#Soviet history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Environmental protection poster from the Lithuanian SSR, mid-1970's

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

fwiw: a lot of people follow @roach-works who just reblogged yo ur comments on history, books, and authoritarian regimes' inability to indoctrinate entire populations.

I'm an ex classics major with a lot of history under my belt, who knows Rome sutmr under a corrupt oligarchy even when it coughed up a hairball like Nero or Commodus. (Of course, it helped that Rome worked on the pragmatic principle, "How can we keep society and infrastructure functioning, given that positions of power tend to be occupied by the rich & corrupt?" I like to joke that Western Rome never fell; it just became the mafia.)

At any rate, my tendency to see the US through the lens of Rome makes me a pessimist: I assume we'll manage even in a dystopia.

I'm working on expanding my knowledge of world history to counteract that, but it's great to check in with a sane historian who will help me resist crowdsourced panicmongering.

Look, as I have said, I 0% blame anyone for being scared. I'm scared. With no exaggeration or hyperbole, Shit Real Bad, and it's undoubtedly going to get worse, at least in some ways, before we have a chance to make it better. It was completely avoidable, but half of America decided they didn't want to avoid it, so here we are.

Nonetheless, as my last reblog also pointed out, there are still basic historical and critical-thinking skills that we can use here, and to acknowledge that even if it is obviously unprecedented to us, it is not unprecedented to others, and we can study those lessons and think about how to apply them to our own situation. Rome is the obvious model for a world empire brought down by corruption, oligarchy, imperialism, endless foreign wars, income inequality, economic upheaval, excessive militarism, etc etc, but it's not the only one, and the "fall of Rome and start of the Dark Ages" is one of those narratives that gets my premodern-historian rant especially exercised. By the time Rome "fell" in 476, the city of Rome wasn't even the capital of the Empire; the western capital was in Ravenna, northern Italy, and the eastern capital was in Constantinople, where it endured for another thousand years. Roman successor kingdoms were founded in Visigothic Spain, Merovingian Francia, etc., and often imported Roman law, religion, bureaucracy/administration, and nobility relatively unchanged, which is why Latin was the legal, ecclesiastical, and educational language of western Europe until as late as 1962 and Vatican II. The "Dark Ages" are likewise at best an extreme simplification and at worst exceedingly misleading imperial-nostalgia propaganda. Etc etc. I will restrain myself.

Rome dominated the (European/Near Eastern/north African) world in the way that the 19th-century British Empire dominated the actual world and American empire dominates now, at least for the moment, and thus we have to recognize that similar dynamics are at play here in a late-stage imperial decline. However, Rome did not just up and vanish in a puff of smoke one day and never appear again, and we also have to recognize that the end of empires is generally a good thing, historically speaking. Yes, absolutely a turbulent, dangerous, and traumatizing time, especially for those living within the imperial core, but still. There's also the blunt fact that America itself has been responsible for a lot (a LOT) of violent regime change, coups, overthrows, bombings, and other disastrous foreign policy interventions for almost the entirety of its existence, and we can't pretend that we are just the shining beacon of unproblematic truth, freedom, and faith that most conservatives, and a lot of saccharine American-exceptionalism liberals, tend to think. If that comes back to bite us and we have to experience the kind of political and social upheaval that we have arrantly and unrepentantly inflicted on other places in the name of our Superior Right... well.

As for the post about history books (here), that was another attempt to push back against the kind of broad-strokes fearmongering that is often prevalent right now. Again: for completely understandable reasons, but still. There is literally no way on earth that the practice of academic history, or the procession of human events, is going to be destroyed because an orange dumbass and his idiot followers took power in America for eight nonconsecutive years. Even if by some miracle he managed to do it in America and the only thing ever officially published was Heritage Foundation balderdash, a) historians in countries other than America would still be writing books about it, and b) again, literally impossible. To return to the history of Soviet totalitarianism that I was addressing in that post, I suggest that people look into the samizdat, the contraband news and literature widely shared in the USSR. They faced far more stringent conditions than we ever will: the KGB controlled access to all word processors and copiers, precisely because they could be used to spread non-regime-approved information, and dissidents had to write and circulate it by hand. If they were caught, they could be disappeared, sent to the gulag, confined in a psychiatric hospital, subject to intensive "state education," etc. But they still managed to pass it around and read it, and it would be literally impossible for this collection of Trumpster chucklefucks to exert even a fraction of this logistical and physical control, when every citizen already owns a laptop and a smartphone. The history books aren't going anywhere.

That all said, of course we are all hyper-alert and anxious and afraid, and we don't want to miss anything that might be important or dangerous or anything else. I get that, I completely do. But we still have to pace ourselves, we still have to apply critical thought and learn how to educate ourselves when something seems huge and scary and unstoppable, and I am attempting to do a small part of that on a niche blue hellsite that won the social media competition by literally doing nothing while its peers all fell face first into being corporate Nazis. The bar is low. But hey, I'm here, and you're here and you're reading it, and we will get through it. I promise.

Courage, etc.

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got a cool semi-vintage watch from Mum and Dad as a birthday gift -- the band is obviously not original, but the watch itself is a Soviet-made mechanical from the early 90s (we think). The real gift is that we don't have much info on the watch so I get to research it. :D

Apparently my grandfather owned a Luch watch he got from a colleague he worked with in the 60s or 70s (he worked in aerospace for the US and knew a few expats, so Mum was told) and valued it very highly. She doesn't know what happened to his so she got me one similar, if of a later make.

[ID: my wrist with a watch on it with a modern nylon band; the watch face is cream with wide black numbers. It has slim black hour and minute but no seconds hand. Text below the 12 reads Luch and text under the 6 reads "Made in Belarus". There is a winding fob on the right.]

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

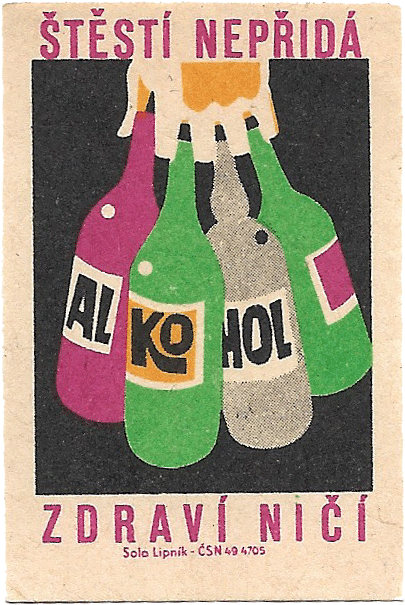

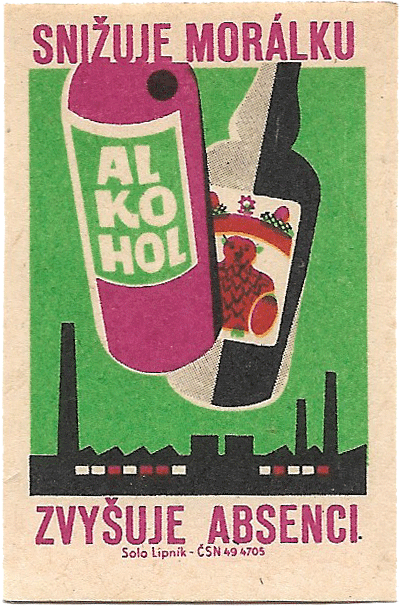

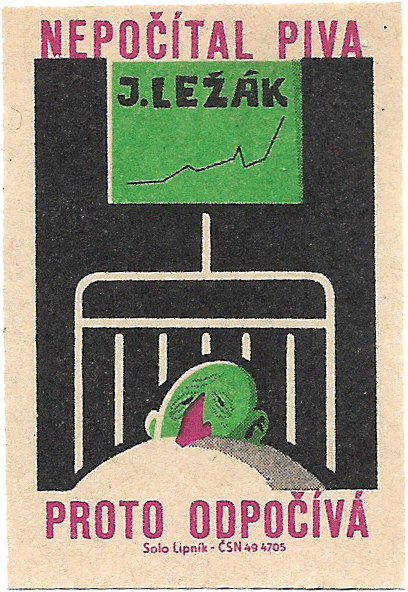

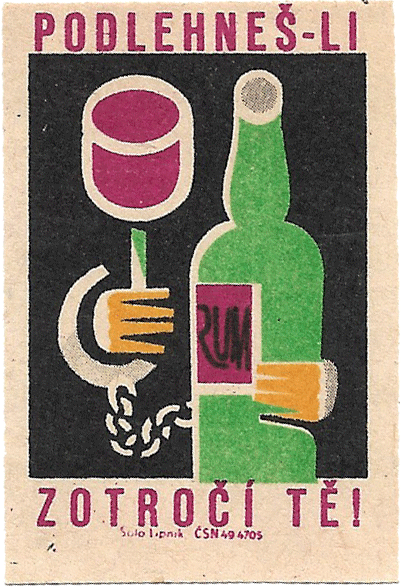

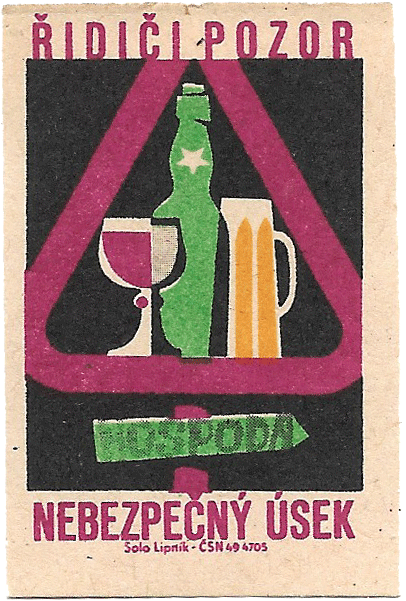

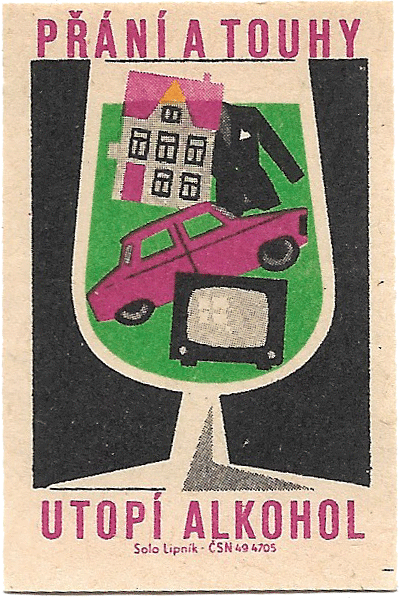

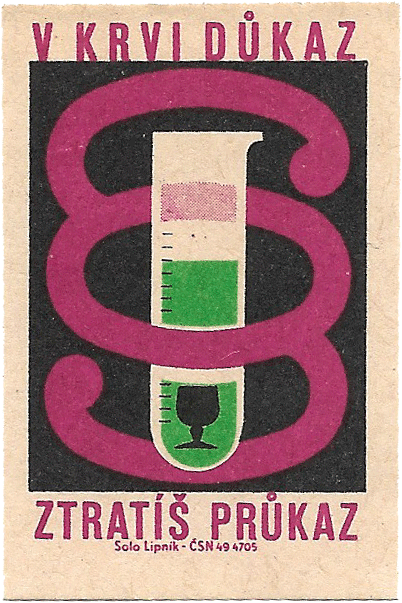

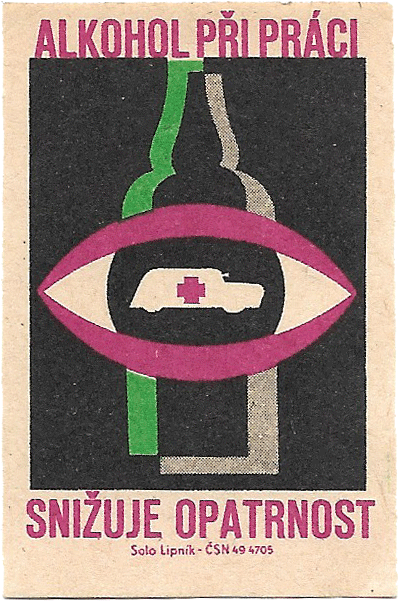

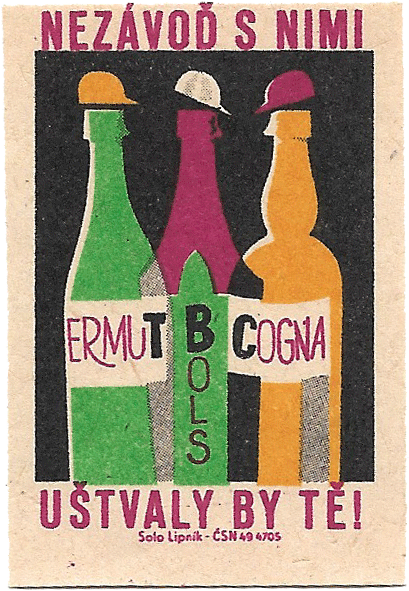

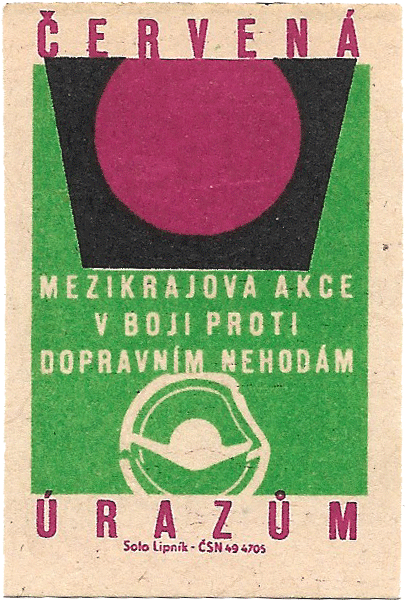

Czech matchbox labels warning of the dangers of alcohol dependence and drunk driving, printed at the Solo Lipnik match factory, 1962

"Luck does not add anyone's health"

"lowers morale, increases absence"

"He didn't count the beers, that's why he rests"

"If you submit, it enslaves you!"

"Drivers beware, dangerous area" (dangerous intersection?)

"Alcohol drowns wishes and desires"

"He stopped drinking, he's furninshing an apartment"

"If high blood proof, you will lose your ID"

"Alcohol reduces attention at work"

"Don't race them, they will ruin you!"

"Red [means] Injury" and "Intercountry action against traffic accidents"

"He who can't control himself does not belong behind the steering wheel"

#my scans#czech#aesthetic#graphic design#midcentury design#ussr#soviet history#soviet aesthetic#20th century history#PSAs#PSA#history#art#design history

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lot of the mechanisms of Soviet collapse really have no parallel in the US government or economy, just because the systems are very different. A United States analogous to the Soviet Union would be a one-party dictatorship like PRI Mexico that had been experiencing decades of stagnation since the most recent global economic shocks (perhaps like modern Britain, but even more extreme), which is more diverse on the national level but with clearer geographical groupings of ethnic minorities (and where administrative boundaries at follow the major ethnic divisions,) and where every NATO country only maintained its NATO membership because the the US was willing to roll tanks into their capital cities if they didn't maintain similar authoritarian one-party governance.

Heck, when I put it like that, it's a wonder the Soviet system managed to last as long as it did!

#us politics#soviet history#the US doesn't really have *any* political parties with the institutional capacity or organization of the CPSU

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

During 1935 and 1936 a new form of shock-work has developed in the form of “Stakhanovism.” In essence it is a very simple story. A certain coal-miner, by the name of Stakhanov, working in a pit in the Donets Basin in the Ukraine, reorganized the work of the group of which he was leader, so that output was greatly increased. His pit newspaper gave the matter publicity, it was taken up as a “scoop” by other newspapers — for the U.S.S.R. needs coal — and the rationalization proposals of Stakhanov became known throughout the world. Many managers and engineers did not approve of Stakhanovism, for two main reasons. First, they felt that the wholesale reorganization of methods of work was their job, not that of the rank-and-file miners. The Soviet Government Press, however, immediately attacked such a view, pointing out that the welfare of the U.S.S.R. depends on the maximum expression of personal initiative by all workers. Secondly, in certain cases the managers and technicians objected to workers reorganizing their methods of work, because their wages then rose considerably above those of the technical and managerial staff! This attitude was also attacked in the Press, and the Stakhanov movement has spread throughout the country. The Stakhanov movement, and the publicity and encouragement given to Stakhanov and his followers, stimulates every worker, however unskilled, to become a rationalizer, an organizer of his or her own labor. In this way every worker feels encouraged to utilize brain as well as hand. Large numbers of workers become more skilled and earn higher wages. There is a general rise in both material and cultural standards as a result. Further, the leading Stakhanov workers themselves are asked to become teachers of their methods. Stakhanov has been invited back to his native village, to use his organizing power to raise production in the collective farm. He also spends much time visiting different coal-mines, teaching the workers there how to reorganize their work for greater efficiency. A rank-and-file miner has become a technical expert and an engineer. And this is happening all the time in the Soviet Union today, affecting hundreds of thousands of workers.

Pat Sloan, Soviet Democracy, 1937

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Stalin Museum, Gori

Taken March 2025

#georgia#caucasia#soviet history#museums#tapestries#statues#my photos#my places#sptrv#(do not send me asks about stalin lol. this is a viewpoint neutral museum visit. i am a good millenial marxist)#(chris cutrone says the zoomers like stalin again now lol. which may or may not be his usual attempts at deliberate provocation idk)

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Berlin’s end

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valentin Serov | Lenin proclaims the victory of the revolution at the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets.

#Valentin Serov#Russian Art#Vladimir Lenin#Lenin#Russian Revolution#the russian revolution#soviet history#Art

328 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Left Opposition, 1927

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Er what

Not exactly antisemitism but I was running over a blog's search of what they said about apartheid (and its inevitable comparisons with Israel) and a showcase of leftist brainrot

ID:

A screenshot saying: here is probably ONE thing Soviet Russia did right and ARGUABLY BETTER than anyone else in the entire world in the past 100 years of human history: ANIMATION.

Other says:

i would say their funding and material support of antiapartheid groups in south africa is a little more important but this is tumblr so i expect nothing from you people.

https://gardengnosticator.tumblr.com/post/751884453312348160/i-would-say-their-funding-and-material-support-of

I doubt the Soviets' funding of anti-apartheid groups are as noble as those tankies think

Nobody tell OP they were funding those groups to cause a revolution in American Allied country and destabilize the region.

And OOP is objectively correct, any empire can create a puppet state, Soviet animation and film was the same 100 people over and over and they were really good at their jobs.

Soviet Animation had paper dolls and stop motion and hand painted backgrounds and is frankly the one way USSR was actually better than America in literally anything besides sending a bunch of dogs into space. Not even necessarily getting them all safely back either.

(BTW the main engineer who sent Yuri Gagarin into space was a Russian Jew. Gagarin’s second words after his famous first words ever spoken in space “It’s beautiful up here”, was to thank the man. This thank you was censored by the Soviets because they’d rather die than admit a Jewish engineer put the first man in space)

capitalist dog?! Op the Soviet Union would treat you like a dog, the ones they sent into space, so maybe watch some “Hedgehog in the fog” and shut your ignorant Western goy mouth

#Soviet antisemitism#soviet history#space race#tw referenced animal death#Soviet animation#tankie punks fuck off#leftist hypocrisy#leftist brainrot#historical revisionism

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Regarding "Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944-1956", would you say you were consciously reading it with an eye to reviewing its technical merits, ie reliable sources, and analysing them well, or was it more reading for pleasure - or indeed, are the two one and the same? Or is it something completely different to any of those?

I read it for a couple reasons, first being that I am currently focusing on Eastern European history, politics, and international relations in the new degree, and second that it is something I am genuinely interested in both on its own behalf and for present-day resonances. So I am reading it as a trained historian but also because I am interested in the subject and want to learn more, so it's not like I'm just confirming stuff that I already know. On which, a few quick points on how to read like a historian:

I admire Anne Applebaum's stuff a lot, and it has earned external acclaim: for example her previous book Gulag won the Pulitzer Prize. This is a good indication that an author has legitimate credentials and strong research about the topic at hand, and that it has been recognized by multiple international experts and prize bodies. Obviously, not every book needs to have won the Pulitzer to prove its usefulness, but it does mean that it comes from a historian who has received thorough and positive peer review on the highest level. I also recommend her book Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine.

Next, she is upfront about how she approached her sources, where she found them, and the language and access logistics. She is based in Warsaw, speaks Polish and Russian, and was able to directly translate sources in those languages; for Iron Curtain, she names her research assistants/translators in Hungarian and German and which archives they were working in. She notes that it took six years to write the book because of the necessity of consulting these far-flung document archives in different places; she has also conducted some in-person interviews. There is an extensive bibliography and direction for future reading. As well, despite the complexity of her subject, she is a very clear and easy-to-follow writer; someone who was approaching the book and knew relatively little about the regions or the major research questions would be able to follow along. I have recently read several history books where I was interested in the topic and wanted to follow along, but the writing was unnecessarily murky, unclear, or convoluted, and which made it difficult to keep up, even in those books written and published by a popular press.

Next, while she obviously wants to explore the problems of these societies and the phenomenon of totalitarian government in detail, she attempts to present both perspectives: both why these societies were initially attractive, the social and political factors of destroyed postwar Europe that enabled their implementation, and what ordinary people thought and experienced in response. While she is very clear that this was a Soviet effort based in Moscow and based on Stalinist principles, she also underlines that it was not just a situation of one-way agency where totalitarian principles were being unilaterally imposed on a hapless population without any local collaboration or support. She explores the reasons why local East German/Polish/Hungarian authorities decided to cooperate (or not cooperate) with the occupying authoritarian power, how people in each of those places did the same, and the fact that the totalitarian project was indeed made possible largely because of this collaboration (and when the collaboration was revoked, it instantly ran into major difficulties). That is an important lesson for the present day when we are looking at those organizations, corporations, and individuals that have already pre-emptively offered their support to a fascist government, and are acting in happy accordance with it.

As such, in short-ish summary, there are several ways to read a popular-press history book: for the analysis of technical/historical skills, to consider how the narrative is presented and the conclusions that are drawn, the bibliography and resources that are offered, simply because I am interested in the topic and want to learn more, and because it has important lessons for the present day. So yes.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nik & Mik!!!!

@soviet-space-ace @thespoliarium

#nikita khrushchev#anastas mikoyan#soviet union#soviet history#the Khrushchev thaw#the ice cream’s melting coz you know..#the thaw#Khrushchev#Mikoyan

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the people with hyper-fixations on the Napoleonic wars and all the people with hyperfixations on Soviet history (me) should team up and become one insufferable person

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In the first years after the Bolshevik Revolution and Russian Civil War, the population of Soviet Karelia, especially of its border areas, which were directly affected by Soviet-Finnish conflicts, could easily be influenced by reports of “Finnish danger” and felt animosity toward “white Finnish bandits.” At the same time, the closer people lived to the border, which in the 1920s remained easy to cross illegally, the easier it was for them to compare lifestyles and policies on both Finnish and Soviet sides. This comparison often was not in favor of the latter, which, to a certain degree, negated the efforts of Soviet propaganda to convince people that Finnish neighbors were their main enemy. Quite the contrary, the Karelian population increasingly tended to blame their misfortunes on the new power that, as they believed, had brought only hunger and unemployment. In this context, anti-Soviet propaganda from Finland in the early 1920s had a much stronger effect than Bolshevik agitation. This was evidenced by thousands of Karelian refugees who saw the main danger for their families not in white Finnish incursions but in the Bolsheviks in power and who sought refuge in white Finland so much hated by Soviet leaders.

When the Civil War was over, the Soviet government set a goal to “distract attention of Karelians from Finland,” which had to be implemented, in particular, by émigré Finnish Communists. The government of Edvard Gylling sent Red Finns to establish Soviet power in ethnic Karelian regions, for it believed that they would find a common language with people who barely spoke Russian easier than Bolshevik activists. Most Red Finns, however, were former industrial workers full of revolutionary enthusiasm, but hardly aware of the peculiarities of rural life, which caused additional problems when they communicated with Karelian peasants. Finnish Communist émigrés readily condemned the “white bourgeois regime” of Finland but had no means to effectively fight hunger and unemployment, so their arguments deflated; moreover, because of very poor infrastructure on the Russian side, provisions to certain remote Karelian areas could be delivered in winter and spring months only from Finland, which strengthened the sympathies of Karelians for their neighbors.

Since Red Finns were the immediate authority that represented the Bolshevik power in Karelian areas, local inhabitants started to blame them as the people responsible for their misfortunes. Economic hardships among the Karelian population resulted in images of white Finnish aggressors, which they adopted from Soviet narratives, superimposed onto Soviet Finnish leaders. Soviet security organs kept a close eye on this tendency. In its report for May 1928, the GPU of Soviet Karelia informed the Soviet government that

there is widespread antagonistic sentiment among the Karelian population toward Finns, which is caused, on the one hand, by the introduction of school teaching in Finnish and, on the other hand, by a large number of Finns in the central administrative bodies of Karelia. This also leads to talks of a possible incorporation of Karelia into Finland: “Finns are at the head of our government, Finnish is taught in schools, and what if we will be annexed by Finland?” Kulaks and the well-to-do element of the Karelian population try to intensify this sentiment using agitation: “While we have Finns at power, we will live poor, because they issue wrong laws,” and in a number of cases they claimed: “We should create our own organization and expel all Finns from the government.”

However, anti-Finnish feelings among the local population were seldom addressed to the Karelian government. Instead, their grievances were aimed first at local officials and managers, who were always in the public eye. People were dissatisfied with the current state of affairs in management: “Why [do] Finns keep on occupying leading positions in the [state timber trust] Karelles, while Karelians are not allowed to them?” Such sentiments were sometimes generalized to the entire Finnish leadership of Soviet Karelia, and this was perceived by Soviet authorities as a real threat.

Some Karelian returnees who fled to Finland during the Civil War, for example, argued that in Finland they were treated much better than back home, where “[Red] Finns control everything and life is miserable,” and they called for the “expulsion of red scoundrels from Karelia.” Similar complaints were made by workers of factories in which the top management consisted of Finns: complaints included wage discrimination of Russians compared with Finns and Karelians as well as the reserve and self-restraint of Finns and their tendency to keep their distance from others, to “stick to their nationality.” Workers of the Kondopoga pulp and paper plant complained that “there are two classes in Karelia: exploiting Finns and exploited Russians and Karelians, [and] this should be eliminated before it is too late.”

This confrontation between Red Finns and the local population embodied, in fact, a much larger conflict between Soviet authorities and this population. Similar antagonism could be observed in places and organizations where Karelians, Russians, or Jews occupied authoritative positions. Inhabitants of northern Karelia were reported to say that “there was one revolution in Karelia, but we will have to make a second one, for too many Russian administrators came to us,” while workers of a lumber mill in Medvezhyegorsk complained of a “Jewish stranglehold” because “managerial positions were all occupied by Jews.”

Thus, by the late 1920s, the image of Finland and Finns formed in Karelian society was quite discrepant. Bourgeois Finland and its revolutionary proletariat, which “suffered under the yoke of white terror,” as newspapers wrote, were somewhere far away, while Red Finns were nearby, and among the local population they were perceived as “masters” (khoziaeva) dreaming of taking over their native land or sometimes even as a “fifth column”: “Now, under Soviet power, there are many Finns working as Soviet bureaucrats, but if a war breaks out they would betray, as [Russian] Germans betrayed in old times under Nicolas [II].” During the 1920s, this image of an internal alien clearly dominated images of hostile Finnish bourgeoisie and friendly Finnish proletariat imposed by Soviet propaganda.

To make things even more complicated, the Finnish influence on Karelian territories was still strong in the 1920s, and idealized memories of prerevolutionary life accentuated current economic hardships and provoked accusations: “If we had been annexed to Finland, we would have lived much better. If Finns hadn’t given away Karelia in 1920, we would have lived like barons.” At the end of the 1920s, the population of border regions listened almost exclusively to Finnish radio stations, which, as Soviet party documents worrisomely noted, would have a negative impact on “politically undeveloped listeners.”"

- Alexey Golubev and Irina Takala, The Search for a Socialist El Dorado: Finnish Immigration from the United States and Canada to Soviet Karelia in the 1930s (Lansing: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), p. 111-112.

#soviet karelia#karelia#finnish civil war#red finns#soviet union#soviet history#soviet communism#communists#karelians#finnish immigration to the soviet union#karelia fever#academic quote#reading 2024

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

If citizens are to participate effectively in running the country in which they dwell, they must have an appropriate education. Therefore, even in the elementary school in the Soviet Union the visitor is struck by the extent to which the student is treated as a citizen. Corporal punishment is forbidden by law in the Soviet schools, and other punishment in any form is practically non-existent. The children are taught to look upon the teachers, not as vested with an almost supernatural authority, but as human beings like themselves, who have more experience. The headmaster or headmistress of a Soviet school is a senior comrade, who holds a position of such authority only by virtue of ability and good leadership. Everything possible is done in the Soviet schools to bring the children into contact with the everyday life of the country. Their lessons include knowledge of current political questions and of industry and agriculture. In their spare time, facilities are provided in the schools and other institutions for hobbies such as natural history or engineering, literature or sport. The important fact in this connection is that the Soviet child is encouraged to take his hobbies seriously, and is given the possibility of doing useful work which may have positive value. Thus, groups of “Young Inventors” attached to Soviet schools, turn out some hundreds of inventions annually. And in the Moscow Zoo a group of child helpers participates in the research work that is being carried on there. And once, on May and, a public holiday, the direction of traffic in the city of Kiev was in the hands of the children of the city. And the children in all the larger towns have their own theaters and cinemas, run by the Commissariat of Education in conjunction with the local school authorities. At the children’s theaters the children are expected not only to be spectators but to criticize the performances and to make suggestions for their improvement. The Moscow children’s theaters arrange meetings between children and writers, at which writers read their latest children’s stories, and discuss their merits with the children prior to publication. The children learn to play a part in determining the kind of books that are going to be published for them. These examples, taken at random from the life of Soviet children today, serve to emphasize the fact that the Soviet child is a citizen from his earliest days, receiving the respect of other citizens, and with the opportunity to utilize his or her spare time in some useful hobby which may be of actual scientific or artistic value.

Pat Sloan, Soviet Democracy, 1937

#communism#socialism#leftism#anti capitalism#marxism#soviet union#ussr#history#ussr history#soviet history

111 notes

·

View notes