#Shinobu Orikuchi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Shinobu Orikuchi (Chōkū Shaku) (deceased)

Gender: Male

Sexuality: Gay

DOB: 11 February 1887

RIP: 3 September 1953

Ethnicity: Japanese

Occupation: Ethnologist, linguist, folklorist, novelist, poet, teacher, scholar

#Shinobu Orikuchi#Choku Shaku#lgbt history#lgbt#qpoc#male#gay#1887#rip#historical#japanese#asian#poc#linguist#academic#scholar#poet#writer#teacher

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

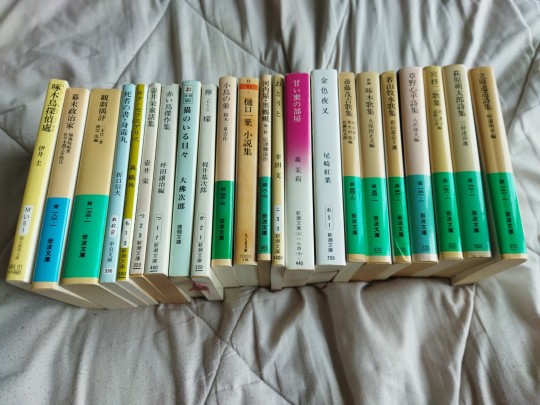

Final book haul of the year, I am broke.

List (left to right):

Woodpecker Detective's Office by Ii Kei

Politicians of the Bakumatsu Era by Fukuchi Ōchi

Criticism of Theatre by Miki Takeji (Mori Ōgai's little brother)

Book of the Dead by Orikuchi Shinobu

Vita Sexualis by Mori Ōgai

Tsuboi Sakae's book of Fairy Tales by Tsuboi Sakae

Akai Tori Collection by Various Authors

A Day with Cats by Osaragi Jirō

Lemon by Kajii Motojirō

The Bird's Nest by Suzuki Miekichi

Higuchi Ichiyō Novel Collection by Higuchi Ichiyō

The Black Lizard by Hirotsu Ryūrō

Otōto by Kōda Aya

A Room of Sweet Honey by Mori Mari

The Golden Demon by Ozaki Kōyō

Saitō Mokichi's Poetry Collection by Saitō Mokichi

Takuboku's Poetry Collection by Ishikawa Takuboku

Wakayama Bokusui's Poetry Collection by Wakayama Bokusui

Kusano Shinpei's Poetry Collection by Kusano Shinpei

Miya Shūji's Poetry Collection by Miya Shūji

Hagiwara Sakutarō's Poetry Collection by Hagiwara Sakutarō

Tachihara Michizō's Poetry Collection by Tachihara Michizō

#japanese literature#books#orikuchi shinobu#mori ougai#osaragi jirou#motojirou kajii#ochi fukuchi#higuchi ichiyo#hirotsu ryuurou#kouda aya#mori mari#ozaki kouyou#ishikawa takuboku#hagiwara sakutarou#kusano shinpei#michizo tachihara

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

(I don't normally diary post, but work was so slow yesterday and I thought maybe my JUNE thoughts would interest someone.)

Today the kids are taking exams so I have literally nothing to do at work. I'm not sure I can read for the next 7 hours without wanting to kill myself eventually. This job can be actual torture sometimes. You know a lot of Japanese public schools don't have Wifi you can connect to? A part of me wonders if I should pretend I'm sick or something so I can leave early, but I think that might be all too transparent. I wish I could surf the web or something. Not even the slowest day at the museum I worked at in college could have prepared me for this. I have to wonder why they'd make me come to this specific school on a day where there is literally nothing for me to do. Who the fuck made this schedule?! At least JUNE magazine is pretty entertaining. I don't think the prose are hard to read really, my biggest issue is the unfamiliar kanji. I suspect most of the kanji I'm coming across is pretty literary? At least in this specific story. My dad would get a real kick out of it. A short story called "Death in Kuruizawa," in a literary magazine that also publishes speculative essays about rock musicians being bisexual and lamenting that Lou Reed got married… It's not exactly funny, but it is amusing. I wish something like it still existed now, but magazines are obsolete.

I'm no expert on JUNE magazine, and can't speak on its evolution given that my actual experience with it is pretty limited, but there is this insular feeling about those early issues. It really feels like a special nook for the freak, pervert women of the late 70's and 80's. This was like 20 years before the term "fujoshi" became a thing, these women were simply "tanbi-kei" enthusiasts or literature fiends. Really enjoyed this short essay I read where this lady talks about spending the whole day running around Tokyo trying to find a compilation of Orikuchi Shinobu's work that contained his short story "Kuchibue" only to realize that she would have found much more success if she had just gone to her local library. But I totally get her, consciously or unconsciously there is this thrill about the hunt for obscure pieces of media. It's much more fun to discover something than to find it easily, if that makes any sense. While visiting Portland this summer, I came across this tiny Japanese import store that had the fucking Kaze to Ki no Uta and Hensoukyoku image albums. I mean, I wasn't even purposefully seeking them out, but doesn't it feel good to know the true value of something that's very likely overlooked?

Anyway, as slow as my work day is, I have my kindred fujo spirits keeping me company in my JUNE scans. I'm sure none of them could imagine that someone like me would be lapping this shit up the way they were when it was just coming out. And that makes me smile.

UPDATE: I may suffer brain death if I keep reading like this.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Laziness is such an ugly word. I prefer selective participation.”

Indie Multifandom Multimuse written by Luci

••• SITE ••• sibylsource •••

••• Birthdays •••

12/10 Emily

12/23 Ayatsuji

12/29 Kitamura

••• MUSE LIST •••

•••••••••••••••••

• BUNGO STRAY DOGS •

Ayatsuji Yukito

Yumeno Kyusaku

Itou Sachio

Kitamura Tokoku

Kawabata Yasunari

Niimi Nankichi

Orikuchi Shinobu

Emily Dickinson

• TALES OF SERIES •

Sync the Tempest

Arietta the wild

Rook

Iah Cereus

• TOILET BOUND HANAKO •

Mitsuba Sousuke

• THE DEVIL IS A PART-TIMER •

Lucifer

(Most muses have a Star rail verse. )

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another BSD oc! Orikuchi Shinobu and (Mimi)mo No Toji- 23 The Mafia's Eyes

Ability: The Book of the Dead

Mimimo No Toji, or Mimi-chan, is Shinobu's ability. When his ability, The Book of the Dead is active, Shinobu loses his own consciousness and instead sees through the eyes of Mimi-chan. Mimi-chan is a ghost with no combat skills due to it, she can only phase through walls and can possess people for a small amount of time. They have a distance limit of 30 metres and the connection between them can become cut if the host of Mimi-chan's possession is killed.

Shinobu can only share contact with her for up to 10 minutes before he starts to have headaches, nosebleeds and will often end up passing out.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doodle of Shinobu Orikuchi

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1: An Alternative Approach to the History of Shinto

Conceptualizing Shrine Practice as Shinto

...at a time of deep crisis when it was far from obvious that Shinto would survive the demise of the old imperial Japan. All agree that if Shinto was to be rescued from rapid disintegration, it need to be reinvented. Yet the direction that Shinto would take after Japan's catastrophic defeat in the war was far from clear... Since 1868 shrine ritual had been a matter of political importance to the Japanese state... The allied powers that occupied Japan in September 1945 saw Shinto as the ideological foundation of Japanese "emperor worship" and aggressive expansionism. They moved quickly to remove its influence from the public sphere by drastic measures... Budgets were nonexistent, and many of the leaders of the old Shinto establishment were being purged from public life. Nor was it easy to find sympathy among the general public... most Japanese felt a profound aversion to the propaganda they had been bombarded with for over a decade, and shrines suffered for their long-standing association with that propaganda.

—Pages 5-6

"Among the debaters, [of what Shinto should represent after WW2] we can discern three main camps. The first lead by Ashizu Uzuhiko (1909-92) stressed Shinto's role in uniting the Japanese people under the spiritual guidance of the emperor. The second drawing on the work of the ethnologist Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962), rejected the idea that centralist imperial ideology was at the core of Shinto. Instead, this group stressed the spiritual value of local traditions of worshiping local Kami, in all their centrifugal variety. The third fronted by Orikuchi Shinobu (1887-1953) argued that if Shinto was to survive, it should be developed from an ethnic religion into a universal one... Ashizu was an imperial loyalist and activist who saw Shinto in a political context... Within [Jinja Honchō], Ashizu fought a hard battle to exclude the influence of Yanagita and Orikuchi from the new shrine organization. He feared that their emphasis on regional diversity would tear apart Japan's sense of national unity, and even suspected that their views were being used in a leftist conspiracy to destroy the nation."

—Pages 6-7

Shinto has never been a monolith, I wish people would stop assuming Emperor worship is the basis of Shinto, and I wish people would stop assuming all people historically wanted it.

Meiji and the Formation of Shinto as a State Cult

This [Jingikan, or Council of Kami Affairs] Council was put in nominal charge of all shrines. In the ensuing weeks shrines were methodically separated from Buddhism. Buddhist priests, deities, buildings, and rituals were banned from all shrines. In the words of Allan Grapard (1984: 245), the Meiji government 'forced thousands of monks and nuns to return to lay life and watched without moving when innumerable statues, paintings, scriptures, ritual implements and buildings were destroyed, sold, stolen, burnt or covered with excrement.' It was at this time that Shinto became physically and institutionally distinct from Buddhism.

—Page 8

Another factor behind the Meiji institutionalization of Shinto was an azure sense of crisis in the face of Western expansionism. It was feared that Christianity would gain a foothold in Japan, with devastating effects in the nation's cohesion and, ultimately, its chance of survival... In effect, the new Meiji cult of shrines functions as a form of Confucian-inspired ancestry worship. By honoring the ancestors of the nations, a communication was created that celebrated a shared past. To this end, shrines were redefined as places that commemorates heroes of the state. The centerpiece of the new shrine system was Ise, the shrine of the imperial ancestor, and sun goddess Amaterasu.

—Pages 8-9

Shinto thinkers disagreed in even the most fundamental questions. Which kami should be incorporated into the imperial cult? What is their relation to each other? What do the classical texts teach about life and death, good and evil, reward and punishment? No consensus could be reached on any of these central questions, and under these circumstances and effective missionary campaign was impossible.

—Page 9

One of the good things about Shinto historically and today not having a holy book or clear scriptures is that it did help fuck over the government’s attempts at fully using it for religious indoctrination.

Pre-Meiji shrines that survived all reforms were often redesigned and given a new identity: a new name, or even a new set of kami taken from the imperial classics. As ancient priestly lineages disappeared, local traditions were lost and exchanged for standardized procedures drawn up in Tokyo.

—Page 12

So much knowledge was lost due to this eradication of practices and that is absolutely heartbreaking

1 note

·

View note

Text

La luna brillaba como antes. Las montañas se arriscaban y había pocos lugares donde la luz pudiera posarse. Rielaba en los valles, y los haces restantes rebotaban al cielo, refractando en recovecos y quiebras.

Muy cerca estaban la cimas de Sawayama. Parecían denegridas, como entreveradas, más enmarañadas cuanto más ahondaban sus sinuosidades. Había áreas que relucían entre el velo de niebla sutil que se posó al anochecer. Trasfundida de luna, la noche emanaba tersura y calidez.

Más allá de las apiñadas colinas había un cauce cuya arena blanca refulgía. Era el río Ishi, como una faja desplegada, salpicada de luz. Al norte y sur de ésta cruzaba una franja luminosa que en su confín boreal parecía achatarse de pronto, probablemente junto a la aldea de Ōshikōchi. Allí, justo en la boca de la sierra, era donde el río Katashio —que ahora nombramos Yamato— se vierte en la llanura. Al noroeste, aquellos lisos reflejos ensartados tenían que ser las ensenadas de Kusakae, Nagase, Naniwa.

La noche era serena. La faz de la montaña a la hora que canta el gallo era apacible, como rociada de relente, aquietándolo todo en derredor. A sus pies prendían por todo el valle pequeños ampos: tardíos cerezos en flor que salpicaban la vega de Yamada.

Una única carretera corría recta, descendiendo abruptamente entre las cumbres esposadas del Futakami. Era la vieja ruta de Naniwa a la antigua capital de Asuka que, dependiendo de la jornada, podía estar abarrotada a mediodía. La carretera era ancha y resplandecía blanca —de noche semejaba una sierpe de grama—, a horcajadas entre ambos picos. Desde allí se despeñaba y luego, desparramándose, se allanaba casi. En aquel punto se erguía un soto de cipreses de ramos apuntados. Se tenían firmes allí desde hacía más de medio siglo, formando un apretado manchón. Bajo la luna y a la sombra de los árboles derramados por la falda del otero, se levantaba un túmulo. La luna lucía sin guiñar, las cimas superpuestas entornaban los párpados.

Aquí... aquí... aquí...

Quizá fuera una voz, pero tan tenue que incluso oídos hechos al silencio más absoluto apenas habrían logrado distinguirla. Aquellos dejes no parecían extraños ni chocantes allí.

Aquí... aquí... aquí...

Sin duda era una voz humana. El canto nocturno de un pájaro conjuró otro eco. Luego todo calló un momento. El silencio ahondó, expandiéndose al máximo en la claridad.

Las picos marcaban uno tras otro, hacia el sur, los artejos del serrijón, cada vez más encumbrados: Fushigoe, Kushira, Kogose... hasta que el último parecía traspasar el mismo vacío celeste. Era el Futakami, cuyo negro bulto se cernía sobre el túmulo.

Bajando por la carretera de Tagima aparecieron lo que en principio parecían sombras. Dos, tres, cinco... luego ocho, nueve. Las sombras de nueve hombres. Bajaban precipitadamente por la pina cuesta en dirección a Kawachi.

Más que nueve hombres parecían nueve deidades sintoístas. Todos vestidos de blanco, con indumentaria de viaje, desde el tocado hasta las manos y los pies. Al desembocar en el llano, se detuvieron ante el soto.

Aquí... aquí... aquí...

El sonido no parecía proferirlo una persona; las palabras flotaban efímeras, sólo un instante. Atónitos al pensar que el espíritu de la montaña les respondía, alzaron sus voces al unísono. Pero tras aquella repentina exclamación el monte volvió a su silencio cerrado.

—¡Aquí!... ¡aquí!... Te invocamos, alma de la doncella del clan meridional de los Fujiwara. No has de vagar en lo hondo del monte. ¡Torna veloz a tu cuerpo! ¡Ven! ¡Ven! ¡Hemos estado buscando sin parar tu alma entre estas cimas! ¡Aquí! ¡Aquí!

Los nueve ministros se transfiguraron en dioses. Dejaron sus báculos en tierra y deshicieron sus tocados, que en aquella ocasión no se componían más que de albas ínfulas. Las desenvolvieron en toda su extensión y luego los nueve encararon el túmulo.

—¡Aquí!... ¡aquí!...

Repitiendo la invocación sintieron la natural pesadumbre del ánimo y la fatiga corporal, que devolvieron sus espíritus a la común humanidad. Sin apartar la vista, fueron ciñéndose de nuevo a la cabeza las bandas blancas y recogiendo sus cayados quedaron allí de pie como simples viandantes.

—Hasta aquí alcanza nuestra obra silenciosa...

Las restantes ocho voces asintieron a una, como si lo tuvieran ensayado, echándose a tierra a descansar tirando a un lado sus cayados.

—Ésta es la linde entre Yamato y Kawachi. Ya hemos cumplido el rito de invocación de las almas. El cuerpo de la noble doncella que yace en la ermita habrá recuperado su alma. Debe encontrase animada ya.

Orikuchi Shinobu

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is the situation regarding the Nox and Numen cleared up to any capacity in the original texts?

Their relation to each other is still a mystery.

If you are interested, there is a fun fanct about Numen. In Japanese they are called "marebito" 稀人 - "rare person".

Translated, the title means “The Stranger From Afar.” Orikuchi Shinobu defined marebito as spiritual entities that periodically visit village communities from the other world — the “everlasting world” (tokoyo) across the sea — to bring their residents happiness and good fortune.

I would recommend do not take the mythological origin of "marebito" literally, but I think that implied connection to the spirits is rather interesting. On the other hand, in EN it's reference for Tolkien works, which is also intriguing, considering the history of Numenor.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading 2020

6-January-2020: Beaumont, Matthew, Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London (2015, England)

9-January-2020: Otsuka, Julie, When the Emperor was Divine (2002, USA)

12-January-2020: Lehmann, John, In a Purely Pagan Sense (1976, England)

12-January-2020: Modiano, Patrick, Little Jewel (2001, France)

19-January-2020: Dickens, Charles, Hard Times (1854, England)

20-January-2020: Didion, Joan, The Year of Magical Thinking (2005, USA)

28-January-2020: Hunt, Laird, In the House in the Dark of the Woods (2018, USA)

2-February-2020: Hardy, Thomas, Under the Greenwood Tree (1872, England)

5-February-2020: Lehman, David, One Hundred Autobiographies: A Memoir (2019, USA)

15-February-2020: Oshinsky, David M., “Worse Than Slavery”: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow (1996, USA)

17-February-2020: Zola, Émile, His Excellency Eugène Rougon (1876, France)

22-February-2020: King, Dean, Skeletons on the Zahara: A True Story of Survival (2004, USA)

29-February-2020: Graves, Robert, They Hanged My Saintly Billy (1957, England)

8-March-2020: Wyndham, John, The Day of the Triffids (1951, England)

14-March-2020: Ginsberg, Allen, South American Journals (1960, USA)

29-March-2020: Mantel, Hilary, Wolf Hall (2009, England)

5-April-2020: Butler, Octavia, Parable of the Sower (1993, USA)

12-April-2020: Butler, Octavia, Parable of the Talents (1998, USA)

15-April-2020: O’Brien, Glenn (ed), The Cool School: Writing from America’s Hip Underground (2013, USA)

16-April-2020: Moravia, Alberto, Agostino (1943, Italy)

19-April-2020: Ross, Lillian, Picture (1952, USA)

25-April-2020: Carson, Rachel, Silent Spring (1962, USA)

3-May-2020: Mantel, Hilary, Bring Up the Bodies (2012, England)

6-May-2020: Duras, Marguerite, The Lover (1984, France)

10-May-2020: Ma, Ling, Severance (2018, USA)

14-May-2020: Hale, Grace Elizabeth, Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture (2020, USA)

17-May-2020: Kadare, Ismael, The Traitor’s Niche (1978, Albania)

20-May-2020: Saikaku, Ihara, Comrade Loves of the Samurai (Anthology) (1687, Japan)

14-June-2020: Mantel, Hilary, The Mirror and the Light (2020, England)

20-June-2020: Ballard, J. G., The Kindness of Women (1991, England)

25-June-2020: Orikuchi, Shinobu, The Book of the Dead (1943, Japan)

27–June-2020: Jefferson, Margot, Negroland: A Memoir (2015, USA)

30-June-2020: Douglass, Frederick, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845, USA)

5-July-2020: Ellison, Ralph, Invisible Man (1952, USA)

6-July-2020: LeCarré, John, Call for the Dead (1961, England)

11-July-2020: LeCarré, John, A Murder of Quality (1962, England)

14-July-2020: LeCarré, John, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963, England)

18-July-2020: LeCarré, John, The Looking Glass War (1965, England)

24-July-2020: LeCarré, John, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974, England)

1-August-2020: LeCarré, John, The Honourable Schoolboy (1977, England)

7-August-2020: LeCarré, John, Smiley’s People (1979, England)

10-August-2020: Pendarvis, Jack, Cigarette Lighter (Object Lessons) (2016, USA)

14-August-2020: Greenwell, Garth, Cleanness (2020, USA)

29-August-2020: Perlstein, Rick, Reaganland: America’s Right Turn, 1976-1980 (2020, USA)

4-September-2020: Burnside, John, A Lie About My Father (2006, Scotland)

6-September-2020: Massini, Stefano, The Lehman Trilogy (2016, Italy)

7-September-2020: Tevis, Walter, The Man Who Fell to Earth (1963, USA)

9-September-2020: Thompson, Kara, Blanket (Object Lessons) (2019, USA)

11-September-2020: Howard, Jennifer, Clutter: An Untidy History (2020, USA)

15-September-2020: Tuan, Yi-Fu, Landscapes of Fear (1979, USA)

29-September-2020: Balzac, Honore, Lost Illusions (1843, France) (reread)

7-October-2020: Bowen, Elizabeth, Eva Trout (1969, Ireland)

14-October-2020: Gary, Romain, The Company of Men (1949, France)

24-October-2020: Brontë, Charlotte, Villette (1853, England)

24-October-2020: De Lillo, Don, The Silence (2020, USA)

30-October-2020: Krúdy, Gyula, The Adventures of Sindbad (1917, Hungary)

3-November-2020: Kehlmann, Daniel, Tyll (2017, Germany)

8-November-2020: Undset, Sigrid, Olav Audunssøn, Vol 1: Vows (1925, Norway)

15-November-2020: Pullman, Philip, The Secret Commonwealth (2019, England)

23-November-2020: Baker, Nicholson, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act (2020, USA)

27-November-2020: Kempowski, Walter, All for Nothing (2006, Germany)

29-November-2020: Ainsworth, William Harrison, Auriol (1844, England)

29-November-2020: Modiano, Patrick, Pedigree (2005, France)

1-December-2020: Liming, Sheila, Office (Object Lessons) (2020, USA)

13-December-2020: Baker, J.A., The Peregrine (1967, England)

18-December-2020: Allain, Marcel and Pierre Souvestre, Fantômas (1911, France)

23-December 2020: Szerb, Antal, The Queen’s Necklace (1942, Hungary)

23-December-2020: Leys, Simon, The Death of Napoleon (1986, Australia)

25-December-2020: MacLeod, Alistair, No Great Mischeif (2000, Canada)

27-December-2020: Chateaubriand, François-Rene, Memoirs from Beyond the Grave (1846, France)

29-December-2020: Anonymous, The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes: His Fortunes and Adversities (1554, Spain)

30-December-2020: Stifter, Adalbert, Rock Crystal (1846, Austria)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hanamatsuri at Nakashitara 2018

The audience have a roll,too

In this festival we can see a Sakaki-oni striking the audience with a tree in his hands(see 3rd photo). The another name of Hanamatsuri is 'Akutai Matsuri 悪態祭り' .That is, 'Festival of speaking ill of dancers' . In Shitara area, Aichi pref, from November to January many villages have Hanamatsuri festival. They hold those festivals one after another. So they have a chance to visit other village's Hanamatsuri . At that time visitors used to be incisive reviewers. They criticised dancers loudly. Today's Japanese people may think of this behavior as rude. But in old days people took it for granted. Orikuchi Shinobu, one of a founder of Japanese folk study, said those visitors from outer village had their own role, a role as evil spirits. Our ancestors believed evil spirits always try to get out from under ground and harm our lives. So very strong god to defeat them was needed. It was Sakaki-oni. In Hanamatsuri noisy visitors had a role to express those evil spirits. In this way, in the festival site people were able to see the fight between god and evil spirits. I think what I saw at Hanamatsuri in Nakashitara can be explained by the same logic. God fights against evil spirits with a tree in his hands.

花祭りは、一名を「悪態祭り」と言います。花祭りは11月から翌1月にかけて各集落で行われるのですが、そのため、自分たちの村以外のところの花祭りを見に行くことも、ごく一般的に行われていました。そして、そういった外来の観衆は、辛口の論評を、舞っている者に投げつけたのです。ただ、このような悪態は無礼な行いとはされていなかったようです。折口信夫によると、そのような観客も、役割を持った演者として祭りに組み込まれていたのだといいます。地の底には悪霊がおり、人の世を犯そうと常に企てていた。それを退治するのが榊鬼です。今目の前で悪態をついている他集落のお客は悪霊で、それを退治するドラマが、祭りの場で演ぜられるわけです。

中設楽の花祭りでは、榊鬼が榊の木を手にもって観客を打つという場面があります。これはほかの花祭りでは見られない演出ですが、「悪霊を退治する榊鬼」という図式の中で考えることができるように思います。

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

https://youtu.be/t7q7M2AdC_Y

#mywork

I think there are also places where translation is wrong. Forgive me

Marebito is a term in Orikuchiism that refers to a spiritual or deity-like being who visits from the afterworld at a specified time.

It was defined as "a strange land" where you are given a fortune, knowledge, a life, a long life, and eternal youth and immortality by a visit of marebito (a god which gives people his blessing and leaves)

A term of the Origuchi study spiritually or to define the essential existence of God that Marebito (rare person, guest) determine time and visit from the death. It is one of the most important key concepts and is made much of in folklore as a clue to investigate Japanese faith, death idea in thinking about a thought system of Shinobu Orikuchi.

The manners and customs to offer the lodgings and a meal to the visitor (stranger, Marebito) from the outside, and to welcome are seen universally in each place. The reason is economical, and a eugenic thing is included, but is said to be it when "Marebito faith" to assume a stranger God from spirit world in the root of these manners and customs exists.

The designation of "Marebito" was shown in 1929 by (1929), Shinobu Orikuchi of the folklorist. It was God and a synonym, and, as for him, "Marebito" Rare people" called "guests"and , it originally estimated that God visited it from the far-off land from folklore and a description of the Kojiki and Nihonshoki to exist in "guests". The Origuchi of Marebito theory fixes the form by "the third outbreak of the Japanese literature". According to the right article, a field work in Okinawa seemed to be the opportunity of the idea of the Marebito concept.

Because the everlastingness was the country to live, and to be granted of the departed soul, and it was thought that the ancestor who protected people from a demon lived there, ancestor's soul came over to agriculture villagers regularly every year from the land of immortal life and came to have faith to bless people. It is said that I came to be called " Marebito " because the presence was rare. It is said that deep relations with the Marebito faith are estimated as for the tray event considered to be a Buddhism event now.

Marebito God received a warm reception in a site of a religious service, but travelers to visit will be treated before long as " Marebito " by the outside. It is a youth of the villages where I attached a mask to that play the part of God coming over, or it is written down to "Manyoshu tanka collection" Eastern verse and "the Hitachi country topographical record" by the night of the festival, the outside that it was a traveler. Furthermore, because a person of entertainment of "Hokaibito" (beggar) and the sink came to be treated as " Marebito " when I fell in the times, and a warm reception for it at the same level as God was done, I enabled the existence of the play Buddhist ascetic, and it was with a faith basis to lay a young hero's adventure story (narration type that the person of the blood relationship that is KIsyuryuuritan for a trip of the wandering and overcomes a trial through hardship).

In the case of festivals to invite visit God of Marebito

God to, it was told the spirit-dwelling object of a columnar object (mustache basket, festival car) put up to descend.

It is said that the forthcoming place changed with the distance (equal to Nenaikanai of Okinawa) of the sea, the thing which I influence the mountain worship later, and come from the sky on a mountain (descendant of the Sun-Goddess advent).

I knew the actual situation of "the Marebito faith" in Japan by Masao Oka of the friend, and Alexander Slawik which was an Austrian ethnologist did a legend and manners and customs and the comparative study of "the holy visitor" in the Germanic people and Celtic people.

まれびと、マレビト(稀人・客人)は、時を定めて他界から来訪する霊的もしくは神の本質的存在を定義する折口学の用語。折口信夫の思想体系を考える上でもっとも重要な鍵概念の一つであり、日本人の信仰・他界観念を探るための手がかりとして民俗学上重視される。

概要

外部からの来訪者(異人、まれびと)に宿舎や食事を提供して歓待する風習は、各地で普遍的にみられる。その理由は経済的、優生学的なものが含まれるが、この風習の根底に異人を異界からの神とする「まれびと信仰」が存在するといわれる。

「まれびと」の称は1929年(昭和4年)、民俗学者の折口信夫によって提示された。彼は「客人」を「まれびと」と訓じて、それが本来、神と同義語であり、その神は常世の国から来訪することなどを現存する民間伝承や記紀の記述から推定した。折口のまれびと論は「国文学の発生〈第三稿〉」(『古代研究』所収)によってそのかたちをととのえる。右論文によれば、沖縄におけるフィールド・ワークが、まれびと概念の発想の契機となったらしい。

常世とは死霊の住み賜う国であり、そこには人々を悪霊から護ってくれる祖先が住むと考えられていたので、農村の住民達は、毎年定期的に常世から祖霊がやってきて、人々を祝福してくれるという信仰を持つに至った。その来臨が稀であったので「まれびと」と呼ばれるようになったという。現在では仏教行事とされている盆行事も、このまれびと信仰との深い関係��推定されるという。

まれびと神は祭場で歓待を受けたが、やがて外部から来訪する旅人達も「まれびと」として扱われることになった。『万葉集』東歌や『常陸国風土記』に��祭の夜、外部からやってくる神に扮するのは、仮面をつけた村の若者か旅人であったことが記されている。さらに時代を降ると「ほかいびと(乞食)」や流しの芸能者までが「まれびと」として扱われるようになり、それに対して神様並の歓待がなされたことから、遊行者の存在を可能にし、貴種流離譚(尊貴な血筋の人が漂泊の旅に出て、辛苦を乗り越え試練に打ち克つという説話類型)を生む信仰母胎となった。

来訪神のまれびとは神を迎える祭などの際に、立てられた柱状の物体(髯籠・山車など)の依り代に降臨するとされた。その来たる所は海の彼方(沖縄のニライカナイに当たる)、後に山岳信仰も影響し山の上・天から来る(天孫降臨)ものと移り変わったという。

オーストリアの民族学者であるアレクサンダー・スラヴィクは、友人の岡正雄により日本における「まれびと信仰」の実態を知り、ゲルマン民族やケルト民族における「神聖なる来訪者」の伝説や風習と比較研究した。ウィキペディアより

0 notes

Text

The Book of the Dead

The Book of the Dead

By Eleanor Chandler First published in 1939 and extensively revised in 1943, The Book of the Dead, loosely inspired by the tale of Isis and Osiris from ancient Egypt, is a sweeping historical romance that tells a gothic tale of love between a noblewoman and a ghost in eighth century Japan. Its author, Orikuchi Shinobu, was a well-received novelist, distinguished poet, and an esteemed scholar. He…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Quick Orikuchi Shinobu Painting

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

¿Dónde está el niño que vuela esa cometa...? En el cielo vacío de Nochevieja restallando allá sola.

どこの子のあぐらむ凧ぞ。大みそか むなしき空の ただ中に鳴る

Se apaga el toque de Nochevieja. En el silencio sólo una voz resuena: la mía, irritada.

除夜の鐘つきをさめたり。 静かなる世間にひとり 我が怒る声

Tras largo día de estar siempre callado sin desahogo, entrada ya la noche comienzo a hablar solo.

長き日の黙の久しさ 堪へ来つつ、このさ夜なかに、 一人のも言ふ

Aguas adentro, la faz de mi ser vano clara me mira. ¿Aun la vida futura será de soledad?

水底に、うつそみの面わ 沈透き見ゆ。来む世も、我の 寂しくあらむ

Flores de kuzu... pisoteadas se ven, descoloridas. Alguien pasó primero monte arriba esta senda.

葛の花 踏みしだかれて、色あたらし。 この山道を行きし人あり

Shaku Chōkū (Orikuchi Shinobu)

#Shaku Chōkū#Orikuchi Shinobu#literatura japonesa#poesía contemporánea#tanka#silencio#soledad#instrospección#otro#traducción©ochoislas#釈迢空

1 note

·

View note