#Not just in the published silmarillion but in the Book of Lost tales as well

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What do a beautiful elf princess and an evil demon spider have in common? Surprisingly, quite a bit.

Both weave cloaks of shadow in their dwellings, Ungoliant's from her webs and Lùthien's from her own hair(Lùthien in the Leithian even describes her cloak as a web. "I will weave within my web that hell/nor all the powers of dread shall break") Ungoliant's webs and Lùthien's cloak hold a magical effect over things and people, Ungoliant's bringing blindness while Lùthien's brings drowsiness. Out of the same material both create ropes, Ungoliant climbing up to leave Avathar and Lùthien climbing down from Hirilorn. Ungoliant climbs up to Hyarmentir, "the highest mountain in that region of the world", while the great tree Hirilorn is called "greatest of all the trees in the Forest of Neldoreth" and the Leithian describes the tree as "the mightiest vault of leaf and bough / from world's beginning until now." Ungoliant later makes her way to the Two Trees with Melkor, while Lùthien escapes from a tree to rescue Beren.

There's similarities between the places that Lùthien and Ungoliant escape from too, being Doriath and Valinor respectively. Both of them are described as being surrounded by a great barrier of "shadow(s) and bewilderment". (There are also mentions of only one person being able to make it through said barriers, being Beren and Earendil.)

Both Lùthien and Ungoliant help Beren and Melkor in stealing the silmarils, and by help I mean assisting to the point that it is them who seem to be doing most of the actual work. (Beren literally just needs to sit back and watch as Lùthien puts all of Angband to sleep singlehandedly. It is Ungoliant who does most of the actual darkening in the darkening of Valinor, and in an earlier version Ungoliant destroys the Two Trees all by herself. Melkor isn't even there.)

And it's all rather funny looking at this because though they have these similarities they could not be more different. Lùthien is a beautiful elf princess who defeats both Sauron and Morgoth through the power of ✨️True Love✨️ who personally couldn't care less for the silmarils, and Ungoliant is a gigantic hideous demon spider who eats light itself like a black hole and nearly devours Melkor alive when he doesn't give her the silmarils(talk about toxic relationship lol). Lùthien heals, Ungoliant poisons. Lùthien brings Light, Ungoliant brings Darkness(or rather Unlight). Lùthien acts out of love, Ungoliant acts out of selfishness.

They could not be more, completely different. Lùthien is the Anti-Ungoliant. Ungoliant is the Anti-Lùthien. And yet they have these subtle similarities and it drives me insane.

IT'S ABOUT THE SIMILARITIES AND YET STARK CONTRASTS

#There's actually quite a lot of other subtle similarities between the two stories and it fascinates me#Not just in the published silmarillion but in the Book of Lost tales as well#But I simply do not have the energy to write it right now#silmarillion#Tolkien#Luthien#Ungoliant#Beren and Luthien

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book of Lost Tales Promo Post

(written by @dawnfelagund)

Summary: Tolkien began writing the "Silmarillion" as a young man in the trenches of World War I. The Book of Lost Tales are the stories he penned during this period of his life and represent his earliest work on the "Silmarillion." Many of the familiar tales are already present in their early form: the cosmic conflict between the Valar and Melkor, the tale of Beren and Lúthien, and the Fall of Gondolin, to name just three. These stories are embedded in a frame narrative where the Anglo-Saxon mariner Eriol ends up visiting Eressëa and hearing a series of stories from the Elven residents there. The Lost Tales were never finished in their entirety, so while some of the early stories are complete, others are fragmentary or just outlines. Each tale is accompanied by commentary from Christopher Tolkien, who edited the collection.

Why Should I Check Out This Canon? The Lost Tales are recognizably "Silmarillion" stories, yet they differ greatly in style and tone from Tolkien's later work. They are more whimsical and more like the Victorian fairy-stories that Tolkien later denigrated. Magical elements abound, and the texts are more playful than the more sober "Silmarillion" texts Tolkien would write in the decades to come. In addition, they contain copious detail, especially about the Valar and Maiar, their homes in Valinor, and their adventures against Melkor.

For creators who work with the published Silmarillion, the Lost Tales can provide canon details that expand what is available in The Silmarillion (Nienna lives in a hall constructed of bat wings!) or deviate from it in surprising and delightful ways (Sauron is the prince of cats!)

Where Can I Get This? The Book of Lost Tales comprise the first two volumes of the History of Middle-earth series. They are available as both print and ebooks. For a reader not up for two volumes of sometimes dense reading, individual stories stand well on their own.

What Fanworks Already Exist? There is no tag on AO3 specifically for The Book of Lost Tales. Creators use several different Tolkien tags to mark these works. On AO3, you may have luck finding Lost Tales fanworks here. The #book of lost tales tag on Tumblr has more fanworks.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comparing the Captures of Maedhros and of Húrin thoughout versions

Note: I did not include all volumes of HoME in this however with the exception of Volume Eleven which contains The Wanderings of Húrin there are few meaningful differences. I will make a later post for more HoME content

Second note: I also have a post comparing the fates of Morwen, Aerin post Nírnaeth and Dor-lómin generally which I also will work on to revise and republish

It is notable to me that Húrin and Maedhros are among the only named figures Morgoth successfully orders the capture of by name. I wanted to explore the similarites and differences between varying versions.

Here are the two that are probably considered most canonical, from The Silmarillion and The Children of Húrin respectively

Maedhros was ambushed and all his company were slain but he himself was taken alive by the command of Morgoth and brought to Angband (The Return of the Noldor, The Silmarillion)

...but they took him at last alive by the command of Morgoth who thought thus to do him more evil than by death (The Battle of Unnumbered Tears, The Children of Húrin)

Morgoth’s intentions for Húrin are far more clear than for Maedhros. He knows ( “by his art and his spies”) that Húrin had the friendship of the King (Turgon in this case). It’s not entirely clear yet if Morgoth has heard rumors that Húrin had been to Gondolin but he certainly knows of the brothers reunion on the battlefield with Turgon and makes some quick connections. The conversation between Húrin and Morgoth spans almost the entirety of chapter three and has some of the most dialogue for Morgoth in the entire Legendarium

@tolkien-feels once made a joke about the conversations between Túrin and Sador in chapter one being like forced to go through the Athrabeth with a child and I think The Words of Húrin and Morgoth function almost in a similar way; some of the deeper philosophical questions of the universe involving mortality and fate and the reach of the gods are raised in these horrifying circumstances.

(I won’t go into it too much here because there is so much to say about this, but I’ll link a couple of my posts on it just for my own reference and organization here and here

Morgoth certainly tried to use the capture of Maedhros to his own advantage when he sends word to his brothers claiming he’d release him if they retreated but this attempt is rather perfunctory and I don’t think he truly thought it would go anywhere. At best, the Fëanorians might be spurred or goaded into further recklessness trying to recover Maedhros. At worst, nothing would happen for some time.

A fascinating difference between the notes of Tolkien that later became this part of the published Silmarillion is that in the original notes, two more words are added to the quote above. Maidros was ambushed, and all his company was slain, but he himself was taken alive by the command of Morgoth, and brought to Angband and tortured. (HOME V, p. 274)

In the version in the Book of Lost Tales, Maedhros is captured at the gates of Angband during a siege. He is tortured for information on jewel making, no word given on the success of this interrogation, and then released alive though maimed in an eerily vague afterthought. I have more on this in my BoLT tag, I find it fascinating for the ways it mirrors Húrin’s release in later canon

In the Lays of Beleriand Maedhros is mentioned only briefly though interestingly, most of his mentions include note of his torment, the most prominent appearing in The Lay of the Children of Húrin

in league secret with those five others, in the forests of the East fell unflinching foes of Morgoth Maidros whom Morgoth maimed and tortured is lord and leader, his left wieldeth his sweeping sword

Both the use of the name Maidros as well as the specifications of ‘maimed and tortured’ appear to take after the Book of Lost Tales version however the Lays goes further and confirms that the maiming left so vague in BoLT did indeed include the loss of Maedhros’s right hand. And of course it’s notable that Morgoth did this, not Fingon during rescue.

Húrin‘s capture and imprisonment remain fairly consistent throughout the more known versions of the story, that is, in the Silm, in the Narn, and in the unfinished tales. Even in BoLT and the Lays the general outline is similar. In the Silm and the Narn, the story is consistent though of course much is cut out in the Silm version. Unfinished Tales has no significant changes to this section of the text.

In BoLT which is not considered canon, Úrin as he’s called there is captured during battle and both threatened with torture and offered great riches to betray Turondo (Turgon). When he refuses, Melko sets him in a ‘lofty place of the mountains’ and curses him to watch the doom of Morwen and his children. (”at least none shall pity him for this, that he had a craven for a father”). Húrin has not been to Gondolin in this version. This version is notable in this regard for a few things: One, Morgoth spends far less time with Húrin and no mention of physical torture apart from threats of it is noted prior to his imprisonment in the mountains and the curse. Two, the actual dialogue between them is rather different and briefer. Morgoth tries to take advantage of the poorer views by the elves towards humans by offering employment to Húrin but without success.

The version in the Lay of the Children of Húrin is more similar to the Narn and Silm. There is more extended contact between Morgoth and Húrin (though the contents of their talk is still different). It’s also perhaps the most vivid in descriptions of torture and imprisonment and the only version where actual methods of torment are mentioned or implied (namely whips and brands).

I definitely want to go into this version more later! As always please feel free to ask more! I will also go into more versions throughout HoME of both these storylines if there’s interest!

Final notes:

No version of Húrin in Angband will be as disturbing to me as Húrin’s imprisonment by his own kin in Brethil in The Wanderings of Húrin

#the silmarillion#the children of húrin#maedhros#Húrin#in the iron hell#musing and meta#BoLT#HoME#the lays of beleriand

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three Houses of the Edain Edit Series: Appendix B

Continued from Appendix A. This section will contain information on the House of Hador.

~~~

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Appendix A: House of Bëor Appendix B: House of Hador (you are here!) Appendix C: House of Haleth, Drúedain

~~~

HOUSE OF HADOR

Note: With regard to name translations, I took inspiration from this article; specifically, I used some of the suggestions for name meanings of the early Hadorians and assigned them to elements in my Taliska glossary (see Appendix A).

~~~

Marach ft. Marach, Legen (OC), Malach Aradan, Imlach It is canon that while they were the third House to enter Beleriand, Marach’s people were originally in the lead; also canon is the attitude of the Green-elves toward them and Marach’s decision to remain in Estolad even though his son led many of his people further west. Since Imlach’s son Amlach is still in Estolad during the time of dissent, it is highly probable (though not explicitly stated afaik) that Imlach remained with his father. Everything else is headcanon. Also, Marach is trans because I said so <3

Imlach ft. Imlach, Amar (OC), Amlach The basic structure of this story is canon: Malach remained in Estolad; Amlach was a dissenter who was impersonated and became an elf-friend in his anger at the deception, entering into Maedhros’ service. I added a lot of details to flesh out the story, especially Amlach’s confusing night in the forest. I think Sauron (or one of his servants) stranded him in the woods and stole his likeness, though I doubt Amlach ever really figured out exactly what happened.

Malach Aradan ft. Malach Aradan, Zimrahin Meldis, Adanel, Magor Malach did enter Fingolfin’s service, and the basic details of his familial relationship are canon. Much of the rest of this is headcanon, however.

Magor ft. Magor, Amathal (OC), Hathol, Thevril (OC), Hador Lórindol We don’t know much about Magor or Hathol; the only canonical detail here is that Magor did move his people away from Hithlum and served no elf lord (though we don’t have details on why). Everything else is headcanon.

Hador Lórindol ft. Hador Lórindol, Gildis, Glóredhel, Galdor of Dor-lómin, Gundor This is mostly canon, though it has been embellished, and everything about Gildis other than her name is headcanon. Gundor’s life is also mostly headcanon, though the manner of his death is canon; I’ll go into his story soon.

Gundor ft. Gundor, Angreneth (OC), Indor, Padrion (OC), Aerin, Peleg We don’t know anything about Gundor other than the manner of his death; we also don’t know how Aerin is related to Húrin, so I decided to expand on both of those unknowns with the same story. Aerin’s father is said to be Indor, who is elsewhere said to be the father of Peleg (who was himself the father of Tuor in an early draft), so I made him the son of Gundor. Since Peleg obviously can’t be Tuor’s father anymore, I killed him off at the Nírnaeth...just like Huor, oops. I think Brodda took Aerin to wife before Morwen disappeared, but I couldn’t figure out how to word that concisely, so I left it kind of vague/misleading in the caption. Oh well.

Galdor of Dor-lómin ft. Galdor of Dor-lómin, Hareth, Húrin Thalion, Huor This is mostly canon, though it has been embellished to give Hareth a bit of personality. Ylmir is the Sindarin name for Ulmo, used by Tuor in his song “The Horns of Ylmir.”

Húrin Thalion ft. Húrin Thalion, Morwen Eledhwen, Túrin Turambar, Beleg Cúthalion, Urwen Lalaith, Niënor Níniel Boy howdy this is a long one! It’s almost entirely canon, though I’ve added some embellishments here and there. Beleg is included because he and Túrin were definitely married (at least by elven standards); I’ll go more into that, and the details of Túrin’s time with the Gaurwaith, in a future edit, but for now I settled just using the gayest possible language. Same deal for his time in Nargothrond.

Huor ft. Huor, Rían, Tuor Eladar We don’t know that Galdor took an arrow specifically to the eye, but I thought it would be poetic if both he and Huor died in the same manner so I added that detail to the canon that Galdor was killed by an arrow. The rest of this is pretty much all canon, with some embellishments. Tuor’s story will continue in another edit.

Tuor Eladar ft. Tuor Eladar, Idril Celebrindal, Eärendil Ardamírë The meat of this story is canon, but I’ve added in some of my headcanons as well. I definitely embellished Annael’s departure from Mithrim to show my perspective on his decision to leave Tuor behind (I really do think he thought Tuor was dead or as good as it, and that as a leader he had the responsibility to keep the rest of his people safe). I’m a little foggy on why Tuor was already so obsessed with Gondolin when he met Gelmir and Arminas, because why would the Sindar of Mithrim be so excited about a Noldorin city? I guess maybe they had friends from way back when who went with Turgon? Or maybe they just wished they could be “safe” like the Gondolindrim were, idk. I was kind of vague there. Ylmir is the Sindarin name for Ulmo; Yssion is a Sindarin name for Ossë (the other one is Gaerys, which I think sounds cooler but isn’t as close to a literal Sindarization as Yssion). The bit about Voronwë teaching Tuor Quenya on the road is headcanon, but I think it makes a lot of sense. Telpevontál is my Quenya translation of Celebrindal. I skimmed and skipped a lot of Tuor’s time in Gondolin, since I went over that in another edit. “The Horns of Ylmir” is a real song that Tolkien wrote (Adele McAllister has a cover of it); I added the bit about it triggering Idril’s foresight, though the song is absolutely foreshadowing no matter how you look at it. Eärendil did canonically get married the same year that Tuor and Idril left for Valinor; we don’t have much info on that otherwise, so I made it as bittersweet as possible. The bit about the Elessar is a lot of convoluted headcanon in my attempt to make sense of its 3 bajillion different origin stories. The name Ardamírë is prophetic because, you know, the whole Silmaril thing, but I liked the idea that Idril made the connection with the Elessar before the Silmaril came into the picture. All we know about Idril and Tuor’s fates in canon is that people ~believe~ they made it to Aman and that Tuor was counted as an elf, but that last bit never sat right with me since elsewhere it’s very clearly stated that the Gift of Men is not something that can be refused or taken away. The alternate legend is my own headcanon for what happened to them (I also think they had more peredhil kiddos); in my mind, the Valar let Tuor live the rest of his days in Valinor (all 500 years of them, I just think it’s poetic and connected to his grandson Elros’ fate) before he died peacefully and willingly, able to get closure with Idril before he went.

Storytellers ft. Eltas, Dírhaval Eltas is a character from the Book of Lost Tales, who tells Eriol the “Tale of Turambar.” Supposedly, he once lived in Hísilómë (Hithlum) and came to Tol Eressëa and the Cottage of Lost Play by the Straight Road. That story does not add up at all when you look at it through the lens of Tolkien’s later Legendarium, so I took the name and his origins in Hithlum and crafted an entirely different story for him. Dírhaval is canonically the poet who wrote the Narn i Chîn Húrin; he only wrote that one poem because he was killed at the Third Kinslaying before he could finish any of the other Great Tales like Narn i Leithian (The Lay of Leithian; from his Tolkien Gateway article I think that’s what he was working on after CoH? but I’m not totally sure. But Tolkien never finished the Leithian either, so I think it’s poetic to have Dírhaval do the same). Andvír was one of his sources in canon, I added in the others (Eltas, Nellas, Celebrimbor, Glírhuin), though it was conceivable (and canon, in Nellas’ case) that they knew Túrin enough to report his story (though we don’t know anything in canon about Nellas’ fate). These name translations are my own; I thought “sitting man” worked as a meaning for Dírhaval since I imagine that storytellers like him were known as folk who sat around a lot writing or telling tales.

Servants of Morwen ft. Morwen Eledhwen, Gethron, Grithnir, Ragnir the Blind, Sador Labadal Morwen sending her servants to talk to the elves is headcanon, and so is Gethron knowing some Sindarin, though I think that makes sense considering he did canonically travel across Beleriand and was the one who spoke to Thingol when they arrived in Doriath. We don’t know anything in canon about Ragnir except that he was blind. Sador’s story is canon, though I have added some embellishments here and there. Aside from Sador and Morwen, these name translations are all my own and extremely dubious, but I did my best.

Companions of Húrin ft. Húrin Thalion, Asgon, Ragnir the Outlaw, Dringoth (OC), Dimaethor (OC), Negenor (OC), Tondir (OC), Haedirn (OC), Orthelron (OC) This edit tells the beginning part of “The Wanderings of Húrin,” an unfinished manuscript that was cut from the final published Silmarillion. Húrin’s role in this tale is canon up through his departure from Brethil (that was where Tolkien left off); the way that he left his companions a final time is my headcanon. Asgon and Ragnir are the only names of his companions we know from canon; Asgon’s role as a former outlaw who had known Túrin when he returned to Dor-lómin and started a rebellion is canon, and Ragnir’s pessimism (asking to go home) and his relative youth is also from canon. Everything else about these outlaws is my headcanon, including my reasons for why they weren’t present at the Nírnaeth where literally all the able-bodied men of the House of Hador had perished (except for Húrin). Húrin did go to Nargothrond after Brethil, but I made up everything past that point. We know that there were some Edain at the Havens of Sirion (and presumably there were Men present in the War of Wrath that Elros mingled with before becoming their King), so I thought this could be a way for the remnant of the Haladin (and some of the House of Hador) to get there. I’ll go over the rest of “The Wanderings of Húrin” in future edits, when we get to the relevant Haladin characters.

Gaurwaith ft. Neithan, Beleg Cúthalion, Forweg, Andróg, Andvír, Algund, Ulrad, Orleg, Blodren This is largely a canon-compliant overview of Túrin’s life among the outlaws. The stories of Forweg and Andróg (and Beleg and Túrin/Neithan) are canon (though I did take that extra step and marry off Túrin and Beleg). Orleg’s story is canon, though it’s one that I had overlooked on my various readthroughs of Túrin’s Silm chapter & CoH. Algund and Ulrad’s stories are presented in a slightly tweaked/condensed form; Andvír’s origins as the son of Andróg (??? when did he have a son and why is it never mentioned in the main story???) are canon but (as expressed in parentheses) rather baffling, so I didn’t really emphasize him. Blodren is a character who isn’t in the later drafts of this story; he was an Easterling who was tortured by Morgoth because he “withstood Uldor the Accursed,” and eventually turned into a spy for Morgoth. (As with all Easterling names, his etymology is entirely made up.) He “served Túrin faithfully for two years” before fulfilling the role later taken up by Mîm and betraying the Gaurwaith to the orcs. He was killed by a “chance arrow in the dark” during the battle. I altered his story so that he wasn’t personally tortured by Morgoth and thus did not turn; since he was an Easterling and the rest of the Gaurwaith were Edain, I decided they probably treated him poorly, and threw in a bit of a friendship with Mîm as a nod to how Mîm took over his role. Also, I think Easterlings having pre-existing relationships with dwarves is a cool concept—especially since Bór’s people and Azaghâl’s people both served under Maedhros at the Nírnaeth, and could possibly have had the chance to interact!

~~~

CONTINUED IN APPENDIX C

#three houses of the edain#peoples of arda#house of hador#house of marach#estolad#ered wethrin#dor lomin#my meta#tefain nin#thote appendices

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Further reactions to "The book of lost tales":

I appreciate that Idril canonically wears armor and does swordfighting.

I feel like I can actually imagine adult!Idril much better now like in armor and with open hair, distraught but ready to fight while babby Earendil does not yet realize the danger...

My first thought is that Earendil was probably cute in that baby chainmail. My second thought is OUCH, Idril and Tuor always made sure their growing baby had fitting chainmail cause they felt the apocalypse might get them at any moment. Imagine that, imagine them having the baby armor fitted every year or so :(

Its fun how much of the basic structure already exists but most of what you'd consider the main characters doesn't exist or is scattered across various minor roles The only Prince anywhere in sight is Turgon - Except for Team Doriath, theyre all accounted for. I suppose Maeglin is kinda there in name only with vaguely the same role & motivation, but looks personality and background all did a 180 since. Luthien is still pretty much "princesd classic" at this point, not quite the fearless go-getter from the final version - markedly this version tells Beren that she doesnt want to wander in the wilderness with him whereas the final one says she doesnt care and its Beren still wants to get the shiny so as not to ask this of her and also for his honor.

I mean in the finished version Id consider the 3rd and 4th gen royals to be the main characters (well, alobgside Team Doriath and the varioud human heroes) and theyre hardly here. Imagine the silm with no Finrod!

Feanor had no affiliation with the royal family whatsoever, and is also generally less super. He's just the guy who won the jewelsmithing competition, not the inventor of the whole discipline. Still seems to have been envisionad as a respected member of the community who gets called to the palace for crisis meetings and is listened to when he stsrts giving speeches. From the first he already has the backstory of going off the deep end (or at least growing disillusioned with Valinor) after a family member is killed by Melkor and theyre still the first to die, but its just some other rando unrelated to the royals

The situation regarding the humans is different - instead of Melkor leaking their existence, its Manwe who explains that the other continents were supposed to be for them eventually. So Feanor goes off on a tirade about weak puny mortals comes off as a more of a jerk unlike in the final version where Melkor barely knew about the humans and described them to the Noldor as a threat. On the other hand in this one, also very much unlike in the finished product, Melkor dupes even Manwe into being unfair to the elves as a whole. In this the final version is a definite improvement, both Feanor and the Valar come off as a lot more sympathetic and though still deceived he's partially right in some things at least, so you have more of a genuine tragedy rather than a simple feud

There is something to the idea of Commoner!Feanor tho. I guess some of this survived in his nomadic explorer lifestyle and how both his wife and mother (who arent mentioned here) eventually were the ones to get that background of being not especially pretty ladies who are not from the nobility but got renown, respect and acclaim for their unique talent and contribution to society, with each having invented things and Nerdanel also being renowed for her wisdom. Hes sort of an odysseus-like Figure in that sense. I suppose later developements necesitated that Maedhros & co. have an army not just a band of thieves, which means they needed to be nobles/lords. That said this being a society where artisans are very respected and half the lords have scholarly/artistic pursuits going, the gap was probably not as big to begin with as it might have been in say, medieval England. Esoecially since Nerdanel's father had been given special honor by one of the local deities and that the social order might have been a very recent thing in Miriel's time. One might speculate that the first generation of Lords started out as warriors during the great journey, or perhaps just Finwe's friend group.

Also found that bit intetesting where the Valar have to deal with the remaining political tensions and effects of Melkor's lies on the remaining population in Valinor... - i guess with the change of framing device it was less likely for news of something like this to reach Beleriand. That, or the existence of Finarfin and his repentance made this go smoother this over in later cannon

Turgon's go-down-with-the-ship moment reaaly got to me. Im half tempted to write a fic where his wife, siblings and dad glomp him on arrival in Mandos. I dont care that none of them exists yet in this continuity i want Turgon to get hugs

I love all the additional Detail that got compressed out in the shift from fairytale-ish to pseudohistoric style especially all the various Valinor magic insofofar as it is compatible with the final version - particularly love the idea of the connection between the lamps and the trees that is now integrated into my headcanon forever

Its actually explained what the doors of night are

If I had not already read unfinished tales or volumes X to XII where this is also apparent, this is where I would say: Ah so the Valar were supposed to be flawed characters. Manwe has an actual arc; by the time he sends Gandalf he finally "got" it. I think in the published silm the little arcs of Ulmo and Manwe are mostly just lost in compression/ less apparent when only some of the relevant scenes got in but not all

It occurred to me way too late that the "BG" chars are the most consistent because theyre at the start and most stories are written from beginning to end. Finwe doesnt get a dedicated paragraph of explicit description until HoME X but my takeaway was that he's described pretty much like I always imagined him anyways/ same vibe I always got from him... charismatic, thoughtful, enthusiastic, sanguine temperament, brave in a pinch but at times lets his judgement be clouded by personal sentiment (though that last bit is more apparent/salient as a character flaw once he became the father of a certain Problem Child) ...i guess this would be a result of jrrt having had a consistent idea of him in his head for a long time.

This means Finwe's still alive at the time of the exodus which is just fun to see/interesting to know... Interestingly he sort of gets what later would be Finarfin's part of ineffectually telling everxone to please chill and think it over first while Feanor simply shouts louder (which is consistent with his actions before the sword incident in later canon where he initially spoke out against the suspiciozs regarding the Valar) - but its not exactly the same, he's more active than Finarfin later in that when "chillax" availed nothing he said that then at least they should talk with the other Kings and Manwe to leave with their blessing and get help leaving (This seems like it would have been the clusterfuck preventing million dollar suggestion in the universe where Feanor is related to him and values him) but when even that falls on death ears he decides that he "would not be parted from his people" and went to run the preparations. I find it interesting that the motivation is sentiment/attachment (even phrased as "he would not be parted from [his people]" same words/ expression as is later used for the formenos situation), not explicitly obligation as it later is for Fingolfin (who had promised to follow Feanor and didnt want to leave his subjects at the mercy of Feanor's recklessness )

Speaking of problem children. It seems the sons of Feanor were the Kaworu Nagisa of the Silmarillion in that originally all they do is show up at some point and kill Dior as an episodic villain-of-the-week. And then, it seems their role got bigger in each continuity/rewrite... probably has something to do with the Silmarils ending up in the title later making it in the sense their story that ends and begins with them. They have zero characterization beyond "fierce and wild" at this point, though in what teetsy bits there is we already have the idea that Maedhros is the leader and Curufin is the smart one/shemer/sweet-talker, though not the bit where Maedhros (or Maglor, or anyone really) is "the nice one". Which I guess explains why "Maglor" sounds like such a stereotypical villain name.

"The Ruin of Doriath" was purportedly the patchworkiest bit of the finished product, but I never noticed and it actually left quite an impression of me upon first reading, the visual of Melian sitting there with Thingol's corpse in her arms contemplating everything thinking back to how they met... she had the knowledge to warn him not to doom himself but couldnt get him to understand it because he doesnt see the world as she does.... After reading this though I wish there was a 'dynamic' rendition that combined all the best bits like, youd have to adapt it to the later canon's rendition of the dwarves, have Nargothrond exist etc. But i mean that just makes Finrod another dead/doomed relative of Thingol's whom bling cannot truly replace, like Luthien and Turin. In the Silmarillion you could easily read it as just an "honoured guest treatment" but here and in unfinished tales I get the impression that Thingol actually did see Turin as a son.

Already you see the idea of trying to make the stories all interconnected but there is less than there will be (the human heroes aren't related yet and there is basically no Nargothrond, which is later a common thread for many of the stories - a prototype shows up in the 'Tale of Turambar' tho complete with half baked prototypes of Orodreth and Finduillas

O boi im not even through yet

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Angela P. Nicholas--author of "Aragorn: J.R.R. Tolkien's Undervalued Hero"

We were very excited to have the opportunity to interview author Angela P. Nicholas. Her book "Aragorn: J.R.R. Tolkien's Undervalued Hero" is an extremely detailed, in depth examination of Tolkien's Aragorn--his life, his relationships, his achievements, his skills, and his personality. It is a very worthwhile addition to any Tolkien library. She has some fascinating insights into Aragorn, book vs movie representations of the character, thoughts on the upcoming Amazon series and fan fiction as part of the Tolkien fandom. Hope you enjoy reading it!

1. How did you first become interested in Tolkien?

Answer:

Although The Lord of the Rings was very much in fashion during my student days in the late sixties and early seventies I wasn't interested in it at that stage – probably because I didn't tend to follow fashions! It was not until a few years later, in 1973, that a friend persuaded me to read it. He stressed that it would be a good idea to read The Hobbit first and promised me that I was "in for a treat". I was hooked immediately and when I got together with my future husband soon afterwards I wasted no time in introducing him to Tolkien's works as well! I re-read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings several times during the seventies and bought The Silmarillion as soon as it was published in 1977. Further readings have followed since, especially while working on Aragorn, extending to Unfinished Tales, the twelve volumes of The History of Middle-earth and Tolkien's Letters as well.*

2. Aside from reading the books, have you had any other immersion in the Tolkien fandom? Online, through societies, other venues?

Answer:

My Tolkien-related activities include membership of the Tolkien Society since 2005, leading to attendance at Oxonmoot (most years) plus a number of AGMs, the occasional seminar and the event in Loughborough in 2012. I've contributed several articles to Amon Hen and also gave a talk about Aragorn at Oxonmoot a few years ago. In addition I attend meetings of my local smial (Southfarthing) which is actually a Tolkien Reading Group.

3. There are so many richly written, deeply compelling characters in Tolkien. How did you decide to focus on Aragorn?

Answer:

There wasn't really any decision to make, as right from the start I found Aragorn the most complex and appealing character in the book. Every time I re-read The Lord of the Rings - including delving into the Appendices - I found new depths to his character and significance.

4. What prompted you to write this book? How did the impetus to write about him, in such rich detail, come about?

Answer:

The actual impetus came from Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings films. Although I enjoyed his portrayal of Aragorn in some ways, it was clear that there were significant differences between the film and book versions of the character. For my own satisfaction I decided to re-discover Tolkien's Aragorn by studying all the Middle-earth writings and making detailed notes on anything of interest. I did not, at that stage, see myself actually writing a book.

5. Did you initially plan such an exhaustive and detailed study of this character, when you first decided to write the book?

Answer:

No, I didn't envisage anything so detailed. It just got out of hand: the more notes I made the more ideas I had and the thing just grew exponentially!

6. The title makes use of the word ‘undervalued’—how do you define that in terms of Aragorn and how did you come to associate that word with him?

Answer:

While studying Aragorn it became clear to me that his role in the story is a lot more significant than is immediately apparent. This is partly because the book is “hobbito-centric”, to use Tolkien's own word [see end of Letter 181 in The Letters of J R R Tolkien edited by Humphrey Carpenter], so is largely written from the hobbit viewpoint. For this reason Aragorn's ancestry and earlier life are only described in the Appendices, which not everyone reads. Thus his deeds - and their significance - are often overlooked, causing him and his role to be undervalued. Chapter 1.5 of my book in particular aims to address this problem by concentrating on the story of The Lord of the Rings from Aragorn's point of view. He does many crucial things behind the scenes, for example: the lengthy search for Gollum; standing in for Gandalf as shown by the secret vigil he conducts over Frodo during the months before the latter's departure from the Shire; and - the most significant achievement - confronting Sauron in the Palantír of Orthanc thus implying that he himself has the Ring and so diverting Sauron's attention away from Frodo.

7. If you were to consider writing a similar book about another character from Tolkien’s legendarium who would you choose to focus on?

Answer:

I find Finrod Felagund, Galadriel and Elrond interesting, especially in the light of their impact on Aragorn and his ancestry. Among the hobbits, Merry Brandybuck is rather appealing. However I have to say that I am not planning to do another book on this scale!

8. What were your thoughts on the portrayal of Aragorn in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies?

Answer:

Given “book” Aragorn's lengthy struggle to regain the kingships of Arnor and Gondor and to be deemed worthy of marrying his beloved Arwen, it was extremely disappointing to be presented with the image of “Aragorn the reluctant king” who breaks off his engagement so Arwen can sail west.

In general I felt there was too much emphasis on Aragorn as a fighter, along with almost total neglect of his formidable healing skills, impressive foresight and knowledge of history and lore.

Another great disappointment was the omission of the challenge to Sauron in the Orthanc Stone. Yes, this incident was included in the extended version of The Return of the King, but it appeared in the wrong place and also gave the impression that Aragorn lost the confrontation. (The credit for seeing the enemy's plans in the Stone was actually given to Pippin!)

In addition I found the beheading of the Mouth of Sauron particularly disturbing.

9. Did you find Viggo Mortensen believable and appealing as Aragorn?

Answer:

In spite of my answer to the previous question I liked Viggo Mortensen's performance. He did actually look something like my image of Aragorn and he seemed to capture the sadness, remoteness, physical courage and protectiveness I associate with the character. Basically I thought that Mortensen did very well with the part he was given to play - but the part was not that of Tolkien's Aragorn!

10. Amazon has bought the rights to the appendices of the Lord of the Rings and is planning a 5 part series. Rumor has it that the first season will focus on young Aragorn. What do you hope to see in this adaptation and are there any particular incidents/scenes/events that you think merit particular attention or inclusion?

Answer: The following seem to me to be important:

- Putting Aragorn's early life in the context of “Estel”, the Hope of the Dúnedain, who has been prophesied to be the one who will atone for Isildur's failure to destroy the Ring, and who will restore the kingship of Men.

- Some emphasis on his family members: Ivorwen, Dírhael, Gilraen, the death of Arathorn, subsequent fostering by Elrond, and training by Elladan and Elrohir. Some indication of the close relationship with his foster-father would be good: Elrond loved Aragorn as much as his own children but this was not made apparent in the Peter Jackson films.

- The scene when Elrond tells the 20-year-old Aragorn his true identity.

- First meeting with Arwen

- Friendship with Gandalf from age 25 onward

- Betrothal to Arwen, and Galadriel's involvement: he was 49 by this time, so that may not be considered part of his early life (though 49 would be young for one of the Dúnedain!)

- Perhaps some reference to the events of The Hobbit in 2941-2 when we know that 10/11-year-old Aragorn was living in Rivendell.

11. What do you find most inspiring about Tolkien’s world?

Answer:

The depiction of such a complete and seemingly realistic world, and the fact that one can pick up extra hidden depths in both story and characters on each re-reading. There is always something else to discover or a new interpretation of a familiar passage.

12. Are you involved in any more projects involving Tolkien?

Answer:

Not at the moment. I have one or two ideas for possible short articles.

13. What advice would you give to those first encountering Tolkien’s work and wanting to learn more about Middle-earth and its inhabitants?

Answer:

Speaking from my own experience I would say: Read The Hobbit first then The Lord of the Rings several times, including the Appendices, before delving into other works: The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, The History of Middle-earth and Tolkien's Letters, plus critical works, etc. - and of course online sources which were not available when I first became interested in Tolkien.

14. In the preface to your book you mention discovering the online Tolkien fanfiction community—what are your thoughts on Tolkien fanfiction? What time frame was this and did you join the fanfiction community at that time?

Answer:

I started writing fanfiction during 2003 and continued doing it until about 2007 which was when I made the decision to write a serious work about Aragorn. One piece of fanfiction appeared in Amon Hen, and the rest on a couple of websites which I think no longer exist.

My main thought about fanfiction is that it was this which started me off writing. It was very much an experiment as my last attempts at creative writing dated back to my school English lessons in the 1960s! Without trying the fanfiction first I don't think I would ever have got round to writing articles for Amon Hen, let alone my book.

15. Did encountering fanfiction or even writing it have an effect on your thoughts on Aragorn and the salient points of his character that truly defined him?

Answer:

Yes - because the chief aim of the fanfiction (mine and, I suspect, that of other fanfiction writers) was to fill in the gaps in Aragorn's story. I scoured the text for possible motives and feelings of the people I was writing about. My fanfiction was always based on the “book” version of the story and characters (never on the film version). I did sometimes use invented characters but only to add detail and interest to the story. For exampIe this approach was used when writing about Aragorn's Rangers and when describing his interactions with the inhabitants of Bree. Some stories were actually based on invented characters, in order to try and see Aragorn through the eyes of others. This probably helped me when writing the “Relationship” chapters [see next question.]

16. One aspect of your book that to me is truly unique is Part 2, where you study and interpret his interactions and relationships with the other races and individuals he encounters in Middle-earth. What made you decide to pursue this format?

Answer:

It just seemed the most logical approach. I couldn't study Aragorn's relationships properly without also studying the other half of each different relationship. There was so much to be revealed about both parties in these studies, many of which were based around families and generations (such as in Rohan, and Gondor, and in the Rivendell and Lothlórien communities).

17. Aragorn as a character brings together elements and bloodlines from the First Age into the Fourth Age—you outline these genealogies and relationships quite thoroughly in your book. How do you think this knowledge of his genealogy affected him in his transition from youth to Ranger to King? Is there a character from the earlier Ages that you think had a more significant impact on him or that he resembles the most in character?

Answer: Aragorn would presumably have learnt about these people as a child during his history lessons, but would not have connected them specifically with himself until he was made aware of his true identity at the age of 20.

Elendil, Isildur and Anárion stand out as the obvious significant ancestors whom Aragorn would have striven to emulate - plus, in the case of Isildur, also to atone for his failure to destroy the Ring.

Other ancestors who may well have inspired admiration and/or gratitude in Aragorn include:

- Elendur the self-sacrificing eldest son of Isildur. A passage in Unfinished Tales refers to Elrond seeing a huge similarity between Elendur and Aragorn, both physically and in character. [See footnote 26 at the end of The Disaster of the Gladden Fields.]

- Amandil, the father of Elendil, who advised his son to gather his family and possessions in secret and plan an escape from Númenor in the event of a disaster, before himself courageously setting out for the Undying Lands to plead for mercy for the Númenóreans. He was never heard of again, but the Númenórean race was saved due to Elendil's successful escape to Middle-earth after following his father's instructions.

- Tar-Elendil the 4th King of Númenor and his daughter Silmarien. The royal line of Númenor and its heirlooms only survived via this female line.

- Tar-Palantir the penultimate King of Númenor who resisted the influence of Sauron and tried to turn the Númenóreans back to friendship with the Eldar.

Another notable ancestor for a different reason was Arvedui, the last King of the North Kingdom, who tried to claim the throne of Gondor as well but was rejected and ended up losing both kingdoms before fleeing to the frozen north where he died in a shipwreck. Aragorn must have regarded his own mission to reunite the two kingdoms just over 1,000 years later with some apprehension.

Ar-Pharazôn would clearly have served as a dire warning!

I wonder if Aragorn felt any unease about his namesake, Aragorn I, being killed by wolves!

A comment in Appendix AI(i) of The Lord of the Rings states that the Númenóreans came to resent the choice of Elros to be mortal, thus triggering their yearning for immortality and their subsequent downfall. Did Aragorn ever resent his ancestor's choice? Personally I think he would have had the knowledge and wisdom to understand Ilúvatar's purpose in reuniting the immortal line of Elrond with the mortal line of Elros (through the marriage of Arwen and Aragorn) in order to strengthen the royal line prior to the departure of the Elves and the beginning of the Age of Men.

18. What are your thoughts on the original premise that Aragorn was Trotter, a hobbit?

Answer:

Eeek! The grinning and the wooden shoes! I don't think that the book could possibly have had the same impact, depth and sense of history if the main characters had all been hobbits. I seem to remember that the name “Trotter” still survived for a while after he became a man. “Strider” sounds much better. I'm so glad Tolkien didn't pursue the original idea.

19. Do you have any advice for budding Tolkien acolytes and scholars who are first delving into the legendarium?

Answer:

Read and re-read, record thoughts, ideas, passages worth quoting. Read what JRRT wrote and what others have written. This worked for me, over a very long period - more by accident than design.

*this answer is the same as Angela's answer in the Luna Press interview with her as it has not changed! Take a look at that article for more information on Angela and her book. https://www.lunapresspublishing.com/single-post/2017/09/04/Aragorn---A-Companion-Book

Interviewed by @maedhrosrussandol

July 14th 2018

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just started following you and your post about welcoming all fans of Tolkien really made me happy bc I just joined in the fandom after an artist I like drew some Angbang. That was the beginning of the end lol. I have been reading wiki articles but I know that is not near enough and is it exhausting for me but from what I know there are loads of books too and I don't know where to start. Where should someone start? Is there a reading order? Any help would be appreciated. Thank you.

Angbang has yet again pulled the unsuspecting victim straight into the void. I don’t think Tolkien would have imagined that the love of his two main villains would bring in readers, but anyway, however you got here: welcome! We don’t have cookies, but we do have feels and literal decades of writing to sift through. Your stay will be as long as you choose, and that may be a long, long while. I have been in the fandom for nearly 20 years and I still have not read everything or explored everything yet.

One thing I would like to impart on you though is this; reading Tolkien is hard. Yes some people will counter this with a sniff and a scoff and insist that it is not, but most will find his work daunting and overwhelming. If not in how it is written then in the sheer volume of information and variations of his legendarium. What helped me profoundly was reading it not as a fun casual fantasy but as a historical subject. When you put your mind in a state of what to expect out of it really helps your understanding of the text I feel.

As for reading order I personally think you should tackle it as so;

The Hobbit (keep in mind this is written before much of his own lore was settled and is meant to be a children’s book).

The Lord of the Rings (one tale, three volumes with the Appendices which are a great resource and gear you up for some HISTORY).

The Silmarillion.

Reading these five books first I feel is a great basic start and they are more or less consistent and are most “in sync” with each other. Don’t shy away from taking notes, however, particularly with The Silmarillion because from that point on it is delving into his legendarium, and the difficulty increases with each one.

The next round of books you might want to read are as follows;

Unfinished Tales

Children of Hurin

Letters (you can choose to read these here or after everything else, I know many people who saved the letters for last thought that it would have made better sense to read them during their first readings at some point.)

The rest of your journey should be the collective Histories of Middle Earth, all twelve volumes, and these are not for the faint of heart. Be prepared to take notes, be prepared to have a lot of contradiction and don’t come into them thinking that everything you will then read is gospel. If you are anything like me you will create a mosaic of what you like and sort of mush them together to make your own appealing version of events.

I. The Book of Lost Tales, part 1

II. The Book of Lost Tales, part 2

III. The Lays of Beleriand

IV. The Shaping of Middle-earth

V. The Lost Road and Other Writings

These first five go over a lot of the events of The Silmarillion (the first and second ages) and contain some of the earliest writings of Tolkien.

VI. The Return of the Shadow

VII. The Treason of Isengard

VIII. The War of the Ring

IX. Sauron Defeated

These four, as you may be able to tell from the titles, focus mostly on the events of The Lord of the Rings and the later second age through the third age.

X. Morgoth’s Ring

XI. The War of the Jewels

We’re back to The Silmarillion. These two books are cited a lot in Tolkien analysis partly due to the interesting information he provided in them (LACE is in volume X) and they are comparatively newer writings, so some fans like to consider these as more close to what the professor was going for in his legendarium.

XII. The Peoples of Middle-earth

The final volume is a lot of miscellaneous writings that spans all ages, it’s like the kitchen junk drawer for the professor’s writing.

Of course we also have new books as well to add to the list that are profoundly useful such as;

Beren and Luthien (2017)

This is a nifty book that focuses entirely on Luthien’s epic adventure and the drafts Tolkien wrote of it. It is a great resource.

The Fall of Gondolin (set to be published this year 2018)

Will also be like Beren and Luthien in that it centralizes on writings concerning this one event making it easier to study. Whew. Thank you Christopher Tolkien!

There also are a plethora of writings other people have done to supplement Tolkien’s writings intended to be good resources. Some are. Some are questionable. And others I just don’t even understand how they even got published.

My personal favorite supplementary resources are;

The Atlas of Middle-earth (revised edition) by; Karen Wynn Fonstad

This is a guide to the geography of Arda through the ages and so much more. A great resource to the change in landscape and military movements and general data about the landscape and the people who live there.

The Languages of Tolkien’s Middle-earth by; Ruth S. Noel

Short and sweet but it provides a quick and easy way to look at a glance the rules of each language. Dictionary is really pathetic but you can find better ones online, this book however has the language guides such as sentence structure and pronunciation. I like it because it is in one small book so looking things up is convenient.

Flora of Middle-earth. Plants of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Legendarium by; Walter S. Judd & Graham A. Judd

Tolkien was a great admirer of plants and these two compiled an entire book of each and every plant species mentioned in his writings, fictional and non. An interesting perspective. Has a fantastic section on the two trees of Valinor that for that part alone is worth buying. A love song for Yavanna.

The Science of Middle Earth (revised 2nd edition) by; Henry Gee

This book. This is my absolute favorite book anyone has written about Tolkien, period. This author goes into the possible science for HOW Tolkien’s world could function; as it is clear that Middle-earth is not a playground for magic but something much more fascinating. A great perspective.

This of course is my personal opinion for how to tackle reading, if you wanted an order. I did NOT read the books in order at all, and I admit I have not read some of these myself to completion.

If you are going to read anything I would definitely read the first five then from there on if it is just too daunting/overwhelming I would supplement yourself with select books focusing on what interests you the most. Also, engage in conversations with other fans, that alone helped me most of all when it came to understanding the writings. If you are lucky your university or college might even have a course on it. If anyone else has an input it would be appreciated, as always.

Welcome to the fandom, happy reading.

150 notes

·

View notes

Link

[I posted this essay to my blog The Heretic Loremaster over the weekend. Click the link above if you’d rather read it there. Reactions are welcome in both places.]

Who wrote The Silmarillion? It's a question with a more complicated answer than it seems on the surface. Yes, of course, J.R.R. Tolkien wrote the book that I picked up from a Barnes & Noble fourteen years ago, that is now on my desk with its cover coming off and its corners rounded from being read so many times. But who, in the vast imagined world within its pages, is telling the story? The narrator of The Silmarillion is so distant as to be barely discernible at all; it is possible to believe he doesn't exist at all. Indeed, in at least my first two readings, I did not think much of him. I assumed a distant, omniscient presence recounting what happened in plain, incontestable terms. Just the facts, ma'am.

The fact is, though, that J.R.R. Tolkien--the Silmarillion author whose name is on the cover--always imagined and constructed his stories not just as stories but as historiography: documents written by someone within the universe in which the history occurs. This complicates things: gone is the distance, the omniscience, and perhaps most importantly, the impression that the stories happened exactly as they are told.

This wouldn't be a problem--in fact, would be quite simple, as most fiction has point of view that is biased or unreliable--but for the fact that this isn't simple: This is Tolkien. So naturally, he had this idea that he wanted to write his stories as historiography, with a loremaster or chronicler who was himself a part of that history, but he couldn't make up his mind who this person was. In fact, he changed his mind several times, reversals that are documented in The History of Middle-earth for fans and scholars to angst and argue over.

I'm going to make the case that the "Quenta Silmarillion" is part of the Elvish tradition. This is contrary to the belief of Christopher Tolkien and other Tolkien scholars, who assign it to the "Mannish"--namely Númenórean--tradition. (@ingwiel has an excellent discussion of the evidence for this approach.) I understand why they did this, but I think that if you look deeply at the texts and the evidence those texts provide, there is not much to support that the tradition originated with the Númenóreans. (I am willing to concede that Elvish texts may have passed through Númenórean hands on their way back to Elrond and, eventually, Bilbo, but I persist in believing they are nonetheless predominantly Elvish texts representing an Elvish point of view.)

The Idea of the "Mannish" Tradition

The Elvish loremaster Pengolodh was first introduced as the primary author of the "Quenta Silmarillion" prior to 1930, when he was assigned author of the Annals of Beleriand (HoMe IV). Pengolodh was a tenacious character: Texts written as late as 1960 were still being assigned to him. So what happened?

The idea of the "Mannish" loremaster was a late idea and introduced as part of the series of writings collected by Christopher Tolkien under the title Myths Transformed (HoMe X). In a text that Christopher dates to 1958, Tolkien writes:

It is now clear to me that in any case the Mythology must actually be a 'Mannish' affair. ... The High Eldar living and being tutored by the demiurgic beings must have known, or at least their writers and loremasters must have known, the 'truth' (according to their measure of understanding). What we have in the Silmarillion etc. are traditions (especially personalized, and centred upon actors, such as Fëanor) handed on by Men in Númenor and later in Middle-earth (Arnor and Gondor); but already far back--from the first association of the Dúnedain and Elf-friends with the Eldar in Beleriand--blended and confused with their own Mannish myths and cosmic ideas. (Myths Transformed, "Text I," emphasis in the original)

To summarize: in 1958, Tolkien began to deeply question whether a civilization as advanced as that of the Eldar--a civilization that also had access to the teachings of the Ainur, who knew firsthand the structure of the universe--would produce myths that included such components as a flat Earth and the "astronomically absurd business of the making of the Sun and Moon" ("Text I"). This led to some radical cosmological rearrangements in Myths Transformed--and the relatively overlooked decision to reimagine the Silmarillion histories from a Mortal rather than an Elvish perspective. In an undated text also presented in Myths Transformed, Tolkien again takes up this question and explains the method of textual transmission in greater detail:

It has to be remembered that the 'mythology' is represented as being two stages removed from a true record: it is based first upon Elvish records and lore about the Valar and their own dealings with them; and these have reached us (fragmentarily) only through relics of Númenórean (human) traditions, derived from the Eldar, in the earlier parts, though for later times supplemented by anthropocentric histories and tales. These, it is true, came down through the 'Faithful' and their descendants in Middle-earth, but could not altogether escape the darkening of the picture due to the hostility of the rebellious Númenóreans to the Valar. ("Text VII")

"A leading consideration in the preparation of the text was the achievement of coherence and consistency," Christopher Tolkien wrote in a note on The Valaquenta in The Later Quenta Silmarillion II (HoMe X), "and a fundamental problem was uncertainty as to the mode by which in my father's later thought the 'Lore of the Eldar' had been transmitted."

Christopher Tolkien tentatively dates The Later Quenta Silmarillion II (LQ2) to 1958. Along with the last set of annals, The Annals of Aman and The Grey Annals, this represents the final version of the Silmarillion that his father produced. (See "Note on Dating" at the end of LQ2 in HoMe X.) Interesting about these texts--especially LQ2--is the fact that Tolkien removes all attributions Pengolodh. Mentions of Pengolodh are sprinkled throughout the Later Quenta Silmarillion I, which was written around 1951-52. When Tolkien "remoulded" LQ1 into LQ2, he removed Pengolodh. Also written around 1958? That first Myths Transformed text in which Tolkien asserts that his cosmology requires a Mortal and specifically bars an Eldarin loremaster.

And the Evidence of the Elvish, Part 1: The Creative Process

All this probably seems very simple. Tolkien was clear on his intentions. The Elvish tradition doesn't work, in his opinion. Therefore, it must be Mortal. He even took out the Elvish loremaster from the oldest Silmarillion draft. Simple, right?

Never. Working with any of the Silmarillion material--including the published Silmarillion--is necessarily speculative. This is a posthumous text, unfinished and existing in many forms. I think Christopher Tolkien did an admirable job of making a published book out of the tangle of his father's writings, but making that book required making decisions, as alluded to above, about how to decide what to include.

On this particular question, there are two approaches to making a decision on mode of transmission: There is Tolkien's stated intention, and there are the texts themselves and what they show of the realization of that intention. Christopher Tolkien, and many scholars, clearly prefer the first approach. Tolkien was clear on what he wanted, so that's the way to read the texts.

I prefer the second.

Perhaps this is because I approach the welter of Silmarillion texts as a creative writer as well as a Tolkien scholar. My experiences as an author of fiction myself lead me to question whether the creative process lends itself to the kind of neat analysis that says, "The author stated his intention. Here we have our answer." My experience tells me it is rarely that simple.

Below is what I imagine the creative process looks like for worldbuilding and constructing stories in that world, done in clipart and scribbles. For me, most of my work goes on in my mind: while driving to work, falling asleep at night, reading other authors' work, washing dishes, daydreaming. Some of the thinking is intentional, other occurs because it's where my mind wanders where I'm bored. Sometimes, thinking is sparked by an outside stimulus: an interview on the radio, a song, an image, a clip from a movie or TV. All of it goes into this tangle of thought constantly swirling in my mind, making and remaking my imagined world. Every now and then, an idea leaves my mind and takes concrete form as I write it down.

But only in limited instances do these ideas become finalized, incontrovertible--"canon," if you will. Sometimes an idea won't work and withers, unfinished. Other times, an idea is written down, only to dive back into the welter of thought in my mind for further reworking and reshaping--sometimes radically so.

Every author's creative process is different, of course, but hold up The Tale of the Sun and the Moon from the Book of Lost Tales next to the story Tolkien writes in Myths Transformed and the two are radically different, showing what any Silmarillion fan can tell you: Just because Tolkien wrote it down doesn't mean he meant it. Likewise, he went years at times without working on the legendarium, yet his letters and the progress we observe in the drafts show that he was always thinking about it. In short, his creative process, in this regard, seems a lot like mine.

Around 1958, we can say with some certainty that an idea crystallized from Tolkien's thoughts about his legendarium that the mode of transmission had to be centered on Mortals, not Elves. The idea seems to have loomed large in his awareness--along with ancillary ideas about cosmology--to the extent that it appears to reflect in decisions he made in revising LQ2.

But does that mean it is definitive? That it is "canon"? Not necessarily. In fact, I'd argue that we have proof that this particular manifestation of an idea was one that was far from finalized but dove back into the swirl of thinking on worldbuilding to be reconsidered and reworked--and ultimately unrealized.

And the Evidence of the Elvish, Part 2: Point of View

Point of view is no small thing in a story. In fact, in all but a few cases, it is so essential that to change the point of view risks breaking the story in a way that changing other elements rarely does. It's like painting. If you paint from the point of view of a peasant looking at a castle from the field where she labors, you cannot suddenly decide that the point of view is that of the princess looking out from the room in the castle where she spends most of her days, at least without redoing the painting entirely.

Likewise, one cannot take a story written from one point of view, then suddenly decide to change to a different point of view with any guarantee that the story will still work, much less make sense, without rewriting the story. In fact, in many cases, it will not.

Changing from an Elvish to a Númenórean point of view is not so simple as declaring, "Let it be!" and there it is. In the case of the "Quenta Silmarillion," the Eldarin (specifically Gondolindrim) perspective is deeply embedded. @grundyscribbling‘s post here is a good run-down of how the narrator's affiliation with Gondolin is revealed, even if never stated, in the stories included as part of the "Quenta." My article Attainable Vistas looks at some of the numerical data I've compiled that suggests a Gondolindrim perspective. At last year's Tolkien at UVM Conference, I presented more of that data, as well as new evidence that even the narrator's language in the "Quenta," reveals the point of view of a loremaster from Gondolin. Tolkien didn't put Pengolodh's biography down on paper until the 1959-60 text Quendi and Eldar, but the texts suggest that Pengolodh's identity was swirling in his mind many decades before that, and he wrote the "Quenta" with that point of view always in mind. Changing the point of view of such a story requires significant rewriting of the text. Do we have evidence that any of that rewriting--short of striking Pengolodh's name from LQ2--occurred?

No, we do not.

In fact, we sometimes see the opposite.

And the Evidence of the Elvish, Part 3: The Texts

The Later Quenta Silmarillion II becomes a relevant text to examine here because 1) it was written at the time when we know Tolkien was thinking about the mode of transmission and 2) his striking of Pengolodh's name from this version suggests he was beginning to act on his stated intention to revise the "Quenta" to reflect a Númenórean point of view. It is also an interesting text to study because it is a revision of LQ1, written about seven years earlier when the mode of transmission was, as far as I can tell, unreservedly Elvish.

Does the LQ2 contain other revisions toward a Númenórean mode? No, it is does not. In fact, it includes additions that, from a Mortal perspective, are suspect.

Laws and Customs among the Eldar. One of two major additions to LQ2 was Laws and Customs among the Eldar (L&C). L&C is explicitly attributed to Ælfwine, the Mortal man who was part of the mode of the transmission involving Pengolodh. Ælfwine is Anglo-Saxon, not Númenórean, but L&C is clearly written from the point of view of a Mortal commenting on Elves.

L&C opens with the sentence, "The Eldar grew in bodily form slower than Men, but in mind more swiftly." This comparison immediately establishes a Mortal point of view different from that of the "Quenta" as a whole, where Mortals are usually but supporting actors in a drama enacted by Elves. The first two paragraphs continue this comparison and assume the distinct point of view of a Mortal. Later, in the section "Of Naming," the narrator notes that the variety of names used by a single Elf "in the reading of their histories may to us seem bewildering," again establishing a Mortal point of view (emphasis mine).

L&C is an example of what a text written from a Mortal point of view would look like. "Men are really only interested in Men and in Men's ideas and visions," Tolkien wrote in Myths Transformed, and L&C acknowledges this by bringing Elvish customs into the context of Mortal experience ("Text I"). This text shows that Tolkien did manipulate the point of view based on his narrator. (This won't be shocking to any writer of fiction, and as an Anglo-Saxonist, Tolkien would have been aware of the impact of point of view on a historical text from that perspective as well.)

Christopher Tolkien dates L&C to the late 1950s (LQ2, "Note on Dating"). The argument could be made that Tolkien hadn't yet begun the process of revising to incorporate a Númenórean narrator. However, of all of the texts in LQ2, L&C is the easiest to revise to change the point of view. It is already from a Mortal point of view! Simply change the attribution to Ælfwine to a suitably Númenórean name and you have a major chapter of LQ2 aligned with the Númenórean mode of transmission. It is a surface change on the order of removing attributions to Pengolodh, and the fact that Tolkien didn't undertake it makes me question how seriously he truly undertook to revise the point of view.

The Statute of Finwë and Míriel. The Statute of Finwë and Míriel is the second major addition to LQ2. It is likewise dated to the late 1950s (LQ2, "Note on Dating"). If Tolkien wanted to write a text representing a Númenórean point of view, he couldn't have done a worse job of it with the Statute of Finwë and Míriel. Here we have a text deeply concerned with eschatology: Elven eschatology.

The Númenóreans were also concerned with eschatology. You could even say the Númenóreans were obsessed with eschatology, and immortality in particular. Here's a people, after all, annihilated because of their king's obsession with an Oasis song proclaiming, "You and I are gonna live forever!" A Númenórean text that represents Elven eschatology with no commentary grounding it in a Mortal perspective (like Tolkien does with L&C) is almost impossible to fathom. A text that centers on immortality and the decision to forgo immortality would certainly excite commentary from a Númenórean loremaster. Revisions to represent a Númenórean point of view would have to address this chapter--but they don't. Again, this suggests that JRRT's ideas about the mode of transmission weren't as definitive as his writings in Myths Transformed suggest.

And all the rest ...? Outside of L&C, the remainder of LQ2 includes nothing that suggests a Mortal point of view, even though L&C shows that Tolkien was capable, with the addition of a few words, of beginning to establish this. A convincing Númenórean text would have needed deep revisions, but surface changes--like the deletion of Pengolodh--set the course in the right direction.

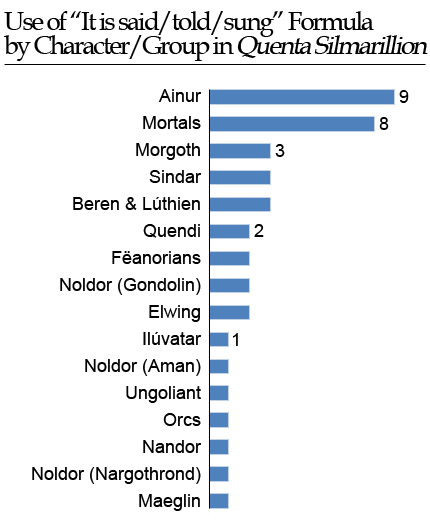

Throughout the "Quenta," Tolkien often uses formulas like "it is said," "it is told," and "it is sung" to indicate that the narrator is receiving information secondhand versus as an eyewitness account. As I discussed at the Tolkien at UVM Conference in 2017, these formulas are used primarily with the Ainur and Mortals. The image below shows the data from one of my slides from this presentation. Adding these formulas is a rather easy way to signal that the information the narrator is reporting is at a distance from him--and LQ2 uses them when reporting on the actions of Ainur to which even an Eldarin narrator could not have borne witness--yet Tolkien did not make these revisions. Instead, this part of the Silmarillion (originally attributed to Rúmil, who would have been present for this history) is written in the style of an eyewitness account, even though a Númenórean loremaster would certainly find these chapters of history the most distant and unattainable. Yet nothing in the style in which these chapters are written suggest this.

There is one passage in particular in the chapter "Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor" that, like the Statute of Finwë and Míriel, seems a ripe opportunity to make revisions to signal a Mortal narrator if Tolkien desired to do so:

In those days, moreover, though the Valar knew indeed of the coming of Men that were to be, the Elves as yet knew naught of it ... but now a whisper went among the Elves that Manwë held them captive so that Men might come and supplant them in the dominions of Middle-earth. For the Valar saw that this weaker and short-lived race would be easily swayed by them. Alas! little have the Valar ever prevailed to sway the wills of Men; but many of the Noldor believed, or half-believed, these evil words. (emphasis mine)

It is hard to imagine a Mortal loremaster self-identifying as "weaker and short-lived" or offering up such an assessment without commentary. Yet this passage was brought over from LQ1--when the narrator was Elvish--without revision.

Another small passage again betrays the Elvish perspective: "But now the deeds of Fëanor could not be passed over, and the Valar were wroth; and dismayed also, perceiving that more was at work than the wilfulness of youth" ("Of the Silmarils," emphasis mine). According to the timelines in the Annals of Aman, Fëanor was about three hundred years old at this point. For a Mortal narrator--even a long-lived Númenórean one--to describe him as a "youth" is difficult to fathom.

Now one might claim that perhaps Tolkien just didn't get the chance to add material. It is one thing to remove Pengolodh but quite another to add content, even in a very brief form. However, he does add other content from Myths Transformed to LQ2: In the chapter "Of the Darkening of Valinor," he adds a reference to the "dome of Varda" that alludes to his revised cosmology. He also adds volumes of other details to flesh out the narrative of LQ1. Yet he leaves the question of transmission untouched. Ironically, Christopher Tolkien refused to consider the revised Myths Transformed cosmology in making the published Silmarllion but stripped Pengolodh from the story on the strength of the purported revision to a Mortal tradition found also in Myths Transformed.

I find the opposite. Tolkien may have stated a desire to change the mode of transmission, but he didn't actually do much to effect this, even when he had the chance to make surface changes to the text that would have set him on the path to deeper revisions. Therefore, I conclude that the "Quenta Silmarillion" should be read as a text written by an Eldarin loremaster and from an Eldarin point of view, with all that entails.

#silmarillion#tolkien#historiography in middle-earth#pengolodh#narrator of the silmarillion#history of middle-earth#myths transformed#statute of finwe and miriel#laws and customs among the eldar#quenta silmarillion#later quenta silmarillion

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey I’ll continue posting my lotr liveblogs soon but I ALSO just started reading children of hurin and I’m dying

So I open this book and the first thing I see. “It is undeniable that there are a very great many readers of The Lord of the Rings for whom the legends of the Elder Days (as previously published in varying forms in The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and The History of Middle-earth) are altogether unknown,” oh, oh honey, ahahahahahaha.

Hey stop mentioning other things I need to read (eg bolt). Stop, stop, I ALREADY HAVE A PROBLEM-

THERES A BIGGER FALL OF GONDOLIN,?

And yet I STILL cannot care one bit about beren and luthien. Sorry.

Ah yes, a forward AND an introduction. Classic

Time UNIMAGINABLY REMOTE... ohhh boy do I have bad news for u........ pls.... I’m the girl who’s used to thinking about 4.5billion years of /irl/ earth.... the first age is nothing...

Oh right Thingol’s gonna be in this book hhhhhhh ugh

WOO onto the book proper!

Ok gloredhel sounds SO SINDARIN... omg does house of hador speak sindarin.... ;-; FEELINGS.

Wait. WIAT. Waaaaaaait. TURIN AND TUOR ARE COUSINS. I. Um. How did I not knOW-

Also hurin short

Morgen was sOMEWHAT STERN OF MOOD AND PROUD. Mhmm. JUST SOMEWHAT.