#Santa Clara a Velha Coimbra

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

medieval women week (day three)

favourite royal mistress: inês de castro (1325-1355)

Inês de Castro hailed from the Galician region of Iberia that bordered Portugal. She was born in 1325 to Pedro Fernández de Castro, Lord of Lemos and Sarria, and his mistress Aldonça Lourenço de Valadares. In 1340 Inês travelled to Portugal as a lady in waiting to her newly married cousin Constanza of Castile. The diplomatic match with Infante Pedro of Portugal, the heir of King Afonzo IV of Portugal, was contracted to improve the strength of relations between Castile and Portugal. Pedro's mother, Queen Beatriz, was the youngest legitimate daughter of King Sancho IV of Castile. Pedro swiftly fell in love with Inês, and he neglected his wife, and this unsurprisingly angered the Castilians, they had begun an affair that didn't remain a secret for long. In January 1355, Inês was forcibly removed from court while Pedro was away hunting. She was taken to the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha in Coimbra. She had an emotional interview with the king, which evidently failed to dissuade him from killing her. On January 7 1355, his henchmen Diogo Lopes Pacheco, Pêro Coelho and Álvaro Gonçalves decapitated her in front of one, maybe both, of her and Pedro's small children. It is said that Pedro exhumed Inês' body from its grave in Coimbra and that he had her dressed, crowned and placed on the throne for her coronation.

#medievalwomenweek#history#medieval history#ines de castro#portuguese history#historicwomendaily#14th century#medieval portugal#women in history#european history

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

um passeio nos arredores — idealista/news #ÚltimasNotícias #Portugal

Hot News Conhecida por sua prestigiada universidade, uma das mais antigas da Europa, Coimbra encanta com seu patrimônio histórico e cultural. A cidade é um verdadeiro museu a céu aberto, onde você pode passear pelas ruas estreitas do centro histórico e se maravilhar com monumentos como a Sé Velha, o Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Velha e a Biblioteca Joanina. No entanto, além dos encantos da própria…

0 notes

Text

Uma cúpula perto do Céu

Agostinho Costa Mar-10-03-2024

A tarde já ia a meio. Tínhamos acabado de almoçar no Largo da Graça. Descíamos agora a Rua Voz do Operário. Um raiozinho de Sol surgiu por pouco mais de uns segundos, pois o Céu continuava fechado, a chuva a querer cair a todo o momento. E eis que chegámos… Entre a Calçada de São Vicente, à direita, e o Campo de Santa Clara, que se estendia à esquerda, com a feira da ladra já a terminar, à nossa frente o grandioso monumento, São Vicente de Fora. De fora, porque fora construído já para lá das muralhas da velha urbe.

Que monumental fachada! Com um corpo central Encimado por duas torres sineiras; uma ornamentação exuberante, com pilastras, cornijas e frontões, que prazer na sua contemplação! Mosteiro, igreja, panteão. Nele estavam sepultados os Bragança da última dinastia da nossa história. Nele se encontravam reflectidos períodos distintos da história de Portugal. Dom Afonso Henriques, quando fora construído em 1147; Filipe II de Espanha, que governou Portugal, o Filipe I, que lhe deu outra dimensão. E outras não menos importantes alterações, sobretudo a partir da independência com Dom João IV, que quis acabar com os testemunhos espanhóis. Ah, e o dia 1 de Novembro de 1755, que tragédia se abateu sobre ele…!

Que sensação me absorvia ao palmilhar os espaços do mosteiro. No claustro, com belas arcadas de mármore, aberto a um jardim, que seria pujante na sua vegetação, mas agora totalmente encharcado pela chuva que caía abundante. E que sensação!, na capela de Fernando Martins, o nosso Santo de Lisboa, António; o de Pádua para os italianos. Aqui viveu, aqui estudou, Cónego de Santo Agostinho, antes de se dirigir a Coimbra. Após, se dirigiu a Itália, ao mundo… Neste espaço museológico, na bonita capela a ele dedicada, algumas relíquias suas, o hábito de franciscano, o seu cajado… Mas ele não eé o padroeiro de Lisboa.

Pois, o padroeiro é São Vicente. Todo o monumento lhe é dedicado, e é bem antiga a lenda que o celebra. Diácono em Valência, lá pelo século IV, habitada pelos romanos, nunca quis abdicar da sua fé, a cristã. Por tal foi martirizado e os cristãos perseguidos. Muitos deles quiseram salvar os seus restos mortais. Fizeram uma viagem até ao Algarve. Aí foi construída uma capela, onde as suas relíquias foram escondidas. dom Afonso Henriques, conhecendo a história/lenda do santo, conseguiu, numa segunda tentativa, trazer o espólio do santo para Lisboa, onde lhe foi construído o belo monumento. Na viagem, as relíquias do santo foram acompanhadas por dois corvos, um à proa, outro à popa. E assim São Vicente se tornou o padroeiro de Lisboa e os corvos passaram a fazer parte do seu brasão de armas.

Entrámos na igreja. Monumental, grandiosa! com o seu tecto abobadado a grande altura, ornamentado com pinturas e frescos. As paredes, com os seus painéis de azulejo, representando cenas bíblicas e da vida de São Vicente. O seu chão, com belos mosaicos, que apetecia pisar com a maior suavidade. Sentia-se ali o sagrado, o espírito supremo…

Passávamos pela sacristia, pelo panteão dos patriarcas. A Carolina ia-nos dizendo que só existiam três no mundo, o de Jerusalém, o das Índias, o de Lisboa. Fora uma graça que o papa atribuíra a Dom João V pelas muitas benesses que lhe havia concedido. à nossa volta os túmulos dos patriarcas de Lisboa. Apreciámos um mais, fui passando a mão pelo seu túmulo, o de Dom José Policarpo, patriarca dos mais recentes.

Na sacristia encontrámos uma valiosa coleção de arte sacra, incluindo pinturas, esculturas e objetos litúrgicos. Com os seus móveis bem trabalhados, todas as gavetas fechadas, guardando as vestes de todos os dignitários da igreja que por ali haviam passado. Nesta sacristia era fácil apreender o mesmo ambiente, de ancestralidade, de religiosidade, de supremo, como em todo o conjunto monumental. Ah, a lembrança que me ocorre…

Que terrível dia me veio ao espírito. «a terra começou a tremer debaixo dos pés do rapaz, numa trepidação assustadora, e um novo ruído arrepiante se ouviu, como se alguma coisa descomunal estalasse. As pessoas gritaram, desesperadas, como se os gritos delas fossem suficientes para pôr termo ao acontecimento, mas pouco depois os gritos deixaram de se ouvir, pois o barulho da terra a tremer era tão intenso que nada mais era audível. Fora então que olhara para trás, para a Igreja de São Vicente de Fora, e o seu coração enchera-se de pânico ao ver o tecto do edifício abater, caindo para dentro da igreja, para cima da sua mãe. Um grito nascera-lhe nos pulmões e tentou correr, mas a terra não o deixava, não havia equilíbrio, e tropeçou e caiu. Voltou a ouvir os gritos, de pavor, e vinham de todos os lados da praça, das ruas, das janelas, e também da porta da igreja, onde os fiéis estavam apinhados, uns contra os outros, como se não fossem muitos, mas apenas uma massa de gente espalmada. Depois, as portas da igreja saltaram das enormes dobradiças e tombaram sobre os infelizes que ali estavam». É assim que Domingos Amaral no seu livro Quando Lisboa Tremeu, narra o acontecimento do dia 1 de Novembro de 1755. Só ali, dentro da igreja, quantas pessoas não terão morrido!

Avançávamos para o panteão dos Bragança. Ainda no exterior a capela dos meninos de Palhavã. Eram filhos ilegítimos de Dom João V, o filho de madre Paula… a famosa freirinha de Odivelas!

O Panteão dos Bragança, reis, rainhas, príncipes e infantes da IV dinastia ali estavam sepultados. Fora resultado da iniciativa Do rei D. Fernando II, que em 1855 o criou para que nele todos permanecessem, espalhados por vários locais. A dinastia iniciou-se com D. João IV e terminou com Dom Manuel II, que apenas governou dois anos, iniciada que foi a República em 1910.

A sala é um espaço de grandes dimensões, antigo refeitório. Os túmulos encontram-se encostados às paredes, sendo os dos reis encimados por coroas e o das rainhas por diademas. o túmulo de Dom João VI, que está em destaque, possui Na parte superior uma estátua do rei em tamanho natural, vestido com as suas vestes reais. A estátua está ladeada por duas figuras alegóricas que representam a Fé e a Justiça. Apresenta na parte frontal um rombo. Há dúvidas sobre a origem deste rombo, mas acredita-se que este terá sido feito quando se pretendeu investigar melhor a causa da morte do rei. Verdade?, descobriu-se grande quantidade de arsénio no seu organismo, o que provavelmente indica que terá sido envenenado… Só Dom Pedro IV, no Brasil, o coração no Porto, e Dona Maria I, na Basílica da Estrela, ali não estão.

Ainda descemos a ver a cisterna. estava quase cheia tal era a chuva que caía. Devido à mesma, não foi possível subir à cúpula. Não deixei, contudo, de lembrar aquela subida há uns anos. Fora espectacular! Nos finais do Verão, em plena tarde, Céu, sol, rio, tudo numa confusão de azul e doirado! e nas margens, toda a cidade… Mais ao longe, já se confundindo com o horizonte, a ponte sobre o Tejo. Momento muito belo, bem apreciado pelo meu espírito. Esta cúpula altaneira era visível de muitos pontos da cidade. Mas, a partir dela, aquilo que os nossos olhos abrangiam…! Será que se poderia dizer?, era o esplendor do mundo que se desvelava?!

0 notes

Text

DIÁLOGOS COM A PREEXISTÊNCIA

Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal.

Local: Coimbra, Portugal Data: 2018 Tipo: Trabalho acadêmico Status: Pesquisa Concluída Orientação: António Alberto de Faria Bettencourt

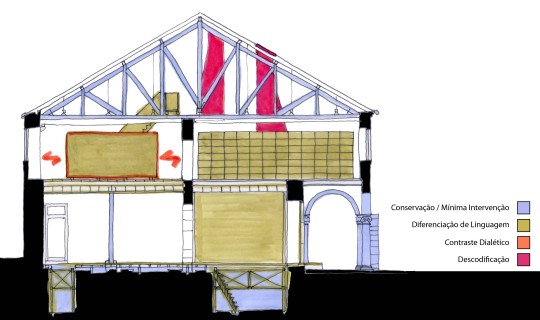

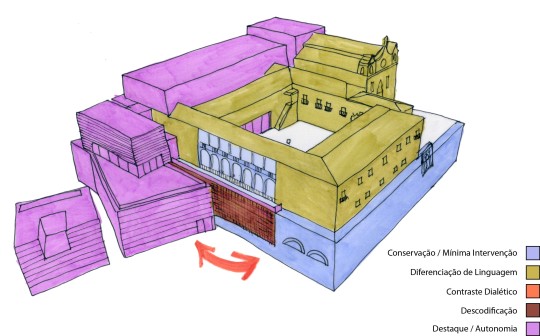

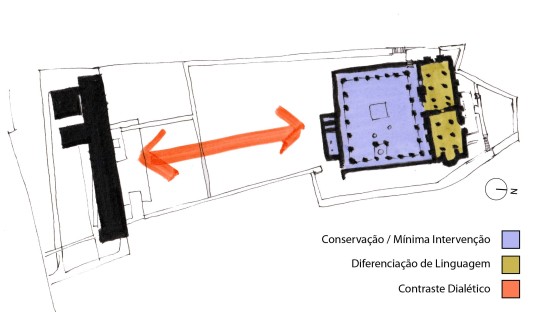

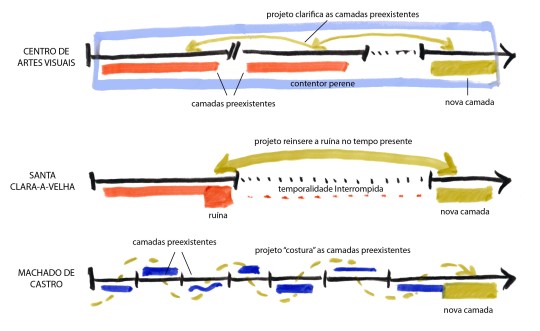

Nas últimas décadas, observou-se uma crescente valorização dos projetos de intervenção em edifícios preexistentes, em parte ligada a uma maior preocupação com a preservação do patrimônio cultural, mas, sobretudo, devido a seu caráter sustentável, tornando-se uma preocupação cada vez mais presente nas políticas governamentais e do setor da construção. No mundo de hoje, já não faz mais sentido a demolição integral das preexistências para a construção do novo a partir de uma folha em branco. Ao contrário, observa-se, cada vez mais, uma espécie de reconciliação com o passado, em que os resquícios materiais de outros tempos deixam de ser obstáculos para a criação e passam a ser objeto central do projeto contemporâneo, promovendo diferentes diálogos entre o antigo e o novo. A intervenção na preexistência constitui um exercício de projeto mais desafiador do que a nova construção, pois envolve uma série de questões articuladas com os valores intrínsecos relativos à composição arquitetônica e à materialidade do edifício, bem como a aspectos socioculturais e contextos urbanos de cada caso. Contudo, é preciso considerar-se um conhecimento de suporte referencial para o tratamento destes casos, com base técnica e juízo crítico adequados. Este trabalho tem como objetivo principal a contribuição com parte deste conhecimento teórico de suporte no âmbito da Reabilitação de Edifícios, através do estudo das categorias interpretativas de intervenção contemporânea no edificado propostas por três diferentes autores ligados à preservação do patrimônio e ao Restauro Crítico italiano: Claudio Varagnoli, Giovanni Carbonara e Beatrice Vivio. Com base nas categorias propostas pelos referidos autores, foram estudados três casos de intervenção no patrimônio cultural edificado do município de Coimbra, em Portugal: o Centro de Artes Visuais, o Mosteiro de Santa-Clara-a-Velha e o Museu Nacional Machado de Castro. A análise proposta consiste numa leitura crítica sobre os diálogos que os princípios de intervenção e as soluções projetuais assumem com suas respectivas preexistências, procurando compreender os diferentes tipos de relação linguística, material, funcional e temporal entre o antigo e o novo, numa perspectiva de reconhecimento dos seus valores e de sua transmissão ao futuro.

BAIXAR A DISSERTAÇÃO COMPLETA

0 notes

Text

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT ELIZABETH OF PORTUGAL The Queen Consort Feast Day: July 4

Elizabeth, daughter of Peter III of Aragon and Constance of Sicily, and the sister of three kings: Alfonso II and James II of Aragon and Frederick III of Sicily, was born in Aljafería Palace, Zaragoza, Kingdom of Aragon on January 4, 1271. At 10 years of age, she was given in marriage to Denis of Portugal, and bore two children, Alfonso, later became Afonso IV of Portugal, and Constance, who married King Ferdinand IV of Castile. Elizabeth is the great-niece of another saint - Elizabeth of Hungary.

Eventually, her prayer and patience succeeded in converting her husband, who had been leading a sinful life. She was modest in her dress, humble in conversation, and charitable towards the poor. It was her habit to provide lodging for pilgrims and to procure dowries for the poor girls of the kingdom.

One of the best moments of her life was the miracle of the roses. Caught one day by her husband, while carrying bread in her apron, the food was turned into roses. Since this occurred in January, Denis reportedly had no response and let his wife continue.

Elizabeth would serve as intermediary between her husband and Afonso, during the Civil War between 1322 and 1324. The Infante greatly resented the king, whom he accused of favoring the king's illegitimate son, Afonso Sanches. Denis was prevented from killing his son through the intervention of the Queen, when she, in 1323, mounted on a mule, positioned herself between both opposing armies on the field of Alvalade in order to prevent the combat. Peace returned in 1324, once the illegitimate son was sent into exile, and the Infante swore loyalty to the king.

In 1325, after the death of her spouse, she retired to the monastery of the Poor Clare nuns, now known as the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha in Coimbra, and entered the Third Order of St. Francis, devoting the rest of her life to the poor and sick in obscurity. During the great famine in 1293, she donated flour from her cellars to the starving in Coimbra. She was also known for being modest in her dress and humble in conversation, for providing lodging for pilgrims, distributing small gifts, paying the dowries of poor girls, and educating the children of poor nobles.

She was a benefactor of various hospitals (Coimbra, Santarém and Leiria) and of religious projects, such as the Trinity Convent in Lisbon, chapels in Leiria and Óbidos, and the cloister in Alcobaça.

She died on July 4, 1336 on her way to Estremoz Castle, where she was supposed to settle a family quarrel. She was called to act once more as a peacemaker, when Afonso IV marched his troops against King Alfonso XI of Castile, to whom he had married his daughter Maria, and who had neglected and ill-treated her.

In spite of age and weakness, the Queen-dowager insisted on hurrying to Estremoz, where the two kings' armies were drawn up. She again stopped the fighting and caused terms of peace to be arranged. But the exertion brought on her final illness. As soon as her mission was completed, she took to her bed with a fever from which she died, and earned the title of 'Peacemaker' on account of her efficacy in solving disputes.

Elizabeth was beatified in 1526 and canonized a saint by Pope Urban VIII on May 25, 1625. Her feast is also kept on the Franciscan Calendar of Saints.

Since the establishment in 1819 of the Diocese of San Cristóbal de La Laguna (Canary Islands, Spain), Saint Elizabeth is the co-patron of the diocese and of its cathedral pursuant to the papal bull issued by Pope Pius VII.

#random stuff#catholic#catholic saints#franciscans#elizabeth of portugal#isabel de portugal#isabel de aragón

1 note

·

View note

Text

Top 10 Attractions to do in Coimbra Portugal in 2024

Explore the top 10 must-visit attractions in Coimbra that make this city a unique and fascinating destination. From the charming Portugal dos Pequenitos, perfect for family outings, to the serene Santa Clara Monastery Velha and the majestic Se Velha, Coimbra is a history and beauty treasure trove. Discover Coimbra University, one of Europe’s oldest and most prestigious institutions, and marvel at…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Day 46 Walking the hills of Coimbra

Today I eagerly awaited the delivery of the breakfast bread that is mentioned in most of the reviews for my B&B! It arrived at the promised time of 8.15 and did not disappoint. Two different white crusty, fresh bread rolls. I ate both, one with scrambled eggs (with cottage cheese, thank you Rosie, they fluffed up amazingly in the microwave) and the other with goats cheese and mushrooms once I found the manual in English for the Ikea induction cooktop.

Leaving earlier than required for the 2.5 hour walking tour, I meandered through the grounds of the university and down, down, down the hill, taking lots of pictures and ducking into shops.

One of the shops had Anne Taintor images on shopping bags along with other similarly hilarious vintage images and humour and I laughed out loud a few times and had a great conversation with the shop owner who has Anne's permission to print her work.

Anyway back to the tour. José was very informative, a former pharmacist who couldn't stop mentioning he graduated from Coimbra University (and climbed the stairs twice everyday and now goes around them!). José confirmed that the students don't actually wear their capes all the time, only during 'O' week when the fourth years play pranks on the first years and the ones in uniforms on the streets are students selling postcards!

After some delicious freshly made sushi for lunch I head back to Nau Coffee for a large oat milk latte pick me up and an informative conversation with one of the workers about the Bienal. She highly recommended the main venue at The Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Nova and not to miss the “well”beside the lemonade stand at the bar.

The monastery was built to replace the mediaeval Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha, located nearby, which at the time was prone to frequent flooding by the waters of the Mondego river.

Decision made, Bienal instead of tickets to the University Library, Museum etc. I decided to walk the streets beside the main area and stumble across José's recommended gelateria DOPPO. So many decisions! I ask for the pear cinnamon & cardamon and ricotta & caramelised fig (they're out of the first one, oh no!). I sought advice, chocolate and orange, done and delicious with the ricotta & caramelised fig.

I head over the river in the misty rain, went to the wrong building (Saint Francis Convent), so keep going up the hill.

The theme of the Bienal is The Phantom of Liberty. The art is spread across this massive space, inside and out. What was of most interest to me was the use of the space. The monastery was built in the 17th & 18th centuries, the structure is solid but shows its age. The art / installations were not the best I'd experienced (but were a cut above the Portaloo installation I attended on my second honeymoon with Andrew and two of his adult children in Hamburg. That one cost €6 each, today it was free!). I'll let the separate post of photos and videos speak for my experience.

I head back over the river, in more misty rain, to attend the free Fado at Café Santa Cruz (a former chapel built in the 1500s). The setting is fabulous with two endearing serious older gentleman serving. I order a beer with currant, not what I expected, it's more like a raspberry beer (think raspberry lemonade), it's passable. I had intended to video some of the performance (in Coimbra it's tradition that only men sing Fado) except I was joined by a couple from Bristol and we got talking about our travels and I missed half of the performance 🥴😂

More misty rain. I'm done for the day. Back up the hill to the B&B via José's recommended chocolate shop. It's expensive, 57 grams (including the paper bag and sticker) of chocolate with pistachio and sea salt cost $6.41! I mindfully ate that with my cup of tea 🍫

0 notes

Text

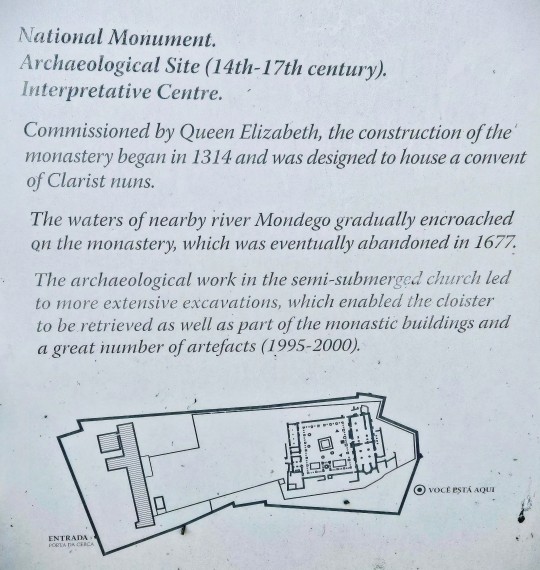

Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Velha, Coimbra, Portugal C14th, abandoned 1677

© optikestrav

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Warm Welcome to Coimbra

If there is a city that I would say I did not do well, this would be it. I think Coimbra and I were a fail. Not entirely. We had a pretty good start....but then....

Then I started to droop.

It was a bajillion degrees after all. Ok, 36C under a blazing, cloudless sky and so humid there should have been rain rather than just liquid air. Coimbra did offer a newly remodeled hotel that allowed me to drop my bags early and cool off with AC. Yes, an actual air conditioning unit in Europe. I nearly cried. Actually, I'm pretty sure a tear squeaked out. Ok, maybe two.

But back to the amazing start. The reason I was so excited to drop off my backpack was because my main attraction in Coimbra was the ruins of a monastery that had been moved to a new location due to flooding: Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Velha. The ruins were across the river, so while I dumped my backpack in the unsecured hotel lobby to lighten my load, I kept my laptop/camera bag with me. As I walked toward the monastery, I eyeballed the clock, running monastery visit duration compared to restaurant hours and dripping a bit more with each step. I finally plopped down in the non-existent shade of a newly planted tree and looked at Google Maps for reviews on all nearby restaurants. No, no, maybe, no, no, ok, best option. Let's try there. NOPE. Across the street.

Where I met another roll-my-eyes-to-the-back-of-my-head amazing plate of food that I stuffed into me: chanfana, old style goat cooked in a clay pot in a wood fire oven. I've had goat before and I would categorize the meat as "I want to enjoy it more than I actually do." Since the chanfana was recommended to me as the specialty of the restaurant and it involved multiple cooking processes, a special pot, and a special oven, I determined if it's that complicated, it has to be good.

Beyond good. I started googling recipes immediately only to realize that my unlimited, backwards -- but free! data speed was going to result in cold chanfana -- or at least 36C chanfana, and I went back to moaning over my gigantic plate of goat, potatoes, and beans that should really have fed two people rather than ending up stuffed into me. But at no point was I leaving any of that (other than the clumps of fat, not my thing) on the plate. I also left the pile of bread the waiter felt I would need to soak up the sauce. Hmmm. Sauce covered bread v. another piece of melt in your mouth goat? Goat.

Finally, I cleared my plate and waddled my full belly over to the monastery. In the back of my head, I knew that while I had downed a bottle of water at the restaurant, the water bottle I had with me was running out. In 36C. I stayed to the shade as much as possible, but knew I was going to have to locate a water source that wasn't the flooded cloisters.

The museum staff was incredibly welcoming. The security guard immediately offered to put my camera/laptop bag into a locker while I was visiting. I confirmed it was ok to take photos and took a last swig of water. I wandered the museum, practicing my religious Portuguese while using Google Translate to help through confusing words. I did one loop through the ruins of the church and flooded cloisters, only to dash back up to the museum to have a private showing of a short documentary on the monastery history. I walked back towards the bathrooms searching for a water source -- hmmm, I could fill up the lid of my water bottle in the bathroom sink and pour it into my water bottle. That's a little too much desperation. Let's search out alternatives.

As I finished off the second floor of the church, I started looking for nearby stores. I was going to be out of water once I picked my bag up and downed the remaining swallows. There was no way I was making it back to the hotel without a refill. I found a petrol station just to the north of the monastery and determined it was the closest option for water. As I headed there, I prayed it had water in the tiny building I could see on Google Maps. If it didn't... I didn't know. I didn't have a plan.

I cut across the drive to the tiny shop, searching desperately for water. GOAL!!!!!!! I made a mad rush inside, found a gigantic bottle in a refrigerator that was twenty cents more than the room temperature version (DON'T CARE), paid, and cracked open the cap, immediately starting to down the water as I walked over to a shaded short wall. I gulped down a quarter of the bottle, regaining confidence that I wasn't about to die in Coimbra. I refilled the water bottle in my bag and kept the remaining amount of water out so I could continue to gulp it down as I set back across the unshaded bridge.

I could finally check in to the hotel where I would learn about the AC and weep from joy. I collapsed into the bed, stretched out under the AC trying to recover. I made grateful mental notes about my trip. I had been worried that the heat in Portugal was going to make this trip zero fun. I researched temperatures as I was booking things, and thought they were all pretty mild, but as an over-adapted Phoenician, my scale is a bit skewed and missing the humidity factor. Now in country, I realized that by sticking to the coast for most of my trip, I had managed to avoid the excessive heat that builds inland. Other than Lisbon and Évora, Coimbra was the furthest away from the coast I was going. All I had to do was survive my time in Coimbra, and I could get back to cooler temperatures in Aveiro. All would be fine.

Gelato. There's gotta be gelato here. Let's change into lighter clothes (Nazaré was downright frigid compared to Coimbra) and go find gelato.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha in Coimbra, Portugal Coimbra is one of the oldest cities in Portugal. Home to the most prestigious university in the country, it served as the first capital of the Kingdom of Portugal and has had a strong monastic presence ever since. Across the river from the main part of town stands the ruined Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha. Originally founded by Lady Mor in the late 13th century, it became a favorite of Queen Elizabeth of Portugal, who built her palace next door. The monastery operated until the early 17th century, when flooding from the Mondego River forced the nuns to move uphill and leave the monastery. And there it sat for 300 years, until it was excavated in the late 20th century. Santa Clara-a-Velha is most famous for being the execution site for Ines de Castro. In 1340, King Afonso IV arranged the marriage between his son Pedro and Constanza Manuel of Castille. Much to Afonso's displeasure, Pedro fell madly in love with Constanza's cousin Ines, and installed her in Coimbra as his mistress. Constanza gave birth to a son and heir to the throne, but after she died in 1349, Pedro refused to marry any other woman except Ines. Fearing her influence on Pedro and any future sons they might have, in 1355 Afonso had Ines murdered in the Santa Clara-a-Velha monastery. Pedro had her killers brutally executed, and when Afonso died and Pedro became king, the legend goes that he had Ines' body exhumed and coronated as Queen. Today, Pedro and Ines are buried together in nearby Alcobaca, but their story has become one of the most well-known tragedies in Portuguese history. As for the monastery itself, it still experiences flooding every now and then, but visitors are now able to access the lower floors of the old monastery, including the choir and old treasury. Santa Clara-a-Velha remains one of the most complete and historically important Gothic ruins in the entire country. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/monastery-of-santa-clara-a-velha

0 notes

Text

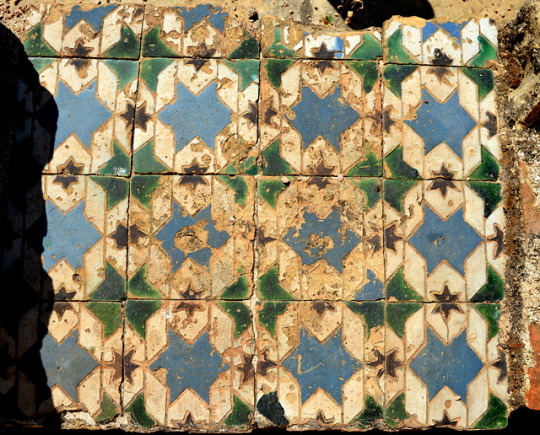

Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Velha, Coimbra, Portugal

#monastery#mosteiro de santa clara a velha#Coimbra#Coimbra Portugal#Portugal#santa clara a velha#santa clara#archaeology#church#photography#mine#personal

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Velha e Universidade de Coimbra #universidadedecoimbra #uc #coimbra #portugal #igersportugal #worldheritage #patrimoniomundial #unesco #instatravel #travel #viagem #turismo #visitportugal #ptpatrimonios #portugalpatrimonios #walkabout https://www.instagram.com/p/CTpCsiNlDY6/?utm_medium=tumblr

#universidadedecoimbra#uc#coimbra#portugal#igersportugal#worldheritage#patrimoniomundial#unesco#instatravel#travel#viagem#turismo#visitportugal#ptpatrimonios#portugalpatrimonios#walkabout

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝑽𝑰𝑶𝑳𝑬𝑵𝑻 𝑫𝑬𝑳𝑰𝑮𝑯𝑻𝑺.

“Does it burn you, too?” She breathed against his flushed lips. “This flame we are inventing?”

post type : self-paragraph.

word count : 2,911.

mentions of : religious devotion, illicit romance.

brief mentions of @joannaofportugal

“If the Bishop is dead, then who will be left to give him a Christian burial?”

There was no doubting that Abbot Antunyes’ death left a darkened cloud to linger over the Monastery of Santa Clara a Velha, and yet there was much preparation at hand to make way for the new Abbot, Father Henriques, who rode from Lisbon to fill his late predecessor’s role. Sister María’s look darkened to a glower as she knelt before Carolina and gathered a clump of soil in her hands, staining the dark sable of her habit in soot. This was the first inkling Carolina had been made aware of that things were going to be different from now on. Antunyes, who had prostrated himself before the royal purse and groveled before the crown, was dead.

“The monks will tend to him,” María explained, a hand lifting to wipe her brow and leaving a smear of dirt behind. “Come, Sister, your youth is invaluable.”

Her head spinning with speculation, the Infanta fell to her knees and dug her hands into the cool earth, digging the spot where Antunyes would be laid to rest. She worked like a broken puppet, movements rathe and uncoordinated, lumps of both clay and rock thrown haphazardly over her shoulder. She did not resist as Sister María instructed for her to hasten, a silent prayer lingering upon the crackled oxbow of her lips all the while.

In truth, Antunyes, aged and addled with gout and weakened with arthritis as he was, was more powerful dead than he was alive. Tales of the Christian people of Coimbra flocking to the late Father’s cathedral to smear themselves with the blood of their holy prelate, or to snip pieces from his bloodstained vestments as relics, traveled across the length and breadth of Iberia. Young and potent and charismatic though he was, Henriques would have a mighty role to double as. Soon, the townsfolk –– many of them who had only ever known one bishop to come to with their troubles throughout their lives –– would make claims that miracles had been taking place at Antunyes’ tomb.

Carolina pressed both hands into the ground, stretched across the courtyard low enough that her nose was nearly flush with the dirt, as a frigid trickle of sweat fell from the tip of her nose into the weeds that lay flat beneath the soil. What a sorrowful tomb it was, she mused, a wooden box lined with muslin, shoved into the ground without a Bishop to bless it. Though perhaps that had been Antunyes’ final wish: as unremarkable and ghastly as his resting place was, was that not where the majority of miracles were known to take root?

The Infanta gripped the rosary slung from her throat with muddied hands, another cold gust of wind stabbing sharply at her lungs.

“That will be well enough for the gravediggers. I will request a warm basin to be brought to your chamber.”

Three days after Antunyes had breathed his last, Henriques had still not arrived –– and yet Carolina’s mind was consumed by a missive that arrived from the Palace, inscribed by her mother’s own hand. She ran her fingertips across her mother’s decorative script, signed Crara the Quene, and brought the slip of parchment to her nose, breathing in its smell of leather and wax deeply. Her mother wrote of the triumph of the Lisbon Summit, and of her abiding longing for her two youngest daughters. Carolina had longed to attend the pageantry, and yet with the presence of so many conspiring guests, it was advised that she be sent someplace where she’d be safe.

Glancing around the lusterless, gray chamber, carved of slanted ceilings and stone walls, she released a careworn sigh. With what little stipends she was bequeathed by the monastery, she’d purchased her own parchment, quill and ink, and set about rejoining her mother without a moment’s notice. It was ironic that the woman who commissioned the great and ancient monastery had been a Portuguese Queen, alike her own mother, often called upon to make peace between warring kings and lords. She’d lived out her dotage under the sisters of Santa Clara’s care, though left no royal accommodations for Carolina and Joanna to relish. Only strict, monastic severity. Brick-hard beds and hearths too small to radiate even the little chamber Carolina had been billeted.

Many of the Infanta’s days were spent by lonesome. If not toiling away at duties –– which included farm-work, providing alms and fare to the poor, care of the sick, and education to boys being reared in the local church –– or indulging in rare moments where she could see her sister (for they were often instructed to remain silent and joyless as they passed one another in the corridors) there was a sense of distressing loneliness housed in her breast. Shut away from the world as they were, there was no shame in the humility that had overcome her livelihood. Required to wear, on some days, rough robes of sackcloth that had been smeared from ashes from a fire, in penitence for the world’s terrible sins, there was nothing, in the eyes of the sisters, that could ever truly expiate it.

Carolina reminded herself that she must simply go through the motions, and that she would join her mother and father and sisters’ at their sides soon. Monastic life was meant to be a gift, a test of both fortitude of piety and character, and if the grandmothers who had come before her could endure and resist the temptation to shatter, she would, too. She need only concern herself if Joanna could survive it all.

She thought it was a great pity that she could not, for a single moment, slip into the role of one of the Portuguese lords who had seen her mother coronated. The sight of her refined, majestic mother in her silk gown and gold coronet, enthroned in the Jeronimos Monastery, would have surely gladdened her morose heart and filled her imagination with splendour and wonder. She touched the limestone walls, the frosted over windows, the arch of the hearth, the worse-for-wear floorboards, the wooden door that creaked as she caressed it with the palm of her hand, as if to absorb the religious asceticism thrumming through the walls.

Yet, it was at that self-same moment that the hinges of the door gave, and rusted nails poured down upon Carolina’s gilded head as the door fell forward, and she tumbled after it. Prostrated on the floor, on her hands and knees before the black robes of a monk who’d passed by and now stood over her. “Sister Carolina –– do swear it to me you were not meaning to escape. You have all the subtlety of a circus cavalcade.”

The Infanta reached forth to grasp the hand of the monk who lifted her to her feet. “Brother Lourenço.” She shook her head, now acutely aware of her exposed hair, “no –– no. To escape religious order is to run headfirst...”

“...into Hell,” he larked in unison. “You’ve listened well to Father Antunyes’ teachings. God rest his soul.” Lourenço made the sign of the cross upon his chest. As he did so, Carolina worried at her fingertips, praying to the God that the floorboards swallow her whole or, for all her sins, por favor Deus, bestow upon her a reasonable excuse for her trespasses.

“The fire,” she suddenly sputtered, “the fire in my room extinguished. Please, if you could spare me another pile of wood I–I am like to catch a chill without it.”

His head canted thoughtfully, the morning sun illuminating the deep hollow of his cheek. “Very well. Come with me, sister.”

As they treaded the winding corridors of the monastery, they spoke of much –– of the palace and court in Lisbon, which Brother Lourenço took an acute, albeit distanced interest in; of his religious vows, upbringing and forays at a university in France; of his journeys from Calais to Dover, and as he remembered the choir that sang for her uncle King Edward in London, he smiled, turning to her and bestowing a compliment upon the rosary that laid flat on her chest. The sun had shined its magnificent glister upon the rubies encrusted within the crucifix she piously donned, reflecting upon the Infanta’s silvery skin –– reddened with unbidden flush.

She found that he was not without humour, either, and as he hit his head against the ceiling of her hearth as he lit another log to burn, they two dissolved into fits of laughter that trembled the walls of the gravely quiet monastery. It was not until several moments later that Brother Lourenço slipped away, promising her that he would continue to share more stories with her, more remembrances, leaving her with a throat that ached from laughter and a belly that panged with something indescribable. Somehow, in his wake, the chamber, now warmed with a merry fire, felt evermore lonesome.

Almost a week had past since Father Antunyes had died and been buried, now resting in the hill covered with earth that Carolina could see faintly from the vantage of her window. Spring was thawing into a humid summer, and soon a meadow would sprout and surround Antunyes’ meek headstone. Carolina knelt her head against the window as the brother’s haunting ensemble reverberated from the cloister below. The soulful chants of Deus misertus hominis echoed across the grounds, and the glass-pane of her windows seemed to quiver in response.

When nightfall blanketed the monastery, Carolina hastened after Sister María to engage in her devotionals. Ushered beneath the stone arches of the accompanying church, the sisters stripped of their gossamer veils and their shoes and their cloaks, and left only in their humble habits, Carolina could easily see her sister Joanna’s unmistakably fiery locks from across the assembly of pews. She silently fell before the altar and touched her cheek against the damp floor, breathing in the sweat and tears of the sisters. As she exited, she dusted her fingertips against the marble tomb of the Queen who’d commissioned the monastery –– perhaps a distant grandmother, or aunt, to the Infant –– and fell into step behind a throng of nuns. They stood beneath the arches of the church for what felt like hours to await the passing of the rains. Carolina’s hair was wizened with humidity by the time the now familiar pitter-patter of raindrops had ended, and yet the wait had seemed, in her eyes, well-worth it, for as she passed the cloister, allowed her toes to sink into the wet grass and become muddied and slick, she caught sight of Brother Lourenço. He winked at her (his eyes were fearsomely blue) and brought a single digit to his lips, as if to say, quiet now. You enter God’s house.

The next she saw of him was at a feast to (cautiously) celebrate Henriques’ impending arrival. As summer approached, the earth had warmed and become wet, and the Father’s travels were delayed by a fortnight. The sisters feasted upon ale and fish and each were given a slice of sweetened bread to break in the privacy of their chambers. Carolina picked at the red and purple berries embedded into the roll, and rolled hers in a snip of linen as she waltzed from the refectory with a belly full and cheerful. The skies were irritated with stars and the breeze was hot as she meandered the rectangular perimeter of the cloister, the mild airs caressing against her skin like the Almighty’s own touch. It brought an instant flush to her face, a glean to her forehead, appearing even beneath the veil she wore. Summer was here, which meant her time under the strict care of the monastery was coming to an unhurried end.

“Sister Carolina.”

It was his voice. She would have recognised it anywhere. The Infanta turned round to meet him, gesturing between the two linen wraps in their hands. “Is the bread any good?”

“After a while here,” he approached her, a smile slanting his lips, “any deviation from mead and fish is welcome.”

“It would be a great pity to break our bread by lonesome, then, Brother. How often does one celebrate the changing-of-hands of a monastery?”

“A great pity.” His smile brightened into a gleam, teeth on full-display. “Come with me to the river. I’ll show you my place of solace.”

Thank God Father Antunyes was dead, for while he had been alive, it would have been impossible for her to slip or sneak away under his hawkish, but well-intentioned gaze, even under the cloak of nightfall. Together, they sat beside the current of the Mondego river and broke their bread over rapidly flowing conversation. The river stank of brine and wet wool, but the night was pleasant. “I believe Father Antunyes’ words to be true,” she said after some silence had descended, “there is no godliness beyond these walls. In Lisbon, I mean, there are bishops as there is here, there are good men and women as there are here, and there is prayer and sacrifice, but it is...”

“A farce.”

“Yes, a farce. Merely a way to preserve the favour of God and country. There is no deeper sense of devotion. It is as shallow as...” Her hand wafted over the river’s gentle ripples, “as the bank of a stream.”

“That is why I left France,” he shared, “though I was a man of the cloth there as I am here, there was no one to share my fervor. I was anticipated to use my piety as a bargaining tool for brokering the late king’s favour. I could not fathom it. I had no option but to embrace order and tradition.”

“Is it true Father Henriques is dead?” Carolina wondered aloud.

Lourenço barked out in laughter at that, prying: “why would you ask that?”

“He is not here, and there has been no word or dispatch of news of his travels.” Her shoulders lifted into a shrug, “it is merely a suspicion...”

“A suspicion brought on by years of exposure to the viperous court of Lisbon,” he counseled, brushing a stray ringlet of hair from Carolina’s throat. She inhaled a sharp gust of air, whistling between her lips. Yet, as if on cue, pounding horse hooves alerted her to the arrival of newcomers to the monastery. From a distance, she could see the glow of torches lighting up the monastery’s entrance, and the coat-of-arms of the Braganza family rippling from a banner that hung like the gardens of Babylon from the intruders’ steeds.

“It is him,” She breathed, clambering to her feet, “it is Father Henriques. Quick, quick, we must go to greet him! I believe he will have brought me word from my mother, the Queen. Help me out of this muck.”

Lourenço rose to stand beside her, and for perhaps a first, she took into account his height. He loomed above her, all sharp angles, save for the little dip in the cleft of his chin, the curl of his hair around his forehead, falling in a middle part around his face, framing dark eyes, a crooked nose, mischievous lips.

He was not handsome, no –– older, too –– but fascinating. “Sister...”

“What?” She snapped. “I must go. Perhaps she means to send me back with his men. Perhaps they will bring Joanna and I back to Lisbon.”

“If you are to go, then give me this.” He joined their hands together and she accepted the touch readily, if not impatiently. Must he do this now? Now, when she could very well be readying her belongings for travel?

It had to be destiny, of this Carolina was certain. She was filled with a sense of it, coupled with the ardent presence of elation. God had led this man, this holy, embittered man, to cross her path; this man who had the power to strip her of her apprehensions, her misgivings and resentments, just as he held the ability to satisfy her longing for another’s presence, a man’s touch. He was wearing the same habit she had met him in, but he smelled of herbs and the river’s salinity and something uniquely fresh, clinging to his flesh as her hands clung to his. He crushed his lips to her forehead, urgent and as sweet as a plum. She took it upon herself to rise onto her tiptoes and bring their lips together, moving in fervent unison. Not a first kiss, but the first to cause her belly to feel molten, alive like the volcano that had covered Pompeii in fire and ash.

Lourenço’s strong arms folded around her, bringing her closer to his chest, as his fingers, rough with manual labour, tugged at her veil until it loosened and her blonde hair surged freely down her spine. She gave like-for-like in return, relishing him with the little flickers of her tongue, her mouth opening to his, exciting him with her hands at his shoulders, steadying herself, until he could bear it no more and broke loose of her spell.

“Does it burn you, too?” She breathed against his flushed lips. “This flame we are inventing?”

It was hours before she slept, and days before she set eyes upon Lourenço again. No longer did she call him Brother Lourenço, for he was something more in the eyes of Christ –– he was an amour. Or, at least, he might have been, had Father Henriques not handed her a letter that sealed her fate as the future Countess of Ourem. Her father had bargained well, and she was to be married.

#iiiiii ran out of steam so#it ends there#( 𝗌𝖾𝗎 𝖺𝗆𝗈𝗋 𝗂𝗇𝖿𝗂𝖾𝗅 É 𝖺 Ú𝗇𝗂𝖼𝖺 𝖿𝖺𝗋𝗌𝖺 𝖾𝗆 𝗊𝗎𝖾 𝖺𝖼𝗋𝖾𝖽𝗂𝗍𝗈. ) / * HEADCANNONS .

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

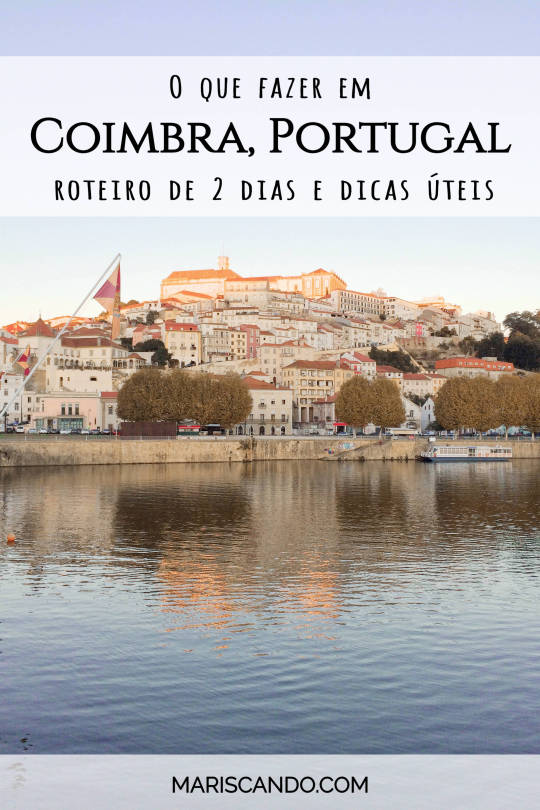

O que fazer em Coimbra: roteiro de 2 dias e dicas úteis

Esse mês faz 4 anos que eu me mudei para Portugal para fazer mestrado na Universidade de Coimbra. Para marcar essa data, resolvi finalmente escrever o roteiro pela “capital do amor em Portugal”, que estou devendo aqui no blog há pelos menos uns 3 anos. Ahhh, saudosa Coimbra! Só de rever as fotos para escrever esse post, meu coração já se encheu de nostalgia daqueles bons tempos de estudante...

Coimbra é uma cidade no Centro de Portugal, localizada às margens do rio Mondego. É a antiga capital do país e guarda um patrimônio riquíssimo de diversos períodos históricos. Ainda hoje, é considerada uma das mais importantes cidades portuguesas, devido à concentração de infraestruturas, serviços e comércio, além de sua privilegiada posição geográfica, bem no meio de Portugal continental.

Coimbra é, em sua essência, uma verdadeira cidade universitária! A Universidade, fundada em 1290 em Leiria, veio a se fixar definitivamente no antigo palácio real em 1537, de onde nunca mais saiu. Em 2013, o conjunto edificado da Universidade foi declarado Patrimônio Mundial da Humanidade pela UNESCO. Hoje a Universidade possui cerca de 25 mil estudantes, com uma das maiores comunidades de estudantes internacionais do mundo. Imaginem só a honra que foi poder estudar num lugar desses!

Esse roteiro é baseado no percurso básico que eu costumava fazer com os amigos e familiares que me visitaram enquanto eu morei em Coimbra. É claro que dois dias são muito pouco para conhecer todos os encantos dessa linda cidade universitária. Ainda assim, para quem tem pouco tempo ou está pensando em incluir Coimbra num roteiro de vários dias por Portugal, dois dias são suficientes para ter uma boa noção da história e do riquíssimo patrimônio dessa joia no centro de Portugal. Então aqui vamos nós!

Dia 1 - Universidade, Alta e Santa Clara

Para quem tiver apenas um dia disponível para conhecer Coimbra, esse é dia é o roteiro básico para ter um gostinho das principais atrações da cidade! Comece o dia indo diretamente à Alta da cidade para conhecer os edifícios mais antigos da Universidade de Coimbra. Se for subir pelo (1) Elevador do Mercado, aproveite para curtir a vista para as casinhas coloridas do outro lado do vale. Se não, também pode chegar até lá em cima de ônibus, pegando uma das linhas cujo ponto final fica na Rua Larga da Universidade.

A bilheteria da Universidade fica no edifício da (2) Biblioteca Geral, de onde você já pode se dirigir ao Paço das Escolas, passando pela imponente (3) Porta Férrea. O ingresso para o complexo da Universidade dá direito à entrada no circuito principal que contém o (4) Paço Real, (5) Capela de São Miguel e a (6) Biblioteca Joanina. O ingresso também dá direito ao Museu de Ciências, mas indico que só visite esse último se tiver mais dias livres na cidade para fazer o restante dos programa depois. Pra quem quiser se aprofundar nessa visita, tem um post todinho dedicado a essas atrações aqui no blog.

Depois de conhecer a Universidade, desça rumo à Baixa da Cidade, seguindo pelas escadarias da Rua do Norte e passando pela lindíssima (7) Sé Velha, uma das igrejas de estilo românico mais icônicas de Portugal. Siga descendo até a rua do (8) Quebra-Costas, onde o largo se abre como o coração da parte mais antiga da cidade. Lá você irá entender o porquê deste nome e de eu ter sugerido começar o roteiro à pé pela parte alta e não o contrário!

Se já estiver com fome, os bares e pequenos restaurantes dessa área são uma excelente pedida para saborear umas belas tapas portuguesas. Nesse post aqui eu dei algumas dicas de lugares bons para comer e beber em Coimbra. No largo do Quebra-Costas fica também um dos remanescentes da antiga muralha de Coimbra: a (9) Torre de Almedina. Essa torre marcava a entrada principal da antiga cidade medieval e suas fundações remontam à época de ocupação islâmica de Coimbra.

Atravessando o Arco da Almedina e a (10) Porta de Barbacã rumo à Baixa, você chegará à rua mais movimentada do centro antigo de Coimbra, a (11) Rua Ferreira Borges. Se gosta de fazer compras, vai encontrar ali de souvenires e presentes, até algumas lojas de produtos típicos portugueses. Virando à esquerda, pode seguir a rua até o (12) Largo da Portagem, onde já pode ser uma boa ideia fazer uma pausa para um café ou um pastel de Santa Clara, na Pastelaria Briosa.

Se for um dia de verão ou o tempo estiver favorável, vale muito a pena dar um passeio pelo (13) Parque Verde do Mondego, na beira do rio que corta a cidade. A (14) Ponte Pedonal Pedro e Inês já virou um dos cartões postais de Coimbra e de lá tem-se algumas das vistas mais bonitas para a colina da Alta da cidade.

Por fim, termine o dia visitando o lindíssimo (15) Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Velha, cuja entrada para o complexo de ruínas e museu fica na Rua Parreiras e não na avenida principal. Se não quiser fazer a visita completa das ruínas, também pode apreciar uma vista para o antigo mosteiro do lado de fora, próximo à Ponte de Santa Clara.

Quem ainda tiver pique e quiser um bom local para curtir o pôr-do-sol com uns bons drinks, vale a pena subir para visitar o Passaporte Lounge Terrace, com uma vista deslumbrante sobre o rio Mondego.

Dia 2 - Machado de Castro, Jardins e Baixa

Comece mais um dia indo à Alta da cidade para visitar o espetacular (1) Museu Nacional de Machado de Castro. Além da riquíssima coleção de peças históricas de seu acervo, o museu está localizado no coração de Coimbra, em um lugar carregado de simbologias e significados diversos, com mais de 2000 anos de história e pelo menos 23 camadas arqueológicas! Vale muito a pena a visita para quem quer conhecer melhor a história dessa cidade incrível.

Não deixe de conferir também a belíssima (2) Sé Nova, a igreja do século XVIII que fica logo ali ao lado do museu. Depois, dirija-se à Rua Larga, onde estão os edifícios universitários da época do Estado Novo em Portugal. Passando pela (3) Estátua de Dom Dinis, desça pela parte posterior da colina, aproveitando para conhecer também as (4) Escadarias Monumentais desse conjunto construído entre os anos de 1940 e 1960. Se for período de aulas, aproveite para acompanhar o burburinho dos estudantes com suas longas capas pretas, que sobrem e descem as escadarias na hora do almoço ou procuram um lugar ao sol para descansar entre as aulas.

Almoce na região da (5) Praça da República, onde os preços são bem amigáveis do que na parte mais turística do centro e os descontos para estudantes estão por toda a parte. Se quiser, dê uma esticadinha até o (6) Jardim da Sereia ou vá passear no bucólico (7) Jardim Botânico da Universidade, para uma boa caminhada digestiva.

À tarde, desça pela (8) Avenida Sá da Bandeira para explorar um pouco mais da Baixa de Coimbra. Passe pelo (9) Jardim da Manga e não deixe de visitar a (10) Igreja de Santa Cruz, um belíssimo exemplar da arquitetura medieval portuguesa. Depois, caminhe pela (11) Rua da Sofia, para conhecer os antigos colégios da Universidade, antes da transferência para a Alta da cidade.

Termine o dia explorando e se perdendo pelas as vielas da Baixa de Coimbra. Se quiser experimentar mais algumas delícias da gastronomia local e ainda ouvir um pouco do tradicional fado de Coimbra, passe uma noitada no Bar Diligência, onde a comida e a música lhe deixarão ótimas lembranças dessa cidade tão especial. ~MV

Encontre sua Hospedagem em Coimbra

Booking.com (function(d, sc, u) { var s = d.createElement(sc), p = d.getElementsByTagName(sc)[0]; s.type = 'text/javascript'; s.async = true; s.src = u + '?v=' + (+new Date()); p.parentNode.insertBefore(s,p); })(document, 'script', '//cf.bstatic.com/static/affiliate_base/js/flexiproduct.js');

Blogagem Coletiva

Este post faz parte de uma ~Blogagem Coletiva~ realizada pelo grupo Viajando por Escrito, com o tema “O que fazer em...”. Leia também os outros posts do grupo:

+ Experiência Barbara > O que fazer na Avenida Paulista + Viajante Econômica > O que fazer em Barcelona + Viagens e Feminices > O que fazer no Centro Histórico de São Paulo + Se joga no roteiro > Cinco cidades no interior de São Paulo para um final de semana + Classe turista > O que fazer em Santiago com crianças? 11 atrações imperdíveis!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inês de Castro, Queen of Portugal (posthumous), (Wife of King Pedro I of Portugal

Inês de Castro (1325 – 7 January 1355 in Coimbra) was a Galician noblewoman best known as lover and posthumously-recognized wife of King Pedro I of Portugal. The dramatic circumstances of her relationship with Pedro (at the time Prince of Portugal), which was forbidden by his father King Afonso IV, her murder at the orders of Afonso, Pedro's bloody revenge on her killers, and the legend of the coronation of her exhumed corpse by Pedro, have made Inês de Castro a frequent subject of art, music, and drama through the ages.

Inês was the natural daughter of Pedro Fernández de Castro, Lord of Lemos and Sarria, and his noble Portuguese mistress Aldonça Lourenço de Valadares. Her family descended both from the Galician and Portuguese nobilities. She was also well connected to the Castilian royal family, by illegitimate descent. Her stepmother was Infanta Beatriz of Portugal, the youngest daughter of Afonso of Portugal, Lord of Portalegre and Violante Manuel. Her grandmother was Violante Sánchez de Castile, Lady of Uzero, the illegitimate daughter of Sancho IV of Castile. Her great-great grandfather was Rodrigo Alfonso de León, Lord of Aliger, the illegitimate son of Afonso IX of León. She was also legitimately descended from Infanta Sancha Henriques of Portugal, the daughter of Henry, Count of Portugal.

Inês came to Portugal in 1340 as a maid of Constança of Castile, recently married to Pedro, the heir apparent to the Portuguese throne. The prince fell in love with her and started to neglect his lawful wife, endangering the already feeble relations with Castile. Moreover, Pedro's love for Inês brought the exiled Castilian nobility very close to power, with Inês's brothers becoming the prince's friends and trusted advisers. King Afonso IV of Portugal, Pedro's father, disliked Inês's influence on his son and waited for their mutual infatuation to wear off, but it did not.

Constança of Castile died in 1345. Afonso IV tried several times to arrange for his son to be remarried, but Pedro refused to take a wife other than Inês, who was not deemed eligible to be queen. Pedro's legitimate son, future King Fernando I of Portugal, was a frail child, whereas Pedro and Inês's illegitimate children were thriving; this created even more discomfort among the Portuguese nobles, who feared the increasing Castilian influence over Pedro. Afonso IV banished Inês from the court after Constança's death, but Pedro remained with her declaring her as his true love. After several attempts to keep the lovers apart, Afonso IV ordered Inês's death. Pêro Coelho, Álvaro Gonçalves, and Diogo Lopes Pacheco went to the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Velha in Coimbra, where Inês was detained, and killed her, decapitating her in front of her small child. When Pedro heard of this he sought out the killers and managed to capture two of them in 1361. He executed them publicly, ripping their hearts out claiming they didn't have one after having pulverized his own heart.

Pedro became king of Portugal in 1357 (Pedro I of Portugal). He then stated that he had secretly married Inês, who was consequently the lawful queen, although his word was, and still is, the only proof of the marriage.

During the 1383–85 Crisis of royal succession in Portugal, João das Regras

produced evidence that allegedly established that Pope Innocent IV had refused Pedro's request to recognize his marriage to Inês and legitimize his children by her, the elder of whom, João, Duke of Valencia de Campos

would have a strong potential claim to the throne of Portugal. By negating these children's claimed legitimacy, João das Regras strengthened the claim of another illegitimate child of Pedro I of Portugal: João, Master of Aviz, who ultimately took the throne and ruled as João I of Portugal.

Some sources say that after Pedro became king of Portugal, he had Inês' body exhumed from her grave and forced the entire court to swear allegiance to their new queen: "The king [Pedro] caused the body of his beloved Inês to be disinterred, and placed on a throne, adorned with the diadem and royal robes. and required all the nobility of the kingdom to approach and kiss the hem of her garment, rendering her when dead that homage which she had not received in her life..."

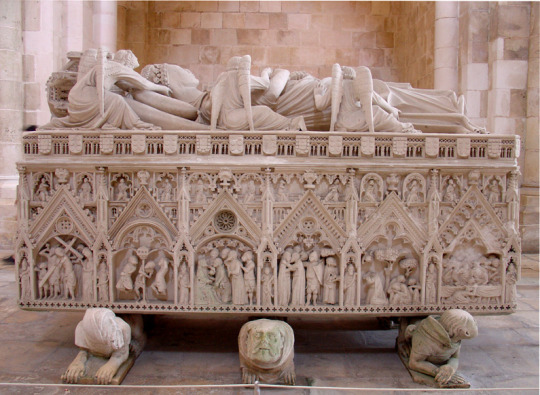

Some modern sources characterize the story of the Inês' post-mortem coronation is a "legend." and it is most likely a myth, since the story only appeared in 1577 in Jerónimo Bermúdez' play Nise Laureada. She was later buried at the Monastery of Alcobaça where her coffin can still be seen, opposite Pedro's so that, according to the legend, at the Last Judgment Pedro and Inês can look at each other as they rise from their graves. (which is also not true since the tombs already were in different positions before). Both marble coffins are exquisitely sculpted with scenes from their lives and a promise by Pedro that they would be together até ao fim do mundo (until the end of the world).

Inês de Castro and Pedro I had the following children, who were legitimized by Pedro I on 19 March 1361:

Afonso, died shortly after birth.

Beatriz (1347-1381), married Sancho Alfonso, 1st Count of Alburquerque and was thereby the great-grandmother of Fernando II of Aragon.

João (1349-1387), Duke of Valencia de Campos, claimant to the throne during the 1383–85 Crisis.

Dinis (1354-1397), Lord of Cifuentes, claimant to the throne during the 1383–1385 Crisis.

Inês de Castro's story is immortalized in several plays and poems in Portuguese, such as The Lusíadas by Luís de Camões (canto iii, stanzas 118-135), and Spanish, such as Nise lastimosa and Nise laureada (1577) by Jerónimo Bermúdez, Reinar despues de morir by Luís Vélez de Guevara, as well as by the comtesse de Genlis (Inès de Castro, 1826), and in a play by French playwright Henry de Montherlant called La Reine morte (The Dead Queen). Inês de Castro is a novel by Maria Pilar Queralt del Hierro in Spanish and Portuguese.

Plays written in English include Aphra Behn's Agnes de Castro, or, the Force of Generous Love (1688); and Catharine Trotter Cockburn's Agnes de Castro (1695). Mary Russell Mitford also wrote a drama from the story entitled Inez de Castro.

Felicia Hemans' poem The Coronation of Inez de Castro first appeared in The New Monthly Magazine in 1828.

She is a recurring figure in Ezra Pound's The Cantos. She appears first at the end of Canto III, in the lines Ignez da Castro murdered, and a wall/Here stripped, here made to stand.

There have been over 20 operas and ballets created about Inês de Castro. Operas from the 18th and 19th centuries include:

Ines di Castro by Bernhard Anselm Weber (1790, Hanover)

Ines di Castro by Niccolò Antonio Zingarelli (1798)

Ines de Castro by Walter Savage Landor (1831)

Ines de Castro by Giuseppe Persiani to a libretto by Salvadore Cammarano (1835)

Ines di Castro by Pietro Antonio Coppola (1842, Lisbon)

In modern times, Inês de Castro has continued to inspire operatic works, including:

Ines de Castro by Scottish composer James MacMillan. This work was first performed at the 1996 Edinburgh International Festival

Wut [de] (Rage) in German by Swiss composer Andrea Lorenzo Scartazzini. The world premiere of this work was given at the Theater Erfurt, Germany, on 9 September 2006.

Ines de Castro by American composer Thomas Pasatieri. This work premiered in 1976 with the Baltimore Opera Company.

Ines by Canadian composer James Rolfe. Premiered in 2009 by the Queen of Puddings Music Theatre Company in Toronto.

In addition, Portuguese composer Pedro Camacho (born 1979) composed the Requiem to Inês de Castro, first performed on March 28, 2012 in New Cathedral of Coimbra on the occasion of 650 years of the transportation of Ines de Castro's body from Coimbra to Alcobaça Monastery. Christopher Bochman, with the Lisbon Youth Orchestra, has produced an opera "Corpo E Alma" (Body and Soul) focusing on Pedro's transition from a sensual to a spiritual love following her death, drawing on various aspects of the tale.

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Santa Clara a Velha

Coimbra

Portugal

photos cjmn

72 notes

·

View notes