples shaped the forests of the Americas to require these controlled burns. More and more I realize that indigenous knowledge and collaboration is a necessary part of the stewardship of future. A concept which is present at large at the museum but also specifically within Our Time on Earth. Getting a ‘sustainable’ amount of lumber from our forest still disregards the health and purpose of these trees to a diverse and complex ecosystem. It is essential that we diversify our building material, to include carbon-negative things like mycelium! Natural resources that are close by, and at hand in our local environment, which doesn’t require chopping down a tree 3000 miles away and transporting it to the US. We need local resources whose collective cultivation lead to a sense of community and collaboration. A better future!

My thanks to lane.m.artin for collaborating with me for p.2!

#acrylic painting#artists on tumblr#PEM#peabody essex museum#climate change#fire suppression#wild fire#TEK#Traditional ecological knowledge#controlled burning#art of mine#solarpunk#is how i would describe the exhibit but listen I am just doing my best and maybe this gallery might even see this piece in it's peripheral#and thats a win#contemporary art

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It is simply impossible to overstate both the importance of the buffalo to the Indian people and the damage that was done when the buffalo were nearly wiped out,” ITBC President Ervin Carlson said in a statement. “By helping tribes reestablish buffalo herds on our reservation lands, the Congress will help us reconnect with a keystone of our historic culture as well as create jobs and an important source of protein that our people truly need.”

#bison#buffalo#short grass prairie#conservation#sustainability#economic development#traditional ecological knowledge#ecological restoration#species conservation

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the Field #2: what is fire ecology and why does it matter?

ok so. let’s talk about fire. not as a disaster, but as a natural, ancient, necessary process.

fire ecology is the study of how fire interacts with ecosystems. not just how things burn, but how fire shapes the land, how species respond to it, and how entire systems rely on it. it’s part of the cycle of life. dramatic, chaotic, and weirdly healing.

you’ll hear people say things like “the forest needs to burn,” and they’re not being edgy. some trees like lodgepole pine and knobcone pine literally need heat to open their cones. some grasses grow back stronger after a burn. fire recycles nutrients, clears out dead biomass, and reduces competition. it can help control pests and disease. it opens up space and light. and in many ecosystems—especially rangelands, chaparral, and savannas—fire is just part of how things work.

but here’s the problem. we’ve spent over a century trying to keep fire off the landscape.

colonization erased Indigenous fire stewardship—practices that worked with fire instead of fearing it. then came decades of aggressive suppression (thanks, smokey the bear) and more and more development pushing into wild spaces. now, mix in hotter temps, drier vegetation, and longer fire seasons because of climate change, and yeah. things aren’t looking great.

we’re seeing more extreme wildfires because we’ve created the perfect conditions for them. overloaded fuels, flammable invasives like cheatgrass and buffelgrass, drought-stressed plants, and a general disconnect between people and land.

this is where fire ecology comes in.

it helps us understand how fire behaves, how ecosystems respond, and how to restore balance. it supports the use of prescribed burns, fire-adapted planning, and listening to the Indigenous knowledge that’s been ignored for too long. it lets us ask better questions about what resilience actually looks like.

it also helps us shift the mindset. fire isn’t always bad. it’s not something we can just get rid of. it’s part of the system. and pretending we can live without it hasn’t worked out well for anyone.

if fire is as old as the land itself, and it built the ecosystems we depend on, what does it say that we treat it like a mistake?

─── ・ 。゚☆: *.☽ .* :☆゚. ───

sources:

Sugihara, N.G. et al. (2006). Fire in California’s Ecosystems.

Ryan, K.C., Knapp, E.E., & Varner, J.M. (2013). Prescribed fire in North American forests and woodlands: History, current practice, and challenges. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

Keeley, J.E., & Fotheringham, C.J. (2001). History and ecology of fire in southern California ecosystems. USGS.

#range ecology#fire ecology#ecology#eco musings#from the field#antler & ash#fire#biodiversity#landscape#land stewardship#indigineous people#traditional ecological knowledge

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tapayuna, also known as Beico or Beiço-de-Pau (a Portuguese exonym referencing traditional lip plugs), are an Indigenous group of Brazil belonging to the larger Arawakan linguistic family. Historically inhabiting the transitional zones between the Amazon rainforest and the Brazilian Cerrado, the Tapayuna have experienced significant social, territorial, and demographic transformations, particularly during the 20th century due to external pressures from colonization, state intervention, and infrastructural development. Despite periods of cultural suppression and population decline, the Tapayuna people have demonstrated resilience and have worked toward the revitalization of their language and cultural traditions in recent decades.

The autonym Tapayuna is the preferred designation used by the group themselves. The alternative name "Beico" or "Beiço-de-Pau" was imposed by outsiders, referring to the traditional use of wooden lip plugs among Tapayuna men—an aesthetic and cultural practice that was stigmatized during the mid-20th century. As with many Indigenous groups, externally imposed names often reflect colonial perspectives, whereas the autonym is rooted in self-identification and carries cultural significance. The term "Tapayuna" is Arawakan in origin and linguistically reflects internal phonological patterns common to the family.

The Tapayuna language is part of the Northern branch of the Arawakan language family, which is one of the largest and most widespread Indigenous language families in South America. The Tapayuna language, like many others in this family, is polysynthetic, with complex morphology and verb serialization. As of the early 21st century, the language was considered moribund, with only a small number of fluent elderly speakers remaining, primarily in the state of Mato Grosso. Language shift toward Portuguese occurred largely due to contact with non-Indigenous society, missionary influence, and state educational policies.

Efforts in linguistic revitalization have been made, supported by partnerships between Indigenous leaders, linguists, and non-governmental organizations. Documentation projects have included the recording of oral traditions, grammar sketching, dictionary development, and the creation of bilingual pedagogical materials.

Historically, the Tapayuna occupied a region along the Arinos and Teles Pires Rivers in what is today northern Mato Grosso, Brazil. This region forms a biome transition zone between the Amazon rainforest and the Cerrado savanna, characterized by high biodiversity and ecological complexity. The original territory included seasonal floodplains, gallery forests, and upland savannas, which supported a mixed subsistence economy based on hunting, fishing, horticulture, and gathering.

In the 20th century, Tapayuna territory was heavily encroached upon due to the expansion of Brazilian agriculture, infrastructure projects (notably highways and hydroelectric dams), and governmental assimilation policies. Forced removals and displacement significantly altered their relationship with the land, leading to resettlement in demarcated Indigenous territories such as the Xingu Indigenous Park and later in other demarcated areas in Mato Grosso.

Traditionally, the Tapayuna practiced a diversified subsistence economy combining slash-and-burn horticulture with hunting, fishing, and foraging. Primary crops included manioc (cassava), maize, bananas, and a variety of tubers and fruits, cultivated in rotational plots known as roças. Hunting, carried out using bows and arrows and traps, targeted forest and savanna game such as peccaries, tapirs, monkeys, and various bird species. Fishing was carried out with nets, weirs, and occasionally plant toxins (fish poisons).

Craft production was both utilitarian and ceremonial: men crafted weapons, tools, and ornaments such as lip plugs and feather headdresses; women wove baskets and mats using natural fibers. The Tapayuna were historically semi-nomadic within their territory, relocating seasonally to optimize resource use, and maintained a reciprocal economy within kinship networks.

Today, while some traditional practices continue, many Tapayuna have integrated into the cash economy through artisanal sales, state support programs, and collaboration with NGOs. Shifts in diet, material culture, and labor have occurred, but subsistence farming and food sovereignty remain vital to cultural identity.

The Tapayuna social structure was historically organized around extended kinship groups and clans, each with specific roles and totemic associations. Kinship was bilateral, though patrilineal tendencies influenced inheritance and residence patterns. Marriages were often exogamous between clans, with bride service and other customary exchanges marking marital alliances. Chiefs or headmen (caciques) traditionally held authority based on age, wisdom, and oratorical skill, rather than coercive power.

Rites of passage marked transitions in age and social status, particularly male initiation, which involved seclusion, instruction in cosmological knowledge, and body modification practices such as the insertion of lip plugs and tattooing. These rites reinforced communal identity and social cohesion.

In contemporary contexts, formal Indigenous associations and leadership structures have emerged, interacting with Brazilian state mechanisms. Nevertheless, traditional authority figures remain important, particularly in cultural transmission and dispute resolution.

Tapayuna cosmology is deeply rooted in Arawakan shamanic traditions, emphasizing a multi-layered universe inhabited by a diverse array of spirits, ancestral beings, and natural forces. Shamans (called by local names, often translated as pajés in Portuguese) acted as mediators between the human and spiritual realms, conducting healing rituals, divinations, and protective ceremonies.

Myths explain the origins of the world, human beings, animals, and cultural practices. These narratives are preserved through oral tradition and are often recited during communal gatherings. Certain animals, such as jaguars and anacondas, are imbued with spiritual significance and feature prominently in Tapayuna stories as ancestors or transformative beings.

Although many Tapayuna have been exposed to Christianity through missionary efforts—particularly in the mid-20th century—traditional cosmologies remain influential, and syncretism is common.

The Tapayuna were relatively isolated until the mid-20th century. In the 1960s and 70s, they experienced catastrophic population decline due to diseases introduced during "pacification" missions conducted by the Brazilian state through the Indigenous Protection Service (SPI) and later the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI). Malaria, measles, and influenza ravaged populations with no prior immunity.

Survivors were relocated to the Xingu Indigenous Park, a multiethnic reserve established in 1961 under the Villas-Bôas brothers. There, the Tapayuna came into contact with other Indigenous groups such as the Kuikuro, Waurá, and Kayabi, leading to both cultural exchange and challenges of intergroup relations. The relocation was traumatic and resulted in a temporary suppression of Tapayuna identity due to stigmatization and pressure to assimilate.

In later years, surviving Tapayuna communities negotiated for the right to return to their ancestral lands and were granted access to new Indigenous territories in Mato Grosso. Demographic recovery has been slow but positive, supported by improved healthcare, education, and territorial rights enforcement.

Today, the Tapayuna continue to navigate a complex relationship with the Brazilian state, neighboring communities, and wider society. Legal recognition of land rights remains a central issue, as does the protection of environmental resources from illegal logging, land-grabbing, and agribusiness expansion. Cultural revitalization has become a key goal, particularly the teaching of the Tapayuna language to children, the revival of traditional festivals, and the assertion of cultural pride.

Educational initiatives include bilingual schooling, where possible, and workshops conducted with elders to pass on oral traditions. Political activism has increased, with Tapayuna representatives participating in national Indigenous congresses and advocacy networks.

The group remains small in number, but resilient and increasingly visible in public discourse surrounding Indigenous rights, Amazonian conservation, and cultural preservation.

#indigenous peoples#tapayuna#arawakan#indigenous brazil#cultural revitalization#language preservation#endangered languages#amazon indigenous#indigenous resistance#decolonize#indigenous rights#native voices#brazilian indigenous#protect the amazon#cultural heritage#ethnolinguistics#indigenous history#indigenous knowledge#indigenous culture#indigenous resilience#anthropology#colonial history#xingu park#indigenous revival#traditional ecological knowledge#land back#indigenous art#survivance#lip plug culture#post colonial voices

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

All my relatives: Exploring Lakota ontology, belief, and ritual. Posthumus DC (2022)

This is a book all about Lakota traditional beliefs and therefore has a lot of information connected to Mitakuye Oyasin. “At the heart of both Lakota religious continuity and innovation is an underlying animist ontological orientation, a basic way of seeing, understanding, and being in the world that extends personhood— in the form of a soul or spirit— to nonhuman life- forms.” This is expressed with ‘Mitakuye Oyasin’ –meaning ‘all my relatives’ or ‘we are all related’, which refers not only to human kinship but also to the relationship shared by all life-forms, both human and nonhuman, and the reciprocal obligations, responsibilities, and mutual respect that naturally extend from it” (14).

This repeats much of the ideas from similar definitions: belief in the connection between all life, relationships, the power the phrase has. It also gives a lot of words to help define these beliefs in academic language. Another important thing to point out is the way mitakuye oyasin is recognized as being part of Lakota innovation; my goal here is to use mitakuye oyasin to an innovation of queer ecology–hopefully add to the conversation.

“The normative cultural values encompassed by mitákuye oyásʾį are the very foundation of kinship, relational ontology, and the overarching interspecies collective, of which humans are only one hoop, one oyáte ‘people, nation, tribe’, in the company of many others. The key constituents of this animist ontology and worldview, of mitákuye oyásʾį, are persons, a category that extends beyond human beings to nonhuman or other- than- human persons. [...] Importantly, the Lakota worldview sees humans as the least knowledgeable and powerful beings, requiring the most aid and pity, upending the common Western biblical assumption that humans have dominion to rule over all other life- forms and subdue the earth (see V. Deloria 1999, 50; 2009, 99– 100). For the Lakotas, the seed of all life is wakʿą ‘sacrality, mystery, divinity’; ́ hence all life- forms share a generalized interiority, whether human or nonhuman.”

This is important information to support my argument. Queer ecology is very critical of Western beliefs and dichotomies that separate humans from nature and thereby present mankind as the ultimate lifeform (anthropocentrism). There are many essays and articles that examine the influence Christianity has had on the colonialist project (Gaard is the first that comes to mind). The Lakota worldview of being the ‘younger siblings’ of creation are supported by science in that ‘humans’ as a 'species' haven’t existed all that long in comparison to other 'species' and like many indigenous cultures, Lakota people knew the key to knowing nature was to learn from the world around us, as the author later confirms:

“Deloria explains that “the oldest traditions say that humans learned politeness and courtesy from the animals. . . . Generations of elders had already observed the behavior of birds . . . and decided that emulating them was the proper way for humans to act” (V. Deloria 2009, 123). Standing Bear (2006a, 56) substantiates this, writing, “The Lakota enjoyed his association with the animal world. For centuries he derived nothing but good from animal creatures. From them were learned lessons in industry, fidelity, and many virtues and much knowledge.” (50-51)

In the author’s footnotes is Vine Deloria’s examination of mitakuye oyasin that is, I feel, a great support of my claim:

“Vine Deloria refers to mitákuye oyásʾį as the ‘Indian principle of interpretation/observation,’ calling it “a practical methodological tool for investigating the natural world and drawing conclusions about it that can serve as guides for understanding nature and living comfortably within it. . . . We observe the natural world by looking for relationships between various things in it. . . . This concept is simply the relativity concept as applied to a universe that people experience as alive and not as dead or inert” (1999, 34). (Posthumus 2022 p219 f)

Queer ecology’s goal in many ways is to critique the ways the Western scientific paradigm has created inequity. Many are seemingly searching for solutions and answers to the problems that have been perpetuated by the colonial empire, supported as it is by western science.

While we must always, always be careful of appropriation and misappropriation–I contend that the solutions are not ones that need to be ‘discovered’ or solved in the way that Western science is so often searching for–advancement, the future…but rather, the answers are in what has always been there…and it’s simply a matter of observation.

#queer ecology#mitakuye oyasin#queer theory#ecofeminism#critical ecology#colonialism#all my relatives#lakota#indigenous studies#postcolonial theory#ecology#science#traditional ecological knowledge#queering ecology#ecosystems#environment#social ecology#long post

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

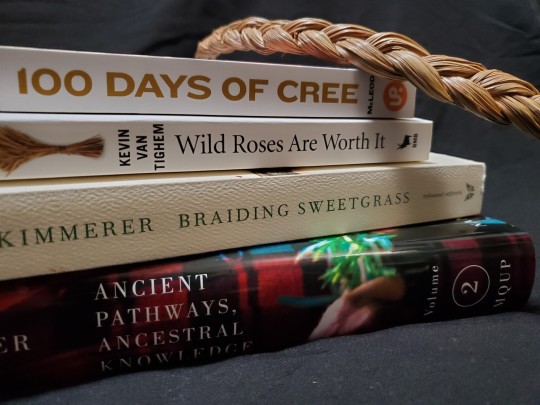

My goal is to read 30 books this year. I basically stopped reading for fun in grad school so now I'm trying to make up for lost time. There have been lots of fun fiction reads already (this is the year of fantasy romance apperently), but here is my non-fiction stack. Clearly it has a strong theme to it.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great mullein, Verbascum thapsus

Native to Europe, Northern Africa, and Asia, and invasive throughout the United States and Australia. It has many traditional uses, including to treat lung ailments and skin irritations. It's also known as "natures toilet paper" due to its large and soft leaves.

#plants#foraging#traditional medicine#nature#naturalist#great mullein#forager#ecologist#ecology#biologist#biology#traditional ecological knowledge#north america#photography#mine#plant#botany#midwest#nature photography

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watching this for the Aboriginal Worldviews and Education course on coursera, and omg. The youtube description: "Babakiueria (Barbeque Area) is a 1986 Australian satirical film on relations between Aboriginal Australians and Australians of European descent." If you have half an hour, I highly recommend!

#Youtube#aboriginal#aboriginal rights#indigenous rights#TEK#traditional ecological knowledge#Australia#‘straya#Coursera#free education

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self-Determined: Climate Resilience Is Sacred

Davis Price & Ilima-Lei Macfarlane

#climate resilience#climate action#climate activism#sustainability#indigenous rights#indigenous people#traditional ecological knowledge#climate news#good news#environmentalism#science#environment#nature#animals#conservation#climate change#climate crisis#usa#climate and environment#climate justice#climate emergency#climate science#climate solutions

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Running to the Forests

To love something is to let it go, to love something is to allow it to exist free from the confines of your perception. To love the forest is to allow it to burn in search of greatness, and to love the burnt trees is to allow them time and space to regenerate.

We the people cannot be separated from the branches of the trees, humans have been on the continent of North America for tens of thousands of years, and generations of people have grown up among the pines.

Here in Western Montana, you can see the smoke across the horizon, another reminder the people here have been removed from the land they love. It's not that they would not allow the burns, on the contrary, but the new methods of forest stewardship are not those that show love to the lands. Culturally important species, those that hold a place in societal practice and often in spirituality, are being choked by "common sense".

To assume with fire comes damage is understandable, we can see the smoky ghosts of ponderosas and fir, and run our hands across the blackened bark until we too are covered in a layer of char. The next season, among black spires and broken branches, the huckleberries and the deer and the other brothers and sisters of the forest will come. The trees will sprout again, cones opened by the flames, growing green toward the sky like their ancestors have for generations. There is beauty in the desolation, for it is merely a new beginning, not a time of destruction.

And just like the trees, sometimes humans need to let themselves burn to bring forth more beauty. Sometimes we need to let what comes, come, and what may be, be. Fill yourself with wildfire smoke, let the fire open pinecones of hope and potential, and bring forth the worlds inside your heart.

#ponderosa#douglas fir#spruce trees#wildfires#climate action#climate change#environmental science#forestry#traditional medicine#traditional ecological knowledge#academia#college#ethnobotany#montana#university of montana#missoula#western#american west#native traditions#american ecology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Politically, we stand at a precipice and it’s worrisome. 🇺🇸 One thing I’m rejoicing in today is the native plant movement is reaching the masses. We need to listen to traditional indigenous knowledge to heal the land.

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

#fave#controlled burns#controlled fires#indigenous practices#native american practices#colonization#traditional ecological knowledge#indigenous science

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hope it's okay to add on this video I saw the other day on this subject:

youtube

What I was taught growing up: Wild edible plants and animals were just so naturally abundant that the indigenous people of my area, namely western Washington state, didn't have to develop agriculture and could just easily forage/hunt for all their needs.

The first pebble in what would become a landslide: Native peoples practiced intentional fire, which kept the trees from growing over the camas praire.

The next: PNW native peoples intentionally planted and cultivated forest gardens, and we can still see the increase in biodiversity where these gardens were today.

The next: We have an oak prairie savanna ecosystem that was intentionally maintained via intentional fire (which they were banned from doing for like, 100 years and we're just now starting to do again), and this ecosystem is disappearing as Douglas firs spread, invasive species take over, and land is turned into European-style agricultural systems.

The Land Slide: Actually, the native peoples had a complex agricultural and food processing system that allowed them to meet all their needs throughout the year, including storing food for the long, wet, dark winter. They collected a wide variety of plant foods (along with the salmon, deer, and other animals they hunted), from seaweeds to roots to berries, and they also managed these food systems via not only burning, but pruning, weeding, planting, digging/tilling, selectively harvesting root crops so that smaller ones were left behind to grow and the biggest were left to reseed, and careful harvesting at particular times for each species that both ensured their perennial (!) crops would continue thriving and that harvest occurred at the best time for the best quality food. American settlers were willfully ignorant of the complex agricultural system, because being thus allowed them to claim the land wasn't being used. Native peoples were actively managing the ecosystem to produce their food, in a sustainable manner that increased biodiversity, thus benefiting not only themselves but other species as well.

So that's cool. If you want to read more, I suggest "Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America" by Nancy J. Turner

61K notes

·

View notes