#Prairie Rose Indian Reservation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

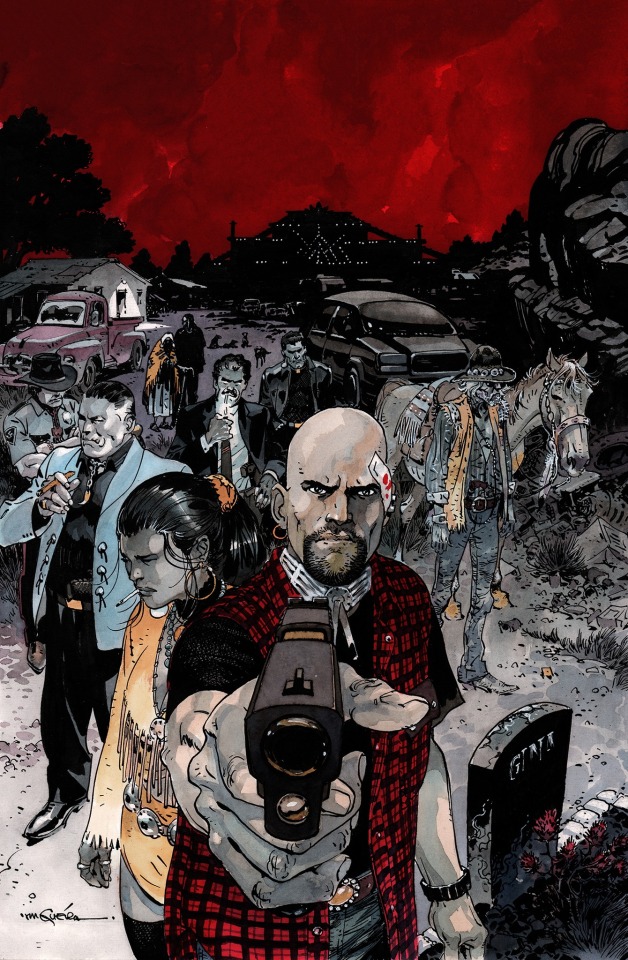

2015's Scalped: The Deluxe Edition Vol.1 HC coverby artist R.M. Guéra (featuring the badass main character Dash Bad Horse). Also used several years before as the cover of Scalped Tome 1 - Pays Indien (published in 2012 by the French publisher Urban Comics).

#Scalped#Dash Bad Horse#native american#nunchaku#undercover#comics#DC#dc comics#vertigo comics#cover#art#10s#Scalped by Jason Aaron & R.M. Guéra#cover art#Jason Aaron#Urban Comics#great run#crime comics#Dashiell “Dash” Bad Horse#Prairie Rose Indian Reservation#fbi agent#crazy horse#comic books#deluxe edition#vertigo imprint#2010s comics#comic art#cool cover art#cool comic art#great comics

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SCALPED no.1 • cover / interior art • R.M. Guera [Jan 2007]

Fifteen years ago, Dashiell "Dash" Bad Horse ran away from a life of abject poverty and utter hopelessness on the Prairie Rose Indian Reservation in hopes of finding something better. Now, he's come back home to find nothing much has changed on "The Rez" —short of a glimmering new casino, and a once-proud people overcome by drugs and organized crime. So is he back to set things right or just get a piece of the action?

Also at the center of the storm is Tribal Leader Lincoln Red Crow, a former "Red Power" activist turned burgeoning crime boss who figures that after 100 years of the Lakota being robbed and murdered by the white man, it's now time to return the favor.

Now Dash—armed with nothing but a set of nunchucks, a hellbent-for-leather attitude and (at least) one dark secret—must survive a world of gambling, gunfights, G-men, Dawg Soldierz, massacres, meth labs, trashy sex, fry bread, Indian pride, Thunder Beings, the rugged beauty of the Badlands . . . and even a brutal scalping or two.

For a dose of Sopranos-style organized crime drama mixed with current Native American culture, look no further than SCALPED!

[w] Jason Aaron • [art] R.M. Guera

$2.99 US On Sale Date: Wednesday—January 3rd 2007

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

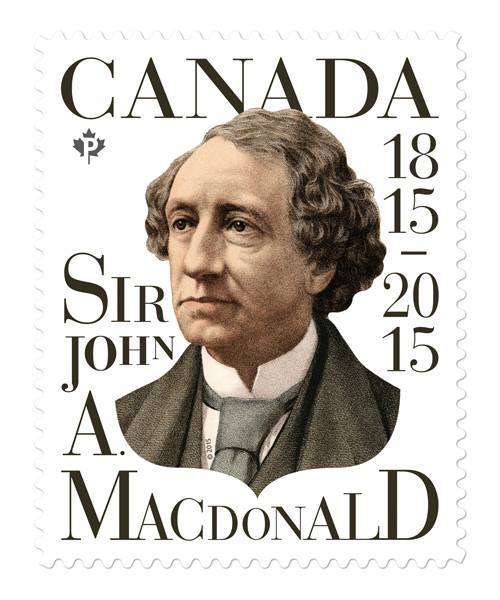

On June 6th 1891, Sir John MacDonald, the Scottish-born Canadian statesman, died.

John MacDonald was born in Glasgow, the son of a merchant who migrated to British North America in 1820. The family settled in the Kingston area of what is now Ontario, and Macdonald was educated in Kingston and Adolphustown. In 1830 he was articled to a prospering lawyer with connections that were to prove helpful to Macdonald, who rose rapidly in his profession.

MacDonald is considered to be the architect of the Confederation of Canada and served twice as the first Prime Minister of the unified Dominion, between 1867-73 and 1878-91.

Already an experienced local politician, he helped form the 1854 coalition with Upper Canadian reformers and French Canadians, creating the Liberal-Conservative Party. Within this coalition government, Macdonald was promoted to be attorney-general, and later acted as co-premier between 1856 and 1862. In 1864, MacDonald accepted that constitutional change was necessary for Canada, and spent that summer preparing proposals for a Confederation.

He was a leading delegate at all three Confederation conferences, and was knighted for his work towards union. The stamp you see in pic two was issued to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth in January 2015.

MacDonald undoubtedly laid the foundations of modern Canada, but he also personally set in motion all the most damaging elements of Canadian Indigenous policy.

It has been said that Macdonald basically had Indigenous people locked down so tightly that they became irrelevant after 1885. When Macdonald took office for the second time in 1878, the plains were in the grip of what is still one of the worst human disasters in Canadian history.

The sudden disappearance of the bison, caused largely by American overhunting, had robbed Plains First Nations of their primary source of food, clothing and shelter. Suddenly, all across the prairies were scenes reminiscent of the Irish Potato Famine only 30 years prior.

Around what is now Calgary, Blackfoot had been reduced to eating grass. White travellers described coming across landscapes of up to 1,000 Indigenous so starved that they had trouble walking.

Macdonald did not cause the famine. Nor did he draft the Indian Act or most of the West’s treaties, which had been created under the prior Liberal government but he did capitalise on prairies wracked with famine.

Macdonald’s Indian agents explicitly withheld food in order to drive bands onto reserve and out of the way of the railroad, another source tells us that his policy towards the native population was driven by submission and starvation.

We can't overlook things like this, and I personally try to give a two sided view when putting these posts together.

Under his, and other governments control the plains people's population fell by about a third.

After a failed rebellion MacDonald wrote....“The executions of the Indians … ought to convince the Red Man that the White Man governs,”

He was however a man of contraries, and in one way Macdonald was oddly more progressive on Indigenous policy than his contemporaries.

On the eve of the North-West Rebellion, he had proposed a measure that would extend voting rights to Canadian Indigenous — a measure that Canada wouldn’t actually adopt until 1960. He wrote “I hope to see some day the Indian race represented by one of themselves on the floor of the House of Commons,”.

In a particularly remarkable quote from 1880, Macdonald did something that would be quite familiar to the Canadians of 2018: He disparaged his forebears for the awful plight of Canada’s first peoples.

“We must remember that they are the original owners of the soil, of which they have been dispossessed by the covetousness or ambition of our ancestors,” he wrote in a letter proposing the creation of the Department of Indian Affairs.

“At all events, the Indians have been great sufferers by the discovery of America and the transfer to it of a large white population.” so he knew what he was doing and how it came about, again it shows how contrary he was.

Defenders of Macdonald contend that he was merely guilty of negligence. He was a man in his 60s heading up a shaky new country while simultaneously orchestrating one of history’s largest infrastructure projects. The fate of whole peoples was in the hands of a man who had no idea what the West even looked like, and had no time to care.

Macdonald won the 1891 Canadian General Election and started his sixth term as Prime Minister. However he then suffered a severe stroke, and died a week later on 6 June 1891. His state funeral was held on 9th June, and he is buried in Cataraqui Cemetery in Kingston, Ontario.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SCALPED OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 (MR)

Fifteen years ago, Dashiell Dash Bad Horse ran away from a life of abject poverty and utter hopelessness on the Prairie Rose Indian Reservation. Now he’s come home to a glimmering new casino and a once-proud people overcome by drugs and organized crime. Is he here to set things right or just get a piece of the action? Collects SCALPED #1-29, an extensive behind-the-scenes gallery, and a brand-new…

0 notes

Text

thinking about cottagecore and little house on the prairie and the libertarian myth of homesteading (which, in addition to being the actual literal definition of colonialism, is borderline impossible to do successfully - laura ingalls wilder’s family moved around so much because their farms kept failing)

& from her wikipedia page:

When she was two years old, Ingalls Wilder moved with her family from Wisconsin in 1869. After stopping in Rothville, Missouri, they settled in the Indian country of Kansas, near modern day Independence, Kansas. Her younger sister, Carrie, was born in Independence in August 1870, not long before they moved again. According to Ingalls Wilder, her father Charles Ingalls had been told that the location would be open to white settlers, but when they arrived this was not the case. The Ingalls family had no legal right to occupy their homestead because it was on the Osage Indian reservation. They had just begun to farm when they heard rumors that settlers would be evicted, so they left in the spring of 1871. Although in her novel, Little House on the Prairie, and Pioneer Girl memoir, Ingalls Wilder portrayed their departure as being prompted by rumors of eviction, she also noted that her parents needed to recover their Wisconsin land because the buyer had not paid the mortgage.[12]

& her daughter, rose wilder lane, who edited her books, literally helped found american libertarianism

there’s some more info here: https://bookriot.com/the-weird-libertarian-trojan-horse-that-is-the-little-house-books/

i know other people have written more extensively about the little house books and propaganda that was designed to encourage white settlers to homestead but it really feels like a direct line into cottagecore/homesteading tumblr

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historically false.

General Grant, by then President, along with Generals Sherman and Sheridan were faced with what they considered the “Indian Problem”. They realized as military men you could control the enemy by cutting off vital supplies. The Buffalo was a vital food supply to all Plains Indians.

Mgt Major-General Phillip Sheridan, the man with the task of forcing Native Americans off the Great Plains and onto reservations, had come along with them. This was a leisure hunt, but Sheridan also viewed the extermination of buffalo and his victory over the Native Americans as a single, inextricable mission––and in that sense, it could be argued that any buffalo hunt was Army business.

The Army neither had the manpower or resources to accomplish this. What did was the depression of 1873.

Buffalo were slow-grazing, four-legged bank rolls and free to anyone to hunt.

What easier way was there to make money than to chase down these ungainly beasts? Thousands of buffalo runners came, sometimes averaging 50 kills a day. They sliced their humps, skinned off the hides, tore out their tongues, and left the rest on the prairies to rot. They slaughtered so many buffalo that it flooded the market and the price dropped, which meant they had to kill more. In towns, hides rose in stacks as tall as houses. This was not the work of the Army. It was private industry. But that doesn’t mean Army officers and generals couldn’t lean back and look at it with satisfaction.

It was never official nor private policy to kill buffalo in order to control Native Americans on the plains, however, economics unwittingly accomplished it.

724 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the early twentieth century, the members of the Osage Nation became the richest people per capita in the world, after oil was discovered under their reservation, in Oklahoma. Then they began to be mysteriously murdered off. In 1923, after the death toll reached more than two dozen, the case was taken up by the Bureau of Investigation, then an obscure branch of the Justice Department, which was later renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The case was among the F.B.I.’s first major homicide investigations. After J. Edgar Hoover was appointed the bureau’s director, in 1924, he sent a team of undercover operatives, including a Native American agent, to the Osage reservation.

David Grann, a staff writer at the magazine, has spent nearly half a decade researching this submerged and sinister history. In his new book, “Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the F.B.I.,” which is being published by Doubleday, in April, he shows that the breadth of the killings was far greater than the Bureau ever exposed. This exclusive excerpt, the book’s first chapter, introduces the Osage woman and her family who became prime targets of the conspiracy.

In April, millions of tiny flowers spread over the blackjack hills and vast prairies in the Osage territory of Oklahoma. There are Johnny-jump-ups and spring beauties and little bluets. The Osage writer John Joseph Mathews observed that the galaxy of petals makes it look as if the “gods had left confetti.” In May, when coyotes howl beneath an unnervingly large moon, taller plants, such as spiderworts and black-eyed Susans, begin to creep over the tinier blooms, stealing their light and water. The necks of the smaller flowers break and their petals flutter away, and before long they are buried underground. This is why the Osage Indians refer to May as the time of the flower-killing moon.

On May 24, 1921, Mollie Burkhart, a resident of the Osage settlement town of Gray Horse, Oklahoma, began to fear that something had happened to one of her three sisters, Anna Brown. Thirty-four, and less than a year older than Mollie, Anna had disappeared three days earlier. She had often gone on “sprees,” as her family disparagingly called them: dancing and drinking with friends until dawn. But this time one night had passed, and then another, and Anna had not shown up on Mollie’s front stoop as she usually did, with her long black hair slightly frayed and her dark eyes shining like glass. When Anna came inside, she liked to slip off her shoes, and Mollie missed the comforting sound of her moving, unhurried, through the house. Instead, there was a silence as still as the plains.

Mollie had already lost her sister Minnie nearly three years earlier. Her death had come with shocking speed, and though doctors had attributed it to a “peculiar wasting illness,” Mollie harbored doubts: Minnie had been only twenty-seven and had always been in perfect health.

Like their parents, Mollie and her sisters had their names inscribed on the Osage Roll, which meant that they were among the registered members of the tribe. It also meant that they possessed a fortune. In the early eighteen-seventies, the Osage had been driven from their lands in Kansas onto a rocky, presumably worthless reservation in northeastern Oklahoma, only to discover, decades later, that this land was sitting above some of the largest oil deposits in the United States. To obtain that oil, prospectors had to pay the Osage in the form of leases and royalties. In the early twentieth century, each person on the tribal roll began receiving a quarterly check. The amount was initially for only a few dollars, but over time, as more oil was tapped, the dividends grew into the hundreds, then the thousands of dollars. And virtually every year the payments increased, like the prairie creeks that joined to form the wide, muddy Cimarron, until the tribe members had collectively accumulated millions and millions of dollars. (In 1923 alone, the tribe took in more than thirty million dollars, the equivalent today of more than four hundred million dollars.) The Osage were considered the wealthiest people per capita in the world. “Lo and behold!” the New York weekly Outlook exclaimed. “The Indian, instead of starving to death . . . enjoys a steady income that turns bankers green with envy.”

The public had become transfixed by the tribe’s prosperity, which belied the images of American Indians that could be traced back to the brutal first contact with whites—the original sin from which the country was born. Reporters tantalized their readers with stories about the “plutocratic Osage” and the “red millionaires,” with their brick-and-terra-cotta mansions and chandeliers, and with their diamond rings, fur coats, and chauffeured cars. One writer marvelled at Osage girls who attended the best boarding schools and wore sumptuous French clothing, as if “une très jolie demoiselle of the Paris boulevards had inadvertently strayed into this little reservation town.”

At the same time, reporters seized upon any signs of the traditional Osage way of life, which seemed to stir in the public’s mind visions of “wild” Indians. One article noted a “circle of expensive automobiles surrounding an open campfire, where the bronzed and brightly blanketed owners are cooking meat in the primitive style.” Another documented a party of Osage arriving at a ceremony for their dances in a private airplane—a scene that “outrivals the ability of the fictionist to portray.” Summing up the public’s attitude toward the Osage, the Washington Star said, “That lament, ‘Lo the poor Indian,’ might appropriately be revised to, ‘Ho, the rich red-skin.’ ”

Gray Horse was one of the reservation’s older settlements. These outposts—including Fairfax, a larger, neighboring town of nearly fifteen hundred people, and Pawhuska, the Osage capital, with a population of more than six thousand—seemed like fevered visions. The streets clamored with cowboys, fortune seekers, bootleggers, soothsayers, medicine men, outlaws, U.S. marshals, New York financiers, and oil magnates. Automobiles sped along paved horse trails, the smell of fuel overwhelming the scent of the prairies. Juries of crows peered down from telephone wires. There were restaurants, advertised as cafés, as well as opera houses and polo grounds.

Although Mollie didn’t spend as lavishly as some of her neighbors did, she had built a beautiful, rambling wooden house in Gray Horse near her family’s old lodge of lashed poles, woven mats, and bark. She owned several cars and had a staff of servants—the Indians’ pot-lickers, as many settlers derided these migrant workers. The servants were often black or Mexican, and in the early nineteen-twenties a visitor to the reservation expressed contempt at the sight of “even whites” performing “all the menial tasks about the house to which no Osage will stoop.”

Mollie was one of the last people to see Anna before she vanished. That day, May 21st, Mollie had risen close to dawn, a habit ingrained from when her father used to pray every morning to the sun. She was accustomed to the chorus of meadowlarks and sandpipers and prairie chickens, now overlaid with the pock-pocking of drills pounding the earth. Unlike many of her friends, who shunned Osage clothing, Mollie wrapped an Indian blanket around her shoulders. She also didn’t style her hair in a flapper bob but, instead, let her long, black hair flow over her back, revealing her striking face, with its high cheekbones and big brown eyes.

Mollie Burkhart.

Her husband, Ernest Burkhart, rose with her. A twenty-eight-year-old white man, he had the stock handsomeness of an extra in a Western picture show: short brown hair, slate-blue eyes, square chin. Only his nose disturbed the portrait; it looked as if it had taken a barroom punch or two. Growing up in Texas, the son of a poor cotton farmer, he’d been enchanted by tales of the Osage Hills—that vestige of the American frontier where cowboys and Indians were said to still roam. In 1912, at the age of nineteen, he’d packed a bag, like Huck Finn lighting out for the Territory, and went to live with his uncle, a domineering cattleman named William K. Hale, in Fairfax. “He was not the kind of a man to ask you to do something—he told you,” Ernest once said of Hale, who became his surrogate father. Though Ernest mostly ran errands for Hale, he sometimes worked as a livery driver, which is how he met Mollie, chauffeuring her around town.

Ernest had a tendency to drink moonshine and play Indian stud poker with men of ill repute, but beneath his roughness there seemed to be tenderness and a trace of insecurity, and Mollie fell in love with him. Born a speaker of Osage, Mollie had learned some English in school; nevertheless, Ernest studied her native language until he could talk with her in it. She suffered from diabetes, and he cared for her when her joints ached and her stomach burned with hunger. After he heard that another man had affections for her, he muttered that he couldn’t live without her.

Ernest Burkhart.

It wasn’t easy for them to marry. Ernest’s roughneck friends ridiculed him for being a “squaw man.” And though Mollie’s three sisters had wed white men, she felt a responsibility to have an arranged Osage marriage, the way her parents had. Still, Mollie, whose family practiced a mixture of Osage and Catholic beliefs, couldn’t understand why God would let her find love, only to then take it away from her. So, in 1917, she and Ernest exchanged rings, vowing to love each other till eternity.

By 1921, they had a daughter, Elizabeth, who was two years old, and a son, James, who was eight months old and nicknamed Cowboy. Mollie also tended to her aging mother, Lizzie, who had moved in to the house after Mollie’s father passed away. Because of Mollie’s diabetes, Lizzie once feared that she would die young, and beseeched her other children to take care of her. In truth, Mollie was the one who looked after all of them.

May 21st was supposed to be a delightful day for Mollie. She liked to entertain guests and was hosting a small luncheon. After getting dressed, she fed the children. Cowboy often had terrible earaches, and she’d blow in his ears until he stopped crying. Mollie kept her home in meticulous order, and she issued instructions to her servants as the house stirred, everyone bustling about—except Lizzie, who’d fallen ill and stayed in bed. Mollie asked Ernest to ring Anna and see if she’d come over to help tend to Lizzie for a change. Anna, as the oldest child in the family, held a special status in their mother’s eyes, and even though Mollie took care of Lizzie, Anna, in spite of her tempestuousness, was the one her mother spoiled.

When Ernest told Anna that her mama needed her, she promised to take a taxi straight there, and she arrived shortly afterward, dressed in bright red shoes, a skirt, and a matching Indian blanket; in her hand was an alligator purse. Before entering, she’d hastily combed her windblown hair and powdered her face. Mollie noticed, however, that her gait was unsteady, her words slurred. Anna was drunk.

Mollie (right) with her sisters Anna (center) and Minnie.

Mollie couldn’t hide her displeasure. Some of the guests had already arrived. Among them were two of Ernest’s brothers, Bryan and Horace Burkhart, who, lured by black gold, had moved to Osage County, often assisting Hale on his ranch. One of Ernest’s aunts, who spewed racist notions about Indians, was also visiting, and the last thing Mollie needed was for Anna to stir up the old goat.

Anna slipped off her shoes and began to make a scene. She took a flask from her bag and opened it, releasing the pungent smell of bootleg whiskey. Insisting that she needed to drain the flask before the authorities caught her—it was a year into nationwide Prohibition—she offered the guests a swig of what she called the best white mule.

Mollie knew that Anna had been very troubled of late. She’d recently divorced her husband, a settler named Oda Brown, who owned a livery business. Since then, she’d spent more and more time in the reservation’s tumultuous boomtowns, which had sprung up to house and entertain oil workers—towns like Whizbang, where, it was said, people whizzed all day and banged all night. “All the forces of dissipation and evil are here found,” a U.S. government official reported. “Gambling, drinking, adultery, lying, thieving, murdering.” Anna had become entranced by the places at the dark ends of the streets: the establishments that seemed proper on the exterior but contained hidden rooms filled with glittering bottles of moonshine. One of Anna’s servants later told the authorities that Anna was someone who drank a lot of whiskey and had “very loose morals with white men.”

At Mollie’s house, Anna began to flirt with Ernest’s younger brother, Bryan, whom she’d sometimes dated. He was more brooding than Ernest and had inscrutable yellow-flecked eyes and thinning hair that he wore slicked back. A lawman who knew him described him as a little roustabout. When Bryan asked one of the servants at the luncheon if she’d go to a dance with him that night, Anna said that if he fooled around with another woman, she’d kill him.

Meanwhile, Ernest’s aunt was muttering, loud enough for all to hear, about how mortified she was that her nephew had married a redskin. It was easy for Mollie to subtly strike back because one of the servants attending to the aunt was white—a blunt reminder of the town’s social order.

Anna continued raising Cain. She fought with the guests, fought with her mother, fought with Mollie. “She was drinking and quarrelling,” a servant later told authorities. “I couldn’t understand her language, but they were quarrelling.” The servant added, “They had an awful time with Anna, and I was afraid.”

That evening, Mollie planned to look after her mother, while Ernest took the guests into Fairfax, five miles to the northwest, to meet Hale and see “Bringing Up Father,” a touring musical about a poor Irish immigrant who wins a million-dollar sweepstakes and struggles to assimilate into high society. Bryan, who’d put on a cowboy hat, his catlike eyes peering out from under the brim, offered to drop Anna off at her house.

Before they left, Mollie washed Anna’s clothes, gave her some food to eat, and made sure that she’d sobered up enough that Mollie could glimpse her sister as her usual self, bright and charming. They lingered together, sharing a moment of calm and reconciliation. Then Anna said goodbye, a gold filling flashing through her smile.

With each passing night, Mollie grew more anxious. Bryan insisted that he’d taken Anna straight home and dropped her off before heading to the show. After the third night, Mollie, in her quiet but forceful way, pressed everyone into action. She dispatched Ernest to check on Anna’s house. Ernest jiggled the knob to her front door—it was locked. From the window, the rooms inside appeared dark and deserted.

Ernest stood there alone in the heat. A few days earlier, a cool rain shower had dusted the earth, but afterward the sun’s rays beat down mercilessly through the blackjack trees. This time of year, heat blurred the prairies and made the tall grass creak underfoot. In the distance, through the shimmering light, one could see the skeletal frames of derricks.

Anna’s head servant, who lived next door, came out, and Ernest asked her, “Do you know where Anna is?”

Before the shower, the servant said, she’d stopped by Anna’s house to close any open windows. “I thought the rain would blow in,” she explained. But the door was locked, and there was no sign of Anna. She was gone.

News of her absence coursed through the boomtowns, travelling from porch to porch, from store to store. Fuelling the unease were reports that another Osage, Charles Whitehorn, had vanished a week before Anna had. Genial and witty, the thirty-year-old Whitehorn was married to a woman who was part white, part Cheyenne. A local newspaper noted that he was “popular among both the whites and the members of his own tribe.” On May 14th, he’d left his home, in the southwestern part of the reservation, for Pawhuska. He never returned.

Still, there was reason for Mollie not to panic. It was conceivable that Anna had slipped out after Bryan had dropped her off and headed to Oklahoma City or across the border to incandescent Kansas City. Perhaps she was dancing in one of those jazz clubs she liked to visit, oblivious of the chaos she’d left trailing in her wake. And even if Anna had run into trouble, she knew how to protect herself: she often carried a small pistol in her alligator purse. She’ll be back home soon, Ernest reassured Mollie.

A week after Anna disappeared, an oil worker was on a hill a mile north of downtown Pawhuska when he noticed something poking out of the brush near the base of a derrick. The worker came closer. It was a rotting corpse; between the eyes were two bullet holes. The victim had been shot, execution-style.

It was hot and wet and loud on the hillside. Drills shook the earth as they bore through the limestone sediment; derricks swung their large clawing arms back and forth. Other people gathered around the body, which was so badly decomposed that it was impossible to identify. One of the pockets held a letter. Someone pulled it out, straightening the paper, and read it. The letter was addressed to Whitehorn, and that’s how they first knew it was him.

Around the same time, a man was squirrel hunting by Three Mile Creek, near Fairfax, with his teen-age son and a friend. While the two men were getting a drink of water from a creek, the boy spotted a squirrel and pulled the trigger. There was a burst of heat and light, and the boy watched as the squirrel was hit and began to tumble lifelessly over the edge of a ravine. He chased after it, making his way down a steep wooded slope and into a gulch where the air was thicker and where he could hear the murmuring of the creek. He found the squirrel and picked it up. Then he screamed, “Oh, Papa!” By the time his father reached him, the boy had crawled onto a rock. He gestured toward the mossy edge of the creek and said, “A dead person.”

There was the bloated and decomposing body of what appeared to be an American Indian woman: she was on her back, with her hair twisted in the mud and her vacant eyes facing the sky. Worms were eating at the corpse.

The men and the boy hurried out of the ravine and raced on their horse-drawn wagon through the prairie, dust swirling around them. When they reached Fairfax’s main street, they couldn’t find any lawmen, so they stopped at the Big Hill Trading Company, a large general store that had an undertaking business as well. They told the proprietor, Scott Mathis, what had happened, and he alerted his undertaker, who went with several men to the creek. There they rolled the body onto a wagon seat and, with a rope, dragged it to the top of the ravine, then laid it inside a wooden box, in the shade of a blackjack tree. When the undertaker covered the bloated corpse with salt and ice, it began to shrink as if the last bit of life were leaking out. The undertaker tried to determine if the woman was Anna Brown, whom he’d known. “The body was decomposed and swollen almost to the point of bursting and very malodorous,” he later recalled, adding, “It was as black as a nigger.” He and the other men couldn’t make an identification. But Mathis, who managed Anna’s financial affairs, contacted Mollie, and she led a grim procession toward the creek that included Ernest, Bryan, Mollie’s sister Rita, and Rita’s husband, Bill Smith. Many who knew Anna followed them, along with the morbidly curious. Kelsie Morrison, one of the county’s most notorious bootleggers and dope peddlers, came with his Osage wife.

Mollie and Rita arrived and stepped close to the body. The stench was overwhelming. Vultures circled obscenely in the sky. It was hard for Mollie and Rita to discern if the face was Anna’s—there was virtually nothing left of it—but they recognized her Indian blanket and the clothes that Mollie had washed for her. Then Rita’s husband, Bill, took a stick and pried open her mouth, and they could see Anna’s gold fillings. “That is sure enough Anna,” Bill said.

Rita began to weep, and her husband led her away. Eventually, Mollie mouthed the word “yes”—it was Anna. Mollie was the one in the family who always maintained her composure, and she now retreated from the creek with Ernest, leaving behind the first hint of the darkness that threatened to destroy not only her family but her tribe.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

2007's Scalped Vol. 1 #1 cover by cover artist Jock/Mark Simpson.

#Scalped#Jock#Dash Bad Horse#native american#comics#dc comics#DC#Jason Aaron#cover art#R.M. Guéra#Scalped by Jason Aaron & R.M. Guéra#vertigo#vertigo imprint#vertigo comics#cool comic art#2000s#nunchucks#comic books#native americans#2000s comics#crime comics#Prairie Rose Indian Reservation#south dakota#process#indian country#crime#USA#america#great comics#art

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On June 6th 1891, Sir John MacDonald, the Scottish-born Canadian statesman, died.

John MacDonald was born in Glasgow, the son of a merchant who migrated to British North America in 1820. The family settled in the Kingston area of what is now Ontario, and Macdonald was educated in Kingston and Adolphustown. In 1830 he was articled to a prospering lawyer with connections that were to prove helpful to Macdonald, who rose rapidly in his profession.

MacDonald is considered to be the architect of the Confederation of Canada and served twice as the first Prime Minister of the unified Dominion, between 1867-73 and 1878-91.

Already an experienced local politician, he helped form the 1854 coalition with Upper Canadian reformers and French Canadians, creating the Liberal-Conservative Party. Within this coalition government, Macdonald was promoted to be attorney-general, and later acted as co-premier between 1856 and 1862. In 1864, MacDonald accepted that constitutional change was necessary for Canada, and spent that summer preparing proposals for a Confederation.

He was a leading delegate at all three Confederation conferences, and was knighted for his work towards union. The stamp you see in pic two was issued to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth in January 2015.

MacDonald undoubtedly laid the foundations of modern Canada, but he also personally set in motion all the most damaging elements of Canadian Indigenous policy.

It has been said that Macdonald basically had Indigenous people locked down so tightly that they became irrelevant after 1885. When Macdonald took office for the second time in 1878, the plains were in the grip of what is still one of the worst human disasters in Canadian history.

The sudden disappearance of the bison, caused largely by American overhunting, had robbed Plains First Nations of their primary source of food, clothing and shelter. Suddenly, all across the prairies were scenes reminiscent of the Irish Potato Famine only 30 years prior.

Around what is now Calgary, Blackfoot had been reduced to eating grass. White travellers described coming across landscapes of up to 1,000 Indigenous so starved that they had trouble walking.

Macdonald did not cause the famine. Nor did he draft the Indian Act or most of the West’s treaties, which had been created under the prior Liberal government but he did capitalise on prairies wracked with famine.

Macdonald’s Indian agents explicitly withheld food in order to drive bands onto reserve and out of the way of the railroad, another source tells us that his policy towards the native population was driven by submission and starvation.

We can’t overlook things like this, and I personally try to give a two sided view when putting these posts together.

Under his, and other governments control the plains people’s population fell by about a third.

After a failed rebellion MacDonald wrote….“The executions of the Indians … ought to convince the Red Man that the White Man governs,”

He was however a man of contraries, and in one way Macdonald was oddly more progressive on Indigenous policy than his contemporaries.

On the eve of the North-West Rebellion, he had proposed a measure that would extend voting rights to Canadian Indigenous — a measure that Canada wouldn’t actually adopt until 1960. He wrote “I hope to see some day the Indian race represented by one of themselves on the floor of the House of Commons,”. In a particularly remarkable quote from 1880, Macdonald did something that would be quite familiar to the Canadians of 2018: He disparaged his forebears for the awful plight of Canada’s first peoples.

“We must remember that they are the original owners of the soil, of which they have been dispossessed by the covetousness or ambition of our ancestors,” he wrote in a letter proposing the creation of the Department of Indian Affairs.

“At all events, the Indians have been great sufferers by the discovery of America and the transfer to it of a large white population.” so he knew what he was doing and how it came about, again it shows how contrary he was.

Defenders of Macdonald contend that he was merely guilty of negligence. He was a man in his 60s heading up a shaky new country while simultaneously orchestrating one of history’s largest infrastructure projects. The fate of whole peoples was in the hands of a man who had no idea what the West even looked like, and had no time to care.

Macdonald won the 1891 Canadian General Election and started his sixth term as Prime Minister. However he then suffered a severe stroke, and died a week later on 6 June 1891.

His state funeral was held on 9 June, and he is buried in Cataraqui Cemetery in Kingston, Ontario.

18 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

“Indian Sunset” - the first track on the B-side of the album Madman Across the Water (1971)

Bernie Taupin was apparently inspired to write this angry lament after visiting a Native American reservation. It tells the story of a Native American facing defeat as he fights colonizers.

Lyrics:

As I awoke this evening with the smell of wood smoke clinging Like a gentle cobweb hanging upon a painted tepee Oh I went to see my chieftain with my warlance and my woman For he told us that the yellow moon would very soon be leaving This I can't believe I said, I can't believe our warlord's dead Oh he would not leave the chosen ones to the buzzards and the soldiers guns

Oh great father of the Iroquois ever since I was young I've read the writing of the smoke and breast fed on the sound of drums I've learned to hurl the tomahawk and ride a painted pony wild To run the gauntlet of the Sioux, to make a chieftain's daughter mine

And now you ask that I should watch The red man's race be slowly crushed What kind of words are these to hear From Yellow Dog whom white man fears

I take only what is mine Lord, my pony, my squaw, and my child I can't stay to see you die, along with my tribe's pride I go to search for the yellow moon and the fathers of our sons Where the red sun sinks in the hills of gold and the healing waters run

Trampling down the prairie rose, leaving hoof tracks in the sand Those who wish to follow me, I welcome with my hands I heard from passing renegades Geronimo was dead He'd been laying down his weapons when they filled him full of lead

Now there seems no reason why I should carry on In this land that once was my land I can't find a home It's lonely and it's quiet and the horse soldiers are coming And I think it's time I strung my bow and ceased my senseless running For soon I'll find the yellow moon along with my loved ones Where the buffaloes graze in clover fields without the sound of guns

And the red sun sinks at last into the hills of gold And peace to this young warrior comes with a bullet hole

0 notes

Text

FINISHING LINE PRESS CHAPBOOK OF THE DAY:

Flat Water: Nebraska Poems by Judy Brackett Crowe

$14.99, paper

https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/flat-water-nebraska-poems-by-judy-brackett-crowe/

Judy Brackett Crowe’s stories and poems have appeared in many literary journals and anthologies. She has taught creative writing and English literature and composition at Sierra College. She is a member of the community of Writers at Squaw Valley. Born in Nebraska, she’s lived in a small town in the northern Sierra Nevada foothills for many yearss. She is married to photographer Gene Crowe, and they have 3 children and 4 grandchildren. She believes that the right words in the right places are worth a thousand pictures, and, as other writers have said, she writes to discover what she thinks.

Judy Crowe has captured in this volume a full and detailed vision of her Nebraska childhood—the one-room schoolhouse where teacher and children told stories, played games, and finally slept in piles of blankets and coats, waiting for the men to come through the snow and save them; where a little girl rode out in the mornings in the sidecar of her young uncle’s silver Indian motorcycle to keep him company on his paper route; where the cousins jumped from the barn roof into the house-high hay to see if they could fly. It’s a world long gone and never to return, and we can be grateful that on these enchanted pages, it’s been so beautifully preserved.

–Gail Rudd Entrekin, poet—Rearrangement of the Invisible

Judy Crowe‘s language is vivid and precise, leading us to each small moment in this fine collection: folding newspapers in the sidecar of an Indian motorcycle for her teenage uncle to throw on the porches in Nebraska’s dawn, his aim perfected by baseball practice; a moment of truth between chopping block, axe, and chicken. Sandhill cranes cover winter fields, the Platte River braids its way from Colorado to Missouri, prairie grasses ripple under prairie skies. In Flat Water, Judy Crowe gives us back the memories of a midwestern childhood that many know only from fiction and dreams: homely delight, black-and-white mornings, fireflies, hollyhocks, corn stubble, silence.

–Molly Fisk, poet—The More Difficult Beauty

Judy Crowe’s gorgeous poems detailing her Nebraska childhood, transport the reader to a simpler time when a little girl’s happiness is an evening on the porch swing with her grandmother, “….snapping peas, eating a few, humming along with the peas pinging in the blue speckled tin bowl…” This collection of poems is a delight for the senses; each luscious image honors her Nebraska home. Evocative, heartfelt, and deeply moving, Judy Crowe’s work invites us in. “Welcome,” it says. “Sit down and stay awhile.” This collection not only reveals but revels in a way of life now sadly gone.

–Judie Rae, poet—The Weight of Roses

PREORDER SHIPS FEBRUARY 8, 2019

RESERVE YOUR COPY TODAY

https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/flat-water-nebraska-poems-by-judy-brackett-crowe/

#poetry

0 notes

Text

South Dakota Map, Capital, Universities, History, Population, Facts

New Post has been published on https://www.usatelegraph.com/2018/south-dakota-map-capital-universities-history-population-facts/

South Dakota Map, Capital, Universities, History, Population, Facts

South Dakota is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who compose a large portion of the population and historically dominated the territory. South Dakota is the 17th most expansive, but the 5th least populous and the 5th least densely populated of the 50 United States. As the southern part of the former Dakota Territory, South Dakota became a state on November 2, 1889, simultaneously with North Dakota. Pierre is the state capital and Sioux Falls, with a population of about 174,000, is South Dakota’s largest city.

South Dakota is bordered by the states of North Dakota (to the north), Minnesota (to the east), Iowa (to the southeast), Nebraska (to the south), Wyoming (to the west), and Montana (to the northwest). The state is bisected by the Missouri River, dividing South Dakota into two geographically and socially distinct halves, known to residents as “East River” and “West River”.

Eastern South Dakota is home to most of the state’s population, and the area’s fertile soil is used to grow a variety of crops. West of the Missouri, ranching is the predominant agricultural activity, and the economy is more dependent on tourism and defense spending. Most of the Native American reservations are in West River. The Black Hills, a group of low pine-covered mountains sacred to the Sioux, are in the southwest part of the state. Mount Rushmore, a major tourist destination, is there. South Dakota has a temperate continental climate, with four distinct seasons and precipitation ranging from moderate in the east to semi-arid in the west. The state’s ecology features species typical of a North American grassland biome.

Humans have inhabited the area for several millennia, with the Sioux becoming dominant by the early 19th century. In the late 19th century, European-American settlement intensified after a gold rush in the Black Hills and the construction of railroads from the east. Encroaching miners and settlers triggered a number of Indian wars, ending with the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. Key events in the 20th century included the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, increased federal spending during the 1940s and 1950s for agriculture and defense, and an industrialization of agriculture that has reduced family farming.

While several Democratic senators have represented South Dakota for multiple terms at the federal level, the state government is largely controlled by the Republican Party, whose nominees have carried South Dakota in each of the last 13 presidential elections. Historically dominated by an agricultural economy and a rural lifestyle, South Dakota has recently sought to diversify its economy in areas to attract and retain residents. South Dakota’s history and rural character still strongly influence the state’s culture.

State of South Dakota

Flag Seal

Nickname(s): The Mount Rushmore State (official) Motto(s): Under God the people rule Official language English Demonym South Dakotan Capital Pierre Largest city Sioux Falls Largest metro Sioux Falls metropolitan area Area Ranked 17th • Total 78,116 sq mi (199,729 km2) • Width 210 miles (340 km) • Length 380 miles (610 km) • % water 1.7 • Latitude 42° 29′ N to 45° 56′ N • Longitude 96° 26′ W to 104° 03′ W Population Ranked 46th • Total 865,454 (2016 est.) • Density 11.08/sq mi (4.33/km2) Ranked 46th • Median household income $55,065 (29th) Elevation • Highest point Black Elk Peak 7,244 ft (2208 m) • Mean 2,200 ft (670 m) • Lowest point Big Stone Lake on Minnesota border[6][7] 968 ft (295 m) Before statehood Dakota Territory Admission to Union November 2, 1889 (40th) Governor Dennis Daugaard (R) Lieutenant Governor Matt Michels (R) Legislature South Dakota Legislature • Upper house Senate • Lower house House of Representatives U.S. Senators John Thune (R) Mike Rounds (R) U.S. House delegation Kristi Noem (R) (list) Time zones • eastern half Central: UTC -6/-5 • western half Mountain: UTC -7/-6 ISO 3166 US-SD Abbreviations SD, S.D., S.Dak. Website www.sd.gov

South Dakota state symbols

The Flag of South Dakota

The Seal of South Dakota

Living insignia Bird Ring-necked pheasant Fish Walleye Flower American Pasque flower Grass Western wheat grass Insect Western honeybee Mammal Coyote Tree Black Hills Spruce Inanimate insignia Beverage Milk Dance Square dance Fossil Triceratops Gemstone Fairburn agate Rock Rose quartz Soil Houdek Song “Hail, South Dakota!” Other Kuchen (state dessert) State route marker State quarter

Released in 2006

Geography

South Dakota is a state located in the north-central United States. It is usually considered to be in the Midwestern region of the country. The state can generally be divided into three geographic regions: eastern South Dakota, western South Dakota, and the Black Hills. Eastern South Dakota is lower in elevation and higher in precipitation than the western part of the state, and the Black Hills are a low, isolated mountain group in the southwestern corner of the state. Smaller sub-regions in the state include the Coteau des Prairies, Coteau du Missouri, James River Valley, the Dissected Till Plains, and the Badlands. Geologic formations in South Dakota range in age from two billion-year-old Precambrian granite in the Black Hills to glacial till deposited over the last few million years. South Dakota is the 17th-largest state in the country.

South Dakota has a humid continental climate in the east and in the Black Hills, and a semi-arid climate in the west outside of the Black Hills, featuring four very distinct seasons, and the ecology of the state features plant and animal species typical of a North American temperate grassland biome. A number of areas under the protection of the federal or state government, such as Badlands National Park, Wind Cave National Park, and Custer State Park, are located in the state.

Education

As of 2006, South Dakota has a total primary and secondary school enrollment of 136,872, with 120,278 of these students being educated in the public school system. There are 703 public schools in 168 school districts, giving South Dakota the highest number of schools per capita in the United States. The current high school graduation rate is 89.9%, and the average ACT score is 21.8, slightly above the national average of 21.1. 89.8% of the adult population has earned at least a high school diploma, and 25.8% has earned a bachelor’s degree or higher. South Dakota’s 2008 average public school teacher salary of $36,674, compared to a national average of $52,308, was the lowest in the nation. In 2007 South Dakota passed legislation modeled after Montana’s Indian Education for All Act (1999), mandating education about Native American tribal history, culture, and heritage in all the schools, from pre-school through college, in an effort to increase knowledge and appreciation about Indian culture among all residents of the state, as well as to reinforce Indian students’ understanding of their own cultures’ contributions.

The South Dakota Board of Regents, whose members are appointed by the governor, controls the six public universities in the state. South Dakota State University (SDSU), in Brookings, is the state’s largest university, with an enrollment of 12,831. The University of South Dakota (USD), in Vermillion, is the state’s oldest university, and has South Dakota’s only law school and medical school. South Dakota also has several private universities, the largest of which is Augustana College in Sioux Falls.

0 notes

Text

In which Fix, the detective, considerably furthers the interests of Phileas Fogg

Phileas Fogg found himself twenty hours behind time. Passepartout, the involuntary cause of this delay, was desperate. He had ruined his master!

At this moment the detective approached Mr. Fogg, and, looking him intently in the face, said:

"Seriously, sir, are you in great haste?"

"Quite seriously."

"I have a purpose in asking," resumed Fix. "Is it absolutely necessary that you should be in New York on the 11th, before nine o'clock in the evening, the time that the steamer leaves for Liverpool?"

"It is absolutely necessary."

"And, if your journey had not been interrupted by these Indians, you would have reached New York on the morning of the 11th?"

"Yes; with eleven hours to spare before the steamer left."

"Good! you are therefore twenty hours behind. Twelve from twenty leaves eight. You must regain eight hours. Do you wish to try to do so?"

"On foot?" asked Mr. Fogg.

"No; on a sledge," replied Fix. "On a sledge with sails. A man has proposed such a method to me."

It was the man who had spoken to Fix during the night, and whose offer he had refused.

Phileas Fogg did not reply at once; but Fix, having pointed out the man, who was walking up and down in front of the station, Mr. Fogg went up to him. An instant after, Mr. Fogg and the American, whose name was Mudge, entered a hut built just below the fort.

There Mr. Fogg examined a curious vehicle, a kind of frame on two long beams, a little raised in front like the runners of a sledge, and upon which there was room for five or six persons. A high mast was fixed on the frame, held firmly by metallic lashings, to which was attached a large brigantine sail. This mast held an iron stay upon which to hoist a jib-sail. Behind, a sort of rudder served to guide the vehicle. It was, in short, a sledge rigged like a sloop. During the winter, when the trains are blocked up by the snow, these sledges make extremely rapid journeys across the frozen plains from one station to another. Provided with more sails than a cutter, and with the wind behind them, they slip over the surface of the prairies with a speed equal if not superior to that of the express trains.

Mr. Fogg readily made a bargain with the owner of this land-craft. The wind was favourable, being fresh, and blowing from the west. The snow had hardened, and Mudge was very confident of being able to transport Mr. Fogg in a few hours to Omaha. Thence the trains eastward run frequently to Chicago and New York. It was not impossible that the lost time might yet be recovered; and such an opportunity was not to be rejected.

Not wishing to expose Aouda to the discomforts of travelling in the open air, Mr. Fogg proposed to leave her with Passepartout at Fort Kearney, the servant taking upon himself to escort her to Europe by a better route and under more favourable conditions. But Aouda refused to separate from Mr. Fogg, and Passepartout was delighted with her decision; for nothing could induce him to leave his master while Fix was with him.

It would be difficult to guess the detective's thoughts. Was this conviction shaken by Phileas Fogg's return, or did he still regard him as an exceedingly shrewd rascal, who, his journey round the world completed, would think himself absolutely safe in England? Perhaps Fix's opinion of Phileas Fogg was somewhat modified; but he was nevertheless resolved to do his duty, and to hasten the return of the whole party to England as much as possible.

At eight o'clock the sledge was ready to start. The passengers took their places on it, and wrapped themselves up closely in their travelling-cloaks. The two great sails were hoisted, and under the pressure of the wind the sledge slid over the hardened snow with a velocity of forty miles an hour.

The distance between Fort Kearney and Omaha, as the birds fly, is at most two hundred miles. If the wind held good, the distance might be traversed in five hours; if no accident happened the sledge might reach Omaha by one o'clock.

What a journey! The travellers, huddled close together, could not speak for the cold, intensified by the rapidity at which they were going. The sledge sped on as lightly as a boat over the waves. When the breeze came skimming the earth the sledge seemed to be lifted off the ground by its sails. Mudge, who was at the rudder, kept in a straight line, and by a turn of his hand checked the lurches which the vehicle had a tendency to make. All the sails were up, and the jib was so arranged as not to screen the brigantine. A top-mast was hoisted, and another jib, held out to the wind, added its force to the other sails. Although the speed could not be exactly estimated, the sledge could not be going at less than forty miles an hour.

"If nothing breaks," said Mudge, "we shall get there!"

Mr. Fogg had made it for Mudge's interest to reach Omaha within the time agreed on, by the offer of a handsome reward.

The prairie, across which the sledge was moving in a straight line, was as flat as a sea. It seemed like a vast frozen lake. The railroad which ran through this section ascended from the south-west to the north-west by Great Island, Columbus, an important Nebraska town, Schuyler, and Fremont, to Omaha. It followed throughout the right bank of the Platte River. The sledge, shortening this route, took a chord of the arc described by the railway. Mudge was not afraid of being stopped by the Platte River, because it was frozen. The road, then, was quite clear of obstacles, and Phileas Fogg had but two things to fear-- an accident to the sledge, and a change or calm in the wind.

But the breeze, far from lessening its force, blew as if to bend the mast, which, however, the metallic lashings held firmly. These lashings, like the chords of a stringed instrument, resounded as if vibrated by a violin bow. The sledge slid along in the midst of a plaintively intense melody.

"Those chords give the fifth and the octave," said Mr. Fogg.

These were the only words he uttered during the journey. Aouda, cosily packed in furs and cloaks, was sheltered as much as possible from the attacks of the freezing wind. As for Passepartout, his face was as red as the sun's disc when it sets in the mist, and he laboriously inhaled the biting air. With his natural buoyancy of spirits, he began to hope again. They would reach New York on the evening, if not on the morning, of the 11th, and there was still some chances that it would be before the steamer sailed for Liverpool.

Passepartout even felt a strong desire to grasp his ally, Fix, by the hand. He remembered that it was the detective who procured the sledge, the only means of reaching Omaha in time; but, checked by some presentiment, he kept his usual reserve. One thing, however, Passepartout would never forget, and that was the sacrifice which Mr. Fogg had made, without hesitation, to rescue him from the Sioux. Mr. Fogg had risked his fortune and his life. No! His servant would never forget that!

While each of the party was absorbed in reflections so different, the sledge flew past over the vast carpet of snow. The creeks it passed over were not perceived. Fields and streams disappeared under the uniform whiteness. The plain was absolutely deserted. Between the Union Pacific road and the branch which unites Kearney with Saint Joseph it formed a great uninhabited island. Neither village, station, nor fort appeared. From time to time they sped by some phantom-like tree, whose white skeleton twisted and rattled in the wind. Sometimes flocks of wild birds rose, or bands of gaunt, famished, ferocious prairie-wolves ran howling after the sledge. Passepartout, revolver in hand, held himself ready to fire on those which came too near. Had an accident then happened to the sledge, the travellers, attacked by these beasts, would have been in the most terrible danger; but it held on its even course, soon gained on the wolves, and ere long left the howling band at a safe distance behind.

About noon Mudge perceived by certain landmarks that he was crossing the Platte River. He said nothing, but he felt certain that he was now within twenty miles of Omaha. In less than an hour he left the rudder and furled his sails, whilst the sledge, carried forward by the great impetus the wind had given it, went on half a mile further with its sails unspread.

It stopped at last, and Mudge, pointing to a mass of roofs white with snow, said: "We have got there!"

Arrived! Arrived at the station which is in daily communication, by numerous trains, with the Atlantic seaboard!

Passepartout and Fix jumped off, stretched their stiffened limbs, and aided Mr. Fogg and the young woman to descend from the sledge. Phileas Fogg generously rewarded Mudge, whose hand Passepartout warmly grasped, and the party directed their steps to the Omaha railway station.

The Pacific Railroad proper finds its terminus at this important Nebraska town. Omaha is connected with Chicago by the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad, which runs directly east, and passes fifty stations.

A train was ready to start when Mr. Fogg and his party reached the station, and they only had time to get into the cars. They had seen nothing of Omaha; but Passepartout confessed to himself that this was not to be regretted, as they were not travelling to see the sights.

The train passed rapidly across the State of Iowa, by Council Bluffs, Des Moines, and Iowa City. During the night it crossed the Mississippi at Davenport, and by Rock Island entered Illinois. The next day, which was the 10th, at four o'clock in the evening, it reached Chicago, already risen from its ruins, and more proudly seated than ever on the borders of its beautiful Lake Michigan.

Nine hundred miles separated Chicago from New York; but trains are not wanting at Chicago. Mr. Fogg passed at once from one to the other, and the locomotive of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne, and Chicago Railway left at full speed, as if it fully comprehended that that gentleman had no time to lose. It traversed Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey like a flash, rushing through towns with antique names, some of which had streets and car-tracks, but as yet no houses. At last the Hudson came into view; and, at a quarter-past eleven in the evening of the 11th, the train stopped in the station on the right bank of the river, before the very pier of the Cunard line.

The China, for Liverpool, had started three-quarters of an hour before!

0 notes

Text

The pilot for Jason Aaron & R.M. Guéra’s Scalped TV adaptation gets some directors

Jason Aaron & R.M. Guéra’s Scalped is a superb comic. The series focuses on the Oglala Lakota inhabitants of the fictional Prairie Rose Indian Reservation in modern-day South Dakota as they grapple with organized crime, rampant poverty, drug addiction and alcoholism, local politics and the preservation of their cultural identity. The Scalped TV show is […] http://dlvr.it/NMcK0h

0 notes

Text

Scalped Omnibus Vol.1 HC cover by R. M. Guéra (released in November 2024).

#scalped#vertigo#DC#native american#crime saga#dark#despair#dc comics#dash bad horse#lincoln red crow#casino#polar#2000s#2010s#jason aaron#rm guera#prairie rose Indian reservation#cover#cover art#cool comic art#omnibus#gun#undercover cop#gangsters#anti hero

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

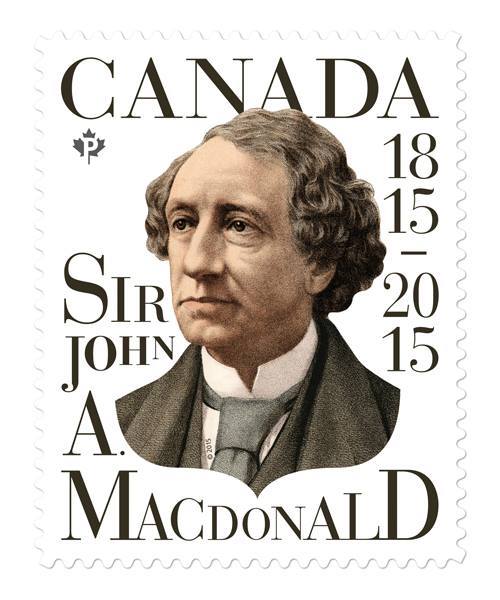

On June 6th 1891, Sir John MacDonald, the Scottish-born Canadian statesman, died.

John MacDonald was born in Glasgow, the son of a merchant who migrated to British North America in 1820. The family settled in the Kingston area of what is now Ontario, and Macdonald was educated in Kingston and Adolphustown. In 1830 he was articled to a prospering lawyer with connections that were to prove helpful to Macdonald, who rose rapidly in his profession.

MacDonald is considered to be the architect of the Confederation of Canada and served twice as the first Prime Minister of the unified Dominion, between 1867-73 and 1878-91.

Already an experienced local politician, he helped form the 1854 coalition with Upper Canadian reformers and French Canadians, creating the Liberal-Conservative Party. Within this coalition government, Macdonald was promoted to be attorney-general, and later acted as co-premier between 1856 and 1862. In 1864, MacDonald accepted that constitutional change was necessary for Canada, and spent that summer preparing proposals for a Confederation.

He was a leading delegate at all three Confederation conferences, and was knighted for his work towards union. The stamp you see in pic two was issued to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth in January 2015.

MacDonald undoubtedly laid the foundations of modern Canada, but he also personally set in motion all the most damaging elements of Canadian Indigenous policy.

It has been said that Macdonald basically had Indigenous people locked down so tightly that they became irrelevant after 1885. When Macdonald took office for the second time in 1878, the plains were in the grip of what is still one of the worst human disasters in Canadian history.

The sudden disappearance of the bison, caused largely by American overhunting, had robbed Plains First Nations of their primary source of food, clothing and shelter. Suddenly, all across the prairies were scenes reminiscent of the Irish Potato Famine only 30 years prior.

Around what is now Calgary, Blackfoot had been reduced to eating grass. White travellers described coming across landscapes of up to 1,000 Indigenous so starved that they had trouble walking.

Macdonald did not cause the famine. Nor did he draft the Indian Act or most of the West’s treaties, which had been created under the prior Liberal government but he did capitalise on prairies wracked with famine.

Macdonald’s Indian agents explicitly withheld food in order to drive bands onto reserve and out of the way of the railroad, another source tells us that his policy towards the native population was driven by submission and starvation.

We can't overlook things like this, and I personally try to give a two sided view when putting these posts together.

Under his, and other governments control the plains people's population fell by about a third.

After a failed rebellion MacDonald wrote....“The executions of the Indians … ought to convince the Red Man that the White Man governs,”

He was however a man of contraries, and in one way Macdonald was oddly more progressive on Indigenous policy than his contemporaries.

On the eve of the North-West Rebellion, he had proposed a measure that would extend voting rights to Canadian Indigenous — a measure that Canada wouldn’t actually adopt until 1960. He wrote “I hope to see some day the Indian race represented by one of themselves on the floor of the House of Commons,”. In a particularly remarkable quote from 1880, Macdonald did something that would be quite familiar to the Canadians of 2018: He disparaged his forebears for the awful plight of Canada’s first peoples.

“We must remember that they are the original owners of the soil, of which they have been dispossessed by the covetousness or ambition of our ancestors,” he wrote in a letter proposing the creation of the Department of Indian Affairs.

“At all events, the Indians have been great sufferers by the discovery of America and the transfer to it of a large white population.” so he knew what he was doing and how it came about, again it shows how contrary he was.

Defenders of Macdonald contend that he was merely guilty of negligence. He was a man in his 60s heading up a shaky new country while simultaneously orchestrating one of history’s largest infrastructure projects. The fate of whole peoples was in the hands of a man who had no idea what the West even looked like, and had no time to care.

Macdonald won the 1891 Canadian General Election and started his sixth term as Prime Minister. However he then suffered a severe stroke, and died a week later on 6 June 1891.

His state funeral was held on 9 June, and he is buried in Cataraqui Cemetery in Kingston, Ontario.

10 notes

·

View notes