#The Age of American Unreason in a Culture of Lies

Text

“Being a bad biocitizen.”

-------

Marlene Feenstra (née McCorrister), my grandmother, was a Cree woman from Peguis First Nation. Peguis, our nation, is nestled among the ancestral lands and shared territories of the Cree, Anishinabeg, Assiniboine, and Métis peoples -- our homelands that sprawl out from the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers in what is now Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. [...] Gram [was] born in 1936 [...]. She attended residential school [...], and then, as an adult, she was legally denied residence on her reserve due to her marriage to a non-Indian [...]. Yet, despite these and other experiences, and like many Indigenous people, my grandmother never thought of herself as being colonized. [...]

Three years ago, when my grandma passed away, I spent a few days going through the old photographs, newspaper clippings, calendars, and notes she had archived for over sixty years. [...] I was glad, on that cold Winnipeg afternoon, to appreciate her taste in interesting imagery. Their combined content lays out a scene ripe for analysis: One card depicts what it called the “Discovery of Canada”: Jacques Cartier presenting the “weird apparition” of an Indian Chief to the king and queen of France in 1536. A postcard named the “Canadian Rockies” displays a scene of Alexander Mackenzie, Simon Fraser, and La Verendrye: on the back, the card describes them as “great explorers who played stupendous and courageous roles in western development.” Another postcard features the nineteenth-century Métis leader Louis Riel, sitting inside a prison cell awaiting his federally sanctioned execution. Finally, at first glance out of place in this set, is a postcard with the name “Science and Invention” and an image of a basement laboratory peopled by Albert Einstein, Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and Frederick Banting.

-------

It is difficult to say whether Gram chose these cards for how, taken together, they illustrate the curious relationships between colonial expansion, the confinement of Indigenous peoples, and scientific inquiry. If she did conceive of the reciprocal relationships connecting the logics of exploration, discovery, and innovation with histories of colonialism, then she was in good company.

Historians of colonial science, for example, have shown that there is a historical relationship between the development of what is now considered modern science, the technoscientific advances indelibly marking Western civilization, and European imperialisms and colonialisms. Further, Indigenous studies scholars have located modern science within an ongoing colonial system that, working in tandem (and, at times, in tension) with other institutionalized fields, overwrites Indigenous peoples’ knowledges of their existence as peoples in terms of the logics of citizenship, rights, sovereignty, and capital. [...]

-------

Advances in genomic knowledge are both intriguing and frightening given that the “gift” and “weight” of science and technology fields have always been simultaneously present for Indigenous peoples.

When I was invited to speak at “The Gift and Weight of Genomic Knowledge: In Search of the Good Biocitizen,” out of which this special report evolved, I was enthused by the rich conference rationale provided by organizers Joel Reynolds and Erik Parens. Consistent with Foucauldian scholarship such as that of Nikolas Rose, Carlos Novas, and Dorothy Roberts, the conference framed biocitizenship in relation to that shift provoked by increasing amounts of biological, and especially genomic, knowledge and data that are changing the ways that citizenship is being imagined. Civic responsibility in the age of biocitizenship, Reynolds and Parens observed, encompasses being and remaining healthy for the sake of ourselves and for the greater good of human populations: biometrically monitoring one's physical activity, seeking out direct-to-consumer genetic tests, coughing into the inside of one's elbow, employing barrier methods during sexual intercourse, and on and on are all examples of good bio-practice. In this spirit, biocitizenship -- the emphasis on the human population as biological -- has been endowed with the capacity to reconcile historic wrongs. The conference and this special report, as I understand them, are challenging us all to take pause amidst the accelerating pace of biomedical and genomic data generation and to critically reflect on the seemingly simple yet hugely difficult questions, what is a “good” biocitizen, and how do we become one?

I propose that one analytical pathway leading to said aspirational goodness might be found in its reverse: that is, in badness.

Following bell hooks's description of politicized looking relations, I am establishing these provocations to reorient, from my explicit vantage point, the set of concepts and real-world problems that this special report explores. As examined by hooks, in resistance struggle, the power of the dominated to assert agency by claiming and cultivating “awareness” politicizes looking relations -- one learns to look a certain way in order to resist. Reframing the terms of the discussion is a critical practice in also restructuring the power dynamics that shape common-sense ideas about what it means to be good. The exogenous generation of genomic knowledge about indigeneity, for example, exerts a scientific claim that one can see indigeneity in a way that actually matters. Seeing indigeneity through the prism of genomic knowledge is shaped by colonial lenses insofar as it is based on an understanding of indigeneity as primarily real, genetically. Academic and other ways of thinking that try to make sense of and represent genomic realities of the present are also structured by colonial looking relations. [...]

-------

Over twenty years ago, among the formative scholarship of early Indigenous studies, Vine Deloria Jr. published Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact (1995). Through this book and his other works, Deloria locates modern science within a colonial matrix that seeks to secure itself as a panacea of truthful knowledge creation at the expense of Indigenous sovereignties. [...] Fields, including scientific fields, that attempt to externally translate Indigenous peoples’ self-conceptions into a categorical or taxonomical language are interfering with their sovereign way of being.

Since the publication of Red Earth, White Lies, others have considered what the complicated entanglements of Indigenous knowledges are as they exist in relationship to science and technology fields. In Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (2013), Robin Wall Kimmerer, for instance, provides a textually melodic illustration of the complementarities between botany, Potawatomi ecology, and the human and nonhuman relations that sustain her everyday experience. Noenoe Silva's Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism (2004) similarly considers how Kanaka Maoli have leveraged modern technological advancements in press and printing to oppose the illegal annexation of their territories. These works and others like them have unlocked methodological potential that is not premised on orthodox cultural expectations by framing the use and formation of twentieth- and twenty-first-century sciences and technologies as being instead Indigenous. These novel works set a stage for elaborate consideration of how engagement with technosciences on Indigenous peoples’ own terms might support their local governance systems: their ways of relating in and with localities of misewa (all that exists). [...]

-------

Fundamental to colonial civilizing missions were the so-called gifts of science and technology that Western imperial powers gave to their colonies and subjects.

Through the rhetorical prism of gifting, scientific claims to the “greater good” have been an enduring logic justifying scientific pursuits, while the collateral damage characteristic of incremental and experimental scientific methods have been disproportionately felt by Indigenous peoples as well as all other bodies deemed unreasoned (including human and nonhuman). [...]

Although there are now many versions of justice in concept and practice, many if not all of them are shaped through the presumed possibility that a normative good exists and that the journey of becoming good is, in itself, good. [...]

I charge non-Indigenous and Indigenous peoples alike to be bad: unpack and undermine the investments they have in propertied [...] state-based sovereignty and nationalism, capitalist cultures of consumption, and settler fantasies of being rightful and good.

-------

Jessica Kolopenuk. “Provoking Bad Biocitizenship.” Hastings Center Report Vol. 50 Issue S1. June 2020.

146 notes

·

View notes

Link

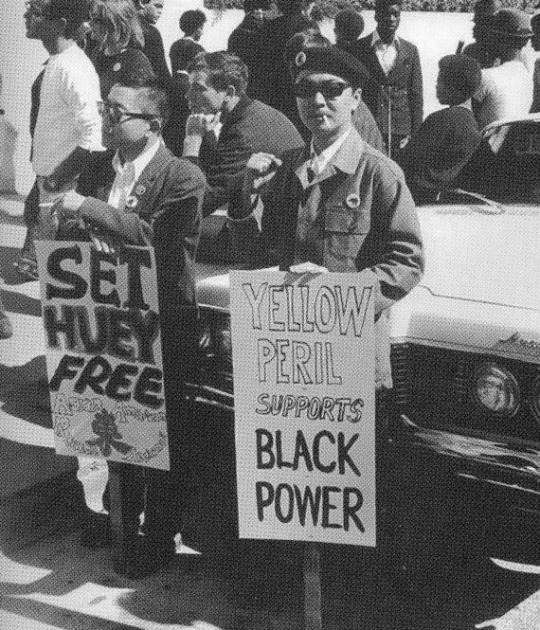

On June 24, amid great cultural upheaval and unrest, Glenn Yu reached out to Glenn Loury, his former teacher, to record his thoughts about the current moment. An edited version of their conversation follows.

…

You may or may not have an opinion about that, but suppose the question were to arise in the dorm room late at night. Suppose you have the view that you’re not sure it’s racism, and then someone challenges you, saying, “you’re not black.” They say, “you’ve never been rousted by the police. You don’t know what it’s like to live in fear.” How much authority should that identitarian move have on our search for the truth? How much weight should my declarations in such an argument carry, based on my blackness? What is blackness? What do we mean? Do we mean that his skin is brown? Or do we mean that he’s had a certain set of social-class-based experiences like growing up in a housing project? Well, white people can grow up in housing projects, too. There are lots of different life experiences.

I think it’s extremely dangerous that people accept without criticism this argumentative-authority move when it’s played. It’s ad hominem. We’re supposed to impute authority to people because of their racial identity? I want you to think about that for a minute. Were you to flip the script on that, you might see the problem. What experiences are black people unable to appreciate by virtue of their blackness? If they have so much insight, maybe they also have blind spots. Maybe a black person could never understand something because they’re so full of rage about being black. Think about how awful it would be to make that move in an argument.

Suppose someone, a white guy, is arguing about affirmative action with you. Suppose he thinks that affirmative action is undignified because he thinks that positions should be earned, not given, but he allows that he doesn’t expect someone like you to understand that argument because you’re black. That would be terribly unreasonable— even “racist.” Yet I’m hard-pressed to see the difference.

…

People cry, “structural racism.” Is that why the homicide rate is an order of magnitude higher among young black men? They say structural racism. Is that why the SAT test-score gap is as big as it is? They say structural racism. Is that why two in three black American kids are born to women without a husband? Is it all about structural racism? Is everything structural racism? It has become a tautology explaining everything. All racial disparities are due to structural racism, evidently. Covid-19 comes along and there’s a disparity in the health incidence. It’s due to structural racism. They’re naming partners at a New York City law firm and there are few black faces. Structural racism. They’re admitting people to specialized exam schools in New York City and the Asians do better. This has to be structural racism, with a twist—the twist being that this time, the structural racism somehow comes out favoring the Asians.

This is not social science. This is propaganda. It’s religion. People are trying to win arguments by using words as if they were weapons.

…

And just so I don’t sound like a right-winger, observe that if I were a Marxist, I’d be furious at these people going around talking about “structural racism.” Structure, yes. Racism, no. Because if I were a Marxist, which I’m not, I’d understand the driving force of history to be the interaction between class relations and the means of production, the struggle between workers and capital in the quest for profit given the logic of capitalism. Though I don’t subscribe to it, that’s at least an intellectually serious theory. I know what people are talking about when they say we need more unions, when they say we need to break up big companies, when they say that the accumulation of wealth has gotten too great. When someone says that the logic of profit-seeking leads to war, at least I know what they’re talking about. I don’t necessarily have to agree with Das Kapital to understand that it’s a serious engagement with history.

Structural racism, by contrast, is a bluff. It’s not an engagement with history. It’s a bullying tactic. In effect, it’s telling you to shut up.

…

Yu: I’ve had conversations in the past few weeks that have ended very poorly; conversations that have spiraled out of control, where I’m suddenly a racist, so I’m on damage control. I just don’t know how to reach people in a meaningful way, and that’s very disturbing to me.

Loury: It is disturbing. I’m not a seer. My mouth is not a prayer book. I only say what I say based on my subjective assessment of it all. But it may be that, for a while anyway, there’s not going to be a whole lot of effective talking. It may well be that we have to imagine a world where effective deliberation and consensus is not within reach for us, and we’re going to have to manage that situation. It could get very bad. It could go to violence. This is what Sam Harris always says, and he’s got a point. He says that if we can’t reason together, then the only alternative for dispute resolution is violence.

I don’t know if you saw my piece in Quillette about the looting and the rioting, but I pick up these pieces published in the New York Times, respectable left-wing journals. I’m reading them, and the writer is saying, “America was founded on looting. What did you think the Boston Tea Party was?” Or, “You’re talking about looting when George Floyd lies dead? Oh, I see, black lives don’t matter as much as property.” These are, to my mind, incomprehensibly idiotic. I don’t mean that to cast aspersions. The civilization that we all enjoy rests upon a very fragile foundation. Look. I’m in my backyard. It’s very nice. I’ve got a lot of space. There’s a fence. The birds come. I have a lawn. It’s mine!

Now, if a homeless person comes and squats in my backyard, I call the police. I have him removed, forcibly. There should be no lack of clarity about whether George Floyd’s death somehow excuses or justifies burning a bodega to the ground that a Muslim immigrant spends his whole life building. Being confused about that, equivocating about that, splitting the difference about that—I don’t understand how we’re going to have a reasoned discussion. My thoughts go back to, protect civilization. Again, I know how that sounds. It’s hyperbolic. It’s exaggerated—but only a little! My gut response is that this is not the time for argument. This is the time to protect civilization and protect institutions. When people start toppling statues of Abraham Lincoln and spray-painting on statues of George Washington, “a slave owner,” things fall apart. The center cannot hold. We teeter on the brink of catastrophe.

…

Yu: If there’s no available policy intervention, and there’s also no way we can change people’s minds, then is it hopeless? Is disparity always going to be the case?

Loury: Yes. My answer is it’s hopeless. But let me rephrase the question, and I’m channeling Thomas Sowell now. You have two alternatives. You can live with disparities, or you can live in totalitarianism. Again, hyperbolic, I know. No, I’m not talking about Eastern Europe circa 1960, but look at it this way: there can’t be a disparity without somebody being on top. People don’t recognize this.

What groups are on top? What about the Jews? You could say, “There are too many Jews in positions of influence.” If there are too few black lawyers who are partners in big law firms, doesn’t it follow that are too many Jews who are partners at these big firms? If there are too few blacks who are professors of mechanical engineering at places like Carnegie Mellon, why aren’t there too many Korean professors at these places?

…

What is the nature of the world that we live in? Why would I ever expect that there would be parity across the board between ethnic, racial, cultural, and ancestral population groups in an open society? It’s a contradiction because difference is a very fact of groupness. What do I mean by a group? Well, it’s genes, to some degree; it’s culture; it’s networks of social affiliation, of intermarriage and kinship. I mean the shared narrative, the same hopes, the dreams, the stories. I mean the practices of parenting and filial piety and whatever else there might be.

A group is a group. It has characteristics. Those characteristics matter for whether you play in the NBA. They matter for whether you learn to master the violin or the piano. They matter for whether you pursue technical subjects or choose to become a humanist or a scientist. They matter for the food that you eat. They matter for how many children you raise and how you raise them. They matter as to the age when you first have sex. They matter for all those things, and I think everyone would agree with that.

But now you’re telling me that they don’t matter for who becomes a partner in a law firm? They don’t matter for who becomes a chair in the Philosophy Department somewhere? Groupness implies disparity because groupness, if taken seriously, implies differences in ways of living life. Not everybody wants to play the fiddle. Not everybody wants to dunk a basketball. Not everybody is frightened to death that their parents are going to be disappointed with them if they come home with an A-minus. Not everybody is susceptible to being swayed into a social affiliation that requires them to commit a violent crime in order to prove their bona fides. Groups differ. Groups are not evenly distributed across society. That’s inevitable. If you insist that those be flattened, you’re only going to be able to succeed by imposing a totalitarian regime that monitors everything and jiggers everything, recomputing and refiguring things until we’ve got the same number of blacks in proportion to their population and the same number of second-generation Vietnamese immigrants in proportion to their population being admitted to Caltech or the Bronx High School of Science. I don’t want to live in that world.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Age of Unreason

Men want certainty, not truth.

- possibly from Bertrand Russell

A thoughtful friend asked me what 2020 will be remembered for, apart from the obvious, ie Covid and Trump losing. I could not think of anything.

My friend suggested it is the realisation that in the 21st century millions of people are turning away from science and reality towards a variety of beliefs that border on the crazy. Examples are QAnon, flat earthers (yes, they are serious), deniers of Covid, about 40% of Americans believe the Rapture is coming, biblical fundamentalism, climate change denial, neo-Nazis, Holocaust denial, belief in Trump as a saviour, doomsday predictions, sundry cults, alien abductions, New Age beliefs, and a multitude of conspiracy theories, such as that the moon landings were a hoax, or that 9/11 was an inside job.

Some of these beliefs appear harmless, but occasionally, they inspire horrific violence, such as the killing of 920 people by the Jim Jones cult, the sarin attack in Japan, the Breivik massacre, the Oklahoma bombing, the Waco siege, the Christchurch massacre, and the Heaven's Gate suicides.

It is difficult to generalise about the various strange beliefs that people hold, as these include conspiracy theories, varieties of denial, religious fantasies, extremist political or racist views, and beliefs like the flat earth, that elude classification. There is no common thread underlying this spectrum of beliefs. Rather, they can be characterised by what they reject, which in a nutshell, is rationality.

Rationality can be defined as the desire to be guided by reason, which we apply to the available evidence. The third ingredient is the willingness to admit we are wrong. So turning away from rationality means letting emotion or emotionally-based belief take precedence over reason, an unwillingness to look at factual evidence, plus a dogmatic belief that one is in possession of the ultimate truth. Many irrational beliefs run counter to Occam's Razor, which tells us to prefer the simplest explanation that covers the known facts. Complex processes may require elaborate or involved explanations, but the point is not to introduce unnecessary factors, especially ones of a fanciful nature.

Clearly, there are too many irrational beliefs to do them justice, so let us look at flat earthers, Heaven's Gate and QAnon to see whether there is a pattern.

A Flat Earth

Flat earth map with the Antarctic ice wall at the perimeter

A bizarre example is the contemporary belief that the earth is flat. Is such a belief even possible in the 21st century? It may be feasible to construct a world view that makes a flat earth plausible. However, it requires factors such as a massive world-wide conspiracy to hide the truth, the abandoning of all of modern cosmology and much of physics, as well as weird ad-hoc explanations for why planes fly in circles around a flat disc, rather than around a spherical globe. Also, that ships at sea disappear below the horizon requires adjustment to the laws of optics. If that still does not cover all the facts countering a flat view, then one could invoke mind control by Martians, or something of the sort. The point is that if one wants to conjure up fantastical reasons to invalidate what we know of reality then it is always possible to do so.

It seems to me that the flat earth people are not interested in gaining knowledge about the world. They are uninterested in discovering what lies beyond the putative ice wall in Antarctica that holds back the oceans or why NASA might be guarding it. They just believe in the flat earth and that is that. Their only concern is to bolster the theory, which I think they hold on emotional grounds. They are willing to perform elaborate mental contortions to support their belief, and it is interesting to observe how much of modern science they are willing to jettison in order to keep their belief afloat, eg gravity.

Whereas the explanations given for the earth being flat are interesting, to me it is more interesting to enquire what causes people to seek these explanations in the first place. What causes people to believe the earth is flat?

Four factors come to mind. One is a desire to be rid of experts and eggheads, who insist on telling ordinary people what to think. In the case of the earth's apparent flatness, the boffins are telling us to deny the evidence of our senses by invoking the large-scale curvature of the earth, something that is far from apparent in ordinary life. Flat earth is like the last stand of common sense in the face of the inexorable advance of science, which keeps telling us the world is far stranger than we thought. It is also a form of contrariness and rebellion against authority. The second is the ego-gratification of knowing a secret that is hidden from nearly everyone else. The third factor is on religious grounds. The fourth is a desire to return to a comforting and anthropocentric model of the universe, rejecting the notion that our planet is an insignificant speck in the incomprehensible vastness of the universe.

Many ancient cultures subscribed to a flat earth cosmography, including Greece until the classical period (323 BC). However, early Christian writers tended to believe the earth is spherical, though with some notable exceptions. Curiously, it wasn't until 1849 that the flat earth belief was resurrected by Rowbotham and later others. He argued that the "Bible, alongside our senses, supported the idea that the earth was flat and immovable and this essential truth should not be set aside for a system based solely on human conjecture".

In the internet era, the proliferation of communications technology and social media have given individuals a platform to spread pseudo-scientific ideas and build stronger followings. The flat earth conjecture has flourished in this environment. Social media and the internet have made it easier for like-minded thinkers to connect and mutually reinforce their beliefs. They have also had a levelling effect, in that experts have less sway in the public mind than they used to.

The belief that the earth is flat could be seen as the ultimate conspiracy theory, given how many people are needed for a cover-up on such a scale. According to the Flat Earth Society's leadership, its ranks have grown by 200 people per year since 2009. Judging by the exhaustive effort flat earthers have invested in fleshing out the theory on their website, as well as the staunch defenses of their views they offer in media interviews and on Twitter, it would seem that these people genuinely believe the earth is flat. They tend to distrust observations they have not made themselves, and often distrust or disagree with each other. I imagine they are maverick individuals who enjoy challenging the status quo.

Paul Sutter, "The question isn't 'why do people believe in a flat Earth?' but rather 'why do people believe in a conspiracy?' And the answer is the same reason it always is: a lack of trust. Many people don't trust the society around them, most notably the representatives of that society. By claiming that the Earth is flat, people are really expressing a deep distrust of scientists and science itself."

Heaven's Gate

Heaven's Gate Logo

Far more bizarre than the flat earth belief are the doctrines of Heaven's Gate, which melded the Bible with belief in UFOs into a religious cult. It was founded in California in 1974 by Marshall Applewhite and Bonnie Nettles. These two pondered the life of St. Francis of Assisi and read works by Helena Blavatsky, RD Laing, and Richard Bach. They studied several passages from the New Testament, focusing on teachings about Christology, asceticism, and eschatology ("the end times"). Applewhite also read science fiction, including Robert Heinlein and Arthur Clarke. They concluded that they had been chosen to fulfill biblical prophecies, and that they had been given higher-level minds than other people. They wrote a pamphlet that described Jesus' reincarnation as a Texan, a thinly veiled reference to Applewhite.

Eventually, Applewhite and Nettles resolved to contact extraterrestrials, and they sought like-minded followers. They published advertisements for meetings, where they recruited disciples, whom they called "the crew". At the events, they purported to represent beings from another planet, the Next Level, which sought participants for an experiment that would bring people to a higher evolutionary level.

In September 1975, the group visited the small town of Waldport, Oregon, to give a lecture about how UFOs were soon going to make contact with the human race. Roughly 150 people packed into a motel hall to hear Applewhite. At first the town thought it was a joke. However, soon after, in a testament to Applewhite's charisma and powers of persuasion, 20 people - or about one in 30 residents of the town - drove off to a meeting of about 400 people in Grand Junction, Colorado, in the hope of meeting aliens.

Later, the crew sold all their worldly possessions and said farewell to loved ones; the group vanished from the public eye. From that point, "Do and Ti", as the two now called themselves, led the nearly one-hundred-member crew across the country, sleeping in tents and begging in the streets. Evading detection by the authorities and media enabled the group to focus on Do and Ti's doctrine of helping members of the crew achieve a "higher evolutionary level" above human, which they claimed to have already reached.

Most of their followers are described by researchers as having been longtime truth-seekers, or spiritual hippies who had long attempted to find themselves through spiritual means. The clan of UFO followers all seemed to have in common a need for communal belonging in an alternative path to higher existence without the constraints of institutionalised faith. The group purchased alien abduction insurance that would pay out $1 million per person, covering abduction, impregnation, or death by aliens.

Applewhite began to emphasize a strict hierarchy, teaching that his students needed his guidance, just as he needed the guidance of the Next Level. A relationship with Applewhite was said to be the only way to salvation and he encouraged his followers to see him as Christ. In the 1980s, the group became more like a religion in its focus on faith and submission to authority. Students who were not committed to this lifestyle were encouraged to leave; departing members were given financial assistance. He specifically cited sexual urges as the work of Lucifer. Applewhite, "We do in all honesty hate this world".

In March 1997, Marshall Applewhite videoed himself in Do's Final Exit, speaking of mass suicide as "the only way to evacuate this Earth". After asserting that a spacecraft was trailing Comet Hale-Bopp and that this event would represent the closure to Heaven's Gate, Applewhite persuaded 38 followers to prepare for ritual suicide so their souls could board the supposed craft. Applewhite believed that after their deaths a UFO would take their souls to another level of existence above human, which he described as being both physical and spiritual.

News of the 39 deaths in Rancho Santa Fe motivated the copycat suicide of a 58-year-old man living near Marysville, California. The man left a note, "I'm going on the spaceship with Hale-Bopp to be with those who have gone before me," and imitated some of the details of the Heaven's Gate suicides as they had been reported in the media. At least three former members of Heaven's Gate committed suicide in the months after the mass suicide.

Heaven's Gate members believed the earth would be wiped clean and refurbished before 2027, and that the only chance for their consciousness to survive was to leave their human bodies at an appointed time. Initially, the group had been told that they would be transported with their bodies aboard a spacecraft that would come to earth and take the crew to heaven, the Next Level. When Nettles (Ti) died of cancer in 1985, it confounded Applewhite's doctrine because Nettles was allegedly chosen by the Next Level to be a messenger on earth, yet her body died instead of leaving physically to outer space. The belief system was then revised to include the leaving of consciousness from the body as equivalent to leaving the earth in a spacecraft.

While the group was against suicide, they defined "suicide" to mean "to turn against the Next Level when it is being offered" and believed their bodies were only vehicles meant to help them on their journey. Suicide, therefore, would be not allowing their consciousness to leave their human bodies to join the Next Level. They believed that, "to be eligible for membership in the Next Level, humans would have to shed every attachment to the planet". This meant members had to give up all human characteristics, such as their family, friends, sexuality, individuality, jobs, money, and possessions.

The Evolutionary Level Above Human was seen as a physical, corporeal place, another planet, where residents live in pure bliss and nourish themselves by absorbing pure sunlight. They do not engage in sexual intercourse, eating or dying. Heaven's Gate believed that what the Bible calls God is actually a highly developed Extraterrestrial. Evil space aliens - called Luciferians - falsely represented themselves to Earthlings as God and conspired to keep humans from developing. Technically advanced humanoids, these aliens have spacecraft, space-time travel, telepathy, and increased longevity. They use holograms to fake miracles. Heaven's Gate believed that all existing religions on earth had been corrupted by these malevolent aliens.

Applewhite taught that "aliens planted the seeds of current humanity millions of years ago, and have come to reap the harvest of their work in the form of spiritually evolved individuals who will join the ranks of flying saucer crews. Only a select few members of humanity will be chosen to advance to this transhuman state. The rest will be left to wallow in the spiritually poisoned atmosphere of a corrupt world". Only the individuals who chose to join Heaven's Gate, followed its belief system, and made the sacrifices required by membership would be allowed to escape the prophesied disaster.

In a group open only to adults over the age of 18, members gave up their possessions and lived a highly ascetic life. The group was strictly regimented, tightly knit and everything was communally shared. Eight of the male members, including Applewhite (who was gay), voluntarily underwent castration as an extreme means of maintaining the ascetic lifestyle. "They couldn't stop smiling and giggling," surviving member DiAngelo told Newsweek. "They were excited about it."

Lalich speculates that they were willing to follow Applewhite in suicide because they had become totally dependent upon him, hence were poorly suited to life in his absence. He isolated them socially and cultivated an attitude of complete religious obedience. Applewhite's students had made a long-term commitment to him. Most of the dead had been members for about 20 years, although there were a few recent converts.

Three of the people who suicided left exit statements on their website. These extoll the joys of the Next Level while summing up people on earth as the walking dead. The texts are not the ramblings of disordered minds. The content is fantasy, but they are written in a lucid way in excellent English and give every appearance of sincerity. Unlike the Flat Earth Society, which no doubt numbers people who joined for a joke, as well as those who are not fully convinced, there is little doubt that the members of Heaven's Gate were totally committed to their beliefs. After all, they gave up their sexuality and their lives for their ideal.

QAnon

QAnon at the Capitol invasion

QAnon is a powerful but diffuse contemporary movement that sought to have Trump re-elected. It is animated by a loose collection of extreme right conspiracy theories whose central theme is that a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles is running a global child sex-trafficking ring and plotting against Donald Trump, who is fighting the cabal. QAnon claims that Obama, Hillary Clinton, George Soros, and others are planning a coup against Trump and are involved in an international child sex-trafficking ring. It alleges that an elite cabal of pedophiles, comprising, among others, Hollywood A-listers, leading philanthropists, Jewish financiers and Democrat politicians, covertly rule the world. Followers of QAnon believe that there is an imminent event known as the "Storm", when thousands of members of the cabal will be arrested and possibly sent to Guantanamo Bay prison, and the US military will brutally take over the country. The result will be salvation and utopia on earth. QAnon promises a "Great Awakening", in which the elites will be routed and the truth revealed.

However, this summary is misleading because QAnon is amorphous, multi-faceted and confusing. In addition it keeps shape-shifting.

The conspiracy theory began with an October 2017 post on the anonymous bulletin-board 4chan by "Q". Q claimed to be a high-level government official with Q clearance. Q predicted the imminent arrest of Hillary Clinton and a violent uprising nationwide. It is likely that Q has become a group of people acting under the same name. QAnon's adherents, while seeing Trump as a flawed Christian, also view him as a messiah sent by God. Trump himself pretends to know little about QAnon, which is a lie. Trump has amplified QAnon messaging at least 216 times by retweeting or mentioning 129 QAnon-affiliated Twitter accounts, sometimes multiple times a day. Being a savvy politician, Trump is perfectly aware that many, perhaps most, of his supporters are QAnon people. He made a correct political calculation, deciding to give only scant public endorsement to QAnon. Showing full support would hurt his standing with moderate Republicans, whereas he does not need to do anything to retain the devotion of QAnon. They are happy with the crumbs he throws their way, being accustomed to snatching at Q's hints.

Q's posts have become more cryptic and vague, allowing followers to map their own beliefs onto them. Part of QAnon's appeal is its game-like quality, in which followers attempt to solve riddles presented in Qdrops by connecting them to Trump speeches and tweets. Q enthralls readers with clues rather than presenting claims directly. Travis View, a researcher who studies QAnon, says that it is as addictive as a video game, and offers the "player" the appealing possibility of being involved in something of world-historical importance. According to View, "You can sit at your computer and search for information and then post about what you find, and Q basically promises that through this process, you are going to radically change the country, institute this incredible, almost bloodless revolution, and then be part of this historical movement that will be written about for generations."

Although Q's claims are false and the prophecies routinely fail, this does little to decrease Q's influence. Believers overlook the lack of results and failed predictions because they gauge the movement's success by its popularity, its opposition from the mainstream media, and its recognition by the President himself. On multiple occasions, Q has dismissed his false claims and incorrect predictions as deliberate, claiming that "disinformation is necessary". This has led psychologist Stephan Lewandowsky to emphasize the "self-sealing" quality of the conspiracy theory, so that evidence against it can become evidence of its validity in the minds of believers. "The absence of evidence is reinterpreted as evidence without batting an eyelid." Conspiracy enthusiasts believe that the burden of proof lies with their opponents, ie that QAnon's claims are valid in the absence of positive proof that there is no cabal and no trafficking of children by Democrats.

Experts judge that QAnon's appeal is comparable to that of religious cults. According to Renee DiResta, QAnon's pattern of enticement is similar to that of cults in the pre-internet era where, as the targeted person was led deeper and deeper into the group's secrets, they became increasingly isolated from friends and family outside the cult. Rachel Bernstein, an expert on cults, has said, "What a movement such as QAnon has going for it, and why it will catch on like wildfire, is that it makes people feel connected to something important that other people don't yet know about... All cults will provide this feeling of being special."

A series of ideas began burbling in the QAnon community: that the coronavirus might not be real; that if it was, it had been created by the "deep state", the cabal of government officials and other elite figures who secretly run the world; that the hysteria surrounding the pandemic was part of a plot to hurt Trump's re-election chances. QAnon is a movement united in mass rejection of reason, objectivity, and other Enlightenment values. Some QAnoners are highly focused on what they perceive as degeneracy in the mainstream media, a perception fuelled in equal measure by Q and by Trump. QAnon may be propelled by paranoia and populism, but it is also driven by religious faith. The language of evangelical Christianity has come to define the QAnon movement. QAnon marries an appetite for the conspiratorial with positive beliefs about a radically different and better future, one that is preordained. As one adherent proclaimed, "It's not a theory. It's the foretelling of things to come."

Edgar Welch is a deeply religious father of two, who until December 4, 2016, had lived an unremarkable life in a small town. That morning, Welch grabbed his collection of guns and drove 580 km to a neighbourhood in Northwest Washington, DC. He held an AR-15 rifle across his chest as he walked through the front door of a pizzeria called Comet Ping Pong. Welch was there because of a conspiracy theory known as Pizzagate, which three years later became a pillar of QAnon. It claimed that Hillary Clinton was running a child sex ring out of Comet Ping Pong. The idea originated in October 2016, when some conspiracy theorists asserted that sexual abuse of children was taking place in the basement at Comet, where there is no basement. After firing a rifle to break a lock, Welch realised his mistake and gave himself up to police. He was sentenced to four years in prison. The New York Times wrote in June 2020 that posts on TikTok with the #PizzaGate hashtag were viewed more than 82 million times in recent months. The abuse of children fantasy arose because someone suggested that emails written by the restaurateurs referring to 'pizza' and 'pasta' were code words for 'boys' and 'girls'.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

by Goya

Anthony Comello was charged with the March 2019 murder of Gambino crime family boss, Frank Cali. According to his defense attorney, Comello had become obsessed with QAnon theories, believing Cali was a member of a "deep state". Comello was convinced he "was enjoying the protection of President Trump himself" so he decided to act. Confronting Cali outside his Staten Island home, Comello allegedly shot Cali ten times. A May 30, 2019, FBI Intelligence Bulletin memo from the Phoenix Field Office identified QAnon-driven extremists as a domestic terrorism threat. Although the conspiracy that QAnon imagines does not exist, there is a real danger that QAnon itself might become a conspiracy of armed vigilantes, determined to bring about the promised "Storm". The storming of the US Capitol by Trump supporters, including QAnoners, is not a good sign.

Heavy on millennialism and the idea that a reckoning awaits the world, the theory has found fertile ground in the American alt-right. Some 56% of Republicans believe that QAnon is mostly or partly true. At least 35 current or former congressional candidates have shown support for QAnon. A Time magazine article listed Q among the 25 most influential people on the internet in 2018. Counting more than 130,000 related discussion videos on YouTube, Time cited the wide range of the conspiracy theory and its prominent followers and news coverage.

Why did Q's cryptic post on an obscure message-board ignite a movement involving millions? Why were so many eager to embrace such a far-fetched conspiracy theory? Perhaps it was the surge in confidence of the Right in the wake of Trump's win. Whatever the reasons, the grass was dry and Q provided the spark. Not all QAnoners come from a rightwing background. For those who have had no agency to suddenly discover a path into the game is heady stuff.

QAnon is not confined to the US. It has organised protest demonstrations in 200 countries, ostensibly to "save the children". One in four Britons are said to believe in QAnon-related theories. According to The Guardian, QAnon is growing in the UK, spilling over into anti-vaccine and 5G protests, fuelled by online misinformation. At a QAnon rally, Shemirani, a nurse suspended for promoting baseless theories about Covid19, told the crowd: "Our government has declared war on the people of the UK."

"There is a high possibility that the spirited belief system which surrounds QAnon can slowly become a political movement in the UK," Liyanage said. "It will be successful because no one can fight it through reason. It's not a rational belief system but mostly a supernatural belief system."

The time for Trump to arrest the pedophiles and satanists is fast running out. It is interesting to speculate what effect his departure will have on a conspiracy theory in which he is the key figure. My guess is that the powerful energy and passion that drive QAnon will shift focus.

My own view is that QAnon is a blank slate onto which people project their darkest nightmares, as well as their hopes for a Christian utopia. Where do the ideas of satanism, eating children, sinister cabals, sexual depravity, and other crimes against children come from? The answer is simple: from the minds of those who form QAnon. QAnon is nothing but a mirror showing people their shared fantasy. People are sharing with each other their worst fears, as well as their hopes. The dark parts are projected onto the favourite targets of the alt-right, ie Hillary and other Democrats, Jews, and liberals, whereas the messianic hopes are projected onto Trump and Q. However, it is a mistake to see the QAnon conspiracy theory as the work of Q. Although Q was the initial cause, his cryptic and vague messages are merely prompts, asking people to fill in the blanks. This is what many have done and the result is a miasma of fanciful lies about corruption, sexual perversions and violence. The irony is that whereas the accusations made by QAnon are entirely baseless, QAnon might itself become a violent entity, little better than the chimera it rails against.

James Baldwin wrote, "It is a terrible, an inexorable, law that one cannot deny the humanity of another without diminishing one's own." Voltaire put it more starkly, "Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities."

Is Credulity Humanity's Achilles Heel?

The three belief systems discussed have almost nothing in common except the rejection of the consensus view of reality, combined with belief in a fantasised conspiracy. In each case, powerful unseen forces are seen as perverting or hiding the truth of what is really going on. All three beliefs appear absurd except to people who are believers. The puzzle is why do apparently normal people adopt such ideas?

In a study published online in March, 2014, in the American Journal of Political Science, Oliver and Wood, found that about half of Americans endorse at least one conspiracy theory, such as the notion that 9/11 was an inside job or the JFK conspiracy. "Many people are willing to believe many ideas that are directly in contradiction to a dominant cultural narrative," Oliver said. According to him, conspiratorial belief stems from a human tendency to perceive unseen forces at work, known as magical thinking.

In the Middle Ages the Devil was a convenient factor that could be used to explain anything weird or harmful, while the deity took responsibility for the rest. With the advance of science, both the Devil and God gradually lost their explanatory powers. God became "the God of the gaps", being only needed to explain what was missing in our understanding of the physical world. Nowadays, the term "act of God" is reserved to describe the insurance industry's view of natural disasters.

In the modern era magical thinking has undergone a new twist. God and the Devil have been replaced by conspiracies. A recent survey of 26,000 people in 25 countries asked respondents whether they believe there is "a single group of people who secretly control events and rule the world together". In the US 37% replied that this is "definitely or probably true". So did 45% of Italians, 56% of Spaniards and 78% of Nigerians.

2020 was the year of Covid19. The coronavirus has triggered the rise of myriad myths, waves of misinformation and virus conspiracy theories, including that it does not exist - believed by 22% in Poland, where there have been nearly 1.4 million cases. The virus has also had an incubating effect on unrelated conspiracy theories because it has thrown humankind into a state of fear and isolated people in their homes with too much time to think and surf. The extra time in the virtual space means increased exposure to the proponents of conspiracy theories, without the balancing effect of social interactions.

According to the Dunning-Kruger Effect, the normal process is that as people begin to acquire knowledge of a given subject, their feelings of competence rise quickly towards a peak, before declining, as they begin to realise how much more there is to know. In the case of conspiracy theories, such as QAnon, people can arrive almost immediately at that delicious peak of confidence, without actually learning anything at all. QAnon is like a super-car that can do 0 to 100 kph in 3 seconds flat. Many are captivated by the vicarious thrill of believing they are privy to vastly important secrets about which millions of people have no idea. This is the seductive appeal of conspiracy theories.

What causes us to believe? There is an analogy between religions and conspiracy theories. Once you pay the price of entry, ie faith in a religious doctrine or conspiracy, the payoff is that much of the confusion and mystery of life is dispelled because you are in possession of the answers. Yuval Harari: "Our lives are repeatedly rocked by wars, revolutions, crises and pandemics. But if I believe some kind of global cabal theory, I enjoy the comforting feeling that I do understand everything. The skeleton key of global cabal theory unlocks all the world's mysteries and offers me entree into an exclusive circle - the group of people who understand. It makes me smarter and wiser than the average person and even elevates me above the intellectual elite and the ruling class: professors, journalists, politicians. I see what they overlook - or what they try to conceal."

The spectrum of irrational beliefs shares one characteristic: they are all unfalsifiable. Their adherents never say, "If such-and-such happens I will discard this belief." This is particularly apparent in doomsday predictions. The predicted date comes and goes, but the true believers simply reset the clock to a future date. A cult called the Seekers went one better. They believed a UFO would save them from a cataclysm on December 24, 1954. Afterwards, some of the members claimed that their group's devotion had saved the rest of the world from disaster. They responded by proselytizing with renewed vigour. Cults and conspiracy theories are highly resistant to correction. Even the thoroughly discredited Pizzagate is still believed by masses of people.

The self-validating nature of the beliefs ensures that all evidence can be construed as confirmation. New findings that contradict a belief are interpreted as proof of the further workings of the conspiracy to hide the truth. Yet cults and conspiracy theories are not the only systems that guarantee their own validation. If one questions what is taught in a personal growth course one is rebuked with, "You are resisting". Pseudo-science is very difficult to debunk. Inconvenient facts, such as aliens not showing up, are explained by another tweak to the doctrine.

To be fair, the process of theory adjustment happens in science proper as well. When a theory fails experimental test it may be given an additional proviso that accounts for the discrepancy. For instance, the fact that personal experience can be handed down as a genetic legacy to future generations seems to contradict standard evolutionary theory. As it turns out, there is no contradiction. A new sub-science called epigenetics explains the mechanism of this process in terms of alterations to the DNA molecule that do not change the genetic code but which influence gene expression.

Since science is a human activity, it is subject to the foibles of our species. It too has dogmas that are difficult to overturn. Thomas Kuhn has written persuasively about paradigm shifts in science. He saw the history of science as consisting of normal and revolutionary phases, in which the community of scientists in a particular field are plunged into periods of turmoil, uncertainty and angst. These revolutionary phases, such as the transition from classical physics to quantum mechanics, involve great conceptual breakthroughs and lay the basis for a succeeding phase of business as usual. This is captured in an aphorism that is only half humorous, "The measure of the greatness of a scientist is how long they hold up advancement in their chosen field."

The history of science features dogmas that were held too long and new ideas that took an unreasonably long time to be accepted. One example is the resistance to the theory of plate tectonics, another is the opposition to a bacterial explanation for the cause of ulcers. The mainstream rejection of functional medicine and the progress it has made in curing Alzheimer's Disease is a current example.

Nevertheless, the greatest strength of science is that it is tentative: any scientific theory may be overturned and replaced by a better theory in the future. The criterion of a theory being scientific is that it makes predictions which could, in principle, be falsified by new data. Yet to a fundamentalist or a common sense sceptic, such as a flat earther, this is not a strength but a weakness. They point out that science can never prove anything, that scientific theories have been debunked plus questions science can't answer. Hence science is not to be trusted. With the authority of science diminished, the field opens for persuasive individuals with pet theories, especially about conspiracies. Why conspiracies? Because a belief that goes counter to the accepted view of reality requires a widespread suppression of the truth.

The bottom line is that many people do not perform due diligence in checking the information they encounter and its sources. Given the virulent spread of QAnon and other conspiracy theories, this is a massive under-statement. The worry is that many obtain their news from questionable sources, such as Facebook and YouTube.

Ultimately, eschewing reputable news media in favour of bulletin-boards and succumbing to their conspiracy theories has deeper causes. These are alienation and a lack of trust in society and its leaders. Why are people alienated and distrustful? Perhaps the underlying problem is not credulity but its opposite, ie a loss of belief in the system. Those who are drawn to far-right conspiracy theories have lost trust in democracy and the modern state. They think the US no longer embodies the ideals they believe in. Conservative Christians and right-wingers resent their defeat in "the culture wars", which were about abortion, separation of church and state, creationism, recreational drug use, homosexuality, and censorship. Perhaps the "Great Awakening" is their dream of a return to how things were. The fact that they grasp at ludicrous ideas indicates the depth of their disaffection.

Of course, irrational beliefs, superstitions, baseless theories and weird cults have been with us all through history, ever since the invention of writing, and probably long before. The difference now is that we supposedly live in the age of reason and science. Furthermore, knowledge is far more freely available than at any time in the past. The problem is that disinformation, extravagant falsehoods, fringe beliefs, and sensational stories are more easily disseminated than ever before, and they seem to capture peoples' attention more than sober facts. The difference between 30 years ago and now is that anyone can post anything and potentially reach millions of people. It's the old story - those who know least have the loudest voices. The paradox is that although reliable knowledge is now easily accessible to anyone with an internet connection, millions are turning their backs on both science and common sense.

My conclusion is that despite the advances of human knowledge, human nature itself has not changed. We remain a species ruled by emotion rather than logic, and hence we come to believe all kinds of nonsense.

Another conclusion comes from an insight of the brilliant intellectual, Yuval Harari. He is convinced that we human beings can only prosper and live in harmony with each other provided we believe in a shared myth. If so, then a propensity towards credulity might be built into our genome. Unfortunately, credulity is dangerous, as shown in Heaven's Gate, the Jim Jones cult and QAnon.

Tad Boniecki

January 2021

1 note

·

View note

Photo

U.S. President Donald Trump during the daily press briefing on the Coronavirus pandemic at the White House, Washington, D.C. - March 17, 2020 - (Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images)

Multi-Pronged Approach Means Trump Will Win on Coronavirus

As the coronavirus crisis rapidly develops, the Trump administration must cope with two paradoxical problems looming above the race to prepare the public health service and shield the population as much as can be done, before the full force of the pandemic arrives.

An imaginative campaign by the government of the Peoples’ Republic of China to represent its response to the coronavirus as a triumph of Chinese efficiency predictably has won the hearts and minds of the credulous Western Left. In fact, it was a disaster of complete unpreparedness, insolent official refusal to pay the slightest attention to incoming facts, totalitarian dissembling and censorship, and the persecution of those who gave unheeded warnings.China now purports — with what must be acknowledged as majestic (though not simply admirable) aplomb — to be laying out a "silk road" of medical assistance to late-coming sufferer-nations. Of course, these nations are all victims of China’s official lies about the medical dangers it had inadvertently fostered and negligently transmitted.

Having inflicted this pestilence on the world, China now claims to be the indispensable world leader in mastering the problem.Of course, the Chinese must not be allowed to get away with this colossal rodomontade. The United States must take the lead in repatriating pharmaceutical production from China, demanding the World Health Organization cease to be a shill-and-whitewash operation for the Peoples’ Republic, and render a truthful and objective account of how this virus got started and how it got so completely out of control.

The Chinese role must be exposed in effectively assuring the exportation of the coronavirus to the whole world, including through the large concentrations of Chinese workers building the self-important "Belt and Road" with which the Middle Kingdom will assert itself across the Eurasian land-mass, and through its failure to give advisory warnings to international travelers.China deliberately ignored the universally recognized responsibilities of all countries to report outbreaks of communicable diseases promptly and accurately.T

he world must understand that the Hong Kong protesters and the huge numbers of persecuted Uyghurs in their concentration camps (which China denies) are not freakish aberrations from some almost uniform munificence of the Peoples’ Republic.

They are the successors to other completely inoffensive groups who have been trampled underfoot, oppressed and traduced by the Beijing regime, from the long Civil War (1920s-1949) through the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), the occupation of Tibet and persecution of practitioners of all the world’s religions, especially Christianity, but also authentic Chinese religions.

There are limits to what the world can reasonably aspire to do in jurisdictions that are not our own and boil down ultimately to Chinese internal affairs. But this attempt of the Chinese government, as it blames the United States for this debacle and threatens to be sluggish about the transmission to the United States of medical supplies produced in China by American companies it had induced to invest there, requires a sharp rejoinder.

Where this creates a conundrum for the United States is that although all Chinese comments on the coronavirus have to be somewhat, or even substantially, discounted, China’s partially plausible claim that it has turned the corner and that the virus is now in retreat, is extremely useful in combating the profound panic which is sweeping the United States and the entire Western world.

In democratic countries, the media are free to hype any version of events, no matter how terrifying, and the temptation to do so in the United States is aggravated by the possibility presented to the anti-Trump media to hammer the president for incompetence and deception in an election year, and destroy the benefits of his skillful management of the economy.

This is going to require the administration to execute the sophisticated maneuver of exposing China’s duplicity and negligence, while citing the fact that even despite the Beijing regime’s blunders and disinformation, the incidence and impact of the coronavirus are clearly now declining in China.

Proper emphasis on this point will close the door that has been hurled open to unlimited panic. It has been impossible to steady the country’s nerves, and especially the shaky-legged, sweaty-palmed managers of the nation’s and people’s money, who flee like asphyxiated cockroaches whenever any threat appears that can’t be measured precisely.

The prudent course is to assume the worst and plan and act for it. But when the worst is indiscernible, the usual response is for the great money-managers to drink the Kool-Aid of outright panic, and flee to the front of the unsettled masses and lead them over the cliff. This can be combated in only two ways: a plan of believable action based on the assurance that the country possesses the ability to deal with the problem—FDR’s genius exhortation that “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself, nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.

"As he said at his first inauguration on March 4, 1933, our "difficulties, thank God, concern only material things." That is not the case here, and no one knows exactly where this might end since it is distinguishable from previous pandemics. Where the danger could be infinite, the Roosevelt response is not a complete solution.

This is why, as China’s official misconduct, ineptitude, callousness, and deceit must be highlighted, the demonstrably finite character of the coronavirus threat must also be emphasized.As a completely legitimate reference point to cure panic and focus on “flattening the curve,” as the scientists say, we are doing what China did not do: take every appropriate action to minimize the human damage and shorten the life of the crisis.

And this is where the second paradox arises: the commendable scientists, who are senior in managing the official American response, seek the most radical measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.This is natural.But the possibility of a shut-down on almost the entire population, which is already in effect in Italy, France, and Spain, and is creeping upward in the United States also, reduces the likelihood of severe attacks of an influenza that is often much nastier than any flu but is not life-threatening to more than a tiny fraction of healthy people beneath the age of 70.

This will shorten the duration of the medical crisis. But we saw in China that it also strangles the economy, which collapsed for at least two months—there were almost no sales and little production of durable goods in China during that time.The remit of the scientists is to end the medical crisis, but the administration has the challenge of imposing total risk-avoidance measures on the susceptible elements of the population (the infirm and elderly), and urging those with minimal chance of serious, much less, mortal illness, to pursue their occupations as best they can on as risk-free a basis as they can.These are delicate balances the administration will have to sort out.

The results of the national voluntary mobilization the administration has led are already emerging. A preliminary vaccine was tested on Monday in Seattle, and the ability to test Americans — which had a very wobbly beginning, aggravated by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar’s promise of four million tests last week, the almost complete failure to occur he blamed, a bit unconvincingly, on a "less seamless" passage from production to application — seems to be coming in a week late.

Tests are not cures.They’re only useful for quarantining, and a person who is virus-free today may be infected tomorrow. But the psychological impact of the testing failure and the reflection on the administration’s credibility and competence were significant, but not irreversible.I predict that the administration will thread this needle and that the coronavirus crisis will be seen to be receding before the end of May.

1 note

·

View note

Text

12 Horror Bollywood Films That You Can not Watch Alone.

The Bollywood blood and gore movie industry has a rich history, returning to the fifties. In any case, because of a few perspectives, the standard took a gander at loathsomeness with a scorn.

Through the seventies, eighties, and nineties, the A-Listers never joined a blood and gore movie. That made an entirely different arrangement of on-screen characters who'd do Bollywood blood and gore movies - and they had a religion following.

Since the on-screen characters were new, the spending limits were less. Since awfulness is a saleable class, the more significant part of these thrillers became moneyspinners for the makers and lenders.

With fresher ability coming in, makers searching for a fast jettison started agitating backward and exploitative film, Bollywood frightfulness got notorious. In the nineties, chiefs like Ram Gopal Varma and Vikram Bhatt revolutionalized the repulsiveness class with their movies.

Here are the five films that changed the crowd's point of view of an Indian thriller.

# 1 Stree

Dinesh Vijan coordinates this content by Raj Nidimoru and Krishna DK. Before this, no one prevailing with regards to making a certifiable blood and gore movie with satire components. Stree was a moment hit and resuscitated the loathsomeness fragment in Bollywood. The film stars Rajkummar Rao, Shraddha Kapoor, and Flora Saini.

#2 Raaz

This Dino Morea and Bipasha Basu film changed the layout of blood and gore movies. Prior, thrillers were about a detestable soul frequenting the group of somebody who wronged them. In Raaz, the purpose of the intelligent soul's presence was a wrongdoing submitted or bad form allotted by the ones who are being spooky. The striking, new age slurped up this thought, preparing for India's most well-known establishment.

#3 Go Goa Gone

first, sufficient blood and gore movies to include comedic components and pull off it. The intellectuals called it dark cleverness, and the standard parcel saw the episodes portrayed in the film occur with them consistently - separated from the zombie end of the world. Today, it makes the rundown of the most needed Indian loathsomeness continuation films. Go Goa Gone responded to a relevant inquiry - for what reason do zombies assault Western nations? With Go Goa Gone, India got it is first useful, engaging, and establishment commendable zombie film.

#4 Pari

For three decades, Indian awfulness makers utilized the wash-flush recurrent equation. They couldn't dive into the rich Indian culture for characters and story circular segments. There was this danger of harming feelings. By one way or another, Anushka Sharma dared to get into Islamic history and make Pari, a genuinely alarming film.

This is just the second Bollywood thriller that was a creepy encounter to watch in the theater, second only to Stree.

#5 Veerana

Entertaining yet evident, this film is as however, discussed four decades after its discharge. That puts it at standard with Sholay - well, nearly. The Ramsays made a few repulsiveness layout films like Purana Mandir, Purani Haveli, Shaitaani Ilaaka, and some more. Ut BVeerana is the one each Indian frightfulness buff thinks about. Everything considered, there's no motivation behind why Veerana turned out to be so celebrated, aside from the way that there's a fear inspired notion that the courageous lead woman, Jasmine, has vanished someplace. Possibly that is the explanation frightfulness clubs adore it.

6. Ragini MMS

Ragini MMS is roused by the American otherworldly awfulness 'Paranormal Activity' and is somewhat founded on an original story. In contrast to its continuation, this one didn't have Sunny Leone, yet at the same time figured out how to attract the groups to the venues on account of its edge-of-the-seat thrills. This sleeper hit can give you a couple of restless hours when you hit the bed around the evening time.

7. 13 B

13 B comes stuffed to the rafters with spine-shivering chills and alarms. It doesn't rely upon a creepy foundation score or abnormal camera points to convey the chills. With a reliable content and a group cast that carries out its responsibility to flawlessness, 13 B is unquestionably one motion picture you shouldn't miss.

8. Mahal

Considered as the main blood and gore flick of Bollywood, Mahal manages the subject of resurrection. This one likely terrified your daddy too your dada. Indeed, even with moderate impacts, this film has kept on frequenting crowds for a considerable length of time.

9. Bees Saal Baad

A secretive lady strolling around at midnight through a field murmuring Kahin profound jale kahin dil scared the country so much that the film ended up being the most elevated grosser in 1962. Inexactly dependent on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's 'The Hound Of Baskerville', Bees Saal Baad stays each piece frequenting considerably after pachas saal baad of its discharge.

10. Horror Story

A gathering of adolescents chooses to go through the night at a spooky inn. Things get tangled, and it's a panic fest consequently. Some alarming scenes will make you bounce off your seat. Those searching for chills won't be frustrated by any stretch of the imagination.

11. Shaapit

The third portion in the Raaz set of three, Shaapit, is adequate to raise the hair on the rear of your neck. Like each Vikram Bhatt film, the USP of this film lies in its treatment, keeping it gorgeously ghostly. Before the finish, you should have faith in condemnations and insidious spirits.

12. Ek Thi Daayan

The idea of daayans existing in the public arena is creepy in itself. Ek Thi Daayan is a daring endeavor at taking a stab at something new. It is a combination of a pureblood and gore movie and a dreadful, paranormal spine chiller. The extraordinary dramatization may appear to be unreasonable; however, the stylized treatment and the tight storyline compensates for it, also Konkona Sen's shocking depiction of a day. Creepy undoubtedly!

1 note

·

View note

Text

"The Age of American Unreason in a Culture of Lies" Susan Jacoby

BowieBookClubの5月の本。まず2008年に出版され、今年の頭に new updated edition が出た。2008年版が図書館にあったので、まずそれを借りてイントロと結論の頭を読んで、著者がトランプについて、そしてトランプを選んだアメリカ国民についてどう書いているかを読みたくて2018年版を購入(1,807円也)。

すっごく興味深く非常に面白かった。

ただ、著者、ボキャブラリーが恐ろしく広く、わざと難しい単語を使うのに慣れ切っていて、また、長くてややっこしい文章を書く習慣がついているようで(私が学生の頃あんな文章書いたら、三つに切れと指導を受けていたような、世界で一番長くまどろっこしい言い回しの文章もあった)、本の半分くらいまで読みにくくて仕方なかった。久しぶりにこの手の本を読むからもあるだろうが、私個人に知識のある事柄についての章はまだ読みやすかったので、私の英語力と理解力に問題があるのではなく、内容と文章のタイプに問題があるのだと全部読んで思った。

で、トランプを選んでしまったのは、トランプに投票したタイプの人々は、トランプと同じタイプの人間で(彼はトランプを"one of us"と感じている)、トランプはTV好きで、本を読まず、何百ページにわたる資料をもっと短くできないのは無能だ的な反応をして読んでいるのか読んでいないのか、そして、ネットに流れるウソ情報の真偽を問わずに自分に都合のいいものを信じ、外国語を話す必要などなく、本と言うものを(娯楽小説すら)読まない、平たく言ってバカが、仲間のバカを選んだのだ。バカで知識人にアレルギーがあるのがmiddle of nowhereの平均的なアメリカ人なのだそうだ。

数学と科学の知識が低く、国の歴史を教える学校が少なく、音楽の授業はなく、アメリカの学校、全部が全部そうでないのはわかってるが、ひどいなぁ。ま、日本の公立学校も出来ない子はできないまんまだが。

ネットとポピュラー・カルチャーに関する下りは、考え方が既存のhigh artにとらわれ過ぎてると思った。今残っている歴史的芸術作品は、全て淘汰されて残ったもので、だから、その作品が生まれた当時にはピンからキリまで悪いのもたくさん巷にあり、鑑識眼がない人などが駄作でも有難がっていたと思われる。それに今残っている芸術作品のほとんどは、選ばれた人々(王族、貴族など裕福な層)だけのものだった。それがポピュラー・カルチャーは大衆のもので、そして、その中から大衆がよしとする芸術性の高いものが生まれて、そこから新しい芸術が生まれる可能性もあると思う。(実際は、現代芸術を借用する方が多いようだが)

文学と現代の娯楽小説を比べるのもおかしいと思う。『アンナ・カレリーナ』が出版され広く読まれていた当初も、大衆が気軽に読む小説があった筈だ。と、ここら辺が気になった。

しかし、この本、読むの疲れた。18日に届いて、27日に読み終えた。時間と体力のあるときは4時間近く読んだ日もあったかもしれない。平均、連日2時間はこの本を読んだ。(1日だけ疲れてしまって、10ページしか読まない日もあった。)しかし、1日でも読まないと、もうこの本を手に取らなくなるかもしれないと思われて、急いで読んだ。

読んで良かったが、この著者の本をまた読みたいかどうかは非常に疑問だ。

#The Age of American Unreason in a Culture of Lies#The Age of American Unreason#Susan Jacoby#English

0 notes

Text

thatchapstickchick replied to your post “There's this weirdness I'm seeing with people who come to secular...”

I feel like it's part of a broader cultural shift in which nobody wants to recognize the knowledge/wisdom of experts or authorities anymore. And I mean on one hand individual empowerment is great, but on the other... people study and train to get expertise for a reason.

An interesting take as we are in another wave anti-intellectualism. Ian B was reading a Susan Jacoby book about it and it appears the book has been updated and re-released last week. The Age of American Unreason in a Culture of Lies. Asking people to be thoughtful is not an attack, but I actually got blocked by people in a few witch groups on facebook for being critical of certain books. It also goes along with learning the rules so you can break them.

I’m still just really confused that people would do a spell or a ritual and be shocked -- SHOCKED! That they might get tired or feel weird. Like, surprise! You are actually doing a thing!

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

[AUDIOBOOK] Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs

Esteu buscant aquest llibre?

The Age of American Unreason in a Culture of Lies By Susan Jacoby

Book Excerpt :

NATIONAL BESTSELLERThe prescient and now-classic analysis of the forces of anti-intellectualism in contemporary American life--updated for the era of Trump, Twitter, Breitbart and fake news controversies.The searing cultural history of the last half-century, The Age of American Unreason In A Culture of Lies focuses on the convergence of social forces--usually treated as separate entities--that has created a perfect storm of anti-rationalism. These include the upsurge of religious fundamentalism, with more political power today than ever before; the failure of public education to create an informed citizenry; the triumph of internet over print culture; and America's toxic addition to infotainment. Combining historical analysis with contemporary observation and sparing neither the right nor the left, Susan Jacoby asserts that Americans today have embraced "junk thought" that makes almost no effort to separate fact from opinion.At today's critical political juncture, nothing could be

>>> START READING NOW

"This book is available for download in a number of formats - including epub, pdf, azw, mobi and more. You can also read the full text online using our Ereader."

#MUSTREAD, #MOBIPOCKET, #DAILYBOOK

0 notes

Text

Third Prize: Zhao Nan

Prompt 2: As a Chinese and an incoming international student, why does social justice in the United States matter to you?

The news about George Floyd has raised the issue of social justice under the media spotlight. I already watched the controversial video on social media even before the news broke out in China. As I watched the video, anger instantaneously took over my mind. While I know racial discrimination exists, witnessing such injustice play out over and over again still saddens me deeply every time I watch the news. What was unexpected about the news of George Floyd was the unprecedented international public attention brought about by such tragic incident As I browse through the heated discussions about George Floyd online, I realize that, this time around, there might actually be a change on the rise, as more people have become aware of social justice and equality.

At school, I have likewise heard conversations regarding the said news. As an incoming international student, social justice is of great significance to me, not only because that the United States is potentially where I will be going for college, but also because of its larger social implication?

Currently, social justice remains a huge unresolved problem. I have already came to know several tragedies caused by racial discrimination and stereotyping, most of which are not really far from my own experiences. The most recent prominent example is Covid-19. The pandemic has hurled unreasonable complaints against the Chinese. For quite a few times, I have heard from my friends who are currently studying abroad that they are being discriminated against by the locals. The United States, regarded the “number one” country, has sufficient power and influence to lead. As the US has begun heeding notice on social justice, I can definitely see more countries worldwide see more people around the world speaking out against racial inequality in the future. In this day and age, racial discrimination against the Chinese is heightened due to the ongoing trade war and the pandemic. International students, including myself, are going to confront this problem until the day when racism no longer exists. The existing condemnations and denunciations against the demise of George Floyd has given me hope that such day will come.

Personally, I believe that a stereotype is not merely an opinion; rather, it is rooted deep inside a culture and in history. Regardless of how firmly we disagree with it, fight against it, or ignore it, there is no way we are unaffected. Indeed, we live under certain stereotypes, as we are all victims of it.

Apart from concerns over safety and equal opportunity, another dilemma amongst incoming international students is self-identity – that is, the way we perceive ourselves. Initially unnoticed, our identity has since changed. We have gradually adapted to the English language, learn the American accent, and use international social media platforms. Everything that we have attached ourselves to has to become familiar.