#Pablo Kjolseth

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Seven Reasons to Celebrate Lon Chaney by Pablo Kjolseth

As a Colorado native, I can say that Lon Chaney is a local hero. Born in 1883 on April 1 in Colorado Springs, he was the son of deaf mutes. It’s not an exaggeration to say that he gave his life to his craft, as he endured countless agonies that distorted and crippled his body in dangerous ways to achieve macabre, ghastly, haunting and grotesque effects that still astound to this day. Chaney got involved with the stage at the age of 11, working first as a prop hand, then comedian, dancer, actor, stage manager and even selling tickets at vaudeville houses around the Southwest. From 1913 through 1919, he found work in the movies, mainly as an extra. His work over the next two decades would go on to cement his status as one of cinema’s most iconic actors. If you had to give yourself one film a day over the course of one week to appreciate his genius, below are seven titles that celebrate the “Man of a Thousand Faces.”

Wallace Worsley’s THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME (’23) was Universal studio’s biggest money maker that year. Based on Victor Hugo’s tale, Chaney’s portrayal of Quasimodo would launch his career. Elaborately reconstructed Parisian street sets and big mob scenes all added to the excitement, but at the center was Chaney’s physical transformation assisted by a breastplate attached to shoulder-pads; a hump made of rubber weighing 70 pounds, which was attached to more pads in the back; and a light leather harness that connected the breastplate and shoulder-pads in such a way that Cheney was hobbled throughout and unable to stand erect. Add a skintight flesh-colored rubber suit, affixed with animal hair, mortician’s wax, fang-like teeth in a painful mouth device that kept him from closing his mouth and, voila, the master of disguises was ready to horrify a nation.

Between THE PHANTOM CARRIAGE (’21) and THE WIND (’28), to name two favorite films of mine, the amazing Victor Sjöström directed HE WHO GETS SLAPPED (’24). This was the first production for the newly formed MGM and is the first feature to use the roaring Leo the Lion logo. Anyone who has ever been humiliated by their peers will have lots to dig into here. Bonus: a young Norma Shearer.

Rupert Julian’s THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (’25) was based on a novel published in 1911 written by Gaston Leroux. Set in the Paris Opera House, which had been finished by 1879, Leroux claimed his novel was based on the true story of a ghost that inhabited the honeycombed corridors below the main stage. Leroux was a former theater critic, which made him well aware of the building’s history, including a fatal chandelier accident from 1896.

Before the controversy of FREAKS (’32) or his big success with DRACULA (’31), Tod Browning made two exceptional films starring Lon Chaney: THE UNHOLY THREE (’25) and LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT (’27). The former would be remade five years later as a “talkie” by director Jack Conway and also starred Chaney in what would be his only sound film as well as his last film. The latter would become one of the most celebrated lost films of all time. The last known copy of LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT was destroyed in a 1965 MGM vault fire. In 2002 a 47-minute-long reconstruction (22 minutes shy of the original 69-minute-long print) was put together using the original script and film stills. This is the version also available to FilmStruck viewers.

Given his early death and the lost films, it seems appropriate to end with one more tragic clown saga: Herbert Brenon’s LAUGH, CLOWN, LAUGH (’28). The original source material was a 1919 play by Fausto Maria called Ridi, Pagliaccio. LAUGH, CLOWN, LAUGH has been cited as Lon Chaney’s favorite role, and the song with the same name, which was often played to audiences before screenings of the movie, rose to the #1 spot on the 1928 hit parade and was played at his funeral.

#Lon Chaney#Laugh Clown Laugh#Phantom of Opera#London After Midnight#The Hunchback of Notre Dame#horror#man of a thousand faces#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Glimpse Into the Bergman Archives by Pablo Kjolseth

Taschen books are known for their "enormous formats that would crush most coffee tables to splinters," as Rebecca Mead points out in a New Yorker article on another printer (Gerhard Steidl). For film geeks such as myself, Taschen's enormous format is a plus as it mimics the joys of the big screen, albeit in book form. My first Taschen book was The Stanley Kubrick Archives and it's full of revealing interviews, blueprints for set designs, screenplays, essays and interesting ephemera. Taschen now has a new book out called The Ingmar Bergman Archives, and given how FilmStruck has 45 (!) Bergman titles currently available to view, I thought I'd delve into some Taschen excerpts on five titles that overlap with Max von Sydow.

THE SEVENTH SEAL ('57)

Commenting on the machinations of working with a film studio, Bergman swings around to focus on his aesthetics regarding camerawork with actors. Reading this excerpt brings to mind the iconic way Death (Bengt Ekerot) and The Knight (von Sydow) are framed by the seaside as they play their famous game of chess: "There are many directors who forget that our work in films begins with the human face. We certainly can become completely absorbed in the aesthetics of montage; we can bring together objects and still life into a wonderful rhythm; we can make nature studies of astounding beauty; but the approach to the human face is without doubt the distinguishing quality of the film."

THE MAGICIAN ('58, aka: THE FACE):

This story takes place in the mid-1800s and involves Albert Emanuel Vogler (Max von Sydow), a mesmerist and magician who is traveling to Stockholm with his troupe only to be placed under house arrest. Erland Josephson, who played the Consul Abraham Egerman, had this to say about the film: "In THE FACE, Ingmar (through von Sydow) was the magician and I was the representative of society scrutinizing people." Bergman had this to add: "Unfortunately, it's not so funny as I intended it to be. The actor who was the big comic role was so drunk all the time he couldn't remember his lines or what he had to do. So about a third of his part had to be cut, which meant that the film lost its balance and became too serious."

THE VIRGIN SPRING ('60):

With THE VIRGIN SPRING Bergman won the first of his Academy Awards in 1961 and later provided Wes Craven with inspiration for his gritty thriller LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT ('72). When Bergman was done filming THE VIRGIN SPRING, he felt good about himself. "I thought I'd made one of my best films. I was delighted, shaken. I enjoyed showing it to all sorts of people." But he would later belittle THE VIRGIN SPRING as "an aberration" and "a lousy imitation of (Akira) Kurosawa." His biggest grudge was feeling he'd allowed the film to be too sentimental.

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY ('61):

Karin (Harriet Andersson) is trying to recover from mental illness on a Baltic island. Along for the ride is her husband (von Sydow), young brother (Lars Passgård) and father (Gunnar Björnstrand). In a section titled "Invisible Shadows," cinematographer Sven Nykvist had this to say: "Ingmar's films radically changed in character, starting with THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY. To have been present throughout this process has been one of my most important experiences as a photographer. There is no doubt that working with Ingmar was an eye-opener, but I dare say that he in me found a tool and a twin soul, someone who thought about things the same way as he did. After completing the film, we both felt that we had to continue to work together."

WINTER LIGHT ('63):

The following message by Bergman was read on February 10th, 1963, at "a fundraising show in Falun for the benefit of Skattunge church" and the day before the films official premiere: "I once had a dream, or a vision, and I imagined that dream to be of importance to other people, so I wrote the manuscript and made the film. But it is not until the moment when my dream meets with your emotions and your minds that my shadows come to life."

#FilmStruck#Ingmar Bergman#Taschen#The Ingmar Bergman Archives#Max Von Sydow#The Seventh Seal#The Magician#The Virgin Spring#Through a Glass Darkly#Winter Light#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth

89 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Why This Dead End is Worth Your Time by Pablo Kjolseth

Director William Wyler's career spans the decades, starting with silent movies then transitioning to such hits of the later sound era such as THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES ('46), ROMAN HOLIDAY ('53), BEN-HUR ('59) and FUNNY GIRL ('68), to name but a few. Dig a bit earlier, however, and you'll find a gem like DEAD END ('37). It's a noir I feel some have passed over that resonates strongly with themes we see playing out in the headlines today, such as the huge gap between the haves and the have-nots.

The thrust of the plot for DEAD END has the gangster Baby Face Martin (Humphrey Bogart) revisiting his childhood slum in East Side Manhattan with his sidekick. Baby Face hopes to connect with his mom while also maybe rekindling an old romance, but as most of us know, you can never really go home again and that's certainly the case here. When Baby Face Martin tries to reconnect with his mom, she slaps him in the face and tells him, in so many words, how she wished she'd never given birth to him. When he tries to reconnect with his old girlfriend, he finds out that she is now a prostitute with syphilis. This puts him in a foul mood and makes him decide he should kidnap a rich kid from the area where the luxury towers meet the water and slums.

In Phil Hardy's The Overlook Film Encyclopedia for The Gangster Film, he refers to the pretense to Wyler's film as "impossibly phoney [sic]." He also slams the "all-too-obvious metaphor" of having penthouse terraces butting up against an "overhang of the waterfront slums," adding that the whole notion is a "clumsy contrivance," one that gives rise to "facile oppositions" and basically dismisses much of the movie as "superficial," naive, conventional and sentimental. He's clearly not a fan, and that's okay. Unlike Hardy, I am a fan and think this film is great.

DEAD END is based on a play by Sidney Kingsley. A play that Hardy says "passed as a triumph of realism on Broadway" but on film, Hardy can’t get past the artifice of the sets. Anyone who watches the movie can understand that, yes, the proceedings are clearly taking place on a set and it’s far from Italian neorealism (which this film predates by nearly a decade). The shots with the bridge in the background are clearly rear-projections. Even so, the stage and sets by Richard Day (nominated for a Best Art Direction Oscar) are awesome and clearly the work of stagehands and technicians who are working at the pinnacle of their craft and with full bravura. The city squalor is convincing; you see people living like sardines, real cockroaches and trash (Wyler used actual garbage) is everywhere. The work here calls to mind concepts written about in the book Celluloid Skylines: New York and the Movies by James Sanders.

On the heels of Reaganism, we had radical films such as John Carpenter's THEY LIVE (‘88) to discuss the discrepancy between rich and poor in the U.S. Now we have Boots Riley's SORRY TO BOTHER YOU (2018). Anyone who likes those two films should check out Wyler's DEAD END—never mind the noir elements, or the fact that this is one of Humphrey Bogart's big breaks, or whether it's too stagey or dramatic— if you focus on the fact that here is a film that shows dirt-poor people living under the shadow of extreme wealth, you'll be surprised at how relevant it feels today.

As to the cinematography, Gregg Toland picked up some wicked chops working for Karl Freund on MAD LOVE (’35). Freund, in turn, learned quite a bit as a cinematographer for Fritz Lang on METROPOLIS (’27). In DEAD END, you see Toland’s genius in synthesizing the traditions of his craft, which can also be seen later in THE GRAPES OF WRATH (’40) and CITIZEN KANE (’41). The dance between cinematography and set design is simply spectacular.

#FilmStruck#Claire Trevor#Gregg Toland#William Wyler#Dead End#Humphrey Bogart#Sylvia Sidney#Joel McCrea#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Cinephile’s Guide to Telluride by Pablo Kjolseth

This Labor Day Weekend the Telluride Film Festival turns 45. With over 3,000 film festivals to choose from worldwide, why choose a trip to Telluride? Here’s why:

It's a beautiful place. Telluride is a former silver mining camp located almost 9,000 feet up in elevation alongside the San Miguel River in the Western San Juan Mountains. You’ll be in a box canyon with breathtaking views. If you stand downtown on Colorado Avenue at dusk, you'll see amazing sunsets to the west and steep canyon walls with the postcard-perfect Bridal Veil Falls to the east. Of course, most of the time you’ll be inside a movie theater being transported who-knows-where. But in-between shows and while waiting in line, you can drink in the views.

It's a challenge. In a good way. Attending Sundance is easy as there are plenty of cheap flights into Salt Lake City and then Park City is only a half-hour drive away. Maybe that's why it gets mobbed by 40,000 people. Telluride? It has a tiny airport with tiny planes and what has to be one of the tiniest runways in the U.S. The bulk of people attending, therefore, drive seven or so hours to get there and this helps to separate the wheat from the chaff, with attendance being about a tenth of what Sundance supports.

It's selective. A Sundance or Toronto catalog looks and weighs as much as a phone book and you know what you’re getting into in advance. Which can be a good thing, in terms of giving you many options and choices. But a Telluride catalog is a slim booklet that fits in your back pocket, and people attending won't know what will be in that booklet until they are there, usually the night before the big communal feast on Friday where pass holders and filmmakers commingle and jockey for paper plates in the same buffet line. It's a blind date, one in which you are being asked to trust the movie curators. It’s like a restaurant with no online menu and a great chef who wants to surprise you with all manner of unusual food items that you’ve never tasted.

It celebrates the legacy of film. They show archive prints, silent films with live musical accompaniment and they screen 35mm prints too (although sometimes they don't print this information in their programs, a strange oversight). And, of course, they have the ever-popular world and U.S. premieres by well-known directors or new talented filmmakers about to make a big splash.

It has free events. In the daytime, panel discussions in the park. At night, open air screenings under the stars.

It has a great campground with showers and bathrooms that are only a ten-minute walk from downtown. Warning: show up early if you want a shot at a spot. Otherwise you’ll find yourself driving out of town along Last Dollar Road looking for a place to squat.

It usually has Werner Herzog in attendance. Unless Herzog is on location elsewhere shooting a movie, he'll probably be there to celebrate his birthday alongside screenings that take place in the huge theater named after him or in one of the half-dozen or so other theaters that are within walking distance of each other (the exception to this being the Chuck Jones Cinema in Mountain Village, accessible via a free but half-hour long gondola ride from downtown). Speaking of which:

It has incredible staff, tech crew and theaters. Each theater has a theme, be it the Chuck Jones Cinema or The Galaxy. These theaters are built by volunteers, staff and top-notch technical crewmembers, who all put their heart-and-soul into transforming what is normally a climbing gym or some other public use space into temporary, state-of-the-art dedicated film auditoriums with its own vibe and magic.

IIt has no paparazzi. No press screenings. No rubber-neckers or throngs of people crowding out the celebrities for selfies (okay, some of those). As a result, in Telluride you might find yourself buying a bagel behind Willem Dafoe or bumping shoulders with Danny Elfman. It has a casual vibe. It's not a zoo. It's not a circus. It's not a market. It's a film festival devoted to cinephiles and serious filmmakers, one that just happens to be taking place in a gorgeous mountain setting where you half expect Julie Andrews to break out into song.

It always has a Guest Director. Sometimes a well-known director (John Boorman), or musician (Laurie Anderson), or philosopher (Slavoj Zizek) or, as is the case this year, a novelist: Jonathan Lethem. This is one of my favorite sections because Telluride staff will bend over backwards to find six titles that have had a profound influence on the Guest Director’s life. The choices usually go back in time, swerve among genres and always include new discoveries. They also serve to showcase the power of cinema. This year that program is sponsored by FilmStruck, because we cinephiles have to stick together.

#FilmStruck#Telluride Film Festival#JR#Rosalie Varda#Gael García Bernal#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

5 Small Pleasures From MARS ATTACKS! by Pablo Kjolseth

There are many obvious reasons to see Tim Burton's MARS ATTACKS! ('96). The composer is his long-time collaborator and the one-time Oingo Boingo front-man, Danny Elfman. The cinematography is by David Cronenberg's go-to-camera guy Peter Suschitzky, The cast features off-the-charts star-power that includes Jack Nicholson, Glenn Close, Annette Bening, Pierce Brosnan, Danny DeVito, Martin Short, Sarah Jessica Parker, Michael J. Fox, Rod Steiger, Tom Jones and that's just a chronological reading from IMDB that doesn't even get to scenes with Pam Grier, or Jack Black! Bonus: the aliens blow up Congress.

But let’s not forget the smaller pleasures:

You get to see the real-life demolition of The Landmark, a casino once owned by Howard Hughes.

2.35:1 aspect ratio! The only other film Tim Burton has shot that also features this anamorphic ratio was PLANET OF THE APES (2001).

Space ship designs influenced by Fred F. Sears' EARTH VS. THE FLYING SAUCERS ('56).

The only time Tim Burton was contractually allowed (spoiler alert) to kill off Jack Nicholson's character. And he does it twice.

Martians influenced by Wally Wood. People like me, who grew up on EC Comics and Mad Magazine , are terribly fond of Wally, and he provided some of the original sketches for the 1962 Mars Attacks! trading cards put out by The Topps Company which inspired the movie.

On the aforementioned topic of the Topps trading cards, Alex Cox, of REPO MAN ('84) fame gave me the following insight back in 2011:

As a young boy, having read The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, and other great works, I also started chewing bubble gum. So it was natural that I would acquire a series of bubble-gum cards about the American Civil War, which were tremendously blood-thirsty and exciting, and also a series of bubble-gum cards about the Martian invasion of Earth in the late 50s, early 60s, which were titled Mars Attacks!

There were 52 units, maybe 53 including the last card, which was the index. It was about Martians in flying saucers that kind of related to the flying-saucer scare of the 1950′s. Martians in flying saucers attacked Earth using a variety of cruel devices including a giant robot, a freezing ray, a giant flame-thrower and everything else that you can imagine. For whatever reason, they weren’t killed by bugs or microbes. They were killed by a retaliatory attack. Somehow the Earth people or military forces had managed to hide themselves and create a rocket force to destroy the Martians on their home planet.

I brought this collection of bubble-gum cards to the attention of the Hollywood Studios and was involved, for a while, with John Davison, in a project called MARS ATTACKS! It was based on the bubble-gum cards, ending with the Earth’s retaliation against Mars. But the Earth’s expeditionary force got lost on Mars, could never find the capital city, and ultimately all died, killed by microbes in the alien environment. The film that I was planning was never made. But years later it was resurrected by Tim Burton, with the same casting director, Vicky Thomas, who at one point called me to ask if I’d owned the rights to the bubble-gum cards. But no one had ever secured the rights to the bubble-gum cards, so – unfortunately – I said I didn’t. At which point I never heard anything more.

But the Tim Burton film got made. The opening scene was the best, with the burning cattle. Even if you think of it; it’s impossible that cattle could catch on fire like that, burning for a period of time, but it was a great opening scene, and Vicky cast it, and – as far as I know – she also provided the “wee-ack-ack-ack-ack” Martian voices.

Vicky Thomas helped Cox cast REPO MAN, SID AND NANCY ('86) and WALKER ('87). Producer John Davison is known to most as the Executive Producer to ROBOCOP ('87) but he also helped Alex with HIGHWAY PATROLMAN ('91) and produced SEARCHERS 2.0 (2007). It would have been fun to see their version, but I can’t complain with Burton’s dark comedy, which is about as much dark fun as one can get away with when saddled with a PG-13 rating.

#FilmStruck#Mars Attacks!#Tim Burton#Jack Nicholson#Sylvia Sidney#Alex Cox#Vicky Thomas#Pablo Kjolseth#StreamLine Blog

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

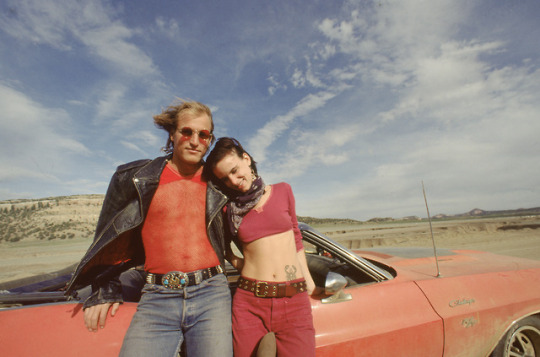

BONNIE AND CLYDE ('67), BADLANDS ('73) and NATURAL BORN KILLERS ('94) by Pablo Kjolseth

Guns. The U.S.A. owns almost half the guns in the world and we also lead in the manufacture and export of guns, making it no surprise that they're always in the news alongside all too familiar and tragic headlines. On the domestic end, it's usually a story about men and the relationships they cultivate with their guns. But it's not always that way. Sometimes a woman also gets involved, and it turns into a threesome of sorts. Such was the case when Charles Raymond Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate went on a murder spree in 1958 that killed 11 people. It was an event that was tackled in Terrence Malick's BADLANDS ('73) and then more loosely in Oliver Stone's NATURAL BORN KILLERS ('94). Before that, Bonnie Elizabeth Parker and Clyde Chestnut Barrow were two infamous lovers to make waves as robbers during the Great Depression. They killed at least nine police officers along with several civilians. Their story would be mythologized and transmuted into cinema by Arthur Penn's BONNIE AND CLYDE ('67).

Let's put these three movies up against the wall for a quick police lineup. Who was behind the camera? What made them stand out? How were they shot? First up:

BONNIE AND CLYDE

1) Arthur Penn directed. He followed BONNIE AND CLYDE with ALICE'S RESTAURANT ('69) and LITTLE BIG MAN ('70). BONNIE AND CLYDE was nominated for a slew of Oscars, including Best Director for Penn and winning two for Best Actress in a Supporting Role and Best Cinematography. The man behind the camera snagging that last award was Burnett Guffey, a seasoned veteran who got his start in 1923 and who also worked on FROM HERE TO ETERNITY ('53) and BIRDMAN OF ALCATRAZ ('62).

2) Before BONNIE AND CLYDE Arthur Penn had a flop with MICKEY ONE ('65), but that film starred Warren Beatty and Beatty liked Penn. Beatty was instrumental in hiring Penn and Robert Towne for the script. To quote from Alex Cox's book Introduction to Film: A Director's Perspective, there was something else: "As a producer and as an actor, Beatty's work in this instance was quite brilliant: in particular, his ability to surrender focus to his co-star, Fay Dunaway, whose performance dominates the film. Who was the auteur of Bonnie's tale - Arthur Penn, or Warren Beatty?"

3) As to how it was shot, what really set BONNIE AND CLYDE apart from the competition was the slow-motion carnage at the end. This connected with a wide audience for many reasons, including that the film emphasized the protagonists as individuals fighting authority and banks. At the time of the movie's release, the carnage in Vietnam served as a backdrop that further undermine the powers that be. As to influence, it's hard to imagine the slow-motion bullet ballad of Sam Peckinpah's THE WILD BUNCH ('69), which came out two years later, without BONNIE AND CLYDE.

BADLANDS

1) Terrence Malick's directorial debut was a doozy. It was not the first film to be based on Starkweather and Fugate, for that we could look to James Landis' THE SADIST ('63). It was, however, the first film to be distributed by a mainstream studio to do so and was followed by several others. BADLANDS was picked up by Warner Bros. after it screened at the New York Film Festival, alongside Martin Scorsese's MEAN STREETS ('73).

2) Some of the things that make BADLANDS stand out are his iconic use of American landscapes, the use of Sissy Spacek's voice to provide narration, and (like BONNIE AND CLYDE) the male substitution of violence for sex.

3) In his article on TCM, Jeff Stafford had this to say about how BADLANDS: "Although he had previously worked as a screenwriter (POCKET MONEY), he decided to direct his own scripts after Paramount made a complete mess of his DEADHEAD MILES screenplay, transforming it into a film so bad it couldn't even be released. With his brother Chris, Malick managed to raise $300,000 for BADLANDS's pre-production costs. The additional money was raised by independent producer Edward R. Pressman from personal friends like former Xerox chief Max Palevsky".

NATURAL BORN KILLERS

1) In what would be another Warner Bros. property, director Oliver Stone would take a story by Quentin Tarantino that he then took over to co-write (alongside David Veloz and Richard Rutowski) into a nightmarish vision of mass murder flying in tandem with mass media.

2) NATURAL BORN KILLERS would employ 18 different film formats. Whereas BONNIE AND CLYDE was shot in a slightly traditional way until an untraditional end, and BADLANDS was shot lyrically, with N.B.K. we have a Cuisinart-style mode that batters viewers with a frenzy of hyper-stimulation the likes of which might induce seizures in those with weaker immune systems.

3) NATURAL BORN KILLERS was shot in 56 days. Nine Inch Nails front man Trent Reznor produced the soundtrack. Like Kubrick's A CLOCKWORK ORANGE ('71), it's a film so agitated and manic that some have accused it of playing a pivotal role in pushing impressionable people into committing acts of violence themselves, as happened when 18-year-olds Sarah Edmondson and Benjamin Darras dropped acid, watched N.B.K. and later that night shot two people (one fatally, one left paralyzed).

There are many debates over what begets violence. The three pictures mentioned above all touch, in different ways, on our country’s obsession with guns and violence but when the camera is shooting a story, even when it’s based on a true story, it’s turning things around. It’s turning that story into a conversation among the viewers. It’s a dialogue. This is a conversation we own. We are both the owners and participants in this hall of mirrors. A hall of mirrors that too often comes crashing down in gunfire.

If I can add but one thought to this conversation let it be this: if you feel compelled to drop acid and watch a movie, please consider Disney's FANTASIA ('40). That’s what I did as a teenager. It still turned into a bad trip but – other than an unknown amount of lost brain cells for the user in question – nothing was harmed.

153 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Life Under Nazi Occupation by Pablo Kjolseth

I can’t imagine what it would be like to try writing a script while Nazi’s occupied my city. But that’s what Roberto Rossellini did, along with his co-writers Sergio Amidei, Federico Fellini and Alberto Consiglio for ROME, OPEN CITY (’45). A scant few months after the June 4, 1944 liberation of Rome, he managed to launch the production by scrounging money, electricity and film by any means possible. The dubious quality of the scraps of film they were able to procure added grain and different exposure speeds to the mix. When they couldn’t get film or money, work came to stop. Despite several gaps in shooting, all that was done between January and June of 1945 finally resulted in a finished piece – one too raw for the distributor who had originally offered up a minimum guarantee for its completion. Instead, the contract was declared null and void because the distributor claimed that what Rossellini had delivered to him was not a film.

Heavily in debt, Rossellini was fortunate enough to eventually find a buyer and ROME, OPEN CITY was screened at the first Cannes Film Festival during a 3:00pm slot where Rossellini claims “I may have been the only one in the audience.” But then later in Paris, then Italy, then the U.S., his movie not only met with success, it established neorealism as the most important and influential style of the postwar era. It put Rossellini in the global spotlight and launched his career.

ROME, OPEN CITY was not the first neorealist film, as that honor goes to D.W. Griffith’s ISN’T LIFE WONDERFUL (’24), which was shot on the streets of Germany with many non-professionals and during a time of “disastrous postwar hyperinflation (where a bushel of banknotes might buy a loaf of bread; the exchange rate in 1923 rose to 4.2 trillion marks per dollar)” (A Short History of the Movies). But ROME, OPEN CITY certainly caused such a big splash that,

Open City became the unofficial cornerstone of a new movement in Italian cinema – Neorealism, a “new realism” characterized by the use of nonprofessional actors and realistic dialogue, an emphasis on the everyday struggles of common people and the unvarnished look of non-studio reality, and the determination to present the characters in relation to their real social environments and political and economic conditions. (Ibid.)

The title was originally going to be A STORY OF YESTERDAY, then CLOSED CITY, but “Open City” was a military term referring to cities that were to be spared air raids, bombings and combat due to important or revered sites. A factor that should have spared the site of St. Peter’s Basilica and the Sistine Chapel, but Rome was bombed and the destruction of these attacks is clearly on display in the destroyed buildings that can be seen in the background of the film. The other notion behind “open” is that it denotes freedom – as in freedom to shoot a film outdoors and wherever you want, as well as a city open to the future with hope for children (Rossellini loved children).

In telling the story of Nazi occupied Rome, one where Romans deal with curfews, food rations and Nazi’s who use torture on anyone involved with the resistance, Rossellini did use some professional actors. Aldo Fabrizi, who plays the priest Don Pietro Pellegrini, was cast against type (his previous work was mostly in comedies). Fellini brokered the deal by convincing Fabrizi to take the role for a pittance of what he normally commanded. Anna Magnani was previously known to Italian audiences for her roles in “White Telephone” pictures (these being escapist movies that take place in fancy apartments decorated with white telephones which were quite the luxury at the time).

In ROME, OPEN CITY, her performance as Pina, a widowed and pregnant mother about to marry her atheist neighbor, was such an electrifying performance it completely re-branded her. One moment, she was known in Italy as someone who played small parts such as singers and vaudeville performers, the next she became the face of fierce resistance in the fight against fascism. She and Rossellini would later become famous lovers, albeit that relationship was later eclipsed by the drama that was the romance between Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman (and thank goodness for that one, as it gave Isabella Rossellini to the world).

Before ROME, OPEN CITY, Rossellini had directed three propaganda films. His decision to give voice to the Italian Resistance was a transformative one. “After all we’d seen and been through, the destruction of war, we couldn’t afford the luxury of making up fictional stories.” This drive for authenticity respected the geography of the city. It’s opening shot and closing shot both show us the dome of St. Peter’s as the center of Rome, but the opening shot is from around the Piazza di Spagna whereas the closing shot is filmed from the opposite side of the city – thus forming two semicircles to complete the circle.

There is also something in the idea of an Italian film showing us a priest and a communist, who traditionally were seen as being in opposite camps, here coming together as cinematic equals. To give Rossellini the last word: “Yes, it is necessary for the cinema to teach men to know themselves, to recognize themselves in others instead of always telling the same stories.”

#FilmStruck#Roberto Rossellini#Rome Open City#Anna Magnani#Criterion Collection#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth#Italian neorealism#Italian Cinema

107 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Must-Watch Title for Jim Thompson Fans by Pablo Kjolseth

Where the Holy Heck has this movie been all my life? Seriously, Alain Corneau’s SÉRIE NOIRE (’79) is a bit of a mind-blower.

The film first came to my attention last August when a 35mm English subtitled print was doing the rounds and screening at the Metrograph, Cinefamily and the Chicago Film Society. Amélie Garin-Davet, the Film Program Officer at the New York office for the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, sent out an email to film programmers that might be interested to let them know that they could screen the imported film print if they cleared rights with Rialto Pictures. Sadly, my fall calendar was already set in stone and I passed up this singular opportunity. I really wanted to see it though, so shortly thereafter I made a compulsive Blu-ray purchase online without realizing the disc would not play on my Region 1 player. All the promised bonus features remain tantalizingly out of reach, and probably in French only with no subtitles. Alas.

Five months later and here is SÉRIE NOIRE again, this time available to all FilmStruck viewers as part of "The Life of a Salesman" series. It is unlike any other Jim Thompson adaptation I've ever seen and I strongly recommended it to any lover of raw and unpredictable performances, as well as to lovers of rich 1970s cinema the likes of which doesn't shy away from daily squalor or unique madness. If you are reading this and are a fan of Jerry Schatzberg’s SCARECROW (’73) starring Gene Hackman and Al Pacino, I’m talking to you. SÉRIE NOIRE mines that same pulsing vein, albeit with a bloodier and murderous edge, one that shows far more naked greed and desperation.

SÉRIE NOIRE was nominated for a Palme d'Or at Cannes and a César for Best Screenplay. A few years later Corneau would sweep up several César awards with TOUS LES MATINS DU MONDE (aka: ALL THE MORNINGS OF THE WORLD, ’91), starring Gérard Depardieu. Corneau (1943 - 2010) got his start as an assistant to Costa-Gavras and his last film, LOVE CRIME (’10) would later be remade by Brian De Palma as PASSION (’12). With almost 20 directorial features to his credit, I look forward to acquainting myself with his work.

His lead actor in SÉRIE NOIRE, Patrick Dewaere, first made an impression on me in GOING PLACES (’74), a film by Bertrand Blier in which the characters played by Dwaere and Depardieu are misanthropic thugs aimlessly traversing a landscape of victims in an assault on all things bourgeois. In SÉRIE NOIRE, Dewaere really took me by surprise in his ability to chart an extremely erratic emotional spectrum that ranged from unexpected tenderness to horrific rage. That he should die at his own hands in July of 1982 by shooting himself with a rifle at the age of 35, and this shortly after the release of a film in which his character commits suicide (PARADIS POUR TOUS [’82]), leaves us with a sad coda for that which might have otherwise been a very long and promising career.

The template for SÉRIE NOIRE is A Hell of a Woman, a 1954 novel by Jim Thompson. In that novel, the protagonist, Frank, has a job working collections for Pay-E-Zee Stores, a job that occasionally takes him door-to-door. He hates his life, wife, job and definitely hates the bills he can barely pay at the end of every month. Then he meets Mona, a beautiful girl being pimped out by an unscrupulous aunt. The film adaptation of Thompson's work here was done by both Corneau and Georges Perec, who was an award-winning French writer whose life would be cut short by heavy smoking (he died of lung cancer when he was only 45-years-old).

There are many moments in SÉRIE NOIRE that took me by complete surprise. It’d be a crime to list them all and, instead, I will limit myself here to three. One, the image of Dewaere sinking himself naked into a tub full of water with eyes and mouth wide open until he almost drowns himself. Two, a clumsily executed murder in which a towel is wrapped around the muzzle of a gun to act as a poor-man's silencer only to catch on fire once the bullet is discharged. Three, Dewaere prancing maniacally around in a suit coat his wife had previously stripped to ribbons. These are only some of many indelible images.

I don't know that Jim Thompson could have foreseen how these moments would have necessarily translated to the screen, but I do feel confident that had he lived just a couple more years to see SÉRIE NOIRE, he would have approved of the artful and unpredictable execution with which the filmmakers did their job.

#FilmStruck#Jim Thompson#Série noire#Neo Noir#Alain Corneau#French Cinema#Patrick Dewaere#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

George A. Romero’s Favorite Film of All Time is a Romantic Opera by Pablo Kjolseth

It's not entirely incongruous that George A. Romero, known to many for his walking dead creations, would cite THE TALES OF HOFFMANN (’51) as his favorite film of all time. After all, THE TALES OF HOFFMANN does feature one rather stunning scene wherein a woman reveals herself to be a mechanical wind-up toy only after she/it is taken apart limb from limb - leaving only a blinking head on the floor. Obviously, there's much more to the moment than meets the eye and Romero is surely responding to the overall passion and showmanship that spin throughout the movie - a movie that has inspired plenty of other filmmakers, such as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, who uses a clip from THE TALES OF HOFFMANN and evokes the story of the living doll torn to pieces in his film TETRO (’09).

Even if you’re not an opera fan all that is required to enjoy Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s THE TALES OF HOFFMANN is an appreciation for the fantastic and magical realms created by Georges Méliès and Dr. Seuss. The theatrical interiors and landscapes are out of this world. Shot in dazzling Technicolor and featuring amazing production and costume designs by Hein Heckroth (who was nominated for two Academy Awards for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration and Best Costume Design), THE TALES OF HOFFMANN sings and dances its way from one romantic fable to the next with surrealistic aplomb. The film itself was a winner at Berlin, where it won for Best Musical, and at Cannes, picking up a Special Award “For the transposition of a musical work into a film.”

The musical work in question is Jacques Offenbach’s (1819 - 1880) opéra fantastique of the same name and is based on the highly fictional short stories of author E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776 - 1822). Hoffmann also authored The Nutcracker and the Mouse King (which in turn formed the basis for Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker ballet). With ballet in mind, viewers familiar with the work of The Archers (Powell and Pressburger’s Archers Film Productions, formed in 1943) might now recall the ballet sequence of THE RED SHOES (’48), based on a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. That was a precursor to Powell’s goal to marry filmed images to operatic music, which found its full form in THE TALES OF HOFFMANN. And speaking of this marriage, if you’d like a crash course in how to edit a movie to music, here’s a good place to start because the entire opera soundtrack for THE TALES OF HOFFMANN was pre-recorded and then the film was edited to the rhythm and tempo of the music.

The film appropriately starts with a prologue that shows Hoffman raptly watching a ballet performance by Stella. Stella wants to meet Hoffman after the show and sends him a note. The message is never delivered because it is intercepted by a rival. Hoffmann then leaves dejected and heads off to the tavern where he proceeds to get blitzed as he reminisces about three past loves. Primary colors highlight each tale. Yellow for the first, red for the second and blue for the third. We also move, respectively, from Paris to Venice, and then Greece, each exotic locale showcasing stunning set designs. In writing about Michael Powell in his A Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson recalls a man who spent time as director emeritus with Coppola's American Zoetrope and someone who was a “treasured Merlin at the court of Scorsese,” invoking also “his marriage to the editor, Thelma Schoonmaker” and finishes by saying: “I do not invoke the figure of Merlin lightly: Powell was English but Celtic, sublime yet devious, magical in the resolute certainty that imagination rules.”

I mentioned Méliès and Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel) earlier on, who I also consider magicians. The latter was a German-American artist whose life-line (1904 - 1991) closely mirrored those of Powell (1905 - 1990) and Pressburger (1902 - 1988). The only feature film Geisel ever wrote was a musical fantasy called THE 5,000 FINGERS OF DR. T (’53), directed by Roy Rowland (Stanley Kramer also, uncredited). The two films will forever be linked together in my mind because I was only seven-years-old when I first saw stills from both movies sharing the same page of David Annan's book Cinefantastic: Beyond the Dream Machine, and in which he writes: “The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is the best fantasy musical yet made, just as The Tales of Hoffmann brought the chilling fairy stories of childhood best to the screen in the form of a ballet.”

#The Tales of Hoffman#FilmStruck#Michael Powell#Emeric Pressburger#George A. Romero#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE GRIFTERS (’90) by Pablo Kjolseth

Anjelica Huston won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in PRIZZI’S HONOR (‘85), but in my book her performance in THE GRIFTERS (‘90) – for which she received a Best Actress nomination – is the one that should also have taken home the gold. She lost it to Kathy Bates for her role in Rob Reiner’s MISERY (’90), which was admittedly a tour de force. Let’s just say it should have been a tie and agree that it was a hell of a year for the femme fatale.

As recently as five years ago, Huston described her performance as Lilly Dillon in THE GRIFTERS as the most challenging role of her career. Given the bleak and harrowing narrative curve of the film it’s easy to see why. Any film based on a book by Jim Thompson, who is famous for chronicling the lives of losers and psychopaths with nihilistic aplomb, is bound to deliver on grim gut punches that spare no prisoners and provide cautionary tales that are not for the faint of heart.

In the case of THE GRIFTERS, the tragedy that Jim Thompson unravels combines obsession with money on par with something out of GREED (‘24) as he fuses them with family dynamics that carry that horrible unease you get from reading a play by Sophocles. Tossing a love triangle into the mix in no way ameliorates the feeling that disaster is inevitable.

The two other corners of the triangle are John Cusack, playing the part of Lilly’s son, Roy, and Annette Bening as Roy’s new girlfriend Myra Langtry. Threesomes always get sticky, but when all the players involved are con artists you can count on it getting overly complicated and maybe even a little bloody.

Cusack, still in his early twenties and still freshly known to most filmgoers as Lloyd Dobler in SAY ANYTHING (‘89) successfully brings real pathos to the table. It was a good career choice that announced his range could go far afield from a John Hughes comedy. It probably helped that Cusack was a huge Jim Thompson fan. As vulnerable as Cusack’s performance is, it’s Annette Bening who bares all in completely fearless fashion. BUGSY (‘91) would follow the year after and make a mark, but for me that mark starts here.

Stephen Frears was an interesting choice to direct. The studios originally wanted Martin Scorsese to do the job but Scorsese ended up being the producer of the film instead. Frears had proven himself with quality social dramas and arthouse hits, such as MY BEAUTIFUL LAUNDRETTE (‘85) and SAMMY AND ROSIE GET LAID (‘87), but it was probably the box office success of DANGEROUS LIAISONS (‘88) that landed him the job. After all, DANGEROUS LIAISONS also had two women and one man caught in erotic webs of intrigue and duplicity.

As to the genesis of the project, I reached out to Bruce Kawin who gets special thanks in the end credits. I took classes from Kawin when I was a student at C.U. Boulder and remember him using THE GRIFTERS in his screenwriting class. Here’s what he had to say about how he got the ball rolling:

When I was at Bob Harris’s Images Film Archive looking for stills to illustrate my textbook How Movies Work, Bob asked me if I knew any relatively unknown novelist whose books would make good movies. I told him about Jim Thompson and suggested three of his novels, including The Grifters. Bob and his partner, Jim Painten, decided on The Grifters and helped me as I wrote the first draft of the script. We took this script to Martin Scorsese, who made many suggestions for the rewrite. I took his advice when I rewrote the script, and that became the official first draft. Marty produced, working with Bob and Jim. Eventually Marty chose Stephen Frears to direct the picture, and Frears decided he needed an American noir novelist to write the shooting script; he chose Donald Westlake. Westlake got exclusive screen credit for the script, which was nominated for an Academy Award. Marty thanked me for bringing the novel to his attention and said he’d be glad to listen to any further suggestions I had about novels to adapt; I received a screen credit thanking me for my contributions to the project.

I’d like to give special thanks to Bruce Kawin for many reasons, but one of those would be that it was because of him that I got into Jim Thompson’s novels back when I was a student in college. Whether you read Thompson’s books or see movie adaptations of his work, he provides a white-knuckle ride through the underbelly of society that you won’t soon forget.

#Noirvember#FilmStruck#Stephen Frears#John Cusack#The Grifters#Annette Bening#Anjelica Huston#Bruce Kawain#Pablo Kjolseth#StreamLine Blog

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Unleashed Genius of Hendrix by Pablo Kjolseth

For three days in mid-June of 1967 a concert was put on at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in Monterey, California. John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas, along with a handful of other key people, slapped it together in only seven weeks. Tickets were three to six bucks with proceeds going to charity and performers playing for free (except Ravi Shankar who had been booked far in advance and before it became a charity event). Attendance would end up surging well past the fairgrounds approved capacity of 7,000 people. It was a huge success and attendance was secondary to that success. The real game changer was the music. Every music festival has its stars, but at this particular festival there was one star that shone brighter than the rest.

Over 30 bands would play that show, each memorable in their own unique way, but the real barn-burner was the last night’s penultimate performance by three relative newcomers known as The Jimi Hendrix Experience. Paul McCartney had suggested they be added to the lineup after hearing Hendrix’s cover of the song “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” Hendrix had mastered and utterly transformed a complicated Beatles tune a scant few days after the title track’s release. McCartney heard Hendrix’s cover and was more than impressed. Timing is everything. Had McCartney heard Hendrix a bit sooner, perhaps Hendrix would have been one of the many iconic people gracing the cover of the Sgt. Peppers album itself.

What happened that night in Monterey 50 years ago changed the history of music and launched Hendrix into the stratosphere. There to capture it was documentary filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker and his team working with some glorious Eastman Kodak high-speed 100 ASA Ektachrome film stock that would end up being replete with the occasional hippie-hair popping up every now and then in the camera gate. I normally shun reaction-shots of the crowd, but in this particular case the stunned look of the audience trying to absorb the sight of a guitar virtuoso on acid who makes love to his guitar (with arms, fingers, tongue, teeth, hips) and then sets the whole damn thing on fire really sums up the vibe. Talk about shock and awe.

Due to technical glitches, there were two songs that were only caught on audio and were not caught visibly by the camera. Those were “Can You See Me” and “Purple Haze.” To work around this, viewers of JIMI PLAYS MONTEREY (’86) will hear “Can You See Me” during the opening segment that shows us an artist (Denny Dent) stumbling across paints in a New York City alley near joints where Jimi got his start. As the song plays Dent splashes color on the grim and darkened wall, his work slowly revealing the face of Hendrix in a blossom of colors. As a bookend to this, an excerpt of “Purple Haze” gets splashed across the end credits.

Between those two events we go into a brief narration by “Papa” John Phillips that accompanies B&W pics that give context to Hendrix and his roots. This leads to a secondary intro, this time to the concert itself, wherein the “Monterey” song by Eric Burdon and The Animals sums up some of the bands who played the festival while we watch a parade of hippies and Hells Angels walk into the fairground while the various bands play on. As is noted on the commentary track, this “let’s start off a doc about a music festival by showing us the colorful customers first and then diving into the show” is not a cliché at this point in time but rather it is groundbreaking. Why? Because this is where many people first saw the wave of the hippies to come.

Then comes the concert footage that is rapturous to behold with each scene of Hendrix speaking volumes. “Now here is an act of major audacity,” says Charles Shaar Murray (author of Crosstown Traffic: Jimi Hendrix and Post-war Pop) on the commentary track. “Here he is staking the most enormous claim. He is basically announcing his intention to take over rock ‘n’ roll and place himself at its center… He’s done Howling Wolf, he’s nailed doing Dylan, he’s taken Dylan’s signature song and he’s making it his own, an act of tremendous cultural audacity. And he pulls it off perfectly.”

Anyone watching it now should agree that what Hendrix pulls off is worthy of a standing ovation (again, keep in mind he’s off his gourd on acid – which might make some call “foul” on doping charges, but still…). His bravura is unmatched.

Let’s also give kudos to the filmmaking team for being so present at a crucial time. The cameras do an exceptional job of getting close enough to Jimi that you can actually see him playing the guitar with his teeth. The director, Pennebaker, would go on to meet and later marry filmmaker Chris Hegedus after they both worked on TOWN BLOODY HALL (’71) – a documentary about the debate between Norman Mailer and Jacqueline Ceballos, Germaine Greer, Jill Johnston and Diana Trilling. The two filmmakers would make many more documentaries together, including another concert stand-out with David Bowie, ZIGGY STARDUST AND THE SPIDERS FROM MARS (’73), as well as a political documentary that would go on to receive an Academy Award nomination with THE WAR ROOM (’93). But it is their 50-minute documentary on the Jimi Hendrix Experience that I am recommending here. It is an experience few concert films can rival.

#D.A. Pennebaker#Jimi Plays Monterey#Jimi Hendrix#FilmStruck#Criterion Collection#Criterion Channel#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jungle Madness by Pablo Kjolseth

I had the honor of hosting Werner Herzog for a dinner back in 1999. Prior to his visit, I had hunted down an out-of-print first edition autobiography by Klaus Kinski entitled Kinski Uncut The book goes into eye-raising details that are by turn boastful, salacious and extremely lewd. Kinski traipses from one sexual conquest to another while undercutting many of the famous directors he's worked with along the way - including Herzog. At the sight of my hardcover edition, Herzog's eyes lit up as he exclaimed: "Oh, what marvelous lies!" Herzog then also recalled how Kinski had called him up prior to its publication and said something along the lines of how he had made up a bunch of horrible things about Herzog because he thought that would help sales.

Kinski Uncut is many things, but it's never boring. Here's a taste of how Kinski describes Herzog: "In any case, he's still sporting those unwashed, sweat-stained, fart-soaked rags - and he's just as unwashed as ever. And his teeth are as rotten as ever. And he's just as recalcitrant and he still stuffs his face like the garbage can he is - without ever picking up the check."

Herzog got his revenge on Kinski with the release of his documentary MY BEST FIEND ('99), which was released eight years after Kinski's death and gives Herzog the last word on their mutual love-hate relationship. Actually, Herzog doubles-down on getting the last word because ten years after MY BEST FIEND he went on to publish Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the making of Fitzcarraldo. In this book he revisits the journals he kept while shooting FITZCARRALDO (’82). He describes this book as "inner landscapes born of the delirium of the jungle." A clear taste of that delirium can be had from an excerpt from his journal marked down as "Iquitos - Camisea, 23 May 1984":

Kinski looked at the site and announced that my plan was completely impossible, prompted by madness. He is becoming the epicenter of discouragement. On closer inspection it became clear to me that no one is on my side anymore, not a single person, none, no one, not a single one. In the midst of hundreds of Indian extras, dozens of forest workers, boatmen, kitchen personnel, the technical team, and the actors, solitude flailed at me like a huge enraged animal. But I saw something the others did not see.

That "something" was a monumental movie about the title character’s quest to build an opera house in the middle of the jungle, a film that would go on to win the Palme d'Or award at the Cannes Film Festival along with many other accolades.

FilmStruck is streaming seven titles as part of its “Herzog & Kinski” theme, including Les Blank's BURDEN OF DREAMS ('82) about the making of FITZCARRALDO. Les Blank and Werner Herzog shared unique bonds. I met Les Blank when I screened what would end up being his last documentary: ALL IN THIS TEA ('07). This happened on the same night I met Charlie Kaufman for the first time (that being a longer story for another time). Blank was a much gentler soul than Klaus Kinski (or Kaufman, for that matter), but he was also a hell of a storyteller and he deserves to have his own words heard on his time with Herzog before and after FITZCARRALDO.

With this in mind, I now reach for my bookshelf Burden of Dreams: Screenplay, Journals, Reviews, Photographs edited by Les Blank and James Bogan. The following two paragraphs are written by Les Blank as part of his intro ("The Genesis of Burden of Dreams"):

In 1979, Werner convinced the program committee of the Hamburg Film Festival to invite me over to present a retrospective of my films. Here, I firmed up details with Walter Saxer, the producer of all but one of Herzog's films. I was to come down in October of that year and film preparations for the Fitzcarraldo production. The general plan would be for me to make the film as I saw it, but if it proved detrimental to the success of Fitzcarraldo's release, I would agree to postpone my release until a year later. Jose Koechlin von Stein, a Peruvian who had loaned Herzog the money to complete the filming of Aguirre, The Wrath of God, was to arrange financing with the help of West German television.

When I arrived in Munich, I spent a night at the apartment of Werner's half-sister, who took me on a fascinating tour of Munich's famous beerhalls. And I thought I was a beer drinker! These people are something else... the more dedicated swilling it down from liter-sized mugs in between puking on their feet and pissing in their pants. The following morning, I met Werner at the train station where an entire section of the Hamburg-bound train was reserved for the Munich-based film community. During the trip Werner introduced me to his countrymen and women, always insisting that I show the tattoo on my arm of two death-head masks, one laughing, one crying. They are attached by ribbons in the New Orleans Mardi Gras colors of green, purple and gold. I received it from San Francisco's Ed Hardy while making a film with Bruce 'Pacho' Lane on the great American carnival tattoo artist, Stoney St. Clair. When Werner had first seen mine, he immediately went to Ed Hardy to get tattooed with a skeleton dressed in a tuxedo and singing into an old-fashioned microphone. He proudly exhibited his tattoo, after he showed his friends mine and said, “See, this one is better.” His is a good tattoo, and may be better by some standards of tattoo judgement, but having marked myself for life, and having it called inferior, I found myself quietly cursing the Aryan arrogance of my boisterous benefactor. In Hamburg the train was met by a brass band and fire swallowers. The mayor threw a gigantic party and I decided I liked the Germans. Strange as they are, I seemed to get along with them and they seemed highly appreciative of the eight or nine films that I showed. At Werner's press conference I began to get a taste of the anti-Herzog element. He was viciously attacked for exploiting the indigenous people of Peru; and while he had explanations of rumors such as forcing Indians to work at gunpoint, I began to wonder uneasily how innocent he really was.

Blank and Herzog had met many times while attending the Telluride Film Festival. Herzog himself tends to premiere many (but not all) of his films at that prestigious film festival which also, coincidentally, overlaps with Herzog's birthday (T.F.F. always occurs over Labor Day Weekend, Herzog's birthday is September 5th).

In 2007 Blank would receive the Edward MacDowell Medal for "outstanding contributions to the arts." Previous winners had included only two other film directors: Stan Brakhage and Chuck Jones. Chairmen of the jury included Taylor Hackford, Ken Burns, Steven Soderbergh, Mira Nair, Spike Jonze, and T.F.F. founder, Thomas Luddy.

Luddy, quoted in a New York Times obituary for Blank, said: "...Les Blank's films will be revered as time-capsule classics. I said 'Amen,' as did all the other members of the committee. We never even discussed another name, and our meeting was over in less than an hour."

Herzog's FITZCARRALDO is a monumental achievement. So is Blank's BURDEN OF DREAMS. It really doesn't matter what order you see them in, as long as you see them both.

#FilmStruck#Werner Herzog#Burden of Dreams#Klaus Kinski#Fitzcarraldo#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth#Les Blank#Kinski Uncut

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bogdanovich In The 70s by Pablo Kjolseth

It’s strange for me to think that most people today might recognize Peter Bogdanovich more for his TV credit as Dr. Elliot Kupferberg from The Sopranos than as the director of THE LAST PICTURE SHOW (‘71). Be that as it may, Bogdanovich has worn many hats and done plenty of work to serve the moving arts. First and foremost he was a true cinephile, devouring up to 400 movies in his youth and keeping a card file on each film he screened over the span of almost two decades. Then, by turns, he became a film programmer at MoMA in New York City, a film critic for Esquire, a film director, a film scholar, as well as a film actor.

Bogdanovich’s big break into the film industry was like something out of the movies. Scene: the young film geek is at a movie premiere in L.A. and strikes up a conversation with the man behind him, Roger Corman. Corman mentions that he liked a piece the young film geek wrote for Esquire and offers him a job working at his company American International Pictures. This leads to a variety of uncredited jobs on Corman’s THE WILD ANGELS (’66), THE TRIP (’67), and finally a chance to helm (under the pseudonym of Derek Thomas) VOYAGE TO THE PLANET OF PREHISTORIC WOMEN (’68). Corman then affords Bogdanovich the chance to direct Boris Karloff in TARGETS (’68) – and with that the aspiring young film geek graduates summa cum laude from the school of A.I.P.

A return to journalism gives Bogdanovich a chance to interview one of his heroes, Orson Welles, while on the set of Mike Nichols’ CATCH-22 (’70). It would be the beginning of a life-long friendship that would see the two directors also turn into house-mates as Bogdanovich would allow Welles—who was going through a financial rough patch—to stay at his Bel Air mansion for a couple years. Again, it’s a scenario that seems to come straight out of the movies, or maybe TV. At a past Telluride Film Festival, Bogdanovich recalled how surreal it was to wake up in the middle of the night and see the great Welles standing there in his kitchen, in pajamas and a bathrobe, rummaging through his freezer to raid the ice cream.

The early ‘70s must have seemed like a fantastic dream to Bogdanovich. He had Welles living in his house, the American Film Institute commissioned him to do a tribute to another one of his heroes, John Ford, called DIRECTED BY JOHN FORD (’71) and then at the age of 32 he directed THE LAST PICTURE SHOW, which was nominated for eight Academy Awards. The wunderkind followed that with WHAT’S UP, DOC? (’72), a popular screwball comedy starring Barbra Streisand and Ryan O’Neal; and then with another comedy, this time set during the Depression called PAPER MOON (’73), also starring Ryan O’Neal. PAPER MOON would net three Oscar nominations and fetch O’Neal’s daughter, Tatum O’Neal who was 10 at the time, the Oscar for Best Actress in a Supporting Role.

Bogdanovich was on top of the world, an A-list director rubbing shoulders with all those other big names of the early ‘70s who were being hailed as a wave of “New Hollywood.” The next decade would not be so kind, but we’ll save that for another time.

#FilmStruck#Peter Bogdanovich#What's Up Doc?#The Last Picture Show#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolset#Barbra Streisand#Cybill Shepherd#Jeff Bridges#Orson Welles#Timothy Bottoms

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Buñuel’s Desert Mischief by Pablo Kjolseth

Last night I had a dream I was on set during the filming of Quentin Tarantino's PULP FICTION ('94) and today I'm writing about Luis Buñuel's SIMON OF THE DESERT ('65). Because it was a dream about a movie, and because Buñuel's movies often employ the grammar of dreams, I tried to find some correlations between the two directors. All I could come up with is that Tarantino and Buñuel are both foot fetishists who can be sadistic and they like black humor. Otherwise, it's apples and oranges with maybe a sliced eyeball or an ear on the side.

Buñuel (1900-1983) is that rare filmmaker who worked across eras, continents, and languages in a way that most can only dream of. It can't be said the work was fluid as it was more in fits and starts. Still: he made his mark in the silent film era working with Salvador Dali and causing scandals in France, then off to Spain to make a mockumentary and piss off Franco, then a stint in the U.S. dubbing movies for MGM. He also worked at MoMA and hilariously skated by the "are you a communist" question by answering "I am a Republican", with the interviewer not realizing Buñuel was a Republican for the Spanish socialist coalition government.

In 1942 Buñuel might have had his application for U.S. citizenship approved if not for Dali, who that same year published an autobiography outing Buñuel as a communist and an atheist. The Vatican found out and an American Archbishop railed on the museum for employing "the Antichrist" (apparently all it takes is making one blasphemous film to be pronounced The Prince of Darkness).

Buñuel resigned from MoMA but managed to get a gig at WB as a Spanish Dubbing Producer. It was 1944, and before leaving NYC for Hollywood Buñuel planned to confront Dali in a hotel and shoot the artist in the knee. This did not happen (probably for the best, as anyone who has seen I, TONYA can attest) but heated words were exchanged. Dali's riposte was to say "I did not write my book to put YOU on a pedestal. I wrote it to put ME on a pedestal."

Speaking of pedestals (I really can't ask for a better segue than that to jump into): SIMON OF THE DESERT, the story of the son of Simeon Stylites who lives for six years, six weeks, and six days atop a pillar close to 30 feet tall sticking out of the middle of the desert. A bit of context first: Buñuel moved to Mexico in 1946 and made a lot of movies, including such standouts as LOS OLVIDADOS (aka: THE YOUNG AND THE DAMNED, '50) which earned enough accolades to put him back in the international spotlight (ka-ching!). Eventually, international funding would help make VIRIDIANA ('61), which won the Palme d'Or and also won the ire of Franco (again) and The Vatican (again). Cue the backlash, bans, pronouncements of blasphemy and it’s back to Mexico!

VIRIDIANA, THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL ('62) and SIMON OF THE DESERT, form a trilogy of sorts insofar as they all starred the Mexican actress Silvia Pinal and were produced by Gustavo Alatriste. The two were married between '61 - '65, and during this time in 1963 they had a daughter they named Viridiana. SIMON OF THE DESERT would play a pivotal role in their break-up. SIMON OF THE DESERT was originally meant to be one of three stories with three different directors: Buñuel, Federico Fellini, and Jules Dassin. All three directors liked the idea of collaborating together however, Fellini suggested his wife Giulietta Masina be the star of his segment. Dassin followed Fellini's lead and also suggested his own wife, Melina Mercouri be the star of his segment. Alatriste jumped on the bandwagon, almost as if to say "hey, if this is going to be all about husbands directing their wives, maybe I should be Silvia's director." Even if only as co-director, Pinal did not like the idea. "I said no, and that was the beginning of our separation."

Even with that bit of baggage Pinal still considered SIMON OF THE DESERT one of her favorite films. At 43 minutes it doesn't feel like a short film, nor does it feel like a feature film. It does, however, feel like exactly the right amount of time to hang out with the priests, peasants, amputees, dwarfs, and hipsters that populate this delightful meditation on asceticism and the mischief of Satan.

28 notes

·

View notes