#Sebaldian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Have you totally disclaimed the "penitential realism" idea? I still find it to be a useful concept sometimes -- in defining what I think Chabon was aiming for with his Sherlock Holmes novella, for instance. With the dawning of the 2010s this genre seems to have taken its leave. Maybe it's easier to just call things "Sebaldian", since along with Coetzee he's probably the exemplar that has proven to have the most staying power, and people will generally know what you mean if you invoke his name.

I think it still holds if we're talking about an aesthetic of miserabilist minimalism, though the politics have slightly shifted to be less cosmopolitan, less "global," than the Coetzee or Sebald model, and more mundane or personal instead. For example, that controversial "cool girl novel" article from last week seemed in its way to be about penitential realism. I tried to read I Fear My Pain Interests You—I fear it didn't—and that seems to fit the bill, too. A new novel from Teju Cole has been announced. The first line of the synopsis: "A weekend spent antiquing is shadowed by the colonial atrocities that occurred on that land."

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Things are always ever only ever about to happen”: Falling Hour by Geoffrey D. Morrison

We all know the Sebaldian trope—man/woman goes for a walk and thinks about “stuff.” In Canadian poet Geoffrey D. Morrison’s debut novel, Falling Hour, a man takes a picture frame to a park on a summer day, the outside world mysteriously recedes, and he spends the rest of the day thinking about “stuff”—or so it seems. Over the course of this oddly distended day, the narrator who introduces himself…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Błękitny Wieżowiec (the Blue Skyscraper), Warsaw. This massive, mirrored tower is on a prominent intersection called Plac Bankowy (Bank Place), and on the other side of its bulky, stepped-pyramid base is the single-block long Tłomackie (to the left of the building in the second photo). It was this little street, once a large formal square, that was the address of the site’s previous structure, the magnificently palatial Great Synagogue of Warsaw, one of the largest and grandest Jewish temples in the world. As a final act of annihilation at the conclusion of the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943, the SS dynamited the building. I saw this tower earlier in the day, the MetLife sign in the distance, and as I was researching the sites and contours of the Ghetto, I was haunted to discover this history, even more so when later I passed by this reflective office building which seems to have no reference to, or acknowledgment of, its sacred predecessor. And I was particularly awed to learn that I just happened to be walking around this glossy, oblivious commercial successor on the 76th anniversary of the spring morning that the Nazis detonated the charges. It seemed to be an almost Sebaldian coincidence.

Jerzy Czyż, Andrzej Skopiński, Jan Furman, Lech Robaczyński, Marzena Leszczyńska, architects, 1976, 1989-91. Photos May 2019 Bauzeitgeist.

#architecture#building#tower#tall building#skyscraper#skyscrapercity#skyscraper city#warsaw#architectural history#architecture photography#architectural photography#archilovers#reflective glass#blue mirrored glass#mirrored glass#cityscape#w.g. sebald#Sebald#Sebaldian#fog#mist

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

“El Sueño de la Razon Produce Monstruos” — Francisco Goya

there is a catch: sueño, the Spanish word for “sleep,” can also be translated as “dream.” What if the monsters are present not because reason isn’t awake to fend them off but because reason, in its slumber, actively generates them? If monsters can exist not despite reason but as a consequence of it, then perhaps we’re not as safe in the rational world—the land of logic and science—as we thought.

…at the time it seemed a harbinger of chaos and destruction. “Inside the void his metrics predicted, the fundamental parameters of the universe switched properties: space flowed like time, time stretched out like space,” Labatut writes.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rachel Eisendrath's Gallery of Clouds (Book acquired, like maybe three weeks ago?)

Rachel Eisendrath’s Gallery of Clouds (Book acquired, like maybe three weeks ago?)

Rachel Eisendrath’s Gallery of Clouds is new in hardback (?!) from NYRB. The book showed up a few weeks ago at Biblioklept International Headquarters on a week when like six books showed up. I finally got into it the other week, and it’s cool stuff. Gallery of Clouds has a Sebaldian vibe—discursive, academic, encyclopedic, and frank, with lots of black and white photographs—but it’s also its own…

View On WordPress

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sebaldian Vettel 😔😭

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Book Review | To the River by Olivia Laing

‘A river passing through a landscape catches the world and gives it back redoubled: a shifting, glinting world more mysterious than the one we customarily inhabit.’

On a midsummer morning, Olivia Laing set off on a journey that took her along the River Ouse from source to sea. The Ouse, the river where Virginia Woolf drowned herself, is a place Laing is attached to and like Woolf, Laing is fascinated by the alluring yet deadly element of water. Laing knows very well that place is not one-dimensional; various moments in time are superimposed in a landscape, so that place is haunted by stories from the past, and ghostly figures tread and re-tread the place beneath the surface of the present. This is why ‘To the River: A Journey Beneath the Surface’ is a mixture of travel book, nature writing, memoir, biography, and history. Laing minutely records the paths she takes and the landscape (she has a particularly keen eye for the flora) while reflecting on herself and recalling her memories; but she also narrates a myriad stories that are connected to the River Ouse and its surrounding landscape, ranging from Mansell’s discovery of the iguanodon to Kenneth Grahame’s biography. Her digressive curiosity reminded me very much of W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. Perhaps some may be frustrated by so many tangents, but I personally love this very allusive kind of writing. So while Laing physically traverses space, her mind (and To the River’s narrative) moves through time, too. Woolf is a significant and recurrent ghostly presence in To the River and I thoroughly enjoyed Laing’s reflection on her life and work. All this is delivered in an elegant and often quotable writing. This was a pleasure to read not just because I love Sebaldian, hybrid texts, but also because of Laing’s gentle, compelling, and sensitive (especially towards the environment) personality that comes through.

This is one of those haunted and haunting books.

Buy this book from Book Depository by clicking here (affiliate).

#to the river#olivia laing#canongate books#book review#book blog#book blogger#reader#read#reading#literature#booklr#book aesthetic#bookshelf#shelfie

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sebaldian Vettel!! Hahahah

0 notes

Text

The dark, intrinsic humour of W.G.Sebald

Sizewell beach, with mysterious fridge that appeared one day - photo by author

When I first read W.G.Sebald, around 10 or 12 years ago, as a result of reading some review in either the London Review of Books, or was it the New York Review of Books, I forget which and certainly cannot recall which book was under discussion, I was like many before and since mesmerised by the dreamlike narrative flow, its meandering sentences that wind their way through sub-clauses and conjoin to form paragraphs that offer no natural pause for breath for many pages, its seamless shifts of direction, subject and focus, the aura of melancholy, the obsession with decay and destruction as the only historical constant, the omnipresent references to learning and facts that were often so obscure that verification would have been impossible or at least hard to achieve, even if there had been any point in seeking to ascertain to what extent the author – or was it the narrator, at whatever level, and in that near indistinguishable tone that left one uncertain unless the author constantly reminds us as often is the case who is indeed the narrator at a given point - was indeed imparting knowledge or learning grounded in what might be historically or factually verifiable material, and not least by the somewhat flat monotone of the English language of the translated text that was both natural yet incongruous, given the sad or so to speak dismal quality of so much of the content, and yet which seemed to match the gentle undulations of the ever-eroding Suffolk coastline that is the scene of his pilgrimage in the Rings of Saturn. Which is still my favourite.

What I had not registered, when I had read his main four works first time round, was any sense of the comic as part of, indeed intrinsic to, Sebald’s armoury. The books indeed gave the opposite impression – a hypnotic but constantly depressing perspective on the human condition and human history. But I now smile a lot as I read, in between the melancholy.

In recent months, and in part inspired by my desire to become more fluent (as reader, alas not yet as speaker) in the German language, and in part with an amateur’s interest in the techniques of translation, I have re-read both the Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz, this time in German as well as English, with the two language versions side by side. Or more precisely, around one page at a time in German followed by the same page in English, to see how far I had correctly divined the meaning. It was a very slow but often inspiring process. I saw - and also heard, as I read many passages half aloud to myself - how the German language version (which is the original) has a very different rhythm and tone from the English; it is far more expressive, alliterative and even onomatopoeic in the original, which is no criticism of his very fine English translators.

But above all, I had to read each word and clause closely, often several times, in order to understand the text, and thus gain a far stronger sense of what effect the author was aiming to achieve. And I have concluded – for all the terrible matters that Sebald recalls and recounts – that interwoven in the whole serious Sebaldian enterprise there is also a mischievous and dark sense of humour, almost always swimming beneath the surface and which from time to time emerges from the depths as evidently comic writing.

Sebald’s picture of Dunwich empty beach in Rings of Saturn

Or indeed, comic photography. For can we really believe, to take a random example, that Sebald’s photo (p.155 in the English version) of the North Sea at Dunwich, showing a dull unpeopled shingle beach devoid of interest or aesthetic quality, was chosen for any non-comic purpose? Dunwich, of course, was a godsend to Sebald’s general narrative of decay and transience; an example of a once-thriving port that has been destroyed and washed away by the forces of time, tide, storm and erosion. But the photo selected and inserted deliberately exaggerates and ironises the (in reality non-existent) contemporary boring-ness of the remaining hamlet.

Author’s photo of empty Sizewell beach, from which one wife has been ‘disappeared’

Now no one can accuse Sebald of not being mischievous (and misleading). On the very next page we find a picture of the “Eccles Church Tower” standing in the sand, just yards from the sea, which, he tells us, “still stood on Dunwich beach” until about 1890; moreover, “after Eccles Tower had also collapsed, the only Dunwich church that remained was the ruin of All Saints”.

I had never heard of Eccles Tower at Dunwich, but had assumed Sebald would not have made this up… but Sebald never claimed that he was writing pure documentary or accurate material. And he certainly wasn’t in accurate mode on this occasion. The Eccles Tower was so named because… it was never in Dunwich but in Eccles-by-the-Sea, 50 miles away on the north-east coast of Sebald’s own home county of Norfolk! The village and church of Eccles did however suffer a similar fate to Dunwich in that, over centuries, it was washed into the sea. (I learnt all this from a blog by Homo Ludens dated October 2007, though it is written about in more ‘literary’ reviews).

It is inconceivable that Sebald was confused or negligent about the Eccles Tower; since the facts are easily ascertainable by anyone truly interested, he can surely not have been hoping to deceive yet avoid discovery, nor does the insertion add any obvious narrative or other advantage (save maybe to underlines the unreliability of both the narrator and of memory in general). It seems to me that this is one of many examples of Sebald simply teasing his readers with games, amid his many horrific themes, setting them puzzles if they wish to delve further.

I am sadder (but wiser) to learn that there is no evidence that the train on the branch line from Halesworth to Walberswick was ever in the service of the Chinese Emperor in Beijing, as is proposed by Sebald.

Photo https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_rail_transport_in_China#/media/File:OpeningDay.jpg

It is a ‘truth’ that all readers surely yearn to believe, and the link is a literary necessity for Sebald to slide into the tale of imperialist interventions in China in the mid 19th century. Yet the fact that this tale of the Chinese train is pure invention is plain to see, once we realise that Sebald mixes playful post-truth with his more serious intent to recall past sufferings that humans have imposed on each other. He lures us into his false linkage as follows:

“According to local historians, the train that ran on [the branch line] had originally been built for the Emperor of China. Precisely which emperor had given this commission I have not succeeded in finding out, despite lengthy research; nor have I been able to discover why the order was never delivered or why this diminutive imperial train, which may have been intended to connect the Palace in Peking, then still surrounded by pinewoods, to one of the summer residences, ended up in service on a branch line of the Great Eastern Railway. The only thing the uncertain sources agree on is that the outlines of the imperial heraldic dragon, complete with a tail and somewhat clouded over by its own breath, could clearly be made out beneath the black paintwork of the carriages, which were used mainly by seaside holidaymakers and travelled at a maximum speed of sixteen miles per hour.”

http://thelostbyway.com/2013/09/w-g-sebalds-southwold.html

In retrospect, I cannot but admire and smile at the references to unnamed “local historians”, to the author’s “lengthy research” - which, alas!, does not help him succeed in finding out more - and to the unspecified “uncertain sources”.

Over the years, I have read many articles and exchanges about Sebald’s writing, but very few comment on the comedic dimension of his work, and those who do sometimes seem uncertain whether the effect is comic despite the author’s intention, or because he was, in the end, an implicitly witty writer, alongside his other qualities.

In her Introduction to “The Emergence of Memory: Conversations with W.G Sebald”, the American writer Lynne Sharon Schwartz emphasizes

“His dreamlike narratives, meandering yet meticulous, echo the lingering state of shock that is our legacy – not only from the wars of recent memory but from the centuries of colonialism that preceded them, indeed, history’s ‘long account of calamities’”.

But she adds,

“In the Rings of Saturn, to my mind Sebald’s best work, his imagination is given free rein and his digressive bent carried to its most extreme – almost comic – reaches. The swirling paths of thought cast a spell: if the reader is willing to submit, the author’s sensibility will carry him toward ever more tangled and distressing tales of decay, entropy, and destruction.” (My emphasis).

In a brief survey of the various authors’ contributions to her book, Schwartz notes that

“[Tim] Parks, incidentally, is the only writer to mention Sebald’s humor, which glimmers slyly through his pessimism and is often overlooked.”

And Parks himself refers to Sebald’s “accustomed blend of slyness and grim comedy” and describes how

“All too soon, however, and this is one of the most effective elements of comedy in Sebald’s work, the concrete will become elusive; the narrative momentum is dispersed in a delta as impenetrable as it is fertile.”

For me, and seemingly also for Parks, it is certain that Sebald knowingly wove comedy into his darker narrative meanders; and I am equally confident that many (though not necessarily all) of his factual errors (like the Eccles Tower) were likewise deliberately placed, either as a means of sliding the narrative apparently seamlessly in the direction he wanted next to explore, or simply as a game played with the reader.

Others are less sure whether the use of comedy and the falsified “facts” were deliberate. Michael Hutchins, in his contribution on Sebald in another collection of essays, “Authentisches Erzählen: Produktion, Narration, Rezeption”, claims that

“It often remains unclear whether Sebald’s faulty statements represent “learned jokes” or the work of a dyslexic scholar.”

And even the late Jenny Diski seemed uncertain about his comedic intent (or lack thereof). In an article in 2000 for the London Review of Books, she says:

“After a while this super-sensitised melancholy becomes comic. One’s patience is tried as it is with those tormented heroes of Dostoevsky, if you read them after adolescence. For God’s sake, Raskolnikov, get a hold on yourself, pull yourself together. Sebald’s narrator is for all the world a middle-aged existential wanderer, out of place, out of time, and wallowing in every miserable moment, sizing himself up against other grim, unhappy wanderers: Casanova in prison, Stendhal hopelessly besotted, Kafka tormented about his longings and terror of love in a clinic in Riva. There is comedy in the grim solemnity and it may well not be accidental, because, after all, if life is not appalling, it is absurd.” (My emphasis).

In his book “Understanding W.G.Sebald”, Mark Richard McCulloh sees the frequently satirical elements in Sebald’s writing, and clearly views this as intended by the author:

“The overriding mood many perceive in Sebald’s work is still the melancholy, the mournful, the autumnal. If one examines Sebald’s corpus as a whole, however, it becomes apparent that similar appellatives such as “melancholy” and “somber”…are simply too sweeping. There are satirical elements that emerge in his prose, products of his humor and astute powers of observation..”

Sebald has many critics who perceive only the dark side, and none of the humour which I consider to be the natural counterweight to his pessimism. Alas, Alan Bennett is one who only sees Sebald hoving to the darkly depressive side:

“Sebald seems to stage manage both the landscape and the weather to suit his (seldom cheerful) mood… ‘Never yet on my many visits […] have I found anyone about.’ The fact is, in Sebald nobody is ever about. This may be poetic but it seems to me a short-cut to significance.”

Whereas for me, the fact that for the narrator “nobody is ever about” is itself a reflection of the twinkle in Sebald’s authorial eye.

Michael Hofmann likewise fails to see much (well, in fact anything) positive in Sebald. In an article in Prospect magazine in September 2001, entitled “Sebald’s fog”, he not only dismissed his writing as a whole, but pointedly refers to his lack of humo(u)r:

“But what was even stranger was that Sebald operated without any of the rigmarole or pleasantness of the novel. The complete absence of humor, charm, grace, touch is startling – as startling as the fact that books written without them could enjoy any sort of success in England…”

And horror of horrors, in her 2003 New York Times review of “On the Natural History of Destruction”, the literary critic Daphne Merkin (1) sees any humour displayed by Sebald as simply being in poor cultural taste:

Needless to say, the colorless, nomadic universe he inhabits, where the pizzerias are dreary and the hotels unwelcoming, offers few flashes of humor except of the most heavy-handed, ironic variety (the eponymous Jacques Austerlitz recalls ordering an ice cream that turned out to be ''a plasterlike substance tasting of potato starch and notable chiefly for the fact that even after more than an hour it did not melt'').

I think this wilfully misses the broader point that in Sebald, the humour is in fact intrinsic to the very relentlessness of his dystopian narrative. Those constantly dreary pizzerias or hotels never fail to make me smile, knowing their type all too well…

It is true that on occasions – though they are not frequent – Sebald unleashes an overt, darkly ironic polemic, directed against some unsuspecting icon of modern life, great or small. In the Rings of Saturn, his description of the once (but no longer) prosperous and fashionable coastal resort of Lowestoft attracts his most biting prose.

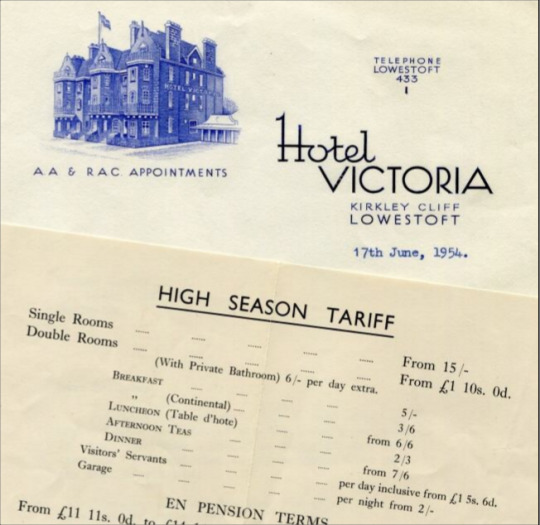

Victoria Hotel Lowestoft with 1954 price list - including for servants. Photo http://www.oldlowestoft.co.uk/?post_WW2...:Hotel_Victoria_1954

The particular victim is the Victoria Hotel (in the English version, it is called The Albion; could it be the publishers feared a libel suit?) which seems in reality to have been a rather genteel establishment, but this is Sebald’s take on it in the mid 1990s:

I stood for a good time in the empty lobby and wandered through the public rooms, which were completely deserted even now at the height of the season – if one can speak of a season in Lowestoft – before I happened upon a startled young woman who, after hunting pointlessly through the register on the reception desk, handed me a huge room key attached to a wooden pear…. That evening I was the sole guest in the huge dining room, and it was the same startled person who took my order and shortly afterwards brought me a fish that had doubtless lain entombed in the deep-freeze for years. The breadcrumb armour-plating of the fish had been partly singed by the grill, and the prongs of my fork bent on it. Indeed it was so difficult to penetrate what eventually proved to be nothing but an empty shell that my plate was a hideous mess once the operation was over. The tartare sauce that I had had to squeeze out of a plastic sachet was turned grey by the sooty breadcrumbs, and the fish itself, or what feigned to be fish, lay a sorry wreck among the grass-green peas and the remains of soggy chips that gleamed with fat.

(The German language original is even better in its display of contempt for the offering – no attempt here at subtlety!). (see footnote 2)

Or take Sebald’s diatribe against the (then) new Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris… For me, this is again comedic, though not in any way that risks causing laughter. It is its sheer relentless grumpiness that – as it progresses - induces a smile in the reader, at least in me. The attributed narrator of this passage, Austerlitz, as cited by the principal narrator (who gives us no name but while doubtless resembling is not necessarily identical to Sebald) searching for traces of his father lost (and almost certainly murdered in a death camp) in the war, takes time out in the book to express at some length his utter loathing of the new library. One feels that Sebald is here hardly bothering to maintain the thin dividing line between himself and the narrator(s) – that he is simply using the opportunity to express his own contempt for the Mitterandian pharaonic building and its Kafkaesque minders; we sense that Sebald himself must have been displaced from the much-loved old Bibliothèque nationale in the rue de Richelieu (which by coincidence is the very same street in which the Paris office of the Conseil des Communes et des Régions de l’Europe (CCRE) was situated when I was its Secretary General…)

“I do not think, said Austerlitz, that many of the old readers go to the new library on the Quai François Mauriac. In order to reach the Grande Bibliothèque you have to travel through a desolate no-man’s-land in one of those robot-driven Métro trains steered by a ghostly voice, or alternatively you have to catch a bus in the Place Valhubert and then walk along the windswept river bank towards the hideous, outsize building, the monumental dimensions of which were evidently inspired by the late President’s wish to perpetuate his memory whilst, perhaps because it had served this purpose, it was so conceived that it is, as I realized on my first visit, said Austerlitz, both in its outer appearance and inner constitution unwelcoming if not inimical to human beings, and runs counter, on principle, one might say, to the requirements of any true reader.”

Photo via https://ilovearchitecture.wordpress.com/page/2/

And so on and on, not releasing its prey for pages, nor pausing for paragraph breaks:

“When I first stood on the promenade deck of the new Bibliothèque Nationale, said Austerlitz, it took me a little while to find the place where the visitor is carried down on a conveyor belt to what appears to be a basement storey but, in reality, is the ground floor. This downwards journey, when you have just laboriously ascended to the plateau, struck me as an absolute absurdity, something that must have been devised – I can think of no other explanation, said Austerlitz – on purpose to instil a sense of insecurity and humiliation in the poor readers, especially as it ends in front of a sliding door of makeshift appearance which had a chain across it on the day of my first visit, and where you have to let yourself be searched by semi-uniformed security men. The floor of the large hall which you then enter is laid with rust-red carpet, on which a few low seats are placed far apart… And of course, Austerlitz continued, you cannot leave the red Sinai hall for the inner citadel of the library without more ado; first you have to put your request at an information point staffed by half a dozen ladies, whereupon, if this request to any degree exceeds the very simplest contingency, you take a number, like a visitor to a tax office; you then have to wait, often for half an hour or more, until another member of staff calls you into a separate cubicle, as if you were on business of an extremely dubious nature, or at least had to be dealt with away from the public gaze, and here you must say again what it is you have come for and receive the relevant instructions.”

Even quoting these passages at some length fails to give their real feel, since it is precisely their being embedded in the constant unending flow of thoughts and prose that gives (for me) the clear feeling that Sebald is having a kind of malicious fun, a verbal revenge on those who created and now control the new fortress-library and jealously guarded and restricted access to its store of knowledge. And yet the humour is always embedded in the most serious; the overt purpose of Austerlitz’s research is his quest for a father lost to him, but who was no doubt destined – with assistance from the French authorities - for the Nazi death camp. Thus the comedy, which undoubtedly infuses his prose, is dark indeed.

For my final example of Sebald’s humour, I turn to Vertigo. Now, Vertigo – like the Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz - can hardly be deemed light relief; to cite Jenny Diski’s LRB review again

“Sebald’s vertigo is caused by the centrifugal force of uncertainty that pervades everything, including our consolations.”

Nothing evidently humorous there; yet as she later says, “After a while this super-sensitised melancholy becomes comic.” Her problem, as I have cited above, is that she is not clear whether the intent was humorous, or merely the effect. But, to take an example from Vertigo (p.103) cited by Tim Parks, can one really doubt that Sebald was quietly joking when he describes the narrator’s reaction to the sight of a beautiful nun and girl in a railway compartment?

“Opposite me sat a Franciscan nun of about thirty or thirty-five and a young girl with a colourful patchwork jacket over her shoulders….The nun was reading her breviary and the girl, no less immersed, was reading a photo story. Both were consummately beautiful, both very much present yet altogether elsewhere… I admired the profound seriousness with which each of them turned the pages. Now the Franciscan nun would turn a page over, now the girl in the colourful jacket, then the girl again and then the Franciscan nun once more. Thus the time passed without my ever being able to exchange a glance with either the one or the other. I therefore tried to practice a like modesty, and took out Der Beredte Italiener, [“the eloquent Italian”] a handbook published in 1878 in Berne, for all who wish to make speedy and assured progress in colloquial Latin.”

The Eloquent Italian! Yet Parks can only - rather comment,

“Only Sebald, one suspects, would study an out-of-date phrase book while missing the chance to speak to two attractive ladies.”

A page of the alleged phrase-book’s translation is offered us in a picture adjoining this text, with a few words or phrases underlined by someone… in English, these would be ‘all saints’, ‘Carnival’, ‘angel’, ‘sin’, ‘fear’, ‘truth’, ‘lie’ and ‘pain’…

The two females, as the train approaches Milan Central Station, insert bookmark or green ribbon into their respective tomes, and when it arrives “disappear”, leaving the narrator standing on the platform claiming a sense of having been abandoned but still able to pose ludicrously grandiose and meaningless questions, and to generalise from his own momentary attraction to the duo, to the generalised human yearning to copulate and populate:

“What connection could there be, I then wondered and now wonder again, between those two beautiful female readers and this immense railway terminus which, when it was built in 1932, outdid all other railway stations in Europe; and what relation was there between the so-called monuments of the past and the vague longing, propagated through our bodies, to people the dust-blown expanses and tidal plains of the future.”

Photo of Milano Central Station via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Skateboarding_at_Central_Station,_Milan.jpg

Here, Sebald has descended into surely conscious self-parody – the questions are meaningless, as he knows, and no answer is given. All the narrator does is stroll down the platform, and buy himself a map of the city. A city map which contained on its front, we are told, an image of a labyrinth, and on its back a claim to be “Una guida sicura per l’organizzazione del vostro lavoro” - “A secure guide for the organisation of your work”.

I cannot finish without citing one eminent source that supports my own view of Sebald:

“[His books] are notable for their curious and wide-ranging mixture of fact (or apparent fact), recollection and fiction, often punctuated by indistinct black-and-white photographs set in evocative counterpoint to the narrative rather than illustrating it directly. His novels are presented as observations and recollections made while travelling around Europe. They also have a dry and mischievous sense of humour.”

The eminent source is of course none other than Wikipedia – and against the last sentence we find the following addition: “citation needed”. Well, here I am.

Postscript

In reading quite a lot of articles about Sebald and his use (or non-use, or abuse) of humour I was happy – since my blog is named “Refractions”, to find two comments that refer to the Sebald as having a “refracted” view of the world:

“Sebald’s refracted and sometimes alienated views of both his native Germany and his adopted English homeland have had astonishing resonance in the German- and English-speaking worlds.”

Note on Amazon.co.uk page to W. G. Sebald - A Critical Companion (Literary Conjugations) Paperback – 1 Jul 2004

I was immediately hypnotised by the curious prose style, so flat and ostensibly inconsequential, which describes a kind of meditative interior monologue, not at all the world as it is seen and described by an ordinary person, but a view of the world seen through a glass darkly and refracted through the strange and sometimes uncomfortable imagination of a dyspeptic and exceptionally knowledgeable, middle-aged professor of German literature, whom one presumes has never been married and who decides to take a long and entirely purposeless walk round the shores of East Anglia meditating on aspects of its history and what he sees en route.

Charles Saumarez Smith Review of Austerlitz, The Observer 30 September 2001

Footnotes

(1) I know almost nothing about Ms Daphne Merkin but her review leaves me with a very, very dim view of her sense or sensibility - she says this in the same essay:

Who else but a gloomy, deskbound intellectual would warm to a narrator who chooses as his ''favorite haunt'' the Sailors' Reading Room in Southwold, which is ''almost always deserted but for one or two of the surviving fishermen and seafarers sitting in silence in the armchairs, whiling the hours away''?

Speaking for fellow deskbound gloomsters (not sure about the intellectual bit) I can assure Ms Merkin that the Southwold Sailors’ Reading Room is a wonderful, peaceful place overlooking the sea, in one of England’s favourite (for the middle classes, at least) coastal resorts.

Photo of the Sailors’ Reading Room via http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2607778

(2) The German passage, concerning the delicious fish and chips:

Dieselbe verschreckte Person ist es auch gewesen, die später in dem großen Speisesaal, in dem ich an jenem Abend als einziger Gast saß, meine Bestellung entgegennham und die mir bald darauf einen gewiß seit Jahren schon in der Kühltruhe vergrabenen Fisch brachte, an dessen paniertem, vom Grill stellenweise versengten Panzer ich dann die Zinken meiner Gabel verborg. Tatsächlich machte es mir solche Mühe, ins Innere des, wie es sich schließlich zeigte, aus nichts als seiner harten Umwandung bestehenden Gegenstands vorzudringen, daß mein Teller nach dieser Operation einen furchtbaren Anblick bot. Die Sauce Tartare, die ich aus einem Plastiktütchen hatte herausquetschen müssen, war von der rußigen Semmelbröseln gräulich verfärbt, und der Fisch selber, oder das, was ihn vorstellen sollte, lag zur Hälfte zerstört unter den grasgrünen englischen Erbsen und den Überresten der fettig glänzenden Chips.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Echoes & Imprints: Towards A Sebaldian Cinema

Echoes & Imprints: Towards A Sebaldian Cinema

This is an edited transcript of a talk given at Norwich Castle on Tuesday the 27th of August 2019. Detail has been edited, aspects taken out and points clarified from the original talk. My thanks to Dr. Nick Warr and Philippa Comber in particular for the help and information given both before and after the talk.

Introduction

Considering the wealth of imagery on the walls of the Line of Sightexhib…

View On WordPress

#45 years#Adam Scovell#alain resnais#alain robbe grillet#andrew haigh#austerlitz#austerlitz film#Ben Rivers#Celluloid Wicker Man#gilles deleuze#grant gee#hauntology#Last Year In Marienbad#mark fisher#patience after sebald#Rainer werner Fassbinder#sebald#sebald analysis#sergei loznitsa#super 8#tacita dean#the caretaker#the emigrants#the rings of saturn#thomas honickle#Vertigo#w g sebald#w g sebald analysis#w.g. sebald books#Werner Herzog

0 notes

Photo

Postscript to the last entry: I forgot to mention the single most startling assertion in Ruby’s essay, offered as an aside: a dismissal of the very surface marker of the “Sebaldian”! (If I pick up a contemporary novel and see some grainy black-and-white photos, I usually put it right back down.) Even more startling because Ruby’s last appearance here at Grand Hotel Abyss was as a McLuhanesque media theorist. I am not a media theorist, but, maybe because I teach a course called “Readings in the Graphic Novel” literally every semester, I think it probably does matter that the novelist Ruby ambivalently hails as embodying The Spirit of the Age is also in some sense a graphic novelist.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

After Sebald

… moving on

– or maybe not …

because honestly; isn’t this poem, like so many exquisite works of art, just another variation of the troublesome Sebaldian story?

Maged Zaher

Untitled

I’m few déjà-vus from repeating my whole life I need to study the shapes of things before death Before declaring myself a better failure: waiting mostly for files to get uploaded or downloaded. My…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Sipos Eszter és Horváth Csaba Árpád

The **** Factory/Chapter 3

2018. november 15.- december 13. Liget Galéria

Megnyitó: november 15. 18 h

Megnyitja: Tatai Erzsébet művészettörténész

>>>> For English version scroll down

Hogyan lehet a háború egyszerre elavult és csúcstechnológiai tevékenység? A média hírei a fegyverkezés tekintetében egészen más képet sugallanak, mint amit számokban mérhetünk, ugyanis „a 20. század második felében Föld nagy részén a háború ritkább lett, mint valaha. Míg a mezőgazdasági társadalmak idején az erőszak az összes haláleset mintegy tizenöt százalékát okozta, a 20. században már csak az öt százalékát, a 21. század elejére pedig csupán a globális halálozás körülbelül egy százalékáért volt felelős. 2012-ben világszerte nagyjából 56 millió ember halt meg ebből (…) 120 000 vesztette életet háborúban és 500 000 bűncselekmény következtében (…) ezzel szemben másfél millióan haltak meg cukorbetegségben.”[1]

Korunk háborúi használják a csúcstechnológia legfrissebb vívmányait, mégis kis túlzással archaikus, már-már barbár tevékenységként tekintünk rájuk, amelyek ennek ellenére elég nagy szeletet szakítanak ki a globális gazdasági termelésből. (Annak is főleg a fekete és szürke zónájából.) Kiállításunk filmes, installációs és festészeti elemei egyaránt reagálnak erre a kettősségre, a galériatérben keverednek a különböző forrásokból származó hiteles dokumentumok és az azokra tett könnyedebb, játékos reflexiók is; így illeszkedik az archív tisztább, retrospektív nézőpont a jelen érzelmektől telített szubjektív pozíciójához.

A Liget Galéria terében megjelenő képek, videó és szoborelemek sajátos, olykor duplikált elrendezésben láthatóak. A célunk, hogy a valóság (vagy amit annak hiszünk) és a fikció (vagy amit annak hiszünk) új és értelmezhető rendszerré ��lljon össze, olyanná, amely - a kiindulási témánk kapcsán - új kérdéseket indít el a nézőben. Rengeteget tanultunk a XX-XXI. századi irodalomtól, példaképp a Sebald-i tényregényekből, ahol a dokumentum átszűrődve az elbeszélő szubjektumán teljesen új minőséget és új összefüggéseket hoz létre, olyan formációt, amely képes eddig megvilágítatlan kérdéseket előtérbe állítani igazról és hamisról, objektívről és szubjektívről. A mediális diskurzusban posztinternet, valamint a politikai közbeszédben post-truth korszakként definiált időszakban ez a megközelítés különösen érdekessé vált számunkra.

A kiállítás az NKA támogatásával valósult meg.

[1]

Yuval Noah Harari: Homo Deus – A holnap rövid története, Animus Kiadó, 2017., 22. p

Előzetes emailes bejelentkezéssel látogatható.

Bejelentkezés itt: [email protected], [email protected]

/// ENG:

How can War be simultaneously antiquated and a pursuit of cutting edge technology? With respect to armament, news in the media suggests an entirely different picture than what can be measured in numbers, namely: “In the second half of the 20th century, in most areas wars became rarer than ever. Whereas in ancient agricultural societies human violence caused about 15 per cent of all deaths, during the twentieth century violence caused only 5 per cent of deaths, and in the early twenty-first century it is responsible for about 1 per cent of global mortality. In 2012 about 56 million people died throughout the world, 620,000 of them died due to human violence (war killed 120,000 people and crime killed another 500,000). In contrast 800.000 committed suicide and 1.5 million died of diabetes. Sugar is no more dangerous than gunpowder.”[1]

The wars of our era utilise the newest achievements in cutting-edge technology, and yet, with just slight exaggeration, we regard them as archaic, even barbaric activities, which, in spite of this, stake out quite a large slice of global economic output. (And of this, primarily from the black and grey zones.) The filmic, installational and painting elements of our exhibition all respond to this duplicity, with authentic documentary material originating from diverse sources amalgamated in the gallery space with lighter, more playful reflections upon them. In this way, the more pure, retrospective viewpoint of the archive adapts to the current subjective position that is saturated in emotion.

The images, video and sculptural elements appearing in the space of the Liget Gallery can be seen in a specific, even duplicitous arrangement. Our aim is to combine reality (or what we believe that to be) and fiction (or what we believe that to be) into a new and interpretable order, into such, that – in connection with the subject at our point of departure – it triggers new questions in the viewer. We have learned an enormous amount from 20th-21st-century literature: as a prime example, the Sebaldian novels of fact and fiction, in which documentary is filtered through the narrative subject, engendering entirely new correlations and a new quality: a kind of formation that is capable of bringing to the fore questions that were unelucidated up till now – on what is true and what is false, on the objective and the subjective. Within the media discourse, the post-internet, and in the political vernacular, the period that has become defined as the post-truth era, this approach has become particularly interesting to us.

[1]

Yuval Noah Harari: Homo Deus – A Brief History of Tomorrow. London: Harvill Secker, 2016.

The exhibition was supported by NKA (National Cultural Fund of Hungary).

You can visit the exhibition with cheque-in preliminary in email. Please fix time for visit through this email address: [email protected], or: [email protected]

Liget Gallery’s address: 1146, Budapest, Ajtósi Dürer sor 5.

#The **** Factory / Chapter 3#Sipos Eszter#Horváth Csaba Árpád#Liget Galéria#megnyitja: Tatai Erzsébet#Yuval Noah Harari

0 notes

Text

to look for stones to look ~ leveld kunstnartun #1

This is #1 of a series of blogs written from Leveld Kunstnartun, residency in Norway.

During the full month of August I am working together with Laura ten Zeldam, friend and fellow artist, at Leveld Kunstnartun, a residency in the countryside of Norway. Laura sees light as her main material. She is a window maker and a true craftswoman, trained in the arts of stained glass, drawing and painting, based in Brussels. She and I have been engaged ongoing conversations and small starts of collaborations for years, though this residency is the first time we are truly taking this further and embarking on a project together.

We travelled in Laura's old Peugeot with (very important) a cassette tape deck, making our way to Leveld in a slow Scandinavian roadtrip, driving through and camping in truly wondrous places, so that when we arrived at Leveld we already had quite some adventures behind us.

There is something about true forests, deep and dense, that thrills and overwhelms me, coming from The Netherlands (not exactly the country of wildness). Knolls and moss, animal footprints and feces, countless shades of green. And then, the mountains! Green rolling ones and higher ones in softer tones with glimpses of snow white. There is a river around the corner here, a strong one. When it hurts we return to the banks of certain rivers, wrote Czesław Miłosz. I found this line, and many strong others, in the book To the River by Olivia Laing, one of the books that serves as a companion to me here. When I packed it, I had no clue how fitting it would be, our studio and home being in such proximity to the river Votna.

In To the River, Laing follows the river Ouse from the source to the sea, wandering, wondering, writing in an almost Sebaldian style of myths as well as history, corpses as well as hummingbirds. The Ouse is the river in which Virginia Woolf drowned herself. She being a writer I admire, I have read and heard stories of her life, her mental breakdowns and her death before. Never as poignantly as here, though. Perhaps it was because I was walking by this river that day. Reading about how Virginia filled her pockets with heavy stones before walking into the river deeply unsettled me. Unable to put the images conjured by her act out of my mind, I worked with it by writing a text by mingling Woolf's words and my own and creating a few images.

to look for stones to look life in the face to weigh each one always to look life in the face to choose the heaviest and to know it for what it is to fill all pockets at last to know it to step into the river to love it for what it is to feel the weight and then to put it away

Stones and rocks have been recurring material in our first experiments, as shapes, as beings, as metaphors. An intriguing moment for me was when, after working on our own for a day or so, Laura and I exchanged something we made. I gave her the text I wrote (to look for stones to look life...) and she gave me a cut-out 'stone' out of paper, black ink, white ink and pencil. There was a a very different character and way of working in both pieces - hers having such a strong materiality, mine more of an emotional weight - and it was nice to just take something from the other and work with it, through it. We talked about how this paper stone could potentially be not only a depiction of nature, but some kind of nature in itself. I took it for a walk and photographed it, with this thought in mind.

I feel like we are in the very first stages of a conversation on how one sees, how one makes, how to retain a freeness in both seeing and making, as an artist, as a viewer. We see an aliveness in the rocks, the stones, the non-human, the river. In the studio right now there's an atmosphere related to arte povera, animalism but also something more contemporary. I'm musing and trying my hand at writing some strange little poems;

rocks kneaded like dough by water and weather’s firm hands but slowly, slowly

rocks alter bruise (bleed?) but slowly, slowly

I was thinking of bodies too, human bodies as well as non-human bodies. Is there anything that is not transient, not susceptible to decay? It seems to me a question of time. Since a human body is softer than a stone's, it won't remain as long, though the stone too will hurt, pass, break down. Some of these thoughts were triggered or strengthened by reading the powerful thesis of my friend and wonderful artist Maya Watanabe, in which she questions what and who is considered alive, dead and grievable and what is not, in connection to cinema, a medium that in her view is capable of both severing and suturing the space between life and non-life.

All in all, I was affected these days, deeply, by the nature surrounding me, by Laura's companionship and creativity, by things I read, by something as big as a suicide, by something as small as a rock. I will end with a quote I found in Maya's work, by María Garcés: Being affected is learning to listen, taking things in and transforming oneself, breaking something of oneself and recomposing oneself with new alliances. (...) Learning to listen, in this way, is to take in the outcry of reality in its dual sense, or in its innumerable senses: an outcry that is suffering, an outcry that is the impossible-to-codify richness of voices, of expressions, of challenges, of forms of life.

0 notes

Text

sir lewis posted a pic to distract us from sebaldian

12 notes

·

View notes