#Old English Literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It's high time I familiarize Tumblr with my niche (at least I think so?) interests. BEOWULF.

Special thanks to my literature professor who read it out to us in Old English and made the funniest Grendel impression I've ever seen

(famous un-arming situation with detail because I adore drawing his face)

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dying Beowulf, having just defeated the dragon, is supported by his ally Wiglaf. Illustration by George T. Tobin from Siegfried, the Hero of the North, and Beowulf, the Hero of the Anglo-Saxons by Zenaide A. Ragozin, published in 1909. Now in the New York Public Library.

#art#art history#George T. Tobin#illustration#Beowulf#Germanic mythology#Old English#Old English literature#Middle Ages#medieval#medieval literature#American art#20th century art#New York Public Library

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m trying so hard to romanticize studying for my old English literature midterm 🫠

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

me when I accidentally type "that would be geat" instead of "that would be great"

#beowulf#old english literature#literary shitposts#sylvie's own nonsense#jokes that are only funny to me

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tolkien challenged existing attitudes to the poem in a 1953 paper, “Ofermod”, published with his verse drama The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son in Essays and Studies. “The Battle of Maldon” tells how Beorhtnoth, an Anglo-Saxon leader, led his men in a doomed defence against a Viking attack. The Vikings were on a tidal island in the river; but crucially Beorhtnoth decided to let this marauding force across a causeway (pictured above). Battle was joined, and the English were slaughtered. The poem seems to celebrate what has been called “Northern courage”, a spirit of dogged bravery even in the face of certain defeat. But the poet also describes Beorhtnoth’s decision as the product of ofermod, the meaning of which isn’t entirely clear. Tolkien argued that the Old English word means not simply “daring” but “overmastering pride”. This could be taken to reverse the sentiment of the poem, turning it into a critique of an irresponsible act of leadership. Stuart, whose book The Keys of Middle-earth (written with Elizabeth Solopova) provides a guide to Tolkien’s medieval sources, has been looking at Tolkien’s manuscript notes on the poem, from when he was an undergraduate onwards. And it turns out that Tolkien breathed not a word of criticism of Beorhtnoth for many years – not until around the start of the Second World War. This, Stuart suggests, undermines any supposition that Tolkien’s view of “The Battle of Maldon”, as expressed in his “Ofermod” essay, indicated a “lions led by donkeys” attitude shaped by First World War experiences. I’d agree that Tolkien’s view of the Great War military leaders wasn’t as black-and-white as all that. But I’d certainly argue that his trench experiences gave him some reason to feel very ambivalent about the leaders. As I said at the end of Stuart’s talk, there is the case of one company commander in Tolkien’s battalion who led a company on a night raid that overshot its goal – so when the sun rose, they were sitting ducks for the German machine-gunners and for the British artillery (unaware of their position), and most of the men were wiped out. This fatally over-extended advance by a military leader seems echoed in quite a few incidents in Middle-earth, including the charge by Théoden at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Tolkien’s writing displays a range of attitudes to the different incidents – implying, I think, that he felt deeply ambivalent about such acts of courage from leaders responsible for others’ lives. In a talk which also covered a number of other interesting points from the manuscripts at the Bodleian Library, Stuart cautioned against looking to Tolkien’s life or to contemporary events to explain the change in Tolkien’s views on “The Battle of Maldon”. The Second World War itself could have led to a shift in Tolkien’s view – perhaps because he saw ofermod at its worst in Hitler. And as I pointed out, his later view might have been coloured by the fact that two of his sons were in the forces, and facing mortal danger, whereas Tolkien himself had to sit on the sidelines powerlessly. However, Stuart‘s point was not about the creative writer but the rigorous scholar. As he said in a later email exchange, whatever Tolkien felt about the military leadership of 1914-18 (a debatable question), “he was entirely at liberty to overlay these views onto scenes or characters in his fiction, of course, and did so I believe; but he was too great a scholar to allow his own personal feelings and experiences in the 20th century to colour his views of the tenth.” That’s a persuasive argument.

#tolkien#tolkien studies#j.r.r. tolkien#the battle of maldon#ofermod#old english#anglo saxon poetry#old English literature#tolkien and the great war#the somme#wwi#wwii#tolkien's ambivalent views on military leadership#tolkien as academic#i agree that he would have tried to contextualise Beorhtnoth in the era in which he lived rather in Tolkien's contemporary era#john garth

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Key Literary Works in Old English, such as "Beowulf"

Old English Literature Old English literature provides a fascinating glimpse into the early literary culture of England. Among the most significant works from this period are “Beowulf,” “The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” “Caedmon’s Hymn,” and “The Exeter Book.” Each of these texts offers unique insights into the values, beliefs, and experiences of the Anglo-Saxon people. Beowulf Overview “Beowulf”…

#Anglo-Saxon Chronicle#Anglo-Saxon Literature#Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts#aprender inglés#Beowulf epic poem#Caedmon’s Hymn#Early English Literary Works#Old English Heroic Tales#Old English literature#Old English Poetry#The Exeter Book

1 note

·

View note

Text

petition to instate "buckle up" as the universally accepted translation of hwæt

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poetry is what helps me remember that even in my fragments, I am whole.

- Jennifer Huang

#pics from pinterest#dark academia#chaotic academia#spilled words#spilled ink#qoutes#booklr#reading#classic academia#books and libraries#light academia#romanticism#autumn#books books books#bookish#literature#classic literature#english literature#writeblr#dark academism#bookworm#old books#book quotes#nostalgia#aesthetic moodboard#dark academia aesthetic#academia aesthetic#cottagecore#dark cottagecore#romantic academia

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria Dahvana Headley's translation of Beowulf is so much more than a funny translation of the Old English poem! The reason why Headley decides to start her translation with "Bro!" is rooted in the same problem Wilson encountered in her translation of the Odyssey. The meaning of original Old English word, "hwæt", is still debated today by scholars — and it's the first word of the poem. Even some passages of the rest of the work are still arcane to us today. This is why Headley's translation is so important — and peculiar. She takes obscure lines with uncertain meaning and tries to give them one that works in the minds of modern readers. There's a line that says Beowulf "makes sushi out of all the monsters he kills". Does this imply that Medieval people knew what sushi was? No, of course not. It just creates an image in our very modern minds. Another favourite of mine is the line "Bro, fate can fuck you up". I want this engraved on my tombstone.

Another reason why Headley chooses to translate "hwæt" with "bro" is to show the world the machism and intrinsic misogyny present in the poem — and in Medieval England in general. So yeah, kudos to her for that!

To end it on a bittersweet note, my tutor — an Old English professor — doesn't really like her translation. I found it brilliant.

Throughout her translation of the “Odyssey,” Wilson has made small but, it turns out, radical changes to the way many key scenes of the epic are presented — “radical” in that, in 400 years of versions of the poem, no translator has made the kinds of alterations Wilson has, changes that go to truing a text that, as she says, has through translation accumulated distortions that affect the way even scholars who read Greek discuss the original. These changes seem, at each turn, to ask us to appreciate the gravity of the events that are unfolding, the human cost of differences of mind.

The first of these changes is in the very first line. You might be inclined to suppose that, over the course of nearly half a millennium, we must have reached a consensus on the English equivalent for an old Greek word, polytropos. But to consult Wilson’s 60 some predecessors, living and dead, is to find that consensus has been hard to come by…

Of the 60 or so answers to the polytropos question to date, the 36 given above [which I cut because there were a lot] couldn’t be less uniform (the two dozen I omit repeat, with minor variations, earlier solutions); what unites them is that their translators largely ignore the ambiguity built into the word they’re translating. Most opt for straightforward assertions of Odysseus’s nature, descriptions running from the positive (crafty, sagacious, versatile) to the negative (shifty, restless, cunning). Only Norgate (“of many a turn”) and Cook (“of many turns”) preserve the Greek roots as Wilson describes them — poly(“many”), tropos (“turn”) — answers that, if you produced them as a student of classics, much of whose education is spent translating Greek and Latin and being marked correct or incorrect based on your knowledge of the dictionary definitions, would earn you an A. But to the modern English reader who does not know Greek, does “a man of many turns” suggest the doubleness of the original word — a man who is either supremely in control of his life or who has lost control of it? Of the existing translations, it seems to me that none get across to a reader without Greek the open question that, in fact, is the opening question of the “Odyssey,” one embedded in the fifth word in its first line: What sort of man is Odysseus?

“I wanted there to be a sense,” Wilson told me, that “maybe there is something wrong with this guy. You want to have a sense of anxiety about this character, and that there are going to be layers we see unfolded. We don’t quite know what the layers are yet. So I wanted the reader to be told: be on the lookout for a text that’s not going to be interpretively straightforward.”

Here is how Wilson’s “Odyssey” begins. Her fifth word is also her solution to the Greek poem’s fifth word — to polytropos:

Tell me about a complicated man. Muse, tell me how he wandered and was lost when he had wrecked the holy town of Troy, and where he went, and who he met, the pain he suffered in the storms at sea, and how he worked to save his life and bring his men back home. He failed to keep them safe; poor fools, they ate the Sun God’s cattle, and the god kept them from home. Now goddess, child of Zeus, tell the old story for our modern times. Find the beginning.

When I first read these lines early this summer in The Paris Review, which published an excerpt, I was floored. I’d never read an “Odyssey” that sounded like this. It had such directness, the lines feeling not as if they were being fed into iambic pentameter because of some strategic decision but because the meter was a natural mode for its speaker. The subtle sewing through of the fittingly wavelike W-words in the first half (“wandered … wrecked … where … worked”) and the stormy S-words that knit together the second half, marrying the waves to the storm in which this man will suffer, made the terse injunctions to the muse that frame this prologue to the poem (“Tell me about …” and “Find the beginning”) seem as if they might actually answer the puzzle posed by Homer’s polytropos and Odysseus’s complicated nature.

Complicated: the brilliance of Wilson’s choice is, in part, its seeming straightforwardness. But no less than that of polytropos, the etymology of “complicated” is revealing. From the Latin verb complicare, it means “to fold together.” No, we don’t think of that root when we call someone complicated, but it’s what we mean: that they’re compound, several things folded into one, difficult to unravel, pull apart, understand.

“It feels,” I told Wilson, “with your choice of ‘complicated,’ that you planted a flag.”

“It is a flag,” she said.

“It says, ‘Guess what?’ — ”

“ ‘ — this is different.’ ”

The First Woman to Translate the Odyssey Into English, Wyatt Mason

#beowulf#translation#classics#classical literature#old english#old english literature#why is there no old english lit tag on tumblr?#academia

36K notes

·

View notes

Text

Everybody so full of lust, bring back real lovers.

#spilled emotions#spilled ink#lust#real lovers#love#intimacy#english literature#literature#light academia#feelings#writeblr#dumblr#old school

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Coziest bookshop I’ve ever seen | Word on the Water, London

#bookblr#books#vsco#photography#vscogood#vscocam#aesthetic#english major#literature#bookshop#bookshelf#bookworm#old books#bookstore#books and reading#cozyplaces#cozy vibes#cozy#cosy mood#cosyvibes#warm and cosy#cosy aesthetic

457 notes

·

View notes

Text

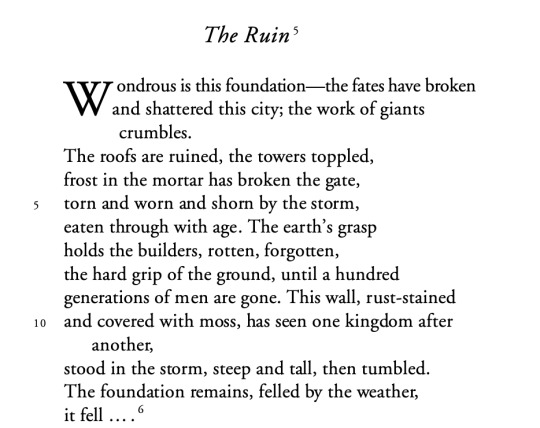

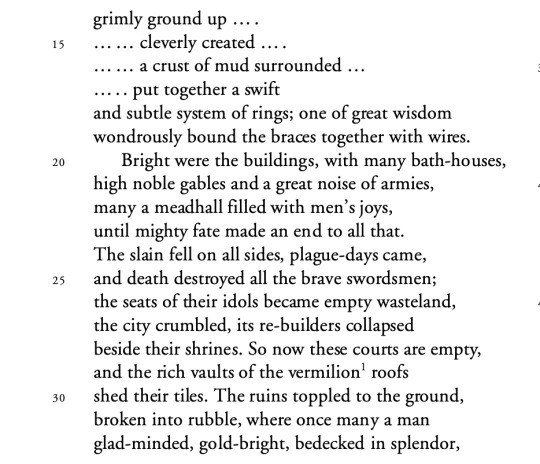

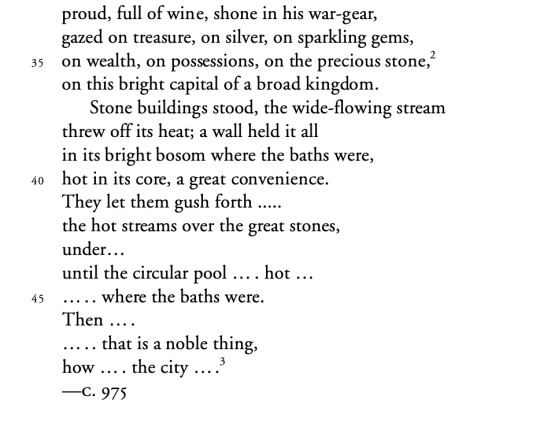

*activate special interest mode* I read this poem in an undergrad class and it always makes my head spin to think about the spans of time involved—the fact that the poet describing this 'ancient ruin' is, themself, so far-removed from the present day that their English is incomprehensible to us modern speakers and requires translation.

But speaking of translation, I love this one, because it preserves a rhythm from the original that is usually lost in other translations I've seen.

There's a section of the poem where the original poet uses words that end in 'orene'/'orone' (pronounced something like 'or-uh-nuh') to emphasise the sense of destruction.

Hrofas sind gehrorene, hreorge torras, hrim geat torras berofen, hrim on lime, scearde scurbeorge scorene, gedrorene, ældo undereotone. Eorðgrap hafað waldend wyrhtan forweorone, geleorene, heardgripe hrusan, oþ hund cnea werþeoda gewitan.

And here's a typical translation of that section:

Roofs are fallen, ruinous towers, the frosty gate with frost on cement is ravaged, chipped roofs are torn, fallen, undermined by old age. The grasp of the earth possesses the mighty builders, perished and fallen, the hard grasp of earth, until a hundred generations of people have departed.

There's nothing wrong with this translation—it gets the point across.

But here's what this translator, R.M. Liuzza has done with it:

The roofs are ruined, the towers toppled, frost in the mortar has broken the gate, torn and worn and shorn by the storm, eaten through with age. The earth's grasp holds the builders, rotten, forgotten, the hard grip of the ground, until a hundred generations of men are gone.

And I think that's brilliant! Liuzza preserved those rhymes to great effect, and the 'orn' words they use are even similar to the 'orene' (remember, it's pronounced more like 'or-uh-nuh') sounds used in the original.

The Ruin, Anonymous Old English Poem, trans R.M. Liuzza

#the main detail i remember from the poem is those 'orene' words and how much i liked them#so when i saw this translation with 'torn and worn and shorn' i was like !!!!!!#LOVE this#also just love this poem in general but YEAH#and i can nerd out over old english/middle english any day#i'm by no means an expert I Just Think It's Neat#old english#old english literature#poetry#anglo saxon#medieval poetry#medieval literature#dark ages#literary analysis#sylvie's own nonsense#my addition#translation#literature in translation

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Virginia Woolf

#dark academia#dark academia aesthetic#light academia aesthetic#classic literature#english literature#vintage#fictional character#old school#virginia woolf#literature memes#books and libraries

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fairies Farewell Lament: Old Abbies (1864) - Birket Foster

#art#etching engraving#gothic#illustration#book illustration#english literature#english ballads#the fairies farewell lament lament old abbies#old english ballads#birket foster#1864#architecture#gothic ruins#abbey ruins#carus#caspar david friedrich

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Old English Literature

Old English literature, from Beowulf to The Wanderer, delves into heroism, fate, and faith, reflecting Anglo-Saxon culture while blending Christian and pagan influences. It helped shape modern English literature.

A Window into the Anglo-Saxon World Old English literature offers a captivating glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and struggles of the Anglo-Saxon people. Flourishing between the 7th and 11th centuries, it is primarily known for its epic poems and religious texts, which capture themes of heroism, fate, faith, and social structure. Key works like “Beowulf,” “The Wanderer,” and “The Seafarer”…

#Anglo-Saxon England#Anglo-Saxon poetry#Beowulf#epic poems#medieval literature#Old English literature#The Seafarer#The Wanderer

0 notes

Text

Honeymoon

J.C. Leyendecker 1926

#western art#romantic#romantic art#heraldry#medieval#medieval aesthetic#light academia#romantic academia#romantic aesthetic#mine#traditional catholic#christian blog#vintage art#traditional gender roles#traditional family#traditional values#traditional marriage#middle earth#lord of the rings#king arthur#arthurian mythology#english literature#literary aesthetic#catholic#literary#old fashioned#old books#nostalgic

378 notes

·

View notes