#Théroigne de mericourt

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My artblocj is over chat

Sketches under cut

I felr soo good drawing these

#napoleonic wars#napoleonic era#napoleonic shitpost#frev#frev shitposting#jean andoche junot#louis nicolas davout#napoleon bonaparte#duke of wellington#arthur wellesley#théroigne de mericourt#saint just#louis antoine de saint just#jean paul marat

108 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WOAH

One of the early feminine notabilities of 1789 who had not ceased to bestir herself, Mlle. Théroigne, very well known in Paris, owing especially to her democratic sentiments, having become suspected of backsliding, was arrested by the populace and brought before the committee with headquarters at the Feuillants, to the repeated cries of “To a lamp-post with her!” The crowd became so great, so considerable and threatening, that the members of the committee despaired of saving the unfortunate amazon; when Marat arrived on the scene the danger was imminent even for the members of the committee, who were delaying handing her over to the mercies of the mob.

Marat said to them, “I will save her.” Leading Mlle. Théroigne by the hand, he showed himself to the enraged people, saying, “Citizens, are you bent on attempting the life of a woman? Are you going to sully yourselves with such a crime? The law alone has the right to strike. Show your contempt for this courtesan and resume your dignity, citizens.” The words of the friend of the people quieted the gathering. Marat, taking advantage of this moment of calm, dragged Mlle. Théroigne away and led her into the hall of the Convention, his bold action saving her life.

Paul Barras, Memoirs

#how do i put this to favourite#like favourite post#frev#jean paul marat#Théroigne de mericourt#i need to know more..#he held her hand?!?!?!

87 notes

·

View notes

Note

Long while back, you answer a question about inspiration for Madame Defarge in the novel "A Tale of Two Cities" and I guess it just stuck in my mind since I was just reading about political cartoonist of the day savaging of Theroigne de Mericourt and Olympe de Gouges and these cartoons may have helped Charles Dickens in his creation of the vengeful tricoteuse Madame Defarge (Thérèse from Theroigne and Defarge from de Gouges), but didn't much more about them?

I'm guessing you're talking about this post.

Theroigne de Mericourt was a leading French revolutionary, who was heavily involved in forming mixed-gender and women's political clubs. She became quite famous when she was arrested by the Austrians and rather violently interrogated as a supposed instigator of the Women's March on Versailles. She returned to France a revolutionary martyr, spent some time trying to recruit women's revolutionary battalions, and then was involved in the Insurrection of August 10th, where republican forces stormed the Tuileries Palace and forced the abolition of the monarchy.

While initially quite close to the Jacobins, Théroigne allied with the Girondins and was assaulted by pro-Jacobin women, requiring Marat's rescue. However, the head injuries she suffered during the attack led to increasing mental issues, and she was institutionalized from 1794 until her death in 1817.

I do find it interesting that, if Dickins did base Defarge on Théroigne, he left out the major (and visually dramatic) aspect of her public persona - her habit of wearing men's clothes, which was a constant theme of both her negative and positive press. (Lots of classical references to Amazons.)

If Théroigne was the street-fighter and orator, De Gouges was the intellectual. A voluminous playwright and pamphleteer and a constant fixture of the leading salons of Paris, De Gouges was probably best known for her "Declaration of the Rights of Women and the Female Citizen" - which criticized the misogyny and patriarchy of male revolutionaries and called for equal rights for women.

Like Théroigne, De Gouges was a leading member of the Amis de la Verité, the most prominent women's political club in Paris. In addition to her advocacy for women's equality, De Gouges was a leading abolitionist and was accused of having incited the Haitian Revolution with her anti-slavery plays, which is just wild.

However, De Gouges lost a lot of political capital for opposing the execution of the King and preferring constitutional monarchy to repiblicanism. Like Théroigne, De Gouges backed the Girondins and criticized the Montagnards in the press - which led her to being arrested as a royalist, put on trial for sedition and monarchism, and ultimately executed by order of the Revolutionary Tribunal.

I don't think De Gouges is a good fit for Defarge - not only was she firmly bourgeois rather than sans-culotte, and the furthest thing from a Jacobin radical, but there's not a trace of De Gouges' literary and theatrical background in Defarge.

So yeah, if these women were the basis for Dickens' Defarge, he didn't do a very good job of highlighting the things that made them famous in the first place.

#history#historical analysis#french revolution#theroigne de mericourt#olympe de gouges#charles dickens#a tale of two cities#madame defarge#french history

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reminder that the only fictional depiction of the Club des Jacobins being attacked and closed I can think of is the CRIMINALLY HORRENDOUS VERSION created by Assassin's Creed Unity in which Evil Robespierriste Jacobin Men whip Théroigne de Mericourt who then leads the assault on the Club that only had men inside (of course) which, as the game player and protagonist, you are made to support the same way you helped engineer the Thermidor coup.

This level of historical distortion should be criminal.

#fictional representations#assassin's creed unity (2014)#assassin's creed unity#fuck that horrendous reactionary game#thermidorian reaction#thermidor

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

I read a crappy book that was supposed to tell me something about theroigne de mericourt but i was left with nothing except the certainty that the author was very misogynistic. Do you have any recommendations (post, books, whatever) to learn about her properly? Thanks

Étude historique et biographique sur Théroigne de Méricourt: avec deux portraits et un fac-similé d’autographe (1886) by Marcellin Pellet

Trois femmes de la Révolution: Olympe de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (1900) by Léopold Lacour

La Vraie Théroigne de Méricourt (1903)

A woman of the revolution: Theroigne de Méricourt (1911) by Frank Hamel

The women of Paris and their French Revolution (1998) by Dominique Godineau

Liberty: the lives and times of six women in Revolutionary France (2006) by Lucy Moore (chapters 3 and 6)

All of Méricourt’s identified works, of which three have been digitalized

Camille Desmoulins talks about Méricourt and summarizes one of her speeches in number 14 of Révolutions de France et de Bravant (1790)

Article on Méricourt by Women in the French Revolution: a resource guide

Article on Méricourt by BNF Gallica

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT wait WHAT

I’m having a stroke over Theroigne and Collot being ex-buddies

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Europe: A History by Norman Davies

specifically, the section on the French Revolution

Okay, it’s pretty clear from the start that Davies is a Girondist sympathizer, with phrases contrasting the “republican Girondins” against “Robespierre’s extremist Jacobins.” He also lists Charlotte Corday with other revolutionary women such as de Gouges and Théroigne de Mericourt (and yes, I know her actual ties to the Girondin party are debatable, but the motivations were similar).

Davies also despises Robespierre - nothing new there - calling him the “chief terrorist” along with several other lovely epithets. Davies’ version of Robespierre is a sexist, extremist, violent dictator who deserved everything he got. In a passage describing the last words of the revolutionaries, he mocks Robespierre and talks about his “incoherent shrieking” he had just gotten his lower jaw shattered by a bullet you absolute dickhead please shut up forever

In a particularly horrifying section, Davies compares Carrier’s noyades to the WWII death camp Treblinka (don’t do that. both were obviously despicable. very different scenarios.)

then there was just the weird stuff

Davies writes Théroigne as “Thérouingue” and Marat as “Jean Marat”

“fiery orator Camille Desmoulins” - he...had a speech impediment, and most of his work was done through writing, because he was a journalist. what

(also he claims Desmoulins was 38 at his death which is just...a failure at basic subtraction)

k i’m done now

#ari babbles#frev#french revolution#adventures in the local library#robespierre#desmoulins#camille desmoulins#charlotte corday

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Most underrated duo in the french revolution

MARAT SAVED HER LIFE GANG I CANNOT DO THIS

#théroigne de mericourt#anne joséphe théroigne#jean paul marat#marat#frev#french revolution#frev shitposting#frevblr#OUGH MY SHAYLAAASSS#i love them so much

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's time to share the results!

Together with @frevandrest we are honoured to announce the winner (democratically elected himbo)

Bonbon Robespierre (21 votes)

Camille Desmoulins (17 votes)

Hérault de Sechelles and Théroigne de Mericourt (both with 7 votes)

Congratulations to the official himbos of French Revolution chosen by our community! All the candidates proved their himbo potential and deserved to be nominated. Honorable mentions include, in order of votes received: Georges Danton, Jean-Lambert Tallien, Elisabeth Duplay, Arthur Dillon, Felix Lepeletier and Charlotte Robespierre. You can see the results by opening this link.

Who is the biggest himbo of the Revolution? Nominate your choices for a ginger cat of the frev.

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Game:

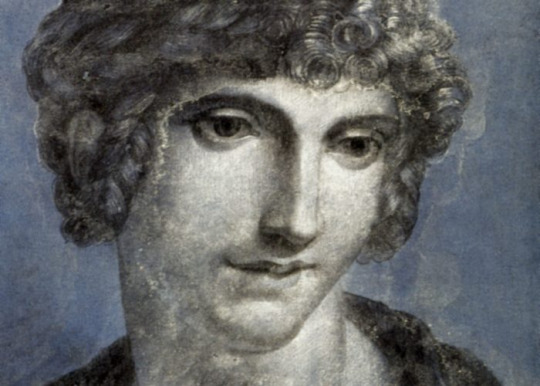

Anne-Josèphe Théroigne de Méricourt, born Anne-Josèphe Terwagne, was a Belgian singer, orator and organizer active in Paris at the time of the French Revolution. During this tumultuous period, she became known as a defender of the poor and a fierce advocate for women's rights.

When hunger and despair pushed market women to march on Versailles on October 5th, 1789, Théroigne and one of her allies joined them in their protest. As Théroigne's reputation preceded her, several men attempted to deter her on her way to the city gates, though the Assassins ensured she and the march could proceed peacefully all the way to Versailles. As a result, king Louis XVI was forced to move to Paris along with his family and the National Assembly. Théroigne herself regularly attended the Assembly and thus moved from Versailles to Paris as well.

In the summer of 1792, Théroigne uncovered a conspiracy orchestrated by Templars that intended to sow chaos by starving Paris' citizens, turning them against each other. Tracing the group's activities for over a month, she was led to Flavigny, a woman who had assumed the guise of a couturiere to carry out her operations. Théroigne presented her findings to the National Assembly, but they did not believe her, forcing the revolutionary to take action herself.

Set on eliminating Flavigny's agents, Théroigne traveled to an address in the Hôtel-de-ville district that she had determined, but not before leaving a message for the Assassins, of whose presence she was also aware. Entering the building, she ended up being outnumbered, but was saved by the timely appearance of the Assassins. Together, they eliminated Flavigny's men and secured the stolen food, following which Théroigne told the Assassins of Flavigny's location, trusting them to take the Templar out.

Later, Théroigne found out about a gunsmith designing weapons for the Templars. In response, she asked the Assassin Arno Dorian, who had previously aided her, to kill the gunsmith and retrieve the blueprints. In this way, her own Parisian militia would be able to manufacture more advanced weaponry for themselves. Desiring to establish an army of women, Théroigne would call on Arno once more in 1793, asking him to distribute recruitment handbills at various brothels.

In Real Life:

Théroigne de Méricourt was born Anne-Josèphe Terwagne on August 13th, 1762 near Liège to Pierre Terwagne and Anne-Elisabeth Lahaye. Her mother died when she was five following the birth of one of her brothers, so Anne-Josèphe was sent to live with an aunt, who didn't really want her. First, she sent the little girl to a convent, but later, perhaps to save money, she changed her mind and brought her back to live with her. But rather than giving her a loving home, Anne-Josèphe was treated like a maid.

When her father remarried, he welcome her back home. His new wife didn't. Too busy taking care of her own children, she didn't care much for Anne-Josèphe. So, desperate for affection and a real home, she went to live with her maternal grandparents. But things didn't work out there either. As a last resort, she returned to her aunt. Needless to say, the arrangement was a disaster. Anne-Josèphe then decided to face the world on her own, and took any job she could to support herself. Eventually, she was hired by a certain Madame Colbert as her companion. Madame Colbert taught her to read, write, play the piano, and sing. Anne-Josèphe now dreamed of becoming a singer.

However, in 1782 she met an English officer. He took her off to England with promises of marriage that he had no intention of keeping. During this time, she was also kept by the old and unpleasant marquis de Persan, who showered her with expensive gifts and money (although she insisted she had evaded his advances). Her reputation in tatters and any hope of a respectable life gone, Anne-Josèphe become a courtesan and called herself Mlle Campinado. Her affair with the Englishman continued and resulted in a child who died, probably to the relief of his father who had refused to acknowledged her, of smallpox.

(Image source)

After a brief affair with an Italian tenor, she fell for the castrato Tenducci and, in 1788, followed him to Genoa, hoping to start a musical career there, but she only gave a few concerts. After a year, she returned to Paris, alone, disappointed, and hurt. All her dreams, both professional and romantic, were shattered. Her hopes vanished. Or so she thought until she set foot in the city. Paris was on the verge of revolution. It was an exciting time that seemed to promise her a better, more just, world, and the opportunity to take control of her destiny and rescue her from the life of unhappiness and abuse she had so far known. That summer, Anne-Josèphe transformed herself. She ditched her gowns in favour of a white riding habit called amazone, and a round-brimmed hat, an eccentric outfit that made her stand out from the crowd. She wanted to "play the role of a man’, she later explained, because I had always been extremely humiliated by the servitude and prejudices, under which the pride of men holds my oppressed sex’". She also gave up her job as a courtesan, and pawned her jewels to support herself. After the storming of the Bastille, she became involved in revolutionary activities. She attended the meetings of the National Assembly every day. She was the first to arrive and the last to leave, and met many influential figures of the Revolution, such as Pétion, the Abbé Sieyès, and Desmoulins. Anne-Josèphe played a big role too. She sometimes spoke at the Cordeliers Club, founded her own club, and ran her own saloon. Soon, she was a celebrity. It's at this time that she became to be known as Théroigne de Méricourt.

(Image source)

Although Théroigne believed in the ideals of the Revolution, it soon became clear that most of its supporters were only interested in the rights of men, not of women. The press, scared of emancipated women, started portraying her as a whore, heaping all sorts of insults, accusations, and obscenities at her. In disgust, in the summer of 1790, Théroigne left Paris and returned to Liège. If she hoped for some peace and quiet, she was bitterly disappointed. Liège was then under the control of the Austrian Empire, not a safe place for such a prominent and famous figure of the Revolution. She was kidnapped by mercenaries and taken to Austria. The journey lasted 10 days and was harrowing. The three French emigrés insulted, harassed, and even tried, luckily unsuccessfully, to rape her.

Once in Austria, Théroigne was interrogated, over the course of a month, by François de Blanc. Hoping to discover important information about the French Revolutionaries, de Blanc, who believed all the nasty rumours about her prisoner, spent many hours talking to her and examining the papers that were found on her when she was caught. But he soon realised she knew nothing important. More surprisingly, he began to like her. Worried about her health - Théroigne suffered from depression and splitting headaches, coughed up blood and had trouble sleeping - he helped secure her release.

At the beginning of 1792, Théroigne was back in Paris. She now supported Brissot, a Girondin, against Robespierre, and gave many an inflammatory speeches in the Jacobin Club in which she called for the liberation of women from oppression. But this time, she didn't just fight with words. She recruited an army of female warriors, and took part in the storming of the Tuileries on 10th August. It is said that she wounded a royalist journalist who had insulted her in the press. He was then killed by the mob. But she didn't support the September Massacres, believing all this unnecessary violence was hurting the cause of the Revolution. She wanted it to stop, but it didn't. Things got worse for Théroigne. In May 1793, a bunch of Jacobin women who hated the supporters of Brissot and the Girondin, attacked Théroigne in the gardens of the Tuileries. They stripped her naked and flogged her publicly. Only the intervention of Marat saved her.

(Image source)

Théroigne's mental health had always been fragile. Now, she descended into madness. In the spring of 1794, she was arrested. She became obsessed with Saint-Just, thinking of him as her saviour, but he did nothing to help her. She was eventually released from prison after the fall of Robespierre, but never recovered her sanity. That year, she was officially declared insane. She spent the rest of her life in various asylums, and was ultimately sent to La Salpêtrière Hospital, where she lived for twenty years. All she spoke about was the Revolution. She still clang to her revolutionary ideals, even though everyone else had abandoned them. Théroigne died, following a short illness, on June 9th, 1817.

Sources:

http://www.amazingwomeninhistory.com/theroigne-de-mericourt/

http://cultureandstuff.com/2012/02/08/theroigne-de-mericourt-the-fatal-beauty-of-the-revolution-part-one/

http://historyandotherthoughts.blogspot.com/2015/05/madness-and-revolution-sad-life-of.html

http://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/theroigne-de-mericourt-anne-josephe-1762-1817

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Counter-Propaganda Post 21

Dear Mr. Andrew Roberts,

I acknowledge that you are trying to tell the biography of Napoléon Bonaparte, however I noticed that you made multiple historical oversimplifications and inaccuracies when you were talking about the life of Napoléon Bonaparte.

For instance, I noticed you made an oversimplification about the Napoleonic Code when you said, ”In Fance, he established the Code Napoleon, a distillation of 42 completing and often contradictory legal codes into a single body of French law.” Yes the Napoléonic Code did bring a lot of reforms to France in a time of chaos, however are you aware that the Napoleonic Code trampled the progress that women made in the French Revolution. For example, according to the Conversation, at the beginning of the French Revolution many women participated in the Revolution through marches and writing and figures such as Anne-Josèphe Théroigne who rushed from Rome to Paris to participate in the Revolution in 1789 where she spoke at rallies. There she spoke about Women’s Rights.

However, this progress was reversed when the Napoleonic Code was instituted and it delayed women’s progress in civil rights by 150 years where according to Britannica, “The code subordinated women to their fathers and husbands, who controlled all family property, determined the fate of children, and were favoured in divorce proceedings. Many of those provisions were reformed only in the second half of the 20th century.”

Are you also aware that the Napoleonic Code reinstated slavery in France and its colonies in spite of slavery being abolished where according Slavery and Remembrance.org, “In February 1794, the French republic outlawed slavery in its colonies. Revolutionaries in Saint-Domingue secured not only their own freedom, but that of their French colonial counterparts, too.” But after Napoleon came to power through a coup d’état he reinstated slavery where according to Thoughtco.com, “Freedom and the right of private property were key, but branding, easy imprisonment, and limitless hard labor returned. Non-whites suffered, and slavery was allowed in French colonies” (Wilde).

And finally, I also noticed an oversimplification of the fall of Napoléon Bonaparte, where you only mentioned one factor of the Downfall of the French Emperor. Which was the failed invasion of Russia, but are you aware there were other factors that lead to the end Napoleon's reign. For example, there was the Peninsular War where according to History.com, it was a guerilla war fought between the French Napoleonic army and Spanish guerilla fighters that we're aided by the British. The war resulted in a Spanish guerilla victory and was a crushing defeat for the French where according to Britannica.com, they withdrew 30,000 troops.

Sincerely,

Kyle Titus

Wilde, Robert. "A History of the Napoleonic Code (Code Napoléon)." ThoughtCo, Sep. 30, 2019, thoughtco.com/the-napoleonic-code-code-napoleon-1221918.

“French Revolution.” Slavery and Remembrance, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, ND, http://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0065.

Mcphee, Peter. “Hidden women of history: Théroigne de Méricourt, feminist revolutionary.” The Conversation, The Conversation US, Inc, 31st of December 2018, https://theconversation.com/hidden-women-of-history-theroigne-de-mericourt-feminist-revolutionary-107802.

“Peninsular War.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 21st July 2010, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/french-defeated-in-spain.

“Peninsular War.” Britannica.com, Encyclopædia Britannica inc, Apirl 28th 2019, https://www.britannica.com/event/Peninsular-War.

Bias Check of Sources used for research.

Van Zandt, Dave. “Thoughtco.” Media Bias Fact Check, Media Bias Fact Check, LLC, 21st of February 2018, https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/thoughtco/.

Zandt, Dave. “Britannica.” Media Bias Fact Check, Media Bias Fact Check, LLC, 17th of June 2019, https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/encyclopedia-britannica/.

Zandt, Dave. “The Conversation.” Media Bias Fact Check, Media Bias Fact Check, LLC, 10th of July 2016, https://mediabiasfactcheck.com/the-conversation/.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Es hora de que las mujeres salgan de la bochornosa anulación | Théroigne de Méricourt

Es hora de que las mujeres salgan de la bochornosa anulación | Théroigne de Méricourt

«Por fin es hora de que las mujeres salgan de la bochornosa anulación a la que están sometidas desde hace tanto tiempo debido a la ignorancia, el orgullo y la injusticia de los hombres.» Théroigne de Méricourt (Marcourt, Bélgica, 13 de agosto de 1762 – París, Francia, 9 de junio de 1817) Nacida Anne Josèphe Terwagne y también conocida como Lambertine, Théroigne de Méricourt fue una cantante,…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Note

On her French wiki it says that Theroigne de Mericourt held a salon that Saint-Just (as well as Camille) attended. I’ve also seen in other websites regarding her that either right before or right after Theroigne was sent to an asylum she wrote a letter to Saint-Just. Do you know how based on fact either of these events are? And do you know anything else about Theroigne and Saint-Judy’s relationship? I knew her and Camille were friendly but I never heard about her and Saint-Just until I saw that on wiki and got curious. Thank you!

I found the following letter from Theroigne to SJ cited in A woman in the revolution: Théroigne de Méricourt (1911). It is dated July 26 1794 and was found among Saint-Just’s papers after his death:

Citizen Saint-Just, I am still under arrest. I have lost precious time. I have written to you to beg you to send me two hundred livres, and to come and see me. I received no reply. I do not feel much gratitude towards the patriots for leaving me here, bereft of everything. It seems to me that they ought not to be indifferent that I am here, and that I am doing nothing. I sent you a letter in which I say that it is I who said I had friends in the palace of the Emperor, that I was unjust as far as Citizen Bosque was concerned, and that I am sorry about it. They told me that I had forgotten to sign the letter. That was want of attention on my part. I should be charmed to see you for a moment. If you cannot come to me, if your time does not permit it, could I not be accompanied on the way to see you ? I have a thousand things to say to you. It is necessary to establish the union; it is necessary for me to develop all my plans, to continue to write as I have written. I have great things to say. I can assure you that I have made progress. I have neither paper, nor light, nor anything; but even then it would be necessary that I should be free to be able to write. It is impossible to do anything here. My stay has taught me something, but if I remain longer, if I remain longer without doing anything, without publishing anything, I should learn to despise the patriots and the civic crown. You know that there has been discussion, both about you and me, and that the proof of union is in the results. There must be fine writings to give strong impulses. You know my principles. I am grieved never to have spoken to you before my arrest. I presented myself at your house. They told me that you had moved. It is to be hoped that the patriots will not leave me a victim to intrigue. I can still repair everything if you will aid me. But it is necessary that I should be where I shall be respected, for they neglect no means of showing contempt for me. I have already spoken to you of my plan. Whilst waiting until this can be arranged, until I have found a house where I can be safe from intrigue, where I can be worthily surrounded by virtue, I beg that they will send me back home. I shall be under a thousand obligations if you will lend me 200 livres. Farewell.

Besides that, there does however not appear to exist much tying the two together. I found several books where Saint-Just was included on a list of people who would frequent Théroigne’s salon (1, 2, 3) but none of the authors cited a primary source for it. Camille was him too included on all these lists (and, according to Jules Claretie, was rumured by some authors to even have been Théroigne’s lover) but similarily, the only connection I’ve found between them is Camille praising Théroigne and transcribing one of her speeches in number 14 Révolutions de France et de Brabant…

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

33 notes

·

View notes

Quote

At the end of July, the sections and the fédérés from the provinces who had come to Paris to celebrate the 14 July demanded the deposition of Louis XVI. In the night of 9 to 10 August, the alarm sounded; Parisians and fédérés marched on the château of the Tuileries where the royal family resided. After a violent and bloody conflict, the insurgents were victorious. The monarchy was at an end. If 10 August 1792 was a day for men, women also took part in the assault, just as they had participated in the overthrow of the Bastille. A witness recounts: "I saw, an instant before the combat, an amiable and still young lady with a saber in her hand, standing on a rock, and I heard her harangue the multitude. Suddenly, thousands of women hurled themselves into the fray, some with sabers, others with pikes; I saw several kill Swiss guards there. Other women encouraged their husbands, their children, their fathers. This account is an exaggeration--there were not "thousands of women" among the assailants but several women who, here and there, saved the life of their fellow citizens and tore guns from the hands of the Swiss guards who defended the Château. Some women were founded, but more often they were held back by their companions than by the prospect of danger. The misfortune that befell Pauline Léon speaks eloquently here. After passing part of the night in her section, the young girl, armed with a pike, took her place in the rows of the battalion that went to the Tuileries, but she had to give up her arms to a sansculotte "at the request of all these patriots." Now that a citizenship without social exclusivity was about to be legally established, now that what had been constructed and acquired through struggle was going to take legal form, women were again excluded. And we can already sense the paradox in the fact that women, who were admitted to be members of the Sovereign people when the populace tried to recapture their rights, did not enjoy all those rights, inasmuch as they were women. However, women proved their courage on 10 August, to honor their conduct on the attack of Tuileries, the fédérés awarded a civic crown to three women. The first was none other than Théroigne de Mericourt. The second, Louise Reine Audu, hit by a bullet in the thigh, had already attracted official attention during the women's march to Versailles in October 1789 and was imprisoned at the end of that month. As for the third, her name still did not mean very much in the summer of 1792: unlike the first two, the twenty-seven-year-old actress Claire Lacombe had only lived in Paris for five months. Originally from a family of merchants in Ariège, she had, up until March 1792, successfully practiced her profession in Marseille, Lyon, and Toulon. Attracted to Paris by its fame as both a revolutionary and a theatrical capital, she had not remained a spectator, and on 25 July 1792, dressed as an Amazon (a style of dress common to both Théroigne de Méricourt and Louise Reine Audu), she had read an address to the Legislative Assembly, offering to combat the tyrants and asking for the arrest of General Dumouriez. Without work, she lived on her savings, regularly, attended Jacobin meetings, and was a member of the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes.

Dominique Godineau comments on women's involvement in 10 August in The Women of Paris and their French Revolution

#10 August#Théroigne de Mericourt#Louise Reine Audu#Pauline Léon#Claire Lacombe#French Revolution#French revolutionary women

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THIS IS A MOMNR IN HISTORY TAKE A PICRURE

One of the early feminine notabilities of 1789 who had not ceased to bestir herself, Mlle. Théroigne, very well known in Paris, owing especially to her democratic sentiments, having become suspected of backsliding, was arrested by the populace and brought before the committee with headquarters at the Feuillants, to the repeated cries of “To a lamp-post with her!” The crowd became so great, so considerable and threatening, that the members of the committee despaired of saving the unfortunate amazon; when Marat arrived on the scene the danger was imminent even for the members of the committee, who were delaying handing her over to the mercies of the mob.

Marat said to them, “I will save her.” Leading Mlle. Théroigne by the hand, he showed himself to the enraged people, saying, “Citizens, are you bent on attempting the life of a woman? Are you going to sully yourselves with such a crime? The law alone has the right to strike. Show your contempt for this courtesan and resume your dignity, citizens.” The words of the friend of the people quieted the gathering. Marat, taking advantage of this moment of calm, dragged Mlle. Théroigne away and led her into the hall of the Convention, his bold action saving her life.

Paul Barras, Memoirs

87 notes

·

View notes