#Rio Grande & Colorado Rivers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rocky Mountain High

Can Anyone Blame Texans? The Texas heat gets turned up now, and in so many ways. How about a few videos that are as raw as a hot July chapped butt on horseback. These were never uploaded to YouTube – If you were wondering, there were some great times along the way and in the Rockies. There are more, but here are a few …

#flyfishing#texasflyfishing#colorado#fly fishing#raw video#rio grande reservoir#Rio Grande River#Rocky Mountain fly fishing#vintage video

0 notes

Text

(Based on the 12 largest primary rivers by watershed area)

#polls#mississippi#mississippi river#Mackenzie river#st lawrence#Nelson river#yukon#yukon river#columbia#Columbia river#colorado river#rio grande river#Churchill river#fraser river#Sacramento river

0 notes

Text

Environment: Every Drop Counts in America’s Waterways Crisis

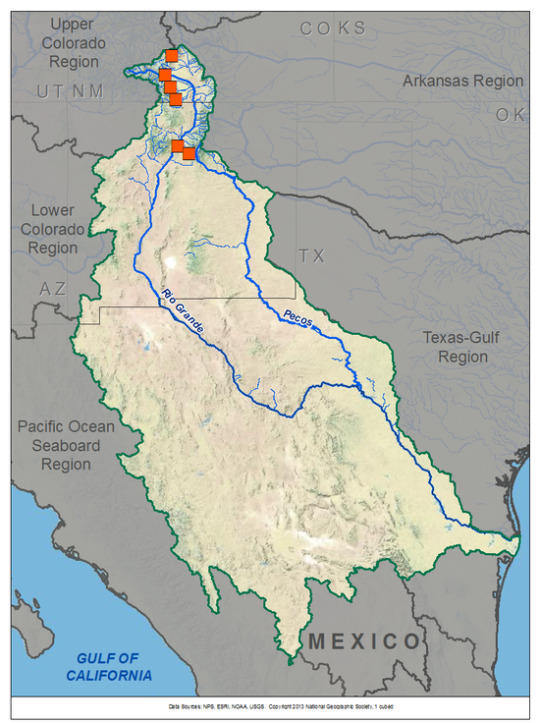

The Rio Grande and Colorado Rivers are two of the most threatened rivers in the U.S. National Geographic Photographer Pete McBride is on a mission to protect these vital rivers and their ecosystems.

— July 25, 2023 | Photographs By Pete McBride | By Kathleen Rellihan

National Geographic Photographer Pete McBride went on assignment to the Rio Grande to capture imagery of the depleted waterway.

Our nation's most vital waterways are drying up at an alarming rate due to global warming, increased human water use, and other man-made impacts. Nowhere is this crisis seen as dramatically than in the American West, with its longest drought in 1,200 years. Two of our nation’s critical lifelines—the Rio Grande and the Colorado River—are shrinking tragically with every passing day.

The Rio Grande is one of the most threatened waterways in the United States.

After spending years traveling the world on assignment, National Geographic Photographer Pete McBride realized that the world’s natural places he spent years documenting were changing drastically due to the disappearance of freshwater. He has spent the last two decades trying to bring awareness to this issue through photography and storytelling. Still, McBride calls for individuals and companies to take action to save our rivers and water.

“I hope to make people more aware of how fragile and precious our freshwater systems are—and why we all need to care for them like beloved family members. When we ask too much of them, they simply disappear.”

— Pete McBride, National Geographic Photographer and Explorer

Now, an effort from Finish Dishwashing is also helping to raise awareness of the crisis affecting freshwater resources everywhere. The Finish brand worked with a Texas sculptor to craft a one-of-a-kind sculpture that depicts the very thing it is honoring. Made from limestone that is native to Texas, the monument draws inspiration from rock formations, waterflow, waterfalls, flora, and fauna unique to many of the endangered bodies of water in the Southwest. Placed at the bottom of a lake in an at-risk area in Texas, the HOPEFUL MONUMENT is the first monument created with the hope that it will never be seen—that is, it will not be revealed unless water levels drop drastically low. While most monuments commemorate the past, this one is meant to spur action for the future—to inspire us to protect our most precious resource: water.

“Our drinking water doesn’t come from the tap, but rather rivers and lakes which supply the vast majority of all our water systems. Without them, then our taps will, and they already are, run dry and/or be polluted,” says McBride.

— Pete McBride, National Geographic Photographer and Water Advocate

McBride knows firsthand about the water crisis in the West, as he has documented it in his award-winning film, Chasing Water, and book, The Colorado River: Flowing Through Conflict. A photographer and Colorado native, McBride's mission is to raise awareness for the Colorado River and all American rivers, or arteries, as he refers to them.

After witnessing a dramatic loss of water in the Colorado River near his home, McBride expanded his photography career to be one that’s focused on environmental advocacy to protect the threatened resources of his home region, the American Southwest.

“I hope that combining beautiful imagery and a human story around a tough subject will help the public become more inspired to understand the issue and become more active,” says McBride, who was named a National Geographic Freshwater Hero for his work documenting rivers worldwide.

The National Geographic Photographer says he’s a “curious citizen who cares about his backyard river” and called to protect the waterway. And he’s now calling everyone else to do their part as well.

A Vital River Under Threat: The Rio Grande

On McBride’s latest assignment in Texas, he’s standing in a dried-up riverbed in the Rio Grande River, a spot locals tragically refer to as the “Rio Sand.” Just an hour south of El Paso, America’s fourth longest river is only ankle-deep in some locations. As it flows further south along the U.S./Mexico border, the river will become a trickle—and in many places—it runs completely dry.

The Rio Grande is dotted by dry stretches throughout Texas.

The Rio Grande supports more than 16 million people in the US and Mexico, including 22 indigenous nations. Alarmingly, this vital river system in North America is vanishing at a dramatic rate. Flowing from the Rocky Mountains and later forming the U.S.-Mexico border, this threatened river and its ecosystems have been impacted by agriculture withdrawals, rising temperatures, and unprecedented drought.

“The Rio Grande, just east of El Paso, is the ‘forgotten reach’—by the time it gets here it's a ghost of its former self. Because of a changing climate, severe drought, and asking too much of this limited resource, it's completely drying out.”

— Pete McBride, National Geographic Photographer and Explorer

The Rio Grande has seen devastating impacts from climate change. New Mexico, like much of the West, has been battling unusually hot and dry weather for the last two decades. The river has also been hit by historic drought, with the lower Rio Grande, the border between Texas and Mexico, dried up for over a hundred miles.

“Fresh water is one of the most important, limited natural resources,” says McBride as he stands in the barren riverbed. “We can live without oil; we can't live without water.”

America’s Most Endangered River—The Mighty Colorado

Seeing firsthand his own home dry-up in the water crisis had a major impact on the National Geographic Photographer: “I grew up on the [Colorado] River, so I always had a fond love for its beauty and wonder. When I followed it to its end and saw it run completely dry, I realized there needed to be more voices speaking on behalf of the river itself.”

The “lifeline of the West,” as the Colorado River is known, supplies drinking water to 40 million people in the U.S., fuels hydropower in eight states, and is a critical resource for 30 tribal nations and agricultural communities, according to the Bureau of Reclamation. It’s also the most at-risk river in the U.S. and is now considered the most endangered river in the world by conservation nonprofit American Rivers. The once mighty Colorado River has been drying out for the last twenty years due to overuse and historic drought.

Due to overallocation and climate change, the Colorado River has not reached the sea for two decades.

“The Colorado River is the frontline of climate change,” says McBride. “This remarkable river system supports over 5 million acres of farmland, where 95 percent of our winter vegetables come from. If you like eating salads, you are eating the Colorado River.”

As the climate crisis worsens, the water levels plummet. Today, the Colorado River runs at only 50% of its traditional flow, while its largest reservoirs in the United States: Lake Powell and Lake Meade, fell to 22% during the fall of 2022.

Everyday Actions to Save Water

The water crisis is a daunting and undeniably complex issue, but that doesn’t mean that people in their daily life can’t help protect our most valuable resource. If we don’t take action now, there won’t be time to save these rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and other bodies of water, warns McBride.

“Become more aware of your waterways. Our voices can make a difference. Rivers need more advocates,” advises the National Geographic Explorer, adding, “You can use less water by reducing meat consumption (meat requires a lot of water to produce), using less water-intensive, non-native thirsty plants in your yard, like bluegrass, and reducing how often you run your water systems for dishes, etc. We need agriculture as we need to eat; we just need to become more efficient and mindful about everything: from what is on our plate to how we clean them and use our taps."

McBride believes these are just some of the everyday actions we, as consumers, can take. Another small change that will make a ripple of impact? Use your dishwasher and stop pre-rinsing. Finish agrees. The brand has a longstanding history of driving impact and inspiring change through its ‘Skip the Rinse’ purpose campaign, which encourages consumers to skip pre-rinsing their dishes before placing them in the dishwasher, ultimately saving up to 20 gallons of water each time. If we all skipped the rinse, we could save up to 150 billion gallons of water every year.

Other water-saving actions include turning off the shower/faucet while lathering or brushing teeth and installing a greywater recycling system.

“Our fresh water is a limited resource,” warns McBride. “If we don’t get involved on some level, we will [see] more of that resource vanish.”

#Environment#Waterways Crisis#Rio Grande & Colorado Rivers#U.S. National Geographic Photographer Pete McBride#Kathleen Rellihan#American West#Hopeful Monument#Texas Native Limestone#Rock Formations | Waterflow | Waterfalls | Flora and Fauna#McBride: National Geographic Freshwater Hero#Rio Sand#El Paso#U.S. 🇺🇸/Mexico 🇲🇽 Border#Indigenous Nations#Rocky Mountains ⛰️#Agriculture 👨🌾#Hydropower#Tribal Nations | Agricultural Communities#Overuse of Waters | Historic Drought#United States 🇺🇸: Lake Powell | Lake Meade#National Geographic Explorer#Shower/Faucet#Greywater Recycling System#Resource Vanish

0 notes

Text

Shaaloani: The Land of Enchantment Part One

Hello again! It's another lore-adjacent post from me about a niche special interest of mine. This time it's Shaaloani, the American Southwest/Northern Mexico inspired zone in FFXIV's Dawntrail.

I want to disclose a few things right at the start just to temper people's expectations: I will not be definitively ID'ing any of the indigenous-inspired structures or visuals as inspired by any specific tribe. That's not my lane! I'm going to link to things that they remind me of, for sure. But otherwise my hyperfocus is going to be on the physical environment, some animals, and the ceruleum as petroleum industry. It's what I recognize best! And what I know best, truthfully.

"Hon why are you doing this?" A variety of reasons honestly. After DT dropped I saw a lot of folks who did at least one of the following:

Commented on the Old West theme park aspect

Called it "miqo'te Texas"

Generally just called the whole map "Texas"

And if I'm honest... it bugged me! Not because I thought anyone was being malicious about it (it's mostly pop culture saturation I'd suspect), but to me it stung a bit that this zone, which I grew up on the fringe of, was... kind of flattened by a lot of people?

I don't know, the response to me just felt like people assumed they knew everything about it because they'd seen it already in movies or TV or Red Dead Redemption rather than the same open-mindedness about what was presented in places like Urqopacha.

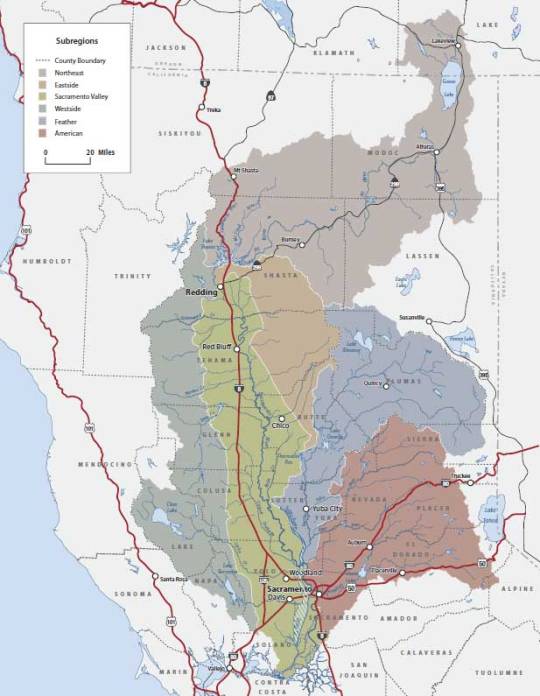

This zone isn't just Texas -- yes there are some bits and pieces here (because it's pulling from the Chihuahuan Desert and the Sonoran Desert), but so much of it reminds me of New Mexico, Mexico, and Arizona. There's some Colorado, Utah, and Nevada there too! And the background story going on there is something that still happens in a lot of those states, by both the government and corporations alike.

That variety deserves to be celebrated! So come learn with me about the inspiration for Shaaloani!

Shaaloani Geography

Shaaloani has three major regions in the zone -- Eshceyaani Wilds, Pyariyoanaan Plain, and Yawtanane Grasslands. To get this out of the way, I'm going to tell you the one that reminds me most of Texas.

Ready?

Lake Taori of the Pyariyoanaan Plain.

It's river-fed, with canyons on both ends of the Niikwerepi. The trees crowding around it are cypress trees, as you can tell by the little nubby off-shoots called knees. To compare, here is a photo of cypress trees along the Frio River:

This is also reminiscent of places along the Rio Grande and Pecos Rivers, two significant water sources in West Texas. I also would not call them bayous! Bayous typically have brackish water, are slow-moving, and are way too far east.

However, it could be partly considered a ciénega -- which according to its wikipedia article:

"Ciénagas are usually associated with seeps or springs, found in canyon headwaters or along margins of streams. Ciénagas often occur because the geomorphology forces water to the surface, over large areas, not merely through a single pool or channel."

As a caveat, ciénegas generally don't have trees around them, but I also know that you can't really drown a cypress and they love sunshine. Regardless -- if you see trees in the desert they are typically growing along a water source. Balmorhea State Park has some cottonwood trees native to the area that are going strong.

Yawtanane Grasslands reads as a mix of the Chihuahuan Desert and the Eastern Plains of Colorado. Both are rather arid and home to a variety of grasses that can thrive in such a climate -- which has historically made both areas home to large cattle industries (whether or not this was ever a good idea is debatable, since cattle are very thirsty animals).

Meanwhile the Eshceyaani Wilds looks similar to the Sonoran Desert -- the red-hued soil and rocks, the abundance of cacti with the scrub brush and some drought-tolerant grasses. Here's a shot of the Sonoran within Saguaro National Park in Arizona:

Saguaros also only grow in Arizona in the States! As well as the organ-pipe cactus, which you see in Tender Valley. And prickly pears grow just about anywhere they can get a chance -- as well as barrel cacti, both of which we see in Tender Valley (along with what could be agave!).

You could probably make a case for it being a piñon-juniper scrubland -- everything's very short compared to those cypress trees, including the juniper trees! Piñon-juniper scrubland's found throughout the Southwest. There are also piñon-juniper savannahs and persistent woodlands intermixed in the same places. The difference lay in what plants you find with the piñon pines and junipers.

Visually, aside from the Sonoran Desert, I can also see a lot of New Mexico, like the Ghost Ranch in Rio Arriba:

It matches up with the mountains you can see, and both Yowekwa Canyon and Tender Valley. And of course, Tender Valley is likely a Grand Canyon reference, going by the sheer height of the cliffs. But you could also make a case for Canyonlands National Park in Utah.

There's a shot from Grand View Point Overlook within the park -- the closeness of the canyon walls and the warm earth tones also evoke Tender Valley!

There's also a lot of these sandstone formations in Utah that better fit Shaaloani -- like here in the Valley of the Gods:

Shaaloani Structures

I also at this point want to call attention to one of the two sites with cliff dwellings & adobe structures. We just saw Tender Valley above, which is confirmed to be old Yok Huy structures. But check out these Tonawawta buildings below.

As I stated before, I don't want to state which tribe these two styles remind me of. But I do want to say this again strikes me as another New Mexico and Arizona callback; both the Gila Cliff Dwellings and the Puye Cliff Dwellings are found in two different areas of New Mexico. And the Gíusewa Pueblo, also in New Mexico! Montezuma Castle is found in Arizona, and is pictured below! Look at that rich reddish earth color.

I also want to call attention to the place of worship for the Tonawawta in Yowekwa Canyon:

When I saw it my kneejerk response was to call it an ofrenda. But that's ultimately an incomplete response -- that was just the vibe I felt after seeing them during my life! What it also reminds me of are pictographs and petroglyphs. You find these all over the Southwest (the climate helps preserve them!), but I'm going to link some really great examples. I won't provide images to all though!

Crow Canyon Petroglyphs:

Piedras Madras Canyon at Petroglyph National Monument (New Mexico) Petroglyph Point Trail at Mesa Verde National Park (Colorado) Petroglyph Panel at Canyon Reef National Park (Utah) Nampaweap at Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (Arizona) Horseshoe Canyon at Canyonlands National Park (Utah) and the Hueco Tanks State Park (Texas)

In contrast, I don't want to spend a ton of time on the boom town structures in this zone; they are pretty straightforward references to mining towns during the different resource booms (gold, silver, copper, oil).

Similar blocky shapes, built out of wood. One thing I noticed as a neat addition are the decorative patterns painted on it -- again, I don't want to presume if there's a specific tribe tied to this. But I do think it's a neat touch and I want to think that's a design choice to convey the underlying theme that this is a zone at odds with advancing technology and wanting to keep hold of important traditions.

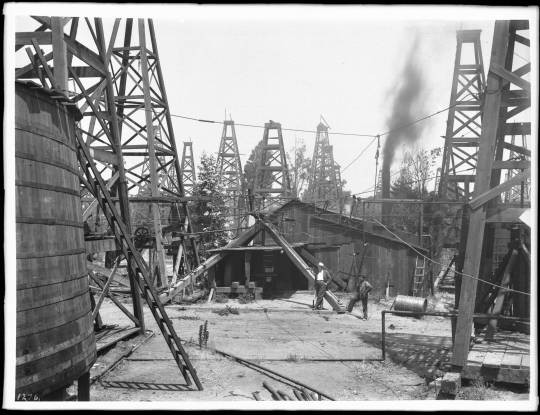

I WILL talk about the ceruleum wells and pumping though. Mostly because I'm impressed that they went with structures that so closely resemble early 20th century oil derricks. Those were also predominately made of wood (including the barrels, yikes!). The pump part of what's called a pumpjack were covered in the old days -- the ones we're most used to seeing now are made of metal and are thus left uncovered.

However, as you can see from this century old rig, even the wheel's made of wood:

I don't think ceruleum gushes the same way oil did -- it seems to behave more like natural gas. However, most natural gas pipelines do burn off excess, which can be seen as a little spout of flame atop.

Oil's occupied an awkward spot in the Southwest, and still does. Aside from the heinous crimes committed in Killers of the Flower Moon (where members of the Osage tribe were murdered for their oil shares in Oklahoma) and the Teapot Dome Scandal, oil is just... well.

Bear with me, I'm about to rag on Koana a moment.

The people who make the most money and have the most power over the average roughneck's life never live in the Southwest. They work in the c-suite and have more money than sense.

I find it very fascinating that DT chose to recreate this dynamic, this uncomfortable push-pull of a region rich in a resource, and it's being harvested at the suggestion and behest of a power that is physically removed from the area. And to some NPCs it's with a certain level of disregard to traditions and practices in place before, with the focus on the nebulous quantifier of 'progress'. Progress how? It depends!

But the folks at the highest seat of power never have to grapple with those questions, because to them it's a fairly cut and dry answer. This is the way to proceed, and if they want to take this nation into the "future", then this is the clear way to do it. It speaks to Koana's fixation on foreign technology to the point he de-values his own (partly due to his childhood trauma, which kind of prepped him to be susceptible to it).

Meanwhile the locals are the ones grappling the most with this change -- how it affects their plants and animals. Sometimes pits open up in the earth and ceruleum burns (which, Santa Rita New Mexico sank multiple times into the earth thanks to copper mining). On the map there's even discolored plants -- and they only occur in the vicinity OF the bulk of the ceruleum pumps.

This is at odds with core beliefs, keeping up with traditional practices. It puts people in the place of 'do I participate in this system, which promises work and the means to take care of my family, even as it pits me against my cultural heritage?'.

Growing up in West Texas, one of the weirdest things to me (to this day) is how many people will claim they love the land. They do! They love the outdoors, they worry over how certain species of animals have become scarcer. But they also work in the single most damaging industry because it pays the most money. It lets them cover bills and give their kids what they never had.

That same push-pull is in Shaaloani narratively; when progress has been thrust upon you, how do you survive it? How do you make sure what's dearest to you comes along with you?

In Conclusion

I want to call it here for Part One -- Part Two after this will cover more observations I had regarding flora and fauna in the Shaaloani zone, and how that also shows the attention to detail given this zone! It's a good time! There will be dinosaurs!

#FFXIV#ffxiv dawntrail#dawntrail spoilers#zone spoilers#shaaloani#ffxiv lore#lore speculation#long post

385 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, would you be willing to elaborate on that "disappearance of the Anasazi is bs" thing? I've heard something like that before but don't know much about it and would be interested to learn more. Or just like point me to a paper or yt video or something if you don't want to explain right now? Thanks!

I’m traveling to an archaeology conference right now, so this sounds like a great way to spend my airport time! @aurpiment you were wondering too—

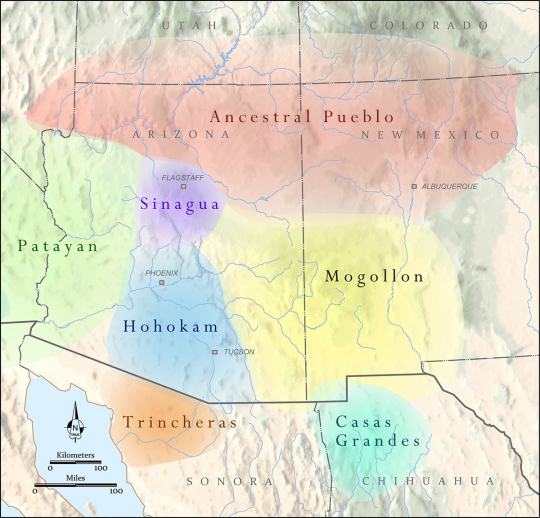

“Anasazi” is an archaeological name given to the ancestral Puebloan cultural group in the US Southwest. It’s a Diné (Navajo) term and Modern Pueblos don’t like it and find it othering, so current archaeological best practices is to call this cultural group Ancestral Puebloans. (This is politically complicated because the Diné and Apache nations and groups still prefer “Anasazi” because through cultural interaction, mixing, and migration they also have ancestry among those people and they object to their ancestry being linguistically excluded… demonyms! Politically fraught always!)

However. The difficulties of explaining how descendant communities want to call this group kind of immediately shows: there are descendant communities. The “Anasazi” are Ancestral Purbloans. They are the ancestors of the modern Pueblos.

The Ancestral Puebloans as a distinct cultural group defined by similar material culture aspects arose 1200-500 BCE, depending on what you consider core cultural traits, and we generally stop talking about “Ancestral Puebloan” around 1450 CE. These were a group of people who lived in northern Arizona and New Mexico, and southern Colorado and Utah—the “Four Corners” region. There were of course different Ancestral Pueblo groups, political organizations, and cultures over the centuries—Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Kayenta, Tusayan, Ancestral Hopi—but they generally share some traits like religious sodality worship in subterranean circular kivas, residence in square adobe roomblocks around central plazas, maize farming practices, and styles of coil-and-scrape constructed black-on-white and black-on-red pottery.

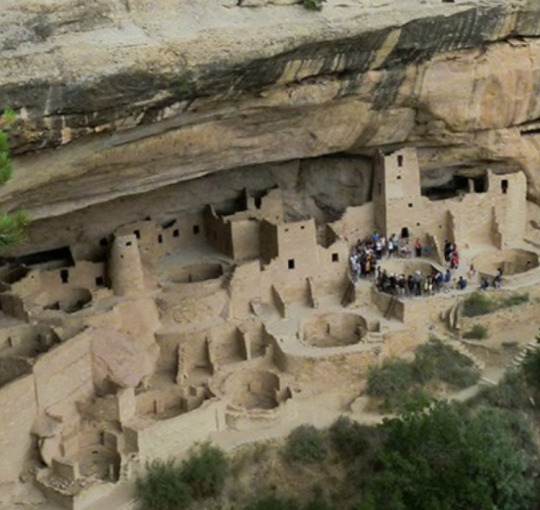

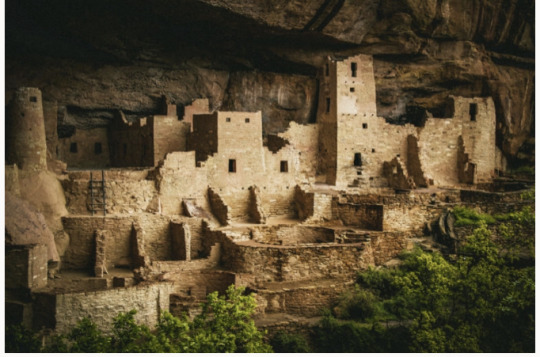

The most famous Ancestral Pueblo/“Anasazi” sites are the Cliff Palace and associated cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado:

When Europeans/Euro-Americans first found these majestic places, people had not been living in them for centuries. It was a big mystery to them—where did the people who built these cliff cities go? SURELY they were too complex and dramatic to have been built by the Native people who currently lived along the Rio Grande and cited these places as the homes of their ancestors!

So. Like so much else in American history: this mystery is like, 75% racism.

But WHY did the people of Mesa Verde all suddenly leave en masse in the late 1200s, depopulating the whole Mesa Verde region and moving south? That was a mystery. But now—between tree-ring climatological studies, extensive archaeology in this region, and actually listening to Pueblo people’s historical narratives—a lot of it is pretty well-understood. Anything archaeological is inherently, somewhat mysterious, because we have to make our best interpretations of often-scant remaining data, but it’s not some Big Mystery. There was a drought, and people moved south to settle along rivers.

There’s more to it than that—the 21-year drought from 1275-1296 went on unusually long, but it also came at a time when the attempted re-establishment of Chaco cultural organization at the confusingly-and-also-racist-assuption-ly-named Aztec Ruin in northern New Mexico was on the decline anyway, and the political situation of Mesa Verde caused instability and conflict with the extra drought pressures, and archaeologists still strenuously debate whether Athabaskans (ancestors of the Navajo and Apache) moved into the Four Corners region in this time or later, and whether that caused any push-out pressures…

But when I tell people I study Southwest archaeology, I still often hear, “Oh, isn’t it still a big mystery, what happened to the Anasazi? Didn’t they disappear?”

And the answer is. They didn’t disappear. Their descendants simply now live at Hopi, Zuni, Taos, Picuris, Acoma, Cochiti, Isleta, Jemez, Laguna, Nambé, Ohkay Owingeh, Pojoaque, Sandia, San Felipe, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Tamaya/Santa Ana, Kewa/Santo Domingo, Tesuque, Zia, and Ysleta del Sur. And/or married into Navajo and Apache groups. The Anasazi/Ancestral Puebloans didn’t disappear any more than you can say the Ancient Romans disappeared because the Coliseum is a ruin that’s not used anymore. And honestly, for the majority of archaeological mysteries about “disappearance,” this is the answer—the socio-political organization changed to something less obvious in the archaeological record, but the people didn’t disappear, they’re still there.

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

based on suggestions from the previous poll. Before asking about other bodies of water pls check if I've already included them <3

BEFORE YOU START ASKING ABOUT THE OCEANS. Reminder that this poll and the previous one are both offshoots of The Original Poll. Vote for your saltwater coasts there. Gulf of Mexico is included (my beloved)

There may be more polls bc I don't want anyone to feel left out! I'm from the southeast so obviously I have a skewed idea of what's major/popular/well-known. I'll probably keep pulling suggestions from the notes if I do any more polls

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fish of the Day

Today's fish of the day is the fathead minnow!

The fathead minnow, known also by the names: tuffy, fathead, and in the freshwater hobbyist industry a variant known as rosy red minnow. Scientific name Pimephales promelas, this fish is spread across North America, with a range stretching from the Southern borders of Canada, to the Northern borders of Mexico, stretching primarily along the great lakes and all connected rivers and streams down to the Rio Grande, and rivers in Chiwawa. This is their native region. However, outside of their native region they can be found introduced in the Atlantic and Pacific drainage areas, following rivers and creeks across the American South and the Colorado river. Invasive populations can also be found across Europe, where the fish has been listed as the main spreader of enteric redmouth disease, a bacterial infection that causes a hemorrhaging of mouth, fins, and eyes of salmonids.

Inside of the listed areas, the fish live in all variation of freshwater: rivers, creeks, and muddy pools of headwater.Known for their resilience for high turbidity, temperatures, pH, low oxygen, salinities, these fish thrive in environments other freshwater fish and minnows can not. They live in schools of fish near the bed, primarily due to their diet primarily being made up of scavenged algaes. Other than aquatic algae, the diet of the fathead minnow includes scavenged animal matter, primarily their fallen compatriots, crustaceans, detritus, zooplankton, and insect larvae. The fathead minnow is often predated on by larger predatory fish, but they contain a simple warning system that gives their schools a leg up. Communication in these fish is done almost exclusively in chemical signaling, from the release of alarm substances, to being used to identify familiar and unfamiliar fish to certain population schools, and use in breeding and courtship displays.

The alarm substance called Schreckstoff is believed to be secreted by all ostariophysan fish, one of the largest suborders of fish in the world, but research was first conducted on this substance in fathead minnows in the 1930's. Schreckstoff is a distinct club of cells on the epidermal that release when attacked. When schreckstoff is sensed in the water by other fish, it triggers anti predator behaviors, and recognition. Allowing for them to associate certain fish as predatory quicker in the future. Other than this, the fathead minnow can be used to indicate the toxicity of a certain aquatic environment. Due to their ability to live in such tough areas, they can be found in areas other fish can't be, like drainage sites. We can observe a lack in fertility and correct male development in areas containing certain oestrogens produced by humans, and certain plastics, allowing us an easy indicator to the toxicity of water sources.

The reproductive cycle of the fathead minnow is similar to other minnows. The spawning takes place from May-August, and the fathead minnows are polyamourus, picking different mates each season. They will produce anywhere from 1,000 to 12,000 offspring per season, and will create nesting sites close to the water surface in areas with horizontal surfaces. The placement of these nesting sites are intentionally placed in areas with low oxygen in the water, implying that this is an intentional choice made to avoid predation. The male will then chase away the female and watch over the fertilized eggs for the next 4-5 months until hatch. After this only a percentage of these fish will live past the fry stage, but if they can make it to a year of age, they can begin spawning themselves. Eventually, after a long and fruitful life of around 3 years, the fish will die of old age and slowing reflex.

That's the fathead minnow, everybody!

#fathead minnow#minnow#fish#fish of the day#fishblr#fishposting#aquatic biology#marine biology#freshwater#freshwater fish#animal facts#animal#animals#fishes#informative#education#aquatic#aquatic life#nature#river#ocean#Pimephales promelas

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

A crash course in some vocabulary

Archaeology, like all sciences, has a lot of specialized jargon we use to talk about pottery. To make sure everyone’s on the same page, here’s a list of some common terms I’ll be using, what they mean, and how to pronounce them.

~ 🏺🏺🏺 ~

Ware: A broader term for a technological/cultural tradition in pottery. Typically, construction method, color, clay type, temper type, and paint type are what defines a “ware.” So Chuska Gray Ware is unslipped, usually unpainted gray clay with crushed black basalt temper. Roosevelt Red Ware is red-slipped clay with sand temper and carbon-based paint. Hohokam Buff Ware is unslipped or cream-slipped buff-colored clay with coarse sand temper, created using a paddle-and-anvil forming method and painted with red paint.

Type: Within a ware, a type is a more narrowly specific decorative style. Roosevelt Red Ware has multiple types within it, such as Salado Red (unpainted red-slipped), Pinto Black-on-red (black paint on the red in a specific radially symmetric interlocked hatched-and-bold pattern), Pinto Polychrome (same decorative style but on a white-slipped interior field), Gila Polychrome (red exterior, white-slipped interior, a usually-broken black band around the rim, black painted designs in a two- or -four-fold symmetry), Tonto Polychrome (bolder and less symmetric black-and-white designs on a red field), Cliff Polychrome, Dinwiddie Polychrome, Nine Mile Polychrome… different stylistic variations on the Roosevelt Red Ware technological/visual core. You can read more about categorizations here.

A note on naming conventions: Pottery in this archaeological tradition tends to have a two-part name: a location where it was first defined and described, and a colorway. Wares tend to be “[Broad location or broad cultural group] [Color] Ware”; types tend to be “[Specific site] [paint color]-on-[clay color].” So within Tusayan White Ware is Flagstaff Black-on-white.

———

Gila: A river in southern Arizona and a bit of New Mexico, and a lizard and a polychrome type named after it. Pronounced hee-la.

Hohokam: An archaeological term for a Native American cultural group that lived in southern Arizona and northern Sonora, defined by traits like red-on-buff pottery, massive canal systems for field irrigation, and platform mounds. It comes from the O'odham-language word huhugham, “ancestors.” They are the ancestors of the modern Tohono O’odham and Akimel O’odham people (it’s a little bit more complicated than that but that’s basically the case.)

Mogollon: An archaeological term for a Native American cultural group from central New Mexico, eastern Arizona, and northern Chihuahua. Most iconic trait is the elaborate range of corrugated and smudged pottery. Named after the Mogollon Rim, the geological formation that marks the edge of the Colorado Plateau and a drastic change in geology and climate in the northern Southwest and the southern Southwest. Along with the Ancestral Pueblo, the Mogollon culture are ancestors of modern southern Rio Grande and Zuni pueblos. Pronounced moh-guh-yon.

Olla: A water jar with a wide body and narrow neck. Pronounced oy-ya.

Polychrome: Pottery that is three or more colors (poly+chrome), most often meaning red, white, and black.

A Tonto Polychrome olla. Southeastern Arizona, 1350-1450.

Pueblo: A collective term for Native people of the Southwest US (particularly in the Rio Grande river watershed, but also Hopi and Zuni) who share cultural traits and history—most immediately notably, a tradition of living in square adobe houses in large villages, which are also each called pueblos. Ancestral Pueblo is the term for the archaeologically-defined cultural group that share these similar traits and are, generally, from the northern half of New Mexico and Arizona, and a southern strip of Colorado and Utah. The Ancestral Puebloans were formerly called “Anasazi” but that has fallen out of favor due to pushback from modern Pueblos. Also, each modern Pueblo prefers to be called a Pueblo rather than a tribe in most cases—so you say the Pueblo of Acoma, the Pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh, Picuris Pueblo, Taos Pueblo, the Pueblo of Zuni, etc.

Temper: Non-clay bits that are added to natural clays to make them easier to work with. When you buy clay from a store now, it’s already mixed and processed and ready to use. When you find clay out in nature, it’s almost never so easy. Typically, you have to mine/harvest clay from riverbanks or cliffsides, and it’s hard and dried; then you have to grind the hard clay up into fine particles, and mix them with water. But natural clays are often puddly and don’t always hold together well, so you add temper, something hard and grainy to make your wet clay stick together more easily and make it good to work with! Temper can be sand, ground-up rock, ground-up shell, or even ground-up bits of other broken pottery. What different people used as temper is one defining feature of a pottery ware and pottery tradition.

Sherd: A broken bit of pottery. NOT shard. When it’s pottery, it’s “sherd.”

Slip: Very runny wet clay. It’s used to help attach clay pieces together, but more pertinently here, plain-colored pots are covered with an even layer of bolder-colored clay slip to get the desired color pot.

Smudging: A decorative style that potters made during the firing stage. They would have open pit-fires for firing their pottery, and cover the desired part of the pot with a layer of charcoal or ash. This creates a carbonized, reducing environment—that is, a lot of carbon, and little oxygen. This creates a smooth, inky black finish on the completed pot.

A Starkweather Smudged bowl. Mogollon, western New Mexico, AD 900-1200.

Vessel: Another word for pot, basically. Means a ceramic container of some sort. Bowls, jars, ladles, pitchers, mugs, etc are all vessels; effigies and statuettes are not.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

you can NOT be telling me those points are supposed to be the compound and the trailer.

the city we see when cpt sunshine is flying hank back to his house, so this is between wherever the Monarch lives in Malice and the Venture Compound. so there's a river nearby. looking at this map of colorado rivers, i can only assume its either the rio grande or the gunnison. idk why but i really thought it took place around springfield co which is in the most southeast of CO, and there's only two butte creek over there and it wouldnt make a lick of sense with the badly edited mapquest from ORB

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

D&RGW movie train westbound double-headed locomotives on a freight train pass movie set at hobo's shack "Limited Mail" Warner Brothers

Actors and crew watch a Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad locomotive pass the location shoot of the Warner Brother's film, "Limited Mail," in the Royal Gorge of the Arkansas River, Fremont County, Colorado. 1925

#d&rgw#rio grande#1925#trains#freight train#history#royal gorge#colorado#limited mail#warner bros#movie set

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BEGINNING OF THE BEGINNING

Who decides where a river starts? When are there enough sources, strong currents and water wide enough for its name? In Colorado, the Chama begins in smaller creeks and streams, flows into New Mexico to form the Rio Grande, splitting Texas and Mexico (who decided?) and moves deeper south. I think a few of these thoughts by a creek on a beaming hot day, as water rips by in rapids propelled, formed in mountains far above. The water icy even in this summer heat. People grin some false bravery. They sit in tubes and dip into the tide and be carried away. I think of drowning. Of who sees water as fun. Who gets to play in a heatwave. Who trusts the flow. Migrants floating in the Rio Grande haunt me, so I think of families tired of waiting, of mercy that never comes, of taking back Destiny. The rivers must have claimed more this year. Knows no metering but the rush of its mountain source’s melt. A toddling child follows her father into water’s pull. Think of gang’s demands, of where those come from. Trickles of needs meeting form a flow of migrants. Think of where it begins. Think of the current of history—long, windy, but traceable and forceful in its early shapes.

PHUONG T. VUONG

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also been falling deep into my Country and State humans aus that I wanted to share something that I decided to recreate. Im just doing this to pass by time since im on CQ duty... Im most certainly aware that nobody is gonna wanna read any of this, but its too late. Im writing it anyways.

This is my old design of Texas. I have redisigned her so she has a past and current design.

This is her past design. Back when she was Mexico's daughter. But after the Texas Revolution and she disowns herself, she tries to be her own country but fails before even a decade ends. She turns to America and asks to be annexed as a state. America agrees after 9 years. Down below is her modern design.

When Texas first joined, she was the biggest, loudest, and most problematic state. Not many states liked her, her only friends being Florida, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Not even America grows to like Texas much. She's too independent and braggy for his liking (which is funny because that's how he acts exactly). So she tries to "fit in" by changing her hair and main colors to red, white, and blue.

Not long after, her and her biological father had an argument over where the Texas-Mexican border should be. Texas said the Rio Grande River, whilst Mexico said it should be the Nueces River. Mexico also didn't recognize their daughter's independence, ultimately causing the Mexican-American war in 1846- 1848. This caused Mexico to cedced Upper California and New Mexico, who are Texas' brothers.

Then, in 1850, Texas signed the Compromise of 1850, where she gave up some of her territory to New Mexico, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Kansas. She hated this, ultimately growing to hate New Mexico and Oklahoma.

A little over two decades go by and South Carolina has seceded from the union, and soon the other southern states followed. Texas was easily persuaded to join the Confederacy, but didn't do much to to help in the main war front. At the end of the war, Texas was let off lightly alongside Florida.

I'll skip over WW2 because she clearly would support her adoptive father's decisions. But WW1, oof- Learning that Germany tried to get Mexico to attack America by attacking her... she was a bit scared. She was relieved when Mexico didn't agree to join Germany.

Now after the Cold War, Texas began to see an issue at the Texas-Mexican border. Immigration. Immigrants in large numbers would file into Texas due to reasons her father isnt proud of to this day. She tried to deal with the situation herself but America budded in and now we have the wall and deportation and everything else going on today. This is causing her to be depressed since she can't openly talk to her biological father freely anymore but she doesnt want to upset America.

Also just to add, in my au, Texas will secede from the USA. She was reading through her old documents and found her state constitution. She forgot that she could still secede if she wanted to, and does.

BTW: Also it's Texas x Tennessee... Sooooo...... Yeah. Thats that I guess.... Peace ✌️

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

All roads lead to Phoenix. On the gravy train of greenfield investment riding on the back of Inflation Reduction Act legislative incentives in the United States, no county ranks higher than Arizona’s Maricopa. The county leads the nation in foreign direct investment, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. (TSMC), Intel, LG Energy, and others expanding their footprint in the Grand Canyon State. But Phoenix is neither the next Rome nor the next Detroit. The reasons boil down to workers and water.

First, the labor. America’s skilled worker shortage has been well documented since before the Trump-era immigration slump and pandemic border closures. Especially in the tech industry—the United States’ most productive, high-wage, and globally dominant sector—a huge deficit in homegrown engineering talent and endlessly bungled immigration policies have left Big Tech with no choice but to outsource more jobs abroad.

Arizona dangled its low taxes and sunshine, but TSMC has had to fly in Taiwanese technicians to jump-start production at the 4 nanometer chip plant that was meant to be completed by 2024, but has been delayed until 2025 at the earliest.

The salvage operation calls into question whether the more advanced and miniaturized 3 nanometer plant—scheduled to open in 2026 will stay on course. (With two-thirds of its customer base—including Apple, AMD, Qualcomm, Broadcom, Nvidia, Marvell, Analog Devices, and Intel—in the United States, it’s no wonder TSMC wants to speed things up.)

From electric vehicles to gaming consoles, the forecasted demand for the company’s industry-leading chips is projected to rise long into the future—and its market share is already north of 50 percent. Given the geopolitical risks it faces in Asia, a well-trained U.S. workforce could give it the comfort to establish the United States as a quasi-second headquarters. After all, Morris Chang, the company’s founder, had a long first career with Texas Instruments.

But the next slowdown they may face is Arizona’s dwindling water supply. In just the past year, Scottsdale cut off water to Rio Verde Foothills, an upscale unincorporated suburb on its fringes, due to the region’s ongoing megadrought and its curtailed allocation of Colorado River water. This was followed by Phoenix freezing new construction permits for homes that rely on groundwater.

Forced to find other sources, industry players have stepped up buying water rights from farmers, essentially bribing them to stop growing food that would serve the region’s fast-growing population. Then there are the backroom deals involved in an Israeli company receiving the green light for a $5.5 billion project to desalinate water from Mexico’s Sea of Cortez and pipe it 200 miles uphill through deserts and natural preserves to Phoenix.

Water risk brings political risk for companies. Especially in Europe, governments are carefully weighing the short-term benefits of corporate investment versus the climate stress it exacerbates. They have good reason to be suspicious: Firms such as Microsoft have been notoriously inconsistent in reporting their water consumption, and promises to replenish consumed water haven’t been delivered on. And even if data centers are becoming more efficient, growing demand just means more of them. Some European provinces have blocked data center development, pushing them to locations with high heat risk.

Europe’s regulatory stringency has long been off-putting to foreign investors, which is what makes European officials so weary of Washington’s aggressive Inflation Reduction Act, CHIPS and Science Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

But to fulfill its promise of putting the United States on a path toward sustainable industrial self-sufficiency, these policies need to better align investment with resources, matching companies to geographies that best suit their needs. It would be better to direct capital allocation to climate resilient regions than to throw good money after potentially stranded assets.

If any company ought to know better on all these matters, it’s TSMC. In Taiwan itself, the industry’s huge energy and water consumption are a source of controversy and difficulty. Not only have droughts on the island occasionally slowed production, but the company’s own water consumption rose 70 percent from 2015-19.

Furthermore, Taiwan knows that its real special sauce is precisely the technically skilled workforce that the United States lacks. Yet TSMC has doubled down on Phoenix, a place without a reliable long-term water supply for industry, little in the way of renewable energy, and a construction freeze that will make it challenging to house all the workers it needs to import.

With all the uncertainty over both water and workers, this begs the question of whether the semiconductor company the entire world is courting would have been better off establishing its U.S. beachhead in the upper Midwest or northeast instead? Ohio, upstate New York, and Michigan rank high in greenfield corporate investments, resilience to climate shocks, and are abundant in quality universities and technical institutes.

Amid accelerating climate change and an intensifying war for global talent, how can those devising U.S. industrial policy better select the appropriate locations to steer investment to?

States with higher climate resilience than Arizona are starting to flex for greater investment. According to recent data, Illinois has climbed to second place nationally for corporate expansion and relocation projects. The greater Chicago area and state as a whole are touting their tax benefits, underpriced real estate, growth potential, and grants to prepare businesses to cope with climate change.

Other parts of the Great Lakes region, such as Michigan and Ohio, are also regaining confidence in their industrial revival, pitching heavily for both domestic and foreign commercial investment while emphasizing their affordability and climate adaptation plans.

Just over the border, Canada has been wildly successful in poaching foreign skilled workers unable to secure or maintain green card status in the United States while also investing heavily in economic diversification—all with the benefit of nearly unlimited natural resources and energy supplies. While Canada hasn’t yet rolled out Inflation Reduction Act-style tax breaks to lure investors, it abounds in critical minerals for EV batteries (nickel, cobalt, lithium and rare earths such as neodymium, praseodymium, and niobium) as well as hydropower.

The more that climate change warps the United States, the more grateful it should be that its most natural and staunch ally occupies the most climate resilient real estate on the North American continent, even taking into account the raging wildfires of this summer. But rather than covet Canada the way China does Russia—as a vast and depopulated resource bounty—the United States and Canada should cooperate far more proactively on a continental scale industrial policy that would bring about true self-sufficiency from the Arctic to the Caribbean.

This is where geopolitical interests, economic competition, and climate adaptation converge. As Canada’s population surges by up to 1 million new permanent migrants annually, a more unified North American system would be more self-sufficient in crucial commodities and industries, less vulnerable to supply chain disruptions abroad, and avoid unnecessary carbon emissions from excessive inter-continental trade. Thirty years after the NAFTA agreement, it seems more sensible than ever to graduate toward a more formal, autarkic North American Union.

One can easily imagine Greenland joining one day—the country already enjoys autonomy from its colonizer (Denmark) and is now pushing for complete independence, driven partly by the desire to control more of the riches that climate change has revealed it to possess.

Meanwhile, in Taipei, there are far more complex geopolitical consequences to consider. TSMC has long been considered Taiwan’s “silicon shield,” a leader of industry so important that a conflict that took it offline would be a major own-goal for China. But it is precisely the combination of the China threat, environmental stress, and pandemic-era supply chain disruptions that convinced TSMC’s customers that its home nation represents too large a concentration risk.

Now TSMC and its rivals are expanding production from Japan to the United States, Europe, and India. This globally diversified set of chip manufacturers is easier for China to exploit as countries more susceptible to Chinese pressure become less rigid in compliance with U.S.-led export controls over advanced technologies.

At the same time, if the United States no longer depends on Taiwan itself for the majority of its semiconductor supply in just five to seven years, will it be as willing to defend Taiwan militarily? This, not Ukraine, is what Beijing is watching for as it pursues its own “Made in China” quest for self-sufficiency.

Industrial policy is back in vogue as a national security and economic strategy. But to get it right requires aligning investment into industry and infrastructure with the geographies of resources and resilience. The countries that build climate adaptation into their strategies will be the ones that build back better.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

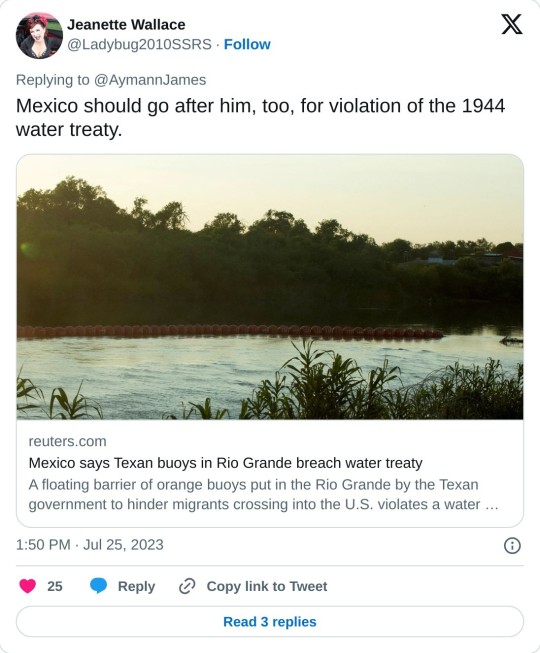

MEXICO CITY, July 14 (Reuters) - A floating barrier of orange buoys put in the Rio Grande by the Texan government to hinder migrants crossing into the U.S. violates a water treaty and may encroach on Mexican territory, incoming Mexican Foreign Minister Alicia Barcena said on Friday.

"We have sent a diplomatic letter (to the U.S.) on 26 June because in reality what it is violating is the water treaty of 1944," Barcena told reporters in Mexico City, referring to the Mexican Water Treaty between the U.S. and Mexico that covers the use of water from the Colorado, Tijuana and Rio Grande rivers.

"We are sending a mission, a territorial inspection," Barcena added, "to see where the buoys are located... to carry out this topographical survey to verify that they do not cross into Mexican territory."

The U.S. State Department and the office of Texas Governor Greg Abbott did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Barcena was named foreign minister last month but is still awaiting formal confirmation by Mexico's Senate.

On Friday, the Texan government said in a statement that it had this week begun installing the "new floating marine barriers along the Rio Grande River in Eagle Pass."

It said the buoys will "help deter illegal immigrants attempting to make the dangerous river crossing into Texas."

Many migrants have drowned trying to cross the river in recent years but some experts fear the buoys may only increase the risk of crossing.

Earlier this month, four migrants drowned in the Rio Grande. Last September nine migrants died and 37 were rescued as they tried to cross the rain-swollen river near Eagle Pass.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Gawd! There Was Out-Bespoken Garb Galore at the Glitzy Gala

Finally, the rich are going to get a fair shake in this country. Hail, lord of hosts! From somewhere near the Gulf of America, wishing you a nice day. Yours in freezing… PS: There are some rivers in Texas that could do with good English names, starting with the Rio Grande, the Colorado, the Brazos, the Guadalupe, the San Antonio, the Navidad, the Lavaca, the Pedernales, the San Marcos, the…

0 notes