#Railroad workers United

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Railroad Workers United (RWU) has received a remarkable outpouring of support and solidarity as our struggle for a fair contract has caught national attention, and the daily realities of our working conditions have reached the hearts and minds of our communities. Railroaders, friends, and allies are joining our membership organization, subscribing to our newsletter service, and asking how they can help.

Despite actions by Congress and the Biden Administration, we intend to continue to organize for our dignity and job quality, and fight exploitation by Class I rail carrier billionaires.

We are a group of fighting railroaders and we fight for all workers.

Amid this season of giving, RWU humbly asks you to help propel our campaigns and capacity building forward. Your donation will support:

Expanding our campaign for public ownership of the railroads

Fighting to consolidate the railroad craft unions to achieve one strong and unified voice at the next round of bargaining — organizing for which begins today!

Funding research, development, and labor education

Building our staff and administrative capacity to meet the needs of a growing membership, and to support member organizing

By giving to Railroad Workers United, you become a steward of fairness and decency on the railroads, which are so crucial to the supply chain. Join our struggle and please donate today. Thank you!

Donate Here - Help Build the Movement!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

An alliance of unionized rail workers on Tuesday demanded that the U.S. Senate reject President Joe Biden's nomination of former Trump administration official Ronald Batory to serve on the board of Amtrak, the nation's passenger rail company.

In a statement, Railroad Workers United (RWU) said Batory's tenure as head of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) under former President Donald Trump "was marked by policies favoring 'operational efficiencies' (i.e., corporate profits) over the safety and well-being of rail workers and the public."

"Notably, under his leadership, FRA attempted to override state laws mandating two-person train crews, promoting instead the adoption of single-person crews nationally," said RWU. "This push was part of a broader deregulation agenda, ostensibly aimed at reducing operational costs for the monopoly of carriers at the potential expense of safety and labor protections."

"Moreover, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Mr. Batory oversaw the FRA's issuance of emergency waivers that suspended numerous long-standing safety regulations," the group added. "These waivers were granted rapidly with limited opportunity for stakeholder input, raising significant concerns among rail labor organizations about their sweeping breadth and the lack of stringent oversight, which could compromise rail safety and worker security."

The statement urges rail workers across the country to contact their senators and demand they block Batory's nomination.

"His record clearly demonstrates a prioritization of carrier profits over the safety of rail workers and the traveling public," said RWU, calling the Senate to "derail Batory."

0 notes

Text

i think it should be legal for unions to take hostages

#executing one UC regent a day until my demands are met#railroad workers united if you want to put a bag over any politician’s head and put them in a warehouse i’ll look the other way just saying

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: OP includes screenshot of text from the included link. Text reads:

“This is a big deal, said Railroad Department Director Al Russo, because the paid-sick-days issue, which nearly caused a nationwide shutdown of freight rail just before Christmas, had consistently been rejected by the carriers. It was not part of last December’s congressionally implemented update of the national collective bargaining agreement between the freight lines and the IBEW and 11 other railroad-related unions.

‘We’re thankful that the Biden administration played the long game on sick days and stuck with us for months after Congress imposed our updated national agreement,’ Russo said. ‘Without making a big show of it, Joe Biden and members of his administration in the Transportation and Labor departments have been working continuously to get guaranteed paid sick days for all railroad workers.

‘We know that many of our members weren’t happy with our original agreement,’ Russo said, ‘but through it all, we had faith that our friends in the White House and Congress would keep up the pressure on our railroad employers to get us the sick day benefits we deserve. Until we negotiated these new individual agreements with these carriers, an IBEW member who called out sick was not compensated.’” /id]

"We're thankful that the Biden administration played the long game on sick days and stuck with us for months after Congress imposed our updated national agreement. Without making a big show of it, Joe Biden and members of his administration in the Transportation and Labor departments have been working continuously to get guaranteed paid sick days for all railroad workers."

Yeah, I AM gonna point this out, and be blunt and annoying about it: remember how the Online Leftists have spent MONTHS screaming about Biden Selling Out The Working Class and heaping vitriol on him for proposing the compromise agreement to Congress that stopped the rail strike, but didn't include sick days, and this was the Biggest Betrayal Ever To Betrayal? And showed that he was terrible and a corporate sellout and anti-labor and whatever else?

Well, guess what: now the rail workers have paid sick days! Biden and the Department of Labor/Transportation worked nonstop to get it done, didn't brag about it or blather on endlessly, and then got it done! Because it turns out that it was better to take the partial agreement, keep things moving, and continue to work in good faith and make progress, thus resulting in what they wanted without just blowing everything up and calling that a good plan! Shocking!

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's nationalize rail!

0 notes

Text

"The vast majority of white shopmen did strike. That there was not a total walkout was due to local circumstances. On the Great Northern Railroad, the total number of strikers reached 93 percent, but in some locales shopmen continued to work. For example, in St. Cloud, Minnesota, 49 percent of the men remained at work in the shop and 40 percent in the roundhouse. Other weak points included the roundhouses of Clancy, Montana; Rugby, North Dakota; and Anacortes, Washington. 16 In California, a local strike official reported that "Fresno and San Jose did not respond as they should have done." In the East, a local strike leader reported from the Baltimore and Ohio system federation that "The majority of the men that are in are from the Mt. Clara shop at Baltimore."

The striking shopmen faced important obstacles in presenting a united front. The support of African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Asians was an important key to the strikers' attempts to win the battle. While the majority of white shopmen struck on July 1, for minorities the question was complicated by the endemic racism of the shopcrafts. Because such workers were regularly rejected by shopcraft unions and prevented from moving up to skilled positions, their potential as a divisive force became readily apparent. Indeed, in reaction to this history of discrimination, some minorities scabbed. In Alabama large numbers of blacks continued to work. J. W. West, a carmen strike leader on the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, reported that black shopmen remained at work in Birmingham and Mobile. In Winslow, Arizona, the bulk of the scab workforce included "some forty odd Indian carmen and Japanese machinists."

Strikebreaking by Native Americans in some cases was tied to longstanding reciprocal relations. The Laguna Pueblo of New Mexico, for example, had long been connected to the Santa Fe Railroad. Since 1880, when the Laguna Pueblo had signed a "Gentlemen's Agreement of Friendship," they were guaranteed railroad jobs throughout the New Mexico territory. In 1922, Santa Fe management asked the Launa Pueblo workers to travel to Richmond, California, and take the places of the striking shopmen. The Laguna Pueblo workers agreed. One later testified they'd informed the company: "you always call us [when you] need help, we'll help you, you know."

While some did join the scab forces, minorities in large numbers actively supported the strike. African American shopmen established strong strike organizations in North Carolina and Louisiana. In Algiers, Louisiana, where blacks made up the majority of the shopcrafts, all came out led by a "negro president of the Algiers Blacksmith Helpers Auxiliary," who was described as an "organizer of merit and a forceful speaker." A union report from El Paso, Texas, confirmed that "ninety per cent" of the black shopmen "are with us." White strikers in some locales actively encouraged black shopmen to join the fight. At Richmond, Virginia, white strike leaders addressed the meetings of black helpers and laborers. T. J. Garvey, a boilermaker leader on the Southern Railroad, explained to one meeting that the strike would be "beneficial to the colored as well as the white [shopmen]." To further encourage the black strikers to hold fast, Garvey spelled out a future of mutual cooperation: "we should co-operate with one another and get closer together in the future than we have been in the past." A similar promise was given black strikers at Pensacola, Florida. Local strike leader G. H. Waugh, although recognizing that the African American strikers were "not organized," promised that "when the Whites go back at Pensacola, the Blacks [will] go [back] with them." But even when strikers courted black support, it was all too clear to the recipients of their sudden solicitude that their newfound acceptance was purely opportunistic. Thus, declared a white North Carolina unionist, African American helpers "could easily fill our places," and "they are a great help to us as pickets."

Shopmen of Japanese origin also solidly supported the strike. Japanese in Sparks, Nevada, "assured" the local organization that "would not return to work until the strike was settled." In Sacramento, California shopmen, a strike bulletin reported, "The Japs are with the strikers 100 percent and their secretary goes with the boys when soliciting donations from the Japs." Equally supportive were shopmen of Mexican origin. Not only did most of the Mexican American shopmen stay out on strike, they engaged in strategic picket duty on the U.S.-Mexican border. Up until July 22, these pickets managed to stop "at least sixteen hundred men from arriving in the United States to perform work on the railroads." At El Paso, Texas, Mexican Americans took the lead on the picket line. One Anglo machinist striker unknowingly, and laced with racist sentiment, detailed the commitment exhibited by Mexican American strikers to a military intelligence informant:

He says the Americans were willing to do the leading in the walk-out, but that they were shirking their duty on the picket line by leaving that responsibility altogether to the Mexicans, whom the strike leaders should be wary about trusting.

The Mexican American strikers endured not just disparate picket duty and racial stereotyping but also pressure from merchants to pay bills. One striker explained on July 21 that merchants spread propaganda that the strike was lost and that the Mexican Americans should return to work because of mounting bills. The strikers resisted this coercion; the informant insisted that the "Mexicans [were holding] together and that they will remain loyal to the union." Pressure from merchants on this group of workers was particularly felt due to their semiskilled and unskilled status. A machinist helper known only as Marquez claimed they had "nothing" saved when the strike began and that "many of the striker's wives are working now.' These wives experienced some difficulty in finding work "as many of rgw homes which formerly employed Mexican help have also been affected by the strike.' Thus the whole community had tightened its collective financial belts.

Remarkable in their championing of a conflict led and controlled by whites, minorities in large numbers stood on the picket lines and listened to speeches that applauded their "new-found" virtues as striking "brothers" or at least distant cousins. Sterling Spero and Abram Harris noted that "organized" "Negro helpers" went out on strike in 1922, and "stayed out as long the while mechanics. For the most part, this observation is correct. Minority shopmen's decision to strike mirrored that of whites. Like their white counterparts, some were encouraged by local circumstances to scab, but most joined the battle, recognizing a fundamental kinship. As Eric Arneson's and Joe Trotter's work with waterfront workers and miners has shown, occupational segregation did not preclude joint action when framed against a backdrop of fighting a common enemy."

- Colin J. Davis, Power at Odds: The 1922 National Railroad Shopmen’s Strike. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997. p. 67-71.

#strike#strike violence#strikebreaking#scabs#railway workers#railroad shopmen#union men#american federation of labor#railway capitalism#working class struggle#united states history#academic quote#reading 2024#racism in america#japanese americans#mexican americans#african americans#white america

0 notes

Text

Labor Wars in the U.S.

— The Mine Wars | Timeline | NOVA—PBS

After the Civil War, the United States entered a new phase of industrialization. Railroad magnates began to consolidate and expand railroad lines around the country. Factories needed raw material to power their increasingly mechanized production lines. Andrew Carnegie adopted ideas about vertical integration -- owning each stage of the steelmaking process so that he might control the quality and profit from start to finish. Both U.S.-born and immigrants from all over the world took dangerous jobs for low pay.

As the pace of industrialization quickened, and profits accumulated in the hands of a few, some workers began to organize and advocate for unionization. The workers wanted more safety regulations, better wages, fewer hours, and freedom of speech and assembly. But most companies vigorously opposed the union, arguing for the right to control their private property, and to conduct business without intervention. Industrialists hired guards to maintain surveillance over the workers, and they blacklisted known unionists. Learn more about events from the West Virginia Mine Wars within a national context during a period that was punctuated by violent struggle between labor and management.

Martinsburg, WV, July 16, 1877, PD

December 4, 1874

Mine operators in Pennsylvania reduce wages, and 10,000 miners go out on strike. The Molly Maguires, a group of mostly Irish miners, plan attacks and use violence against the operators and foremen. Twenty of the Molly Maguires will be sentenced to death by hanging.

July 14, 1877

The Great Railroad Strike begins in Martinsburg, West Virginia when the Baltimore & Ohio railroad company reduces wages for the second time that year. The strike spreads to other states, and state militias are mobilized, resulting in several bloody clashes. At least 10 workers die in Cumberland, Maryland.

May 4, 1886

A day after a union action in support of the eight-hour workday results in several casualties, labor leaders and strikers gather in Chicago, Illinois to protest police brutality. A bomb is thrown at policemen trying to break up the rally in Haymarket Square, creating chaos that results in the deaths of seven policemen and four workers. The clash is known as the Haymarket Affair.

January 25, 1890

The Knights of Labor Trade Assembly No. 135 and the National Progressive Miners Union combine to create the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). The goal of the new union is to develop mine safety, to provide miners with collective bargaining power, and to decrease miners' dependence on the mine owners.

Striker hides behind a shield during the Homestead Strike, PD

July 6, 1892

Steelworkers on strike at the Homestead Steel Works in Homestead, Pennsylvania fire on Pinkerton guards hired to keep order by general manager Henry Clay Frick. A Pinkerton Guard named John W. Holway later recalls, "...there were cracks of rifles, and our men replied with a regular fusillade. It kept up for ten minutes, bullets flying around as thick as hail, and men coming in shot and covered with blood." The governor of Pennsylvania orders that state militia intervene and 8,500 National Guard arrive. Known as the Homestead Strike, the action ends four months later.

July 4, 1894

U.S. Army soldiers intervene in the Pullman Strike. Two months earlier, factory workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company owned by George Pullman walked out in protest of a wage cut, and their strike disrupts the nation’s railway system and mail delivery. After President Grover Cleveland orders federal troops to Chicago, Illinois, the strike ends, and the trains start moving again.

September 10, 1897

In Lattimer, Pennsylvania, 300 to 400 striking coal miners march to demonstrate support of the UMWA. Police under the direction of Luzerne County Sheriff James F. Martin order demonstrators to disperse. The march continues, and the police open fire, killing 19 miners. It is known as the Lattimer Massacre.

October 12, 1898

When the Chicago-Virden Coal Company imports replacement workers during a strike at their mine in Virden, Illinois, the UMWA miners arm themselves with hunting rifles, pistols and shotguns and attack the train carrying them. Both miners and guards suffer numerous casualties in the ensuing Battle of Virden.

May 9, 1900

More than 3,000 Saint Louis Transit Company workers go on strike in St. Louis, Missouri in an attempt to receive recognition for the Amalgamated Street Railway Employees of America. On June 10, 1900, three transit workers are killed when a group of wealthy citizens fire upon them. The strike lasts until September, after the deaths of 14 people.

May 12, 1902

Miners in eastern Pennsylvania strike for shorter workdays, higher wages, and recognition of the UMWA. President Theodore Roosevelt threatens to take over the mines with militia, forcing the unwilling operators to negotiate. The Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902 ends with a 10% increase in pay for most miners.

June 1902

West Virginia coal miners strike, both in sympathy for the miners in Pennsylvania and with the stated goal of achieving union recognition in West Virginia.

Strikers facing off with militia in Lawrence, MA, PD

January 1, 1912

A government-mandated reduction of the workweek goes into effect in Lawrence, Massachusetts, resulting in pay cuts at textile mills. In response to the decrease in wages, textile workers go out on strike. Soon after, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) arrives to organize and lead the strike, and the mayor orders that a local militia patrol the streets. Local officers turn fire hoses on the workers. After two months, mill owners settle the strike, granting substantial pay increases.

April 18, 1912

In southern West Virginia, the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike begins in Kanawha County, just 30 miles from the state capital of Charleston. Miners demand that their wages match those earned by unionized miners nationally. Mine owners hire the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to break the strike. Violence erupts, and by September, Governor William Glasscock declares martial law. It is not until July 1913, after the violent deaths of more than 50 people, that the last miners will lay down their arms.

April 20, 1914

The Colorado National Guard and guards from the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company attack a tent colony in Ludlow, Colorado housing 1,200 coal miners striking for union recognition. More than 20 people, including two women and 11 children, are killed in what would come to be known as "The Ludlow Massace."

January 1, 1917

Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney assume official duties as executive officers of UMWA District 17 in Charleston, West Virginia. Keeney began working in the mines as a child but was inspired by Mother Jones to educate himself and become a labor leader. He becomes one of the key leaders of the miners throughout the Mine Wars.

April 6, 1917

Congress declares war on the German Empire, officially bringing the U.S. into World War I. Needing fuel for military factories and warships, the federal government assumes de facto control of the coal industry, allowing many unorganized miners to unionize. Coal production and consumption soars.

November 7, 1917

Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks seize power in Russia. This political change causes some Americans to fear that unionization efforts are a step forward along the road to communist revolution.

February 1919

A "general strike" is called in Seattle, Washington to advocate for the role of organized labor. Catalyzed by wage grievances of shipyard workers in the city's prominent port, 65,000 workers walk out for five days. The strike is nonviolent, but plays into the Red Scare of the time.

September 9, 1919

Police officers in Boston, Massachusetts strike for better working conditions, higher wages, and recognition of their union, and around three quarters of the police department fails to report for work. The police department fires the strikers and recruits a new force.

October 6, 1919

The U.S. Army takes control of Gary, Indiana, and martial law is declared after steelworkers clash with police. The steelworkers are on strike to secure the right to hold union meetings. Although 365,000 steelworkers participate nationwide, the Great Steel Strike of 1919 is defeated.

Miners line up for strike relief in Matewan, May 1920, Coutesy: WV State Archives, Coal Life Collection

May 19, 1920

A contingent of detectives from the Baldwin-Felts agency arrive in Matewan, West Virginia to evict striking coal miners. After several evictions, Mayor Cabell Testerman and Chief of Police Sid Hatfield confront the detectives and attempt to arrest them. A shootout erupts, leaving the mayor, two miners, and seven Baldwin-Felts agents dead. The shootout is known as the Battle of Matewan or alternately, the Matewan Massacre. Sid Hatfield is later tried and acquitted for murder, causing celebration among miners who see Hatfield as their champion.

July 4, 1920

Four men are shot in a battle between union miners and sheriffs in McDowell County, West Virginia. The violence is part of an ongoing struggle for recognition of the UMWA in Southern West Virginia.

May 19, 1921

Following the "Three Days Battle," during which hundreds of coal miners attack coal mines along the Tug River in Mingo County, West Virginia, Governor Ephraim Morgan declares martial law. He places Thomas Davis, a veteran of the Spanish American War and WWI, in charge of the state police, a battalion of 800 "special police," and a 250-man "vigilance committee." Davis and his men imprison several miners without charges.

August 26, 1921

West Virginia miners prepare to march toward Mingo County to assist men imprisoned under martial law there. U.S. General Harry Bandholtz meets with local UMWA leaders Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney, warning them that they will be held personally responsible for unlawful actions of UMWA members, and if the miners do not stop their march they will be "snuffed out." Frank Keeney gives a speech to a crowd of armed miners gathered in Madison, West Virginia and the miners agree to disband, but rumors of atrocities committed by a county sheriff named Don Chafin soon reignite the conflict and send the miners marching toward Mingo County again. To reach Mingo County, they will attempt to pass through Logan County where Don Chafin, his men, and the West Virginia State Police oppose the marching miners.

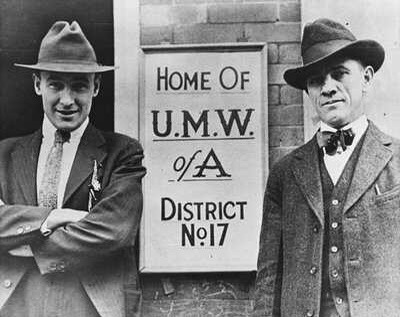

Fred Mooney (left) and Frank Keeney (right), Courtesy: WV State Archives, Coal Life Collection

August 30, 1921

President Warren Harding issues a proclamation ordering the marching miners and Logan County defenders to disperse by noon on September 1. Leaflets issuing the proclamation are dropped on both sides by airplanes. Neither side complies. Fighting between armed miners and the Logan County deputies and defenders ensues.

September 2, 1921

U.S. Army troops, requested by General Bandholtz, arrive in West Virginia and are deployed the following day. With both sides anticipating the arrival of the troops, hostilities cease and the battle is over. The number of lives lost is unknown, but is estimated to be at least 16.

April 25, 1922

Bill Blizzard, the de facto leader of the miners at Blair Mountain, goes on trial for treason against West Virginia in the same courthouse in Charles Town, West Virginia where John Brown had been sentenced to death in 1859. He is acquitted on May 27, 1922.

June 16, 1924

At a meeting with John L. Lewis and the national leadership of the UMWA, Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney are forced to resign. Union membership declines throughout the remainder of the decade.

March 23, 1932

President Hebert Hoover signs the Norris-LaGuardia Act into law. The Act outlaws "yellow-dog contracts" which forced workers to agree not to join a union as a condition of their employment. It also establishes that workers are allowed to form labor unions without employer interference and prohibits federal courts from issuing injunctions against non-violent labor disputes. Republican Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska and Republican Representative Fiorello H. La Guardia of New York sponsored the Act.

The Norris-LaGuardia Act sets the stage for further labor reform legislation, such as the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, or Wagner Act, which will outline the fundamental rights and powers held by unions and establish penalties for violating those rights.

June 16, 1933

Newly-elected President franklin D. Roosevelt signs the National Industrial Recovery Act, granting industrial workers the right to join a union. As a result, the UMWA sweeps through West Virginia, including the previously unorganized southern coalfields.

January 31, 1936

A series of sit-down strikes begins at a Goodyear Tire plant in Akron, Ohio when workers sit down at their usual workstations. Management is reluctant to attack the workers for fear of damaging company property.

The Chicago Memorial Day Incident, Courtesy: National Archives

May 30, 1937

Workers at the Republic Steel Plant in Chicago, Illinois protest the company officials’ refusal to sign a union contract. When the picketers refuse to disperse, members of the Chicago Police Department deploy tear gas and shoot and kill 10 demonstrators on the picket line. The event is coined the Memorial Day Massacre.

January 22, 1941

A strike begins at the Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company plant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The plant has manufacturing contracts with the Navy and the work stoppage hampers national defense production.

On April 4, the Washington Post editorial board states, "this strike has degenerated into virtual war against the government, and should be regarded as such." President Roosevelt intervenes and the strike is resolved by the newly created National Defense Mediation Board.

President Harry Truman, Courtesy: National Archives

April 8, 1952

President Harry Truman intervenes in a steelworker strike, set to begin the following day. He asks Secretary of Commerce Charles Sawyer to seize and operate the country’s steel mills in order to keep them open for defense production during the Korean War. The steel companies object. The seizure is later found unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.

October 16, 1953

A strike spreads in the sugar cane fields of Reserve, Louisiana when sugar companies refuse to recognize the National Agricultural Workers' Union as a bargaining agent. State troopers patrol the roads to "head off violence." The local paper reports that "union members refusing to work will be evicted from their company-owned homes." The strike is called off in November with no gains for the workers.

November 4, 1970

A bomb explodes at the United Farm Workers (UFW) union office in Hollister, California during the largest strike of farmworkers in U.S. history. It is rumored to come from a rival union, competing to represent the farmworkers.

August 24, 1974

A mine supervisor at Duke Power Company shoots and kills a striking miner during a clash following UMWA efforts to recruit miners at Brookside Mine in Harlan County, Kentucky. Duke Power Company refuses to negotiate with union miners, and they hire prisoners on work release to guard the mines. The union miners are known to have shot the tires of vehicles carrying replacement workers.

April 18, 1989

In Lebanon, Virginia, 39 women occupy the headquarters of the Pittston Coal Company and hold a 36-hour sit-down strike in solidarity with the UMWA miners. The miners are in dispute with Pittston over changes in healthcare and retirement benefits.

#American 🇺🇸 Experience#Thirteen | NOVA | PBS#The Mine Wars#Timeline#Labor Wars#United States 🇺🇸#Civil War#Industrialization#Railroad 🛤️#Andrew Carnegie#Profits | Start to Finish#US Born | Immigrants#Regulations | Better Wages | Fewer Hours | Freedom of Speech | Assembly#Companies | Opposition to Unions#Surveillance | Worker | Blacklisted Unionists#Management

1 note

·

View note

Text

Human’s Striking 4 A Decent Living!

Why hasn’t anyone protest against some of these greedy landlords? These greedy landlords are the cause of so many people not being able to afford to even be able to live payday to payday. I call this price gouging!!!

Who are these landlords? Who is really buying our American real estate? And why? Every time a group goes on strike, a big percentage of the reason is because those in the group cannot afford rent.

Whoever is buying our American real estate is bringing down American businesses. Employers are being blamed for their employees not being able to afford rent, when it is really the greedy landlords that are the fault for many of our homelessness.

We are losing our American way of life. From small business, to affordable housing, even some of our corporations can’t afford rent.

For many, the answer is to build new affordable housing that will likely not be affordable. There seems aplenty of places that are now for lease and rent that sit empty due to the monthly rent rate. So why built more to just sit empty? Make laws against rent greed...which I call price gouging!!!

#Price gouging#rent#AFI#american film institute#SAG-AFTRA#WGA#writers guild of america#UPS#hospitality strike#railroad workers#Nurses#Teachers#Senior Citizens#United Farm Workers#UFW#HarperCollins strike#Alaskan school bus drivers strike#University strike#Dock Port Workers Strike#Air Lines pilots stike#All Employee Strikes#Homelessness#shelters#Transportation strike

1 note

·

View note

Text

CNN will look a rail worker in the eyes and ask "are your sick days worth hurting the US economy?" but they will never grow a spine and ask a railroad oligarch "is your greed worth hurting the US economy?"

#unionstrong#leftist#fightfor15#livingwage#capitalismsucks#raisethewage#bernie sanders#abolishthecia#workers of the world unite#railroad workers

0 notes

Text

#railroad strike#class war#class warfare#go on strike#strike#worker solidarity#workers of tumblr#workers of the world unite#you have nothing to lose but your chains#the last capitalist we hang shall be the one who sold us the rope#karl marx#communist#labor is entitled to all it creates

0 notes

Text

Pester your congress critters into siding with railroad workers who are preparing to strike over basics like sick days & fair pay. It's easy literally 2 minutes of texting "yes", "skip", or "no" as prompted

Just text "Sign PZPAKG" to 50409 to sign the action letter written by Resistbot.

0 notes

Text

In 1833, Parliament finally abolished slavery in the British Caribbean, and the taxpayer payout of £20 million in “compensation” [paid by the government to slave owners] built the material, geophysical (railways, mines, factories), and imperial infrastructures of Britain [...]. Slavery and industrialization were tied by the various afterlives of slavery in the form of indentured and carceral labor that continued to enrich new emergent industrial powers [...]. Enslaved “free” African Americans predominately mined coal in the corporate use of black power or the new “industrial slavery,” [...]. The labor of the coffee - the carceral penance of the rock pile, “breaking rocks out here and keeping on the chain gang” (Nina Simone, Work Song, 1966), laying iron on the railroads - is the carceral future mobilized at plantation’s end (or the “nonevent” of emancipation). [...] [T]he racial circumscription of slavery predates and prepares the material ground for Europe and the Americas in terms of both nation and empire building - and continues to sustain it.

Text by: Kathryn Yusoff. "White Utopia/Black Inferno: Life on a Geologic Spike". e-flux Journal Issue #97. February 2019.

---

When the Haitian Revolution erupted [...], slaveholding regimes around the world grew alarmed. In response to a series of slave rebellions in its own sugar colonies, especially in Jamaica, the British Empire formally abolished slavery in the 1830s. [...] Importing indentured labor from Asia emerged as a potential way to maintain the British Empire’s sugar plantation system. In 1838 John Gladstone, father of future prime minister William E. Gladstone, arranged for the shipment of 396 South Asian workers, bound to five years of indentured labor, to his sugar estates in British Guiana. The experiment [...] inaugurated [...] "a new system of [...] [indentured servitude]," which would endure for nearly a century. [...] Desperate to regain power and authority after the war [and abolition of chattel slavery in the US], Louisiana’s wealthiest planters studied and learned from their Caribbean counterparts. [...] Thousands of Chinese workers landed in Louisiana between 1866 and 1870, recruited from the Caribbean, China and California. [...] When Congress debated excluding the Chinese from the United States in 1882, Rep. Horace F. Page of California argued that the United States could not allow the entry of “millions of cooly slaves and serfs.”

Text by: Moon-Ho Jung. "Making sugar, making 'coolies': Chinese laborers toiled alongside Black workers on 19th-century Louisiana plantations". The Conversation. 13 January 2022.

---

The durability and extensibility of plantations [...] have been tracked most especially in the contemporary United States’ prison archipelago and segregated urban areas [...], [including] “skewed life chances, limited access to health [...], premature death, incarceration [...]”. [...] [In labor arrangements there exists] a moral tie that indefinitely indebts the laborers to their master, [...] the main mechanisms reproducing the plantation system long after the abolition of slavery [...]. [G]enealogies of labor management […] have been traced […] linking different features of plantations to later economic enterprises, such as factories […] or diamond mines […] [,] chartered companies, free ports, dependencies, trusteeships [...].

Text by: Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. "Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times". Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives (edited by Petitcrops, Macedo, and Peano). Published 2023.

---

Louis-Napoleon, still serving in the capacity of president of the [French] republic, threw his weight behind […] the exile of criminals as well as political dissidents. “It seems possible to me,” he declared near the end of 1850, “to render the punishment of hard labor more efficient, more moralizing, less expensive […], by using it to advance French colonization.” [...] Slavery had just been abolished in the French Empire [...]. If slavery were at an end, then the crucial question facing the colony was that of finding an alternative source of labor. During the period of the early penal colony we see this search for new slaves, not only in French Guiana, but also throughout [other European] colonies built on the plantation model.

Text by: Peter Redfield. Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana. 2000.

---

To control the desperate and the jobless, the authorities passed harsh new laws, a legislative program designed to quell disorder and ensure a pliant workforce for the factories. The Riot Act banned public disorder; the Combination Act made trade unions illegal; the Workhouse Act forced the poor to work; the Vagrancy Act turned joblessness into a crime. Eventually, over 220 offences could attract capital punishment - or, indeed, transportation. […] [C]onvict transportation - a system in which prisoners toiled without pay under military discipline - replicated many of the worst cruelties of slavery. […] Middle-class anti-slavery activists expressed little sympathy for Britain’s ragged and desperate, holding […] [them] responsible for their own misery. The men and women of London’s slums weren’t slaves. They were free individuals - and if they chose criminality, […] they brought their punishment on themselves. That was how Phillip [commander of the British First Fleet settlement in Australia] could decry chattel slavery while simultaneously relying on unfree labour from convicts. The experience of John Moseley, one of the eleven people of colour on the First Fleet, illustrates how, in the Australian settlement, a rhetoric of liberty accompanied a new kind of bondage. [Moseley was Black and had been a slave at a plantation in America before escaping to Britain, where he was charged with a crime and shipped to do convict labor in Australia.] […] The eventual commutation of a capital sentence to transportation meant that armed guards marched a black ex-slave, chained once more by the neck and ankles, to the Scarborough, on which he sailed to New South Wales. […] For John Moseley, the “free land” of New South Wales brought only a replication of that captivity he’d endured in Virginia. His experience was not unique. […] [T]hroughout the settlement, the old strode in, disguised as the new. [...] In the context of that widespread enthusiasm [in Australia] for the [American] South (the welcome extended to the Confederate ship Shenandoah in Melbourne in 1865 led one of its officers to conclude “the heart of colonial Britain was in our cause”), Queenslanders dreamed of building a “second Louisiana”. [...] The men did not merely adopt a lifestyle associated with New World slavery. They also relied on its techniques and its personnel. [...] Hope, for instance, acquired his sugar plants from the old slaver Thomas Scott. He hired supervisors from Jamaica and Barbados, looking for those with experience driving plantation slaves. [...] The Royal Navy’s Commander George Palmer described Lewin’s vessels as “fitted up precisely like an African slaver [...]".

Text by: Jeff Sparrow. “Friday essay: a slave state - how blackbirding in colonial Australia created a legacy of racism.” The Conversation. 4 August 2022.

#abolition#tidalectics#multispecies#ecology#intimacies of four continents#ecologies#confinement mobility borders escape etc#homeless housing precarity etc#plantation afterlives#archipelagic thinking

211 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!

I am an aspiring author who struggles with accurately portraying historical clothing, and I stumbled across your blog while searching for photographs and information on late 19th century/USA Gilded Age fashion. From the research I've seen compiled across books/the internet, the clothing of the upper class from that area is very well documented in paintings, garment catalogues, photographs, museums, etc....but finding information on what the day-to-day wear of normal people was like is proving much more difficult. Since you seem to be knowledgeable in the subject of historical clothing in this approximate time period, I was wondering if you knew about any good resources to learn more about what people who couldn't afford to follow upper class trends were wearing in the general era as well as any general information around these items.

If it helps, I'm focused on eastern and southeastern United States farming/small railroad town/mountain mining/gulf coast wetland communities, but even just more general resources about what sort of clothing that the average poor person during the Gilded Age wore would be greatly helpful. I've been able to find a few photographs here and there, but these probably aren't an accurate depiction of a persons' 'day-to-day' wear, and I also haven't found much on how women learned to sew homemade clothes, what garments if any would have been bought, where people in rural areas would have sourced their cloth, what undergarments were like, how work shoes were made & aquired, ect.

Please feel free to ignore this if it isn't something you're interested in answering as I'm sure you get a lot of asks, but I'd greatly appreciate it if you have any pointers!

So here's the thing about 19th-century clothing:

in many ways, it's the same all the way down

now, that's a serious generalization. is a farm wife in Colorado going to be wearing the same thing as a Vanderbilt re: materials, fit, and up-to-the-minute trendiness? obviously not. but because so much of what people wore back then has only survived to the present day in our formalwear- long skirts, suits, etc. -we tend to have difficulty recognizing ordinary or "casual" clothing from that period. I also sometimes call this Ballgownification, from the tendency to label literally every pretty Victorian dress a Ball Gown (even on museum websites, at times). Even work clothing can consist of things you wouldn't expect to be work clothing- yes, they sometimes worked in skirts that are long by modern standards, or starched shirts and suspenders. Occupational "crap job clothes" existed, but sometimes we can't recognize even that because of modern conventions.

A wealthy lady wore a lot of two-piece dresses. Her maid wore a lot of two-piece dresses. The trailblazing lady doctor working at the hospital down the road from her house wore a lot of two-piece dresses. The factory worker who made the machine lace the maid used to trim her church dress wore a lot of two-piece dresses. The teenage daughter of the farm family that raised the cows that supplied the city where all those people lived wore a lot of- you get the idea. The FORMAT was very similar across most of American and British society; the variations tended to come in fabrics, trims, fit precision, and how frequently styles would be updated.

Having fewer outfits would be common the further down the social ladder you went, but people still tried to have as much underwear as possible- undergarments wicked up sweat and having clean ones every day was considered crucial for cleanliness. You also would see things changing more slowly- not at a snail's pace, but it might end up being a few years behind the sort of thing you'd see at Newport in the summer, so to speak. Underwear was easier to make oneself than precisely cut and fitted outer garments for adults (usually professionally made for all but the poorest of the poor for a long time- dressmakers and tailors catering to working-class clientele did exist), but that also began to be mass-produced sooner than outer clothing. So depending on the specific location, social status, and era, you might see that sort of thing and children's clothing homemade more often than anything else. Around the 1890s it became more common to purchase dresses and suits ready-made from catalogues like Sears-Roebuck, in the States, though it still hadn't outpaced professional tailoring and dressmaking yet. Work shoes came from dedicated cobblers, and even if you lived in isolated areas, VERY few people in the US and UK wove their own fabric. Most got it from the nearest store on trips to town, or took apart older garments they already had to hand and reused the cloth for that.

I guess the biggest thing I want to emphasize is that, to modern eyes, it can be very hard to tell who is rich and who is anywhere from upper-working-class to middling in Gilded Age photographs. Because just like nowadays a custodial worker and Kim Kardashian might both wear jeans and a t-shirt, the outfit format was the same for much of society.

Candid photography can be great for this sort of thing:

Flower-sellers in London's Covent Garden, 1877. Note that the hat on the far right woman is only a few years out-of-date; she may have gotten it new at the time or from a secondhand clothing market, which were quite popular on both sides of the Atlantic.

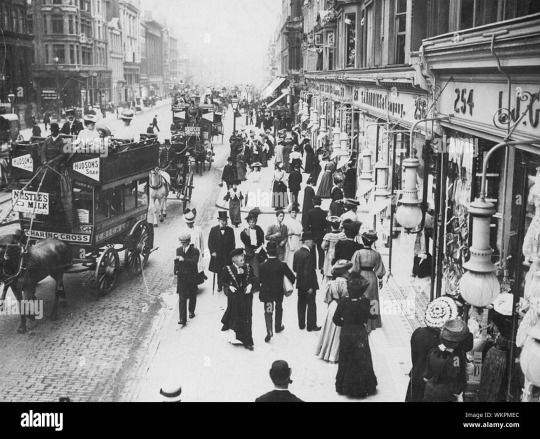

Also London, turn of the 20th century.

A family in Denver, Colorado, c. early 1890s.

Train passengers, Atlanta, Georgia, probably 1890s.

Hope this helps!

#ask#anon#long post#dress history#clothing history#fashion history#one of my friends once said 'most stuff made by historical costumers online isn't out of the question for a maid on her day off'#'or a middle-class wife'#and they're so right#it just ALL looks Fancy to modern eyes

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

worker uprisings are not an upside.

I see this rhetoric here all the time, and it drives me up the wall. So you're all getting a good rant here: a worker uprising is not good.

The worker uprisings that bought the NLRB paid for it in blood and lives, and another uprising means that we will have to find the price to buy it again. And there will be families, people, and lives blighted in the meantime. Worker uprisings are not upsides for anyone and they are not fucking consolation prizes. They happen when things go bad, horribly bad, and they generally only result in positive change insofar as they create so much chaos, bloodshed, and disruption that the overall situation has to change. In the mean time, people are still left dead, destitute, and maimed. If we can avert a worker uprising by using nonviolent means of pressure to force accountability, we should do that, because it results in vastly more stable outcomes for everyone. If this pissant, damn-fool shortsighted Supreme Court decision goes through and violence is the only remaining option to enforce change that anyone sees, that is a bad thing.That is not a flood gift. People will die fixing that bullshit. People did die fixing that bullshit!

You know how we got the NLRB the first time, back in 1935?

It took almost fifty years of labor unrest in the United States before we got the NLRB. Let's start with the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 (which was majorly disruptive but happened before labor unionizing was widespread). That's a great template for your fucking worker's uprising: there's no union leadership to coordinate fury and direct it properly, so when workers lose their shit after the third goddamn time wages get cut (not "fail to keep the pace of inflation," actually "you get less money now"), they all kind of do things on impulse without thinking much about long term strategy. The fury just erupts. In the case of the Great Railroad Strike, angry workers burned factories and facilities, seized rail facilities, paralyzed commerce networks, and existing power structures panicked and called out militias, National Guard units, and federal troops to forcibly suppress the workers. About a hundred people died.

Let me pop a cut down while I talk about what happened next. Spoiler: there's a lot of violence under the hood coming up, and like all violence, it absolutely sloshes around and hits people who aren't necessarily directly involved in conflicts.

You have continuing incidences of violence over strikes throughout the next several decades as nonviolent strikes are met with violence from pro-employer forces and workers resist with violence back. I can't even list all the violent incidents here that ended in deaths, because they were frequent. The 1892 Coeur d'Alune labor strike broke out into an actual shooting war and resulted in a number of deaths, not to mention months of detainment for six hundred protesting miners; the same year, you have another shooting war kicked off between hundreds of massed paid private Pinkerton security and striking workers in Pittsburgh through the Homestead Strike. Imagine how that's going to go down today.

And the thing about violence like this, and tolerance for violence, is that eventually you just get used to using it to get your way. You actually also do see quite a bit of violence conducted by striking labor workers, sometimes without recent provocation from management. For example, the national International Association of Bridge Structural Iron Workers embarked on a campaign of bombings from 1906-1911 that eventually culminated in a bombing of the office of the LA Times that killed 20 people. Do you want to live in a world where the only way to resolve conflicts like this is to risk someone bombing your office because your boss mouthed off at his cause? Even if he's right, do you want to risk losing your life, your arms, your friend, your sibs, to someone who thinks that the only option available to him to address systematic inequality is violence?

And you think about who really suffers when violence erupts, too. Look at the East St Louis massacre in 1917, when management tries undercutting the local white-run unions by hiring black folks who are systematically excluded by the unions. (If you think labor solidarity is free from the same intersectional forces that hit every other attempt to organize in solidarity for humans, you really need to go back and revisit your history books. We can do better and we should, but when we set up our systems and hope for the future, we have to be clear-eyed about the failures of the past.) Anyway, when labor tensions between white union workers and management's preferred use of cheaper, poorer, less "uppity" black people erupted, the white union workers attacked not management, but the black parts of town. They cut the hoses to the fucking fire department, burned huge swathes of East St Louis belonging to black homeowners, and shot black folks fleeing in the streets.

Money might not trickle down, but violence sure fucking does. The wealthy insulate themselves from violence by employing intermediaries to do all the dirty work for them, or even to venture into any areas that might be dangerous. When we resort to violence as the only way to solve our problems, inevitably the people and communities who pay the highest blood prices are the ones who have the least to provide. You think any of those robber barons are going to wind up on the ground bleeding out? They have their Pinkerton troops for that shit. The worst they lose is money; the rest of us have to stake our bodies and our homes.

No one should look forward to a worker uprising. If the Supreme Court is stupid and short-sighted enough to reduce avenues of worker redress to extra-legal means, the worker uprisings will come back around again, sure enough, and we'll all write our demands in blood once again. But the whole fucking POINT of the NLRB is that the federal government objects to having to sort these things out when they dissolve into open violence, so it sets rules about what the stupid short-sighted greediguts fat cats up top can do to reduce violence erupting again.

Anyway. Best thing I can think of right now is to get a Congressional supermajority in with the eye of imposing limits and curbs on the Court. Because look, I'll march if I need to, but I ain't going to pretend the thought puts a smile in my mouth and a spring in my step. Fuck.

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

SIMS HISTORICAL HORROR '24 (DAY 2): CROWN / 1930s

Ft. my model Atlas as the Railroad Man from Old Gods of Appalachia.

See the 31 prompts here!

Warnings are in the tags.

The history of the railroads in North America began long before the 1930s; it has its start way back in the 19th century. It is a bloody history of stolen land, corruption, murder, slave labor, and the (in my opinion) first evolution of the prison industrial complex in the United States. Thousands upon thousands were worked to the bone or even to death to lay rail across the continent. Rail, coal, and oil companies have made millions on the broken backs of their workers into the 21st century.

I love rail and trains, I think public transit in the US is sorely lacking. However, we mustn't forget the price that was paid by so many in the past.

#simsHH2024#simblreen#dead bodies tw#blood tw#old gods pod#old gods of appalachia#the railroad man#sims 4 horror

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The "Wrecking Crews"

"Eric Hobsbawm in his study of avenging bandits declared that such groups gained their appeal not as "agents of justice, but… [as] men who prove that even the poor and weak can be terrible." The striker groups embraced such a doctrine in exacting revenge on those who had transgressed community standards. Like other striker vigilante bands such as the Molly Maguires, they set out to punish both invaders (strikebreakers) and traitors (shopmen who continued to work), thus displaying to the victim and surrounding citizenry the required standards of behavior. These groups who engaged in intimidation and violence could be described as semi-autonomous gangs. Although not officially sanctioned by union hierarchies, the gangs' tactics handicapped the railroads' attempts to maintain production and repair. These gangs maintained that every conceivable method should be used to stop the importation of replacement labor. Their most common forms of action were shootings followed by kidnapping and punishment. These mobile bands, described by various authorities as "auto-raiders," "auto-squads," "wrecking crews," and "chain gangs," enforced community standards and values.

One form of intimidation was the general firing of weapons from speeding cars. The San Francisco Chronicle reported on August 1 that "auto raiders… swooped down on the Southern Pacific Railroad" shops at Colfax, and fired volleys into the windows and walls. Earlier, on July 14, "auto-raiders" attacked scabs at the Orville shops of the Western Pacific Railroad. The scabs were dragged from their bunk beds and "beaten severely." The auto-squads did not operate unchallenged. At Roodhouse, Illinois, on August 27, a gun battle railroad erupted after a carload of strikers attacked local shops. Deputy marshals and railroad guards returned fire and the strikers fled the scene. Fear of auto-squads inadvertently led to the August 12 shooting death of Deputy Marshal W. A. Cross at Little Rock, Arkansas. Suspicious of an automobile that appeared to be shadowing him, Cross girded himself for action. Three men in the car jumped out and "with pistols in their hands" yelled, "Get them up." Cross pulled out his revolver; a gun battle commenced, resulting in Cross being fatally shot in the head and chest. Unknown to Cross, the men in the car were city detectives searching for armed robbers. U.S. Marshal G. L. Mallory reported that not until the detectives searched Cross's body did they discover his badge and thereby his identity as a deputy marshal. Tragically, Cross was not the only victim; city detective J. W. Cabiniss died from bullets fired from Cross's revolver.

Drive-by shootings held enormous risk for both strikers and protectors of strikebreakers. To offset such danger, strikers used kidnapping to intimidate and wreak revenge. Victims of kidnappings consisted of three types: imported strikebreakers, local scabs, and foremen who had stayed at work. In the case of new hires, their treatment was given as a warning to leave the vicinity. The U.S. marshal of Danville, Illinois, F. H. Holmes, testified that strikers formed a "chain gang" and abducted a scab to Terre Haute and then beat him. At Slater, Missouri, one unfortunate was not only kidnapped but also tarred and feathered. Just as humiliating was the experience of strike-breakers working for the Chicago and North Western Railway. After being thrown out of Boone, Iowa, many were left only "in their B.V.D.'s or less."

Stripping of victims became a common and humiliating accompaniment of the kidnapping. Two Santa Fe Railroad scabs, for example, were kid- napped from Fenner, California, on August 9, and "stripped and turned loose in [the] desert by masked parties." On August 16, a Bureau of Investigation agent reported that a scab was "kidnapped, disrobed and left on the road" at Hornell, New York. At Pocatello, Idaho, a shopman who refused to go on strike was "stripped of his clothing and released beyond the city limits." On July 21 a scab was taken from Hamlet, North Carolina, and beaten. The kidnappers used the victim's hat as a warning to others, displaying it in a jeweler's window. Pinned to the hat read the message: "This is the remains of the first strikebreaker at Hamlet."

The real wrath of these semi-autonomous groups was reserved, however, for foremen who had remained at work and trained strikebreakers to do the shopmen's work. Strike sympathizers were blamed for tarring and feathering Bert Dickson, a roundhouse foreman for the Chicago and Alton Railroad, at Roodhouse, Illinois. Another victim, Henry Boyce, foreman of the Chicago and North Western, was abducted by an automobile gang at Antigo, Wisconsin, and transported to Elmhurst, Illinois. Although Boyce remained unharmed, the message had been made: his presence in Antigo could no longer be tolerated. A Great Northern Railroad foreman from Deer Lodge, Montana, experienced a similar embarrassing episode. The foreman was taken five miles out of town and "left in his underwear." His experience was nothing compared to that of W. T. Byland, a foreman for the Chicago and Elgin Railroad who endured a mock lynching. He testified that a rope was tied around his neck "so that [his] feet just cleared ground, for two or three seconds." Throughout the incident Boyle was told to quit work and join the strike.

The kidnapping and disrobing of scabs and foremen represented provocative punishments. By stripping the victims, the gangs symbolically transformed the scab into vulnerable and disgraced flotsam. The scabs then faced the lonely and humiliating experience of returning to their homes to get clothing and to tend their damaged pride. Just as devastating, stripping the victim of his clothing emasculated him. Thus accompanying the humiliation of the ordeal was a loss of masculinity.

In the South, a particular form of violence accompanied kidnappings, namely, whippings. In Fort Worth, Texas, for example, four strikebreakers were grabbed by a mob at a local dance, taken into the country and flogged with "leather straps," and warned to "head South and not return." The warning implies that the victims were Mexican. Also in Texas, sixteen guards were "stripped to the waist and flogged with blacksnake whips." Flogging also occurred in Alabama, Florida, Kansas, Louisiana, and North Carolina. The South, with its long tradition of vigilantism and its propensity for using violence, reflects most clearly a community's bid to mete out punishment and concretize collective displeasure. The struggle for control of their respective locales created a situation where many felt compelled to engage in such acts, or, at least, to look the other way when incidents occurred. It is of the utmost significance, however, that most of the whippings and kidnappings took place after injunctions had been handed down and marshals and troops had been dispatched.

Violence and vandalism occurred off the picket line as well. In Haverlock, Nebraska, for example, railroad sympathizers had their "houses painted yellow." The painting of signs on houses and sidewalks was particularly common. The act represented a public reminder that the occupant had transgressed community standards. Humiliation for the house dweller was sure to follow, tainting both the scab and his family members. Denver strikers utilized a similar tactic. A military intelligence report explained:

Strikers in Denver have resorted to the novel form of annoyance to strikebreakers of painting their houses yellow and in prominent places the word 'SCAB' is printed in large letters.

Nor was vandalism confined to houses. John Nelson, a foreman of car repairs at Cadillac, Michigan, discovered that his "three-wheel velocipede" was missing; after an extensive search, it was found in a river with a tag attached that read "Definition of a Scab." Scabs in Ogden, Utah, received threatening letters accompanied by "undertaker cards." Strikers or sympathizers also gained entrance to some shops and left messages for supervisory personnel. For example, a car inspector for the Michigan Central Railroad found his missing hammer with a note attached to it. The note spelled out a warning: "We are watching you and will get you yet."

Workmen were also threatened by persons in cars. A spy report from the Pennsylvania Railroad identified one particular "wrecking crew." The spy, identified as no. 28, explained that a string of "wrecking crews" had been formed in Chicago. According to the spy, local shopcraft leaders knew of the existence of these "crews" and encouraged them to intimidate supervisory officials. There is, however, no information as to the validity of this claim. Neither is there confirmation of the spy report that strike leaders sent out coded messages advocating sabotage. For example, a spy reported that the question in a union circular asking, "Are the trains on your division running on time," was really instructions to engage in sabotage.

A perusal of major newspapers during this early period of the strike high-lights numerous instances of fist fights, sabotage, and other violent confrontations. In many cases, however, these conflicts are not corroborated. Sabotage, however, constituted a common phenomena. Strikers and sympathizers, unable to control the flow of scabs into the shops, resorted to vandalism on a large scale. By far the most common method was the cutting of air hoses. Part of the braking system, these hoses also connected each freight or passenger car to one another. Although potentially dangerous, the cut hoses could easily be spotted by the train crew and yard workers. The main purpose was to delay the movement of trains. Other common forms of sabotage included greasing tracks, placing obstructions on the tracks, and placing emery dust and other foreign substances in journal boxes, pipes, and cylinders. The number of incidents was extremely large, and the geographical scope widespread. As Harry Daugherty remarked in 1923, "It is impossible to compile the exact number of such cases."

- Colin J. Davis, Power at Odds: The 1922 National Railroad Shopmen’s Strike. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1997. p. 96-99.

#strike#strike violence#vigilante justice#sabotage#drive by shooting#scabs#railway workers#railroad shopmen#union men#american federation of labor#railway capitalism#capitalism at war#working class struggle#united states history#academic quote#reading 2024

0 notes