#Revolt on Antares

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

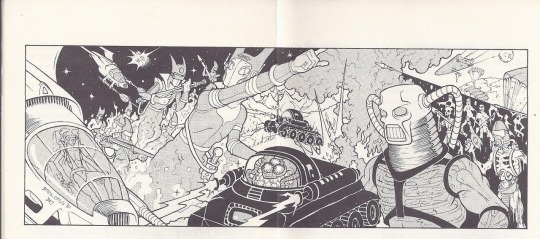

TSR's Mini Games were their answer to the microgame movement, pocket-sized board games with folded paper maps and a small sheet of counters (ad from back cover of White Dwarf 30, GW, April/May 1982)

#D&D#Dungeons & Dragons#TSR#Mini Games#minigame#AD&D#board game#Revolt on Antares#SAGA#Vampyre#They've Invaded Pleasantville#dnd#microgame

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

My relationship with victoria dallon is super weird. I really like her on paper, i like the concept of what antares is meant to be, i have consistently liked the victoria ive seen in fan fics, i love the victoria of fanarts and i love the victoria cosplays and i especially love the victoria that exists in everyones head

I find victoria as depicted in ward proper revolting.

Such is my dillema.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

SL1:“Gorlans ruiner”.

Originaltitel: Ruins of Gorlan. Serie: Spejarens Lärling #1 (Ranger's Apprentice #1). Författare: John Flanagan. Översättare: Ingmar Wennerberg. Publicerad: 2004 (på svenska 2013). Medium: eBok/B. Wahlströms.

Läses tillsammans med @kulturdasset i vår läsecirkel.

¡Oi! Spoilers, stavfel och alternativa fakta kan förekomma rakt föröver!

Delmål 1 (Prolog + Kapitel 01–04).

En bok som har en relativ mjukstart men lyckas på ett par kapitel sätta upp brädet med dess nyckelfigurer. I prologen får vi möta det jag antar kommer vara bokens (om inte seriens) stora skurkroll: Morgarath. Vi får det bekräftat i första kapitlet när vi får möta baronen han vill störta som är godhjärtad och ger föräldralösa barn en chans att få kontroll över sitt liv. Efter ett tidigare försök till revolt har Morgarath tagit sin tillflykt till bergen där han tränas sina styrkor och bidar sin tid. Prologen väcker viss nyfikenhet.

Samtidigt får vi möta Will. Will utan namn, ingen vet vilka hans föräldrar är mer än meddelandet att hans far dog som en hjälte. Han har diktat ihop en egen historia om vem hans far är, och planerar nu gå i skuggestaltens fotspår och bli krigare. Trots att han är för kort och tanig för jobbet. Samtidigt får vi en hint om den talang som skall ge honom ett lärlingskap: han är skicklig att klättra och ta sig in i slottet för att ställa till bus.

Hans mor dog i barnsäng. Hans far dog som en hjälte. Ta hand om honom. Han heter Will. (Flanagan, 2004/2013)

Det är minst sagt ett udda möte med Will och hans vänner, där den starke krigaraspiranten Horace ständigt retar Will för dennes tanighet. Och givetvis alla vännerna uppvisar de drag som är instrumentala för deras yrkesval. Spejaren Halt har antagligen hört talas om Will, det skulle inte förvåna mig om han gått till det här mötet bara för att ta sig en titt på honom. Halt har iaf ett pergament med sig som berör Will, något Baron Arald bör veta, och med all säkerhet handlar det om Wills bakgrund. Will verkar vara den enda som får lämna mötet utan ett lärlingskap, som om vi inte redan vet vem som kommer ta Will under sina vingar. Förhoppningsvis får vi reda på mer i kommande delmål om vad som står i dokumentet och vad man nu vet om Will – något säger mig att vi kommer få veta vem hans far är så småningom och att det kommer avslöjas med en tung mörk sanning.

Redan här så märker man att den här boken är skriven för en yngre publik än de vi främst läst hittills i läsecirkeln. Intrigen känns kondenserad och scenerna målas upp med snabba penseldrag. Men utan att det gör boken oläslig för en äldre publik.

Delmål 2 (Kapitel 05–09).

Redan när kapitel 5 inleds, slås jag av tanken: givetvis är det ett test. I samma stund som det står klart att Will inte kan släppa pergamentet och dess innehåll inser jag: det är ett test för att se om och hur han väljer att försöka läsa det.

Samtidigt kunde han inte låta bli att tänka på spejarens pergament. Han undrade vad som stod på det. När skuggorna på fälten blev längre hade Will fattat ett beslut. Han måste läsa vad som stod på det där pergamentet. (Flanagan, 2004/2013)

Och visst slår ”fällan” igen runt Will i samma stund som han nästan har dokumentet i sin hand. Halt är där i mörkret och väntar. Så klart, de dolda agendorna i den här boken kommer inte vara dolda av Illuminati. Och av texten på pergamentet att döma så har Halt haft ögonen på Will ett tag. (det bekräftas senare i delmålet med, Halt har haft ögonen på Will i flera år).

Eftersom alternativet är att bli bonde tackar Will ja, och accepterar att krigarskolan antagligen aldrig kommer vara inom räckhåll. Och när vi får läsa om Wills sorti från slottet när han skall flytta till Halts stuga så funderar jag lite om det var en del av rekryteringen att Will skulle lämna slottet obemärkt och utan att någon egentligen visste att han blivit rekryterad?

Delmålets sista kapitel sticker ut med att vi plötsligt får följa Horace och hans första tid på krigarskolan, hur hans romantiska bild av den smulas sönder under trycket av hård disciplin, ännu hårdare träning och pennalismen som verkar vara en del av all militär träning. Mot slutet av kapitlet påminns jag av filmen ”Full Metal Jacket”.

Att de äldre rekryterna går så hårt åt på Horace kommer med all säkerhet ha inverkan på dennes sinnesstämning och utveckling. Och jag är lite nyfiken på hur detta kommer påverka Horace och Will när deras vägar korsas igen. Horace verkar också rätt förtjust i ”Jenny” som vi fick träffa tidigare och blev rekryterad till köket. Än finns kanske inte så mycket som tyder på att Jenny skulle ha intresse i Will (när Will satt i trädet var det Allys som tittade ut genom dörren) men lite undrar jag om det här är grunden till en kommande liten triangelintrig?

Delmål 3 (Kapitel 10–14).

Horace visar sig vara en ren naturbegåvning med ett svärd och imponerar stort på Sir Rodney. Att vi fortfarande dröjer vid honom måste innebära att karaktären kommer bli viktig på något sätt. Har svårt att tro att det enda målet med karaktären är att visa ”vilken tur” Will hade som inte platsade på krigarskolan. Ellerockså är det för att bidraga med något intressant till handlingen under Wills träningssessioner, som ärligt inte tillhör bokens intressantaste delar.

Jag undrar bara kring det där om att be hästen om lov? I en tid/miljö där hästen är det befästa transportmedlet så borde väl ändå vara viktigt för alla hästar? Lite lockas man att fundera kring varför den här detaljen framhålls som specifik för just spejarna.

Jag måste erkänna att jag rullade lite med ögonen över det där med ”funktionell manlig prägel”. Varför måste saker som ”personlig prägel” eller ”affektionsvärde” vara något som endast förbehålls kvinnor. Sir Rodney har med andra ord inte en pryl kvar efter sin fru? En säng och ett skåp för rustningen tillsammans med skrivbordet? Är det manligt funktionellt att sitta ned? 😋

Medan Rodneys hustru Antoinette fortfarande levde hade det varit lite mer utsmyckat, men hon hade dött några år tidigare. Nu fanns det inga prydnadsföremål alls i rummet. Det hade en funktionell, manlig prägel. (Flanagan, 2004/2013)

Och det visar sig att krigarskolan inte alls gillar när äldre rekryter trakasserar och mobbar de nya. Boken är ju riktad till en yngre publik, så att det är två element som lyfts som olämpliga är kanske igen förvåning. Dock så är det trevligt att Flanagan inte glorifierar den militära banan som om det inte förekommer – för mobbing, trakasserier och ren pennalism har ju alltid tillhört olämpligt beteende.

Inte det intressantaste av delmålen hittills, men storyn rör på sig iaf. Framöver hoppas jag att vi kommer titta in hos tjejerna med. Något säger mig att även om Will är centerfiguren så kommer han, Horace, Allys och Jenny på något vis bilda ett team framöver. Jag tror iaf inte att det här en tillfällighet att deras lärlingskap passar så väl ihop (Jenny lär vara den som hör mest av slottsskvallret t.ex.).

Delmål 4 (Kapitel 15–19).

Will får träffa sina vänner igen, och det blir ett inte helt glatt möte då Horace kommer på kant med gänget och tar ut sina frustrationer på, främst, Will. Lite förvånande, men inledningsvis i boken visar ju Horace en tendens att vilja reta Will för dennes tillkortakommanden och gör så också här genom att omnämna Will som ”den blivande spionen”. Det här punkterar min teori om att Wills rekryterings delvis skulle vara medvetet dolt.

Det vankas vildsvinsjakt efter att Halt och Will fått spår på ett stort sådant, och jag trodde att något skulle hända mellan Horace och Will när den förre blev utvald att få följa med på jakten. Nåväl – de har hela nästa delmål att ryka ihop på. 😋

Tyckte man att det var en twist när det blev fullt slagsmål mellan Will och Horace under skördefesten so kommer en till i slutet av det här delmålet: Horace tittar på Will utan fientlighet. Har han kanske kommit till sans och insett att det var han själv som klampade in med spikskorna på?

Delmål 5 (Kapitel 20–24).

Ett händelserikt delmål som både verkar sätta punk för pojkarnas fejd och även ta itu med Horace problem. Min teori om att Horace och Will (tillsammans med flickorna) på något vis kommer bilda ett informellt team är sålunda på rätt köl igen. Jag gillar f.ö. att det är Halt som kliver in och bringar reda i oredan, även om den rena hämnd-misshandeln som tillåts Horace mot sina tre plågoandar kanske inte är delmålets starkaste delar. Det skall bli intressant om vi kommer stöta på Alda, Bryn och Jerome igen i kommande delar.

Delmålet knyts ihop med att Will slutligen känner sig hemma hos spejarna, och inser att han nu ingår i en exklusiv liten skara lojala mot varandra. Och trekvart in i boken så var det dags att Morgarath började röra på sig. Som det ser ut så kommer kriget möjligen bara hinna bryta ut denna bok. Kanske i samband med att man kommer nu att leta upp kalkaranerna. Ytterligare ett monster som beskrivs som en blanding mellan apa och björn. Av någon anledning kommer jag att tänka på Trollockerna i SoDÅ/tWoT.

Delmål 6 (Kapitel 25–29).

Ett småspännande delmål där saker och ting börjar röra på sig, framför allt så inser spejarna att Morgarath har börjar ansamla styrkorna och söka nya allierade. Will ges en väldigt aktiv roll utan att han utsätts för onödiga eller orealistiska risker – han får hämta förstärkningar hos baronen. Han vågar sig också på att lufta sina rädslor för baronen: att Morgarath kanske jagar ett betydligt personligare byte än kungen. Baronen är inte främmande för att Halt kan vara en måltavla.

Jag kan uppskatta att det aldrig blir internt mellan Halt och Gilan, och att en viss vänskap uppstår mellan Will och Gilan. Jag gillar också att sir Rodney skäller ut vakten efter noter när denne avfärdar Will som obetydlig trots att han helt uppenbart borde kännas igen som en spejare. Trots att han bara befinner sig i bakgrunden är det en karaktär som jag gillar mer och mer för var gång han dyker upp.

Trots att karlakanerna skall vara ökänt svåra att döda så gör baronen och sir Rodney processen kort med den. Kanske hade de turen och överraskningsmomentet på sin sida i kombination med att Halt ”mjukat upp” den lite inför deras ankomst.

Truppen lär sätta efter det ylande ljudet nu, och förhoppningsvis komma i tid för att Halt och Gilan inte skall hamna i allt för stora svårigheter.s

Delmål 7 (Kapitel 30–32 + Epilog).

Sista delmålet, knyter som väntat ihop säcken, inklusive en liten kärleksscen med Allys. Med Will som den store hjälten efter att ha dödat den sista Karlakanen med en eldfängd pil. Alla hans drömmar ser ut att gå i uppfyllelse när Baronen och sir Rodney omvärderar Will och ger honom en chans att studera vid krigsskolan. Horace är den som hurrar högst och längst, men som väntat säger Will nej. Vilket följer Wills karaktärsutveckling de senaste delmålen: han har trots allt hittat hem. Och trots att det kanske känns lite ”over-the-top” att Halt inte bara visste vem Wills far var utan även räddades av honom så blir det ett fint slut i epilogen när Will äntligen får reda på vem hans far var. Och med vetskapen att hans far inte var en storslagen riddare utan bara en sergeant med ett gigantiskt jävlar anamma blir han till syvende och sist ändå tillfreds med sina beslut och var han hamnade i livet.

Sammanfattning.

Bra skriven och en story som håller måttet även när man är lätt utanför målgruppen. Will är en trevlig prick, lätt att tycka om och han uppvisar både mod när det gäller och osäkerhet inför vart livet fört honom medan han långsamt hittar ett hem hos spejarna. Jag är inte förvånad över att boken slutar innan kriget bryter ihop helt, utan mer rundar av efter den här första prövningen. Will får inte många kapitel ihop med de gamla vännerna, men mycket tyder på att de kommer behålla kontakten böckerna – så min vision om att de tillsammans kommer bli lite av ett team är inte helt omöjligt. Jag är också glad att min teori om att Morgarath skulle vara Wills pappa visade sig vara en obefogad oro. På det hela taget en trevlig läsning och jag ser fram emot att få se vart fötterna bär Will härnäst.

Länkar.

Boken @ Goodreads.

eBibliotek @ Axiell Media.

Biblio @ Axiell Media.

#läsning#bokcirkel#läsecirkel#böcker#john flanagan#gorlans ruiner#ruins of gorlan#spejarens lärling#ranger's apprentice#fantasy#elib#biblio#2004#us#2013#se

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Completely randomly, I was thinking about Nora’s character and started wondering what her abilities were. Because everyone seemed to have a distinct ability on top of telekinesis (healing, empathy, fire, etc.) but she isn’t really shown using any. Than I started thinking about how she was referred to as ‘The Engineer’ and how they could hint towards her abilities. Going back to OG Roswell (sorry I do this every time) their abilities were reconstructing and manipulating molecular structures. And I guess I am wondering if her abilities could somehow connect to what Michael said about their technology being on some level biological. Like if technology is just technology unless you have the power to make it something more. Which could explain how the Lockhart machine was amplified by the turquoise.

Then I started thinking about why Michael would be considered the heir to the dictator, as Isobel and Max both would have seemingly equal claims. And I started wondering if maybe Nora was part of the original ruling family, one that imprisoned Jones and Louise to use their abilities. Which would make Jones why they locked him up bit checkout, because he was the savior at some point? Maybe he eventually broke free and took control, Nora creating an underground revolt and somehow having a political marriage to him? Giving Michael the rights to claim the throne from multiple angles, kicking Isobel and Max down the line. (This is assuming their planet works on a monarchy system, since Antar did in the OG Roswell show)

#roswell new mexico#nora truman#Lockhart machine#deep sky#rnm s3 spoilers#head cannons#michael guerin#mr jones

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't think that they will remove Aurora old story...unless they want start a revolt or something like that

-------------------

True, it'd be a horrible move on Lovestruck's part. I think it'll just be like Antares and Nova, so Aurora and Chance(?) will have a route both with the old MC and the new MC. - Mod Jessa

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Love this Erol Otus piece. Evidently from Revolt On Antares, a science fiction-themed microgame by Tom Moldvay from TSR in 1981.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taglist

Ok so i was an idiot and deleted the taglist i had saved but i did manage to restore some of the names so if you're not on the list then please just comment that you want to be added but please specify which taglist you want to be in whether it be on my permanent taglist meaning you will get tagged on ALL fics i post or just on the Adrestia, Goddess Of revolt fic. Ok thank you

Permanent tag list

@gwenebear @celestiaelisia @blondieee-me @harrisongslimited @wittysunflower @introvertedmegalomaniac @derangedcupcake @wholelottatiffy

Adrestia Goddess of revolt taglist

@go-to-the-window-blog-blog @letoursilencebreaktonight @babygirltaina @beyond-antares @notyouraveragemochii @baphometwolf666

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revolt On Antares Review

https://centurionsreview.com/revolt-on-antares/revolt-on-antares-review/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kalems and Lucifers Relationship is rather Complicated, to say the least.

Much like Antares, Kalem used to be very close to Lucifer. They shared complete trust with each other, let themselves depend on the other, took care of each other. That time is fondly remembered by them. Even now, they do care about the other. Noone else may come as close to them as Lucifer, Aedrial and Kalem were.

Though that pure devotion to each other is heavily tainted by the angelic revolt under Lucifers lead.

Unlike Aedrial, who decided to only ever follow Lucifer, Kalem decided to stand on the other side. To Lucifer it was the most hurtful feeling to see someone who knew him better than anyone to oppose his ideals. Questioning his desicions. While to Kalem... he ended up paying for standing in Lucifers way with scars that will never fade. Seeing Lucifers betrayal not only against heaven, but also against their close bond.

They both regret the happenings back then. While Kalem still believes he had done right to oppose Lucifers violent way of changing heaven, he regrets not being able to talk sense into Lucifer. Not pushing harder on the matter. For Lucifer... after his rage died down, long after his banishment, he started to feel deep regret of hurting Kalem. He knows he had betrayed Kalem even on a personal level, and does not ever expect forgiveness.

0 notes

Video

(via he Mystic Tragedies Of Theodhatres: Antares - The Antagoni… | Flickr)

The Mystic Tragedies Of Theodhatres:

Antares - The Antagonism Of The Impossible by Daniel Arrhakis (2020)

Two young women Anthea and Thalia fall in love in spite of the moral values that reign in their families.

Despite being very different, they have something in common, the pleasure of observing the night sky and especially their favorite star Antares, the red star in the Constellation of Scorpio.

But there is something else that unites them, the non-conformity of their destinies and the impossibility of their dreams. However, one day the relationship is discovered and they are prohibited from seeing each other.

Disconcerted, they devise a plan to flee the two of them and on a stormy night, taking advantage of the confusion, they flee and take refuge in an old abandoned theater. There they discover, along with the props, various clothes of characters and decide to disguise themselves, one as a bishop and the other as an ancient Greek warrior. For a time they lived out their fantasies experiencing several personages and stories until they decide to rehabilitate the old theater and stage a play to get money.

Meanwhile, their families were looking for them throughout the region, tightening their grip on that fleeting and forbidden freedom.

But on the night of the premiere, to great amazement and fear their families appear, but do not recognize them, after all they were unrecognized in their roles.

In the play "Antares" a Bishop who had lost his faith and an Amazon wounded and disenchanted with the battle, finds themselves in the ruins of an old temple under a starry sky. In the dialogues the revolt and the bitterness of a life they did not want, the loneliness of those who had nowhere to go and the incomprehension of a world that they no longer understood. After all, it was their story, a story that ended in that old theater, in the last act of their own tragedy. In the end the two characters say goodbye to life sharing a poisoned chalice while looking at Antares, their red star in the sky.

While the audience applauds, Anthea and Thália join hands looking at each other for the last time, no one would separate them anymore ... they would be together forever in the constellation of scorpion!

________________________________________________

Antares - O Antagonismo Dos Impossíveis por Daniel Arrhakis (2020)

Duas jovens Anthea e Thalia apaixonam-se à revelia dos valores morais que reinam nas suas famílias . A pesar de muito diferentes, têm algo em comum, o gosto em observar o céu nocturno e em especial a sua estrela preferida Antares, a estrela vermelha na constelação de Escorpião.

Mas há algo mais que as une, o inconformismo dos seus destinos e a impossibilidade dos seus sonhos. No entanto certo dia a relação é descoberta e ficam proibidas de se verem.

Inconformadas arranjam um plano para fugirem as duas e numa noite de tempestade, aproveitando a confusão fogem e refugiam-se num velho teatro abandonado. Ali descobrem junto aos adereços várias roupas de personagens e resolvem disfarçar-se, uma de bispo e outra de antigo guerreiro grego. Durante algum tempo viveram as suas fantasias experimentando vários personagens e histórias até que com o tempo resolvem reabilitar o velho teatro e encenam uma peça para arranjar dinheiro.

Entretanto as suas famílias procuravam-nas em toda a região apertando-se cada vez mais o cerco àquela liberdade fugaz e proibida.

Mas na noite da estreia, para grande espanto e receio as suas famílias aparecem, mas não as reconhecem, afinal elas estavam irreconhecíveis nos seus papéis.

Na peça "Antares" um Bispo que tinha perdido a sua fé e uma Amazona ferida e desencantada com a batalha, encontram-se nas ruinas de um velho templo sob um céu estrelado. Nos diálogos a revolta e a amargura de uma vida que não queriam, a solidão de quem não tinha para onde ir e a incompreensão de um mundo que não entendiam mais. Afinal era a sua história, uma história que terminava naquele velho teatro, no último acto da sua própria tragédia. No final os dois personagens despedem-se da vida partilhando um cálice envenenado enquanto olham para Antares, a estrela vermelha, a sua estrela do firmamento.

Enquanto o publico aplaude, Anthea e Thalia dão as mãos olhando-se também elas pela última vez, ninguém as iria separar mais ... iriam ficar juntas para sempre na constelação de escorpião !

________________________________________________

Elements from photos of mine for the background that i take in Pena Place in Sintra, Portugal. Sculptures from stock images and images of mine, all modified for this work.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Antares is revolting. (Erol Otus from Revolt on Antares, TSR minigame, 1981; image via A Paladin in Citadel.)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking for 'Revolt on Antares'

Dear Internet,

For no reason more than nostalgia, I'm looking to buy a copy of the TSR minigame "Revolt on Antares". If you've got a complete, usable copy of the game that you'd like to sell, please drop me an email (jjohn [at] taskboy dot com). I'm not looking for a collectable, near-mint copy.

Thanks!

UPDATE (Jan 12, 2008): After a nerd-fisted slap fight on eBay over a near-mint version of the game, in which the bidding when over $100, I decided that I'd try Alibris, which has a used copy in an unknown condition for $27. Who's laughing now, TSRwhore88?

Even when I win, I lose.

FINAL UPDATE: I received RoA today and was pleased to find all the counters still attached! Near Mint, baby!

0 notes

Text

Revolt on Antares is such a fun and evocative game.

TSR's Mini Games were their answer to the microgame movement, pocket-sized board games with folded paper maps and a small sheet of counters (ad from back cover of White Dwarf 30, GW, April/May 1982)

119 notes

·

View notes