#Sultan Ahmed Mosque

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul, Turkey

French vintage postcard

#vintage#tarjeta#briefkaart#istanbul#sultan ahmed mosque#turkey#postcard#photography#ahmed#postal#carte postale#sepia#sultan#ephemera#historic#mosque#french#ansichtskarte#postkarte#postkaart#photo

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

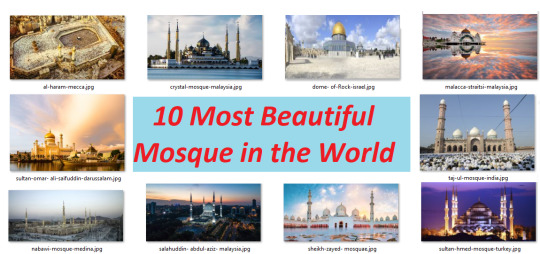

10 Most Beautiful Mosque in the World

The mosque, or the masjid, is where Muslims attend worship. Found in almost every country round the world, many mosques feature stunning, and almost majestic, architecture. the foremost beautiful mosques also are considered tourist attractions in their respective countries, and that they welcome visitors who not only want to marvel at the buildings, but are intrigued by the customs and culture…

View On WordPress

#Al Haram Mosque#Al-Masjid an-Nabawi#Beautiful Mosque#Brunei Darussalam#Crystal Mosque#Dome of the Rock#India#Israel#Malacca Straits Mosque#Malaysia#Saudi Arabia#Sheikh Zayed Mosque#Sultan Ahmed Mosque#Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin Mosque#Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Mosque#Taj-ul-Mosque#Turkey#United Arab Emirates

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Blue Mosque of Sultan Ahmed in ISTANBUL

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sultan Ahmed Mosque at night

#blue mosque#istanbul#travel#turkey#sultan ahmed#mosque#night view#night#walk#night scape#streetscape

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

khan al-umdan (caravanserai of the columns) in acre is one of palestine's best-preserved caravanserai, a type of inn historically common across asia, north africa, the caucuses, and southern europe, especially for travelers along trade routes like the silk road. it was built in 1785 on the order of ottoman governer ahmed pasha al-jazaar (who also has a mosque named for him nearby). the clock tower was added in 1906 to celebrate the silver jubilee of sultan abdul hamid II.

khan al-umdan served as more than just an inn - due to its proximity to acre's port, it also served as a spot for merchants to store and sell wares. it also gained importance to the baha'i faith, as it served as a site where baha'ulla (founder of the religion, he was imprisoned in acre later in life) received guests, and held a baha'i school. many palestinians found refuge inside the khan during the nakba, but were later forcibly expelled and evicted up to the 1980s.

it continues to be used for events today, but not as often as it used to be. despite being a popular tourist attraction and designated as a world heritage site, the caravanserai has also been facing further neglect due to gentrification and has also been in danger of being dispossesed for quite some time now.

#palestine#architecture#my posts#the word ''khan'' in arabic and hebrew has the same origin as ''caravanserai''#no relation to mongolic/turkic ''khan'' (king) (which has no relation to english ''king''/german ''kaiser''/etc)#also the world center for baha'i is in acre too.. they get a lot of shit across the me unfortunately especially iran where it originated#palestine also has a pretty substantial ahmadiyya population for a middle eastern country. the leader managed to convert quite a few#families in the 1920s while visiting#and ofc there's the druze which is a whole other thing

127 notes

·

View notes

Note

DAUGHTERS OF MEHMED III

This is also a very unknown, controversial and somehow interesting topic and I would like to put my stamp on this. Also, I have a few interesting digs and findings, so I'd love to hear your comments on my research as always...

_____________________________________________

The first Sultana I would discuss is Ayşe Sultan. It is not confirmed who her mother is, but the sure thing about her is that she was in marriage during early reign of her brother Ahmed I to vizier Destari Mustafa Pasha, who made some fountain in 1608 and died in 1610 (not 1614, it’s the year his little mosque was finished(!!!)). We know also that she had two sons and a daughter and that they died very young and were buried in their father’s tomb. I would at least suggest that Ayşe survived her husband when he died in 1610.

It is very interesting that Ayşe Sultan is claimed by Öztuna to be remarried in 1613 to Gazi Hüsrev Pasha. I think that this time, Öztuna may hitted by sudden the right info;

https://cdn2.islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/dosya/19/C19006276.pdf (page 46)

https://isamveri.org/pdfdrg/D00057/1969_23/1969_23_EYICES.pdf (page 192)

Both of there liks provide the fact that Ayşe Sultan was wife of Hüsrev Pasha.

I would ask you to pay attention on second link I’ve send to you. It is a great text, and is a study of Grand Vizier Gazi Hüsrev Pasha. On page 192, we understand that his wife was Ayşe Sultan (I’m not sure if text says that she survived him or died before him). More interesting, on the same page (note 43 below) author is obviously confused which Ayşe Sultan was his wife; he suspects of daughter of Murad III and Ahmed I, but we all know it is not true; Murad III’s daughter died in May 1605, and Ahmed I’s daughter was married to Hafiz Ahmed Pasha at the time and before that. I would suggest this Sultana may really be daughter of Mehmed III. As she was not listed among Sultanas in 1638 harem registers, it means she died latest in mid 1630s (if not before 1631).

We know for sure that one of Mehmed III’s daughters was named Şah Sultan. I saw you suggested that she could be wife of Kara Davud Pasha, but you were wrong in your assumption. No source clearly claimed that she was his wife. But, I’ve found something interesting. In 82 numarali muhimme defteri, under cesision 116, here is what Ahmed I wrote in 1616/1617:

Dürrî Efendi yazdurmışdur. Narda kâdîsına hüküm ki: Müteveffâ Vezîr Mustafâ Paşa'nun hâl-i hayâtında Narda hâsları bin on tokuz senesinde ebnâ-i sipâhiyândan kıdvetü'l-emâsil ve'l-akrân Muhammed zîde kadruhûnun tokuz yük akçaya uhdesinde iken mûmâ-ileyh vezîrüm fevtolup muhallefâtı zevcesi olan hemşîrem Şâh Sultân'a ve evlâdına intikâl idüp meblağ-ı mezbûr merkûm Muhammed'den taleb olundukda zikrolunan tokuz yük akçanun yedi yük iki bin dört yüz elli beş akçasın mûmâ-ileyh vezîrüme kemâl-i sıhhatinde teslîm olunduğına defterde mastûr u mukayyed bulunup ve sene-i mezbûre mahsûlâtından bâkî kalan iki yüz toksan yedi bin beş yüz kırk beş akçayı dahı mûmâ-ileyhâ sultâna teslîm idüp ve bin yiğirmi senesinün mûmâ-ileyh vezîrümün tahvîline düşen ispençesinden yüz elli bin akçayı dahı bî-kusûr mûmâ-ileyhâ sultâna teslîm itdüğine mûmâ-ileyhâ sultândan ve eytâmına vasî* olan Müteferrika Halîl zîde mecdühû tarafından me[m]hûr temessük virilmeğin, mûcebince amel olunup ol temessüğe muhâlif mezbûr Muhammed rencîde olunmamak bâbında fermân-ı âlî-şânum sâdır olmışdur. Buyurdum ki: Vusûl buldukda göresin; mûmâ-ileyh vezîrümün hâsları mahsûlinden fi'l-vâkı‘ zikrolunan mikdârı akça, mezbûr Muhammed tahvîlinden teslîm olunduğına mûmâ-ileyhâ sultân ile eytâmına vasî* olan mezbûr Halîl zîde mecdühû tarafından memhûr temessük virilmiş ise mûcebince amel idüp min-ba‘d ol temessüğe muhâlif mezbûrı rencîde vü remîde itdürmeyesin.

From this letter, we find out that Şah Sultan was in 1616/1617 widow of vizier Mustafa Pasha, who died in 1009 H. (1610) and that they had a son. I would remind you that we all know for sure that daughter of Mehmed III who was married to vizier Mustafa Pasha, died in 1610 and that this Sultana remarried in 1612 to Cığalazade Mahmud Bey, great-grandson of Mihrimah Sultan.

Now, in book Searching for Osman, T. Baki says that Sultana who was married to Mustafa Pasha and later Mahmud Bey was full-sister of Mustafa I beside wife of Kara Davud Pasha. I strongly suggest that this claim is a mishit by author or of a source he used to state this, because that Sultana was full-sister of Ahmed I and her husband Mahmud Bey was favourite brother-in-law of his. See why:

Viaggi di Pietro della Valle, il pellegrino, descritti da lui medesimo in lettere familiari all'erudito suo amico Mario Schipano divisi in tre parti cioè : la Turchia, la Persia e l'India (page 118)

Note: I found out this was originally reported in June 1615

‘’…Mahmud bascia, figliuolo chef u del gia Cicala, e cognate ora del Gran Signore , e henche giovane, uomo qui di molta estimazione e di maggiore speranza: si perchee di spirit per se stesso, come anche per lo favour della sultana sua moglie, che tra le sorelle del Gran Signore e forse la piu amata, e, se ben mi ricordo, credo che sia sorella a lui di padre e di madre, che in queste parti rade volte avviene ai principi del sangue reale.’’

La porta d'Oriente - lettere di Pietro della Valle : Istanbul 1614 (pp. 132-133)

‘’Di queste cose di Persia gli fece gran danno Mahmud Bascia, egli ancora vezir, detto qui per sopranome Cigaliogli, cioe figliuolo del Cicala, perche quel rinegato Cicala, gia capitano famoso nel mare, fu suo padre. Costui, richiamato dal governo che haveva non so se nella Babilonia o in altro paese de’ confine del Persiano, venuto in Constantinopoli, per disgusti che haveva havuto con Nasuh, ne disse molto male al Gran Signore, insieme con la sua moglie, che e sorella del Gran Signore e da lui molto amata. Hebbero amendue udienza poco prima della morte di Nasuh, et in particolare la moglie di Mahmud, una volta assai secretamente et a lungo. Fra le alter cose che di lui suggerirono al principe, dissero che Nasuh haveva fatto morire innocentemente in quelle parti un ufficiale, che era buonissimo ministro, solo per torgli la robba, dopo la morte del quale I turchi havevano perduto molto co’i persiani, e che in somma Nasuh se la intendeva con loro; e mostrarono alcune lettere di questa intelligenza, le quali Mahmud haveva intercettate, facendo morir secretamente e seppellir dentro al suo proprio padiglione colui che le portava, che a caso un giorno in campagna, verso quelle bande, haveva per camino incontrato e trattenuto seco alquanto a riposare.’’

Also, there was one of Mehmed III’s daughters named Hatice. Oztuna suggests she was wife of Mirahur Mustafa Pasha, but obviously not the one who was vizier and died in 1610. It is true that she had her own tomb in Şehzade Mosque Complex as one of her sisters Ayşe and her first husband Destari Pasha, but she was not married to Mustafa Pasha.

In 82 numarali muhimme defteri, in decision 56, Ahmed I points her out just as Hatice Sultan, in difference to his full-sister Şah Sultan, to whom he reffered in decision 116 as hemşîrem Şâh Sultân (my sister Şah Sultan; similar case with Murad IV’s sister Gevherhan and Ümmügülsüm). Just to remind you, this is not Murad III’s daughter Hatice, who was wife of beylerbeyi of Kefe Mehmed Pasha.

Mâliyye emri mûcebince. Vulçıtrın Beği olup bi'l-fi‘l Üsküb ve Kratova Nâzırı olan Mehmed dâme ızzühûya ve Đvranya kâdîsına hüküm ki: "Kazâ-i mezbûrda vâkı‘ Đvlasne (?) ve Kovanes (?) hâsları mukaddemâ Dergâh-ı Mu‘allâm Yeniçerileri Ağası olup vefât iden Mustafâ'nun zevcesi seyyidetü'l-muhadderât Hadîce Sultân dâmet ısmetühâya ber-vech-i paşmaklık hâs ta‘yîn olunup zabt üzre iken girü havâss-ı hümâyûnuma ilhâk olunup kendüye gadrolduğın" Rikâb-ı Hümâyûnum'a arz-ı hâl sunup girü; "Bin yiğirmi altı Zi'l-hıccesi'nün yiğirmi birinci güninden havâss-ı hümâyûnumdan ifrâz olunup müşârun-ileyhâya ibkâ’en mukarrer ola." diyü hatt-ı hümâyûn-ı sa‘âdet-makrûnum ile fermân-ı âlî-şânum sâdır olmağla Mâliyye tarafından dahı emir virilüp mûcebince Dîvân-ı Hümâyûnum'dan dahı hükm-i hümâyûnum recâ itmeğin buyurdum ki: Vusûl buldukda, Mâliyye tarafından virilen emir mûcebince amel idüp min-ba‘d hılâfına cevâz göstermeyesiz.

Anyway, we find out from this letter that her former husband was late (by then) jannisary Mustafa Aga. Also, I found out something more interesting; I found writings of vakfiye of twice Grand Vizier Kayserili Halil Pasha (d. 1629), where his wife was Hatice Sultan!

https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/203007 (PAGE 7)

Also there are sources where Halil Pasha is claimed to have two sons with Hatice, Mahmud Bey and Ebubekir Bey: https://en.marastaedebiyat.com/templates/yayinlar/marasli-kardesler.pdf (page 24)

Interesting is that Halil Pasha is rarely known as damad, and that he married one of the daughters of Mehmed III. (A Short History of the Ottoman Empire by Ayfocu (2022), Diplomatic Cultures at the Ottoman Court, C.1500–1630 (2021), Rarities of These LandsArt, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Dutch Republic (2021), etc…)

I will now suggest name of Kara Davud Pasha’s wife. It is confirmed that he and his wife had a son, and rumours were that they wanted to put him on throne. What is lesser known is that their son’s name was Suleiman, confirmed first by Evliya Celebi in his work Şeyahatname and by John Freely in Inside the Sergalio. By documents of judicial reports, Suleyman Bey had a juridical dispute with one of his aunts, Fahri Sultan, in 1662 about the lands. He is referred in those documents as Sultanzâde Süleyman Bey b. el-merhûm Davud Paşa. However, he died in 1687/88, and after his death, he left three daughters behind him, named Ayşe, Safiye and Afife.

Husûs-ı âti’l-beyânı mahallinde tahrîri için fermân-ı âlî sâdır olmağla imtisâlen-leh savb-ı şer‘-i şerîfden irsâl olunan Mevlânâ es-Seyyid Abdülmu‘ti Efendi Âsitâne-i Sa‘âdet’ime bi’l-fi‘il kāimmakām-ı vezâret-i uzmâ ve nâib-i menâb-ı vekâlet-i kübrâ olan vezîr-i rûşen-zamîr-i müşterî-tedbîr mümehhid-i bünyâni’d-devleti ve’l-ikbâl müşeyyid-i erkâni’s-sa‘âdeti ve’l-iclâl el-muhtassu bi-mezîdi inâyeti’l-meliki’l-a‘lâ devletlü ve sa‘âdetlü Ömer Paşa -dâme birruhû ve feşâ- hazretlerinin sarây-ı âlîlerine varıp zeyl-i kitâbda muharrerü’l-esâmî udûl-ı müslimîn ve sikāt-ı muvahhidîn huzûrunda akd-i meclis-i şer‘-i mübîn eyledikde medîne-i Hazret-i Ebî Eyyüb el-Ensârî’de sâkin iken bundan akdem vefât eden merhûm Davud Paşazâde Süleyman Bey’in sulbiye sagīre kızları Afife ve Âişe ve Safiye’nin kıbel-i şer‘den mansûb vasîleri olan el-Hâc Mahmud b. Receb meclis-i ma‘kūd-ı mezbûrede vezîr-i müşârun-ileyh hazretleri mahzarlarında bi’l-vesâye ikrâr ve takrîr-i kelâm edip bundan akdem yedimde olan işbu hüccet nâtık olduğu üzere sefer-i hümâyûn mühimmâtı için istidâne lâzım gelmekle taraf-ı mîrîden sagīrât-ı mezbûrât mâllarından ben hacc-ı şerîfde iken nâzırları İbrahim Çelebi b. Mahmud yedinden dört kîse akçe olmak üzere iki bin guruş istidâne ve kabz olunup ve çuka bahâsından dahi iki yüz guruş ki cem‘an iki bin iki yüz guruş deyn-i mîrî mukābelesinde taraf-ı şehriyârîden işbu kırmızı minâkârî her yâfte ortasında on dokuz taşlı elmâs ve etrâfı sagīr elmâslar ile murassa‘ iki yâfte elmâslı murassa‘ olup ol vakitde iki bin iki yüz elli guruş kıymet ile tahmîn olunup ve hâlâ bin iki yüz elli guruş ile tahmîn olunan işbu ön cevâhir kuşak nâzır-ı mezbûra rehn vaz‘ ve teslîm olunup ba‘dehû ben hacc-ı şerîfden geldikde nâzır-ı mezbûr kuşak-ı merkūmu bana def‘ ve teslîm ve meblağ-ı mezbûru ahz u kabza tarafından beni ihâle ve tevkîl etmişdi. El-hâletü hâzihî zikr olunan kuşak deyn-i mezkûr için değer kıymetiyle temlîk olunmak bâbında hatt-ı hümâyûn-ı şevket-makrûn vârid olmağla verese-i müşârun-ileyh hazretleri bâ-hatt-ı hümâyûn deyn-i mezkûre mukābelesinde mârru’z-zikr kuşağı bi’l-vekâle temlîk, ben dahi vesâyetim hasebiyle ber-vech-i muharrer temellük ve kabûl ve tesellüm eyledim dedikde gıbbe’t-tasdîki’l-mu‘teberi’l-vicâhî vâki‘-i hâli mevlânâ-yı mezkûr mahallinde tahrîr ve ma‘an ba‘s olunan Mehmed Çelebi b. İdris’le meclis-i şer‘a gelip her biri alâ vukū‘ihî inhâ ve takrîr etmeğin mâ-vaka‘a bi’t-taleb ketb olundu.

This all is true. Additionally, there is one document written by granddaughter of Kara Davud Pasha, Afife Hanim, who was trustee of one foundation; there writes Kara Davud Paşa Torunu, Vakıf Mütevellisi Afife Hanım İmzalı:

Or, if you can't enter the link, just google as "Devletlü Saadetlü Sultanım Efendi Hazretleri Sağolsun" Hitaplı Talepname'' and you will find her letter.

Now, Kara Davud Pasha’s son Suleyman had three daughters, but very interestingly, one of them named Safiye. It was very unnormal to me that he would give such a name to his daughter, considering with happenings from June 1603, when Valide Safiye Sultan was the main mediator in the murder of his uncle Shehzade Mahmud and exile of his grandmother Halime Sultan.

But, very interesting, from 1638 Harem records J. Dumas provided, we see that beside own sisters of Murad IV and one own sister of late Murad III, who received the highest payments as being full-sisters to a Padishah, also there were two daughters of Murad III, Beyhan Sultan and Fahri Sultan, who also were granted highest payments according to positions their husbands (respectively Nigdeli Mustafa Pasha and Çerkes Mehmed Pasha) took under reign of Murad III, it seems that half-sisters of (late and current) sultan(s) received lesser stipend, as Ahmed I’s daughter Atike Sultan and Murad III’s daughter Hatice Sultan. But, there was also one Sultana, Safiye Sultan who received greater amount than Atike and Hatice, but lesser amount that abovementioned ones. We just see that she was wife of some Mehmed Pasha. I have some very strange feeling that this very easily could be former wife of Kara Davud Pasha. Ofc, there are sources lacking to additionally confirm this assumption, but it seems that her son named one of his daughters after her. Nevertheless, she lesser amount (350 aspers) was due to her actions in 1622 probably, she was obviously forgiven, but not forgotten about her doings in those horrible times. To name her son a sultan, she had to kill all remaining sons of Ahmed I, so she was possibly remarried to this Mehmed Pasha after second fall of Mustafa I and lived a quiet life. I hope I will found somehow source which would reaffirm my claims, but for now, it seems to me this might be right…

The greatest mystery for me is this Sultana, who is reported in 1600 to be the eldest child of Mehmed III. By citations that you’ve provided to me, it seems that this Sultana was daughter of Handan Sultan; as she was given to Mehmed in 1582 on his circumcision by his aunt Gevherhan Sultan, she could very easily bore her in following 1583. To remind you, before festivities in June 1582, earlier that year or previous one Mehmed impregnated one of Nurbanu Sultan’s slaves, whom she ordered to be thrown into cold Bosphorus. So, he was capable of bedding a woman, as he could had his own harem. Ofc, as the girl was born (and not a boy), it was not celebrated on high level, and we have no infos about that in regular sources. But, I will add some things

In report from 1600 (Girolamo Cappello), on page 414 he reports that governor of Cairo Iskender Pasha (Kender bassa) is fourth vizier and that he tries by all means to have king’s daughter as wife, but the ambassador considers it unlikely because Pasha was being in age disproportionate to king’s daughter. On the other side, on page 415, he reports that Mahmud Pasha, who was general and fighting against enemy in Micali, was said to be given king’s daughter by king himself if he would be succesfull in fights.

In source Relazioni degli stati Europei lette al senato dagli ambasciatori Veneti nel secolo XVII on page 37 is stated: Ha tre figliuoli maschi e una femmina: questa di eta di 18 anni: ed ha discorso di alcuni bascia che la pretendono per moglie, come Mahmud, e il bascia del Cairo, ma non si maritera se prima non si fa il ritaglio del primogenito, ne questo si fara se non si termina la querra di Ungheria…tutti questi sono di una madre, e l’ultimo che ha 3 o 4 anni ha nome Osmano./ He has three sons and a daughter: the latter is 18 years old: and he has spoken of some pashas who want her as a wife, like Mahmud, and the bascia of Cairo, but she will not marry unless the firstborn is cut off, nor will this be done unless the war in Hungary is ended…all them are from the same mother, and the last is 3 or 4 year old by name Osman.

It seems that before December of 1602, during reign of her father, this Sultana was eventually married off. In Safiye’s Household on page 29 (note 64) says:

14 Dec. 1602 – the baylo says that once paşas in disgrace were killed or sent away from Constatinople; now two former paşas, one the husband of the sultan’s sister and the other of the sultan’s daughter, create disorders but their wives freely enter the Imperial Palace

Reported in Osmanlı İmparatorluğu tarihi (1965) by Zuhuri Danışman (page 243) that beside Sultan Ahmed’s daughter Gevherhan who marries Mehmed Pasha, he has two sisters who were before married to Mustafa Pasha and Kanije defender Tiryaki Hasan Pasha (also said by Hammer). G. Borekci said that Handan Sultan was reported in February 1595 to have three sons and two daughters. Obviously, these were own sisters of Ahmed I. It seems that the eldest Sultana married secondly in 1604 to Hasan Pasha. In Oztuna’s work Devletler ve hanedanlar, she is reported by him to had a son and two daughters.

Also, one of Ahmed I’s sisters married in early 1610s governor of Buda Kadizâde Ali Pasha, also known as Ali Pasha of Buda. Ali Pasha died in December 1616 in Belgrade. Sakaolgy in his book reported that Ambassador Valier says that Ali Pasha’s his wife was Sultan Ahmed’s younger sister. If so, she was not his full-sister. Anyway, I would like personally to see that report about Ali Pasha, I wasn’t able to find it.

It seems that Mehmed III also had a daughter named Halime, who was a widow during 1622; she was surely Halime’s daughter. It seems it was popular back then to name daughter after their mother (case with Murad II’s daughter Hundi, Bayezid II’s daughter Ayşe, Selim I’s daughter Hafsa, Mehmed III’s daughter Halime, Ahmed I’s daughter Kösem, Murad IV’s daughter Ayşe and Mehmed IV’s daughter Emetullah).

I would suggest Halime was born in 1598; you shared with us once report from Leonardo Dona dated from August 1597: Et si dice che fin hora habbia conggresso con otto altre donne, tre o quattro delle quali siano già gravide// And it is said that until now he has had congress with other eight women [other than Handan], three or four of them being already pregnant

It was maybe Halime one of those four who got pregnant and bore a daughter in 1598, as she gave birth to Mustafa in 1600/01.

One source (https://nek.istanbul.edu.tr:4444/ekos/TEZ/49544.pdf) (page 54, note 337) claims that Sultan Mehmed III had one daughter named Hüma(şah) Sultan. Author namely cites Selaniki as source, but he says nothing about her. ________________________________________

Anyway, as by now, I would sum up Mehmed III’s daughters like this:

Fülane Sultan (1583 — after 1604); daughter of Handan. Married firstly in late reign of her father to some of the pashas. Married secondly in 1604 to Tiryaki Hasan Pasha, with whom she had three children.

Ayşe Sultan (1588? — after 1614); daughter of Halime. Married firstly in 1604 to Destari Mustafa Pasha, with who she had three children. She might remarried to Gazi Khusrev Pasha.

Şah Sultan (1589? — 1618?); daughter of Handan. Said to be full and favourite sister of her brother Ahmed I. Married firstly in 1605 to Mustafa Pasha, with whom she had a son. After his death, she remarried Mahmud Bey in 1612. She was still alive in 1617, but as her husband remarried in May 1620, she most likely died in 1618/19.

Hatice Sultan (?? — ??); daughter of Halime or another concubine. Married firstly to Mustafa Agha, remarried to Kayserili Halil Pasha, with whom she had two sons.

Safiye Sultan (1590? — after 1638); married in 1606 to Kara Davud Pasha with whom she had a son Suleiman. After her husband was executed, she remarried to some Mehmed Pasha.

Halime Sultan (1598 — after 1622); daughter with Halime

Hümaşah Sultan; might name of eldest daughter

Fülane Sultan (after 1590 — after 1616); younger half-sister of Ahmed I, married to Ali Pasha of Buda.

Oh, I really like this topic. Mehmed III’s daughters fascinate me a lot.

Sorry for the wait, it took me a really long time to gather all the sources.

This is going to be so long it could kill the reader, I’m so sorry 😭

I don’t understand how you came up with the date of Ayşe’s marriage to Destari Mustafa Pasha. As far as I know, we don’t have it. Also, I have found (in Öztuna, Devletler ve Hanedanlar) that Destari Mustafa Pasha was governor of Anatolia for a year, only in 1603, so I wonder what happened: was he governor of Anatolia when he was given the hand of a princess or was he appointed governor because he was the husband of a princess? In 1604 the governorship was given to Kejdehân 'Alî Paşa.

Anyway, Destari Mustafa Pasha died in 1610 and was buried in his tomb in the Şehzade Mosque.

There is no source that says that Ayşe was married during Ahmed I’s reign, so she could be the princess described by Agostino Nani in 1600:

Ha tre figliuoli maschi e una femmina: questa di età di 18 anni: ed ha discorso con alcuni bascià che la pretendono per moglie, come Mahmud, e il bascià del Cairo, ma non si mariterà se prima non si fa il ritaglio del primogenito, né questo si farà se non si termina la guerra di Ungheria, e si resti liberi dai travagli dei sollevati in Asia.

To be honest, basically every princess who wasn’t Halime’s daughter could have been the one described by Agostino Nani.

Pietro della Valle wasn’t completely sure that Şah was Ahmed I’s own sister but it’s interesting that he mentioned that because foreigners usually didn’t. About the second quote you posted, the one about Nasuh’s execution: well, it seems this was a family affair because Pietro della Valle says that Şah and her husband spoke with Ahmed I before the Grand Vizier’s execution and told him about some misdeeds he had done. On the other hand, Ragusian diplomats said that Gevherhan Sultan binti Selim II was the reason behind Nasuh Pasha’s execution:

“Dicesi che la causa della morte di Nasupassa è stata sultana di Gevatmehmet la quale essendo li messi passati andata verso Mecha scrisse di la al Gran Signore piu cose contro detto Nasupassa, e particolarmente li disse, che non era suo Visiero, ma Capiciehaia del Persiano”

Both princesses said that it looked like Nasuh Pasha had ties with the Persians.

I have to disagree with you on the fact that Hatice Sultan can’t be Ahmed I’s sister based on that decision. While it’s true that I said the same about Ümmügülsüm binti Ahmed I and Murad IV, in the same 82 numarali muhimme defteri, Osman II calls Ayşe “hemşîrem” in decision 273. In 85 numarali muhimme defteri, Murad IV refers to Gevherhan as “hemşîrem” in decision 93 and 563.

I’m not entirely sure that Hatice went on to marry Kayserili Halil Pasha because in the first source you sent his wife is mentioned as “Hatice Sultan” only by the author. The original document says “Hadice Hanım” (p. 7, n. 14), which made me a little suspicious. In the second source you sent, his wife is mentioned as “Hatun” and never as a princess; the author says:

The name of Halil Pasha's wife is Hatice Hatun. Other relatives include Fatma Hatun, Emine Hatun, Melek Sima Hatun, Can Fida Hatun and Sakine Hatun, but there is no information about their degree of closeness.

It kind of makes me think that the author of the first source made a typing mistake when he referred to Halil Pasha’s wife as “Hatice Sultan”, because he doesn’t say anything else about it in the entire essay.

It is true, though, that Hatice Sultan was married to one Mustafa who had been the Janissaries commander. It’s also true that had this Mustafa been Mirahur Mustafa Pasha, he would have been referred to as a pasha and not as a janissaries commander. The decision is dated Zilhicce 1026, which went from November 30, 1617 to December 30, 1617, which means this man could have been the Mustafa Ağa who died in Baghdad in 1616 (Öztuna). The next Mustafa is “Hoca-zâde dâmâdı Mustafa Ağa” but he was commander from 1617 to 1618 (also, he was married to a woman from the Hocazade family, clearly).

About Safiye Sultan. Let’s go back to Dumas’ harem registry, which you mentioned:

The princesses are in order of amount of money except for Safiye Hanımsultan who most likely took her mother’s place in the harem register as a recipient. I don’t know why the princesses who receive 12900 per month are in that particular order but that’s not the point right now.

Now, to find out the identities of most of these princesses we cross-referenced them with other sources, especially the princesses mentioned by Ragusian diplomats in 1642 and 1648:

(can you tell I love tables?)

From this list I left “Safiyye Sultan merhum Mehmed Paşa” out because we don’t know who she is, also because Mehmed Pasha as a husband is truly too vague.

Now, let’s get to the decision in the Istanbul Court Registry you sent me. So, one of the issues I have with it is that Davud Pasha’s son is called “Davud Paşazâde Süleyman Bey”, which opens the possibility that he could have been Davud Pasha’s son from another marriage. If he had been called Sultanaze then we would have been safe.

I’m going to be honest with you: I couldn’t find where you said that Evliya Celebi confirmed that Davud Pasha’s son with the princess was called Süleyman. The only mention to Davud Pasha I found was this:

Hayat hikâyesi : Mere Hüseyin Paşa, Arnavut ırkından olup, evvelâ Satırcı Mehmed Paşa’nm aşçıbaşısı, sonra sırasıyle sipahi çavuşu, koyun emini, çavuşbaşı, kapıcıbaşı, kapıcılar kethüdası, büyük mirahur ve en sonra Mısır valisi, daha sonra da hain Davud Paşa’nın yerine Sadrâzam oldu.

which is just Evliya saying that Hüseyin Pasha succeeded Davud as Grand Vizier.

But whatever, let’s move on. This Süleyman Bey had three daughters: Afife, Ayşe, and Safiye.

Your theory is that Safiye was also the name of his mother, considering that Mehmed III was very close to his mother and that there is a Safiye Sultan listed in a harem register in 1638-39. Now, this is kind of a risk because a) it cannot be confirmed in any way and b) we have to suppose that Davud Pasha’s wife married a Mehmed Pasha after his execution. I mean, it could be but it’s just a conjecture at the moment. For example, Afife could have been named after her grandmother and she could have died before 1639, when the harem register was compiled.

As I said above, any daughter of Handan could be the one described by the ambassadors.

It is true, though, that Francesco Contarini says this (unfortunately we don’t have his relazione)

14 Dec. 1602 – the baylo says that once paşas in disgrace were killed or sent away from Constatinople; now two former paşas, one the husband of the sultan’s sister and the other of the sultan’s daughter, create disorders but their wives freely enter the Imperial Palace

therefore prompting that, in the end, Mehmed III married off at least one of his daughters towards the end of his reign. It is interesting that at this point Şehzade Mahmud was still alive so marrying a princess off could have changed the balance in the harem since both Halime and Handan had daughters.

Let’s move onto Tiryaki Hasan Pasha. You mentioned Hammer, and I was able to find out the where he talked about him:

A Constantinople, Mahmoud, fils de Cicala, obtint en mariage une sœur du Sultan défunt, Mohammed III; le kapitan-pascha, Mohammed le' Boeuf, épousa la sœur aînée du Sultan régnant, et le grand-vizir, Nassouh, fut fiancé, en présence de tous les vizirs et du moufti, à la sœur cadette du souverain ( février 1611- silhidjé 1020 ). Deux des sœurs d'Ahmed avaient été mariées antérieurement à Moustafa-Pascha et à Hasan Teryaki, le brave défenseur de Kanischa, et sa fille, Ghewherkhan, avait été fiancée au gouverneur d'Egypte, Mohammed Koulkiran. Le 13 juin 1612, noces du kapitan-pascha et de la sœur aînée d'Ahmed furent célébrées avec une pompe inouïe.

Now, this excerpt is interesting because there’s so much confusion lmao:

Cigalazade Mahmud (Bey?) “had married a sister of the deceased sultan, Mehmed III”: now, Cigalazade Mahmud Bey married a daughter of Mehmed III. On the other hand, Cigalazade Mehmed Bey married a daughter of Murad III. Who is he referring to? Who knows.

Öküz Mehmed Pasha “had married the eldest sister of the reigning sultan”: Kara “Öküz” Mehmed Pasha, though, was Gevherhan binti Ahmed I’s first husband.

“Nasuh, the Grand Vizier, was betrothed, in the presence of all the viziers and the mufti, to the younger sister of the sovereign (February 1611)”: Nasuh Pasha, though, married Ayşe binti Ahmed I. Maybe Nasuh Pasha was supposed to marry one of Ahmed I’s sisters but she died? According to Tezcan, the marriage took place in December 1612; if Hammer is right then maybe he was first betrothed to another princess.

“Two of Ahmed's sisters had been previously married to Mustafa Pasha and Hasan Teryaki, the brave defender of Kanischa”: Mustafa Pasha could be Destari Mustafa Pasha.

I don’t understand where you found that in Devletler ve hanedanlar a princess had three children with Hasan Pasha.

I don’t see anyone married to Hasan Pasha.

We can’t say that these princesses were Ahmed’s own sisters because Hammer mentioned at least 4.

About the princess who married Ali Pasha. I checked what Sakaoglu said and he referred to Alderson so I checked him too. So, Alderson’s source says this:

On dit aussi que ce fut en cette année que Cigale, duquel il a esté fait souvent mention, fut fait General de la mer, au lieu d'Haly Bassa beau-frere du grand Seigneur. (Chalcondyle, Histoire des Turcs, p. 851)

So, the Grand Seigneur mentioned here is Mehmed III, not Ahmed I, so Ali Pasha was married to a daughter of Murad III, not of Mehmed III. This being Alderson’s source for saying that a daughter of Mehmed III was married to Ali Pasha confuses me a lot because “beau-frère” means — clearly — brother-in-law.

His other source is Hammer:

Les Turcs ne pouvaient songer sérieusement à la paix avant que Bocskai eût conclu la sienne avec l'Autriche; lorsqu'un traité entre Bocskai et l'empereur eut été signé à Vienne, le Sultan donna à son gendre Ali-Pascha, gouverneur d'Ofen, au vizir Mourad-Pascha et à Habil-Efendi, juge d'Ofen, des pleins pouvoirs pour agir en son nom.

According to Uzunçarşılı, though, the governor of Buda Ali Pasha was the son-in-law of Kuyucu Murad Pasha, not of the sultan:

Ali Pasha, the governor of Budin, the son-in-law of the vizier Murad Pasha, and Habil Efendi, the qadi of Budin, and Kadim Ahmed Efendi, the kethuda of Murad Pasha, and Nasrüddin zade Mustafa Efendi, one of the notables of Budin, became the executive director of peace.

İşbilir too says that Kadızâde Ali Pasha was the son-in-law of Kuyucu Murad Pasha:

the Treaty of Zitvatorok was signed as a result of the negotiations conducted between 17 Cemaziyelâhir - 10 Rajab 1015 (20 October - 11 November 1606) by his son-in-law Kadızâde Ali Pasha and the judge of Budapest Hâbil Efendi.

I’m sorry but I could not find Sakaoglu’s mention of Cristoforo Valier; he mentioned the secretary to the Austrian ambassador, Werner, instead:

Her name, birth and death dates are unknown. It could be determined that she married Ali Pasha, who died in 1617. In his footnote regarding this princess of Mehmed III’s and Ali Pasha, Alderson mentions Chalcocondyles; Hammer reports that he was married to a daughter of Ahmed I. Austrian ambassador Werner, while describing his meetings with Ali Pasha in Budin, which he stopped by on his way to Istanbul in 1616, said, "He is a liberal and close to Christians, he is about 50 years old. He is married to the sister of the Turkish ruler." It appears that she was the sister of Ahmed I.

Werner, that is Adam Werner von Crailsheim, was not the Austrian Ambassador but the secretary to the Austrian ambassador, Hermann Czernin von Chudenitz. Unfortunately I could not read his diary but it’s been published in Turkish as “Padişahın Huzurunda”.

In conclusion I would be very cautious in saying that Kadızâde Ali Pasha was a damad because I don’t think he was.

I personally don’t agree that if a princess is younger than Ahmed then she’s not his own sister because Mehmed III had discarded harem rules: both Handan and Halime kept having children after the births of their sons so it can be entirely possible that Ahmed I had a younger full sister.

I don’t know how popular it was to name daughters after their mothers because Ayşe, Hafsa, and Emetullah are Muslim names. Kösem and Halime are certainly unusual names (but I’m not sure a princess called Kösem really existed).

Honestly, this princess could have been born basically anytime. Also, I made a typo in that ask because I don’t think Leonardo Donà was in Istanbul in 1597. His last dispatch from Istanbul is dated 14 December 1595. Moreover, Lorenzo Bernardo in 1587 (though his relazione is dated 1590 for some reason) stated that Mehmed (then prince) had two sons “and many daughters”:

Ha finalmente due figlioli maschi, sultan Selim e sultan [***] e molte femine, di molte schiave, che tiene al suo servizio.

Of course some of these princesses could have died before Ahmed I’s accession.

I’m sorry I can’t open your last source, the link doesn’t work for me.

Anyway, what I wanted to highlight is that I don't think we can put Mehmed III's daughters in order because we have no idea who the eldest Venetian ambassadors kept talking about is.

#kehribar-sultan#ask: ottoman history#unnamed daughters of mehmed iii#ayse sultan daughter of mehmed iii#sah sultan daughter of mehmed iii#hatice sultan daughter of mehmed iii

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illuminated minarets on the Blue Mosque, aka Sultan Ahmed Mosque.

#original photography#photographer on tumblr#pws photos worth seeing#travel#night photography#night shots#mosque#blue mosque#istanbul#turkey#architechture#exterior#building#illumination

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 17th century Sultan Ahmed Mosque or Blue Mosque is one of the top sights of Istanbul, Turkey.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mosques: Architectural Marvels

From the ornate domes that pierce the skyline to the intricate geometric patterns adorning their walls, Islamic mosques stand as architectural masterpieces that transcend time. These sacred spaces reflect not just religious devotion but also artistic excellence and cultural richness.

The Grandeur of Islamic Mosques

Islamic architecture is a canvas of creativity, where beauty intertwines with spiritual significance. The towering minarets and graceful arches symbolize a connection between the earthly and the divine, inviting worshippers into a realm of tranquility and reflection.

The Quran beautifully mentions the importance and the purity of mosques: “The mosques of Allah shall be maintained only by those who believe in Allah and the Last Day; perform prayers, and give zakat” (Quran 9:18). The beauty and grandeur of these mosques echo the reverence Muslims hold for their faith and the Creator.

Notable Mosques Around the World

Spanning continents, Islamic mosques vary in style and design, each telling its own story. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul, known as the Blue Mosque, mesmerizes with its cascading domes and intricate blue tiles. The Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi astounds with its pure white marble and opulent chandeliers, a testament to modern Islamic architecture’s magnificence.

“Whoever builds a mosque for Allah, then Allah will build for him a house like it in Paradise” (Sahih Bukhari 439, Sahih Muslim 533).

Islamic mosques not only serve as places of worship but also as community hubs fostering unity, learning, and charity. Their beauty transcends religious boundaries, inviting admiration and awe from people of diverse backgrounds.

Islamic Influence on European Architecture

Islamic mosque architecture indeed played a pivotal role in influencing the evolution of European architectural styles, particularly during the Medieval period. The contact between the Islamic world and Europe, especially during the Crusades and through trade routes, allowed for the exchange of ideas, knowledge, and artistry.

The magnificence of Islamic mosques, with their intricate geometric designs, ornate calligraphy, and towering minarets, captivated the imagination of European travelers and scholars. During the Middle Ages, as Europeans encountered these architectural wonders in regions like Spain, Sicily, and the Middle East, they were deeply influenced by the sophistication and beauty embedded in Islamic architecture.

Transition to European Architecture

The impact of Islamic architecture on Europe can be seen in the emergence of what is now known as “Romantic Architecture.” The pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and soaring spires characteristic of Gothic architecture find their roots in the designs observed in Islamic mosques.

For instance, the Great Mosque of Cordoba in Spain, initially a mosque, was later transformed into a cathedral. Its horseshoe arches and intricate mosaics influenced the construction of cathedrals like the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, showcasing a fusion of Islamic architectural elements with Christian symbolism.

Moreover, Islamic architectural techniques, such as the use of horseshoe and pointed arches, were integrated into European structures, enhancing their stability and height. This incorporation of Islamic architectural principles laid the groundwork for the evolution of European styles, transitioning from the Romanesque to the Gothic period.

Legacy and Cultural Exchange

The cross-cultural exchange between the Islamic world and Europe not only impacted architectural styles but also cultivated an environment of intellectual exchange. Muslim scholars preserved and expanded upon the knowledge of ancient civilizations, which eventually made its way to Europe through translations of works from Arabic to Latin.

This exchange of ideas, facilitated in part by the awe-inspiring beauty of Islamic architecture, contributed to the Renaissance and the flourishing of arts, sciences, and architecture in Europe.

In essence, the influence of Islamic mosque architecture on European styles was profound, serving as a catalyst for the emergence of new architectural forms, techniques, and aesthetic sensibilities that continue to resonate in the stunning structures dotting European landscapes.

In conclusion, Islamic mosques are not just architectural marvels but embodiments of spiritual devotion, cultural richness, and artistic brilliance. Their beauty encapsulates the essence of Islam, drawing both Muslims and non-Muslims into a world where faith meets artistry in a breathtaking symphony.

Learn more about Islam on our website: howtomuslim.org

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beautiful details in Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque by Ahmed Ali

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (5/18/24) Ottoman Empire (Turkish, 15th-20th c.) Interior: Sultan Ahmed Mosque ("Blue Mosque")(1609-16) Istanbul, Turkey

The upper levels of the interior of this mosque are dominated by blue paint. More than 200 stained glass windows with intricate designs admit natural light, today assisted by chandeliers. On the chandeliers, ostrich eggs are found that were meant to avoid cobwebs inside the mosque by repelling spiders. The decorations include verses from the Qur'an, many of them made by Seyyid Kasim Gubari, regarded as the greatest calligrapher of his time. The many spacious windows confer a spacious impression. The casements at floor level are decorated with opus sectile. Each exedra has five windows, some of which are blind. Each semi-dome has 14 windows and the central dome 28 (four of which are blind).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLUE MOSQUE - ISTANBUL

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 26 October, the Palestinian Ministry of Health released the list of names of Palestinians killed since 7 October. Among them, from the Shaheen family, are:

Walid Omar Ahmed (73);

Walid's son Murad Walid Omar (35) and his children Roua Murad Walid (7) and Shahin Murad Walid (6);

Gamal Youssef Abdellatif (70);

Abdullah Shaheen Ahmed (68);

Abdullah's son Muhammad Abdullah Shaheen (48) and his children Abdul Rahman Muhammad Abdullah (24), Farah Muhammad Abdullah (21), Anas Muhammad Abdullah (19), Ahmad Muhammad Abdullah (16), and Mahmud Muhammad Abdullah (9);

Na’ima Ahmed Abdelrahman (65);

Ibrahim Nimr Muhammad (65);

Sami Youssef Ismail (53) and his children Youssef Sami Youssef (33), Mustafa Sami Youssef (30), Isma'il Sami Youssef (28), Hadil Sami Youssef (23), and Lama Sami Youssef (17);

Mahmud Ayesh Mahmud (52) and his children Inshirah Mahmud Ayesh (29), Nesma Mahmud Ayesh (15), and Ali Mahmud Ayesh (9);

Wafa Saeed Mahmud (52);

Mahmud Abdelhalim Muhammad (51), pictured above, and his sibling Mostaganem Abdelhalim Muhammad (47), named for the Algerian city and province;

Bushra Abdelfattah Jaber (44);

Hiba Hindi Hegazy (41);

Haytham Muhammad Ali (31);

Abdul Rahman Salman Juma (29);

Rahima Saadi Muhammad (26) and her unnamed infant son;

Warda Ibrahim Ayesh (25) and her siblings Yasmin Ibrahim Ayesh (24) and Azhar Ibrahim Ayesh (22);

Yahya Sultan Zayed (11), "the only child of his parents. He had memorized the Quran and stood out among his peers, ranking first among them. He had a dream of becoming an astronaut;"

Tariq Mahmud Abdullah (11) and his brother Abdullah Mahmud Abdullah (10);

Muhammad Bara’a Tayseer (10);

Rahaf Rami Sadiq (7);

Aisha Jihad Jalal (less than a year old);

Thaer Abdullah (36), who was martyred when iof forces stormed Far'a camp north of Nablus;

Samiya Muhammad Omar (63) and her brother Bassam Muhammad Omar (59);

Ahmed Adib Muhammad (23) and his sister Mai Adib Muhammad (37);

Fawzia Yusuf Muhammad (26);

Ibrahim Osama Muhammad (13) and his siblings Anwar Osama Muhammad (28) and Samar Osama Muhammad (22);

Fatin Awad Abdel Rahman (35);

Yahya Bahaa Muhammad (21);

Latifa Ahmed Hamed (82);

Adib Muhammad Adib (9);

Yusuf Muhammad Yusuf (33), who was martyred after leaving a mosque in Budrus, west of Ramallah;

Iman Nabil Deeb (27);

Sahar Musa Ahmed (56);

Hassan Nasser Ahmed (17);

Ahmed Khalil Ahmed (15) and his siblings Mahmud Khalil Ahmed (10), Muhammad Khalil Ahmed (14), Iman Khalil Ahmed (2), and Ziad Khalil Ahmed (9);

Layan Bakr Ismail (9);

and Iman Ziad Hussein (36).

You can read more about the human lives lost in Palestine on the Martyrs of Gaza Twitter account and on my blog.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝗗𝘆𝗻𝗮𝘀𝘁𝗶𝗲𝘀 𝘄𝗶𝘁𝗵 𝗺𝗮𝗺𝗹𝘂𝗸 𝗼𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗶𝗻𝘀:

- 𝗧𝘂𝗹𝘂𝗻𝗶𝗱𝘀 (𝟴𝟲𝟴–𝟵𝟬𝟱 𝗖𝗘):

The Tulunid dynasty (al-ṭūlūnīūn) was founded and named after the Abbasid Turkic general and governor of Egypt - Ahmad ibn Tulun - in the year 868 CE, who formed the first ever independent state in Egypt (as well as parts of Syria) since the Ptolemaic dynasty (around 898 years prior).

Ahmad’s father Tulun was said to be a Turk from the region known to the Arabs as Tagharghar or in Turkic, Toghuz-oghuz or Toghuzghuz; this region by medieval Arab historians is attributed to the 𝐔𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐮𝐫 𝐅𝐞𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐫 𝐔𝐲𝐠𝐡𝐮𝐫 𝐊𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐞/𝐔𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐮𝐫 𝐊𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐞.

The Tulunids were the first state/dynasty of Turkic mamluk origins and reigned from 868 to 905 CE with nominal autonomy, until the Abbasid Caliphate brought their domains back into Abbasid control.

Pictured below is the Ahmad ibn Tulun Mosque constructed between the years 876-879 CE. The mosque was meant to serve as the main congregational mosque in the new Tulunid capital of Al Qata’i, and is the oldest mosque/masjid in Egypt and one of the oldest in all of Africa.

Its architectural style is that of Samarra (Iraq/Mesopotamia) and very closely resembles the Great Mosque of Samarra constructed by the Abbasids between the years 847-861 CE.

(Share!)

#islam#muslim#history#islamic history#history blog#mamluk#mamluks#abbasids#abbasid caliphate#ahmad ibn tulun#ahmad ibn tulun mosque#mosque#masjid

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, what information do we have about Haci Mustafa Aga? I know that he supported Mustafa I but i mean more about his background, birthdate even deathdate? I know that he managed the harem after Handan's death. Was he closer to Handan's age or Safiye's?

So, Hacı Mustafa Ağa underwent the Holy Pilgrimage in 1602 (thus acquiring the “Hacı” nickname) and lived in Cairo, Egypt, until late 1604, when he was recalled to Topkapi Palace. There he was first musahib (companion) to Ahmed I and then Chief Harem Eunuch in the autumn of 1605, after the dismissal of Cevher Ağa.

Mustafa Ağa participated in the construction of the Blue Mosque and is even mentioned in an inscription:

Mustafa is mentioned in an inscription on the mosque’s exterior façade, on the side facing Topkapı, as the superintendent (nazir) of the mosque’s construction. This marks the only time in Ottoman history that a Chief Harem Eunuch was included in the inscription of a sultanic mosque. (J. Hathaway, The Chief Eunuch of the Ottoman Harem. From African Slave to Power-Broker, 28%)

and when he had lived in Cairo, he had done a lot for the development of the city:

A lengthy Arabic endowment deed housed in Egypt’s Ministry of Pious Endowments lists a vast number of his residential and commercial properties in Cairo, as well as lands and commercial operations in a number of Egyptian subprovinces.67 Properties in Cairo are concentrated in the district of Saliba, just north of Dawudiyya; this is also the site of the eunuch’s house, which he cannily endowed to his Cairene vakıf. There is also a commercial complex near the Muski, located north of the Fatimid gate Bab Zuwayla, close by the great mosque/madrasa of al-Azhar and the Khan al-Khalili bazaar. This pattern strongly suggests that Mustafa Agha sought to extend the urban development projects that Davud and Osman had initiated a number of years earlier. His projects must have had a profound effect on this central zone of Cairo, restoring residential and commercial infrastructure from the late Mamluk era while adding new infrastructure where little had existed before. (J. Hathaway, The Chief Eunuch of the Ottoman Harem. From African Slave to Power-Broker, 57%)

After the death of Ahmed I, he helped putting Mustafa on the throne even though he knew about his mental difficulties.

Although el-Hajj Mustafa Agha was already close to Osman – indeed, he had announced his birth in November 1604 – he helped to engineer Sultan Mustafa’s peaceful accession, even though he was aware that Mustafa was of questionable mental ability or stability. (J. Hathaway, The Chief Eunuch of the Ottoman Harem. From African Slave to Power-Broker, 29%)

Soon afterwards, though, he started to work to have Mustafa I’s mental instability known to the subjects, with the goal of enthroning Osman in his stead. Three months later, Hacı Mustafa Ağa’s faction engineered the deposition of Mustafa I in favour of Osman. The new Grand Vizier, though, sent him to Egypt in exile for being too close to the new sultan:

According to Naima, Güzelce Ali wormed his way into the young sultan’s affections with lavish gifts, growing so close to him and, consequently, so powerful that he displaced Mustafa Agha, who had been so instrumental in Osman’s accession. Ultimately Güzelce Ali “betrayed” the Chief Eunuch, auctioned off his property, and sent him to Cairo. This was, from all appearances, part of a broader campaign against the Chief Eunuch’s coterie, for Güzelce Ali did much the same to at least one of Mustafa Agha’s clients around the same time. (J. Hathaway, The Chief Eunuch of the Ottoman Harem. From African Slave to Power-Broker, 29%)

Thus he was succeeded as Chief Harem Eunuch by Süleyman Ağa, one of his protégés (ironically).

Among his protégés also figured the future Grand Admiral Çatalcalı Hasan Pasha. As Kapıcıbaşı, chief of the palace doors, he informed Kösem that Osman was planning to have Mehmed executed:

… et dirò anco di maggior auttorità e fede col Gran Signore, nato da un estraordinario favor verso di lui della sultana madre che, memore dei suoi segnalati servigii in tempo che sospetta a sultan Osman macchinava a leverla la vita a Mehemet, et gli fu perservata per opera de detto Assam che, all’hora chiecaià del vecchio chislar, impiegò di suo ordine grossissima somma d’oro a tal effetto, come ho accennato di sopra. (M. P. Pedani, Relazioni di ambasciatori veneti al senato. Volume XIV, Costantinopoli. Relazioni inedite (1512-1789), p. 593.

Another famous protégé of his was the future Grand Vizier (and husband of Kaya Sultan) Melek Ahmed Pasha, who obtained a spot in the pages palace school thanks to the Chief Harem Eunuch.

After the second deposition of Mustafa I and the enthronement of Murad IV, Kösem recalled Hacı Mustafa Ağa from Cairo to have him again as Chief Harem Eunuch. He stayed in office until his death in mid-july 1624. Afterwards, he was buried “next to the tomb of the Prophet Muhammad’s standard-bearer Abu Ayyub al-Ansari (Ebu Eyyub el-Ensari)” in what will become the Eyüp Cemetery in Istanbul.

Perhaps during his second tenure as Chief Harem Eunuch, Mustafa Ağa had a hand in the succession to the throne of Crimea. In 1623, Mehmed III Giray went to Istanbul to denounce that Mustafa Ağa had helped his brother Janibek become the Khan of Crimea. Thanks to the then-Grand Vizier, who was Mustafa Ağa’s enemy, Mehmed III Giray reclaimed his throne.

3 notes

·

View notes