#Tomomi Isao

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

June Birthdays

Here's the June kiddos! Coral and Mango are from my @cpclouds world!

Look at my many ocs ehe.

-------⭐

Wanna support me?

🍓 My commission are open! Check it out here

🍓 You can also support me via Patreon, Ko-Fi, Redbubble

#my art#ocs#digital art#art#my ocs#original character#artist#digital artist#artists on tumblr#oc#artyboneocs#Coral Lambert#Mango Bonnett#Daiki Tomomi#Tomomi Daiki#isao family#Isao Tomomi#Tomomi Isao

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

✧ New Video: {Ocs} Beautiful Day ✧

[Jun 2023] I still absolutely love this artwork! This artwork stem via a vent of mine, since when I created it I was going through a difficult time. The song "Notion" by The Rare Occasion. It's like a reminder that even in the darkest moment, one can still have fun. Ocs in the artwork are Soya Tadasuke and Tomomi Daiki. You can see the artwork on my main blog here! If you enjoy the video, consider subscribing!

youtube

#2023 art#2023 video#Youtube#Daiki Tomomi#Tomomi Daiki#Isao Tomomi#Tomomi Isao#Isao Family#Tadasuke Family#Soya Tadasuke#Tadasuke Soya#oc art#artuyboneocs#timelapse#speedpaint#finished art#digital drawing#oc artist#art process#art video

0 notes

Text

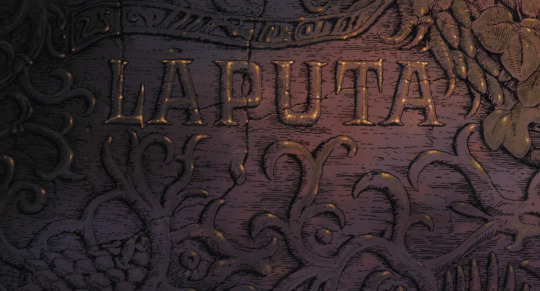

Studio Ghibli Title Cards, Part 1

"Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" ("Kaze no tani no Naushika") (1984) Directed by Hayao Miyazaki (Anime/Adventure/Sci-Fi) . . "Laputa: Castle in the Sky" ("Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa") (1986) Directed by Hayao Miyazaki (Anime/Adventure/Fantasy) . . "My Neighbor Tortoro" ("Tonari no Totoro") (1988) Directed by Hayao Miyazaki (Anime/Comedy/Fantasy) . . "Grave Of The Fireflies" ("Hotaru no haka") (1988) Directed by Hayao Miyazaki (Anime/Drama/War) . . "Kiki's Delivery Service" ("Majo no takkyûbin") (1989) Directed by Hayao Miyazaki (Anime/Fantasy) . . "Only Yesterday" ("Omohide poro poro") (1991) Directed by Isao Takahata (Anime/Drama/Romance) . . "Porco Rosso" (1992) Directed by Hayao Miyazaki (Anime/Adventure/Comedy) . . "Ocean Waves" ("Umi ga kikoeru") (1993) Directed by Tomomi Mochizuki (Anime/Drama/Romance)

#studio ghibli#hayao miyazaki#tomomi mochizuki#isao takahata#porco rosso#kiki's delivery service#grave of the fireflies#my neighbor totoro#ocean waves#only yesterday#Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind#laputa castle in the sky#cinema title cards#cinema#film#anime#fantasy

941 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Killer's Key (1967)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching Ghibli film as a sort of Japanese habit for the summertime, so I rent 5 minor movies!

26/7/2024

Every Japanese person should have an experience of watching Ghibli film on TV at least once in its lifetime. Nippon Television(日本テレビ), or Channel 4 in Japan, has constantly aired Ghibli movies in their night program called Friday road SHOW for more than 25 years. Especially, it tends to broadcast some of them in summer. That's why people who have lived in Japan for so long associate the Studio Ghibli with summer with great ease. Then, I've rented some DVDs as our sort of tradition and I'm expecting that I will be able to make the most of the summertime through this pastime.

*

"Only Yesterday(おもひでぽろぽろ)" directed by Isao Takahata(1991)

"Only Yesterday" follows a woman called Taeko across two different timelines; the director Takahata did well in expressing visually what is like exploring the gap between someone's past and present in mind by using color contrast as well as a rough background in the past sequence. Then, younger herself shows up around her like she follows and sticks to her everywhere she goes. This double-layered screen in animation can be reflective of a kind of universal phenomenon that memories will always be with you wherever you go.

I, actually, had watched this movie once on TV when I was young and since then, I've remembered the scene about menstruation experienced by girls in/at elementary school; because their experience was so close to mine, and also it used to be rare to see episodes about period in public at that time.

However, for this time, I found myself relating to and gravitating toward other aspects of this movie, which was mostly the present part, such as the procedure of dying with the safflower(Benibana), life in the countryside, and her introspective attitude to the past. Since I'm now 25, my viewpoint should differ from that of younger myself. In fact, I have a pile of memories to look back at and experiences to recall compared to a child. That is an adult, I've got convinced myself.

Again, this was also about what woman in Japan experiences as a girl/woman(I don't want to separate people by sex or gender, but most of Taeko's experiences seemed to be attributed to her gender), I assume. Even though her childhood was during the 1980s, or long before I was born and I spent my own childhood, there was no big difference between us. It means that the society has yet to change a lot in term of gender roles, which is sad, indeed.

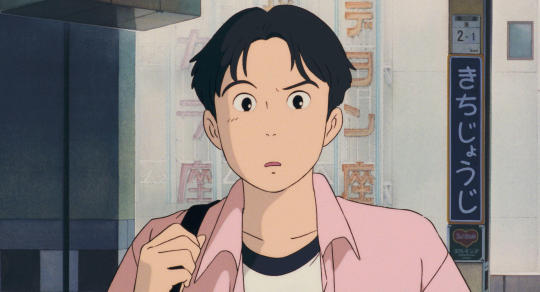

"Ocean Waves(海がきこえる)" directed by Tomomi Mochizuki(1993)

This is a 60 minute-long film adaptation made by younger artists at the Ghibli Studio and originally aimed for broadcasting but a theater. Nevertheless, I have never seen this on TV since I was born, and now it is only available on DVD and Blu-ray. So, I suppose that it's little known despite the New Media Age.

The story is all about reminiscence, as is "Only Yesterday". A man looked back at his high school days with a transfer girl before the reunion. He tells us about a series of events in the past not only from his viewpoint calmly but also in an objective way; that's why the film managed to show the wonders of meeting and separation on the globe and one theory that love can't always be explained.

I think that "distance" is a theme of this movie. It can help us to put things in perspective, especially we are stuck in something. Growing up, his classmate said that bumping into old familiar faces in another world could lead her to feel so relieved and comfortable that she rejoiced to see even one who she used to dislike. That resonated with me a lot, and I like this scene. Things change, people change, and feelings change. When I was young, I didn't think of such as good, but now I understand to the core.

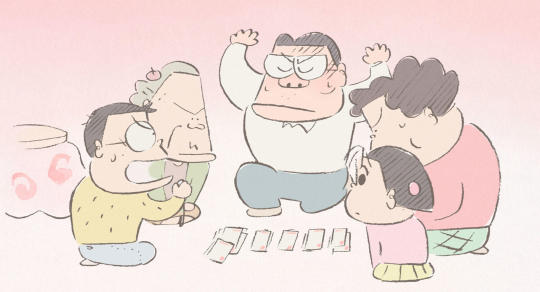

"My neighbors the Yamadas(ホーホケキョ となりの山田くん)" directed by Isao Takahata(1999)

The Yamadas seems a bit traditional but still be a familiar family structure in Japan, as far as I can see. So, I, in my mid-20s, could deeply relate to many scenes of everyday life in their family and remembered my childhood vividly. Yet, at the same time, I found it a bit stressful for me to see this father behave as the head of a family and embody "patriarchy", although I tried to keep in mind that the movie was released 25 years ago.

Having said that, I liked its character design and its atmosphere which a very delicate touch in illustration and cheerful music by Akiko Yano, who is one of my recent favorite musicians, create very much. As well as that, I appreciate the late Takahata's direction, which always depicts memory or the past well to the point where I'm tearing up; for instance, this stripped down paintings, I mean its faint touch can feel like reminiscence. How nostalgic it is!

*

I've rented two more DVDs: "ジブリの本棚"(Hayao's large book list), a documentary film, and "Studio Ghibli short film collection(from 1993 to 2016)".

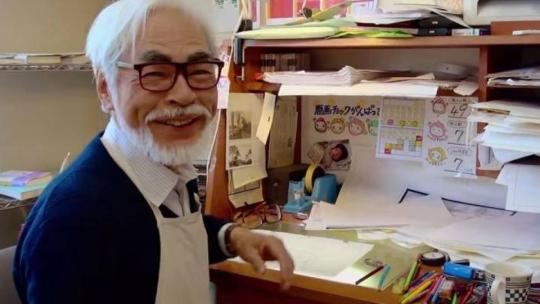

The former is all about worldwide children books, especially from the series of Iwanami Children books(岩波少年文庫)curated by a publisher Iwanami, and what Hayao Miyazaki as a creator had been inspired by. Then, he introduced some of the books on his list in detail and told anecdotes about behind the scenes of some films he made or his apprentice days in relation to children books. I liked this documentary in that director Miyazaki talked a lot enjoying himself and looked more interested than I've ever watched.

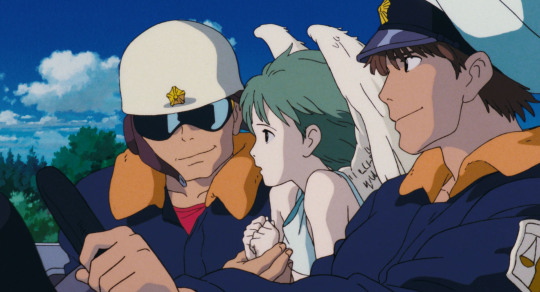

As for the latter, it was mostly dedicated to TV commercials made by the Ghibli Studio, but there was also a piece of art above named "On Your Mark" directed by Hayao Miyazaki, which was originally made as a music video with a storyline for its song by the J-POP duo CHAGE and ASKA. The story is that an angel is helped to escape from the authorities by two male officers set in the near future. It has a cyberpunk vibe, but somewhere peaceful in nature seemed like an ideal destination in this short film, which Miyazaki should like. Yet, personally, I'm not a fan of those kinds of stories, besides the song and its character design. He tends to depict young women as vulnerable and being rescued by men in the end, although they surely appear to have opinions, be confident, and independent.

#japan#studio ghibli#ghibli films#summer#movies#anime#documentary#hayao miyazaki#isao takahata#short film#dvd#tv broadcast#childhood memories#my neighbors the yamadas#ocean waves#feminist film theory#feminism#akiko yano#only yesterday

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cinema Jove rinde de nuevo culto a ‘Los dioses del anime’

El festival dedica una segunda entrega a la animación japonesa con un ciclo que contará con 19 títulos

València (03.05.21). Cinema Jove ofrecerá en su 36.ª edición, programada del 18 al 26 de junio, una segunda entrega del ciclo dedicado en 2019 a la animación japonesa. El Festival Internacional de Cine de València, organizado por el Institut Valencià de Cultura, ha seleccionado 19 títulos que ofrecen una mirada múltiple sobre el anime tanto en géneros como en narrativas.

Tras una primera entrega en la sala 7 del edificio Rialto, en la que se desbordaron todas las expectativas, el ciclo se alojará esta vez en la Filmoteca para disponer de un mayor aforo para los aficionados al anime y los curiosos pero no iniciados.

La premisa de esta sección paralela del festival es la variedad, con la presencia de autores más conocidos como Makoto Shinkai, cuya película El tiempo contigo fue elegida por Japón para representar al país en los Oscar. De Isao Takahata se presentará Goshu, el violonchelista (1982), una película temprana, anterior a la fundación del estudio Ghibli junto a Hayao Miyazaki, de quien además se han programado dos películas de culto, la medieval y mitológica La princesa Mononoke (1997) y la biografía histórica del creador del avión de combate Mitsubishi A6M Zero, El viento se levanta (2013), junto con otros nombres que no suenan tanto porque su obra no ha llegado al gran público en salas comerciales o por tratarse de clásicos.

A ese respecto destacan el corto restaurado The Spider and the Tulip (Kenzo Masaoka, 1943), realizado en plena II Guerra Mundial, y la pieza erótica Las mil y una noches (Eiichi Yamamoto, 1969), una pieza artística de los sesenta que conforma junto a Cleopatra (1970) y Belladonna of Sadness (1973), exhibida en la anterior entrega de Cinema Jove, la trilogía Animerama, ideada por el icónico Osamu Tezuka.

En esa distinción de posibilidades estéticas y argumentales destacan el largo Memories (1995), constituido por tres relatos de ciencia ficción dirigidos por otros tantos directores, Katsuhiro Ōtomo, Kōji Morimoto y Tensai Okamura, y Night on the Galactic Railroad (Gisaburo Sugii, 1985), una propuesta de contenido metafísico, “con un tipo de dibujo que no asociamos habitualmente al anime, como tampoco su narrativa”, destaca Madrid.

La adolescencia estará muy presente en el ciclo, con títulos como El caso de Hana y Alice (2015), precuela de una película de acción real realizada en animación rotoscópica con fondos de acuarela; Puedo escuchar el mar (Tomomi Mochizuki, 1993), un triángulo amoroso desarrollado por la nueva cantera del estudio Ghibli; Classmates (Shoko Nakamura, 2016), adscrita al género yaoi, que trata el romance homosexual; La chica que saltaba a través del tiempo, en la que el universo adolescente se entrecruza con la ciencia ficción; y Liz y el pájaro azul (Naoko Yamada, 2016), un relato ambientado en la banda de viento de un instituto femenino que es un spin-off de la serie televisiva Hibike! Euphonium.

Otra temática destacada es la del acompañamiento adulto a los niños en su paso a la edad adulta, como El niño y la bestia (Mamoru Hosoda, 2015), una aventura en un universo de animales antropomórficos que fue la primera película de animación en optar a la Concha de Oro en San Sebastián; Maquia, una historia de amor inmortal (Mari Okada, 2015), una trama antibélica protagonizada por una joven que no envejece y el niño que adopta; y La espada del extranjero (Masahiro Andō, 2007), que relata la historia de un niño que, en su huida de una tribu de guerreros, se encuentra con un ronin, un samurái sin dueño, que acepta protegerlo.

En esa distinción de posibilidades estéticas y argumentales destacan el largo Memories (1995), constituido por tres relatos de ciencia ficción dirigidos por otros tantos directores, Katsuhiro Ōtomo, Kōji Morimoto y Tensai Okamura, y Night on the Galactic Railroad (Gisaburo Sugii, 1985), una propuesta de contenido metafísico, “con un tipo de dibujo que no asociamos habitualmente al anime, como tampoco su narrativa”, destaca Madrid.

#Anime#Valencia#Cinema Jove#Makoto Shinkai#Isao Takahata#studio ghibli#hayao mizayaki#Osamu Tezuka#Shoko Nakamura#Naoko Yamada#Mamoru Hosoda#Mari Okada#Masahiro Andō#Gisaburo Sugii#Tomomi Mochizuki

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Thanksgiving, I am grateful for Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli movies, so I have ranked all of the studio’s directors and their respective bodies of work by order of my personal preference.

1. Hayao Miyazaki (A separate post for the movies.)

2. Isao Takahata The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013) I used to try to give this movie a more positive spin by concentrating on how strongly Kaguya cherishes life on earth and how she and her mother so yearn for another taste of it. But kinda like Grave of the Fireflies this is too tragic of a story! Overwhelmingly tragic. Nonetheless, it is so gorgeously animated and so powerful. It pains me to recall it, but whenever I do I also remember the sense of awe I feel every time I see it. The unshakable knowledge that you are in the presence of a masterpiece.

Only Yesterday (1991) Maybe the best showcase of Takahata’s deep sense of sympathy and humanity. A meditation on nostalgia, the passage of time, the myriad shapes of desire. A young woman’s delicately labyrinthine confrontation with her childhood and her future.

My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999) A perfect adaptation of a comic strip. A versatile, evocative animation style, endearing characters, impeccable comedic timing, breathtaking opening and ending sequences. My chief complaint is that I wanted to see a little more of Nonoko to balance out the attention that each of the other family members got.

Pom Poko (1994) Honestly, tanuki freak me out a bit lol. I’ve only seen this once. I’ll probably watch it again and properly reassess it one day, eventually.

Grave of the Fireflies (1988) Too sad. So unrelentingly sad! I’ve seen this once (at the end of my senior year of high school, my English teacher showed it to us) and I’m not sure I could ever watch it again. An exercise in eliciting sympathy for victims of horrible neglect and poverty, I’m not sure it needs to be watched more than once.

3. Yoshifumi Kondo Whisper of the Heart (1995) A touching, finely textured story of kids discovering passion and purpose in their lives. With an ending that dares you: will you share in their newfound courage and hope? or will you retreat to cynicism?

4. Tomomi Mochizuki Ocean Waves (1993) In rankings of Ghibli movies I’ve seen, this one tends to get put toward the bottom and I can understand why. It’s a small movie. At a glance it may even seem pedestrian. But I think it’s surprisingly subtle in its treatment of its characters’ emotions, as they make mistakes, mature, and gradually realize their feelings for each other. It’s a movie that can reveal fine wrinkles in its fabric if you open yourself up to it.

5. Hiroyuki Morita The Cat Returns (2002) A listless teenage girl gets herself transported to a cat world, gets saved by a dashing, heroic guy cat and ends up inspired by him to wake up earlier in the day, blend her own coffee, and stop having shallow crushes on boys. A cute movie. I like the ending credits song (Kaze ni Naru by Ayano Tsuji).

6. Hiromasa Yonebayashi When Marnie Was There (2014) A young girl has trouble making friends so her grandmother’s ghost hangs out with her. Honestly a tender portrait of the girl coming to terms with the dark and difficult corners of her family history and her self. Not a fan of its (strangely?) dramatic twists and turns though.

Arrietty (2010) I thought this was pretty boring, but it’s okay I guess.

7. Goro Miyazaki Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter (television series, 2014-2015) I haven’t seen this but it can’t be worse than the other two right?

From Up on Poppy Hill (2011) An overall sweet film of rich visual detail. It could’ve even been good if it didn’t *absolutely needlessly* make a specter of incest to drive the plot.

Tales from Earthsea (2006) I haven’t seen this in a while so my opinion might be a little different if I reassessed it, but from what I remember this was… bad. The story, the characters, the pacing… My guess is that Goro Miyazaki was taking a cue from his dad in adapting a western fantasy novel very loosely (and with a jarringly drastic ending). But it takes experience and vision to put together a *good* mess rather than just a plain old one.

8. Michaël Dudok de Wit The Red Turtle (2016) A man.... physically abuses a turtle,,,,, the turtle turns into a woman........ the man self-actualizes through having a family................

#isao takahata#yoshifumi kondo#hayao miyazaki#tomomi mochizuki#hiroyuki morita#hiromasa yonebayashi#goro miyazaki#watched and added red turtle#on movies#the tale of princess kaguya#only yesterday#my neighbors the yamadas#pom poko#grave of the fireflies#whisper of the heart#ocean waves#the cat returns#when marnie was there#arrietty#ronja the robber's daughter#from up on poppy hill#tales from earthsea#the red turtle

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You might be a Ghibli superfan, or maybe you’ve started working through the studio’s catalogue on Netflix.

Either way, I’m probably about to make you very angry with this ranking.

Here are all the Studio Ghibli movies RANKED.

#MovieADay#movie review#studio ghibli#isao takahata#hayao miyazaki#hiromasa yonebayashi#goro miyazaki#tomomi mochizuki#hiroyuki morita#yoshifumi kondo

0 notes

Text

The amazing universe of Hayao Miyasaki

Hayao Miyazaki is a Japanese film director and animator who is the founder of the animation studio ‘Studio Ghibli’ which is one of the most important studios in this field worldwide.

His films have a unique beauty, both in the animation, with extreme attention to detail, and in the story, focusing on nature, technology and applying a strong criticism of war. In addition, the heroes in his films are generally young women.

Since I was little I have always seen mostly anime with male protagonists, very sexualized women and little visibility, obviously there are exceptions, but for the most part that was the content that abounded. At the time it was not something that called my attention in a negative way, because it was something normal, until one day I became interested in watching films by Studios Ghibli, mostly by director Hayao Miyasaki and I think that changed my perspective towards women, even me being a woman.

In these movies you no longer saw the male teenage protagonist, with the woman of the group who was usually 'the supporter' or 'the love interest', but beyond that she wasn't the cool character that you knew could have an epic battle, and don't get me wrong, I'm still love of those anime, but being able to understand that women could be the protagonists of the stories, and not just women, girls, made me think that maybe I could do great things too.

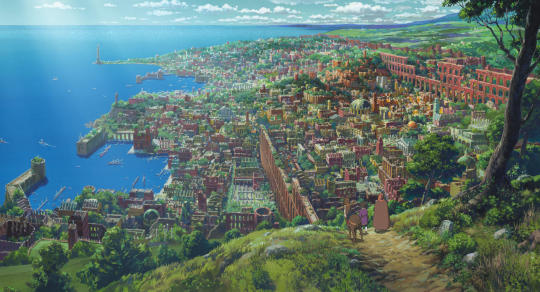

Another point that I find fascinating is the art and landscapes, which never cease to impress me, as they are sublime and exciting, showing the beauty of nature and cities where the solarpunk and steampunk currents predominate.

And finally the criticism of war. Since he grew up in the middle of the second war, Hayao Miyazaki is a pacifist, making it very clear in his films, showing how people and nature suffer from wars, destruction and the atrocities that humans are capable of doing and how the beauty of technology, in the wrong hands, becomes something horrifying.

It is for this and more, that I strongly recommend that you see the films of Studios Ghibli, not only those of Miyasaki, but also of other directors such as Isao Takahata, especially Grave of the Fireflies, and Tomomi Mochizuki.

- Camila Palma Caris.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t Watch Studio Ghibli Online

Castle in the Sky (1986, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

My Neighbor Totoro (1988, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

Kiki's Delivery Service (1989, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

Only Yesterday (1991, dir. Isao Takahata)

Porco Rosso (1992, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

Ocean Waves (1993, dir. Tomomi Mochizuki)

Pom Poko (1994, dir. Isao Takahata)

Whisper of the Heart (1995, dir. Yoshifumi Kondō)

Princess Mononoke (1997, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999, dir. Isao Takahata)

Spirited Away (2001, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

The Cat Returns (2002, dir. Hiroyuki Morita)

Howl's Moving Castle (2004, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

Tales from Earthsea (2006, dir. Gorō Miyazaki)

Ponyo (2008, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

The Secret World of Arrietty (2010, dir. Hiromasa Yonebayashi)

From Up on Poppy Hill (2011, dir. Gorō Miyazaki)

The Wind Rises (2013, dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013, dir. Isao Takahata)

When Marnie Was There (2014, dir. Hiromasa Yonebayashi)

#ghibli films#ghibli#studio ghibli#anime#totoro#ghibli studio#spirited away#hayao miyazaki#art#howls moving castle#miyazaki#watch online#watch online anime#streaming#freebies#free#tumblr#tumblrpost

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ghibli Goes Digital.

We celebrate the explosion in Studio Ghibli activity on Letterboxd with Michael Leader and Jake Cunningham from the Ghibliotheque podcast.

LISTEN NOW: David Jenkins (Little White Lies), Tasha Robinson (Polygon) and Adam Kempenaar (Filmspotting) nominate their most magical Studio Ghibli moments in this new episode of The Letterboxd Show.

For all the ways that the coronavirus pandemic has dramatically altered the film industry, one coincidence that’s worked out extremely well for Studio Ghibli fans old and new is the roll-out of 21 of the famed studio’s films on streaming services.

It started in February for Netflix subscribers outside Japan and North America. Then in late May, HBO Max launched in the US with the Ghibli films as part of its offering. Finally, Canada got its turn with twenty titles available on Netflix right now, and The Wind Rises coming on August 1. For film lovers sheltering in place, the timing is as soothing as a nap on a Totoro’s belly; as wondrous as a Takahata sunset.

株式会社スタジオジブリ (Studio Ghibli) was founded in 1985 by directors Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki, and producer Toshio Suzuki, upon the success of Miyazaki-san’s 1984 feature, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Huge acclaim, an Academy Award, and growing fandom followed, but the studio has long shied away from making its catalog available for digital consumption, preferring the films to occupy a larger canvas.

And then, all of a sudden, Suzuki-san announced the digital streaming plan—starting with the whole catalog being made available to own (via download) last December. “We’ve listened to our fans,” Suzuki-san said at the time. “In this day and age, there are various great ways a film can reach audiences.” This turn of events has been a very big deal—both for long-time fans and Ghibli newbies—and we’ve run the numbers to prove it:

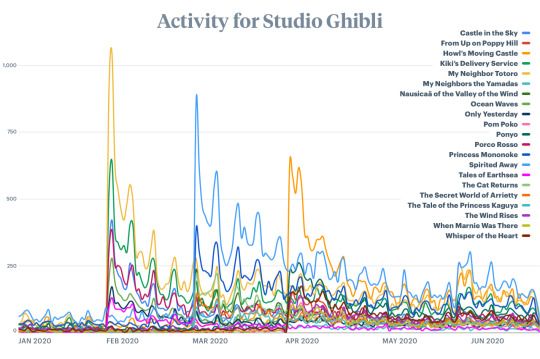

The above chart shows the daily number of entries logged on Letterboxd for each of the Ghibli films, and clearly depicts the February, March, April and late May spikes as groups of titles were released to the two aforementioned streaming platforms (and mini spikes coinciding with weekend watches).

The Ghibli films included in the streaming deals stretch over four decades of the studio’s output, and include big-hitters like the Oscar-winning Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, Howl’s Moving Castle and the whole-family favorite My Neighbor Totoro. All of those films appear in the Official Letterboxd Top 250; Totoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service also made it onto a list of Letterboxd members’ top twenty favorite comfort films in a recent survey.

To get a sense of what this all means, we went to Letterboxd members Jake Cunningham and Michael Leader, hosts of Ghibliotheque, a podcast dedicated to the studio’s filmography, about the Netflix deal (“none of us could quite believe it when it happened”) and the clues Ghibli films offer us for how to have adventures inside our own homes.

Earlier in the pandemic, when we were all figuring out how to stay home, you hosted a joyous My Neighbor Totoro watch-along. What is it about the fuzzy, mythical creatures that feels so helpful right now? Michael Leader: In some ways, the world’s mum is in hospital right now. We’re all working from home. There’s the bit halfway through the film where the dad is trying to get on with his work in the study, and [his daughter] Mei is coming up and putting little flowers on his desk. That’s what everyone is doing right now, is trying to get on with their work whilst their kids are milling about, full of imagination and adventures.

With Totoro, I go back to a guest we had on the show, Helen McCarthy, who wrote the book about Miyazaki. And she described Totoro as something like “kindness and acceptance made furry”, and that’s really what it is. The idea of this creature being there for you, coming out of the surroundings that you live in, allowing you to not only come into a new space that you’re maybe scared of going into, but also dealing with tricky situations that you’re in.

You’re both deeply embedded in the London film scene, but the dynamic of your Ghibliotheque podcast is that Michael is the long-time Ghibliophile, while Jake is the novice. How did that come about? Jake Cunningham: Michael and I actually work together, and it came up that I hadn’t seen any of the films and then it happened to come up that Michael was one of the UK experts of these films and was having a go at me for never having watched any. This was the perfect opportunity to work on something with each other, and my ignorance has finally paid off, because all I need to do is watch the film and then I get this amazing history lesson.

Jake Cunningham with his ‘Only Yesterday’ poster, and with Michael Leader at the Ghibli Museum.

ML: It was really fun for me, because by that point—this is nearly two years ago now—I’d been writing about Ghibli on and off for almost a decade. There aren’t really many outlets to write about anime, Ghibli and animation in particular, in the monthly film magazines. Jake is the novice we can take through the library and invite people to join us on that journey. We have listeners who are so engaged, sending us comments every week. They had no idea how deep the rabbit hole goes.

That’s something that was personally for me quite important about the show. We want to show that this is one of the few studios that has ten five-star films. They had this amazing streak from the late 80s through the 2000s, just innovating on every film at the highest level, with multiple voices working in their own different worlds. We’ve really managed to show this whole world and invite people into it.

What did you make of the Netlix flex, and the subsequent explosion in Letterboxd activity around Ghibli films? JC: The graph is amazing! I was expecting a boost but not so big. They must be very happy with how well the deal has done for them. I think it’s a good place for Ghibli for sure. I want so many other people to be in the position that I was in two years ago. It is a whole world of pleasure to delve into for audiences.

I did think it was so funny that they spent fifteen years going “We’re never going to be streaming, this is never going to happen, stop asking us”, and then out of nowhere the announcement that they’re going to be online in two weeks! I think none of us could quite believe it when it happened, but what it’s meant is people are going back to the start of the podcast and listening along, because they can finally watch the films that they hadn’t seen before.

And it’s so exciting that people might watch Totoro, or Spirited Away, or Howl’s Moving Castle, these bigger tentpole releases, and that’s going to change their algorithm and they’re going to get presented with Isao Takahata’s My Neighbors the Yamadas or Tomomi Mochizuki’s Ocean Waves. The under-appreciated Ghiblis are suddenly going to get dragged out again.

ML: I’m really excited about it. It’s an interesting thing: it shines a light on what I think is more of a fandom problem, where something becomes rarified or scarce or special to a certain subculture, and that becomes part of its appeal. Sort of ‘Oh, Miyazaki doesn’t believe in streaming, he will never sell out’, and going on about how Netflix somehow cheapens it—but really they are completely accessible films that should be available in a mass market.

Also, and this is something we wanted to tease out in the podcast, they are business savvy. They’re not crazy geniuses who live in wooden shacks in the middle of nowhere. They’re a real company that needs to keep the lights on. There are so many ways to speculate on what this deal means. I think on the one hand they were happy because in the Japanese market they sell enough merchandise, they have a real home entertainment churn going, that they never really needed to do an international release.

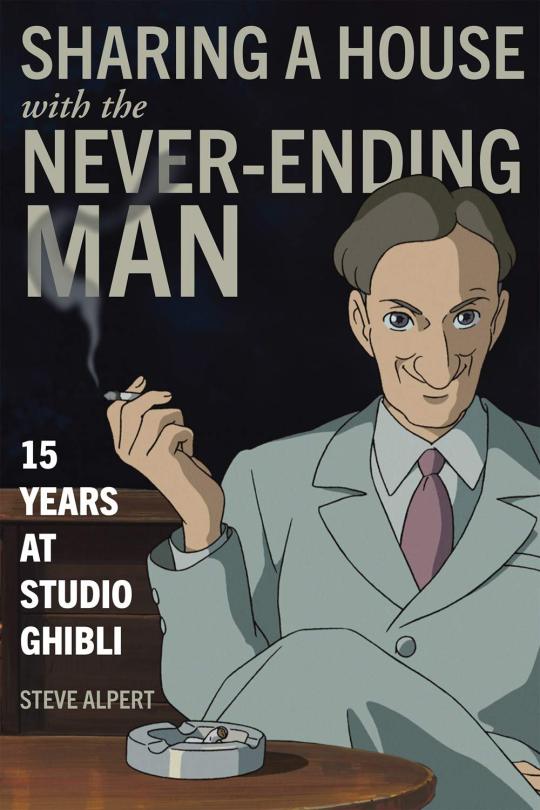

There’s a really good book just out by Steve Alpert, who was their first international division lead. He was hired in the 90s to sort out their penetration into western Europe and America. Before the 90s, there were a couple of home entertainment releases and small theatrical runs, but they suddenly saw the business benefits in going global. In some ways I’m very happy for it because it’s a business deal that makes these films more available. They’ll always be special because they’re great films.

JC: The films streaming is extremely exciting, but something that’s gone under the radar a bit is that all of the music is now on Spotify. There are some of Ghibli’s shorts that you can only watch in the museum in Japan, but the scores for those films are now on Spotify, and everything is there. After having the melodies of some of these stuck in my head for months and months, you can finally actually go and deal with the earworm once and for all.

Is it possible for you to sum up for us the thematic essence of Ghibli films, and make a case for why Letterboxd members should introduce their children to the catalog? For me, in the context of the pandemic, it’s the corn on the window-sill in My Neighbor Totoro: the idea of presence despite distance; connection through gesture; the significance of nature. JC: It’s a lot to do with leaving things in an ambiguous space. Having kids watch things where there’s not a binary answer to everything. The studio moved away from the earlier films where a villain is a villain. In Spirited Away and Howl’s Moving Castle, it’s less clear what a ‘bad person’ is and what a ‘good person’ is. I think it’s important that kids are gonna see that. Even with something like Kiki’s Delivery Service, on the surface it’s one of their simpler films. Kiki goes on an amazing journey and she meets amazing people, and at the end, she learns about who she is and what she can do. I think in a Western kids’ film that would be the end note. But there’s that note at the end of the film where she says that she still feels sad, and she still feels homesick, but that’s okay and that’s part of being alive.

ML: I think Miyazaki’s real magic touch across his films is that he’s able to really look at the world through children’s eyes. I’m not the first person to say that. It tends to be one of the first things that people say about him. The magical things about My Neighbor Totoro are when they’re just walking through the house, cleaning the house, cooking together. And for Kiki, when she gets her own [apartment], sweeps up and cooks herself pancakes. It is just as much about the magic of the everyday, about the world that you can see around you, within the four walls of the home.

JC: Now that you say that, I’m thinking about Ponyo, a key scene where the storm is hitting, and Sosuke and Ponyo and Sosuke’s mum just hunker down in their house and they have a generator going and they make instant ramen noodles, and the mum slips in little bits of ham. They also have some honey tea. Even though he’s a fantasy filmmaker, and he makes grand statements about geopolitical situations, these are the sequences now which will play most poignantly to people.

ML: Ghibli offers escapism, right now.

We got a glimpse of the next Ghibli film, Gorō Miyazaki’s fully-CG Aya and the Witch (see picture below), via the online version of the recent Annecy International Animated Film Festival. What are your thoughts? JC: Regarding the new images, I’m not as petrified as some fans have been. On the podcast I’ve mounted my defence for Gorō’s Tales From Earthsea, which is very much the black sheep of the family, and I don’t think I’d be doing him justice after that if I didn’t stand in his corner on this one as well. Until we see the style in motion, I think it’s unfair to judge, but it certainly is… different.

Jake, are you now a true Ghibliophile, or are you still just following along with what Michael’s got you into? JC: I would say I am now. I could definitely bore people in conversations with production stories! A lot of people will, I’m sure, have seen a lot of the films, but doing the podcast is the only thing that would have made me watch all of them.

Michael, how proud are you of this achievement? ML: Turning Jake into a new Ghibiliofile is really something. When we went to Japan in November last year—we managed to find change down the back of the sofa, and take the team out and visit the museum, visit Studio Ponoc, who are the spin-off studio founded by veterans from Ghibli—the thing that made me most proud was seeing how excited the rest of the team were. I think just out of shot of Jake’s webcam is a poster of Only Yesterday that he bought in Japan. It’s the only thing he wanted to find, was an original 1991 poster of that. There’s a picture of Jake just absolutely beaming with this poster.

Related content

Our Letterboxd Show Ghibli Magic Moments episode, with Tasha Robinson, David Jenkins and Adam Kempenaar.

Little White Lies editor David Jenkins’ Letterboxd review of My Neighbor Totoro.

The Official Letterboxd Top 250

Letterboxd members’ favorite comfort films.

#studio ghibli#ghibli#Isao takahata#Hayao miyazaki#my neighbour totoro#spirited away#Kiki's delivery service#howl's moving castle#anime#Japanese animation#Toshio suzuki#Jake cunningham#Michael leader#ghibliotheque#ghibliofile#letterboxd#netflix#hbo max

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daiki!

It's been a while since I drew my goober bean who gave me the obsession of strawberries ehe.

Anyways Daiki art WOOOO!!!

-------⭐

Wanna support me?

🍓 My commission are open! Check it out here

🍓 You can also support me via Patreon, Ko-Fi, Redbubble

#my art#ocs#digital art#art#my ocs#artist#digital artist#original character#artists on tumblr#oc#Daiki Tomomi#Tomomi Daiki#Tomomi Isao#isao family#Isao Tomomi#artyboneocs

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

✧ New Video: {Oc} Passionate Flames ✧

[Dec 2022] New vid is out called Passionate Flames! Why is it called that? Because the Isao family are known for their firey passion! This artwork is almost like Daiki finding their origin as an Isao rather than a Daiki.

As always, if you like the video, consider subscribing!

youtube

#2022 art#2022 video#Youtube#Daiki Tomomi#Tomomi Daiki#Isao Tomomi#Tomomi Isao#Isao family#artyboneocs#ocs#original characters#my ocs#my characters#oc art#original character art#timelaspe#speedpaint#art timelapse#my video#youtube video

0 notes

Link

Hayao Miyazaki y su hijo Gorō, preparan dos nuevas películas para Studio Ghibli. Se trata de dos largometrajes con los que el estudio celebrará su vuelta a la animación después de cinco años desde el estreno de su última película ‘El viento se levanta’ en 2013.

Aunque no ha habido anuncio oficial por parte de Toshio Suzuki, productor del Studio Ghibli y encargado de anunciar los largometrajes que están en producción y su fecha de estreno. Sí que lo ha anunciado Vincent Maraval, fundador y director de ventas internacionales de Wild Bunch, compañía encargada de distribuir los títulos de Ghibli en Europa.

Los films a los que hace referencia son: ‘Kimitachi wa do ikuru ka’ (¿Cómo vives?), película que estará inspirada en la novela homónima de Genzaburo Yoshino de 1937, cuyo estreno en Japón se espera para 2020 o 2021, y una nueva película al mando de Gorō Miyazaki, quien anteriormente había dirigido para el estudio ‘Cuentos de Terramar’, y ‘La colina de las amapolas’.

Después del retiro oficial en 2013 de Hayao Miyazaki, en 2017 regresó a la animación con la creación de su primer cortometraje, realizado íntegramente en digital, ‘Kemushi no Boro’ (Boro, la oruga). Sin embargo, ‘Kimitachi wa do ikuru ka’ será el décimo segundo largometraje del animador nipón y el último que dirigirá, ya que tal como declaraba Toshio Suzuki: "Miyazaki está haciendo la nueva película para su nieto. Es su forma de decirle: 'El abuelo se está moviendo hacia el otro mundo, pero deja atrás esta película'".

El regreso de Hayao Miyazaki y la nueva película que dirigirá su hijo supondrán un regreso muy esperado para los seguidores del Studio Ghibli, que desde su creación en junio de 1985 por Isao Takahata (fallecido el año pasado) y Hayao Miyazaki, marcó un antes y un después en el cine de animación japonesa.

Aunque Hayao Miyazaki siempre tendrá un papel más protagonista dentro del Studio Ghibli, ya que es considerado por algunas personas como el “Walt Disney japonés”, no hay que olvidar al resto de directores como Isao Takahata, que llevó a cabo series tan míticas como Heidi, Marco, o la risueña Ana de las tejas Verdes, Hiroyuki Morita, Hiromasa Yonebayashi,Tomomi Mochizuki o Yoshfumi Kondo.

Desde sus inicios en 1984, el Studio Ghibli ha realizado un total de 22 películas de las cuales cuatro de ellas han sido nominadas a los Oscar como mejor película de animación, y solo una, ‘El viaje de Chihiro’, obtuvo la estatuilla dorada en 2002, además de ganar el Oso de Oro de Berlín.

Las películas de animación japonesa, no solo las del Studio Ghibli, viven una época dorada porque no solo “arrasan” en Japón, sino en medio mundo. Centrándome en las películas de Ghibli, a mi parecer, son una obra de arte por varias razones: porque el propio estudio defiende la elaboración de las películas dibujadas a mano; con lápiz y papel, por los valores tan profundos y críticos que transmite, y porque la manera de hacerlo es mágica.

‘El Viaje de Chihiro’, ‘La princesa Mononoke’, ‘El castillo ambulante’, ‘Nicky, la aprendiz de bruja’, ‘Mi vecino Totoro’, ‘La colina de las amapolas’, ‘El castillo en el cielo’… es difícil elegir una favorita ,sin embargo, aunque es un cliché, ‘El viaje de Chihiro’ se lleva la palma. Y es que hasta ha sabido encandilar e influir a Steven Spielberg, ya que una buena película de animación, cautiva y remueve sentimientos porque antes de ser adultos todos hemos sido alguna vez niños.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NOTE: Despite the fact Ocean Waves was originally released on Nippon TV, it debuted as a theatrical film in the United States in 2016. As per the rules I set out for this blog, it will be treated as a theatrical film.

Ocean Waves (1993, Japan)

The operations of Studio Ghibli are unusual for your typical Japanese anime studio. In an industry where employee burnout and turnover is high, Ghibli’s founders have always wanted to retain their young, promising talents. Their results have been mixed, but are markedly better than any other studio working in anime features. Before the temporary shuttering of the feature animation department, the first major occurrence of significant staff changes was when Sunao Katabuchi (2001′s Princess Arete, 2016′s In This Corner of the World) was demoted to assistant director on Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989).

Based on Saeko Himuro’s novel of the same name, Ocean Waves – also known as I Can Hear the Sea (a direct translation from the Japanese title) – was an attempt from Ghibli executives for their younger animators and staffers to display their creative prowess after Katabuchi’s unceremonious reassignment. Directed by Tomomi Mochizuki, a journeyman storyboard artist/director who had never worked for Ghibli before (or since) and whose directing experiences are more television- than cinema-based, this is a work for Studio Ghibli completionists only. The inexperienced animators and staffers should be proud of what they accomplished, even if that means it is one of the weakest films in the Ghibli canon.

Taku Morisaki is at a train station in Tokyo when he thinks he recognizes the woman on the opposite side of the platform. Ocean Waves then flashes back to two years earlier to his high school days in somewhat-rural Kôchi (on the island of Shikoku and the capital of Kôchi prefecture). We learn that the woman on the other side of the platform was Rikaku Muto, a transfer student from Tokyo who he met through his best friend, Yutaka Matsuno. All three of them are in the same year. Ocean Waves is more episodic than your average Ghibli movie, and we see sequences of a school trip to Hawai’i – damn, what kind of high school can afford such a trip? – where Taku lends Rikaku some money which, for events that will probably leave you in disbelief, he will never get back. But using Taku’s money without paying back might not even be the most frustrating thing that Rikaku does to Taku. Amid of all this high school drama that trailblazes new territory for said drama, there is a love triangle between Taku, Rikaku, and Yutaku. Calling Ocean Waves a messy melodrama is being modest.

Studio Ghibli co-founders Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata maintained a hands-on, teacher-student relationship with the junior staffers at Studio Ghibli – these staffers would become the storyboard artists, colorists, art directors, screenwriters, producers and directors of future anime features within and outside the studio. Considering the contemporary setting of Ocean Waves, those who worked on this film were most influenced by Takahata’s Only Yesterday (1991). Indeed, Only Yesterday’s influence can be seen from Ocean Waves’ flashback structure (not as intricate as the earlier film) and its utilization of partially washed-out backgrounds to suggest the passage of time and the imperfections of adult memories (both films share Katsuya Kondô as their animation director). Regarding the backgrounds in Ocean Waves, the white-washing is not as emphatic as the flashbacks in Only Yesterday. But compared to Only Yesterday, Ocean Waves’ flashbacks are not reaching as far back in the past; thus, the whiteness of the backgrounds in the later film are less impressionistic, emotional than in Takahata’s.

But just because the young staffers successfully studied Only Yesterday’s artistry does not mean that the decision to whiten the backgrounds exactly helps the film – especially when paired with a screenplay written by Keiko Niwa (credited as “Kaori Nakamura”; Niwa provided screenplays for 2010′s Arrietty, 2011′s From Up on Poppy Hill, and 2014′s When Marnie Was There) that has severe pacing problems and has problems connecting the audience with the characters. Only Yesterday’s screenplay connected a young adult named Taeko to her elementary school self, that some of the strands of Taeko’s childhood are reflected in how she carries herself every day – empowering the animation style I have described. When Ocean Waves breaks from the flashback in its final minutes, it is too difficult to trace how present-day Taku has changed from a few years earlier and what about him has stayed the same. As a result, the formula replicated in Ocean Waves that was used in Only Yesterday – though superficially mimicked in Ocean Waves – never connects to the potential storytelling and thematic elements that it should.

If Taku’s character development makes little sense by the conclusion, his best friend Yutaka almost becomes an afterthought past the halfway mark, and Rikako is always erratic, oftentimes infuriating. Where Taku almost becomes a protagonist-as-witness, Rikako is the one pushing the story along to areas that audiences might not be comfortable with. She is combative, deceptive, selfish. Her parents have just divorced, but that might not be why she acts the way she acts (Ocean Waves gives passing suggestions, but they never develop into anything meaningful) What surprised me the most while watching Ocean Waves for the first time is that I could partially understand how Taku and Yutaka could still harbor feelings for Rikako despite her verbal and, in one scene, physical derision. The boys’ behavior reminded me of my middle school self – complete with my youthful, albeit hopeless optimism that someone who I liked but held me in silent contempt might change and return my feelings. But Taku and Yutaka’s feelings for Rikako exist on a more dramatic, romanticized basis which feels undeserved and inexplicable by the time the credits roll.

Ocean Waves asks the viewer the relive the awkwardness and irrationality of one’s teenage years. With the narrative’s incomplete, sometimes nonsensical character developments, there just seems too little of interest in our three main characters to care too much. Rikako’s behavior just becomes too exploitative and inconsistent to understand – perhaps it would make more sense if Ocean Waves was told through her best friend Yumi, another classmate who doesn’t have a crush on her, or Rikako herself. Through the frames of Taku and Yutaka, there is some objectification of Rikako that prevents all three of them from being likable.

Composer Shigeru Nagata’s score is simplistic, almost inappropriately comical at times. With a limited budget, restricted instrumentation, and a languorous end theme, there is nothing here, musically, to challenge Joe Hisaishi’s lesser compositions.

Mochizuki’s film, intended to cost a pittance and be completed rapidly, instead resulted in a ballooning budget and production overruns. It is not a great movie, but it is a laboratory of experimentation for the younger Ghibli staffers and should be valued as such. Ocean Waves was released last December in North American limited release, and received middling reviews. The film’s Japanese reception is something of a mystery as I am writing this, as I have not been able to find any free, English-language sources confirming how Japanese audiences might have reacted to Ocean Waves and whether that has changed over time.

Some of the most humanistic films ever made have emerged from Japan; some from Studio Ghibli itself. Those films have helped viewers – young and old, Japanese and otherwise – realize repressed anxieties, remind us of the small triumphs that exist during times of suffering, and show us characters with the dignity and grace to attempt an understanding of others. Ocean Waves is itself part of that tradition, but as a sort of training ground film with just too many screenwriting snags, its impact is dulled.

My rating: 6/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Ocean Waves#I Can Hear the Sea#Tomomi Mochizuki#Studio Ghibli#Keiko Niwa#Katsuya Kondo#Nozomu Takahashi#Toshio Suzuki#Seiji Okuda#Shigeru Nagata#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Filmografía: Todas las películas de Studio Ghibli

Filmografía: Todas las películas de Studio Ghibli https://ift.tt/2H0P4OR

(Kaze no tani no Naushika / 風の谷のナウシカ / Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 11 Marzo 1984

Estreno en España: 7 Mayo 2010 (cines) / 30 Junio 2010 (DVD) / 24 Noviembre 2010 (Blu-ray) / 14 Mayo 2014 (reedición Deluxe) / 23 Noviembre 2016 (reedición Deluxe)

Duración: 1 hora y 56 minutos

Basada en el 1er tomo del manga homónimo dibujado por el propio Miyazaki.

El castillo en el cielo (1986)

(Tenkû no shiro Rapyuta / 天空の城ラピュタ / Laputa: Castle in the Sky).

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 2 Agosto 1986

Estreno en España: 15 Octubre 2003 (DVD) / Reedición: 24 Febrero 2010 (DVD) / 2 Noviembre 2011 (Blu-ray) / 29 Octubre 2014 (ed. Deluxe)

Duración: 2 horas y 4 minutos

Su idea parte de las islas flotantes relatadas por Jonathan Swift en 'Gulliver'.

Mi vecino Totoro (1988)

(Tonari no Totoro / となりのトトロ / My neighbor Totoro)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 16 Abril 1988

Estreno en España: 30 Octubre 2009 (cines) / 9 Diciembre 2009 (DVD) / 30 Octubre 2012 (Blu-ray) / 30 Octubre 2013 (ed. Deluxe)

Duración: 1 hora y 26 minutos

Catalogada autobiográfica de la infancia de Miyazaki.

La tumba de las luciérnagas (1988)

(Hotaru no haka / 火垂るの墓 / Grave of the fireflies)

Dirigida y escrita por Isao Takahata.

Estreno original: 16 Abril 1988

Estreno en España: 24 Noviembre 2003 (DVD) / Reedición: 27 Agosto 2008 (DVD remasterizado) / 11 Diciembre 2012 (Blu-ray) / 2 julio 2014 (ed. coleccionista) / 11 Mayo 2016 (ed. Deluxe)

Duración: 1 hora y 28 minutos

Basada en la novela homónima de Akiyuki Nosaka.

Nicky, la aprendiz de bruja (1989)

(Majo no takkyûbin / 魔女の宅急便 / Kiki's Delivery Services / Kiki, entregas a domicilio)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 29 Julio 1989

Estreno en España: 14 Octubre 2003 (DVD) / Reedición: 24 Febrero 2010 (DVD) / 21 Mayo 2013 (Blu-ray) / 29 Octubre 2014 (ed. Deluxe)

Duración: 1 hora y 42 minutos

Disney cambió música y diálogos en su primera versión internacional.

Recuerdos del ayer (1991)

(Omohide poro poro / おもひでぽろぽろ / Only yesterday / Los recuerdos no se olvidan -no oficial-)

Dirigida y escrita por Isao Takahata.

Estreno original: 20 Julio 1991

Estreno en España: 5 Mayo 2010 (DVD)

Duración: 1 hora y 58 minutos

Basada en el manga de Hotaru Okamoto y Yûko Tone.

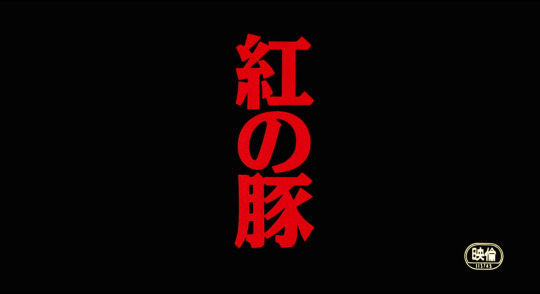

Porco Rosso (1992)

(Kurenai no buta / 紅の豚)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 18 Julio 1992

Estreno en España: 1 Septiembre 1994 (cines) / 25 Agosto 2010 (DVD) / 30 Octubre 2013 (Blu-ray) / 14 Mayo 2014 (ed. Deluxe) / 23 Noviembre 2016 (reedición Deluxe)

Duración: 1 hora y 34 minutos

Inicialmente iba a ser un corto para proyectar en los aviones comerciales.

Puedo escuchar el mar (1993)

(Umi ga kikoeru / 海がきこえる / Ocean waves / I can hear the sea)

Dirigida por Tomomi Mochizuki. Escrita por Kaori Nakamura.

Estreno original: 5 Mayo 1993 (TV)

Estreno en España: 29 Octubre 2008 (DVD)

Duración: 1 hora y 9 minutos

Único film para televisión de Ghibli y primero ajeno a Miyazaki y Takahata.

Pompoko (1994)

(Heisei Tanuki Gassen Pompoko / 平成狸合戦ぽんぽこ)

Dirigida y escrita por Isao Takahata.

Estreno original: 16 Julio 1994

Estreno en España: 9 Diciembre 2009 (DVD)

Duración: 1 hora y 59 minutos

Candidata de Japón a los premios Oscar de 1995.

Susurros del corazón (1995)

(Mimi wo sumaseba / 耳をすませば / Whisper of the heart / Si escuchas atentamente -no oficial-)

Dirigida por Yoshifumi Kondô. Escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 15 Julio 1995

Estreno en España: 28 Octubre 2009 (DVD) / 2 Mayo 2012 (Blu-ray) / 28 Octubre 2015 (ed. Deluxe)

Duración: 1 hora y 51 minutos

Su director Yoshifumi Kondô falleció en 1998 a causa de un aneurisma.

La princesa Mononoke (1997)

(Mononoke hime / もののけ姫 / Princess Mononoke)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 12 Julio 1997

Estreno en España: 30 Marzo 2000 (cines) / 14 Octubre 2003 (DVD) / Reedición: 24 Noviembre 2010 (DVD) / 14 Mayo 2014 (Blu-ray) / 11 Febrero 2015 (ed. Deluxe)

Duración: 2 horas y 14 minutos.

Batió todos los récords de coste y recaudación en Japón hasta su estreno.

Mis vecinos los Yamada (1999)

(Hôhokekyo Tonari no Yamada-kun / ホーホケキョとなりの山田くん / My neighbors the Yamadas)

Dirigida y escrita por Isao Takahata.

Estreno original: 17 Julio 1999

Estreno en España: 14 Mayo 2008 (DVD)

Duración: 1 hora y 44 minutos

Primera y única película íntegramente realizada por ordenador de Studio Ghibli.

El viaje de Chihiro (2001)

(Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi / 千と千尋の神隠し / Spirited away)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 20 Julio 2001

Estreno en España: 11 Octubre 2002 (cines) / 2 Abril 2003 (DVD) / Reedición: 28 Marzo 2007 (DVD) / Otoño 2018 (Blu-ray)

Duración: 2 horas y 5 minutos

Ganadora del Oso de Oro de Berlín y el Oscar de Hollywood.

Haru en el Reino de los Gatos (2002)

(Neko no ongaeshi / 猫の恩返し / The cat returns)

Dirigida por Hiroyuki Morita. Escrita por Reiko Yoshida.

Estreno original: 19 Julio 2002

Estreno en España: 29 Noviembre 2005 (DVD)

Duración: 1 hora y 15 minutos

Secuela libre de la novela escrita por la protagonista de 'Susurros del corazón'.

El castillo ambulante (2004)

(Hauru no ugoku shiro / ハウルの動く城 / Howl's Moving Castle / El increíble castillo vagabundo / El castillo errante de Howl)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 20 Noviembre 2004

Estreno en España: 3 Marzo 2006 (cines) / 13 Junio 2006 (DVD) / 2 Mayo 2012 (Blu-ray) / 30 Octubre 2013 (ed. Deluxe)

Duración: 1 hora y 59 minutos

Basada en la novela de Diana Wynne Jones y nominada a los Oscar 2005, estuvo a punto de dirigirla Mamoru Hosoda. Noticias relacionadas

Cuentos de Terramar (2006)

(Gedo senki / ゲド戦記 / Tales from Earthsea)

Dirigida y escrita por Gôro Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 29 Julio 2006

Estreno en España: 21 Diciembre 2007 (cines) / 12 Marzo 2008 (DVD) / 2 Mayo 2012 (Blu-ray)

Duración: 1 hora y 50 minutos

Basada en los libros de Ursula K. LeGuin y dirigida por el hijo de Hayao Miyazaki.

Ponyo en el acantilado (2008)

(Gake no ue no Ponyo / 崖の上のポニョ / Ponyo on the cliff by the sea / Ponyo y el secreto de la sirenita)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki.

Estreno original: 19 Julio 2008

Estreno en España: 24 Abril 2009 (cines) / 28 Octubre 2009 (DVD) / 27 Enero 2010 (Blu-ray) / 11 Febrero 2015 (ed. Deluxe)

Duración: 1 hora y 40 minutos

Totalmente dibujada a mano sin efectos digitales.

Arrietty y el mundo de los diminutos (2010)

(Karigurashi no Arrietty / 借りぐらしのアリエッティ / The Borrower Arrietty / Arrietty, la que toma prestado -traducción literal-)

Dirigida por Hiromasa Yonebayashi. Escrita por Hayao Miyazaki y Keiko Niwa.

Estreno original: 17 Julio 2010

Estreno en España: 16 Septiembre 2011 (cines) / 18 Enero 2012 (DVD y Blu-ray)

Duración: 1 hora y 34 minutos

Basada en la novela de 1952 'Los Borrowers' de Mary Norton.

Noticias relacionadas Crítica

La colina de las amapolas (2011)

(Kokuriko-zaka Kara / コクリコ坂から / From Up on Poppy Hill / Desde la colina de las amapolas -traducción literal-)

Dirigida por Gôro Miyazaki y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki y Keiko Niwa.

Estreno original: 16 Julio 2011

Estreno en España: Sin fecha

Duración: 1 hora y 31 minutos

Basada en el shôjo manga del mismo nombre publicado en 1980.

El viento se levanta (2013)

(Kaze Tachinu / 風が上昇 / The Wind Rises / Se levanta el viento)

Dirigida y escrita por Hayao Miyazaki

Estreno original: 20 Julio 2013

Estreno en España: 25 Abril 2014 / 26 Septiembre 2014 (DVD y Blu-ray)

Duración: 2 horas y 6 minutos

Basada en la autobiografía del diseñador de aviones caza de la II Guerra Mundial, Jiro Horikoshi; y la novela de Tatsuo Hori.

El cuento de la Princesa Kaguya (2013)

(Kaguya-hime no Monogatari / かぐや姫の物語 / The Tale of the Princess Kaguya)

Dirigida y escrita por Isao Takahata. Escrita también por Riko Sakaguchi

Estreno original: 23 Noviembre 2013

Estreno en España: 18 Marzo 2016 (cines) / 20 Julio 2016 (DVD/BD)

Duración: 2 horas y 17 minutos

Basada en la famosa leyenda tradicional japonesa de El cortador de bambú.

El recuerdo de Marnie (2014)

(Omoide no Marnie / 思い出のマーニー / When Marnie Was There / Cuando Marnie estuvo allí -del inglés-)

Dirigida y escrita por Hiromasa Yonebayashi. Escrita también por Keiko Niwa y Masashi Ando.

Estreno original: 19 Julio 2014

Estreno en España: 18 Marzo 2016 (cines) / 13 Julio 2016 (DVD/BD)

Duración: 1 hora y 43 minutos

Basada en la novela del mismo nombre de Joan G. Robinson.

Sanzoku no Musume Ronja Serie de TV (2014)

( 山賊の娘ローニャ / Ronja, the Robber's Daughter / Ronja, la hija del bandolero)

Dirigida por Goro Miyazaki. Escrita por Hiroyuki Kawasaki.

Estreno original: 10 Octubre 2014 en la cadena NHK

Estreno en España: Diciembre 2016 (TV / Movistar+)

Duración: 25 minutos por episodio / 26 episodios

Primera serie de televisión producida por Studio Ghibli, basada en la novela de Astrid Lindgren

___________________________________________________________________________

MÁS FILMOGRAFÍA...

https://ift.tt/2H2EAP7 via August 11, 2019 at 05:09PM

1 note

·

View note