#Phylogeny

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

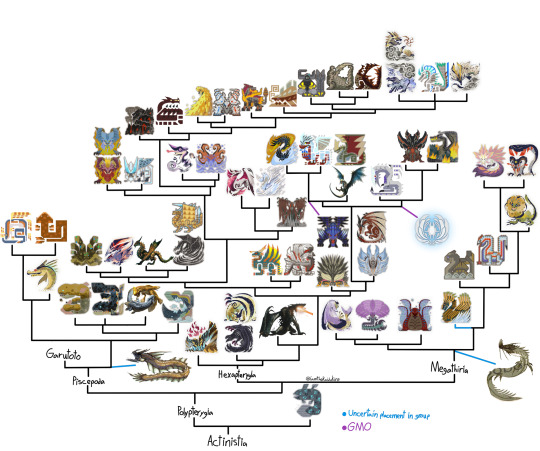

Here's a big project I've been working on for a few weeks: a phylogenetic tree of everything in Minecraft! It would take ages to explain everything here, so if you want an explaination of any inclusions, exclusions, categorisations or Latin names PLEASE PLEASE PUHLEASE ask me I would love to answer any questions :3

Here's the slides I used to make it since i'm aware the text on the image there is pretty much unreadable.

Reblogs appreciated!

Edit: there are some problems with the image on here aside from the quality, so please check the slides for a slightly more accurate version! Also, if you have a question check the notes first! Odds are someone else has asked already.

Edit 2: PLEASE check the reblogs before you ask a question, most of the questions I'm getting now are ones that have already been answered. But I of course really appreciate how much people care :3

Full image description:

At the bottom is the Origin of Life, which branches out into five kingdoms - amoebozoa, animalia, fungi, algae and plantae.

Amoebozoa is in pink. It branches into Sculk (latin name sculk sculk) and then into slimes (scindo uliginosus) and magma cubes (scindo igneum)

Animalia starts off in orange. It branches off into the five types of coral (Fire - millepora, horn - rugosa, tube - tubipora musica, bubble - Plerogyra sinuosa, brain - diploria). The second branch of animalia branches off to the sponge (in the phylum demospongiae) and then to molluscs and arthropods.

Moluscs first branches off to the shulker (duopartes purpur) then to the nautilus (latin name nautilus), the ghast (Exspiravita inferno) the heart of the sea (unknown latin name), the squid (Immiforma caeruleum) and the glow squid (Immiforma crepuscula). The heart of the sea and nautilus are both marked with a dagger symbol, indicating they are extinct.

Arthropods branches off to the enderman (gracillis sapiens) and the ender dragon (draconiforma finis). It also branches off into insects, featuring bees (bombus enormus) and silverfish (Lepisma saccharinum), as well as to arachnids, featuring the endermite (terminus limina), the spider (rufoculos nocturnis) and the cave spider (rufoculos caverna).

Carrying on from the branch of animalia is the sea pickle (Pyrosoma) and then the vertebrates, which are coloured in reddish orange. The first branch contains the Queen angelfish (Holacanthus ciliaris), the emperor red snapper (Lutjanus sebae) and the moorish idol (Zanclus cornutus). the second branch contains salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). The third branch contains the yellowtail parrotfish (Sparisoma rubripinne), the clownfish (Amphiprion percula) and the dottyback (Diadem pseudochromis). The next branch contains cod (Gadus). the final fish branch contains the triggerfish (Abalistes stellatus), the pufferfish (Arothron meleagris) and the yellow tang (Zebrasoma flavescens).

Next the branch transitions into tetrapods. coming off this are amphibians, which includes the frog (Lithobates thermochroma) and the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum)

image desc currently unfinished, would appreciate help

11K notes

·

View notes

Note

are ammonites a sort of missing link between gastropods and cephalopods? since they're basically squids with snail shells? or are cephalopods just really derived gastropods?

no, ammonites were regular degular cephalopods as much as a squid or an octopus is today, they weren't a missing link of anything.

and cephalopods aren't gastropods, but both cephalopods and gastropods are mollusks! they love on opposite sides of their family tree:

mollusks are one of the very oldest and most diverse classes of animal life on earth, so it's not too surprising that they invented some bizarre standout characters in that timeframe! the very first cephalopods roughly 500 million years ago were basically a weird ball of snot with a shell that was jussssst starting to figure out this whole arms and eyes thing:

<src: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plectronoceras_cambria.jpg#/media/File:Plectronoceras_cambria.jpg>

(WIZARD HAT)

over the next 500 million years, different branches of the cephalopod would eliminate (octopus) internalize (squid, cuttlefish) or embiggen the external shell (ammonites, nautiluses) as suited their specific needs.

and they're only going to get weirder from here

720 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the one hand, it's true that the way Dungeons & Dragons defines terms like "sorcerer" and "warlock" and "wizard" is really only relevant to Dungeons & Dragons and its associated media – indeed, how these terms are used isn't even consistent between editions of D&D! – and trying to apply them in other contexts is rarely productive.

On the other hand, it's not true that these sorts of fine-grained taxonomies of types of magic are strictly a D&D-ism and never occur elsewhere. That folks make this argument is typically a symptom of being unfamiliar with Dungeons & Dragons' source material. D&D's main inspirations are American literary sword and sorcery fantasy spanning roughly the 1930s through the early 1980s, and fine-grained taxonomies of magic users absolutely do appear in these sources; they just aren't anything like as consistent as the folks who try to cram everything into the sorcerer/warlock/wizard model would prefer.

For example, in Lyndon Hardy's "Five Magics" series, the five types of magical practitioners are:

Alchemists: Drawing forth the hidden virtues of common materials to craft magic potions; limited by the fact that the outcomes of their formulas are partially random.

Magicians: Crafting enchanted items through complex manufacturing procedures; limited by the fact that each step in the procedure must be performed perfectly with no margin for error.

Sorcerers: Speaking verbal formulas to basically hack other people's minds, permitting illusion-craft and mind control; limited by the fact that the exercise of their art eventually kills them.

Thaumaturges: Shaping matter by manipulating miniature models; limited by the need to draw on outside sources like fires or flywheels to make up the resulting kinetic energy deficit.

Wizards: Summoning and binding demons from other dimensions; limited by the fact that the binding ritual exposes them to mental domination by the summoned demon if their will is weak.

"Warlock", meanwhile, isn't a type of practitioner, but does appear as pejorative term for a wizard who's lost a contest of wills with one of their own summoned demons.

Conversely, Lawrence Watt-Evans' "Legends of Ethshar" series includes such types of magic-users as:

Sorcerers: Channelling power through metal talismans to produce fixed effects; in the time of the novels, talisman-craft is largely a lost art, and most sorcerers use found or inherited talismans.

Theurges: Summoning gods; the setting's gods have no interest in human worship, but are bound not to interfere in the mortal world unless summoned, and are thus amenable to cutting deals.

Warlocks: Wielding X-Men style psychokinesis by virtue of their attunement to the telepathic whispers emanating from the wreckage of a crashed alien starship. (They're the edgy ones!)

Witches: Producing improvisational effects mostly related to healing, telepathy, precognition, and minor telekinesis by drawing on their own internal energy.

Wizards: Drawing down the infinite power of Chaos and shaping it with complex rituals. Basically D&D wizards, albeit with a much greater propensity for exploding.

You'll note that both taxonomies include something called a "sorcerer", something called a "warlock", and something called a "wizard", but what those terms mean in their respective contexts agrees neither with the Dungeons & Dragons definitions, nor with each other.

(Admittedly, these examples are from the 1980s, and are thus not free of D&D's influence; I picked them because they both happened to use all three of the terms in question in ways that are at odds with how D&D uses them. You can find similar taxonomies of magic use in earlier works, but I would have had to use many more examples to offer multiple competing definitions of each of "sorcerer", "warlock" and "wizard", and this post is already long enough!)

So basically what I'm saying is giving people a hard time about using these terms "wrong" – particularly if your objection is that they're not using them in a way that's congruent with however D&D's flavour of the week uses them – makes you a dick, but simply having this sort of taxonomy has a rich history within the genre. Wizard phylogeny is a time-honoured tradition!

#gaming#tabletop roleplaying#tabletop rpgs#dungeons & dragons#d&d#worldbuilding#taxonomy#phylogeny#media#literature#history#literary history#death mention

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

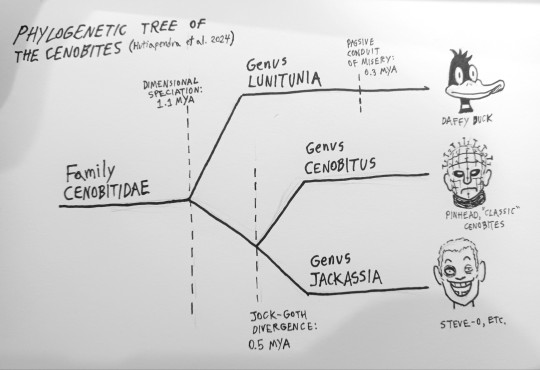

Phylogenetic tree of the Cenobites

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

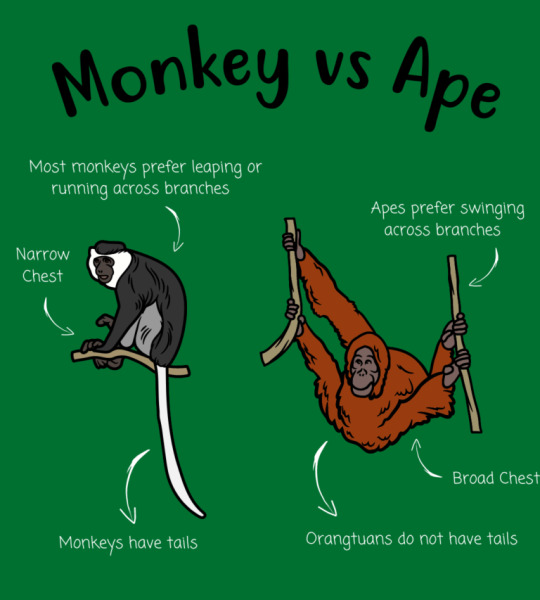

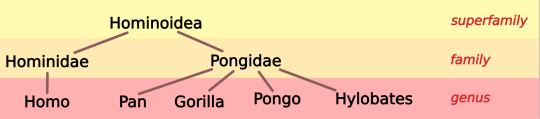

Apes are a kind of monkey, and that's ok

This is a pet peeve of mine in sci comm ESPECIALLY because many well respected scientific institutions are insistent about apes and monkeys being separate things, despite how it's been established for nearly a century that apes are just a specific kind of monkey.

Nearly every zoo I've visited that houses apes has a sign somewhere like the one below that explains the supposed distinction between the two groups, focusing on anatomy instead of phylogeny.

(Every time I see a graphic like this I age ten years) Movies even do this, especially when they want to sound credible. Take this scene from Rise of the Planet of the Apes:

This guy Franklin is presented as the authority on apes in this scene, and he treats James Franco calling a chimpanzee a monkey like it's insulting.

But when you actually look at a primate family tree, you can see that apes are on the same branch as Old World monkeys, while New World monkeys branched off much earlier.

(I'm assuming bushbabies are included as "lorises" here?)

To put it simply, that means you and I are more closely related to a baboon than a baboon is to a capuchin.

Either the definition of monkey includes apes OR we can keep using an anatomical definition and Barbary macaques get to be an ape because they're tailless.

"I've got no tails on me!"

SO

Why did all this happen? Why did we start insisting apes are monkeys, especially considering the two words were pretty much interchangeable for centuries? Well I've got one word for ya...

This the attitude that puts humans on a pedestal over other life on Earth. That there are intrinsically important features of humanity, and other living things are simply stepping stones in that direction.

At the dawn of evolutionary study, anthropocentrism was enforced by using a model called evolutionary grades. And boy howdy do I hate evolutionary grades.

Basically, a grade is a way of defining a group of animals by using anatomical "complexity". It's the idea that evolution has milestones of importance that, once reached, makes an organism into a new kind of thing. You can almost think of it like evolutionary levels. An animal "levels up" once it gains a certain trait deemed "complex".

You can probably see the issue here; that complexity is an ephemeral idea defined through subjectivity, rather than based off anything truly observable. What makes walking on 2 legs more complex than walking on four? How are tails less complex than no tails? "Complexity" in this context is unmeasurable, therefore it is unscientific. That's why evolutionary grades suck and I never want to look at one.

For primates, this meant once some of them lost their tails, grew bigger brains, and started brachiating instead of leaping, they simply "leveled up" and became apes. Despite the early recognition that apes were simply a branch of the Old World monkey family tree (1785!), the idea of grades took precedent over the phylogenetic link.

In the early years of primatology, humans were even seen as a grade "above" apes, related but separated by our upright stance and supposed far greater intelligence (this was before other apes were recognized tool users).

It wasn't until the goddamn 1970s that it was recognized all great apes should be included in the clade Hominidae alongside humanity. This was a major shift in thinking, and required not just science, but the public, to recognize just how close we are to other living species. It seems like this change has, thankfully, happened and most institutions and science respecting folks have accepted this fact. Those who don't accept it tend to have a lot more issues with science than only accepting humans as apes.

And now, we come to the current problem. Why is there a persistent idea that monkeys and apes are separate?

I want to make it clear I don't believe there was a conscious movement at play here. I think there's a lot of things going on, but there isn't some anti-monkey lobby that is hiding the truth. I think the problem is more complicated and deals with how human brains and human culture often struggle to do too many changes at once.

Now, I haven't seen any studies on this topic, so everything I say going forward is based on my own experience of how people react to learning apes (and therefore, humans) are monkeys.

First off, there is a lot of mental rearranging you have to do to accept humans as monkeys. First you, gotta accept humans as apes, then you have to stop thinking in grades and look at the family tree. Then you have to accept that apes are on the Old World monkey branch, separate from the New World monkeys.

That's a lot of steps, and I've seen science-minded zoo educators struggle with that much mental rearranging. And even while they accept this to an extent, they often find it even harder to communicate these ideas to the public.

I think this is a big reason why zoos and museums often push this idea the hardest. Convincing the public humans are apes is already a challenge, teaching them that all apes are monkeys at the same time might seem impossible.

I believe the other big reason people cling to the "apes-aren't-monkeys" idea is that it still allows for that extra bit of comforting anthropocentrism. Think of it this way; anthropocentrism puts humans on a pedestal. When you learn that humans are apes, you can either remove the pedestal and place humans with other animals, OR, you can place the apes up on the pedestal with humanity. For those that have an anthropocentric worldview, it can actually be easier to "uplift" the apes than ditch the pedestal.

Too make things worse, monkeys are such a symbol of a "primitive" animal nature that many can't accept raising them to the "level" of humanity, but removing the pedestal altogether is equally painful. So they hold tight to an outdated idea despite all the evidence. This is why there's often offense taken when an ape is called a monkey. It's tantamount to someone calling you a monkey, and that's too much of a challenge to anthropocentrism.

Personally, I think recognizing myself as a monkey is wonderful. Non-ape monkeys are as "complex" as any ape. They make tools, they have dynamic social groups, they're adapted to a wide range of environments, AND they have the best hair of all primates.

I think we should be honored to be considered one of them.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The new Polypterygia tree!

Not a whole lot changed outside of species being added. But piscine wyverns finally got a scientific name and Somnacanth has its own family of leviathans. Because this is just building off the last iteration, there is still fanon and recontextualizing and reworking many outlandish traits some of these monsters have and basically giving some of canon/what some of the hunters guild tells us the middle finger for the sake of more interesting theories.

Once again thanks to @mayfly0678 for the name “Polypterygia” and Lizardwizard for the spore theory.

And of course, here’s the almost 20,000 word google doc to go with it.

Now I have to do the same thing with bird and flying wyverns, except I have to make a document from scratch for it… ughhh

#monster hunter#speculative biology#speculative evolution#monsterhunter#monhun#monster hunter biology#elder dragon#piscine wyvern#leviathan#taxonomy#phylogeny#phylogenetics#cladistics#speculative zoology#Cladogram

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Living species listed according to how closely related they are to us

(part 1; pictures from Wikipedia, species numbers mostly from Catalogue of Life)

Genus Pan, 2 species: chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes; bonobo, Pan paniscus. Our closest relatives.

2. Genus Gorilla, 2 species: western gorilla, Gorilla gorilla; eastern gorilla, Gorilla beringei

3. Genus Pongo, 3 species: orangutans

(We've reconstructed family Hominidae, the great apes, with a total of 8 species.)

4. Hylobatidae, 20 species: gibbons and siamangs

(We've reconstructed superfamily Hominoidea, apes, with 28 species total. We obviously share with them a great deal of physical similarities, including a lack of tail, a chest wider than it's deep, highly mobile shoulders, and very long childhood that requires extensive parental care and teaching.)

5. Cercopithecoidea, 161 species: the "Old World monkeys" of Africa and Asia, including macaques, baboons, vervets, langurs, colobuses, and proboscis monkeys

(We've reconstructed clade Catarrhina, which among other things all share 32 teeth in the same pattern, nostrils opening downward, and never having a prehensile tail, unlike...)

6. Platyrrhini, 182 species: the "New World monkeys" of South America, including spider and howler monkeys, marmosets, capuchins and squirrel monkeys

(We've reconstructed Anthropoidea, which share flat fingernails, a fused upper lip -- :) instead of :3 -- and a single-chamber uterus undergoing a menstrual cycle)

7. Tarsiiformes, 14 species: tarsiers

8. Strepsirrhini, 143 species: "prosimians", including lemurs, indris, bushbabies, lorises, and the ayé-ayé

(We've reconstructed order Primates, with about 500 species, which among other things share an omnivorous diet, a relatively large brain, fully prehensile hands, and bony eye orbits.)

9a. Scandentia, 23 species: tree shrews 9b. Dermoptera, 2 species: flying lemurs

Unclear which of these two groups is closest to Primates, or whether they form a clade of their own (Sundatheria). This and the next few links are based mainly on molecular evidence.

10. Glires, ca. 2500 species: Rodentia (including mice, rats, squirrels, marmots, beavers, porcupines, guinea pigs, and capybaras) + Lagomorpha (rabbits, hares, and pikas)

11. Laurasiatheria, ca. 2700 species: a very large and diverse group of mammals, including Carnivora (cats, dogs, hyenas, bears, weasels, seals and sea lions), Cetartiodactyla (ruminants, pigs, camels, hippopotami, whales, and dolphins), Perissodactyla (horses, tapirs, and rhinos), Chiroptera (bats), Pholidota (pangolins), Eulipotyphla (moles, shrews, and hedgehogs), and so on

12a. Xenarthra, 37 species: sloths, anteaters, and armadillos 12b. Afrotheria, 88 species: elephants, manatees, ardvaarks, hyraxes, tenrecs and golden moles

Again, these two may branch off in any order from our line.

(We've reconstructed Placentalia, the placentate mammals, with about 5900 species total.)

13. Marsupialia, 335 species: possums and opossums, kangaroos, wallabies, koalas, wombats, bandicoots, Tasmanian devils, and so on

(We've reconstructed Theria, a clade of mammals distinguished by having mammaries with nipples and XY sex chromosomes.)

14. Monotremata, 5 species: the platypus and echidnas

(We've reconstructed Mammalia, mammals, with about 6200 species total. Many distinguishing features, including milk glands, middle ear bones, isolating fur with various skin glands, and warm-bloodedness, a four-chambered heart, and differentiated teeth.)

(to be continued)

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

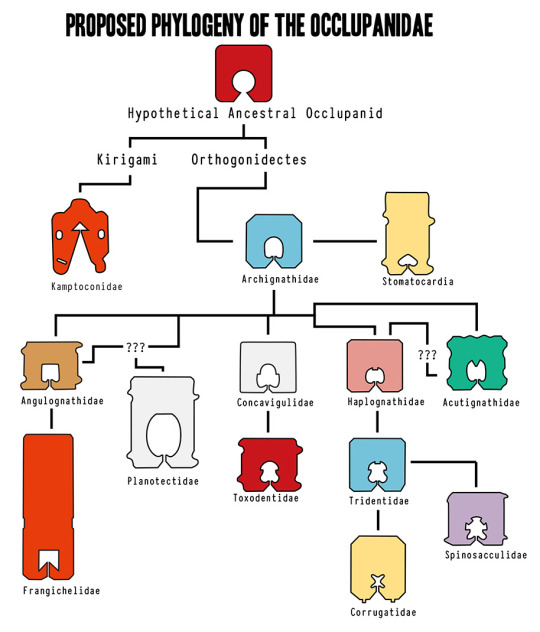

the phylogeny of bread clips

654 notes

·

View notes

Text

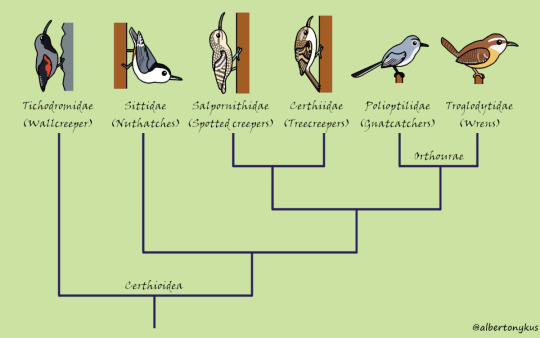

Wrens, nuthatches, and treecreepers are members of Certhioidea, a group of generally small but highly charismatic birds. One of my favorite songbird clades.

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biology is so crazy

Like what do you mean this fucken thing is more closely related to humans than to other goopy looking things like jellyfish?

Like cmon

Insane

#salps are such cool little goobers#shoutout to their larval notochord#and how falcons are closer to parrots than other birds of prey like hawks#I love phylogeny and evolution#funny#meme#funny meme#biology#zoology#tunicates#evolution#phylogeny#animals#marine biology

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

are there any centipedes with long legs like house centipedes but also long body like other centipedes?

i've been falling down the centipede love pit. theyre so beautiful and sweet😩 and the way they move is so joyous. planning on a centipede tattoo when i have the money for it <3

unrelated but thank you for all the detailed bug photos, fantastic for art reference.

short answer: no

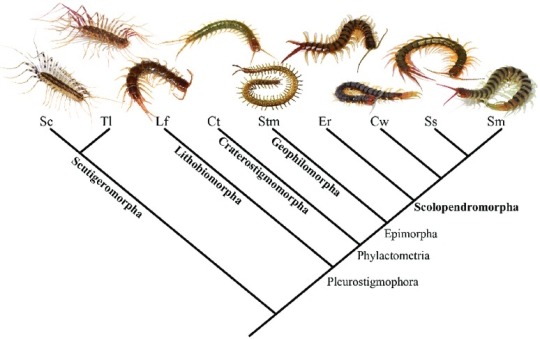

long answer w/ centipede phylogeny: below

there are 5 orders in the class Chilopoda: Scutigeromorpha, Lithobiomorpha, Craterostigmomorpha, Scolopendromorpha, and Geophilomorpha.

tree:

scutigeromorphs are the basalmost centipedes, but have a number of traits that clearly weren’t present in the common ancestor of all centipedes, including the hypersegmented legs and unpaired dorsal spiracles. 15 pairs of legs, anamorphic growth, no maternal care

lithobiomorphs are the next to split off. 15 pairs of legs, anamorphic growth, no maternal care

craterostigmomorphs are fairly similar to look at but the two living species form their own order, which is restricted to Tasmania and NZ and therefore I have no photos of my own to show you! they also have 15 pairs of legs & are anamorphic but start with 12 so only grow more legs in a single molt, maternal care

scolopendromorphs are the big, flashy centipedes of the tropics but also contain some smaller temperate species as well. 21-23 leg pairs depending on species (a few oddballs with duplications), epimorphic growth, maternal care

geophilomorpha are the most speciose centipede group, and are typically very long and thin. leg count varies between species and usually sexes (total range from 27 to 191 pairs), epimorphic growth, maternal care

the closest any epimorphic centipede gets to the hypersegmented condition in scutigeromorphs is Newportia, a genus of scolopocryptopid scolopendromorphs whose terminal legs are highly segmented, probably serving a sensory function but without the prehensile grip of scutigeromorphs.

Cermatobius lithombiomorphs do get very leggy but given that they still have 15 leg pairs they just sort of look like flat scutigeromorphs to me

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

at first i asked myself why i spent my time making the autism creature into a pakicetus. but then i realized that i was only doing what is good and right

#looking at it brings me peace#art#artwork#digital art#cute art#drawing#digital artwork#illustration#my art#pakicetus#tbh#autism creature#phylogeny#taxonomy#animal posting#biology#animals#prehistoric

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

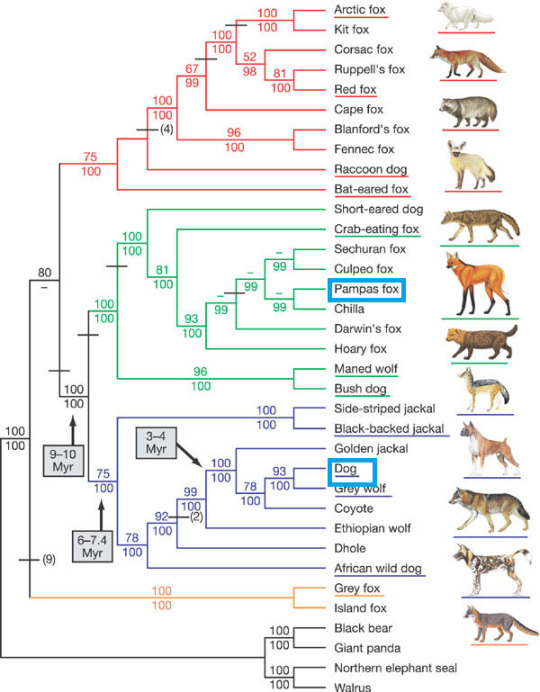

Have you heard about the Dog x Fox hybrid they found in Brazil?

it's actually a really interesting case of hybridization!

the animal in question has been genetically tested and confirmed to be a hybrid between a dog and a pampas fox, but the caveat there is that pampas foxes are actually in a new-world genus called Lycalopex, sometimes known as the False Foxes!

these animals are actually quite a bit closer to dogs than true foxes (everything in the genus Vulpes) are, genetically speaking, so it's not too hard to imagine that it COULD happen, but it's still pretty bonkers that it did!

here's the miscreant in question.

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

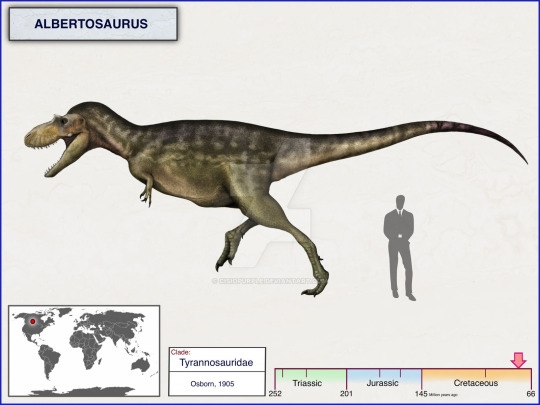

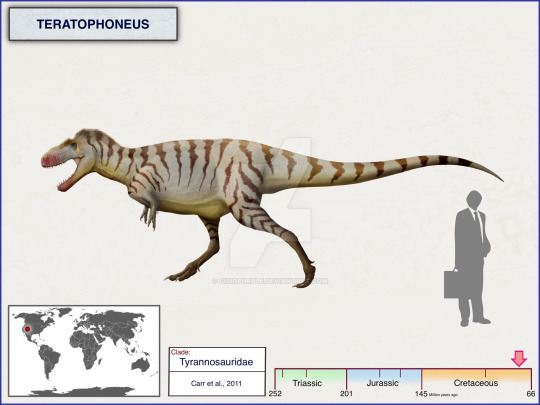

Monday Musings: The Tyrannosaur Family Tree

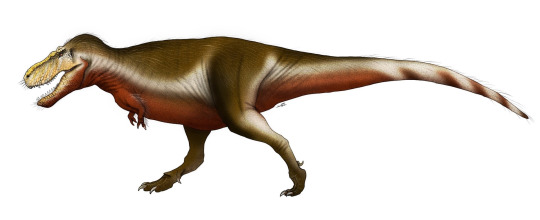

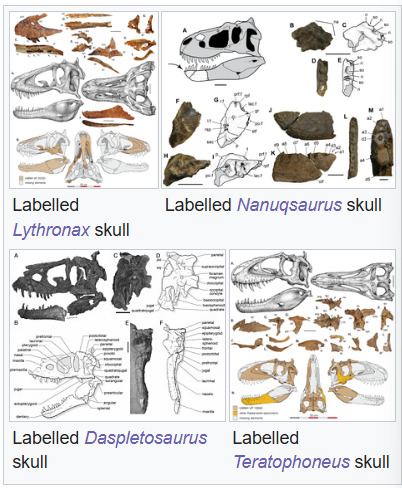

Tyrannosauridae is a family of coelurosaurian theropods from the Late Cretaceous Period. It is broken up into two subfamilies, Albertosaurinae and Tyrannosaurinae. Albertosaurinae consists of two genera: Albertosaurus sarcophagus

and Gorgosaurus liberatus.

Tyrannosaurinae consists of Qianzhousaurus sinensis,

two species of Alioramus,

Nanuqsaurus hoglundi,

Teratophoneus curriei,

Lythronax argestes,

three species of Daspletosaurus,

Zhuchengtyrannus magnus,

Tarbosaurus (or Tyrannosaurus) bataar,

and at least two Tyrannosaurus species.

Notice a lot of similarities? Good, you should. Families should look similar. All tyrannosaurids were large-bodied animals capable of weighing a least 1 metric ton (2200 lbs). That's as much as a very large bull American Bison. Tyrannosaurid skulls are incredibly well known. Alioramus is the only one without a complete skull to study right now.

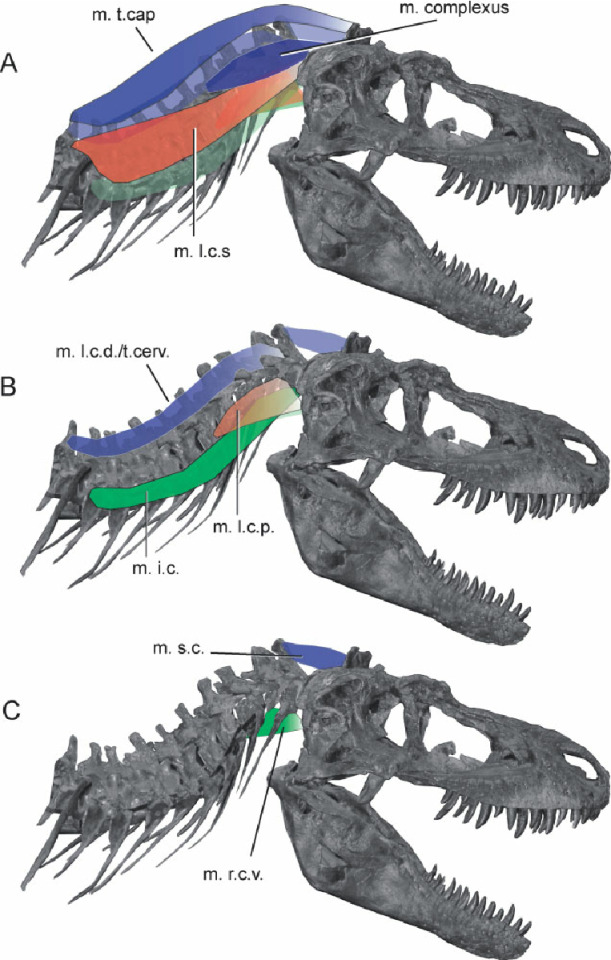

Adult tyrannosaurids had tall, massive skulls that were reinforced by fused pieces. They also had large fenestrae and hollow spaces to reduce the weight of such large skulls. They have many unique characteristics including fused parietal bones with a prominent sagittal crest and a tall nuchal crest (muscle attachments at the back of the head).

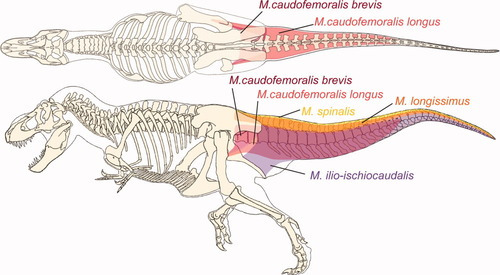

Tyrannosaurids had thick, s-curved necks to hold up their large heads as well as long, thick tails to act as a counterweight.

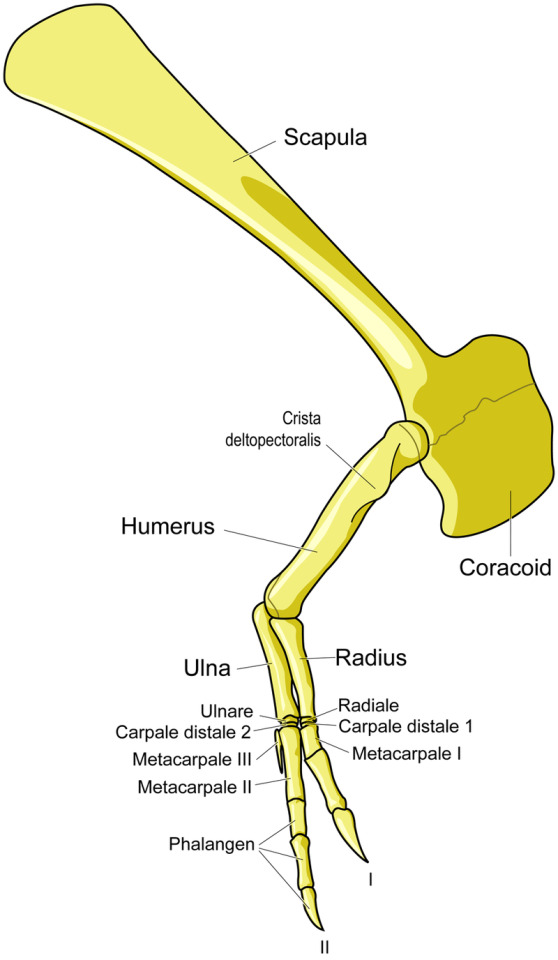

They also have proportionately small arms with two fingers.

Soft tissue studies from the last few years also suggest that tyrannosaurids had lips to protect teeth from external damage.

Tyrannosauridae is a family within the superfamily Tyrannosauroidea. This superfamily includes Coeluridae, dinosaurus like Compsognathus longipes,

Proceratosauridae with dinosaurs like Sinotyrannus kazuoensis,

Megaraptorans like Megaraptor namunhuaiquii,

and Eutyrannosaurs like Appalachiosaurus montogomeriensis.

Altogether, they make quite a family portrait so make sure to tune in tomorrow to see if you were paying attention to today's lesson. Fossilize you later!

#paleontology#fossils#fun facts#dinosaur#science education#science#tyrannosaurs#tyrannosaurids#phylogeny#taxonomy

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about bovid phylogeny and how this guy (four horned antelope)

is more closely related to this guy (gaur)

than he is to this guy (Damara dik-dik)

831 notes

·

View notes

Text

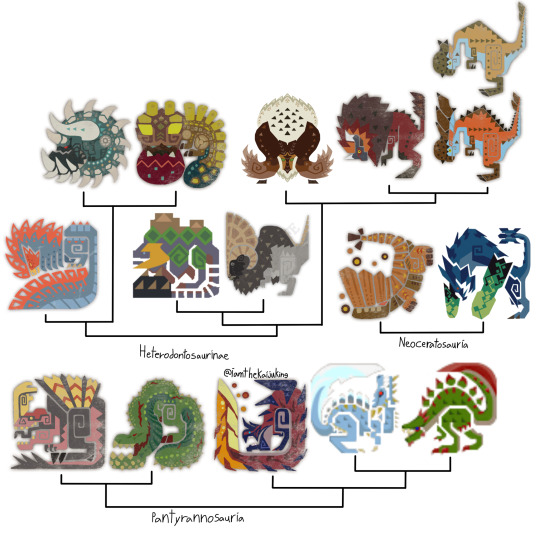

My phylogeny of brute wyverns as of the release of wilds

Pantyrannosaur brutes

Anjanath: A belligerent and snotty species of monster. Anjanath are forest creatures that navigate the rough terrain with their narrow bodies and opposable first toes.

Two subspecies exist, the Ancient Forest Anjanath and the Fulgur Anjanath. Despite being labeled a subspecies of the forest variety, Fulgurs are in fact the original species from which Ancient Forest Anjanaths descend from. While they are nomadic, Fulgurs have a preference for boreal forests, where their large size and feathers insulate themselves. They’re notable for their electrogenesis, which is produced by a subcutaneous layer of tissue between the skin and muscles. The sails serve as threat displays and aid in electrical management. Their electricity is transferred to their bite and nasal passages, electrifying their snot as they lob it at opponents.

At some point a population of Fulgur Anjanath in the hoarfrost reach found their way to the ancient forest and adapted. They gave up their extravagant silver orange and blue colors for a black and pink vulture-like color. They also switched from electrogenesis to fire breathing, and this is accomplished thanks to a bioluminescent fluid Ancient Forest Anjanaths produce in their throats. When regurgitated into the mouth, mixed with snorted up snot, exposed to the open air and charged with electricity, this fluid ignites and produces the flames the subspecies is known for. Forest Anjanaths have also repurposed their sails for thermoregulation in their hotter habitat.

The head of the Anjanath is perhaps its most striking feature. The tooth row on the bottom jaw is zigzagged with some of the teeth sitting outside of the mouth and adapted into tusks. The Anjanath’s sense of smell is among the best in the animal kingdom and nasal system is vast and accordion-like. The nasal bones are not ossified and can flip back to allow the nasal passages to extend out the skull when flushed with blood and improve its scent. They often mark territory with snot.

The cartilaginous nature of the nasal bones is interesting as these bones are usually very robust within the tyrannosaur family due to their importance in bite stress handling. This indicates that Anjanath may have a proportionally weaker bite than its kin, and it does seem to have adaptations to compensate. The mandibles, normally not fused and kept separate in most diapsids, fuse together at the front like a crocodilian or mammal and have many stress handling adaptations, meaning that when biting most of the stress is transferred to the mandibles and not the cranium. And instead of overwhelming crushing bite force the species may opt for a good grip and to thrash prey like a crocodile.

The species is normally solitary but when confronted with its own kind it has a very complex series of behaviors meant to ward off competition. Interactions usually start (and end) with the sizing up phase, where either party flairs their sails and nostrils, mouths open and roaring to appear bigger and meaner. If that doesn’t work then they begin nipping each other’s sensitive snouts. If either party fails to back down then all bets are off and a full blown fight takes place, complete with them cutting each other with their spiny tails and leg spurs.

Anjanath offer a glimpse into the evolutionary history of pantyrannosaur brutes. It seems like the group split off from other tyrannosaurs right before they lost their third fingers, but just as they were developing powerful jaws.

Deviljho: A ravenous and dangerous species of tyrannosaur known to inflict terror within the ecosystem and hearts of hunters.

Deviljho are notable for two major things. Their insatiable appetite and production of dragon element. Deviljho are never not hungry and will attempt to eat anything that moves or smells semi edible. Their powerful jaws and numerous chin teeth propelled by a massively muscled neck serve as a deadly mace that can easily kill and cripple. Hides unable to be opened by their bone crushing jaws are melted by their acidic saliva. Deviljho are not opposed to eating rotting carcasses either, which their powerful immune system can deal with thanks to dragon element (dragon element is likely something produced by the immune system of monsters often in contact with things such as rotting flesh). The presence of a single Deviljho creates a massive landscape of fear and many species will flee their habitats just to get away from the cetacean sized tyrannosaur. One case of a Deviljho that was stranded on an island ended in the elimination of all other megafauna. The species is nomadic, and can walk for days on end thanks to hypertrophied caudofemoralis muscles that give their tails such a thick shape.

Most fascinating however, are the numerous indications that Deviljho as a species is not doing very well and either suffered a horrible population bottleneck in the past or may very well be on its last legs.

Deviljho do not live very long, which is the opposite of what’s expected from such a large animal. Numerous cranial adaptations also seem to indicate inbreeding. Deviljho have poor hearing, vision, and smell which is the opposite of what it should be for a tyrannosaur. The teeth grow at a near cancerous rate, especially on the mandibles, and this causes much pain and discomfort. In old world populations teeth grow out of where their lip muscles would attach to the cranium and their liplessness might indicate that their lips were ripped off their face by their own teeth. New world Deviljho are doing even worse. Nearly 50% of their cranium is the maxilla bones, which their teeth look like they’re exploding out of and give them a lobed look. The maxilla are so hypertrophied that they’re enveloping the premaxilla and pushing back the nasals and jugal bones, scrunching up the nose like a brachycephalic dog.

Generally if an inbred animal looks bad on the outside, it’s doing even worse on the inside. Their horrible digestive efficiency is likely a result of inbreeding, and many Deviljho are noted to be sterile. Their dragon production can even become dangerous, with the deleterious mutation resulting in the terminal Savage variant being common.

Why might such a powerful species of animal be doing so poorly in the world? Well, it could be that this just isn’t Deviljho’s world anymore. One hypothesis by UHC suggests that in the last ice age Jhos were predators of large proboscideans and sauropods like Gammoth and Larinoth. Deviljho are nomadic simply because they followed their food for days via their caudofemoralis muscles and used their face (which likely had less teeth and might resembled something like a robust Anjanath) to inflict crippling wounds on prey which they would eat for days on end. But now large elephants and sauropods are a rarity and with its main food source gone, the once mighty Deviljho is not far behind…

Glavenus: Striking and flamboyant carnivores who’re best known for their heavily biomineralized sword tails. Their placement in this group is controversial, but it seems they are the closest living relatives to the Rugu family, which are themselves related to Deviljho and Anjanath.

Much of what we know of the species actually comes from males, as those are the only individuals ever hunted. Glavenus are much like peacocks in that they invest heavily in their appearance, with large horns, back plates, and their iconic tails (it’s presumed that these features are less prominent on females). The tail sword is formed by metal that is secreted into the skin, and this ore is ingested by the Glavenus. Males are very choosy over the metals they eat for their swords and fiercely guard their favorite ore spots. In the months leading up to mating season they even migrate to volcanic environments for the high quality metals found within.

So precisely maintained are their swords that they even have anti rust and sharpening adaptations. The armored face of a Glavenus is an adaptation for tail maintenance, complete with ridges to prevent sparks from getting in the eyes and clamp like structures on their armor. When their sword gets dull or rusty they bring their tail to their mouth, and these clamps both scrape away rust and sharpen the blade. The waste is then collected within their mouth and stored in a special gizzard called the Bursa.

While the sword tail is mostly for show, Glavenus are not afraid to use it for defense. Swinging it around with remarkable dexterity and even jumping to slam it down, and they have wide feet and ankle spurs to help stick their landings and to allow the footwork necessary for their twirling. If push comes to shove they can even drive up their metabolism and heat up their tails (which they also heat with friction) and the contents of their bursa, making the former hot enough to glow and making the latter hot enough to take a liquid form that can be regurgitated at threats. They have special heat resistant tissues in these areas to combat the burning temperatures, and their back plates flush with blood to help thermoregulate.

A subspecies is known to be native to the rotten vale of the new world, known as Acidic Glavenus. While still fussy about the ores on their sword tails, they also secrete crystal sulfur onto their tails filtered from the effluvium they breathe in. This crystal sulfur acts as a protective sheath and further indicator of fitness, as a male with a powerful immune system can better filter effluvium and thus extract more sulfur.

This sulfur has defensive properties as well. The rotten vale is a wet environment, and as an Acidic Glavenus rubs and swings its tail around the acid crystals come in contact with water and oxygen, forming sulfuric acid. If sufficiently pressed, an Acidic Glavenus will shed the sulfur and engage property with its sword, and their attacks feature more jabs and half swings than their cousins due to the cramped environment of the vale.

Glavenus do not hunt with their tails and instead kill with their bone crushing jaws.

Giaorugu: A poorly studied arctic species. Giaorugu take whatever they can in their harsh habitat, killing with their large tusks and making short work of kills with their acidic saliva. They defend themselves from larger predators with their sword tail and water they store in a gizzard that freezes in the open air due to the extreme temperatures of their surroundings.

Males have a larger frill and back plates.

Abiorugu: A species descended from Giaorugu populations around the new world and have been encroaching eastward. They have repurposed their gizzard into a flame sack. The frill present in Giaorugu does not fully come together in Abiorugu, instead forming brow crests. Mated pairs stick together.

Neoceratosaur brutes

Barroth: Theropods that live in arid regions and are known for their distinct heads and diet of bugs.

Barroth are found in deserts and not far from water. They live in ponds and watering holes which they diligently maintain and transform with their crowns and broad hands into muddy homes where they spend most of their time. Fitting for something that spends a lot of time submerged, the species has semiaquatic adaptations. Their feet are flat, broad, and each have two fleshy lobes to increase their surface area. This helps Barroth both swim and not sink into mud they’re standing on. Their nostrils are also situated at the top of their crown, and when submerged the tip is all that’s visible.

These mud holes are primarily for protection against aggressors such as members of the parave blos genus and against the heat of the sun, and Barroth are violently protective of their mud holes.

Despite spending most of their time in mud, they do not eat anything in it. Barroth are in fact myrmecophages, and they must leave the safety of their beloved mud holes to search for food. Before leaving their homes, they roll around in mud to affix large clumps of it to their thick carapace. This mud armor serves many purposes. It acts as a shield against the hot sun, protection against parasites, and even hides their scent. Bits may occasionally fall off and these provide important sources of minerals and water for any flora growing along the path a Barroth might take.

Upon finding an anthill they smash it with their crown and eat any ants coming out at their leisure. Unlike many other myrmecophages, Barroth lack a long flexible tongue, and this is because in the old world where they evolved they primarily target Altaroth which are large enough to negate this issue. New world Barroths get around this not because their prey is large enough to not warrant a tongue, but because Carrier Ants are so numerous and omnipresent it’s not an issue. Like many myrmecophages, Barroths have very specialized guts and actually need to ingest dirt with their prey in order to digest them properly, and may even have a trick to extract energy from chitin.

When threatened, Barroths hit their attackers with their tail clubs and lower their massive heads and charge with the force of a freight train. But because they have such poor eyesight they may become hostile to things that don’t pose a threat or things that are protected by a threat, such as blos young. Barroths have five nostrils, or rather one trifurcated nostril and one bifurcated one. It’s unclear why this is, but it could be that when charging at objects they risk damaging and collapsing their nostrils and being unable to breathe through them, and by simply having more they can negate this issue.

A poorly studied arctic species has been documented, and has a vibrant blue and green hide and even bigger crown, but it’s unclear what it might prey on.

Both Barroth and the surprising relative Brachydios can trace their evolutionary history back to small omnivorous swamp dwelling ceratosaurs that rooted around for bugs, mushrooms, and tubers. As the environment changed, some decided to maintain their swamps while others adapted to the harsh volcanoes.

Brachydios: Agressive ceratosaurs famous for their pounders, blue obsidian-like carapace, and symbiotic slime mold.

In the harsh environment of volcanoes, Brachydios have become carnivores that prefer burrowing animals, but if a golden opportunity presents itself then they will take prey as large as Uragaan. Kills are processed by the two large claws on each hand, normally kept tucked away under the pounders.

Brachydios have a unique relationship with a species of myxomycete with possible relation to Physarum polycephalum, and this can be traced back to their evolutionary history. Because their ancestors were rootling creatures that searched in dark damp places for food such as under logs, they would have occasionally come into contact with the slime mold. This frequent contact would result in this amoeboid eventually growing on the ancestral Bracy’s carapace and sometimes eating it. Becoming a hitchhiking nuisance. But this slime also had a very literally explosive reproduction, which would be beneficial for unearthing food. Brachydios eventually learned to tolerate the amoeba eating its skin because it could be used to better forage. Modern Brachydios grow the carapace on their horn and pounders quicker than other parts of the body since that’s where most of the slime lives, with most of it living within the spongy bone and keratin of its forehead pounder and requiring compounds in its saliva to reproduce.

Exceptionally large and old Brachydios may acquire the poorly researched Fashpoint Slime and become known as Raging Brachydios. The flashpoint dazzles potential mates with its bright colors, but this may prove to be a detriment to the population in an area. Only the individuals that carry flashpoint can survive its blasts, and if any normal Brachydios survive mating with a raging then any young will certainly be killed by flashpoint slime that takes root on their shells.

Heterodontosaur brutes

Quematrice: A recently discovered species native to the forbidden lands that is exclusively a scavenger.

Despite their theropod-like appearance they and others like them are actually descended from heterodontosaurs. The ancestor of the entire family was likely primarily herbivorous with carrion and insect eating habits; essentially being adapted to a low protein diet rich in macronutrients. Many different taxa would either retain or lose the predentary or tusks.

Quematrice itself has lost the predentary but kept its tusks. The rest of the teeth have minimal serrations but are thick and sharp, perfect for piercing and cracking bone. This diet of dead flesh and bone may provide insight into how Uragaan gained its unique diet. By eating the bones of other monsters, which in the world of monster hunter are highly mineralized, the ancestors of Uragaan might have gradually evolved a gut microbiome that could better process other metals.

Quematrice are able to secrete an oil onto their skin on their tail, and use friction to ignite it and create threat displays. This unique oily skin secretion is a further link between it and the aans.

Radobaan: A member of the aan genus native to the rotten vale.

Radobaan has pointed spike scutes on its back as opposed to the flat studs of Uragaan, possibly as an adaptation for traction in the vale, and instead of cranial bosses it has horns. Outside of these physical differences though, Radobaan are outwardly the same as their sister species, with the biggest difference being internal. Radobaan has a different gut microbiome than Uragaan, and it can be thought of as somewhat in between Quematrice and Uragaan’s guts. Radobaan primarily feast on bone which is abundant in the vale, as well as the occasional plant and fungi to round out their diet.

Both anns process their food via their very unique cranial anatomy. Their mandibles are incredibly robust and the bones have largely fused together. This massive bludgeoning chin, while excellent at defending them from danger, can also crush meals into more manageable chunks. Their predentary forms a “lip” that can hook food and debris, and food shoveled into the mouth is processed by the teeth. The teeth of Uragaan and Radobaan are large, flat, and arranged in a zigzag, with two noticeable tusks. These teeth can grind food down into a fine powder and have deep roots.

Food is gradually broken down by a multi-chambered stomach. Gases extracted from the digestive process have narcotic effects and can be released through abdominal vents in self defense.

Both species can secrete a tar-like oil from their skin that they use to affix their food to their bodies for defense and to carry a portable meal.

Both species can curl themselves into a wheel shape to move quickly and efficiently across slanted terrain, and have appropriately tough backs for this task. It’s possible that their ancestors merely curled into a ball for protection like an armadillo or pangolin, but in the uneven terrain of volcanoes this might have accidentally resulted in rolling down hills away from danger. This eventually became an instinctual behavior to roll from danger and was further expanded into a method of movement.

Uragaan: A sister species to Radobaan found anywhere in the world with a volcano.

As explained above, Uragaan differ from Radobaan in that their back and cranial armor form flat pegs (which grow continuously throughout their lives), but their diet and gut biome are different as well. Uragaans are ore eaters, using the same tools useful in cracking and grinding bone to crush rock. To digest their meals they have an incredibly complex gut biome able to consume inorganic material and create organic byproducts that Uragaan itself can consume, much like the symbiotic microbes of creatures living around hydrothermal vents. The caveat to this is that these heterodontosaurs are choosy eaters and live life slowly. Much of their time is spent just digesting their meals.

Because of their diet of ore, Uragaan decorate themselves in metal as opposed to the bone of their sister species, making their bodies heavier. They also affix explosive rocks to their tails, which they can fling at threats and set off with an earth shattering chin slam. The chin itself is coated in melted metals. The gases they extract from digestion are also more diverse, and on top of narcotics they can also vent a hot combustible gas.

Uragaan start life small and herbivorous and don’t begin eating ore until strong enough to crack it. The species is also somewhat social and may engage in rough shoving matches as a form of play. During breeding season males dress themselves in colorful jewels and ore to impress mates. Particularly old individuals may even have crystals growing on them.

A subspecies exists called Steel Uragaan which makes excursions deeper into volcanoes for sulfur rich minerals. Because of this diet it cannot make sleep gas but can create foul smelling sulfuric gas. This repeated traversal between cooler and hotter areas of volcanoes effectively heat treats the metals on their bodies, which explains the colors.

Duramboros: A massive Heterodontosaur that lives in large forests.

Duramboros are primarily tree eaters, felling trees with their tails and eating the bark and other woody tissue. Like the aans they have multi-chambered stomachs for ruminating, and Duramboros do spend a lot of time just digesting food, and can sit in areas for so long that moss and fungi can grow on their shells. The species will also round out their diets by eating dead trees for the arthropods and fungi within. Their feeding can create open areas in dense forests, making them ecosystem engineers. Excess nutrients are stored in large fatty humps on their backs for lean periods.

Duramboros are incredibly well protected even outside of their sheer size. Their hide alone is like that of a rhino, and their massive horns supported by huge muscles on their humped back can gore and throw any lesser creatures with ease. Their massive tails are their greatest weapon, and sport a large club with axe-like thagomizers to completely obliterate any threat. They infamously use these tails as a counterbalance while spinning in place before launching their massive bodies at whatever it is they want to die.

The species usually lives in small herds composed of a few family groups, and newborns eat the dung of their mothers to gain the gut bacteria needed for fermentation, as is common with many fermenting herbivores.

A desert dwelling subspecies known as Rust Duramboros exists and is the largest brute wyvern on average. Due to their environment they are absent of any moss on their hide, and their tail club forms a double edged axe that they use more violently.

Dalthydon: A recently discovered species native to the windward plains and other savannas.

These small relatives of Duramboros primarily eat grass, which they graze using remarkably mammal-like lips which are only possible due to the complete loss of the predentary. Their social dynamics and method of digestion is largely the same as their bigger relatives.

Their head is adorned with a shield made entirely of horn, which is supported by large muscles that anchor to their humpback. Their tails also have rhino-like plating. Both are like duramboros.

Dalthydon are unusual for their production of milk, something dinosaurs can’t make as they lack sweat glands. It could be possible this structure is derived from a preening gland of some kind.

Banbaro: These heterodontosaurs inhabit regions with drastic seasonal differences.

These herbivores eat wood, other plants, and fungi which they ferment in their stomach. In terms of niche they’re like a more cold adapted Duramboros, and sport a thick coat of feathers and subcutaneous fat. During warmer periods they can raise their feathers and their carapace to better release heat. They also have a small nasal crest that lays flat but can be flipped up when angry as a form of display.

Duramboros, Banbaro, and their relatives all have hoofs, likely as a better method of shock absorption and weight bearing than normal toes.

Gastodon: A volcanic species with a puffy feather mane.

Both it and Kestodon have retained the predentary. Unlike the robust buffalo-like cranial structures of their relatives, their three curved horns are mostly for display but can gore threats.

Kestodon: A close relative to Gastodon with distinct sexual dimorphism and cranial anatomy.

Kestodons lack horns and instead have domeheads like pachycephalosaurs, and are used much the same way. Males are much bigger than females, and a typical heard consists of two sibling males and a small harem of females.

Other notes

Skull in the Jurassic frontier: A giant skull present within the Jurassic Frontier, its anatomy is unmistakably tyrannosaurid. But tyrannosaurids are no longer present in the world, meaning that they might have recently gone extinct. It’s possible that a radiation of kaiju sized tyrannosaurids were present within the world and were predators of other kaiju sized monsters such as the god wyverns or massive elders like Zorah, but may have gone extinct due to the decline in the diversity of massive monsters after the last ice age.

#monster hunter#speculative biology#speculative evolution#monsterhunter#monhun#monster hunter biology#speculative zoology#phylogeny#phylogenetics#taxonomy#cladistics#brute wyvern#deviljho#anjanath#glavenus#banbaro#duramboros#Brachydios#barroth

83 notes

·

View notes