#Palaeotodus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fossil Novembirb: Day 14 - Lost in the Woods

As the global climate was cooling during the Oligocene epoch, tropical rainforests started to shift towards their current distribution in the tropics, and open landscapes such as scrubland was spreading. But that doesn't mean forests were disappearing. In places like Central and Eastern Europe, forests shifted from tropical to temperate. And in these shifting landscapes, birds continued to adapt and diversify.

Turnipax: One of the earliest known members of a relatively obscure bird groups called buttonquails. Despite their quail-like appearance and lifestyle, buttonquails are shorebirds related to gulls and sandpipers.

Palaeotodus: This small insectivore is one of the first known members of the todies, a bird group nowadays restricted to the West Indies.

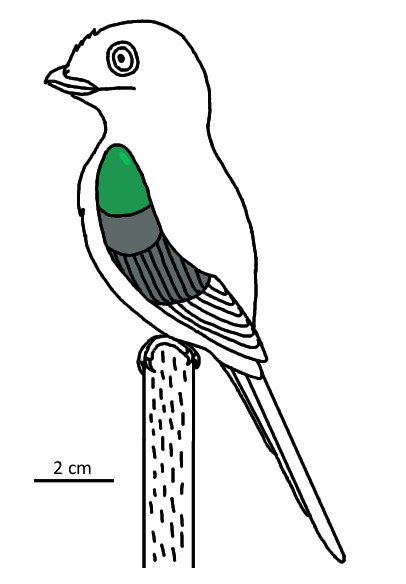

Primotrogon: An early member of the trogons which had a very different shape compared to its modern relatives, including long wings, a short tail, and relatively small eyes.

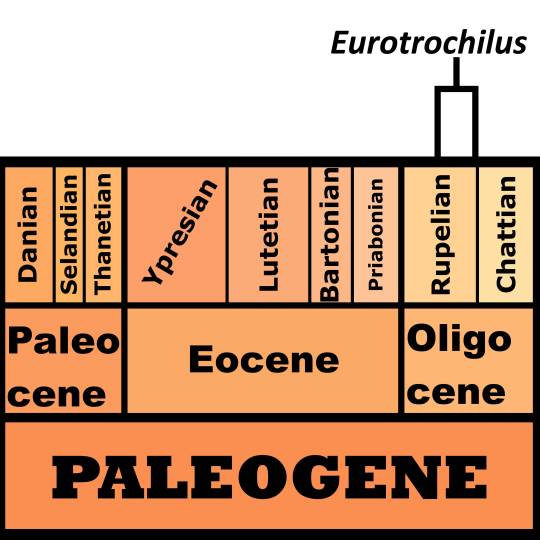

Eurotrochilus: The first known true hummingbird, a group now endemic to the Americas, but first appeared in Europe.

Aviraptor: A thrush-sized true hawk with long thin legs and sharp talons, this was a prime predator of small forest birds in the Oligocene.

Wieslochia: One of the earliest known passeriformes, a group that likely evolved in Australia,parts of it's skeleton resemble certain South American passeriforms, like cotingas.

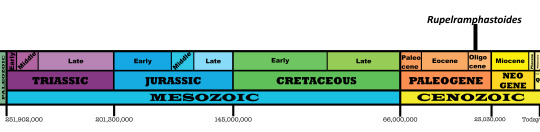

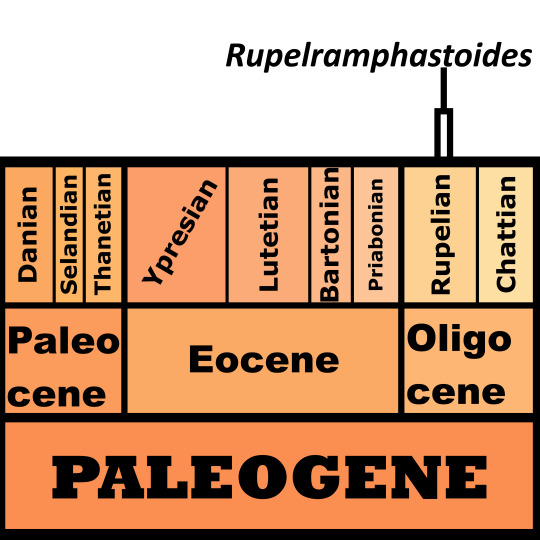

Rupelramphastoides: As the earliest known ramphastid, it was closely related to the barbets as well as toucans, but it bore a closer resemblance to the former.

Oligocolius: A bizarre relative of modern mousebirds that had an appetite for seeds, as the holotype was preserved with seeds in its crop and gullet. It also had a slightly parrot-like beak.

Laurillardia: A distant relative of hoopoes and hornbills, this long winged and long tailed bird used its sharp beak to catch insects.

Rupelornis: A close relative of albatrosses, these seabirds had delicate beaks and long legs. They probably had a similar lifestyle to storm petrels, which carefully pick food from the surface of the water.

#Fossil Novembird#Novembird#Dinovember#birblr#palaeoblr#Birds#Dinosaurs#Cenozoic Birds#Turnipax#Palaeotodus#Primotrogon#Eurotrochilus#Aviraptor#Wieslochia#Rupelramphastoides#Oligocolius#Laurillardia#Rupelornis

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 14: Lost in the Woods

Eurotrochilus by @iguanodont

Even though parts of the landscape were opening up, the forests of Europe weren't done yet - in fact, many began transitioning to the drier temperate forests we know from Europe today! This transition through the Oligocene would have major consequences for bird evolution - I mean, why else would I bring it up? The formation of the first permanent ice sheets in Antarctica made the world drier, and in turn lead to many of the European Islands of the Eocene connecting with one another, forming an actual continent. Well, sub-continent.

So we saw h ow birds were adapting to the plains - how did they adapt to the temperate forests? Well, by more modern groups appearing, too! In fact, this was a busy period of evolution for most animals, as early forms gave way to modern clades and the early adapations that make those clades unique begin to pop up.

Aviraptor by @otussketching

Eurotrochilus, known from Germany during the Oligocene, is a prime example of this phenomenon: it looks almost identical to living hummingbirds, but - unlike living hummingbirds - it was in Europe, not the Americas! Though it wasn't quite a modern hummingbird, having long finger bones like ancestral forms, it had the adaptations needed for feeding on nectar and hovering while foraging for food. As a pollinator, it would have been a key component of the forest ecosystem, helping to pollinate flowering plants and keeping the forest growing. It was also exceptionally common, and may have lead to many plants co-evolving with hummingbirds in the Eastern Hemisphere - so that when hummingbirds disappeared from the region, the niche was left open for the passerine Sunbirds to one day fill it.

We also start to see more and more flighted birds of prey, like Aviraptor. Though small in size, it had long slender legs and sharp talons, and was thus the first raptor adapted for eating other birds as prey - to capture them in the air mid-flight. Sure, it mainly ate small ones, but we all have to start somewhere! And, with all of those lovely hummingbirds and early passerines and barbets around, it certainly had enough food to eat.

Rupelramphastoides by @drawingwithdinosaurs

Yep, I said barbets - the earliest known barbet-like bird comes from the Oligocene European Forests, Rupelramphastoides. One of the smallest members of the Toucan-Barbet group, it had a lot of very modern traits from the group for its early evolution - including long and slender foot bones like living Toucans! It had a small beak, like barbets, and squat wings for flitting about between the trees. Like its living relatives, it probably ate fruit - which would have been plentiful - as well as insects.

Wieslochia, which I discussed on Passerine day, was also present in these forests - it was just a great place for modern tree-dwelling birds to really get their start! Relatives of hoopoes and hornbills, like Laurillardia, were also present - and had long wings and tails, probably for display in addition to movement. Palaeotodus was present in these forests as well as in the savannah, indicating that it was flexible in its preferred habitat - like the living todies of the Caribbean today. Why todies today are only limited to the Caribbean islands, however, remains a mystery.

Oligocolius by @quetzalpali-art

Mousebirds haven't been limited to their modern range yet, either! Though not a Sandcoelid, Oligocolius was a weird Mousebird with the hooked bill of a modern parrot! So, clearly, Mousebirds were experimenting with lots of different niches prior to the modern day - and this is a neat example of convergent evolution to boot! It had a crop, unlike its living relatives, which allowed it to digest tougher plant material. It was common in its environment, found both in the forests and in more lacustrine and coastal areas, indicating it was flexible in this changing world - an extremely helpful adaptation as the ecosystems evolved!

Primotrogon, an early relative of trogons, breaks the pattern of "Like Modern Relatives but Slightly Off" that we've been seeing with these birds - unlike living trogons, it had long wings, a short tail, and small eyes! In addition to it's weirdness, we actually know the color of this bird - it had green secondary coverts, with grey secondaries and primary coverts, though the color of the primaries is not known. Given the rareness of green in animal colors, but how commonly it comes up in birds, this is another example of that phenomenon!

Primotrogon by @albertonykus

Tree dwelling birds aren't the only birds that live in forests, and they aren't the only ones that underwent radiation during this period of environmental change. A weird group of "shorebirds", the Buttonquails, first appears in this ecosystem in the form of Turnipax. Like quails, they are small round ground dwelling birds, but weirdly, their closest relatives are gulls and sandpipers! Turnipax seems to have already been much like its modern relatives, and its possible that the lower diversity of landfowl allowed other avian groups to fill these niches. Rupelornis, a relative of albatross, also lived in the forests of this time - and probably was an ocean going bird, living like modern storm petrels and plucking food carefully from the surface of the water. Like other sea birds, it may have been in forest habitats for the protection - for nesting, rearing young, or other activities. It's a lot easier to hide in the trees than it is to hide at the beach!

This time of environmental turmoil gave dinosaurs new opportunities to diversify - and required flexibility to do so, as the landscape ebbed and flowed between savannah and forest much as it does today. Alas, the climate would not remain stable, and as we continue through the Cenozoic, more and more ecological turmoil will continue to have lasting effects on the evolution of living dinosaurs.

Sources:

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bathornis

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Tall Bird

First Described by: Wetmore, 1927

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Bathornithidae

Referred Species: B. celeripes, B. cursor, B. fax, B. fricki, B. geographicus, B. grallator, B. minor, B. veredus

Status: Extinct

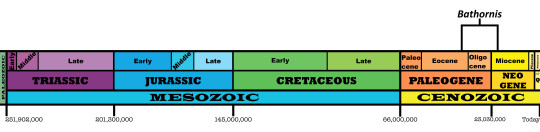

Time and Place: From 37 to 20 million years ago, between the Priabonian of the Eocene of the Paleogene and the Burdigalian of the Miocene of the Neogene

Bathornis is known from a very wide number of formations - which makes sense, given how many species have been referred to the genus. Bathornis is known from the Chadron Formation, the Brule Formation, the Willow Creek Site (not Formation, that’s from the Cretaceous because people keep reusing names), the Washakie Formation, and the Willwood Formation - and it is possible that it is also known from other locations throughout North America. It appears to have concentrated on the western half, however, being known from formations in Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Physical Description: Bathornis was a large, flightless predatory dinosaur from the Cenozoic - and, despite being in the same general group of birds as they, it isn’t a terror bird! Bathornis, unlike the Terror Birds, still had decently sized wings (even though they couldn’t be used in flight) and, more importantly, it had a well-developed hind toe, whereas the Terror Birds had reduced hind toes. Still, it was doing essentially the same thing, but in North America. It had long, thin legs, built well for running; a squat body; small-ish wings; reduced musculature in the shoulder and chest area; large heads, and long, sharp beaks. These beaks weren’t as tall as those found in the Terror Birds, but that didn’t take away from their ability to pack a devastating bite. The variety of species ranged widely in size, with some as short as 60 centimeters, and some as tall as 2 meters (though it is possible the smaller species were just juveniles).

By Julio Lacerda

Diet: Bathornis was a terrestrial carnivore, able to utilize its large beak to grab and crush large prey - even large mammals. It is even possible that in many environments, Bathornis was one of the primary large predators, similar to the Terror Birds of the south.

Behavior: Bathornis, being a very large terrestrial predator, would have spent a good portion of its time on the move. Its long, strong legs were good for running, as well as probably kicking. Not being able to fly, they would have relied on their legs to get around and chase prey. Powerful kicks of the legs would have aided Bathornis in killing its prey, however, it would have primarily relied upon its beak to deliver the final blows. The powerful crushing action of the beak would have allowed it to break apart extremely tough prey, potentially even crushing bone. It may have still used its wings in some flapping action to aid in hunting, though it doesn’t seem likely it used them as much as the earlier terrestrial raptors of the Mesozoic era. Being a predator, it doesn’t seem likely that Bathornis was very social; modern Seriemas hunt primarily alone, and there’s no evidence Bathornis did otherwise. Still, it probably did care for its young in some capacity.

By Nix, CC BY-NC 4.0

Ecosystem: Bathornis is known from a variety of ecosystems across Northwestern America in the Cenozoic Era; it seems, however, it favored wetlands to open savanna and grassland. It may have also been found in more sparse woodland. This means that, while it was fast, running great distances across open habitat wasn’t its usual activity. It may have even used its long legs to aid in wading through the water towards sources of food. That doesn’t mean it never inhabited open areas, of course - just that it probably preferred bogs and swamps to prairies. Bathornis often lived alongside large mammals, including large mammalian predators such as Haenodonts, Entelodonts, and Nimravids. Odd-toed ungulates like Megacerops and Merycoidodon were often found closely associated with Bathornis, indicating that they were common sources of prey for this dinosaur. It also was often found with its close relative, Paracrax, which would have been direct competition for it. Many other dinosaurs are known to have lived alongside Bathornis, more than I can reasonably list; but it probably encountered the fowl Procrax, the flighted predator birds Phasmagyps and Palaeoplancus, the tody Palaeotodus, the flighted ratites Lithornis and Paracathartes, the large herbivorous bird Gastornis, the flightless wading birds Geranoides and Palaeophasianus, the owl Eostrix, the mousebirds Anneavis and Eobucco, and the Sandcoleid sandcoleus. It’s interesting that Bathornis quite probably encountered Gastornis, given that Gastornis used to be thought to have Bathornis’ job, and is now known to have been a similarly-sized large herbivore instead.

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: Bathornis was very closely related to the contemporaneous (but Southern) Terror Birds, but it actually evolved for the same niche independently. This happened all over their group of dinosaurs, the Cariamiformes (Seriemas and their many, many extinct relatives). This indicates that the long-legged terrestrial predatory lifestyle of the Seriema group made them especially prone to growing larger, and losing their flight capabilities. The common nature of Bathornis and its relatives in the Northern Hemisphere is also important biogeographically. Many think that the Terror Birds went extinct due to the influx of large mammal predators after North and South America combined. However, Bathornis lived alongside these North American Large Mammals - and even thrived in its environment. So, clearly, large avian predators and large mammalian predators were perfectly capable of coexisting. So why did Bathornis - and then, later, their southern Terror Bird cousins - go extinct? Jury is, sadly, still out.

By Scott Reid

Species Differences: There are a wide variety of species of Bathornis, though some may not be the same species, and it is entirely possible that these animals shouldn’t be grouped under one genus from a phylogenetic standpoint. B. veredus is known from the Eocene and Oligocene of the Chadron Formation, and was about the size of a living emu. B. cursor is different from B. veredus primarily because of differences in the ankle, and it was slightly larger and earlier in time. B. geographicus is known from South Dakota, Nebraska, and Wyoming, and it may be a descendant of B. veredus; it was larger than both veredus and cursor, and it is possibly the largest species in the genus. B. fax is the smallest species known, but it also lived with B. veredus and is probably just the juvenile form. B. celeripes is known from the end of the Oligocene, and it was about the same size as B. cursor, so a mid-sized species of the genus. B. fricki is from the Early Miocene, making it one of the youngest species of all; it may have been a direct descendant of B. celeripes, to which it was very similar. B. minor lived in the same time and place as B. fricki, and they differ due to small changes in the leg bones. B. grallator, finally, is the best known form; coming from the Eocene, it was originally called Neocathartes before being combined into Bathornis by Mayr in 2016. It was originally thought to be flighted, but further research has shown it was also flightless. It was actually first thought to be a vulture! Life is funny like that.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Angolin, F. L. 2009. Sistemática y Filogenia de las Aves Fororracoides (Gruiformes, Cariamae). Fundación de Historia Natural Felix de Azara: 1 - 79.

Benton, R. C., D. O. Terry, E. Evanoff, H. G. McDonald. 2015. The White River Badlands: Geology and Paleontology. Indiana University Press.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Cracraft, J. 1968. A review of the Bathornithidae (Aves, Gruiformes) with remarks on the relationships of the suborder Cariamae. American Museum Novitates 2326: 1 - 46.

Cracraft, J. 1971. Systematics and evolution of the Gruiformes (Class Aves). 2, Additional comments on the Bathornithidae, with descriptions of new species. American Museum Novitates 2449: 1 - 14.

Galbreath, E. C. 1953. A contribution to the Tertiary geology and paleontology of northeastern Colorado. University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions Vertebrata 4:1-120.

Lambrecht, K. 1933. Handbuch der Palaeornithologie. 1-1024

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G., J. Noriega. 2013. A well-preserved partial skeleton of the poorly known early Miocene seriema Noriegavis santacrucensis (Aves, Cariamidae). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Mayr, G. 2016. Osteology and phylogenetic affinities of the middle Eocene North American Bathornis grallator - one of the best represented, albeit least known Paleogene cariamiform birds (seriemas and allies). Journal of Paleontology 90 (2): 357 - 374.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Olson, S. L. 1985. Farner, D. S., ed. The Fossil Record of Birds, section X. A. I. b. The Tangle of the Bathornithidae. Avian Biology 8. New York: Academic Press. 146 - 150.

Wetmore, A. 1927. Fossil birds from the Oligocene of Colordao. Proceedings of the Colorado Museum of Natural History 7 (2): 1 - 14.

Wetmore, A. 1944. A new terrestrial vulture from the Upper Eocene deposits of Wyoming. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 30: 57 - 69.

Wetmore, Alexander (1950). "A Correction in the Generic Name for Eocathartes grallator". Auk. 67 (2): 235.

#Bathornis#Bird#Dinosaur#Australavian#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Birds#Bathornithid#Carnivore#Terrestrial Tuesday#Paleogene#Neogene#North America#Bathornis celeripes#Bathornis cursor#Bathornis fax#bathornis fricki#Bathornix geographicus#Bathornis grallator#Bathornis minor#Bathornis veredus#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oligocolius

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Oligocene Mousebird

First Described By: Mayr, 2000

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Coraciimorphae, Coliiformes, Coliidae

Referred Species: O. brevitarsus, O. psittacocephalon

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 31 and 24.7 million years ago, from the Rupelian to the chattian of the Oligocene

Oligocolius is known from the Bott-Eder Grube Unterfeld and the Enspel Maar Lake of Germany

Physical Description: Oligocolius is a fascinating little bird because it is a Mousebird - a group of dinosaurs today with magnificent little crests and soft, grey appearances - but, in at least one species, it didn’t have a typical Mousebird beak. Instead of having a short, triangular beak, this bird had the dramatically hooked bill of a parrot! With a large, round head and a hooked, sharp beak, it would have been very hard to tell apart Oligocolius from a living parrot when just looking at the head. This is a clear-cut case of convergent evolution, since mousebirds and parrots are nowhere near closely related to each other. Oligocolius was weird in other ways too - it had longer wings than living Mousebirds, and shorter legs, so it was more adapted for flight than living members of the genus. Interestingly enough, it also seems to have had a crop, which is something living Mousebirds lack; this indicates that it fed on tougher to digest plant material than Mousebirds today do - meaning, it wasn’t only eating fruit like its living relatives. Instead, it was able to eat tougher to digest plant material in addition to fruit. Whether or not its feathering would have been as weird as its living relatives is difficult to say without more fossils. It is difficult to say what its size would have been, as no tail feathers are preserved and the mousebirds today are distinctive for their long tails, but it seems likely they were about as big as living forms, reaching sizes around 10 centimeters in length.

Diet: Oligocolius would have fed on a variety of plant material, rather than exclusively fruit; in addition to fruit, it probably would have favored seeds, which it could easily crack open with its parrot-like beak.

Behavior: Oligocolius would have flown too and fro in its forested environment, searching for food and spending less time perched than its living relatives. It would probably gather seeds, fruit, and other plant material from trees as it flitted about, holding and crushing the food with its strong beak. Despite being rare in terms of fossils, it was probably very social like its living relatives, forming somewhat large family flocks in the forests. It would have taken care of its young, even potentially building cup-shaped nests out of twigs in trees. It is probable that it would have been very distinctive in appearance, as its living relatives are, and used that appearance for communication.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Oligocolius was probably a fairly common fixture of the forests of the Oligocene in Germany, having been found in two different environments from across the epoch. It is known from primarily forested areas near bay and estuary coastlines, as well as a prehistoric freshwater lake with a variety of shore plants and swamps, so it wasn’t picky about where it ended up. O. brevitarsus, in the earlier Bott-Eder environment, it lived alongside many different kinds of birds that I’ve mentioned in articles past: the hummingbird Eurotrochilus, the barbet Rupelramphastoides, the trogon Primotrogon, the loon Colymboides, the seabird Rupelornis, the songbird Wieslochia, the tody Palaeotodus, and the buttonquail Turnipax. There were also a variety of mammals. At the later Enspel swamp-lake, there were rodents like Eomyodon, pikas, and moles, as well as crocodilians and turtles; as for other birds, there was the pheasant Palaeortyx, the cormorant Borvocarbo, and a loon.

Other: Oligocolius is closely related, but not entirely in, the group of living mousebirds. In fact, Oligocolius is one of many known extinct mousebirds, showcasing that this group was much more diverse in the past than it is today. The weird parrot-like beak of Oligocolius is just one of many evolutionary paths the mousebirds took during the Cenozoic era.

Species Differences: O. brevitarsus is the first described species of this genus, and does not have an associated head; thus, it cannot be said with any certainty that it had the parrot beak, though that does seem likely. It comes from earlier and more southward than O. psittacocephalon. O. psittacocephalon, in addition from being later in time and a more northward location, it also had differently proportioned limbs than its earlier cousin.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Frey, E., and S. Monninger. 2010. Lost in action–the isolated crocodilian teeth from Enspel and their interpretive value. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 90:65-8

Herrmann, M. 2010. Palaeoecological reconstruction of the late Oligocene Maar Lake of Enspel, Germany using lacustrine organic walled algae. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 90 (1): 29 - 37.

Mayr, G. 2000. A new mousebird (Coliiformes: Coliidae) from the Oligocene of Germany. Journal of Ornithology 141(1):85-92

Mayr, G., and C. Mourer-Chauviré. 2004. Unusual tarsometatarsus of a mousebird from the Paleogene of France and the relationships of Selmes Peters, 1999. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(2):366-372

Mayr, G., M. Poschmann, and M. Wuttke. 2006. A nearly complete skeleton of the fossil galliform bird Palaeortyx from the late Oligocene of Germany. Acta Ornithologica 41(2):129-135

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2013. Late Oligocene mousebird converges on parrots in skull morphology. Ibis 155: 384 - 396.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Storch, G., B. Engesser, and M. Wuttke. 1996. Oldest fossil record of gliding in rodents. Nature 379(439):439-441

Tütken, T., and J. Absolon. 2015. Late Oligocene ambient temperatures reconstructed by stable isotope analysis of terrestrial and aquatic vertebrate fossils of Enspel, Germany. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 95:17-31

#Oligocolius#Oligocolius brevitarsus#Oligocolius psittacocephalon#Mousebird#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Bird#Birds#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Paleogene#Eurasia#Herbivore#Flying Friday#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eurotrochilus

By Scott Reid

Etymology: European Hummingbird

First Described By: Mayr, 2004

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Strisores, Daedalornithes, Apodiformes, Trochilidae

Referred Species: E. inexpectatus, E. noniewiczi

Status: Extinct

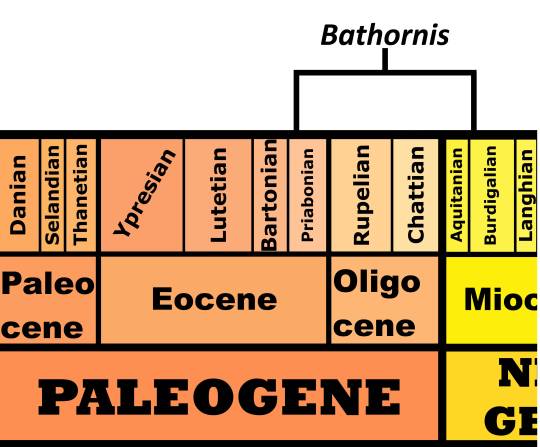

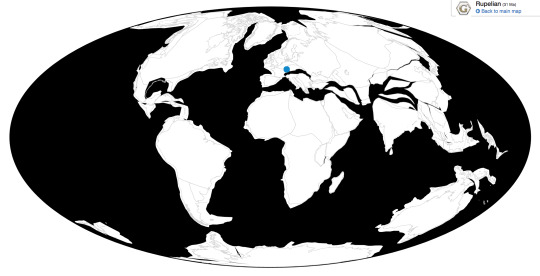

Time and Place: Between 31 and 28 million years ago, in the Rupelian of the Oligocene

Eurotrochilus is known from the Menilite Formation, the Bott-Eder Grube Unterfeld, and Le Grand Banc locations across Poland, Germany, and France

Physical Description: Eurotrochilus is a bird that is remarkable precisely because, to us, it is utterly unremarkable. Put in a clearer way, Eurotrochilus is almost identical to living Hummingbirds - but it’s thirty million years old. An extremely small bird, Eurotrochilus had wings shaped like hummingbirds - small, triangular, and built for hovering flight. It was about nine centimeters in length, making it as big as living hummingbirds like the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. In addition to having small, triangular wings, Eurotrochilus had tiny legs, like living Hummingbirds, and a very long beak. So, its identical nature to living hummingbirds points to the hummingbird body plan as an ancient one, that hasn’t been improved upon much during the Cenozoic era. Still, it wasn’t a true hummingbird yet - aka in the group that contains modern hummingbirds and those more closely related to one sort than the other - because it still had long finger bones, and smaller connections between those bones. So, while the general hummingbird shape was present for thirty million years, it still had some modifications left to go.

Diet: With its very long, specialized bill, Eurotrochilus would have fed on nectar, like living hummingbirds.

Behavior: We can be fairly confident that Eurotrochilus was capable of hovering, and did so with some regularity; it would hover near flowers and rarely perch on them while gathering nectar up with its long beak. The beak would go into the center of the flower to draw up nectar, and in the process Eurotrochilus would pick up pollen. Then, upon going to the next flower to drink more nectar, Eurotrochilus would drop off the pollen, thus helping the flowers to reproduce. It would have spent most of its time hovering, and when not hovering would rest on branches or in more foliage-filled areas. It would have been a fairly active animal, and loud as well, making a variety of chirps and calls to one another. They probably would have been very brightly colored, like living hummingbirds, and the males probably wouldn’t have been very involved in nest care.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: Eurotrochilus primarily lived in forested areas, near lagoons, lakes, and estruary-filled areas. These lush habitats were filled with a variety of flowering plants for Eurotrochilus to feed on, and the forests were densely populated with birches, oaks, cypresses, conifers, palms, roses, asterids, and beeches. Eurotrochilus was a common site in these environments, which featured a variety of birds that resembled living forms and yet, were not quite like their modern counterparts. In the Bott-Eder environment of Germany, a coastal bay area, Eurotrochilus lived with birds such as the barbet Rupelramphastoides, the buttonquail Turnipax, the tody Palaeotodus, the mousebird Oligocolius, the trogon Primotrogon, the loon Colymboides, the seabird Rueplornis, and the songbird Wieslochia. This is a notable environment with a variety of transitional tree and ocean going birds, making it a fascinating habitat in which to study the evolution of dinosaurs in the Cenozoic. There were also sea cows, bats, and a Hyaenodont Apterodon, though Eurotrochilus would have been so small its unlikely that the Hyaenodont would have posed a problem for it. In the dense lake environment of Menilite, Eurotrochilus lived with the passerines Jamna, Resoviaornis, and Winnicavis, as well as the woodpecker Picavus. Here there was an extensive amount of thermal activity, which would negatively affect the ecosystem with gas bubbles and oil wells. In the lagoon environment of Le Grand, there was also Primotrogon, the early cuckoo Eocuculus, the crane Parvigrus, and the stem-passerine Zygodactylus.

Other: As the oldest representative of a proper, nectar-eating hummingbird shape, Eurotrochilus is vital for our understanding of the evolution of hummingbirds. In fact, its presence points to the idea that flowers pollinated by birds co-evolved with hummingbirds in the Eastern Hemisphere, even though hummingbirds aren’t present on that side of the globe today. Hummingbirds like Eurotrochilus, however, disappeared from that half of the globe during tropical climate collapse in Europe and the effects of the ice age. Interestingly enough, they were replaced in the Eastern Hemisphere by Sunbirds, a group of passerines that convergently evolved similar adaptations for hovering and nectar-eating, and also brightly colored feathers.

Species Differences: The two species of Eurotrochilus mainly differ on the proportions of the limbs, with E. noniewiczi having longer upper arm bones than E. inexpecattus, but shorter lower arm bones. They lived at the same time and fairly close to each other, so this difference is important in telling apart the varying kinds of these early hummingbirds.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Bochenski, Zygmunt; Bochenski, Zbigniew (19 December 2007). "An Old World hummingbird from the Oligocene: a new fossil from Polish Carpathians". Journal of Ornithology. 149 (2): 211

Bochenski, Zbigniew M.; Tomek, Teresa (10 December 2013). "A review of avain remains from the Oligocene of the Outer Carpathians and Central Paleogene Basin". Proceed. 8th Internat. Meeting Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution.

Louchart, Antoine; Tourment, Nicolas; Carrier, Julie; Roux, Thierry (27 September 2007). "Hummingbird with modern feathering: an exceptionally well-preserved Oligocene fossil from southern France". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (2): 171–175.

Mayr, Gerald (7 May 2004). "Old World Fossil Record of Modern-Type Hummingbirds". Science. 304 (5672): 861–874.

Mayr, Gerald (March 2005). "Fossil hummingbirds in the Old World". Biologist. 52 (1): 16.

Mayr, Gerald (25 July 2006). "New specimens of the early Oligocene Old World hummingbird Eurotrochilus inexpectatus". Journal of Ornithology. 148 (1): 105–111.

Mayr, Gerald (8 September 2009). "New specimens of the avian taxa Eurotrochilus (Trochilidae) and Palaeotodus (Todidae) from the early Oligocene of Germany". Springer. 84 (3): 387–395.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Maxwell, Erin E. (1 December 2016). "The Rauenberg fossil Lagerstätte (Baden-Württemberg, Germany): A window into early Oligocene marine and coastal ecosystems of Central Europe". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 463.

Prum, Richard O.; Berv, Jacob S.; Dornberg, Alex; Field, Daniel J.; Townsend, Jeffrey P.; Lemmon, Emily Moriarty; Lemmon, Alan R. (2015). "A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing". Nature. 526: 569–573.

Reddy, Sushma; et al. (2015). "Why do phylogenomic data sets yield conflicting trees? Data type influences the avian tree of life more than taxon sampling". Systematic Biology. 66 (5): 857–879.

#Eurotrochilus#Hummingbird#Dinosaur#Strisorian#Bird#Birds#Dinosaurs#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Eurotrochilus noniewiczi#Eurotrochilus inexpectatus#Paleogene#Flying Friday#Europe#Nectarivore#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rupelramphastoides knopfi

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Barbet from the Rupelian

First Described By: Mayr, 2005

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Coraciimorphae, Cavitaves, Eucavitaves, Picocoraciae, Picodynastornithes, Piciformes, Pici, Ramphastides?

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 31 and 30 million years ago, in the Rupelian of the Oligocene of the Paleogene

Rupelramphastoides is known from the Bott-Eder Grube-Unterfeld Quarry of Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Physical Description: Rupelramphastoides is the oldest known barbet-like bird - the barbets being a group of tree-dwelling birds that includes the iconic Toucans, though most barbest don’t have nearly as impressive beaks. This bird resembled its modern relatives in a lot of ways, which is notable given how old it is (still in the Paleogene, aka the first period of the time of modern birds). However, it is also one of the smallest members of the group overall, with very long and slender bones in its foot like modern toucans. Still, it had a small beak - more like non-toucan barbets - and a much smaller size than the living toucans. It had long and narrow arm bones but shorter fingers, giving the wings a more squat appearance at the ends. In general, its legs were slender, as were its toes, so perhaps Rupelramphastoides represents a transitional form between most barbets and the very weird toucans, though this is just conjecture. It probably wouldn’t have gotten much longer than 9 centimeters in overall body length, and it had a small head with a robust triangular beak.

Diet: It is uncertain what Rupelramphastoides ate, but like living barbets and toucans it probably mainly ate fruit, with mainly some supplementing of its diet with insects.

Behavior: Rupelramphastoides would have probably spent most of its time in the trees, hopping around and walking from branch to branch in search of food. It then probably would have stretched about to try and get food, using its beak to chomp into berries and other fruits. It could also use its long and skinny legs to stand up tall and reach food that it couldn’t otherwise. It probably lived in small flocks rather than big ones, and took care of their young. They also probably didn’t migrate. Like other members of the Pici, it was probably at least somewhat brightly colored, and used color in display to one another.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Rupelramphastoides lived in a coastal/bay area, filled with estuaries and streams leading out into the ocean. This was a very lush habitat, filled to the brim with plants from algae ferns and cycads; to conifers, palms, roses, asterids, beeches, oaks, and cypresses. This dense coastal forest transitioned into water-based plants, and its possible there was some sort of a coastal swamp (a proto-mangrove swamp, even?) in the area. This is fascinating as this habitat existed just at the time of the global rainforest collapse, and the transition of the world into more varied and arid habitats - clearly, this particular coastal swamp was not hit by this event. Dozens of kinds of fish lived here, including things like trumpetfish, boarfishes, eels, ladyfish, sea robins, rockfish, shrimpfish, pipefish, sailfin moonfishes, halfbeaks, sea breams, weevers, and so many others that I just have to stop now. There were sharks and rays present as well, though not in as much diversity as the ray-finned fish. Insects such as beetles, flies, and butterflies were present, as well as spiders, crustaceans, snails, slugs, clams, oysters, and other invertebrates. Plenty of turtles were also present. Mammals were rarer in this habitat, but included extinct relatives of modern sea cows and bats; and a predatory Hyaenodont named Apterodon. Many different kinds of dinosaurs lived here alongside Rupelramphastoides, including the early hummingbird Eurotrochilus, the buttonquail Turnipax, the tody Palaeotodus, the (rare example of a) fossilized songbird Wieslochia, the mousebird Oligocolius, the trogon Primotrogon, the loon Colymboides, and the seabird Rupelornis that vaguely resembled modern albatrosses and petrels. In short, you could see a wide variety of ocean-going and tree-dwelling birds, as one would expect in a forested esturary area, and Rupelramphastoides probably mostly had to worry about predation from they Hyaenodonts in the area, rather than other birds.

Other: The exact phylogenetic affinities of Rupelramphastoides are very murkey, because a phylogenetic analysis has never been done on this dinosaur. Morphologically speaking it seems to be somewhere in the Barbet-Toucan clade, with similarities to both non-toucan barbets and the toucans, but it also has traits of other members of Pici such as the honeyguides, piculets, and woodpeckers, and so it can’t really be confirmed as a member of Ramphastides for now.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Frey, E., W. Munk, M. Böhme, M. Morlo, and M. Hensel. 2010. First creodont carnivore from the Rupelian Clays (Oligocene) of the Clay Pit Unterfeld at Rauenberg (Rhein-Neckar-Kreis, Baden-Württemberg): Apterodon rauenbergensis n.sp. Kaupia 17:103-113

Mayr, G. 2000. A new mousebird (Coliiformes: Coliidae) from the Oligocene of Germany. Journal of Ornithology 141(1):85-92

Mayr, G. 2004. Old World fossil record of modern-type hummingbirds. Science 304:861-864

Mayr, G. 2005. New trogons from the early Tertiary of Germany. Ibis 147(3):512-518

Mayr, G. 2005. A tiny barbet-like bird from the Lower Oligocene of Germany: the smallest species and earliest substantial fossil record of the Pici (Woopeckers and allies). The Auk 122 (4): 1055–1063.

Mayr, G., and A. Manegold. 2006. New specimens of the earliest European passeriform bird. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51(2):315-323

Mayr, G., and C. W. Knopf. 2007. A stem lineage representative of buttonquails from the Lower Oligocene of Germany – fossil evidence for a charadriiform origin of the Turnicidae. Ibis

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Maxwell, E. E., S. Alexander, G. Bechly, K. Eck, E. Frey, K. Grimm, J. Kovar-Eder, G. Mayr, N. Micklich, M. Rasser, A. Roth-Nebelsick, R. B. Salvador, R. R. Schoch, G. Schweigert, W. Stinnesbeck, K. Wolf-Schwenninger, and R. Zeigler. 2016. The Rauenberg fossil Lagerstätte (Baden-Württemberg, Germany): A window into early Oligocene marine and coastal ecosystems of Central Europe. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 463:238-260

Micklich, N. R., J. C. Tyler, and G. D. Johnson, E., Swidnicka and A. F. Bannikov. 2009. First fossil records of the tholichthys larval stage of butterfly fishes (Perciformes, Chaetodontidae), from the Oligocene of Europe. Palaeontologische Zeitschrift 83:479-497

Micklich, N., and L. H. Hildebrandt. 2010. Emergency excavation in the Grube (Unterfeld) Frauenweiler clay pit (Oligocene Rupelian; Baden-Wurttemberg, S Germany): New records and palaeoenvironmental informatino. Kaupia 17:3-21

Micklich, N. 2011. Emergency excavation in the Grube Unterfeld (Frauenweiler) clay pit (Oligocene, Rupelian: Baden-Wurttemberg, S. Germany): New records and palaeoenvironmental information. European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists Program and Abstracts 9:42

Monninger, S., and E. Frey. 2008. Humming birds and sea cows at the foothills of Kraichgau: A unique fossile assemblage in the Reingraben near Karlsruhe. Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists 6:112

Prokofiev, A. M. 2012. Oligocene eel from the Frauenweiler site (Germany). Journal of Ichthyology 52(1):11-18

Wegner, T. 1917. Chelonia gwinneri Wegner from the Rupelton of Flörsheim a. M. Treatises of the Senckenbergische Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 354 : 361-372

#Rupelramphastoides#Rupelramphastoides knopfi#Barbet#Toucan#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Afroavian#Flying Friday#Frugivore#Eurasia#Paleogene#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Prehistoric Life#paleontology#prehistory#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wieslochia weissi

By Scott Reid

Etymology: From Wiesloch

First Described By: Mayr & Manegold, 2006

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Australaves, Psittacopasserae, Passeriformes

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 31 to 30 million years ago, in the Rupelian of the Oligocene

Wieslochia is known from the Bott-Eder Grube Unterfeld of Baden-Württemberg, Germany

Physical Description: Wieslochia is an extremely early species of proper passerine from Europe, and it doesn’t seem to have been any particular kind of perching bird, but an early member of the modern group. This is a very small bird, only about the size of a modern House Sparrow. It resembled, in many ways, the living Suboscine group - such as Tyrant Flycatchers - but it doesn’t seem to have been a member of that group proper, so its hard to discern appearance just from that. It had well developed shoulders, strong wings, and lightweight feet. It also had proper anisodactyl feet - three toes forward and one toe back - the mark of a modern perching bird; though its toes were quite short compared to some more derived songbirds. It also had a moderately sized, triangular beak.

Diet: With its triangular sharp beak, Wieslochia was probably mostly insectivorous, feeding on grubs and other soft animals by stabbing and grabbing with its jaws. It possibly also supplemented its diet with seed and fruit, like many mainly-insectivorous songbirds today.

Behavior: Wieslochia probably spent most of its time in the trees, like other perching birds, sticking to smaller branches and twigs for its perches with its shorter toes. It probably didn’t spend a lot of time on the ground, given its diminutive feet (and forested habitat). Wieslochia would have spent a lot of time digging around for grubs in the trees, probably also plucking off insects from the undersides of leaves. It is uncertain if Wieslochia was social or not, but it probably took care of its young in some fashion.

Ecosystem: Wieslochia lived in a diverse coastal area, filled with estuaries, streams and other bodies of water leading out into the ocean. An extremely lush habitat, there were many types of plants from algae to ferns and cycads, as well as conifers, palms, roses, asterids, beeches, birches, oaks, and cypresses. This coastal forest was very dense, transitioning into water-based plants and a possible mangrove forest. Dozens of fish lived here, including things like trumpetfish, eels, ladyfish, rockfish, and pipefish, though there are so many that it’s impossible to list them all. There were many kinds of insects for Wieslochia to feed on, including beetles, flies, butterflies, and other invertebrates like spiders. There were some mammals here too, such as the predatory Hyaenodont Apterodon, and sea cows and bats. Many dinosaurs were here too - the barbet Rupelramphastoides, a hummingbird Eurotrochilus, the buttonqail Turnipax, the tody Palaeotodus, the mousebird Oligocolius, the trogon Primotrogon, the loon Colymboides, and the seabird Rupelornis. This was a mixture of ocean-going and tree-dwelling birds, making it a diverse habitat to study the evolution of birds in the middle of the Cenozoic Era. That Hyaenodont would have been a real threat to these dinosaurs, but not one they couldn’t handle - being flighted and all.

Other: Wieslochia is a very uncertain sort of bird - while we know it’s in the group of modern perching birds, whether or not its a proper Songbird, or just outside that group or in the group of Tyrant-Flycatchers, or something else entirely, is a question. more fossils are necessary to answer it. What is known is that it’s the earliest record of modern perching birds in Europe, making it a notable find.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Frey, E., W. Munk, M. Böhme, M. Morlo, and M. Hensel. 2010. First creodont carnivore from the Rupelian Clays (Oligocene) of the Clay Pit Unterfeld at Rauenberg (Rhein-Neckar-Kreis, Baden-Württemberg): Apterodon rauenbergensis n.sp. Kaupia 17:103-113

Mayr, G. 2000. A new mousebird (Coliiformes: Coliidae) from the Oligocene of Germany. Journal of Ornithology 141(1):85-92

Mayr, G. 2004. Old World fossil record of modern-type hummingbirds. Science 304:861-864

Mayr, G. 2005. New trogons from the early Tertiary of Germany. Ibis 147(3):512-518

Mayr, G. 2005. A tiny barbet-like bird from the Lower Oligocene of Germany: the smallest species and earliest substantial fossil record of the Pici (Woopeckers and allies). The Auk 122 (4): 1055–1063.

Mayr, G. and A. Manegold. 2006. New specimens of the earliest European passeriform bird. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51(2):315-323.

Mayr, G., and C. W. Knopf. 2007. A stem lineage representative of buttonquails from the Lower Oligocene of Germany – fossil evidence for a charadriiform origin of the Turnicidae. Ibis

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Maxwell, E. E., S. Alexander, G. Bechly, K. Eck, E. Frey, K. Grimm, J. Kovar-Eder, G. Mayr, N. Micklich, M. Rasser, A. Roth-Nebelsick, R. B. Salvador, R. R. Schoch, G. Schweigert, W. Stinnesbeck, K. Wolf-Schwenninger, and R. Zeigler. 2016. The Rauenberg fossil Lagerstätte (Baden-Württemberg, Germany): A window into early Oligocene marine and coastal ecosystems of Central Europe. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 463:238-260

Micklich, N. R., J. C. Tyler, and G. D. Johnson, E., Swidnicka and A. F. Bannikov. 2009. First fossil records of the tholichthys larval stage of butterfly fishes (Perciformes, Chaetodontidae), from the Oligocene of Europe. Palaeontologische Zeitschrift 83:479-497

Micklich, N., and L. H. Hildebrandt. 2010. Emergency excavation in the Grube (Unterfeld) Frauenweiler clay pit (Oligocene Rupelian; Baden-Wurttemberg, S Germany): New records and palaeoenvironmental informatino. Kaupia 17:3-21

Micklich, N. 2011. Emergency excavation in the Grube Unterfeld (Frauenweiler) clay pit (Oligocene, Rupelian: Baden-Wurttemberg, S. Germany): New records and palaeoenvironmental information. European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists Program and Abstracts 9:42

Monninger, S., and E. Frey. 2008. Humming birds and sea cows at the foothills of Kraichgau: A unique fossile assemblage in the Reingraben near Karlsruhe. Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Palaeontologists 6:112

Prokofiev, A. M. 2012. Oligocene eel from the Frauenweiler site (Germany). Journal of Ichthyology 52(1):11-18

Wegner, T. 1917. Chelonia gwinneri Wegner from the Rupelton of Flörsheim a. M. Treatises of the Senckenbergische Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 354 : 361-372

#Wieslochia weissi#Wieslochia#Bird#Songbird#Dinosaur#Passeriform#Perching Bird#Palaeoblr#birblr#Factfile#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#Paleogene#Eurasia#Insectivore#Songbird Saturday & Sunday#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

104 notes

·

View notes