#Petar Blagojevich

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Kisiljevo, Village Serbia

#Kisiljevo#Serbia#vampire#vampire lore#vampire story#petar Blagojevich#undead#vampire tourism#dark tourism#heritage tourism#historical tourism#travel#travelfacts#tourism#worldfacts#Serbia tourism

0 notes

Photo

The Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser

Sat 8 Mar 1851

Page 1-2

Reprinted: From the Glasgow Herald.

THE VAMPIRE SUPERSTITION

https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/101736844

Note: Trove Auto-transcriber errors have been corrected, but period spelling was left intact.

THE VAMPIRE SUPERSTITION.

[From the "Glasgow Herald."]

Most of our readers are, we dare say, acquainted with the general nature of the vampire superstition, but few of them are in possession of the curious facts out of which that superstition has arisen, and fewer still are probably aware of the terrible consternation which, in the early part of the last century, it caused in Servia and the districts adjacent to Belgrade. It is a most extraordinary idea, that the dead should arise from their graves, and prowl about the country for the purpose of sucking the blood of the living, and yet this is the genuine notion of vampirism. By some writers, the original of the vampire superstition is referred to the habits of a peculiar kind of bat, which, in hot climates, gently fans sleeping persons with its wings, while it bleeds them to death; but from the statement about to be made, it will be evident that this can by no means account for its "rise and progress." In a note to his poem of the "Giaour," Lord Byron says, "The vampire superstition is still general in the Levant. Honest Tournefort tells us a long story which Mr. Southey, in the notes on Thalaba, quotes about these 'Vroucolocha,' as he calls them. The Roman term is 'Vardoulacha.' I recollect a whole family being terrified by the scream of a child, which they imagined must proceed from such a visitation. The Greeks never mention the word without horror."

The best original account that we have seen of the ravages committed rather more than a century ago by the vampires, is contained in the third volume of a scientific publication printed at Paris in the year 1758, and entitled "Bibliotheque de Physique et d'Histoire Naturelle" The narrative referred to forms the second division of the sixty-third articles, the title of which is, "Observations Physiques sur l'embrasement de l'air Souterain dans une mine de charbon de terre ; sur les Vampyres, on corps morts accoutums a sucer le sang des vivans." The mode in which the learned author of this article, in the absence of all knowledge of the gases, endeavors to explain the causes of coal-pit explosions, is both ingenious and curious, but has now lost its interest in consequence of subsequent discoveries. His narrative of the ravages of vampirism in Servia is more to our purpose, and we accordingly translate it for the entertainment of our readers. However, the phenomenon may be explained, the facts stated relative to the ruddy healthy-looking condition of the supposed vampire corpses have been fully authenticated. " Our author says—

"In the, village of Kisolva, belonging to the district of Rahon, near Belgrade, a man died named Peter Plogowitz. Two months and a-half after his interment, it happened that, within the space of eight days, nine persons of different ages died, after about twenty-four hours illness, and declared that the said Plogowitz had appeared to them during sleep, and rested upon their bodies, squeezed their neck so hard as to leave them in a dying state. This character of vampirism was confirmed by the widow of the alleged vampire, who declared that her husband had come to her after his death to demand his shoes, upon which she quitted the village, for the purpose of establishing herself elsewhere.

Narratives of this sort are not new in that country, as there is a regular system of vampirism esta-

Continued on Page 2

blished, according to which the accused corpse must be examined, and certain forms be gone through for the purpose of putting an end to its murderous exploits. This, in the instance before us, was done in the presence of the provost of Belgrade, and of the chief priest of Gradisch. The former avers that he discovered in the disinterred carcass all the marks by which the natives, of that country distinguish vampires ; as, 1st, the body had no smell ; 2nd, it was entire, with the exception of the nose, which was a little thinned ; 3rd, the hair had commenced growing as well as the beard; 4th, new nails had been formed in place of the old ones, which had fallen off ; 5th, under the old skin, which was peeling off, and had become whitish, a new skin was growing up ; 6th, the countenance, the hands, the feet, and the whole body, were as fresh and healthy—looking as they could have been during life; 7th, it was remarked, with astonishment, that the mouth was filled with fresh liquid blood, which it was doubted that he had sucked from the bodies of those whom he had killed. Being then convicted of being a wicked vampire, a stake was quickly driven through his heart, from which abundance of blood issued, as well as from his mouth and ears, to say nothing of different effects which were manifested in other parts of the body. Finally, to curb his passion tor running about the country, the corpse was thrown upon at pile of wood, and reduced to ashes.

This fact is confirmed by many others, and particularly by another vampire of Kisolva, who took it into his head to demand food, and who, in effect, ate whatever was given to him. But he too, having committed many murders, was disinterred, when he appeared with his eyes open, his skin of a vermilion color, his respiration natural, but the body at the name time stiff and dead. Dead or not, however, from a dread of some trickery being practiced, he was again killed with blows of stones, and then burnt. But the most important circumstance connected with this second example happened in the year 1728, and related to the case of one Arnold Paule, who, having been tormented by a vampire, had the good fortune to save his life by eating a quantity of earth taken from the vampire's grave, and by rubbing himself with his blood. This, how- ever, did not prevent one of the most distressing consequences attributed to the attacks of vampires, namely, that those who have been sucked themselves regularly suck others in their turn—in other words, that those who, during life, have been passive vampires, become active vampires after death.

In fact, Arnold having been exhumed forty days after his burial, was found to have all the marks of an arch-vampire. Thus, when he was pierced with a stake, according to the ordinary method, the history states that he uttered a frightful yell, as if he had been alive. Several other persons who had died from the effects of vampirism were similarly proceeded against. In the year 1731, vampirism carried off seventeen individuals of different sexes and different ages, within the space of three months, and the chief complaint lay against a young noble man named Milo, who, nine weeks before his death had acted the hobgoblin, for the purpose of seducing the young females of the village. After many researches, it was agreed that all this mischief sprung from poor Arnold, who had been reduced to ashes five years before, as he had sucked not only the four persons whose bodies had been burnt along with his own, but he had also sucked beasts ; and the mischief was, that all who had eaten any portion of those vampire beasts became in course vampires themselves. Milo was one of these persons ; and on the occasion of his examination, the whole grave yard was scrutinized out of 40 bodies which had been interred within a certain period, 17 were found bearing the signs of vampirism. It need not be asked if a long time was spent in going through the established process. It remains only to be remarked, that the fact stated is attested by a great number of individuals of the strictest probity." As to the flat, that in the district mentioned corpses were found exhibiting the singular physical appearances above related, no doubt seems to be entertained. At least, on the testimony of so many and so unexceptionable witnesses, our French philosopher takes the fact as abundantly proved, and then he enters into an elaborate disquisition, in order to account for it upon the principles of natural science.

We need scarcely inform our readers that he very properly rejects the superstition founded upon it. To enter into the details of this argument would not be interesting to the majority of our readers, and we may therefore mention, that to the action of saltpetre he attributes the fluidity and freshness of the blood, and the ruddy color of the skin of the imaginary vampires. We translate the following detached passage, which will give some idea of his theory. Our author says—" From these discoveries" (alluding to certain facts in natural history, previously adduced), " we conclude that the fluidity of the blood in vampires is merely the effect of saltpetre, which had penetrated the pores of these bodies, and that the phenomena which the good priest of Gradisch took for nails and skins falling off and for renewed hairs and beards, were only a very subtle moss of saltpetre, which had been formed as a tissue over the different parts of the body, and which, in proportion as the dead bodies were roughly handled, became detached in form of a skin. The moss on the nails represented the old nails as having fallen from the fingers so much the more naturally, as it was by no means so firm as the skin, in consequence of the exceedingly minute pores of the nails.'

Here we close our extracts from this curious essay : but we have done enough to call the attention of those who have made physical science their study, to an exceedingly singular phenomenon in the history of the animal economy.

Citations

Article identifier http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article101736844

Page identifier http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page9710608

APA citation

THE VAMPIRE SUPERSTITION. (1851, March 8). The Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser (NSW : 1848 - 1859), pp. 1-2. Retrieved February 1, 2019, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article101736844

MLA citation

"THE VAMPIRE SUPERSTITION." The Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser (NSW : 1848 - 1859) 8 March 1851: 1-2. Web. 1 Feb 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article101736844>.

Harvard/Australian citation

1851 'THE VAMPIRE SUPERSTITION.', The Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser (NSW : 1848 - 1859), 8 March, pp. 1-2. , viewed 01 Feb 2019, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article101736844

#newspaper clipping#vampire#Arnold Paole#Vroucolocha#Vardoulacha#Vrykolakas#βρυκόλακας#priest of Gradisch#Kisolva#library#Milo#vampire Milo#Fluckinger#Peter Plogowitz#Peter Plogojowitz#Petar Blagojevich#Serbia#servia#Bibliotheque de Physique et d'Histoire Naturelle#Observations Physiques sur l'embrasement de l'air Souterain dans une mine de charbon de terre ; sur les Vampyres on corps morts accoutums a#The Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser#Sat 8 Mar 1851#Reprinted: From the Glasgow Herald#THE VAMPIRE SUPERSTITION#1851

0 notes

Text

Monsters of Halloween: Vampires

"But first, on earth as vampire sent, thy corpse shall from its tomb be rent: Then ghostly haunt thy native place, and suck the blood of all thy race;"

Lord Byron

So. Halloween is today. I will finish my posts discussing monsters and villains talking about my favorite creatures, the Vampires.

We first need to separate the vampire, the literary creation, and the vampire, an catch-all generic name to all creatures in folklore and legend that sought to drink the blood of the living.

Superstitions about blood sucking creatures always existed, at thought, they often manifested in very different ways depending on the culture. Don't expect the dark aristocratic type here.

In Germany, you had the Alp, an incubus-like spirit, a mischievous elf creature that drinks blood from the nipples of women, men and young children.

In Norse Mythology you had the Draugr, reanimated corpses that lived to protect their treasure, haunt the living, and taking bloody revenge on those who wronged them, devouring their flesh or drinking their blood.

In Bolivia you had the Abchanchu, a shapeshifter that assumes the form of a elderly traveler to drink the blood of anyone who comes to help him.

In a Ireland you had the Abhartach, a tyrant dwarf king, that even after been killed, refused to stay in his grave, and continued to haunt the living.

But it were the beliefs of the people of southern Europe that would plant the seeds of the modern day vampire.

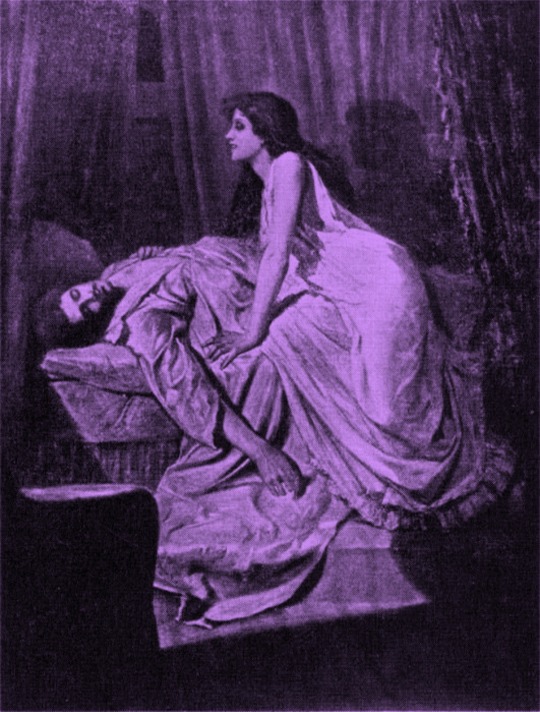

To them the Vampire were the dead. The living dead. The dead would come back to steal the blood, and with it, the life force of the living.

This was the Vampire Craze of 1720's to 1730's. The belief on the Vampire became so strong, that in some areas people were killed suspect of been one.

Serbia under the Habsburg Monarchy, would see exhumations of the bodies of Arnold Paole and Petar Blagojevich, suspected of had been vampires .

People looted graves. They cut the head of the corpses, pierced wood stakes through their chests, cut the legs and placed them in a crossed position. All of that to stop the dead from leaving their graves to haunt and hunt the living.

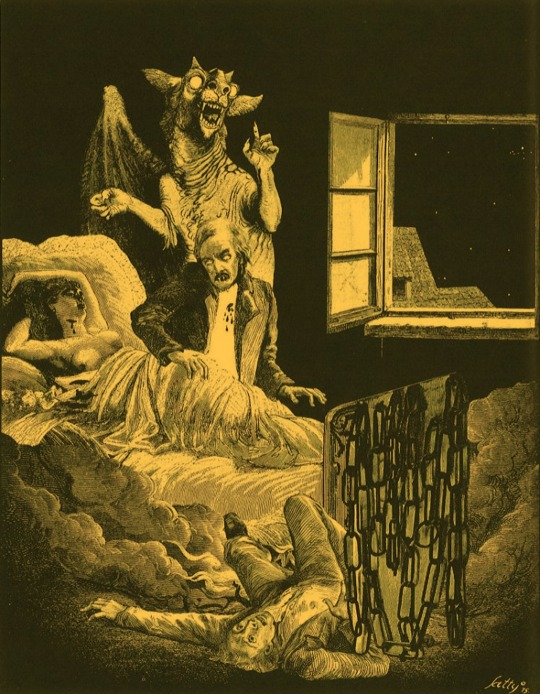

Around that same time, many of their traditions were recorded for the first time and were made know and brought to the West. These creatures created a huge impact on western literature, with animal-like behavior concealed by a human exterior, and obvious sexual connotations serving as huge sources of inspiration. (Yeah, the Vampire always had sexual tones. In the Balkans, for example, it was believed that male vampires had a great desire for human women)

In poem "The Vampire" (1748) by german Heinrich August Ossenfelder, the main character threatens to invade a girl's house in the middle of the night, suck her blood and then give her his deadly kiss, proving that his teachings were better than her mother's Christianity.

Several poems also speak of the dead returning to take their living significant others to the grave with them. Lenore is one example, although in that case it wasn't her lover, but Death itself in disguise. Other example is in "The Bride of Corinth" by Gothe, where we get this:

"From my grave to wander I am forced

Still to seek the God's long sever'd link,

Still to love the bridegroom I have lost,

And the lifeblood of his heart to drink."

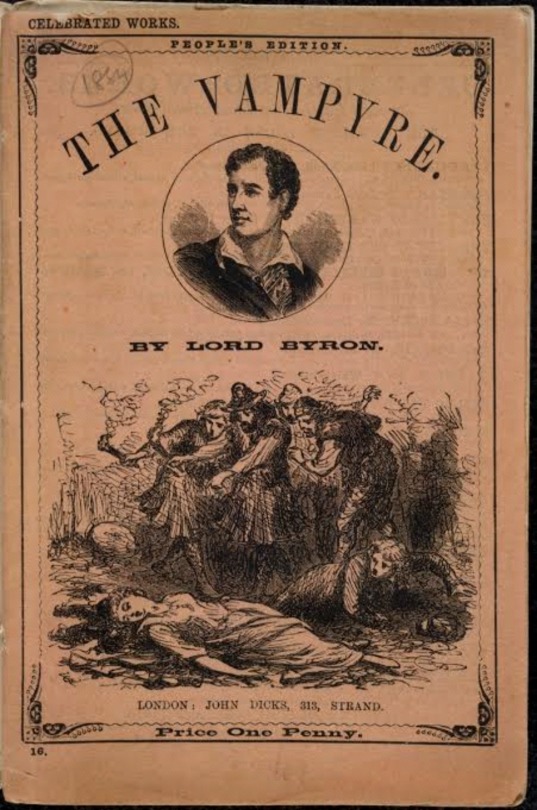

In the same bet between writers Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley, Lord Byron and John William Polidori that gave us Frankenstein, also gave us "The Vampyre" (1816). In there we meet Lord Ruthven, an alluring vampire hidding in London high society, seducing women, draining their blood and vanishing into the night.

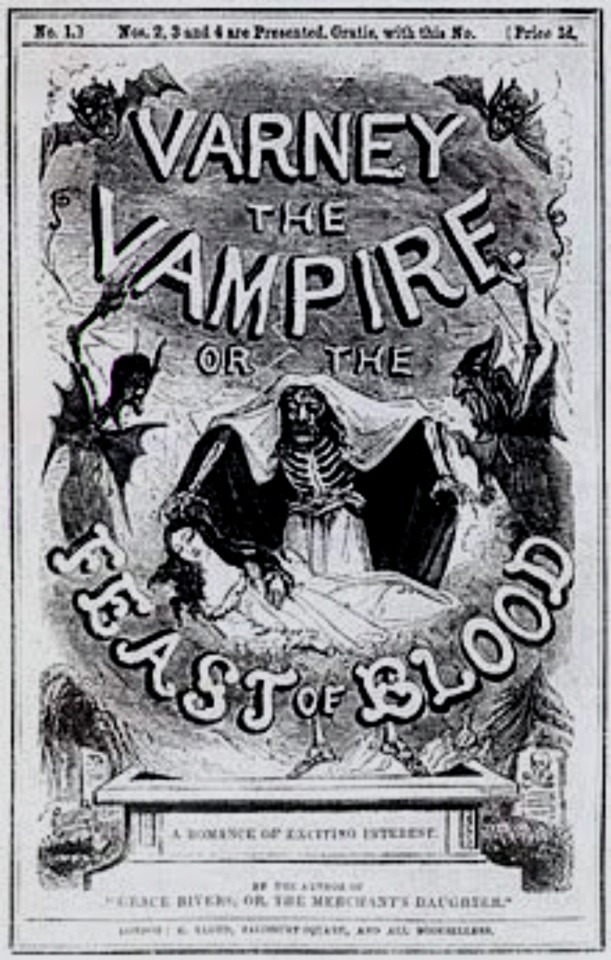

During the Victorian times, we had Varney the Vampire (1845–1847), a Penny Dreadful, a cheap serialized story of the misadventures of Sir Francis Varney, a vampire fixated on haunting the Bannerworths, a formerly wealthy family driven to ruin by their recently deceased father.

Many vampire tropes started with these stories, like vampire fangs and two wounds in the neck, invasions through a window to attack a sleeping maiden, hypnotic powers, superhuman strength.

But there was a book that forever would cement the vampire image on public perception. Dracula by Bram Stoker (1897)

Dracula is to the Vampire Genre what the New Testament is to Christianity. He is the one in which all vampires in the 20th and 21th century are molded after. The dark nobleman that would forever put Transylvania on the map and establish vampire lore, the vampire that turns into bats, is weak in sunlight, preys on women and is hunted by Van Helsing.

So, what makes a Vampire so interesting? Easy, a Vampire is a beast pretending to be human. They are savage creatures that want to kill and breed (interpret this as you want), but they must pass for human to survive and haunt innocent victims. They are the window for our innermost desires, our most brutish behavior. They bend gender and societal rules and Taboos. They are the most animalistic and visceral version of ourselves come to light, and their role is to allows a sense of catharsis and to shows us what happens when all our inner demons are free to play through the night.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Vampire of Kisiljevo

All life comes to an end eventually, or so the villagers of Kisiljevo Serbia assumed in 1725. Petar Blagojevich was put to rest in an average grave, leaving behind his wife and son in the land of the living. All were left to mourn, but not left for long.

That evening he returned to his wives home, warm and alive as if his heart never ceased to beat. Then he took his first victim. Local villager was strangled to death, his body drained of blood. This alone would not quench his hunger.

For eight days the village served as his hunting grounds, not even sparing his own son. On the ninth day the villager’s had enough, and turned to the local priest for his holy aid.

All were shocked at what they saw. Inside the coffin Petar lay, flesh pink with no sign of decomposition. Blood stained his lips, dripping down and pooling in the bottom of the coffin.

His heart was removed and staked, body burnt to ashes. Only then was the village released from Petar’s grasp, with only nightmares left to haunt the people of Kisiljevo.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lore Episode 30: Deep and Twisted Roots (Transcript) - 21st March 2016

tw: blood

Disclaimer: This transcript is entirely non-profit and fan-made. All credit for this content goes to Aaron Mahnke, creator of Lore podcast. It is by a fan, for fans, and meant to make the content of the podcast more accessible to all. Also, there may be mistakes, despite rigorous re-reading on my part. Feel free to point them out, but please be nice!

In the early 1990s, two boys were playing on a gravel hill near an old, abandoned mine outside of Griswold, Connecticut. Kids do the oddest things to stave off boredom, so playing on a hill covered in small rocks doesn’t really surprise me, and my guess is they were having a blast – that is, until one of them dislodged two larger rocks. But when the rocks tumbled free and rolled down the hill, both boys noticed something odd about them. They were nearly identical in shape, and that shape was eerily familiar. They headed down the hill one last time to take a closer look, and that’s when they realised what they’d found: skulls. At first, the local police were brought in to investigate the possibility of an unknown serial killer. That many bodies all in one place was never a good sign, but it became obvious very quickly that the real experts they needed were, in fact, archaeologists – and they were right. In the end, 29 graves were discovered in what turned out to be the remnants of a forgotten cemetery. Time and the elements had slowly eroded away the graveyard, and the contents had been swallowed by the gravel. Many skeletons were still in their caskets, though, and it was inside one of them, marked with brass tacks to form the initials of the occupant, that something unusual was discovered. Long ago, it seems, someone had opened this casket shortly after burial and had then made changes to the body. Specifically, they’d removed both femurs, the bones of the thigh, and placed them across the chest. Then, moving some of the ribs and the breast bone out of the way, they placed the skull above them. It was a real-life skull and crossbones, and its presence hinted at something darker. The skeleton, you see, wasn’t just the remains of an ordinary early settler of the area. This man was different, and the people who buried him knew it. According to them, he had been a vampire. I’m Aaron Mahnke, and this is Lore.

While it might be a surprise to some people, graves like the one in Griswold are actually quite common. Today, we live in the Bram Stoker era of vampires, so our expectations and imagery are highly influenced by his novel and the world it evokes – Victorian gentlemen in dark cloaks, mysterious castles, sharp fangs protruding over blood red lips. But the white face and red lips started life as nothing more than stage make-up, an artefact from a 1924 theatrical production of the novel called Count Dracula. Another feature we associate with Dracula, his high-collar, also started there. With wires attached to the points of the collar, the actor playing Dracula could turn his back on the audience and drop through a trap door, leaving an empty cape behind to fall on the floor moments later. The true myth of the vampire, though, is far older than Stoker. It’s an ancient tree with deep and twisted roots. As hard as it is for popular culture to fathom, the legend of the vampire and the people who hunt it actually predate Dracula by centuries. Just a little further into the past than Bram Stoker, in the cradle of what would one day become the United States, the people of New England were identifying vampire activity in their own towns and villages and then assembling teams of people to deal with what they perceived as a threat. It turns out that Griswold was one of those communities. According to the archaeologists who studied the 29 graves, a vast majority of them were contemporary to the vampire’s burial, and most of those showed signs of an illness. Tuberculosis is the most likely guess, which goes a long way toward explaining why the people did what they did. The folklore was clear – the first to die from an illness was usually the cause of the outbreak that followed. Patient 0 might be in the grave, sure, but they were still at work, slowly draining the lives of the others.

Because of this belief, bodies all across the north-east were routinely exhumed and destroyed in one way or another. In many ways, it was as if the old superstitions were clawing their way out of the depths of the past to haunt the living. The details of another case from Stafford, Connecticut in the late 1870s illustrate the ritual perfectly. After a family there lost five of their six daughters to illness, the first to have passed away was dug up and examined. This is what was recorded about the event: “Exhumation has revealed a heart and lungs,” they wrote, “still fresh and living, encased in rotten and slimy integuments, and in which, after burning these portions of the defunct, a living relative, else doomed and hastening to the grave, has suddenly and miraculously recovered”. This sort of macabre community event happened frequently in places like Connecticut, Vermont, New York, New Hampshire and even Ontario, Canada, and long-time listeners of Lore will of course remember the subject of the very first episode, and how the family of Mercy Brown in Rhode Island exhumed her body after others died, doing a very similar thing. Mercy Brown wasn’t the first American vampire, though. As far as we can tell, that honour goes to the wife of Isaac Burton of Manchester, Vermont, all the way back in 1793, and for as chilling and dark the exhumation of Mercy Brown might have been, the Burton incident puts that story to shame.

Captain Isaac Burton married Rachel Harris in 1789, but their marriage was brief. Within months of the wedding, Rachel took sick with Tuberculosis, what was then called “consumption” because of the way the disease seemed to waste the person away, as if they were being consumed by something unseen. Rachel soon died, leaving her husband a young widower, but that didn’t last long. Burton married again in April of 1791, this time to a woman named Hulda Powell. But again, within just two years of their marriage, Burton’s bride became ill. Friends and neighbours started to whisper and as people are prone to do, they began to try and draw conclusions. Unanswered questions bother us, so we tend to look for reasons, and the people of Manchester thought they knew why Hulda was sick. Although Isaac’s wife, Rachel, had been dead for nearly three years, the people of Manchester suggested that she was the cause. Clearly, from her new home in the graveyard, she was draining the life from her husband’s new bride. With Burton’s permission, the town prepared to exhume her and end the curse. The town blacksmith brought a portable forge to the gravesite and nearly 1000 people gathered there to watch the grim ceremony unfold. Rachel’s liver, heart and lungs were all removed from her corpse and then reduced to ashes. Sadly, though, Hulda Burton never recovered, and she died a few months later. This ancient ritual, as far as the people of Manchester, Vermont were concerned, had somehow failed them. They did what they had been taught to do, as unpleasant as it must have been, and yet it hadn’t worked – which was odd, because that hadn’t always been the case.

A lot of what we think we know about the roots of the vampire legend is thanks to Dracula, the novel by Bram Stoker. Most of us know the basics – Stoker built a mythology around a historical figure from the fifth century named Vlad III. Vlad was from the kingdom of Wallachia, now part of modern-day Romania. Vlad had two titles: Vlad Tepes, which meant “The Impaler”, referred to his brutal military tactics in defence of his country; the other, Vlad Dracul, or “The Dragon”, referred to his membership in the Order of the Dragon, a military order founded to protect Christian Europe from the armies of the invading Ottoman Empire. But Bram Stoker never travelled to Romania. The castle that he describes as the home of Dracula, a real-life fortress known as Bran Castle, was just an image he found in a book that he felt captured the mood he was aiming for. Bran Castle, as far as historians can tell, has no connection to Vlad III whatsoever. The notion of a vampire, or at least of an undead creature that feeds on the living, does have roots in the area, though. Stoker was close, but he missed the mark by a little more than 300 miles. The real roots of the legend, according to most historians, can be found in modern-day Serbia. Serbia of today sits at the south-western corner of Romania, just south of Hungary. Between 1718 and 1739, the country passed briefly from the hands of the Ottoman Empire to the control of the Austrians. Because of its place between these two empires, the land was devastated by war and destruction and people were frequently moved around in service to the military, and as is often the case, when people cross borders, so do ideas.

Petar Blagojevich was a Serbian peasant in the village of Kisiljevo in the early 1700s. Not much is known about his life, but we do know that he was married and had at least one son, and in 1725, through causes unknown, Petar died at the age of 62. In most stories, that’s the end, but not here. You probably knew that, though, didn’t you? In the eight days that followed Petar’s death, other people in the village began to pass away. Nine of them, in fact, and all of them made startling claims on their death beds, details that seemed impossible to prove but were somehow the same in each case. Each person was adamant that Petar Blagojevich, their recently deceased neighbour, had come to them in the night and attacked them. Petar’s widow even made the startling claim that her dead husband had actually walked into her home and asked for, of all things, his shoes. She believed so strongly in this visit that she moved to another village to avoid future visits. The rest of the people of Kisiljevo took notice. Something had to be done, and that would begin with digging up Petar’s corpse. Inside the coffin, they found Petar’s body to be remarkably preserved. Some noticed how the man’s nails and hair had grown. Others remarked on the condition of his skin, which was flush and bright, not pale. It wasn’t natural, they said, and something had to be done. They turned to a man named Frombald, a local representative of the Austrian government, and together with the help of a priest he examined the body for himself. In his written report, he confirmed the earlier findings and added his observation that fresh blood could be seen inside Petar’s mouth. Frombald describes how the people of the village were overcome with fear and outrage, and how they proceeded to drive a wooden stake through the corpse’s heart. Then, still afraid of what the creature might be able to do to them in the future, the people burnt the body. Frombald’s report details all of it, but he also makes the disclaimer that he wasn’t responsible for the villager’s actions. He said that it was fear that drove them to it, nothing more. Petar’s story was powerful, and it created a panic that quickly spread throughout the region. It was the first event of its kind in history to be recorded in official government documents, but that report was still missing an official cause. Without it, the stories might have died where they started. But then, just a year later, something happened, and the legend had never been the same.

Arnold Paole was a former soldier, one of the many men transplanted by the Austrian government in an effort to defend and police their newly acquired territory. No one is sure where he was born, but his final years were spent in a Serbian village along the great Morava river, near Paraćin. In his post-war life, Arnold became a farmer, and he frequently told stories from days gone by. In one such story, Arnold claimed that he had been attacked by a vampire years before while living in Kosovo. He survived, but the injury continued to plague him until he finally took action. He said that he cured himself by eating soil from the grave of the suspected vampire, and then, after digging up the vampire’s body, he collected some of its blood and smeared it on himself. And that was it – according to Arnold and the folklore that drove him to it, he was cured. When he died in a farming accident in 1726, though, people began to wonder, because within a month of his death at least four other people in town complained that Arnold had visited them in the night and attacked them. When those people died, the villagers began to whisper in fear. They remembered Arnold’s stories – stories of being attacked by a vampire, of taking on the disease himself, stories of his own attempt to cure himself. But what if it hadn’t worked? Out of suspicion and doubt, they decided to exhume his body and examine it. Here, for what was most likely the first time in recorded history, the story of the vampire was taking on the form of a communicable disease, transmitted from person to person through biting. This might seem obvious to us now, but we’ve all grown up with the legend fully formed. To the people of this small, Serbian village, though, this was something new and horrific. What they found seemed like conclusive evidence, too: fresh skin, new nails, longer hair and beard. Arnold even had blood in his mouth. Putting ourselves in their context, it’s easy to see how they might have been chilled with fear – so they drove a stake through his heart. One witness claimed that, as the stake pierced the corpse’s chest, the body groaned and bled. Unsure of what else to do, they burned the body, and then they did the same to the four who had died after claiming Arnold attacked them. They covered all their bases, so to speak, and then walked away.

Five years later, though, another outbreak spread through the village. We know this because so many people died that the Austrian government sent a team of military physicians from Belgrade to investigate the situation. These men, led by two officials named Glaser and Flückinger, were special, though, because they were trained in communicable diseases, which was a good thing. By January 7th of 1731, just eight weeks after the beginning of the outbreak, 17 people had died. At first, Glaser had looked for signs of a contagious disease, but came up empty-handed. He noted signs of mild malnutrition, but there was nothing deadly that could be found. The clock was ticking, though. The villagers were living in such fear that they had been gathering together into large groups each night, taking turns keeping watch for the creatures they believed were responsible. They even threatened to pack up and move elsewhere. Something needed to be done, and quickly. Thankfully, there were suspects. The first was a young woman named Stana, a recent newcomer to the village who had died during childbirth early on in the outbreak. It seemed to have been a sickness that took her life, but there were other clues. Stana had confessed to smearing vampire blood on herself years before as protection, but that, the villagers claimed, had backfired, and most likely turned her into one instead. The other suspect was an older woman named Milica. She was also from another part of Serbia, and had arrived shortly after Arnold’s death. Like so many others, she had a history. Neighbours claimed that she was a good woman who never did anything intentionally wicked, but she had told them once of how she’d eaten meat from a sheep killed by a vampire, and that seemed like evidence enough to push the investigation to go deeper… literally.

With permission from Belgrade, Glaser and the villagers exhumed all of the recently deceased, opening their coffins for a full examination, and while logic and science should have prevailed in a situation like that, what they found only deepened their belief in the supernatural. Of the 17 bodies, only five appeared normal, in that they had begun to decay in a manner that should be expected. These were reburied and considered safe, but it was the other 12 that alarmed the villagers and the government men alike, because these bodies were still fresh. In the report filed in Belgrade in January of 1732, signed by all five of the government physicians who witnessed the exhumations, these 12 bodies were completely untouched by decay, organs still held fresh blood, their skin was healthy and firm, and new nails and hair had grown since burial. These are all normal occurrences as we understand decomposition today, but three centuries ago it was less about science and more about superstition. This didn’t seem normal to them, and so when the physician wrote their report, they used a term that, until that very moment, had never appeared in any historical account of such a case. They described the bodies as “vampiric”. In the face of unanswered questions, the only conclusion they could commit to was that each of the 12 bodies had been found in a “vampiric” condition. With that, the villagers did what their tradition demanded: they removed the heads from each corpse, gathered all the remains into a pile, and then burned the whole thing. The threat to the village was finally dead and gone, but it was too late. Something new had been born, something more powerful than a monster, something that lives centuries and spreads like fire: a legend.

[21:20]

Many aspects of folklore haven’t faired too well under the critical eye of science. Today, we have a much deeper understanding of how illness and disease really works, and while experts are still careful to explain that every corpse decomposes in a slightly unique way, we have a better grasp of the full picture now than any previous time in history. Answers, when we can find them, come as a relief. It’s safe to say that we don’t have to fear a vampiric infection when the people around us get sick today, but there were still people at the centre of these ancient stories, normal folk like you and me, who simply wanted to do what was right. We might do it differently today, but it’s hard to fault them for trying. Answers don’t kill every myth, though. Vampire stories, like their immortal subjects, have simply refused to die. In fact, they can still be found, if you know where to look for them. In the small, Romanian village of Marotinu de Sus, near the south-western corner that borders Bulgaria and Serbia, authorities were called in to investigate an illegal exhumation, but this wasn’t 1704 or even 1804. This happened just a decade ago. Petre Toma had been the clan leader there in the village, but after a lifetime of illness and hard drinking, his accidental death in the field almost came as a relief to his family and friends. That’s how they put it, at least. So, when he was buried in December of 2003, the community moved on. But individuals from Petre’s family began to get sick. First it was his niece, Mirela Marinescu. She complained that her uncle had attacked her in her dreams. Her husband made the same claim, and both offered their illness as proof. Even their infant child was not well. Thankfully, the elders of the village immediately knew why. In response to her story, six men gathered together one evening in early 2004. They entered the local graveyard close to midnight, and then travelled to the burial site of Petra Toma. Using hammers and chisels, they broke through the stone slab that covered the grave and then moved the pieces aside. They drank as they worked. Can you really blame them? They were opening the grave of a recently deceased member of their community, but I think it was more than that. In their minds, they were putting their lives in danger, because there, inside the grave and just uncovered, lay the stuff of nightmares – a vampire. What these men did next will sound strangely familiar, but to them it was simply the continuation of centuries of tradition. They cut open the body using a knife and a saw, they pried the ribs apart with a pitchfork, and then cut out the heart. According to one of the men who was there, when the heart was removed, they found it full of fresh blood. Proof, to them at least, that Petre had been feeding on the village. When they pulled it free, the witness said that the body audibly sighed, and then went limp. It’s hard to prove something that six incredibly superstitious men – men who had been drinking all night, mind you – claimed they witnessed in a dark cemetery, but to them it was pure, unaltered truth. They then used the pitchfork to carry the heart out of the cemetery and across the road to a field, where they set it on fire. Once it was burnt completely, they collected the ashes and funnelled them into a bottle of water. They offered this tonic to the sick family, who willingly drank it. It was, after all, what they had been taught to do, and amazingly, everyone recovered. No one died of whatever illness they were suffering from, and no one reported visits from Petre Toma after that. In their mind, the nightmare was over. These men had saved their lives. Maybe something evil and contagious has survived for centuries after all, spreading across borders and oceans. It’s certainly left a trail of horrific events in its wake, and its influenced countless tales and superstitions, all of which seem to point to a real-life cause. But far from being unique to Serbia or Romania, this thing is global. And as if that weren’t enough, this horrible, ageless monster is, and always had been, right inside each of us. Like a vampiric curse, we carry it in our blood, but its probably not what you’d expect. It’s fear.

[Closing statements]

#lore podcast#aaron mahnke#podcast transcripts#vampires#folklore#serbia#romania#connecticut#transcripts#30

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Petar Blagojevich part 2 Together with the Veliko Gradište priest, he viewed the already exhumed body and was astonished to find that the characteristics associated with vampires in local belief were indeed present. The body was undecomposed, the hair and beard were grown, there were “new skin and nails” (while the old ones had peeled away), and blood could be seen in the mouth. After that, the people, who “grew more outraged than distressed,” proceeded to stake the body through the heart, which caused a great amount of “completely fresh” blood to flow through the ears and mouth of the corpse. Finally, the body was burned. Frombald concludes his report on the case with the request that, in case these actions were found to be wrong, he should not be blamed for them, as the villagers were “beside themselves with fear.” The authorities apparently did not consider it necessary to take any measures regarding the incident. The report on this event was among the first documented testimonies about vampire beliefs in Eastern Europe. It was published by Wienerisches Diarium, a Viennese newspaper, today known as Die Wiener Zeitung. Along with the report of the very similar Arnold Paole case of 1726-1732, it was widely translated West and North, contributing to the vampire craze of the eighteenth century in Germany, France and England. The strange phenomena or appearances that the Austrian officials witnessed are now known to accompany the natural process of the decomposition of the body. Scholars have noted the influence of Blagojevich’s case upon the development of the image of the modern vampire in Western popular culture. #destroytheday (Throwback post from May 30th, 2017) https://www.instagram.com/p/B-ANnKcBVLc/?igshid=aryyaertanjx

0 notes

Photo

~ Serbian vampires - PART 2 ~

Peter Plogojowitz ( in serbian: Petar Blagojević ) was a Serbian peasant who was believed to have become a vampire after his death and to have killed nine of his fellow villagers. The case was one of the earliest, most sensational and most well documented cases of vampire hysteria. It was described in the report of Imperial Provisor Frombald, an official of the Austrian administration, who witnessed the staking of Blagojević. Blagojević died in 1725, and his death was followed by a spate of other sudden deaths. Within eight days, nine persons died. On their death-beds, the victims claimed to have been throttled by Blagojević at night.

The villagers decided to disinter the body and examine it for signs of vampirism, such as growing hair, beard and nails, and the absence of decomposition. And the body indeed was undecomposed, the hair and beard were grown, there were "new skin and nails" (while the old ones had peeled away), and blood could be seen in the mouth. After that, the people, who "grew more outraged than distressed", proceeded to stake the body through the heart, which caused a great amount of "completely fresh" blood to flow through the ears and mouth of the corpse. Finally, the body was burned.

0 notes

Photo

Petar Blagojevich (died 1725) was a Serbian peasant who was believed to have become a vampire after his death and to have killed nine of his fellow villagers. The case was one of the earliest, most sensational and most well documented cases of vampire hysteria. It was described in the report of Imperial Provisor Frombald, an official of the Austrian administration, who witnessed the staking of Blagojevich. Petar Blagojevich lived in a village named Kisilova (possibly the modern-day town of Kisiljevo), in Serbia. Blagojevich died in 1725, and his death was followed by a spate of other sudden deaths (after very short maladies, reportedly of about 24 hours each). Within eight days, nine persons perished. On their death-beds, the victims allegedly claimed to have been throttled by Blagojevich at night. Furthermore, Blagojevich’s wife stated that he had visited her and asked her for his opanci (shoes). She then moved to another village for safety reasons. In other legends, it is said that Blagojevich came back to his house demanding food from his son and, when the son refused, Blagojevich brutally murdered him, probably via biting and drinking his blood. The villagers decided to disinter the body and examine it for signs of vampirism, such as growing hair, beard and nails, and the absence of decomposition. The inhabitants of Kisilova demanded that Kameralprovisor Frombald, along with the local priest, should be present at the procedure as a representative of the administration. Frombald tried to convince them that permission from the Austrian authorities in Belgrade should be sought first. The locals declined because they feared that by the time the permission came, the whole community could be exterminated by the vampire, which they claimed had already happened “in Turkish times” (i.e. when the village was still in the Ottoman-controlled part of Serbia). They demanded that Frombald himself should immediately permit the procedure or else they would abandon the village to save their lives. Frombald was forced to consent. #destroytheday https://www.instagram.com/p/B-ANjSnhLv3/?igshid=12rev5al1u19u

0 notes

Text

Episode 30: Deep and Twisted Roots (Further Reading)

This is in no way an official source list used by Aaron Mahnke, but is more meant to be a starting point meant for anyone wanting to dig further into any particular topic.

Griswold Vampires:

[Wikipedia] Jewett City vampires [Article] Jewett City Vampires [Article] The Jewett City Vampires, Griswold [Article] The Great New England Vampire Panic [Article] The Vampire Graves of Jewett City: The Legend of Connecticut’s Undead, Blood-Sucking Vampire Family

Isaac Burton’s wives:

[Article] The Vampire of Manchester, Vermont [Article] Rachel Burton (nee Harris), Vampire of Manchester [Article] Weiland Ross: The vampire cure — Myth or true story in Bennington County

Vlad the Imapler:

Further reading here

Petar Blagojevich:

[Wikipedia] Petar Blagojević [Video] Petar Blagojević: The Murderous Vampire (Occult History Explained) [Article] Serbia: The Birthplace of Vampires [Article] Vampire tourism: Kisiljevo in Serbia is where vampire Petar Blagojevich ‘lived’

Arnold Paole:

[Wikipedia] Arnold Paole [Article] The Story of Arnold Paole [Article] Arnold Paole [Article] Arnold Paole and the Flückinger Report: Does This Historic Report Prove Vampires Exist? [Article] The Legendary Arnold Paole

Petra Toma:

[News report] A village still in thrall to Dracula [Wikipedia] Strigoi [News report] The real vampire slayers [Blog post] The case of Petre Toma [Article] From the crypt, the greatest Halloween story ever told. And it was true [Article] Romanian villagers decry police investigation into vampire slaying

0 notes

Photo

Arnold Paole (Arnont Paule in the original documents; died c. 1726) was a Serbian hajduk who was believed to have become a vampire after his death, initiating an epidemic of supposed vampirism that killed at least 16 people in his native village of Meduegna, located at the West Morava river in Trstenik, Serbia. Paole's case, similar to that of Petar Blagojevich, became famous because of the direct involvement of the Austrian authorities and the documentation by Austrian physicians and officers, who confirmed the reality of vampires. Their report of the case was distributed in Western Europe and contributed to the spread of vampire belief among educated Europeans. Knowledge of the case is based mostly on the reports of two Austrian military doctors, Glaser and Flückinger, who were successively sent to investigate the case. According to the account of the Medveđa locals, Arnold Paole had moved to the village from the Turkish-controlled part of Serbia. He reportedly often mentioned that he had been plagued by a vampire at a location named Gossowa (perhaps Kosovo), but that he had cured himself by eating soil from the vampire's grave and smearing himself with his blood. About 1725, he broke his neck in a fall from a haywagon. Within 20 or 30 days after Paole's death, four persons complained that they had been plagued by him. These people all died shortly thereafter. Ten days later, and forty days after Arnold's death, the villagers, advised by their hadnack (a military/administrative title) who had witnessed such events before, opened Paole's grave. They saw that the corpse was undecomposed with all the indications of an arch-vampire. His veins were replete with fluid-blood "and that fresh blood had flowed from his eyes, nose, mouth, and ears; that the shirt, the covering, and the coffin were completely bloody; that the old nails on his hands and feet, along with the skin, had fallen off, and that new ones had grown." Further, "his body was red, his hair, nails and beard had all grown again. #destroytheday

0 notes

Photo

Petar Blagojevich part 2 Together with the Veliko Gradište priest, he viewed the already exhumed body and was astonished to find that the characteristics associated with vampires in local belief were indeed present. The body was undecomposed, the hair and beard were grown, there were "new skin and nails" (while the old ones had peeled away), and blood could be seen in the mouth. After that, the people, who "grew more outraged than distressed," proceeded to stake the body through the heart, which caused a great amount of "completely fresh" blood to flow through the ears and mouth of the corpse. Finally, the body was burned. Frombald concludes his report on the case with the request that, in case these actions were found to be wrong, he should not be blamed for them, as the villagers were "beside themselves with fear." The authorities apparently did not consider it necessary to take any measures regarding the incident. The report on this event was among the first documented testimonies about vampire beliefs in Eastern Europe. It was published by Wienerisches Diarium, a Viennese newspaper, today known as Die Wiener Zeitung. Along with the report of the very similar Arnold Paole case of 1726-1732, it was widely translated West and North, contributing to the vampire craze of the eighteenth century in Germany, France and England. The strange phenomena or appearances that the Austrian officials witnessed are now known to accompany the natural process of the decomposition of the body. Scholars have noted the influence of Blagojevich's case upon the development of the image of the modern vampire in Western popular culture. #destroytheday

0 notes

Photo

Petar Blagojevich (died 1725) was a Serbian peasant who was believed to have become a vampire after his death and to have killed nine of his fellow villagers. The case was one of the earliest, most sensational and most well documented cases of vampire hysteria. It was described in the report of Imperial Provisor Frombald, an official of the Austrian administration, who witnessed the staking of Blagojevich. Petar Blagojevich lived in a village named Kisilova (possibly the modern-day town of Kisiljevo), in Serbia. Blagojevich died in 1725, and his death was followed by a spate of other sudden deaths (after very short maladies, reportedly of about 24 hours each). Within eight days, nine persons perished. On their death-beds, the victims allegedly claimed to have been throttled by Blagojevich at night. Furthermore, Blagojevich's wife stated that he had visited her and asked her for his opanci (shoes). She then moved to another village for safety reasons. In other legends, it is said that Blagojevich came back to his house demanding food from his son and, when the son refused, Blagojevich brutally murdered him, probably via biting and drinking his blood. The villagers decided to disinter the body and examine it for signs of vampirism, such as growing hair, beard and nails, and the absence of decomposition. The inhabitants of Kisilova demanded that Kameralprovisor Frombald, along with the local priest, should be present at the procedure as a representative of the administration. Frombald tried to convince them that permission from the Austrian authorities in Belgrade should be sought first. The locals declined because they feared that by the time the permission came, the whole community could be exterminated by the vampire, which they claimed had already happened "in Turkish times" (i.e. when the village was still in the Ottoman-controlled part of Serbia). They demanded that Frombald himself should immediately permit the procedure or else they would abandon the village to save their lives. Frombald was forced to consent. #destroytheday

0 notes

Link

1 note

·

View note