#Peter Dizikes | MIT News

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

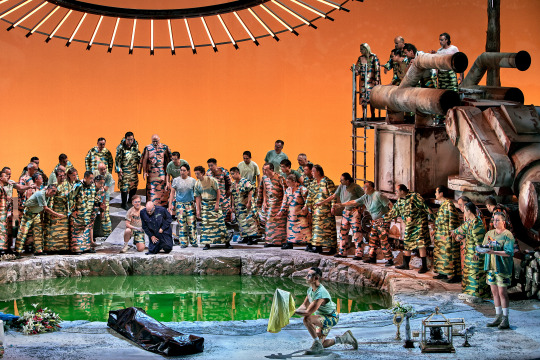

Q&A: A high-tech take on Wagner’s “Parsifal” opera Director and MIT Professor Jay Scheib’s production, at the Bayreuth Festival in Germany, features an apocalyptic theme and augmented reality headsets for the audience. https://news.mit.edu/2023/high-tech-take-wagners-parsifal-opera-0803

#Music#Augmented and virtual reality#Music and theater arts#Music technology#History#Arts#Technology and society#Climate change#Ethics#Social justice#History of science#Global#School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences#Peter Dizikes | MIT News#MIT News

0 notes

Text

How are cities managing record-setting temperatures?

Professor of urban and environmental planning David Hsu explains what municipal governments are doing as climate change accelerates.

Peter Dizikes | MIT News

July 2023 was the hottest month globally since humans began keeping records. People all over the U.S. experienced punishingly high temperatures this summer. In Phoenix, there were a record-setting 31 consecutive days with a high temperature of 110 degrees Fahrenheit or more. July was the hottest month on record in Miami. A scan of high temperatures around the country often yielded some startlingly high numbers: Dallas, 110 F; Reno, 108 F; Salt Lake City, 106 F; Portland, 105 F.

Climate change is a global and national crisis that cannot be solved by city governments alone, but cities suffering from it can try to enact new policies reducing emissions and adapting its effects. MIT’s David Hsu, an associate professor of urban and environmental planning, is an expert on metropolitan and regional climate policy. In one 2017 paper, Hsu and some colleagues estimated how 11 major U.S. cities could best reduce their carbon dioxide emissions, through energy-efficient home construction and retrofitting, improvements in vehicle gas mileage, more housing density, robust transit systems, and more. As we near the end of this historically hot summer, MIT News talked to Hsu about what cities are now doing in response to record heat, and the possibilities for new policy measures.

Q: We’ve had record-setting temperatures in many cities across the U.S. this summer. Dealing with climate change certainly isn’t just the responsibility of those cities, but what have they been doing to make a difference, to the extent they can?

A: I think this is a very top-of-mind question because even 10 or 15 years ago, we talked about adapting to a changed climate future, which seemed further off. But literally every week this summer we can refer to [dramatic] things that are already happening, clearly linked to climate change, and are going to get worse. We had wildfire smoke in the Northeast and throughout the Eastern Seaboard in June, this tragic wildfire in Hawaii that led to more deaths than any other wildfire in the U.S., [plus record high temperatures]. A lot of city leaders face climate challenges they thought were maybe 20 or 30 years in the future, and didn’t expect to see happen with this severity and intensity.

One thing you’re seeing is changes in governance. A lot of cities have recently appointed a chief heat officer. Miami and Phoenix have them now, and this is someone responsible for coordinating response to heat waves, which turn out to be one of the biggest killers among climatological effects. There is an increasing realization not only among local governments, but insurance companies and the building industry, that flooding is going to affect many places. We have already seen flooding in the seaport area in Boston, the most recently built part of our city. In some sense just the realization among local governments, insurers, building owners, and residents, that some risks are here and now, already is changing how people think about those risks.

Q: To what extent does a city being active about climate change at least signal to everyone, at the state or national level, that we have to do more? At the same time, some states are reacting against cities that are trying to institute climate initiatives and trying to prevent clean energy advances. What is possible at this point?

A: We have this very large, heterogeneous and polarized country, and we have differences between states and within states in how they’re approaching climate change. You’ve got some cities trying to enact things like natural gas bans, or trying to limit greenhouse gas emissions, with some state governments trying to preempt them entirely. I think cities have a role in showing leadership. But one thing I harp on, having worked in city government myself, is that sometimes in cities we can be complacent. While we pride ourselves on being centers of innovation and less per-capita emissions — we’re using less than rural areas, and you’ll see people celebrating New York City as the greenest in the world — cities are responsible for consumption that produces a majority of emissions in most countries. If we’re going to decarbonize society, we have to get to zero altogether, and that requires cities to act much more aggressively.

There is not only a pessimistic narrative. With the Inflation Reduction Act, which is rapidly accelerating the production of renewable energy, you see many of those subsidies going to build new manufacturing in red states. There’s a possibility people will see there are plenty of better paying, less dangerous jobs in [clean energy]. People don’t like monopolies wherever they live, so even places people consider fairly conservative would like local control [of energy], and that might mean greener jobs and lower prices. Yes, there is a doomscrolling loop of thinking polarization is insurmountable, but I feel surprisingly optimistic sometimes.

Large parts of the Midwest, even in places people think of as being more conservative, have chosen to build a lot of wind energy, partly because it’s profitable. Historically, some farmers were self-reliant and had wind power before the electrical grid came. Even now in some places where people don’t want to address climate change, they’re more than happy to have wind power.

Q: You’ve published work on which cities can pursue which policies to reduce emissions the most: better housing construction, more transit, more fuel-efficient vehicles, possibly higher housing density, and more. The exact recipe varies from place to place. But what are the common threads people can think about?

A: It’s important to think about what the status quo is, and what we should be preparing for. The status quo simply doesn’t serve large parts of the population right now. Heat risk, flooding, and wildfires all disproportionately affect populations that are already vulnerable. If you’re elderly, or lack access to mobility, information, or warnings, you probably have a lower risk of surviving a wildfire. Many people do not have high-quality housing, and may be more exposed to heat or smoke. We know the climate has already changed, and is going to change more, but we have failed to prepare for foreseeable changes that already here. Lots of things that are climate-related but not only about climate change, like affordable housing, transportation, energy access for everyone so they can have services like cooking and the internet — those are things that we can change going forward. The hopeful message is: Cities are always changing and being built, so we should make them better. The urgent message is: We shouldn’t accept the status quo.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

MIT Report: The Work of the Future

“Decades of technological change have polarized the earnings of the American workforce, helping highly educated white-collar workers thrive, while hollowing out the middle class. Yet present-day advances like robots and artificial intelligence do not spell doom for middle-tier or lower-wage workers, since innovations create jobs as well. With better policies in place, more people could enjoy good careers even as new technology transforms workplaces.”

“As technology takes jobs away, it provides new opportunities; about 63 percent of jobs performed in 2018 did not exist in 1940. Rather than a robot revolution in the workplace, we are witnessing a gradual tech evolution. At issue is how to improve the quality of jobs, particularly for middle- and lower-wage workers, and ensure there is greater shared prosperity than the U.S. has seen in recent decades.”

Major Conclusions

1. “Technological change is simultaneously replacing existing work and creating new work. It is not eliminating work altogether.”

2. “Momentous impacts of technological change are unfolding gradually.”

3. “Rising labor productivity has not translated into broad increases in incomes because societal institutions and labor market policies have fallen into disrepair.”

4. “Improving the quality of jobs requires innovation in labor market institutions.”

5. “Fostering opportunity and economic mobility necessitates cultivating and refreshing worker skills.”

6. “Investing in innovation will drive new job creation, speed growth, and meet rising competitive challenges.”

MIT News, November 17, 2020: “Report outlines route toward better jobs, wider prosperity,” by Peter Dizikes (links in article broken use link below for report)

MIT, 2020: The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines (100 pages, PDF)

Click here to learn more about this year’s AI and Work of the Future Congress hosted virtually by MIT.

#work of the future#ai#artificial intelligence#technological change#labor productivity#innovation#future of work#economic mobility#labor market#job creation#job replacement#tech evolution#MIT

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Renée Fleming presenting on “Music and the Mind” at MIT.

[In response to one query, Fleming said her favorite role was the Marschallin from “Der Rosenkavalier,” the Richard Strauss opera that premiered in 1911.

Fleming also noted that the intense drama of many classical operas provides a necessary emotional outlet for their audiences, perhaps now more than ever.

“Difficult emotions need to be expressed sometimes,” Fleming said. “Many of us are frankly today working 24/7, so we need those moments to let down and feel something.”]

Image: Jake Belcher

Source: Peter Dizikes, MIT News

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do we influence social media algorithms, or does it influence us?

Social media algorithm is a sophisticated mechanism that customizes your feed to your interests. At a first glance, it is helpful for all parties involved; users see engaging and relevant content, companies get a chance to advertise their product to the target audience, and the social media platform gets higher user engagement. Unfortunately, a deeper analysis indicates that some significant drawbacks affect users and society overall. The goal of the suggestion algorithm is to keep the users on a platform for as long as possible; it doesn’t hesitate to use misinformation, play with emotions, and limit exposure to alternative information.

Emotionally charged content wins

The most engaging content makes the users experience strong emotions (1) such as anger, frustration, and fear. The posts that invoke such feelings get more attention. Even if the information should not cause such emotions, it can be exaggerated and presented in a way that will get a more emotional response and engagement from users. Such a strategy does not only contribute to the misinformation problem but also prioritizes emotionally charged publications over potentially more important ones. It is also partially a reason why fake news spread faster (2) since they tend to be more surprising and triggering for people. In the long run, algorithm choices have damaging effects on the mental health of the users and push content creators to alter their publications for the sake of being prioritized in the feed.

Political polarization and radicalization

The algorithm tends to keep its users in their “bubbles” without exposing them to alternative perspectives. In such an environment users are more susceptible to confirmation bias which leads them to hold even stronger opinions based on the information that only confirms their beliefs. The political discussion is heavily affected by the algorithm since people are mostly consuming the information that is in alignment with their political opinions. Eventually, society becomes more polarized (3) and has a less common understanding of the situation despite the availability of various sources online. The emergence and growth of online radical groups come with no surprise on such platforms and to a large extent is the outcome of the suggestion algorithm.

Shapes our online identity

The algorithm successfully identifies users’ main interests, but it simplifies them. It chooses to focus on a few types of content that the person enjoys and limits opportunities for exploration. It has the power to dictate what users watch and read, and, likely, the user will not encounter content outside of the algorithm’s suggestions unless they actively look for it. The online identity of a user is largely influenced by suggestions, which in turn affects their offline interests, choices, and identity overall.

Ultimately, the suggestion algorithm is a powerful tool that might have significant damage to social media users if it is not controlled and adjusted adequately. The users should understand the extent of its influence on their lives and keep the companies responsible for the potential damage and misuse of the power of the algorithm.

Sources:

1. Ferrara, E., & Yang, Z. (n.d.). Measuring emotional contagion in social media. PLOS ONE. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0142390

2. Peter Dizikes | MIT News Office. “Study: On Twitter, False News Travels Faster than True Stories.” MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, https://news.mit.edu/2018/study-twitter-false-news-travels-faster-true-stories-0308.

3. Willer, A. B. R., Boutyline, A., & Willer, R. (2017, June 1). The social structure of political echo chambers: Variation in ideological homophily in online networks. Stanford Graduate School of Business. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/social-structure-political-echo-chambers-variation-ideological

Additional sources:

4. Lewis, P. (2018, February 2). 'fiction is outperforming reality': How YouTube's algorithm distorts truth. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/feb/02/how-youtubes-algorithm-distorts-truth

5. Lewis Mitchell Senior Lecturer in Applied Mathematics, & James Bagrow Associate Professor. (2022, March 28). Do social media algorithms erode our ability to make decisions freely? the jury is out. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/do-social-media-algorithms-erode-our-ability-to-make-decisions-freely-the-jury-is-out-140729

6. Bell, E. (2021, February 28). How social media algorithms are increasing political polarisation. youngausint. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://www.youngausint.org.au/post/how-social-media-algorithms-are-increasing-political-polarisation

0 notes

Quote

There is a contrast in environmental philosophy I wanted to highlight,” Mavhunga says. The African approach centered on “strategic deployments within the environment,” as Mavhunga puts it in the book, including “careful siting of settlements, avoiding the potentially pestiferous insect’s territory.” But the Europeans, he adds, were intent on “destroying species they designated vermin beings, and by any means necessary — slaughtering the host and food source animals, massacring whole forests, poisoning the environment with deadly pesticides whose environmental pollution consequences we are yet to study and understand, including possible links to cancers.”

Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga quoted in an article by Peter Dizikes at MIT News. How Africans developed scientific knowledge of the deadly tsetse fly

The Mobile Workshop: The Tsetse Fly and African Knowledge Production

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Q&A] Read the article "Economists find evidence for famous hypothesis of ‘comparati

[Q&A] Read the article “Economists find evidence for famous hypothesis of ‘comparati

Read the article “Economists find evidence for famous hypothesis of ‘comparative advantage’” by Peter Dizikes published on MIT News in 2012. This article discusses a paper by Arnaud Costinot and Dave Donaldson. In your submission, consider answering the following questions: What hypothesis do the authors aim to test in this paper? To test the hypothesis, what do they measure and using what…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

[Q&A] Read the article "Economists find evidence for famous hypothesis of ‘comparati

[Q&A] Read the article “Economists find evidence for famous hypothesis of ‘comparati

Read the article “Economists find evidence for famous hypothesis of ‘comparative advantage’” by Peter Dizikes published on MIT News in 2012. This article discusses a paper by Arnaud Costinot and Dave Donaldson. In your submission, consider answering the following questions: What hypothesis do the authors aim to test in this paper? To test the hypothesis, what do they measure and using what…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The writing on the wall

The writing on the wall

By Peter Dizikes | MIT News Office

When and where did humans develop language? To find out, look deep inside caves, suggests an MIT professor.

More precisely, some specific features of cave art may provide clues about how our symbolic, multifaceted language capabilities evolved, according to a new paper co-authored by MIT linguist Shigeru Miyagawa.

A key to this idea is that cave art is…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Advancing social studies at MIT Sloan

Associate Professor Dean Eckles studies how our social networks affect our behavior and shape our lives.

Peter Dizikes | MIT News

Around 2010, Facebook was a relatively small company with about 2,000 employees. So, when a PhD student named Dean Eckles showed up to serve an intership at the firm, he landed in a position with some real duties.

Eckles essentially became the primary data scientist for the product manager who was overseeing the platform’s news feeds. That manager would pepper Eckles with questions. How exactly do people influence each other online? If Facebook tweaked its content-ranking algorithms, what would happen? What occurs when you show people more photos?

As a doctoral candidate already studying social influence, Eckles was well-equipped to think about such questions, and being at Facebook gave him a lot of data to study them.

“If you show people more photos, they post more photos themselves,” Eckles says. “In turn, that affects the experience of all their friends. Plus they’re getting more likes and more comments. It affects everybody’s experience. But can you account for all of these compounding effects across the network?”

Eckles, now an associate professor in the MIT Sloan School of Management and an affiliate faculty member of the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society, has made a career out of thinking carefully about that last question. Studying social networks allows Eckles to tackle significant questions involving, for example, the economic and political effects of social networks, the spread of misinformation, vaccine uptake during the Covid-19 crisis, and other aspects of the formation and shape of social networks. For instance, one study he co-authored this summer shows that people who either move between U.S. states, change high schools, or attend college out of state, wind up with more robust social networks, which are strongly associated with greater economic success.

Eckles maintains another research channel focused on what scholars call “causal inference,” the methods and techniques that allow researchers to identify cause-and-effect connections in the world.

“Learning about cause-and-effect relationships is core to so much science,” Eckles says. “In behavioral, social, economic, or biomedical science, it’s going to be hard. When you start thinking about humans, causality gets difficult. People do things strategically, and they’re electing into situations based on their own goals, so that complicates a lot of cause-and-effect relationships.”

Eckles has now published dozens of papers in each of his different areas of work; for his research and teaching, Eckles received tenure from MIT last year.

Five degrees and a job

Eckles grew up in California, mostly near the Lake Tahoe area. He attended Stanford University as an undergraduate, arriving on campus in fall 2002 — and didn’t really leave for about a decade. Eckles has five degrees from Stanford. As an undergrad, he received a BA in philosophy and a BS in symbolic systems, an interdisciplinary major combining computer science, philosophy, psychology, and more. Eckles was set to attend Oxford University for graduate work in philosophy but changed his mind and stayed at Stanford for an MS in symbolic systems too.

“[Oxford] might have been a great experience, but I decided to focus more on the tech side of things,” he says.

After receiving his first master’s degree, Eckles did take a year off from school and worked for Nokia, although the firm’s offices were adjacent to the Stanford campus and Eckles would sometimes stop and talk to faculty during the workday. Soon he was enrolled at Stanford again, this time earning his PhD in communication, in 2012, while receiving an MA in statistics the year before. His doctoral dissertation wound up being about peer influence in networks. PhD in hand, Eckles promptly headed back to Facebook, this time for three years as a full-time researcher.

“They were really supportive of the work I was doing,” Eckles says.

Still, Eckles remained interested in moving into academia, and joined the MIT faculty in 2015 with a position in MIT Sloan’s Marketing Group. The group consists of a set of scholars with far-ranging interests, from cognitive science to advertising to social network dynamics.

“Our group reflects something deeper about the Sloan school and about MIT as well, an openness to doing things differently and not having to fit into narrowly defined tracks,” Eckles says.

For that matter, MIT has many faculty in different domains who work on causal inference, and whose work Eckles quickly cites — including economists Victor Chernozhukov and Alberto Abadie, and Joshua Angrist, whose book “Mostly Harmless Econometrics” Eckles name-checks as an influence.

“I’ve been fortunate in my career that causal inference turned out to be a hot area,” Eckles says. “But I think it’s hot for good reasons. People started to realize that, yes, causal inference is really important. There are economists, computer scientists, statisticians, and epidemiologists who are going to the same conferences and citing each other’s papers. There’s a lot happening.”

How do networks form?

These days, Eckles is interested in expanding the questions he works on. In the past, he has often studied existing social networks and looked at their effects. For instance: One study Eckles co-authored, examining the 2012 U.S. elections, found that get-out-the-vote messages work very well, especially when relayed via friends.

That kind of study takes the existence of the network as a given, though. Another kind of research question is, as Eckles puts it, “How do social networks form and evolve? And what are the consequences of these network structures?” His recent study about social networks expanding as people move around and change schools is one example of research that digs into the core life experiences underlying social networks.

“I’m excited about doing more on how these networks arise and what factors, including everything from personality to public transit, affect their formation,” Eckles says.

Understanding more about how social networks form gets at key questions about social life and civic structure. Suppose research shows how some people develop and maintain beneficial connections in life; it’s possible that those insights could be applied to programs helping people in more disadvantaged situations realize some of the same opportunities.

“We want to act on things,” Eckles says. “Sometimes people say, ‘We care about prediction.’ I would say, ‘We care about prediction under intervention.’ We want to predict what’s going to happen if we try different things.”

Ultimately, Eckles reflects, “Trying to reason about the origins and maintenance of social networks, and the effects of networks, is interesting substantively and methodologically. Networks are super-high-dimensional objects, even just a single person’s network and all its connections. You have to summarize it, so for instance we talk about weak ties or strong ties, but do we have the correct description? There are fascinating questions that require development, and I’m eager to keep working on them.”

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr!

0 notes

Text

How to Make Technology Help Us, Not Replace Us

“Automation is not likely to eliminate millions of jobs any time soon — but the U.S. still needs vastly improved policies if Americans are to build better careers and share prosperity as technological changes occur, according to a new MIT report about the workplace. The report, which represents the initial findings of MIT’s Task Force on the Work of the Future, punctures some conventional wisdom and builds a nuanced picture of the evolution of technology and jobs, the subject of much fraught public discussion.”

“The likelihood of robots, automation, and artificial intelligence (AI) wiping out huge sectors of the workforce in the near future is exaggerated, the task force concludes — but there is reason for concern about the impact of new technology on the labor market. In recent decades, technology has contributed to the polarization of employment, disproportionately helping high-skilled professionals while reducing opportunities for many other workers, and new technologies could exacerbate this trend. Moreover, the report emphasizes, at a time of historic income inequality, a critical challenge is not necessarily a lack of jobs, but the low quality of many jobs and the resulting lack of viable careers for many people, particularly workers without college degrees. With this in mind, the work of the future can be shaped beneficially by new policies, renewed support for labor, and reformed institutions, not just new technologies.”

MIT News, September 4, 2019: “MIT report examines how to make technology work for society,” by Peter Dizikes

MIT Work of the Future, Fall 2019: “The Work of the Future: Shaping Technology and Institutions” (60 pages, PDF)

Bloomberg, September 4, 2019: “How to Make Sure Robots Help Us, Not Replace Us,” by Peter Coy

#technology#technological change#institutions#AI#automation#artificial intelligence#the future of work#future of work#careers

1 note

·

View note

Text

USA: State-level R&D tax credits spur growth of new businesses

- By Peter Dizikes , MIT News Office -

Here’s some good news for U.S. states trying to spur an economic recovery in the years ahead: The R&D tax credit has a significant effect on entrepreneurship, according to a new study led by an MIT professor.

Moreover, the study finds a striking contrast between two types of tax credits. While the R&D tax credit fuels high-quality new-firm growth, the state-level investment tax credit, which supports general business needs, actually has a slightly negative economic effect on that kind of innovative activity.

The underlying reason for the difference, the study’s authors believe, is that R&D tax credits, which are for innovative research and development, help ambitious startup firms flourish. But when states are simply granting investment tax credits, allowing long-established firms to expand, they are supporting businesses with less growth ahead of them, and thus not placing winning policy bets over time.

“What we see is an improvement in the environment for entrepreneurship in general, specifically for those growth-oriented startups that ultimately are the engine of business dynamism,” says MIT economist Scott Stern, co-author of a newly published paper detailing the study’s results.

“States that introduced R&D tax credits set the table for increased entrepreneurship,” says Catherine Fazio MBA ’14, a co-author of the study and research affiliate at the MIT Lab for Innovation Science and Policy.

Specifically, the study finds that — other things being equal, and accounting for existing growth trends — areas introducing R&D tax credits experience a 20 percent rise in high-quality new-firm-formation over a 10-year period, whereas areas using investment tax credits see a 12 percent drop in high-quality firm growth, also over a 10-year period.

“The investment tax credit arguably reinforces the strength of big business in these states, and that might create a barrier to entry for new firms,” Stern explains. “It might harm entrepreneurship. But the R&D tax credit facilitates knowledge, facilitates science, facilitates exactly the sorts of things that can spur new ideas, and spurring new ideas is the key for our entrepreneurial ecosystem.”

Indeed, adds Jorge Guzman MBA ’11, PhD ’17, a management professor and co-author of the study, “States offering both R&D and investment tax credits in an effort to stimulate high-growth entrepreneurship may actually be offering incentives that work at cross purposes to each other.”

The paper, “The Impact of State-Level Research and Development Tax Credits on the Quality and Quantity of Entrepreneurship,” appears in the latest issue of Economic Development Quarterly. Fazio is also a lecturer at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business; Guzman is an assistant professor at the Columbia Business School of Columbia University; and Stern is the David Sarnoff Professor of Management of Technology at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Third year is the take-off point

The R&D tax credit was introduced in 1981 at the federal level, with states soon adding it to their own policy toolkits. From 1981 through 2006, 32 states have implemented R&D tax credits. At the same time, 20 states granted investment tax credits. Yet no study has specifically examined the impact of state R&D tax credits on new firms.

“A classical question that had previously resisted empirical scrutiny was the impact of the state-level R&D tax credit on entrepreneurship,” Stern says. Moreover, he adds, it’s reasonable to question how effective the policy might be: “Growth-oriented startups don’t pay a lot of taxes upfront, so it’s not clear how salient taxes would be for entrepreneurship.”

To conduct the study, the researchers used a unique database they have created: the Startup Cartography Project, which features about 30 years of data on business formation and startup quality — including data showing the likelihood of success for new firms based on their key characteristics. (For instance, firms that seek intellectual property protection, or are organized to attract further equity financing, are more likely to succeed).

The scholars also used the Upjohn Panel Data on Incentives and Taxes, which contain detailed records of state tax policies, collected by Timothy Bartik, a senior economist at the W.J. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

By evaluating tax policy changes alongside changes in business activity, the researchers could assess the state-level effects of the R&D tax credit. Crucially, the study not only tallies firm formation, but also analyzes the quality of those startup firms and the development of local innovation ecosystems, to measure the full impact of the policy changes.

Ultimately the study examined 25 states where the two data sets overlapped thoroughly from 1990 to 2010, with the R&D tax credit available to companies in counties within these states 46 percent of the time.

By examining before-and-after data around the introduction of the state-level R&D tax credit, the researchers concluded that the policy change created more startup activity.

Intriguingly, the study found that the third year after the introduction of the R&D tax credit is the real take-off point for entrepreneurship in a state, with a roughly 2 percent annual growth in high-quality firm formation from that year through the 14th year after the policy change.

“It takes a few years for that impact to make its way through the system,” Stern says. “If you expect a one-year payoff from this, that’s too short.”

To be clear, many large businesses have long featured active R&D arms, and may also benefit from the state-level R&D tax credit. Indeed, Stern says, the current study was partly motivated by policymakers’ past focus on the benefits of tax credits for major corporations. Those may be real enough, but they are not the sole area of influence for the R&D tax credit.

“The policy discussion has mostly focused on lowering the burden on, and providing incentives for, investment for big business,” Stern says. “Right now Amazon, for example, takes a very large R&D tax credit. And it can say, ‘Do you like your Amazon Echo or Alexa and your crowdsourcing services? Well, all that came from our R&D.’” At the same time, Stern adds, “If the main policy rationale has always been to help big business, over time, [people in] public policy have discussed if it also helps startups.” The study now brings data to that conversation.

The long road ahead

The current study started well before the Covid-19 crisis, which has led to a massive rise in unemployment and severe problems and uncertainty for small businesses. To be clear, Stern observes, any reasonable recovery will require policy tools that extensively reach long-existing types of firms, rather than just depending on new growth.

“In this particular economic crisis, and public health crisis, we’re going to need to be restoring Main Street in a really important way,” Stern says. That means helping local restaurants, retail stores, and many other traditional small businesses, Stern emphasizes. As part of his ongoing work, he is now examining new business registrations of all kinds this spring, in the midst of the pandemic.

Still, the damage from the recovery has been so vast that efforts to bounce back must take multiple tracks — including incentives for innovative firms that might fill business needs created by the Covid-19 crisis.

“While no one can predict the future, we know that the actual economic recovery is going to depend on restoring business dynamism,” Stern says. “And that means we need to start getting new entrants, and make new entrepreneurship easier and better.”

States willing to give R&D tax relief to firms could well see the tactic spurring on part of a larger, eventual recovery.

“The R&D tax credit is one of the few innovation policy instruments that at relatively low administrative cost, can make a big difference for spurring innovation and entrepreneurship within a region,” Stern emphasizes. “You have to be committed to it. You have got to be patient. But it does pay off.”

--

Full study: “The Impact of State-Level Research and Development Tax Credits on the Quantity and Quality of Entrepreneurship”, Economic Development Quarterly.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0891242420920926

Source: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Read Also

The myth of the young entrepreneur

0 notes

Text

What should be considered when we think of the future?

While the future of our earth seems largely uncertain, one thing is for sure: we need to help save our planet now. If we do not take action soon, any and all damage to our earth that we have caused can become irreversible, which will only harm our future as a human race. In Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin’s The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene, they focus on the human race’s role in the current time period, the anthropocene, which is “the epoch where the human component of the Earth system is large enough to affect how it functions” (Lewis & Maslin, p. 399). Lewis and Maslin look to the future and lay out the possibilities, including business as normal, a societal collapse akin to the Mayan and Roman Empires, or a transition to a completely new society with a different living style compared to present day society. In order for business to continue as normal and for society to maintain its current outputs and consumption habits, consumerism must tackle the most pressing issue of the environment and the harm that humans have caused to avoid societal collapse or switching to a different way of living, which is possible considering new governmental reforms, increased health and lifespans, improved nutrition, and more.

If collapse was to occur, it requires a drastic decline in societal complexity, which is unlikely, but will most likely “take the form of private property and a free labor based capitalist mode of living” (Lewis & Maslin, p. 370) in the event of its occurrence. However, the authors estimate that it is more likely that, as humans, we will have to address the harm we have caused to the environment and transition to a different way of life that will highlight sustainability and efficiency. The authors particularly contribute to the future switch to a more efficient and sustainable society to the current process of a positive feedback look in our capitalist society, which tends to move towards new standards for stability. As capitalism currently develops, it utilizes the scientific method to improve current technologies and depends on the constant cycle of investing profits into products. Our current society will eventually transform society into something more elevated than what we have now if we address our earth’s environmental issues. In order to preserve our earth, we must recognize its issues, adapt, and collaborate as human beings with an interconnected web of ideas. Currently, we utilize our developing technology to manufacture and advance renewable energy as an attempt to minimize carbon emissions and our fossil fuel usage. Minimizing fossil fuel usage allows the human race to begin its journey towards more sustainable living.

Deepwater Horizon oil spill by BP in the Gulf of Mexico in 2011 (Broder, 2011)

However, minimizing fossil fuel usage is more complicated than we would think. Lewis and Maslin identify geopolitics as a barrier to fully eliminative fossil fuel usage, which is subsidized at about $5 trillion USD per year and most of the oil and gas companies worldwide are “partly or fully nationalized” (Lewis & Maslin, p. 383). Usage of fossil fuels not only has carbon emissions, but also causes land degradation, water pollution from leaks or spills, and wastewater from fracking. A widely recommended idea on minimizing fossil fuel usage that is more attainable than fully eliminating it is to invest in renewable energy and/or to create a carbon tax, which is backed by energy economists like MIT Sloan School of Management’s Christopher Knittel (Dizikes, 2016). Despite all the negatives on fossil fuel usage, we are making progress, with prices of renewable energy technology decreasing over the past decade and making it more accessible. Lewis and Maslin additionally highlight the negative feedback cycles on earth, which affect human supplies like crops. Negative feedback cycles work to stabilize climates, but overcorrect and leave weather patterns to become more unpredictable. Negative feedback cycles also increase the frequency of large climate events like drought, increase extreme weather events like tsunamis, which can disrupt the global food supply, cause rise in food prices, and result in civil unrest and refugee flows between countries to avoid conflict (Lewis & Maslin, p. 385).

To benefit our earth, Lewis and Maslin identify the issue: the Anthropocene conundrum. The Anthropocene conundrum is how to equalize resource consumption across the world within sustainable environmental limits, which the authors believe the solution is primarily with globally coordinated action towards equality between more developed and less developed nations; specifically, more developed nations (high-carbon emitting countries) should be doing more than others to reduce emissions and providing support to less developed nations to transition to renewable energy.

While Lewis and Maslin identify various possibilities surrounding our earth’s and society’s future, they do not propose a definite plan but just suggestions with its possible positive and negative results. E.O Wilson, a biologist and professor emeritus at Harvard University, proposes to devote half of the earth’s surface to nature to avoid mass extinction of species; specifically, Wilson proposes that we devote biological hotspots to protect those species of animals and elaborates on his Half Earth idea in his book, Half Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. Lewis and Maslin discuss E.O. Wilson’s Half Earth proposal, but determined that it is too large of a step for society and, while it would be effective, it would be more complicated to integrate than how Wilson proposes it.

Andrew Yang in Manhattan’s Washington Square Park during a presidential campaign rally in 2019. (Stevens & Grullon Paz, 2020)

Lastly, Lewis and Maslin discuss implementing a universal basic income to decrease interdependence in society, which would decrease the likelihood of massive societal collapse. Most recently, universal basic income has become a hot topic with former 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang making it a central point for his campaign. Yang’s focal point was a universal basic income of $1,000 per month, but Yang pressed for this because he argued that soon there would be increased automation in lieu of jobs and Americans would find themselves out of work. While in the current situation people are not losing their jobs for automation, but they are losing their jobs due to the current COVID-19 pandemic. With the CARES Act passed in March 2020, there has been an increased push for a universal basic income into legislation with unemployment being projected up to 16% later in 2020 (Solender, 2020). The benefits of a universal basic income include bringing many out of extreme poverty and providing a better alternative than the United States’ current unemployment program. I am not personally an Andrew Yang supporter, but he raises an interesting idea that should be considered. Despite not knowing what the future holds for our earth, we can reduce our own created inequality by implementing a universal basic income and allowing some individuals the luxury to begin to worry about something else other than where they will get their next meal from. We can heal our earth, but only by healing the divides between one another first.

Word Count: 1171/1100

Question: How can we begin to implement a universal basic income in the United States with people being so hesitant to embrace Andrew Yang’s platform when initiating the push for a UBI?

Bibliography

Broder, John M. “BP Shortcuts Led to Gulf Oil Spill, Report Says.” The New York Times. The New York Times, September 14, 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/15/science/earth/15spill.html.

Denchak, Melissa. “Fossil Fuels: The Dirty Facts.” NRDC, July 16, 2019. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/fossil-fuels-dirty-facts.

Dizikes, Peter. “Will We Ever Stop Using Fossil Fuels?” MIT News. MIT News Office, February 24, 2016. http://news.mit.edu/2016/carbon-tax-stop-using-fossil-fuels-0224.

“Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life.” EO Wilson Biodiversity Foundation. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://eowilsonfoundation.org/half-earth-our-planet-s-fight-for-life/.

Lewis, Simon, and Mark Maslin. The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene: a Pelican Book. Pelican, 2018.

Solender, Andrew. “Pushing Universal Basic Income, Andrew Yang Supporters Get #CongressPassUBI Trending.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, April 24, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewsolender/2020/04/24/pushing-universal-basic-income-andrew-yang-supporters-get-congresspassubi-trending/#a6984925d30c.

Stevens, Matt, and Isabella Grullón Paz. “Andrew Yang's $1,000-a-Month Idea May Have Seemed Absurd Before. Not Now.” The New York Times. The New York Times, March 18, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/us/politics/universal-basic-income-andrew-yang.html.

0 notes

Text

Our itch to share helps spread Covid-19 misinformation

To stay current about the Covid-19 pandemic, people need to process health information when they read the news. Inevitably, that means people will be exposed to health misinformation, too, in the form of false content, often found online, about the illness.

Now a study co-authored by MIT scholars contains bad news and good news about Covid-19 misinformation — and a new insight that may help reduce the problem.

The bad news is that when people are consuming news on social media, their inclination to share that news with others interferes with their ability to assess its accuracy. The study presented the same false news headlines about Covid-19 to two groups of people: One group was asked if they would share those stories on social media, and the other evaluated their accuracy. The participants were 32.4 percent more likely to say they would share the headlines than they were to say those headlines were accurate.

“There does appear to be a disconnect between accuracy judgments and sharing intentions,” says MIT professor David Rand, co-author of a new paper detailing the findings. “People are much more discerning when you ask them to judge the accuracy, compared to when you ask them whether they would share something or not.”

The good news: A little bit of reflection can go a long way. Participants who were more likely to think critically, or who had more scientific knowledge, were less likely to share misinformation. And when asked directly about accuracy, most participants did reasonably well at telling true news headlines from false ones.

Moreover, the study offers a solution for over-sharing: When participants were asked to rate the accuracy of a single non-Covid-19 story at the start of their news-viewing sessions, the quality of the Covid-19 news they shared increased significantly.

“The idea is, if you nudge them about accuracy at the outset, people are more likely to be thinking about the concept of accuracy when they later choose what to share. So then they take accuracy into account more when they make their sharing decisions,” explains Rand, who is the Erwin H. Schell Associate Professor with joint appointments at the MIT Sloan School of Management and the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

The paper, “Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy nudge intervention,” appears in Psychological Science. Besides Rand, the authors are Gordon Pennycook, an assistant professor of behavioral science at the University of Regina; Jonathan McPhetres, a postdoc at MIT and the University of Regina who is starting a position in August as an assistant professor of psychology at Durham University; Yunhao Zhang, a PhD student at MIT Sloan; and Jackson G. Lu, the Mitsui Career Development Assistant Professor at MIT Sloan.

Thinking, fast and slow

To conduct the study, the researchers conducted two online experiments in March, with a total of roughly 1,700 U.S. participants between them, using the survey platform Lucid. Participants matched the nation’s distribution of age, gender, ethnicity, and geographic region.

The first experiment had 853 participants, and used 15 true and 15 false news headlines about Covid-19, in the style of Facebook posts, with a headline, photo, and initial sentence from a story. The participants were split into two groups. One group was asked if the headlines were accurate; the second group was asked if they would consider sharing the posts on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

The first group correctly judged the stories’ accuracy about two-thirds of the time. The second group might therefore be expected to share the stories at a similar rate. However, the participants in the second group shared about half of the true stories, and just under half of the false stories — meaning their judgment about which stories to share was almost random in regard to accuracy.

The second study, with 856 participants, used the same group of headlines and again split the participants into two groups. The first group simply looked at the headlines and decided whether or not they would share them on social media.

But the second group of participants were asked to evaluate a non-Covid-19 headline before they made decisions about sharing the larger group of Covid-19 headlines. (Both studies were focused on headlines and the single sentence of text, since most people only read headlines on social media.) That extra step, of evaluating one non-Covid-19 headline, made a substantial difference. The “discernment” score of the second group — the gap between the number of accurate and inaccurate stories they shared — was almost three times larger than that of the first group.

The researchers evaluated additional factors that might explain tendencies in the responses of the participants. They gave all participants a six-item Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT), to evaluate their propensity to analyze information, rather than relying on gut instincts; evaluated how much scientific knowledge participants had; and looked at whether respondents were located close to Covid-19 outbreaks, among other things. They found that participants who scored higher on the CRT, and knew more about science, rated headlines more accurately and shared fewer false headlines.

Those findings suggest that the way people assess news stories has less to do with, say, preset partisan views about the news, and a bit more to do with their broader cognitive habits.

“A lot of people have a very cynical take on social media and our moment in history, that we’re post-truth and no one cares about the truth any more,” Pennycook says. “Our evidence suggests it’s not that people don’t care; it’s more that they’re distracted.”

Something systemic about social media

The study follows others Rand and Pennycook have conducted about explicitly political news, which similarly suggest that cognitive habits, more so than partisan views, influence the way people judge the accuracy of news stories and lead to the sharing of misinformation. In this study, the scholars wanted to see if readers analyzed Covid-19 stories, and health information, differently than political information. But the results were generally similar to the political-news experiments the researchers have conducted.

“Our results suggest that the life-and-death stakes of Covid-19 do not make people suddenly take accuracy into [greater] account when they’re deciding what to share,” Lu says.

Indeed, Rand suggests, the very importance of Covid-19 as a subject may interfere with readers’ ability to analyze it.

“Part of the issue with health and this pandemic is that it’s very anxiety-inducing,” Rand says. “Being emotionally aroused is another thing that makes you less likely to stop and think carefully.”

Still, the central explanation, the scholars think, is simply the structure of social media, which encourages rapid browsing of news headlines, elevates splashy news items, and rewards users who post eye-catching news, by tending to give them more followers and retweets, even if those stories happen to be untrue.

“There is just something more systemic and fundamental about the social media context that distracts people from accuracy,” Rand says. “I think part of it is that you’re getting this instantaneous social feedback all the time. Every time you post something, you immediately get to see how many people liked it. And that really focuses your attention on: How many people are going to like this? Which is different from: How true is this?”

The research was supported by the Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Initiative of the Miami Foundation; the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation; the Omidyar Network; the John Templeton Foundation; the Canadian Institute of Health Research; and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Peter Dizikes | MIT News Office

Press Contact

Abby Abazorius Email: [email protected] Phone: 617-253-2709 MIT News Office

source https://scienceblog.com/517304/our-itch-to-share-helps-spread-covid-19-misinformation/

0 notes

Text

#Redes Cómo la "información gerrymandering" influye en los votantes

#Redes #Gerrymandering El estudio analiza cómo las redes pueden distorsionar las percepciones de los votantes y cambiar los resultados electorales.

Peter Dizikes | MIT News Office

Muchos votantes hoy parecen vivir en burbujas partidistas, donde reciben solo información parcial sobre cómo se sienten los demás con respecto a cuestiones políticas. Ahora, un experimento desarrollado en parte por investigadores del MIT arroja luz sobre cómo este fenómeno influye en las personas cuando votan.

El experimento, que colocó a los participantes en…

View On WordPress

0 notes