#Prague City Library

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Бесконечная башня из книг Idiom от Матея Крена (Matej Kren).

В современное время люди все меньше времени уделяют чтению, - это общемировая проблема. Многие века именно книги были главным источников знаний и мудрости в мире. Сейчас эта функция все больше отходит к Интернету, но все равно лишь малая часть печатной продукции, созданной за сотни лет, имеет свой оцифрованный вариант. Впрочем, последнее не очень волнует массовое сознание – все больше людей пользуется Всемирной Сетью и все меньше библиотекой.

Обеспокоены этой тенденцией и в городской библиотеке Праги (Чехия),одном из крупнейших книгохранилищ Центральной Европы. чтобы популяризовать этот процесс, в Пражской городской библиотеке и была создана инсталляция из книг с названием Idiom. Автором ее стал словацкий художник Матей Крен (Matej Kren).

Инсталляция эта представляет собой башню, сделанную из (примерно) восьми тысяч книг на разных языках. При этом, они не приклеены, а просто стоят друг на друге. В боку этого сооружения есть специальное «окно», куда может заглянуть любой желающий. Если человек заглянет внутрь башни, куда бы он ни посмотрел, вверх или вниз, увидит бесконечный столб книг. Дело в том, что в основание и в потолок инсталляции Idiom встроены круглые зеркала. Они и создают такой эффект.

Смысл этого послания понять легко – книги дают нам бесконечное количество знаний. А посетители этой инсталляции говорят, что появляется ощущение, как у входа в другую вселенную.

The endless tower of books Idiom by Matej Kren.

Nowadays, people spend less and less time reading - this is a global problem. For many centuries, books were the main source of knowledge and wisdom in the world. Now this function is increasingly moving to the Internet, but still only a small part of the printed products created over hundreds of years has its own digitized version. However, the latter does not really worry the mass consciousness - more and more people use the World Wide Web and less and less the library.

The city library of Prague (Czech Republic), one of the largest book depositories in Central Europe, is also concerned about this trend. To popularize this process, an installation of books called Idiom was created in the Prague City Library. Its author was the Slovak artist Matej Kren.

This installation is a tower made of (approximately) eight thousand books in different languages. Moreover, they are not glued, but simply stand on top of each other. There is a special “window” on the side of this structure, where anyone can look. If a person looks inside the tower, no matter where he looks, up or down, he will see an endless column of books. The thing is that round mirrors are built into the base and ceiling of the Idiom installation. They create this effect.

The meaning of this message is easy to understand – books give us an infinite amount of knowledge. And visitors to this installation say that they feel like they are at the entrance to another universe.

Источник://kulturologia.ru/blogs/281211/15931/, /pikabu.ru/story knizhnyiy_stolb_v_prage_1442853,//vk.com/wall-935223_50287, /prohodimcy.livejournal.com/3190726.html,//www.tripadvisor.ru/Attraction_Review-g274707-d10522920-Reviews-Municipal_ Library_ Of _ Prague-Prague_Bohemia.html.

#Чехия#Прага#экскурсии#инсталляция#художник#Матей Крен#Бесконечная башня#книги#Пражская городская библиотека#фотография#czechia#Prague#excursions#installation#artist#Matej Kren#Idiom#Endless Tower#Prague City Library#books#photography

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

just finished my first wk of uni, which means it's abt time to return to studyblr after being on hiatus for years (?!?) 🥲

#ft. pics of my long-awaited trip to oxford and london!! and perhaps glimpses of prague and misc. german cities#studyblr#studying#student#dark academia#light academia#academia#oxford#university of oxford#bodleian library#library

457 notes

·

View notes

Text

📍Prague, Czech Republic

#dark academia#light academia#classical#academia aesthetic#escapism#academia#books and libraries#classic literature#books#architecture#place#travel#prague#czech republic#exterior#buildings#city#royal core#cottage core#aesthetic#aesthetics#academic#photography#artistic#mood#vibe#tumblr

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh right, did I ever mention I will be going to Prague next week? (Namely because I want to see the alchemy museum. Actually, it's all because I want to see the alchemy museum.)

#at least- the alchemy museum is what got me interested#then I realized the system's mother actually lived in prague for a bit as a teen and was also interested in going#so although we have to endure her company... it's cheaper for me. and we get along far better these days anyway#chalk thoughts#I will be taking pictures of various things wherever it is allowed#so I'll post some of those. will warn everyone however- our phone camera isn't the best. we have an android phone.#i think I would also like to visit the baroque library hall in Klementinum but I will see about that#the museum of senses is also fascinating#I believe our mother wants to (if weather so permits) visit Český Krumlow (city) so that would likely take an entire day at least#so it remains to be seen how the schedule works out

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

we shall have a summer wedding. in the city library of prague.

love when a poll says to share where youre from and everyone says their country like a normal person and then americans give you random letter codes. "im from south MN" like girl on the shelf? are you a book or perhaps a vinyl record?

#jk im gonna be honest i didnt know where it was from i just tried to find a picture that specifically had letters sticking out and this one#was the prettiest thank you city library of prague 🫶🏻 apparently 🫶🏻🫶🏻#its on my travel list actually i guess when i finally make it there ill have to check it out just for the fun of it#txt#also ngl hot as fuck to be able to tell which branch and section like OKAY way to flex but works on me ig

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

City - @black-brothers-microfic - wc: 352 - Starchaser + Wolfstar

Regulus leaned over the coffee table, tracing a delicate finger along the map spread out before them. "We have to go to Paris," he murmured, circling it with a flourish of blue ink. "I’m not missing out on the Louvre."

“Paris is a given,” Sirius replied, sprawled out on the couch with his feet propped on James’ lap. "But don’t forget Amsterdam. The bikes, the canals… the vibes." He waved his hand like it explained everything.

“I’m not cycling anywhere,” James said with a mock groan, snatching the marker from Regulus’ hand. He made a big, exaggerated X over Amsterdam, only for Sirius to grab another marker and draw a heart around it.

“Don’t be boring, Potter,” Sirius teased, giving James’ knee a nudge with his toe. "You’ll survive a little pedaling."

Regulus rolled his eyes at them, leaning back into James’ shoulder with a small smile. “Can we at least decide on the next stop after Rome?”

“Florence,” James said immediately. “It’s on the way. Art, architecture, gelato. The trifecta.”

“Florence is nice,” Remus chimed in from the armchair, where he was making a careful list of their plans in his neat handwriting. “But what about Prague? It’s romantic, Sirius,” he added with a sly smile, earning an exaggerated smirk from his boyfriend.

“Romantic, is it?” Sirius asked, sliding off the couch to sit cross-legged next to Remus. “You sure you don’t just want an excuse to drag me to more old libraries?”

“Not mutually exclusive,” Remus shot back, his smirk softening into something fond.

Regulus cleared his throat, waving the marker in the air. “Before we start arguing about libraries versus architecture, can we all agree Venice is a must?”

“Obviously,” James and Sirius said in unison, their shared grin so obnoxiously identical it made Regulus groan.

“Alright, Venice,” Remus said, writing it down. “But don’t complain when I make you all go on a gondola ride. Matching striped shirts required.”

“Oh, Merlin,” Regulus muttered, though the corner of his mouth twitched up. “We’re doomed.”

“Doomed to the best road trip ever,” Sirius corrected, tossing a pillow at his brother.

#marauders#black brothers microfic#jegulus#starchaser#wolfstar#james potter#sunseeker#regulus black#sirius black#remus lupin#microfic

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

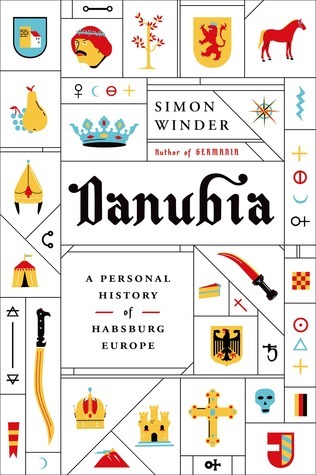

2024 Book Review #21 – Danubia by Simon Winder

I picked this up because I’ve been trying to read one history book a month, and I happened to scroll past a viral tumblr post with a quote from its introduction as I was figuring out which book that would be for April. Helpfully, there was no one ahead of me waiting for it in the library. A one-paragraph quotation and the book’s cover aside, I went it basically entirely blind. The book took a bit of adjusting to.

The book is a history of Central Europe through the lens of the Habsburg Dynasty, and it is a history of the Habsburg Dynasty through Winder’s extensive travelogue visiting every historical city and museum exhibit in the Danube basin. A roughly chronological sequence of events is followed (common and sometimes extensive tangents and diversions notwithstanding), but nearly every new section is introduced with an anecdote of visiting some town, castle or church that was relevant to the events about to be discussed, and a contemplation of its aesthetic significance to the modern traveller.

Meandering aside, the book does a good job of covering the broad sweep of a millennium of history and hits all the high points you expect it to (Charles V, Rudolph’s Prague, the 30 Years War, 1848, 1866, 1914, etc). The basic dynastic and political history is broken up and intermixed with a surprising amount of time dedicated to the cultural products of each era, which one does very much get the sense are what really fascinates Winder. The painters, composers and architects features get space that’s determined less by their general modern fame or contemporary significance and more because they happened to capture the author’s interest. I certainly came out of this with far more opinions about Vienna’s classical music output across the ages than I expected.

Winder’s voice is strong to the point of overpowering throughout. Which is quite deliberate I’m sure – this is a breezy read full of cute trivia, not a monograph – but even still, it sometimes gets a bit much. Instead of an academic lecture the effect is similar to listening to a guy whose perhaps not quite as insightful or interesting as he thinks he is hold forth over drinks in what only barely qualifies as a conversation. The effect is usually quite charming! But it does wear on you. It also makes getting particularly caught up on the precise accuracy of every bit of trivia feel kind of beside the point.

Winder is also a middle-class guy from southern England, which I might feel bad about saying ‘and you can tell’ if he didn’t bring it up himself quite so much. Anyway, knowing this makes the whole pitch of the book as ‘a walk through the age and region where all the slaving and massacres and depopulation and brutality we associate with Over There happened in Europe too” make so incredibly more sense. Even if it perhaps still shows an ever-so-slightly naive view of what preodern history also looked like in Western Europe.

Still, a significant portion of the book is dedicated to the sheer brutality of early modern religious warfare, both between the Ottomans and various Christian princes and coalitions, and between different sects of Christians. Winder thankfully has no taste at all for grand battles or heroic violence, and devotes as little wordcount to the various epoch-defining wars as he can get away with. He’s more interested in the consequences of them, the brutal and brutalizing violence that led to the depopulation and resettlement of what became the Hapsburg empire several times over across its history.

Which leads into the book’s other main theme. Winder is very much not a fan of nationalism, especially of the kind that made the region’s 20th century such an apocalypse. The book views it as an absurd horror in general, and even moreso in a region where every city and ‘national homeland’ was hopelessly intermixed, and every land continually resettled. The last chapters make the point that the ‘nationality’ of much of the population was, if not arbitrary, then certainly contingent, with massive amounts of assimiliation across national and ethnic lines happening quite late into the 19th century (and before that, historical nationality being more happenstance of language and religion that any primordial cultural essence). It is only as the Habsburg’s legitimizing mythology fell apart that nationalism became the only vital organizing force in the empire, and the grounds on which battle lines were drawn and spoils competed over.

The book does portray the whole latter 19th century as a dialectic between increasingly absurd and ineffectual but (and so) increasingly benign Hapsburg rule to the rising and inevitably exclusionary and vicious nationalisms that would tear it apart. The closest thing to the political left that makes a sustained appearance is Napoleon. Which is somewhat excusable in terms of what the post-Habsburg political situation did end up looking like, I suppose, but given the size and significance of the SDAPO it’s a bit of a gap. One more way the author shines through, I suppose.

The tragic epilogue is of course that Europe now is full of (more-or-less, if you squint) neat and semi-homogenus nation-states. Not because of any peaceful triumph of liberal nationalism and self-determination, but rather one outburst after another of apocalyptic violence, of emptied cities and gore-soaked fields. The book was written before both the current invasion of Ukraine and the most recent war in Gaza, but had either been ongoing they probably would have gotten referenced as further examples of the bloody logic of nation-building (Winder have basically categorized Zionism as the Jewish iteration of the general outburst of homeland-conquering nationalisms in later Austria-Hungary, with the Palestinians in the same unfortunate position as the inconveniently-non-Romanian Magyars in Transylvania.)

Anyway, overall a fairly charming read, and Winder’s steadfast belief that the only real justification for the Habsburg Dynasty is all the weird art they paid for is very endearing. But more entertaining than enlightening, I suppose? And if I hadn’t read it in small daily chunks Winder’s voice would have worn on me until I wanted to reach through the pages and pour a drink on him halfway through the second tangent about his family vacation in Paris.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

the City Library of Prague have recently published a series of lectures on Alternative Spirituality (or New Age) by Dr. Zuzana Kostićová and i think it's very interesting and cool. i've always been interested in this recent phenomenon of people starting to believe heavily in souls, and spirituality, and later in the series, Dr. Zuzana talks about Millenialism and Conspiracies. the lectures are in Czech and i'm assuming most of Cohost people here are Anglophones, as such, i've decided to transcribe and translate the lectures into English (which is also a good exercise for my czech learning!) which you can find in this google document. it's unfinished, as i've just begun transcribing it and it's like, 1 am, lol, but i'll try to update it and eventually translate the entire 5 hours of the series. i hope you enjoy it if you're also interested in spirituality from an academic point of view!

a pro čechů tady, držte tady odkaz na playlist na Youtube s lekcí od Zuzany.

#other stuff#late night#spirituality#alternative spirituality#translation#english translation#czech#Zuzana Kostićová#česky#čumblr#lecture#new age#esoteric#personal

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you like books and love to travel? Here are 8 stunning libraries around the world that you can add to your travel bucket list:

Strahov Monastery Library, Prague, Czech Republic: Immerse yourself in Baroque opulence as you explore two magnificent halls filled with ornate decorations, frescoes, and countless books.

Tianjin Binhai Library, Tianjin, China: A futuristic masterpiece, this library features a mesmerizing, multi-story "bookshelf" that cascades down its central atrium, creating a truly unique and inspiring space.

Alexander Library at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland: Step into a scene straight out of Harry Potter at the Long Room of this library. Towering bookcases line the walls, housing over 200,000 ancient texts.

Stuttgart City Library, Germany: A modern marvel, this library's sleek design and open-plan layout create a welcoming and inspiring atmosphere for book lovers.

New York Public Library, New York City, USA: A symbol of knowledge and culture, this iconic library's Beaux-Arts building houses millions of books, manuscripts, and other materials.

#travel#travel destinations#europe#NYC#Ireland#Germany#China#Strahov#Czech#czechia#books & libraries

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

What was read 2024

What follows is works read in the last year, in order. Some collections of poetry in here and a couple of plays. Faust is broken in two as I read the supplementary works with it & needed a breather. Just one was abandoned (Arabian Nights). One huge disappointment in Neil Gaiman's collection. Some were loaned from libraries, some were bought new, some were recommended from people I admire, some were gifts, some travelled a great distance to sit on my shelves. Most enriched, some inspired and from all something has been learned.

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle Haruki Murakami (1994)

Tender is the Flesh Agustina Bazterrica (2017)

The Mamba Mentality Kobe Bryant (2018)

The Devil’s Cup Stewart Lee Allen (2000)

Of The Farm John Updike (1965)

A Confederacy of Dunces John Kennedy Toole (1980)

Death on Credit Louis-Ferdinand Celine (1936)

Wilt Tom Sharpe (1976)

Odyssey - Homer (Samuel Butler translation 1879)

Hard Times Charles Dickens (1854)

A Good Man Is Hard to Find Flannery O’Connor (1953)

Lincoln in the Bardo George Saunders (2017)

Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel (2009)

Underworld Don DeLillo (1997)

The Turn of the Screw Henry James (1898)

The Satanic Verses Salman Rushdie (1988)

Trigger Warning Neil Gaiman (2015)

Child of God Cormac McCarthy (1973)

Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit Jeanette Winterson (1985)

The Centaur John Updike (1963)

Porterhouse Blue Tom Sharpe (1974)

Don Quixote Miguel de Cervantes (1605 & 1615) (Thomas Lathrop translation 2005)

Summer Lightning P.G. Wodehouse (1929)

Castle to Castle Louis-Ferdinand Celine (1957)

Purgatorio Dante Alighieri (~1321)

Plexus Henry Miller (1953)

Paradiso Dante Alighieri (~1321)

The Pale King David Foster Wallace (2011)

Don’t Look Now. Not after Midnight. A Border-Line Case. The Way of the Cross. The Breakthrough. Daphne du Maurier collection (1971)

Last Exit to Brooklyn Hubert Selby Jr. (1964)

The Bostonians Henry James (1886)

The Covenant James A.Michener (1980)

The Arabian Nights. Nights 1 through 10 & The story of Ali Baba and the forty thieves killed by a slave girl. Malcom C.Lyons & Ursula Lyons (2008)

Rebecca Daphne du Maurier (1938)

Faust Part I Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1808/29) Albert G. Latham translation with supplementary text 1908

The Vegetarian Han Kang (2007)

The Prague Cemetery Umberto Eco (2010)

The Stranger in the Woods Michael Finkel (2017)

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning Laurie Lee (1969)

The Exorcist William Peter Blatty (1971)

Faust Part II Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1832) Albert G. Latham translation with supplementary text 1908

The Road to Los Angeles John Fante (1985) published posthumously. (1936)

A Month in the Country J. L. Carr (1980)

The Winter’s Tale William Shakespeare (1609)

Candide Voltaire (1759)

Woke Up This Morning: The Definitive Oral History of The Sopranos Michael Imperioli and Steve Schirripa (2021)

The 120 Days of Sodom or The School of Libertinage The Marquis de Sade (1785) (published first in 1904)

UZUMAKI Spiral collection. Junji Ito (1998-99)

Vagabonding Rolf Potts (2002)

The Snows of Kilimanjaro et al Ernest Hemingway (1944)

Love Is a Dog from Hell: Poems 1974-1977 Charles Bukowski (1977)

Spring Snow Yukio Mishima (1969)

Mortality Christopher Hitchens (2012)

Disloyal A Memoir Michael Cohen (2020)

Orbital Samantha Harvey (2023)

Inside Story Martin Amis (2020)

Coleridge Poems & Prose selected by Peter Washington (1997) S.TC

The City and Its Uncertain Walls Haruki Murakami (2023)

V. Thomas Pynchon (1963)

Whiskey Words & a Shovel I R. H. Sin (2015)

Collected Poems 1938-83 Philip Larkin (1988/03)

Nexus Henry Miller (1959)

America at Middle Age Louis Galambos (1983)

Mysteries Knut Hamsun (1892)

Sylvia Plath Poems collection by C.A.Duffy (2012)

Experience Martin Amis (2000)

Sonny Boy Al Pacino (2024)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Library at Marianske Namesti in city center (Prague, Czech Republic)

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyone looking for (recent) novel recommendations, I stopped by the library a couple of days ago and picked out these two.

I haven't finished either one, but I'm enjoying both so far.

Lula Dean's Little Library of Banned Books: "Beverly Underwood and her arch enemy, Lula Dean, live in the tiny town of Troy, Georgia, where they were born and raised. Now Beverly is on the school board, and Lula has become a local celebrity by embarking on mission to rid the public libraries of all inappropriate books—none of which she’s actually read. To replace the “pornographic” books she’s challenged at the local public library, Lula starts her own lending library in front of her home: a cute wooden hutch with glass doors and neat rows of the worthy literature that she’s sure the town’s readers need.

What Lula doesn’t know is that a local troublemaker has stolen her wholesome books, removed their dust jackets, and restocked Lula’s library with banned books: literary classics, gay romances, Black history, witchy spell books, Judy Blume novels, and more. One by one, neighbors who borrow books from Lula Dean’s library find their lives changed in unexpected ways."

Parasol Against the Axe: "In Helen Oyeyemi’s joyous new novel, the Czech capital is a living thing—one that can let you in or spit you out.

For reasons of her own, Hero Tojosoa accepts an invitation she was half expected to decline, and finds herself in Prague on a bachelorette weekend hosted by her estranged friend Sofie. Little does she know she’s arrived in a city with a penchant for playing tricks on the unsuspecting. A book Hero has brought with her seems to be warping her mind: the text changes depending on when it’s being read and who’s doing the reading, revealing startling new stories of fictional Praguers past and present. Uninvited companions appear at bachelorette activities and at city landmarks, offering opinions, humor, and even a taste of treachery. When a third woman from Hero and Sofie’s past appears unexpectedly, the tensions between the friends’ different accounts of the past reach a new level."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The capital, in cooperation with the organization Prague City Tourism and the Municipal Library in Prague, symbolically launched the year of Franz Kafka on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his death.

Not only for the people of Prague, there is a program for children and adults including a number of projects with a Kafka theme. In addition to projects in the fields of film, literature, theater and music, a communication campaign was also created, which also included a specially decorated Škoda 15T tram with registration number 9310 with motifs from Kafka's life, which took to the streets of Prague this week.

https://kafka2024.de/en

#books#reading#book#bookworm#library#booklover#bookworld#czech republic#czechia#tram#franz kafka#kafka#praha#prague

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

this showed up on my fyp

tik tok's advertising prague better than i ever could (maybe bcs i hate the city fsjkjhfjks)

but yeah, winter prague is probably one of the nicest places i've seen, it's so magical when it's dark and the old lamps r shining down onto the streets and there aren't that many people around and u can really stop and look around

plus the national library and the national theatre... they're truly beautiful <33

but also U R NEVER ESCAPING CZECHIA RAAAAAAAAAAAH

#is it pretty?? yes. would i ever want to be subjected to living there?? hell fucking no.#but a trip for a few days?? v v nice hehe#(my birthplace is nicer and i will die on that hill)#mads tag <3#delicris ask

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

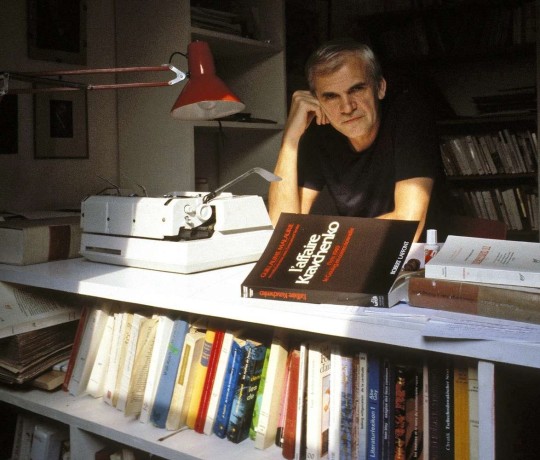

In December 1968, a plane carrying Gabriel García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes touched down in Prague. The two authors had come to show solidarity with Czechoslovakia’s writers and to discuss the year’s historic events: how the hopes of Alexander Dubcek’s Prague Spring had ebbed into the interminable autumn of the Soviet patriarch.

Their host was the Czech novelist and essayist Milan Kundera, who has died aged 94. Mindful of the need to talk freely, Kundera took his guests to a sauna, the one place in the city impossible to bug. As the steam rose and their bodies began to overheat, the visitors asked where they might sluice off the sweat. The Czech led them to a back door opening on to a hole in the frozen Vltava. He motioned towards the river and they clambered down, expecting him to follow. But Kundera remained on the bank, laughing as these hothouse flowers of Latin-American literature emerged like popsicles from the icy waters.

“The second Czech K”, as Fuentes called Kundera, in 1968 had a growing reputation as poet, dramatist, essayist and intellectual. His first novel, The Joke (turned down initially for opposing official ideology), had finally been published the year before, gaining cult success, but this moment when socialism with a human face met the “threatening fists” of power was decisive, providing not just the setting for his best known work, The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1982), but the governing theme of his oeuvre: how to be a novelist in an age when “political demagoguery has managed to ‘sentimentalise’ the will to power”.

For Kundera, who once defined himself as “a hedonist trapped in a world politicised in the extreme”, and whose novels are replete with bodily pleasures and humiliations, the lyrical intoxication of poet and revolutionary were dangerously allied. From the start, being funny was a serious business. In The Joke, a man sends a postcard with the mock salutation: “Long Live Trotsky!” The irony is lost on the censors, the result disastrous. Similarly, the stories that make up Laughable Loves (1963-68), move in a blink from farce to horror: the book was completed three days before the Russian invasion.

Like many intellectuals, Kundera was involved in the movement to create a de-Stalinised socialism. At the Fourth Congress of the Writers’ Union in 1967, Kundera gave a rallying speech arguing that Czechoslovakia’s existential precariousness (frequently overrun, its language threatened) placed it in a unique position from which to address the 20th century, but this could be relished “only [in] conditions of total freedom”.

However, after the invasion, his belief in the possibility of change unravelled: he lost “the privilege to work”, his books were removed from libraries and, by 1970 and “normalizace” – the policy of undoing Dubcˇek’s reforms – he could no longer publish.

His Kafkaesque view of power led to disagreements with the dissident playwright Václav Havel, whom Kundera attacked for encouraging the illusion of hope (“moral exhibitionism”) in a situation where history preordained defeat.

Only apart from the fray could you record your testament: this is how the novel faces power, he argued famously, with “the fight of memory against forgetting”. Havel, who remained in “the country of the weak” (as Kundera described it in The Unbearable Lightness of Being), was jailed and then fought to lead a new Czech nation in the successful Velvet Revolution, admonished him: history is not a clever divinity playing jokes on us – we are “creators of our own fate”. But Kundera had long since left the stage.

At about this time, he had started being translated abroad, a “traumatic” experience for him: he accused publishers in the west of acting like Moscow censors, when they, too, tried to “normalise” his work to fit western standards. But in 1975 he took a job in France at the University of Rennes, and four years later his Czech citizenship was revoked. He took French citizenship in 1981.

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979), the first novel to come from his exile – essayistic, multi-storied – stages a battle between devilish anti-meaning and the angelic one true idea of communism. Kundera pictures these celestial figures laughing in the face of one another, a murderous dialectic against which the writer, with his love of variety and inconclusiveness, has no defence: “the terrifying laughter of angels … covers my every word with its din”.

His writing contains much of this dark laughter, strewn with gags, pranks and paradoxes, and there are good reasons for this. He exploits the vein of black comedy that central European history gives its writers as a birthright, but more ambitiously it is humour, originating in the laughter of Boccaccio, Cervantes and Rabelais, that he sees underpinning the European novel, and which he argues, in four volumes of essays, has shaped western consciousness.

The Mexican poet Octavio Paz thought “humour … the great invention of the modern spirit”, and for Kundera nothing better disseminated this idea than the generations of novels that flowed from Cervantes, producing an art of ambiguity and polyphony. These novels gave rise to our understanding of what it is to be an individual, Kundera argued, and with this, the idea of “human rights”.

All of which perhaps explains why some critics find his writing too didactic (“all talk and no story”). For all Kundera’s engaging intelligence, John Updike also felt a “strangeness that locks us out”.

Unlike Márquez, or Salman Rushdie – the company to which Kundera aspired – there is no sign of the shaman, no risk of being thought a sham. Perhaps his refusal to fall for anything – neither politics’ nor poetry’s intoxications – his pedagogic desire to disabuse, and his view of the novel as a supremely moral and rational art, leaves Kundera, peculiarly, a novelist disinclined to enchant.

For some though, such as the writer Geoff Dyer, Kundera’s importance lies precisely in this extension of the novel into meditative interrogation, by which, Dyer thinks, he “recalibrated fiction to create forms of new knowledge”.

Born in the Moravian capital Brno, Milan was the son of Milada Janosikova and Ludvik Kundera, a pianist, composer and musicologist who was head of the Janácˇek Music Academy. The son also studied composition, and music was a lifelong love, often summoned in his novels and essays. At Charles University in Prague, Kundera studied literature and aesthetics and, like most of his generation, was caught up in the great postwar euphoria, attracted to the possibilities held out by communism, after the blight of Nazism, of a Czech society reborn.

The Russians liberated the country in 1945 and nobody was surprised when, the following year, the Communist party won 38% of the vote and formed a coalition government. Kundera joined the party (“I too once danced in a ring. It was the spring of 1948,” he confesses in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting), and some of his poetry displays the kind of lyrical enthusiasm he would later decry.

He switched his degree to film, but in 1950 was expelled for “anti-party activities”, an incident that gave birth to The Joke. Allowed to return to his studies, he rejoined the political fold in 1956, remaining in the party for the next 14 years. His freewheeling, speculative manner as a teacher of world literature at the Prague film school from 1958 until 1969 influenced many Czech new wave directors, Miloš Forman among them.

Living in exile in Paris, Kundera revised into French all his works written in Czech, then set a novel in France, Immortality (1988). The same year, The Unbearable Lightness of Being was adapted for film, directed by Philip Kaufman and starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche, and Kundera found celebrity as an author, a status he was not entirely comfortable with. He began writing in French (despite which, he won the 2007 Czech state prize for literature). Slowness (1996), Identity (1998) and Ignorance (2000) were well-received, though none had the impact of the earlier Czech works.

In 2008, after an investigation, an accusation was made against Kundera in the Czech magazine Respekt. It was claimed that in 1950 he gave the name of Miroslav Dvoracek to the police. Dvoracek, a pilot, had escaped from Czechoslovakia but returned as a western intelligence agent; he was subsequently arrested, narrowly escaped the death penalty, and served 14 years in a labour camp.

Kundera denied that he was the informant and a group of writers including Fuentes, Márquez, Rushdie, Philip Roth, Orhan Pamuk, Nadine Gordimer and JM Coetzee came swiftly to his defence in a letter declaring him the victim of “orchestrated slander”.

Havel said he thought the way events unfolded too “stupid” for Kundera to have been involved, and that his old friend and adversary, who had scrupulously kept away from the media, rarely giving interviews, had “become entangled in a thoroughly Kunderaesque world, one that he has so masterly managed to keep at a distance from all his real life”.

The following year, Kundera published Encounter, a series of essays, some going back 20 years. In one, discussing Bohumil Hrabal, the author of Closely Observed Trains, Kundera reiterates his view of the relation of politics and art, and his belief in the pre-eminence of the novel in the struggle for human liberation: “One single book by Hrabal does more for people, for their freedom of mind, than all the rest of us with our actions, our gestures, our noisy protests!”

His final novel, The Festival of Insignificance, was published in 2015. Four years later, his Czech citizenship was finally restored.

He is survived by his wife, Vera Hrabankova.

🔔 Milan Kundera, writer, born 1 April 1929; died 11 July 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first #bookmobile of the Prague library was launched in 1939. It was visiting 14 stops on the outskirts of the city https://bit.ly/3qm4Ihm

4 notes

·

View notes