#Patanjali Yoga Sutras

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Liberation and Independence, The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

#patanjali#yoga sutras of patanjali#yogasutras of patanjali#yoga sutra#patanjali yoga sutras#yoga sutras#patanjali yoga sutra#the yoga sutras of patanjali#yogas sutras de patanjali#ashtanga as a means of liberation#les yoga sutra de patanjali#les yoga sutras de patanjali pdf#yoga sutra patanjali français#yoga sutra patanjali#sutras#yoga sutra patanjali pdf#patanjalis yoga sutras#sutra de patanjali#patanjali sutras#what is the purpose of yoga sutras#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Align with Patanjali Yoga Sutras | Igor Kufayev’s Path to Authentic Living

Immerse yourself in Igor Kufayev’s transformational exploration of the Patanjali Yoga Sutras, designed for seekers ready to align with universal values and unlock their true potential. This online course redefines spirituality by shedding light on foundational principles and myths, fostering an authentic life of wellbeing and fulfillment through deep insights and meditative practice. Perfect for yoga enthusiasts, teachers, and facilitators.

0 notes

Text

The Elements of the Mind: A Pathway to Self-Realization

Discover the profound power of the mind and its connection to self-realization through the exploration of the four elements: Citta, Ahamakāra, Mānas, and Buddhi. Gain insights from the wisdom of Patanjali Yoga sutras and scientific research to enhance min

The mind, often considered a product of brain activity, holds incredible power beyond its physical manifestation. In Indian culture, the mind is viewed as a combination of four elements: mānas, ahamakāra, citta, and buddhi. Understanding these aspects of the mind is crucial for suspending and letting go of our thoughts, emotions, and actions, ultimately leading to a positive and fulfilling life.…

View On WordPress

#Acupuncture#Ahamakāra#annabackacupuncture#Buddhi#Citta#emotions#inner peace#malibu#mind control#Mānas#palos verdes#Patanjali Yoga sutras#self-awareness#self-realization

0 notes

Text

A Short Introduction to the Yoga Sutras

The Yoga Sutras are generally considered a foundational text of the yoga tradition. In this article we examine the context and background of the text, briefly explore its structure and content, and I also offer some reflections on the text’s relevance in modern times.

Note: I have decided not to use diacritics in this article. Diacritics are those little lines and dots above and below letters that tell you how to pronounce Sanskrit words. Normally I use diacritics in my writing, as they are essential for pronouncing Sanskrit correctly. However as this article is meant for non-scholars I have decided it would be better to try and write the Sanskrit words in a way that will make them easy to read and pronounce, so as not to put anybody off!

History & Context

Most scholars these days date the Yoga Sutras to somewhere between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE, with Philipp Maas placing it in the early 5th century.

The text is attributed to a sage named Patanjali. Biographically, we know next to nothing about Patanjali. The name is a compound word formed from the Sanskrit words pata (falling, flying) and anjali (the gesture of joining the hands together in reverence).

Yoga had already been around in some form or another for many centuries by this point. Therefore, Patanjali did not ‘invent’ Yoga. Nevertheless, this is the earliest comprehensive and systematic text on the subject that has survived.

Yoga was just one darshana or school out of many in ancient India. In terms of philosophy, it shares many similarities with the Samkhya school. But whereas Samkhya tends to emphasise the use of reason and knowledge to gain liberation, Yoga emphasises practical and experiential methods.

Philosophically, both the Samkhya and Yoga schools teach a form of dualism. This is a dualism between purusha (our true Self) and prakriti (everything else, including the body and mind) and the whole point of Samkhya and Yoga in a nutshell is to guide us towards the realisation of purusha, that is, our true Self. This is true liberation or moksha in Yoga.

Most of the ancient darshanas had their own sutra text. Sutra texts are known for their brevity. Basically, sutra texts are where the most essential teachings of a school are distilled into as few words as possible. Knowledge systems were handed down orally in ancient India and thus source material was kept minimal with a view to facilitating memorisation.

Other authors would then come along and write longer commentaries on these sutra texts. The Yoga Sutras have a rich commentarial tradition spanning many centuries. The first and most well known is the bhasya commentary by a certain Vyasa. Vyasa actually means something like ‘compiler’ or ‘editor’ so that probably wasn’t his actual name!

Some scholars even argue that Patanjali and Vyasa are actually one and the same person, though others would strongly disagree with this thesis. Either way, this commentary is indispensable when it comes to making sense of the sutras, and published versions of the Yoga Sutras tend to include the bhasya commentary or at least reference it.

As a final note, many scholars now use the term pātañjalayogaśāstra to refer to this text as a whole (sutras plus commentary), because that is the name our oldest existing manuscripts use. But to keep things simple we will continue to use the name Yoga Sutras!

Structure of the Text

The Yoga Sutras are divided into the following four padas or chapters:

Samadhi Pada: This is where Patanjali defines Yoga and then describes the nature and the means to samadhi, the goal of Yoga.

Sadhana Pada: Sadhana is the Sanskrit word for practice or discipline. Here the author outlines two forms of Yoga, the kriya yoga (yoga of action) and the ashtanga yoga (the yoga of eight auxiliaries or limbs). This is also where Patanjali discusses the kleshas, five ‘afflictions’ or impediments to Yoga.

Vibhuti Pada: Vibhuti is the Sanskrit word for power or manifestation. Supra-normal powers (siddhis) are said to be acquired by the practice of Yoga. However, the temptation of these powers should be avoided and the attention should ultimately be fixed only on liberation.

Kaivalya Pada: Kaivalya literally means isolation. This is the chapter on final liberation. The Kaivalya Pada describes the process of liberation, it explains how the mind is constructed and veils the inner light of the Self.

The Goal of Yoga

Not one for a lengthy preamble, Patanjali gets stuck right in there and clearly states the goal of Yoga in the well-known second sutra:

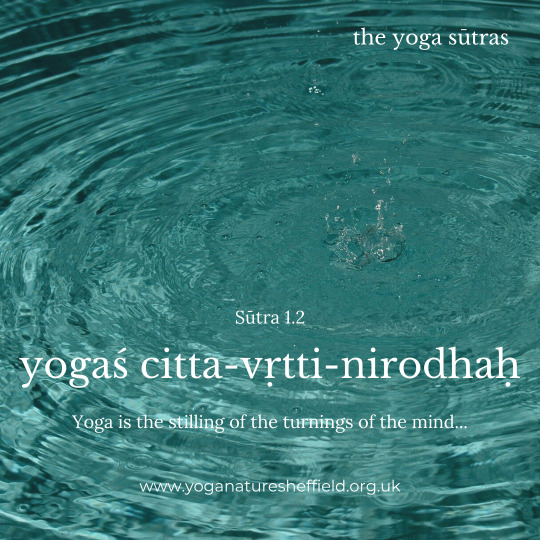

yogas chitta-vritti-nirodhah YS 1.2

Any Sanskrit sentence allows for a number of possible translations and this one is no different. A nice and accurate one is this one from Barbara Stoler Miller:

Yoga is the cessation of the turnings of thought

The reason I say this one is accurate is because a literal meaning of vritti is ‘turning’. Ever felt that thoughts are ‘going round and round’ in your head? Well this phrase nicely captures that! The vrittis in this statement refer to thoughts, emotions, ideas and basically any cognitive act of the mind. Patanjali lists five types of vrittis. These are, once translated:

Right knowledge

Error or false knowledge

Imagination

Sleep &

Memory

All such activities of the mind are products of prakriti and are completely distinct from the true Self, purusha, that pure awareness or consciousness which we are aiming to enter into through Yoga. The means prescribed by Patanjali in the first chapter of the Yoga Sutras to still the vritti states of mind are sustained practice (abhyasa) and dispassion (vairagya).

Specifically the practice offered is meditation, or keeping the mind fixed on any particular object of choice without distraction. Patanjali then describes a number of possible forms such meditation could take. By stilling all thought, meditation removes all objects of awareness. Awareness can therefore now be aware only of itself, of its own source, the true Self or purusha. This state is known as samadhi in Yoga and Patanjali makes it super clear that this state of samadhi is the goal of Yoga and thus the whole text is focused upon achievement of that goal.

Obstacles to Yoga

Patanjali mentions five kleshas, which can be translated as impediments or obstacles to achieving samadhi and thus Yoga. These five are as follows:

Ignorance

Ego

Desire

Aversion

Clinging

In the Yoga Sutras, and indeed in ancient Indian philosophy in general, the first item in any list is the most important and fundamental. It’s the same here. Ignorance here means failing to recognise our true Self or purusha and instead identifying ourselves with our body, mind and the material world. All of the other obstacles arise from this fundamental error.

Yoga Psychology

Like most other schools of Indian thought, the Yoga school believed in the related concepts of karma and rebirth. According to this doctrine, we are caught in an endless cycle of rebirths called samsara and the purpose of following a path such as Jainism, Buddhism or Yoga is to bring an end to this cycle. Where the Yoga Sutras really shine are in interpreting this doctrine in a highly sophisticated ‘psychological’ way, to use modern terminology.

According to this Yoga psychology, the mind forms an impression of an object through the sense organs, which is called a pratyaya. Once this pratyaya or active image of this object is no longer of active interest to the mind, it becomes an inactive or latent samskara. A samskara is an imprint left in the chitta, somewhat like a sound is imprinted on a tape recorder, or an image on photographic film. In this way the vrittis, the activities of the mind, are retained as samskaras when they fade.

It is important to note that these samskaras are not just passive imprints but vibrant latent impulses that can get activated under conducive circumstances and can exert influence on a person’s thoughts and behaviours, even many years after the impression was made. What’s more, according to Yoga these samskaras can persist from previous lives. The chitta is thus something of a storehouse of these recorded samskaras, deposited and accumulated there over countless lifetimes. One is here reminded of the theory of the subconscious in modern psychoanalysis.

According to Yoga, karma is generated by the vrittis, and the vrittis, in turn, are produced by the kleshas. There is thus a vicious cycle of kleshas, vrittis and samskaras. To run through the whole cycle again to try and make it as clear as possible: vrittis are recorded in the chitta as samskaras, and these samskaras eventually activate consciously or subliminally, producing further vrittis. These vrittis then provoke actions and reactions, which in turn are recorded as samskaras, and the cycle continues endlessly, leading to much suffering along the way.

The whole Yoga project aims to bring this vicious cycle to an end and it is liberation from this mind created suffering that we are after as yogis. The Yoga Sutras are effectively a manual guiding us towards this end, this state of samadhi or complete meditative consciousness.

The Yamas and Niyamas

The second pada or chapter of the Yoga Sutras contains a famous exposition of five ethical restraints (yamas) and five ethical observances (niyamas) and these are relatively well-known in the modern yoga world. The first thing to get clear is that these yamas and niyamas are NOT original or unique to Yoga. All ascetic schools in ancient India had these ethical codes, and the exact same ones appear in Jainism for example. Sometimes, you even get more of them. Some yoga texts for instance list 10 yamas and 10 niyamas.

The five yamas listed in the Yoga Sutras are:

Ahimsa (non-harming) Satya (truth telling) Asteya (non-stealing) Brahmacharya (chastity or celibacy) Aparigraha (non-acquisitiveness)

The five niyamas are:

Shauca (purity or cleanliness) Santosha (contentment) Tapas (self-discipline) Svadhyaya (study) Ishvarapranidhana (devotion to the Ishvara or Lord)

Many of these could do with further explanation and commentary but there is not space in this present article. The other thing I want to stress is that these yamas and niyamas were not seen as optional extras for yogis. Rather, these were the bedrock of fruitful yoga practice. Patanjali and others refer to them as the mahavratam or ‘great vow’. Importantly, having listed the yamas, Patanjali devotes an entire sutra to reiterating just how central and non-negotiable these yamas are. Once translated, this sutra reads as follows:

[These yamas] are considered the great vow. They are not exempted by one’s class, place, time or circumstance. They are universal. YS 2.31

So, regardless of your social status, regardless of where you live, in which time period you live, and any other extenuating circumstances (such as your career), adherence to the yamas, including especially ahimsa, the foundation of them all, is an essential part of being a yogi as defined by Patanjali’s system.

Vyasa is even more emphatic in his bhasya commentary to the Yoga Sutras, and it is here that the link between ahimsa and vegetarianism is explicitly and unequivocally made, and several examples are brought to bear. Refer to the work of scholar Jonathan Dickstein to read more about the strong case for vegetarianism made in Patanjali Yoga.

The Ashtanga Yoga

These yamas and niyamas are just the first two parts of Patanjali’s famous ashtanga or eight-part path. I would first like to clarify that this systematisation of yoga into a series of angas (a word translated by some modern scholars as ‘auxiliaries’ but more commonly rendered as ‘limbs’) was again not novel to Patanjali. Throughout the yoga tradition we find various similar schemes, predating and postdating Patanjali, including fourfold, fivefold, sevenfold and even fifteenfold schemes. I would also like to stress that, despite sharing the same name, this ashtanga yoga bears little relation to the modern postural form of yoga known as Ashtanga.

Following the yamas and niyamas then, we then have the following six angas:

Asana (posture): At last I hear you cry, postures! In Patanjali’s day meaning a steady and comfortable seated posture, asanas today comprise a set of physical exercises which stretch and strengthen the body. It is this aspect of yoga that has been most visibly exported to the West but too often stripped from its context as just one ingredient in a more ambitious and far-reaching sequence.

Pranayama (breath control): Prana refers to the universal life force whilst ayama means to regulate or control, but it can also mean to expand and lengthen. Prana is the vital energy needed by our physical and subtle layers, without which the body would perish. It is what keeps us alive. Pranayama is thus the control or expansion of prana through the breath, depending on which definition of ayama you use.

Pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses): This limb further deepens the above process by removing consciousness from all engagement with the senses (sight, sound, taste, smell and touch) and sense objects.

This is followed by the final three limbs collectively known as samyama: Dharana (concentration, fixation), Dhyana (meditation), and finally Samadhi (the latter of which Patanjali further divides into seven rather esoteric stages). These last three limbs are essentially different degrees of concentrative intensity and culminate in the realisation by the Self of its own nature.

Just to reiterate one more time, it is this Self-realisation, the state known as samadhi, that is the true goal of Yoga.

Relevance of the Yoga Sutras for Today

In this brief introduction we have of course only scratched the surface of this incredible text, and there is much more that could be said. But for now I want to end with some concluding reflections on the continuing relevance of the Yoga Sutras in the modern world.

One question that arises is whether Patanjali was prescribing a strictly ascetic path. And indeed, the general scholarly consensus has usually been to associate Patanjali's Yoga exclusively with extreme asceticism, mortification, denial and renunciation. However, there are dissenting vocies. For example, Ian Whicher has repeatedly and passionately argued that Patanjali's Yoga can be seen as enabling a more responsible living in and engagement with the world, and that Patanjali was not advocating total renunciation. For Whicher, following the path of Patanjali can lead one towards that integrated and embodied state of liberated selfhood whilst living, a state known as jivanmukti.

Regardless of whether Patanjali was historically preaching ascetism or not, the fact remains that the Yoga Sutras are full of valuable ideals and tools for the practitioner living in the modern world. Let’s face it though, this is a challenging path. As a scholar and practitioner I often perceive a huge disconnect between the kind of yoga I am seeing on the likes of Instagram and the teachings of the Yoga school as presented in the Yoga Sutras. After, all, the former is highly focused on body image, whereas the Yoga of Patanjali is all about dissociating ourselves from our body and mind and recognising our true Self. However, this does not mean that the two are necessarily irreconcilable.

Though there is absolutely no historical evidence that Patanjali and his followers were practicing postural yoga (that didn’t come until later with the emergence of the Hatha tradition) nowhere in the Yoga Sutras does it say that physical exercise cannot be part of one’s yoga practice. We just have to remember that as far as Patanjalian Yoga is concerned, such postural activity is just a further means or method on the path towards samadhi or full meditative awareness. This is why any so-called yoga that does not contain more internalised meditational practices but which focuses solely on physical exercise should not really be called yoga.

The Yoga Sutras remains undoubtedly the most famous ancient yoga text, and it is studied to some extent in probably every yoga teacher training course. To be honest, I personally feel that too much emphasis is placed on the Yoga Sutras, at the expense of other branches and other texts of the tradition. The Tantric texts, in particular, are still sorely neglected. One of my own aims in my work is to try and decentre the Yoga Sutras and provide a much wider overview of the history and philosophy of yoga and the other related schools of ancient India. This is not to take anything away from the Yoga Sutras, however, as it is without doubt an extraordinary text that continues to be highly relevant in the 21st century.

Further Reading

I have already mentioned some scholars whose work you may wish to refer to, such as Philipp André Maas, Ian Whicher and Barbara Stoler Miller. For a translation and commentary on the Yoga Sutras that is both scholarly accurate and reasonably accessible I would recommend that of Edwin Bryant published by North Point Press.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

YOGA is the discipline (art & science) of being fully present in the moment we are experiencing right NOW.

~ Vimal sharma

https://yogasutra195.com/sutra-1-1/

#yoga philosophy#sprituality#mindfulness#psychology#meditation#awarness#conciousness#yoga sutra#yoga sutras#patanjali#power of now#self awareness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last night I photographed a bunch of male Blue Ghosts floating around, searching for flightless females on the ground below.

I’ve read there are similar bioluminescent beetles in other parts of the world, but this specific species is unique to this region.

This is 20 back-to-back, 30-second long-exposures of the same spot. In other words, all the light my camera could capture for 10 straight minutes, combined into one image.

And sorry, I do not share blue ghost locations because I have seen too many people shine flashlights on them, try to catch them, etc and I’m not going to be a part of that. I do know people who offer guided tours (which is also great for people unfamiliar with being out in the forest at night), so please feel free to ask me for a referral for that.

[Asheville Pictures in Western North Carolina]

* * * *

19. The Mind is not self-luminous, since it can be seen as an object. This is a further step toward overthrowing the tyranny of the “mind”: the psychic nature of emotion and mental measuring. This psychic self, the personality, claims to be absolute, asserting that life is for it and through it; it seeks to impose on the whole being of man its narrow, materialistic, faithless view of life and the universe; it would clip the wings of the soaring Soul. But the Soul dethrones the tyrant, by perceiving and steadily affirming that the psychic self is no true self at all, not self-luminous, but only an object of observation, watched by the serene eyes of the Spiritual Man.

- Patañjali, The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. the Book of the Spiritual Man

[alive on all channels]

#Western North Carolina#Blue Ghosts#lightning bugs#quotes#Patanjali#The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali#alive on all channels

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

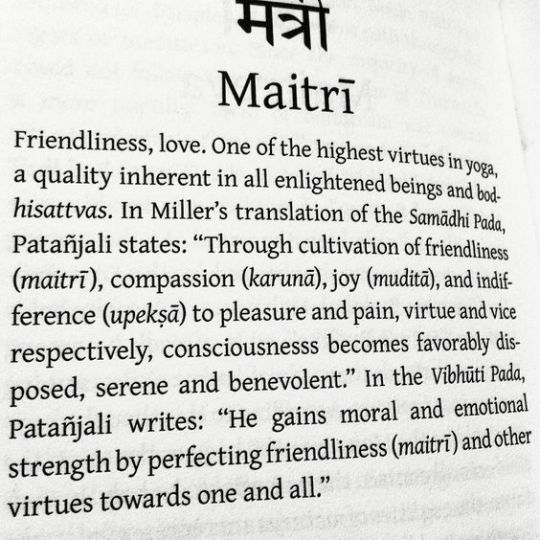

“Through cultivation of friendliness (मैत्री maitrī), compassion (करुण karuṇa), joy (: मुदित mudita), and indifference (उपेक्षा upekṣā) to pleasure and pain, virtue and vice respectively, the consciousness becomes favourably disposed, serene and benevolent.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga

Prática gradual e efetiva;

Até quatro alunos por grupo;

Para todas as idades;

Instrução com 15 anos de experiência.

MANHÃ/TARDE/NOITE

AULA EXPERIMENTAL GRÁTIS

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Una citazione di Patanjali da parte di Guru Dev per purificare la mente: Maharishi Patanjali, autore degli Yoga Sutra, ha fornito le seguenti istruzioni: Mantieni la mente in uno di questi quattro stati: maitri (cordialità), karuna (compassione), mudita (gioia) e upeksha (indifferenza)". (YS 1.33) Bisogna provare un sentimento di amicizia verso le persone che sono come noi e provare compassione per i subordinati o per chi sta attraversando un momento difficile. Con le persone più felici, più sagge o più istruite, o che vi superano in qualche modo, assicuratevi di guardarle con un sentimento di felicità. Con le persone che nutrono sentimenti di malignità e ostilità nei vostri confronti, invece, dovete adottare un atteggiamento di indifferenza, in modo da non ricambiare questo sentimento di inimicizia e odio. In questo modo, tenendo a mente queste quattro condizioni mentali, non sorgeranno nella mente sentimenti come invidia, malizia, gelosia, ecc., e la purezza innata della mente crescerà. In questo modo, non si verificano ostacoli negli affari di tutti i giorni. Con la scomparsa della sporcizia mentale, diminuisce il desiderio istintivo di esperienze sensuali e per questo motivo la mente diventa introversa e si impegna nell'adorazione di Bhagavan (Dio).

0 notes

Text

Tibetan Buddhism: A Path of Mind Training and Intrinsic Wisdom

In our journey of exploring spirituality across traditions, it is time to welcome the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism. At first glance, the colorful rituals, sacred music, and intricate costumes may seem confusing or overwhelming. Yet these outward forms are simply expressions of an inner practice that remains deeply practical and profound: the training of the mind. Tibetan Buddhism is not a…

View On WordPress

#Advaita Vedanta#atonement#Buddhist mystics#Buddhist Philosophy#Compassion#cultural spirituality#Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche#enlightenment#Inner peace#Interfaith harmony#intrinsic wisdom#meditation#mind training#Mindfulness#mystical traditions#non-duality#Spiritual Awakening#spiritual purification#Spiritual Transformation#St. John of the Cross#tantra#Tibetan Buddhism#Tibetan rituals#tulku#Vajrayana#yoga#Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

0 notes

Text

youtube

The Yoga Sutras, Sadhana Pada – The Path of Practice, Spiritual Practice, Yoga of Action, Karma.

#yoga sutras of patanjali#patanjali yoga sutras art of living#patanjali yoga sutras#yoga sutras#patanjali yoga sutra#the yoga sutras of patanjali#yoga sutras of patanjali chapter 1#patanjali yoga sutras explained#patanjali#patanjali yoga sutras english meaning#patanjali yoga sutras audiobook#patanjali yoga sutras with meaning#yoga sutras by patanjali#patanjali yoga sutras chanting#patanjali yoga sutras sadhguru#patanjali yoga sutras full chant#international day of yoga#vedanta society of new york#how to practice the 8 limbs of yoga#yoga practice#yoga sutras of patanjali explained#patanjali yoga sutras english meaning.#Youtube

0 notes

Text

6 books to understand yoga completely

The Yoga Rahasya of Nathamuni This ancient text by Nathamuni explores the esoteric and philosophical aspects of yoga. It delves into the deeper mysteries and hidden knowledge of yoga practice, providing a comprehensive overview of the subject. This book is a valuable resource for those seeking a deeper understanding of yoga beyond the physical postures.

The Healing Power of Mudras: The Yoga of the Hands This book explores the therapeutic benefits of hand mudras, or sacred hand gestures, in yoga and meditation. It explains how simple hand positions can rejuvenate the body, heal ailments, and facilitate spiritual awakening. This text is a valuable resource for those interested in the healing aspects of yoga.

Yoga Secrets of Psychic Powers This text uncovers the hidden yogic techniques for developing psychic abilities and supernatural powers. It covers practices to awaken the third eye, enhance intuition, and access higher states of consciousness. This book is a valuable resource for those interested in the spiritual and mystical aspects of yoga.

Vasistha Samhita (Yoga Kanda) The Vasistha Samhita is an ancient yoga scripture that delves into the advanced practices and philosophical underpinnings of yoga. The "Yoga Kanda" section focuses specifically on the technical aspects of yoga, providing a comprehensive guide to the subject.

A Systematic Course in the Ancient Tantric Techniques of Yoga and Kriya This comprehensive text provides a step-by-step guide to the ancient tantric practices of yoga and kriya. It covers a wide range of techniques for physical, mental, and spiritual development, making it a valuable resource for those interested in the spiritual and mystical aspects of yoga.

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali The Yoga Sutras, compiled by the sage Patanjali, is the foundational text outlining the eight limbs of classical yoga. It is an authoritative guide to the philosophy, psychology, and practice of yoga, providing a comprehensive overview of the subject. This book is a valuable resource for those interested in the philosophical and spiritual aspects of yoga.

0 notes

Text

Absolute Aloneness - Osho

Liberation is obtained when there is equality of purity between the purusha and sattva. The Chhandogya Upanishad has a beautiful story. Let us begin with it. Satyakam asked his mother, Jabala, “Mother, I want to live the life of a student of supreme knowledge. What is my family name? Who is my father?” “My son,” replied the mother, “I don’t know. In my youth, when I went about a great deal as a…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Siddhis | The Powers | Yoga Sutra's

Some thoughts on the Yoga Sutra’s | A Podcast Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment, Meditation and Self-Discipline “Nowhere on earth has the impulse toward transcendence found more consistent and creative expression than on the Indian subcontinent.” Georg Feuerstein Patanjali is an early scholar in the science of understanding the mind, and his compilation of the Yoga Sutras is considered a…

View On WordPress

#ancient wisdom#Awakening#Consciousness Exploration#Eastern Philosophy#Mental well-being#Mind Science#Patanjali#Self-realization#Yoga Philosophy#Yoga Practices#Yoga Sutras

1 note

·

View note

Text

The great Tantric master (mahasiddha) Virupa, who is said to have lived in the seventh century, became a wandering yogi after being an abbot of India’s greatest Buddhist monastery.

This painting shows him seated with a raised hand forming a gesture of subjugation. Virupa’s gesture—a raised hand with a finger pointing up to the sun—refers to an episode when he was on an epic drinking spree and agreed with the tavern proprietor to settle the bill at sunset. He then used his great meditative powers to stop the sun in its course until after several days without night the local ruler, fearful of a possible drought, paid his tab. This story emphasizes the magical abilities Virupa gained from tantric practices, which he transmitted to his students.

We hope you celebrate today by remembering Virupa and enjoying the sunshine! ________ Mahasiddha Virupa; Gongkar Chode Monastery, U Province, Central Tibet; ca. 1659-1671; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Art; C2004.14.1 (HAR 65340)

[Rubin Museum of Art]

* * * *

“36. The intellect and the Puruṣa (Ātman, Self) are totally different, the intellect existing for the sake of the Puruṣa, while the Puruṣa exists for its own sake. Not distinguishing this is the cause of all experiences; and by saṁyama on the distinction, knowledge of the Puruṣa is gained.

37. From this knowledge arises superphysical hearing, touching, seeing, tasting and smelling through spontaneous

38. These [superphysical senses] are obstacles to [nirbija] samādhi but are siddhis (powers or accomplishments) in the worldly pursuits.”

― Satchidananda , The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

#tantra#Mahasiddha Virupa#Siddhis#Rubin Museum of Art#Buddhist#Satchidananda#The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Patanjali Yoga Sutra

1 note

·

View note