#Stanley Szwarc

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Stanley Szwarc’s Visionary Cross Purposes Stanley Szwarc (1928-2011), a Polish book keeper turned metal worker and then artist after arriving in the United States, gave no indication of being particularly religious, but he did like making crosses. A prolific creator of objects from scrap stainless steel, always demonstrating over-the-top imagination, Szwarc made hundreds of crosses, if not thousands. He produced jewelry, he made crosses to be hung on the wall, and he crafted cruciform objects with no apparent use other than to be carriers of his endless combinations of geometric shapes. Szwarc liked to say that no two of his objects, be they crosses, vases, key fobs or boxes, were alike. The evidence plainly supports that contention while demonstrating a virtuosic artistic vision that could not contain itself, always seeking out fascinating ways to vary the ornamentation, to create objects of surprise, delight and striking beauty. Szwarc was one of the great self-taught artists of the 20th Century.

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

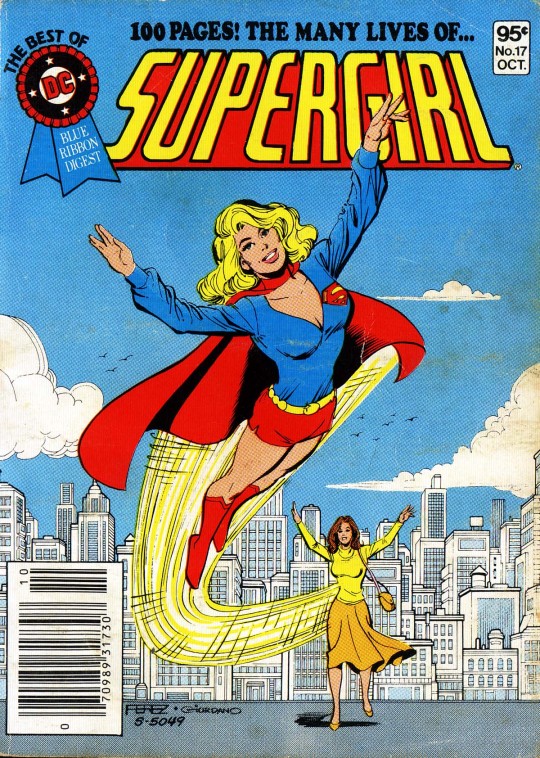

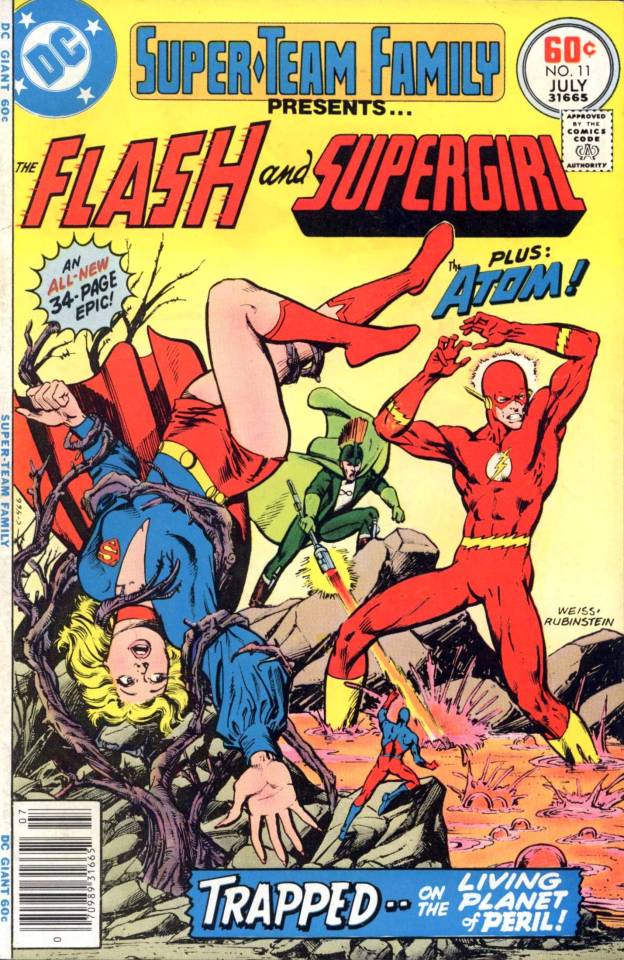

Sixty fun & fascinating facts about the classic Supergirl (3 / 4)

Welcome to the third part of this series presenting sixty fascinating facts to celebrate the sixty years since the debut of the classic Supergirl in DC Comics. Ahead are another fun-filled fifteen snippets of trivia about the original intrepid Argo City teen who leapt from that crumpled Midvale rocket ship. Covering her original Silver and Bronze Age incarnation, in comics and on screen, each factoid is calculated to intrigue and delight – hopefully even seasoned Kara fans will find a few morsels of trivia that had previously escaped their attention.

Enjoy...

31. You can actually visit, in real life, the building where she once lived.

While Superman has rarely strayed beyond his fictional base of Metropolis, Supergirl’s adventures have seen her relocate far-and-wide many times. Some of her homes have been fictional, like Midvale and Stanhope, while others have been real-life, like San Francisco and Chicago. But shockingly, not only has the Girl of Steel lived in real locations, but she has even inhabited real addresses.

A panel in Daring New Adventures of Supergirl #4 (Feb 1983) exposes Linda Danvers’ home address as 1537 West Fargo Ave, Chicago – surprisingly, this turns out to be a genuine address. A later issue, #7 (May 1983), reveals that Linda’s apartment number is 12A. The building that’s currently at that location doesn’t correspond with the one drawn by Carmine Infantino, but if you happen to be passing you might want to check if one of the occupants is listed a “Ms. L. Danvers”.

32. The first theatrically released Supergirl movie was in 1973, not 1984.

As outlined in factoid #2 there was an abundant supply of superheroine movies in non-English speaking markets before Helen Slater’s Supergirl. Indeed so incredibly popular are superpowered females in some corners of the globe that, amazingly, there was even an unofficial Girl or Steel movie over a decade before the authorised Salkind-produced one. The film in question starred Pinky Montilla in the main role and was entitled simply Supergirl. Released on 23rd September 1973 into the Filipino market, the movie featured the Maid of Might’s early 70s costume but changed her origin story. Pinky would also play Bat Girl in 1973′s Fight! Batman, Fight! – and we can assume that the producers probably didn’t ask DC for permission to use the Dominoed Daredoll either.

33. She hated her time in Midvale Orphanage.

The Silver Age always presented Kara’s adventures with a naive sense of wonder and amazement; rarely did it seriously address the pain she must have felt at leaving her parents behind to die in Argo City. But comics changed a lot in the two decades after Kara was introduced, and by the time Supergirl’s origin was retold in Daring New Adventures of Supergirl #1(Nov 1982) a very different spin was put on things. As Kara travels to begin a new life in Chicago, she reflects back on her tragic beginnings as a superhero, including the painful loss of her parents and her feelings of starting over in Midvale: “I was a real stranger in a very strange land! With nowhere else to go, Superman had no choice but to place me in Midvale Orphanage under the name Linda Lee.”, she recalls, before concluding solemnly, “I hated it!”

34. She was a reluctant hero, often feeling out of place on Earth.

One theme that reoccurred during the Bronze Age adventures of Supergirl is how Kara felt at odds with her career as a superhero, and out-of-place on Earth. A story in Superman Family #168 (Dec 1974) demonstrates this more than most, as it brings together three troubled women with extraordinary powers. Supergirl joins her friend Lena Luthor (who has ESP) in an attempt to help Jan Thurston (who has telepathy) come to terms with her unusual powers.

After rescuing a suicidal Jan, Supergirl wins her trust by recounting her own sad journey from Argo City to Earth, explaining that at first she enjoyed the novelty of her superpowers, but quickly came to see them as a barrier. “I’m the mightiest girl on Earth -- and the loneliest!”, she laments, “There’s not a guy on the planet who can keep up with me... Not a single girl can get close enough to be my friend! Sometimes I think I’d much rather have stayed on Argo City!” But Kara goes on to outline how she overcame those feelings: “People like us aren’t different!”, she explains, “We’re just... special!”

35. She planned to start a family, until Kal-El intervened.

In the Bronze Age, DC writers clearly felt free to explore introspective ideas with Kara that likely weren’t possible with her famous cousin. One short story, tucked in the back of Superman Vol. 1 #282 (Dec 1974), demonstrated this more than any other. Kal-El travels to Florida, Kara’s then home, to confront her about suggestions that she may give up her superhero career. “This life of a super-heroine takes up too much of my time... Sets me apart from everyone else!”, she explains. “I want an ordinary life -- with a husband and children some day... Free to do what I choose!”

Naturally her straight-laced cousin isn’t too keen on this idea. He spins Kara a yarn from ancient Krypton folklore, the moral of the story being that she should be careful what she wishes for. “So you see, Kara”, he explains, “sometimes, when we get the things we think we want most... they turn out to be a curse rather than a blessing!” In light of this, Kara reconsiders her plans.

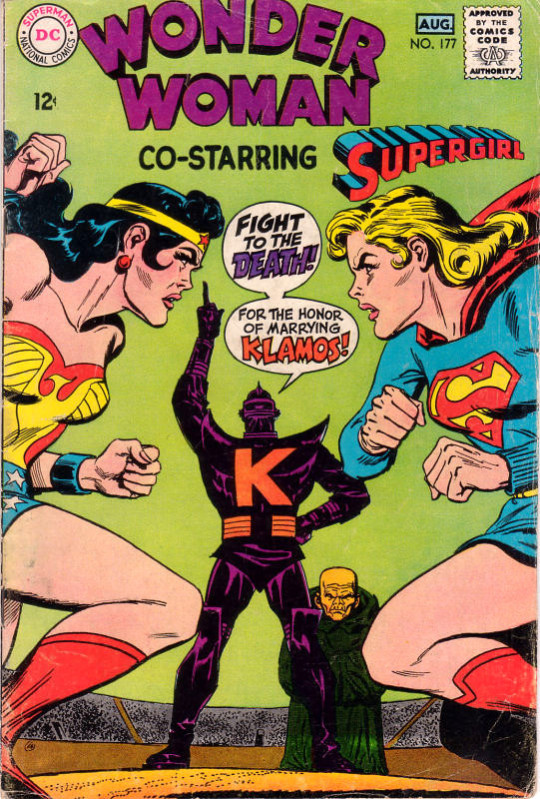

36. Wonder Woman designed one of her costumes.

As most fans know one of the few weaknesses the Man and Girl or Steel share is a vulnerability to magic; so when Adventure Comics #397 (Sep 1970) saw Kara go up against a powerful black magic cult, it was perhaps no surprised to find her badly beaten and her costume shredded. Luckily Wonder Woman was in her mod Emma Peel phase at the time, posing (in-between bouts of super heroics) as the owner of a fashion boutique. Reaching into the racks of clothes at her shop, Diana produces a completely redesigned Supergirl outfit befitting the fashions of the period, which Kara eagerly adopts. (Readers were left wondering whether Diana had redesigns of other hero costumes at the ready, or was Supergirl a special case?)

37. Her mom(s) designed two of her costumes.

Every Supergirl fan knows that Kara’s original costume was designed by her mother, Alura, so that the teenager would be recognised immediately by the Man of Steel when she arrived on Earth. But few may remember that her mid-80s costume, the headband affair she wore going into Crisis on Infinite Earths, was also designed by her mother -- her other mother. Kara’s 80s costume was design by Edna Danvers, her adopted mother on Earth, who (it seemed) was in the habit of whiling away the long dark evenings in Midvale by sketching possible costume designs for her superhero daughter.

38. She’s a fan of recycling her clothes.

The Maid of Might has had many costumes over the years -- or rather, she’s had one costume that she’s recycled over and over since the early 70s. In Adventure Comics #407 (June 1971) a new invulnerable costume was given to Kara by the folks in the Bottle City of Kandor after her original Argo City outfit had been destroyed some months before. A dedicated follower of fashion, over the coming months Kara went through a succession of wild and wacky outfits, some lasting only one issue, before finally settling on her famous hot pants attire for the majority of the 1970s. One might have assumed that somewhere in the Fortress of Solitude there was a wardrobe packed full of retired red and blue super-duds, but Supergirl Vol. 2 #13 (Nov 1983) revealed Kara’s secret -- when it comes time to upgrade her outfit, Kara unravels her old costume at super-speed and and re-weaves the resulting ball of thread into the new design.

39. Demi Moore was the director’s first choice to play Lucy Lane in the Supergirl movie.

The casting net for the title role in 1984′s Supergirl was spread far-and-wide. Director Jeannot Szwarc asked casting agent Lynn Stalmaster to search the whole globe for candidates who could not only act, but withstand the physically and mentally pressure of training for the demanding stunts and wire work. One candidate, apparently, was Demi Moore, who didn’t get the Girl of Steel role but was considered perfect for Kara’s best friend, Lucy Lane. Director Jeannot Szwarc recalled in a 1999 interview, “I met tons of girls. I remember one of the girls was Demi Moore. She was very young and had a great voice. I wanted to use her for the room mate.” But it seems fate had other plans for Ms Moore, as Szwarc explained, “She would have been [perfect], but she was going to Brazil to do a movie with Michael Caine.“ (Moore played Caine’s daughter in Stanley Donen’s rom-com, Blame It on Rio.)

40. One of her rarest appearances is from 1981, only a couple of pages long, but sells for $75+.

If there was a competition to find the rarest publication with an original Supergirl story, Danger on Parade / Le Danger Guette would surely be hot favourite for top place. This tiny comic, just eighteen panels long, was given away inside packets of breakfast cereals in Canada. It features an abbreviated adventure pitting Supergirl against Winslow Schott, aka the Toyman, in the pair’s only pre-Crisis encounter. Runner-up in the rarity stakes would likely go to the Super A and Super B booklet sets produced by Warner Books in 1977 for use in classrooms. The sets didn’t feature original stories however, but reprints with simplified speech balloons designed to teach reading skills.

41. She first met Kal-El years before she landed on Earth.

Gimmick story lines were the order of the day for Silver Age DC, and what better way to create an attention-grabbing dime-baiting cover than to arrange a bizarre crossover -- such was the case with Action Comics #358 (Jan 1968), which saw a very youthful Kara Zor-El in Argo City meet Superboy. The story is predictable fare: in deep space Superboy is scooped-up by one of Zor-El’s science probes, which brings him back to Argo City. Naturally Kara is the first one to discover the probe’s accidental passenger, and (naturally!) Kal-El has suffered memory loss that blots out his life on Earth. Kal and Kara become firm friends over the coming days, until (naturally!) the plot contrives to wipe her memory of him, and restore his memory of Earth.

42. Lena Luthor was the only friend who knew her secret identity.

In the 2015 Supergirl tv show, famously, everyone seems to know (or have known at some point) Supergirl’s secret identity... except Lena Luthor. Bronze Age DC Comics, however, were very very different: Lena first met Kara in Action Comics #295 (Dec 1962), using the name Lena Thorul to hide her connections to brother Lex. Instantly she became firm friends with both Supergirl and Linda Danvers, requiring Kara to work extra hard to stop Lena from realising they are one in the same. The deception finally ended in Superman Family #211 (Oct 1981) when Lena confessed to Kara that she’d worked out her dual identity. This made Lena the only ever friend of Linda Danvers who shared her secret. Sadly it didn’t last long, as by Superman Family #214 (Jan 1982) Lena had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage which affected her memory.

43. She didn’t put the “Kara” into Karaoke.

Over the years Supergirl has exhibited some remarkable super skills, including super ventriloquism, incredible memory, and even the ability to read minds, but one skill that she seemingly lacks is any kind of musical aptitude. Despite the modern day tv Supergirl claiming to put the Kara into Karaoke, her comic strip counterpart didn’t ever appear to sing (not even in the shower!) What’s more, as she confesses in the pages of Adventure Comics #409 (Aug 1971), she doesn’t play any musical instruments either.

44. She’s was no stranger to tragedy even before she left Argo City.

Very few Silver or Bronze Age stories dealt with Kara’s life in Argo City, but one story that gave some idea of how she filled her time appeared in the pages of Action Comics #371 (Jan 1969), when a very young Kara is shown witnessing the cruel death of her best friend, Morina. The pair are innocently playing the game Zoomron, involving the throwing a Frisbee-like disc (the Zoomron) at a target. Chasing an erratic disc Morina tumbles into a crevice filled with Kryptonite, and a tearful Kara can only stand and watch as her friend succumbed to the deadly rays.

45. The Supergirl movie was almost entirely filmed in the UK.

Most fans know that Superman I and II owe a lot to Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire, northwest of London, so it is no surprise that 1984′s Supergirl returned to use the same studio complex. But while Superman complimented its studio shots with exteriors filmed in New York (Metropolis) and Alberta, Canada (Smallville), Supergirl’s production stayed firmly within the UK. Locations included the banks of Loch Moidart on the west coast of highland Scotland, the Royal Masonic School for Girls in Hertfordshire, and Black Park Lake near the Pinewood soundstage in Buckinghamshire. Shockingly, even downtown Midvale was actually a huge sprawl of street facades constructed as a backlot set at Pinewood -- the 22 days it took to shoot the tractor rescue sequence was allegedly due to the notoriously fickle British weather.

That’s all for part three. The final part, with even more extra-juicy Kara Zor-El trivia, will be available soon.

#supergirl#superhero#comics#dc#dccomics#superheroine#karazorel#kara zorel#silver age#bronze age#superman#luthor

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 Artists Using Silicone to Create Strange, Radical Artworks

I am a woman and I cast no shadow, #17, 2016. Ilona Szwarc AA|LA

Silicone has a meandering, illustrious history. British chemist Frederic Stanley Kipping pioneered some of the first major investigations into the compound (which is made up of silicon and oxygen atoms) in 1927. Since then, its shape-shifting potential has inspired everyone from astronauts to plastic surgeons: Neil Armstrong wore silicone-tipped gloves during the first-ever moonwalk; cosmetic surgery has long relied on the material for breast implants; and it’s a favorite of both sex-toy and cookware companies.

Given its potency in popular culture, as well as its malleability, it’s no wonder that silicone has inspired artists, too. In its solid, rubbery form, it easily conjures distinctions between the natural and the man-made. It evokes a consumer society obsessed with performance, innovation, and the pliability of self-presentation—metaphor is, indeed, embedded in its chemical make-up.

Many sculptors who work with the material are also intrigued by its connection to the uncanny and grotesque. “I like silicone because of its flesh-like consistency and the way it holds light,” artist Hannah Levy explained. “There’s a kind of luminosity to it if you add just the right amount of pigment that makes it look like it has some kind of life of its own.” She’s used the medium to construct works that approximate objects as varied as a pink swing, a massive asparagus stalk, and deck chairs. Below, we examine Levy’s work and that of seven other contemporary artists who use silicone to unique, radical ends.

Jes Fan

Disposed to Add, 2017. Jes Fan Team Gallery

Testo-Candle , 2017. Jes Fan Team Gallery

Jes Fan, Soft Goods, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Jes Fan, Systems II, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Jes Fan, Systems II (detail), 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

For Jes Fan, silicone evokes early memories. He discovered the material through his father, who worked as a mold-maker for toys. Early on, then, Fan already associated it with both play and consumer products.

Silicone has appeared in the Brooklyn-based artist’s work as platforms for soap and a candle (both made with sex hormones), slippers, and ropy flesh-toned sculptures—smooth in the middle, with screw-like texture on the ends. More recent creations, Systems II, Systems III, and Visible Woman (all 2018), resemble intricate jungle gyms. While lively, the pieces also engage serious perspectives on gender, race, and sexuality.

“Silicone is almost like a liquid skin, an abject net-flesh packed with erotic and queer connotations,” Fan said. “I generally gravitate towards materials that display characteristics of transformation, like liquid caught in a state of solidifying. Silicone is a great material to highlight that.” Yet his inspirations also range far beyond the body: Fan is fascinated by laboratories, factories, East Asian diasporic politics “by way of Chinese bakeries on Canal Street,” and more.

The artist’s oeuvre suggests an extended network of identities, philosophical ideas, and art-historical references (like the use of the everyday object, or “ready-made”)—and a creative mind more inclined to connect such disparate elements than to divide them.

Hannah Levy

Hannah Levy, Untitled, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Performance featuring Hannah Levy's work at MoMA PS1, New York, 2018. Choreography by Phoebe Berglund. Courtesy of the artist.

Performance featuring Hannah Levy's work at MoMA PS1, New York, 2018. Choreography by Phoebe Berglund. Courtesy of the artist.

Hannah Levy, Untitled, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Hannah Levy, Untitled, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Hannah Levy, Untitled (detail), 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

For a 2017 performance at MoMA PS1, Levy dressed three dancers in silicone and latex costumes. They all appeared to be wearing transparent rain boots, and two donned what looked like ivory-hued, bubble-textured hoodies with extra-long sleeves. If the outfits were out of the ordinary, they weren’t all that different from what one might see on a high-fashion runway. Levy, who is now represented by New York gallery Casey Kaplan, often riffs on design through creating her own approximations of clothing, furniture, and even objects entirely unexpected in an art gallery setting. For a recent group exhibition at Company Gallery, she created giant orthodontic retainers from alabaster and nickel-plated steel.

Humor pervades much of Levy’s practice, and stretchy, unserious silicone aids her to that end. It lacks the gravity of marble, the gentleness of wood, and the fragility of glass. Levy described the texture of silicone as “relatable to the experience of having a body.” Pinching it inspires a similar feeling of pressure in the viewer. “There’s also a delightful stickiness to the material,” she said. “It’s ultra-clean, ultra-slick, and completely filthy in its propensity to attract nearly all particles to its surface. Everything leaves a trace, but nothing permeates its slick exterior. It’s the material of prosthetics, medical equipment, Hollywood horror films, and non-stick baking sheets.”

Donna Huanca

Performance of Donna Huanca, Scar Cymbals, at Zabludowicz Collection, London, 2016. Courtesy of the artist, Peres Projects, Berlin and Zabludowicz Collection, London.

Performance of Donna Huanca, Epithelial Echo, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Performance of Donna Huanca, Cell Echo, at the Yuz Museum, Shanghai, 2018. Courtesy of the artist, Peres Projects, Berlin and Yuz Museum, Shanghai.

Performance of Donna Huanca, Surrogate Painteen, at Peres Projects, Berlin, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Peres Projects, Berlin.

When asked what she finds most interesting about silicone, artist Donna Huanca offered an equally intriguing answer: “the ephemerality of it, the smell.” The material does, indeed, produce a synthetic reek. Embedded in artwork, it produces olfactory sensations that can intensify a viewer’s visual experience.

Huanca (who shows with Berlin gallery Peres Projects) has long been known for her performances that situate paint-covered models in the gallery setting among her multimedia sculptures, and she’s recently added silicone to her repertoire to heighten the drama. She gives her performers glass vials filled with liquid silicone and their choreography invites them to paint it, intuitively, onto plexiglass. “These silicone paintings are temporary, as they peel the silicone once dried,” Huanca said. “I love the idea of creating ephemeral paintings.” The fleeting nature of the artworks encourages the audience to enjoy the moment.

Huanca said she’s particularly interested in Andean futurism and meditative practices. Her art often suggests an alternate realm, decades from now, where nude women aren’t watched for titillating purposes, but for their own creative potential.

Ilona Szwarc

I am a woman and I cast no shadow, #21, 2016. Ilona Szwarc AA|LA

I am a woman and I cast no shadow, #14, 2016. Ilona Szwarc AA|LA

I am a woman and I cast no shadow, #17, 2016. Ilona Szwarc AA|LA

She was born without a mouth, 2016. Ilona Szwarc AA|LA

She lives without a future, 2016. Ilona Szwarc AA|LA

For a 2016 photography series entitled “I am a woman and I cast no shadow,” Los Angeles–based artist Ilona Szwarc cast a silicone mask from the contours of her body double’s head. The artist regularly employs women who look like her to participate in her projects; she takes on the role of “casting” director, in two senses of the term. Szwarc often paints her doppelgangers’ faces in grotesque new ways for the sake of compelling pictures. A Hollywood element prevails throughout her oeuvre—where else but a Tinseltown stage can we adopt new identities and personas so quickly?

“To make this work in Los Angeles is to dissect the everyday work of makeup artists working on film sets,” said Szwarc. “It’s to slow down and really look at every step of the processes that so many women and actresses go through daily, quickly, fully normalizing the experience.”

The artist is interested in what happens when she photographs the silicone molds themselves, while experimenting with lighting. According to her, “there is a moment of optical illusion in which the mold, although protruding away from the camera, registers in a photograph as if it were facing the lens.” Szwarc’s photographs are haunting intermediaries between fact and fiction, self and other, natural and contrived. They evoke that famous Andy Warhol adage—“I love Los Angeles. I love Hollywood. They’re beautiful. Everybody’s plastic, but I love plastic. I want to be plastic.”

Troy Makaza

Dislocation of Content, Part 1, 2017. Troy Makaza Depart Foundation

Dislocation of Content, Part 3, 2017. Troy Makaza Ever Gold [Projects]

Silicone’s versatility is a major draw for 24-year-old Zimbabwean artist Troy Makaza. “It does not confine me to a particular discipline,” he said. “I can paint or sculpt with it. I can create a wide spectrum of colors and textures, which are permanently flexible. It is a very playful medium, and play is key to my approach to making work.”

At first, Makaza’s works appear to be colorful, wall-mounted tapestries—twists, tangles, and droops of bright yellow, gray, and red threads. Upon closer examination, however, the “threads” reveal themselves to be squiggles of silicone-infused paint. The compositions, then, combine elements of painting, sculpture, and traditional craftwork. Their sheen and slick texture make them distinctly contemporary, even as they reference age-old art forms.

Yet Makaza’s ideas extend far beyond material innovations. “The flexibility, adaptability, and resilience of the medium also speak very strongly to how I see our lives here in Zimbabwe, navigating changing circumstances and balancing traditional modes and contemporary realities,” he said. Geopolitical concerns are especially evident in Dislocation of Content, Part 1 (2017), which resembles a tattered, misshapen red flag, and its sister piece, Dislocation of Content, Part 3 (2017), which looks—with its fields of different hues bumping against each other—like a fractured topography.

Hayden Dunham

Hayden Dunham, Tor, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Andrea Rosen Gallery.

Hayden Dunham, Ract Ress, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Andrea Rosen Gallery.

Hayden Dunham, Welt, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Andrea Rosen Gallery.

Hayden Dunham, Lail, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Andrea Rosen Gallery.

Hayden Dunham, Flex, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Andrea Rosen Gallery.

While some artists believe that their materials are talking to them, Hayden Dunham describes a more significant give-and-take with silicone. She spoke of the material as a personified being with its own agency. “I love how sensitive it is,” she said. “If it is raining out, it won’t cure. It responds to touch. It is a material that is listening.”

Dunham uses silicone in her sculptures, which often resemble solid puddles supporting a variety of other sculptural forms (a block, a pillowy roll) and even gases emanating from tubes: Walk into a gallery exhibiting her work, and you’d be forgiven for thinking you’d walked into a mad (color-fixated) scientist’s laboratory.

While Dunham has used bright blues and yellows throughout her work, she’s particularly fond of jet black—the color of ash and carbon. She’s interested in activated charcoal and its potential to clear out the human body by absorbing toxins and releasing them back into the universe. “Human bodies are large-scale filters,” she said. “They hold material dialogs we come in contact with everyday. When bentonite clay comes in contact with skin, it leaches heavy metals through pores. This process can’t be seen, but is present. So many of these interactions are not visible.” Dunham’s work argues that there’s enough fodder in the human body to inspire an entire artistic practice.

Ivana Bašić

Ivana Bašić, I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms #1, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Marlborough Contemporary.

Fantasy vanishes in flesh, 2015. Ivana Bašić Michael Valinsky + Gabrielle Jensen

Sew my eyelids shut from others, 2016. Ivana Bašić Nina Johnson

Ivana Bašić, I will lull and rock my ailing light in my marble arms #1 (detail), 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Marlborough Contemporary.

Ivana Bašić’s 2016 sculpture Sew my eyelids shut from others resembles a slab of slick, pink raw meat draped over a thin metal spit. The artist lists her materials as “wax, silicone, oil paint, stainless steel, weight, [and] pressure,” suggesting that invisible physical forces such as gravity are as much a part of the work as tangible media.

It’s no surprise that Bašić discusses silicone in scientific terms. She’s intrigued by the fact that it “has no specific innate state and characteristics, except for its capacity to perfectly simulate reality, which is why it’s used in special effects so much.” For her, it’s “a blank canvas with an endless amount of possibilities.”

Bašić has a background in digital scanning, 3D-scanning, and 3D-printing—which she’s explicitly decided not to employ in her sculpting practice. Instead, her pink or white sculptures often evoke bone or her own skin: They relate more to the human body than to any machine. She even titled a 2015 sculptural series “Fantasy vanishes in flesh.” Comprised of “feathers, pressure, cotton, silicone, [and] stainless steel,” the works look like pillowy bodies, torquing and bowing on the floor.

Amy Brener

Amy Brener, Flexi-shield (earth mother) (detail), 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Flexi-Shield (earth mother), 2017. Amy Brener REYES | FINN

Amy Brener, Flexi-Shield (bumper), 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Amy Brener, Drifter II, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Suspended from the ceiling, Amy Brener’s colorful silicone “Flexishields” (2015–present) resemble newfangled, feminized chainmail. Many take the shape of evening gowns, with protuberances at the bellies and breasts. Brener (who shows with Jack Barrett gallery in New York) encases found objects such as flowers, leaves, combs, and nails in the material, turning them into repositories for organic and man-made artifacts. She also embeds casts of her deceased father’s face, enhancing ideas about memory and time. “These imagined garments are protective barriers—shields—that are also delicate and translucent, addressing our ability to gain strength through vulnerability,” Brener explained.

While many of the artists on this list gravitate towards silicone’s slickness, Brener favors rough, worked-over surfaces. “Silicone is an amazing replicator of fine detail,” she said. “It has the potential to resemble anything from human skin to computer screens. I’m especially excited by its ability to imitate textures of cat-eye and fresnel lenses to create optical effects.”

For her 2018 “Drifter” series, Brener created silicone sculptures that sit on the floor like tombs or caskets, and filled them with light. Death and preservation still prevail as dominant themes, albeit with a very literal glow. For artwork that addresses morbidity, Brener’s approach is remarkably hopeful.

from Artsy News

0 notes

Photo

Hand machined snow flakes by visionary artist Stanley Szwarc.

29 notes

·

View notes