#Royals should pay slavery reparations

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yahoo News UK: Royals should pay slavery reparations, say nearly half of Brits - exclusive Yahoo News poll

The Royal Family haven't been well received in the Caribbean in recent years, with two tours undertaken last year ending in PR disaster. (Getty Images)

New polling has shown that nearly half of Brits support financial reparations being paid by the Royal Family over their historic links to the slave trade.

The Savanta poll commissioned by Yahoo shows a big difference in how the issue was viewed by different age groups, with younger generations supporting reparations more than their older counterparts.

It's another signal of just how polarising the royals have become, and why one expert thinks that they have "fallen victim to the culture wars"

youtube

Overall, 44% of Brits think that the Royal Family should make financial reparations for their role in the transatlantic slave trade, while 32% don't think they should and a further 22% don't know.

Watch: Royal Family 'has fallen victim to the culture wars'

Royal Family 'has fallen victim to the culture wars'

Royal experts have accused the House of Windsor of falling victim to the "culture wars" amid the fallout from the Sussexes' departure from the UK.In a panel discussion on the 'Future of the Monarchy' hosted by Yahoo News UK's royal executive editor Omid Scobie, journalist and broadcaster Afua Hagen said the monarchy had become more divisive than in previous times - citing the Firm's treatment of Meghan Markle and subsequent family split as reflecting a more polarised society."The royal family have fallen victim to the culture wars - it's presumed if you like Meghan then you're a lefty, if you like Kate then you're right, you vote this way, you vote that way," Hagan said, addressing the panel.Joining Omid were author and co-founder of the Women’s Equality Party, Catherine Mayer; King Charles’ biographer and royal editor at The Evening Standard Robert Jobson; and journalist and broadcaster Afua Hagan.Watch the full clip above

The polling comes after King Charles announced he would allow a historian into the royal archives as part of a research project being undertaken by Historic Royal Palaces into the royals' ties to slavery.

However, Rishi Sunak made clear in Parliament on 26 April that the UK government currently has no intention of apologising for the country's role in the historic atrocity.

Of all age groups, 18 to 24-year-olds (58%) supported the royals paying financial reparations most strongly; this support gradually decreased to only 29% in the over 65s.

Political affiliation also played a part in how people responded to the question: with Conservative and Brexit Party voters coming in the lowest in favour of reparations being paid, at 29% and 20% respectively. 68% of Brexit Party voters surveyed said the Windsors should not make any financial reparations.

SNP voters responded most strongly in favour of the royals at 68%, this was closely followed by Green Party voters at 59% and Labour voters at 57%.

56% of respondents who voted Leave in the 2016 EU referendum said the royals shouldn't pay reparations, compared to 32% of those voted Remain.

King Charles has previously spoken about the UK's history of slavery on several occasions.

In 2018, he called it an "appalling atrocity" during a visit to Ghana, and in 2021 said that it "forever stains our history" during Barbados's official ceremony marking their transition to a republic and removal of Queen Elizabeth as their head of state.

Last year in Rwanda, Charles said in a speech that he "cannot describe the depths of [his] personal sorrow at the suffering of so many" and that he is working to "deepen [his] own understanding of slavery's enduring impact".

These sentiments have been echoed by Prince William, who expressed his "profound sorrow" over slavery during a visit to Jamaica.

However, as yet, no official apology has been given by the Royal Family for their part in the slave trade.

youtube

#Royals should pay slavery reparations#say nearly half of Brits - exclusive Yahoo News poll#reparations#england#britain#british reparations#Reparations#Youtube

0 notes

Text

I couldn’t give two hoots. If they want to “discuss” it, they can discuss it. They can discuss it for ever and ever. They can even make formal, binding resolutions to make us pay. They can do what they like. Again, I couldn’t give two hoots, because:

We ain’t paying!!

The slave trade is of course a shameful blot on our history. Most reasonable people accept that. We have to realise that we can’t change the past.

- As well as recognising how awful slavery was, we also have to realise that all countries were doing it.

- Some are still doing it today, 200 years later.

- We would do well to recognise that Britain was the first country in the world to abolish it.

- We should also remember that in the nineteenth century when the Royal Navy ruled the seas, it spent most of its time patrolling the oceans to stamp the trade out.

- We need to remember those tribal chiefs, kings and Arab traders in West Africa who profited so much from the slave trade.

- We also need to remember that the trans Atlantic slave trade could never have got off the ground without the full scale participation of those African chiefs and Arab traders - why are their descendants not being chased?

- Finally, and not leastly, we need to recognise that the British working classes in the Northern Mill Towns were held in conditions every bit as bad as slavery - where is MY compensation?

=======

I’m sick to death of this hand wringing guilt trip that so many people are on.

I believe that Britain can be rightly very proud of its record in being the first country to ban the slave trade and doing so much later on to keep it stamped out.

We should also recognise that these Caribbean countries that are clamouring for reparations, have been massive beneficiaries of being in the Commonwealth. Britain could have simply walked away, as many other imperial powers did. We didn’t, and many of these countries are far more affluent than their neighbours because of it.

0 notes

Text

British royals expert Hilary Fordwich stunned CNN anchor Don Lemon into silence with her argument that African slave owners owe "reparations" rather than the British Empire, in a viral clip from CNN’s coverage of the death of the queen.

Conservatives on Twitter found the clip hilarious, as it depicted Lemon getting swift pushback for trying to promote the narrative that the British crown owes reparations for slavery.

Observers noted Lemon meekly switching topics without protest after Fordwich’s unexpected response

The clip, which gained viral attention on Tuesday though it originally aired on CNN's Don Lemon Tonight around a week ago, began with the host telling Fordwich that "you have those who are asking for reparations for colonialism, and they’re wondering, you know, ‘$100 billion, $24 billion here and there, $500 million there.’"

QUEEN ELIZABETH II INSIGNIA MISSING FROM PRINCE HARRY'S UNIFORM, WORN BY PRINCE WILLIAM, PRINCE ANDREW

Some people want to be paid back and members of the public are wondering, ‘Why are we suffering when you are, you have all this vast wealth?’ Those are legitimate concerns," Lemon stated.

Fordwich agreed that the desire for reparations is alive and well, though those who want it can look to African slavers.

"Well I think you’re right about reparations in terms of – if people want it though, what they need to do is, you always need to go back to the beginning of the supply chain. Where was the beginning of the supply chain?" she asked.

"That was in Africa," she continued. "Across the entire world, when slavery was taking place, which was the first nation in the world that abolished slavery?" It was "the British," Fordwich declared, adding, "In Great Britain they abolished slavery. 2,000 naval men died on the high seas trying to stop slavery. Why? Because the African kings were rounding up their own people. They had them [in] cages, waiting in the beaches."

She concluded, "I think you’re totally right. If reparations need to be paid, we need to go right back to the beginning of that supply chain and say, ‘Who was rounding up their own people and having them handcuffed in cages. Absolutely, that’s where they should start."

After her answer, Lemon provided no pushback. He simply nodded, mentioned it’s "an interesting discussion" and moved to the next segment. As Twitter users pointed out, his silence was remarkable considering the anchor is one of the media’s most partisan personalities.

"HOLY MOLY DON LEMON WAS *NOT* READY FOR THIS," wrote National Pulse editor-in-chief Raheem Kassam.

"Dilbert" comics creator Scott Adams mocked Lemon’s unenthused facial expressions after hearing Fordwich’s historical lesson.

"His face at the end is the payoff," Adams remarked.

Independent journalist Tim Pool tweeted, "Lol at Don lemons face hearing this s---."

Conservative personality Former Republican congressional candidate Kimberly Klacik tweeted, "Don Lemon was NOT ready."

Conservative commentator Allie Beth Stuckey wrote, "Ok this is amazing. Don Lemon brings up the need for slave reparations from the royal family. His guest says, yes, people should be demanding reparations… from the African leaders who sold them into slavery."

"This is so spectacularly perfect that it’s almost as if Lemon was set up," remarked author and podcaster Dave Rubin.

Conservative commentator Jason Howerton quipped, "Sure sex is great, but have you seen the look on @donlemon's face after getting utterly REKT on-air on slavery reparations?"

"And NOW you know why Don Lemon was demoted. He's just not a very smart man. Way to go @donlemon," wrote radio host Joe Pagliarulo.

CPAC chair Matt Schlapp asked, "And how about reparations to those who fought alongside former slaves to abolish American slavery? According [to] Lemon’s logic Democrats would need to pay reparations to Republicans. Kinda like it."

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royal Family LIVE: Prince William to make major apology in bid to save Queen's legacy | Royal | News | Express.co.uk

Once again the RF making the Cambridges take the hit. He doesn't need to be held responsible and forced to apologize for atrocities that were committed long before he was ever born. It is the same for an American having to pay reparations. I know this is controversial, but hell no. My family did not own slaves, in fact my dad's family were indentured servants forced to come to the U.S. Do I get reparations for that? No! Because I do not hold people responsible for events that they personally have NOTHING to do with. Yes, slavery is bad. I am sorry for anyone to be forced to work without free will. However, NO ONE alive today should be forced to apologize for events that occurred YEARS before they were born.❤️🧡💛💚💙💜🤎🖤🤍❤️

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

DAN WOOTTON: Shame on Meghan Markle as her propa-gandists use the fantasy that the Royal Family is racist to derail Wills and Kate’s Jamaican tour and destroy the Commonwealth

By DAN WOOTTON FOR MAILONLINE

PUBLISHED: 18:25, 23 March 2022 | UPDATED: 18:25, 23 March 2022

Imagine Prince William’s fury.

As his royal tour to Jamaica with Kate is increasingly overshadowed by a toxic row over local calls for reparations to compensate for British colonialism (yawn), it’s the words of his own sister-in-law being weaponised against the Royal Family.

In fact, Meghan Markle’s pack of lies to her nodding BFF Oprah Winfrey suggesting the monarchy is a racist institution and casting doubt on its senior members is now providing a significant boost to the fast-moving republican cause in Jamaica at the worst possible moment.

For all their talk of believing in and loving the Commonwealth pre-Megxit, Harry and Meghan have become the pin-ups for its destruction.

This was always the concern of senior courtiers when Meghan’s claim to Oprah about a so-called unnamed ‘royal racist’ who asked about her unborn baby’s skin colour went unchallenged: Republicans across the Commonwealth would try to use the claims to bring the Queen’s reign to an end in the monarch’s twilight years.

That’s exactly what’s happening – and campaigners are using the media attention around William and Kate’s trip to inflict maximum damage.

‘This was the nightmare scenario after Meghan’s Oprah lies – now it’s coming true,’ says a concerned royal insider.

Leading the charge is Jamaican attorney and reparations advocate Bert Samuels, who swallowed Meghan’s crocodile tears hook, line and sinker to help advance his political cause for the UK to be forced to pay reparations to compensate for African slaves brought to the island before the practice was made illegal in 1833.

He told Newsweek: ‘Jamaicans were very torn up to hear about Harry and Meghan's issue, and Harry and Meghan's interview with Oprah Winfrey, and that has torn us. That's William's brother, that's his nephew, and for Harry to have been treated the way he was, and worse yet Meghan.

‘The Jamaicans are very hurt by the treatment of an African American woman in that family. William needs to speak to that when he comes and as it were, he should come here with an apology, not only for slavery but for the treatment of a black woman who had to run out of the palace with her husband. That's a strong issue and that's a fresh wound.’

As the journalist who broke the most stories about former Suits star Meghan’s tumultuous time in the Royal Family, including the Sussexes decision to Megxit, it’s utter hogwash to suggest her race played any role in the ensuing rows.

Meghan wasn’t pushed out of the Royal Family because of ethnicity and to even countenance such a fantasy is irresponsible.

In fact, she was given a huge amount of support from the Queen down but scarpered because, as a pampered actress used to assistants giving into her every whim, she wanted to return to the comfort of Hollywood and make the serious big bucks she thought she deserved.

Meghan soon realised a life of service wasn’t for her.

She had zero interest in supporting the Royal Family and zero interest in the Commonwealth, but cared a whole lot about her bank balance and celebrity status.

So it was convenient for the Sussexes to fashion a narrative behind their exit to make it more politically palatable to their leftie supporters, to hell with the damage it would cause to the Queen’s legacy - and that’s what makes me so angry.

Of course, Jamaicans have a right to self-determination and if they want to follow Barbados and become a republic, having first gained independence from Britain in 1962, then so be it.

Reparations to Jamaica were last ruled out by then-Prime Minister David Cameron during a visit to the island in 2015 where he said: ‘I do hope that, as friends who have gone through so much together since those darkest of times, we can move on from this painful legacy and continue to build for the future.’

But there’s not much hope of that after the disgraceful position the Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness put William and Kate in today as he launched a political speech as they stood by his side, despite how diligently the couple try to stay out of politics.

Holness said: ‘There are issues here which as you know are unresolved but your presence gives us an opportunity for those issues to be placed in context, to be out front and centre and to be addressed as best we can.

‘But Jamaica is, as you would see, a country that is proud of its history and very proud of what we have achieved. And we’re moving on and we intend to…fulfil our true ambitions and destiny to become an independent and prosperous country.’

That came hot on the heels of Lisa Hanna, a former Miss World turned politician with the People's National Party, a republican who has campaigned for reparations, rudely snubbing Kate during yesterday’s ceremonial arrival.

Despite only 60 protesters bothering to show up outside the British High Commission, Queen's Counsel Hugh Small says senior figures on both sides of Jamaican politics now want to address ‘the question of reparations with far more urgency’.

I think there’s zero chance of that happening, which is why it’s unconscionable for public sentiment to be whipped up using total falsehoods propagated by Meghan to Oprah.

After all, in the year since the CBS interview, claim after claim has been resolutely debunked, resulting in the Queen’s extraordinary statement that ‘recollections may vary’ and William publicly stating furiously that ‘we are very much not a racist family’.

That said, the Duke of Cambridge is a modern man acutely aware of Britain’s history and he will do his best to show Jamaicans he has listened to their concerns. Tonight, he intends to reference historic slavery in a speech in Kingston.

Prince Charles too recently referenced ‘the appalling atrocity of slavery’ in the Caribbean during the ceremony he attended as Barbados became a republic. I would say the future king even took it one step too far by admitting it ‘forever stains our history’.

The point is this is no longer a Royal Family burying its head in the sand about historic controversies.

However, Harry and Meghan’s personal propagandists in the craven left-wing US media shamefully continue to try and paint William as some sort of racist at every opportunity, delighting the vile Sussex Squad trolls online.

Omid Scobie – author of the hagiography Finding Freedom, with which Meghan had to admit she had forgotten collaborating with in court – now regularly tries to bring down the future king with snide snipes suggesting he is some sort of gammon.

Today, silly Scobie has suggested that a lack of diversity on William’s team (translation: the fact he has white staff members) resulted in negative coverage about the Jamaican protests.

Scobie tweeted: ‘I do wonder what the hell palace organisers were thinking with some of yesterday's photo moments. The planning and recon that goes into every step of these engagements is next level, so how did no one think to avoid certain imagery? This is why diversity on a team matters.’

It’s all quite embarrassing, given we now know from whom silly Scobie takes his marching orders.

But those trying to paint a picture of our 95-year-old monarch – who has spent her entire life working to strengthen the Commonwealth – as some sort of racist is a disgrace.

Anyone who knows anything about the Queen is aware that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Shame on Meghan Markle for the damage she’s caused to the Commonwealth and shame on the propagandists in Jamaica and the media using her fantasies to advance their republican cause.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royals, republicanism and reparations: Wessexes feel the heat in Caribbean

Weeks after William and Kate’s controversial Caribbean tour, more nations signal plans to ditch the monarchy

Shanti Das

Sun 1 May 2022 12.00 (CEST)

Follow Shanti Das

Sitting across from the prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda last week, partway through a royal tour to celebrate the Queen’s platinum jubilee, Prince Edward laughed awkwardly. Gaston Browne had just asked the prince whether he and his wife Sophie would use their “diplomatic influence” to push for the payment of slavery reparations to Britain’s former colonies. “We believe that all human civilisation should understand the atrocities that took place,” the Caribbean nation’s political leader told the Queen’s youngest son.

In the same meeting came a second blow. “One day,” the prime minister told the couple, Antigua and Barbuda – a former British colony where the Queen is still the head of state – would cut ties with the monarchy and become a republic. Prince Edward shuffled nervously in his seat. “I wasn’t keeping notes, so I’m not going to give you a complete riposte,” he said. “But thank you for your welcome today.”

Protesters in St Vincent

Protesters in St Vincent during the royal visit last week. Photograph: Kenton X Chance/I-Witness News

The painful exchange was one in a series of historic moments in the Earl and Countess of Wessex’s week-long tour of the Caribbean, the second royal tour to the region in two months to be mired in controversy.

By the end of the trip last Thursday, two Commonwealth nations had indicated their intention to cut ties with the royal family and become republics. St Kitts and Nevis also revealed its plan to review its ties with the monarchy.

“The advancement of the decades has taught us that the time has come for St Kitts and Nevis to review its monarchical system of government and to begin the dialogue to advance to a new status,” Shawn Richards, deputy prime minister, told reporters.

Prince Edward meets Gaston Browne, prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda

Prince Edward meets Gaston Browne, prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda. Photograph: Stuart C Wilson/Getty Images

The declarations follow similar moves by other Commonwealth realms, several of which signalled their own plans to cut ties with the monarchy following a separate tour of the Caribbean by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in March.

During that tour, William and Kate were accused of harking back to colonial days after they shook hands with crowds behind a wire mesh fence in Jamaica, and rode in the back of a Land Rover like the Queen did 60 years ago. Protesters accused them of benefiting from the “blood, tears and sweat” of slaves, while in the Bahamas they were urged to acknowledge the British economy was “built on the backs” of slaves and to pay reparations.

Jamaica’s prime minister Andrew Holness told William and Kate that his country was “moving on” and may be the next to become a republic, while a minister from Belize said it was time to “take the next step in truly owning our independence”.

The latest declarations mean six of the 14 countries beyond the UK that have the Queen as head of state have now indicated that they want to remove her – Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica and St Kitts and Nevis.

If they do they will join countries including Trinidad, Guyana, Dominica and most recently Barbados, which became the world’s newest republic in November.

The royal tours have also led to renewed calls for reparations – an acknowledgement of the history of enslavement and payment for the damage – from Britain and the monarchy, even from countries with no current plans to cut ties with the Queen.

In St Vincent and the Grenadines – which held a referendum on becoming a republic in 2009 that failed to pass when 55% of voters voted against such a move, and has no current plans for another vote – protesters as well as supporters greeted Edward and Sophie during their visit.

“This wrong was done against a sector of the human race by another and this wrong must be compensated,” said Idesha Jackson, 47, one protester who came out during the Wessexes’ visit.

The controversy has led to concern at the Palace. After returning to the UK in March, Prince William acknowledged the monarchy’s days in the Caribbean may be numbered. “‘I know that this tour has brought into even sharper focus questions about the past and the future,” he said, adding that the future was “for the people to decide upon”.

On Saturday it was reported that after getting home William and Kate summoned senior staff for a meeting to “clear the air”, with a source telling the Mirror they felt they had been “poorly prepared”. “If they aren’t in tune with what is going on in the world they will be left fighting for their futures,” the source said.

For now, future royal tours would be “unwise”, said Peter Hunt, the former BBC royal correspondent.

“The world has moved on in the wake of the Windrush scandal and Black Lives Matter,” he said. “Any future trips would be unwise. The role of Britain and the monarchy in the slave trade would feature, and the royals appear ill-equipped to rise to the occasion.”

#royals#brf#colonialism#abolish the monarchy#prince william#kate middleton#prince edward#sophie wessex#duke of cambridge#duchess of cambridge#caribbean

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“As an Antiguan watching the Barbados republic celebrations was the most beautiful thing to witness, just so rich in significance and extremely inspiring. I'm sure their ancestors in Heaven were smiling down on them proudly. Can't wait for Antigua and Barbuda's turn to rid ourselves of english self-described royals, in the meantime wishing my Barbadian brothers and sisters much fortune, peace, love and prosperity! May all Caribbean islands be truly free one day.” - Submitted by Anonymous

“We should all be following in Barbados' footsteps. For them cutting ties with the UK monarchy has greater significance 'cause of their history as a colonial slave society but as a Canadian I think it makes no sense to still have a head of state who's not from here,doesn't share our culture,doesn't speak like us,lives an ocean away,only visits once every few years. I love following UK royals' lives but not as institutional figures, more like the biggest reality stars on Earth(sorry Kardashians!).” - Submitted by Anonymous

“The royal family aren’t going to pay reparations and they have no real influence to make the UK government pay (and the UK government definitely isn’t paying) so I think it’s sort of pointless to keep asking them to but I do think they could at least apologise for their families involvement and acknowledge they did benefit from slavery even if it was long ago. They could also donate something to these countries from their personal wealth. Obviously it won’t be anywhere near what the estimated reparations payment would be but something is better than nothing. If they aren’t going to do anything they should just stop going to those countries as they’re only embarrassing themselves at this stage.” - Submitted by Anonymous

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"AFRICAN KINGDOMS SHOULD PAY REPARATIONS FOR SLAVERY," TOO. Openly Homosexual CNN Host DON LEMON Was Visibly Stunned When ROYAL COMMENTATOR HILARY FORDWICH Said, African Kings - Not British Royals - Should Pay Reparations For Slavery Because "THEY ROUNDED UP THEIR OWN PEOPLE AND HAD THEM WAITING IN CAGES ON THE BEACHES."

“AFRICAN KINGDOMS SHOULD PAY REPARATIONS FOR SLAVERY,” TOO. Openly Homosexual CNN Host DON LEMON Was Visibly Stunned When ROYAL COMMENTATOR HILARY FORDWICH Said, African Kings – Not British Royals – Should Pay Reparations For Slavery Because “THEY ROUNDED UP THEIR OWN PEOPLE AND HAD THEM WAITING IN CAGES ON THE BEACHES.”

CNN anchor Don Lemon interviewed Hilary Fordwich on the night of Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral. The anchor suggested the royal family should pay slavery reparations “AFRICAN KINGDOMS SHOULD PAY REPARATIONS FOR SLAVERY,” TOO. Openly Homosexual CNN Host DON LEMON Was Visibly Stunned When ROYAL COMMENTATOR HILARY FORDWICH Said, African Kings – Not British Royals – Should Pay Reparations For Slavery…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Reparations – Has the Time Finally Come?

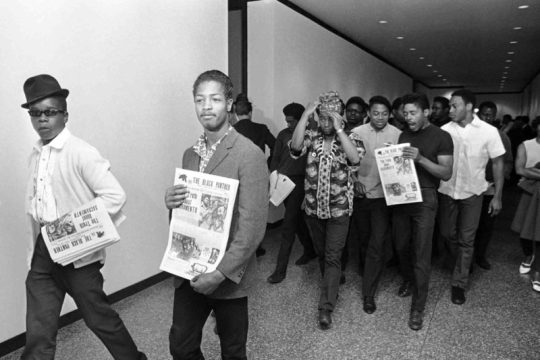

During a lull one afternoon when I was a high school student selling Black Panther Party newspapers on the streets of downtown Washington, D.C., in 1971, I sat down on the curb and opened the tabloid to the 10-point program, “What We Want; What We Believe.” The graphic assertion of “Point Number 3” particularly grabbed me:

“We believe that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the overdue debt of forty acres and two mules … promised 100 years ago as restitution for slave labor and mass murder of Black people. We will accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. The Germans are now aiding the Jews in Israel for the genocide of the Jewish people. The Germans murdered six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over fifty million Black people. Therefore, we feel this is a modest demand that we make.”

The absence of justice continually flustered me because, even at that young age, I knew that Black people had been kidnapped and brought to this country to labor for free as slaves; stripped of our language, religion, and culture; raped and tortured; and then subjected to a Jim Crow-era of lynchings, police brutality, inferior education, substandard housing, and mediocre health care. I did not know then about the massacres in Rosewood, Florida, or Tulsa, Oklahoma; the merciless experimentations on defenseless Black women devoid of anesthesia that led to modern gynecology; or about the enormous profits from slavery made by corporations, insurance companies, the banking and investment industries, and academic institutions. But on a psychic level, I could feel in my bones the enslavement era’s inhumane cruelty to Black children — its destruction of kindred ties and its economic exploitation and cultural deprivation. There was an incessant gnawing in my soul for amends and redress. I was passionate about injustice, felt the idea of reparations to be reasonable and fair, and vowed to talk about the concept whenever and wherever I could. My analysis, however, had not crystallized beyond a check. But just to mouth the word “reparations” was a starting point to its validity. Thus talk about it I did, despite my views being often rejected, ridiculed, or otherwise summarily dismissed. Standing on the street corner that afternoon nearly five decades ago, little did I realize that I would one day be in the company of leading academics, economists, historians, attorneys, psychiatrists, politicians, and more — domestically and internationally — promoting the right to, and the need for, reparations.

Several members of the Black Panther party carry copies of the Black Panther newspaper

Credit: Associated Press

The Fight for Reparations Has a Long History

But that day would be far into the future. Despite my advocacy and that of many others during my high school, college, and law school years and beyond, the issue of reparations for descendants of Africans enslaved in the United States was not fashionable, but fringe, and definitely not part of the mainstream popular discourse. Indeed, one would be branded as a militant or a revolutionary (both of which I was), or just plain crazy (which I was not), or in today’s dubious governmental surveillance parlance, a “Black Identity Extremist.” Indeed, it is almost surreal being amidst all the buzz surrounding reparations today, from universities to talk show pundits and, interestingly, to 2020 Democratic candidates vying for the presidency. Despite or perhaps because of today’s surge in attention to this longstanding issue, I feel it critical that the populace understands that the demand for reparations in the U.S. for unpaid labor during the enslavement era and post-slavery discrimination is not novel or new. The claim did not drop from the sky with Ta’Nehisi Coates’ brilliant treatise, “The Case for Reparations,” in The Atlantic, or from Randall Robinson’s impassioned book, “The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks,” both of which galvanized the issue in different decades and thrust it into national conversation.

Although there have been hills and valleys in national attention to the issue, there has been no substantial period of time when the call for redress was not passionately voiced. The first formal record of a petition for reparations in the United States was pursued and won by a formerly enslaved woman, Belinda Royall. Professor Ray Winbush’s book, “Belinda’s Petition,” describes a petition she presented to the Massachusetts General Assembly in 1783, requesting a pension from the proceeds of her enslaver’s estate — an estate partly the product of her own uncompensated labor. Belinda’s petition yielded a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings. Former U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Mary Frances Berry illuminated the case of Callie House in her book, “My Face Is Black Is True.” Callie, along with Rev. Isaiah Dickerson, headed the first mass reparations movement in the United States, founded in 1898. The National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Bounty and Pension Association had 600,000 dues-paying members who sought to obtain compensation for slavery from federal agencies. During the 1920s, Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association galvanized hundreds of thousands of Black people seeking repatriation with reparation, proclaiming, “Hand back to us our own civilisation. Hand back to us that which you have robbed and exploited of us … for the last 500 years.” During the 1950s and 1960s, New York’s Queen Mother Audley Moore was perhaps the best-known advocate for reparations. As president of the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women, she presented a petition against genocide and for self-determination, land, and reparations to the United Nations in both 1957 and 1959. She was active in every major reparations movement until her death in 1996.

Queen Mother Audley Moore

Credit: Associated Press

In his 1963 book, “Why We Can’t Wait,” Dr. Martin Luther King proposed a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,” which emphasized redress for both the historical victimization and exploitation of Blacks as well as their present-day degradation. “The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of labor on one human being by another,” he wrote. “This law should be made to apply for the American Negroes.” After the Black Panther Party’s stance in 1966, the Republic of New Afrika proclaimed in its 1968 “Declaration of Independence:

“We claim no rights from the United States of America other than those rights belonging to people anywhere in the world, and these include the right to damages, reparations, due us from the grievous injuries sustained by ourselves and our ancestors by reason of United States’ lawlessness.”

In April 1969, the “Black Manifesto” was adopted at a National Black Economic Development Conference. The manifesto, presented by civil rights activist James Forman, included a demand that white churches and synagogues pay $500 million in reparations to Blacks in the U.S. The amount was based on a calculation of $15 for each of the estimated 20 to 30 million African Americans residing in the U.S. He touted it as only the beginning of the amount owed. The following month, Forman interrupted Sunday service at Riverside Church in New York to announce the reparations demand from the “Black Manifesto.” Notably, several religious institutions did respond with financial donations. In 1972, the National Black Political Assembly Convention meeting in Gary, Indiana, adopted “The Anti-Depression Program,” an act authorizing the payment of a sum of money in reparations for slavery as well as the creation of a negotiating commission to determine kind, dates, and other details of paying reparations. Consistently, the Nation of Islam’s publications — such as Muhammad Speaks and, later, The Final Call — have demanded that the United States exempt Black people “from all taxation as long as we are deprived of equal justice.”

The Modern-Day Reparations Movement

But it was the end of the 20th century that brought broad national attention to the call for reparations for people of African descent in the United States with the founding of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (NCOBRA). I was proud to be a founding member of NCOBRA at the historic gathering on Sept. 26, 1987, which brought together diverse groups under one umbrella, from the Republic of New Afrika to the National Conference of Black Lawyers. For its first decade in existence, I served as chair of NCOBRA’s legislative commission. Since the creation of NCOBRA, the demand for reparations in the United States substantially leaped forward, generating what I’ve dubbed “The Modern-Day Reparations Movement.” Inspired by and organized on the heels of the passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which granted reparations to Japanese-Americans for their unjust incarceration during World War II, NCOBRA reinvigorated the demand for reparations for African Americans and broadened the concept through public education, accompanied by legislative and litigation-based initiatives. Also encouraged by the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, Rep. John Conyers introduced a bill in 1989 to “establish a commission to examine the institution of slavery and subsequent racial and economic discrimination against African Americans and the impact of these forces on Black people today.” This commission would be charged with making recommendations to the Congress on appropriate remedies. The bill’s number “H.R. 40” was in remembrance of the unfulfilled 19th-century campaign promise to give freed Blacks 40 acres and a mule. Conyers’ “Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act” provided the cover and vehicle to have a public policy discussion on the issue of reparations in Congress.

Rep. John Conyers

Credit: Associated Press

The 1988 Civil Liberties Act authorized the payment of $20,000 to each Japanese-American detention-camp survivor, a trust fund to be used to educate Americans about the suffering of the Japanese-Americans, a formal apology from the U.S. government, and a pardon for all those convicted of resisting detention camp incarceration. It is a sad commentary that the U.S. government has not taken formal responsibility for its role in the enslavement or post-slavery apartheid segregation of millions of Blacks. It has never attempted reparations to African Americans for the extortion of labor for many generations, deprivation of their freedom and human rights, and terrorism against them throughout the centuries. The U.S. Senate and House did pass symbolic resolutions apologizing for slavery and segregation. However, the 2009 bill passed by the Senate contained a disclaimer that those seeking reparations or cash compensation could not use the apology to support a legal claim against the U.S. Since the introduction of H.R. 40, several state legislatures and scores of city councils across the country have passed reparations-type legislation or resolutions endorsing H.R. 40. In 1990, the Louisiana House of Representatives passed a resolution in support of reparations. In 1991, legislation was introduced in the Massachusetts Senate providing for the payment of reparations for slavery, the slave trade, and individual discrimination against the people of African descent born or residing in the commonwealth of Massachusetts. In 1994, the Florida Legislature paid $150,000 to each of the 11 survivors of the 1923 Rosewood Race Massacre and created a scholarship fund for students of color. In 2001, the California State Assembly passed a resolution in support of reparations. After a four-year investigation, the Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act was enacted in 2001. Oklahoma legislators settled on a scholarship fund and memorial to commemorate the June 1921 massacre that left as many as 300 Black people dead and 40 square blocks of exclusively Black businesses, homes, and schools obliterated. That same year, a bill was introduced in the New York State Assembly to create a “Commission to Quantify the Debt Owed to African Americans.” Bills are also pending within several other state legislatures, but the reparations movement isn’t just targeting state houses. City councils in the states of Arkansas, California, Georgia, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, and the District of Columbia have all passed resolutions in support of H.R. 40. Reparations advocates have also challenged corporations who benefited from the profits made from trafficking in human beings during the enslavement era. Countless companies and industries benefited and were enriched from the profits made as a result of chattel slavery. There are companies that sold life insurance policies on the lives of enslaved persons, such as Aetna, New York Life, and AIG. Financial gains were accrued by the predecessor banks of financial giants like J.P. Morgan Chase and Bank of America. Others with documented ties to slavery included railroads like Norfolk Southern, CSX, Union Pacific, and Canadian National. Newspaper publishers that assisted in the capture of runaway persons include Knight Rider, Tribune, E.W. Scripps, and Gannett. The financial backers of many of the country’s top universities were wealthy slave owners, and it has been disclosed that the reason Georgetown University stands today is because the Jesuits who ran the college used profits from the sale of Black people to continue its operation. Survivors of torture by Chicago police received an unprecedented compensatory package based on a reparations ordinance passed by the Chicago City Council in 2015. Numerous civil and human rights organizations, religious groups, professional organizations, civic groups, sororities, fraternities, and labor unions have also officially endorsed the call for reparations. In 2016, the Movement for Black Lives Policy Table released its platform, which prominently featured the issue of reparations. The role that governments, corporations, industries, religious institutions, educational institutions, private estates, and other entities played in supporting the institution of slavery and its vestiges are roles that can no longer be ignored, dismissed outright, or swept under the rug. The time is now ripe that their involvement be recognized, examined, discussed, and redressed.

The Demand Deserves Serious Consideration

I am part of the inaugural cohort of commissioners on the National African American Reparations Commission (NAARC), convened by the Institute of the Black World 21st Century in 2016. The commission’s preamble asserts:

“No amount of material resources or monetary compensation can ever be sufficient restitution for the spiritual, mental, cultural and physical damages inflicted on Africans by centuries of the MAAFA, the holocaust of enslavement and the institution of chattel slavery.”

Recognizing these as “crimes against humanity,” as acknowledged by the 2001 Durban Declaration and Program of Action of the World Conference Against Racism in South Africa, the preamble goes on to assert that “the devastating damages of enslavement and systems of apartheid and de facto segregation spanned generations to negatively affect the collective well-being of Africans in America to this very moment.” NAARC has advanced a comprehensive, yet preliminary, reparations program to guide reparatory justice demands by people of African descent in the United States. Finally, although my primary focus has been on obtaining reparations for African descendants in the United States, it is critical to recognize that our quest is part of the international movement for reparations as well. As such, I have worked closely with supporters of reparations throughout the world, recognizing that the success of the movement for reparations for diasporic Africans anywhere advances the movement for reparations by Africans and African descendants everywhere. I am thrilled that my quest to have reparations seen as a legitimate concept for African Americans, begun nearly 50 years ago, is becoming a reality. The issue has become more precise, less rhetorical, and has entered the mainstream. And while cash payments remain an important and necessary component of any claim for damages, it is crystal clear today that a reparations settlement can be fashioned in as many ways as necessary to equitably address the countless manifestations of injury sustained from chattel slavery and its continuing vestiges. Some forms of redress may include land, economic development, or scholarships. Other amends may embrace community development, repatriation resources, or truthful textbooks. Still, other areas of reparatory justice may encompass the erection of monuments and museums, pardons for impacted prisoners from the COINTELPRO-era, and repairing the harms from the War on Drugs. Fifty years after I first entered the reparations movement, I’m optimistic. It’s hard not to be when H.R. 40 has been updated to include not just a mere study of proposals but also their development. It’s also hard not to be optimistic when a Senate companion bill to H.R. 40 has been introduced and even more astonishing when some Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential race are saying they will sign the legislation if elected president. Despite a resurfacing of white supremacy in the U.S., I can see the light at the end of the tunnel. I am buoyed by the reemergence of the spirits of Belinda, Callie House, and Queen Mother Moore as well as the resilience of “Reparations Ray” Jenkins, who kept the fire alive in Rep. Conyers to introduce H.R. 40 year after year. And I am inspired by the words of the great anti-slavery orator Frederick Douglass, who poignantly instructed that “power concedes nothing without a demand.” The demand has been made and the time to seriously consider reparations has finally come.

READ THE FULL REPARATIONS SERIES

Nkechi Taifa is founder and president of The Taifa Group, LLC. An accomplished human rights attorney, she is a justice system reform strategist, advocate, and scholar.

Published May 27, 2020 at 12:05AM via ACLU https://ift.tt/3grc5uE

0 notes

Video

youtube

buying an essay

About me

Buy Essay Online Cheap With Mcessay And Receive Great Paper

Buy Essay Online Cheap With Mcessay And Receive Great Paper The draft officials offered him an exemption if he stayed residence and labored. He found that he could go into shops with out being bothered. There was little or no help for educating black individuals in Mississippi. But Julius Rosenwald, a part proprietor of Sears, Roebuck, had begun an ambitious effort to build faculties for black kids throughout the South. Ross’s trainer believed he ought to attend the local Rosenwald college. It was too far for Ross to stroll and get back in time to work in the fields. You shall be required to log into your account at HandMadeWriting.com to accept the preview model of your paper to be able to receive a completed copy. Our paper presentation codecs embody Chicago, Harvard, APA, and MLA referencing types. Get SAT dates and information on fee waivers, IDs, the essay option, insurance policies, and more. We're engaged on the problem and anticipate to resolve it shortly. Please observe that when you had been trying to position an order, it is not going to have been processed at this time. It carried greater than 20 enslaved Africans, who were offered to the colonists. No side of the nation that may be shaped right here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed. On the 400th anniversary of this fateful moment, it is finally time to inform our story truthfully. Explains how qualifying low-earnings 11th- and twelfth-graders can take the SAT and apply to four schools free of charge. Find what you should assist students do their greatest and understand their SAT scores. We weren't there when Woodrow Wilson took us into World War I, however we are nonetheless paying out the pensions. If Thomas Jefferson’s genius issues, then so does his taking of Sally Hemings’s physique. If George Washington crossing the Delaware matters, so must his ruthless pursuit of the runagate Oney Judge. Belinda Royall was granted a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings, to be paid out of the property of Isaac Royall—one of the earliest profitable attempts to petition for reparations. Earning a great popularity in the eyes of your school professor is important, since in many circumstances your reputation will be just right for you even if you're removed from being the most effective student. So, irrespective of if you send us a request to compose an honest essay for you, you can count on the ready-made piece in your inbox lengthy earlier than the deadline. If a revision is required, please ask for one without pressing the ACCEPT button. Only if and when the paper meets your approval and you want the MS Word version of the finished paper are you able to then press the ACCEPT button. It is essential that you just carefully evaluation the preview version and supply essential feedback for revision if you are not happy with the paper. The preview model is a watermarked picture of your accomplished paper. On completion of your project, you'll be notified through email and/or phone. Clyde Ross didn't, and thus misplaced the possibility to higher his training. By our unpaid labor and struggling, we now have earned the proper to the soil, many times time and again, and now we are decided to have it. An earlier version of the introduction to this project referred incorrectly to Virginia in the year 1619 as a British colony. In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the English colony of Virginia. He may walk the streets without being harassed. He might go right into a restaurant and obtain service. His teacher thought he should attend a more challenging faculty. Black families, regardless of income, are significantly much less rich than white households. Effectively, the black household in America is working without a safety web. When financial calamity strikes—a medical emergency, divorce, job loss—the autumn is precipitous. He is 91, and the emblems of survival are all around him—awards for service in his community, footage of his kids in cap and gown. But after I asked him about his residence in North Lawndale, I heard solely anarchy.

0 notes

Video

youtube

buy an essays

About me

Three Prewriting Strategies For Any Writing Undertaking

Three Prewriting Strategies For Any Writing Undertaking We weren't there when Woodrow Wilson took us into World War I, but we are nonetheless paying out the pensions. If Thomas Jefferson’s genius matters, then so does his taking of Sally Hemings’s physique. There was very little assist for educating black folks in Mississippi. But Julius Rosenwald, a part proprietor of Sears, Roebuck, had begun an formidable effort to build faculties for black children all through the South. Ross’s instructor believed he should attend the local Rosenwald school. The final soldier to endure Valley Forge has been lifeless much longer. To proudly claim the veteran and disown the slaveholder is patriotism à la carte. We weren't there when Washington crossed the Delaware, but Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s rendering has that means to us. By then the damage was carried out—and stories of redlining by banks have continued. In this creative rendering by Henry Louis Stephens, a widely known illustrator of the period, a household is within the strategy of being separated at a slave public sale. The wealth accorded America by slavery was not just in what the slaves pulled from the land but in the slaves themselves. Loans have been taken out for purchase, to be repaid with curiosity. Insurance insurance policies had been drafted in opposition to the premature demise of a slave and the lack of potential profits. The vending of the black body and the sundering of the black household became an economic system unto themselves, estimated to have brought in tens of millions of dollars to antebellum America. In 1860 there have been extra millionaires per capita in the Mississippi Valley than anyplace else in the nation. But the reminiscences of these robbed of their lives still live on in the lingering results. Indeed, in America there's a unusual and powerful belief that should you stab a black person 10 occasions, the bleeding stops and the therapeutic begins the second the assailant drops the knife. We imagine white dominance to be a truth of the inert previous, a delinquent debt that may be made to disappear if only we don’t look. One cannot escape the question by hand-waving on the previous, disavowing the acts of one’s ancestors, nor by citing a latest date of ancestral immigration. The last slaveholder has been lifeless for a very long time. If George Washington crossing the Delaware matters, so should his ruthless pursuit of the runagate Oney Judge. Belinda Royall was granted a pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings, to be paid out of the estate of Isaac Royall—one of many earliest profitable makes an attempt to petition for reparations. Black families, no matter income, are significantly much less rich than white families. Effectively, the black household in America is working and not using a safety net. When financial calamity strikes—a medical emergency, divorce, job loss—the autumn is precipitous. He found that he could go into stores with out being bothered. He may stroll the streets with out being harassed. He may go into a restaurant and receive service. His trainer thought he should attend a more challenging college. For the following 250 years, American legislation labored to cut back black individuals to a class of untouchables and lift all white males to the level of residents. In 1650, Virginia mandated that “all individuals except Negroes” had been to carry arms. In 1664, Maryland mandated that any Englishwoman who married a slave must reside as a slave of her husband’s master. But at the beginning of the 18th century, two main classes were enshrined in America. Money and time that Ross needed to give his children went instead to complement white speculators. “Previously, prejudices have been personalised and individualized; FHA exhorted segregation and enshrined it as public coverage. Whole areas of cities have been declared ineligible for loan guarantees.” Redlining was not formally outlawed until 1968, by the Fair Housing Act. He is 91, and the emblems of survival are throughout him—awards for service in his group, footage of his kids in cap and robe. But after I asked him about his home in North Lawndale, I heard solely anarchy. The draft officials supplied him an exemption if he stayed home and labored.

0 notes

Text

My parents’ home, in Umujieze, Nigeria, stands on a hilly plot that has been in our family for more than a hundred years. Traditionally, the Igbo people bury their dead among the living, and the ideal resting place for a man and his wives is on the premises of their home. My grandfather Erasmus, the first black manager of a Bata shoe factory in Aba, is buried under what is now the visitors’ living room. My grandmother Helen, who helped establish a local church, is buried near the study. My umbilical cord is buried on the grounds, as are those of my four siblings. My eldest brother, Nnamdi, was born while my parents were studying in England, in the early nineteen-seventies; my father, Chukwuma, preserved the dried umbilical cord and, eighteen months later, brought it home to bury it by the front gate. Down the hill, near the river, in an area now overrun by bush, is the grave of my most celebrated ancestor: my great-grandfather Nwaubani Ogogo Oriaku. Nwaubani Ogogo was a slave trader who gained power and wealth by selling other Africans across the Atlantic. “He was a renowned trader,” my father told me proudly. “He dealt in palm produce and human beings.”

Long before Europeans arrived, Igbos enslaved other Igbos as punishment for crimes, for the payment of debts, and as prisoners of war. The practice differed from slavery in the Americas: slaves were permitted to move freely in their communities and to own property, but they were also sometimes sacrificed in religious ceremonies or buried alive with their masters to serve them in the next life. When the transatlantic trade began, in the fifteenth century, the demand for slaves spiked. Igbo traders began kidnapping people from distant villages. Sometimes a family would sell off a disgraced relative, a practice that Ijoma Okoro, a professor of Igbo history at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, likens to the shipping of British convicts to the penal colonies in Australia: “People would say, ‘Let them go. I don’t want to see them again.’ ” Between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, nearly one and a half million Igbo slaves were sent across the Middle Passage.

My great-grandfather was given the nickname Nwaubani, which means “from the Bonny port region,” because he had the bright skin and healthy appearance associated at the time with people who lived near the coast and had access to rich foreign foods. (This became our family name.) In the late nineteenth century, he carried a slave-trading license from the Royal Niger Company, an English corporation that ruled southern Nigeria. His agents captured slaves across the region and passed them to middlemen, who brought them to the ports of Bonny and Calabar and sold them to white merchants. Slavery had already been abolished in the United States and the United Kingdom, but his slaves were legally shipped to Cuba and Brazil. To win his favor, local leaders gave him their daughters in marriage. (By his death, he had dozens of wives.) His influence drew the attention of colonial officials, who appointed him chief of Umujieze and several other towns. He presided over court cases and set up churches and schools. He built a guesthouse on the land where my parents’ home now stands, and hosted British dignitaries. To inform him of their impending arrival and verify their identities, guests sent him envelopes containing locks of their Caucasian hair.

Funeral rites for a distinguished Igbo man traditionally include the slaying of livestock—usually as many cows as his family can afford. Nwaubani Ogogo was so esteemed that, when he died, a leopard was killed, and six slaves were buried alive with him. My family inherited his canvas shoes, which he wore at a time when few Nigerians owned footwear, and the chains of his slaves, which were so heavy that, as a child, my father could hardly lift them. Throughout my upbringing, my relatives gleefully recounted Nwaubani Ogogo’s exploits. When I was about eight, my father took me to see the row of ugba trees where Nwaubani Ogogo kept his slaves chained up. In the nineteen-sixties, a family friend who taught history at a university in the U.K. saw Nwaubani Ogogo’s name mentioned in a textbook about the slave trade. Even my cousins who lived abroad learned that we had made it into the history books.

Last year, I travelled from Abuja, where I live, to Umujieze for my parents’ forty-sixth wedding anniversary. My father is the oldest man in his generation and the head of our extended family. One morning, a man arrived at our gate from a distant Anglican church that was celebrating its centenary. Its records showed that Nwaubani Ogogo had given an armed escort to the first missionaries in the region—a trio known as the Cookey brothers—to insure their safety. The man invited my father to receive an award for Nwaubani Ogogo’s work spreading the gospel. After the man left, my father sat in his favorite armchair, among a group of his grandchildren, and told stories about Nwaubani Ogogo.

“Are you not ashamed of what he did?” I asked.

“I can never be ashamed of him,” he said, irritated. “Why should I be? His business was legitimate at the time. He was respected by everyone around.” My father is a lawyer and a human-rights activist who has spent much of his life challenging government abuses in southeast Nigeria. He sometimes had to flee our home to avoid being arrested. But his pride in his family was unwavering. “Not everyone could summon the courage to be a slave trader,” he said. “You had to have some boldness in you.”

My father succeeded in transmitting to me not just Nwaubani Ogogo’s stories but also pride in his life. During my school days, if a friend asked the meaning of my surname, I gave her a narrative instead of a translation. But, in the past decade, I’ve felt a growing sense of unease. African intellectuals tend to blame the West for the slave trade, but I knew that white traders couldn’t have loaded their ships without help from Africans like my great-grandfather. I read arguments for paying reparations to the descendants of American slaves and wondered whether someone might soon expect my family to contribute. Other members of my generation felt similarly unsettled. My cousin Chidi, who grew up in England, was twelve years old when he visited Nigeria and asked our uncle the meaning of our surname. He was shocked to learn our family’s history, and has been reluctant to share it with his British friends. My cousin Chioma, a doctor in Lagos, told me that she feels anguished when she watches movies about slavery. “I cry and cry and ask God to forgive our ancestors,” she said.

The British tried to end slavery among the Igbo in the early nineteen-hundreds, though the practice persisted into the nineteen-forties. In the early years of abolition, by British recommendation, masters adopted their freed slaves into their extended families. One of the slaves who joined my family was Nwaokonkwo, a convicted murderer from another village who chose slavery as an alternative to capital punishment and eventually became Nwaubani Ogogo’s most trusted manservant. In the nineteen-forties, after my great-grandfather was long dead, Nwaokonkwo was accused of attempting to poison his heir, Igbokwe, in order to steal a plot of land. My family sentenced him to banishment from the village. When he heard the verdict, he ran down the hill, flung himself on Nwaubani Ogogo’s grave, and wept, saying that my family had once given him refuge and was now casting him out. Eventually, my ancestors allowed him to remain, but instructed all their freed slaves to drop our surname and choose new names. “If they had been behaving better, they would have been accepted,” my father said.

The descendants of freed slaves in southern Nigeria, called ohu, still face significant stigma. Igbo culture forbids them from marrying freeborn people, and denies them traditional leadership titles such as Eze and Ozo. (The osu, an untouchable caste descended from slaves who served at shrines, face even more severe persecution.) My father considers the ohu in our family a thorn in our side, constantly in opposition to our decisions. In the nineteen-eighties, during a land dispute with another family, two ohu families testified against us in court. “They hate us,” my father said. “No matter how much money they have, they still have a slave mentality.” My friend Ugo, whose family had a similar disagreement with its ohu members, told me, “The dissension is coming from all these people with borrowed blood.”

I first became aware of the ohu when I attended boarding school in Owerri. I was interested to discover that another new student’s family came from Umujieze, though she told me that they hardly ever visited home. It seemed, from our conversations, that we might be related—not an unusual discovery in a large family, but exciting nonetheless. When my parents came to visit, I told them about the girl. My father quietly informed me that we were not blood relatives. She was ohu, the granddaughter of Nwaokonkwo.

0 notes

Link

My parents’ home, in Umujieze, Nigeria, stands on a hilly plot that has been in our family for more than a hundred years. Traditionally, the Igbo people bury their dead among the living, and the ideal resting place for a man and his wives is on the premises of their home. My grandfather Erasmus, the first black manager of a Bata shoe factory in Aba, is buried under what is now the visitors’ living room. My grandmother Helen, who helped establish a local church, is buried near the study. My umbilical cord is buried on the grounds, as are those of my four siblings. My eldest brother, Nnamdi, was born while my parents were studying in England, in the early nineteen-seventies; my father, Chukwuma, preserved the dried umbilical cord and, eighteen months later, brought it home to bury it by the front gate. Down the hill, near the river, in an area now overrun by bush, is the grave of my most celebrated ancestor: my great-grandfather Nwaubani Ogogo Oriaku. Nwaubani Ogogo was a slave trader who gained power and wealth by selling other Africans across the Atlantic. “He was a renowned trader,” my father told me proudly. “He dealt in palm produce and human beings.”

Long before Europeans arrived, Igbos enslaved other Igbos as punishment for crimes, for the payment of debts, and as prisoners of war. The practice differed from slavery in the Americas: slaves were permitted to move freely in their communities and to own property, but they were also sometimes sacrificed in religious ceremonies or buried alive with their masters to serve them in the next life. When the transatlantic trade began, in the fifteenth century, the demand for slaves spiked. Igbo traders began kidnapping people from distant villages. Sometimes a family would sell off a disgraced relative, a practice that Ijoma Okoro, a professor of Igbo history at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, likens to the shipping of British convicts to the penal colonies in Australia: “People would say, ‘Let them go. I don’t want to see them again.’ ” Between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, nearly one and a half million Igbo slaves were sent across the Middle Passage.

My great-grandfather was given the nickname Nwaubani, which means “from the Bonny port region,” because he had the bright skin and healthy appearance associated at the time with people who lived near the coast and had access to rich foreign foods. (This became our family name.) In the late nineteenth century, he carried a slave-trading license from the Royal Niger Company, an English corporation that ruled southern Nigeria. His agents captured slaves across the region and passed them to middlemen, who brought them to the ports of Bonny and Calabar and sold them to white merchants. Slavery had already been abolished in the United States and the United Kingdom, but his slaves were legally shipped to Cuba and Brazil. To win his favor, local leaders gave him their daughters in marriage. (By his death, he had dozens of wives.) His influence drew the attention of colonial officials, who appointed him chief of Umujieze and several other towns. He presided over court cases and set up churches and schools. He built a guesthouse on the land where my parents’ home now stands, and hosted British dignitaries. To inform him of their impending arrival and verify their identities, guests sent him envelopes containing locks of their Caucasian hair.

Funeral rites for a distinguished Igbo man traditionally include the slaying of livestock—usually as many cows as his family can afford. Nwaubani Ogogo was so esteemed that, when he died, a leopard was killed, and six slaves were buried alive with him. My family inherited his canvas shoes, which he wore at a time when few Nigerians owned footwear, and the chains of his slaves, which were so heavy that, as a child, my father could hardly lift them. Throughout my upbringing, my relatives gleefully recounted Nwaubani Ogogo’s exploits. When I was about eight, my father took me to see the row of ugba trees where Nwaubani Ogogo kept his slaves chained up. In the nineteen-sixties, a family friend who taught history at a university in the U.K. saw Nwaubani Ogogo’s name mentioned in a textbook about the slave trade. Even my cousins who lived abroad learned that we had made it into the history books.

Last year, I travelled from Abuja, where I live, to Umujieze for my parents’ forty-sixth wedding anniversary. My father is the oldest man in his generation and the head of our extended family. One morning, a man arrived at our gate from a distant Anglican church that was celebrating its centenary. Its records showed that Nwaubani Ogogo had given an armed escort to the first missionaries in the region—a trio known as the Cookey brothers—to insure their safety. The man invited my father to receive an award for Nwaubani Ogogo’s work spreading the gospel. After the man left, my father sat in his favorite armchair, among a group of his grandchildren, and told stories about Nwaubani Ogogo.

“Are you not ashamed of what he did?” I asked.

“I can never be ashamed of him,” he said, irritated. “Why should I be? His business was legitimate at the time. He was respected by everyone around.” My father is a lawyer and a human-rights activist who has spent much of his life challenging government abuses in southeast Nigeria. He sometimes had to flee our home to avoid being arrested. But his pride in his family was unwavering. “Not everyone could summon the courage to be a slave trader,” he said. “You had to have some boldness in you.”

My father succeeded in transmitting to me not just Nwaubani Ogogo’s stories but also pride in his life. During my school days, if a friend asked the meaning of my surname, I gave her a narrative instead of a translation. But, in the past decade, I’ve felt a growing sense of unease. African intellectuals tend to blame the West for the slave trade, but I knew that white traders couldn’t have loaded their ships without help from Africans like my great-grandfather. I read arguments for paying reparations to the descendants of American slaves and wondered whether someone might soon expect my family to contribute. Other members of my generation felt similarly unsettled. My cousin Chidi, who grew up in England, was twelve years old when he visited Nigeria and asked our uncle the meaning of our surname. He was shocked to learn our family’s history, and has been reluctant to share it with his British friends. My cousin Chioma, a doctor in Lagos, told me that she feels anguished when she watches movies about slavery. “I cry and cry and ask God to forgive our ancestors,” she said.

The British tried to end slavery among the Igbo in the early nineteen-hundreds, though the practice persisted into the nineteen-forties. In the early years of abolition, by British recommendation, masters adopted their freed slaves into their extended families. One of the slaves who joined my family was Nwaokonkwo, a convicted murderer from another village who chose slavery as an alternative to capital punishment and eventually became Nwaubani Ogogo’s most trusted manservant. In the nineteen-forties, after my great-grandfather was long dead, Nwaokonkwo was accused of attempting to poison his heir, Igbokwe, in order to steal a plot of land. My family sentenced him to banishment from the village. When he heard the verdict, he ran down the hill, flung himself on Nwaubani Ogogo’s grave, and wept, saying that my family had once given him refuge and was now casting him out. Eventually, my ancestors allowed him to remain, but instructed all their freed slaves to drop our surname and choose new names. “If they had been behaving better, they would have been accepted,” my father said.

The descendants of freed slaves in southern Nigeria, called ohu, still face significant stigma. Igbo culture forbids them from marrying freeborn people, and denies them traditional leadership titles such as Eze and Ozo. (The osu, an untouchable caste descended from slaves who served at shrines, face even more severe persecution.) My father considers the ohu in our family a thorn in our side, constantly in opposition to our decisions. In the nineteen-eighties, during a land dispute with another family, two ohu families testified against us in court. “They hate us,” my father said. “No matter how much money they have, they still have a slave mentality.” My friend Ugo, whose family had a similar disagreement with its ohu members, told me, “The dissension is coming from all these people with borrowed blood.”

I first became aware of the ohu when I attended boarding school in Owerri. I was interested to discover that another new student’s family came from Umujieze, though she told me that they hardly ever visited home. It seemed, from our conversations, that we might be related—not an unusual discovery in a large family, but exciting nonetheless. When my parents came to visit, I told them about the girl. My father quietly informed me that we were not blood relatives. She was ohu, the granddaughter of Nwaokonkwo.

I’m not sure if this revelation meant much to me at the time. The girl and I remained friendly, though we rarely spoke again about our family. But, in 2000, another friend, named Ugonna, was forbidden from marrying a man she had dated for years because her family found out that he was osu. Afterward, an osufriend named Nonye told me that growing up knowing that her ancestors were slaves was “sort of like having the bogeyman around.” Recently, I spoke to Nwannennaya, a thirty-nine-year-old ohu member of my family. “The way you people behave is as if we are inferior,” she said. Her parents kept their ohuancestry secret from her until she was seventeen. Although our families were neighbors, she and I rarely interacted. “There was a day you saw me and asked me why I was bleaching my skin,” she said. “I was very happy because you spoke to me. I went to my mother and told her. You and I are sisters. That is how sisters are supposed to behave.”

Modernization is emboldening ohu and freeborn to intermarry, despite the threat of ostracization. “I know communities where people of slave descent have become affluent and have started demanding the right to hold positions,” Professor Okoro told me. “It is creating conflict in many communities.” Last year, in a town in Enugu State, an ohu man was appointed to a traditional leadership position, sparking mass protests. In a nearby village, an ohu man became the top police officer, giving the local ohu enough influence to push for reform. Eventually, they were apportioned a separate section of the community, where they can live according to whatever laws they please, away from the freeborn. “It will probably be a long time before all traces of slavery disappear from the minds of the people,” G. T. Basden, a British missionary, wrote of the Igbo in 1921. “Until the conscience of the people functions, the distinctions between slave and free-born will be maintained.”

0 notes

Photo

“I’m very much all about de colonisation and reconciliation and am glad that Harry and Meghan acknowledged the brutal history of commonwealth countries. Maybe they can put their money where their mouth is and help pay some reparations considering Harry would be nothing without colonisation” - Submitted by Anonymous

“Honestly Britain should pay reparations to the countries that it stole wealth from and to the people they oppressed and committed genocide against. Given how much money that would be I doubt it will ever happen but still I’m glad that a small discussion on reparations is finally being had thanks to Harry. As long as Harry is willing to also help pay considering how he’s directly benefitted from colonisation and slavery as a member of the royal family.” - Submitted by Anonymous

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"AFRICAN KINGDOMS SHOULD PAY REPARATIONS FOR SLAVERY," TOO. Openly Homosexual CNN Host DON LEMON Was Visibly Stunned When ROYAL COMMENTATOR HILARY FORDWICH Said, African Kings - Not British Royals - Should Pay Reparations For Slavery Because "THEY ROUNDED UP THEIR OWN PEOPLE AND HAD THEM WAITING IN CAGES ON THE BEACHES."

“AFRICAN KINGDOMS SHOULD PAY REPARATIONS FOR SLAVERY,” TOO. Openly Homosexual CNN Host DON LEMON Was Visibly Stunned When ROYAL COMMENTATOR HILARY FORDWICH Said, African Kings – Not British Royals – Should Pay Reparations For Slavery Because “THEY ROUNDED UP THEIR OWN PEOPLE AND HAD THEM WAITING IN CAGES ON THE BEACHES.”

CNN anchor Don Lemon interviewed Hilary Fordwich on the night of Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral. The anchor suggested the royal family should pay slavery reparations “AFRICAN KINGDOMS SHOULD PAY REPARATIONS FOR SLAVERY,” TOO. Openly Homosexual CNN Host DON LEMON Was Visibly Stunned When ROYAL COMMENTATOR HILARY FORDWICH Said, African Kings – Not British Royals – Should Pay Reparations For Slavery…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

CNN anchor Don Lemon interviewed Hilary Fordwich on the night of Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral. The anchor suggested the royal family should pay slavery reparations “AFRICAN KINGDOMS SHOULD PAY REPARATIONS FOR SLAVERY,” TOO. Openly Homosexual CNN Host DON LEMON Was Visibly Stunned When ROYAL COMMENTATOR HILARY FORDWICH Said, African Kings – Not British Royals – Should Pay Reparations For Slavery…

View On WordPress

0 notes