#Rupicola peruvianus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

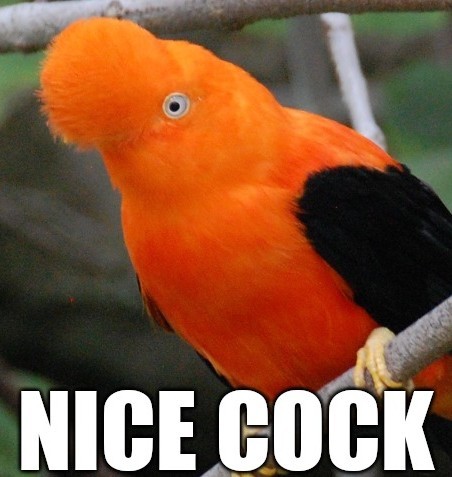

Cock Of The Rock

The Andean Cock-of-the-Rock (Rupicola peruvianus) looking for the ideal spot to preen itself in the Bird Paradise. Photo credit: Jonathan Chua.

This is actually a passerine bird from South America, found in tropical rainforests around rocky outcrops.

#photographers on tumblr#Andean cock-of-the-rock#bird photography#bird pics#flora fauna#lumix photography#panasonic lumix dc-s1#Rupicola peruvianus#sigma 1.4x teleconverter#sigma 150mm macro

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

For @cathartesauraa because your tags made me smile but also for all my dear mutuals (mwah :*) and everyone else who likes birds <3

#birds#shoebill#Balaeniceps rex#great potoo#Nyctibius grandis#andean cock-of-the-rock#Rupicola peruvianus#ok to rb

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

@prudencepaccard Behold this neon phallus cackling sardonically

Ever hear an Andean cock of the rock before? Probably not, or maybe you have and didn't realise it, because they sound quite a bit like a kookaburra!

#birds#video#Andean cock-of-the-rock#tunki#Rupicola peruvianus#cock-of-the-rock#Rupicola#Cotingidae#Tyrannida#tyrannide#Tyranni#Passeriformes#Australaves#Telluraves#Neoaves#Neognathae

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

Andean Cock of the Rock (Rupicola peruvianus), male, family Cotingidae, order Passeriformes, Ecuador,

photograph by Cayce Jehaimi

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Andean Cock of the Rock

The Andean cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola peruvianus), also known as tunki (Quechua), is a large passerine bird of the cotinga family native to Andean cloud forests in South America. It is the national bird of Peru. It has four subspecies and its closest relative is the Guianan cock-of-the-rock.

Photo by:Supreet Sahoo (Tropical Photo Tours) via 500px

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

With hundreds of highly prized species, bird tourism is thriving in the country – and farmers are increasingly turning their land into nature reserves

“Wildlife tourism is far more profitable than farming but that’s not the only reason we made the change,” says Ajila’s son, Luis Jr. “We wanted to save not just the umbrellabird, but all the special creatures here, and safeguard them for future generations.”

Projects such as this are eligible for funding from the Ecuadorian government. Launched in 2008, the Socio Bosque scheme offers “the poorest private and communal forest landowners annual payments for each hectare of forest cover maintained”, with sums of between $30 (£23) and $60 a hectare.

The Ajila family: Luis Jr, Alejandra and Luis Sr. Photograph: Dr Stephen Moss

But the income provided by birders alone has been enough to propel some farmers to take up the nature reserve model.A few years ago, Favián Luna decided to convert his 120-hectare tomato farm in the Tandayapa Valley, north-west of Quito, into a cloud-forest reserve and lodge called Alambi Reserve. Visitors go to photograph many species of hummingbirds, including the Andean emerald, native to the Chocó bioregion of the Ecuadorian Andes.

Nearby, at Mashpi Amagusa, former farmers Doris Villalbaand Sergio Basantes have created a reserve, lodge and garden, which attracts 260 species of sought-after birds. Highlights include glistening-green, flame-faced and beryl-spangled tanagers, and the rare, endemic rose-faced parrot.

At Finca La Victoriana in Pichincha, the owner Jacqui bought the house and land, and began to reforest the site while growing crops to feed herself. But during lockdown, when she was stuck in nearby Quito, all her crops were stolen. She was saved from having to sell up by a visiting friend, who heard an unusual sound from lower down the valley and realised this was one of South America’s most charismatic birds: the Andean cock-of-the-rock.

Male Andean cocks-of-the-rock (Rupicola peruvianus) lekking to attract a mate. Photograph: Jiri Hrebicek/Alamy

Since 2005, Ángel Paz and his younger brother Rodrigo have transformed their former dairy farm in Mindo into a bird reserve. At first, things didn’t go to plan: it took a month for the first visitor to arrive, and he paid just $10 for a four-hour tour. Since then, however, thousands of people have made the pilgrimage.

#solarpunk#solar punk#indigenous knowledge#solarpunk aesthetic#informal economy#farms#wildlife#bird sanctuary#bird reserve#ecuador#south america

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

me when Rupicola peruvianus

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Male and female Andean cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola peruvianus), also known as tunki (Quechua), the national bird of Peru.

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi there! ummm idk if you like asks or not-- but i was wondering if you have a favorite/some favorite birds? 👀

i hope you're having a great day/night! 💙

Sorry for the delay, I have no problem answering questions. The answer will be a bit long, sorry xD I'm a big fan of almost all birds (the Californian condor is a bit difficult for me 😅), but if I had to choose a few I guess they would go like:

Chicken: I have a pet rooster, so there is a conflict of interest xD Roosters have a reputation for being more violent and not as affectionate than hens, and they are somewhat right xD but we managed to have three roosters living together in relative peace (two of them were brothers), and they could be like a dog that gets on the couch or wants to steal food when they want to xD Two of them have already passed away, but the remaining one has a switch between surly and silent affection

Mention to the Zenaida meloda who came to visit

2. Hummingbird: Hummingbirds in general, I like a lot of different species. I have a photo I was able to take of a baby Rhodopis vesper at my house.

3. Tachuris rubrigastra: I didn't know how high to place it in this kind of "top", but this bird was a national phenomenon so it couldn't be any other way. It became famous in 2023 when the Pan American and Parapan American games made it their official mascot under the name Fiu. I remember that at first I wasn't convinced because the character design and costume made it look too round without the shape of a real bird (the snob who says he knew it before it became famous xD), but it was a bird, I fell for it pretty quickly, I even got a pin of it xD.

Honorable mentions

Pitangus sulphuratus: A bird from tropical areas, when it sings it seems to say bem te vi xD. I am fond of it because I have seen it when visiting relatives.

Troglodytes aedon: A small, round bird that makes alarm noises.

Turdus falcklandii: He is my neighbor, very nice.

Rupicola peruvianus: It is a small rooster with a good hairstyle, nothing more to add

Pharomachrus mocinno: I have never seen one in person, but Guatemala has its own currency in its honor.

Daptrius chimango: The South American crow was found to be as intelligent as a raven

Owls and barn owls: Examples: Bubo magellanicus, Glaucidium nana, Athene cunicularia, Strix rufipes, Tyto alba

I hope it hasn't been too long xD I'd like to know what your favorite birds are, best regards :D

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cock-of-the-Rock (Rupicola peruvianus sanguinolentus) by ASAV Photography https://flic.kr/p/2ngpYmb

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devocional diário Vislumbres da Eternidade - Víctor Armenteros

Ovos contra pedras

Mesmo que o nosso ser exterior se desgaste, o nosso ser interior se renova dia a dia. 2ª Coríntios 4:16

Alguns anos atrás, deparei-me com um artigo interessante que falava sobre Física e ovos de galinha. Não se tratava do eterno debate sobre o ovo ou a galinha, mas sim de uma expressão chinesa, Yi luan ji shi, que se refere ao impacto de um ovo contra uma rocha, em que sempre é o ovo que se quebra. Essa ideia se fixou em minha mente como um modelo de quando duas forças desiguais colidem. É provável que isso lembre alguma experiência que você já teve na vida. No entanto, uma frase anônima que li recentemente me fez repensar minha concepção sobre “ovos” e “rochas”. Ela dizia: “Se for uma força externa que quebra um ovo, a vida se acaba. Se for uma força interna, a vida começa. Mude a partir do seu interior.” Essa frase espetacular me fez refletir que talvez o problema não esteja nas rochas.

O galo-da-serra-andino, também conhecido como Rupicola peruvianus, é a ave nacional do Peru e é uma das mais belas aves que já vi. Ele recebe o nome de “rupícola” por viver e fazer seu ninho em rochas montanhosas nos Andes. As fêmeas se camuflam perfeitamente nas encostas dos montes, tornando-se difíceis de serem vistas. Para essa espécie, as rochas não representam um problema, pois essas aves não temem as alturas. Talvez seja por isso que muitos as chamam de “galinho das rochas”.

Passamos a vida temendo as “rochas” e o impacto que elas podem causar em nossa existência, quando deveríamos estar nos desenvolvendo interiormente para sairmos do ovo e viver plenamente! É por isso que Paulo aconselha os coríntios a não desistirem e a terem a paciência necessária para crescerem internamente, mesmo que externamente sejam alvos de impactos. Devemos nos renovar a cada dia e voltar a tentar, pois a paciência molda o nosso caráter e nos fortalece para lidar com as dificuldades da vida.

Lembre-se: a maioria de nossas lutas não é contra o mundo exterior, mas sim com nosso mundo interior. Portanto, em vez de temermos as dificuldades e os desafios do viver, devemos encará-los como oportunidades de crescimento e aprimoramento. Que possamos, com o poder do Espírito Santo, buscar a força necessária para encarar as rochas da vida e nos tornar seres humanos melhores.

0 notes

Text

Vaya belleza y espectacular foto ✌️😍

No es una imagen generada por inteligencia artificial, está ave es un Gallito de las Rocas (Rupicola peruvianus).

A está bella ave se le considera el ave nacional de Perú 🇵🇪

Lamentablemente debido a su belleza es una de las especies más traficadas en la región.

Foto del ave en una postura más común en comentarios.

Foto: Jorge Alberto Morales Satalaya

0 notes

Text

Andean cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola peruvianus)

what the fuck is your problem man..,

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Andean Cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola peruvianus)

© Alex Cruz Jr 🦤

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andean Cock of the Rock (Rupicola peruvianus), male, family Cotingidae, order Passeriformes, Colombia

photograph by Adam Rainoff | Flickr

#cock of the rock#cotinga#rupicola#cotingidae#passeriformes#bird#ornithology#animals#nature#south america

489 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andean cock-of-the-rock

9 notes

·

View notes