#Robertson Davies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It pleased me to hear the Ghost quote scripture; if we must have apparitions, by all means, let them be literate.

- Robertson Davies, “The Ghost who Vanished by Degrees”

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

El ojo ve sólo lo que la mente está preparada para comprender.

Robertson Davies.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gli scrittori amano i gatti perché

sono creature così tranquille,

amabili e sagge, e i gatti amano gli

scrittori per gli stessi motivi.

Robertson Davies

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend. -Robertson Davies

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I feel myself to be an angel, beating in ineffectual wings in vain against the granite fortress of your obtuse self-righteousness."

Robertson Davies, Tempest-Tost

#Robertson Davies#Tempest-Tost#witty quotes#funny quotes#frustration#self-righteousness#angel#Canadian literature#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend.”

― Robertson Davies

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

the medium is the message

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend.”

–Robertson Davies, Tempest-Tost (1951)

Photo by Antonio Palmerini

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

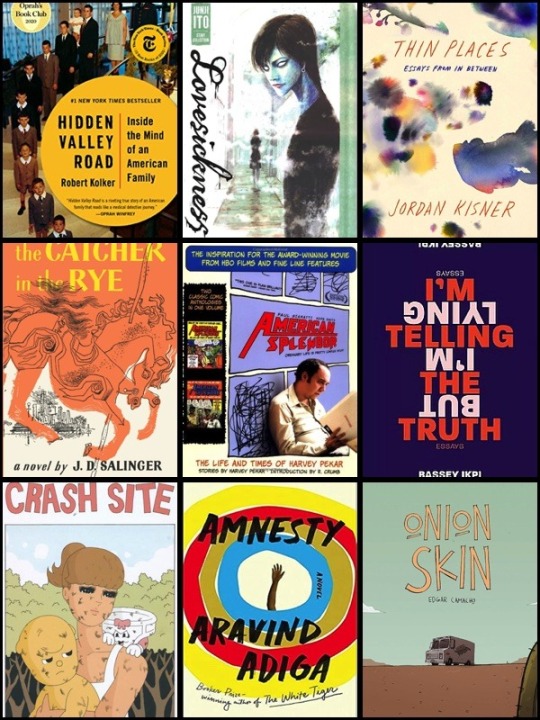

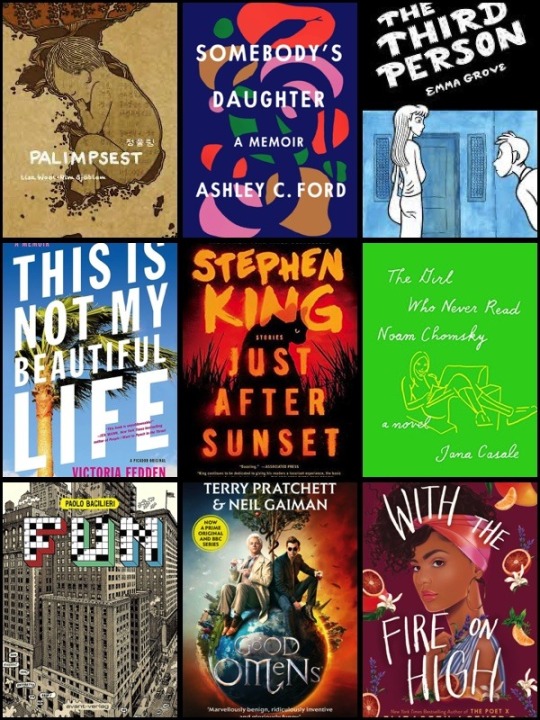

Another round of book reviews on this Wednesday evening.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

William Robertson Davies was a Canadian novelist, playwright, critic, journalist, and professor. He was one of Canada's best known and most popular authors and...

Link: Robertson Davies

1 note

·

View note

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Boredom and stupidity and patriotism, especially when combined, are three of the greatest evils of the world we live in.”

— Robertson Davies, “World of Wonders”

#robertson davies#literature lover#literature#lit#literature quotes#english literature#canadian literature#literature quote#philosophy quotes#philosophy#philosopher#philosophers#quote#quotes#excerpts#excerpt#book#books#bookworm#booklover#boredom#stupidity#patriotism

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

World of Wonders, a novel by Robertson Davies (1913–1995). (Macmillan of Canada, Toronto, 1975.)

#novel#fiction#literature#literary fiction#Canadian novel#Canadian fiction#Canadian literature#classics#Canadian novelist#bildungsroman#psychological fiction#fantastical#travelling sideshow#freaks#World of Wonders#Deptford Trilogy#Robertson Davies#book cover#book excerpt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

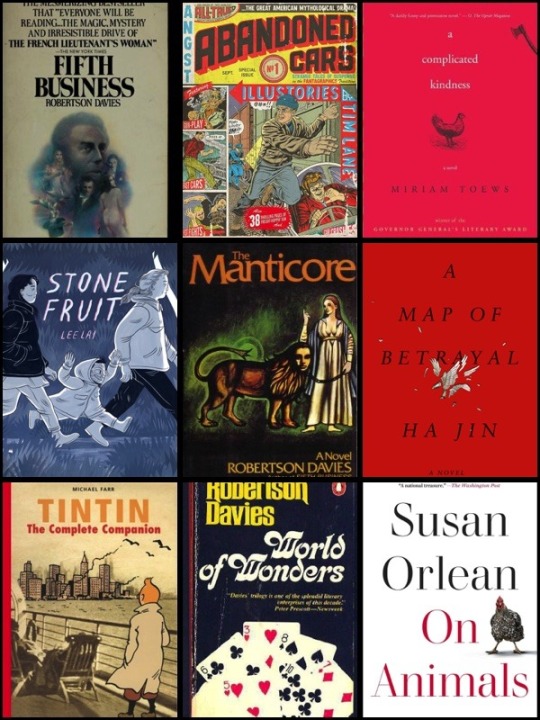

Books in 2022

Uncharacteristically for a midterm year, 2022 sucked. 2006, 2010, and 2014 hosted some of my happiest experiences, and even their worst parts were emotionally rich or educational. 2022 was mostly stagnant, interrupted only by misfortune: illnesses and deaths, harassment, personal and professional setbacks that started on January 2nd and continued through December 29th.

There were nice moments too – everyone should go to at least one Weird Al concert – but they’re obscured in my memory by the relentless slaps to the face. In that same way, when I look over the list of books I read in 2022, I recognize a lot of good titles, yet the overall vibe is one of disappointment. But there’s an unresolved question of cause and effect at hand: did a bad reading list contribute to the mediocrity of the year, or did my existing bad mood prevent me from enjoying these books? Is it the tale or the teller?

Fifth Business, Robertson Davies (Jan. 2-5)

The first volume of the “Deptford Trilogy.” Dunstan Ramsay, a retiring history professor, reviews his own life. The title comes from the narrator’s sense of himself as a supporting actor (neither “Hero, nor Heroine, Confidant nor Villain”) in the more riveting lives of others. Maybe you can already understand my interest in this character. The novel is sophisticated and perceptive about human behavior, and at the end, it reveals itself to have been beautifully plotted too. A thoughtless act by a nasty kid in Ramsay’s neighborhood turns out to have reverberated through generations, and it leads to a dramatic and frightening ending. Frightening because the events are so convincingly presented that you can well imagine an unwelcome conclusion like that rearing up in your own life.

Abandoned Cars, Tim Lane (Jan. 6-10)

Pulpy short stories drawn in a highly detailed, old-fashioned style. The drawings carry it. The writing isn’t bad, but it’s a lot of those, “lonely men, open roads, cigarettes, greasy spoons, crooners on the jukebox” kind of stories. A midcentury nostalgia that was picked clean a long time ago.

A Complicated Kindness, Miriam Toews (Jan. 9-16)

A teenaged Mennonite in Manitoba dreams of a more exciting life in New York City. I can sympathize with the heroine’s dreams, and I did like learning about Mennonite life, a world I know nothing about and the author knows intimately. But the details were ultimately so foreign to me that there was a limit to how much I could get into the novel. It’s hard to know how perceptive an observation is when you have no idea what’s being perceived. Still, people whose tastes I trust (my dad; the cartoonist Tim Kreider) admire Toews, so let’s call this my failure.

Stone Fruit, Lee Lai (Jan. 11-13)

At the start of the book, Ray and Bron are happy aunts to a six-year-old niece. But soon, their relationship ends, and they’re sunk into an unhappiness that’s not alleviated by the families they turn to. It’s all pretty bleak, but not unfairly so. The emotions the characters endure are realistic and earned, so while you might feel depressed at the end, you won’t feel manipulated. Plus, there are some great illustrations, particularly of the friendly monsters that the niece imagines while playing with her aunts.

The Manticore, Robertson Davies (Jan. 17-25)

The second part of the “Deptford Trilogy,” following David Staunton, the son of the rotten kid from the first book, as he undergoes Jungian analysis, a subject I know little about. But the little bit that I understand (or misunderstand), I like. It’s much more internal than Fifth Business, the scope is narrower, and the stakes are lower, but it’s just as intelligent and well-written.

A Map of Betrayal, Ha Jin (Jan. 26 - Feb. 1)

The main story is of Gary Shang, a double agent working for the CIA and passing information back to China while dealing with his American family and his conflicting loyalties. The framing story is of Gary’s daughter learning of her father’s past and reckoning with it. As usual, Jin’s insight into his characters’ emotional lives is terrific and effortlessly rendered. The details of this particular plot, however, are not quite so successful. Some of the set-up is unconvincing, and there are plot turns that feel sketchy. Not so much that you’ll have to put the book down, but don’t go in expecting another Waiting.

Tintin: The Complete Companion, Michael Farr (Feb. 2-21)

The second book I read to supplement 2021’s reread of the entire Tintin series. This one deals with the factual background for the stories and the artistic process by which Hergé wrote and drew each volume – as opposed to The Metamorphoses of Tintin, which I read two months earlier, and which took a more academic view. This book is beautiful to look at, featuring details of the series’ artwork and clippings from Hergé’s archives, but neither this nor Metamorphoses really deepens the pleasure of reading the actual books. Maybe what I’m looking for is a third path: a book that doesn’t take a technical or academic approach to the series, but rather an aesthetic and emotional approach. Maybe I should stop whining and write that book myself.

World of Wonders, Robertson Davies (Feb. 3-8)

The last book in the “Deptford Trilogy.” More like Fifth Business than The Manticore, this one again covers most of a lifetime – this time, of the magician Magnus Eisengrim, who is linked, from birth, to Dunstan Ramsey and David Staunton. This one ties up some of the remaining threads from the other two books, if that sort of thing is important to you, and it’s all about stage magic, something I always like reading about (in fact, this book lead me to seek out the one three spots down this list). On balance, it’s not as good as The Manticore, which itself is not as good as Fifth Business, but those are only relative markings. There’s no reason not to read all three.

On Animals, Susan Orlean (Feb. 9-15)

A collection of essays about domestic animals and wild animals. Though there are interesting stories of whales, tigers, and other majestic creatures, the essay that affected me the most was about homing pigeons, perhaps because their feats were the most beautiful to me. Because this is a collection of pieces written separately and later cobbled together, it doesn’t have the thematic strength that her single-subject books do, but it’s worth reading nonetheless.

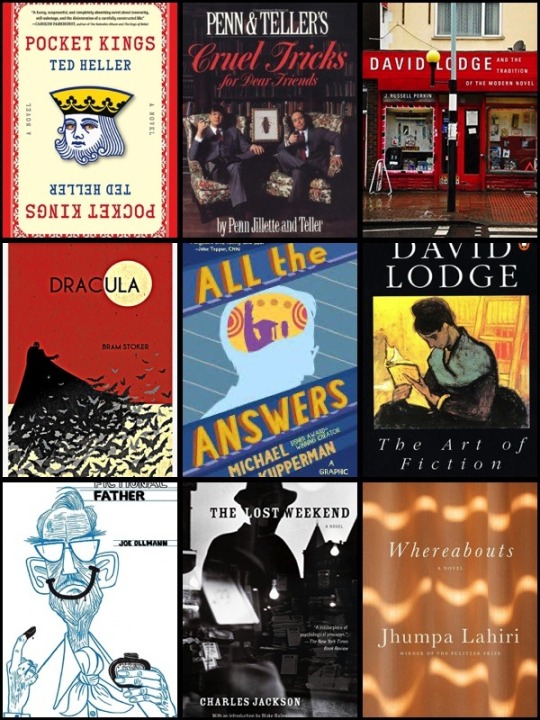

Pocket Kings, Ted Heller (Feb. 16-23)

A funny book about a stalled-out novelist who starts playing poker and becomes a relative success while the rest of his life falls apart. The plot doesn’t matter too much. You’re in it for the wittiness and intelligence of each individual paragraph. Towards the end, there’s a great section where we’re urged to reconsider the wisdom of a dozen pithy quotes by famous writers. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “There are no second acts in American lives” is challenged by the records of “Richard Nixon, Muhammad Ali, John Travolta, Bill Clinton or…F. Scott Fitzgerald.” There’s also a good joke when the narrator accuses the novelist Zoë Heller of leveraging her last name to mislead readers into thinking she’s related to Joseph Heller – a joke that became even better when I learned that Ted Heller is actually Joseph Heller’s son.

Penn & Teller’s Cruel Tricks for Dear Friends (Feb. 24-26)

When I was in high school, I read their other two books: How to Play with Your Food and How to Play in Traffic, both of which were full of worthy anecdotes and some magic tricks I’ve deployed throughout the years to mild approval. This one was less good. There are fewer interesting passages, and much of the book serves as a trick in and of itself. For example, half of the pages are illegible, printed in what the book itself calls, “itty bitty tiny irritating psycho-print,” so that it can be used as a prop in one of the tricks the legible pages teach you. Clever, but how can you not feel conned yourself when half of the pages are unreadable?

David Lodge and the Tradition of the Modern Novel, J. Russell Perkin (Mar. 3-7)

Another academic analysis of a favorite author, another unsatisfying read. Why do I keep picking these up? There’s nothing wrong with what Perkin says about David Lodge, and as members of the same relatively small fandom, I feel a kinship with him. But there’s no response possible to somebody else’s analysis besides (a) agreeing or (b) presenting a competing analysis. I hope he got an A for this thesis, but as a book, it does nothing for me.

Dracula, Bram Stoker (Mar. 7-17)

Foolishly, I wrote my own vampire stories before ever reading Dracula. I suppose I thought that, since the story has been absorbed into our collective consciousness, there was no need to read it. Maybe you feel that way. That is not so. It’s a very good book, even if it doesn’t surprise us the way it would have its first readers. It’s perfectly paced and vividly rendered, and, although the subject is masked by the nineteenth-century propriety of its language, I think you’ll be excited by how sexually charged the novel is. An early scene of the brides of Dracula descending on a victim will have you sweating.

All The Answers, Michael Kupperman (Mar. 11-14)

Michael Kupperman’s father was a boy genius who appeared on a panel show in the 1940s, answering tricky math questions. Being a child star was not a positive experience for him and he grew into a withdrawn adult, who never shared memories of his childhood with his son. Kupperman’s book is both a biography of his father and a memoir of his attempts to connect with a distant parent. In that sense, and because it’s a comic, it invites some comparisons to Maus, but that’s a pretty tenuous comparison. I only make it because the book doesn’t offer much to hold on to. Neither half of it is bad, but it never achieves escape velocity, perhaps because the father at the center of it all remains unknown to us and to Kupperman.

The Art of Fiction, David Lodge (Mar. 19-24)

A collection of newspaper columns from the novelist. In 50 entries, he discusses one element of the novel (opening lines, point of view, symbolism, the title, unreliable narrators, etc.), and illustrates his points with excerpts from modern and classical novels. It’s all very smart and very digestible, and if you’re trying to write a novel, you’d surely find some useful tricks to borrow. My favorite piece is the one on naming characters, in which Lodge cannily compares the deliberately suggestive names "Robyn Penrose" and "Victor Wilcox" in his own novel Nice Work to the name "Quinn" in Paul Auster's City of Glass. Quinn is a name that “flies off in so many little directions at once,” and if a name can mean anything, it ultimately means nothing at all – which, as Lodge rightly points out, is the point of that existential book.

Fictional Father, Joe Ollman (Mar. 19-23)

The story of a newspaper cartoonist who became rich and famous for his sappy father-and-son comic strip while ignoring and abusing his own son. This is a made-up story, but apparently – as Ollman himself only discovered after he’d written it – it’s very congruent to the real life story of Hank Ketcham, creator of Dennis the Menace. Though Ollman sees and draws out the real emotions of in this dynamic, his book is played mostly for laughs and is mostly successful. Lots of funny dialogue and a drawing style that makes everyone look laughable.

The Lost Weekend, Charles Jackson (Mar. 26-30)

The classic novel about a dissolute alcohol’s weeklong binge. The best scene is when he makes a half-joking/half-serious attempt to steal a stranger’s purse to fund his addiction. In addition to how well it works as a sad character study, it’s also one of those books that transports you to a bygone urban landscape – if you like that sort of thing, which I do.

Whereabouts, Jhumpa Lahiri (Mar. 31 - Apr. 4)

I find Lahiri’s work both irresistible and highly resistible. I like it because it’s so good, so intelligent, so precise, and so effective. I reject it because that same expertise leaves me feeling manipulated. It provokes an emotional response, yes, but because what’s provoked is always the only emotional response made available by the text, you have the sense that you’ve been moved from A to B to C without your input. A friend of mine says writing like this is akin to a sniper’s bullet: the marksmanship is incredible, but how good are you going to feel about the results? Oh, but this book in particular? It’s fine. A woman without a name wanders through a European city without a name, thinking. A little more diffuse and experimental than her other books, but in the end it feels…well, you know.

Amateurs, Dylan Hicks (Apr. 7-11)

I hardly remember this one. It was about a group of twentysomethings, tied together by threads of romance, thwarted romance, friendship, and competitiveness. Was there a wedding? A road trip to get to that wedding? I’m not sure. My recollection is that the book was good, not bad, but I have no evidence to back that up.

Don’t Come in Here, Patrick Kyle (Apr. 10)

A little comic book. Not much of a narrative. Just a showcase of trippy artwork, which wasn’t bad. What I remember most was returning this book to the library and it not being checked back in, obligating me to call up the circulation desk before I could be slammed with a humiliating late fee.

The Long Prospect, Elizabeth Harrower (Apr. 12-16)

An Australian novel about a young girl who lives a stifling life in a boarding house owned by her unpleasant grandmother. One boarder, a scientist, takes the girl under his wing. That’s the set-up, but I can’t animate any of the characters. Like Amateurs, the action of the book has been completely forgotten. Unlike Amateurs, the feeling that remains is not positive.

To Know You’re Alive, Dakota McFadzean (Apr. 14-15)

A collection of off-kilter, slightly spooky stories. There’s a cute one about how our culture might react if a boring alien landed on Earth, a creepy one about the discovery of a lost piece of children’s media, an eggheaded appraisal of Super Mario Bros. 2, and a silent nightmare with an inescapable cereal mascot. They’re all fun.

Let Us Be Perfectly Clear, Paul Hornschemeier (Apr. 16-17)

Another collection of short comics. The design of the book is clever. There are two halves: Let Us Be, printed from the front of the book to the middle; and Perfectly Clear, printed from the back of the book to the middle. But the stories themselves are less memorable than the package.

Hanging On, Edmund G. Love (Apr. 17-24)

Pulled off a library shelf at random, I think I may be the only person to have ever checked it out. A memoir of a being a teenager and sometimes college student in Michigan during the Great Depression. Though there are few highs and many lows when you grow up in that era, the book is a breezy, amusing read, so long as you don’t get hung up with resentment after learning that his tuition to attend the University of Michigan was only about $100 per year.

Carnet de Voyage, Craig Thompson (Apr. 21-23)

A little illustrated travel diary. Thompson wrote it while he was traveling around, promoting Blankets. It’s trifling, but fine. I had a stomach flu at the start of the year, so a sequence of Thompson suffering from food poisoning made me feel seen.

King of King Court, Travis Dandro (Apr. 24-28)

A very good memoir of childhood. It’s drawn in a chunky, juvenile style, but the material is pretty harrowing. Dandro’s dad was a heroin addict, his stepfather was an alcoholic, and his mom was understandably harried and overwhelmed. Dandro’s perspective is mature and empathetic, but he’s still able to recall and illustrate the feelings of fear and anger and shame that can arise in kids when they have unwelcome encounters with the adult world. It sounds like a painful read, but it’s not at all.

Remembering the Bone House, Nancy Mairs (Apr. 27 – May 5)

A memoir about the physical spaces Mairs has occupied: both houses and her own body. Her approach is scattershot, but I liked that. There’s a tendency towards loftiness and know-it-all-ism in memoirists (fair enough, given that the alternative is to concede that the stories from your life are meaningless, in which case, how self-indulgent is it to publish them?), but Mairs avoids it. She presents her book with the attitude that writing is not the summation of life, but just another action taken by the living. Illustrating that point is a moment where she writes of publishing a personal essay about her affair and discovering that, contrary to what she thought, her husband didn’t know about it – until he read the printed story.

Nutshell, Ian McEwan (May 7-11)

Told from the perspective of a fetus, as he listens in on the sinister machinations and plotting of his mother and her lover. It’s clever and the high concept doesn’t wear thin. Embarrassingly, I didn’t realize until I had finished the book that it was retelling the story of Hamlet, even though the title comes from one of the only lines of that play I can confidently quote.

Level Up, Gene Luen Yang & Thien Pham (May 11-12)

The main character’s strict father won’t buy him a Nintendo Entertainment System. When the father dies, the hero buys an NES, and develops a passion for video games that becomes a crutch whenever he falters in life. Eventually, he’s set upon by some cherubs or angels who act as his guilty conscience, obliging him to follow his late father’s wishes for him. The main idea here – the hero’s challenge to find his individual happiness without disappointing or disrespecting his family – is handled well, but I can’t help but wish that video games hadn’t been the subject the story was spun around. I like video games, and respect their intelligence and artistic merit…but every time people try to transplant them into another medium, the operation is a failure, and the subject dies on the table.

The Unconsoled, Kazuo Ishiguro (May 12-21)

A book that tries your patience, if it’s possible to say that without being totally negative. A pianist arrives in a new city in advance of a concert and is soon dragged all over the city for endless, perplexing meetings and chores. The story is presented like a dream, where characters pop up randomly, and locations can be endlessly distant in one moment and right around the corner in the next. The thing is, dreams are always more interesting to the dreamer than to any audience, so the book can be frustrating at times, even if you accept its structure. Still, it’s impressive that he pulled off such a stunt for 500 pages, and the quality of Ishiguro’s prose is bright and beautiful as always.

Perchance to Dream, Charles Beaumont (May 23-29)

Twilight Zone-esque tales from a writer for The Twilight Zone. Actually, many of the stories in this book became scripts for that show. But they work in either medium. The best is “The Howling Man,” about a traveler in Europe who comes across a group of monks who are keeping a strange prisoner. Inventive and tidy and not bogged down by any need for meaning, these are the sort of stories I’ve been trying to write recently.

Passport, Sophia Glock (May 28-30)

As a teenager, Glock discovered that her secretive parents were actually spies working for the CIA. I think that’s the set-up for Spy Kids, but this book goes in a less bombastic direction. It’s a fairly conventional coming-of-age story, as Sophia makes friends and enemies, goes out to parties, and learns to accept herself. It’s okay, and there’s something amusingly anticlimactic about the irrelevance of her parents’ profession to Glock’s own story, but you won’t be mesmerized by this book.

The Resisters, Gish Jen (May 30 - June 2)

A baseball prodigy tries to find happiness in a dystopian future. I sped through this book, surprised at how tolerable it was, but by the end, my general disinterest in dystopian stories won out. The nod-your-head-sadly parallels to our current culture are more wearying than enlightening. The baseball scenes are okay, though. That sport translates well to the page.

Come Along With Me, Shirley Jackson (June 4-9)

The title comes from an unfinished novella included in this collection, but it and every other story are overshadowed by “The Lottery,” which is as good as its reputation holds. The next best inclusion is Jackson’s essay about the reception “The Lottery” got. In addition to the reams of letters from people incapable of understanding that her story was fictional and convinced that there really did exist a small town that committed ritual stoning, she received a fawning letter, to which she politely responded, “I admire your work, too,” only to discover that she had responded to an accused axe murderer. On the far opposite end, this collection also has “Pajama Party,” a cute domestic comedy about a child’s first sleepover. I liked that one too.

Twists of Fate, Paco Roca (June 9-11)

I’ll compare this one to Maus too, and I’ll be on firmer ground: a comic book about a young man painstakingly drawing out the war stories of an elderly man. The man fought against the Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War, fled to Algeria, joined the Allied forces, and was party of the forces that liberated Paris from the Nazis. But he was never able to return to Spain to liberate it from Franco, a regret that gnaws at him, even at age 94. That’s a good story, and it digs into some underexposed history, but I was never fully convinced of the need for the framing device.

Memoir of a Gambler, Jack Richardson (June 12-19)

A little bit like a non-fiction version of Pocket Kings. After his divorce, Richardson crosses the country, and eventually the globe, playing poker in high and low places. There’s not a lot of happiness in this world, and Richardson does nothing to change that, but his cold and precise rendering of his adventures (and really, they are adventures: he’s not just sitting at the tables for the whole book) are entrancing. His description of the geography of Las Vegas – which, by chance, I was reading as I flew into Las Vegas – should on its own be enough to shut down the city.

Hidden Valley Road, Robert Kolker (June 21-25)

The true story of a large family in Colorado Springs, some of whom were acquainted with my uncles. There are 12 children, and half of them are ultimately diagnosed with schizophrenia, leading to much grief but ultimately making the family a fruitful source of data for medical researchers. It’s a sad book, and like all good documentaries, it makes you feel guilty for being witness to what you’re seeing.

Lovesickness, Junji Ito (June 24-26)

A collection of unsettling, grotesque comics. Exactly what I was expecting and hoping for when I picked it up, yet I was unmoved by the collection. The territory is just the same as in Uzumaki, which I’d read the year before, but as a set of independent (rather than linked) stories, the material doesn’t have a chance to develop an insidious feeling or any thematic resonance. It’s more a series of satisfactory but forgettable shocks.

Thin Places, Jordan Kisner (June 27 – July 3)

These are the sort of essays all NYU freshman are taught to write: pick three or four subjects – usually a selection from personal experience, history, a piece of art, and an event, place, or occurrence in our culture – and juxtapose them in every pairing until you reach your page count. It’s a very mechanical process, and my experience being taught it left me prone to resist this form. And yet I liked this collection well enough. Kisner is honest, most of her insights are well-articulated, and though there’s no humor in these essays (the form won’t allow it), she doesn’t fill that vacuum with pretension, as my classmates and I always did.

The Catcher in the Rye, J.D. Salinger (July 6-9)

There’s a party game called Humiliation, where you reveal that you've never actually encountered some huge culture monument, and you get points for each person at the party who has. For a long time (still, in fact), I could say I’ve never seen Titanic and scoop up a bunch of points. That was my go-to because I was too embarrassed to confess to an even bigger miss: I had never read The Catcher in the Rye. It’s a wonderful book, though. Very funny and very moving. What surprised me was how much I admired Holden Caulfield. I don’t just mean that I understood and accepted his adolescent angst. I actually think he’s a noble person. His anger may sometimes be misplaced and his sense of righteousness can be overly dogmatic, but those are habits that usually pass with age, and what will be left is the sensitivity, intelligence, and moral strength that’s plainly evident beneath his clumsy exterior.

American Splendor: The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar, Harvey Pekar, et al. (July 7-13)

Autobiographical comics by another admirable grouch. I had never read any American Splendor stories before, maybe because their multiple art styles (Pekar wrote the comics but had a variety of other artists draw them) seemed wearying to me. And truthfully, that quality still does nothing for me. But the writing is great. The stories vary in subject and length and presentation, but every one of them is closely observed and intelligent about the way people talk and act and think. The ordinariness of life (and of Cleveland) is rendered with extreme beauty. And Pekar himself is a great hero. Another noble crank who’s critical and passionate and full of fury, yet never unkind and never less than generous.

I’m Telling the Truth, but I’m Lying, Bassey Ikpi (July 10-13)

A pain-filled memoir, this one about bipolar disorder, disassociation, and the Challenger explosion. It’s mostly engaging, though there are parts in the back half where useful details seem to be missing and it becomes hard to follow. Given the subject matter, this may not be unintentional.

Crash Site, Nathan Cowdry (July 14-15)

Edgelord stuff run through several layers of irony. Lots of violence and provocative dialogue stacked up in such a way that it’s impossible to tell whom the author is trying to provoke: those who would take offensive or those who would deny the validity of being offended. I sort of see the point, and I didn’t hate the book. But at a certain point, you wish Cowdry would stop fooling around and just write a real story.

Amnesty, Aravind Adiga (July 16-19)

A young migrant worker in Sydney comes across a murder. If he reports it, he risks deportation, a fact that the murderer is all too happy to rub his nose in. It’s a good blend of a thriller and a social commentary. I also liked that fact that it was taking Australia and its cultural values to task. Not that I personally have anything against Australia, but it’s a country that you rarely see condemned, so I appreciated getting to reading a rare (and surely well-deserved) scolding.

Onion Skin, Edgar Camacho (July 17-18)

The story of a couple that runs a food truck and finds themselves in a turf war. It holds your attention while you’re reading it, but it’s a mess, jumping around in time and in tone. Plus, the relationship at its center is very tired: a mopey guy finds his life reinvigorated by a free-spirited girl. The food looked good, though.

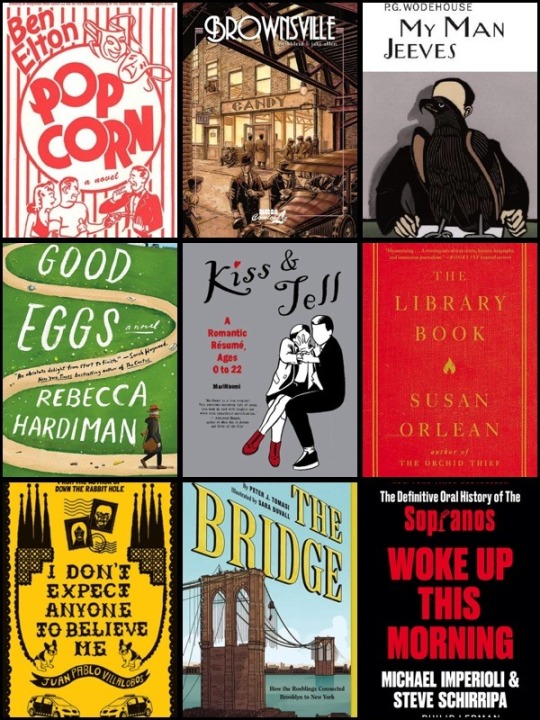

Popcorn, Ben Elton (July 21-24)

A Hollywood satire written by a Brit, so it has that some of the stiffness and artificiality that can come in when writers try to cross the pond. But on the whole, it’s funny and astute about the industry. The ending overemphasizes its lessons, but I liked that Elton didn’t shy away from the mayhem he’d been teasing.

Brownsville, Neil Kleid & Jake Allen (July 22-23)

The familiar story of growing up in New York, being attracted to the mafia, and eventually joining it. The twist this time is that it’s the Jewish mafia. Interesting? Not really. That detail hardly changes anything, so the arc and most of the individual scenes in this book are rote in conception and in execution. Your favorite mafia story, whatever it is, will give you as much as this book and more.

My Man Jeeves, P.G. Wodehouse (July 29 - Aug. 1)

An early and unpolished collections of short stories. Given that Wodehouse later rewrote most of these pieces, the decent thing to do might have been to let this collection go out of print. Fewer laughs than Wodehouse usually provides, though there are still a couple of big ones, such as one character’s passing idea to make money by selling anarchists and other dispossessed people the opportunity to beat up his rich uncle.

Good Eggs, Rebecca Hardiman (Aug. 6-10)

A warm-hearted comedy about an Irish family. There’s the grandma who keeps making trouble, the rebellious teen with a soft, sentimental center, and the harried father caught in between the generations, trying to keep everything running smoothly. Eventually, they’re all put on the same side of the field when they have to take on an American who’s scammed them. It’s nothing remarkable, and I didn’t laugh too much – perhaps not at all – but sometimes it’s enough if a book features one element close to your heart. In my case, it was the suburban Dublin setting.

Kiss & Tell: A Romantic Resume, Ages 0 to 22, MariNaomi (Aug. 9-11)

A catalog of intimate relationships ranging from crushes to long-term relationships. To some degree, it’s all contextualized by its setting (the Bay Area in the 1980s and 90s), and by how the author views her relationships in comparison to that of her parents. But mostly, it’s just a list, and one that becomes quickly repetitive.

The Library Book, Susan Orlean (Aug. 11-14)

Possibly a perfect non-fiction book. In 1986, a fire broke out at the main branch of the Los Angeles Public Library, wiping out 20% of its collection. Orlean covers that disaster and it subsequent investigation, but she also makes room for the history of the LAPL, discourse on the function of libraries in America, personal reflections, academic theorizing, and science experiments (the chapter about her own attempt to burn a book is one of the best parts). The arson at the heart of this story is compelling enough to make this book good in anyone’s hands, but in Orlean's, it’s great.

I Don’t Expect Anyone to Believe Me, Juan Pablo Villalobos (Aug. 16-21)

Another fun mash-up. This time the blend is crime thriller, campus novel, and metafiction. Juan Pablo is a Mexican student who is abducted before leaving to study abroad in Spain, and ordered to get close to a corrupt politician by falling in love with his daughter. The plot is knowingly ridiculous and, though you eventually give up on trying to follow it, it’s amusing all the way through. There’s also a fun essay at the end, in which the translator explains his difficulty in capturing the voices of the different narrators, conceding with admirable frankness that he’s not sure he succeeded.

The Bridge, Peter J. Tomasi and Sara DuVall (Aug. 17-20)

The true story of the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. If you don’t know it already, the fun detail is that the chief engineer became overworked in the middle of construction, and spent the rest of it monitoring the bridge’s construction from his bed while his wife took over as de facto leader at the job site. The standard details of how to build an enormous bridge are also fun to learn about, and the authors do a good job making you share in the stress of the workers deep below the water.

Woke Up This Morning, Michael Imperioli, Steve Schirripa, and Philip Lerman (Aug. 23-28)

An oral history of The Sopranos cobbled together from the podcast Imperioli and Schirripa started a few years ago. That show is endlessly discussable, and the book has a few funny stories and some thoughtful analysis, and it’s certainly better to read this book than to listen to the podcast (did I tell you I’ve declared a war on podcasts?), but I don't know…I found myself growing less and less interested the more I read. Once the initial fun of being a fly on the wall passed, I recalled that The Sopranos is strong enough to speak for itself.

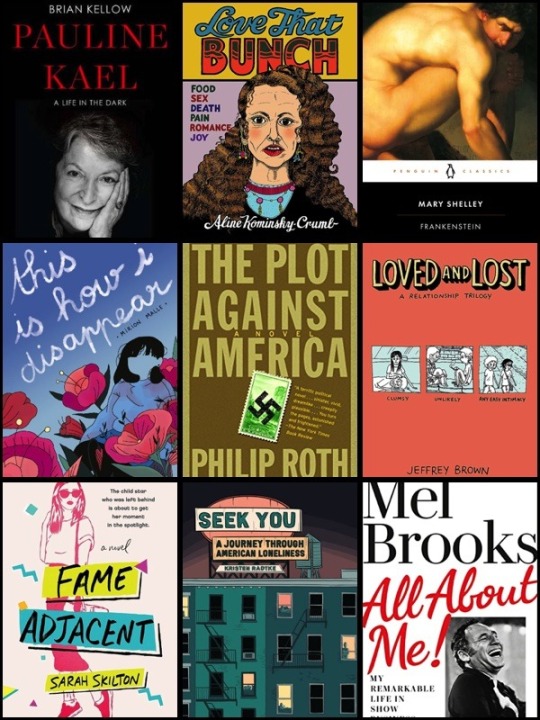

Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark, Brian Kellow (Aug. 30 - Sep. 4)

A thorough biography that features and contextualizes lots of excellent film reviews by Kael. It also reveals some of her astonishing lapses of ethics. In 1971, she published, “Raising Kane,” an essay about the authorship of Citizen Kane’s screenplay. It’s a terrific piece of writing, but it’s extremely shoddy journalism that has since been disproven. Even worse, much of her research was stolen from a UCLA professor, whom she never credited. It’s a shocking revelation and Kellow presents it without excuses. That chapter alone is worth the price of admission.

Love That Bunch, Aline Kominsky-Crumb (Sep. 2-5)

Autobiographical comics from one half of an underground comix power couple. A relationship that’s mostly been presented through her husband Robert Crumb’s eyes is shown here from Kominsky-Crumb’s perspective instead. But the thing is, they’re a very well-matched couple, so their perspectives aren’t all that different. And honestly, neither of their styles are terribly interesting to me, accomplished though they are. Still, you can admire Kominsky-Crumb’s pioneering efforts, and she and her husband and their unconventional family are pretty cute, no matter how repellant this book tries to make them seem.

Frankenstein, Mary Shelley (Sep. 6-10)

Another classic that I’m only just now getting around to. A hair less interesting than Dracula – the old-fashioned formality of the writing makes it a less ripping read – but still great. Dr. Frankenstein and his monster are both fascinating and complex, and the whole story is genuinely haunting and ambitious in scope. The framing device of the Arctic voyagers who witness the end of Frankenstein’s story seems impossibly contemporary. Considering how young Shelley was when she wrote something so good, hers may be the greatest accomplishment in the history of literature.

This is How I Disappear, Mirion Malle (Sep. 10-12)

Another mental health story. Because this one is done as a comic, not as prose, it can place us immediately into the shoes of its protagonist and let us feel her pain, which is a point in its favor. Working against it is the abundance of scenes, dialogue, and plot points driven by text messages and social media messaging. As always happens when those elements are spotlighted in a story, they dial the energy of the book down to nearly zero. (I'm not letting myself off the hook: I've tanked my own pieces that way.) That technology is an important part of our lives and our culture, and someday somebody will find a way to mill it into art, but it hasn’t happened yet.

The Plot Against America, Philip Roth (Sep. 11-17)

It had been nearly 15 years since I read anything by Roth. This was a good one to restart with. An alternate history of Roth’s childhood if the United States had elected Charles Lindbergh over FDR in 1940. The family drama and the political drama are equally engaging, and Roth even leans into the ridiculous fun of speculative fiction with a big, ludicrous twist in the last fifth of the book that guides everything to a satisfying resolution.

Loved and Lost, Jeffrey Brown (Sep. 14-18)

Three graphic novels covering three of Brown’s formative romances. Sincere, but sort of wimpy. I don’t want to cross a line and start critiquing anybody’s personal emotional repertoire – I’m just talking about what’s recorded on the page. The happy moments we see of his relationships are moments of quiet companionship. There’s almost nothing about adventures or inside jokes or mutual discoveries – the exuberant parts of a relationship. Quiet companionship is an important part of love too, and if that’s the pitch at which Brown lives his life, there’s nothing wrong with that, and he should record it accurately. But the pleasure of reading about it is faint.

Fame Adjacent, Sarah Skilton (Sep. 20-24)

A fun and original novel. The narrator is a former child actor, the only one from her troupe of singers and dancers not to become famous. The first part of the book has her in rehab for her internet addiction. The second part has her road-tripping to New York for a reunion with her castmates. It’s a lively book (a quality in short supply in too many novels), and I want to commend Skilton for pulling off a trick that’s harder than you might think: the fake TV show that she creates is credible. Often the fictional media contained within books (and TV shows and movies, for that matter) seems either implausible – we don’t believe a TV show so described would ever air – or like a poorly disguised version of an existing piece of media – distracting us as we look for the Easter eggs in this universe’s version of Seinfeld. But Skilton’s invention (Diego and the Lion’s Den) is totally believable, and its details are nicely fleshed out.

Seek You, Kristen Radtke (Sep. 21-25)

Another bit of brainy graphic essaying by Radtke. The subject is loneliness – Radke’s and America’s. Surrounding the personal reflections, there is a lot of well-synthesized research and bright analysis. And how about this for a good definition to carry with you: “Loneliness isn’t necessarily tied to whether you have a partner or a best friend or an aspirationally active social life. It’s a variance that rests in the space between the relationships you have and the relationships you want.” My only complaint is about a section where, talking of television sitcoms, she blurs the important distinction between canned laugh tracks and the laughter of live studio audiences – but that’s only a personal hang-up of mine.

All About Me!, Mel Brooks (Sep. 25 - Oct. 1)

A very happy memoir by a very happy guy. Lots of warm stories stretching from his childhood to his dotage, and some triumphant moments where he outwits boneheaded Hollywood executives. He’s justly proud of his own talents and achievements, but he spends more of the book heaping genuine, specific praise on other actors and writers he’s worked with. Tellingly, the only colleague who’s recollected with even the slightest negativity is Jerry Lewis…

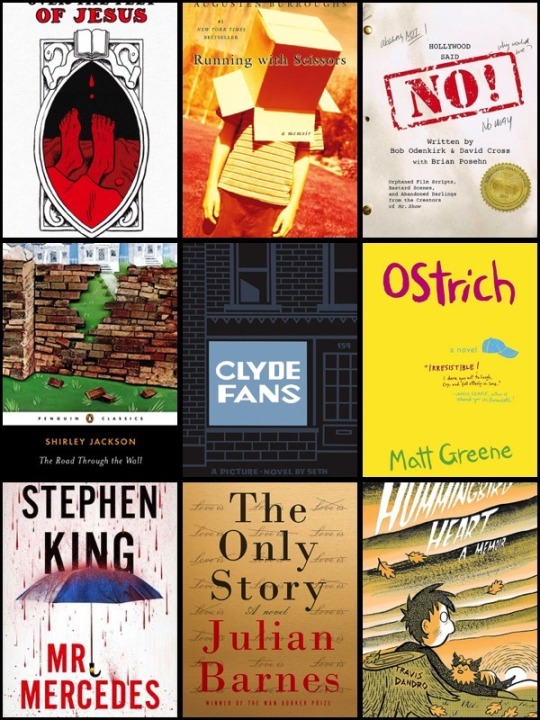

Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus, Chester Brown (Oct. 1-3)

An illustrated collection of stories from the Bible that Brown believes evince a pro-sex work attitude in early Christianity. As somebody with almost no preexisting feelings about the Gospels, I’m an easy mark for any interpretation. Brown, who has spent the last 25 years visiting prostitutes, is not exactly a detached analyst here, but whatever his motivations for writing this book, his evaluation of the Bible’s text is convincing enough. The trouble for me was that, irrespective of their political meaning, I found the Gospel stories themselves distasteful and unkind.

Running with Scissors, Augusten Burroughs (Oct. 2-4)

The blurbs all compare him to David Sedaris, but that’s inapt. There’s nothing funny about Burroughs’ story, and the comparison seems to me like laziness, an inability to distinguish two very different types of memoir. With that pedantry out of the way: this is a good book. As a teenager, Burroughs is put in the care of his mother’s psychiatrist, a dangerous blowhard who keeps a filthy and miserable home. Burroughs witnesses and endures a lot of horrors over the course of five years, and though he’s never self-pitying nor seeking of praise, I did feel admiration for his escape and his ability to transmogrify his life into art.

Hollywood Said No!, Bob Odenkirk & David Cross with Brian Posehn (Oct. 6-8)

Two never-produced screenplays and other sundry material by some of the brains behind Mr. Show. Not their best work, but I smiled a lot while reading it. I did object, however, to their attacks on Jamie Kennedy, towards whom I feel an odd and misapplied sense of protectiveness.

The Road Through the Wall, Shirley Jackson (Oct. 8-14)

Jackson’s first novel, in which she exposes the ugliness, prejudice and misery beneath the surface of a privileged upper-class neighborhood. That’s pretty shopworn material these days, but remember: she did it in 1948. The novel is decent – I liked the scene where two teenagers seek a transgressive thrill but the best they find is a secret tea party with a butler – and the gruesome ending does still shock. But it’s weighed down by having too many indistinguishable characters.

Clyde Fans, Seth (Oct. 14-17)

A meticulously drawn book about a generational struggle to keep open a family business. The artwork is impressive, but I just can’t summon up any enthusiasm for this story and its themes: the agony of being a salesman, the inability of men of a certain generation to share their feelings, and more of that midcentury nostalgia I complained about earlier.

Ostrich, Matt Greene (Oct. 15-17)

A 12-year-old boy with brain tumor narrates an otherwise typical story of growing up (parents, friends, school, burgeoning sexual feelings). There are some clever and funny lines, but I grew less and less convinced I was hearing the honest voice of a child as opposed to the practiced remarks of a novelist.

Mr. Mercedes, Stephen King (Oct. 20-29)

A retired detective is taunted by a murderous psychopath and begins a private investigation to catch the killer. My hopes for this one weren’t quite met. The plotting is fine, and some tension builds well in the last act, but none of the characters feel like more than placeholders, and the gruesome details (particularly in the killer’s backstory) are nowhere near King’s best. Also, King’s efforts to write dialogue for a Black teenager result in some embarrassing lines that I won’t quote here.

The Only Story, Julian Barnes (Nov. 4-9)

I picked it up because it was about tennis, and discovered that Barnes was an author I should have been reading for years. A man recounts his “only story,” of being a college student home for the summer and falling in love with a middle-aged woman he’s partnered with for a game of doubles. The direction the story takes doesn’t matter. What I liked about the book was how intelligently and unpretentiously Barnes writes, and how deeply he digs into important questions. The book opens with, “Would you rather love the more, and suffer the more; or love the less, and suffer the less? That is, I think, finally, the only real question.” And before you have a chance to reflect on how well put that is, Barnes challenges himself: “You may point out—correctly—that it isn’t a real question. Because we don’t have the choice…if you can control it, then it isn’t love.” The array of thoughts those four sentences evoke would be accomplishment enough for most novelists, but it’s only the first of many treats Barnes offers.

Hummingbird Heart, Travis Dandro (Nov. 5-7)

The sequel to King of King Court, picking up on Dandro’s life as he hacks his way through his teen years. All of the praise-worthy qualities of the first book are present…but less so. The intelligence of the writing and the appeal of the drawing style are still there, but the subject is less interesting, more well-worn: shoplifting teenage boys learning to put aside their anger and face the fact that they must grow up. It’s done well, but only well, and Dandro's previous book set the bar higher.

Palimpsest, Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom (Nov. 9-12)

A very angry memoir of an adoptee seeking out her roots. The author directs anger at her adopted country, at her country of birth, at bureaucrats from all over, and at herself. All of which is well-earned, and the point that Sjöblom makes early on is that she wishes to counteract the rosy prevailing narrative of the experience of international adoptees. I would push back slightly by noting that Sjöblom sometimes seems to not just want to dismantle that narrative, but to replace it with one that’s equally overbroad – her own – not realizing that that would be just as limiting. But that minor quibble aside, this is worth reading.

Somebody’s Daughter, Ashley C. Ford (Nov. 12-16)

There’s a lot of trauma recounted in this memoir of growing up with an abusive mother and an incarcerated father, and Ford renders it all calmly and dispassionately, yet still with a keen memory of the pain she felt. If you can handle that sort of material, this book offers it about as well as it could be done. And Ford shares a few memories that stick with you long after the book is done, like a scene of her grandmother setting ablaze a nest of snakes.

The Third Person, Emma Grove (Nov. 16-20)

This one sneaks up on you, and soon, you’ll be flying through its 900 pages. Grove is a transgender woman visiting a therapist to be approved for hormone therapy. As the sessions progress and Toby the therapist learns more about Grove and her past, he begins to think that she may have Dissociative Identity Disorder, which he feels must be addressed prior to any other medical care. The drawing style is simple and flat, and much of the book is given over to repetitive scenes of therapy sessions, which may sound boring, but it’s actually very easy to become absorbed in their discussions. And the therapist isn’t just a prop to give Grove somebody to talk to; he’s a real character whom we see as clumsier and more unprofessional the longer the book goes on.

This Is Not My Beautiful Life, Victoria Fedden (Nov. 17-20)

While Fedden was pregnant and staying with her family in Florida, her parents’ house was raided by the feds. This memoir touches on her dysfunctional family, their legal travails, and the goofy (and, to my eyes, could-not-be-less-desirable) experience of living in Florida. The details of her family’s unique experiences give the book some early momentum, but the humor doesn’t progress beyond zaniness, and eventually, the book spins off in fragmentary, underexplored directions in an unsuccessful search for a point.

Just After Sunset, Stephen King (Nov. 24-30)

I broke my informal rule and read more than one Stephen King book in 2022. This one is a collection of stories, and it’s more successful than Mr. Mercedes. There are 13 stories, and at least nine of them work. Particularly good are “Stationary Bike,” one of those tales about a living painting; “The Gingerbread Girl,” about an obsessive runner; and N., an old-fashioned novella about a psychiatrist who takes on his patient’s obsession.

The Girl Who Never Read Noam Chomsky, Jana Casale (Dec. 1-8)

A highly internal novel about a Millennial in Boston who aspires to be a writer. No, don’t run away: this one is actually good. Leda, the protagonist, is seen in a number of quiet, precise vignettes, moving through college and her early 20s, trying to be a friend and a lover and a daughter and a romantic partner. I thought I’d had my fill of these stories (both from other books and from my own droning life), but I found room to let this one in. My interest waned in the last third, once the character grows up and we accelerate through her adulthood and old age, but up until then, it’s absorbing.

Fun, Paolo Bacilieri (Dec. 2-5)

A graphic novel about the history of the crossword puzzle, woven around a knowingly melodramatic mystery, all told in a vaguely meta style. It’s pretty busy, and though it delivers on the fun promised in the title while you’re reading it, it doesn’t stick with you.

Good Omens, Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman (Dec. 10-15)

A book my mom was recommending to everyone 25 years ago. An askew story of the Antichrist being swapped at birth and of the junky Armageddon that follows. It’s cute and funny, and though I get a little impatient with British whimsy these days, it's well-deployed here. The cast is so sprawling that it becomes a little unwieldy – this is probably an asset in its miniseries adaptation – but there aren’t any characters whose sections you dread.

With the Fire on High, Elizabeth Acevedo (Dec. 23-29)

The first young adult novel I had read in many years, about a high school senior with a talent for cooking who must learn to trust in and prioritize her own dreams. It had been a while since I read a book with a lesson, and shifting gears took some time. But once I did, I was happy to go along and cheer the main character’s triumph. I read most of this book on a six-hour train ride through California’s Central Valley, seated next to a man without a neutral odor, so its many descriptions of aromatic food were very welcome.

***

It was not my favorite year of reading, but curiously, I read more books in 2022 than in any other year since I’ve been keeping track. Maybe it was overextension that led to a less positive experience. Maybe my mood was brought down by two or three too many painful memoirs. Or maybe I should just internalize the lessons of Ted Heller and Jack Richardson, and accept that sometimes life deals you a bum hand. That can be true of a year or of a reading list.

But I did discover those two authors. And finally mark off Dracula, The Catcher in the Rye, and Frankenstein. And one Susan Orlean makes up for a hundred Brownsvilles. In order to maintain my enthusiasm for writing in the face of the constant beatings 2022 offered, I had to accept the old lesson about taking pleasure in the creative act itself and not being preoccupied about where the final product would lead me. That equanimous outlook is just as useful pointed towards the writing of others, remembering that, whatever the yearly average turns out to be, the pleasure of reading any one good book is never diminished.

#reading list#robertson davies#tim lane#miriam toews#lee lai#ha jin#susan orlean#penn and teller#bram stoker#david lodge#michael kupperman#joe ollman#charles jackson#jhumpa lahiri#dylan hicks#elizabeth harrower#dakota macfadzean#paul hornschemeier#edmund g love#craig thompson#travis dandro#nancy mairs#ian mcewan#gene luen yang#thien pham#kazuo ishiguro#charles beaumont#sophia glock#gish jen#jd salinger

3 notes

·

View notes