#The siege of Tyre by Alexander

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Alexander the Great's conquest of Tyre

View On WordPress

#Alexander fhe Great#Ancient times#Bible#Egypt#Events#History#Issuus#Lebabon#Life#Listen#Macedonia#Military#Millitary#Naval warfare#Persia#Siege&039;#Sin#Tyre

0 notes

Photo

Alexander's Siege of Tyre, 332 BCE

After defeating Darius III at the battle of Issus in November 333 BCE, Alexander marched his army (about 35,000-40,000 strong) into Phoenicia, where he received the capitulation of Byblus and Sidon. Tyrian envoys met with Alexander whilst he was on the march, declaring their intent to honour his wishes.

Causes of the Siege

Alexander's request was simple: he wished to sacrifice to Heracles in Tyre. (The Phoenician god Melqart was roughly the equivalent of the Greek Heracles.) The Tyrian's recognised this as a Macedonian ploy to occupy the city and refused, saying instead that Alexander was welcome to sacrifice to Heracles in old Tyre, which was built upon the mainland. Old Tyre held no strategic importance - it was undefended and the Tyrian navy was stationed in the harbours of new Tyre.

The Tyrian refusal to capitulate to Alexander's wishes was tantamount to a declaration of war. But, despite the youthful Alexander's growing reputation, the Tyrians had every reason to be confident. In addition to a powerful navy and mercenary army, their city lay roughly half a mile (0.8 km) offshore, and, according to the account of the historian Arrian, the walls facing the landward side towered to an impressive 150 ft (46m) in height. Whether they actually stood that high is doubtful and open to debate, but even so, the defences of Tyre were formidable and had withstood a number of mighty sieges in the past. The Tyrians began their preparations and evacuated most of the women and children to their colony at Carthage, leaving behind perhaps 40,000 people. Carthage also promised to send more ships and soldiers.

Alexander was aware of Tyre's supposed impregnability and convened a council of war, explaining to his generals the vital importance of securing all Phoenician cities before advancing on Egypt. Tyre was a stronghold for the Persian fleet and could not be left behind to threaten Alexander's rear. In a last-ditch attempt to prevent a long and exhaustive siege, he despatched heralds to Tyre demanding their surrender, but the Macedonian's were executed and their bodies hurled into the sea.

Continue reading...

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shrike pt. 1 - words hung above but never would form

definition. male shrikes are known for their habit of catching insects and small vertebrates and impaling them on thorns

König x high school sweetheart reader

2nd person, gender neutral reader for now but reader is afab and referred to as a girl, reader is Austrian/has lived in Austria and speaks German for most of the story, romance, pining, friends to lovers, reader's nickname is Thorn, König's first name is Alexander

4.8k words

tw: bullying, brief mention of cheating and domestic abuse (not explicit, mentions of violence, and not done by König), mention of terrorism, suicidal thoughts

[NEXT]

based on this post by @ceilidho, who gave me permission to write this! many thanks <3

this post is dedicated to @papaver-decervicatus, who I am so proud of for finishing chapter 4 of her fic cat/mouse/den (which I highly recommend) and eating NO glass in the process. her headcanons for König have had a huge influence on me, and while there are some differences between julius and alexander, I absolutely must thank Caedis for her wonderful portrayal of König.

and of course, to @danibee33, for fueling my König brainrot. without you, I probably would not have returned to writing <33

disclaimer, I am not Austrian, I do not speak German, so if there's anything that needs correcting, please do reach out!

You admit, you’ve always had an affinity for protecting the weak.

When you were twelve, a bird slammed headlong into your bedroom window. The poor thing had avoided snapping its own neck but was certainly in no condition to fly. You’d bolted out of your childhood home to check on it, but by the time you arrived, a huge grey tomcat was prowling, sitting back on his haunches and ready to pounce. You generally liked cats, but this one was a mean old stray, and you’d always been frightened to go near him.

Without hesitation, you had shoved the cat aside, spitting and yowling, and taken the little bird into your hands.

It took a few days to nurse back to health, and you still remember the day you released it back into nature. It was worth the long scratch down your arm, pride swelling in your heart as it spread its wings and flew into a vivid blue sky. You remember it even now: a charming little gray bird, a streak of black coloring over its eyes. A shrike, your mother had identified it as.

People are no different than animals, sometimes. People can be cornered, battered, and bruised as well. You recognize the broken hunch of the bird you rescued in the boy sitting by himself at lunch time. His shoulders curl inwards with a desperate need to go unnoticed. You’ve seen him around: he’s not in any of your classes, but your classes always seem to end up in the same hallways, so you pass each other all the time.

He jumps a little as you slide into the seat next to him, shrinking away from you in a way that breaks your heart. “Hey.”

No response. You offer your name, but he seems reluctant to divulge his own.

“Is it okay if I sit here?”

He shrugs.

“Thanks. I don’t know anybody at this school, so it’s nice to have a friend.”

“…friend?” He has a nice voice, you think. Timid, but almost sweet.

“Well, if you’ll let me call you one.”

“…”

And so begins your friendship with König.

I was housed by your warmth Thus transformed By your grounded and giving And darkening scorn

You didn’t call him that in high school, of course. You wouldn’t know that name until much, much later. It takes a while to coax him out of his shell, cajoling him that you can’t call him “green-eyed boy” forever, to get his name.

“Alexander is a very good name,” you assure him, and he seems pleased. He’s still hesitant to speak to you at all, but that’s just fine by you. You’ve got plenty to talk about, anyway.

“You know, I read this book about Alexander the Great. There’s this crazy story about one of his battles at a city called Tyre. He was laying siege to it after a misunderstanding with their king…” you chatter on, unaware of the intense stare from the boy sitting next to you.

“…ordinarily, sieging an island is pretty difficult, but you won’t believe what he did,” you rattle on. “He—”

“He built his own bridge,” Alexander says, so quietly you almost don’t hear him at first. You look at him in surprise.

“Yes! You know this story already?”

“I read a lot about him.”

“Then why did you let me ramble on about it if you knew about it already?” You’re a little embarrassed, having felt proud of yourself for knowing niche facts about historical figures.

“I like listening to you talk.”

That shuts you up for a moment. Only for a moment though, before you start to laugh.

“What?” he asks, an edge creeping into his voice.

“Nothing! It’s just—usually people tell me the opposite,” you say. “People say I talk too much.”

“I don’t mind.” His eyes dart to your face before looking away again.

“That’s good to hear. But I hope you know this means you’re never getting rid of me now,” you tease, nudging him gently.

He doesn’t respond, but for a second, you could have sworn that a corner of his mouth had turned up into a smile.

Learning more about him is like trying to draw blood from a stone, but you do your best. He mentions sharing a room with a cousin. His oma makes the best comfort food. Sometimes his mother takes him into town to buy candy, but he has to hide it or his cousin will steal it. Not that he cares that much—he doesn’t have much of a sweet tooth, but his family doesn’t come from means, so it means a lot to him whenever his mother spares a few pennies to buy him a frivolity.

It's what he doesn’t say that tells you the most about him. The way he fidgets with his clothes when he’s nervous. The brief panic that shoots through him whenever you call his name before he relaxes when he realizes it’s just you. The way he shies away from people in the hallways, just to avoid any contact whatsoever.

The fact that he never talks about his father.

The way he curls into himself when he’s being bullied.

“You should be apologizing to me for being in my way right about now, freak,” Andreas taunts him. He’s knocked Alexander’s books to the ground, like some sort of cartoon caricature of a bully, and you’re fed up.

“Hey!” Without missing a beat, you slide yourself between Alexander and Andreas. You’ve recently hit a bit of a growth spurt, so you note with a bit of smugness that you’re at least an inch or two taller than Andreas. You’re also quite a bit taller than Alexander, you realize. The two of you are usually sitting when you talk, so you’ve never really noticed.

“Leave him alone!” You stand your ground even as Andreas fixes you with a withering glare.

“Ah, so you’re gonna let your big strong girlfriend fight your fights now, is that it?” Andreas sneers. Alexander stiffens behind you, and you decide right then and there that you’ve had enough of this nonsense.

“You’re the last person who should be bringing up girlfriends, Andreas,” you say, staring him down with a look that you hope is sufficiently intimidating. “Everybody knows Yulia broke up with you because you can’t get it up.” You don’t know Yulia. You don’t give enough of a shit about Andreas to follow the gossip about him. But by the way his cheeks get ruddy, you know you’ve struck a nerve. The handful of spectators your little confrontation has attracted snicker.

“You little bitch,” he snarls. You hear the gasp of the students surrounding you before you feel it. You put a hand to your rapidly reddening cheek.

The little twerp had slapped you.

“That’s what you get for getting in my way,” he says, with a smug little look that you want to wipe off his face.

You’re not a violent person. And honestly, you could have been expelled for what happens next. But you cast a quick glimpse behind you at Alexander on the ground, and something about the look in his eyes reminds you of that bird you rescued, and a quick and hot anger rises in you.

You punch Andreas.

With no wind-up, no warning, you break his nose, and he drops like a rock, howling and clutching at the blood pouring from his nostrils. A sick little giggle comes out of you as you watch, drowned out by the uproar of your little audience.

“What on earth is going on here?!” You hear a teacher roar, and the crowd quickly begins to scatter. Without hesitation, you pull Alexander up and escape before you can be subjected to the consequences of your actions.

“Boy, am I glad he didn’t put up more of a fight,” you say gleefully, high on adrenaline. “That could have gotten quite ugly.”

“I didn’t know you had that in you,” Alexander says when the two of you have gotten far away enough. The way he looks at you now is a little different—almost reverent.

“I didn’t know either!” you say. “I’ve never done that before!”

“Who knew such a pretty rose had such sharp thorns?” he mumbles to himself. Your eyes zip to him, and even he looks surprised at the words coming out of his mouth.

“A pretty rose?” you tease, nudging him on the arm. He flushes pink and turns away, but there’s a bit of a lopsided half-smile on his lips.

You’re not sure why, but the sight of it makes your skin tingle.

The first few years of high school are relatively uneventful outside of skirmishes with Alexander’s various tormentors. Your biggest regret is that you can’t always be there for him—sometimes you have to spend your free periods catching up on readings or speaking with teachers. But you’re always there for him afterwards, poison in your voice as you hatch plans to make his bullies’ lives miserable. The plans never go anywhere, but thinking about retribution always seems to make him perk up a little. And really, that’s all that matters to you.

It's silly, how long it took you to realize how much of a fixture he was in your life. There’s a street corner a few blocks from the school you always meet him at so the two of you can walk the rest of the way together. The few times you share classes, you’re always sitting together, exchanging notes and quietly judging your classmates together. And you always, always sit with him during lunch. Even when you start making other friends who surely would welcome you at their tables, you always return to the quiet green-eyed boy in the corner.

You tell yourself it’s because he’s lonely, and he needs the company. You tell yourself the rumors about the two of you are silly, the result of bored hormonal teenagers who can’t fathom being a genuine friend to someone of the opposite sex. You tell yourself it means nothing that your face feels warm whenever he smiles at you.

You never get the chance to figure out if it does mean anything. He gives you the bad news on the last day of classes before summer break.

“I…I see,” you say, trying to swallow past the lump in your throat. For once, you’re at a loss of what to say. His fingers twist around each other in his lap, the way they only do when he’s really anxious.

“Well, a fresh start is good, right?” You offer him a smile, but your heart’s not in it. Maybe you haven’t spent as much time with him as you used to back in first year—you’ve started to take more advanced classes, and you’ve been so swamped with homework and projects that sometimes hanging out with Alexander is put on the back burner. But you’d always taken comfort in knowing that he would always be there at mealtime. A steady presence in your life, as everything around you seems to be speeding towards a future you’re not quite ready for yet.

Now he’s leaving. You’d like to think your concern is for him—what’s to say his new school won’t also be rife with harassment? Will he be able to make new friends? Or will he be all alone at the lunch table again? But really, who are you trying to fool? The sudden heaviness in your chest is selfish. What are you going to do without him?

The roaring in your head stills as you feel his hand cover yours. You stare at it dumbly, unable to lift your head and look him in the eyes. Your gut feels like it’s flipping and twisting all over itself.

You lift your eyes to his. For one breathless, indescribable moment, you think he’s going to kiss you. You’re sure he’s going to kiss you. You lean closer to him, and you can feel his breath on your lips.

Your eyes slide shut.

A shout startles your eyes back open, and he jolts away from you. It’s your mother, calling that she’s here to pick you up. You let out a frustrated noise as you call back to her that you’re coming before turning back to him.

The moment is long gone, and your heart twinges with regret as he avoids meeting your gaze. “You’ll write to me, won’t you?” you say softly. “And we can still see each other?”

“Of course I will, rosethorn,” he says, with that shy little smile you love so much.

You don’t see him for another ten years.

I couldn't utter my love when it counted I couldn't whisper when you needed it shouted Ah, but I'm singing like a bird 'bout it now

It’s ironic, really. Saving birds. Saving boys. But the one person you can’t save is yourself.

Your life post-König is like the drop on a roller coaster, but with none of the thrill. High school flies by in a flurry of deadlines and mental breakdowns. It’s worth it when you get into a good university—at least, you thought so. In reality, there’s no work in Austria for someone with your degree. Your parents are older, well on their way towards retirement, so you find yourself unwilling to burden them. You’re lost, stuck, and so very alone.

And then you meet him.

Tall, handsome, a little older, with a blossoming career. In hindsight, how much of a perfect package he presented himself as was the earliest red flag. But when you’re young and behind on rent, anything better than that feels like a miracle.

You know better, really. You knew it the whole time. Getting married after knowing each other for 2 months isn’t as bad as it could be, but it’s still too quick for your comfort. But the eviction notice was on your door, and he was a perfect gentleman. What could go wrong, right?

Everything. He at least has the decency to keep up the façade for another month, but that’s the only credit you’ll ever give the man you’ve shackled yourself to. It becomes increasingly obvious that he only married you to have a live-in maid while he philanders around as he pleases. You try, oh god do you try, for five long, fruitless years. God, it’s so silly when you think about it. You liked him so much, it took you so long to realize he had never liked you in the first place. He’d scooped up the first desperate college grad he’d found, and thinking about it makes you want to hide from everyone you know.

Which you do: hiding from what few friends you do have, hiding from your parents, hiding from the part of your brain that screams that you’re wasting the best years of your life cleaning up after a grown man who won’t even touch you, much less fuck you. Your 20s are for drinking, one-night stands, and figuring out what the fuck the rest of your life is going to look like. There is plenty of drinking, but the rest of it, not so much.

You’re going to divorce him, you tell yourself in year six. Once you get a job, you’re out. But you’re no fresh grad anymore, and the 6-year gap in your resume isn’t helping matters. You spot a glimpse of light at the end of the tunnel when he tells you you’re moving: his company is offering him a higher paid position, and it’s in a bustling downtown area. Plenty of opportunity for you, right?

That’s when he starts hitting you.

You’re away from your parents, your friends, your home. You took English classes, but that won’t exactly help you in this equally European foreign country whose language you don’t speak. Now that you’re approaching your 30s, your husband seems to be rapidly realizing that his youth is also disappearing. His new job is more stressful, and most days he has no outlet for it other than taking it out on you.

Now you long for the days when he didn’t come home until you’d already fallen asleep.

And then the terror attacks begin, and your once-bustling city shuts down. More isolation. Even less hope. You stay at home all day, torn between hoping someone will get rid of your husband for you and the abject terror of being left all alone in a foreign country torn apart by violent partisans.

That’s when the despair really sets in: you’ve wasted over a decade in this awful, dead-end relationship. Sure, you’ve got a roof over your head and food in your stomach: you should feel grateful. But you don’t.

You start hoping the attacks will take you out instead.

I fled to the city with so much discounted Ah, but I'm flying like a bird to you now Back to the hedgerows where bodies are mounted

“There are mercenaries in town.”

You look up from your breakfast, lost in thought thinking about all the errands you have to run today. “Yeah?”

“About time we stopped relying on our corrupt fucking military,” he grumbles. “Maybe they’ll end this goddamn conflict once and for all.”

You don’t have much to say about that. What does it matter to you, anyway? The only conflict that matters to you lives at home, and you stopped trying to fight it a long time ago.

“The curfew’s a pain in the ass, though. You behave yourself, you hear me?” His sharp glare reminds you that he’s not saying this out of a concern for your safety: if you make trouble for him, you’ll pay for it later. You nod mutely.

Your morning goes by relatively uneventfully. You do the dishes, stare at the wall, sigh, stare at the wall some more. As much of a prison as this apartment is, you like it decently well when he’s not in it. Going outside and seeing the ravages of war all around you is anxiety-inducing. But you can’t put off buying groceries anymore.

The arrival of the mercenaries makes itself immediately apparent. The streets are somehow even emptier, and what people there are on the streets move quickly and cast suspicious glances at everyone else.

You were hoping not to interact with anybody, but your hopes are dashed when you see a checkpoint ahead, manned by soldiers in unfamiliar uniforms. Although most of them are wearing different gear, they still look more orderly and well-kept than the country’s own military. Murder must pay well.

You look around nervously, but there’s no alternate route here, and nobody local going through with you. You strongly consider going home, but you’d just have to do this all over again tomorrow.

You steel yourself with a deep breath.

“Identification?”

You show the mercenary your ID with trembling fingers, gripping your bag tightly and praying he doesn’t find your nervousness suspicious.

“Where are you headed?”

“Just—just down the street,” you say, wincing at your heavy German accent. Years upon years of living here and you still sound like a foreigner. “Getting food.” You’re so anxious you forget the word for “groceries” for a moment. You only know enough of the local language to get by, and you’re sure you must sound like a kindergartener.

The soldier raises an eyebrow at you. “You are German?”

“I…Austrian,” you answer hesitantly. Oh God, you hope there’s no issue with that. You’re not so much afraid of being detained as you are of getting home too late to make dinner.

“Interesting.” The soldier hands back your ID. “Our commander is Austrian, as well.”

You perk up a little bit at that. You’ve met a handful of German-speakers here, but not a single one of your countrymen.

Well. Aside from the one who came here with you.

“He should actually be arriving here any moment now. Big guy in a hood. You can’t miss him. They call him König.” As if on cue, a military grade vehicle pulls up to the checkpoint, military personnel stepping out. And then…

Your blood runs cold.

Nothing, nothing could have prepared you for the sight of the beast that steps out of the car. Even from a short distance, you can tell he’s a colossal size. Two metres tall, easily, wearing a dark hood that reminds you of a medieval executioner. And as if that weren’t intimidating enough, two red trails, like bloody tears, are bleached under his eyes. His eyes, which must have some sort of black paint around them, giving him the impression of being two eyes staring out at you from the pitch blackness of the hood.

Two piercing green eyes.

Trained directly on your face.

Staring in disbelief.

“I…need to return home. I’ve forgotten something.” All worries about appearing suspicious fly out the window as the enormous man in the hood hesitates for a moment before making his way towards you with alarming speed.

You all but fly back down the street, making a beeline for your building. Just a few moments ago, you were excited to meet the man. Now, the image of his eyes staring into yours fills you with a fear you can’t describe.

The next day you take a long detour to avoid the checkpoint. It’ll take you twice as long to get home this time, but it’s worth it. You can’t put the shopping off another day: the brand-new bruise on your arm throbs as a reminder. And you certainly don’t want to run into the hooded soldier again.

You get your shopping done without much fanfare. The old lady cashier, who usually looks at you from over her glasses with the stern look you’ve seen a lot of people around here level at foreigners, even pressed a piece of candy from behind the register into your hand. You’re pretty sure it’s just because she wanted to get rid of it, but it does wonders for your mood.

You’re busy plotting when to enjoy your little treat when you turn a corner and freeze.

He’s here. He’s there, standing in an alleyway near your building. Somehow even larger than you remember him yesterday, still wearing that awful hood.

Does he know where you live? You curse yourself for running straight home yesterday. He must have seen the direction you went in—or did he follow you? You attempt to quietly retreat and take another route home, but your shoe scuffs a paving stone. And like a hawk spotting its prey, his head darts towards you.

You book it.

“Wait!” calls a deep voice. Tears spring to your eyes as you hear heavy footsteps pursuing you. What have you done to deserve this? You’re no criminal. Your only crime is being a naïve dumbass in your twenties.

Your arm burns as you turn corner after corner, not bothering to take note of where you’re going. It’s no use, though: you can hear him gaining on you. Fuck, is this it? You can’t even fathom what he wants you for, and you don’t want to think about it either—

“Rosethorn!” You come to a screeching halt.

There’s only one person who has ever called you that.

You turn around, chest heaving with exertion, as the hooded soldier—König, the soldier said his name was—comes into view, approaching you slowly.

“It’s me,” he says, holding his hands out like he’s approaching a wounded animal. You’re not really sure what the point is, considering the gigantic knife he’s got strapped to his thigh is intimidating all on its own, but somehow it still puts you at ease.

“Alex...?” you whisper, hardly daring to believe it.

“Yes,” he says. His posture has changed from when you saw him at the checkpoint. He’s hunching over, trying to make himself smaller. It reminds you of that first day when you sat next to him at lunch.

It’s him.

You instantly drop all your bags and cling to him in a hug, tears spilling from your eyes. He’s so different: most obviously, he's so tall. He must have hit some growth spurt after he moved away, because he towers over you now. You can feel under all the gear that he’s put on serious muscle—not surprising for a soldier, of course. And when his arms fold themselves over you, you’re filled with a sense of safety you haven’t felt in a long time.

“What are you doing here?” you both ask at the same time. A giggle bubbles out of you as you watch his eyes crinkle in an obvious smile. God, his eyes are so green.

“I’m stationed here because of the conflict,” he says. “But what are you doing here? I contacted your parents, and they said you had moved here, but they didn’t say why.”

You’re not surprised. You’re still in contact with your parents, but you don’t talk about the elephant in your home. You know they would have helped you, if only you had asked for it, but you never have.

“I…it’s complicated,” you say, withdrawing from the hug. You stare at the ground, brushing away the wetness in your eyes.

“I have nothing urgent right now,” he says, staring at you intently.

You swallow past the lump in your throat. “I…got married,” you whisper.

Instantly, his body language changes, stiffening in shock. He takes a half-step away from you, which makes you want to cry all over again. This is awful. This is humiliating. You wish you could go back in time and shake some sense into yourself.

“I see,” he says in a strangled voice. “Congratulations.”

Despite your best efforts, the tears spill over again. “No, not congratulations,” you say. “It—”

It was the worst mistake of your life, you want to say, but you just can’t get the words out. He must notice you beginning to quake with fear, because he raises a hand to touch you gently on the arm—right on the bruise.

His stare hardens as he watches you flinch. “Rosethorn, what’s the matter?”

Everything, you want to say. I’m standing in an alleyway with my childhood crush, shaking like a leaf because a monster lives in my house, and I can’t get away from him.

With a feather-like touch surprising for a man with such large hands—he grew so much— he goes to push up your sleeve. You catch a glimpse of the bruise before you have to turn away again, shuddering. It’s ugly: black and green, and very clearly shaped like a human grip.

“I…bumped into a shelf,” you say lamely. You can’t bring yourself to rope him into your troubles. He’s a soldier now, for Pete’s sake. He has bigger problems.

You can’t read his expression due to the hood—but there’s a blazing anger in his eyes you remember all too well. The quiet fury you often saw in him so many years ago.

He must see in your expression that you don’t want to be questioned about it right now, and thankfully, he relents. With an ease in his movement that must stem from some newfound confidence, he reaches over and picks up your bags for you. “Let me carry these for you.”

It’s nice, to be taken care of for once.

Your mad dash took both of you quite far away from your building, so you have enough time for quite a nice little chat. You tell him about your time in university, he tells you what happened to him after he moved away. He’d jumped at the chance to enlist as soon as he turned 17, on the recommendation of an uncle who had spent time in the military. You laugh when he tells you that they wouldn’t let him be a sniper, a pout in his tone. You could have imagined him as a sniper back in high school, but he’s so large now it’s impossible not to notice him.

“The discipline was good for me,” he recounts. “I needed to grow a spine.”

“Don’t say that. You were just trying to get by in school, like everybody else.”

He shrugs. “I wanted to be like you.”

“Like me?” You ask incredulously.

“My rose with thorns,” he says, with a fondness that makes you blush. “Do you remember that day you punched that punk Andreas?”

“How could I forget? My fist hurt for days,” you say with a grin. “But I didn’t regret it for a second.”

He looks down at you—that’s new—with pride in his eyes. “I thought about you that day all throughout training,” he says. “You were my guardian angel.”

Your cheeks grow even warmer, and you feel like a teenager again. How can he still make you feel this way so easily after all this time? “He had a punchable face,” you say dismissively. “If not me, then it would have been someone else.”

You’re almost disappointed to arrive home. Only yesterday, home was your sanctuary. Now, it means being separated from the one person you trust fully in this country. You turn to him, almost bashful. “This is where I live."

He sets the bags down like they’re made of fine china, and he’s standing so close you almost stop breathing. The air is charged, the same way it felt that night when you almost kissed. You watch him as he watches you.

“Can I see you again?” he asks, breaking the silence.

“Of course,” you say, and the sparkle in his eye dazzles you.

You watch him leave until you can’t see him anymore. And for once, you enter your home with a light heart.

Remember me, love When I'm reborn As the shrike to your sharp And glorious thorn

if you'd like to be added to the taglist, just drop a reply! feedback is always appreciated, and my inbox is open, so please feel free to drop me an ask! I will 100% write little scenarios/headcanons about this couple because I have so many thoughts and ideas for them lol

I anticipate about 2-3 parts for this, maybe with König pov in the next part? he doesn't come across this way in this part, because it's from Thorn's perspective, but he is a very nasty boy indeed. also, I know putting lyrics in the middle of a fic is so passé, but I can't help myself. it's hozier! indulge me. also this isn't beta read so I really hope it doesn't suck

#bucca writes#könig#könig x reader#könig cod#könig mw2#call of duty#cod mw2#cod x reader#cod#mw2#konig#konig cod#konig x reader#fic:shrike

491 notes

·

View notes

Note

Shows or movies based on historic figures and events are hard to pull off if the goals are to be both entertaining and somewhat true to history. If we accept that some inaccuracies can't be avoided in order to appeal to audiences what would you consider cornerstones and pillars about Alexander and his history that can't/shouldn't be touched in order to paint a somewhat realistic picture in media based on him and his life?

How to Make a Responsible Movie or Documentary about Alexander

I saved this to answer around the time of the Netflix release. For me, there are four crucial areas, so I’ll break it down that way. Also. I recognize that the LENGTH of a production has somewhat to do with what can be covered.

But, first of all…what story is one telling? The story arc determines where the focus lies. Even documentaries have a story. It’s what provides coherence. Is it a political tale? A military one? Or personal? Also, what interpretation to take, not only for Alexander but those around him. Alexander is hugely controversial. It’s impossible to make everyone happy. So don't try. Pick an audience; aim for that audience.

MILITARY:

Alexander had preternatural tactical skills. His strategy wasn’t as good, however, especially when younger. Tactics can be a genius gift (seeing patterns), but strategy requires experience and knowledge of the opposition. The further into his campaign, the more experience he gained, but the cultures became increasingly unfamiliar. He had ups and downs. He was able to get out of Baktria finally by marrying Roxana. That was strategy, not tactics. He beat Poros, then made a friend of him; that’s strategy. Yet he failed to understand the depth of the commitment to freedom among the autonomous tribes south along the Indus, which resulted in a bloody trek south. And his earlier decision to burn Persepolis meant he’d never fully reconcile the Persian elite.

So, it’s super important to emphasize his crazy-mad tactical gifts in all forms of combat, from pitched battles to skirmishes to sieges. Nobody in history ever equaled him except maybe Subatai, Genghis Khan’s leading general. In the end, I think that’s a lot of Alexander’s eternal fascination. He fought somewhere north of 250 battles, and lost none (where he was physically present).

But HOW to show that? What battles to put on screen? Oliver Stone combined three into one + Hydaspes because he had only 2-3.5 hours (depending on which cut you watch). The Netflix series is going to show all four of the major pitched battles…or at least all 3 for the 6-episode first part. They had circa 4.5 hours to play with, but they cut out other things, like Tyre.

Another issue, from the filming/storytelling point-of-view is how to distinguish Issos from Gaugamela for the casual viewer. They’re virtually identical in tactics (and players on the field). So it made a fair bit of sense to me for Stone to conflate them. In a documentary, it’s more important to separate them, largely to discuss the fall-out.

Some v. important clashes weren’t the Big Four. Among these, the sieges of Halikarnassos and Tyre are probably the most impressive. But the Aornos Rock in India was another amazing piece. I’d also include the bridging of the Indus River to illustrate the astonishing engineering employed. Again, if I had to pick between Halikarnassos and Tyre, I’d pick Tyre. I was a bit baffled by Netflix’s decision to show Halikarnassos instead, but I think it owed to an early error in the scripts, where they had Memnon die there. I corrected that, but they’d already mapped out the beats of the episodes, so they just kept Halikarnassos. That’s fine; it was a major operation, just not his most famous siege.

Last, I really wish somebody, someday, will do something with his Balkan campaigns. What he did in Thrace and Illyria, at just 21, showed his iron backbone and quick thinking. It’d make a great “and the military genius is born” set-up, drama wise. But you could use the Sogdian Rock to show the clever streak, at least (“Find men who can fly” … “I did; look up.” Ha) Plus it has the advantage of being where he (maybe) found Roxana.

Last, he fought extremely well--wasn't just good at tactics. Being a good general doesn’t necessarily mean one’s a good fighter. He was. Almost frighteningly brave, so show that too.

RELIGIOUS:

Ya gotta deal with the “Did he really think he was a god?” thing, and the whole trip to Siwah. I obviously don’t think he believed he was a god; it’s one of the things I disliked about the Netflix show’s approach, but they were dead-set on it. I DO think he came to believe he was somehow of divine descent, but of course, that’s not the same as most moderns understand it, as I’ve explained elsewhere. It made him a hero, not a god on a level with Zeus, and to ME, that’s an important distinction that Netflix (and to some degree Stone) rode roughshod over.

But I’d like to see more inclusion of sacrifice and/or omen-reading—religion in general. Cutting the Gordion Knot (omens!). His visit to Troy (Netflix tackled that one). A really cool thing would be to make more of the lunar eclipse before Gaugamela. Again, Netflix touched on that, but it’s one of those chance events that might actually have affected a battle’s outcome, given how seriously the ancient near east took sky omens. (A solar eclipse once halted a battle.) The Persians were freaked out. Even his massacre of the Branchidai in Sogdiana was driven by religion, not military goals. Pick a couple and underscore them.

I give Stone big props for the sacrifice before the Granikos/Issos/Gaugamela battle. It was so well-done, I’ve actually shown it in my classes to demonstrate what a battlefield sphagia sacrifice would look like.

Alexander was deeply religious. Show it.

POLITICAL:

Ah, for ME the most interesting stuff surrounding Alexander occurs at the political level. Here’s where the triumph story of his military victories all went south. He knew how to win battles. He was less good at managing what he’d conquered.

In terms of a story arc, the whole period up to Gaugamela is really the “rise” of the story. Post-Gaugamela, things began to collapse. And I would pin the turn on PERSEPOLIS. Yes, burning it sent home a message of “Mission accomplished.” But he was selective about it. Areas built by Darius I were spared, Xerxes’ were destroyed: a damnio memoriae.

Problem: Persepolis embodied Persia, and ATG essentially shat on it. Not a good look for the man who wanted to replace Darius III. That he also failed to capture and/or kill Darius created an additional problem for him. Finally, his lack of understanding of how politics worked in Baktria-Sogdiana resulted in an insurgency. Bessos was going to rebel, regardless. But Spitamanes might not have. Alexander created his own mess up there.

Another matter to look at is why he created a new title—King of Asia—instead of adopting the Persian title (King-of-Kings). I don’t think that was a “mistake.” He knew perfectly well the proper Persian title (Kshāyathiya)…and rejected it. He adopted some Persian protocol, but not all of it. After the summer of 330, he was essentially running two parallel courts, which seemed to satisfy neither the Persians nor his own men. (Kinda like docudramas are a hybrid that seems to annoy perhaps more than satisfy.)

So I’d like to see this handled with some nuance, but it’s intrinsically difficult to do—even while, if done well, it would be the most interesting part of an Alexander story, imo.

So, what events, what events…3-4 leap out after Alexander’s adoption of some Persian dress. The Philotas Affair, the Pages Conspiracy, the Death of Kleitos, the marriage to Roxana. I’d show it all, although I could also understand reducing the two conspiracies to one, for time, in which case, the Philotas Affair because it resulted in the fall of Parmenion. But the fact there were two, not just one, tells a story itself.

What about the proskynesis thing with Kallisthenes? I’ve come to disbelieve it ever happened, even though it’s symbolic of the whole problem. So, weirdly, I’m of two minds about showing it. OTOH, it won’t be in my own novels. But OTOH, I could easily see why a showrunner or director might want to include it. And it certainly appears in several of the histories, including Arrian.

Then we have the two indisciplines (mutinies)…one in India that made ATG turn around, and another at Opis. They’re really two different things as one was an officer’s rebellion, the other the soldiers themselves. But will viewers be able to distinguish between them? It’s like the Issos/Gaugamela problem, or for that matter, the two conspiracies. They’re similar enough to confuse the casual viewer. “Didn’t we already see that?”

But if they were narrowed to one, how to choose? The mutiny on the Hyphasis provides an explanation for why he turned back. But the Opis event was more dramatic. The man jumped down into the middle of a rioting crowd and started (essentially) knocking heads together! So if I had to pick…Opis. The other might could be mentioned in retrospect.

PERSONAL:

Here are five things I think really OUGHT to be shown, or that I have yet to be pleased by.

1) Philip isn’t an idiot and should get more than 10 minutes of screentime. Oh, and show Alexander did learn things from him. Stone had to make his movie a Daddy-Issues flick, and the Netflix thing did very little with Philip as they wanted to get to the Alexander-Darius face off (which was the meat of their story). But there’s a very interesting love/competition story there.

2) Olympias is not a bitch and was not involved in Phil’s murder, although I can see why that is catnip to most writers. She did kill Eurydike’s baby and (by extension) Eurydike. One of the historians in the Netflix story (Carolyn, unless I misremember) talked about the rivalry between the two wives, at least. But I think ATG planned to marry the widow and Olympias got rid of her to prevent it. Now THAT’S a story, no? But they were in too much of a hurry to get to Persia.

3) Alexander was not an only child! He had sisters (and a brother) with whom he was apparently close…and a cousin who was his real rival. To me, missing that cousin rivalry overlooks a juicy personal/political story! Too often all the focus winds up on Alexander-Olympias-Philip-Eurydike-Attalos, but man, a more subtle showrunner could do a lot with the Alexander-Amyntas rivalry. But he’s constantly cut out. I can’t think of a documentary that actually addresses Amyntas except in passing (if at all)l

4) Hephaistion’s importance is a must, but I’d like to see him treated as someone with a personality and authority of his own, besides just as ATG’s lover. At least Netflix Went There onscreen with the love-story part, but otherwise, the writers couldn’t figure out what to do with him. Neither Stone nor Netflix really portrayed him as his own person. I do understand why they can’t show the whole cast of characters. I had to do weeding myself in the novels, but I’m annoyed Netflix showed only Hephaistion and Ptolemy. Where’s Perdikkas (so important all along really, but certainly later)? Or Philotas, Kleitos, Krateros, Leonnatos, Lysimachos (later king of Thrace)? I think viewers could probably have handled at least another 5 people, especially if introduced gradually, not all at the beginning.

This brings me to….

5) Alexander’s apparently very real affection for the people in his orbit, from personal physician (Philip) to childhood pedagogue (Lysimachos [not same as above]) to Aristotle to various other philosophers. He was so loyal to his friends, in fact, he initially jailed the people who brought word of Harpalos’ first flight.

He needed to be loved/appreciated and wanted to give back to people. Yes, generosity was expected of kings, and as a king (THE king), his generosity had to excel that of anybody else. But he seemed to genuinely enjoy giving presents. I think of him like that one friend who heard you say you liked that cute pair of “Hello, Kitty” socks…then 6 months later they’re your Christmas present from them. Some of his gifts were grandiose, but not always. I love the dish of little fish (probably smelts) that he sent to Hephaistion, presumably just because his friend liked smelts!

To me, point #5 would be easy to get in with a skilled scriptwriter, tucked into the corners of other scenes. It’d be fun to highlight the personal side. If we can believe Plutarch, he was a PRODIGIOUS letter-writer. Also, he loved to hunt, so that’s another thing. And he loved the theatre, and to watch sport. These would all be very humanizing details.

I think the biggest issue is that most of these documentaries/docudramas are done by people who don’t know squat about Alexander aside from a few things, before deciding to make a documentary/movie about him, or write a book. Their research is shallow, and even if they bring on the experts, they don’t always listen. Stone DID at least have a long fascination with ATG, but it caused him to try to throw in everything but the kitchen sink. It wasn't as bad of a film as some have made it out to be, just horribly bloated and for all his reading, he never understood the WORLDVIEW. I wrote about that some while back in my review.

The best documentary/movie would be told by an actual specialist who knew enough at the outset to craft a better, more complex story arc.

Or maybe I’m just biased because I tried to do that myself in my novels. 😂😂😂😂

#asks#alexander the great#oliver stone alexander the great#netflix alexander the great#telling the story of alexander the great is intrinsically difficult#docudramas#historical movies#historical documentaries

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inmate Crucifixion Day!!!

So it's no big surprise that the QSMP has some religious imagery going on, and today's supposed conclusion to the Prison Arc is no exception. Today, the inmates are going to be crucified, and we all know what that is.

Right?

Well, hi, I'm A.D., I'm a historian, and today I'm going to teach you all about crucifixion!

Now, crucifixion is a longstanding execution method that dates back way before Jesus was even thought of. We've got accounts of crucifixions dating back to the Persians under Darius I, and we've got even more accounts from all over the place in the ancient world.

Now, let's go over some history real quick, shall we?

~522 BCE: Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, is crucified postmortem by some pissed-off Persians. Maybe.

We don't actually know if this one happened or not, but we do know that he was assassinated. That much is true. The crucifixion part is what's up for debate, but, if it is true, then Polycrates here has the privilege of being the first ever victim of crucifixion. Lucky him!

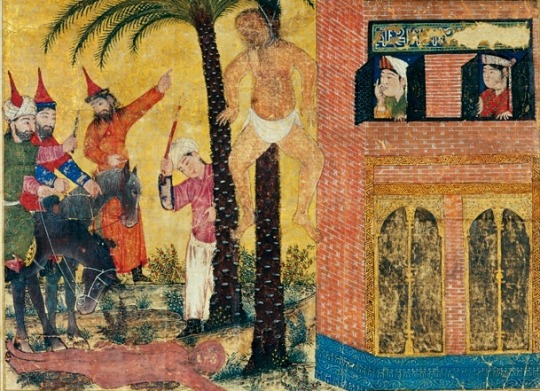

~519 BCE: Darius I orders the crucifixion of something approximating 3,000 political opponents in Babylon

See, the thing about Persian crucifixions is that the prisoners weren't usually nailed to the cross shape we all know. Nah, they were tied up with their hands above their heads, strung up on a single pole. This way, their death would take a lot longer, and the prisoner would suffocate under their own weight. This would last for days, usually with the prisoner being left up to be humiliated even after their death.

~417 BCE: Persian general and tyrant Artaÿctes is crucified by Athenians in a rather uncharacteristic act

But also take this with a grain of salt because this account comes from Herodotus, and I don't trust that dude with much more than a fun story.

The Greeks didn't really think much of crucifixion. They were like, "We're above this. We are civilized", but also. They did not like the whole "Persian Invasion" thing, and so sometimes they ended up resorting to measures they weren't too happy with. Such is war!

~332 BCE: Speaking of war, Alexander the Great supposedly had 2,000 survivors of his siege of Tyre crucified.

The thing with Alexander is that a lot of what people say about him is probably bullshit.

~88 BCE: Ancient Judean king Alexander Jannaeus supposedly had 800 Pharisees-slash-rebels crucified in the middle of Jerusalem

And now we get to the Romans, who kinda perfected the whole thing. They were super into crucifixion. They were so into it that they had a bunch of different ways of doing it!

Getting impaled on a stake

Getting tied to a tree

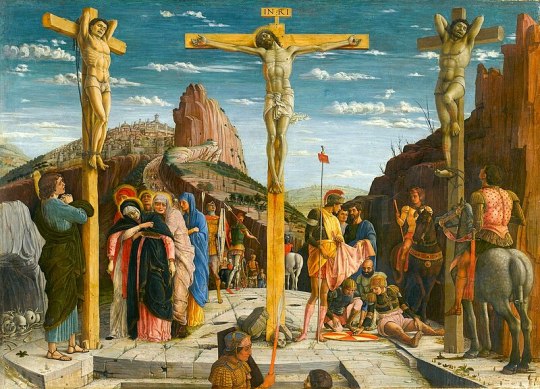

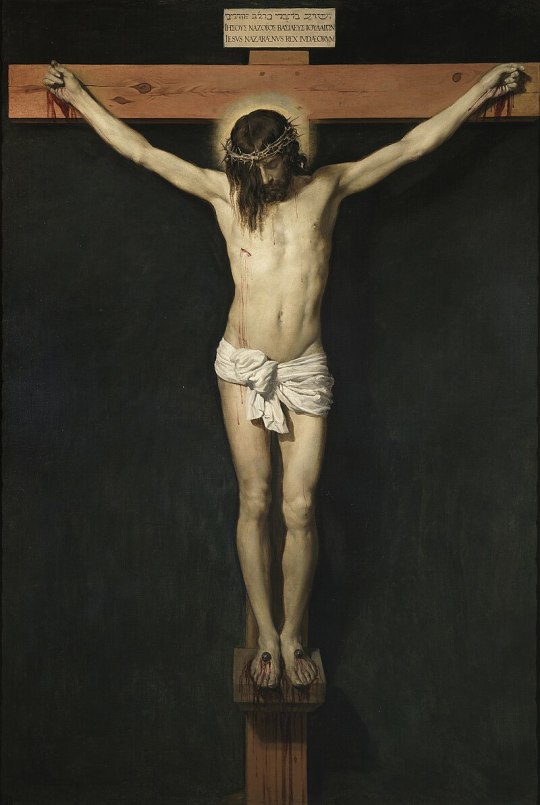

Getting tied to a crux simplex (see image below)

Getting stuck to a cross

The whole crucifixion thing was seen as a way to deter people from doing the same crimes that the crucified people did. It was all about torture and humiliation. We have reports of people being crucified for days, and of people having to carry their own crucifixes (see: Jesus Christ.)

Sometimes people were tied to their crucifixes. Sometimes they were nailed to them. It varied by region and by criminal and by executor. Criminals were generally stripped completely naked (again, humiliation), though, again, the position depended on the region, criminal, and executor. The way Jewish people were executed was different than how, say, slaves or renegade gladiators were executed.

I'm not going to get into the whole process because that's very long and yucky. But I will repeat just how popular it was! Because MAN, the Romans LOVED it! Crassus ordered the crucifixion of at least 6,000 rebels and followers of Spartacus after the Third Servile War (but, then again, he was a piece of shit.)

Of course, we can't forget about the most famous crucifixion of all:

~32 CE: Jesus.

Jesus of Nazareth remains the most famous victim of crucifixion, and it's because of the nature of his particular crucifixion that everybody thinks of crucifixion as The Thing With The Cross.

And this is probably what everybody's thinking of when they're talking about the QSMP inmates being crucified today.

But he wasn't the only religious figure to be crucified!

Cut to:

Either 274 CE or 277 CE: Mani, the Parthian Prophet and the founder of Manichaeism, is crucified in a way super similar to Jesus

Tbh we don't know when he died, but his followers purposefully compared his death to Jesus' despite there possibly being literally no crucifixion involved at all.

But, you know what? Crucifixion happened all over the place!

Islamic territories had crucifixion going on simply because they lived where crucifixion had been taking place for centuries, and there was a lot of debate surrounding crucifixion in relation to the various rules and regulations surrounding criminality and the potential justification of execution.

Japan, interestingly enough, also has a pretty long history of crucifixion. Supposedly, it was introduced in the 15th century by pesky Christian missionaries, but the Japanese had had a similar tradition going on before that. But Japanese crucifixion, called haritsuke wasn't really like the kind we're familiar with. There was water crucifixion (mizuharitsuke) reserved for Christians, and there was upside-down crucifixion (sakasaharitsuke.) Fun!

(There is photo evidence of this even up on the Wikipedia page, but you can find that on your own. I'm not putting that on my blog, thanks.)

As the years continued, crucifixion became a bit less widespread, though there is photo evidence of its use in Japan up through the 19th century, and then reports of it being used in World War One by the Germans and then in World War Two against the Germans.

Unfortunately, it's still a practiced tradition in a few parts of the world. Saudi Arabia and Sudan still have crucifixion as an execution method, and it's still a reported method being used by certain extremist factions in Syria, Iran and Myanmar.

So... yeah! That's crucifixion for you! It's a truly terrible fate, but not an overtly religious one. It only really became religious when Jesus ended up getting killed, and, even then, it's only seen as such by groups of people steeped in Christian culture (such as many countries and cultures living in what people call "The West".)

I can only imagine that the religious aspect is what's going to come into play on the QSMP, because I doubt that this literal Minecraft Roleplay Series will employ actual literal torture and execution methods live on Twitch.

#a.d. talks history#qsmp#i guess! i talk about it!#anyway all my sources are basically from my head and from some quick research#can you tell i was raised catholic?#and that i took a class on ancient persia last year? lol

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

365 Promises of God

Day 296 – Tyre Shall Be Scraped Clean and Cast into the Sea

"Therefore thus says the Lord GOD: 'Behold, I [am] against you, O Tyre, and will cause many nations to come up against you, as the sea causes its waves to come up. 'And they shall destroy the walls of Tyre and break down her towers; I will also scrape her dust from her, and make her like the top of a rock. (Eze 26:3-4 NKJV)

Read: Ezekiel 26

Today’s promise is to the ancient city of Tyre, and is more of a prophecy. So, why would I bring it up? Mainly because it stands out as the most incredibly accurate prophecy in the Bible, and is clear proof that the Bible is divinely inspired.

Ezekiel the prophet predicted that like the sea waves, armies would come up against Tyre again and again, until it was destroyed. But God doesn’t leave it there. Eze 26 tells them that the walls of Tyre would be broken down, and her towers, too. That her timbers and walls would be cast into the sea. And even the dust of her would be scraped off, leaving Tyre like the top of a rock. This astounding and unlikely prophesy is one of the most amazing predictions found in scripture, and one of the best evidences for the divine inspiration of the Word of God.

In v3 he predicts that many nations would attack, and in v7 he names Babylon as the first. In v12 he promises that the stones, timbers and debris would be thrown into the sea. In v4 he predicts that the bare rock would be scraped clean, a place for drying fisherman’s nets.

Finally, he promises Tyre would never be rebuilt (v21). Eight times in this chapter it is clearly stated that the words spoken are from the Lord God.

Yet, at the time this prophecy was given, Tyre was a great Phoenician city and world capital, and had been so for almost 2000 years. It had clear dominance of the seas. It consisted of a small but well-developed island about a half-mile out, and a large mainland city with high walls, strong gates, and freshwater springs that supplied the city. Farms and livestock inside the city walls made a siege meaningless. The prediction was laughable. But then God…

In 586 BC, 3 years after this prophecy, Babylon laid siege to Tyre. Inhabitants who saw this coming fled to an island a half mile out to sea. For 13 years Babylon laid siege to the great mainland city of Tyre. When it became obvious they would never be starved out, battering rams were brought up and shields locked overhead to protect those driving the rams from arrows and rocks raining down from above. Once breached, chariots raced into the city, stirring up dust over the entire city, as Babylon’s army slaughtered those on the mainland. This was a hollow victory, however, because the wealthy lived on the island, within sight of the army, but out of reach. In his rage, Nebuchadnezzar ordered the walls broken down and the towers broken down as well, leaving just a pile of rubble where the city used to stand. But it wasn’t scraped clean, was it?

After the fall of Mainland Tyre, the citizens of Tyre built a giant sea wall around their island and port, and continued to do a profitable business using their great fleet. They continued to dominate the sea, but never again built on the ruins of the mainland city.

241 years after Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of Mainland Tyre, Alexander the Great marched to conquer Persia. But before he did, he needed to ensure that Tyre, which commanded such a massive fleet, would not attack Greece while he was gone. So he marched to the site of the old city, and sent emissaries in boats to demand the surrender of the city on the island. Of course, they refused. After all, what could he do about it? He had no navy.

Alexander had his chief architect Diades construct a causeway out to the island 800 meters away. He did this by having the army cart the rubble of the old city to the sea, and cast it in, fulfilling the prophesy in v12. The stones and timber of the walls filled the intervening area, and the dirt of the streets and outlying areas was scraped off, to form a packed top sufficient to carry siegeworks across to the island, which was now more of a peninsula. So the debris of the city was scraped off, just as promised 244 years before. The island city of Tyre fell to Alexander’s great army. They broke through the Sea wall and slaughtered the people, carried off the treasure and burned the ships. Its ruins can still be seen to this day.

If you examine the location of Tyre now, you will see that instead of an island it is a peninsula. The city actually now resides on Alexander’s Causeway. And where the main city used to be, there is only a park, and a place for fishermen to fish.

The promise I unpacked today was to the City of Tyre and its inhabitants, and not to you and me. But the gift it gives us is more valuable than the treasure of this ancient city. You see, through the clear presentation and fulfilment of prophesy like this, we can find rock-solid faith in the God who wrote it. Far more solid, even, that the causeway Alexander built while fulfilling this promise.

Prayer:

Father God, thank you for this incredible prophesy, such compelling proof that you say what you mean, and mean what you say. May others find trust in your word as well, today. Amen

#christian#writing#devotional#365 devos#365 promises of god#prophecy#the bible#christblr#word of god#Babylon#Tyre

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The reasons for Alexander the Great's descent beneath the waves in a "bathysphere" differ across time. For some, it was to scout submarine defenses surrounding the city of Tyre during its siege. Others depict the Macedonian king met with a cruel vision of the great chain of being, stating, upon resurfacing, that “the world is damned and lost. The large and powerful fish devour the small fry”. In one particularly elaborate version, Alexander submerges with companions — a dog, cat, and cock — entrusting his life to a mistress who holds the cord used to retrieve the bathysphere. However, during his dive, she is seduced by a lover and persuaded to elope, dropping the chains that anchor Alexander and his animal companions to their boat. Through a gruesome utility, the pets help him survive: the cock keeps track of time in the lightless fathoms, the cat serves as a rebreather to purify the vessel’s atmosphere, and the poor hound’s body becomes a kind of airbag, propelling Alexander back to the sea’s surface.

https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/alexander-bathysphere

(Pictured here: Miniature by an unknown artist for Jansen Enikel's contribution to the World Chronicle, ca. 1400)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Had to do this thing on Alexander the Great and the Siege of Tyre for classical studies work while the teacher was out

Am actually curios on people's opinions on this tho

Im gonna go with agree for the sake of getting the assignment done and also cause the only other siege we've covered in class was the Sacking of Thebes so theres not much comparison (at least he didnt completly raze the city this time. Just half of it plus the one on mainland)

Also how is Tyre pronounced? My teacher pronounces it as Tear but several youtube videos pronounce it as Tire

#And its from fuckboy fanboy Arrian#not my G Plutarch 😔#who is weirdly controversial in my classical studies class#half the class dont like him cause he rambles too much#wolffox speaks#classical studies#Ancient Greek history#Alexander the great#Arrian#greek history#ancient greece#History

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle at Tyre

-- Alexander sieged Tyre for seven months

-- received help from Phoenician fleets -- Sidon -- Aradus -- Byblos

-- Alexander surrounded the island of Tyre

-- attacked several key points

-- Tyrians retreated to the harbors

-- seriously damaged Alexander’s fleet

-- Alexander used rams to break down a weak part of the Tyrian wall

-- tried for three days to enter the city

-- finally entered

-- inhabitants massacred or sold as slaves -- 30,000 sold as slaves

#history#historyblr#history notes#world history#world history notes#western civ#western civ notes#western civilization#western civilization notes#western civ 1#western civilization 1#western civ 1 notes#western civilization 1 notes#studyblr#phoenicia#battle at tyre#tyre#alexander the great#byblos#aradus#sidon#greek history#ancient greece#ancient greek history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#alessandro magno#alessandro iii di macedonia#alexander the great#prossime uscite#alessandro il grande#alessandro il macedone#alexander the conqueror#alessandro il conquistatore#alexander iii of macedon#alexander of macedon#Westholme Publishing#David A. Guenther

0 notes

Text

images of alexander the greats siege of tyre are flashing through my mind rn

꧁★꧂

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Siege of Tyre: How Alexander the Great Captured the Phoenician City

https://www.thecollector.com/siege-of-tyre-alexander-the-great/

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

The siege of Tyre by Alexander

The siege of Tyre by Alexander, of Syracuse by Nicias, of Carthage by Scipio, the two sieges of Jerusalem by Titus and by Godfrey, the successive sackings of Rome, the defence of Rhodes and Malta against the Turks — none of these can quite equal in vivid colour and breathless interest the two great captures of Constantinople, and certainly the last. It stands out on the canvas of history by the magnitude of the issues involved to religion, to nations, to civilisation, in the glowing incidents of the struggle, in the heroism of the defence and of the attack, in the dramatic catastrophe and personal contrast of two typical chiefs, one at the head of the conquerors and the other of the defeated. And by a singular fortune, this thrilling drama, in a great turning-point of human civilisation, has been told in the most splendid chapter of the most consummate history which our language has produced.

The storming and sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade by a mixed host of Venetian, Flemish, Italian, and French filibusters, a story so well told by Mr. E. Pears in his excellent monograph, was not only one of the most extraordinary adventures of the Middle Ages, but one of the most wanton crimes against civilisation committed by feudal lawlessness and religious bigotry, at a time of confusion and superstition. It is a dark blot on the record of the Church ephesus sightseeing, and on the memory of Innocent HI., and a standing monument of the anarchy and rapacity to which Feudalism was liable to degenerate. The sack of Constantinople by the so-called soldiers of the cross in the thirteenth century was far more bloodthirsty, more wanton, more destructive than the storming of Constantinople by the followers of Mahomet in the fifteenth century. It had far less historic justification, it had more disastrous effects on human progress, and it introduced a less valuable and less enduring type of civilised life. The Crusaders, who had no serious aim but plunder, effected nothing but destruction. They practically annihilated the East Roman Empire, which never recovered from this fatal blow.

Byzantine Empire

It is true that the Byzantine Empire had been rapidly decaying’ for more than a century, and that its indispensable service to civilisation was completed. But the crusading buccaneers burned down a great part of the richest city of Europe, which was a museum and remnant of antiquity; they wantonly destroyed priceless works of art, buildings, books, records, and documents. They effected nothing of their own purpose; and what they indirectly caused was a stimulus to Italian commerce, the dispersion through Europe of some arts, and the removal of the last barrier against the entrance of the Moslem into Europe.

The conquest by the Ottomans in the fifteenth century was a very different thing — a problem too complex to be hastily touched. Europe, as we have seen, was by that time strong enough to win in the long and tremendous struggle with Islam; it was ready to receive and use the profound intellectual and artistic impulse which was caused by the dispersion of the Byzantine Greeks. The Ottoman conquest was no mere raid, but the foundation of a European Empire, now in the fifth century of its existence.

The wonderful tale of the rise, zenith, wane, and decay of the European Empire of the Padishah of Roum — one of the least familiar to the general reader — is borne in upon the traveller to Stamboul in the series of magnificent mosques of the conquering sultans of the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, in the exquisite fountains, the mausoleums, the khans and fortresses, minarets and towers, and the strange city of kiosques, palaces, gates, gardens, and terraces, known to us as the Seraglio. In these vast and stately mosques, in the profusion of glowing ornament, porcelains, tiles, and carvings, in the incongruous jumble of styles, in the waste, squalor, and tawdry remnants of the abandoned palace of the Padishahs, we read the history of the Ottoman Turks for the last five centuries — splendour beside ruin, exquisite art beside clumsy imitation, courage and pride beside apathy and despair, a magnificent soldiery as of old with a dogged persistency that dies hard, a patient submission to inevitable destiny beside fervour, loyalty, dignity, and a race patriotism which are not to be found in the rank and file of European capitals.

But Stamboul is not only a school of Byzantine history; it has rich lessons of European history. We see the Middle Ages living there still unreformed — the Middle Ages with their colour and their squalor, their ignorance and credulity, their heroism and self-devotion, their traditions, resignation, patience, and passionate faith. We can imagine ourselves in some city of the early Middle Ages, the meeting-place of nations, Venice or Genoa, Paris or Rome, or even old Rome in the age of Trajan, where races, religions, costumes, ideas, and occupations meet side by side but do not mix.

0 notes

Photo

The siege of Tyre by Alexander

The siege of Tyre by Alexander, of Syracuse by Nicias, of Carthage by Scipio, the two sieges of Jerusalem by Titus and by Godfrey, the successive sackings of Rome, the defence of Rhodes and Malta against the Turks — none of these can quite equal in vivid colour and breathless interest the two great captures of Constantinople, and certainly the last. It stands out on the canvas of history by the magnitude of the issues involved to religion, to nations, to civilisation, in the glowing incidents of the struggle, in the heroism of the defence and of the attack, in the dramatic catastrophe and personal contrast of two typical chiefs, one at the head of the conquerors and the other of the defeated. And by a singular fortune, this thrilling drama, in a great turning-point of human civilisation, has been told in the most splendid chapter of the most consummate history which our language has produced.

The storming and sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade by a mixed host of Venetian, Flemish, Italian, and French filibusters, a story so well told by Mr. E. Pears in his excellent monograph, was not only one of the most extraordinary adventures of the Middle Ages, but one of the most wanton crimes against civilisation committed by feudal lawlessness and religious bigotry, at a time of confusion and superstition. It is a dark blot on the record of the Church ephesus sightseeing, and on the memory of Innocent HI., and a standing monument of the anarchy and rapacity to which Feudalism was liable to degenerate. The sack of Constantinople by the so-called soldiers of the cross in the thirteenth century was far more bloodthirsty, more wanton, more destructive than the storming of Constantinople by the followers of Mahomet in the fifteenth century. It had far less historic justification, it had more disastrous effects on human progress, and it introduced a less valuable and less enduring type of civilised life. The Crusaders, who had no serious aim but plunder, effected nothing but destruction. They practically annihilated the East Roman Empire, which never recovered from this fatal blow.

Byzantine Empire

It is true that the Byzantine Empire had been rapidly decaying’ for more than a century, and that its indispensable service to civilisation was completed. But the crusading buccaneers burned down a great part of the richest city of Europe, which was a museum and remnant of antiquity; they wantonly destroyed priceless works of art, buildings, books, records, and documents. They effected nothing of their own purpose; and what they indirectly caused was a stimulus to Italian commerce, the dispersion through Europe of some arts, and the removal of the last barrier against the entrance of the Moslem into Europe.

The conquest by the Ottomans in the fifteenth century was a very different thing — a problem too complex to be hastily touched. Europe, as we have seen, was by that time strong enough to win in the long and tremendous struggle with Islam; it was ready to receive and use the profound intellectual and artistic impulse which was caused by the dispersion of the Byzantine Greeks. The Ottoman conquest was no mere raid, but the foundation of a European Empire, now in the fifth century of its existence.

The wonderful tale of the rise, zenith, wane, and decay of the European Empire of the Padishah of Roum — one of the least familiar to the general reader — is borne in upon the traveller to Stamboul in the series of magnificent mosques of the conquering sultans of the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, in the exquisite fountains, the mausoleums, the khans and fortresses, minarets and towers, and the strange city of kiosques, palaces, gates, gardens, and terraces, known to us as the Seraglio. In these vast and stately mosques, in the profusion of glowing ornament, porcelains, tiles, and carvings, in the incongruous jumble of styles, in the waste, squalor, and tawdry remnants of the abandoned palace of the Padishahs, we read the history of the Ottoman Turks for the last five centuries — splendour beside ruin, exquisite art beside clumsy imitation, courage and pride beside apathy and despair, a magnificent soldiery as of old with a dogged persistency that dies hard, a patient submission to inevitable destiny beside fervour, loyalty, dignity, and a race patriotism which are not to be found in the rank and file of European capitals.

But Stamboul is not only a school of Byzantine history; it has rich lessons of European history. We see the Middle Ages living there still unreformed — the Middle Ages with their colour and their squalor, their ignorance and credulity, their heroism and self-devotion, their traditions, resignation, patience, and passionate faith. We can imagine ourselves in some city of the early Middle Ages, the meeting-place of nations, Venice or Genoa, Paris or Rome, or even old Rome in the age of Trajan, where races, religions, costumes, ideas, and occupations meet side by side but do not mix.

0 notes

Note

I’m not sure if it’s just me as someone who more-so passively enjoys learning about this topic rather than delves into intensive research, but I always feel like Alexander’s siege of Tyre tends to get less attention than his other battles even though it’s literally one of the ballsiest and most insanely impressive feats he’s ever pulled off. If that’s true, do you think there’s a reason for the lack of general exploration of that point in his career?

See, I'd say that the siege of Tyre is his BEST-known non-pitched battle! It seems as if everyone has heard of Tyre--one reason I was surprised when the Netflix show ignored it in favor of Halikarnassos. (Although that seems to owe to a boo-boo in the original scripts that I won't go into.)

But in most of the documentaries and such that I've seen, Tyre is the siege most focused on, followed by Thebes. Some of his other sieges are completely ignored, like the Aornos Rock in India, despite the absolutely mind-blowing difficulty of that one, too.

Keep in mind that most scholars will divide his pitched or set-piece battles from the rest of the conflicts that he fought, including sieges. There were many, MANY more of these other battles, but only 4 pitched battles: Granikos, Issos, Gaugamela, and Hydaspes. (This doesn't count Chaironeia, as that was his father's strategy.)

Pitched battles tend to get the focus because they're "winner-take-all" events that occur for only a day, or really, part of a day. Sieges, etc., can take days, weeks, even months, as with Tyre.

Some of Alexander's most notable NON-pitched conflicts include Tyre, Thebes, Gaza, Halikarnassos, the Persian Gates, the Sogdian Rock, insurgency in Baktria, the Aornos Rock, Mali, and some of the fights against Brahmin along the south Indus.

#Alexander the Great#Alexander's sieges#Alexander's battle tactics#asks#classics#Alexander's pitched battles#Alexander's other battles#Alexander the Great and strategy#Alexander the Great and tactics#Alexander the Great military history

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The siege of Tyre by Alexander

The siege of Tyre by Alexander, of Syracuse by Nicias, of Carthage by Scipio, the two sieges of Jerusalem by Titus and by Godfrey, the successive sackings of Rome, the defence of Rhodes and Malta against the Turks — none of these can quite equal in vivid colour and breathless interest the two great captures of Constantinople, and certainly the last. It stands out on the canvas of history by the magnitude of the issues involved to religion, to nations, to civilisation, in the glowing incidents of the struggle, in the heroism of the defence and of the attack, in the dramatic catastrophe and personal contrast of two typical chiefs, one at the head of the conquerors and the other of the defeated. And by a singular fortune, this thrilling drama, in a great turning-point of human civilisation, has been told in the most splendid chapter of the most consummate history which our language has produced.

The storming and sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade by a mixed host of Venetian, Flemish, Italian, and French filibusters, a story so well told by Mr. E. Pears in his excellent monograph, was not only one of the most extraordinary adventures of the Middle Ages, but one of the most wanton crimes against civilisation committed by feudal lawlessness and religious bigotry, at a time of confusion and superstition. It is a dark blot on the record of the Church ephesus sightseeing, and on the memory of Innocent HI., and a standing monument of the anarchy and rapacity to which Feudalism was liable to degenerate. The sack of Constantinople by the so-called soldiers of the cross in the thirteenth century was far more bloodthirsty, more wanton, more destructive than the storming of Constantinople by the followers of Mahomet in the fifteenth century. It had far less historic justification, it had more disastrous effects on human progress, and it introduced a less valuable and less enduring type of civilised life. The Crusaders, who had no serious aim but plunder, effected nothing but destruction. They practically annihilated the East Roman Empire, which never recovered from this fatal blow.

Byzantine Empire

It is true that the Byzantine Empire had been rapidly decaying’ for more than a century, and that its indispensable service to civilisation was completed. But the crusading buccaneers burned down a great part of the richest city of Europe, which was a museum and remnant of antiquity; they wantonly destroyed priceless works of art, buildings, books, records, and documents. They effected nothing of their own purpose; and what they indirectly caused was a stimulus to Italian commerce, the dispersion through Europe of some arts, and the removal of the last barrier against the entrance of the Moslem into Europe.

The conquest by the Ottomans in the fifteenth century was a very different thing — a problem too complex to be hastily touched. Europe, as we have seen, was by that time strong enough to win in the long and tremendous struggle with Islam; it was ready to receive and use the profound intellectual and artistic impulse which was caused by the dispersion of the Byzantine Greeks. The Ottoman conquest was no mere raid, but the foundation of a European Empire, now in the fifth century of its existence.

The wonderful tale of the rise, zenith, wane, and decay of the European Empire of the Padishah of Roum — one of the least familiar to the general reader — is borne in upon the traveller to Stamboul in the series of magnificent mosques of the conquering sultans of the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, in the exquisite fountains, the mausoleums, the khans and fortresses, minarets and towers, and the strange city of kiosques, palaces, gates, gardens, and terraces, known to us as the Seraglio. In these vast and stately mosques, in the profusion of glowing ornament, porcelains, tiles, and carvings, in the incongruous jumble of styles, in the waste, squalor, and tawdry remnants of the abandoned palace of the Padishahs, we read the history of the Ottoman Turks for the last five centuries — splendour beside ruin, exquisite art beside clumsy imitation, courage and pride beside apathy and despair, a magnificent soldiery as of old with a dogged persistency that dies hard, a patient submission to inevitable destiny beside fervour, loyalty, dignity, and a race patriotism which are not to be found in the rank and file of European capitals.