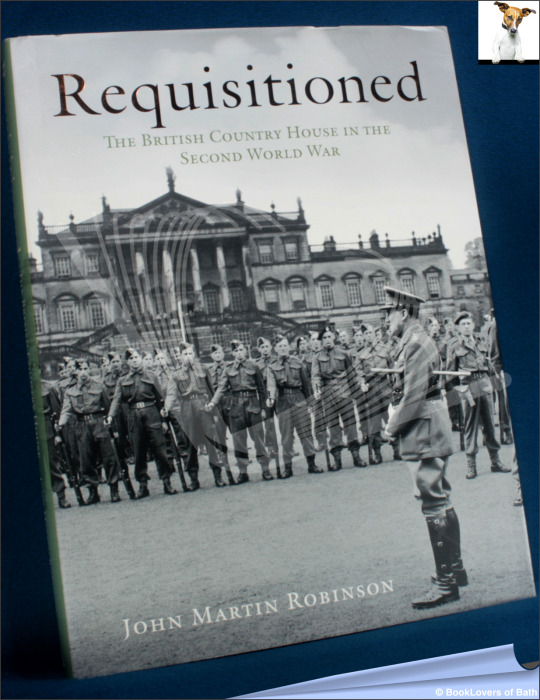

#Requisitioned: The British Country House in the Second World War

Photo

Robinson, John Martin. Requisitioned: The British Country House in the Second World War. London: Aurum Press, 2014.

Between 1939 and 1945, thousands of large houses, and their estates, throughout Great Britain were used for various aspects of the war effort, but “while it makes the the six years between 1939-45 their ‘finest hour’, it also led directly or indirectly to the destruction of a thousand of them,” John Martin Robinson writes in the introduction to this largely somber book.

Houses were left in such poor condition in 1945 that they seemed beyond restoration. Without proper maintenance, pipes burst, ceilings collapsed and dry rot rampaged everywhere. The thousand or so country houses demolished in the decade that followed the war were largely delayed war losses and were a direct result of wartime mistreatment. ...

Many requisitioned houses were never privately lived in again after the war. Some families lost everything, house and estate ... Hundreds of houses were demolished as a direct result of wartime damage. They were abandoned by their owners who could not afford to repair them after the vicissitudes of requisitioning, or were too discouraged to contemplate the task.

If you regard any of the foregoing as a sign of progress or cause for cheer, then I should tell you right up front that Requisitioned isn’t for you. Here’s Robinson on the phenomenon of such houses being volunteered for wartime use, making actual requisitioning unnecessary, a phenomenon that he maintains was fairly common:

Such gestures were a continuation of the Victorian aristocratic public spiritedness which played such a strong role in the war. It could be argued that leadership during the Second World War in Britain was more strongly upper class than during the First. This did not just include the contribution of the country house, but the fact that the government was full of peers, more of the generals were upper class and the prime minister himself was the grandson of a duke.

You get the picture, I’m sure. Robinson (more about him here) is so thoroughly on the side of the estate owners that he completely ignores the well-documented Nazi sympathies of the wartime Duke of Westminister (see here, for example), whose seat, Eaton Hall in Cheshire, was among the houses razed after wartime use. (He does, however, mention in passing the similar views of the 12th Duke of Hastings, who inherited Woburn Abbey in 1940, but “was considered a security risk and not allowed anywhere near Woburn by the authorities.” The house was used by the Foreign Office’s political intelligence division and survives today in much reduced form.)

Having said all of that, Requisitioned does offer good brief pre-war histories of each of the 20 houses it covers, as well as fairly detailed descriptions of each house’s post-war trajectory. It also contains some terrific photographs of the houses and their interiors, taken throughout the period covered. What we don’t get, or at least not consistently, is a sense of the significance of the houses’ contribution to the war effort. This book is worth looking at if its subject is of interest. But proceed with caution - and, perhaps, a willingness to giggle a bit.

#world war II#u.k. home front#requisitioning of private property#Requisitioned: The British Country House in the Second World War#john martin robinson

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thomas Headcanons: Hiro

Hiro was built around 1937, and was unique among the thousand-odd D51s for having been constructed to standard gauge - most of Japan’s railways were built to a gauge of 3′6″. This was because many of the country’s locomotive manufacturers had licenses to construct Japanese-designed engines for export to other countries - mainly those using the same track gauge.

However, one such manufacturer - nobody is quite sure which one - wanted to expand their business to countries that employed standard gauge, and so Hiro was built as a proof of concept to test the feasibility of adapting the design to the wider gauge. Other than this, and a few other detail differences, Hiro’s design is largely the same as a conventional D51.

At the time, there were only a few small pockets of standard gauge lines across the whole of Japan, and had Hiro been intended to work on such lines, he would have been of limited usefulness. That being said, he did spent a few months flitting between these various lines for test purposes. Unfortunately, this did not result in any sales, as none of the lines that tried Hiro out had the capacity to employ such a large engine on a long-term basis.

Hiro would end up seeing more use much closer to home, as his main role was to prove the merits of his design to potential investors and buyers. Sadly, this still didn’t result in any sales or export orders, and the manufacturers began to question the wisdom of their own ambitions...

Fortunately, in early-1939, someone did finally take interest in Hiro. Namely, some representatives from a British locomotive builder - again, we’re uncertain as to exactly which company they represented. Anyway, they were suitably impressed when Hiro was demonstrated to them, and an agreement was reached whereby they would be granted the license to construct a modified version of the design in Britain. As part of the deal, Hiro himself was to be shipped to Britain, in order to serve as a test bed for these new modifications.

The arrangements took time, and were put on hold following the outbreak of the Second World War. It was not until August 1940 that any serious thought was given to trying to ship Hiro out, and it wasn’t until that September that he actually left Japan on a ship heading to Britain. It was most unfortunate, therefore, that during the voyage, Japan should end up joining the Axis Powers, effectively putting them on Britain’s most-wanted list.

Obviously this blew all the plans for Hiro out of the water, and to make matters worse, he didn’t realize anything was amiss until his ship docked at Southampton, barely a day after the alliance had made the news in Britain. As a result, all the ship’s crew and cargo were taken into custody, and Hiro himself was kept in storage while the government figured out what to do with him.

Around this same time, the British government had been setting up internment camps to hold enemy aliens - that is, people living in the country who were from any of the Axis nations (Germany, Italy, and now Japan). By far the biggest and best-known of these camps were situated on the Isle of Man, but it is also known, albeit little recorded, that additional camps were set up on Sodor - sort of as an overflow, should the number of internees become too much for Man to handle on its own.

It should be noted that Sodor’s government were pretty much forced into this course of action by their larger neighbours. They weren’t proud of this at the time - and still aren’t, as a matter of fact - and while they’ve never tried to hide it from the people, they’ve never gone out of their way to draw much attention to it either.

Anyway, the point of mentioning all this is at some point, someone had the idea of sending Hiro up to Sodor to be stored for the duration of the War. It made sense at the time, as the island was far enough off the beaten track that Hiro could be hidden with relative ease, and hardly anyone would know he was there. And if somehow his cover was blown? Well, the rest of the network rarely paid attention to the North Western Railway anyhow, and they need never find out, right?

At the beginning of December 1941 Hiro was duly transferred up to Sodor under cover of darkness, and hidden on a siding off the old Ulfstead branch line (this is the line that branches off west of Maron, and is not to be confused with the later extension of the Ffarquhar branch). This line had never been particularly well looked after, and so it didn’t take long for Hiro’s hideout to become totally overgrown with trees, completely cutting him off from the outside world.

Incidentally, the timing of this operation couldn’t have been more fortuitous. Just a few nights later, Pearl Harbour happened, and anti-Japanese sentiment in Britain skyrocketed as a result. So, yeah, it was a good thing Hiro was forced into hiding...

It seems the government all but forgot about Hiro after hiding him away, and as a result he remained hidden for forty-odd years, and in that time, the old Ulfstead line went through many changes:

Having seen limited use even before the War, the line ended up being closed altogether, following the opening of the Ffarquhar branch extension in 1972. The tracks remained in situ, serving as an alternate route in emergencies.

In 1973, however, the line was reopened in order to serve the ill-fated Boulder Quarry. Needless to say, this didn’t last long, and the line was mothballed shortly after the quarry’s closure.

Finally, in 1976, the line was reopened again, to serve the Boxford family’s newly-constructed summerhouse (the one seen in Edward The Great). How Hiro was never uncovered during the house’s construction is anyone’s guess, though in fairness the undergrowth had gotten even worse by then.

It was not until early 1981 that Hiro was finally rediscovered, and like so many things on Sodor, he was found quite by accident (although his was an unusual case, in that nobody was looking for him in the first place). In 1981, the Duke & Duchess of Boxford decided to move to Sodor permanently, and had their summerhouse rebuilt and expanded accordingly. The Ulfstead branch was upgraded to allow Spencer to access the Boxford estate, and it was while clearing back the worst of the undergrowth that Hiro’s siding was uncovered - and Hiro himself with it.

Sir Topham Hatt was naturally intrigued when he heard Hiro’s story, and decided there was no harm in letting him stay and work on the NWR. However, he at least had the sense to check this over with the British government first, and they were only too happy to let him keep Hiro - the only real difficulty came in convincing them that they’d requisitioned Hiro in the first place!

Despite having been abandoned for about forty years, Hiro was still in surprisingly good condition - when he was first hidden away, he’d been prepared so that he could be returned to service at a moment’s notice. Obviously plenty of work still had to be done on him, but his overhaul was completed in much less time than had been expected.

It was during this overhaul that Crovan’s Gate managed to put together all the plans and drawings needed to make spare parts for Hiro. Although this would prove expensive in the long run, it was still much cheaper than having to order parts all the way from Japan.

Hiro officially entered NWR service in the summer of 1981, and was allocated to Barrow-In-Furness sheds. He has remained there ever since, and mainly works on the Main Line. While he has no personal preference, Hiro is much more likely to be seen hauling freight than passengers.

His current number, 51, is apparently the one found on his tender when he was rediscovered. He believes it was originally D51, and placed there by his builders as an additional promotional aid.

#thomas the tank engine#the railway series#sodor#island of sodor#north western railway#ttte headcanon#ttte analysis#ttte hiro#hiro the japanese engine

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

British WW2 prison camp where every inmate was a genius | Daily Mail Online

On a cloudless blue day in early September 1940, an extraordinary audience settled down for a piano recital in an elegant seaside square, surrounded by terraces of neat Edwardian boarding houses.

There, a group of British Army officers were laughing and smoking next to their wives on a crescent of chairs in front of a specially constructed wooden stage.

Behind them were hundreds of men arranged in untidy rows on the lawn, while others crowded the windows of the houses all around.

Together, these men comprised a dazzling cross-section of luminaries from the worlds of art, fashion, media, technology and academia that would have made for an exceptional gathering in any circumstances, let alone behind the palisade of barbed wire that surrounded the gathering.

The outbuildings and internees at Hutchinson Internment Camp. The men were among 1,200 inmates of 'P camp', known as 'Hutchinson' because it had been built on Hutchinson Square in Douglas, Isle of Man

The men were among 1,200 inmates of 'P camp', known as 'Hutchinson' because it had been built on Hutchinson Square in Douglas, Isle of Man. The camp was so overcrowded that internees had to share beds, no matter how esteemed they were.

Most were refugees from Nazi Germany who had been rounded up as 'enemy aliens' at the outbreak of the Second World War. Many were Jewish.

Status and class had provided no protection amid a national panic about 'fifth columnists' and nests of Nazi spies. Oxbridge dons, surgeons, dentists, lawyers and scores of celebrated artists were taken, including Kurt Schwitters, the 53-year-old Dadaist painter and poet, in front of whose 'degenerate' work Hitler had sarcastically posed.

Police arrested Emil Goldmann, a 67-year-old ethnology professor from the University of Vienna, in the grounds of Eton College. At Cambridge University, dozens of staff and students were detained in the Guildhall, including Friedrich Hohenzollern, also known as Prince Frederick of Prussia.

The concert's star performer, the pianist Marjan Rawicz, was a favourite of British royalty and had played a benefit concert broadcast live from the London Palladium days before his arrest.

He agreed to play behind the wire on two condition: he would choose the concert programme and play a Steinway grand piano.

Thus Rawicz performed a wide range of pieces, from Strauss's Radetzky March to Bach, and showtunes such as Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, to rapturous applause. Rawicz opted for the quintessentially English finale, Greensleeves, followed by God Save The King, which brought the audience to its feet to belt out the national anthem in variously accented English.

Rawicz's choices pinpointed the absurdity of their situation. Here were refugees from Nazi oppression, pledging loyalty to a country that had imprisoned them on suspicion of being Nazi spies.

Hutchinson had all the trappings of a PoW camp, including a barbed-wire palisade, armed guards, roll calls – everything, in fact, except searchlights and watchtowers. Pictured: Paul Hamann working on a small carved figure

Remarkably, they resolved to make the best of it. With time on their hands, and some of the best brains in Europe, this assortment of artists and intellectuals turned Camp P into the impromptu 'Hutchinson University'.

Hutchinson had all the trappings of a PoW camp, including a barbed-wire palisade, armed guards, roll calls – everything, in fact, except searchlights and watchtowers.

Yet it had been set up in the middle of the town. The Government had requisitioned a self-contained group of 45 imposing nine-bedroom boarding houses used for middle- class beach holidays until the war put an abrupt end to business.

Now it contained perhaps the most extraordinary set of captives ever assembled.

The publisher André Deutsch rubbed shoulders with sculptor Siegfried Charoux, whose work later adorned the Royal Festival Hall, and fashion designers whose clients included Coco Chanel, Pablo Picasso and Margot Fonteyn.

On only the second day of Hutchinson's existence, a small group of men had emerged from one of the boarding houses carrying chairs.

Each picked a spot in the garden square, clambered on to the seat and began to hold forth on his area of expertise – everything from Greek philosophy to synthetic fibres. Soon the square was filled with internees wandering between the lectures.

The young art historian Dr Klaus Hinrichsen watched this unfold as he stood next to Bruno Ahrends, an architect who had designed Berlin's influential modernist housing estates. Ahrends decided that order was needed.

He asked Hinrichsen to accompany him to the camp commander Captain Hubert Daniel's office to seek permission to set up a formal schedule. Thus 'Hutchinson University' began.

Internees who had given up their education – or had seen it cut short by the Nazis – eagerly embraced an opportunity to learn from some of the best-regarded scholars in Europe. For the professors, here was the chance to teach after years of enforced silence. There was also a well-subscribed technical school, which taught maths, electronics, science and engineering.

Abstract painting 'The Doctor' 1919 by Kurt Schwitters, from a private collection that includes the artist's work

The 'university' took care of the inmates' wider wellbeing, too. There was a newspaper, 'The Camp', chess, football, gymnastics and an early form of aerobics – movement set to music.

Sunday night was concert night, and, as well as the option to take a daily walk through the local countryside under armed escort, there were twice-weekly sojourns to the beach, where internees were allowed to swim.

Hutchinson soon gained a reputation as the 'artists camp', but it was master printmaker Hellmuth Weissenborn whose idea brought the artists in the camp together.

He noticed that in the absence of blackout curtains (the ship carrying the material to the island had been sunk), Hutchinson's windows were covered either with polymer film or with black or blue paint.

One day Weissenborn took a razor blade to the film, cutting a mythological scene into one of the windows of House 28. The image brought light and fantasy into otherwise depressing rooms. He began to cut more: centaurs, a unicorn, a dolphin-rider and, in the kitchen window, plates of food and fruit.

The craze spread. In House 19 the sculptor Ernst Müller-Blensdorf engraved two naked women on a beach with a seagull lasciviously hovering overhead. Others adorned their windows with worldly objects of desire: whisky, lobster, cigars. Johann Neunzer, a 50-year-old lion tamer at what was to become Chessington Zoo, cut wild animals into the bay window of House 40 – a rhino, a giraffe, a camel and the backside of an elephant.

As well as commercial artists such as Willy Dzubas, a producer of exquisite art nouveau travel posters, and the cartoonist Adolf 'Dol' Mirecki, there were more than 20 professional artists and sculptors at Hutchinson camp.

The political writer Heinrich Fraenkel was commissioned to write a book while in Hutchinson about the experience of being an anti-Nazi German in Britain.

The distinguished statistician and later head of the Royal Opera House, Claus Moser, was also imprisoned on the island. The former Berlin art dealer Siegfried Oppenheimer became their unofficial spokesman and cajoled Captain Daniel into providing them with artists' materials, with the aim of organising an art exhibition.

But by the end of 1940, the plight of the refugees was becoming a political scandal. The Government responded by organising a programme of gradual release.

Those left behind delighted in the news that the first man to have been unconditionally freed from the camp was, apparently, the elephant keeper from London Zoo.After he was arrested, the elephants refused to eat – or so the story went. This romantic tale, often repeated later by Hutchinson alumni, was only partially true. The man in question, Hans Honigmann, had worked at London Zoo, but he was no mere elephant keeper. A respected zoologist, Honigmann had come to Britain in 1935 at the invitation of the biologist Sir Julian Huxley and had the unenviable accolade of being named in the Third Reich's notorious black book, a list of individuals to be killed by the occupation forces in the event of a successful invasion of Britain.

Inevitably, however, the best connected were the first to leave. Pianist Marjan Rawicz was released after composer Ralph Vaughan Williams petitioned the War Office.

The absurdity of locking up refugees from Nazism as potential spies for Hitler was revealed in 1942 when many of them joined the British Army as soon as they were offered the opportunity. Among the units bolstered by internees were the Special Air Service, the Commandos, the Special Operations Executive, the Royal Navy, Royal Armoured Corps, the Royal Artillery and the Parachute Regiment.

Many Hutchinsonians were among the 4,000 internees who joined the Pioneer Corps and participated in the Normandy landings in June 1944. Those who were too old or too infirm to fight found other ways to contribute.

Polish pianist Marjan Rawicz (1898-1970), on left, and Austrian pianist Walter Landauer (1910-1983) of piano duo Rawicz and Landauer posed together at a piano in England in July 1949

The Hutchinson optician Horst Archenhold designed the periscope used to turn Sherman tanks into amphibious craft on D-Day. Joseph Otto Flatter produced cartoons for propaganda leaflets, more than two billion of which were dropped over Germany in a campaign to sow discouragement and dissent among enemy troops.

'I saw my cartoons as substitutes for bombs and shells,' he said.

Dr Arthur Bratu, who ran Hutchinson's 'Cercle Française', worked as a public prosecutor in the post-war de-Nazification process. The Ministry of Information enrolled Dr Walter Zander to tour Britain and educate servicemen about anti-Semitism.

Walter Neurath, who helped produce the popular Britain In Pictures books, was released to continue his work, which had been deemed useful propaganda by the Ministry of Information. He went on to set up the Thames and Hudson publishing house with his wife Eva, who had previously been married to another Hutchinson internee, Wilhelm Feuchtwang.

In the decades that followed, many Hutchinson alumni – and those who had been interned in other camps – made substantial contributions to British culture.

An astonishing number of those whom Britain interned as 'enemy aliens' remained in Britain after the war, including Eduardo Paolozzi, a father of British 'pop art', the Nobel Prize-winner Max Perutz, and the international judge Sir Michael Kerr.

They included the conductor Peter Gellhorn and the violinist Norbert Brainin, who was a founding member of the Amadeus Quartet, three of whose four members met while interned on the island.

Embarrassed by their accents, names and history, these men sought to integrate and assimilate as quickly as possible following release, many changing their names to British variants. Peter Fleischmann became the artist and teacher Peter Midgley.

With hindsight, many of the internees came to recognise they had been comfortable, safe and generally well treated as internees, in benign contrast to the appalling Nazi concentration camps. But they also have a warning.

'I often ask myself if internment could happen again,' said former internee Claus Moser. 'The nice answer is, 'Good God, no.' But I think it could. Not exactly in the same circumstances.

'But I was in Whitehall for ten years and occasionally [civil servants] are forced into crude, panicked emergency measures that have not been prepared adequately.

'Politicians get terribly worked up with the crisis of the moment, which they hadn't thought about before... it could happen again.'

© Simon Parkin, 2022

The Island Of Extraordinary Captives, by Simon Parkin, is published by Sceptre on February 3, priced £20. To pre-order a copy for £18, go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937 before February 7. Free UK delivery on orders over £20.

This content was originally published here.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Head Cannon Biography and Character Analysis and of the Captain, Part 5: Everything the Captain Does Wrong in the First Flashback of Reddy Weddy in Sixteen Points

Which finally gets us back to the flashback scenes in Reddy Weddy.

Is this about to be over 2,000 words shredding the command performance of my favorite character? Yes, it is, but I do it with all the love in the world.

I’ll start with the first scene, which starts out as a morning brief. It shows just how awful he is at the whole ‘leader of men’ thing. What did he do wrong? This is going to go on for a while. The TLDR version is: literally everything. There is not a single word or action of his in that scene that went right. And it had to be intentional, as Ben Willbond is an admitted military buff, he has to know what proper military bearing is supposed to look like, and he wrote the episode.

I should preface this with saying that I absolutely adore the Captain in this scene, with his silly, over-excitable and ridiculously awkward self. But the first time I saw it, the part of me that spent four years in the US army was screaming inside about how terrible his performance was as a CO. Just picture yourself as one of those respectable and sensible young military personnel sitting in the seats listening to him with the thought, ‘if the Germans come this is the guy that’s going to be responsible for me in battle,’ and try not to cringe just a little.

First, starting with a bit of background: morning briefs are torture. They are the most boring things in the world. Everyone hates them. They’re one of those situations when you can just feel yourself slowly dying. Good commanders know that and try to keep them as short as possible. Bad commanders who don’t mind that their troops are silently hating them the whole time go on a bit longer, but even then, I don’t think I ever sat through one that made it through more than five or six points. The Captain’s very first line in the episode states that he is on POINT NUMBER SIXTEEN (the absurdity of which gave me the handle for this side-blog). His subordinates are blank faced. They’ve probably been tuning this tedious BS out since point number four.

Second, point number sixteen is, to paraphrase, “Why am I still hearing laughter after hours? We are at war. Fun is banned.” In a stern lecture tone. No, Captain, pet, just because the army probably sucked all the joy out of your life, doesn’t mean that no one is allowed to be happy in the military, even during wartime. My dear, actually you should be encouraging them to decompress however they can, as long as it isn’t inappropriate or interfering with their duties, because war is stressful, even if you’re not on the front lines. The military in general is stressful, even when you’re not at war. Joking and horseplay- as long as it isn’t the sort of thing that isn’t going to get anyone injured- is good for morale. And modern militaries have morale officers for a reason. At this point, the man in the middle of the front row breaks his blank face momentarily to give the woman next to him a ‘can you believe this crap?’ look.

Third, the Captain goes on and backs this up by essentially saying (again paraphrased), “I understand you all are bored, I’m bored, too, this shit is boring, but this is where the army stuck us so we have to deal.” Which again is the wrong answer. That is precisely how NOT to motivate people to do their best. This is a situation where the officer should try to generate enthusiasm amongst his subordinates for their roles. Even if he wanted to provide a similar sentiment, the word ‘bored’ never should have entered the equation. Everyone is bored most of the time in the military, but it’s not something the higher ranks acknowledge, because acknowledging it helps nothing. His statement should have been something more like, “I understand that some of you are frustrated that you’re not serving in combat, but what we’re doing here in support of the war effort is important, and it will take all of us doing our parts, both out there on the front, and back here in England, to win this thing.”

Next, when Havers comes in with the message for him, he speculates out loud about it being an answer to his pistol requisition. He shouldn’t have done this, and gets two wrong points for it.

The fourth is because while I find his excitement about that pistol endearing, like a little boy hoping for just the right present from Santa at Christmas (and still pining for it 75 years after his death, as noted in the ‘going to the shops’ game with Fannie in s2e4), it probably comes off as foolish or childish to his subordinates. The gun he really wants to have probably should not be the first thing that comes to his mind when communicating with command. There’s a war on. There have to be at least one or two things that are more important.

The fifth is because you’re not supposed to reveal any of your command requests to your subordinates until you know how they’re going to turn out, and then only the ones that are approved, because if you reveal you’ve requested something and it isn’t granted, particularly something as simple as being issued a side arm, it starts to look like higher command doesn’t favor you or have confidence in you. Which in his case is probably true. But that’s not something he should reveal to his troops by way of letting them know he requested a fancy new side arm and then never received one. He might as well have put a sign on his back that said, “Command trusts me so little they won’t even give me a gun.”

Sixth, when he reads the actual message, he just blurts out something to the order of, “good god, France has surrendered.” Which is not how the other people in the room should have received that information. There should have been some sort of measured, more dignified, official sounding announcement. “It’s my duty to inform you all that unfortunately France surrendered to the Germans yesterday,” or something of the sort at the bare minimum. But no, he just blurts it out. Well, Havers asks him what’s wrong after the “good god” part, but he still shouldn’t have blurted it out.

Seventh, and after blurting it out, he doesn’t add anything to it. France surrendering was a disaster for the British during WWII. It meant Germany was coming for them next. This would have been the time to reassure his men- and women- that although things might look grim, he was confident that high command had a plan and would have everything under control and that there was no way Germany would make it across the channel and that even if they did, the army would be ready. But no, he says nothing of the sort.

Eighth, in fact, he says nothing else to the people who had been present for his briefing at all. After Havers enters the room, he has neither eyes nor words for anyone else. Which is not professional at all.

Ninth, the way he looks at Havers throughout this scene, his face lights up, his voice cheers, his whole demeanor changes. He might have well had a neon sign glowing above his head that screamed ‘I’M GAY FOR THIS MAN!!!’ It would have been the only thing that could possibly be more obvious. When, again, being gay wasn’t okay at all in 1940’s England, and particularly not in the army. I love how incredibly unsubtle he is about his attractions while he clearly thinks he’s being subtle, but that’s not the way it would have been viewed by the people in the room.

Tenth, in his excitement, the Captain just drops the message on the floor. Drops. It. On. The. Floor. He doesn’t even bother to pick it up. Even Havers gives him a funny look for this one. I say again, I find over-excited Cap adorable. His subordinates probably find this ridiculous, though. And if this were a man who was in charge of me and he’d just been giving me a tedious lecture about not laughing at night as part of a sixteen point morning brief, I’d find him ridiculous, too. At best.

Eleventh, then he immediately scrambles to the window and looks around wildly like he expects the Germans might be marching up Button House’s driveway as they speak. Which is plain silly, as Havers has to point to him. It’s obvious to anyone with sense that even if the Germans are going to invade, it will take them a while to organize an invasion, and Button House is unlikely to be one of the early strategic targets. But the Captain seems to forget this momentarily in his excitement and ends up looking silly in front of his subordinates. I’m pretty sure a few of them are laughing at him in the back.

Twelve, the fact that the Captain is clearly ridiculously excited about this development at all is another point against him, because he shouldn’t be. Of course, he’s excited about the renewed prospect of getting a chance to actually fight (see the previous part of this analysis for why he desperately wants such a thing) but that excitement is not good look. He’s thinking about what it means to him personally, rather than what it means to the military and the country as a whole. Again, the fall of France was a disaster for Britain. It means they’ve lost all of the battles they’ve fought to try to hold back the Germans in France. It means they’ve already lost thousands of men attempting to hold back the Germans in France and for nothing. It means they’ve lost their main ally, the ally the spent years successfully holding back Germany with in France in WWI and therefore implies that this war is going to be even worse than WWI, which was already unprecedentedly catastrophic. It means they’re alone against Germany and there’s a good chance that Germany will be invading soon. So, when they get this news and the Captain’s reaction is over-excitement, that does not look good for him. Nothing in this brief looks good for him, of course, but he just keeps digging the hole deeper.

Thirteen, his officer’s bearing (which as I mentioned in an earlier post as one of the indicators before Reddy Weddy of him probably not being a very good officer, as he maintains it well in emotionally neutral situations, but once emotions enter the picture it collapses) starts out fine when he’s actually giving the brief and then goes downhill once Havers enters the room and by the time he’s at the window, his body language is just… what are you even doing? He’s practically bouncing. Also, Cap, why are you randomly shouting? And what are you doing with your hands? (I wonder if he started carrying his pointy-stick everywhere because he couldn’t figure out otherwise what to do with his hands.) Of course, all of this is because he’s a magnificent over-excitable creature, but still… not a good look as a CO.

Fourteen, when they show the rest of the personnel in the room during this part of the scene, you can see clearly on the faces of the two men in from to the left of Havers (at ‘I don’t think they’ll be here just yet, sir’) that they think the Captain’s behavior is a joke… they fix their faces back to blank very quickly, but it’s there. I imagine what most of the men under his command felt for him was either ridicule or contempt, sadly. I feel sad for him, because I want my poor gay son to be loved and respected. But he isn’t in this situation and he doesn’t seem to either notice or care about this.

Fifteen, Havers has to remind the Captain that protocol states they’re supposed to lock down the estate at this point, as the British actually were expecting the Germans to invade after France fell. He shouldn’t have had to have been prompted, particularly not in front of their subordinates.

Sixteen, Havers also has to pretend that the Captain ordered everyone else in the room to go carry out the lockdown, when he didn’t, just shouted vaguely about it being a good idea. Havers then sends them on their way, as it’s clear that in his own excitement, the Captain seems to have forgotten that he’s the one in charge and supposed to be leading and commanding. But I suppose it’s good that Havers took the initiative to get everyone else out of the room as quickly as possible, as this has been literally only like a minute of time, and I’d hate to see how much Cap could embarrass himself in two minutes.

And there it is. I made this sixteen points long as an illustration of just how ridiculously long sixteen points actually is.

I won’t cover the part where the Captain and Havers were alone at the end of this scene, yet, as I’ll include it with the next written bit, which is going to be my analysis of their relationship. That might be a minute, because we’ve reach the end of the parts I actually had significantly written out. I’ve only outlined the Havers relationship section.

#the captain#bbc's ghosts#havers#reddy weddy#the captain was terrible at being a captain#guys help i've put more effort into this analysis of a fictional character than i did for my senior thesis in university

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Requisitioned: The British Country House in the Second World War :: John Martin Robinson

Requisitioned: The British Country House in the Second World War :: John Martin Robinson

View On WordPress

#978-1-7813-1095-3#art stores#ashley western#blenheim palace#books by john martin robinson#castle howard#chatsworth#country houses#first edition books#government requisitioned#hatfield house#military headquarters#military history#military requisitions#penrhyn castle#southwick house#strategic headquarters#tyneham house#wartime occupation#wilton house#world war 1939 1945#world war 2#world war effort#world war ii#world war two

0 notes

Link

BRITISH LABOUR PARTY leader Jeremy Corbyn has a bold proposal to house the survivors of a devastating fire at London’s Grenfell Tower apartment complex in empty luxury homes.

YouGov polling found that Corbyn’s idea is popular among the British public, with 59 percent supporting it. Yet there has been a harsh backlash from the U.K.’s right-wing government and press, which equated his plan with a Marxist plot. “Suggesting requisitioning empty properties when empty student accommodation is available locally is completely in line with his Marxist belief that all private property should belong to the state,” Conservative MP Andrew Bridgen said.

But Corbyn’s plan has historical roots not in Marxist literature or state-run economies, but in his country’s own past.

During the Second World War, Great Britain faced one of the most powerful war machines in human history in a conflict with Nazi Germany. Its government responded by asking all of its citizens to contribute to the war effort in different ways.

For some, this included giving up their property. To help bear the brunt of the Nazi war machine, the British government requisitioned both industrial and residential properties to accommodate soldiers and evacuees, run makeshift schools and hospitals, and train the military, among other uses. As the U.K.’s National Archives website notes, “14.5 million acres of land, 25 million square feet of industrial and storage premises and 113,350 non-industrial premises were requisitioned during the Second World War. The War Office alone requisitioned 580,847 acres between 1939 and 1946.”

Architectural historian John Martin Robinson documented much of this requisition process in his book “Requisitioned: The British Country House in the Second World War,” which looked at how large country estates were used to house military personnel and evacuees, the latter mostly being children. Some of the properties that ended up being used to house soldiers or civilians were among the grandest in the country — they included castles, palaces, and abbeys owned by some of the country’s richest citizens.

Residents of one of these large homes requisitioned for the war effort, Spetchley House, are interviewed in the documentary “Stately Homes at War.” The house was originally planned to be a fallback shelter for Prime Minister Winston Churchill in case of a German invasion, but ended up being used as a place for recuperation for American Air Force pilots. The two residents of Spetchley House interviewed were just children at the time, but they understood housing the American soldiers as a patriotic duty.

“There’s no question that those young men did go to Hell and back,” Juliet Berkeley, who was just nine years old when the war began, said of housing the American soldiers.

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#uk politics#labour party#jeremy corbyn#grenfell tower fire#capitalism#socialism#democratic socialism

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday, August 4th 2018 – Basildon Park, Berkshire

Headed for an evening at a particularly excellent restaurant in Berkshire (or possibly Wiltshire – I haven’t double checked yet) we were casting around for something to do in the afternoon, to make it into more of a “holiday” than just a trip out for dinner. After casting around for a while, and lighting on a number of possibilities that we then rejected on the grounds that a sunny Saturday in August would be more crowded than we could deal with and hang on to our sanity we realised that Basildon Park was not that far off our route, and neither of us had ever been, or in fact knew anything about the place.

I suppose I knew it was nowhere near Basildon, which is probably just as well, given that a) Basildon is an unremittingly grim sort of place – or at least it was back when one of our friends used to live there – and b) on the wrong side of London given where we wanted to be. Actually it’s close to Reading (which is not that thrilling a place either but nowhere near as bad as Basildon), but we didn’t go there en route anyway, just headed down a series of quite small and lovely country lanes until a final slightly unexpected veer off into the car park, which was full. We were directed to the also pretty full overflow car park. It looked as if the whole world (or at least a large part of the Netherlands) had decided to visit all at once.

However, once we arrived at the ticket office we could see that there was a great deal of space available inside in terms of grounds at least – the house was not visible from there – and so we decided we’d nose around the house first, and then, if it had cooled off at all, we might take a stroll around the grounds should we still have time.

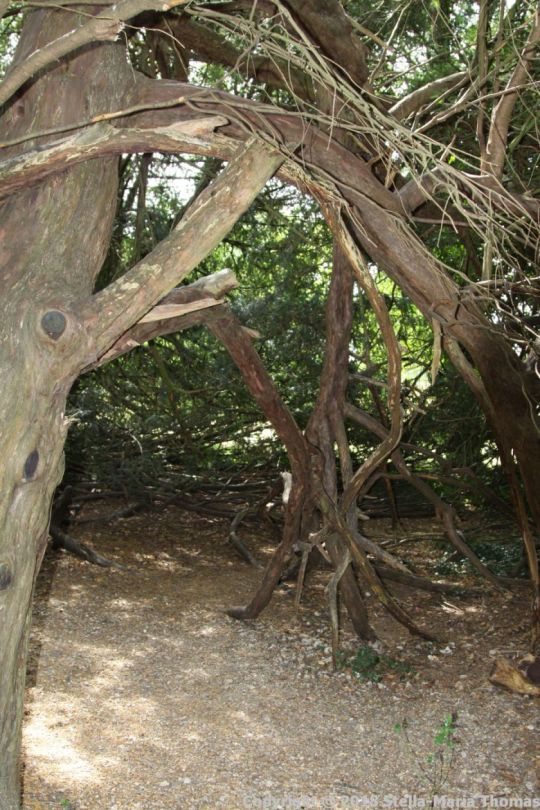

The walk through the woods to get to the house was lovely, and cool, and reminded me somewhat of the path between the car park and the castle at Burg Eltz, though less steep.

It also contains a number of fun benches with carved wooden animal heads for armrests…

And some very Tim Burton-esque trees! I know I kept expecting a hobbit or two to pop out from behind the trees any second.

Anyway, reaching the house it was soon apparent that it’s an interesting structure, very much the picture of Palladian symmetry, which I think is pretty rare. Most houses have had bits added on (or removed), and so they don’t have quite the precise frontage that Basildon Park manages. The estate was bought by Francis Sykes, who had made a fortune in the East India Company, and it was he who demolished the house that was already there and had John Carr, the architect, build him a new one. Most people who know Carr’s work won’t be surprised by the style, but the location is unusual; he didn’t normally work outside Yorkshire and its immediate vicinity. As a Yorkshireman himself, Sykes managed to persuade Carr out of his normal geographical comfort zone, and work began on the house, though it was not completed in Sykes’ lifetime, which presumably didn’t help his political ambitions, given that he’d bought the estate because he required a house suitable for entertaining that would also show off his at this point considerable wealth and that was close to London. He wasn’t alone; many rich returnees from India settled in this part of Berkshire, so much so that it became known as “the English Hindoostan”.

Sykes plans to rise politically and socially met with mixed success and when he died at his London house on 11th January 1804, none of the principal rooms at Basildon Park were completed. They didn’t get much love afterwards either, with the heir, also Francis Sykes, died a few weeks after inheriting the unfinished pile. Next in line was Sykes’ grandson, the five-year-old third baronet. As he grew up he showed no sign of financial sense, and pretty much bankrupted the family fortune by the time he was 14, an association with the Prince Regent not helping at all. In 1829 the estate was placed on the market, but it didn’t sell for a considerable period of time because Sykes would not lower the price below £100,000. As a result the house was often let out over the 9 year period it was on the market, finally being sold to the entrepreneur James Morrison for £3,000 under the £100,000 asking price. He completed work on the house and filled it with treasures, working with architect John Buonarotti Papworth to create what Morrison described as “a casket for my pictorial gems,” which included works by John Constable, J M W Turner and many Italian and Dutch old masters. Morrison died at Basildon on 30th October 1857.

Morrison’s daughter, Ellen, inherited the house and live in it until her death in 1910. It was then inherited by her nephew, James Morrison, who made some improvements initially, including commissioning Edwin Lutyens to design workers’ cottages in the neighbouring villages. He didn;t live in the house though, and in 1914 it was requisitioned by the British Government and used as a convalescent home for injured soldiers. After that period, Morrison’s lavish lifestyle and three marriages meant he had in effect run out of money, and in 1929 he sold the house to property developer, George Ferdinando.

He initially planned to sell the house to an American, marketing it for sale foe $1,000,000, which would include the cost of taking it down and re-erecting it in America. Luckily for us, he changed his mind, and converted the old sawmill at the top of the park into a house for himself and his wife. He also persuaded one of his sons to return from America with his family and to take up residence in the east wing. This son, Eric, did some renovation work, including returning fittings like the stair balustrade. Some of it they could not get back, however.

In World War II Basildon was a billet for troops, and a training ground for tank and ground warfare was set up in the park. Damage was perhaps inevitable, with walls damaged by bridging units used on the river and massive holes left behind. Requisitioned by the Ministry of Works, it suffered further indignities when a caretaker stole the lead from the roofs.

The ministry would not pay for most of the damage, and Ferdinando moved out, leaving Eric to deal with the house. When his father died, between inheritance tax and the repair costs, the house had to be sold. Despite its rather sorry state, the second Lord Iliffe, who lived in the area, bought it under persuasion from his wife, Lady Iliffe. Lord and Lady Iliffe spent 25 years restoring and refurnishing the house, buying fixtures and fittings from similar houses that were schedule for demolition, finding that 18th-century mahogany doors and marble fireplaces fitted in the spaces available perfectly in many instances. Having no children, the Iliffes donated the house and park to the National Trust in 1978, along with a large endowment for its upkeep.

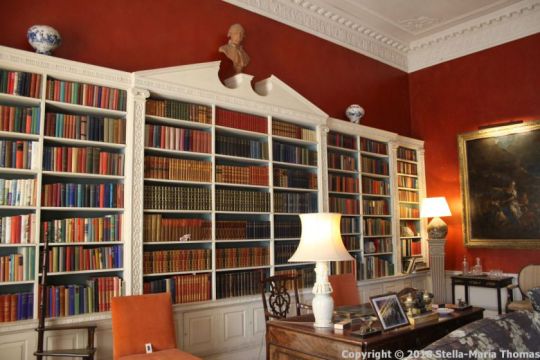

It may not be the most spectacular architectural gem, and it’s not the home of any especially notable art works now, but its sheer survival makes it notable, given the state it had been reduced to when the Iliffes took it on. We actually started outside the house, nosing into the cafe and buying a cold drink each, needing to refresh ourselves after a two hour drive and the woodland walk to the house. Next to the cafe area (which is on the ground floor under the main house) was the original kitchen, in the north pavilion, away from the main house to avoid kitchen smells in the living quarters. Because Palladian buildings need symmetry, there thus had to be a second pavilion, in this instance a laundry. To avoid food having to be transported across an open area in all weathers, when Lady Iliffe was modernising the place she had a new state of the art kitchen installed on the piano nobile, but that was to be seem later in our visit.

Before that we also walked around the rose garden, which apparently looks towards the River Avon (though you can’t actually see it), but sadly the roses were pretty much past their best after the summer we have been having. There are some statues in the garden, several of them headless after being used for target practice by American soldiers billeted in the house in WWII.

After that we headed into the south pavilion, where there was an exhibition of “domestic” paintings, At Home with Art – Treasures of the Ford Collection, most of them the sort of thing that would have covered the walls in houses like this, produced more as a form of wall covering than art of great merit. It was interesting enough, though I doubt anyone apart from historians of the domestic would go out of their way to see it.

The house, thankfully, is more interesting, and the volunteers in particular are very keen to offer any information you might want to make your visit more informative. In addition, it turned out that photography was permitted in the house with a couple of exceptions (the portraits of each of the Iliffes, which I was a bit baffled by, and what is known now as the Sutherland Room, formerly Lady Iliffe’s dressing room, which contains studies for Graham Sutherland’s tapestry “Christ in Glory” which decorates Coventry Cathedral which I can understand).

The hall contains a lovely ceiling which is actually original, unlike much else to be found in the house. It has of course been renovated. The hall also has its original Spanish mahogany doors, removed in the 1920s, but returned in 1954. It also contains one of a number of white marble fireplaces salvaged from Panton Hall prior to its demolition.

Of the rooms I particularly liked the Octagon Drawing Room, which was used to display the owners’ best art works. It was restired and the walls covered in red felt, and renewed with works from Pompeo Batoni and Giambattista Pittoni. I loved the shape of the room, and the way the three windows provide fabulous views over the park and surrounding countryside.

The Dining Room is a lovely space, decorated in a neoclassical style, and it too has had a somewhat chequered history. In 1845 it was redecorated by the architect David Brandon, who replaced the original paintings with polychrome depictions of Dante’s Divine Comedy. The walls were not much changed though, retaining their 18th-century plasterwork. In 1929, Ferdinando stripped the dining room of its panels, mirrors, fireplace and doors and sold them to Crowther’s, a firm of architectural antique dealers. They were sold to what was until last year the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York where they formed the Basildon Room. Lord and Lady Iliffe opted to redecorate it in a style similar to the original scheme by de Bruyn, using Carr’s surviving plasterwork, and a fireplace and doors salvaged from Panton Hall to return the room to its original neoclassical form.

The second floor, with all the bedrooms, is also interesting with the Shell Room probably the most startling. Apparently, shell collecting was very much a thing for ladies at one stage, and they have been used to odd and slightly alarming effect to decorate pretty much any surface that didn’t need to be flat!

The Bamboo Bedroom is rather fun too, the bed having apparently cost £5 in an auction.

The rest of the room is of course decorated to suit.

Also on display is a spectacular Coromandel screen, which is a 17th century Chinese lacquerware screen, unusually made for the Chinese domestic market not for export, and is one of a handful of such items now left in the UK. It would likely have arrived in the UK along with the newly popular pursuit of tea drinking in the 17th or 18th century,, and depicts a famous gathering of scholars in the garden of the Emperor’s son-in-law in the 1100s. Half of it is apparently missing, with just six panels remaining, but as it was not uncommon to cut down Coromandels to create other pieces of furniture, it’s more remarkable perhaps that half of it has survived. It’s even more remarkable that it’s still intact now, having been bought to hide a toilet door from guests by Lady Iliffe. It had started to deteriorate because of the conditions in the cloakroom, but is now on display and undergoing restoration. It’s really spectacular!

I’d love to know what it would have looked like when complete! It was towards the end of the visit and we finished off by diving into the “new” kitchen I mentioned earlier. It’s very, very 1950s and we had some fund spotting things that were familiar to us. I would have happily made off with the picnic basket, mind. It was very stylish.

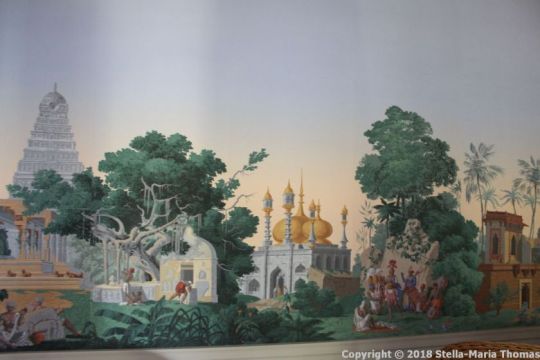

We were about ready for some more refreshments, so an ice cream and a sit down were the order of the day (and I was very pleased to find a raspberry Magnum on sale). After that we took a wander into the Garden Room, which Lady Iliffe was in the process of converting to an “Indian” room to reflect the heritage of the house when she died. It’s lovely, but incomplete, and will presumably remain that way now.

And then it was time to retrace our steps through the woods, back to the car, and on to our destination for the evening.

Travel 2018 – Basildon Park, Berkshire Saturday, August 4th 2018 - Basildon Park, Berkshire Headed for an evening at a particularly excellent restaurant in Berkshire (or possibly Wiltshire - I haven't double checked yet) we were casting around for something to do in the afternoon, to make it into more of a "holiday" than just a trip out for dinner.

#2018#Arts#Basildon Park#Europe#Lower Basildon#Museums#National Trust#Sightseeing#Stately Homes#Travel#UK

0 notes

Text

Neil Anderson Interview Transcript

Neil Anderson

00’22 R: Can you give brief timeline of key events of two nights of Blitz?

N: Months before the outbreak of war people started to talk about evacuation and getting the children evacuated out of the city because Sheffield was always seen as high on the German target list because of its reputation throughout the world for its steelwork production and armaments. One we got up to the war lots of public buildings were requisitioned as public air raid shelters, 10,000 of Anderson shelters were distributed to the Sheffield population then the first outbreak of war was soon as the phoney war because there wasn’t a mass of air attacks and gas attacks on people. But then, into 1940 Hitler started to begin air campaigns on Britain and London was hit and then other key cities were hit such as Liverpool and Coventry before Sheffield and I suppose they were the key events and then obviously Sheffield Blitz happened December 12th and 15th of 1940.

2’03 R: What effects did the Blitz have on the people of Sheffield?

N: Certainly I have come to the conclusion that the raid was a more terror raid to terrorise the Sheffield population, I had no idea until I started my research of how widespread the bombing had been on Sheffield there had hardly been a suburb which hadn’t been hit because I was always let to believe that they were here to hit the steelworks and I thought if that was the case why weren’t all the steelworks put out of action for a length of time, you know why where the Germans bombing places like Totley and Dore which were miles away from the East End? You know surely the target couldn’t of been that bad.

3’01 R: Leading onto that, do you think this was a more people terror attack than a steel work attack?

N: Well, in our research we found original German bombing maps of Sheffield and though the steelworks were down as targets they were down as secondary targets, the primary targets were hospitals, schools, university buildings, railways you know as it to really terrorise the population as really the opposite seems to have happened. It seem to have really made the people of Sheffield more determined than ever to get behind the war effort, I know Sheffield was held up as an example by the then Prime Minister Winston Chruchill as an example of if you are facing this type of bombing look to Sheffield in how you will react and recover from it.

3’59 R: What areas of Sheffield were most badly effected?

N: To bombing hit virtually every suburb of Sheffield, in terms of casualties I think one of the biggest areas, the City Centre was very badly hit obviously the city centre you know there’s not a lot of people you know there’s loads of the key department stores which were all raced to the ground like the moore was completely decimated. But in terms of civilian population, Devonshire green the big park that was a big community back to back housing that there was mass causalities on there. It was one of the biggest loses of life even though there was over 2,000 people killed or wounded over it was very spread out that was one of the biggest concentrations. And also the maples building that was big 7 story public house/hotel that received a direct hit that was the single biggest losses of life. But in terms of the bombing it was right across the city, and them when they came a second night it was more concentrated on the east end but again there were no steel works which were put out of action for any length of time, so it wasn’t the kind of bombing that was expected.

Different shot: 6’08

6’10 R: How well prepared were the people of Sheffield for the bombings?

N: I think they were as prepared as anywhere really, I think at that point we were ready for invasion I think that also was one of the biggest things errr because the idea was that the Germans wanted to win air superiority and the plan was to invade and the fact that they were already in Paris you know they were in a few miles of the South coast. Houses were prepared all the kind of cellars had you know structures to Shelter people bombing and air raid shelters were widespread and distributed, there were scores of public air raid shelters around the city. But I think in many respects you speak to a lot of people and because of there being so many air raid warnings and not any bombing a lot of people had become very ‘barsay’ about it. I have spoken to a lot of people who have said you know we were sick of going to and paying for the cinema and then half way through the air raid warning would go off we’d leave and then the air raid attack wouldn’t come and a lot of people said we are just going to stay and watch our film. I think this is one of the first times that the air raid warnings went off at 7:00pm and within a few minutes they heard the sound of anti aircraft fire British guns which hadn’t been heard before because this was the real thing. But generally people were prepared they were just quite blarsay because there had been so so many false alarms over the months.

Different shot: 10’10

10’18 R: How well did Sheffield recover from the Sheffield Blitz?

N: I would say in terms of many cities bomb site became a feature for years after, places like say Atkinsons department store on the moore which is still there, probably only surviving independent store from that era which is still here that place was raced to the ground. That place took a full 20 years to be rebuilt so they didn’t open store till 1960 but in terms of the recovery effort and the public it was all coordinated through the central library on surrey street and they had kind of scores of council officials in there if you’d lost loved ones if you’d lost your house if you’d lost gas or electricity they were the people to see. Because you know there were thousands, nearly a tenth of the city’s population made homeless it was that widespread, there was thousands of people who came there to get help and stuff. Apparently people were very calm and collected but a lot of people went into rest centres which were set up around the city in kind of schools and stuff so a lot of people that were made homeless they were moved into places like that and a lot of people opened up their homes to relatives or strangers until their houses were rebuilt. I know that there were scores of builders and joiners who came in from all around the regions to help, I spoke to people out in Chesterfield who were all working in Sheffield to help start to rebuild the city. But obviously, it took months years to get back on its feet, as the bombing was that wide spread. And I think that’s one of the tell tale signs that you can see today, I was amazed how little there was to mark the Blitz.

00’18 (second clip) R: What evidence is there you have seen to show the Sheffield Blitz was more a terror campaign on the people than on the steel works?

N: Mine is just another theory, but it seems for me, I just thought you know the surely the targeting isn’t that bad, apparently it was a very clear night and they did hit the armaments factories on the second night they came. But I think for me the bombing maps we found, it would make sense the way they were bombing was similar to how they were in other places so it just seemed to be a logical theory that it seemed to be more of a terror raid.

01’24 R: How crucial were the steel works to the allied war effort?

N: Pivotal, on all accounts. I think one of the main things that Sheffield made were crank shafts for the spitfire engines, it was a key drop hammer that we had here in Sheffield. And apparently if that would have been wiped out that would have significantly impeded the British fight back. But you know they were making so many things, parts of planes, parts of ships, tanks just so much. And you kind of forget that it was actually the women who were working in them because the men were out fighting the wars so it was the kind of women of Sheffield we were actually working doing the shifting to make all these happen so you know there was just so many thousands of people employed in these massive steel works.

02’30 R: Did those involved in the steel industry understand that they could potentially be targeted?

N: I would say very much so, but I think things like the Blitz unless like even if air raid sirens going off I think they had to keep working, I think if only bombs were actually dropping then they would be taken to an air raid shelter. I know quite a few women who I’ve spoken to who have worked in the factories that they said they had to work through the air raid sirens and keep production up. But no they were very much aware of the hazards involved.

Different shot 04’13

04’21 R: How well did hitler understand that the Sheffield steel works were important to the allied war effort?

N: My guess is, it would make sense that Sheffield was way high up on Hitlers hit list, I think the whole made in Sheffield brand was well known right across the world. And it was certainly known, even in WW1 we were often one of the errr one of the strap lines for Sheffield was ‘armour to the country’ and I know there will have been quite a few from what I understand German reconnaissance in the UK in the 1930’s to look at key cities so, I think it was widely known how important Sheffield was in the production of armaments.

Different shot 6’33

6’52 R: asking his theory of whether it was steel works or terror raid?

N: Certainly my months, probably years of research and talking to scores of people has definitely, errr, I would certainly go with the theory of that it was more of a terror raid to actually terrorise the people of Sheffield. Just knowing the bombing they have done on the places and I think you know the sheer size of you know these armament factories and the massive cluster down the east end and the fact that they didn’t knock one of those out significantly when they had the capacity to you know it certainly leads me to the theory that it was more a terror raid. In terms of my research it’s not finished yet, we are very keen as a part of the ongoing research that there is a lot of luffwaffer paper work in the Bunderzine archive in Berlin that we are keen to actually go in and have a look at and get more evidence from the German side. In terms of their records and what they were working to, so you know in terms of a theory it might change in the coming months but that’s ongoing research which we are leading into.

0 notes

Photo

Mosley, Leonard. Backs to the Wall: London Under Fire, 1939-1954. London: George Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1971; reprint, as Backs to the Wall: The Heroic Story of the People of London During World War II, New York: Random House, 1971.

Each generation gets the history that it needs — or wants, or demands. That’s what kept going through my head as I read Backs to the Wall, which appeared three years after France’s youth explicitly rejected both Charles de Gaulle, the self-appointed leader of the Free French during World War II, and the political ideology that he represented, and amidst ongoing unrest over the Vietnam War. (It’s also worth mentioning that it was published in the same year as Norman Longmate’s How We Lived Then: A History of Everyday Life During the Second World War and two years after Angus Calder’s The People’s War.) This book gives up a World War II narrative in which Churchill was an improvement on Chamberlain only in that he wasn’t an appeaser, de Gaulle was worse than both of them put together, the Allied leaders all cordially loathed each other, half the British public wanted to sue for peace, and there was across-the-board mutual dislike between London civilians and American troops (and British dismay at the way African-American troops were treated by their white counterparts was far from universal). Do I exaggerate? Only slightly. Backs to the Wall is a sort of distant, city-specific pre-echo of Juliet Gardner’s sour 2004 book Wartime: Britain, 1939-45.

As with Wartime, however, this book does have the virtue of introducing us to a number of very interesting people. I became interested in reading it because it brought Vere Hodgson’s wartime diary to public attention. Mosley quotes or paraphrases Hodgson’s writing from the beginning of the war through its end, and also seems to have interviewed her extensively. His primary villain, meanwhile, is not Chamberlain but Chamberlain’s chief acolyte, Henry “Chips” Channon, from whose diary he quotes widely (and who turns out to have been born and raised in the United States, to my surprise). We hear a great deal from the chemist and novelist C.P. Snow and follow the misadventures of two civilians, Jenny Martin and Polly Wright, whose consistency in both bad luck and bad choices meant that neither of them was able to stay out of serious trouble for any length of time.

There are many glimpses of the London home front through the eyes of two boys, both eight when the war began: John Hardiman, of Canning Town and later of Aldgate, who was evacuated in 1939 but soon returned to London, and Donald Ketley of Chadwell Heath, who was never evacuated at all. Donald, who thoroughly enjoyed himself during the war, had an experience that speaks to our own recent reality:

Another good thing: quite early in the Blitz, his school had been totally destroyed by a bomb. Since Donald was shy, a poor student and unpopular with his teacher, he was overjoyed when he heard the place was gone. Thereafter he went each day to his teacher’s home to pick up lessons, which he brought back the next day for marking. In the following months he changed from a poor student to an excellent one, and although he was aware that his teacher rather resented it, he didn’t care.

Mosley also introduces us to Archibald McIndoe, the real-life counterpart of Patrick Jamieson, Bill Patterson’s character in the Foyle’s War episode ‘Enemy Fire.’ Art seems to have imitated life pretty accurately in that instance: he and his burn hospital in East Grinstead were apparently exactly like what was depicted, the only difference being that the hospital was set up in an existing hospital building, not in a requisitioned stately home.

Backs to the Wall seems to have been one of the earliest books to make substantial use of Mass-Observation writings. Most M-O diaries are anonymous, but there are two named diarists here who stand out. John James Donald was a committed pacifist whose air of lofty detachment as he observes the reactions of those around him to air-raids and other wartime event and prepares for his tribunal — which, in the end, he decides not to attend — quickly grows irritating. More interesting is Rosemary Black, a 28-year-old widow, in no small part because she differs markedly from what I had thought of as the archetypical M-O writer. Here’s her self-description on M-O documents: “Upper-middle-class; mother of two children (girls aged 3 and 2); of independent means.” Mosley continues:

She lived in a trim three-story house in a quiet street of the fashionable part of Maida Vale, a short taxi ride from the center of the West End, whose restaurants and theatres she knew well. She was chic and attractive, and lacked very few of the niceties of life: there was Irene, a Hungarian refugee, to look after the children; Helen, a Scottish maid, to look after herself and the house; and a daily cleaning woman to do the major chores.

Black took her children out of London at the beginning of the war but quickly brought them back, and when bombs began falling she kept them in place — air raids might be disruptive for them, but apparently relocation had been worse. She was very much aware that she was riding out the war in a position of privilege, and she often expressed guilt feelings; but this tended to fade away before her irritation at the dominance of “the muddling amateur or the soulless bureaucrat” in the war effort. Offering her services, even as a volunteer, proved very frustrating. “She was young, strong and willing; she typed, spoke languages, was an expert driver and had taken a course in first aid,” Mosley tells us, “but finding a job even as a chauffeur was proving difficult” in September 1940. (She actually wasn’t all that strong physically: as we learn, she suffered from rheumatism which grew worse during the war years and probably affected her outlook.)

Black was greeted with “apathy and indifference” by both A.R.P. and the Women’s Voluntary Service. Early in 1941 she was finally able to get a place handing out tea, sandwiches, cake, and so on to rescue and clean-up workers at bomb sites from a Y.M.C.A. mobile canteen. She was a bit intimidated by the women with whom she found herself working:

Their class is right up to the county family level. Nearly everyone is tall above the average and remarkably hefty, even definitely large, not necessarily fat but broad and brawny. Perhaps this is something to do with the survival of the fittest.

And the work did bring her some satisfaction, even if it was of the type that lent itself to being recorded with tongue placed firmly in cheek:

We had a pleasant and uneventful day’s work serving City fire sites, the General Post Office, demolition workers and Home Guard Stations, etc. We were complimented at least half a dozen times on the quality of our tea ... I think the provision of saccharine for the tea urns to compensate for the mean sugar allowance is my most successful piece of war work. What did you do in the Great War, Mummy? Sneaked pills into the tea urns, darling.

For all her good humor and astute observations, Mrs. Black was far from immune to tiny-mindedness. After an evening out in 1943 she wrote:

I had to wait some time for the others in the cinema foyer, and I was much struck, as often before, by the almost complete absence of English people these days, from the capital of England. Almost every person who came in was either a foreigner, a roaring Jew, or both. The Cumberland [Hotel] has always been a complete New Jerusalem, but this evening it really struck me as no worse than anywhere else! It is really dismaying to see that this should be the result of this war in defence of our country.

Indeed, Mosley cites the results of a multi-year Mass-Observation study that showed a marked increase in anti-Jewish views London’s general population over the course of the war. Since it’s just one study, and since I haven’t seen that study mentioned anywhere else, I am reluctant to trust blindly in its accuracy; and there’s also this:

The small flat which George [Hardiman] had procured for [his family] ... in Aldgate was cleaner and airier than the old house in Canning Town [which had been bombed], and the little Jewish children with whom John now went to school seemed to be cleaner than the ones in Elm Road; at any rate, he no longer came home with nits in his hair.

On the other hand, Mosley himself gives us only a fragmentary view of London’s wartime Jewish population: everyone seems to be either a terrified refugee or an impoverished East Ender. We hear nothing about the substantial middle- and upper-middle class population — mostly of German descent and in some cases German birth — that had already taken shape in Northwest London; and while we are briefly introduced to Sir David Waley, a Treasury official, in connection with the case of an interned Jewish refugee, we aren’t told that Waley himself was Jewish, a member of “the cousinhood.” On yet a third hand, Mosley also quotes other M-O surveys from the same period that indicate largely hostile attitudes to most foreigners in London, with Poles at the bottom of the ladder and the small Dutch contingent on top. (Incidentally, the book’s extremely patchy index identifies Vere Hodgson as a Mass-Observation diarist, which she wasn’t.)

Backs to the Wall closes with a very brief, remarkably non-partisan account of the 1945 general election and its immediate aftermath. “Neither side had any inkling of the way the minds of the British voters were turning,” he writes.

When [Churchill’s] friends suggested that he was a victim of base ingratitude, he shook his head. He would not have such a charge leveled against his beloved countrymen. Ingratitude? "Oh, no," he said quietly, "I wouldn’t call it that. They have had a very hard time."

The book is worth reading for the primary materials that it includes, but it probably tells us as much about the era in which it was written as about the period that it covers.

#world war II#u.k. home front#london#non-fiction after the fact#recommended with reservations#long post

2 notes

·

View notes