#Stromsburg

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nu väntar hårda tag - men överlever USA som invandrarland?

Det är 74 miles, det kortaste köravståndet, från Aurora, Colorado till Stromsburg, Nebraska. En dagsutflykt på den stora nordamerikanska kontinenten, från en diaspora till en annan, från venezuelanska arepas till svenska köttbullar. Få saker är så tillfredsställande för en svensk USA-korrespondent som att besöka de gamla svenska byarna i det nya landet. Få saker är så sorgliga som att möta…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

2020 JCB 270 Looking for a reliable and versatile machine that can help you get the job done? Look no further than the 2020 JCB 270. With only 588 hours on the clock, this machine is practically new and ready to work for you. It boasts a powerful 74...

0 notes

Text

We Can Get More Done With Teamwork

–What we cannot do alone – we can do together. More than 350 people of the tiny town of Stromsburg, Neb., formed a human chain to transfer thousands of books from the town’s old library to its new one. Residents stood shoulder-to-shoulder to pass sacks containing a few books each to the new facility, a distance of a few blocks. Most of the old library’s contents were trucked over in advance,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Stromsburg, Nebraska's Grant Dawson earns 4th UFC win at 'UFC Fight Night 172' on Yas Island, Abu Dhabi

Stromsburg, Nebraska’s Grant Dawson earns 4th UFC win at ‘UFC Fight Night 172’ on Yas Island, Abu Dhabi

Nad Narimani, Grant Dawson (©UFC)

Grant “KGD” Dawson, 26, of Stromsburg, Nebraska, United States earned his fourth victory in the Ultimate Fighting Championship on Yas Island in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. The Nebraskan mixed martial artist was one of the “UFC Fight Night 172” winners.

Featuring 12 MMA matches, “UFC Fight Night 172” took place on the UFC Fight Islandon Yas Island on July 19,…

View On WordPress

#Abu Dhabi#Grant Dawson#Nad Narimani#Nebraska#Stromsburg#UFC fight island#UFC Fight Night 172#Yas Island

0 notes

Photo

The Black Man Who Invented Nebraska Football:

Before the opening weekend of the Big Ten football season, the conference sent a press release outlining the ways each school would support the league’s “United as One” social justice campaign. Many of those efforts involved stickers, logos, T-shirts, and other ways of distributing messages such as “End Racism” and “Equality.” But it was the University of Nebraska, alone among Big Ten teams, that made a nod to history, using a helmet sticker to pay tribute to the school’s first Black football player, George Flippin.

As it turns out, Flippin’s story resonates far beyond Nebraska, illuminating racial dynamics within college football and American culture more broadly. It also raises the thorny question of what we should remember when we look at the past. For Nebraska, the choice to honor Flippin was a gesture of unity in the midst of racial unrest. “In a lot of ways I think society should mirror locker rooms when you have good cultures built,” Nebraska coach Scott Frost remarkedwhen asked about the tribute to Flippin. The reality of Flippin’s time at Nebraska, however, suggests that any celebration needs to be coupled with a reckoning.

Flippin was born in Ohio three years after the end of the Civil War, eventually moving to Kansas and then Nebraska. He arrived at the state university in 1891, a few months after the school organized its first football team. By the fall of that year, Flippin had been recruited to join the squad, and he saw his first live action against Iowa on Thanksgiving weekend. It was the fifth game in Nebraska’s history and the first against an out-of-state opponent.

Nebraska (or the “Old Gold Knights” as they were known that year) lost that day, but Flippin caught the eye of the victors. “For Nebraska,” the Iowa student newspaper declared, “Flippin, the colored left half back, undoubtedly did the best work.”

What that statement lacks in detail it makes up for in significance. At the very beginning of Nebraska’s football history, the player carrying the banner for the state was a Black man. While there were a handful of other Black athletes at predominantly white colleges at the time—George Jewett at Michigan, William Henry Lewis at Harvard—Flippin was the only one building a football tradition from the ground up.

Over the next three seasons, Flippin continued to lead the way. The Illinois student newspaper recognized him as Nebraska’s “star.” A Kansas newspaper declared that he “had no rival in the West.” And reports out of Colorado said that Flippin “gave Denver more trouble” than anyone on Nebraska’s team because of his “weight, strength, and good playing.”

While Flippin did sometimes draw praise from Nebraska’s opponents, they didn’t typically react with the same levity. One commented on Flippin’s “peculiar and perhaps natural habit of butting his opponent with his head” while another castigated him as “an exceedingly brutal player.”

From Nebraska’s perspective, Flippin was simply giving out what he was getting. Game recaps told of Flippin being “kicked, slugged, and jumped on.” He was targeted, no doubt, because of his talent—but also, like numerous “racial pioneers” at predominantly white schools, because of his race.

Some teams used another method to counter Flippin’s greatness: They refused to play against him.

Missouri took this approach in 1892, forfeiting its matchup with Nebraska. The Nebraska student newspaper rushed to Flippin’s defense, framing Missouri’s boycott as a lingering effect of the Civil War. “Our team is truly representative, both of our principles and our members,” the editor declared. As for Missouri: “They believe what their [pro-Confederate] fathers believed. If they do what their fathers did, they will have to be whipped as their fathers were whipped.”

By embracing Flippin, Nebraska was claiming racial inclusion as part of its identity. But framing the Missouri-Nebraska divide in Civil War terms concealed the reality of American life in the late 19th century. It was not just Southern and border states like Missouri that were implementing Jim Crow laws. With the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling in 1896, the Supreme Court of the United States sanctioned this reassertion of white supremacy across the United States.

After a game in Denver, Flippin was denied entrance to an opera house. In Omaha, a hotel set up a private dining room for Flippin and his teammates rather than allowing him to eat in a public space. And in Lincoln—a community that praised itself for supporting a Black man’s exploits on the football field—Flippin sued a bathhouse for refusing to admit him on account of his race. That suit was unsuccessful.

Flippin understood the bind that Black people faced in America. “Whenever he demands the rights of citizenship he is accused of self-seeking,” he declared in a speech. The fact that Flippin sued a business that had discriminated against him makes his willingness to fight against racial discrimination very clear. But he also saw the limits of what he could hope to achieve. So Flippin continued to take the football field, representing a state and school that did not always support him.

After the 1894 season, Flippin’s teammates voted 8–7 to have him serve as the captain of the next year’s team. A backlash ensued immediately. Newspaper reports claimed the result was an accident, the product of political maneuvers by rival fraternities. They declared, too, that several Nebraska players would decline to take the field if Flippin retained his title.

This opposition to Flippin’s captaincy was not universal. Eight teammates had voted for Flippin, after all, and the Omaha World-Herald published an editorial on his behalf, arguing that football should be a democratic game, open to all. “If he were white, the university and the whole west would be so proud of him that he would be dressed in purple and carried on a floral wreath,” the editor of a Kansas newspaper wrote.

Despite this support, the tide was turning against Flippin in Nebraska. His physical play had endeared him to fans in the past; now it became an excuse to deny him the captaincy. A Lincoln newspaper reported that students feared Flippin’s penchant for “brutality” would lead him to “inculcate that kind of playing if he is permitted to captain the team.” Nebraska’s head coach, Frank Crawford, further denigrated his best player. “It takes a man with brains to be a captain: all there is to Flippin is brute force,” he said before predicting that Flippin would be forced to relinquish the title of captain.

There was no public announcement that Flippin had been stripped of his captaincy. But by the time the 1895 season began, he’d moved on from Nebraska, even as the new narrative about him remained. “He takes into the game no brains or skill,” the Nebraska student newspaper remarked in 1897, before describing the former star as “a disgrace to the college game.”

By that time, Flippin was attending medical school in Chicago, playing football to cover his educational costs. After completing school and becoming a doctor, Flippin made his way back to Nebraska, serving the Stromsburg community, about 60 miles west of Lincoln, until he died in 1929.

Upon his death, Nebraska fans rewrote history, eliding the fact that Flippin had been disrespected, discriminated against, and run out of town. A World-Herald sportswriter memorialized Flippin as “the charging bull, into which was bred the tenacity of the bulldog, the ferocity of the tiger, the gameness of the man who knows no fear.” Left unsaid was the fact that Black athletes were no longer allowed to compete for Nebraska. In 1892, Nebraska students had marveled that Missouri would defend the idea of racial segregation in a “progressive age.” By the 1910s, they had joined Missouri’s side, drawing a color line that would remain in place until after World War II.

As the Cornhuskers honor George Flippin in 2020, it’s the full scope of his experience that must be remembered. We should celebrate that Flippin integrated the football team and helped launch the program. We should also dwell on the fact that he was rejected by the predominantly white school and state he represented—as were generations of Black athletes after him, including some today who have said that their full humanity is not always valued.

To truly remember George Flippin, then, is to confront the reality of what America was and continues to be. A helmet sticker can remind us of a name from the past. It can’t force us to right the wrongs of history, or to do the work we need to do to examine our actions in the present day.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

George Flippin

George Albert Flippin (February 8, 1868 - May 15, 1929), was born in Ohio to Charles and Mahala Flippin. His father, a freed slave who fought in the Civil War on behalf of the Union, ultimately became a physician after attending the Bennett Eclectic Medical School in Chicago. His mother died when he was very young, but his father later married a white physician who was an alumna of Bennett Eclectic Medical School as well. Flippin graduated from high school in Henderson in 1891, and later enrolled at the University of Nebraska from 1891 to 1894.

Flippin, the first African-American football player for the University, became its star player. Although Flippin was a great player, he was still exposed to racism. In 1893, he was voted captain by his fellow players, but the newly hired coach, Frank Crawford, refused to offer him the position. He was quoted as saying, “It takes a man with brains to be a captain; all there is to Flippin is brute force.” Despite Crawford’s opinion, Flippin became president of the Palladian Literary Society, sergeant-at-arms of the 105-member University Debating Club, and a charter member of the University Medical Society in Lincoln.

In 1898, Flippin started medical training at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Chicago. He graduated in 1900 and worked in Chicago and Pine Bluff, Arkansas, before setting with his wife, Georgia Smith, in Stromsburg, Nebraska, in 1907. In Stromsburg, his father and step-mother had established a medical practice.

Flippin built the first hospital in Stromsburg, which is now a local Bed and Breakfast. He was a well-respected doctor and surgeon who was known throughout the state for making house calls. Whether a person could pay or not, Flippin always tended to the ill.

Although he was a physician, his status as an educated professional did not protect him from discrimination. Flippin was part of an early civil rights case in Nebraska, in which he was denied service at a restaurant.

George Flippin died May 15, 1929. In 1974, he was inducted posthumously into the University of Nebraska Football Hall of Fame.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

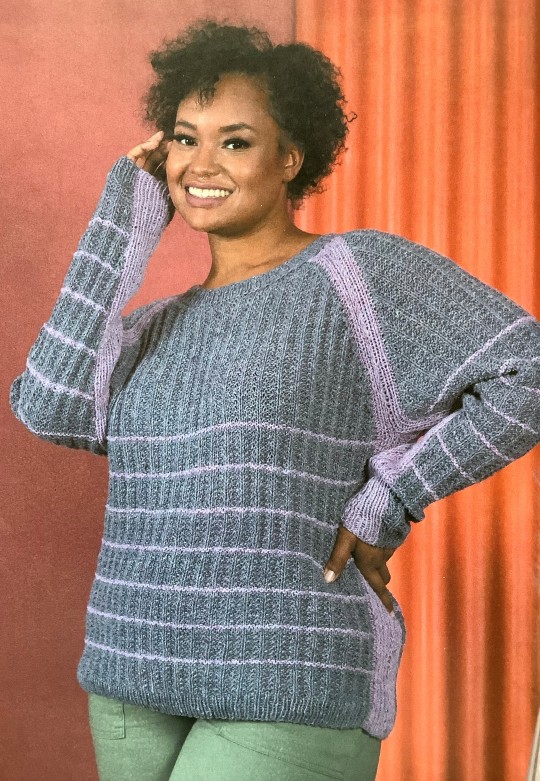

Interweave Knits, Fall 2022

This issues includes 2 cardigans, one of which is the beefy, belted one on the cover called Susurrous Cardigan by Olya Mikesh in Universal Yarn Deluxe Worsted. This is a wool yarn and this cardigan uses six colors of yarn and is a 3 out of 4 for difficult.

There are 4 pullover sweaters and my favorite is the Ramulose Pullover by Nadya Stallings. It has both vertical ribs and horizontal stripes, but I think skipping the latter makes more sense unless you really like a boxy look. Then if you left the color change at the raglan shoulders and at the sides, you would be repeating the vertical lines of the ribbing and still get some color play. It is a 3 out of 4 for difficult. It is done in Green Mountain Spinnery Sylvan Spirit which is a wool and Tencel blend.

3 hats including the color-work Peiskos Tam by Tonia Lyons which is also on the cover in the small photo on the left. This tam features 8 colors in Harrisville Designs Shetland yarns especially oranges and greens. This is a 3 out of 4 for difficulty but there is a nice big chart of the pattern included. The other interesting hat is the Sirimiri Slouchy Hat by Danieli Nii which has elongated stitches created by wrapping the yarn around the needle multiple times. It is a 3 out of 4 for difficulty. It is done in dark blue and paler blue using The Fibre Co. Road to China Light and Cirro. Both are blends so you get a real mix of fibers from alpaca, camel and cashmere to wool and silk.

There are also 2 sock patterns, an article on The Fiber Mill in Stromsburg, NE which processes wool fiber from around the United States and a technical article by Kyle Kunnecke on steeking, or cutting, a knitted sweater in order to finish the opening with buttonholes or a zipper, plus the usual columns on yarns and products.

Find it at your local yarn store, LYS, or online here: https://www.interweave.com/product-category/knitting/knitting-magazines/knitting-magazines-interweave-knits/

#interweave knits#interweave#knitting patterns#knitting#local yarn store#lys#susurrous cardigan#olya mikesh#universal yarn#ramulous pullover#nadya stallings#green mountain spinnery#peiskos tam#tonia lyons#harrisville designs yarn#sirimiri slouchy hat#danieli nii#the fibre co.#the fiber mill#kyle kunnecke#steeking#makers#making

1 note

·

View note

Text

People who residents of Stromsburg, Nebraska know well are trying to harm or kill me for inheritance money and custody papers. Because i moved to Peru and was trapped here in Peru since 2013

No one had any business stepping into Star's life after Elizabeth Monica Coca got deported in June 2018. Joseph Taylor can still go to prison for trafficking Star Monique Gonnerman to Lima Peru from June to October 2018, and the rest of the Coca Cabra family who brought Star to Lima in 2019 January. To use Star to lure me in to be harmed or killed by hired or contracted killers. And February 2019, Emiliano was killed.

No one is making problems in my life. Except my family, and ex wife and her famioly. And my dad and his extended family. Over 1. Inheritance i don't care about. 2. Life insurance money they are mad i wont die for them. 3. Custody papers for Star Monique Gonnerman because she has been kidnapped since 2017.

And i told Joe Gonnerman give your IRA you intended for me to Leland and Alissa and Judy Gulbrandson. Give trash earned dirty money to trash dirty people. Give it to Jnel and Rick Gruber.

0 notes

Text

York's Randy Johnson is a dean among pole vault coaches

York’s Randy Johnson is a dean among pole vault coaches

YORK – Stromsburg native Randy Johnson retired from teaching at York High in 2011. Johnson, who joined the York teaching staff in 1979-80, continues to work with pole vaulters at York High School and even some surrounding schools. He is considered one of the area’s best when it comes to teaching kids how to familiarize themselves with the sport. READ MORE

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Stromsburg Queen Platform Bed https://ift.tt/2P3NeSq

0 notes

Photo

Stromsburg Queen Platform Bed https://ift.tt/2m40kT8

0 notes

Text

Can You Spare A Minute 7/30?

youtube.com/shorts/D7OA4VBTKxY If you can’t find two minutes can you spare just one? 7/30–Can You Spare A Minute? What we cannot do alone – we can do together. More than 350 people of the tiny town of Stromsburg, Neb., formed a human chain to transfer thousands of books from the town’s old library to its new one. Residents stood shoulder-to-shoulder to pass sacks containing a few books each to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Stromsburg Queen Platform Bed https://ift.tt/2ycgblu

0 notes

Photo

Near Stromsburg, Nebraska? Come out for a fun Swedish Midsommar Festival! Saturday, June 15, 9-5pm in the town square! We are representing @mmwwco @jeff_mmwwco @erindavidpeterson @bonlacy @eddiechristy selling reclaim wood frames, coasters, serving boards! Get your brochures about the reclaim-inspired new build homes! #wood #reclaimwood #reclaimframes #nevernevernevergiveup #remembertohavefun #bonnielacy #festivals #midsommarfestival2019 #stromsburgnebraska #swedishheritage https://www.instagram.com/p/BytNFXcgckr/?igshid=12bwlf5hmgy82

#wood#reclaimwood#reclaimframes#nevernevernevergiveup#remembertohavefun#bonnielacy#festivals#midsommarfestival2019#stromsburgnebraska#swedishheritage

0 notes