#The Tales of Hoffman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

badge of honor

#opera#opera tag#les contes d'hoffmann#the tales of hoffman#im not surprised it's me but im a little surprised im the only one there

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

15 notes

·

View notes

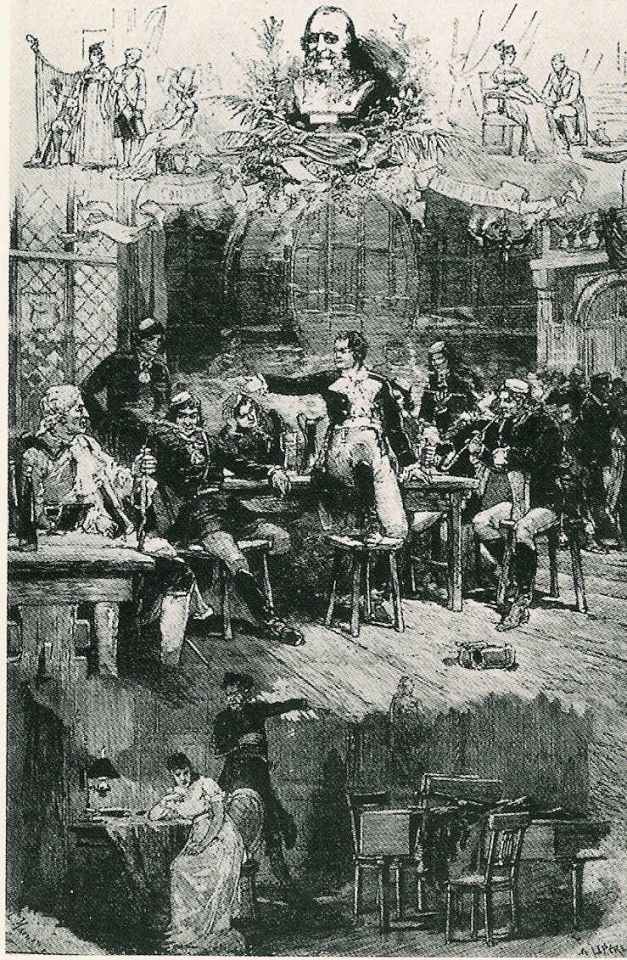

Photo

The Tales of Hoffman (1951)

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

#The Tales of Hoffman#Martin Scorsese#Powell and Pressburger#Moira Shearer#movies#film#movie review#movie#film review#movie critic#film critic#film criticism#movie criticism#moira shearer#the red shoes#1940s#Criterion Collection

0 notes

Photo

The Tales of Hoffmann (1951)

462 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Tales of Hoffman (1951) x Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) Part 2

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

several of my favorites frames from the “Olympia” sequence of The Tales of Hoffman (1951)

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

TFF 2018

Non sarò breve. La prenderò molto, molto alla lontana, come è mio solito.

Non vorrei sembrare Pertini redivivo, ma: io amo i giovani. Oddio, non tutti. Non quelli che non si curano della lingua italiana, imprecano ad ogni piè sospinto, si chiamano “raga” gli uni con gli altri, come fossero incapaci di pronunciare una parola integralmente... Peraltro conosco anche un gran numero di vecchi babbioni che si comportano allo stesso modo, sicchè ciò che non mi piace non è l’età ma l’idiozia (che dire di quel mio coetaneo che mi ha recentemente invitato “a fare una birrata”? SIC! E non tengo neppure conto del fatto che detesto la birra!).

Comunque, io amo i giovani: I giovani intellettuali, intendo. Perchè mi ci rivedo, mi commuovo, ma soprattutto perchè solo un intellettuale giovane legge e studia cose nuove, in una prospettiva nuova, con una comprensione nuova. Ed io trovo già abbastanza ripetitiva me stessa, figuriamoci i miei coetanei.

Ora, è ovvio che una signora oramai agée, quale io sono, non può andare in giro cercando frequentazioni giovanili, sostenendo che lo fa per il gusto della cultura - salvo essere Elsa Morante, che però, a differenza mia, era un genio, e poteva permettersi molte cose, seppure per un lungo periodo abbia, per così dire, mischiato il sacro con il profano... Dunque, volendo evitare non i pettegolezzi (che tanto vengono fatti a prescindere, anche se ci si destina alla monacazione), ma volendo scongiurare il senso del ridicolo che indurrei in me stessa per me stessa, mi astengo. Però, come si suol dire, chi è a dieta può sempre leggere il menù; ed è in questo spirito che io vado al TFF.

Al TFF di giovani intellettuali se ne incontrano a bizzeffe, soprattutto agli spettacoli del primo pomeriggio, e alle retrospettive più improbabili. Cosa spinge una ventenne a sorbirsi tre ore di “The Tales of Hoffman” di Powell-Pressburger, in questi tempi infami in cui “Scarpette rosse” non passa neanche più in televisione? Lo ignoro, e mi chiedo che effetto possano fare i colori sparatissimi anni ‘50, i piqué di Moira Shearer (niente male affatto!), l’eclatante bellezza di Ludmilla Tcherina (una danzatrice dalle attitudini così discutibili che Powell-Pressburger la misero in tutti i loro musicals impedendole sostanzialmente di ballare!). Io comunque ero affascinata. Anche dal film, s’intende.

Una menzione d’onore va anche a “Happy Birthday, Colin Burstead”, commedia (?!?) o aspro melodramma (?!?) britannico. A prescindere dalle difficoltà di comprensione di certi accenti uk (quando inizio a sentire “my” pronunciato “mi”, e le acca aspirate vengono sistematicamente buttate nella spazzatura, I know that I’m going to have a hard time... ), il film ha molti pregi, strappa alcune risate memorabili, ed è di una durezza infernale, che ti costringe a ricordare cose terribili sulla tua famiglia che sai benissimo ma a cui non vorresti esattamente pensare... Chissà come l’ha giudicato il ventenne che, poco prima dell’inizio, suggeriva serio serio ad una sua amica di leggere alcune opere minori di Freud in tedesco.

#TFF Torino#Festival Cinema Torino#Happy Birthday Colin Burstead#Powell-Pressburger#The Tales of Hoffman

1 note

·

View note

Text

the mortifying ordeal of being known

Benjamin Bernheim as Hoffmann and Kate Lindsey as Nicklausse in Les contes d'Hoffmann (Salzburg 2024)

#opera#opera tag#les contes d'hoffmann#the tales of hoffman#benjamin bernheim#kate lindsey#yes I'm still thinking about them#opera gifs#hoffmann gifs#salzburg hoffmann

20 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

FUCK YEAH PATRICIA JANEČKOVÁ! Performing Jacques Offenbach's "Les oiseaux dans la charmille" (Les contes d' Hoffmann / The Tales of Hoffmann)

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

George A. Romero’s Favorite Film of All Time is a Romantic Opera by Pablo Kjolseth

It's not entirely incongruous that George A. Romero, known to many for his walking dead creations, would cite THE TALES OF HOFFMANN (’51) as his favorite film of all time. After all, THE TALES OF HOFFMANN does feature one rather stunning scene wherein a woman reveals herself to be a mechanical wind-up toy only after she/it is taken apart limb from limb - leaving only a blinking head on the floor. Obviously, there's much more to the moment than meets the eye and Romero is surely responding to the overall passion and showmanship that spin throughout the movie - a movie that has inspired plenty of other filmmakers, such as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, who uses a clip from THE TALES OF HOFFMANN and evokes the story of the living doll torn to pieces in his film TETRO (’09).

Even if you’re not an opera fan all that is required to enjoy Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s THE TALES OF HOFFMANN is an appreciation for the fantastic and magical realms created by Georges Méliès and Dr. Seuss. The theatrical interiors and landscapes are out of this world. Shot in dazzling Technicolor and featuring amazing production and costume designs by Hein Heckroth (who was nominated for two Academy Awards for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration and Best Costume Design), THE TALES OF HOFFMANN sings and dances its way from one romantic fable to the next with surrealistic aplomb. The film itself was a winner at Berlin, where it won for Best Musical, and at Cannes, picking up a Special Award “For the transposition of a musical work into a film.”

The musical work in question is Jacques Offenbach’s (1819 - 1880) opéra fantastique of the same name and is based on the highly fictional short stories of author E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776 - 1822). Hoffmann also authored The Nutcracker and the Mouse King (which in turn formed the basis for Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker ballet). With ballet in mind, viewers familiar with the work of The Archers (Powell and Pressburger’s Archers Film Productions, formed in 1943) might now recall the ballet sequence of THE RED SHOES (’48), based on a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. That was a precursor to Powell’s goal to marry filmed images to operatic music, which found its full form in THE TALES OF HOFFMANN. And speaking of this marriage, if you’d like a crash course in how to edit a movie to music, here’s a good place to start because the entire opera soundtrack for THE TALES OF HOFFMANN was pre-recorded and then the film was edited to the rhythm and tempo of the music.

The film appropriately starts with a prologue that shows Hoffman raptly watching a ballet performance by Stella. Stella wants to meet Hoffman after the show and sends him a note. The message is never delivered because it is intercepted by a rival. Hoffmann then leaves dejected and heads off to the tavern where he proceeds to get blitzed as he reminisces about three past loves. Primary colors highlight each tale. Yellow for the first, red for the second and blue for the third. We also move, respectively, from Paris to Venice, and then Greece, each exotic locale showcasing stunning set designs. In writing about Michael Powell in his A Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson recalls a man who spent time as director emeritus with Coppola's American Zoetrope and someone who was a “treasured Merlin at the court of Scorsese,” invoking also “his marriage to the editor, Thelma Schoonmaker” and finishes by saying: “I do not invoke the figure of Merlin lightly: Powell was English but Celtic, sublime yet devious, magical in the resolute certainty that imagination rules.”

I mentioned Méliès and Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel) earlier on, who I also consider magicians. The latter was a German-American artist whose life-line (1904 - 1991) closely mirrored those of Powell (1905 - 1990) and Pressburger (1902 - 1988). The only feature film Geisel ever wrote was a musical fantasy called THE 5,000 FINGERS OF DR. T (’53), directed by Roy Rowland (Stanley Kramer also, uncredited). The two films will forever be linked together in my mind because I was only seven-years-old when I first saw stills from both movies sharing the same page of David Annan's book Cinefantastic: Beyond the Dream Machine, and in which he writes: “The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T is the best fantasy musical yet made, just as The Tales of Hoffmann brought the chilling fairy stories of childhood best to the screen in the form of a ballet.”

#The Tales of Hoffman#FilmStruck#Michael Powell#Emeric Pressburger#George A. Romero#StreamLine Blog#Pablo Kjolseth

43 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

From Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffman

0 notes

Text

#The Tales of Hoffman#Powell and Pressburger#Ballet#Opera#movies#film#movie review#movie#film review#movie critic#film critic#film criticism#movie criticism#Martin Scorsese#Moira Shearer#Criterion Collection#criterion collection#criterion channel

0 notes

Photo

The Tales of Hoffman (1951)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Tales of Hoffman, 1951

150 notes

·

View notes