#Ramón Acín

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Comics Read 09/28 -10/17/2024

Over this time I read Luis Buñuel and the Labyrinth of Turtles written and drawn by Fermin Solís. I am a long time Buñuel fan, so I preordered this as soon as I saw it was a thing. I try and see his movies whenever I can. For example, earlier this year (2024) made sure to get to four screening go the MoMA’s Buñuel in Mexico series earlier this year. I saw Ensayo de un crimen/ The Criminal Life of Archibald de La Cruz, Él/This Strange Passion, The Young One, and double feature of Simon del Desierto and Un chien andelou/El perro andaluz. Other than Un chien andelou. I had never seen any of them before, and they were all great. Also this was the first time that I saw Un chien andelou without any soundtrack. It usually plays with a mash up of tango and Wagner. It’s funnier with that music, more violent with out it. I think these films should be more available in the English speaking world. (In general, more of the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema should be available in the English speaking world.)

I am unfamiliar with the comic writer/artist. But I like how he does character design, the limited color palette. There is a fun mixture of dream sequences and the more reality based situations. Which is appropriate because this takes place during the making of his third film, Land Without Bread/Las Hurdes, which was a documentary after making two surreal shorts. As the comic presents, the motivation for making it is acknowledging the difference between surrealism stated political goals, and the art they actually made. The purpose of this documentary is to bring attention to a greatly impoverished area in Spain maybe making the film about it could change things their for the better.

The book doesn’t get into the reception of the film, but it should not surprise readers that it did not have that intended effect. Not just because as a documentary made by a surrealist, there are some ethically dubious decisions made. While Buñuel and his friend, Ramón Acín were Spanish, they were not from Las Hurdes and their methods seem near exploitative. Also they bring friends from France as colleagues who are just disgusted and gawking. Would you even want a film made like that to have a heroic reception? More importantly, unbeknownst to the people making the film, Spain is on the verge of a catastrophic civil war the will lead to decades of fascist military dictatorship. Early in the book Buñuel and Acín discuss some of the political unrest that will lead to the war, but not with much interest. They are much more concerned about finding a bar open in Paris during the early morning hours. In an afterwards about the four main characters it is revealed that and Acín and his wife were murdered by members of the extreme right during the war.

I bring up all this stuff about a war that doesn’t occur during this story because I find it interesting, and think it adds a pall to the debates about art. Land Without Bread/Las Hurdes isn’t one of Buñuel’s best films. While reading this I realized that I had seen it, but for some reason combined it with his previous film, L’âge d’or. For some reason, in my head Jesus showing up at a party thrown by contemporary rich people and peasants kicking a goat off a cliff were in the same film. The film didn’t help the people it was about. According to my quick look at Wikipedia, things got unsurprisingly worse under Generalissimo Franco. So why did I like this book and Buñuel generally? There is an unromantic sense of humor. Laughing at oneself while trying to still make work. The complete disinterest in respectability politics, as they can only obscure essential truths. Buñuel didn’t make another film for close to two decades. By that time he fled Spain and became a Mexican citizen. That follow up was Los Olvidados, also throwing a light on an aspect of society that people worry about how bad it makes their country look. (Unfortunately I haven’t seen it. The screening earlier this year didn’t fit in my schedule.) But that’s not what this is about or the appeal. It’s about how art might not have the desired political effect, but still worth doing if only to explore one’s self and one’s world.

#comic books#what i'm reading#comics#luis buñuel#Fermin Solís#Land Without Bread#Las Hurdes#Ramón Acín#art and politcs#surrealism#film history

0 notes

Text

90 Movies in 90 Days: Las Hurdes (1933) and Los Olvidados (1950)

Every day until March 31, 2024 I will be watching and reviewing a movie that is 90 minutes or less. Today we have another “two-fer” with two movies from director Luis Buñuel. Title: Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread) Release Date: December 1, 1933 Director: Luis Buñuel Production Company: Ramón Acín Summary/Review: After kicking of his film career with the surrealist classics Un Chien Andalou…

View On WordPress

#90 Movies in 90 Days#Crime#Documentary#Drama#Exploitation Movies#Luis Buñuel#Mexico#Movie Reviews#Movies#Poverty#Spain

0 notes

Photo

Eine animierte Graphic-Novel-Verfilmung für das Bildungsprogramm. Luis Buñuel hat mit zwei filmischen Zusammenarbeiten mit Salvador Dalí eine gewisse Bekannt- und Berüchtigkeit erlangt, jetzt wird er zwar von ein paar Pariser Avantgardisten verehrt, die allerdings immer fragen, welche Ideen seine und welche Dalís waren, dabei waren alle Ideen seine, bekommt aber kein Geld für sein nächstes Projekt, einen Dokumentarfilm über die bettelarme spanische Gegend Las Hurdes zusammen, weil der beleidigte Vatikan droht, seine Unterstützer zu exkommunizieren. Zudem hat er surreale Träume. Buñuels Freund Ramón Acín kauft ein Lotterielos und verspricht, wenn es gewinnt, den Film zu finanzieren. Surrealerweise gewinnt es, und sie begeben sich in die Extremadura, wo die Dörfer wie Labyrinthe aus Schildkröten aussehen. Großer Inzenierer, der er ist, bringt Luis es dann allerdings doch nicht fertig, bloß zu dokumentieren, teilweise unter krasser Mißachung des “No Animals Were Harmed”-Ansatzes. Das hatte man damals noch nicht so.

#Buñuel en el laberinto de las tortugas#Jorge Usón#Fernando Ramos#Film gesehen#Salvador Simó#Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan#Luis Buñuel

0 notes

Text

FENDO HISTORIA, Ana Asión, Ebardo Fernández y Josema Carrasco

FENDO HISTORIA, Ana Asión, Ebardo Fernández y Josema Carrasco

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Ramón Acín

Me acuerdo de aquel «erúdito» que en los ochenta no se atrevía a escribir que a Ramón Acín lo habían fusilado porque eso era conflictivo y echó mano del «a consecuencias de la Guerra Civil»… De aquellos polvos, el pozo negro rebosante que ha venido luego.

LOS BUENOS VECINOS DE HUESCA

«¡Ay, Ramón Acín, fusilado y fusilada su mujer por culpa de sus buenos vecinos de Huesca!» Max Aub, “La gallina…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Ramón Acín Aquilué (1888-1936) - El Agarrotado

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Želve, medvedi, lastovke in druge ptice

Za uvod nas bosta animirana cienast Luis Buñuel in kipar Ramón Acín popeljala na nadrealistično, a resnično, s spomini prežeto filmsko popotovanje po goratem predelu Španije v celovečerni animirani pustolovščini Buñuel v labirintu želv režiserja Salvadorja Simója. In to bo šele začetek.

Animateka

tokrat prinaša kar 360 animiranih kratkih in 12 celovečernih filmov, ki se bodo odvrteli v sedmih dneh. Najboljši se bodo potegovali za nagrade v treh kategorijah: program vzhodne in srednje Evrope, mladi talenti Evrope in Slonov tekmovalni program, kjer bo o zmagovalcu odlo��ala otroška žirija.

Sicer pa bo med 32 tekmovalnimi deli odločala mednarodna žirija, letos z zgledno prevlado ženskih kvot. V njej sedijo francoska umetnica Marie Paccou, tudi avtorica razstave slikofrcev v Slovenski kinoteki, priznana srbska animatorka Ana Nedeljković, umetniška direktorica dunajskega festivala Tricky Women Waltraud Grausgruber, ob njih pa še švedski avtor Jonas Odell, znan po videospotih za skupino Franz Ferdinand, in latvijski režiser Edmunds Jansons, ki je ustvaril letošnjo festivalsko podobo in bo razstavljal risbe v galeriji Kinodvora.

Animateka se začenja z biografsko avanturo, ki nas popelje v hribovito Španijo, kjer je filmar Luis Buñuel posnel dokumentarec Zemlja brez kruha. Foto arhiv Animateke

Baltik na obisku

Posebno pozornost Animateka letos posveča državam ob Baltiku, Litvi, Latviji in Estoniji, z bogato animirano zgodovino in samosvojo animacijo, ki jo zaznamujejo absurden, komičen in bizaren slog. »V široki paleti filmov najdemo preplet prvovrstne obrti in meditativnega stanja duha pa tudi podton ukvarjanja s tistim, česar ni lahko izgovoriti. Tu ne gre za žanr: filmi so lahko absurdne komedije, primeri trezne nostalgije oziroma politične alegorije, celo otroški filmi,« je v popotnico programu zapisal urednik spletnega portala Zippy Frames Vassilis Kroustallis.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Animated Surrealism.

“People who were going to the cinema were the bourgeoisie and they were not used to seeing these things. Buñuel put it on the screen. It was a big scandal.” We talk to filmmaker Salvador Simó about goat violence, winning the lottery, friendship and Surrealism.

‘Films about filmmaking’ is a beloved genre of film obsessives. A new addition to the pool is Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles, which mixes animation with original footage to explore the making of Surrealist-cinema godfather Luis Buñuel’s hard-hitting documentary short, Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread).

Based on the graphic novel of the same name by Fermin Solís, this true-story animation is directed by Spanish animator Salvador Simó, who is known for directing kids’ show Paddle Pop, and worked on the visual effects for Passengers and The Jungle Book.

Simó’s film begins just as Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or premieres to controversy. The filmmaker has had a falling out with artist Salvador Dali despite their success with Un Chien Andalou. He’s looking for his next project, when his friend Ramón Acín promises to produce Buñuel’s next film if Acín wins the lottery. Acín does win, and Buñuel travels to Las Hurdes, a poverty-stricken town in a remote region of Spain.

Las Hurdes was banned by the government of the time for its treatment of its subjects, both human and animal (Buñuel had recreated some animal abuse scenes he had read about). Writing about the film on Letterboxd, Edgar observes that Buñuel “literally becomes exactly what he condemns… Nevertheless, like a predecessor of Resnais, the auteur finds a gorgeous balance between natural beauty and the ugliness of social injustice”. Mike writes: “I see why this film was included in the 1001 Movies You Need to See Before You Die. It’s a brilliant mockumentary that cynically defies every moral expectation in order to make its point.”

We spoke to Salvador Simó on the eve of the release of Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles in US cinemas.

Why did you decide to explore the production of Las Hurdes as a film? Salvador Simó: I discovered Luis Buñuel a long time ago when I was a child. I remember my father has always been a big fan. When I was about nine, he arrived home very excited because he just saw a movie where there were people in a room but they couldn’t get out of the room [1962’s The Exterminating Angel] and I was really fascinated while he was explaining it to me, I was like “wow!”.

When I grew up a little bit more I discovered films from Buñuel, I think he was always somehow in my family in this way. But the fact of doing this film, it was actually because [producer] Manuel Cristóbal called me and showed me the comic by Fermin Solís and he was asking me “do we think we can make a movie of that?” I started reading it and while I thought ‘I do not agree with some things…’ I did think ‘we can make a movie about that’.

What would you say was the documentary’s importance in how it changed Buñuel’s career as a filmmaker from that point forward? I think it was a turning point for him. Before Las Hurdes, the surrealism that Buñuel was working on took a big influence from [painter Salvador] Dalí. It was totally based on images and things that had not really an explanation. That’s the way they were working. The town of Las Hurdes changed his way of proceeding the making of a film and of telling a story. He became more human.

You see what happened with all his films after Las Hurdes, his surrealism is more based on the human soul. The first film that he did afterwards as an author was Los Olvidados, seventeen years later, and during all that time he learned a lot. After that, all his films that made him really famous was his way to see surrealism in the way we dictate day-by-day.

What was your creative process for the surrealistic scenes? I did sketch the whole film from the beginning to the end. What we’re calling the surrealism scenes in the film [were] also a way to see into his mind, to tell part of his behavior, his feelings, and even his past. It was in this global way to tell the story of Buñuel to people that is a little bit surrealist.

We never had the intention to copy anything of his way of making film, but we had great influence from him because we’d been working on him for all these years. For this movie I felt like Buñuel and I were walking the same paths. In Las Hurdes he was trying to find his own voice and in this film it was a little bit the same for me, so it has been doubly [influenced] by him and his way to be an artist.

What led to the decision to include footage from Buñuel’s actual films rather than recreating them in animation? Because they were there. We wanted to show that what happened was real and it was really tough. If we drew that, people would believe it was part of the animation and that we made it up. The best way to see what they were seeing at the time was from the actual footage they shot in 1932.

In Spain, for many years it has been a great controversy about what Buñuel did with his documentary—whether it was real or if he made it up—but what people don’t know is that Buñuel based [it] on an existing book he read by French-Hispanic Maurice Legendre [entitled Las Jurdes: étude de géographie humaine, English translation: Las Hurdes: Study of Human Geography, published in 1927]. He was there about ten years before and he wrote 300 to 400 pages describing what was the situation in Las Hurdes.

In that book, what Legendre was writing about is worse than what Buñuel did. What Buñuel was trying to show [was] what was happening in that place, to try to change the world. You have to think that in that time, many of the surrealists, they were trying to change the world and make it better. This was Buñuel’s way to do it. He was denouncing what was happening.

Of course the government at the time covered up all of that because they didn’t want to accept that was real, but people were actually dying and starving and they were [contracting] diseases. It was terrible. Buñuel put it on the screen when cinema was starting. People who were going to the cinema were the bourgeoisie and they were not used to seeing these things. They were used to seeing stories of high society and not used to seeing what Buñuel had to show them. It was a big scandal and they forbid this film for many years.

This film acts more as a tribute to [Buñuel’s producer and friend] Ramón Acín than to the filmmaker himself, and delivers Acín the credit he deserves. At what point in your research did you decide to switch the focus to him? When we were working on the movie I remember at the beginning thinking I need to make the end of the movie more inspiring. Then we talked with Ian Gibson, the biographer of Luis Buñuel, and he told us the story of Ramón Acín. At the beginning he just was kind of a character we were using in a way to show some part of the characteristics of Buñuel at the time.

When he told us the story we thought ‘maybe it’s a story of friendship’. He actually win the lottery after he told him “no worries, if I win the lottery I will pay for the film” and four weeks later he wins the lottery and keeps his word. I thought ‘wow, that’s amazing. He keeps his word!’. I would be surprised if anyone would nowadays.

At the end, it’s not only a tribute to Ramón Acín and Buñuel, it’s also a tribute to the good people that [are] all around the world. We’re too used to hearing about the bad people on the news, but actually we’re surrounded by very amazing people and I think the film is also a tribute to them. Somehow with Ramon, it was the good man who represented that in the film.

Acín acted as the voice of morality regarding the treatment of animals, which is what made the film controversial at the time. Did you use him in that sense to comment on Buñuel’s actions? Not exactly, to be honest, no. I know the treatment of animals is tough, and I don’t agree with it at all, but I think we need to see this. That was what was happening in 1932. We cannot be blind to that. If we just censor that, we will not be honest about what was happening in that time. Society had different rules and a totally different mentality.

At that time talking about animal rights is like talking science fiction. Why should we have to hide that, because we don’t like it now? I think we have to show it because that’s what happened, whether we like it or not. You’d be surprised at how many countries in the world keep doing these things to animals. Even in Spain, the bullfighting still happens.

Buñuel was always pushing the lines for the people and making them actually jump off their chair. That’s a little bit of what we wanted to do with this film, to make people jump off their chairs too.

We like to ask filmmakers about the film made them want to get into making movies. Which film was it for you? Actually for me, it was not a film, it was my daughter. I’ve been working 30 years in animation as an animator. Then when my daughter was born I wanted to make more short films about the things that she was interested in. I wanted to tell the stories to her.

Which is your favorite Buñuel film? A lot of them are great, but Los Olvidados is an explosion of Buñuel for me.

‘Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles’ is in US cinemas now.

#luis bunuel#salvador simo#spanish film#surrealism#surrealist cinema#las hurdos#los olvidados#letterboxd

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Bunuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles (2019)

In a stranger-than-fiction tale befitting the master surrealist filmmaker, Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles tells the true story of how Buñuel made his second movie. Paris, 1930. Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel are main figures of the Surrealist movement, but Buñuel is left penniless after a scandal surrounding his first film L’Age d’Or. However, his good friend, the sculptor Ramón Acín, buys a lottery ticket with the promise that, if he wins, he will pay for his next film. Incredibly, luck is on their side, the ticket is a winner and so they set out to make the movie. Both a buddy adventure and fascinating episode of cinematic history, Buñuel and the Labyrinth of the Turtles utilizes sensitive performances as well as excerpts of Buñuel’s own footage from the production, to present a deeply affecting and humanistic portrait of an artist hunting for his purpose.

Directed by: Salvador Simo

Release date: TBD

#Bunuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles#Luis Bunuel#Salvador Dali#Salvador Simo#Movie#Movie Trailers#Film#Animated Film#Foreign Language Film

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ramón Acín y la generación perdida

Antonio Cuesta

Para el lector actual, el primer tercio del siglo XX es un continente por explorar en la literatura española. Nunca antes hubo tanto talento, tantas ganas de contar cosas y tantas novelas de mérito, de las que solo unas pocas son fáciles de encontrar a día de hoy: "Luces de bohemia" o "Tirano Banderas" de Valle-Inclán, "Imán" de Ramón J. Sénder, "Niebla" de Miguel de Unamuno...

Otras sucumbieron ante la avalancha de obras de sus prolíficos autores, quedando sepultadas por otras más mediocres que su creador fue arrojando la imprenta en años posteriores. Es el caso de "El Intruso" de Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, o "Siete domingos rojos" del ya citado Sénder. Pero muchas más, me atrevería a decir que la mayoría, se perdieron para siempre y con ella una generación entera de periodistas, narradores y cronistas, fulminada por la guerra civil y el franquismo y de la que nunca más se volvió a hablar.

Unas pocas, realmente pocas, han llegado a nuestros días gracias al acierto de pequeñas editoriales, que han sabido leer entre miles de páginas del olvido, de otro tiempo, pero con la misma clave: la buena literatura es universal en el tiempo y en el espacio.

Estoy pensando en "Tea rooms. Mujeres obreras" de Luisa Carnés, la obra completa de Manuel Chávez Nogales, o "Los vencedores" de Manuel Ciges Aparicio. Pero hay más, decenas de creadores, narradoras o ensayistas, asesinados o que acabaron sus días en el exilio, fueron eliminados de la memoria. La Transición, como no se cansó de denunciar Rafael Chirbes, no solo fue un borrón y cuenta nueva en otras cuestiones sociales o políticas. También dejó "atado y bien atado" el canon literario de los años que vendrían después.

Voy a citar solo tres de estos autores con quien, por diversas razones, me he cruzado en los últimos tiempos.

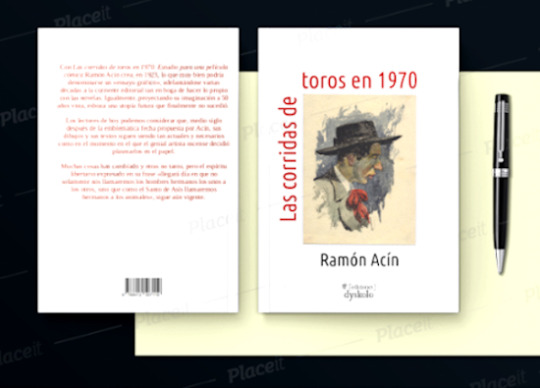

¿Quién recuerda a Ramón Acín? Al menos él cuenta con una fundación, cuyo objetivo principal es "el de recordar, preservar y difundir la obra artística y la memoria de Ramón Acín Aquilué". Pedagogo, artista plástico, escritor, emprendedor y anarquista, destacó tanto en su calidad artística como en el compromiso político que demostró en las diversas actividades que desarrolló. Como docente, ejerció una notable labor pedagógica relacionada con la Institución Libre de Enseñanza; como escritor, fundó algunos rotativos y colaboró con sus irónicas ilustraciones y críticos artículos en importantes diarios —El Sol de Madrid, Diario de Huesca—, incluso publicó el memorable ensayo: Las corridas de toros en 1970. Estudio para una película cómica, que he tenido el inmenso placer de editar y que dentro de unos días será presentado en la Fira Literal de Barcelona. Por último, como político y sindicalista afiliado a la Confederación Nacional de Trabajadores (CNT), defendió el sistema democrático y los intereses altoaragoneses hasta el punto de ser fusilado el 6 de agosto de 1936.

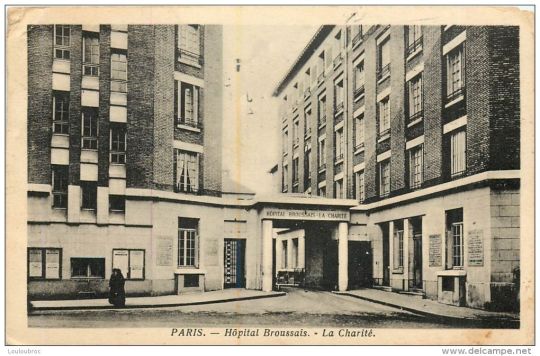

Amigo desde la infancia y compañero de militancia anarcosindicalista fue Felipe Alaiz, al que el poeta y ensayista Francisco Carrasquer definió como "el primer escritor anarquista". Alaiz escribió centenares de crónicas periodísticas, novelas breves, folletos pedagógicos, decenas de ensayos divulgativos y una sola novela "Quinet". Una producción enorme, que abarcaba un sinnúmero de temas, y un texto único, original, con tintes vanguardistas, y que sin embargo no figura en los artículos sobre la vanguardia española de los años 20 del pasado siglo. Una novela escrita durante su estancia en la cárcel por delitos de opinión en 1924, y publicada ese año en Barcelona. "Quinet" es una de las mejores novelas de su época, y pese a ello absolutamente desconocida en la actualidad. Con la victoria de las tropas franquistas, Alaiz pudo abandonar España en un tortuoso periplo que le llevó a un campo de concentración del sur francés, junto a decenas de miles de republicanos, y pasó los últimos 20 años de su vida en Francia. Murió el 18 de abril de 1959, solo y pobre, en el Hospital Broussais de París.

Hace una semanas familiares de Antonio Otero Seco realizaron en París la presentación de "Vie entre parenthèses" (Vida entre paréntesis), un libro inédito de memorias que recuerda desde la victoria franquista, su encarcelamiento y su condena a muerte, hasta su salida finalmente de prisión en octubre de 1941. Durante los siguientes años Otero consigue sobrevivir con sucesivos empleos y vuelve a escribir bajo seudónimo textos históricos y tres obras teatrales en verso, además de artículos en un periódico clandestino (Democracia). Controlado y detenido repetidas veces por la policía del régimen por su militancia en una red clandestina de resistencia antifranquista se ve obligado a huir y, el 10 de marzo de 1947, cruza la frontera francesa para no volver nunca más a España.

En uno de sus poemas, de titulo Exilio, Otero dice:

Moriremos dos veces, como muere la luna que se levanta muerta y se acuesta menguante [...] Moriremos de ausencia, como mueren las madres que un día nos despidieron clavadas en la tierra, como árboles de acero, seguras de que nunca podrán darnos un beso ni cerrarnos los ojos.

En un artículo, Miguel Ángel Lama se preguntaba cómo era posible que "la figura de un intelectual comprometido, de un inquieto periodista, de un crítico literario fino y atento a la actualidad editorial de un país que había tenido que abandonar casi treinta años atrás, fuese tan desconocida en España y en Extremadura", de donde era originario.

Otero Seco fue, en efecto, un intelectual íntegro, artífice de la última entrevista que concedió Federico García Lorca, el 3 de julio de 1936, y autor junto a Elías Palma de "Gavroche en el parapeto", la primera novela de la guerra publicada en la España republicana, y académico durante su exilio francés en la universidad de Rennes, donde formó a varios hispanistas y a filólogos en literatura española gracias también a numerosos artículos que escribió para la prensa de ese país.

Debieron pasar 51 años de su muerte, ocurrida en 1970, para que una editorial española publicara un libro con su poesía completa, "Poemas de ausencia y lejanía", y no será hasta 2023 cuando podamos leer su "Vida entre paréntesis", de acuerdo a los planes de la editorial sevillana Libros de La Herida.

La literatura no solo son novedades, aunque la continua avalancha de estas sea lo que dispara los beneficios de los grandes grupos editoriales. Muchos títulos, muchas ventas a un ritmo frenético, y más libros.

Lo importante de un libro, de un buen libro, es que permita encontrar al lector "en una escena leída un modelo ético, un modelo de conducta, la forma pura de la experiencia", al menos eso decía Ricardo Piglia. Nada nuevo, lo mismo que ofrecía la mitología griega o las fábulas medievales, referentes que a día de hoy continúan siendo válidos.

Las novelas no pueden dejar de estar inmersas en la sociedad de su momento y alumbrase de las luces y sombras que la definen. Pero por el hecho de ser universales establecen un diálogo con los lectores de cualquier época.

Antonio Cuesta es periodista y editor de Dyskolo

0 notes

Photo

Dessin original de Ramón Acín Aquilué, prison Huesca, 1933. Une vie d’inspiration, symbole d’amour de vivre, d’émancipation et de liberté. Tatoué sur mon propre genoux. Pour ne pas oublier. A jamais, ne pas perdre espoir. LA LUTTE CONTINUE ! #tattoo #tatouage #art #ink #freedom #bird #cage #darkart #darkartist #carotideae #life #illustrativetattoo #tattooart #carotide #tttism #frenchtattoo #anarchism #punk #love #nevergiveup (à France) https://www.instagram.com/p/CY4R7mDgI1U/?utm_medium=tumblr

#tattoo#tatouage#art#ink#freedom#bird#cage#darkart#darkartist#carotideae#life#illustrativetattoo#tattooart#carotide#tttism#frenchtattoo#anarchism#punk#love#nevergiveup

0 notes

Text

Tal día como 30 de agosto de hace 133 años nació Ramón Arsenio Acín Aquilué (1888-1936). Nació el 30 de agosto de 1888 en Huesca, Aragón, (España) y falleció el 6 de agosto de 1936 en Huesca, Aragón, (España). Fue un pintor, escultor, periodista y pedagogo español, de ideología anarquista.

0 notes

Link

El próximo 6 de agosto se cumplen 84 años del cruel asesinato de Ramón Acín Aquilué. Rememorando una acción del anarquista y guerrillero antifascista, Francisco Ponzán, alumno de Acín, el Ateneo Paco Ponzán -asociación de memoria histórica libertaria aragonesa de reciente creación, impulsada por profesores e historiadores- anima a la gente a que, ese día, luzcan el dibujo de la pajarita, la obra más conocida de Acín. Mezclando lo analógico y lo virtual, "animamos a ponerse una pajarita de papel en la solapa o en la terraza de un bar, o en la mesa de trabajo, pero también a poner la imagen en los perfiles de las redes sociales, de WhatsApp a Facebook, Twitter… o a llevar lápices de colores a su tumba en el cementerio de Uesca, para conseguir que la crueldad del fascismo no logre borrar su recuerdo". Anarquista, maestro, periodista y artista, Ramón Acín nació en Uesca un 30 de agosto de 1888. Fue asesinado a los 47 años de edad, el 6 de agosto de 1936, pocos días después del golpe de estado militar contra la República. Su vida en la capital altoaragonesa transcurre entre sus clases, su dedicación al arte y su militancia en la CNT que le costó cárcel, exilio y finalmente su muer

0 notes

Text

Sábado 18 de diciembre

Sábado 18 de diciembre

Esta mañana se ha presentado “Muixons”, resultado del II Concurso “Braulio Foz” de cómic y del buen hacer de la Dirección General de Política Lingüística del Gobierno de Aragón y Daniel Viñuales GP Ediciones. Un proyecto maravilloso en el que he participado formando equipo con mi adorada Ana Asión y con el estupendo traductor Ebardo Eduardo Fernández Herrero. Muitas grazias compañers!

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles

With the Jean-Luc Godard portrait Redoubtable and Peter Greenaway’s Eisenstein in Guanajuato still lingering in the memory, and a Rainer Werner Fassbinder biopic on its way, there seems to be growing interest in fiction features chronicling the early years of some of Europe‘s most influential filmmakers. As an animation, Salvador Simó’s Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles – about the father of cinematic surrealism, Luis Buñuel – immediately stands out from the pack on form alone. Following the success of 1929’s surreal short Un Chien Andalou (where he was overshadowed by collaborator Salvador Dalí) and the controversy surrounding its follow-up, L’Age d’Or, Buñuel decided to take a comparative left turn by making a pseudo-documentary in a remote region of Spain as both his career and the country entered a turbulent period.

Las Hurdes was the location of the resulting 1933 short of the same name – also known as Land Without Bread – in which Buñuel depicts the intense poverty of the area’s occupants in a manner like a surrealist riff on a traditional travelogue. How he approaches and manipulates his participants, from orphans to animals, becomes the main focus of Simó’s movie. Buñuel’s film was funded by his lottery-winning anarchist friend, Ramón Acín, and their relationship informs the gut punch of the short’s later life after completion, once the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936.

Land Without Bread blurred fiction and documentary, and the most compelling element of Simó’s film is how it merges various media. Itself based on a graphic novel by Fermín Solís, the 2D animation surprises in featuring regular inserts of live-action footage from the early Buñuel efforts it documents. If this sentimental biopic doesn’t necessarily capture the radical bite of its transgressive subject, it at least honours his formal unpredictability.

The post Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles appeared first on Little White Lies.

source https://lwlies.com/reviews/bunuel-in-the-labyrinth-of-the-turtles/

0 notes