#Reiger Records Reeks

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Roland Kayn — Orthyrsis (Reiger-Records-Reeks)

This 2006 offering in the Roland Kayn archival series contains some of the most beautiful harmonic moments in his ever-growing catalogue. Taking a page from Horton’s playbook concerning meaning and utterance, I must mention the elephant in the room. Despite planned process and whatever compositional conundrums it entails, Kayn is always something of a Romantic. If further proof were needed than his Dino Concerto, it’s right here, in Orthyrsis’ first wide-open gestures, a bit soiled but sinewy and smooth, an inviting and slightly unstable mixture of sustain and light.

Kayn’s harmonies are nowhere near conventional, and, like the wonderful Robert Fripp guitar solo on the studio version of “21st Century Schizoid Man,” they certainly avoid conventional resolution. Obviously, they emerge from pitch aggregates, and pitch is another fascinating element of whatever layers in dialogue Kayn’s latter-day compositional syntax involves. The sounds of organization and reshuffling with which we all became inordinately familiar on the Gargantuan A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound are ever-present. The ruffles and wrinkles of real-time tape manipulation, to dizzying effect, is integral to Kayn’s layers and repetitions as sounds warp, crinkle and sometimes blink out of existence only to jump-cut back a moment later. If recent conjecture about Kayn’s later work involving subjecting his earlier compositions to arcane revamping is correct, some of the pitch elements probably hail from early 1980s pieces like Scanning. There and in Orthyrsis, the pitch formations can be uncanny in conjuring shades of the slow movement from Bartok’s second piano concerto, and they return after some warp and weft at 3:51 and 8:32, rendering so much of the immediately preceding material somehow parenthetical. The pitches glide along under layers of what may be another version of the same material in dialogue with itself. Only as the piece unfolds do those pitch formations shape-shift to sound “major” or “minor,” possibly indicating a bit of plunderphonics added to the mix, as in his first electronic symphony. That upper timbral layer’s manipulation sometimes sounds as if it’s being improvised, as when at 8:24, it skips across that frozen pond the pitched sustains constantly threaten to become.

The half-hour aphorism — because that’s what it is in a universe where the nearly 14-hour Milky Way is possible — is a largely gentle affair. The ruptures and sudden resurgences are relegated to that upper layer under which tones unfold with a glacial majesty. The barely change register, except that something faint, inhabiting a space somewhere between a timpani and a tubular bell, pervades the final chilly minutes. Most astounding though, and despite the similarity of process that makes Kayn’s language unique, is each piece’s autonomy. Orthyrsis is nothing more or less than individual in the vast organism that is Roland Kayn’s legacy.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#orthyrsis#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetics#electronic#experimental

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best of 2024

Roland Kayn - Hybriditys (RRR, 2024)

#2020s#Germany#Roland Kayn#Electronic#Experimental#Cybernetic Music#Electroacoustic#Dark Ambient#Drone#Soundscapes#RRR#Reiger-records-reeks#2024#gurus of electronic music#Best of 2024#Bandcamp

2 notes

·

View notes

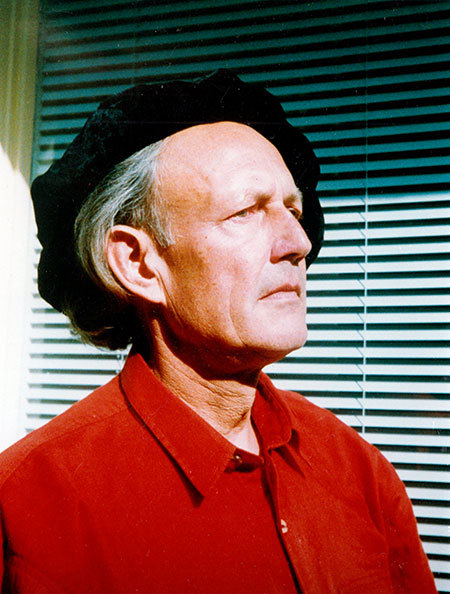

Photo

Roland Kayn - Cyber Panoramical Music

Reiger-records-reeks

2022

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — Sorales II (Reiger Records Reeks)

Sorales II by Roland Kayn

The deeper a dive taken into the elastic sound worlds conjured by Roland Kayn, the harder the bedrock obviously underpinning his alternately molten and frozen universe is exposed to be. Sorales II, the most recent release in the growing Kayn archive series, beggars description and confounds expectation yet again through a very surprising sort of unification.

Of course, and as always, the music is riddled with disruption. Given its 2005 vintage, that’s no surprise, and there’s plenty of what sounds like tape manipulation, that dizzying pitch shift and wrinkling effect that pervades the Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound. We are treated to the huge and all-encompassing “major chord” at 10:18, or the intriguing, because so rare, rhythmic layers that occur at least twice, the first forward and the second in reverse. They disappear with the rapidity of their genesis. Even the near silences adorning the last several minutes don’t so much disrupt as posit moments of repose in a quiet storm. The non-sequitur at 28:11 isn’t one really, and more on it presently. In those and all other cases in the 33-minute miniature, disruption is not as much of a primary ingredient. Its presence is subservient to another element, a fresh but slowly moving deep-down thing, a unity in diversity of which those New England Transcendentalists would have spoken with a mixture of pride, admiration and Classical allusion.

It seems a shame to evoke the concept of a drone in this particular instance. Yes, seasoned Kaynians will certainly recognize the long sounds that germinate, ebb and flow, often with fundamental disruptions of their own, especially throughout Kayn’s later works. This drone is different. It’s neither Vanessa Rossetto’s looping palimpsests nor Keith Rowe’s hiss, fizz and crackle conglomerations of radio static, interference, room buzz and charcoal, though it sits adjacent to both. Charles Ives would understand. His “Unanswered Question” or “Central Park In the Dark” contain string passagework that exists in similar spaces, even if the harmonic language diverges. Kayn is a Romantic, and the girders of the second Sorales prove it. Triad and elusive counterpoint emerge and merge from the cross-pollinations of tone and color that bunch, breathe, bunch again and writhe in a way that’s nearly human. Mountains and rapids form a landscape of constant motion dotted with reflective pools of moonlit tone throughout the pitch spectrum, including a single icy note approaching the stratosphere and illuminating all below. Everything is slathered in reverb, never distasteful but definite, a foundation of distant calm beneath lopsided cycles in movement. Listen closely as elements surface, half-repeat and sink. Even the disruptions, like the afore-mentioned sudden juxtaposition and the final gesture of the work, grow out of what has just occurred and out of the reverberant atmosphere containing it. It’s all cold, sometimes even windy as pitch blurs into frosty air, but it’s breathtakingly beautiful from beginning to end.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#sorales II#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#electronic#classical

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — Sezarytes (Reiger-Records-Reeks)

What is to be done? Positing that Roland Kayn’s music is like no other, while true, is both incomplete and the biggest copout imaginable when discussing a body of work so unified in its diversity. Sezarytes is yet another 2006 composition, and there are enough of them to boggle the brain, but while there’s no mistaking the composer, the challenge lies in the description. What, just as a simple case in point, is to be made of the fragment, 9:10 into the 50-minute piece, of what might be a heavily processed bit of “traditional” music? Nearly but not quite severed from its surroundings, it gives rise to an echo, a kind of ghost-tone certainly related to it but of a different texture, stone suddenly morphing into water with a single high-register luminosity shining over everything, though nothing is elucidated.

Again, where is Kayn to be placed? If Jaap Vinck is a sonic kindred spirit to Kayn’s late 1970s and early 1980s corpus, I have heard nothing that sounds like Kayn’s post 2000 compositions. Yet, comparison remains an easily followed temptation. The overlapping sound worlds of Charles Ives or Ruth Crawford Seeger might be fruitful points of entry into Kayn’s ever-challenging cybernetic compositions, though the timbres resemble more completely the every-day interjections of Ives’ early 20th century musings. Even to suggest that Sezarytes is a work of disjuncture, of point and counterpoint in rapid-fire and disparate dialogue evoking the Expressionists, is both apt but too often false to be useful. Dig into the absolutely spell-binding music from 11:46-12:17, to which affixing terms like “drone” or the more irritatingly vague “sustain” does nothing but injustice. Vinck and Steve Roden come to mind, but the gradual swell and dynamic shift underpinning the stunningly minute pitch changes are of another vocabulary. That fragment of music stands somehow aloof, an open invitation starkly apart from the succeeding rupture, grind and gurgle industrializing the fragment that ends, sporting the most adorable little tail, at 13:08. Then, and most vexing, what is there to be done with the bit of disembodied laughter floating in a reverberant void at 19:52? It sounds, for all the world, like Kayn’s earliest cybernetic work for Deutsche Grammophon from the late 1960s as part of its seminal Avant-Garde series. Does Kayn’s reboot of earlier material also include interpretations of that material? Is he writing the book of himself writing the book of himself, etc?

My critical chops are bloody from battering my skull against these walls of mirrors! It’s damn attractive music, to these ears at least, and reasoning not the need is no substitute for intellectual or philosophical penetration. Reference is as vague as it is tantalizing, and at the end of the day, there’s nothing to do but sit back and listen again.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#Sezarytes#Reiger-Records-Reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#electronic#experimental

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — Actual Basic Elements (Reiger Records Reeks)

Actual Basic Elements by Roland Kayn

“The movie will begin in five moments,” intones Jim Morrison. It’s a pivotal moment on his American Prayer album, a public announcement amidst the often-private musings that comprise much of his poetry. Roland Kayn’s music is nothing if not cinematic, and Actual Basic Elements, a recent addition to the Kayn downloads series, brings public address into its narrative fold through extensive use of the human voice. Yet, other modes of expression occupy equal areas of sonic space as the music fragments and crystalizes, contributing to the narrative and providing the occasional plot twist.

It's the way the voice is used that differentiates Elements.” As far back as 1970s Cybernetics 3, human voices and animal sounds merged in the only slightly veiled comradery afforded by Kayn’s unique vision of acousmatic sound’s evolution. Kayn’s choice blend of action and non-action was refined over the next three decades, making this unified half-hour miniature possible. The opening conjures visions of an extraterrestrial public address system in overload, the voices buttressing the soundscape that morphs into its own soundtrack as tones emerge from vast sonic complexes. The voices hold all together, especially in the earlier parts of the reverberant score, often eclipsed but emotively clear. True to its 2005 vintage, the piece is a study in environment, expanding and shrinking in accordance with whatever processes Kayn initiated at its genesis. The Gargantuan reverberant spaces return at 5:10 and at a much higher pitch nearly four minutes later. The score, the nearest musical descriptor that makes any sense, is also rife with recurrence, as with the single pitches returning throughout at various registers. Even these can’t dispel the tape-effect disorientations also typical of the period, as at 19:07, when those dizzying luffs and waves support an only slightly oscillating tone, the whole approximating nothing so much as radio static.

Repeated listening drives the radio metaphor, yet another mode of public discourse, home with authority and conviction. Near the end of the piece, we even hear a bit of unadulterated “smooth” jazz, nearly unadorned, before it dissolves, its components demonstrated to be a major ingredient of what I insist on calling the score. That instant of musical mundanity lays bare a crucial element of what has been occurring to that point, begging other questions. Are the voices meant to simulate tape effects and the music bits of elongated radio transmissions, all layered in Protean combinations? Again, the acousmatic lies at the music’s heart, even if its purpose and execution are worlds apart from territories carved out by Kayn’s colleagues. It’s all quite delicate and elastic, vocal inflections reflecting the sonic fluidities supporting them. The only frustration is the sudden conclusion, a problem in search of resolution.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#actual basic elements#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#electronic#classical#experimental

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — Reversioni Comprimati (Reiger Records Reeks)

Reversioni Comprimati by Roland Kayn

Roland Kayn’s work is continually and wonderfully confounding, not least in the way he names his work. Look at this title. Does “Reversioni” imply something of a returning, a backward glance? The more we learn about Roland Kayn’s huge archive, especially from such a narrow time period, the more it seems as if each piece is a vast interconnected revisitation of his earlier work. Only the modes of construction and execution vary.

The sound of tape manipulation unifies this 36-minute miniature. Listen to the beautiful minor chord at 10:50 and how its speed suddenly ratchets up beyond all recall a moment later. Having heard it, the sounds immediately preceding and succeeding it are given fresh context. The mid-spectrum climax at 15:01, thunderous in its impact, bears further witness to the aesthetic governing this work’s construction. More pointillistic manifestations lead toward the 20-minute mark and flank the liquid major chord at 22:35.

The standard Kayn tropes are here in force. The sounds are glittery and grungy by turn, while consonance and dissonance can switch places in the blink of an eye. Timbres are deliberately obscured, unlike in other contemporaneous (2004) pieces, where sounds are laid basically bare. Above all though, those moments of instability so much a part of Kayn’s later work, the sudden heart-stopping removal of carpet from underfoot, govern the piece’s trajectory. Listen at 33:24 to scale the heights of vertigo-inducing pitch shift, but that’s just one of the more extreme and prolonged examples. It’s a constant, just as much a staple as those sounds in constant flux and return.

Where does it all come from? In most electroacoustic music, even when obfuscation occurs, the sound sources are fairly close to identifiable. One of the marvels of Kayn’s work is its timbral consistency, whatever the sound sources happen to be. Reverb-drenched, dynamically extreme and eschewing any conventional narrative form, there is no doubting the composer for a moment. In this case, there’d also be no doubting the compositional provenance. The process seems as unconcealed as do the orchestral and vocal sources of other works, or sections of larger works. Is it really possible that such a simple rule, or model, could manifest such a complex story?

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#Reversioni Comprimati#Reiger Records Reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#experimental#cybernetic#tape manipulation

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — The Art of Sound (Reiger-Records-Reeks)

The Art of Sound by Roland Kayn

It isn’t so much that familiarity breeds contempt. It can foster a kind of sympathy, a kinship, a comfort as inhabitation simplifies and the language becomes familiar, all this possibly leading to apathy. This has not happened where Roland Kayn’s ever-fascinating and so-often inscrutable music is concerned. Are those sounds moving forward or backward? What are they anyway? Does the music live closer to something adjacent to the orbit of a tonal or atonal universe? The worst, and the best, is that it’s all loads of fun! The Art of Sound is one of the longer Kayn miniatures, like the similarly named Sound Hydra, and here, miniature connotes a two-hour work rather than the 10 or 15 hours of Scanning and A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound respectively. A better but more elusive name could not have been chosen for this late composition!

It always happens in similar fashion with Kayn’s work: A moment emerges, sometimes with force and at others with sheer beauty, coming on multi-directionally, like the wind as freefall begins. At 12:07 of “Soundways,” The Art of Sound’s hour-long third movement, there’s something approaching a cadence, one loosely of the “Amen” variety, but, as with so many elements in the Kayn sonosphere, it advances glacially. It engulfs with an almost repentantly warm introspection, an unapologetic statement of Romanticism that distills the watery beauty of Dino Concerto into a moment of delicate transition. If Jean-Claude Eloy or Eliane Radigue incorporated a similar gesture, it would probably be supplemented with an undercurrent of extramusical association. This is not to disparage the work of either of these two pioneering composers! Kayn relies more often on a kind of abstraction, which makes this moment all the more poignant and subtly powerful. To observe as the tones dissolve into a wavy and nearly non-pitched but luminous sound mass is one of the wonders of Kayn’s type of idea development that never becomes familiar enough to age!

At first, the movement seems closer to the speaker-to-speaker delayed ruminations of Scanning, a huge work which, like the recently and magnificently reissued Tektra, relies on a more linear kind of motion than the many early 21st century pieces now coming to light via the Roland Kayn archive. The Art of Sound hails from 2004, a fact brought home by the eventual introduction of those wonderfully disconcerting tape warps so prevalent in his final pieces. Those delays do return, and any sense of all-encompassing reverberance is thwarted by those high frequencies sticking thornily out around and well beyond the 55-minute mark.

The sense of antiquities revisited is reenforced by the other movements, especially the 48-minute “Genesis.” It hisses throughout, sometimes rumbles and often crackles, like all well-behaved old recordings should if they haven’t undergone the cruelties of filtration. From where though, comes all that delay seeming to permeate it, and when was it added? The delay is unmasked at the very end, and while many Kayn pieces sport some rather astonishing distortion at moments of climax, this seems to be a thoroughgoing aesthetic choice for the movement. Is the 25-minute “Transition” to be taken simply as its name implies? It’s conceivable that this brief movement is a more recent remix, definitely in Milky Way style, of whatever earlier material forms the other movements, if that is what has occurred. Whatever the case, the tape juxtapositions are dizzying and jarring by turn, connecting the two more meditative movements by an episode rife with industrial vitality.

To call the whole palindromic would be to miss the Mahlerian scope of the final movement, but sonically, the proverbial shoe fits. If there is a unifying factor beyond those already mentioned, it is a kind of choral gestalt, a “vocal” space obviously but maddeningly eschewing specific vocal timbres but in which lines and shapes move with a vocal fluidity and melodic grace. Like the piano fundamental to Weather Report’s “Milky Way,” the true nature of every sound Kayn employs remains hidden. Only effect can be gauged even as it dissipates. Such is the ephemeral and ultimately, ironically, human nature of Kayn’s music.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayne#the art of sound#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#experimental#classical#electronic

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — An Algorithm MA 71 (Reiger-Records-Reeks)

An Algorithm MA 71 by Roland Kayn

This 25-minute excursion might be the ideal port of entry into Roland Kayn’s world of tone-and-timbre juxtapositions. Unlike many of the download-only releases the Kayn archive’s been dropping over the last year and a half, this one lives somewhere close to being serial in form. Instead of those wild and largely inexplicable — especially on first listen — incongruities being stacked and then shuffled, there’s something very linear about the elements and their manipulation. This is not to suggest a lack of surprise but only that listening for continuity is made easier by the one-foot-after-the-other approach of those syntactical elements so familiar to anyone spending time with Kayn’s self-referential corpus.

The sonic up-flip at 0:41, like a tape suddenly slowed down in the recording process, is present in other Kayn works composed around 2004. It recurs throughout, amidst more conventional splices, as Kayn’s gossamer passages of something approaching chords float by and are then replaced by grinding industrial loops. The piece is also a beautiful study in impermanence, as even they blink out of existence at 17:17 as fractured tonality beckons again. In fact, just before vast swatches of reversed resonance conclude everything, pitched and non-pitched events coexist. The rest of the trip involves stripping away and return, the most fascinating of the latter being the resurgence, as if from under water, of sonorities now in sci-fi mode at 12:09.

All that said, the finest moment, the sonic capper, is the almost complete disappearance of sound at 11:28, very nearly dividing the work in two. Going out in a haze of reverberance, all recedes save what sounds like basically unadulterated out-door pastorality. As if partially waking from a dream, a distant cityscape comes into view, and only the reversed birds let us know that Kansas, and even Earth, are fairly far away. Talk about living inside a dream! That, though, is what’s so often at the heart of Kayn’s always similar but somehow always radically different modes of expression as encapsulated by the compositional processes he only partially controls. In that relationship, his music is no different than any other. Expectation and its opposite comingle, and the most puzzling, fascinating and ultimately gratifying variable in this complicated equation is that the language Kayn uses is so definitively his own. Like in those moments in Joyce that bestow meaning only upon re-evaluation, Kayn’s moments of near-reality bring a smile and consternation. By the early 2000s, Kayn may very well have been reassembling as much as inventing, and again, what musician in pursuit of freedom doesn’t blur those lines?

Marc Medwin

#roland kayne#an algorithm MA 71#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#electronic#experimental

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — Zone Senza Silenzio (Reiger Records Reeks)

Zone Senza Silenzio by Roland Kayn

Traveling the unparalleled but rocky paths through what we still, for lack of understanding and experience, dub the “Avant Garde” demonstrates that identification need not foster understanding. Even that conceit is illusory at best, clarity sent packing in the face of the change preceding and succeeding it. An organ, or at least one, ushers in Zone Senza Silenzio, a work newly released as part of an ongoing series from Roland Kayn’s vast archive. Distorted, rippling and fragmenting as it splutters in half-reluctant motion, it’s then overtaken, falling prey to the shock-and-scatter particles that may even have emanated from it. To what end anyway, this constant search for identification and meaning?

For anyone immersed in Kayn’s radical corpus — and radical it still most certainly is, more than six decades after its inventor discovered the cybernetics determining much of its creation — those rapid-fire reverberant sparks may seem anachronistic. A whirligig of latent computer phantasmagoria and sci-fi angst, they play to type, evoking the musique concrète universe tangentially related to but apart from Kayn’s work. The first minute of this hour-long sojourn clarifies the relationship between the composer of formal self-determination and Kayn’s historical might-have-been as the familiar tape-speed manipulations from the A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound era embattle themselves with these jousting pointillisms. As what had been familiar moments ago is warped beyond recognition, the higher frequencies are mangled and then repurposed to a muddy sheen, they themselves then warping and blinking out of existence. Then, at 7:29, as if to mock the poor analyst’s efforts, the organ in concrète mode reenters only to experience a temporal shift, another jarring series of speed-traps infusing everything with layer upon layer of maddeningly complex operation in gorgeous flux and staggering symbiosis.

It could be that Milky Way is the best point of comparison in Kayn’s daunting output. Those speed and pitch-shifting operators, not to mention the sudden blinking-out and reentry, are very similar to other pieces from the first decade of the 21st century in the way they determine perceived formal unity. The complex drones are also present; witness the glorious one at 12:15, something residing somewhere between steamboat and generator before it, too, is wiped out with the upward arc of sudden tape adjustment. The intrepid explorer in search of sonic signifier is also in luck, as with the recurrent sound-images in reverse, as at 20:07, whatever they might imply, but there again, with crystalline immediacy, are those fragments, the Webern-esque end of the dialectic. Sometimes, those fragments even take on a modicum of beat, another slight nod to a world Kayn acknowledges but neglects. Then, and most intriguing, are the elements that just don’t fit, like that chord at 24:16 and a similar but better defined version at 46:15, and what is that miniscule melody nearly half an hour in? It impinges on the senses with slinky simplicity before simply not being. No tape manipulation forces it into oblivion, and it doesn’t even fade; it just isn’t.

Despite the title, silence does often empower the work’s second half, at key moments, respite amidst the unwieldy waters of shift and transformation. If the Dino concerto drove a single point home, it involves Kayn’s Romanticism. Extremes abound, shock by shock. Length and depth, from the roaring speed-of-thought rapids to extreme delicacy in what is never quite a void, pose neither terror nor difficulty for the exploring constructor of foundations in various states of decay and reconfiguration. Yet, nothing anticipates the beat-cycles of fours and threes leading the music out, just another reminder, if one were needed, that in Kayn’s universe, unpredictability comes in many forms. If nearly an hour must pass before that playful little beat is allowed to drop, if all the slings and arrows of fortune, some outrageous, hurl uncertainty at the unsuspecting listener, then it was all for the best in music continually outpacing its own intensions and shattering expectation.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#zona senza silencio#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#experimental#musique concrete

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — Dino Concerto (Reiger-Records Reeks)

Dino Concerto by Roland Kayn

When Olivier Messiaen improvised, at least based on the recorded evidence, his playing had superficially little to do with whatever he was composing at the time. It harkened back to earlier works while projecting a rhapsodic freedom through the lens of frozen progress, a kind of captured suspension. This month’s second Roland Kayn download inhabits a similar space. In 1982, a piano improvisation for Kayn’s wife was caught on admittedly lo-fi but perfectly listenable magnetic tape. It’s a half-hour window into a private sphere, a fly-on-the-wall view of an ambient room in which the emotive spirit is glimpsed in unfettered flight.

To hear Kayn improvise is to understand what a Romantic he really was. It should have been obvious, but it’s easy to get caught up in the language of cybernetic composition, the subjugation of composer whim to process, all the concerns confronting the Kayn enthusiast in various ways throughout a compositional career of more than half a century. Even his piano works often dealt as much with sound, process and their point of conjunction as with the notes involved. His earliest piano miniatures breathed some of the same tonal air as Debussy or Messiaen, but their concision meant that immersion into formative languages was brief and slightly jarring, like a quick morning swim in chilly water. Not so on Dino Concerto, certainly not a concerto in the strictest sense but orchestral nonetheless. Like Mahler’s 9th symphony, it begins in one key and ends in another a half step removed, and its density varies with each moment, from the sparse but linear intricacies of chamber music to full-on explosions. Dynamics follow suit. The first note pops into focus as if the tape began abruptly; who knows how long Kayn had been playing? Almost immediately, as a single harmony is molded and remolded, there is a slowing and a dynamic decrease, allowing each sonority to hang suspended before an ascending melody moves things along at 0:17.

Those gestures, both expansive and somehow strangely static, set the stage for what ensues. Dig the repeated figurations at around 0:38 as a melody emerges and is then thwarted underneath only to return in expanded and altered form at around 3:22. An ending almost occurs at 4:30, in the original if slightly inflected key, but Kayn launches into something crossing ballad and chorale, brassy jazz-tinged harmonies bolstering, often stroking, a chromatically sequential melody nearly, but never quite, in triple time, a song of love and reverence needing neither beginning nor end. To posit that the emotive state is sustained until the punchy Scriabinesque chords punctuating the texture at 8:02 would be to underestimate the languid arcs, cadences and momentum, the frozen moments liquified and gelled again, of a beautifully fluid instantaneous conception, and to suggest that it all leads to the sudden outburst at 9:07 would do the same.

Articulating the network so many gestures caught in the wonderfully fractious process of rendering form from formlessness begs the question: How, exactly, do these fits and starts, angles and curves, moments of respite and mammoth explosions actually differ from Kayn’s compositions? On one level, they don’t, and that speaks to the strong and mature compositional voice coming from such a place of unity that all utterances tread the same ground. If the underlying spirit of volcanic stasis is the same, the harmonic language couldn’t be further removed from the densely packed clusters so prevalent in Kayn’s giant composed edifices. Maybe, as with the Second Viennese School composers, he simply replaced one kind of center with another, because in Dino, the center is important, even if the tonal center concluding is different from the commencement. There is something special about the idea of being home. More than anything else, listening to the flight and return throughout this gorgeously inclusive half-hour foregrounds that sentiment, that blissful sense of return, redolent of the journey but a return, bitter or sweet. One is never quite the same after, which is as it should be.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#dino concerto#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#electronics#cybernetics#classical#improvisation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland Kayn — November Music (Reiger-Records-Reeks)

November Music by Roland Kayn

The early 2000s seem to have been prolific for Roland Kayn, and here, as the first of two November 2020 downloads from Kayn’s archive, is further proof. We had the absolutely astonishing A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound, a 14-hour work released by Frozen Reeds in 2017, and now, the composer’s reactivated label, run by Ilse Kayn, is giving us several windows into the spaces attendant to that huge slab of plunderphonia. Small but crucial, November Music is an aphoristically charged portal into a larger universe of purpose and repurpose.

All of the composer’s hallmark devices are in play, from huge dynamic subversions through inexplicable diversity of timbre and placement along a constantly changing sonic continuum. In this case, Kayn seemed to be having some fun with an old-fashioned kind of delay. It’s first foregrounded at 1:32 as reversed sounds slap back and repeat in a way that’s delightfully “old school.” The effect holds the piece together, like a thin paste, though it often threatens to break apart in key places. Even so, most points of rupture, like the nuclear upheaval at 3:29, exist in that environment, a quaint reminder of music past in a world somehow inhospitable to it.

While echo and pre-echo keep things grounded, the substance itself defies unity and categorization, just as always happens in Kayn universes. Even atmospheric recurrences, like the Lynchian airflow at 5:44, just to cite one example, are really only points on a narrative scale, delicate place markers holding cataclysm temporarily at bay, like the encroaching eruption at 7:24.

Then, with neither warning nor fanfare, come those moments of complete disjuncture, a rend in the veil, the evocation at the heart of the mystery that is each Kayn composition. At 8:34, with only a trace of the pre-echo that is so integral to this particular piece, a chorus, a reversed motet or madrigal, establishes temporal concern while simultaneously obliterating it. Overhanging and haloing those measureless Coleridgean caverns, it offers something approaching but never achieving respite. Nearly buried, like revolution or illness, are the marching feet of progress, the thunder of the guns, the Gargantuan bat-wings of impending catastrophe or liberation. How is it that a composer abdicating the fetters of compositional individuality can create music so human? How can such a moment be so affecting when the frame is mean to divorce it from such emotional concerns? Even the fuzz, scronk and battle-scared landscapes of November Music’s second half never erase the memory of that supreme moment when something beautiful and noble, almost familiar, stands naked and unashamed amidst the flames, the alien tonescapes and finally, ineluctably, the silence.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#november music#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#electronic#experimental#classicalguitar

1 note

·

View note

Text

Roland Kayn — The Man and the Biosphere (Reiger-Records-Reeks)

The Man and the Biosphere by Roland Kayn

Of those involved in the ever changing universe of electronic music, none was quite as enigmatic as the iconoclastic Roland Kayn. His 2011 passing silenced a voice that was, ironically, as nuanced and eloquent as it was often rough around the edges. His pieces border on the mythic, as with the 14-hour A Little Electronic Milky Way of Sound, finally released in 2017 by Frozen Reeds or the ten-hour Scanning, which saw the light of day last fall via his own label, Reiger-Records-Reeks. Now, Kayn’s daughter Ilse is overseeing the label and has inaugurated a series of downloads, the first of which is this nearly 50-minute single track, never released but recorded in 2003. That puts The Man and the Biosphere roughly in the same chronological camp as Milky Way, though in many baffling instances, they couldn’t be more different. To overgeneralize, the latter is stunningly unified, while the former trades its unity for a glimpse into something like ordered chaos.

One thing this newly available miniature (in the Kayn orbit anyway!) has in common with Milky Way is the sudden sonic blanks, where everything just drops out for a second to jarring effect. In other words, certain elements of Kayn’s syntax, like the dropouts, seem to have been chronologically consistent. At the 13-minute mark, to cite the most dramatic of these blanknesses, it is as if the world disappears only to return entirely metamorphosed, as if a dream had vanished and an alternate reality emerged. That minuscule but all important silence, stripped even of reverb, is immediately preceded by the rhythmic bell tones that comprise much of what has transpired to that point. On first hearing, the bells, sometimes interspersed with children’s voices, came off as a guiding principle, a thread through the maze of sonic signifiers in play. The tolling and ringing’s sudden disappearance, as if snatched or swallowed, is more shocking than a simple jump-cut edit would have been, and it speaks to the disunity governing the rest of the piece. First, there’s the sudden drone, unearthly in its subdued beauty, hearkening back to parts of 1983’s Scanning in its open sonority. Is that high-pitched sound at 13:44 its wild transposition? If not, is it our bells moved to the highest frequencies possible? Whatever the case, we are in a landscape riddled with rupture and disjuncture rather than the holographic rooms Kayn so often constructs. Even when the bells return a few minutes later, they reel drunkenly, as unsteady as they were previously rock solid.

What may be most surprising is what happens to those bells. They are replaced by a loop involving what sounds like a toy piano. It recurs throughout in various transpositions, ending the piece on a slow fade. As the opening oceanic drones, which were revealed to be bells, have been reduced to large fragments, the bells diminish to a child’s toy. There’s something archetypal about the reduction, something deliciously cheap as nobility is replaced by the machine, and those barely audible children’s voices have their place in the larger form after all. Repeated listening reveals a different kind of unity, something multi-leveled and discursive, and it leaves me anticipating anything from the Kayn archive that might see the light of day.

Marc Medwin

#roland kayn#the man and the biosphere#reiger records reeks#marc medwin#albumreview#dusted magazine#cybernetic#electronic#experimental#modern classical

1 note

·

View note

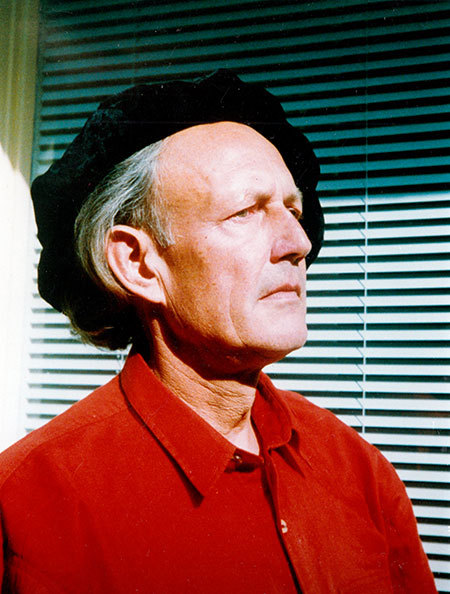

Photo

Roland Kayn - Accumulation

Reiger-records-reeks

2021

23 notes

·

View notes

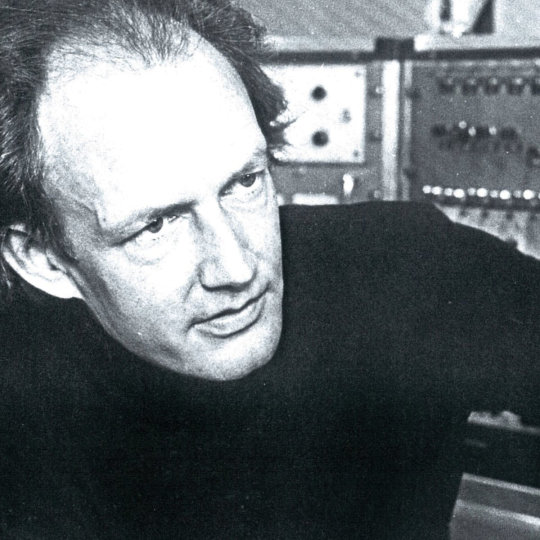

Photo

Roland Kayn - An Algorithm MA 71

Reiger-records-reeks

2021

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roland Kayn - Reversioni Comprimati

Reiger-records-reeks

2022

4 notes

·

View notes