#Rachel Ingalls who

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

By "roles" I mean playing a different character, and in a different piece of media; someone playing one character across a franchise only counts as one thing for the purposes of this poll, as does playing multiple characters in one franchise/piece of media

Below are some of this actor's roles. Please only check after voting!

Little House on the Prairie as Charles Ingalls

Bonanza as Little Joe Cartwright

Highway to Heaven as Jonathan Smith

Us 1991 as Jeff Hayes

Landon had 9 children, 4 of whom- Mark, Leslie, Michael Jr, and Jennifer Landon- all acted. One of his other sons, Christopher Landon, is a filmmaker. His granddaughter Rachel Matthews is an actor as well.

More roles

#actors#movies#television#do you know this actor polls#polls#tumblr polls#michael landon#multiple roles

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiiii ty for such a great uquiz!! Would it be possible to see the description of all the books you could get matched to? I’m curious what the vibes are for the rest!!

hi 🌷 here you go:

White Teeth by Zadie Smith: Excessive, maximalist and very ambitious multigenerational and multicultural epic novel that starts with the unlikely friendship between Archie Jones and Samad Iqbal. It explores themes of race, identity and the intersections of culture, heritage, and modernity. Clever and hilarious dialogue, very creative when it comes to language and style, unique and bold when it comes to narrative. Perhaps a flawed novel due to its ambition, but excellent nonetheless.

Despair by Vladimir Nabokov: Excellent writing; very ambitious and stylish. It is somewhat a twisted novel but you will find a lot of humor despite. The narrator speaks directly to the reader as he writes what he regards as his perfect crime. This novel is one of Nabokov's earliest works in which one can easily identify themes and literary devices that the author explored later in his most known works.

The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolaño: Brilliant and stunning novel about poets and poetry! Very dense and challenging; it requires patience from the reader. This novel is so infinitely dear to me that i can't even explain its brilliance, but i have to give you at least an idea of the plot so: The story is arranged in three parts and told from multiple points of view. It starts in Mexico City, in the 70s, and continues across decades and continents. It follows the adventures and misadventures of Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima—poets, drug dealers, wanderes, criminals. Now, about the themes, the writing, the style, the narration? Just absolutely perfect even at its most tedious, difficult and anticlimactic parts.

The Hearing Trumpet by Leonora Carrington: Unconventional, absurd, imaginative and exuberantly surreal apocalyptic fairytale quest. It follows 92 year old Marian who is sent off to a peculiar old-age home. If you aren't familiar with Leanora Carrington's art you should look at some of her paintings because this wonderful novel feels just like her surrealist paintings!

Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls: This novella tells the story of a love affair between a depressed suburban housewife and an amphibian creature who escaped a scientific research center. It might sound like a quirky fiction story but it actually deals with the most mundane and banal aspects of life and human relationships. Brilliantly written; neat and precise prose, wonderful storytelling. The author knew what she was doing and not a single word she wrote was wasted.

The Borrowers by Mary Norton: Delicately written little adventure about tiny people who live in the secret places of houses. I am enamored (obsessed!!) with miniatures—dollhouses, dioramas, fairies—so imagine how dear this book is to me.

Sharp Objects by Gillian Flynn: The murders of two girls bring reporter Camille Preaker back to her hometown. As she works to uncover the truth about those crimes, Camille finds herself forced to unravel the psychological puzzle of her own past. Very entertaining read. It has best seller written all over it (which might not be the biggest compliment lol but i mean for this genre so it is a compliment).

Rage by Sergio Bizzio: Claustrophobic, anxiety inducing, fast-paced psychological thriller that made me think of Bong Joon-ho's Parasite the whole 4 hours it took me to read it. I read it in it's original language, Spanish, and i particularly loved the dialogue; its idiosyncrasies and authenticity (tqm Argentina!)

High Fidelity by Nick Hornby: Rob, an obsessive music fan, reminisces his top five worst break ups to understand his most recent heartbreak. He is a very arrogant and cynical guy who defines his entire life through records, and because he is constantly interacting with music that almost exclusively deals with love—and a very idealistic version of it—he finds himself unsatisfied with the way his life has turned out.

#so sorry it took me so long to reply!!#idk if you meant of ALL the quizzes... 👀 anyone these are 2023's only 🫣#💌#anyway* lol not anyone

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

[S04E08] This Thing of Ours

"If we lay low and keep our hands off the trigger? We might just make it."

There’s someone being held inside Diatoma. Someone who could make or break the future of the Lunar Mafia. [S04E08] This Thing of Ours.

This episode was written & directed by SJ Ryker, & edited by Sam Stark.

It features Jeremy Tucker, Rachel Scully, & Adam Steven Halecki, and includes Jerry Harris, Emma Skinner, Ari Ingalls, Kale Brown, Aubrey Akers, Hera Alexander, Oz Stark, & Max Newland.

Also including Roonie Hunt, Quill Turner, Kasha Mika, SJ Ryker, Sam Stark, & Lafayette Uttarapong.

It was transcribed by @facelessoldgargoyle.

And join us for our live-listen premier tonight at 6pm Pacific! https://youtube.com/watch?v=VXR_nmZzqHQ (Also, you'll want to stay tuned after the credits on this one.)

#Breathing Space podcast#breathingxspace#new episode#you like concurrent stories don't you?#how about stand alone eps but with some continuity

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catch up with me tag

Thank you to @boredmoodlet for the tag. Only did this one a few days ago so I'll just answer the couple of ones that have changed.

last song: Tumble Down the Undecided by Sarah Neufeld off her fantastic album Detritus from 2021.

last show:

currently watching:

currently reading: I finished Mrs Caliban by Rachel Ingalls, it was really good a darkly funny feminist novella about a woman in a deeply unhappy marriage who starts an affair with a frogman 👍

Now I've moved on to this gorgeous illustrated edition of Dracula from Four Corners Books, never read Dracula before but this is the time to start 😊

(publisher's photo not mine btw)

current obsession:

Have completely lost track of who's done this now so I'll just tag a few people I didn't tag last time round and hope for the best! @dragonflydaydreamer @biffybobs @whyeverr @simmer-rhi @memoirsofasim @sheepiling @nuttydragonbird @plumbobster @tarobeans

As always feel free to ignore if you already did this/prefer not to 😊

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

They're not necessarily capital H horror, but a few recs: My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier, Into the Drowning Deep by Mira Grant, Wylding Hall by Elizabeth Hand, The Drowning Summer by C.L. Herman, Things in Jars by Jess Kidd, The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin, Dear Daughter by Elizabeth Little, The Silent Companions by Laura Purcell, The Incredible True Story of the Making of the Eve of Destruction by Amy Brashear, The Girl Who Slept With God by Val Brelinski, The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue, Little Egypt by Leslie Glaister, The Degenerates by J. Albert Mann, The Red Parts by Maggie Nelson, Kindred by Octavia E. Butler, Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls, The Seep by Chana Porter, Space Opera by Catherynne M. Valente, Black Water Sister by Zen Cho AND I haven't read them yet but: Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez, Queen of the Tiles by Hanna Alkaf, Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth...

ooh thank you!! a couple of these are on my TBR

just wanna shout out The Degenerates by J Albert Mann. it's not a horror, just a horrifying look into the treatment of disabled and "undesirable" women and girls in the 1920s, but oh my god it remains one of my favourite books, I highly encourage anyone to pick it up, I love it so much

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smells Like Home | Soap x Nina

Tags: All fluff

John reached out for Nina instinctively. He frowned softly as his hand felt the empty space on her side of the bed.

"Neen?" He opened his eyes to find himself alone. A spike of fear and he was upright, eyes darting across the room for assessment. Orange light from the early morning came through the cracks in the curtains.

He was up and out of bed before he could blink. The hallway smelled sweet like brown sugar and bananas.

"Nina?" He called out. The light in the kitchen was on.

"Kitchen!" She responded. His heart started settling back into his chest. He took a deep breath before rounding the corner to find her.

She was sitting on the rug, back against the cabinets. Her blonde hair was still messy from sleep and her knees were tucked underneath her, no, his shirt. The oven was on with a timer set. A bowl and measuring cups sat in the sink.

"There's coffee on the counter for you," she looked up from her book with a smile. He grinned back as he filled a mug and settled down next to her.

"What did you make?" He asked, resting his head on her shoulder.

"Banana bread. I saw a recipe last night and we had a couple frozen bananas," she shrugged. He hummed contently and kissed her cheek.

"You got up early to do this?" He used her phone to check the time. Not even seven am yet.

"I couldn't sleep." She admitted.

"We'll have to make time for a nap today, won't we?" He wrapped an arm around her and pulled her close. She fit so perfectly against his side. "What's your book about?"

He could never keep up with her reading. She'd clear four or five a week, sometimes more, depending on length. Their shared flat was littered with stacks of various books.

"A woman who has an affair with a weird frog man creature." John blinked. She'd grown fond of the weirder books, stories about people out of place and lost in the world. He took a sip of coffee.

"Can I read it when you're done?" He kissed her temple.

"I just started if you want me to read it out loud."

"I'd like that...I... I love you, Neen." His hand rested on her knee. She leaned into him more, wrapping an arm around his middle. It didn't matter that the kitchen floor was uncomfortable or that sleep still tugged on his mind. He had her in his arms, hot coffee in his favorite mug, and banana bread in the oven. He had everything he could ever need right here on this floor.

"I love you." Her hand had found his and squeezed.

A/N: I'm giving Nina the same taste in books as me. The book is Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls.

#john soap mactavish#john soap mactavish x oc#I need to clean up hte tags because I don't remember which one I use more#whoops#have some fluff#Soap x Nina

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

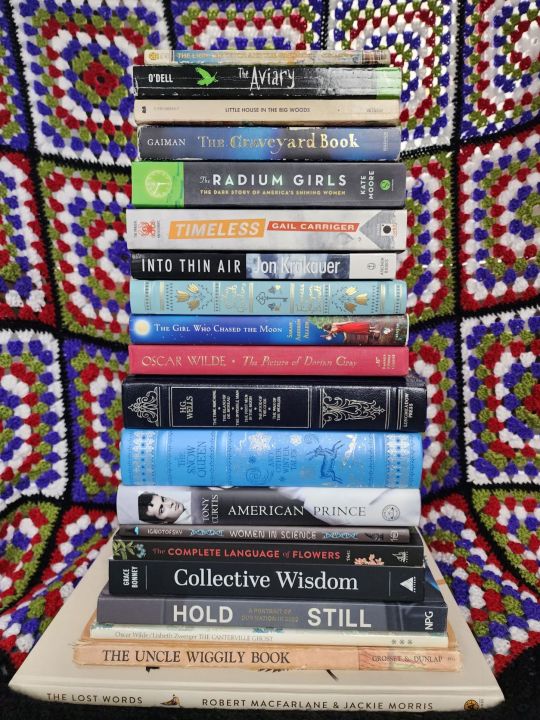

Twenty Books Challenge

Hypothetically, you are only able to keep 20 of your books. Only one book per author/series. So what books are you keeping?

I was tagged by @the-forest-library - thank you!

This was way harder than I imagined (and I still messed up because I have 2 books by the same author oops). I was surprised by how many of the books I chose to keep are non-fiction. I also may have messed up with the rules with some of my collection books but oh well.

From the bottom up:

The Lost Words by Robert MacFarlane & Jackie Morris - just a beautiful book that reminds us how important words are.

The Uncle Wiggly Book by Howard R. Garis. One of the first books I read as a child, and this is the copy I've had since childhood. It's also the book that started my book collecting hobby.

The Canterville Ghost by Oscar Wilde - such a sweet, fun story and this one has great illustrations. (this is the book I'd switch out for something else since I messed up with the rules)

Hold Still by various. This was a project started by The Duchess of Cambridge during The COVID Pandemic. She and the National Portrait Gallery collected thousands of photos and went through and chose the top 100 to put into book form. It's a story of life during a modern pandemic. It's incredibly moving.

Collective Wisdom: Lessons, Inspiration, and Advice From Women Over 50 by Grace Bonney. A Christmas gift from one of my kids in 2021. It's a beautiful collection from women, most of whom are average, every day women, very few celebrities or well knowns are in this book. And the diversity is great too (Native, WOC, Disabled, Trans etc.).

The Complete Language of Flowers by S. Theresa Dietz the classic book of flowers and their meanings with beautiful drawings.

Women in Science by Rachel Ignotofsky. 50 Inspiring and notable women in Science. Fun, cartoonish illustrations as well.

American Prince by Tony Curtis. Because he's so pretty, and his whole face lit up when I told him what I thought of his book when he signed it for me.

The Snow Queen and Other Winter Tales by various. Collection of tales from various Fairy Tale books and authors. I have a few of these but this one I think is my favorite.

The Works of H.G. Wells by H.G. Wells. A collection of stories by Wells. The Time Machine was the first Science Fiction book I'd read. I read it as a teen and I loved it.

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (and this would be the one Wilde book I'd keep since I'm only allowed to have one book by the same author). This is my all time favorite book.

The Girl Who Chased the Moon by Sarah Addison Allen. I have loved and own every book Allen has written, but I think this is my favorite.

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. I have a few copies of this book, it's a favorite. I chose this version because it's just very pretty.

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer. Because Mother Nature DGAF. Also as I was being admitted to the hospital for my hysterectomy the admitting nurse who was doing all my vitals, giving me my IV etc. was reading this book and we discussed it. We both agreed that this book confirmed for us that we never want to climb Mount Everest.

Timeless by Gail Carriger. The final book in the Soulless series. I loved this whole series. I chose the last book, however, because it's one of the few series that I absolutely loved everything about how it ended.

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore. The incredibly infuriating story of the women who risked their lives in watch factories and how little help they got. This book made me a better feminist and grew my understanding of the importance of women's rights and how important our history is.

The Graveyard Book by Neil Gaiman. I think this was the first Gaiman book I read and it's my favorite.

Little House in the Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder. A series I read one summer in my youth. I chose this one because of its iconic cover, and because it's the first in the series.

The Aviary by Kathleen O'Dell. One of my kids read this when they were younger and suggested it to me. It's one of my all time favorite middle grade reads. It's magical.

The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. My 5th grade teacher, Mrs. Bauer (my favorite teacher ever) read this out loud to us in class. I fell in love with the story. I never read it again until I was a married adult with children. It's the first book I ever re-read as an adult (Uncle Wiggly is the first book I ever re-read). And I re-read TLtWatW at least every couple of years. I tag anyone who wants to do this!!

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

3, 4, and 13!

ty!!!

(3) what were your top five books of the year?

in no particular order i loved:

mrs caliban by rachel ingalls. this is SO good. ingalls went straight on my list of forgotten 20th century women that i want to become. actually it's an extremely short list but she's on it right behind my forever queen gina berriault look her up

what you can see from here by mariana leky. honestly this has faded from my memory a little bit since i read it in the spring but i remember being totally obsessed with the prose and narrative movement of this. id love to relearn all my german and read this in the original and also all leky's other books (i believe she has other novels but idk if any have been translated?)

a home at the end of the world by michael cunningham. is it boring to recommend michael cunningham maybe. did this book make me insane and do i frequently think about specific lines and phrases from particularly the first third of it YES. michael call me i just want to talk

the tree and the vine by dola de jong. being in secret unrequited love with your roommate is so scary and horrible ! this book is like a very very sharp gemstone !

all fires the fire by julio cortázar. cortázar is one of my favorites ever and this collection is just like completely complex and perfect like a box of bitter chocolates. right after german i will be learning spanish in order to experience these stories for the first time in a new way again

honorable mentions to:

reprieve by james han mattson. it's possible that this isn't good but i had SO much fun reading it. one of the only books i have read over the past few years that i found really and truly exciting. escape room novel!!!!

the glassy, burning floor of hell by brian evenson. good book! but MOST importantly my favorite title of the year.

anddddddd interview with the vampire. sorry. i loved this.

(4) did you discover any new authors that you love this year?

definitely rachel ingalls! i had heard of her but never read her and i am so pleased to have finally dipped my toesies into her work. maybe rivka galchen too... everyone knows your mother is a witch was good and i am excited to see if i like her other work even better. and dola de jong! i had never even heard of her! if any of her other work is ever available in english translation i will be sprinting to the library

(13) what were your least favorite books of the year?

ahh yes my favorite. hating. let's see...

the charm offensive by alison cochrun. unfortunately had to revoke the bisexuality card of the dear friend who recommended this to me. stupid and really bad in ways that matter (fetishistic strange representation of gay men) as well as ways that are just annoying (horrible prose and overtherapized emotional narratives)

a visit from the goon squad by jennifer egan. sad that i broke my 11 year streak of never reading this but it was required for a class. the PULITZER PRIZE? for LITERATURE? are you SURE?

the snow queen by michael cunningham. goddamn the higher they climb the harder they fall!!!!!!! this was one of the worst structured and most sloppily and fluffily written novels i have ever read. and from the king of structure and perfect sharp prose himself. sad... well there's other fiction writers

how to find your way in the dark by derek b miller. a genuinely antisemitic book recommendation from the aforementioned formerly bisexual dear friend. horribly written and with a bad case of my protagonist is the specialest little boy in the world. special shoutout to this book for inspiring the novel i am currently working on by being so bad that i looked at it and thought even i could do a better job at this

the temps by andrew deyoung. no more clever little books by clever little guys. it is appropriate that the cover of this is green like toxic slutch because it gave me horrible indigestion. thinks it is so smart about the world and is so fundamentally mistaken about every single one of the issues it tries to tackle

and i COULD GO ON!!!!! there are bad books being published every day on this bitch of an earth!

this was so fun i love yelling

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first ambition as a writer was to be a poet (isn’t most writers’?) but after a sequence of 154 sonnets (and they all rhymed!), I had to admit that poets are born and that the sound, image and idea come to them in an indivisible bundle that cannot be constructed. It really is a gift. Great poets think like Einstein. Most contemporary poets write broken-up pieces of prose sometimes very good and interesting and memorable, but Cole Porter or Country and Western lyrics are often better than that without pretending to be The Real Thing. My top favorite literary idols are playwrights: Shakespeare, Euripides, Ibsen.

I’ve never given much thought to my place among contemporary writers, nor about readers. I write because it’s a compulsion. There are many, many other writers I hold dear, some living and some dead, but none of whom (after the experiments of adolescence) I’d try to emulate or imitate. When asked about writers who have influenced me, I used to cite a few but the real answer should be “all the ones I’ve read.”

rachel ingalls

0 notes

Text

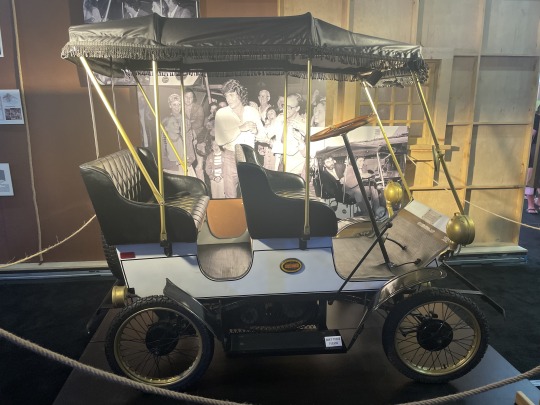

Melissa Gilbert had a ready answer when asked why fans of Little House on the Prairie always seem to burst into tears whenever they see her in person.

“Because I do! I think it’s just, you know … the show evokes so much emotion in people and made everybody feel,” Gilbert told the crowd Friday at the three-day Little House on the Prairie Cast Reunion and Festival in Simi Valley, CA. “So when they see us, they have the feels, and then the leftover feels from 50 years ago. Now they’re feeling it again through children and grandchildren. There’s this continuity and sense of family. This is a giant family reunion.”

Thousands of people converged upon Simi Valley’s Rancho Santa Susana Park to remember Little House on the Prairie, the Michael Landon starrer that debuted 50 years ago this year. With the promise to see stars like Gilbert, who played Laura “Half Pint” Ingalls, as well as Alison Arngrim (Nellie Oleson), Karen Grassle (Caroline Ingalls), Bonnie Bartlett (Grace Edwards), Dean Butler (Almanzo Wilder) and Linwood Boomer (Adam Kendall), fans waited in long lines to collect autographs, screen old episodes, and take pictures of re-creations of the iconic sets.

Organizers also assembled a mini-exhibit of Little House artifacts, like copies of old scripts, set stills, Little House inspired lunch boxes, and a ’70s Panavision camera that’s similar to the type used by show. There’s even a shirtless photo of Landon setting up a shot.

The most impressive display was not the re-creation of Oleson’s Mercantile or Half Pint’s homestead, however (though plenty of people took turns taking pictures in them). It was Landon’s golf cart that was made to look like a Surrey — a Christmas gift from cast and crew in 1976.

The festival also features lots of panels with the original stars, as well a tributes to Landon (who died in 1991) as well as other Little House stars who have passed. And good news for the attendees who decide to fork over $45 for one-day admission: Besides the one she did Friday, Gilbert also has a panel planned on Sunday, as does Arngrim and Grassle.

There’s even a panel featuring Rachel Linda Greenbush and Sidney Greenbush, the twins who took turns playing Half-Pint’s little sister Carrie. In fact, the crowd on Friday was particularly giddy about the possibility of seeing actors who played wee tots in the original series.

“My brother is here!” exclaimed Gilbert about her younger sibling Jonathan, who played Nellie’s brother Willie on the show. The crowd promptly cheered. “We were just doing a group photo with the entire cast and he walked in. He made the biggest entrance of any cast member. Of course, everybody screamed. I burst into tears. Alison was inconsolable.”

0 notes

Text

Year of Lists

January Books

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store by James McBride (ToB Read) *3/5 - there's an ease in the storytelling, it gives you time to luxuriate in the plot. I loved the back-and-forth, the exploration of the past and of characters who were not central to the main goings-on, but just like in life, you can trace their influence through time. Despite the writing talent, and the much promising setup and characters, I had trouble connecting to this novel; most of my joy in reading this came from the observation of McBride's craft in putting this together.

Folklorn by Angela Mi Young Hur *3.2/5 - for a minute there I really thought this would be the great Korean novel I've been looking for. Firstly: one for the great covers list. The marrying of science and folklore/superstition/oral inter-generational storytelling: chef's kiss. I wish it amounted to more than it actually did. The novel opens in dreamy language, otherworldly imagery, beautiful, beautiful world-building. It unfortunately loses its coherence and promise about 30% in. It fizzles into a concept that begs for a better storyline to hold it together. I wish the protagonist's personality amounted to more than self-wallowing in pity and self-othering. There are nuances that could have been explored so deeply; I wanted her to see herself as the wonder I saw her as. Nonetheless, there is magic here, there is familial complexity, and beauty.

Notable quote: “The first generation who come are grateful, certainly. They can endure much, swallow their pride. Their children want more—the freedom not to be grateful, indebted, and beholden.”

The Atlas Complex by Olivie Blake *3/5 - it hasn't even been long since I read this and I can't even remember the plot. Positives: Blake's writing gets better and better, clearly not in the general, book-making sense, but in the pleasant-to-read, I-love-spending-time-with-your-words way. I did enjoy the reading of this, I just don't think this was written because the story was there, but rather, because the trilogy needed to end. I love the characters and I love the illustrations and the elements that make Atlas so exciting: magic, ambition, a sentient, secret, ancient library full of the deepest, darkest knowledge of the world - the dark academia of it all. Better luck with the prequel. We're suckers for it either way.

The Premonition by Banana Yoshimoto *5/5 - a perfect little dream - I LOVE BANANA / Mrs Caliban by Rachel Ingalls *5/5 - superb.

Both of these are 5 stars partially because they're novellas. They're dreamy and otherworldly, tackling their specific subject-matters with dexterity. Mrs Caliban is worth an afternoon, especially for fans of The Shape of Water.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke *4.7/5 - boy oh boy was this a surprise. I don't have much to say, THIS.IS.INCREDIBLE. It's not going to be everyone's cup of tea, and perhaps wouldn't be mine if it was written by another author. I read this in a day.

The Dark Tower: The Drawing of the Three by Stephen King (audiobook) *4/5 - this is a reread, first read-through was a physical copy; I'm listening to the series now because I'd missed that world. The narrator for this one is better than the first and his work is only improving. By the end of this one you can tell this is a narrator who truly understands King's writing, with all its humour and intricacies.

The Green Mile by Stephen King *4.7/5 - it's as good as you think it is, as good as everyone says it is. In case it wasn't clear I LOVE STEPHEN KING.

#the heaven and earth grocery store#james mcbride#books#reading#bookblr#book reviews#historical fiction#folklore#magical realism#korean literature#fantasy fiction#atlas#atlas trilogy#olivie blake#angela mi young hur#the premonition#banana yoshimoto#japanese fiction#fiction in translation#mrs caliban#the shape of water#rachel ingalls#piranesi#susanna clarke#literary fiction#stephen king#the dark tower#audiobooks#the green mile#lists

1 note

·

View note

Text

It would be easy, if you were a person who read women often but spoke to them rarely, to imagine that contemporary women hate men. Scholars write books and essays about how tragic heterosexuality is; queer writers in and out of the academy pity straight girls, who, in turn, bemoan their fate on social media or in personal essays that go viral there.1 Some go so far as to suggest that no women genuinely enjoy heterosexual sex, but most confine themselves to the idea, or the performance of the idea, that heterosexual love is second-rate and doomed. Fiction isn’t immune. In recent literary novels like Lillian Fishman’s Acts of Service or Katherine Lin’s You Can’t Stay Here Forever, good sex between men and women abounds, but a good man is hard to find. In a March New York Times piece on the revival of Norman Rush’s 1991 novel Mating, Marie Solis wrote that the book’s fans “have noted that a largely positive portrayal of love relationships in general, and heterosexual relationships in particular, is a rarity in fiction.” (Rush’s fans, evidently, are not reading romance.)

It would also be easy, if you had read about the writer Rachel Ingalls’s work but never opened one of her electrically strange short books, to see her as an early adopter of today’s men-are-trash-ism, which the writer Asa Seresin has referred to as “heteropessimism.”2 Ingalls is certainly a bard of what John Updike, describing her 1983 novel Mrs. Caliban, called “a deep female sadness that makes us stare,” yet the madcap spirit that suffuses her writing keeps it from being fatalistic. She gravitates toward the odd aside, the baffling phenomenon, the bloody ending. But she never betrays what’s happening next in her stories—foreshadowing is unthinkable. This unpredictability is her aesthetic and philosophical hallmark.

It is true that the single strongest current running through Ingalls’s fiction is the boundary-shattering energy of female desire, which, whether satisfied or denied, she depicts as both a life-giving force and a destroyer of worlds. And when Ingalls writes about denied desire, the culprit is generally a negligent husband. Marriage is not an appealing prospect in her fiction. Consider In the Act (1987), recently reissued in the UK as part of No Love Lost, a collection of eight of her novellas,and in the US as a slim standalone. It opens with a man named Edgar telling his wife, Helen, that she’s being unreasonable. “Of course I am. I’m a woman,” Helen shoots back. “You’ve already explained that to me.”

Edgar is a great explainer. Ingalls, who is masterful at skewering her characters, writes that he wins arguments by explaining his side in a tone that is “knowing, didactic, often sarcastic or hectoring. Whenever he used it outside the house, it made him disliked.” Whether he’s liked in the house is unclear. Helen mainly seems exasperated with her husband at the beginning of In the Act, but Ingalls does let the reader know that, when he so chooses, he’s good enough in bed that Helen is both “satisfied [and] surprised.” Mainly, though, Edgar uses sex to pacify Helen so she’ll stay out of his attic lab, on which he has placed a Bluebeard-esque prohibition. When she enters anyway, she discovers that he’s been building an animatronic sex doll.

Though Edgar’s doll is highly realistic, in an idealized, pornographic way—“Pubic hair and nipples everywhere you look,” Helen sputters, describing her—Edgar betrays his fundamental lack of imagination by dressing her in the flouncy, childish clothes an expensive doll would wear and naming her Dolly. Although Edgar is a good inventor, he is, like many Ingalls husbands, a fool. However, that doesn’t mean all her men are.

Ingalls’s female protagonists share an instinctive faith that, no matter how disappointing their men are, better ones are out there. For them, men are often a dream, a repository and symbol of hope that goes far beyond the sexual. Crucially, that hope is often met, though rarely in the way one would expect (or, in some cases, want). Patricia Lockwood writes in her foreword to No Love Lost that the word “man” “shines in her writing the way the word ‘shop’ does: a place to walk into, spin around till your skirt flares and at last get everything you want.” Lockwood’s description captures the 1950s tenor of Ingalls’s work, but the truth is, nobody in an Ingalls story is longing for stuff. For her women, getting everything you want is an emotional prospect. They long for pure and sustained male attention paid equally to their bodies and their minds. When they get it, it brings them back to life.

Ingalls herself lived, as far as anyone knows, a peaceful life: she was not one for interviews or press. She was born in Massachusetts in 1940; her father was a Harvard Sanskrit professor, and her mother, like so many of Ingalls’s protagonists, stayed home. After graduating from Radcliffe in 1964, Ingalls moved to England, where she wrote in relative obscurity until 1986, when the British Book Marketing Council surprised readers by naming her Mrs. Caliban one of the twenty best postwar novels by American writers.

Mrs. Caliban is very short—hardly long enough to qualify as a novel rather than a novella—and, like many of Ingalls’s works, feels distinctly American despite her expatriation: it is set in an unspecified suburb that feels Southern Californian, a place where cars, malls, and chitchat rule. At the book’s start, a lonely housewife named Dorothy is grieving the death of her son, Scotty, years ago, as well as a subsequent miscarriage; then her poor little dog, Bingo, was killed by a car, leaving Dorothy feeling that “everything near her died…. It was a wonder the grass on the front lawn didn’t turn around and sink back into the earth.” Her husband, Fred, a callous jerk at the best of times, withdraws from her grief. Dorothy’s misery is so flattening and absolute that she is, as she tells her friend Estelle, “too unhappy to get a divorce.” She is not, however, too morose to start a steamy affair with a giant humanoid frog.

Larry, Mrs. Caliban’s frog-man, turns up at Dorothy’s house in need of shelter. He’s on the run, having killed a pair of sadistic scientists who captured him in the Gulf of Mexico and performed experiments on him. Dorothy takes Larry in without a second thought. Before long, she’s teaching him how to sleep with a human woman, which seems uncomplicated, since his body is “exactly like [that of] a man—a well-built large man—except that he was a dark spotted green-brown in colour.” Larry and Dorothy fall in love, about which the novel leaves no room for doubt: this is a good thing, and readers should root for it. Yes, Larry has webbed hands and feet and his true home is under the ocean, but his species is far less important than his effect on Dorothy. Once she and Larry get together, she lights up almost instantly. She’s sneaking around the suburbs with him at night, sewing gigantic wigs for him by day to disguise his green head when he goes out. She’s having a great time, and it’s lucky for both her and Larry that Fred is too oblivious to notice.

Ingalls writes Mrs. Caliban with a breezy matter-of-factness that chimes with Dorothy’s desire for Fred to keep looking away from her new happiness, from their guest room where Larry is staying, from the sacks of avocados—Larry’s pricey favorite snack—that she’s suddenly buying. The novella’s tone all but shouts, “Nothing to see here!” Her writing does not invite readers to slow down. But her sentences reward anyone who has the willpower to pause. In one of the very few moments when Dorothy herself stops moving, she sits on the beach, waiting for Larry to surface from a night swim in the ocean:

But down there it would be dark now, and not the lovely lighted aquarium she imagined it to be during the daylight hours, eddying with schools of tiny, delicate animals floating and dancing slowly to their own serene currents and creating the look of a living painting. That was wrong, in any case. The ocean was different from an aquarium, which was an artificial environment.

In these three sentences, beauty and fantasy give way abruptly to Dorothy’s understanding that she’s fallen for a wild creature. She can keep Larry in her guest room, but not forever. No matter how much she enjoys floating on the current of love that runs between them, he’s going to go back to the ocean someday.

Love and wildness collide again in Binstead’s Safari (1983). Millie Binstead, ignored for years by her anthropologist spouse, Stan, comes roaring into her own after starting a hot safari-town romance with a hunter and lion expert named Henry “Simba” Lewis who promises to marry her once she gets rid of her husband. Stan, a stereotypical academic, is almost constitutionally incapable of noticing things, but he realizes rapidly that Millie has made contact with a new and powerful side of herself. Mainly what he sees is the sexual wildness Lewis has awakened in her, though he recognizes it only in the form of his own sudden desperation to sleep with her after years of disinterest. He gets even hornier once she asks for a divorce. “I don’t know what you think you’re proving,” he grouses after she turns him down one morning. “I’m having wet dreams now.” Millie, whose prince is finally coming, couldn’t care less.

Binstead’s Safari is Ingalls’s longest novel, and its length allows her to contrast Millie’s relationships with both Stan and Lewis with slower forms of love that rarely appear in her shorter works. Ian, the Binsteads’ main guide, has a steady, calm relationship with his wife, Pippa; his younger colleague Nicholas, meanwhile, is quietly frantic over his wife, Jill, whose recent nervous breakdown has left her unable to care for their children. Nicholas has to keep earning but plainly longs for her. Every letter she writes sends him into a spiral of misery that Millie, herself longing for Lewis, talks him through. In one of her arguments with Stan, she holds Nicholas up as an example, saying, “Everybody thinks Jill is in a mess—at least Nicholas is on her side. What I’m trying to say is that for some reason, it made you feel good every time I failed at something.”

Millie and Lewis don’t get as far as marriage, and it’s safe to assume that, if they did, it wouldn’t be a union like either Ian and Pippa’s or Nicholas and Jill’s. Depending on how you interpret the end of Binstead’s Safari, Lewis may be a lion-god in human guise (I think he is), and myths across cultures tell us that gods and women rarely have long relationships rooted in empathy. Ingalls herself presumably agrees: in Mrs. Caliban Dorothy knows that the fact that Larry’s a frog-man means they have no long-term future. But the long term isn’t absent from Ingalls’s writing. In the Act is very much about a woman who wants an Ian-and-Pippa-style marriage. What Helen wants—what she yearns for—is sustained love, sexual connection, and affection from a real human man. She wants them so badly she’d do just about anything.

In the Act seems initially to be about artificiality, not wildness. Helen is, after all, in marital competition with a sex robot—except that the competition, once discovered, lasts less than an afternoon. Within moments of finding Dolly in her husband’s attic lab, Helen has hauled her off to a train-station storage locker, from which she will soon be stolen by a lunk named Ron (more on him later).

Helen’s fury makes her both decisive and powerful. It also releases her own wildness, though not in quite the same way the lion-god and lizard-man relationships in Binstead’s Safari and Mrs. Caliban do. Dorothy and Millie need to reencounter pleasure in a way Helen does not. She’s fully in touch with her sexuality, though anger gives it a new edge. Ingalls takes advantage of the novella form’s brevity to convey the 0-to-100 intensity of Helen’s intertwined emotions without having to tease them out. She describes Helen’s initial confrontation with Edgar about Dolly in the language of a high-quality orgasm:

She thought she might begin to rise from the floor with the rush of excitement, the wonderful elation: dizzying, intoxicating, triumphant…. It was as if she’d been grabbed by something out of the sky, and pulled up; she was going higher and higher.

In that state, Helen tells Edgar he’s getting Dolly back only if he makes a “real stud” for her.

It’s deeply satisfying to watch Helen assert herself over Edgar, but Ingalls—here and throughout her work—does not rest on that satisfaction. She seems to delight in dipping into the minds of the awful husbands she writes. In the Act visits Edgar’s as he works night and day on sex robot #2, fuming all the while about Helen’s bad moods, her lackluster cooking, her tendency to “wear really dumpy clothes that he didn’t like.” It offends him to “be so hard at work, wasting the strength of his body and brain on the creation of a thing intended to give her pleasure.” But it offends him even more when, after a weekend with her doll, Helen informs him that she’s bored. In bed, the male robot, whom she names Automatico—Auto for short—is “without subtlety, charm, surprise, or even much variety. She didn’t believe that her husband had tried to shortchange her; he simply hadn’t had the ingenuity to program a better model.”

Helen asks Edgar to improve Auto, but after days back in the lab, the doll still fails to impress. “Perhaps no alterations would make any difference,” Ingalls writes. “Maybe [Helen] just wanted him to be real, even if he was boring. Edgar evidently felt the other way…. The element of fantasy stimulated him.” It speaks to Ingalls’s attitudes about both gender and imagination that the former doesn’t enter the equation here. Helen doesn’t argue to herself that men need fantasy, women reality. It would hardly be consistent with Ingalls’s broader body of work if she did. Dorothy, for example, falls for Larry not just because she needs attention but because she needs the mental escape offered by letting herself love a being others wouldn’t even believe in. More importantly, though, Ingalls is not a generalizer—which is perhaps how she manages, despite the terribleness of the husbands she writes about, to remain so committed to male possibility.

In the Act’s symbol of that possibility is Ron, a musclebound petty criminal. He’s the one who steals Dolly from the train-station locker where Helen stashes her, hoping for something to sell. Instead, he gets his true love. Ron yearns for Dolly to be real. He sees her robot nature as a tragic, irremediable flaw, which he nevertheless tries to overcome. He buys her casual clothes and L.L.Bean duck boots (a rare moment of proper-noun Americana in Ingalls’s work) to replace the absurdly frilly outfit Edgar chose. He takes her on the bus, to his sister’s house, and to hang out with his gym buddies, but none of these outings succeeds in making her seem more human. Only Ron, in the privacy of his imagination, can do that.

When Helen comes into contact with Ron, she recognizes him not as a kindred spirit, but as the best sexual option on offer, bringing hope to the despair into which Auto’s failure to satisfy has plunged her. Ron is not the person Helen wants to be with, but she still instantly clocks him as “more the kind of thing I had in mind…to wind up and go to bed with.” She’s objectifying him here, of course—it’s not exactly respectful to call someone “the kind of thing I had in mind”—but what she’s attracted to is his rough humanity. Looking at him reminds her of what she wants, and what she believes she can have: sex with a human man who projects physical power, and who wants a woman rather than a doll.

In the Act doesn’t quite have a happy ending. Helen leaves the story with much more strength and self-knowledge than she has at the start, but when she realizes that she would prefer a boring real man to an inexhaustible sex robot (who, post modification, can also teach her Italian and gourmet cooking), it’s at the same moment that she accepts that her husband finds reality a turn-off. Up to a point, having a happy long-term relationship, whether it’s a marriage or not, requires wanting a real person—which, in turn, requires accepting some boredom. It is impossible to be intimate with someone over time without coming to understand them, to know their habits, to be able to predict some of what they will do and say next. Edgar and Helen both know this, but Edgar doesn’t know anything else. Helen, in contrast, recognizes the other side of the equation: with intimacy, and being known, comes the pleasure of receiving someone’s deep attention, and of paying deep attention to someone else. Martin Buber called this the I–Thou relationship; most of us just call it love.

In I See a Long Journey, one of the other novellas in No Love Lost, Ingalls writes a variation of the love story Helen dreams of. Its heroine, Flora, marries a wealthy man named James when she’s very young and grows paranoid as a result of her new economic status. James does not understand this at first, but by the time the story’s main action starts, he’s figured Flora’s anxiety out enough to both take her on vacation as a distraction and to bring along his driver, Michael, as an unofficial bodyguard, knowing the other man’s presence will enable Flora to relax. Flora’s faith in Michael’s protective abilities facilitates intimacy, physical and emotional, between Flora and James, while also ripening into its own kind of love.

Early in the vacation, before things go sideways—this is, after all, a Rachel Ingalls story—Flora and James sit at breakfast, with Michael

seated alone at a table for two several yards beyond them. Flora had them both in view, Michael and James. She felt her face beginning to smile. At that moment she couldn’t imagine herself returning from the trip.

Such contentment is nowhere in In the Act, but Helen knows she wants it. In Binstead’s Safari and Mrs. Caliban, Millie and Dorothy get flickers of it from Simba and Larry. It would be going too far to say that Flora’s off-kilter marital satisfaction is the goal toward which Ingalls’s heroines move, but it is certainly one they believe in. Her women are optimists. Romantics, too.

It may well be the case that Ingalls’s work is gaining in popularity both because female romantics are so rare in contemporary literary fiction and because her romantics are so odd. After years of two-steps-forward-one-step-back feminist progress in the United States, epitomized most recently by the overturning of Roe v. Wade, it can be tough to swallow unquestioned female longing for men in fiction, at least if you’re the sort of woman who questions your own desire. Ingalls puts interrogated longing on the page in ways both supernatural and mundane. Her style makes the former seem no stranger than the latter. Ingalls reminds her readers that desire is weird, surprising, uncontrollable, likely to end badly—and worth pursuing nonetheless.

0 notes

Text

It would be easy, if you were a person who read women often but spoke to them rarely, to imagine that contemporary women hate men. Scholars write books and essays about how tragic heterosexuality is; queer writers in and out of the academy pity straight girls, who, in turn, bemoan their fate on social media or in personal essays that go viral there.1 Some go so far as to suggest that no women genuinely enjoy heterosexual sex, but most confine themselves to the idea, or the performance of the idea, that heterosexual love is second-rate and doomed. Fiction isn’t immune. In recent literary novels like Lillian Fishman’s Acts of Service or Katherine Lin’s You Can’t Stay Here Forever, good sex between men and women abounds, but a good man is hard to find. In a March New York Times piece on the revival of Norman Rush’s 1991 novel Mating, Marie Solis wrote that the book’s fans “have noted that a largely positive portrayal of love relationships in general, and heterosexual relationships in particular, is a rarity in fiction.” (Rush’s fans, evidently, are not reading romance.)

It would also be easy, if you had read about the writer Rachel Ingalls’s work but never opened one of her electrically strange short books, to see her as an early adopter of today’s men-are-trash-ism, which the writer Asa Seresin has referred to as “heteropessimism.”2 Ingalls is certainly a bard of what John Updike, describing her 1983 novel Mrs. Caliban, called “a deep female sadness that makes us stare,” yet the madcap spirit that suffuses her writing keeps it from being fatalistic. She gravitates toward the odd aside, the baffling phenomenon, the bloody ending. But she never betrays what’s happening next in her stories—foreshadowing is unthinkable. This unpredictability is her aesthetic and philosophical hallmark.

It is true that the single strongest current running through Ingalls’s fiction is the boundary-shattering energy of female desire, which, whether satisfied or denied, she depicts as both a life-giving force and a destroyer of worlds. And when Ingalls writes about denied desire, the culprit is generally a negligent husband. Marriage is not an appealing prospect in her fiction. Consider In the Act (1987), recently reissued in the UK as part of No Love Lost, a collection of eight of her novellas,and in the US as a slim standalone. It opens with a man named Edgar telling his wife, Helen, that she’s being unreasonable. “Of course I am. I’m a woman,” Helen shoots back. “You’ve already explained that to me.”

Edgar is a great explainer. Ingalls, who is masterful at skewering her characters, writes that he wins arguments by explaining his side in a tone that is “knowing, didactic, often sarcastic or hectoring. Whenever he used it outside the house, it made him disliked.” Whether he’s liked in the house is unclear. Helen mainly seems exasperated with her husband at the beginning of In the Act, but Ingalls does let the reader know that, when he so chooses, he’s good enough in bed that Helen is both “satisfied [and] surprised.” Mainly, though, Edgar uses sex to pacify Helen so she’ll stay out of his attic lab, on which he has placed a Bluebeard-esque prohibition. When she enters anyway, she discovers that he’s been building an animatronic sex doll.

Though Edgar’s doll is highly realistic, in an idealized, pornographic way—“Pubic hair and nipples everywhere you look,” Helen sputters, describing her—Edgar betrays his fundamental lack of imagination by dressing her in the flouncy, childish clothes an expensive doll would wear and naming her Dolly. Although Edgar is a good inventor, he is, like many Ingalls husbands, a fool. However, that doesn’t mean all her men are.

Ingalls’s female protagonists share an instinctive faith that, no matter how disappointing their men are, better ones are out there. For them, men are often a dream, a repository and symbol of hope that goes far beyond the sexual. Crucially, that hope is often met, though rarely in the way one would expect (or, in some cases, want). Patricia Lockwood writes in her foreword to No Love Lost that the word “man” “shines in her writing the way the word ‘shop’ does: a place to walk into, spin around till your skirt flares and at last get everything you want.” Lockwood’s description captures the 1950s tenor of Ingalls’s work, but the truth is, nobody in an Ingalls story is longing for stuff. For her women, getting everything you want is an emotional prospect. They long for pure and sustained male attention paid equally to their bodies and their minds. When they get it, it brings them back to life.

Ingalls herself lived, as far as anyone knows, a peaceful life: she was not one for interviews or press. She was born in Massachusetts in 1940; her father was a Harvard Sanskrit professor, and her mother, like so many of Ingalls’s protagonists, stayed home. After graduating from Radcliffe in 1964, Ingalls moved to England, where she wrote in relative obscurity until 1986, when the British Book Marketing Council surprised readers by naming her Mrs. Caliban one of the twenty best postwar novels by American writers.

Mrs. Caliban is very short—hardly long enough to qualify as a novel rather than a novella—and, like many of Ingalls’s works, feels distinctly American despite her expatriation: it is set in an unspecified suburb that feels Southern Californian, a place where cars, malls, and chitchat rule. At the book’s start, a lonely housewife named Dorothy is grieving the death of her son, Scotty, years ago, as well as a subsequent miscarriage; then her poor little dog, Bingo, was killed by a car, leaving Dorothy feeling that “everything near her died…. It was a wonder the grass on the front lawn didn’t turn around and sink back into the earth.” Her husband, Fred, a callous jerk at the best of times, withdraws from her grief. Dorothy’s misery is so flattening and absolute that she is, as she tells her friend Estelle, “too unhappy to get a divorce.” She is not, however, too morose to start a steamy affair with a giant humanoid frog.

Larry, Mrs. Caliban’s frog-man, turns up at Dorothy’s house in need of shelter. He’s on the run, having killed a pair of sadistic scientists who captured him in the Gulf of Mexico and performed experiments on him. Dorothy takes Larry in without a second thought. Before long, she’s teaching him how to sleep with a human woman, which seems uncomplicated, since his body is “exactly like [that of] a man—a well-built large man—except that he was a dark spotted green-brown in colour.” Larry and Dorothy fall in love, about which the novel leaves no room for doubt: this is a good thing, and readers should root for it. Yes, Larry has webbed hands and feet and his true home is under the ocean, but his species is far less important than his effect on Dorothy. Once she and Larry get together, she lights up almost instantly. She’s sneaking around the suburbs with him at night, sewing gigantic wigs for him by day to disguise his green head when he goes out. She’s having a great time, and it’s lucky for both her and Larry that Fred is too oblivious to notice.

Ingalls writes Mrs. Caliban with a breezy matter-of-factness that chimes with Dorothy’s desire for Fred to keep looking away from her new happiness, from their guest room where Larry is staying, from the sacks of avocados—Larry’s pricey favorite snack—that she’s suddenly buying. The novella’s tone all but shouts, “Nothing to see here!” Her writing does not invite readers to slow down. But her sentences reward anyone who has the willpower to pause. In one of the very few moments when Dorothy herself stops moving, she sits on the beach, waiting for Larry to surface from a night swim in the ocean:

But down there it would be dark now, and not the lovely lighted aquarium she imagined it to be during the daylight hours, eddying with schools of tiny, delicate animals floating and dancing slowly to their own serene currents and creating the look of a living painting. That was wrong, in any case. The ocean was different from an aquarium, which was an artificial environment.

In these three sentences, beauty and fantasy give way abruptly to Dorothy’s understanding that she’s fallen for a wild creature. She can keep Larry in her guest room, but not forever. No matter how much she enjoys floating on the current of love that runs between them, he’s going to go back to the ocean someday.

Love and wildness collide again in Binstead’s Safari (1983). Millie Binstead, ignored for years by her anthropologist spouse, Stan, comes roaring into her own after starting a hot safari-town romance with a hunter and lion expert named Henry “Simba” Lewis who promises to marry her once she gets rid of her husband. Stan, a stereotypical academic, is almost constitutionally incapable of noticing things, but he realizes rapidly that Millie has made contact with a new and powerful side of herself. Mainly what he sees is the sexual wildness Lewis has awakened in her, though he recognizes it only in the form of his own sudden desperation to sleep with her after years of disinterest. He gets even hornier once she asks for a divorce. “I don’t know what you think you’re proving,” he grouses after she turns him down one morning. “I’m having wet dreams now.” Millie, whose prince is finally coming, couldn’t care less.

Binstead’s Safari is Ingalls’s longest novel, and its length allows her to contrast Millie’s relationships with both Stan and Lewis with slower forms of love that rarely appear in her shorter works. Ian, the Binsteads’ main guide, has a steady, calm relationship with his wife, Pippa; his younger colleague Nicholas, meanwhile, is quietly frantic over his wife, Jill, whose recent nervous breakdown has left her unable to care for their children. Nicholas has to keep earning but plainly longs for her. Every letter she writes sends him into a spiral of misery that Millie, herself longing for Lewis, talks him through. In one of her arguments with Stan, she holds Nicholas up as an example, saying, “Everybody thinks Jill is in a mess—at least Nicholas is on her side. What I’m trying to say is that for some reason, it made you feel good every time I failed at something.”

Millie and Lewis don’t get as far as marriage, and it’s safe to assume that, if they did, it wouldn’t be a union like either Ian and Pippa’s or Nicholas and Jill’s. Depending on how you interpret the end of Binstead’s Safari, Lewis may be a lion-god in human guise (I think he is), and myths across cultures tell us that gods and women rarely have long relationships rooted in empathy. Ingalls herself presumably agrees: in Mrs. Caliban Dorothy knows that the fact that Larry’s a frog-man means they have no long-term future. But the long term isn’t absent from Ingalls’s writing. In the Act is very much about a woman who wants an Ian-and-Pippa-style marriage. What Helen wants—what she yearns for—is sustained love, sexual connection, and affection from a real human man. She wants them so badly she’d do just about anything.

In the Act seems initially to be about artificiality, not wildness. Helen is, after all, in marital competition with a sex robot—except that the competition, once discovered, lasts less than an afternoon. Within moments of finding Dolly in her husband’s attic lab, Helen has hauled her off to a train-station storage locker, from which she will soon be stolen by a lunk named Ron (more on him later).

Helen’s fury makes her both decisive and powerful. It also releases her own wildness, though not in quite the same way the lion-god and lizard-man relationships in Binstead’s Safari and Mrs. Caliban do. Dorothy and Millie need to reencounter pleasure in a way Helen does not. She’s fully in touch with her sexuality, though anger gives it a new edge. Ingalls takes advantage of the novella form’s brevity to convey the 0-to-100 intensity of Helen’s intertwined emotions without having to tease them out. She describes Helen’s initial confrontation with Edgar about Dolly in the language of a high-quality orgasm:

She thought she might begin to rise from the floor with the rush of excitement, the wonderful elation: dizzying, intoxicating, triumphant…. It was as if she’d been grabbed by something out of the sky, and pulled up; she was going higher and higher.

In that state, Helen tells Edgar he’s getting Dolly back only if he makes a “real stud” for her.

It’s deeply satisfying to watch Helen assert herself over Edgar, but Ingalls—here and throughout her work—does not rest on that satisfaction. She seems to delight in dipping into the minds of the awful husbands she writes. In the Act visits Edgar’s as he works night and day on sex robot #2, fuming all the while about Helen’s bad moods, her lackluster cooking, her tendency to “wear really dumpy clothes that he didn’t like.” It offends him to “be so hard at work, wasting the strength of his body and brain on the creation of a thing intended to give her pleasure.” But it offends him even more when, after a weekend with her doll, Helen informs him that she’s bored. In bed, the male robot, whom she names Automatico—Auto for short—is “without subtlety, charm, surprise, or even much variety. She didn’t believe that her husband had tried to shortchange her; he simply hadn’t had the ingenuity to program a better model.”

Helen asks Edgar to improve Auto, but after days back in the lab, the doll still fails to impress. “Perhaps no alterations would make any difference,” Ingalls writes. “Maybe [Helen] just wanted him to be real, even if he was boring. Edgar evidently felt the other way…. The element of fantasy stimulated him.” It speaks to Ingalls’s attitudes about both gender and imagination that the former doesn’t enter the equation here. Helen doesn’t argue to herself that men need fantasy, women reality. It would hardly be consistent with Ingalls’s broader body of work if she did. Dorothy, for example, falls for Larry not just because she needs attention but because she needs the mental escape offered by letting herself love a being others wouldn’t even believe in. More importantly, though, Ingalls is not a generalizer—which is perhaps how she manages, despite the terribleness of the husbands she writes about, to remain so committed to male possibility.

In the Act’s symbol of that possibility is Ron, a musclebound petty criminal. He’s the one who steals Dolly from the train-station locker where Helen stashes her, hoping for something to sell. Instead, he gets his true love. Ron yearns for Dolly to be real. He sees her robot nature as a tragic, irremediable flaw, which he nevertheless tries to overcome. He buys her casual clothes and L.L.Bean duck boots (a rare moment of proper-noun Americana in Ingalls’s work) to replace the absurdly frilly outfit Edgar chose. He takes her on the bus, to his sister’s house, and to hang out with his gym buddies, but none of these outings succeeds in making her seem more human. Only Ron, in the privacy of his imagination, can do that.

When Helen comes into contact with Ron, she recognizes him not as a kindred spirit, but as the best sexual option on offer, bringing hope to the despair into which Auto’s failure to satisfy has plunged her. Ron is not the person Helen wants to be with, but she still instantly clocks him as “more the kind of thing I had in mind…to wind up and go to bed with.” She’s objectifying him here, of course—it’s not exactly respectful to call someone “the kind of thing I had in mind”—but what she’s attracted to is his rough humanity. Looking at him reminds her of what she wants, and what she believes she can have: sex with a human man who projects physical power, and who wants a woman rather than a doll.

In the Act doesn’t quite have a happy ending. Helen leaves the story with much more strength and self-knowledge than she has at the start, but when she realizes that she would prefer a boring real man to an inexhaustible sex robot (who, post modification, can also teach her Italian and gourmet cooking), it’s at the same moment that she accepts that her husband finds reality a turn-off. Up to a point, having a happy long-term relationship, whether it’s a marriage or not, requires wanting a real person—which, in turn, requires accepting some boredom. It is impossible to be intimate with someone over time without coming to understand them, to know their habits, to be able to predict some of what they will do and say next. Edgar and Helen both know this, but Edgar doesn’t know anything else. Helen, in contrast, recognizes the other side of the equation: with intimacy, and being known, comes the pleasure of receiving someone’s deep attention, and of paying deep attention to someone else. Martin Buber called this the I–Thou relationship; most of us just call it love.

In I See a Long Journey, one of the other novellas in No Love Lost, Ingalls writes a variation of the love story Helen dreams of. Its heroine, Flora, marries a wealthy man named James when she’s very young and grows paranoid as a result of her new economic status. James does not understand this at first, but by the time the story’s main action starts, he’s figured Flora’s anxiety out enough to both take her on vacation as a distraction and to bring along his driver, Michael, as an unofficial bodyguard, knowing the other man’s presence will enable Flora to relax. Flora’s faith in Michael’s protective abilities facilitates intimacy, physical and emotional, between Flora and James, while also ripening into its own kind of love.

Early in the vacation, before things go sideways—this is, after all, a Rachel Ingalls story—Flora and James sit at breakfast, with Michael

seated alone at a table for two several yards beyond them. Flora had them both in view, Michael and James. She felt her face beginning to smile. At that moment she couldn’t imagine herself returning from the trip.

Such contentment is nowhere in In the Act, but Helen knows she wants it. In Binstead’s Safari and Mrs. Caliban, Millie and Dorothy get flickers of it from Simba and Larry. It would be going too far to say that Flora’s off-kilter marital satisfaction is the goal toward which Ingalls’s heroines move, but it is certainly one they believe in. Her women are optimists. Romantics, too.

It may well be the case that Ingalls’s work is gaining in popularity both because female romantics are so rare in contemporary literary fiction and because her romantics are so odd. After years of two-steps-forward-one-step-back feminist progress in the United States, epitomized most recently by the overturning of Roe v. Wade, it can be tough to swallow unquestioned female longing for men in fiction, at least if you’re the sort of woman who questions your own desire. Ingalls puts interrogated longing on the page in ways both supernatural and mundane. Her style makes the former seem no stranger than the latter. Ingalls reminds her readers that desire is weird, surprising, uncontrollable, likely to end badly—and worth pursuing nonetheless.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Slowly reading No Love Lost, a buffet of novellas by Ingalls. I came to this book having read Mrs. Caliban and Binstead's Safari, both of which I love, so I'm backing up before I get to the first two novellas in No Love Lost. One trick of talking about Ingalls' work is not ruining the thrill that makes her work so satisfying, that sensation of discovery alongside her characters.

Mrs. Caliban: a short novel about a housewife, Dorothy, and her affair with a sea monster, Larry. I always refer to Larry as a fish-man or frog-man and in my mind he's always different, but always an aquatic lover, emerged and escaped from the waves of a scientific research institute tank, the threat of him gracing radio airwaves, his physical form manifesting in Dorothy's kitchen. They talk. They fuck. They eat avocados. The daily and mundane meets the extraordinary and stays mundane with something wild. It's not an obliteration of Dorothy's whole daily life, but something weird infusing her days and casting her life in a new light. It's beautiful, bittersweet, and its bite-sized length is a marvel in and of itself for the emotional landscape this book presents.

Binstead's Safari: a woman, Millie, joins her self-important academic husband on a journey, first to London—where she gets a life-changing makeover—and then on a safari, where she thrives. So another story of a transformer woman, this time outside home and homeland. (Part of Ingalls' appeal for me is that seismic change happens to her characters whose setting remains unchanged and those who travel far distances. You can wake up a new person in a Rachel Ingalls story, no matter whether you're at home or further than you've ever traveled.) But Binstead! Lion folklore. Quaint landscape paintings. Hot air balloon sexscapades. A lion god. I'll stop there; the thrill should be yours. But coming to this one a year-ish after first reading Mrs. Caliban, I was delighted to spend longer with Ingalls' mind and witness her work across a longer novel.

The novellas (thus far!):

Blessed Art Thou: a monk makes it with the angel Gabriel. The result is a pregnancy that jostles the monastery. Gender swapping. Medical tension, specifically related to pregnancy. Reckonings with faith. This one called to mind the short fiction of George Saunders, some Wells Tower. Short, swift, yet expansive.

In the Act: people vs. people; people vs. machines. No relationship feels sacred in this one. A woman discovers the product of her husband's secret hobby and holds it for a rebellious ransom. Desire, engineered lust, human relationships—to each other, to themselves, to technology. More Caliban than Binstead, which is to say this story has us home instead of wandering (geographically).

There's a note in my planner reading: Ingalls’ writing is sex and death and life and work. Something I jotted down fast on a lunch break. Not a comprehensive assessment of what inhabits her books. And maybe it’s something you could say for many writers—perhaps all writers whose work endures—but the journeys she takes us on were totally her own, peerless, beautifully weird.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Read 2023 (Jan-June)

Curious about what good books I've read so far this year? Cool, because I want to tell you about them. List by genre and very brief thoughts about each below. (Ratings out of 10 are how each book landed for me personally; they're not meant to be in any way objective).

SFF: Uranians - Theodore McCombs 10/10. Scifi; short story collection. Queer pasts, presents, and possible futures, populated with as many trans spaceship priests and unkillable women as you could want. Counterweight - Djuna 8/10. Scifi; short novel. Biopunk cybercrime detective mashup by South Korea's science fiction Banksy. Quick and weird and fun. The Crane Husband - Kelly Barnhill 10/10. Fantasy; short novel. Retelling of the crane wife as a dark midwestern Americana fable. Equal parts charming and distressing. The writing is utterly lovely. A Psalm for the Wild-Built and A Prayer for the Crown-Shy - Becky Chambers, both 9/10. Scifi/fantasy novellas. Nonbinary tea monk and it/its robot strike up a friendship and wander the land having pleasant adventures. I don't think I've ever read anything written with such palpable kindness and charity of spirit. A soothing, joyful read. To Be Taught, If Fortunate - Becky Chambers 10/10. Scifi; novella. Polycule who may be Earth's last astronauts go exploring among the stars. This was so beautiful it left me a sobbing mess on my couch. Light From Uncommon Stars - Ryka Aoki 9/10. Scifi/fantasy; novel. Dramatis personae: a violin teacher trying to save her soul from hell by damning her students, a runaway trans girl with otherworldly musical talents, and an alien refugee spaceship captain and her family fleeing from intergalactic war. Strange, and hard to read at points (tw: transphobia, sa) but it was lovingly constructed and a wonderful ride. Space Opera - Catherynne Valente. Currently reading, but so far I LOVE this. Like Douglas Adams dropped acid and watched The Fifth Element, then decided to invent Eurovision about it. Completely bananas. I'm in awe.

Horror: Sister, Maiden, Monster - Lucy A. Snyder 6/10. Three interconnected stories of an apocalypse that turns people into brain-eating Lovecraftian horrors. Heavy on body horror and sexual gore. Kind of "everything and the kitchen sink" writing for my tastes, but it was a good, creepifying romp if you're up for it. Monstrilio - Gerardo Samano Cordova 9/10. Literary horror. After losing a child, a mother carves out a piece of his lung and grows it into a replacement son. Impressive character writing. Tone: monstrous and tender. Desert Creatures - Kay Chronister 8/10. Postapocalyptic Southwestern desert wasteland wandering. Very "The Last of Us" vibes. Camp Damascus - Chuck Tingle 9/10. Short novel. Tonally, I imagine this story is what you would get if "Hellraiser" and "But I'm a Cheerleader" had a fanfic baby. A quick, fun read. Saluting you, Mr. Tingle.

Fiction: Idol, Burning - Rin Usami 8/10. Short novel. Exploration of pop idol culture and teenage obsession. A solid addition to the "fandom culture required reading" list. Cursed Bread - Sophie Mackintosh 9/10. Historical fiction, technically, about a town that suffered mass poisoning and hallucinations after WWII, told from the POV of the baker's wife. A story about desire and shame, and the ways in which they can rot a person from the inside out. I only wish I could write obsession like this. Mrs. Caliban - Rachel Ingalls 8/10. Novella. 1980s precursor to "The Shape of Water" (though they apparently aren't related): housewife falls in love with frog man. Subtle but haunting. The Fifth Wound - Aurora Mattia 10/10. My new favorite book! God this was good. Lyrical trans life, full of joy and pain and love and the most gorgeously-rendered language. I could not put this down, and keep recommending it to everybody. The Museum of Human History - Rebekah Bergman 7/10. Story about what it means to stop living: to be in a coma, to lose your memory, to cease to age. Kind of lacking in direction; wandering but pretty. House Gone Quiet - Kelsey Norris 9/10. Short story collection. Each of these stories, in its own way, dredges up all the guilt and wonder and nostalgia of the family/community/hometown left behind. "Her Body and Other Parties"-type of energy. This is a debut collection, and I'm really looking forward to seeing what the author does next. Piranesi - Susanna Clarke 8/10. Surrealist story about a man with no memory trapped under mysterious circumstances in an infinite, labyrinthine house filled with the sea. This deserved all the rave reviews that it got. Nightbitch - Rachel Yoder 9/10. A story about a woman who is convinced she's transforming into a dog: about reconciling what it is to be an artist and a mother, to be messy and animal and human, full of love and rage. I don't normally connect with stories so intimately tied up in motherhood, but this one goes for the throat. Loved. Bliss Montage - Ling Ma 8/10. Short story collection. Speculative fiction in a realist way? Happy, in an intensely lonely way? Hard to pin down, but worth taking the time to try.

Poetry: Judas Goat - Gabrielle Bates 9/10. I originally picked this up while I was receiving books at the store, flipped to a random page, read a paragraph, and muttered "Jesus Christ fuck" so loudly that my coworkers were concerned 💀 That pretty much sums up my feelings on this collection: velvety in a gothic sort of way, sharp and unkind: not in the way of a butcher's knife, but in the way of an amputation. The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On - Franny Choi 9/10. Poems for surviving your daily dystopia with acceptance and hope. Mad Honey Symposium - Sally Wen Mao 9/10. Lush, sticky, verdant language with phenomenal rhythm. The written equivalent of being dropped into a greenhouse in which much of the vegetation is carnivorous.

Graphica: Night Eaters: She Eats the Night - Marjorie Liu & Sana Takeda 9/10. The first in a new trilogy by the creators of "Monstress." Signature quality from both author and artist on display here, with a darker premise about family, inheritance, and the dangers of both. Gender Queer - Maia Kobabe 9/10. If I could change one thing about the way I grew up, I would wish to have had this book, or something like it, 20 years ago.

As usual, please feel free to creep into my dms or asks if you've read any of these and want to talk about them, or have been reading your own cool stuff. I will literally always want to hear about it.

#long post#books#fsp speaks#listen. i'm a bookseller. i am overflowing with opinions about and enthusiasm for fiction

0 notes