#Pleistocene Predator

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Unearthing the Past: The 44,000-Year-Old Frozen Wolf and Its Secrets

Imagine stumbling upon a creature that roamed the earth 44,000 years ago, perfectly preserved as if it had just taken a nap in the snow. That’s exactly what happened in Yakutia, eastern Russia, when residents found a remarkably intact wolf frozen in thick permafrost. This isn’t just any wolf—it’s a time capsule from the Pleistocene era, and scientists are buzzing with excitement over what they…

#Ancient Bacteria#Ancient Creatures#Ancient Discovery#Ancient DNA#Ancient History#Ancient Microbes#Ancient Mysteries#Ancient Viruses#animals#Archaeological Find#Arctic Discovery#Arctic Secrets#Frozen In Time#Frozen Wolf#Medical Breakthrough#Permafrost Find#Pleistocene Era#Pleistocene Predator#Pleistocene Wolf#Prehistoric Life#Prehistoric Predator#russia#Science Buzz#Science News#Scientific Breakthrough#Scientific Discovery#Scientific Wonder#Time Capsule#Wolf Discovery#Yakutia Find

0 notes

Text

Do you want to surprise others with the modern interior of your home?

You will definitely surprise them, because these are reconstructions of animals that disappeared tens of thousands of years ago.

Also, you will definitely surprise your colleagues in the office with one of these pictures.

This exclusive and unrepeatable painting can be purchased here:

#artworks#extinct animal illustration#ice age paleoart#paleoart#pleistocene#prehistoricfauna#amazing facts#paleontology#animal wall decor#homotherium#Sabertooth predator eats prey canvas wall art#husband gift#gifts for geeks#maximalist decor#apartment decor.#Paleoart ukrainian art prints for amazing gifts for boyfriend#wildlife#wildnuture#ecosistems#college room decor#design#iceage

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

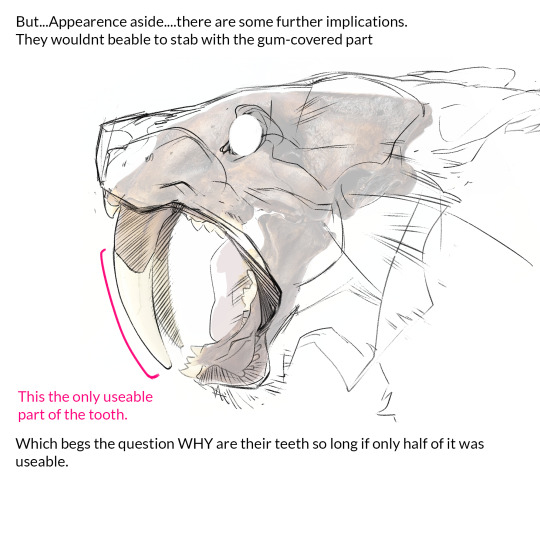

I'm hardly an expert, and have not kept up with the field, but as I understand it, the huge incisors aren't used to stab, but to slash. You pounce a baby mammoth from cover, sever an artery, bounce back into cover while the adult mammoths try to stomp you, wait for the baby to bleed out and the adult mammoths to stop mourning, then go drag the baby mammoth back to your lair to eat at leisure.

(I am thinking of scimitar cats, not smilodons; a scimitar cat lair has been excavated in Texas, at a site called the Friesenhahn Cave, that was full of baby mammoth teeth, but I don't think we have much to show what smilodons ate. But the overall anatomy is similar.)

Stabbing is not a very efficient way to kill and is dangerous to the tooth. Animals that kill by biting generally rend, or grip and shake to sever the spine, which with a sabretooth construction are great ways to break a tooth. Another big cat strategy is to clamp onto the muzzle and suffocate the prey, with is right out with probiscidians. But there's a number of places to slash a body and release a critical amount of blood in a way the prey can't do a thing about, and even if a bleeding animal escapes it leaves an easily followed trail.

You may notice that, in addition to the saber teeth, this family of "cat" has a full set of upper and lower incisors, positioned further forward than the canines. These are the gripping, ripping teeth, which can tear off bite-sized chunks of baby mammoth without endangering the big teeth too much. The tongue then conveys the meat back to the molars that chew it up small enough to go down the gullet and digest properly. Any facial reconstruction of a saber-tooth needs to take these teeth into account, as well as the attention-grabbing canines.

We are handicapped in understanding how saber-toothed predators used their teeth, as the only giant-canined species we have today (elephants and walruses) use them for sexual display and digging rather than killing, but we know it has to be an effective strategy in certain circumstances, as the adaptation has arisen more than once. A quick net search reveals a fairly recent article describing eight types, with different subtypes, which probably indicate different prey strategies.

That the most recent examples of saber-toothed predators died out with the megafauna at the end of the Pleistocene may indicate a specialization in particularly large prey such as mammoths, ground sloths, giant beavers, etc., with the canines adapted to penetrating the thick pelts and hides (and occasional bony armor) of such big herbivores; and this speculation is supported by the presence of all those juvenile mammoth teeth in Friesenhahn Cave.

My period of intensest focus on Pleistocene megafauna was 20 years ago when researching 11,000 Years Lost, so there may have been some breakthrough that I missed, and if so I hope to be enlightened.

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

The idea of Pleistocene rewilding, even though it annoys the hell out of me, is so interesting in what it implies about ecosystems.

If we accept that North America's ecosystems are "incomplete" or "impoverished" because of the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna, that implies there is a "complete" state of ecosystems. In the absolute sense, of course ecosystems don't ever have a "complete" state, but is it possible for an ecosystem to be relatively incomplete? What does that even mean?

Could an "incomplete" state of an ecosystem be recognizable without knowing what used to exist in that ecosystem, for comparison? Could a researcher tell that they were in an environment where an animal had gone extinct, without any direct evidence of that animal or knowledge of what it was? Who is to say how many taxa of a kind of creatures "should" be in the ecosystem?

Say we accept, then, that North America's ecosystems after the Pleistocene (but before European colonization, which involved intentional destruction) were "complete," in the sense that researchers couldn't detect any obvious "dysfunction," whatever that means.

But 10,000 years, compared with life's history on the earth, are nothing--- the blink of an eye. There hasn't been very much time for entirely new types of animals to evolve.

So it would imply that ecosystems have a LOT of plasticity and ability to re-arrange to absorb shock, and that animals can quickly expand their ranges and change their niches to adapt to the new state of existence.

...this, in turn, implies something strange about the introduction of new animal species to a continental mainland: that "native" and "non-native" animal species probably won't be distinguishably different in their impacts in the long term, because the ecosystem is chaotic and constantly changing to begin with.

Introducing new animals to islands is a disaster, because it's introducing an animal with a niche that didn't exist before at all, such as terrestrial predators or large herbivores. Introducing plants is a disaster in a small and unpredictable sample of cases.

But in the example of horses in North America, the impact could range from positive (horses used to be here, and their extinction "damaged the ecosystem," therefore horses being introduced "fixes" that damage) to neutral (the ecosystem adapted to not having horses very fast, therefore the ecosystem can likely adapt to having horses again very fast). Saying that horses are invasive seems to require us to believe contradictory things: that the ecosystem has changed so much since the Pleistocene that horses no longer belong, and that ecosystems can't adjust to change quickly.

Then, why indeed should we not introduce camels, or cheetahs, or lions?

Well, this is where "Pleistocene rewilding" gets on my nerves: it sees North America as fundamentally impoverished of animals, and at the same time, somehow treats different species of animal as weirdly interchangeable. We don't know if the American lion was closer to a lion or a tiger, and we don't know some important things like its hunting behavior. The "American cheetah" was not any more closely related to the African cheetah than to the cougar, and might not have been a specialized fast runner like the cheetah.

So this might apply to the horse just as well: the species of horse in Pleistocene times might have been so different from today's horse that they don't have the same role in the ecosystem. Well, is it better to be horseless or horsed?

I don't think that introduced species are inherently bad. This isn't a extreme position. Among plants, very few introduced species actually become invasive, and even some of those considered "invasive" are not actually harming the ecosystem in a way that can be demonstrated. I don't think I would recommend the introduction of a plant purposefully, though...or would I? With climate change occurring rapidly, I am in favor of moving species to areas where they can survive.

One philosophy of biodiversity is that the more biodiverse the ecosystem, the more ability the ecosystem has to absorb shock and adapt to change. Introduced species could have a range of potential to adapt different from native species, and could raise the shock absorption potential of an ecosystem. But they would also disrupt existing relationships and cause a shock to the native species that already exist.

Range expansions are an alternative to extinction for some species. We will probably HAVE to consider introducing species to new areas in the future. Well, imagine in the future we put Zebras in Arkansas, and the Zebras outcompeted the white-tailed deer in that area. Is that good or bad? Both species get to keep existing, but the deer's range is a bit smaller. Is the measure of biodiversity more important in a local area or in the world?

Makes my head hurt...

723 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smile like Smilodon, because it’s Fossil Friday! This saber-tooth cat roamed the Americas during the Pleistocene, and went extinct some 10,000 years ago. Scientists estimate that its signature teeth, which could reach lengths of 7 in (18 cm), grew at the rapid speed of .24 in (6 mm) per month—double the growth rate of an African lion’s teeth. To unsheathe these knife-like canines, Smilodon could open its jaws twice as wide as today’s big cats.

You can spot this fearsome predator in the Museum’s Hall of Primitive Mammals. We're open daily from 10 am–5:30 pm! Plan your visit.

Photo: D. Finnin / © AMNH

#science#amnh#museum#fossil#nature#animals#natural history#dinosaur#paleontology#fact of the day#mammals#cats#feline#did you know#cool animals#museum of natural history#natural history museum#big cats#smilodon#sabertooth#sabertooth cat#pleistocene#jaws#fossils#fossil friday

903 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Mummified 44,000-Year-Old Wolf Found in Siberian Permafrost

Scientists perform necropsy on an ancient wolf pulled from Russian permafrost that may still have prey in its stomach.

In a first-of-its-kind discovery, a complete mummified wolf was pulled from the permafrost in Siberia, after being locked away for more than 44,000 years. Scientists have now completed a necropsy (an animal autopsy) on the ancient predator, which was discovered by a river in the Republic of Sakha — also known as Yakutia — in 2021.

This is the first complete adult wolf dating to the late Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago) ever discovered, according to a translated statement from the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, where the necropsy was performed. The discovery, scientists say, will help us better understand life in the region during the last ice age.

Photos from the necropsy show the wolf's mummified body in exquisite detail. Animals are preserved in permafrost through a type of mummification involving cold and dry conditions. Soft tissues are dehydrated, allowing the body to be preserved in a frozen time capsule.

Researchers took samples of the wolf's internal organs and gastrointestinal tract to detect ancient viruses and microbiota, and to understand its diet when it died.

"His stomach has been preserved in an isolated form, there are no contaminants, so the task is not trivial," Albert Protopopov, head of the department for the study of mammoth fauna of the Academy of Sciences of Yakutia, said in the statement. "We hope to obtain a snapshot of the biota of the ancient Pleistocene."

He added the wolf, which tooth analysis revealed was male, would've been an "active and large predator," so they will be able to find out what it was eating, along with the diet of its victims, which "also ended up in his stomach."

Another key aspect of the necropsy is looking at the ancient viruses the wolf may have harbored. "We see that in the finds of fossil animals, living bacteria can survive for thousands of years, which are a kind of witnesses of those ancient times," Artemy Goncharov, who studies ancient viruses at the North-Western State Medical University in Russia, and is part of the team analyzing the wolf, said in the statement.

He said the research project will aid their understanding of ancient microbial communities and the role of harmful bacteria during this period. "It is possible that microorganisms will be discovered that can be used in medicine and biotechnology as promising producers of biologically active substances," he added.

The wolf necropsy is part of an ongoing project to study the wildlife that lived in the region during the Pleistocene. Other species examined include ancient hares, horses and a bear from the Holocene. The team plans to study the wolf's genome to understand how it relates to other ancient wolves from the region, and how it compares to its living relatives. The team now plans to start studying another ancient wolf discovered in the Nizhnekolymsk region of northeast Siberia in 2023.

By Hannah Osborne.

#A Mummified 44000-Year-Old Wolf Found in Siberian Permafrost#mummified wolf#Republic of Sakha#Yakutia#late pleistocene#ancient animals#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pleistocene Predators!

Arctodus - American Cheetah - Teratornis

Dire Wolf - Megalania - American Lion

Homotherium - Thylacoleo - Smilodon

Stickers || Phone Wallpapers Masterlist

#art#my art#paleoart#paleontology#science#illustration#pleistocene#ice age#smilodon#dire wolf#homotherium#arctodus#teratornis#thylacoleo#megalania#american cheetah#american lion

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 4: The Megafowl

By @thewoodparable

One of the *most* iconic dinosaurs of the Cenozoic has got to be Gastornis, often referred to as "Diatryma", the giant fowl of the Early Paleogene. This animal first appeared between 60 and 56 million years ago in Europe, and spread to Asia and North America during the earliest Eocene. In the hot temperatures of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, it even lived up in the Arctic Circle, in the Tropical Polar Forests of the period. This single genus lasted a while, living until the middle Eocene, around 45 million years ago.

Gastornis is most famous due to its size, growing as tall as 2 meters height and up to 175 kilograms in mass. This made it one of the largest birds known, with a giant head and extremely tall beak. The skull itself was very powerfully built, with the beak compressed and lacking the raptorial hook of the later appearing terror birds.

By Ashley Patch

This is important to note, because for a long time - until 2014, really - we thought Gastornis was a predator. Turns out, however, it was an herbivore, probably feeding on a generalistic diet of plants similar to other macroherbivorous dinosaurs. In fact, not only did it not have a predatory beak, but footprints that are probably from Gastornis suggest it did not have talons or raptorial feet adapted for hunting, either.

Feathers of Gastornis are not definitively known, however, a feather impression from the Green River Formation may be that of Gastornis due to its large size, and resembled feathers found on flighted birds, rather than the shaggy feathers of ratites. This is notable, as it seems that Gastornis was closely related to the "Fowl", aka Galloanserae, rather than the modern flightless ratites of today. Whether it's closer to ducks or to chickens is a question, hence the generic moniker of "Megafowl".

By @quetzalpali-art

Why did Gastornis go extinct? The answer is unclear. It seemed to have disappeared from North America and Asia at the end of the early Eocene, possibly due to the dropping temperatures. It persisted in Europe for longer, which was isolated at the time and may have thus been more habitable for Gastornis. That said, there is some evidence that the Mihirungs of Australia - who we'll get to know later - are related to Gastornis, and they are found in the Oligocene to Pleistocene of Australia - so maybe Gastornis didn't go away quite as soon as we thought!

Unfortunately, the behavior of this dinosaur is not particularly well known - it's uncertain if it lived in groups, how it nested, or what its foraging method would have been, as there are no living animals similar to it. Hopefully, more fossils of Gastornis will paint a clearer picture of the Megafowl of the Paleogene.

Sources:

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paleovember 2023, Megalania!

Once again we dip back into Australia in the Pleistocene, a time when there were even MORE wild and dangerous animals than exist today. Last year we highlighted the marsupial lion, and while it had deadly killing tools, it was far from the biggest, or the only major predator in Prehistoric Australia; just one of them was Megalania. Scientifically known as Varanus priscus, is estimated to measure over 20 feet long, making it the largest lizard to ever exist, larger than it's modern surviving relative, the Komodo dragon, which also evolved in Australia before being limited to islands in Indonesia.

#megalania#komodo dragon#monitor lizard#lizard#reptile#pleistocene#ice age#australia#illustration#art#artwork#paleoart#paleontology#procreate#drawing#digitalart#artist on tumblr#prehistoric

126 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ice Age 1, 2, 3, as I don't care or interest with other rest

Answering for all 5 baby whether you like it or not

Ice Age 1: Extremely nostalgic, so I'm very biased towards it. I know its not really anything special but i still am very fond of it. I remember getting as little embarrassed watching it when i was little cause the ending made me so emotional and i didnt want to cry. When i got older it became a long car ride classic for a few years

The movie looks rough now, but choosing to make your main cast of characters a bunch of fuzzy hairy mammals in 2002 when rendering hair was hard as hell really set Blue Sky on their path to being phenominally good at fur and feathers in their later movies.

Fucked up they never brought the baby back in the sequels but maybe it was for the better…

Ice Age 2: Manny gets a wife

As soon as the first movie ended this series basically became a sitcom about three bachelors slowly getting married off. I hold some fondness for this one since I did watch it as a kid, but even then I felt it wasn’t as good as the first one.

I remember kid being bothered by the uh…vague Mesozoic critters frozen in ice being the main antagonist in the end. It made me think of all the Land before Time sequels where they would just throw in a random prehistoric predator each movie that doesn’t talk and was just there to be a scary thing in the end that gets pushed down a cliff.

I like how they added Crash and Eddie the opossums to the gang as hip new characters but you can tell the writers didn’t care about them at all as the movies went on.

Ice Age 3: Scrat gets a babe. Also dinosaurs

Better than the second one? The plots with the main characters was boring, fortunately the little weasel guy completely stole the show and made the movie pretty fun even as someone with no attachment to it. Manny’s baby daughter is named Peaches which is admittedly a really cute name for a baby mammoth.

Tween me had a vandetta against this movie cause it bothered me SO much that the movie series giving Pleistocene critters some love resorted to using dinosaurs by the third movie. Tsk tsk

Ice Age 4: Diego gets a wife. Also pirate

Feels like the writers had no idea what to do with Peaches as a child so we get a time skip and cut to her as a teenager with a boyfriend Manny doesn’t like. Meh

Ice Age 5: Sid gets a wife. Also space ship

You can really tell they were really running out of steam at this point. I like that they didn’t know what to do with Peaches now that Manny accepts her boyfriend so they uh…gave her a different boyfriend/mammoth finance Manny needs to get along with. I remember this one the least despite having watched it the most recently besides the first one.

The output of Blue Sky somewhat reminds me of Illumination, where they have one main hit series they milked to death who’s most iconic character(s) are little unintelligible creatures who barely have anything to do with the actual movie plots.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

April Fools 2023: How Titanis Lost The Right To Bear Arms

Huge, flightless, and carnivorous, the phorusrhacids (or terror birds) were some of the largest apex predators in South America during its Cenozoic "splendid isolation" as an island continent – and they were possibly the closest that birds ever came to reclaiming the ecological roles of their extinct non-avian theropod dinosaur relatives.

And for a while in the late 1990s and early 2000s there was a hypothesis that they'd even re-evolved clawed hands.

This idea was based on the wing bones of Titanis walleri, the only terror bird known to have dispersed northwards during the Great American Biotic Interchange when North and South America became connected via the Isthmus of Panama.

Living during the Pliocene and Pleistocene in Florida and Texas, between about 5 and 1.8 million years ago, Titanis stood around 1.5-1.8m tall (~5-6') and was heavily built, with long strong legs and a massive hooked beak. Remains of its small wings were incomplete and fragmentary but had seemingly unusual joints, with what looked like a stiffer wrist and more flexible "fingers" than other birds, which led paleontologist Robert Chandler to propose in 1994 that this terror bird species had modified its wings into clawed grasping arms similar to those of dromaeosaurs, used to restrain prey animals while its beak tore them apart.

But the idea of a giant murder-bird with added meathook-hands only lasted about a decade. Further investigation in 2005 showed that Titanis' arms weren't that weird after all – the same sort of joints are found in terror birds' closest living relatives, the seriemas, and so Titanis really had the same sort of small vestigial wings as many other large flightless birds.

…However, there still could have been some claws on there. Many modern birds actually have one or two small claws on their hands that aren't visible under their feathers, and terror birds like Titanis having something like that going on is completely plausible – they just wouldn't have been using them for any sort of specalized predatory function.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#april fools#titanis claw hand hook bird claw#inaccurate paleoart#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#retrosaurs#titanis#phorusrhacid#terror bird#cariamiformes#bird#dinosaur#art

386 notes

·

View notes

Note

hallo!!! what are your favourite species of dinosaurs and generally species of prehistoric (however you define them as such) animals? any pterosaur/croc species?

waaah that's such a hard question but I love p much any of the feathery raptors, tho I sometimes sag bambiraptor bc that one especially is good pet size and has a cute name

also love a lot of the pleistocene guys bc I find the like it fascinating how kinda like.. recent but also distant they are? Was also the era of lots of cool large predators in europe, love to get starry eyed over thinking of european lions and hyenas

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlantis Phase III is here. Over the next few weekends we will put together the ecosystems of this island during the late Pleistocene, based on community submissions.

The forests of Atlantis harbor some fantastic fauna and a lot of yet to be studied flora. In the open plains large mustelids are the apex predators, here this role is filled by terrestrial crocodilians.

#paleoart#atlantisbestiary3#atlantis#specevo#speculative evolution#sciart#swamps#crocodile#pantodont#paleostream#forest

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patreon request for @/brittoniawhite (Instagram handle) - Thylacinus cynocephalus. I’ve drawn this guy already, but here’s a new pose AND a size chart, which the previous post didn’t have.

Known by several common names: the Tasmanian Tiger, Tasmanian Wolf, or simply the Thylacine, Thylacinus cynocephalus was neither canine nor feline, but instead a large carnivorous marsupial.

Being a marsupial, it had a pouch. Though it was unique in that both females and males had pouches: the males’ were used to protect their reproductive organs. Thylacine life expectancy was estimated to be between 5 and 7 years, though some captive specimens lived to 9 years. They were shy and nocturnal carnivores, likely eating other marsupials such as kangaroos, wallabies, wombats, and possums, as well as other small animals and birds, such as the similarly extinct Tasmanian Emu. However, it is a matter of dispute whether the thylacine would have been able to take on prey items as large or larger than itself. It is unknown whether they hunted alone or in small family groups, though captive thylacines did get along with each other.

Thylacinus cynocephalus was the last of the Thylacinids, a family of Dasyuromorph marsupials. It lived from the Pleistocene to the Holocene in Australia and New Guinea, driven to extinction in the 1930s by hunting, human encroachment, disease, and feral dogs. The thylacine was already extinct on the Australian mainland and New Guinea by the time British settlers arrived, with the island of Tasmania being its last stronghold. Settlers feared the marsupial would attack them and their livestock, demonizing it as a “blood drinker”, and bounties were put in place that drove the thylacine to be overhunted. As they became rarer, there was a push to capture thylacines and keep them alive in captivity, but unfortunately it was too little, too late. Conservation and animal welfare was not at the level it is today, not much was known about their behavior in the wild, and there was only one successful birth in captivity. Studies show that with continued successful breeding, a campaign to change public perception, and protections put into place much earlier, the thylacine could have been saved. But the last captive thylacine died in 1936, and official protection was not put in place until that year, 59 days before his death. Sightings continued into the 1980s, and even today some claim to see them, but all of these sightings are unconfirmed and unlikely. As are all the other animals on this account, the thylacine is definitively extinct.

Today, carnivores such as wolves and coyotes are demonized in the same way the thylacine was, and there are some who wish to also wipe them out entirely, even having succeeded in many places. While some of the thylacine’s closest relatives, like the Numbat and Tasmanian Devil, survived the European persecution which killed off the thylacines, they are still endangered today due to introduced predators and disease. Instead of continuing to search for, or trying to resurrect the lost thylacine, perhaps it is best we channel that attention, love, and regret on the species we still have. Extinction is forever, and it is easier to save those who are still alive.

This art may be used for educational purposes, with credit, but please contact me first for permission before using my art. I would like to know where and how it is being used. If you don’t have something to add that was not already addressed in this caption, please do not repost this art. Thank you!

#Thylacinus cynocephalus#thylacinus#thylacine#tasmanian tiger#tasmanian wolf#marsupials#mammals#synapsids#Australia#Tasmania#Pleistocene#Holocene

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

i'd love to hear you talk about terror birds, i don't think i've heard of them. - gutz

love you for this gutz oh my god

i love paleontology so much i wish i took it instead of business god kill me

please dont mind the silly nature about this post because this is one of my only interests and i never get to gush about them ever i cry at night wishing i owned one of their skulls or some of their fossils in general

TERROR BIRDS!! (phorusrhacids)

phorusrhacids lived from the middle paleocene epoch to early pleistocene epoch (during paleogene, neogene and quaternary periods, 62–2 million years ago). (which means our ancestors dealt with them.) (we were hunted by birds in the past.)

they were carnivorous and they were huge. it's like if ostriches went sicko mode and started eating every breathing thing in its environment. but they arent related to ostriches. sadly. these giant fucks to nature are direct ancestors to falcons, instead.

one of the largest specimens we have to current date, from the early pleistocene of uruguay, possibly belonging to devincenzia, would have weighed up to 350 kilograms (770 lb in freedom units) and actually is speculated to have gotten to around 3-4m tall (9-12ft in freedom units)

the closest living connection to them that we know of is actually not even falcons, is seriemas!! (look at those beautiful shits.)

when it comes to wingspan, one of the terror birds absolutely PEAKED OUT; the argentavis. just,,, JUST LOOK AT IT??

I LOVE YOU ARGENTAVIS. (not THE biggest wingspan of dead birds, that belongs to the pelagornis, BUT STILL. FUCKING. HUGE.)

again, circling back to the diet part here quickly before i talk too much, these guys were monsters. their beaks, as you have probably noticed in the photos ive added to this post, are pointed and curved for easier attack and gutting of their prey. their claws were also thick and sharp, similar to, you guessed it, falcons.

"oH, bUt PuDdLeS, aReNt ThEy SlOw?? CaUsE tHeY'rE sO bIg!!!1!" NO. THEY WERE FAST AS SHIT. FASTER THAN FUCKING HORSES.

LIKE RACE HORSES AT MAX SPEED TYPE HORSES. THESE GUYS WERE DEMONS.

these birds were so fucking metal that they even drove the remaining mammalian predators to hunt and live in forested areas instead of the plains that they thrived in. the birds fucking RULED the place.

their only competitors/natural predators were fucking SABERTOOTH TIGERS.

let me reiterate that,

ONLY SABERTOOTH TIGERS ATE THESE BIRDS.

im gonna cut myself off here because it's late as shit, im hearing fucking static again, and i have classes tomorrow at seven in the fucking morning

(fuck them for that, honestly. i have enough shit to deal with already and they keep me in the building for seven hours straight when we dont even have lectures anymore and we are more than able to do this shit at home, gas is SO expensive now.)

but oh my god if this interests you PLEASE go look more into them, or the very least, listen about them from lindsay nikole (the queen of this field of study) they show up in the neogene period video like really early in.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smile like Smilodon, because it’s Fossil Friday! This saber-tooth cat roamed the Americas during the Pleistocene, and went extinct some 10,000 years ago. Scientists estimate that its signature teeth, which could reach lengths of 7 in (18 cm), grew at the rapid speed of .24 in (6 mm) per month—double the growth rate of an African lion’s teeth. To unsheath these knife-like canines, Smilodon could open its jaws twice as wide as today’s big cats. You can spot this fearsome predator in the Museum’s Hall of Primitive Mammals.

To see Smilodon and more, plan your visit.

684 notes

·

View notes